Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), provide an unbiased approach for the discovery of potential mechanisms and pathways that underlie human characteristics, diseases and drug response. As common diseases are frequently associated with genetic variants that exert small effect sizes, GWAS have increasingly focused on large cohorts of patients. For example, a recent mega-GWAS of schizophrenia included more than 37,000 individuals with schizophrenia and 113,000 controls, which enabled the identification of 108 genetic regions linked to schizophrenia, of which 83 were novel, as discussed in a recent news article (Massive schizophrenia genomic study offers new drug directions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., 13, 641–642 (2014))1. This study was made possible through the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, a large group of more than 500 scientists coming from 80 different institutions.

In the past decade, GWAS have led to a wealth of new information on the physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms that mediate many human attributes such as height and weight, as well as an increased understanding of many common diseases. However, less than 10% of published GWAS have focused on the genetic contribution to variation in therapeutic drug responses and adverse drug reactions (ADRs), i.e., pharmacogenomics (PGx) GWAS. The dearth of PGx GWAS has slowed our understanding of pharmacological mechanisms, spcifically the mechanisms responsible for drug disposition, action and toxicity.

In this short article, we discuss published PGx GWAS data and highlight major areas in which PGx GWAS are needed to advance the fields of pharmacology, toxicology and clinical drug response. We conclude with a short description of recent efforts in PGx GWAS and suggestions for future directions.

PGx GWAS of drug response and toxicity

PGx GWAS have resulted in the identification of several actionable genetic variants that have been genotyped and used to inform drug selection and dosage. The most notable examples include genetic variants in CYP2C19, which guide the choice of antiplatelet drug and dosage2 as well as variants in interleukin 28B (IL28B, also known as IFNL3), which provide information as to whether additional drugs should be included in therapeutic regimens of pegylated interferon-α for hepatitis C infections3. Furthermore, examples of actionable genetic variants associated with toxicity are encoded in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci. In cases such as this, information about specific HLA variants (for example, HLA-B*5701 and HLA-B*1502) is used by clinicians to reduce the incidence of hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir4, carbamazepine5, and allopurinol6. In fact, in the approved abacavir product label, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends that genetic testing for HLA-B*5701 should be performed before abacavir is prescribed. However, despite their potential therapeutic impact, there have been very few PGx GWAS that focused on drug toxicities. Indeed, the US National Human Genome Research Institute and European Bioinformatics Institute GWAS catalog lists only 69 such studies.

ADRs represent a major source of morbidity and mortality across most populations and affect virtually all organ systems and physiologic processes. Drug-induced allergies, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN; also known as Lyell syndrome), drug-induced liver injury and agranulocytosis are associated with an array of medications used to treat a variety of human disease. These allergies, which may be benign (e.g., mild skin rash) or severe (e.g. agranulocytosis), are Type B adverse drug reactions (ADRs) that result from a specific immunologic response to a medication. As such they involve HLA markers. Before the widespread use of GWAS, many HLA loci were discovered to be markers of drug-induced allergic reactions in candidate gene studies, which identified the HLA variants that led to risk for allergies efficiently7. Although the powerful, unbiased approaches of GWAS were not necessary for the discovery of HLA loci associated with drug-related allergies, GWAS provided some advantages: for example, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in linkage disequilibrium with HLA variants were discovered6, and could be used as markers for the HLA risk variants, which are much more difficult to genotype.

However, the most significant achievements of PGx GWAS achievements for the prevention of ADRs have been related to the identification of non-HLA markers. Such examples include inosine triphosphatase, ITPA, a gene encoding an enzyme that is associated with protection against ribavirin-induced haemolytic anemia8; CYP2C9, which is associated with phenytoin-induced SJS and TEN9, and nudix hydrolase 15 (NUDT15), which is associated with thiopurine-induced leukopenia10. Variants in these genes have sufficiently large effect sizes (odds ratios of > 10) to offer clinical utility of diagnostics and provide new information on biological mechanisms that underlie ADRs. In the case of NUDT15, in vitro functional studies demonstrated that this hydrolase is involved in the metabolism and inactivation of thiopurine metabolites in lymphocytes and alters their cytotoxic effects. These findings have led to a new concept for intracellular pharmacokinetics of thiopurines, which can explain the susceptibility to thiopurine toxicity in patients with loss-of-function variants in NUDT15.

