Abstract

Background

HIV-infected individuals transitioning from incarceration to the community are at risk for loss of viral suppression. We compared the effects of imPACT, a multi-dimensional intervention to promote care engagement after release, to standard care on sustaining viral suppression after community re-entry.

Methods

This trial randomized 405 HIV-infected inmates being released from prisons in Texas and North Carolina with HIV-1 RNA levels <400 copies/mL to imPACT versus standard care. The imPACT arm received motivational interviewing pre- and post-release, referral to care within 5 days of release, and a cellphone for medication text reminders. The standard care arm received routine discharge planning and a cellphone for study staff contact. The primary outcome was the difference between arms in week 24 post-release viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL) using intent-to-treat analysis with multiple imputation of missing data.

Results

The proportion with 24-week HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml was 60% and 61% in the imPACT and standard care arms, respectively (odds ratio for suppression 0.95 (95% CI, 0.59 to 1.53)). By week 6 post-release, 86% in the imPACT arm versus 75% in the standard care arm attended at least one non-emergency clinic visit (P = 0.02). At week 24, 62% in both arms reported not missing any antiretroviral doses in the past 30 days (P >0.99).

Conclusions

Higher rates of HIV suppression and medical care engagement than expected based on prior literature were observed among HIV-infected patients with suppressed viremia released from prison. Randomization to a comprehensive intervention to motivate and facilitate HIV care access after prison release did not prevent loss of viral suppression. A better understanding of the factors influencing prison releasees' linkage to community care, medication adherence, and maintenance of viral suppression is needed to inform policy and other strategic approaches to HIV prevention and treatment.

Introduction

The efficacy of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in preventing secondary HIV transmission coupled with the recognition that many HIV-infected persons in the US are undiagnosed or not in care have led to a strategy to expand HIV testing, and strengthen the uptake and continued use of HIV therapy for those infected (1-9). This multifaceted seek, test, treat, and retain (STTR) approach to HIV prevention is readily applied to correctional settings, such as prisons, where the prevalence of HIV infection is several times that of the general population, and routine HIV screening provides opportunities for detection and treatment during incarceration (10-13).

While HIV testing is commonplace in US prisons and ART is freely accessible to inmates (13), retention in HIV care following prison release has been reported to be less successful. In an analysis of ART prescriptions fill records for 2,115 individuals released from state prison in Texas from 2004 to 2007, 55% with a plasma HIV RNA level below the limits of assay detection just prior to release, only 30% of releasees had filled their ART prescription by 60 days following community re-entry (14). Post-release HIV RNA level data were not collected. Achievement of an undetectable plasma HIV RNA level was the primary outcome of a substudy of 94 HIV-infected patients with a history of opioid dependence participating in a larger randomized trial of directly observed administration of ART following prison release in Connecticut (15). At baseline, 54% had an undetectable viral load and this was largely unchanged by 24 weeks post-release when 58% had viral suppression. The highest rate of controlled viremia was among those who were maintained on buprenorphine (82%) and lowest rate was observed in the control arm that did not receive substitution therapy (55%). There was no significant effect of directly observed administration of ART on viral suppression in this or the larger parent trial. Studies of HIV-infected prisoners who were released and then re-incarcerated provide additional virologic outcome data following prison release and in these, viral suppression at re-incarceration has been found to be the exception rather than the rule (16, 17).

Interventions to support HIV care, ART adherence, and viral suppression following prison release also have been explored. Zaller and colleagues described the successful implementation of a comprehensive case-management program linking over 95% of incarcerated HIV-infected prison releasees to community care and services in Rhode Island (18). However, a controlled trial of a similar intervention that enrolled 104 HIV-infected prisoners released in North Carolina found no significant difference in 24-week rates of community medical care access between those randomized to the intervention (92%) and to standard discharge planning conducted by prison staff (89%) (19). Virologic outcomes were not assessed.

Almost all of the previous research that has examined HIV-related clinical outcomes following prison release in the United States (US) was conducted a decade ago, when ART tended to be more cumbersome and less forgiving of all but high-level adherence. Further, individuals with suppressed and detectable viremia at the time of prison release were typically enrolled - mixing the maintenance of viral suppression with the achievement of viral suppression following community re-entry.

Given the limitations of the research published to date and the importance to successful HIV prevention of developing interventions that effectively support the continuity of HIV care and maintenance of ART through the transition from imprisonment to community re-entry, we developed a multi-dimensional intervention rooted in the STTR approach, called imPACT (Individuals Motivated to Participate in Adherence, Care and Treatment) (20). Designed to promote engagement in HIV care after release for HIV-infected prisoners, imPACT consisted of three main components: motivational interviewing before and after release, pre-release needs assessment and community medical care link coordination, and cell phone provision with texted reminders prior to each antiretroviral medication dose. By design, the focus of the imPACT intervention was linkage to community clinics, where assessments of need could be conducted and supportive services provided.

In a randomized controlled trial conducted in Texas (TX) and North Carolina (NC) - states that combined incarcerate approximately 1 in 7 of all prison inmates in the US - the imPACT intervention was compared with the standard discharge planning for maintaining viral suppression in HIV-infected individuals released from state prison in both states.

Methods

Participants and Sites

Eligible participants were HIV-infected men and women, age 18 years and older incarcerated within the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) or North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS) prison, treated with ART with a recorded plasma HIV RNA level of < 400 copies/mL within the past 90 days, and expected to be released to the community within approximately 12 weeks. Additionally, participants were required to be English-speaking and, to minimize risk to study staff, to have not been convicted of violent offenses such as those related to sexual assault, serious injury, or death. All had to be willing and able to provide written informed consent.

Study screening and recruitment occurred at prison medical clinics during routine visits or in a secured room within the prison unit. Interested patients met in a secure but private area with a research associate, who, as part of the informed consent process, explained the study and answered questions regarding participation.

