Abstract

Our collaborative care intervention for the perceived unmet care needs of women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy after surgery was feasible. The preliminary results suggest the program was effective.

Keywords: breast cancer, needs, problem solving, clinical trial

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the feasibility of an intervention program for women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant anticancer therapy, and determine its preliminary effectiveness in reducing their unmet needs and psychological distress.

Methods

The intervention was based on the collaborative care model, and compromised four domains: identification of unmet needs, problem-solving therapy and behavioral activation supervised by a psychiatrist, psychoeducation and referral to relevant departments. Eligible women with breast cancer were provided the collaborative care intervention over four sessions. The feasibility of the program was evaluated by the percentage of women who entered the intervention and by the percentage of adherence to the program. Self-reported outcomes were measured by the Supportive Care Needs Survey–Short Form 34 (SCNS-SF34), the Profile of Mood States (POMS), the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), the Concern about Recurrence Scale, and pre- and post-intervention satisfaction with medical care.

Results

In total, 40 patients participated in this study. The rate of participation in the intervention was 68%, and the rate of adherence was 93%. Participants had significantly improved scores on total perceived needs, physical needs and psychological needs on the SCNS-SF34; vigor and confusion on the POMS and function (physical, emotional and cognitive), nausea and vomiting, dyspnea, appetite loss and financial difficulties on the EORTC QLQ-C30 compared with the baseline assessment.

Conclusions

Our findings indicated the intervention program was feasible. Further study is needed to demonstrate the program's effectiveness in reducing unmet needs.

Introduction

In Japan, the mortality and prevalence rates of breast cancer have increased over the last 30 years. At present, ~72 000 women develop breast cancer annually in Japan. Advances in individualized and multimodal treatments have improved the survival of patients with breast cancer and increased the number of people living with cancer. In the context of a growing population of cancer survivors, it is critical to understand the impact of patients’ unmet care needs as well as their psychological distress and quality of life (QOL) (1). Assessment of unmet care needs provides a direct indicator of the help required by patients with cancer. Previous studies on unmet needs of patients with breast cancer reported that 40–45% of patients perceived a moderate/high unmet need for help, with the most prevalent unmet needs being psychological and informational, physical and daily living (2,3). The perceived unmet needs of patients with cancer are also associated with poor psychological outcomes (e.g. depression and anxiety) and low QOL (4). Hence, needs assessment enables individuals and/or patient subgroups with higher need levels to be identified, and allows increased QOL or reduction of psychological outcomes through appropriate early intervention (2).

However, previous studies related to unmet needs for patients with cancer have not found interventions to be effective in reducing the unmet needs for help (2,5,6). These negative results might be explained by a lack of choice in the level of unmet needs the participants experienced. Armes et al. reported that 40% of patients receiving treatment following cancer diagnosis had no unmet needs at the end of treatment (7). Selection of appropriate cancer patients, namely those with unmet needs, is important to determine the effectiveness of an intervention. Another reason may be that the interventions were too brief to improve unmet needs. Previous interventions intended to reduce the unmet needs of patients with cancer included feedback to their oncologist or general practitioner (5), care coordination (6) and telephone counseling conducted by a nurse (2). However, these simple and/or brief interventions did not demonstrate effectiveness for patients with cancer.

Therefore, the development of more comprehensive, integrated interdisciplinary interventions may be needed to improve the unmet needs of patients with cancer. Collaborative care is a model developed for people with depression in primary care that aims to improve their lives by enhancing the whole process of care needs (8). The model uses a multifaceted approach including systematic identification of patients, active follow-up by a case manager, and specialist supervision as key components of managing depressive symptoms (9). Research has shown that collaborative care resulted in a significant reduction in the distress symptoms caused by depression (10,11). Considering the applicability of interventions in cancer clinical settings, collaborative care may be a promising strategy for breast cancer survivors undergoing adjuvant therapy.

The purpose of this study was: (1) to investigate the feasibility of an intervention program based on collaborative care for women with breast cancer who received adjuvant therapy after surgery; (2) to examine its preliminary usefulness in reducing perceived needs for help (primary outcome); and (3) to examine the preliminary usefulness in reducing psychological distress and threat for cancer recurrence, and improving QOL (secondary outcomes).

Methods

Participants

Participants were ambulatory female patients with breast cancer who attended the outpatient clinic of Nagoya City University Hospital. Potential participants were consecutively sampled.

Inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) a histological diagnosis of invasive breast cancer; (2) an age of 20 years or older; (3) 3–6 months after breast surgery; (4) received adjuvant chemotherapy or hormone therapy after surgery; (5) currently disease-free; (6) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status Scale score of 2 or less; and (7) suffering from psychological distress (positive screening result using the Distress and Impact Thermometer; namely 3 points or above on the Distress Thermometer and/or 1 point or above on the Impact Thermometer). Exclusion criteria were: (1) severe functional impairment that may impact on participation in the interview or questionnaire or serious cognitive disorder (i.e. delirium or dementia); and (2) inability to speak and write in the Japanese language.

