Abstract

Migratory birds can be adversely affected by climate change as they encounter its geographically uneven impacts in various stages of their life cycle. While a wealth of research is devoted to the impacts of climate change on distribution range and phenology of migratory birds, the indirect effects of climate change on optimal migratory routes and flyways, through changes in air movements, are poorly understood. Here, we predict the influence of climate change on the migratory route of a long-distant migrant using an ensemble of correlative modelling approaches, and present and future atmospheric data obtained from a regional climate model. We show that changes in wind conditions by mid-century will result in a slight shift and reduction in the suitable areas for migration of the study species, the Oriental honey-buzzard, over a critical section of its autumn journey, followed by a complete loss of this section of the traditional route by late century. Our results highlight the need for investigating the consequences of climate change-induced disturbance in wind support for long-distance migratory birds, particularly species that depend on the wind to cross ecological barriers, and those that will be exposed to longer journeys due to future range shifts.

Keywords: regional climate model, niche modelling, ensemble forecasting, flyway, optimal route, crested honey-buzzard

1. Introduction

Global climate change is projected to have severe impacts on migratory species, as they might face alterations in their breeding, wintering and stopover areas, as well as en route [1]. Migratory birds are already responding to climate warming through geographical range shifts [2], as well as changes in phenology [3,4], migratory strategies [5], fitness [6] and demography [7]. Unsurprisingly, temperature and precipitation are the most commonly used variables in research on the impacts of climate change on migratory birds, as they determine the general suitability of habitats and breeding success. Variables related to air movement have also been considered in a handful of studies, but mostly due to their correlation with the timing of spring arrival of migratory birds [8–11]. Atmospheric currents, especially wind, play a significant role in shaping migratory routes and facilitating long-distance flight [12–14], particularly for species whose morphology and flight characteristics result in higher dependence on air movements for route selection, such as soaring raptors [15,16]. Thus, alterations in the pattern and strength of wind and other forms of air movement as a consequence of climate change can subsequently influence the efficiency and spatial distribution of optimal migratory routes of birds. Attempts at predicting such influences remain very limited in the scientific literature, however.

Predicting the response of natural phenomena to climate change is possible through general circulation models (GCMs), which estimate the future values of climate variables by taking into account physical atmospheric and oceanic processes. Correlative niche models are commonly used to address the spatial changes in distribution range of migratory birds in the face of climate change as defined by GCMs [17]. Although the migratory niche of a bird, defined as the environmental conditions that birds prefer en route, can be modelled using correlative approaches [18], to our knowledge no studies have used such methods to make predictions about optimal migratory routes under climate change scenarios.

In this study, by using an ensemble of correlative modelling approaches and atmospheric data for the present and future, we investigated the potential changes in the optimal migratory route of the Oriental honey-buzzard Pernis ptilorhynchus, an East Asian soaring raptor, over a critical section of its autumn migration.

2. Material and methods

We used two regression-based (GLM, generalized linear model; GAM, generalized additive model) and two machine-learning-based algorithms (GBM, generalized boosted model; MaxEnt, maximum entropy) to build an ensemble model of the migratory niche of Oriental honey-buzzards over the East China Sea region (116°–133° E and 26°–42° N) in autumn. We focused on this relatively small section of the autumn journey as it is characterized by an approximately 680 km non-stop flight over the East China Sea between southwestern Japan and China, and is very likely to be shaped solely by atmospheric conditions [18,19]. Such independence of biotic interactions (e.g. prey availability and competition) and dispersal restraints can increase the reliability of a niche model and its transferability across time and space [20].