The institutional review boards at Texas Christian University and the University of North Carolina, as well as human subjects committees at both prison systems and the US Office of Human Research Programs (OHRP), approved this research. Recognizing that those enrolled are a vulnerable population, the study team undertook a number of measures to minimize the risk of coercion. These included developing a script that explained in simple terms that participation was voluntary and conferred no special privileges or consideration. In addition, discussion of the study and the consent process occurred in private, without correctional staff present. Lastly, we developed and administered a short set of questions to determine whether the patient understood the study rationale, procedures and voluntary nature.

Intervention and Randomization

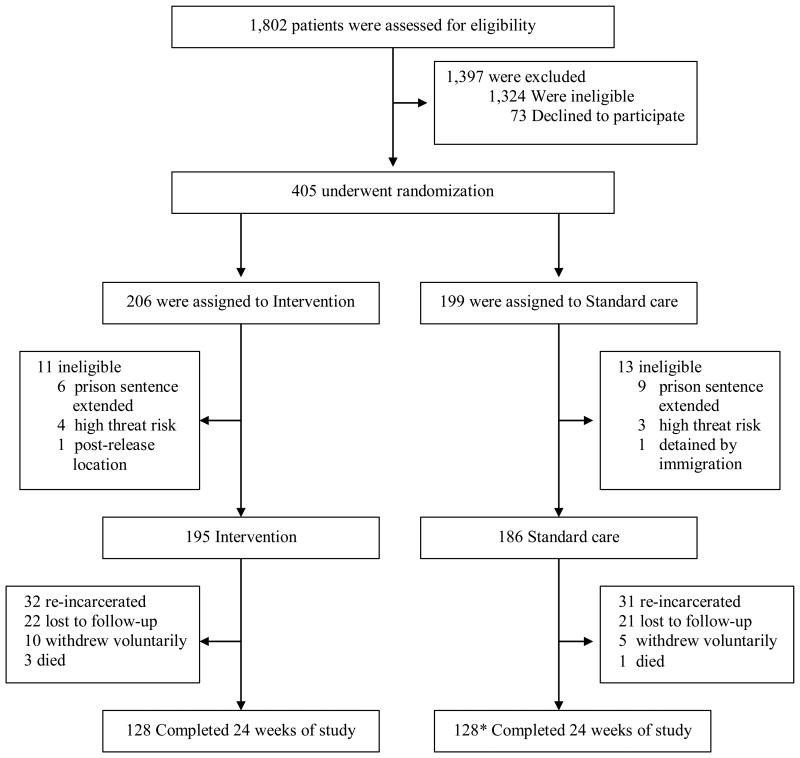

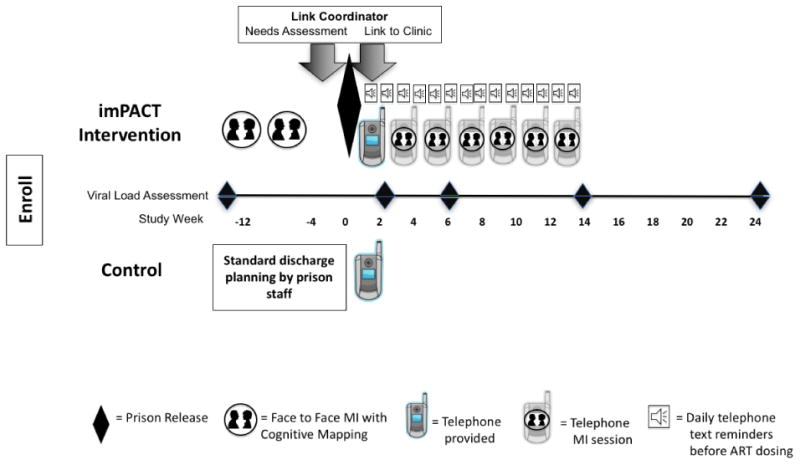

Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 following the completion of baseline data collection to: standard of care discharge planning versus the imPACT intervention. Randomization was stratified by state. Figure 1 details events in both the standard of care and the intervention study groups.

Figure 1.

Screening, Enrollment and Follow-up.

*Includes 3 participants who completed week 24 but for whom plasma HIV RNA was unable to be performed.

Standard of Care

In both states, over 90% of inmates are tested at prison entry and HIV care, including ART, is provided to infected inmates at no cost. Prison staff in both states routinely perform discharge planning before release which included referrals to community clinics, arrangements for housing, and other services when available and based on their assessments of need.

In both states, the prison system provided a supply of antiretroviral medications to HIV-infected releasees at the time of release (per state policy: a 10-day supply in Texas and a 30-day supply in North Carolina).

Cellphone Distribution

Standard of care participants were provided with a flip-type cell phone immediately after release to maintain participant contact and enhance retention. In both study arms and in both states, cellphones were used to remind participants of upcoming study visits, and to conduct unannounced pill counts.

imPACT Intervention

Details regarding the basis and development of the imPACT intervention have been described elsewhere (20). Briefly, the imPACT intervention adapted and combined existing theoretically-rooted interventions (21-23) to be influential at the individual, clinic/institutional, and community levels in accordance with the Social Ecological Framework (24, 25). Conceptually, the imPACT intervention was designed to enhance motivation and self-efficacy to attend community HIV care visits and adhere to ART following release, while also reducing barriers to such care. The overarching objective of the intervention was to maintain viral suppression following prison release, and entry into community medical care was presumed to be the critical mediator of this outcome. The intervention was finalized following formative research conducted with prison-based and community service providers as well as former inmates living with HIV infection, as has been previously reported (26, 27). The main elements of the tested intervention included the following:

Motivational Interviewing Augmented by Cognitive Mapping

A trained motivational interviewing counselor conducted two individual face-to-face sessions in prison (lasting approximately 1 hour each) followed by six additional sessions scheduled approximately every two weeks over 14 weeks via telephone after release. Each in-person and phone motivational interviewing session was conducted using a stepwise guide based on motivational interviewing interventions that we had developed previously (21, 28-31). As a part of the session, the motivational interviewing counselor and participant together created graphic cognitive ‘maps’ to visually represent and connect thoughts, feelings, and actions evoked, as well as clarify participant goals post-release. Before each in-prison motivational interviewing session, participants were shown one of two 15-20 minute videos that were produced specifically for the trial and provided an orientation to the intervention and prepared the participant for each upcoming motivational interviewing session. Following release, the same motivational interviewing counselor who met with the participant in prison conducted the six phone sessions.

