Abstract

The neuro-anatomical substrates of major depressive disorder (MDD) are still not well understood, despite many neuroimaging studies over the past few decades. Here we present the largest ever worldwide study by the ENIGMA (Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis) Major Depressive Disorder Working Group on cortical structural alterations in MDD. Structural T1-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from 2148 MDD patients and 7957 healthy controls were analysed with harmonized protocols at 20 sites around the world. To detect consistent effects of MDD and its modulators on cortical thickness and surface area estimates derived from MRI, statistical effects from sites were meta-analysed separately for adults and adolescents. Adults with MDD had thinner cortical gray matter than controls in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), anterior and posterior cingulate, insula and temporal lobes (Cohen's d effect sizes: −0.10 to −0.14). These effects were most pronounced in first episode and adult-onset patients (>21 years). Compared to matched controls, adolescents with MDD had lower total surface area (but no differences in cortical thickness) and regional reductions in frontal regions (medial OFC and superior frontal gyrus) and primary and higher-order visual, somatosensory and motor areas (d: −0.26 to −0.57). The strongest effects were found in recurrent adolescent patients. This highly powered global effort to identify consistent brain abnormalities showed widespread cortical alterations in MDD patients as compared to controls and suggests that MDD may impact brain structure in a highly dynamic way, with different patterns of alterations at different stages of life.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the single most common psychiatric disorder, affecting approximately 350 million people each year.1 Even so, its pathogenesis and profile of effects in the brain are still not clear. Therefore, in 2013, we initiated the MDD Working Group within the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) consortium (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/) in which researchers around the world collaborate to boost statistical power to elucidate brain abnormalities in MDD. Recently, we reported subcortical volume differences between MDD patients and healthy controls that were related to clinical characteristics, based on data from 8927 individuals using an individual participant data-based meta-analysis approach. Subcortical volume differences were the greatest in the hippocampus, with the strongest effects in recurrent or early-onset patients.2 Here we present results on cortical structural differences in an even larger sample (N=10 105).

With regard to cortical structural abnormalities in MDD, prior magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, summarized in retrospective meta-analyses of individually published works, mainly implicate the (para)limbic circuitry, including dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (PFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and (rostral) anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), albeit with large variability across studies.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Findings are inconclusive regarding the temporal and lateral PFC.4, 8 Inconsistencies arise owing to differences in scanning and analysis methods, the limited power to detect subtle effects in small samples and clinical variations in medication status,6 lifetime disease burden,6 age at disease onset9 and adult vs adolescent study samples.10

Differences in data acquisition protocols and processing and differences in statistical analyses performed are a key source of heterogeneity. For example, different techniques for assessing morphometric deficits in MDD are used. Many studies use automated MRI analyses such as voxel-based morphometry,11 which avoid labour-intensive manual tracings and improve reproducibility. Others use surface-based methods that generate detailed maps of cortical thickness and surface area, which may differ in their underlying cellular mechanisms and genetic control.12 In addition, retrospective meta-analyses sometimes only include focused or hypothesis-driven studies adopting a region of interest approach (for example, ACC, OFC) with no information on other regions or studies that use coarse or unspecific anatomical regions such as ‘frontal lobe'.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 These approaches may not resolve more subtle or localized patterns of effects.

Here we addressed some of these issues by performing the largest coordinated worldwide meta-analysis of cortical structural abnormalities in patients diagnosed with MDD relative to healthy controls. We extracted cortical thickness and surface area estimates in 2148 MDD patients and 7957 healthy individuals using harmonized data analysis strategies across all sites.13 Compared to healthy controls, adult MDD studies generally report cortical thinning, but adolescent MDD studies have reported both cortical thinning and thickening14, 15, 16, 17 during mid-to-late adolescence. These apparent differences prompted us to analyse adolescent and adult patients separately, with adults defined here as individuals aged >21 years. We set the age cut-off for adult versus adolescent analyses at ⩽21 years, based on 1) evidence of accelerated cortical thinning followed by decelerated thinning in young adulthood during normal brain development18 and 2) the presence of a positive correlation between depressive symptoms and ventromedial PFC in individuals with MDD up to 22 years old.19 Additional stratifying variables were single vs recurrent episodes, antidepressant medication use, index episode severity and, in the adult sample, adolescent- vs adult-onset.

Materials and Methods

Samples

The ENIGMA MDD Working Group currently includes 20 international groups with neuroimaging and clinical data from MDD patients and healthy controls (participating sites are mapped in Supplementary Figure S1). Overall, we analysed data from 10 105 people, including 2148 MDD patients and 7957 healthy controls. Each sample's demographics are detailed in Supplementary Table S1 and clinical characteristics in Supplementary Table S2. Supplementary Table S3 lists exclusion criteria for study enrolment. All participating sites obtained approval from local institutional review boards and ethics committees, and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Image processing and analysis

Structural T1-weighted MRI brain scans were acquired at each site and analysed locally using harmonized analysis and quality-control protocols from the ENIGMA consortium; in this case, all cortical parcellations were performed with the freely available and validated segmentation software FreeSurfer (versions 5.1 and 5.3).20 Image acquisition parameters and software descriptions are given in Supplementary Table S4. Segmentations of 68 (34 left and 34 right) cortical gray matter regions based on the Desikan–Killiany atlas21 and two whole-hemisphere measures were visually inspected and statistically evaluated for outliers following standardized ENIGMA protocols (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/protocols/imaging-protocols). Further details on image exclusion criteria and quality control may be found in Supplementary Information SI1.

Statistical framework for meta-analysis

We examined group differences in cortical thickness and surface area between patients and controls within each sample using multiple linear regression models. In the primary analysis, the outcome measures were from each of 70 cortical regions of interest (68 regions and two whole-hemisphere average thickness or total surface area measures). A binary indicator of diagnosis (0=controls, 1=patients) was the predictor of interest. All models were adjusted for age and sex. Additional covariates were included whenever necessary to control for scanner differences within each sample. To ease comparisons with prior work,2, 22 effect size estimates were calculated using Cohen's d metric computed from the t-statistic of the diagnosis indicator variable from the regression models. Similarly, for models testing interactions (that is, sex-by-diagnosis and age-by-diagnosis) a multiplicative predictor was the predictor of interest with the main effect of each predictor included in the model and the effect size was calculated using the same procedure.

To detect potentially different effects of major depression with age, we separately analysed adolescent (age ⩽21 years) and adult participants (>21 years). Within the adolescent and adult divisions, we tested stratified models that split patients based on stage of illness (first episode vs recurrent). Furthermore, we examined associations between symptom severity at the time of scanning using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17)23 and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)24 and cortical thickness and surface area. Within the adult division, we stratified patients based on age at illness onset (adolescent-onset ⩽21 years; adult-onset >21 years25). Results of models that split patients based on antidepressant use at the time of their scan are reported in Supplementary Information SI1. Included samples and total sample sizes for each model are listed in the tables in 'Results' section. Throughout the manuscript, we report P-values corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure26 to ensure a false-discovery rate (FDR) limited at 5% for 70 measures (34 left hemisphere regions, 34 right hemisphere regions and 2 full-hemisphere measures, for left and right).

All regression models and effects size estimates were computed at each site separately and a final Cohen's d effect size estimate was obtained using an inverse variance-weighted random-effect meta-analysis model in R (metafor package, version 1.9-118). Only for the meta-analyses on correlation with symptom severity scores and number of episodes in recurrent patients, predictors were treated as continuous variables, so effect sizes were expressed as partial-correlation Pearson's r after removing nuisance variables (age, sex, and scan site). The final meta-analysed partial-correlation r was estimated with the same inverse variance-weighted random-effect meta-analysis model. See Supplementary Information SI1 for full meta-analysis details.

Moderator analyses with meta-regression

The methods and results of the moderator analyses, using meta-regression analyses to test whether individual site characteristics explained a significant proportion of the variance in effect sizes across sites in the meta-analyses, are reported in Supplementary Information SI1.