We modelled the contemporary relationship between honey-buzzard migration routes and wind conditions based on en route locations derived from satellite-tracking of 31 adult birds (2006–2013). Training points were taken from Nourani et al. [18] and background points were selected as described therein. Explanatory variables included eastward (wind-u) and northward (wind-v) components of the wind and planetary boundary layer height (BLH) as a proxy of convective conditions, with higher BLH corresponding to stronger convective conditions [21,22]. We used 80% of the satellite telemetry locations for model development and 20% for testing the models. Models were evaluated using a 10-fold cross-validation procedure and true skills statistic (TSS), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) metrics were calculated for classification accuracy. We used models with AUC > 0.8 and TSS > 0.7 to generate an ensemble model following a weighted (proportional) average approach [23]. We then projected the niche model to the values of explanatory variables averaged for the present (2006–2013), the middle (2046–2055) and the end (2091–2100) of this century. Projections to future conditions were done separately for two scenarios of climate change. All analyses were done using biomod2 package [24] in R environment v. 3.3.1 [25].

All projections of atmospheric variables for the period of autumn migration (from 11 September to 20 October [19]), and averaged for the present (2006–2013) and two periods in the future (mid-century: 2046–2055; late century: 2091–2100), were obtained from HadGEM3-RA Regional Climate Model (RCM) developed by National Institute of Meteorological Research in South Korea through the CORDEX-East Asia database (https://cordex-ea.climate.go.kr/). This RCM provides projections under two climate change scenarios, Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) 4.5 and 8.5, which we used in this study. RCPs are greenhouse gas concentration trajectories as adopted in the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [26]. The RCP4.5 scenario assumes a peak in greenhouse gas emissions around 2040, followed by a decline, while the RCP8.5 scenario (i.e. the business-as-usual scenario) assumes that emissions continue to rise throughout the twenty-first century [27]. Wind variables were downloaded at the 850 MB pressure level with a 6 h temporal resolution. This pressure level corresponds with the average flight height of the birds [19]. Furthermore, it was the lowest-pressure-level data available from the above-mentioned RCM. Only daytime data were used for model building as birds complete this section of migration during the day. BLH was downloaded at daily intervals (at 12.00 UTC). All variables were interpolated to 0.02° cell size before averaging.

Model projections for conditions exceeding the limits experienced during model building are not reliable [17,28]. Biomod2 identifies areas in the future data where values are outside the range of those of the current conditions and presents them as a clamping mask. These areas should be interpreted with caution or removed from the final model.

3. Results

The modelling algorithms used for building an ensemble model of the migratory niche of Oriental honey-buzzards over the East China Sea region in autumn had high discrimination capacity and accuracy (table 1). The final ensemble model was successfully cross-validated (table 1) and correctly predicted most observations (sensitivity = 97.7%; specificity = 89.5%). Eastward and northward winds had very similar average importance in the ensemble model. Boundary layer height had the smallest effect in model building (table 1; for response curves see electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

Table 1.

Average performance (AUC and TSS) and variable importance (and standard deviation, s.d.) calculated for individual algorithms and the ensemble model.

| algorithm | model performance |

variable importance (s.d.) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | TSS | Wind_v | Wind_u | BLH | |

| GLM | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.64 (0.035) | 0.66 (0.045) | 0.04 (0.041) |

| GBM | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.55 (0.025) | 0.54 (0.056) | 0.35 (0.082) |

| GAM | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.61 (0.044) | 0.62 (0.028) | 0.35 (0.073) |

| MaxEnt | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.44 (0.039) | 0.68 (0.026) | 0.09 (0.051) |

| ensemble | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.54 (0.017) | 0.58 (0.015) | 0.1 (0.003) |

