Abstract

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a clinical syndrome of language decline caused by neurodegenerative pathology. Although language impairments in PPA are typically localized via the morphometric assessment of atrophy, functional changes may accompany or even precede detectable structural alterations, in which case resting state functional connectivity (RSFC) could provide an alternative approach. The goal of this study was to determine whether language network RSFC is reduced in early stage PPA when atrophy is not prominent. We identified 10 individuals with early stage agrammatic-variant PPA (PPA-G) with no prominent cortical thinning compared to non-aphasic controls. RSFC between two nodes of the language network and two nodes of the default mode network were compared between PPA-G and healthy control participants. Language network connectivity was comparable to controls among patients with milder agrammatism, but was significantly reduced in patients with more pronounced agrammatism. No group differences were observed in default mode network connectivity, demonstrating specificity of findings. In early stages of PPA when cortical atrophy is not prominent, RSFC provides an alternative method for probing the neuroanatomic substrates of language impairment. RSFC may be of particular utility in studies on early interventions for neurodegenerative disease, either to identify anatomic targets for intervention or as an outcome measure of therapeutic efficacy.

Search Terms: Biomarkers, Cognition, Dementia, Dementing Disorders, Functional MRI, Functional Neuroimaging, Physiology & Pharmacology, Volumetric MRI

Introduction

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a syndrome of language decline caused by neurodegenerative disease. Morphometric assessment of cortical atrophy with structural imaging is currently the gold standard for in vivo localization of neurodegeneration in PPA, and the most commonly used method to establish clinico-anatomic correlations.1-3 However, in the early stages of PPA, cortical atrophy may be less prominent and morphometric assessment may therefore be less sensitive at the individual level.3-6

Functional imaging may provide an alternative method for localizing dysfunction in such cases. By correlating spontaneous hemodynamic fluctuations across functional MRI voxels, resting state functional connectivity (RSFC) analysis can be used to probe the functional integrity of the language network.7,8 There are several reports of altered RSFC in PPA. However, those studies did not specifically focus on the early stage of PPA. Additionally, either patients already showed significant levels of cortical atrophy,9,10 or structural morphometry was not specifically reported7,11.

The current study aimed to determine whether RSFC patterns are abnormal in an early stage of PPA when cortical atrophy is not prominent. In order to address this possibility, we set out to first identify a sample of PPA patients without detectable atrophy at a false discovery rate (FDR) of p < .05 on a whole-brain vertex-based cortical thickness analysis. Our goal was to then measure and compare the amplitude of structural (via cortical thickness) and functional (via RSFC) changes in a priori selected epicenters of the language and default mode networks in this early-stage sample. We hypothesized that even patients failing to show significant atrophy on a whole-brain vertex-based cortical thickness analysis would nonetheless show reduced functional connectivity between key nodes of the left perisylvian language network because functional perturbations may be detectable before structural deficits12. In keeping with the selectivity of language deficits in early PPA13,14 and findings from previous RSFC investigations7,11, neither structural nor functional alterations were expected in other neurocognitive networks such as the default mode network. This pattern of results would demonstrate that RSFC can be used to locate functionally disconnected regions before they display obvious morphologic alterations, potentially helping to identify targets for early-stage therapeutic interventions or to evaluate the efficacy of such interventions. Such findings would also demonstrate that RSFC provides unique and complementary information to structural assessments in the early stages of neurodegenerative disease.

Methods

Participants

Participants with PPA were ascertained via their enrollment in a longitudinal investigation at the Northwestern University Cognitive Neurology & Alzheimer's Disease Center. Root diagnosis of PPA was made during a clinical neurological evaluation (conducted by author M.M.M.), according to the established criteria of a relatively selective deterioration of language, initially unaccompanied by impairments in other cognitive domains such as episodic memory or visuospatial processing, in the absence of substantial behavioral or psychiatric disturbances, with an underlying neurodegenerative origin.13-15 Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) Battery16 was used as a global measure of language function. Patients were classified into agrammatic (PPA-G), logopenic (PPA-L), and semantic (PPA-S) subtypes according to a well-established quantitative template approach, based on the relative salience of grammatical, word-finding/repetition, and single-word comprehension impairments, respectively.3,15,17

