Abstract

This study describes who pays for inpatient tuberculosis (TB) care and factors associated with payer source. The authors analyzed TB hospitalization costs for a prospective cohort of active TB patients at 10 U.S. sites. Private insurance paid for 9 percent and private hospitals for 6 percent of TB hospitalization costs. Public sources (federal, state, and local governments and public hospitals) paid more than 85 percent of TB hospitalization costs. Preventive services (treatment for latent TB infection; housing, food, and social work for homeless persons; substance abuse treatment for substance abusers; and antiretroviral medication for HIV-infected persons) targeted to those at high risk for TB hospitalization could save taxpayers between $4 million and $118 million. Since public resources are used to pay nearly all the costs of late-stage TB care, the public sector could save by shifting resources currently used for inpatient care to target preventive services to persons at high risk for TB hospitalization.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, homeless persons, housing, hospitalization, HIV, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, substance-related disorders, costs and cost analysis, primary health care, medically uninsured, prevention

A recent economic study, using a U.S. societal perspective, estimated that inpatient care accounts for approximately 60 percent of direct medical expenditures for tuberculosis (TB).1 In response to this finding, a second study was undertaken in 1995 to examine costs, payer information, and factors associated with TB hospitalizations for a cohort of U.S. TB patients. Results published from the latter study indicated that homeless HIV-infected persons, non-Hispanic blacks, and alcohol abusers were hospitalized more frequently than others for TB and that correctional facility residents, persons with multidrug resistant (MDR) disease, homeless persons without health insurance, long-term care residents, and alcohol abusers were hospitalized longer than other TB patients.2

These studies raise the following questions. Who pays for TB hospitalizations? Would it be cost beneficial for the public sector to shift resources it is currently using for hospitalization to target preventive services for persons at high risk for TB hospitalization? This study attempts to answer these questions.

Method

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted a prospective study of a cohort of active TB patients reported to CDC during a six-month period in 1995 or early 1996, examining their TB hospitalizations just prior to TB diagnosis and during their entire period of TB treatment. A detailed discussion of study methods is found in Taylor et al.3 Ten sites participated in the study: Chicago, IL; Dallas/Ft. Worth, TX; Georgia; Houston, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Mississippi; three counties surrounding New York City (counted as one site); San Diego, CA; San Francisco, CA; and South Carolina. The final cohort consisted of 1,493 persons, a convenience sample of 6.5 percent of all U.S. TB cases reported in 1995.

Hospitalization charges were obtained from standard hospital billing forms (UB-92 forms) or from other billing forms generated by the hospitals. These charges included room and board, medications, procedures, and some charges for hospital staff use. Physician charges were not included. Charges were converted to costs using Health Care Financing Administration cost-to-charge ratios specific to each hospital.4 Costs were further adjusted to a U.S. equivalent using the Cost of Living Index for Selected Metropolitan Areas5 and then converted to 1999 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for medical care.6

The number of patients, hospitalization episodes, days hospitalized, and costs were aggregated by government, private, or uninsured/unknown payer. Government payer included local, state, and federal (Medicare, Medicaid, both Medicare and Medicaid, or Veterans Administration) sources. Three separate multivariate logistic regression analyses, using backward selection, identified factors associated with having government, private, or no/unknown insurance. Public sector costs of TB care included those paid for by government sources directly and the costs of care for uninsured patients in public hospitals, which are indirectly paid by taxpayer dollars.

A spreadsheet model was used to calculate the direct and indirect costs of eliminating inpatient TB care for the following persons found to be at high risk for frequent or long TB hospitalization paid for by the public sector: people who are homeless, people who are HIV-positive, non-Hispanic blacks, substance abusers, correctional facility residents, MDR TB patients, long-term care residents, and uninsured persons cared for in public hospitals.2

Using data from the above study cohort, the number of high-risk hospitalized TB patients in the United States was estimated from the ratio of high-risk study patients to total U.S. TB patients, and total U.S. hospitalization costs for high-risk persons were estimated based on a range of days per patient and cost per patient per day of hospitalization procedures and medications. Physician costs were estimated using the number of hospitalization days from the study and the cost per day of care calculated from the Physicians Fee and Coding Guide.7 Indirect productivity losses due to hospitalization were estimated from the number of hospitalization days times daily wages calculated from average weekly earnings reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.8 Leisure time was valued at the same rate as work time, thus eliminating the need to distinguish between employed and unemployed TB patients in valuing productivity losses. A range of cost estimates is provided based on the first quartile, median, average, and third quartile distribution of days per patient; a similar range is provided for cost per patient per day.