Results

Adults

Cortical thickness and surface area differences between MDD patients and controls

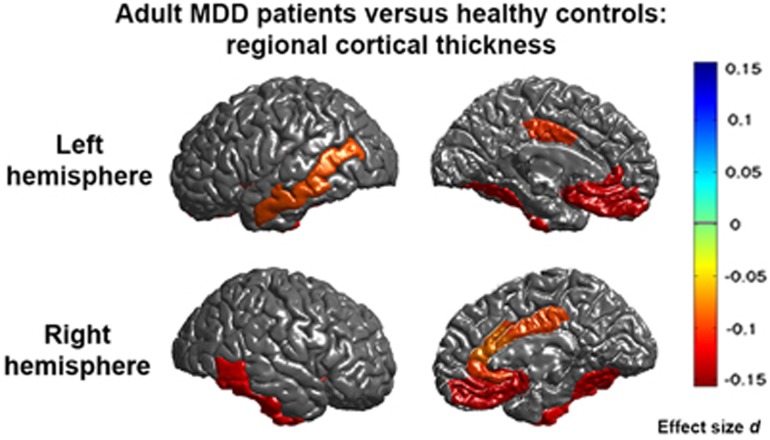

We found significant and consistent thinner cortices in the frontal and temporal lobes of adult depressed patients (N=1902) compared to controls (N=7658) in the bilateral medial OFC, fusiform gyrus, insula, rostral anterior and posterior cingulate cortex and unilaterally in the left middle temporal gyrus, right inferior temporal gyrus and right caudal ACC (see Figure 1 for significant regions, Supplementary Figure S11 for forest plots and Table 1 for full cortical thickness effects). Regions are listed in all tables in order of effect size, from the strongest to the weakest effect size. None of the regions analysed showed significant differences in cortical surface area (Supplementary Table S19) or evidence of sex-by-diagnosis or age-by-diagnosis interaction effects (Supplementary Tables S5, S6, S20 and S21).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis effect sizes for regions with a significant (PFDR<0.05) cortical thinning in adult major depressive disorder (MDD) patients compared to healthy controls. Negative effect sizes d indicate cortical thinning in MDD compared to controls.

Table 1. Full meta-analytic results for thickness of each structure for adult MDD patients vs controls comparison controlling for age, sex and scan center.

| Cohen's da (MDD vs CTL) | s.e. | 95% CI | % Difference | P-value | FDR P-value | I2 | No. of controls | No. of patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left medial orbitofrontal cortex | −0.134 | 0.038 | (−0.208 to −0.059) | −1.035 | 4.35E-04 | 0.015 | 23.025 | 7609 | 1888 |

| Right medial orbitofrontal cortex | −0.131 | 0.047 | (−0.224 to −0.039) | −1.102 | 0.006 | 0.035 | 46.981 | 7628 | 1896 |

| Left rostral anterior cingulate cortex | −0.130 | 0.044 | (−0.216 to −0.044) | −1.264 | 0.003 | 0.030 | 39.185 | 7656 | 1896 |

| Right lateral orbitofrontal cortex | −0.120 | 0.048 | (−0.214 to −0.026) | −0.704 | 0.012 | 0.058 | 48.548 | 7644 | 1902 |

| Left fusiform gyrus | −0.117 | 0.030 | (−0.176 to −0.058) | −0.576 | 9.51E-05 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 7645 | 1896 |

| Right inferior temporal gyrus | −0.117 | 0.036 | (−0.188 to −0.046) | −0.633 | 1.29E-03 | 0.018 | 18.006 | 7640 | 1885 |

| Right fusiform gyrus | −0.116 | 0.042 | (−0.198 to −0.033) | −0.564 | 0.006 | 3.47E-02 | 34.668 | 7649 | 1898 |

| Right insula | −0.115 | 0.041 | (−0.195 to −0.035) | −0.624 | 0.005 | 0.035 | 31.271 | 7651 | 1895 |

| Left insula | −0.111 | 0.034 | (−0.177 to −0.045) | −0.582 | 9.34E-04 | 0.018 | 10.683 | 7652 | 1898 |

| Left isthmus cingulate cortex | −0.104 | 0.046 | (−0.194 to −0.014) | −0.797 | 0.024 | 0.100 | 44.546 | 7655 | 1897 |

| Left posterior cingulate cortex | −0.099 | 0.030 | (−0.158 to −0.04) | −0.618 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.030 | 7654 | 1900 |

| Right rostral anterior cingulate cortex | −0.098 | 0.034 | (−0.165 to −0.031) | −0.993 | 0.004 | 0.034 | 12.104 | 7651 | 1899 |

| Right posterior cingulate cortex | −0.093 | 0.030 | (−0.152 to −0.034) | −0.624 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 7654 | 1900 |

| Left middle temporal gyrus | −0.090 | 0.031 | (−0.151 to −0.028) | −0.531 | 0.004 | 0.034 | 2.685 | 7591 | 1822 |

| Right middle temporal gyrus | −0.088 | 0.035 | (−0.156 to −0.021) | −0.492 | 0.011 | 0.053 | 13.072 | 7639 | 1886 |

| Right caudal anterior cingulate cortex | −0.080 | 0.030 | (−0.139 to −0.021) | −0.892 | 0.008 | 0.041 | <0.001 | 7655 | 1898 |

| Right superior frontal gyrus | −0.078 | 0.034 | (−0.145 to −0.011) | −0.379 | 0.023 | 0.099 | 12.509 | 7649 | 1900 |

| Right banks superior temporal sulcus | −0.074 | 0.034 | (−0.14 to −0.008) | −0.528 | 0.028 | 0.103 | 9.841 | 7613 | 1827 |

| Left pars orbitalis | −0.073 | 0.044 | (−0.158 to 0.012) | −0.533 | 0.094 | 0.212 | 38.655 | 7653 | 1900 |

| Left parahippocampal gyrus | −0.072 | 0.033 | (−0.137 to −0.007) | −0.895 | 0.030 | 0.103 | 8.631 | 7648 | 1896 |

| Right isthmus cingulate cortex | −0.071 | 0.038 | (−0.146 to 0.004) | −0.563 | 0.065 | 0.174 | 24.975 | 7651 | 1897 |

| Right pars orbitalis | −0.070 | 0.042 | (−0.152 to 0.013) | −0.501 | 0.100 | 0.212 | 35.595 | 7655 | 1900 |

| Left superior frontal gyrus | −0.066 | 0.030 | (−0.125 to −0.008) | −0.336 | 0.027 | 0.103 | <0.001 | 7652 | 1899 |

| Left inferior parietal cortex | −0.063 | 0.044 | (−0.149 to 0.022) | −0.359 | 0.147 | 0.277 | 38.619 | 7638 | 1894 |

| Left pars opercularis | −0.063 | 0.030 | (−0.122 to −0.004) | −0.299 | 0.037 | 0.123 | 0.003 | 7655 | 1897 |

| Right frontal pole | −0.062 | 0.036 | (−0.133 to 0.009) | −0.650 | 0.085 | 0.204 | 18.189 | 7657 | 1899 |

| Right parahippocampal gyrus | −0.061 | 0.030 | (−0.12 to −0.002) | −0.665 | 0.042 | 0.134 | 0.010 | 7654 | 1897 |

| Left banks superior temporal sulcus | −0.058 | 0.031 | (−0.118 to 0.002) | −0.423 | 0.059 | 0.173 | <0.001 | 7571 | 1781 |

| Left hemisphere average thickness | −0.057 | 0.031 | (−0.117 to 0.003) | −0.209 | 0.065 | 0.174 | 2.346 | 7658 | 1902 |

| Right entorhinal cortex | −0.055 | 0.030 | (−0.115 to 0.004) | −0.657 | 0.068 | 0.177 | <0.001 | 7602 | 1862 |

| Left pars triangularis | −0.054 | 0.030 | (−0.112 to 0.005) | −0.326 | 0.074 | 0.185 | <0.001 | 7651 | 1897 |

| Right supramarginal gyrus | −0.053 | 0.044 | (−0.139 to 0.032) | −0.273 | 0.223 | 0.370 | 38.371 | 7633 | 1874 |

| Right transverse temporal gyrus | −0.051 | 0.030 | (−0.11 to 0.008) | −0.413 | 0.088 | 0.204 | <0.001 | 7622 | 1894 |

| Left inferior temporal gyrus | −0.049 | 0.035 | (−0.117 to 0.019) | −0.273 | 0.158 | 0.291 | 12.727 | 7630 | 1872 |

| Right hemisphere average thickness | −0.049 | 0.033 | (−0.113 to 0.015) | −0.179 | 0.135 | 0.263 | 8.061 | 7658 | 1902 |