Fifty-six consecutive cases met root diagnostic criteria for PPA and had both structural and resting state functional MRI scans available. All patients were right-handed, consistent with left-hemispheric dominance for language. A more restricted sample of PPA patients was selected from this pool for inclusion in the current study based on the criteria of #1) having no prominent (i.e. statistically significant according to an FDR threshold of P < .05) cortical atrophy at the individual subject level as measured by whole-brain vertex based analysis, and #2) all displaying the same phenotypic subtype of PPA. The former allowed us to examine RSFC in early stages of PPA when cortical atrophy is not yet prominent, and the latter to correlate RSFC changes with discrete domains of language impairment. The result of the above selection process and characteristics of the final sample of patients enrolled in the study are described under the “Results” section.

Reference values for neuroimaging analyses were provided by two groups of right-handed non-aphasic control participants of similar demographic properties to the PPA patients. Each control group was recruited as part of the same longitudinal investigation of PPA, and have been thoroughly characterized in previous publications. RSFC reference values were provided by a group of n=33 controls18 (Table 1), and cortical thickness values were provided by a group of n=35 controls.19

Table 1.

Demographics and measures of language performance.

| Measure (max score) | Control (n = 33) | PPA-G (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.5 ± 7.1 | 67.7 ± 7.6 |

| Education | 15.7 ± 2.3 | 14.8 ± 1.8 |

| Gender | 15M, 18F | 4M, 6F |

| Aphasia Quotient (100) | 98.9 ± 1.9 | 89.0 ± 5.1 * |

| Grammar Composite (30) | 29.7 ± 0.7 | 19.2 ± 5.6 * |

Aphasia Quotient: an overall measure of aphasia severity across language domains. Grammar Composite: a measure of non-canonical sentence production.

significantly lower in the PPA-G than the control group (P < .05).

MRI acquisition

Structural and functional magnetic resonance images (MRI) were acquired using a Siemens Trio 3 tesla scanner. Structural MR images were acquired via a T1-weighted 3D MPRAGE sequence (repetition time, 2300ms; echo time, 2.91ms; flip angle, 9°; field of view, 256mm, 1×1×1 mm voxel size) at a thickness of 1.0mm. Resting state functional MRI scans were acquired using a T2-weighted echoplanar sequence (repetition time, 2500ms; echo time, 20ms; flip angle, 80°; field of view-220, 3×3×3 mm voxel size) recording 40 slices at a thickness of 3.0mm. Participants were instructed to stay awake with eyes open during the 10-minute resting state scan.

Cortical thickness mapping and atrophy screening

Cortical thickness of structural MRIs was assessed with the FreeSurfer image analysis suite.20 After registering the cortical surface into a native vertex-based space, registration errors were manually corrected and the surface was reconstructed in an iterative fashion until all errors were resolved.20 Cortical thickness was then calculated as the distance between the gray matter/white matter boundary and the pial surface, resulting in thickness estimates at each vertex. Data were smoothed on the surface using a Gaussian smoothing kernel with a full-width half-maximum (FWHM) of 20 mm. Individual cortical thickness maps from each of the 56 consecutive candidate patients were separately contrasted (via general linear model) against the control reference group (n = 35), in order to select a final sample of patients without significant thinning anywhere in the neocortex according to an FDR threshold of p < .05.

Selection of ROIs

Group analyses were implemented to compare structural with functional changes in early-stage PPA, carried out in a priori selected regions of interest (ROIs). ROI analysis allowed for RSFC and cortical thickness to be assessed separately in the language network and in a non-verbal network for comparison, in order to demonstrate specificity of findings. The default mode network was chosen for this purpose.11,21,22

Language ROIs were centered on two areas that have been consistently reported to have asymmetric left lateralized intrahemispheric connectivity: the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and middle temporal gyrus (MTG).8,18,23 The IFG is most frequently subject to atrophy in PPA-G,1-3 and is consistently implicated in grammatical competency.24,25 An IFG ROI was chosen for the current study, centered at pars triangularis in the left hemisphere, which lays at the heart of Broca's area.26 The second language ROI was centered on the posterior aspect of left MTG. This area shares a strong functional connection with IFG, plays a critical role in lexicosemantic processing, and is frequently subject to atrophy in both PPA-L and PPA-S.8,17,18,27 Two midline ROIs from the default mode network were selected: the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and medial prefrontal cortex (PFC), which share one of the strongest functional connections within the default mode network.21,22 The PCC ROI was centered on the cingulate isthmus, and the PFC ROI was centered on the inferior aspect of mesial superior frontal gyrus21,22.