Estimates of direct and indirect costs of eliminating hospitalization were compared with estimated costs of preventing TB hospitalization in high-risk persons. Preventing TB hospitalization is assumed to involve early diagnosis of TB disease and prevention of TB disease through targeted screening and treatment of TB disease and latent TB infection (LTBI). Cost estimates ($215 per person) of targeted screening and treatment in a high-risk population come from unpublished calculations using data from a U.S. study of contact investigations. Methods from that study are described in Marks et al.9 This cost estimate includes tuberculin skin tests, chest radiographs, sputum exams, the provision of nine months of isoniazid (INH) for contacts to patients having drug-susceptible disease or four months of rifampin for contacts to INH-resistant TB patients,10 treatment costs of INH-induced hepatitis,11 diagnosis and treatment of identified TB patients and suspects, and personnel costs associated with each exam or service. Also included in prevention estimates is the cost of nine months of twice weekly directly observed treatment (DOT) for all high-risk persons,12 nine months of housing13 and food14 and one day of social work services15 for homeless persons, nine months of outpatient substance abuse treatment for substance abusers,16 and nine months of anti-HIV medication along with monthly liver enzyme exams7 for HIV-infected persons. It is assumed that early treatment of identified TB disease will prevent TB hospitalization and that nine months of treatment for LTBI will prevent 93 percent of TB disease and all subsequent TB hospitalizations.

Results

Of the 1,493 TB patients in the study cohort, 733 individuals were hospitalized for TB just prior to diagnosis or during the period of their TB treatment.

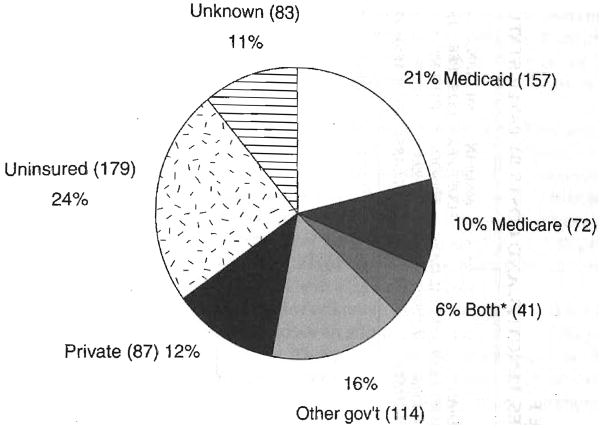

Figure 1 presents the distribution of insurance coverage for the 733 TB patients hospitalized for TB. Table 1 presents TB hospitalizations, lengths, and costs by payer status for the study cohort.

FIGURE 1. INSURANCE STATUS OF HOSPITALIZED TUBERCULOSIS PATIENTS.

*Covered by both Medicaid and Medicare.

TABLE 1.

TUBERCULOSIS (TB) HOSPITALIZATION EPISODES, LENGTHS, AND COSTS BY PAYER STATUS

| CHARACTERISTIC | HOSPITALIZED TB PATIENTS | TB HOSPITAL EPISODES | AVERAGE NUMBER OF HOSPITAL EPISODES PER PATIENT | MEDIAN HOSPITALIZATION LENGTH PER EPISODE (DAYS) | TOTAL DAYS HOSPITALIZED FOR TB | MEDIAN COST PER EPISODE (1999 DOLLARS) | MEDIAN COST PER PATIENT (1999 DOLLARS) | TB HOSPITAL COSTS (1999 DOLLARS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government payer | 384 | 441 | 1.15 | 13 | 10,378 | 8,972 | 9,754 | 6,376,568 |

| Percentage of total | 52 | 54 | 59 | 57 | ||||

| Private payer | 87 | 91 | 1.04 | 8 | 1,295 | 7,445 | 7,445 | 1,038,759 |

| Percentage of total | 12 | 11 | 7 | 9 | ||||

| Uninsured or unknown payer | 262 | 289 | 1.10 | 10 | 5,994 | 6,730 | 7,027 | 3,848,526 |