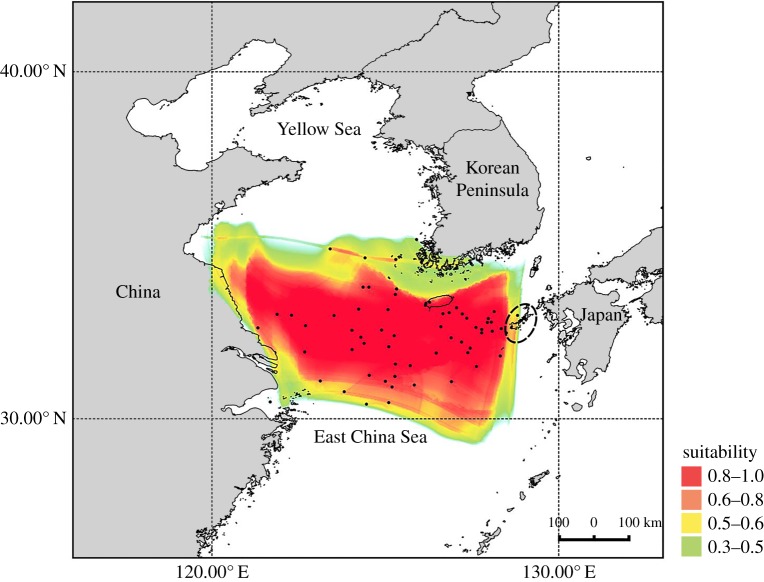

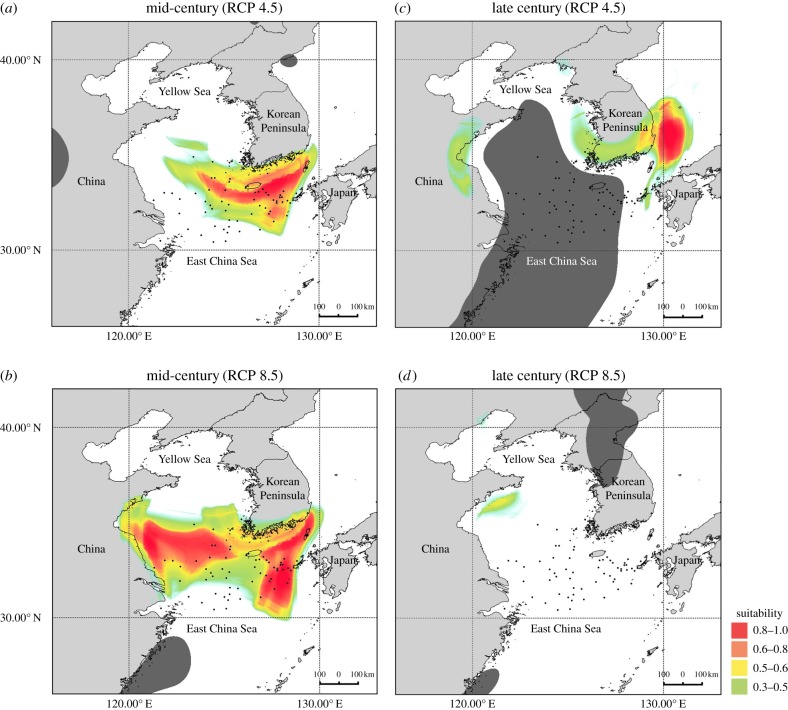

Visualizations of projecting the niche model to the current and future conditions showed dramatic changes in the suitability of an autumn migration route over the region under both scenarios. Based on the contemporary atmospheric conditions, suitable locations for migration between Japan and China occur over the East China Sea (figure 1). The mid-twenty-first century will see a slight northward shift in suitable areas, with a considerable reduction in the area and connectivity of the highly suitable areas (figure 2a,b), with more severe conditions under the RCP4.5 scenario. At the end of the century, however, our model identified suitable areas to the east of the Korean Peninsula under RCP4.5 (figure 1c) and a small patch of moderate suitability under RCP8.5 (figure 1d), all of which lie outside the traditional route and cannot provide a complete route from Japan to China.

Figure 1.

Ensemble model projection for the regions of suitable atmospheric conditions during the autumn migration of Oriental honey-buzzards in the present (2006–2013). Black dots represent en route locations of Oriental honey-buzzards marked with satellite transmitters (2006–2013) used for model-building. The dashed ellipse indicates the location of the Goto Islands, where the birds depart at the start of their autumn migration. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 2.

Ensemble model projections for the regions of suitable atmospheric conditions during the autumn migration of Oriental honey-buzzards for (a) mid-century (2046–2055) under RCP4.5 scenario, (b) mid-century (2046–2055) under RCP8.5 scenario, (c) late century (2091–2100) under RCP4.5 scenario, and (d) late century (2091–2100) under RCP8.5 scenario. Black dots represent en route locations of Oriental honey-buzzards marked with satellite transmitters (2006–2013) used for model-building. Dark grey patches show areas identified by clamping masks as having values outside the range used for training the model. (Online version in colour.)