Procedures for ROI placement differed for cortical thickness versus RSFC analyses, as the former took place in a 2-dimensional vertex-based space while the latter took place in a 3-dimensional voxel-based space. As such details of ROI construction and placement are provided in the relevant following sections.

Cortical thickness in language and default mode ROIs

During the final Freesurfer reconstruction each participant's native space surface map was automatically parcellated according to the Desikan-Killiany atlas.28 The IFG ROI was comprised of the pars triangular is label in the Desikan-Killiany atlas. Each of the remaining structural ROIs were composed of subsections of Desikan-Killiany labels, in order to maximize correspondence between surface-based structural ROIs and voxel-based RSFC ROIs. The MTG ROI was composed of a posterior section of the Desikan-Killiany MTG label. A midsection of the isthmus cingulate and an inferior section of the precuneus atlas regions were combined to create the PCC ROI. Likewise, the PFC ROI was comprised of a superior section of the orbitofrontal region, inferior section of the superior frontal region, and a midsection of the rostral anterior cingulate region. The locations of structural ROIs are shown in Figure 1A. Average cortical thickness in each ROI was contrasted between the PPA sample and the non-aphasic reference group of 35 controls.

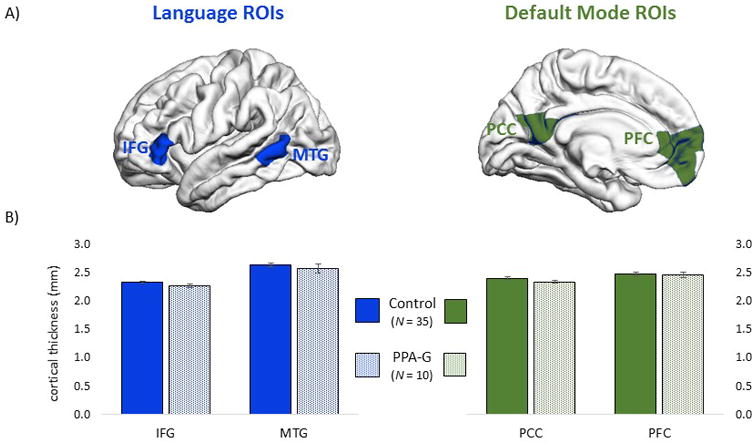

Figure 1. Cortical thickness.

(A) Surface vertex-based ROIs used to evaluate cortical thickness in structural MRI scans. Thickness was evaluated in two language ROIs (IFG and MTG) and two ROIs in the default mode network (PCC and PFC). (B) Average cortical thickness values (with standard error bars) did not differ between groups, in either the language or default mode networks (P > .05).

RSFC in language and default mode ROIs

Functional images were analyzed with SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Functional images were corrected for slice timing, realigned, and warped into standard space using transformation parameters from coregistered structural images, which had been warped to the ICBM152 template using the SPM fast diffeomorphic algorithm. The functional images were then smoothed using a 6-mm Gaussian kernel, detrended, and bandpass filtered from 0.01 to 0.08 Hz. Volumes with greater than 1mm scan-to-scan movement (Control mean ± standard deviation = 2.2±3.1, PPA= 1.1±1.4 out of 244 total volumes) were interpolated with the surrounding volumes. The six affine motion parameters, global signal, white matter signal, and cerebrospinal fluid signal were then regressed out of each time series.

The preprocessed time series were then extracted from 10 mm spherical ROIs for RSFC analysis. Specific coordinates (in MNI space) were chosen from previous investigations of non-aphasic adults (IFG x/y/z= -54/24/3, MTG = -66/-38/-4, PCC= 0/-53/26, PFC = 0/52/-6).18,21,22. Time series correlations were examined between the two language ROIs (IFG-MTG), and between the two default mode ROIs (PCC-PFC). Resultant r values were converted into z values using Fisher's transformation. Z values were then compared between the PPA group and the control reference group (n = 33) via two-tailed independent samples t-tests.