| Percentage of total | 36 | 35 | 34 | 34 | ||||

| Total | 733 | 821 | 1.12 | 11 | 17,667 | 8,767 | 7,810 | 11,263,853 |

Fifty-two percent of patients hospitalized for TB had government insurance coverage. Government insurance paid for most (57 percent) TB hospitalization costs. The greater hospitalization length (median 13 days, mean 24 days), cost per episode (median $8,972, mean $14,518), and average number of episodes per patient (1.15) resulted in disproportionately higher hospitalization costs for those insured by the government compared with others. Multivariate analysis found that those with government insurance were more likely to be HIV infected and less likely to be age 15 to 64 or of Hispanic ethnicity.

Thirty-six percent of those hospitalized were either uninsured (25 percent) or had unknown insurance status (11 percent). The median cost of hospitalizing a patient with no/unknown insurance was $7,027 (average $14,689). Care for these patients accounted for 34 percent of TB hospitalization costs in the study. In multivariate analysis, patients who were age 15 to 64, Hispanic, or homeless were more likely to be uninsured or have unknown insurance status than others. Homeless patients with no/unknown insurance (approximately half of homeless patients) had significantly longer hospitalizations than others, which resulted in greater costs.

Private insurance paid for only 9 percent of TB hospitalization costs, relative to its 12 percent share of patients. This is because both hospitalization length (median eight days) and average number of hospitalization episodes per patient (1.04) for privately insured patients were lower than for both the government-insured and no/unknown insurance status patients. In multivariate analysis, those having private insurance were more likely to be age 25 to 64. Those less likely to be privately insured were substance abusers, homeless patients, and HIV-infected patients.

Patients who had private insurance were significantly less likely (odds ratio [OR] = 0.5, 95 percent confidence interval [CI] = 0.3–0.7) to have been admitted through the emergency room (ER), while those of no/unknown insurance status were more likely (OR = 2.0,95 percent CI = 1.4–2.8) to enter through the ER. Non-Hispanic black patients were more likely to be admitted through the ER than patients from other race/ethnic groups (OR = 1.9,95 percent CI = 1.4–2.5). Almost three-quarters of non-Hispanic black patients were admitted through the ER, compared with 60 percent of other groups.

Eighty percent of patients with no/unknown insurance were cared for in public hospitals. Public sources paid for an additional 28 percent of TB hospitalization costs to cover this group. Thus, public sources paid more than 85 percent of TB hospitalization costs (57percent of costs paid directly by government sources plus 28 percent of costs to care for patients with no/unknown insurance in public hospitals). Private insurance paid for 9 percent and private hospitals paid the remaining 6 percent of TB hospitalization costs.

Table 2 presents the detailed calculations of direct and indirect costs of eliminating TB hospitalizations compared with the costs of targeted preventive services for the high-risk group of homeless persons, HIV-positive persons, non-Hispanic blacks, substance abusers, correctional facility residents, MDR TB patients, long-term care residents, and uninsured persons cared for in public hospitals currently paid for by the public sector. The benefits of eliminating TB hospitalization for this high-risk group include a low of $32 million, a median of $72 million, an average of $173 million, and a high of $187 million. Targeted prevention for the high-risk group is estimated to cost $68 million and includes (1) diagnosis and DOT of TB infection and disease; (2) housing, food, and social work services for homeless persons; (3) outpatient substance abuse treatment for substance abusers; and (4) anti-HIV medication and additional medical exams for HIV-infected persons. Net benefits to the public sector of targeted prevention services range from a net cost of $36 million at the low end of hospitalization costs to cost savings of $4 million, $105 million, and $119 million for the median, average, and high estimates of hospitalization costs, respectively.

TABLE 2.