| Left lateral orbitofrontal cortex | −0.046 | 0.031 | (−0.107 to 0.014) | −0.280 | 0.130 | 0.260 | 1.851 | 7638 | 1898 |

| Left supramarginal gyrus | −0.045 | 0.037 | (−0.118 to 0.027) | −0.244 | 0.220 | 0.370 | 19.395 | 7609 | 1864 |

| Left caudal anterior cingulate cortex | −0.042 | 0.036 | (−0.113 to 0.028) | −0.481 | 0.240 | 0.377 | 17.908 | 7650 | 1900 |

| Right inferior parietal cortex | −0.041 | 0.044 | (−0.127 to 0.044) | −0.235 | 0.343 | 0.501 | 39.065 | 7641 | 1897 |

| Left entorhinal cortex | −0.041 | 0.038 | (−0.115 to 0.033) | −0.471 | 0.276 | 0.420 | 21.951 | 7605 | 1866 |

| Right rostral middle frontal gyrus | −0.038 | 0.045 | (−0.127 to 0.051) | −0.183 | 0.401 | 0.561 | 42.738 | 7650 | 1899 |

| Left rostral middle frontal gyrus | −0.037 | 0.030 | (−0.096 to 0.022) | −0.178 | 0.224 | 0.370 | 0.467 | 7653 | 1899 |

| Left transverse temporal gyrus | −0.035 | 0.030 | (−0.094 to 0.024) | −0.277 | 0.243 | 0.377 | <0.001 | 7635 | 1895 |

| Right pars triangularis | −0.031 | 0.046 | (−0.122 to 0.059) | −0.179 | 0.501 | 0.674 | 44.727 | 7645 | 1897 |

| Right superior temporal gyrus | −0.031 | 0.030 | (−0.09 to 0.029) | −0.184 | 0.314 | 0.468 | <0.001 | 7587 | 1820 |

| Left precuneus | −0.024 | 0.039 | (−0.101 to 0.053) | −0.115 | 0.541 | 0.701 | 27.766 | 7649 | 1893 |

| Left lateral occipital cortex | −0.023 | 0.044 | (−0.109 to 0.063) | −0.131 | 0.605 | 0.756 | 39.881 | 7645 | 1898 |

| Right precentral gyrus | −0.022 | 0.040 | (−0.101 to 0.057) | −0.132 | 0.581 | 0.739 | 29.869 | 7643 | 1894 |

| Left precentral gyrus | −0.020 | 0.031 | (−0.08 to 0.04) | −0.115 | 0.516 | 0.681 | 2.091 | 7637 | 1895 |

| Right pars opercularis | −0.017 | 0.044 | (−0.103 to 0.069) | −0.087 | 0.694 | 0.823 | 39.291 | 7651 | 1896 |

| Left caudal middle frontal gyrus | −0.014 | 0.041 | (−0.094 to 0.067) | −0.069 | 0.741 | 0.844 | 32.111 | 7647 | 1898 |

| Right lingual gyrus | −0.012 | 0.030 | (−0.071 to 0.047) | −0.069 | 0.692 | 0.823 | <0.001 | 7641 | 1894 |

| Left frontal pole | −0.011 | 0.037 | (−0.084 to 0.062) | −0.113 | 0.772 | 0.858 | 21.413 | 7656 | 1899 |

| Right paracentral lobule | −0.006 | 0.030 | (−0.064 to 0.053) | −0.031 | 0.854 | 0.910 | <0.001 | 7651 | 1901 |

| Left superior parietal cortex | −0.005 | 0.040 | (−0.084 to 0.074) | −0.026 | 0.897 | 0.910 | 30.628 | 7645 | 1896 |

| Left paracentral lobule | −0.003 | 0.035 | (−0.072 to 0.066) | −0.017 | 0.932 | 0.932 | 14.789 | 7650 | 1899 |

| Right lateral occipital cortex | 0.005 | 0.033 | (−0.06 to 0.071) | 0.032 | 0.871 | 0.910 | 9.491 | 7650 | 1898 |

| Right precuneus | 0.005 | 0.032 | (−0.057 to 0.068) | 0.027 | 0.864 | 0.910 | 6.038 | 7646 | 1894 |

| Left lingual gyrus | 0.006 | 0.030 | (−0.053 to 0.065) | 0.034 | 0.843 | 0.910 | 0.003 | 7640 | 1895 |

| Right caudal middle frontal gyrus | 0.006 | 0.044 | (−0.08 to 0.092) | 0.032 | 0.889 | 0.910 | 39.270 | 7650 | 1900 |

| Left temporal pole | 0.012 | 0.037 | (−0.06 to 0.084) | 0.119 | 0.747 | 0.844 | 18.834 | 7614 | 1871 |

| Left superior temporal gyrus | 0.012 | 0.031 | (−0.048 to 0.072) | 0.075 | 0.687 | 0.823 | 0.004 | 7551 | 1806 |

| Right temporal pole | 0.013 | 0.038 | (−0.062 to 0.088) | 0.144 | 0.731 | 0.844 | 23.178 | 7631 | 1871 |

| Right postcentral gyrus | 0.028 | 0.030 | (−0.031 to 0.087) | 0.157 | 0.355 | 0.507 | <0.001 | 7642 | 1897 |

| Right superior parietal cortex | 0.032 | 0.043 | (−0.053 to 0.117) | 0.159 | 0.463 | 0.635 | 38.069 | 7645 | 1895 |

| Left postcentral gyrus | 0.036 | 0.030 | (−0.023 to 0.095) | 0.200 | 0.227 | 0.370 | <0.001 | 7630 | 1894 |

| Left cuneus | 0.047 | 0.030 | (−0.012 to 0.106) | 0.288 | 0.120 | 0.246 | <0.001 | 7652 | 1897 |

| Right cuneus | 0.049 | 0.030 | (−0.009 to 0.108) | 0.303 | 0.100 | 0.212 | 0.005 | 7654 | 1896 |

| Right pericalcarine cortex | 0.081 | 0.059 | (−0.035 to 0.198) | 0.593 | 0.171 | 0.307 | 66.717 | 7633 | 1896 |

| Left pericalcarine cortex | 0.094 | 0.049 | (−0.003 to 0.191) | 0.662 | 0.057 | 0.173 | 51.503 | 7645 | 1894 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CTL, controls; FDR, false-discovery rate; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Adjusted Cohen's d is reported.

First vs recurrent episode adult MDD

Adult patients with recurrent depression (N=1302) compared to controls (N=7450) revealed cortical thinning in left medial OFC (Supplementary Figures S2 and S12). First-episode patients (N=535) compared to controls (N=7253) showed more widespread cortical thinning in bilateral fusiform gyrus, rostral ACC and insula and left medial orbitofrontal and superior frontal cortex, right caudal anterior and posterior cingulate cortex and right isthmus cingulate cortex (Supplementary Figures S3 and S13). No differences were detected between recurrent and first-episode patients (Supplementary Table S9). Similar to the overall MDD group analysis, no cortical surface area differences were detected (Supplementary Tables S22–S24), and we found no significant correlations between thickness and surface area and the number of depressive episodes in recurrent patients (N=496; Supplementary Table S10).

Age of onset in adult MDD

Cortical thinning was observed in patients with an adult age of illness onset (>21 years, N=1214) compared to controls (N=3329) in bilateral insula, rostral anterior, posterior and isthmus cingulate cortex, fusiform gyrus, medial OFC, right caudal ACC and right inferior temporal gyrus (Supplementary Figures S4 and S14). We did not detect significant differences in cortical thickness in patients with an adolescent age of onset (⩽21 years, N=472), compared to controls (N=2885), (Supplementary Table S12) and when comparing adolescent-onset and adult-onset patients directly (Supplementary Table S13). Similarly, no surface area differences were detected in these subgroup analyses (Supplementary Tables S26–S28).

Correlation with symptom severity in adult patients

None of the cortical thickness measurements were correlated with symptom severity at study inclusion using the HDRS-17 (N=776) and BDI-II (N=943) questionnaires (Supplementary Tables S17 and S18). For surface area measurements, no associations were found with the HDRS-17 (Supplementary Table S32) and weak negative correlations were detected for BDI-II scores and surface area of the bilateral precuneus, left frontal pole and left postcentral gyrus (Supplementary Table S33, Supplementary Figures S7 and S17).

