To the Editor

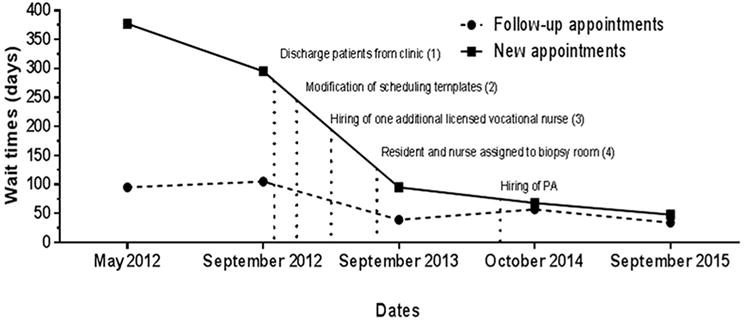

Increasing wait times at outpatient dermatology clinics1 are a significant challenge in safety net health systems,2 which provide patient care regardless of patient ability to pay.3 This study is a retrospective analysis reporting interventions that decreased patient wait times at the outpatient dermatology clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital system, which is the safety net health system in Dallas County, Texas. Each clinic is staffed by 7 to 8 residents assuming primary care of each patient and by 3 to 4 attending physicians. The clinic schedule consists of 3 half-day afternoon clinics per week, with an additional half-day dedicated to dermatologic surgeries. In May 2012, the average wait times for a new and follow-up patient were 377 and 95 days, respectively (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Wait times in Parkland dermatology clinic from May 2012 to September 2015. Wait times for appointments, as defined by time to third next-available appointment, decreased in the first year after interventions and were sustained for the following 2 years. The greatest improvements were observed in wait times for new patient appointments (bold line), but wait times for follow-up appointments (dashed line) also decreased. Interventions are indicated by vertical dotted lines. PA, Physician assistant.

To decrease long wait times, we performed a root-cause analysis to identify areas for improvement. We found nursing staff numbers were inconsistent during clinic, residents performing biopsies were delayed waiting for nurse availability, and numbers of patients scheduled were inconsistent between clinics. We addressed long wait times by: (1) discharging patients with stable, low-acuity skin problems (eg, mild acne) from clinic to follow-up with their primary care physicians; (2) changing scheduling templates by establishing goal numbers of new and established patients per clinic to increase schedule consistency; (3) hiring 1 additional licensed vocational nurse and extending work shifts of support staff so that sufficient staffing was available throughout the clinic duration; and (4) designating a resident and nurse to perform biopsies for the whole clinic to limit clinic delays. One year later, a physician assistant was hired to support increasing clinic patient volume and maintaining short wait times (Fig 1).

From May 2012 to September 2015, these interventions led to a decrease in wait times for new and established patients from 377 to 48 days, and from 95 to 34 days, respectively (Fig 1). Clinic wait times dramatically decreased within 1 year of implementation, and were maintained over the following 2 years, despite a 10% increase in patient referrals over this time period. Increasing nurse-to-resident provider ratio from 2:8 to 3:8 (Table I) and reorganizing support staff schedules were effective in decreasing new patient wait times between September 2012 and September 2013 by 31%. Assignment of biopsy nurse and resident, modification of scheduling templates, and increased patient discharges from clinic was responsible for 31%, 24%, and 10% reduction in wait times, respectively. These interventions also increased resident productivity, which resulted in the clinic seeing nearly 40% more new patients in the 3-year follow-up period. Also, a higher percentage of new patient referrals resulted in a completed clinic visit, as a result of the decreased wait times (Table I). Limitations include that this study is not generalizable to health systems without residents, lack of follow-up on outcomes of discharged patients, and patient satisfaction with clinic changes. Our findings suggest that targeted interventions in staffing and patient scheduling can decrease and maintain lower wait times, resulting in expedient access to dermatologic care in a safety net health system.

Table I.

Parkland dermatology clinic volumes

| Metric | FY 2011–2012 | FY 2012–2013 | FY 2013–2014 | FY 2014–2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dermatology clinic visits | 8030 | 8700 | 9358 | 9730 |

| New patient completed visits | 2438 | 2848 | 3125 | 3400 |

| Established patient visits | 5592 | 5852 | 6233 | 6330 |

| Patients discharged from clinic | 1832 | 2177 | 2208 | 1991 |

| Patients seen by physician assistant | N/A | N/A | 200 | 661 |

| Patients seen by residents | 8030 | 8700 | 9158 | 9069 |

| Residents per clinic | 7.67 | 7.75* | 8.00* | 8.00* |

| Nurses per clinic | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 3 |

| Attending physicians per clinic | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| Patients per resident per clinic | 7.17 | 7.64 | 7.79 | 7.71 |

FY, Fiscal year (October through September); N/A, not applicable.

The number of residents per clinic includes the resident assigned to perform biopsies for the clinic. The biopsy resident also saw patients between biopsies.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award K23AR061441 and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH under award TL1TR001104. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and its affiliated academic and health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources, or the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Barnett ML, Song Z, Landon BE. Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999–2009. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:163–170. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1459–1468. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine Committee on the Changing Market, Managed Care, and the Future Viability of Safety Net Providers. The core safety net and the safety net system. In: Lewin ME, Altman S, editors. America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. Washington (DC): National Academy Press (US); 2000. pp. 47–80. [Google Scholar]