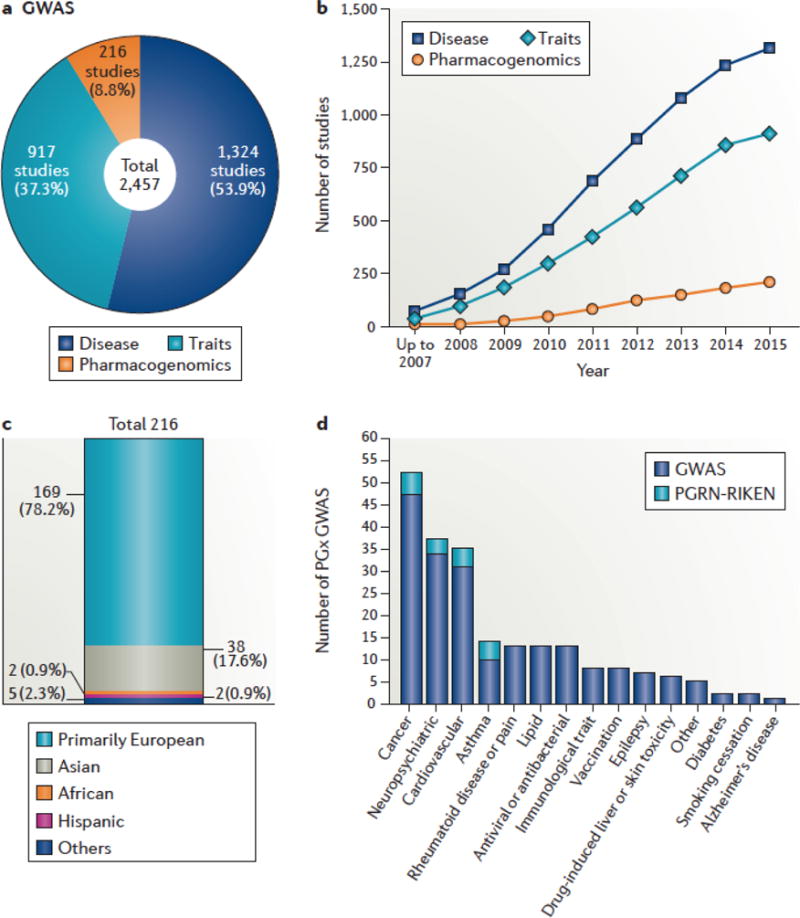

Such studies also highlight the need to conduct research on multiple ethnic groups. For example, for several years, the most notable SNPs associated with thiopurine toxicities were thought to be located in the gene that encodes thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT). However, whereas these SNPs have a large effect on individuals of European ancestry, SNPs in NUDT15 have been found to be critical for individuals of Asian descent. Clearly, more PGx GWAS focused on the identification of genes associated with drug toxicities need to be performed in all ethnic groups, in order to make better use of this powerful method for the discovery of novel toxicological mechanisms. (Figure 1, Supplemental information S1 (table)).

Figure 1. Genomewide- association studies of pharmacogenomics traits.

The number of pharmacogenomics(PGx) genome-wide association studies (GWAS) is limited, and such studies have focused on populations of European ancestry. The US National Human Genome Research Institute and European Bioinformatics Institute (NHGRI-EBI) GWAS Catalog, which was formed in 2008, was used to obtain information about the number, ethnicity and types of studies performed to date. (a) Total number of GWAS of three main human characteristics: diseases, traits and drug responses (pharmacogenomics). (b) Number of studies accumulated each year for each type of GWAS. (c) Number of PGx studies conducted in various ethnic populations. Few PGx GWAS have involved non-European populations, with only two reported in individuals of Hispanic ancestry and two in individuals of African ancestry. (d) The major categories of PGx GWAS. A total of 216PGx GWAS were annotated in the GWAS Catalog. The four major PGx GWAS focus on drugs used in the treatment of cancer, neuropsychiatric disease, cardiovascular disease and asthma. Among the 216PGx GWAS, 145 and 69 studies focus on drug responses and toxicities or adverse drug events, respectively. However, only two of the studies focus on drug levels. There are fewer PGx GWAS of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) compared with drug efficacy (69 versus 145); many of the PGx GWAS of ADRs are limited to hypersensitivity reactions. A full list of the PGx studies annotated in the GWAS Catalog is available in Supplementary information S1 (table). With a total of only 216PGx GWAS listed in the GWAS Catalog, these observations reveal major gaps in PGx GWAS. There is a need for PGx GWAS across the range of pharmacological agents and in non-European populations.