Areas identified as having values outside the range used for training the model, as shown by the clamping masks (figure 2), were predicted as unsuitable by the model. See electronic supplementary material, figure S2 for a comparison of monthly averages of wind speed over the East China Sea region, calculated for the traditional route in the three time periods.

4. Discussion

We have shown that predicted alterations in atmospheric conditions caused by climate change have the potential to adversely affect the suitability of traditional avian migratory routes. The ecological consequences of such changes for Oriental honey-buzzards can be severe as we approach the end of the century, particularly because our projections did not reveal alternative routes at the modelled altitude and dates for the birds to migrate from Japan to China.

(a). Mid-century conditions

As Oriental honey-buzzards start their migration from the Goto Islands of Japan (figure 1) towards China, they depend highly on thermals and tailwinds to complete the sea crossing [18,19]. Wind conditions over the Goto Islands are expected to remain somewhat suitable by mid-century under both climatic scenarios. The overlap between the current and the mid-century suitable locations for migration over the East China Sea region makes it likely for the birds to gradually shift their route to fly over the more suitable areas. Such behavioural adjustments, by learning from individual experience or by observing others, can happen relatively quickly [29,30]. It has been previously shown that birds, including soaring raptors, have high phenotypic plasticity of migratory routes [31,32]. However, it remains unclear whether Oriental honey-buzzards have the necessary adaptive potential relative to the speed of climate change. Satellite tracking of one juvenile bird indicates that in this population of Oriental honey-buzzards, juveniles migrate separately from adults [33], suggesting strong endogenous control on the choice of migratory route and limited possibility for cultural transmission of new suitable routes. It is therefore highly probable that many individuals following their innate migratory route would attempt to cross the sea at areas that are no longer suitable and would perish at sea, as they are unable to perform flapping flight over such a long distance in the absence of tailwinds. Thus, the population of the Oriental honey-buzzard breeding in Japan is very likely to face new environmental conditions that will require an adaptive response, which may imply processes of severe natural selection, if routes are kept as at present.

The connectivity of suitable areas in mid-century compared with the current conditions will be reduced under both scenarios. Conditions under the RCP4.5 scenario are particularly concerning because the areas identified as suitable do not extend all the way to China. Such reductions and large gaps between suitable migration areas indicate higher energetic costs of crossing the sea, due to the need for the birds to switch to flapping flight where conditions are not suitable, and potentially an increase in the duration of migration over the region. The resulting poor migratory performance can lead to delayed arrival in Southeast Asian wintering grounds, where the birds face high competition with other raptors [34]. Moreover, the associated carry-over effects can further affect the individuals negatively.

Our results showed more severe conditions under the optimistic RCP4.5 scenario than the most pessimistic scenario, RCP8.5. It is important to note that the relationship between wind and increased greenhouse gas concentration is complex, and in our study area it depends on the global circulation patterns under each scenario, particularly over the Pacific Ocean. As changes in wind conditions from RCP4.5 to RCP8.5 are not unidirectional (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), we did not observe a clear reduction in suitability when moving from RCP4.5 to RCP8.5. Moreover, the strong variability of wind can be responsible for our results. By averaging data over longer periods of time than we used in this study, it might be possible to remove the strong variability in wind patterns (I. Takayabu 2017, personal communication). We urge future studies to consider this when deciding on the appropriate time periods for studying wind conditions.

(b). Late-century conditions

By the end of this century, the region is likely to lose its suitability for autumn migration of Oriental honey-buzzards altogether. Under RCP8.5, this is likely to be due to the weaker winds (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Under RCP4.5, however, winds will be stronger (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), even more so than the maximum wind speed in the present conditions, hence the clamping mask over the region (figure 2c). Our projections show that such high wind speeds will not be suitable for the birds to migrate over the East China Sea.