Results

Atrophy screening and sample selection

Twelve of the 56 candidate PPA patients failed to show prominent (i.e. statistically significant) cortical thinning in any area of the neocortex, when their single-subject cortical thickness maps were separately contrasted against the control reference group at an FDR threshold of p < .05. The final study sample was comprised of 10 patients (out of the 12 without prominent atrophy) who were all of the PPA-G subtype. The key diagnostic feature, agrammatism, was quantified with a composite measure of non-canonical sentence production based on selected items from the Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences29 and the Northwestern Anagram Test30 (Table 1). In the interest of detecting specific brain-language relationships in a homogenous clinical phenotype (PPA-G), the remaining two patients without prominent atrophy (both PPA-L subtype) were excluded from analysis. Overall level of aphasia severity was quantified via Aphasia Quotient scores from the Western Aphasia Battery.16 The selected PPA-G sample showed an average Aphasia Quotient of 89.0±5.1, consistent with an early stage of disease when language symptoms are relatively mild.

Demographic and linguistic characteristics of the control and PPA-G groups were compared using independent samples t-tests (Table 1). The control and PPA-G groups did not differ in terms of age or education (p > .05 for each comparison). Lower aphasia quotients from the Western Aphasia Battery confirmed the presence of language impairment in the PPA-G group (p < .001). Consistent with the agrammatic subtype diagnosis, composite grammar scores were lower in the PPA-G group (p <.001).

Cortical thickness in language and default mode ROIs

Cortical thickness was evaluated in the language and default mode ROIs shown in Figure 1A. On average the cortices of the PPA-G group were 2.4% thinner in the IFG ROI, 2.6% thinner in MTG, 2.8% thinner in PCC, and 0.6% thinner in PFC, compared to the control group (Figure 1B). These subtle group differences were not significant, according to independent samples t-tests (P > .05 for each comparison).

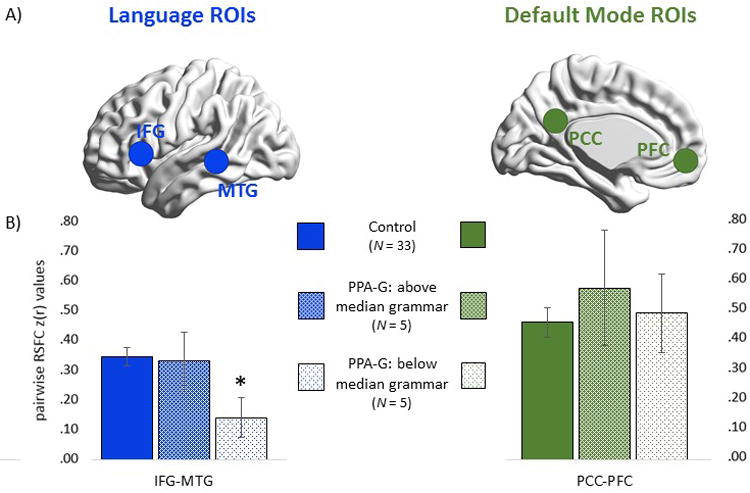

RSFC in the entire PPA-G sample

RSFC was examined in voxel-based spherical ROIs, shown in Figure 2A. RSFC between default mode network ROIs was not decreased in the PPA-G group (z(r) = 0.53) compared to controls (z(r) = 0.46) (P > .05). RSFC between the language ROIs was lower in the PPA-G group (z(r) = 0.24) compared to the control group (z(r) = 0.35), a 31% drop in correlational strength between groups that nonetheless failed to reach significance (P = .14). This suggests that reductions in language connectivity may not be homogenous in the PPA-G group, but rather that RSFC may be reduced in some patients but not others.

Figure 2. Functional connectivity.

(A) Voxel-based ROIs used to query RSFC in functional MRI scans. (B) Strength of pairwise RSFC coherence between language (IFG-MTG) and default mode (PCC-PFC) ROIs. PPA-G patients were subgrouped into those with above-median and below-median composite grammar scores. *: Significantly lower than controls (P < .05).

RSFC in patients with above versus below median grammar scores

In order to explore this possibility, a median split on grammar composite scores was performed on the PPA-G group. Independent samples t-tests showed that patients performing above (n = 5) and below (n = 5) the median did not differ in terms of age, education, or aphasia quotients (P > .05 for each comparison, for full details see the eTable in the supplement). The two subgroups did not differ in cortical thickness (eTable) in either of the two language or in either of the two default mode ROIs, and neither subgroup differed in cortical thickness compared to controls (P > .05 for each comparison).