Challenges limiting PGx GWAS

PGx GWAS, and particularly PGx GWAS focused on ADRs and in minority populations, lag far behind GWAS of common diseases. A probable explanation is that large sample sizes, which are needed to provide statistical power for meaningful associations in GWAS, are more difficult to obtain for PGx GWAS. In GWAS, a stringent threshold for statistical significance (that is, P<5 × 10−8) is applied for examined variants; moreover, GWAS results must be replicated in independent cohorts.

Unfortunately, there are several factors that contribute to the challenge of obtaining large sample sets in PGx research. For the treatment of most common diseases, many drugs are available; therefore, the number of patients on a particular drug probably only represents a fraction of patients with that specific disease diagnosis. In addition, drug response measurements frequently need to include both baseline and on-treatment measurements to assess the effect of the drug, further limiting the number of patients that qualify for a PGx GWAS. Finally, replication studies with the same drug response measurements need to be conducted on patients who receive the same drug. Obtaining an adequate number of samples from patients who have experienced an ADR represents an even greater challenge for PGx GWAS, as such individuals probably represent a subset of patients on a particular drug. In the United States, these issues are amplified for minority populations, in which numbers are already lower than for populations of European ancestry.

Thus, there are substantial challenges for PGx GWAS to accrue sufficient numbers of samples from appropriately characterized replication cohorts, minority populations and patients with ADRs.

Large consortia accelerate PGx GWAS

To obtain the necessary samples associated with drug response phenotypes, large collaborations, similar to those established for human disease1, are critical for the success of PGx GWAS. Indeed, international consortia of investigators focused on PGx GWAS of several drugs such as warfarin, tamoxifen, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and metformin have been established, and have contributed to identifying the genetic factors that underlie variation in efficacy and toxicity among patients who receive these drugs (Table 1).

Table 1.

A list of 14 consortia that focus on pharmacogenomics research

| Consortium for Pharmacogenomics | Link | Focus | Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) | https://cpicpgx.org | Clinical Implementation | USA |

| Consortium on Breast Cancer Pharmacogenomics (COBRA) | http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/COBRA/ | Genetic variations of ER and enzymes | USA |

| Drug-Induced liver Injury Network (DILIN) | http://www.dilin.org | GWAS and sequencing | USA |

| Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) | No website | Clinical Implementation | The Netherlands |

| International Clopidogrel Pharmacogenomics Consortium (ICPC) | https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/projects | GWAS | International |

| International SSRI Pharmacogenomics Consortium (ISPC) | https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/projects | GWAS | International |

| International Tamoxifen Pharmacogenomics Consortium (ITPC) | https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/projects | GWAS | International |

| International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics Consortium (IWPC) | https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/projects | GWAS | International |

| Metformin Genetics Consortium | No website | GWAS | International |

| PGRN-RIKEN | http://www.pgrn.org/pgrn-riken.html | GWAS and sequencing | International |

| Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) | http://www.pgrn.org/ | Pharmacogenomics Research | USA |

| The Genome-based Therapeutic Drugs for Depression (GENDEP) | http://gendep.iop.kcl.ac.uk/results.php | GWAS | International |

| The International Consortium on Lithium Genetics (ConLiGen) | http://www.conligen.org | GWAS | International |

| Ubiquitous Pharmacogenomics (U-PGx) | http://upgx.eu | Clinical Implementation | Europe |

ER, oestrogen receptor; GWAS, genome-wide association studies

The largest subset of pharmacological classes of PGx GWAS represents anticancer drug therapies (Figure 1d), which accounts for approximately 25% of PGx studies reported in the GWAS Catalog to date. Such studies have been facilitated by a long-standing infrastructure for oncology clinical trials funded by the US National Cancer Institute (NCI), generally referred to the ‘cooperative groups’. Coordinated through the NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (NCI-CTEP), the groups focus on phase III studies of FDA-approved and investigational agents in common malignancies, such as breast, colorectal, lung and prostate cancer.

Although the cooperative groups facilitate the collection of samples and phenotype information from patients on anticancer drugs, reliable genotyping, as well as expertise in pharmacology and statistics, is required to optimize these studies. To this end, a large international consortium, PGRN-RIKEN, was established in 2008 and continues as an activity of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) Hub. To date, PGRN-RIKEN has conducted 37 PGx GWAS and has supported the largest number of PGx studies reported in the GWAS catalog: 16 (7.4%) of 216 total PGx GWAS (see Figure 1d).