The loss of suitability of the traditional route shown by our results can severely affect this population of Oriental honey-buzzards. However, migratory birds are able to assess atmospheric conditions, particularly wind, to decide the best time for departure [35]. It can therefore be expected that Oriental honey-buzzards will delay their departure due to unsuitability of atmospheric conditions. It has been suggested that autumn conditions will start later due to climate change, indicating the possibility that suitable wind conditions over the region can occur later in the year, leading to a temporal adjustment of Oriental honey-buzzards over the region. The overall changes in wind patterns over the traditional route do not clearly suggest a delay of autumn conditions, however (see electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Moreover, although such temporal adjustments can save the population from extinction, the birds will bear the costs of delayed arrival in wintering grounds. Another possibility for the population to survive would be to adjust their migratory strategy, by either becoming sedentary (see [30,36]) or switching to an overland route through the Korean peninsula and China while fuelling their migration by adopting a stop-and-forage strategy. Again, it remains unclear whether the population will be able to adapt to such changes through phenotypic adjustments or evolutionary responses over such a short period of time.

5. Concluding remarks

This study is one of the first attempts at investigating the greatly overlooked, but potentially severe, indirect effects of climate change on migratory routes of birds through alteration of atmospheric conditions. Our results are not to be considered as the definite future for the Oriental honey-buzzards in the region, however, as our analyses were restricted to a single RCM and a single pressure level (i.e. altitude). The use of an ensemble of climate models can improve the outcome of projections [37], and considering various altitudes allows for a more thorough understanding of changes in atmospheric conditions. Although many general circulation models are available, and cover a range of variables at different altitudes and under all RCPs worldwide, we advise against using them directly in ecological studies as they have low spatial resolutions and require downscaling to suit the small scale of animal movement. RCMs provide such downscaled data, and it is important to note that the characteristics of data provided by many RCMs are decided based on the needs of the end-users (e.g. ecologists). We therefore encourage ecologists to make contact with RCM developers in their region for collaboration and to negotiate their specific data requirements.

Atmospheric conditions are the facilitators of migration in many long- and short-distance migrants worldwide [12,14]. Investigating how climate change can disturb wind support for migratory species is crucial, particularly for species that depend on the wind to cross ecological barriers such as water bodies and deserts (e.g. [38,39]), and those that are predicted to be exposed to longer journeys due to range shifts caused by climate change [2].

Although our study covered only a small portion of the autumn migratory route of the study species, it is important to note that due to the uneven impacts of climate change in different parts of a single migration journey [40], local-scale and high-resolution studies are required to address these issues efficiently. Additionally, modelling the complete routes of long-distance migratory birds, or parts that include flying over land (e.g. the spring migration of Oriental honey-buzzards [41]), will involve challenges, as birds in such circumstances are not only affected by atmospheric conditions, but also by changes in land use and biotic interactions. Therefore, apart from atmospheric conditions, changes in the quality and distribution of suitable stopover and refuelling areas need to be accounted for as they might also alter the migratory routes of birds and lead to deviations from optimal wind-defined traditional routes.

Additionally, it is important to gain better knowledge of the flexibility and adaptive response of migratory species to a range of wind conditions. This can be studied by taking advantage of among-year variations in wind conditions by monitoring the migratory behaviour of individuals in different years using high-resolution tracking.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the CORDEX-East Asia Databank, which is responsible for the CORDEX dataset, and we thank the National Institute of Meteorological Research (NIMR), three universities in the Republic of Korea (Seoul National University, Yonsei University, Kongju National University) and other cooperative research institutes in East Asia region for producing and making available their model output. We are grateful to Seok-Woo Shin and Song-Yee Hong for assisting us in manipulation of CORDEX data. We also thank J. Shamoun-Baranes, I. Takayabu (Japanese Meteorological Research Institute), W. Goymann and R. Kraus for valuable comments and discussions. We also thank J. Hupp for improving the English.

Ethics

All fieldwork in this project was licensed by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment.

Data accessibility

Input data and R scripts: https://github.com/mahle68/ensemble_modeling.