NET BENEFITS TO U.S. TAXPAYERS OF ELIMINATING TUBERCULOSIS (TB) HOSPITALIZATIONS IN PERSONS AT HIGH RISK FOR TB HOSPITALIZATION

| DAYS/PATIENT |

COST/PATIENT/DAY (1999

DOLLARS) |

TOTAL U.S. COST (1999

DOLLARS) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STUDY PATIENTS | U.S. PATIENTSa | FIRST QUARTILE | MEDIAN | AVERAGE | THIRD QUARTILE | FIRST QUARTILE | MEDIAN | AVERAGE | THIRD QUARTILE | FIRST QUARTILE | MEDIAN | AVERAGE | THIRD QUARTILE | |

| Direct | ||||||||||||||

| Hospital procedures/medications | 490 | 7,538 | 7 | 13 | 27 | 25 | 489 | 623 | 736 | 877 | 25,802,574 | 61,050,262 | 149,795,136 | 165,270,650 |

| Physician | 490 | 7,538 | 7 | 13 | 27 | 25 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 1,108,086 | 2,057,874 | 4,274,046 | 3,957,450 |

| Total direct costs | 510 | 644 | 757 | 898 | 26,910,660 | 63,108,136 | 154,069,182 | 169,228,100 | ||||||

| Indirect | ||||||||||||||

| Productivity losses | 490 | 7,538 | 7 | 13 | 27 | 25 | 93.11 | 93.11 | 93.11 | 93.11 | 4,913,042 | 9,124,221 | 18,950,306 | 17,546,580 |

| Total indirect costs | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 4,913,042 | 9,124,221 | 18,950,306 | 17,546,580 | ||||||

| Total direct and indirect costs | 603 | 737 | 850 | 991 | 31,823,702 | 72,232,357 | 173,019,488 | 186,774,680 | ||||||

| Costs of preventing TB hospitalizations | ||||||||||||||

| Targeting testing and treatment for latent TB infectionb | 490 | 7,538 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2,035,260 | 2,035,26 | 2,035,260 | 2,035,260 |

| Housing/food/social worker for homelessc | 96 | 1,477 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 8,374,590 | 8,374,590 | 8,374,590 | 8,374,590 |

| Directly observed treatment two times a week for nine monthsd | 490 | 7,538 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 22,794,912 | 22,794,912 | 22,794,912 | 22,794,912 |

| Liver exams in HIV-positive patientse | 117 | 1,800 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 307,800 | 307,800 | 307,800 | 307,800 |

| Anti-AIDS medicationsf | 117 | 1,800 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 19,926,000 | 19,926,000 | 19,926,000 | 19,926,000 |

| Substance abuse treatmentg | 277 | 4,262 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14,959,620 | 14,959,620 | 14,959,620 | 14,959,620 |

| Total costs of prevention | 124 | 124 | 124 | 124 | 68,398,182 | 68,398,182 | 68,398,182 | 68,398,182 | ||||||

| Net benefits to U.S. taxpayers | 479 | 613 | 726 | 867 | (36,574,480) | 3,834,175 | 104,621,306 | 118,376,498 | ||||||

Note: This table shows the costs of eliminating TB hospitalizations in high-risk persons (homeless, HIV-positive, non-Hispanic blacks, substance abusers, correctional facility residents, multidrug resistant TB patients, or long-term care residents paid for by the public sector or uninsured in public hospitals).

Since the study patients represented 6.5 percent of U.S. TB patients, U.S. patients = study patients divided by 6.5 percent.

Costs of TB testing (tuberculin skin test [TST], follow-up TST, chest radiograph, sputum exam) and treatment for latent TB infection (nine months of isoniazid or four months of rifampin).

Nine months of housing (fair market rent for two bedroom $415 adjusted to 80 percent for an efficiency), food (U.S. Stat Abstract Table 760 liberal plan adjusted upward by 20 percent for a single male), and one day of $35,000 annual salary social worker.

Cost of directly observed treatment.

Nine monthly liver enzyme exams.

Nine months of anti-AIDS medications at $15,000 per year, estimate.

Nine months of outpatient substance abuse treatment.

The demographics of this 1995 study cohort were somewhat more representative of an urban population than of all U.S. TB patients. Participants were more likely to be black (42 percent vs. 33 percent) or Hispanic (24 percent vs. 21 percent) and less likely to be white (15 percent vs. 27 percent). However, TB is becoming more of a metropolitan urban disease and less of a rural one, with three-fourths of TB cases reported from metropolitan statistical areas with more than 500,000 people.