Adolescents

Cortical thickness and surface area differences between adolescent MDD patients and controls

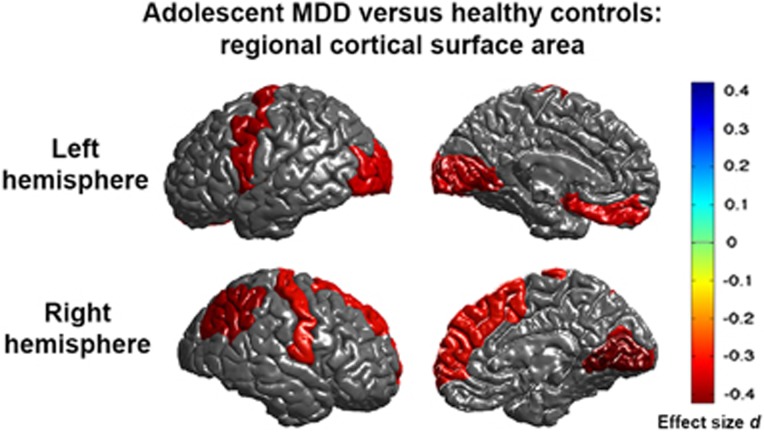

Left and right hemisphere total surface area was smaller in depressed adolescent patients (N=213) compared to adolescent controls (N=294). Regionally, surface area reductions were observed in bilateral lingual gyrus and pericalcarine gyrus, left lateral occipital cortex, left medial OFC, left precentral gyrus, right inferior parietal cortex, right superior frontal gyrus and right postcentral gyrus (see Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S18 and Table 2 for full tabulation of effects). No cortical thickness differences were detected between adolescent MDD patients and controls (Supplementary Table S34). Further, no cortical regions showed age-by-diagnosis or sex-by-diagnosis interaction effects (Supplementary Tables S35, S36, S45 and S46).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysed effect sizes for regions with a significant (PFDR<0.05) decrease in cortical surface area in adolescent major depressive disorder (MDD) patients compared to healthy controls. Negative effect sizes d indicate lower cortical surface area in MDD compared to controls.

Table 2. Full meta-analytic results for surface area of each structure for adolescent MDD patients vs controls comparison controlling for age, sex and scan center.

| Cohen's d (MDD vs CTL) | s.e. | 95% CI | % Difference | P-value | FDR P-value | I2 | No. of controls | No. of patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right lingual gyrus | −0.422 | 0.108 | (−0.633 to −0.211) | −5.870 | 9.12E-05 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 294 | 213 |

| Right inferior parietal cortex | −0.384 | 0.108 | (−0.595 to −0.173) | −5.320 | 3.64E-04 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 293 | 213 |

| Left precentral gyrus | −0.369 | 0.108 | (−0.581 to −0.157) | −4.071 | 6.51E-04 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 291 | 212 |

| Left lingual gyrus | −0.367 | 0.116 | (−0.595 to −0.139) | −5.165 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 11.038 | 294 | 213 |

| Right cuneus | −0.353 | 0.160 | (−0.667 to −0.038) | −5.049 | 0.028 | 0.103 | 49.494 | 292 | 212 |

| Left pericalcarine cortex | −0.339 | 0.108 | (−0.55 to −0.128) | −5.862 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.012 | 294 | 213 |

| Left cuneus | −0.336 | 0.182 | (−0.693 to 0.021) | −5.031 | 0.065 | 0.162 | 60.682 | 294 | 213 |

| Right pericalcarine cortex | −0.332 | 0.108 | (−0.543 to −0.12) | −5.548 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.005 | 293 | 212 |

| Left lateral occipital cortex | −0.330 | 0.108 | (−0.541 to −0.119) | −4.253 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.002 | 294 | 212 |

| Left medial orbitofrontal cortex | −0.329 | 0.109 | (−0.542 to −0.116) | −5.162 | 0.002 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 283 | 210 |

| Right hemisphere total surface area | −0.325 | 0.108 | (−0.536 to −0.114) | −3.386 | 0.003 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Left hemisphere total surface area | −0.320 | 0.107 | (−0.531 to −0.11) | −3.332 | 0.003 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Right postcentral gyrus | −0.305 | 0.108 | (−0.517 to −0.094) | −3.651 | 0.005 | 0.027 | <0.001 | 289 | 212 |

| Right superior frontal gyrus | −0.305 | 0.107 | (−0.516 to −0.095) | −3.916 | 0.005 | 0.027 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Right caudal middle frontal gyrus | −0.288 | 0.136 | (−0.555 to −0.02) | −5.188 | 0.035 | 0.116 | 32.049 | 294 | 211 |

| Left precuneus | −0.278 | 0.107 | (−0.488 to −0.068) | −3.540 | 0.010 | 0.052 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Right banks superior temporal sulcus | −0.266 | 0.108 | (−0.477 to −0.055) | −4.176 | 0.014 | 0.068 | 0.001 | 293 | 203 |

| Right medial orbitofrontal cortex | −0.250 | 0.111 | (−0.468 to −0.032) | −3.850 | 0.025 | 0.096 | 3.586 | 282 | 211 |

| Left postcentral gyrus | −0.248 | 0.108 | (−0.459 to −0.037) | −2.887 | 0.021 | 0.094 | <0.001 | 293 | 212 |

| Left rostral middle frontal gyrus | −0.247 | 0.109 | (−0.461 to −0.033) | −3.483 | 0.024 | 0.096 | 2.612 | 294 | 213 |

| Left caudal middle frontal gyrus | −0.247 | 0.107 | (−0.457 to −0.037) | −4.068 | 0.021 | 0.094 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Left superior parietal cortex | −0.245 | 0.167 | (−0.573 to 0.083) | −2.954 | 0.143 | 0.263 | 53.595 | 294 | 213 |

| Right middle temporal gyrus | −0.227 | 0.107 | (−0.438 to −0.017) | −3.235 | 0.034 | 0.116 | <0.001 | 293 | 206 |

| Left superior frontal gyrus | −0.222 | 0.107 | (−0.433 to −0.012) | −2.722 | 0.038 | 0.122 | <0.001 | 293 | 212 |

| Right superior parietal cortex | −0.221 | 0.149 | (−0.512 to 0.07) | −2.578 | 0.137 | 0.260 | 41.842 | 293 | 213 |

| Right rostral middle frontal gyrus | −0.218 | 0.153 | (−0.519 to 0.083) | −3.091 | 0.155 | 0.265 | 45.512 | 292 | 213 |

| Right precentral gyrus | −0.213 | 0.107 | (−0.424 to −0.003) | −2.426 | 0.047 | 0.142 | <0.001 | 290 | 213 |

| Left banks superior temporal sulcus | −0.212 | 0.111 | (−0.43 to 0.005) | −3.670 | 0.056 | 0.162 | 0.001 | 279 | 190 |

| Left inferior parietal cortex | −0.205 | 0.111 | (−0.422 to 0.013) | −2.937 | 0.065 | 0.162 | 4.975 | 294 | 213 |

| Right pars orbitalis | −0.201 | 0.107 | (−0.412 to 0.009) | −3.034 | 0.061 | 0.162 | <0.001 | 294 | 211 |

| Left paracentral gyrus | −0.200 | 0.107 | (−0.41 to 0.011) | −2.797 | 0.063 | 0.162 | <0.001 | 294 | 212 |

| Left fusiform gyrus | −0.196 | 0.148 | (−0.485 to 0.094) | −2.839 | 0.186 | 0.280 | 41.160 | 293 | 213 |

| Left frontal pole | −0.194 | 0.123 | (−0.435 to 0.048) | −3.013 | 0.116 | 0.243 | 19.476 | 294 | 213 |

| Left caudal anterior cingulate cortex | −0.187 | 0.151 | (−0.484 to 0.11) | −3.527 | 0.217 | 0.297 | 43.982 | 291 | 213 |

| Right inferior temporal gyrus | −0.185 | 0.107 | (−0.395 to 0.025) | −3.129 | 0.084 | 0.202 | <0.001 | 291 | 213 |

| Left rostral anterior cingulate cortex | −0.180 | 0.166 | (−0.505 to 0.145) | −3.977 | 0.277 | 0.365 | 53.020 | 293 | 213 |

| Right temporal pole | −0.180 | 0.107 | (−0.39 to 0.03) | −2.926 | 0.093 | 0.217 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Left superior temporal gyrus | −0.179 | 0.109 | (−0.393 to 0.035) | −2.237 | 0.101 | 0.221 | <0.001 | 283 | 198 |