As shown in Figure 2B, language connectivity Z(r) values (IFG-MTG) in the above-median subgroup (z(r) = 0.33) were close to control values (z(r) = 0.35) (P > .05), but were lower in the below-median subgroup (z(r) = 0.14) (P < .05). Thus, whereas Z(r) values were only reduced by 6% in the above-median subgroup they were reduced by 60% in the below-median subgroup (relative to controls). In contrast, default mode network connectivity was not reduced in the above-median (z(r) = 0.57) or below-median (z(r) = 0.49) subgroups relative to controls (z(r) = 0.46) (P > .05 for each comparison).

Discussion

RSFC was examined in 10 PPA-G patients at an early stage of disease when atrophy was not yet prominent; any subtle morphometric changes that may have been present in this sample were non-significant when using the sensitive morphometric technique of cortical thickness analysis. Within this set of patients, functional connectivity between language network regions (IFG and MTG) was reduced but only among patients with more pronounced agrammatism. In contrast the patients showed spared connectivity between default mode network regions (PCC and PFC), demonstrating specificity of findings.

Although the current results were based on limited sample sizes, they provide proof of concept that, at least in some cases of PPA-G, changes in language functioning and RSFC may be detectable before changes in morphology at early stages of the disease. Among patients with more pronounced agrammatism (below-median grammar scores), cortical thickness was reduced by 4.3% in the IFG region (not statistically significant), and was not detectably reduced in the MTG region, relative to controls. In contrast, connectivity values between IFG and MTG were reduced by 60% in that group. A sequence where physiological perturbations precede neural death is tenable, as the pathological burden of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer disease (the two major pathologies underlying PPA) lead to dysfunctional metabolism and synaptology in neurons prior to their destruction.31

The current results add to a growing literature documenting prominence of physiological abnormalities in the early stages of neurodegenerative disease. Regional brain physiology is most commonly assessed with positron emission tomography (PET), evaluating basal levels of metabolism via radioisotope uptake. Studies of early-stage PPA without prominent atrophy have shown hypometabolism in the language network according to PET5 and single-photon tomography.4 Among individuals with PPA who have already manifested regional atrophy, hypometabolism is often more extensive, affecting additional areas that are not yet manifestly atrophic.4,32,33 Although RSFC, like PET, is an index of physiological integrity, it reveals dynamic aspects of network functionality that are qualitatively distinct from basal metabolism. The relationship between these measures is not always direct; for example in Alzheimer disease hippocampal connectivity has been found to be inversely related to hippocampal metabolism.34 In addition to the current results in PPA-G, RSFC abnormalities have been found in other clinical populations prior to the development of significant atrophy. Cognitively normal older adults with amyloid-positive imaging markers have shown RSFC changes in the default mode network compared to amyloid-negative individuals, with no morphometric evidence of atrophy.22 Likewise, carriers of the Huntington mutation (CAG repeat expansions) show RSFC changes in dorsal brain networks prior to observable atrophy.35

These results demonstrate that RSFC provides unique information about the early anatomy and pathophysiology of language impairment, and can be used in conjunction with structural MRI for a more complete clinico-anatomic assessment. There are implications for brain-language mapping studies, in which the standard approach is to assign loss of function (e.g. language impairments) to areas of peak atrophy. Although atrophy undoubtedly contributes to language impairment, the current results suggest that in early disease stages connectivity changes may be of greater magnitude than morphological changes. Therefore, it may be valuable to examine RSFC in addition to atrophy patterns in studies of PPA.

There has been growing interest in applying therapeutic interventions during the preclinical or early clinical stages of neurodegenerative disease, before large-scale destruction of brain tissue.36 An emphasis on early intervention means that patients in these studies will be less likely to show atrophy in MRI, so RSFC may be of particular utility in early therapeutic designs. RSFC can be measured in discrete brain regions, and thus could potentially be used to identify anatomic targets for intervention (using techniques such as trans or intracranial stimulation) or as an outcome measure of therapeutic efficacy.