Needs Assessment and Brief Link Coordination

Within 4 weeks prior to release, a study Link Coordinator met with the participant one time to conduct an evaluation of anticipated needs following community re-entry, using a standardized set of questions (22). The Link Coordinator scheduled a community clinic appointment for the participant and submitted applications for state and pharmaceutical company drug assistance programs, when needed. Link Coordinators conducted encounters with the participant in person pre-release and by telephone post-release. If the initial clinic appointment was not kept by the participant, the Link Coordinator was instructed to make one additional clinic appointment on behalf of the participant. All interactions between the Link Coordinator and the participant ceased either once the arranged clinic appointment was attended or after the second missed appointment.

Cellphone Distribution and Text Message Antiretroviral (ARV) Medication Reminders

Each participant randomized to the imPACT intervention was given a flip-type cellphone by a research assistant as soon as possible (typically within 3 days) after release. These research assistants programed each study cellphone with up to ten telephone numbers for the participant, including those of the Link Coordinator, MI Counselor, research assistant, community case manager (if applicable), and community clinic and others selected by the participant. In addition, the phones were used to send medication reminder text messages to the participant 15 minutes before each scheduled antiretroviral dose for the first 12 weeks post-release to support adherence. Text messages timing and wording were customized to the participant's ARV regimen and preference at the time of release (e.g., take your vitamins) and were followed in 15 minutes by a query text asking if the medication was taken (e.g., Did you take your vitamins?) and instructions to press 1 for ‘yes’ and 2 for ‘no’. When the response was ‘yes’, a text thanking the participant for responding was sent. When the response was ‘no’ or in cases of no response, the query text was resent once again 30 minutes later.

Assessments and Outcomes

Participants completed a baseline study visit in prison and then a pre-release visit approximately 2-4 weeks before anticipated release. Immediately after release, research assistants met briefly with all participants to deliver the study cellphone, study staff business cards, a pill counting tray and spatula, and a locking backpack with toiletries and condoms. Post-release study visits were scheduled at weeks 2, 6, 14, and 24 and were conducted at public locations selected by the research assistant and the participant.

HIV Viral Load

The proportion of participants in each study arm with a plasma HIV-1 RNA level below 50 copies/mL at 24 weeks after release was the primary outcome of the trial. Blood was collected at each of the post-release study visits (weeks 2, 6, 14, and 24) for plasma HIV-1 RNA PCR levels. All blood specimens were delivered to Laboratory Corporation of America (Labcorp) and were analyzed in batches. Baseline HIV RNA levels and CD4+ cell counts were those last obtained as part of clinical care during incarceration within the 60 days prior to study entry.

Clinical Care Engagement

At each study visit, in surveys administered through audio computer assisted self-interviews (ACASI), participants were asked to list all of the outpatient encounters they had since the last study visit and to characterize whether the encounter was for HIV care or not (e.g., substance abuse treatment). A participant who indicated that they attended at least one non-emergency outpatient medical clinic visit within 6 weeks of release was considered engaged in clinical care.

Other Variables

At baseline, demographic information was collected and psychological functioning and mental health status assessed using the TCU PSY Form and TCU HLTH Form, both previously demonstrated to have high reliable and validity in this population (32, 33). Medication adherence was self-reported using a 30-day Visual Analog Scale (34). Prior substance use history was obtained at the baseline visit using the AUDIT (35). In TX, the TCU Drug Screen II Form, previously found to be highly accurate for detecting substance use disorders among prison inmates (32, 36, 37), was administered; in NC, inmates receive the SASSI (38) routinely on admission. Medical and incarceration histories were collected through record review. Following release, access to care, service utilization, health insurance coverage, and incarceration status were assessed at each visit.

Statistical Methods

The primary endpoint, the proportion of participants with 24-week HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml, was compared across the two randomized arms using the intention-to-treat principle. Additionally, we report the odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) estimated from a logistic regression model fit by maximum likelihood, an unadjusted model was fit as well as a model adjusted for site and baseline HIV-1 RNA level. The primary analysis employed multiple imputation, because we anticipated nontrivial missing data (39, 40). We used a multivariate normal model, in the SAS procedure MI to impute missing HIV-1 RNA levels 50 times and combined imputations using Rubin's rule (41). Variables included in the imputation model were: age, sex, race/ethnicity, CD4+ cell count, length of incarceration, marriage status, education, substance use, measures of health and well-being and psychological distress - all measured at baseline. We also performed a complete case analysis which only included participants with an available 24-week HIV-1 RNA level.

We performed bounded analyses using simple imputation of missing outcome data where we first assumed that all 24-week missing HIV-1 RNA levels among the intervention arm were less than 50 copies/mL and all missing values among the standard of care arm were greater than 50 copies/mL (best case scenario). Secondly we assumed that all missing outcome data among the intervention arm were greater than 50 copies/mL and all missing values among the standard of care arm were less than 50 copies/mL (worst case scenario). For the primary ITT analyses we also assessed alternate HIV-1 RNA endpoints including the comparison of continuous plasma HIV-1 RNA levels and viremia-copy-years from randomization through week 36 across the two randomized arms. Viremia copy-years is the number of copies of HIV-1 RNA per mL over time and specifics of how it is calculated have been previously described (42). Briefly, the HIV-1 RNA burden for each time interval between 2 consecutive HIV-1 RNA values was calculated by multiplying the mean of the two HIV-1 RNA values by the time interval. The copy × y/mL for each time interval of a participant's HIV-1 RNA curve was then summed to calculate viremia copy-years.

Engagement in medical care at week 6 following release and across study follow-up were also compared. We used time-to-event methods including Kaplan-Meier survival curves to describe the time to the first non-emergency clinical visit following release. Incidence rates of attending a clinic visit were calculated as the number of visits attended divided by person-time under observation, and incidence rate differences were calculated with measures of precision based on a Poisson distribution.