| Right superior temporal gyrus | −0.179 | 0.108 | (−0.39 to 0.032) | −2.104 | 0.097 | 0.219 | 0.588 | 292 | 208 |

| Right precuneus | −0.178 | 0.134 | (−0.44 to 0.085) | −2.306 | 0.184 | 0.280 | 30.353 | 294 | 213 |

| Right posterior cingulate cortex | −0.175 | 0.114 | (−0.399 to 0.049) | −2.696 | 0.125 | 0.243 | 8.684 | 293 | 213 |

| Left pars triangularis | −0.166 | 0.107 | (−0.376 to 0.044) | −2.557 | 0.122 | 0.243 | 0.005 | 293 | 213 |

| Right parahippocampal gyrus | −0.165 | 0.107 | (−0.376 to 0.045) | −2.706 | 0.123 | 0.243 | <0.001 | 294 | 212 |

| Right caudal anterior cingulate cortex | −0.155 | 0.107 | (−0.365 to 0.056) | −2.998 | 0.149 | 0.263 | <0.001 | 293 | 213 |

| Right lateral occipital cortex | −0.154 | 0.107 | (−0.364 to 0.056) | −2.035 | 0.150 | 0.263 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Left middle temporal gyrus | −0.152 | 0.110 | (−0.367 to 0.064) | −2.255 | 0.168 | 0.279 | <0.001 | 283 | 196 |

| Right fusiform gyrus | −0.145 | 0.107 | (−0.355 to 0.066) | −2.157 | 0.178 | 0.280 | <0.001 | 294 | 211 |

| Left supramarginal gyrus | −0.141 | 0.107 | (−0.351 to 0.069) | −2.061 | 0.187 | 0.280 | <0.001 | 292 | 213 |

| Right insula | −0.141 | 0.107 | (−0.352 to 0.069) | −1.930 | 0.188 | 0.280 | <0.001 | 292 | 213 |

| Right paracentral gyrus | −0.140 | 0.107 | (−0.351 to 0.071) | −1.967 | 0.192 | 0.280 | <0.001 | 291 | 213 |

| Left entorhinal cortex | −0.137 | 0.108 | (−0.348 to 0.074) | −3.056 | 0.202 | 0.289 | <0.001 | 292 | 209 |

| Right pars triangularis | −0.135 | 0.107 | (−0.345 to 0.075) | −2.189 | 0.207 | 0.290 | <0.001 | 293 | 213 |

| Left temporal pole | −0.131 | 0.107 | (−0.34 to 0.079) | −2.086 | 0.222 | 0.298 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Left inferior temporal gyrus | −0.110 | 0.108 | (−0.322 to 0.101) | −1.824 | 0.305 | 0.396 | <0.001 | 290 | 212 |

| Right rostral anterior cingulate cortex | −0.110 | 0.136 | (−0.376 to 0.156) | −2.501 | 0.418 | 0.504 | 31.569 | 292 | 212 |

| Right isthmus cingulate cortex | −0.110 | 0.118 | (−0.341 to 0.121) | −1.774 | 0.350 | 0.437 | 13.248 | 293 | 213 |

| Left transverse temporal gyrus | −0.100 | 0.107 | (−0.311 to 0.11) | −1.660 | 0.349 | 0.437 | 0.002 | 294 | 213 |

| Left parahippocampal gyrus | −0.099 | 0.113 | (−0.321 to 0.123) | −2.112 | 0.383 | 0.470 | 7.948 | 294 | 211 |

| Left posterior cingulate cortex | −0.085 | 0.172 | (−0.422 to 0.253) | −1.246 | 0.624 | 0.704 | 56.442 | 293 | 213 |

| Left pars opercularis | −0.075 | 0.107 | (−0.286 to 0.135) | −1.208 | 0.485 | 0.575 | <0.001 | 293 | 211 |

| Right lateral orbitofrontal cortex | −0.065 | 0.124 | (−0.309 to 0.178) | −0.917 | 0.600 | 0.689 | 20.640 | 294 | 211 |

| Right transverse temporal gyrus | −0.060 | 0.107 | (−0.27 to 0.149) | −1.000 | 0.572 | 0.668 | <0.001 | 294 | 213 |

| Left pars orbitalis | −0.051 | 0.139 | (−0.324 to 0.221) | −0.774 | 0.712 | 0.791 | 34.678 | 292 | 213 |

| Left insula | −0.036 | 0.154 | (−0.337 to 0.265) | −0.405 | 0.815 | 0.852 | 45.762 | 291 | 213 |

| Right pars opercularis | −0.031 | 0.107 | (−0.241 to 0.179) | −0.495 | 0.773 | 0.845 | <0.001 | 292 | 213 |

| Right supramarginal gyrus | −0.029 | 0.108 | (−0.24 to 0.182) | −0.413 | 0.789 | 0.849 | <0.001 | 288 | 211 |

| Right entorhinal cortex | −0.021 | 0.109 | (−0.235 to 0.193) | −0.462 | 0.847 | 0.872 | 0.001 | 291 | 209 |

| Left lateral orbitofrontal cortex | 0.010 | 0.180 | (−0.342 to 0.363) | 0.152 | 0.955 | 0.955 | 60.017 | 294 | 213 |

| Left isthmus cingulate cortex | 0.016 | 0.121 | (−0.221 to 0.253) | 0.266 | 0.896 | 0.909 | 16.747 | 293 | 212 |

| Right frontal pole | 0.064 | 0.258 | (−0.441 to 0.569) | 0.989 | 0.803 | 0.851 | 80.174 | 294 | 213 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CTL, controls; FDR, false-discovery rate; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Adjusted Cohen's d is reported.

First vs recurrent episode adolescent MDD

Adolescents with recurrent depression (N=104) showed reductions in left and right hemisphere overall surface area compared to controls (N=142). Regionally, surface area reductions were observed in bilateral inferior parietal cortex and caudal middle frontal gyrus and left fusiform gyrus, left lateral occipital cortex, left precuneus, left superior parietal cortex, left medial OFC, right banks of the superior temporal sulcus, right lingual gyrus, right pericalcarine gyrus and right postcentral gyrus (Supplementary Figures S8 and S19, Supplementary Table S48). First-episode patients (N=80) showed no detectable differences, when compared to controls (N=154) or the recurrent adolescent MDD group (Supplementary Tables S47 and S49). No cortical thickness differences were found in adolescent MDD for first-episode or recurrence subgroups (Supplementary Tables S37–S39); similarly, no correlations with the number of episodes were detected for surface area or thickness in recurrent adolescent MDD patients (Supplementary Tables S40 and S50).

Correlations with symptom severity in adolescent MDD

We did not detect significant differences in cortical thickness or surface area when examining the effects of symptom severity at study inclusion using the HDRS-17 (N=134) questionnaire (Supplementary Tables S44 and S54), whereas BDI-II scores were available only for a small group of adolescent patients (N=31), precluding meaningful comparisons.

Moderating effects on cortical thickness and surface area

Results of the moderator analyses can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Discussion

In the largest analysis to date of cortical structural measures, we applied an individual participant data-based meta-analytic approach to brain MRI data from >10 000 people, of whom around one-fifth were affected by MDD. We found significant differences in cortical brain structures in adolescent and adult MDD and specific associations with clinical characteristics.

Cortical thickness

Adult MDD patients had cortical thickness deficits in 13 (of 68) regions examined. Cortical thinning was generally observed bilaterally, in regions that encompassed the medial PFC, rostral anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, insula and fusiform gyrus. Unilateral effects were observed in left middle temporal gyrus and right inferior temporal and right caudal ACC. Our findings of lower cortical thickness in medial PFC and ACC are consistent with prior meta-analyses.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Our findings extend previous findings by demonstrating structural abnormalities in the temporal lobe (middle and inferior temporal and fusiform gyri), posterior cingulate cortex and insula. The large sample also adds to our understanding of how reproducible and consistent these effects are likely to be when surveying cohorts worldwide.

A key feature of these regions is their close interaction with the limbic system, consistent with the general pathophysiological model of MDD that posits dysfunctional limbic–cortical circuits.27, 28 The dorsal and rostral ACC are functionally heterogeneous, supporting task monitoring, conflict detection, emotion regulation, social cognition and executive functions.29 The insular cortex is similarly multifunctional and engaged in visceroception, autonomic response regulation and attentional switches (for example, Menon and Uddin30). These regions show consistent structural differences in this cross-sectional morphometric study that may contribute to the broad spectrum of emotional, cognitive and behavioural disturbances observed in MDD.