The cost-benefit analysis includes hospitalization costs over the period of TB treatment, which generally lasts from six to nine months, and targeted preventive services for nine months. While the benefits of some targeted preventive services, such as treatment for LTBI (in greatly reducing the risk of TB disease) and of DOT (in decreasing the risk of MDR TB), are long-lasting, others, such as HIV antiretrovirals and housing, need to be continued past the nine month time frame for benefits to continue.

Discussion

Taxpayer dollars paid for nearly all (85 percent) TB hospitalization costs since patients were covered by Medicaid, Medicare, Veterans Administration, state, or local government sources or because uninsured patients were cared for in public hospitals. A comparison of the benefits to be derived by the public sector in eliminating inpatient TB care with the costs of targeted preventive services for persons at high risk for TB hospitalization who would likely be paid for by taxpayer dollars shows that targeted preventive services save $4 million at the median, $105 million on average, and $119 million at the high end of hospitalization cost estimates. Since public resources are used to pay nearly all the high costs of late-stage TB care, it would save taxpayer dollars to shift resources the public sector is currently using for hospitalization to target preventive services to persons at high risk for TB hospitalization.

The benefits of eliminating TB hospitalization by targeted preventive services are likely to be understated. Additional benefits over an extended analytic horizon may include reductions in non-TB hospitalizations, especially for the homeless and for HIV-infected persons who are provided with housing (and possibly links to jobs and permanent housing through the social worker) and other needed medical and social services. Because of access to anti-retroviral medications, HIV-infected persons may have a reduced incidence of opportunistic infections (other than TB), reduced outpatient medical costs, and an increased survival rate. Because of placement of this high-risk group on DOT, the incidence of MDR TB in this population may decline. Treatment for substance abuse may have various long-term medical and social benefits. Prevention and early diagnosis of TB may avoid chronic lung and other permanent medical conditions that are sequelae of TB. Although this study used data based on a nine-month INH treatment for LTBI, recently recommended shorter TB regimens17 may provide greater benefits at lower costs in some populations.

Federal, state, and local governments may save taxpayer dollars by targeting preventive services to persons at high risk for TB hospitalization. Diagnostic and treatment services for TB infection and disease could be provided at HIV clinics, long-term care institutions, jails and prisons, drug treatment centers, and places where homeless individuals congregate. Similar services need to be provided, as demonstrated by high ER use, to non-Hispanic blacks and those lacking health insurance. Linking high-risk persons to housing, substance abuse treatment, and antiretroviral medication may have long-term benefits beyond the scope of this study.

References

- 1.Brown RE, Miller B, Taylor WR, et al. Health-care expenditures for tuberculosis in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1995 Aug 7–21;155(15):1595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks SM, Taylor Z, Ríos Burrows NR, et al. Hospitalization of homeless persons with tuberculosis. Am J Public Health. 2000 Mar;90(3):435–38. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor Z, Marks SM, Ríos Burrows NM, et al. Causes and costs of hospitalization of tuberculosis patients in the United States. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000 Oct;4(10):931–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Health Care Financing Administration. Provider-specific cost to charge ratios. 1996 Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cost of living index. 116. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 1996. Statistical abstract of the United States: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price annual indices, medical care. Retrieved from http://stats.bls.gov.

- 7.1997 physicians fee and coding guide: A comprehensive fee and coding reference. Augusta, GA: Health Care Consultants of America; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Average hourly and weekly earnings. 116. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 1996. Statistical abstract of the United States: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks SM, Taylor Z, Qualls NL, et al. Outcomes of contact investigations of infectious tuberculosis patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Dec;162(6):2033–38. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2004022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.1996 drug topics red book. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salpeter SR, Sanders GD, Salpeter EE, et al. Monitored isoniazid prophylaxis for low-risk tuberculin reactors older than 35 years of age: A risk-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Dec 15;127(12):1051–61. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burman WJ, Dalton CB, Cohn DL, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of directly observed therapy vs. self-administered therapy for treatment of tuberculosis. Chest. 1997 Jul;112(1):63–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fair market rents, an efficiency apartment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weekly food cost. 116. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 1996. Statistical abstract of the United States: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Association of Social Workers. Median salary. Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.French MT, McGeary KA. Estimating the economic cost of substance abuse treatment. Health Econ. 1997 Sep-Oct;6(5):539–44. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199709)6:5<539::aid-hec295>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Mor Mortal Wkly Rpt. 2000 Jun;49(RR-6) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]