The target sample size of the study (n=514) was based on the primary endpoint comparison of the proportion of participants with 24-week HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml. This estimate assumed 80% statistical power, a 2-sided alpha of 0.01, a 15% absolute difference in the primary outcome between the intervention and control arms, 20% loss to follow-up, and was based on performing a complete case analysis. Our final sample size (n=405) was lower than projected due to funding restrictions, and corresponded to approximately 70% statistical power relying on the same assumptions. Since we imputed missing outcome data, our projected statistical power would have been somewhat greater than estimated. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (The SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All P-values were two-sided, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Participant Accrual, Enrollment, and Disposition

Enrollment began March 2012 and the last study visit was completed February 2015. A total of 405 participants were enrolled and randomized in TX (n=242) and NC (n=163) (Figure 2). Of these participants, 24 (6%) were withdrawn as they became ineligible, most due to an extension of prison sentence or by becoming recognized as a threat to study staff safety that was too high for study participation. Of the two others excluded, one planned to move to a location outside the study boundaries, and the other was detained by immigration. Of the remaining participants, 195 were randomized to receive the intervention and 186 participants to receive standard of care. Overall, 125 (33%) participants did not complete 24 weeks of post-release study participation, 67 (34%) in the intervention arm and 58 (31%) in the standard of care arm. The primary reasons for study non-completion were comparable across randomized arms and included re-incarceration and loss to follow-up (Figure 2).

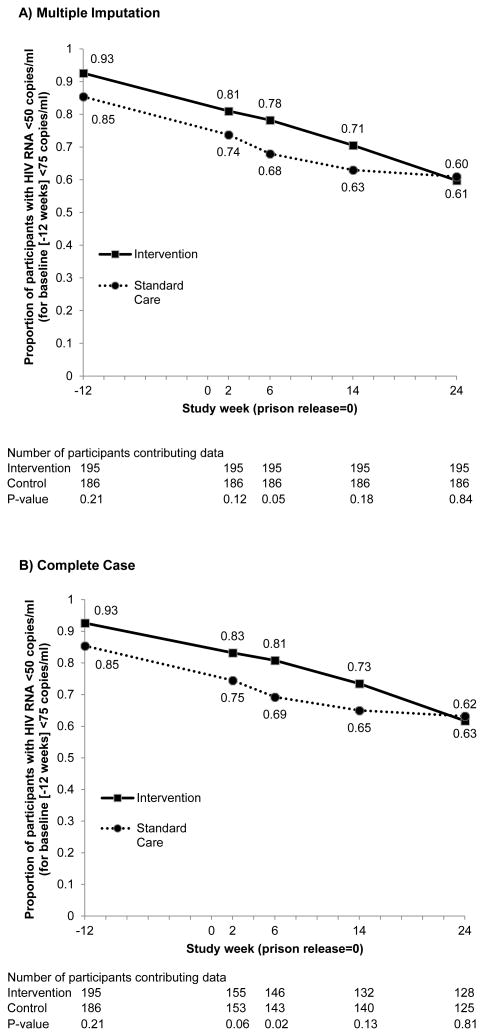

Figure 2.

HIV RNA During Follow-up Between Groups, According to (A) Complete Case and (B) Multiple Imputation for Missing Data.

Baseline Characteristics

The participants were mostly black men, and most had been incarcerated less than 1 year (Table 1). The median baseline CD4+ cell count was 505/mm3 (Interquartile range [IQR], 328 to 724). The median age was 44 years (IQR, 35 to 49), 64% had never married, 59% completed high school (or equivalent), 31% reported high or very high psychological distress, and two-thirds reported a history of substance use. Baseline characteristics were not statistically significantly different between the two randomized arms.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Intervention | Standard Care | All Patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 195) | (N = 186) | (N = 381) | |

| Age - year | |||

| Median | 44 | 43 | 44 |

| Interquartile range | 35 - 49 | 34 -50 | 35 - 49 |

| Male sex - no. (%) | 147 (79) | 150 (77) | 297 (78) |

| Race - no. (%) | |||

| White | 46 (24) | 39 (21) | 85 (22) |

| Black | 121 (62) | 128 (69) | 249 (65) |

| Other | 28 (14) | 19 (10) | 47 (12) |

| Hispanic - no. (%) | 7 (6) | 12 (9) | 27 (7) |

| CD4 cell count/mm3† | |||

| Median | 490 | 511 | 505 |

| Interquartile range | 339 - 709 | 300 - 734 | 328 - 724 |

| HIV RNA copies/ml - no (%)* | |||

| <50 | 75 (38) | 60 (32) | 135 (35) |

| <75 | 106 (54) | 99 (53) | 205 (54) |

| <200 | 9 (5) | 15 (8) | 24 (6) |

| <400 | 4 (2) | 12 (6) | 16 (4) |

| >/=400 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| History of substance use – no. (%)† | 127 (68) | 116 (66) | 243 (67) |

| Incarceration length - year† | |||

| Median | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.81 |

| Interquartile range | 0.49 - 1.82 | 0.50 - 1.92 | 0.49 - 1.88 |

| Health and wellbeing - no (%) | |||

| Excellent | 58 (30) | 53 (28) | 111 (29) |

| Very good / good | 101 (52) | 93 (50) | 194 (51) |

| Fair / poor | 36 (18) | 40 (22) | 76 (20) |

| Psychological distress - no (%) | |||

| < High | 129 (66) | 133 (72) | 262 (69) |

| High | 22 (11) | 24 (13) | 46 (12) |

| Very high | 44 (23) | 29 (16) | 73 (19) |

| Education - no (%) | |||

| Some high school | 76 (39) | 80 (43) | 156 (41) |

| High school / GED | 73 (37) | 61 (33) | 134 (35) |

| Some college / trade school | 46 (24) | 45 (24) | 91 (24) |

| Marital Status - no (%) | |||

| Married | 33 (17) | 24 (13) | 57 (15) |

| Formerly married | 47 (24) | 35 (19) | 82 (22) |

| Never married | 115 (59) | 127 (68) | 242 (64) |

| Functional health literacy - no (%)† | |||

| Inadequate | 7 (3) | 5 (4) | 12 (4) |

| Adequate | 13 (9) | 8 (6) | 21 (8) |

| Functional | 121 (86) | 122 (90) | 243 (88) |

Categories for HIV RNA are not mutually exclusive as they represent the assay lower limit of detection, however, each participant is counted only once.