Although effect sizes were relatively small (d −0.08 to −0.13, percentage of difference −0.5% to −1.3%, with overall low-to-medium heterogeneity among studies; that is, I2 for most regions between 0% and 50%) and in the range of previously reported hippocampal volume reduction,2 the medial OFC showed the largest effect sizes (d −0.13, percentage of difference −1.1%). The lower medial wall of the PFC (medial OFC according to the Desikan–Killiany atlas21 in FreeSurfer) contains the subgenual ACC (sgACC), subcallosal gyrus and medial OFC and has dense connections to the hypothalamus as the primary site of stress response regulation.31 These findings concur with postmortem findings of OFC structural deficits,32 OFC/sgACC-specific volumetric meta-analyses,8, 33 correlations between OFC thickness and cortisol levels34 and evidence of functional derangement of the sgACC in depression.35 Recently, right medial OFC thickness measured at baseline in healthy adolescent girls proved a strong predictor of the onset of depression in a multivariate model.36 The ventromedial PFC and OFC (including the sgACC) are critically involved in reinforcement learning,37 fear responsiveness and the adaptive control of emotions,38 which are disturbed in MDD, and have been associated with both a non-response to therapy39, 40 and a more unfavourable course of the illness.41 Distinct from our hippocampal volume finding,2 these effects were detectable already in first-episode patients with a medial OFC/ACC and insular focus, indifferent from recurrent patients who showed less widespread changes compared to controls. Further, no correlations with the number of episodes and no age-by-diagnosis effects were detected. Although these observations are based on cross-sectional data, we add to limited and conflicting reports of longitudinal volumetric changes in MDD42, 43 which suggest that progressive cortical abnormalities with growing disease load does not appear to be a general feature of depression.

With regard to age at onset, no significant differences were found between adult patients with an adolescent-onset (⩽21 years) and controls. In contrast, adult-onset was associated with significant cortical thinning in numerous frontal, cingulate and temporal regions. Interestingly, our prior work2 showed hippocampal volume alterations in adolescent-onset but not adult-onset patients. This result may suggest differential effects of stress-related remodelling or interactions with brain maturational mechanisms at different periods of disease onset. Cortical structural deficits were not found in adolescent-onset adult patients. This, however, may in part be due to lower statistical power in the smaller adolescent-onset compared with the adult-onset patient samples (N=472 vs N=1214). In addition, the lack of effects could perhaps be explained by the fact that adolescent-onset patients were younger than the adult-onset groups. Hence, greater cortical thinning in MDD may be more pronounced in adult-onset patients if the disease effects interact with increased aging of the brain,40, 44 but see also Truong et al.9 Following this logic, we performed a post-hoc moderator analysis examining the effects of mean age of patients in each sample on cortical thickness differences between adolescent-onset (adult) patients and controls. Samples with a higher mean age of patients indeed showed greater cortical thinning in the adolescent-onset group compared with controls (Supplementary Figure S22). Though not robust to conservative correction for multiple comparisons (trend-level PFDR=0.09 for the left medial OFC), this pattern fits the lack of detected thickness differences in our adolescent MDD vs adolescent controls analysis. Prior studies have reported mixed results with regard to cortical abnormalities in adolescent MDD, showing increased,15, 17 decreased14, 15, 16 or no differences in cortical thickness.45 Cortical thickness decreases linearly during adolescence46, 47, 48, 49 owing to synaptic pruning, myelination and other remodelling effects.50 In adolescent MDD, anxious and depressed symptoms have been associated with greater cortical thickness.19 In contrast, our current results and prior reports3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 provide consistent evidence for cortical thinning in adult MDD. These opposite effects would suggest a delay in maturation (that is, delay in thinning) of cortical thickness in adolescent MDD, resulting in greater cortical thickness during various stages of brain maturation but thinner cortex eventually. A possible explanation for the lack of cortical thickness effects in the current study is that 70% of our adolescents were 18–21 years, perhaps older than the most sensitive period to detect maturation delays.17, 19 Of note, although not significant, the left lateral OFC showed a medium effect size (d −0.31, percentage of difference −1.9%) for cortical thinning in adolescent MDD compared to controls, whereas cortical alterations in other regions were less clear.

Cortical surface area

Adult MDD patients showed no surface area abnormalities compared to controls. However, adolescent patients revealed smaller left and right hemisphere total surface areas, reflecting a diffuse pattern of local surface area deficits (effect sizes d between −0.31 to −0.42, percentage of difference −3.3 to −5.9%). Similar to cortical thickness alterations in adult MDD we observed surface area deficits in medial OFC and superior frontal gyrus, but also in primary and higher order visual, somatosensory and motor areas. These deficits were observed in recurrent patients, suggesting a negative effect of multiple episodes.

Cortical thinning starts from 2 to 4 years of age and continues across the lifespan, but overall cortical surface area follows a nonlinear and nonmonotonic developmental trajectory. The cortical surface expands until about 12 years, remains relatively stable and then decreases with age.46, 47, 48, 49 Development of cortical thickness and surface area are genetically independent12 and result from different neurobiological processes,50 representing distinct features of cortical development and aging. Cortical surface area abnormalities were not detected in our early-onset adult MDD patients, despite greater statistical power than for the adolescent analyses, so smaller cortical surface area in adolescent MDD may indicate delayed cortical maturation (that is, delayed expansion). Some regions with surface area abnormalities, including medial occipital regions (lingual gyrus), inferior parietal cortex, precentral gyrus, medial OFC and superior frontal gyrus, mature over a more prolonged time course during adolescence47, 49 and may be especially prone to a delay in maturation in adolescent MDD. Such delayed maturation may alter functional connections with other regions through decreases in growth and branching of dendritic trees and the number of synapses associated with gray matter volume,51 which may persist into adult MDD even if surface area measures normalize when transitioning into adulthood. The absence of cortical surface area abnormalities in the adult MDD patients with an early age of onset of depression could indicate such normalization; importantly, however, we still detected weak negative associations between severity of depressive symptoms and bilateral precuneus, left frontal pole and left postcentral gyrus surface area.

To our knowledge, alterations in cortical surface area abnormalities have not been evaluated in adolescents with MDD. Surface area deficits of the ventromedial PFC and precuneus in children and adolescents have been associated with higher anxiety,52 of the lingual and temporal gyri in children with childhood maltreatment,53 of prefrontal regions in children experiencing early life adversity54 and of the OFC in adolescents with conduct disorder.55 Importantly, early life stress, symptoms of anxiety and externalizing problems in childhood and early adolescence are all risk factors for early-onset MDD.56, 57

Cortical thickness and surface area abnormalities were mainly observed in first-episode MDD and adolescent MDD, respectively; this may indicate that cortical alterations are a feature of more heterogeneous MDD samples, including adolescent and first-episode adult MDD individuals who may go on to other outcomes, including bipolar or psychotic disorders, instead of adult MDD samples with a more 'pure' depressive phenotype (in our study characterized by recurrent MDD and adult MDD with an adolescent-onset of depression in whom the illness is confirmed over time). Indeed, lower surface areas in many of the same regions we observed in adolescent MDD in the current study were prospectively predictive of poor functional outcomes in young people with a clinically defined risk of developing psychosis.58 Similar analyses currently underway in the ENIGMA Schizophrenia and ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder working groups may clarify whether regional cortical surface area and thickness are altered to a greater extent in individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder than the alterations we observed in (adult) MDD. Nonetheless, prospective studies are needed to confirm this heterogeneity hypothesis.

Limitations

We did not adjust the regional comparisons for average thickness or total surface, respectively, as our main question was directed towards regional MDD-related changes instead of identifying regional effects that exceed a global effect. In contrast to surface area measures, which are highly associated with global measures of the brain (for example, intracranial volume, as a proxy for overall brain size), cortical thickness does not scale proportionately with brain size.59 In the current study, global deficits in cortical surface area (indicated by smaller left and right total surface area) were observed in adolescents with MDD. Therefore, our surface area results need to be interpreted as a diffuse, global surface deficit in adolescent MDD, with potential additional regional accentuation.