Authors' contributions

N.M.Y. and H.H. conceived and coordinated the study, provided the tracking data and revised the manuscript. E.N. designed the study, carried out the analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant no. 26440245 and the Japanese Ministry of the Environment.

References

- 1.Robinson A, et al. 2009. Travelling through a warming world: climate change and migratory species. Endanger. Spec. Res. 7, 87–99. ( 10.3354/esr00095) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huntley B, Collingham YC, Green RE, Hilton GM, Rahbek C, Willis SG. 2006. Potential impacts of climatic change upon geographical distributions of birds. Ibis 148, 8–28. ( 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00523.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordo O. 2007. Why are bird migration dates shifting? A review of weather and climate effects on avian migratory phenology. Clim. Res. 35, 37 ( 10.3354/cr00713) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knudsen E, et al. 2011. Challenging claims in the study of migratory birds and climate change. Biol. Rev. 86, 928–946. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00179.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiedler W. 2003. Recent changes in migratory behaviour of birds: a compilation of field observations and ringing data. In Avian migration (eds Berthold P, Gwinner E, Sonnenschein E), pp. 21–38. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Gils JA, et al. 2016. Body shrinkage due to Arctic warming reduces red knot fitness in tropical wintering range. Science 352, 819–821. ( 10.1126/science.aad6351) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SÆther B-E, Sutherland WJ, Engen S. 2004. Climate influences on avian population dynamics. Adv. Ecol. Res. 35, 185–209. ( 10.1016/S0065-2504(04)35009-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinelschikova A, Kosarev V, Panov I, Baushev AN. 2007. The influence of wind conditions in Europe on the advance in timing of the spring migration of the song thrush (Turdus philomelos) in the south-east Baltic region. Int. J. Biometeorol. 51, 431–440. ( 10.1007/s00484-006-0077-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd H. 2003. Spring arrival of passerine migrants in Iceland. Ringing Migr. 21, 193–201. ( 10.1080/03078698.2003.9674291) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zalakevicius M, Bartkeviciene G, Raudonikis L, Janulaitis J. 2006. Spring arrival response to climate change in birds: a case study from eastern Europe. J. Ornithol. 147, 326–343. ( 10.1007/s10336-005-0016-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sepp M, Palm V, Leito A, Päädam K, Truu J. 2011. Effect of atmospheric circulation types on spring arrival of migratory birds and long-term trends in the first arrival dates in Estonia. Est. J. Ecol. 60, 111–131. ( 10.3176/eco.2011.2.03) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kranstauber B, Weinzierl R, Wikelski M, Safi K. 2015. Global aerial flyways allow efficient travelling. Ecol. Lett. 18, 1338–1345. ( 10.1111/ele.12528) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alerstam T. 1979. Wind as selective agent in bird migration. Ornis Scand. 10, 76–93. ( 10.2307/3676347) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liechti F. 2006. Birds: blowin’ by the wind? J. Ornithol. 147, 202–211. ( 10.1007/s10336-006-0061-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vansteelant WMG, Shamoun-Baranes J, van Manen W, van Diermen J, Bouten W. 2017. Seasonal detours by soaring migrants shaped by wind regimes along the East Atlantic Flyway. J. Anim. Ecol. 86, 415–704. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12593) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nourani E, Yamaguchi NM. 2017. The effects of atmospheric currents on the migratory behavior of soaring birds: a review. Ornithol. Sci. 16, 5–15. ( 10.2326/osj.16.5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elith J, Kearney M, Phillips S. 2010. The art of modelling range-shifting species. Method Ecol. Evol. 1, 330–342. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00036.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nourani E, Yamaguchi NM, Manda A, Higuchi H. 2016. Wind conditions facilitate the seasonal water-crossing behaviour of Oriental Honey-buzzards Pernis ptilorhynchus over the East China Sea. Ibis 158, 506–518. ( 10.1111/ibi.12383) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi N, Arisawa Y, Shimada Y, Higuchi H. 2012. Real-time weather analysis reveals the adaptability of direct sea-crossing by raptors. J. Ethol. 30, 1–10. ( 10.1007/s10164-011-0301-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RP. 2013. A framework for using niche models to estimate impacts of climate change on species distributions. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1297, 8–28. ( 10.1111/nyas.12264) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vansteelant WMG, Bouten W, Klaassen RHG, Koks BJ, Schlaich AE, van Diermen J, van Loon EE, Shamoun-Baranes J. 2015. Regional and seasonal flight speeds of soaring migrants and the role of weather conditions at hourly and daily scales. J. Avian Biol. 46, 25–39. ( 10.1111/jav.00457) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shamoun-Baranes J, Leshem Y, Yom-Tov Y, Liechti O. 2003. Differential use of thermal convection by soaring birds over central Israel. Condor 105, 208–218. ( 10.1650/0010-5422%282003%291050208%3ADUOTCB%5D2.0.CO%3B2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thuiller W, Lafourcade B, Engler R, Araújo MB. 2009. BIOMOD—a platform for ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Ecography 32, 369–373. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05742.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thuiller W, Georges D, Engler R, Georges MD, Thuiller CW.2012. Package ‘biomod2’. See https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/biomod2/biomod2.pdf .