Missing values for CD4 cell count (n=1), substance use (n=17), incarceration length (n=6), health literacy (n=105).

Suppression of Plasma HIV-1 RNA

The ITT estimated proportion with 24-week HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml was 60% and 61% in the intervention and standard care arms, respectively. The corresponding estimated odds ratio for HIV-1 RNA suppression at week 24 post-release comparing intervention to standard of care was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.59 to 1.53) (Table 2). This ITT estimate was unaltered after adjustment for site and baseline HIV-1 RNA level. Overall 256 (67%) participants completed study follow-up through week 24 post-release, and 253 had available week 24 HIV-1 RNA levels (2 HIV-1 RNA measures were unavailable and 1 had insufficient volume for quantitation). The estimated intervention effect based on the complete case analysis was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.56 to 1.56).

Table 2.

HIV RNA at 24 Weeks Post-Release Between Groups, According to Multiple Imputation for Missing Data and Adjustment for Site and Baseline HIV RNA.

| Analysis Cohort* | 24 Week HIV RNA <50 copies/ml Percent (No. of Participants) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Standard Care | ||

| ITT (Multiply-imputed) | 60 (195) | 61 (186) | |

| Unadjusted | 0.95 (0.59 to 1.53) | ||

| Adjusted | 0.96 (0.60 to 1.55) | ||

| Complete Case | 62 (128) | 63 (125) | |

| Unadjusted | 0.94 (0.56 to 1.56) | ||

| Adjusted | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.54) | ||

Adjusted estimates are adjusted for site and baseline HIV RNA.

Our findings were also robust to including the 24 participants who were randomized but withdrawn, OR=0.97 (95% CI, 0.60 to 1.55). Results were also similar in analyses using HIV-1 RNA <400 copies/ml at week 24 as the outcome, in both the ITT multiply-imputed and complete case analyses, with OR=1.06 (95% CI, 0.63 to 1.79) and OR=1.08 (95% CI, 0.60 to 1.93), respectively. Sensitivity analyses exploring the best case scenario by replacing missing outcome data with HIV-1 RNA <50 and ≥ 50 copies/mL among the intervention and standard of care arms, respectively, produced an estimated intervention effect of OR=4.04 (2.61, 6.24). In the worst case scenario, where missing outcome data were replaced with HIV-1 RNA ≥50 and <50 copies/mL among the intervention and standard of care arms, respectively, an estimated intervention effect of OR=0.22 (95% CI, 0.14, 0.35) was produced.

At baseline and throughout study follow-up until 24 weeks post-release, the standard of care arm was less likely to have HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL than the intervention arm, although these differences were not statistically significant with the exception of week 6 post-release (Figure 3). These results persisted after adjustment for differences at baseline in the proportion with a plasma HIV-1 RNA level <50 copies/mL. Viremia-copy-years was also comparable for the intervention and standard care arms with a median of 3.6 log10 copy × year/ml (Interquartile range [IQR], 3.4 to 4.8) and 3.7 (IQR, 3.4 to 5.7), in the intervention and standard of care arms, respectively (P = 0.36).

Figure 3.

Timeline of events for intervention and control study arms.

Engagement in Clinical Care after Release

By week 6 after release, 323 participants completed at least one study visit and, among these participants, 138 (86%) in the intervention arm versus 122 (75%) in the standard of care arm attended at least one non-emergency medical clinic outpatient visit (P = 0.02). The 260 patients with at least one medical clinic visit reported 438 non-emergency clinical visits, with 71% at an HIV clinic. Restricting to HIV clinic visits, 108 (67%) and 107 (66%) in the intervention versus standard care arms, respectively attended at least one HIV clinic visit by week 6 post-release (P = 0.91).

During the 24 week study follow-up, the average number of non-emergency medical clinic visits each participant reported while under study observation was 2.9 and 2.8 for the intervention versus the standard of care participants, respectively (P = 0.53). Results were comparable when considering visits designated by the participant as occurring in HIV clinics with 2.2 versus 2.1 visits occurring per 24 weeks in intervention and standard of care groups, respectively (P = 0.31). The median time to first medical clinic appointment following release was slightly but statistically significantly shorter in the intervention arm compared to the standard of care arm (10 days versus 13 days, P = 0.03).

At 24 weeks post-release, a similar proportion of participants in the intervention and control arms reported having any health insurance coverage (58% and 63%, respectively, P = 0.42). Participants reported having Medicaid (42%), Medicare (23%), Private insurance (11%), Military health care (3%), and another type of government sponsored health plan (42%), with most participants reporting only one type of health insurance (79%). There was no difference in the primary outcome of being virologically suppressed at 24 weeks by insurance coverage, with 59% and 67% of those with and without insurance respectively having HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml (P = 0.18).

Self-reported adherence at week 24 post-release was also comparable across study arms, with 62% reporting not missing any ART doses in the past 30 days in both the intervention and standard of care arms (P > 0.99). However, virologically suppressed participants were more likely to report perfect adherence in the past 30 days in comparison to those not virologically suppressed (70% versus 48%, respectively, P <0.01).

Completion of intervention components

All but 5 participants in the intervention arm completed the two in-prison motivational interviewing sessions. Those who did not complete motivational interviewing were released sooner than expected, became ineligible, or were unavailable due to prison lock-down. All but 2 of those in the intervention arm completed the face-to-face pre-release meeting with the study Link Coordinator. Cellphones were provided to 187 (95.8%) of the intervention participants (and 180 (96.8%) of the standard of care participants); those immediately lost to follow-up after release or who were residing in a community facility that disallowed cellphones were not provided a cellphone.