Furthermore, we used a ⩽21-year cutoff for adolescent vs adult MDD (cf. 'Introduction' section) consistent with our previous work.2 Definitions of adolescent MDD in the literature are not consistent, so alternative definitions might yield different results. Ideally, age and age of onset effects on brain abnormalities in MDD should be examined using a dimensional approach. However, in the current meta-analysis the statistical analyses were performed within each site, precluding this approach as few samples covered the entire lifespan. In addition, the age distribution of the adolescents (9% between 12 and 16 years, 21% between 16 and 18 years, 70% ⩾18 years) and the limited adolescent sample size (while larger than prior reports) may not be ideally sensitive to detect age-by-diagnosis interaction and cortical thickness effects. Future addition of more adolescent MDD samples to reflect a balanced age distribution may aid in detecting cortical changes associated with MDD at different stages of brain development.

In addition, when combining already collected data across worldwide samples, data collection protocols are not prospectively harmonized. Imaging acquisition protocols and clinical assessments therefore differed across studies, which limits analysis of sources of heterogeneity. The current study did not allow a reliable investigation of antidepressant medication effects on cortical structure because of its cross-sectional design and lack of detailed information on history, duration and type and dosage of antidepressant treatment. Still, in Supplementary Information SI1 we report on comparisons between patients taking antidepressant, antidepressant-free patients and controls. Adult patients using antidepressants showed robust and widespread effects of cortical thinning, whereas non-users showed cortical thinning only in the left medial OFC. However, this cross-sectional finding should not be interpreted as contradicting generally observed neuroprotective effects of antidepressants.60 It is likely confounded by clinical standards recommending antidepressant use mainly for severe or chronic MDD. In adolescent MDD patients, surface area deficits were observed in antidepressant-free patients and not in adolescents taking antidepressants. Clearly, intervention studies with preantidepressant and postantidepressant treatment comparisons of antidepressants are required to draw valid conclusions on the impact of antidepressant use on cortical structure.

Conclusions

Cortical structure is abnormal in numerous brain regions in adult and adolescent MDD. Medial OFC was consistently implicated across analyses—in adults, adolescents and analyses of clinical correlations. This finding reinforces the hypothesized prominent role of this region in depression throughout life. Other than subcortical volumetric effects, cortical thickness changes were robustly detectable in adult patients at their first episode. MDD may dynamically impact cortical development, and vice versa, with different patterns of alterations at different stages of life. Cortical thickness measurements showed greater differences than surface area measures in adult MDD, but consistent surface area deficits were found in adolescent MDD. Cortical thickness and surface area represent distinct morphometric features of the cortex and may be differentially affected by depression at various stages of life. Future (longitudinal) studies are needed to examine dynamic changes in the cortical regions we examined here and to relate such changes to symptom profiles, outcomes and treatment responses in MDD.

Acknowledgments

The ENIGMA-Major Depressive Disorder working group gratefully acknowledges support from the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) award (U54 EB020403 to Paul Thompson).

NESDA: The infrastructure for the NESDA study (www.nesda.nl) is funded through the Geestkracht program of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Zon-Mw, grant number 10-000-1002) and is supported by participating universities (VU University Medical Center, GGZ inGeest, Arkin, Leiden University Medical Center, GGZ Rivierduinen, University Medical Center Groningen) and mental health care organizations, see HYPERLINK "www.nesda.nl. Lianne Schmaal is supported by The Netherlands Brain Foundation Grant number F2014(1)-24 and the Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam grant (IPB-SE-15-PSYCH-Schmaal).

QTIM: QTIM was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (Project Grants No. 496682 and 1009064) and US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (RO1HD050735). Baptiste Couvy-Duchesne and Lachlan Strike are supported by a PhD scholarship from the University of Queensland. We are grateful to the twins for their generosity of time and willingness to participate in our study. We also thank the many research assistants, radiographers, and other staff at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute and the Centre for Advanced Imaging, University of Queensland.

MMDP 3T: Ontario Mental Health Foundation.

Bipolar Family Study: The Bipolar Family Study received funding from the European Union‘s Seventh Framework Programme for research under grant agreement n°602450. This study is also supported by Wellcome Trust award 104036/Z/14/Z.

CODE: The CODE cohort was collected from studies funded by Lundbeck and the German Research Foundation (WA 1539/4-1, SCHN 1204/3-1). Elizabeth Schramm is supported by a Grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft / German Research Association (SCHR 443/11-1).

MPIP: The MPIP Munich Morphometry Sample comprises patients included in Munich Antidepressant Response Signature study and the Recurrent Unipolar Depression (RUD) Case-Control study, and control subjects acquired at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Department of Psychiatry. We wish to acknowledge Rosa Schirmer, Elke Schreiter, Reinhold Borschke and Ines Eidner for image acquisition and data preparation, and Benno Pütz, Nazanin Karbalai, Darina Czamara, Till Andlauer and Bertram Müller-Myhsok for distributed computing support. We thank Dorothee P. Auer for initiation of the RUD study. The MARS study is supported by a grant of the Exzellenz-Stiftung of the Max Planck Society. This work has also been funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the framework of the National Genome Research Network (NGFN), FKZ 01GS0481.

SHIP: The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grants 01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103 and 01ZZ0403) the Ministry of Cultural Affairs as well as the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. MRI scans were supported by Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany. SHIP-LEGEND was supported by the German Research Foundation (GR1912/5-1).

Rotterdam Study: The Rotterdam Study is supported by the Erasmus MC and Erasmus University Rotterdam; Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO); Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW); Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE); Netherlands Genomics Initiative; Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports; European Commission (DG XII); and Municipality of Rotterdam.

Muenster Cohort: The Muenster Neuroimaging Cohort was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG; grant FOR 2107; DA1151/5-1 to UD) and Innovative Medizinische Forschung (IMF) of the Medical Faculty of Münster (DA120903 to UD, DA111107 to UD, and DA211012 to UD).

Stanford: NIMH Grant R01MH59259 to Ian Gotlib, and the National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (NSF IGERT) Recipient Award 0801700 and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF GRFP) DGE-1147470 to Matthew Sacchet.

Melbourne: The study was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Project Grants 1064643 (PI Harrison) and 1024570 (PI Davey).

Houston: Supported in part by NIMH grant R01 085667, The Dunn Foundation, and the Pat Rutherford, Jr. Endowed Chair in Psychiatry to JCS.

Imaging genetics Dublin and Clinical Depression Dublin: The study was supported by a Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) Stokes Professorship Grant to Thomas Frodl.

Novosibirsk: Russian Science Foundation grant #16-15-00128 to Lyubomir Aftanas. Sydney: This study was supported by the following National Health & Medical Research Council funding.

sources: Program Grant (No. 566529), Centres of Clinical Research Excellence Grant (No. 264611), Austr.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/mp)

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Jair Soares has participated in research funded by Forest, Merck, BMS, GSK and has been a speaker for Pfizer and Abbott. Andrew McIntosh has received support from Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer and Saccade Diagnostics. Carsten Konrad received fees for an educational program from Aristo Pharma, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, MagVenture, Servier, and Trommsdorff as well as travel support and speakers honoraria from Janssen, Lundbeck and Servier. Theo G.M. van Erp has consulted for Roche Pharmaceuticals Ltd., and has a contract with Otsuka Phamaceutical Co., Ltd (OPCJ). Knut Schnell has consulted for Roche Pharmaceuticals and Servier Pharmaceuticals. Henrik Walter has received a speaker honorarium from Servier, 9987.

Supplementary Material

References

- World Health Organization. Depression: a global public health concern, 2012. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/who_paper_depression_wfmh_2012.pdf (accessed 2 October 2015).

- Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, van Erp TGM, Sämann PG, Frodl T, Jahanshad N et al. Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry; e-pub ahead of print 30 June 2015; doi:10.1038/mp.2015.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kempton MJ. Structural neuroimaging studies in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 675–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Fornito A, Pantelis C, Yücel M. Gray matter abnormalities in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of voxel based morphometry studies. J Affect Disord 2012; 138: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. Gray matter volume in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Psychiatry Res 2013; 211: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y-J, Du M-Y, Huang X-Q, Lui S, Chen Z-Q, Liu J et al. Brain grey matter abnormalities in medication-free patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2014; 44: 2927–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D, McIntosh AM, Ebmeier KP, Munafò MR, Anderson IM. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in unipolar depression: systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2012; 22: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolschijn PCMP, van Haren NEM, Lensvelt-Mulders GJLM, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Brain volume abnormalities in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp 2009; 30: 3719–3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong W, Minuzzi L, Soares CN, Frey BN, Evans AC, MacQueen GM et al. Changes in cortical thickness across the lifespan in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res 2013; 214: 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulvershorn L, Cullen K, Anand A. Toward dysfunctional connectivity: a review of neuroimaging findings in pedriatic major depressive disorder. Brain Imaging Behav 2011; 5: 307–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry—the methods. Neuroimage 2000; 11: 805–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AM, Kochunov P, Blangero J, Almasy L, Zilles K, Fox PT et al. Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage 2010; 53: 1135–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Stein JL, Medland SE, Hibar DP, Vasquez AA, Renteria ME et al. The ENIGMA Consortium: large-scale collaborative analyses of neuroimaging and genetic data. Brain Imaging Behav 2014; 8: 153–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes AD, McCormick LM, Coryell WH, Nopoulos P. Rostral anterior cingulate cortex volume correlates with depressed mood in normal healthy children. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63: 391–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallucca E, MacMaster FP, Haddad J, Easter P, Dick R, May G et al. Distinguishing between major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder in children by measuring regional cortical thickness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shad MU, Muddasani S, Rao U. Gray matter differences between healthy and depressed adolescents: a voxel-based morphometry study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2012; 22: 190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds S, Carrey N, Jaworska N, Langevin LM, Yang X-R, Macmaster FP. Cortical thickness in youth with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Lebel C, Treit S, Evans A, Beaulieu C. Accelerated longitudinal cortical thinning in adolescence. Neuroimage 2014; 104: 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme S, Albaugh MD, Hudziak JJ, Botteron KN, Nguyen T-V, Truong C et al. Anxious/depressed symptoms are linked to right ventromedial prefrontal cortical thickness maturation in healthy children and young adults. Cereb Cortex 2014; 24: 2941–2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002; 33: 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006; 31: 968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Erp TGM, Hibar DP, Rasmussen JM, Glahn DC, Pearlson GD, Andreassen Oa et al. Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028 individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. Mol Psychiatry 2016; 21: 547–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23: 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess 1996; 67: 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazzi F. Classifying mood disorders by age-at-onset instead of polarity. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2009; 33: 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS. Modulating dysfunctional limbic-cortical circuits in depression: towards development of brain-based algorithms for diagnosis and optimised treatment. Br Med Bull 2003; 65: 193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct 2008; 213: 93–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM. Conflict monitoring and decision making: reconciling two perspectives on anterior cingulate function. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2007; 7: 356–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct 2010; 214: 655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL. Definition of the orbital cortex in relation to specific connections with limbic and visceral structures and other cortical regions. Ann NY Acad Sci 2007; 1121: 54–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G, Miguel-Hidalgo J, Wei J, Dilley G, Pittman S, Meltzer H et al. Morphometric evidence for neuronal and glial prefrontal cell pathology in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45: 1085–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek T, Kozeny J, Kopecek M, Alda M, Höschl C. Reduced subgenual cingulate volumes in mood disorders: a meta-analysis. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2008; 33: 91–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kakeda S, Watanabe K, Yoshimura R, Abe O, Ide S et al. Relationship between the cortical thickness and serum cortisol levels in drug-naïve, first-episode patients with major depressive disorder: a surface-based morphometric study. Depress Anxiety 2015; 32: 702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Savitz J, Trimble M. The subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorders. CNS Spectr 2008; 13: 663–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foland-Ross LC, Sacchet MD, Prasad G, Gilbert B, Thompson PM, Gotlib IH. Cortical thickness predicts the first onset of major depression in adolescence. Int J Dev Neurosci 2015; 46: 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan MP, Kolling N, Walton ME, Rushworth MFS. Re-evaluating the role of the orbitofrontal cortex in reward and reinforcement. Eur J Neurosci 2012; 35: 997–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller D, Delgado MR. Overlapping neural systems mediating extinction, reversal and regulation of fear. Trends Cogn Sci 2010; 14: 268–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redlich R, Opel N, Grotegerd D, Dohm K, Zaremba D, Bürger C et al The prediction of individual response to electroconvulsive therapy by structural MRI. JAMA Psychiatry 2016 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mackin RS, Tosun D, Mueller SG, Lee JY, Insel P, Schuff N et al. Patterns of reduced cortical thickness in late-life depression and relationship to psychotherapeutic response. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21: 794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JL, Batten LA, Tremblay P, Aldosary F, Blier P. A prospective, longitudinal study of the effect of remission on cortical thickness and hippocampal volume in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 18: pyv037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodl T, Koutsouleri N, Bottlender R, Born C, Jäger M, Scupin I et al. Depression-related variation in brain morphology over 3 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2013; 65: 1156–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Nopoulos P, Drevets W, Wilson T, Andreasen N. Subgenual prefrontal cortex volumes in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia: diagnostic specificity and prognostic implications. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1706–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HK, Jung WS, Ahn KJ, Won WY, Hahn C, Lee SY et al. Regional cortical thickness and subcortical volume changes are associated with cognitive impairments in the drug-naive patients with late-onset depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012; 37: 838–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle S, Lichter R, Dennison M, Vijayakumar N, Schwartz O, Byrne ML et al. Structural brain development and depression onset during adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171: 564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storsve AB, Fjell AM, Tamnes CK, Westlye LT, Overbye K, Aasland HW et al. Differential longitudinal changes in cortical thickness, surface area and volume across the adult life span: regions of accelerating and decelerating change. J Neurosci 2014; 34: 8488–8498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga LM, Langen M, Oranje B, Durston S. Unique developmental trajectories of cortical thickness and surface area. Neuroimage 2014; 87: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Brown TT, Bartsch H, Dale AM. Toward an integrative science of the developing human mind and brain: focus on the developing cortex. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2016; 18: 2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlien IK, Fjell AM, Tamnes CK, Grydeland H, Krogsrud SK, Chaplin TA et al. Organizing principles of human cortical development-thickness and area from 4 to 30 years: insights from comparative primate neuroanatomy. Cereb Cortex 2014; 26: 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. A small step for the cell, a giant leap for mankind: a hypothesis of neocortical expansion during evolution. Trends Neurosci 1995; 18: 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BJ. Plasticity of gray matter volume: the cellular and synaptic plasticity that underlies volumetric change. Dev Psychobiol 2011; 53: 456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman E, Thompson WK, Bartsch H, Hagler DJ, Chen C-H, Brown TT et al. Anxiety is related to indices of cortical maturation in typically developing children and adolescents. Brain Struct Funct 2015; e-pub ahead of print 17 July 2015; doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kelly PA, Viding E, Wallace GL, Schaer M, De Brito SA, Robustelli B et al. Cortical thickness, surface area, and gyrification abnormalities in children exposed to maltreatment: neural markers of vulnerability? Biol Psychiatry 2013; 74: 845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel AS, Hunt RH, Cowell RA, Van Den Heuvel SE, Gunnar MR, Thomas KM. Duration of early adversity and structural brain development in post-institutionalized adolescents. Neuroimage 2015; 105: 112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild G, Toschi N, Hagan CC, Goodyer IM, Calder AJ, Passamonti L. Cortical thickness, surface area, and folding alterations in male youths with conduct disorder and varying levels of callous–unemotional traits. NeuroImage Clin 2015; 8: 253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Vaidyanathan U, Miller MB, McGue M, Iacono WG. Premorbid risk factors for major depressive disorder: Are they associated with early onset and recurrent course? Dev Psychopathol 2014; 26: 1477–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Pettit JW, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Klein DN. Escalation to major depressive disorder among adolescents with subthreshold depressive symptoms: evidence of distinct subgroups at risk. J Affect Disord 2014; 158: 133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambeitz-Ilankovic L, Meisenzahl EM, Cabral C, von Saldern S, Von, Kambeitz J, Falkai P et al. Prediction of outcome in the psychosis prodrome using neuroanatomical pattern classification. Schizophr Res 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Im K, Lee J, Lyttelton O, Kim SH, Evans AC, Kim SI. Brain size and cortical structure in the adult human brain. Cereb Cortex 2008; 18: 2181–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati P, Radtchenko A, Boyer P. Neuroplasticity: from MRI to depressive symptoms. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2004; 14: S503–S510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.