- 25.R Development Core Team. 2016. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 26.IPCC. 2013. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker TF, et al.), p. 1535 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meinshausen M, et al. 2011. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim. Change 109, 213 ( 10.1007/s10584-011-0156-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzpatrick M, Hargrove W. 2009. The projection of species distribution models and the problem of non-analog climate. Biodivers. Conserv. 18, 2255–2261. ( 10.1007/s10531-009-9584-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehikoinen E, Sparks TH. 2010. Changes in migration. In Effects of climate change on birds (eds Møller AP, Fiedler W, Berthold P), pp. 89–112. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonker RM, et al. 2013. Genetic consequences of breaking migratory traditions in barnacle geese Branta leucopsis. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5835–5847. ( 10.1111/mec.12548) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.López-López P, García-Ripollés C, Urios V. 2014. Individual repeatability in timing and spatial flexibility of migration routes of trans-Saharan migratory raptors. Curr. Zool. 60, 642–652. ( 10.1093/czoolo/60.5.642) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vardanis Y, Klaassen RHG, Strandberg R, Alerstam T. 2011. Individuality in bird migration: routes and timing. Biol. Lett. 7, 502–505. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1180) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higuchi H, et al. 2005. Migration of Honey-buzzards Pernis apivorus based on satellite tracking. Ornithol. Sci. 4, 109–115. ( 10.2326/osj.4.109) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agostini N, Mellone U. 2007. Migration strategies of Oriental Honey-buzzards Pernis ptilorhyncus breeding in Japan. Forktail 23, 182. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill RE Jr, Douglas DC, Handel CM, Tibbitts TL, Hufford G, Piersma T. 2014. Hemispheric-scale wind selection facilitates bar-tailed godwit circum-migration of the Pacific. Anim. Behav. 90, 117–130. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.01.020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulido F, Berthold P. 2010. Current selection for lower migratory activity will drive the evolution of residency in a migratory bird population. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 7341–7346. ( 10.1073/pnas.0910361107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tebaldi C, Knutti R. 2007. The use of the multi-model ensemble in probabilistic climate projections. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 365, 2053–2075. ( 10.1098/rsta.2007.2076) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strandberg R, Klaassen RH, Hake M, Alerstam T. 2009. How hazardous is the Sahara Desert crossing for migratory birds? Indications from satellite tracking of raptors. Biol. Lett. 6, 297–300. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0785) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erni B, Liechti F, Bruderer B. 2005. The role of wind in passerine autumn migration between Europe and Africa. Behav. Ecol. 16, 732–740. ( 10.1093/beheco/ari046) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Møller AP, Fiedler W, Berthold P. 2010. Effects of climate change on birds. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaguchi N, et al. 2008. The large-scale detoured migration route and the shifting pattern of migration in Oriental honey-buzzards breeding in Japan. J. Zool. 276, 54–62. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00466.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Input data and R scripts: https://github.com/mahle68/ensemble_modeling.