Post-release, fidelity to the six phone-based motivational interviewing sessions ranged from 83.6% for the first session to 56.4% for the last session. The median number of post-release motivational interviewing sessions was 3.9.

Discussion

In this first randomized trial of an intervention to maintain control of viremia among HIV-infected men and women being released from prison, we found higher levels of viral suppression and care engagement than expected based on findings of prior studies of prison and jail releasees (14-17, 19, 43). Approximately 60% of participants had an undetectable plasma HIV RNA 24 weeks after release and close to 80% attended at least one community clinic appointment. In contrast, Baillargeon and colleagues reported that just 18% of HIV-infected men and women released from TX state prisons between 2004 and 2007 filled an ART prescription 30 days after release, increasing to only 30% by 60 days (14). Further, in a sub-analysis of 1,750 of the releasees returning to the greater Houston area, 28% had a record of attending an HIV clinic by 90 days after release (44).

However, unlike the imPACT trial, the study by Baillargeon and colleagues included those without as well as with viral suppression at the time of release. Individuals unable to achieve control of their HIV infection in prison can be expected to face considerable challenges doing so in the less structured environment of their community. While less than half of the HIV-infected individuals released from the TX prison system during the period of study had achieved an undetectable viral load during incarceration, those that did had a significantly higher likelihood of filling their ART prescription during the three-month post-release observation period. As ART fill rates were greater in this subgroup and increased over time following release, it is conceivable that a substantial proportion of those who left prison with an undetectable viral load filled their HIV medications prescription at six months post-release.

It is also notable that the rates of viral suppression Springer and colleagues reported in their study of prison releasees in New Haven with opioid dependency were comparable to those found in the imPACT trial, with 55% of the control arm having an undetectable HIV RNA level at week 24 after their release (15). In that study, 73% had a plasma HIV RNA level <400 copies/mL at baseline and, again, undetectable viremia at study entry was strongly associated with viral suppression at 24 weeks.

In the imPACT Trial, those randomized to a comprehensive intervention - designed to enhance motivation and self-efficacy to access community HIV care, minimize barriers to such care, and support ART adherence - were no more likely to maintain viral suppression than those receiving standard pre-release discharge planning only. Specifically, analyses including multiple imputation of missing HIV-1 RNA levels found similar rates of viral suppression and failed to detect a significant difference in the primary outcome between the study arms. Participants in both study groups experienced a steady and similar loss of pre-release viral suppression after release. Likewise, viremia-copy-years, which quantifies the cumulative HIV-1 RNA exposure over time, was similar between the study groups. Approximately a third of participants in each study arm did not contribute data at the 24-week post-release time point and in our primary intent-to-treat analysis we used multiple-imputation to impute missing values. The majority of these participants were re-incarcerated and it is possible, if not likely, that many of those returning to prison re-established suppression of HIV. In analyses that excluded those who were re-incarcerated or lost to follow-up for another reason, no statistically significant difference in 24-week post-release viral suppression was found.

Previous studies of HIV-infected releasees highlight the many challenges the formerly incarcerated face in successfully managing their HIV infection (45-47). Although most of the participants were able to maintain viral suppression over the course of post-release follow-up, the steady decline in viral suppression observed in the imPACT arm, despite its multi-level and evidence-based components, may be due to a profound counter-effect from forces that were not addressed adequately by the intervention. There may have been limitations to the support that clinical care centers could provide to these individuals - newly released from prison and saddled with co-morbid substance use and mental health disorders, poverty, homelessness, lack of social support, and myriad other challenges. HIV-infected prisoners facing multiple critical life needs that make it difficult for consistent HIV care engagement to be a top priority is a well-described phenomenon (45, 46). Our results also imply a need for interventions that directly address the chaotic social environments to which former inmates return and the pervasive and entrenched contextual factors, such as discrimination, inequality, poverty reinforcing policies and practices – collectively termed, structural violence (48) – that act as obstacles to desired outcomes such as long-lasting suppression of HIV.

Alternatively, study participation itself could have served as an intervention that promoted care engagement, ART access, and viral suppression – including in the control arm. Participants in both study arms received flip-type cell phones at release. In the case of the control participants these phones were intended to facilitate study retention. It is unclear to what extent the phones were instrumental to healthcare access. In addition, regular contact with study data collection staff could have been perceived by participants as being supportive and this too may have had a positive influence on the study outcomes.

In contrast to the absence of a difference in virologic outcomes when comparing the imPACT and standard of care arms, a significantly greater proportion of those in the intervention group accessed non-emergency community medical care within 6 weeks of release than those in the standard of care group (86% versus 75%; P = 0.02). The finding of a disconnect between access to community medical care and HIV-1 RNA levels suggests that linkage to care is insufficient when the objective is suppression of HIV viremia. A major assumption of the imPACT intervention was that linkage to community care, when combined with counseling to enhance motivation to engage in care, would lead to ART access and services that would support adherence and address unmet needs. This assumption is logical as community clinics refill prescribed ART and early linkage to HIV care has been found to improve outcomes, including viral suppression. This model of linkage to community providers of care, rather than on-going direct provision of such services, is also more sustainable. However, despite higher rates of community care engagement, those in the intervention arm fared no better virologically than those in the standard of care arm.

That engagement in HIV care does not ensure virologic success is also evident when considering the HIV Care Cascade, where the drop in the proportion of those having entered HIV care who are subsequently retained in care is the deepest of all the ‘steps’ included in this model (7). However, it is notable that in our study the mean number of clinic visits in both the intervention and standard of care groups was similar and relatively high (almost 3 visits over 24 weeks). Therefore, the progressive loss of virologic suppression observed is not clearly explained by a lack of retention in community care.

Access to clinical care does not necessarily ensure access to ART and barriers to procurement of medications or non-adherence could also explain the observed discordance between care engagement and viral suppression. Most released inmates with HIV infection are eligible for free ART provided by state AIDS Drug Assistance Programs and at follow-up, the vast majority of study participants reported having access to ART. The study population consisted largely of those with substance use problems and many with high levels of psychological distress. Such comorbidities are known risks for sub-optimal adherence to ART and HIV care and likely also complicated post-release management of HIV (49, 50).