Limitations: RSFC abnormalities were only evident in patients with more advanced agrammatism. It is possible that our failure to detect such abnormalities in patients with more mild agrammatism is based on the low sample sizes included in the current study. Future studies with larger patient samples would help to address this possibility. It is also entirely possible that language disturbances in the above-median subgroup are based on dysfunctional synaptology occurring at temporal and/or spatial scales not captured by the RSFC method. Neural ensembles communicate electrochemically across a range of high frequencies beyond the relatively slow temporal resolution of fMRI.37,38 The spatial resolution of fMRI is similarly constrained; the hemodynamic signal from a typical fMRI voxel corresponds with a population of approximately 5.5 million neurons.39 Given these limitations, the RSFC method may fail to detect the subtle changes in synaptology underlying language impairments in the very earliest (or initial) stages of PPA. Diffusion tensor imaging may help reveal whether white matter pathways are affected to a greater degree than cortical thickness in such patients.

This study focused on language, RSFC, and morphology in the agrammatic subtype of PPA. Future studies may help to determine whether the sequence and timing of these disease markers of PPA are modulated by the nature of the underlying pathology (frontotemporal lobar degeneration due to tauopathy or TDP-43 proteinopathy, versus Alzheimer-type pathology13) or by language phenotype (agrammatic, logopenic, or semantic subtypes).

The current results show that RSFC provides additional information when cortical thinning is minimal, so clinicians may be tempted to use RSFC to characterize individual patients in clinical settings. Unlike PET, however, it remains to be demonstrated whether RSFC patterns are interpretable and clinically meaningful at the individual subject level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by CNADC Rosenstone fellowship fund, Northwestern University CNADC pilot grant (P30 AG13854), K23 DC014303-01A1 (Bonakdarpour), NIDCD DC008552 (Mesulam) and NIDCD DC013386 (Hurley). We thank Dr. Alfred Rademaker, Dr. Xue Wang, Dr. Todd Parrish, and Daniel Ohm for their helpful recommendations.

Study Funding: Supported by the Northwestern University Alzheimer Disease Center Rosenstone fellowship fund, pilot grant P30 AG13854, and NIH NIDCD K23 DC014303-01A1 (Bonakdarpour); NIH NIDCD DC008552 and NIDCD DC013386 grants (Hurley)

Glossary

- IFG

inferior frontal gyrus

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MTG

middle temporal gyrus

- PCC

posterior cingulate cortex

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PPA

primary progressive aphasia

- PPA-G

nonfluent/agrammatic variant of PPA

- ROI

region of interest

- RSFC

resting state functional connectivity

Footnotes

Author Contributions: B.B., M.M.M., and R.S.H. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. B.B., E.J.R., A.W., J.S. and R.S.H. analyzed data.

Dr. Bonakdarpour is funded by NIH K23 DC014303-01A1, and Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer Disease Center pilot grant (P30 AG13854).

Dr. Rogalski, is funded by NIH grants R01AG045571, R03 DC013386, R01NS075075, and receives research support from the Alzheimer's Association and the Davee Foundation.

Mr. Wang reports no disclosures.

Miss Sridhar reports no disclosures.

Dr. Mesulam is on the medical advisory council for the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, is funded by NIH grants P30 AG13854 and R01 DC008552 and R01 AG045571, U01 AG016976 and received research support from the Alzheimer's Association and the Davee Foundation