Outlook

During the twenty-first century, ‘pharmacogenetics’, which has evolved to become ‘pharmacogenomics’, has involved a migration from studies of candidate genes to the application of genome-wide research strategies, especially GWAS. The results of PGx GWAS have served to identify biomarkers for drug response, and in conjunction with functional genomic studies, have provided novel insights into both disease pathophysiology and molecular pharmacology. Notably, none of this progress would have been possible without collaboration across institutional and national boundaries. The success of PGRN-RIKEN and other collaborations makes a strong case for the creation and continuation of collaborative efforts.

Clearly, more PGx GWAS are needed, both for the identification of clinically actionable biomarkers for therapeutic and adverse drug responses and for the generation of novel mechanistic hypotheses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the following: U24 GM115370, R01 GM117163, R01 DK103729 (K.M.G. and S.W.Y.); R01 GM28157, U19 GM61388, U54 GM114838 (R.M.W.)

Footnotes

FURTHER INFORMATION

GWAS Catalog: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/

More than 800 medicines and vaccines in clinical testing for cancer offer new hope to patients: http://phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/oncology-report-2015.pdf

NIH PGRN Hub: http://www.pgrn.org/riken-publications.html

PhRMA: http://www.phrma.org

Psychiatric Genomics Consortium: https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

See online article: S1 (table)

References

- 1.Dolgin E. Massive schizophrenia genomics study offers new drug directions. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2014;13(9):641–2. doi: 10.1038/nrd4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM, Hulot JS, Mega JL, Roden DM, Klein TE, Sabatine MS, Johnson JA, Shuldiner AR, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation C Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2013;94(3):317–23. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muir AJ, Gong L, Johnson SG, Lee MT, Williams MS, Klein TE, Caudle KE, Nelson DR, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation C Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for IFNL3 (IL28B) genotype and PEG interferon-alpha-based regimens. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2014;95(2):141–6. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin MA, Hoffman JM, Freimuth RR, Klein TE, Dong BJ, Pirmohamed M, Hicks JK, Wilkinson MR, Haas DW, Kroetz DL, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation C Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for HLA-B Genotype and Abacavir Dosing: 2014 update. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2014;95(5):499–500. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leckband SG, Kelsoe JR, Dunnenberger HM, George AL, Jr, Tran E, Berger R, Muller DJ, Whirl-Carrillo M, Caudle KE, Pirmohamed M, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation C Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for HLA-B genotype and carbamazepine dosing. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2013;94(3):324–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tohkin M, Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Sugiyama E, Kurose K, Nishikawa J, Hasegawa R, Aihara M, Matsunaga K, Abe M, Furuya H, Takahashi Y, Ikeda H, Muramatsu M, Ueta M, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S, Ikezawa Z, Japan Pharmacogenomics Data Science C A whole-genome association study of major determinants for allopurinol-related Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japanese patients. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2013;13(1):60–9. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illing PT, Vivian JP, Purcell AW, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. Human leukocyte antigen-associated drug hypersensitivity. Current opinion in immunology. 2013;25(1):81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Ge D, Gumbs CE, Urban TJ, Shianna KV, Little LD, Qiu P, Bertelsen AH, Watson M, Warner A, Muir AJ, Brass C, Albrecht J, Sulkowski M, McHutchison JG, Goldstein DB. ITPA gene variants protect against anaemia in patients treated for chronic hepatitis C. Nature. 2010;464(7287):405–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang SK, Hong M, Baek J, Choi H, Zhao W, Jung Y, Haritunians T, Ye BD, Kim KJ, Park SH, Park SK, Yang DH, Dubinsky M, Lee I, McGovern DP, Liu J, Song K. A common missense variant in NUDT15 confers susceptibility to thiopurine-induced leukopenia. Nature genetics. 2014;46(9):1017–20. doi: 10.1038/ng.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung WH, Chang WC, Lee YS, Wu YY, Yang CH, Ho HC, Chen MJ, Lin JY, Hui RC, Ho JC, Wu WM, Chen TJ, Wu T, Wu YR, Hsih MS, Tu PH, Chang CN, Hsu CN, Wu TL, Choon SE, Hsu CK, Chen DY, Liu CS, Lin CY, Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Takahashi Y, Nakamura R, Azukizawa H, Shi Y, Wang TH, Chuang SS, Tsai SF, Chang CJ, Chang YS, Hung SI, Taiwan Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reaction C, Japan Pharmacogenomics Data Science C Genetic variants associated with phenytoin-related severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Jama. 2014;312(5):525–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.