As in any research trial, there are limitations to the study that should be considered when interpreting the results. As mentioned above, the rate of participant loss to follow-up, largely driven by re-incarceration, was, not unexpectedly, high at 33%. Viral suppression may have been maintained or regained with re-incarceration for many participants. However, HIV-1 RNA levels were not available from those who returned to prison and the balanced rates of re-incarceration between the study arms suggests that these results, if available, might raise the overall rates of viral suppression. Clinical care engagement was gauged by attending a community clinic appointment. This is acknowledged to be a minimal degree of engagement and it is reassuring that participants in both arms tended to enter care early after release and return to clinic over course of the observation period. It should be noted that this trial enrolled individuals incarcerated at state prisons and not jails. Persons leaving jail may face different hurdles to maintaining viral suppression than those re-entering their community from prison and have been reported to have even lower rates of successful linkage (43). Lastly, this trial was conducted in TX and NC and the same intervention could produce different outcomes in a different location. However, that an interaction between site (i.e., state) and the primary outcome was not observed (data not shown) supports the generalizability of the study results.

Overall, we observed higher rates of viral suppression and medical care engagement than expected based on prior literature among HIV-infected patients with suppressed viremia released from prison in TX and NC. However, randomization to a comprehensive intervention designed to motivate HIV-infected prison releasees to access HIV care after community re-entry, facilitate linkage to medical care, and support ART adherence increased engagement in medical care post-release but did not result in significantly different rates of viral suppression than randomization to standard discharge planning. Additional research is needed to better understand the factors influencing prison releasees' linkage to community care, medication adherence, and maintenance of viral suppression. The characterization of these factors is essential to inform policy and other strategic approaches to HIV prevention and treatment in the US.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01- DA030793) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K24-DA037101; K24-HD06920). Additional support was provided by the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (P30 AI-50410). The authors thank the TDCJ (including Allyson Glass, Scott Edmiston, Valla Kirby-Brossman; Frances Gattis; April Scott; Courtney Ross; Mandy Vance) and the NCDPS (including Paula Smith, Pamela Gibbs), particularly the discharge planning and clinic staff, as well as the participants for their generous contribution. We also are grateful for the dedicated assistance provided by the trial research staff including: UNC - Lisa McKeithan, Steve Bradley-Bull, Kemi Amola, Lynn Tillery, Makisha Ruffin, Angela Edwards, Katesha Peele, Neeve Neevel, Madeline McCrary, Elizabeth Roberts, Erika Hallback, MacKenzie Davis, and Sayaka Hino; TCU - Roxanne Muiruri, Molly McFatrich, Julie Gray, Scott Edmiston, Allyson Glass, Courtney Ross, Mandy Vance, Valla Kirby-Brossman, Elizabeth Larios, Laurence Misedah, and Bethany Evans. Finally, we acknowledge the inspiration provided for this research by our colleague, the late Andrew Kaplan, MD.

Footnotes

Presentations: Preliminary findings were presented at the 11th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence held May 9-11, 2016 in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Conflicts: None

Contributor Information

David Alain Wohl, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Carol E Golin, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Kevin Knight, Texas Christian University.

Michele Gould, Texas Christian University.

Jessica Carda-Auten, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Jennifer S Groves, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Sonia Napravnik, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Stephen R Cole, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Becky L White, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Cathie Fogel, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

David L Rosen, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Michael J Mugavaro, The University of Alabama School of Medicine.

Brian W Pence, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Patrick M Flynn, Texas Christian University.

References

- 1.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Seek, Test, Treat and Retain: Addressing HIV among Vulnerable Populations. Accessed from: http://www.drugabuse.gov/researchers/research-resources/data-harmonization-projects/seek-test-treat-retain/addressing-hiv-among-vulnerable-populations. Accessed December 3, 2016.