Dr. Hurley is funded by NIH grants NIDCD DC013386 and NIDCD DC008552, and received research support from the Davee Foundation.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):335–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, et al. Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2011;76(21):1804–1810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesulam MM, Wieneke C, Thompson C, et al. Quantitative classification of primary progressive aphasia at early and mild impairment stages. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 5):1537–1553. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinnatamby R, Antoun NA, Freer CEL, et al. Neuroradiological findings in primary progressive aphasia: CT, MRI and cerebral perfusion SPECT. Neuroradiology. 1996;38(3):232–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00596535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kempler D, Metter EJ, Riege WH, et al. Slowly progressive aphasia: three cases with language, memory, CT and PET data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:987–993. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.11.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesulam MM. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(6):592–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitwell JL, Jones DT, Duffy JR, et al. Working memory and language network dysfunctions in logopenic aphasia: a task-free fMRI comparison with Alzheimer's dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(3):1245–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turken AU, Dronkers NF. The neural architecture of the language comprehension network: converging evidence from lesion and connectivity analyses. Frontiers in systems neuroscience. 2011;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agosta F, Galantucci S, Valsasina P, et al. Disrupted brain connectome in semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(11):2646–2655. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandelli ML, Vilaplana E, Brown JA, et al. Healthy brain connectivity predicts atrophy progression in non-fluent variant of primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 10):2778–2791. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann M, Madison C, Ghosh PM, et al. Loss of functional connectivity is greater outside the default mode network in nonfamilial early-onset Alzheimer's disease variants. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(10):2678–2686. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinnatamby R, Antoun NA, Freer CE, Miles KA, Hodges JR. Neuroradiological findings in primary progressive aphasia: CT MRI and cerebral perfusion SPECT. Neuroradiology. 1996;38(3):232–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00596535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mesulam MM, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, et al. Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(10):554–569. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mesulam MM, Weintraub S. Primary progressive aphasia and kindred disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;89:573–587. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)01254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kertesz A. The Western Aphasia Battery. New York; London: Grune & Stratton; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mesulam MM, Wieneke C, Rogalski E, et al. Quantitative template for subtyping primary progressive aphasia. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(12):1545–1551. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurley RS, Bonakdarpour B, Wang X, et al. Asymmetric connectivity between the anterior temporal lobe and the language network. J Cogn Neurosci. 2015;27(3):464–473. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogalski E, Cobia D, Martersteck A, et al. Asymmetry of cortical decline in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2014;83(13):1184–1191. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segonne F, Pacheco J, Fischl B. Geometrically accurate topology-correction of cortical surfaces using nonseparating loops. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26(4):518–529. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.887364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Dijk KR, Hedden T, Venkataraman A, et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: theory, properties, and optimization. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103(1):297–321. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedden T, Van Dijk KR, Becker JA, et al. Disruption of functional connectivity in clinically normal older adults harboring amyloid burden. J Neurosci. 2009;29(40):12686–12694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3189-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H, Stufflebeam SM, Sepulcre J, Hedden T, Buckner RL. Evidence from intrinsic activity that asymmetry of the human brain is controlled by multiple factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(48):20499–20503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908073106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyler LK, Marslen-Wilson WD, Randall B, et al. Left inferior frontal cortex and syntax: function, structure and behaviour in patients with left hemisphere damage. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 2):415–431. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schonberger E, Heim S, Meffert E, et al. The neural correlates of agrammatism: Evidence from aphasic and healthy speakers performing an overt picture description task. Front Psychol. 2014;5:246. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broca P. Sur le Siège de la faculté du langage articulé dans l'hémisphère gauche du cerveau. Paris: V. Masson; 1865. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM. Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2011;76(21):1804–1810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson CK. Northwestern assessment of verbs and sentences. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University; 2011. Retrieved from http://northwestern.flintbox.com/public/project/9299/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, Wieneke C, et al. The northwestern anagram test: measuring sentence production in primary progressive aphasia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24(5):408–416. doi: 10.1177/1533317509343104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saxena S, Caroni P. Selective neuronal vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases: from stressor thresholds to degeneration. Neuron. 2011;71(1):35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iaccarino L, Crespi C, Della Rosa PA, et al. The semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia: clinical and neuroimaging evidence in single subjects. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madhavan A, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, et al. FDG PET and MRI in logopenic primary progressive aphasia versus dementia of the Alzheimer's type. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tahmasian M, Pasquini L, Scherr M, et al. The lower hippocampus global connectivity, the higher its local metabolism in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;84(19):1956–1963. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrington DL, Rubinov M, Durgerian S, et al. Network topology and functional connectivity distrubances precede the onset of Huntington's disease. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 8):2332–2346. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selkoe DJ. The therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease: where we stand and where we are heading. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):328–336. doi: 10.1002/ana.24001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buzsaki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science. 2004;304(5679):1926–1929. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ko AL, Weaver KE, Hakimian S, et al. Identifying functional networks using endogenous connectivity in gamma band electrocorticography. Brain Connect. 2013;3(5):491–502. doi: 10.1089/brain.2013.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Logothesis NK. What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature. 2008;453(7197):869–878. doi: 10.1038/nature06976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.