- 2.Frieden TR, Das-Douglas M, Kellerman SE, et al. Applying public health Principles to the HIV epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2397–2402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MK, Rutstein SE, Powers KA, et al. The detection and management of early HIV infection: a clinical and public health Emergency. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:S187–S199. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829871e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson DP. HIV treatment as prevention: natural experiments highlight limits of antiretroviral treatment as HIV prevention. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MS, Dye C, Fraser C, et al. HIV treatment as prevention: debate and commentary–will early infection compromise treatment-as-prevention strategies? PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandler RK, Kahana SY, Fletcher B, Jones D, Finger MS, Aklin WM, Hamill K, Webb C. Data Collection and Harmonization in HIV Research: The Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain Initiative at the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Am J Public Health. 2015 Dec;105(12):2416–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen SM, Van Handel MM, Branson BM, et al. Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment–United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1618–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayden EC. ‘Seek, test and treat’ slows HIV. Nature. 2010;463:1006. doi: 10.1038/4631006a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wohl DA, Golin C, Rosen DL, May JM, White BL. Detection of undiagnosed HIV among state prison entrants. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2198–2199. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Screening of Male Inmates During Prison Intake Medical Evaluation --- Washington, 2006--2010. MMWR. 2011 Jun 24;60(24):811–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, et al. Opportunities to diagnose, treat, and prevent HIV in the criminal justice system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S49–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruschak LM, Beavers R. HIV in Prisons, 2001-10. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Sep, 2012. NCJ 238877. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301:848–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Springer SA, Qiu J, Saber-Tehrani AS, Altice FL. Retention on buprenorphine is associated with high levels of maximal viral suppression among HIV-infected opioid dependent released prisoners. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e38335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Springer SA, et al. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1754–60. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephenson BL, et al. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(1):84–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaller ND, Holmes L, Dyl AC, Mitty JA, Beckwith CG, Flanigan TP, Rich JD. Linkage to Treatment and Supportive Services Among HIV-Positive Ex-Offenders in Project Bridge. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19(2):522–531. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wohl DA, Scheyett A, Golin CE, White B, Matuszewski J, Bowling M, Smith P, Duffin F, Rosen D, Kaplan A, Earp J. Intensive case management before and after prison release is no more effective than comprehensive pre-release discharge planning in linking HIV-infected prisoners to care: a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2011 Feb;15(2):356–64. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9843-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golin CE, Knight K, Carda-Auten J, Gould M, Groves J, L White B, Bradley-Bull S, Amola K, Fray N, Rosen DL, Mugavaro MJ, Pence BW, Flynn PM, Wohl D. Individuals motivated to participate in adherence, care and treatment (imPACT): development of a multi-component intervention to help HIV-infected recently incarcerated individuals link and adhere to HIV care. BMC Public Health. 2016 Sep 6;16:935. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3511-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golin CE, Earp JA, Tien H, Stewart P, Howie LA. Randomized trial of motivational interviewing to improve ART adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(1):42–51. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219771.97303.0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mugavero MJ. Improving engagement in HIV care: what can we do? Top HIV Med. 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight K, Simpson DD, Dansereau DF. Knowledge mapping: A psychoeducational tool in drug abuse relapse prevention training. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 1994;20(3/4):187–205. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Best B, Stokols D, Green MW, et al. An integrative framework for community partnering to translate theory into effective health promotion strategy. American Journal of Health promotion. 2003;18:168–176. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1990;10:282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sidibe T, Golin C, Turner K, Fray N, Fogel C, Flynn P, et al. Provider perspectives regarding the health care needs of a key population: HIV-infected prisoners after incarceration. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2015;26(5):556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennis AC, Barrington C, Hino S, Gould M, Wohl D, Golin CE. “You're in a world of chaos:” Experiences accessing HIV care and adhering to medications after incarceration. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015 Sep-Oct;26(5):542–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adamian MS, Golin CE, Shain LS, DeVellis B. Brief motivational interviewing to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: development and qualitative pilot assessment of an intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004 Apr;18(4):229–238. doi: 10.1089/108729104323038900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thrasher AD, Golin CE, Earp JA, Tien H, Porter C, Howie L. Motivational interviewing to support antiretroviral therapy adherence: the role of quality counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Jul;62(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golin CE, Davis RA, Przybyla SM, Fowler B, Parker S, Earp JA, Quinlivan EB, Kalichman SC, Patel SN, Grodensky CA. SafeTalk, a multicomponent, motivational interviewing-based, safer sex counseling program for people living with HIV/AIDS: a qualitative assessment of patients' views. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010 Apr;24(4):237–245. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golin CE, Earp JA, Grodensky CA, Patel SN, Suchindran C, Parikh M, Kalichman S, Patterson K, Swygard H, Quinlivan EB, Amola K, Chariyeva Z, Groves J. Longitudinal effects of SafeTalk, a motivational interviewing-based program to improve safer sex practices among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2012 Jul;16(5):1182–91. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0025-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson DD, Joe GW, Knight K, Rowan-Szal GA, Gray JS. Texas Christian University (TCU) short forms for assessing client needs and functioning in addiction treatment. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2012;51(1-2):34–56. doi: 10.1080/10509674.2012.633024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowan-Szal GA, Joe GW, Bartholomew NG, Pankow J, Simpson DD. Brief trauma and mental health assessments for female offenders in addiction treatment. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2012;51(1-2):57–77. doi: 10.1080/10509674.2012.633019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giordano T, Guzman D, Clark R, Charlebois E, Bangsberg D. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a diverse population using a visual analogue scale. HIV Clin Trials. 2004;5:74–9. doi: 10.1310/JFXH-G3X2-EYM6-D6UG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babor TF, Higgins J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf. Accessed 01 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight K, Simpson DD, Hiller ML. Screening and referral for substance-abuse treatment in the criminal justice system. In: Leukefeld CG, Tims FM, Farabee D, editors. Treatment of drug offenders: Policies and issues. New York: Springer; 2002. pp. 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters RH, Greenbaum PE, Steinberg ML, Carter CR, Ortiz MM, Fry BC, Valle SK. Effectiveness of screening instruments in detecting substance use disorders among prisoners. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000 Jun;18(4):349–58. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rounds-Bryant JL, Baker L., Jr Substance dependence and level of treatment need among recently-incarcerated prisoners. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:557–561. doi: 10.1080/00952990701407462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little RJ, D'Agostino R, Cohen ML, et al. The Prevention and Treatment of Missing Data in Clinical Trials. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(14):1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation After 18+ Years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91(434):473–489. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cole SR, Napravnik S, Mugavero MJ, et al. Copy-years viremia as a measure of cumulative human immunodeficiency virus viral burden. Am J Epidemiol. 2010 Jan 15;171(2):198–205. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spaulding AC, Messina LC, Kim BI, et al. Planning for Success Predicts Virus Suppressed: Results of a Non-Controlled, Observational Study of Factors Associated with Viral Suppression Among HIV-positive Persons Following Jail Release. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):203–211. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, et al. Predictors of Reincarceration and Disease Progression Among Released HIV-Infected Inmates. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24(6):389–394. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haley DF, Golin CE, Farel CE, Wohl DA, Scheyett AM, Garrett JJ, Rosen DL, Parker SD. Multilevel challenges to engagement in HIV care after prison release: a theory-informed qualitative study comparing prisoners' perspectives before and after community reentry. BMC Public Health. 2014 Dec 9;14:1253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, et al. “From the prison door right to the sidewalk, everything went downhill,” a qualitative study of the health experiences of recently released inmates. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zelenev A, Marcus R, Kopelev A, Cruzado-Quinones J, Spaulding A, Desabrais M, Lincoln T, Altice FL. Patterns of homelessness and implications for HIV health after release from jail. AIDS Behav. 2013 Oct;17(Suppl 2):S181–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0472-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Floris-Moore MA. Ending the Epidemic of Heterosexual HIV Transmission Among African Americans. American journal of preventive medicine. 2009;37(5):468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an international association of physicians in AIDS care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eaton EF, Saag MS, Mugavero M. Engagement in human immunodeficiency virus care: linkage, retention, and antiretroviral therapy adherence. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28(3):355–69. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]