The sample size was based on a power analysis conducted for the total SCNS-SF34 score as the primary outcome. With 0.8 power to detect a significant difference in this primary outcome compared with baseline assessment, a two-sided type I error of 5%, and an effect size of 0.5, a required sample size of 34 participants was calculated. Therefore, allowing for six drop outs, this study required 40 patients to be recruited.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Japan, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Written consent was obtained from each patient after provision of a thorough explanation of the purpose and method of the study.

Procedures

After written consent was obtained from all eligible patients, they were asked to complete self-report questionnaires at home, and return completed questionnaires by mail (T1). All patients completed the same questionnaires 1 week after the intervention, as a preliminary measure of the intervention's effectiveness (T2).

Intervention

The content of the intervention was developed based on a collaborative care model provided to people with depression in Western countries (11–13). This included assessment of patients’ perceived unmet needs, structured brief psychotherapy and psychoeducation with supervision by a trained psycho-oncologist, and feedback of patients’ unmet needs or identified problems to the medical oncologist as needed. The medical oncologist then addressed the unmet needs or problems identified for treatment or testing in the usual clinical setting, and made referrals to a psychiatrist or medical social worker as necessary. Participants were provided the intervention over four sessions by a trained nurse (Table 1).

Table 1.

Components of the need-based intervention

| Session | Style | Time | Componentsa | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interview during the hospital visit | 90 min | Introduction | Explanation about the purpose and methods of the intervention and establishing a confidential relationship. |

| Identification of patients’ unmet needs | Recognizing patients’ unmet needs based on review of the SCNS-SF34b. Their highest unmet needs were discussed in problem-solving therapy. | |||

| Problem-solving therapy | Introducing the purpose and methods of problem-solving treatment, identifying patients’ problems, and setting goals using a worksheet. | |||

| Behavioral activation | Introducing activity scheduling and encouraging behavioral activation. | |||

| Psychoeducation | Provision of a booklet containing useful information such as self-care for adverse events of anti-cancer treatment, psychological impact of cancer and its treatment, and available social resources. | |||

| 2 | Interview during the hospital visit | 60 min | Problem-solving therapy | Brainstorming about strategies to resolve the problems and develop a concrete plan for problem resolution. |

| Behavioral activation | Identifying the activities to achieve a better feeling by reviewing their activity scheduling sheet, and discussing the plan to include these activities in their life. | |||

| 3 | Telephone interview | 30 min | Problem-solving therapy | Continue to learn and master problem-solving therapy. |

| 4 | Telephone interview | 30 min | Problem-solving therapy | Continue to learn and master problem-solving therapy. |

| Termination | Reviewing the previous sessions and managing anxiety about termination of the intervention (as needed). |

aAfter completion, each session was reviewed and supervised by a psycho-oncologist.

bSupportive Care Needs Survey–Short Form.

Before the intervention, the trained nurse recognized participants’ unmet needs based on their responses to the baseline questionnaire. Any responses marked ‘high need’ or ‘moderate need’ were listed, and discussed in terms of the impact on daily life and resolution priority. These were also identified as problems in psychotherapy.

Problem-solving therapy (PST) (14) and behavioral activation therapy (BAT) (15,16) were used to resolve the problems experienced in daily life by patients with breast cancer after diagnosis. These structured, brief psychotherapy interventions and the associated materials were modified and condensed for the present study as part of our previous study (17). In addition to being effective for mental health disorders (13), PST is acceptable to patients and can be delivered by non-mental health specialists. The goals of PST were to: (1) increase the patient's understanding of the association between their symptoms and their everyday problems, (2) increase the patient's skill in identifying their problems and setting concrete goals, (3) educate patients about the PST procedure so they can reframe their problems and solve them by themselves, and (4) give patients a more positive experience of their ability to solve their problems (14). In this study, PST comprised four structured components and steps: identifying and defining the problem, setting goals, brainstorming about strategies to resolve the problem and developing a concrete plan for problem resolution. After participants learned about the means of resolving problems using a worksheet, they were facilitated to apply PST to other problems to reinforce the skills for resolving problems learned in the intervention. BAT is also a brief intervention, and was designed to help patients with anxiety or depression increase the frequency of active behaviors and pleasure that they experience in their daily life (15,16). PST focuses on the ‘here and now,’ but many survivors of breast cancer have concerns about the recurrence of cancer (18); that is, concern for the future. Therefore, provision of an intervention including both PST and BAT is likely to help resolve patients’ problems in a more efficient way. For the BAT, participants were encouraged to complete an activity scheduling sheet to learn to recognize feelings with activities in the first session, and were recommended to engage in pleasurable activities on a frequent basis by reviewing the sheet in the second session.

Psychoeducation was offered via a booklet developed for this study that included useful information about unmet needs. The content included elements such as self-care for adverse events associated with anti-cancer treatment to assist with physical and daily living needs, psychological coping techniques for the impact of cancer and its treatment, available social resources for sexuality or patient care and support needs.

The intervention was provided over four sessions. The first session was face-to-face and lasted ~1.5 h. After baseline assessment, the most important unmet needs were identified, and participants were introduced to the purpose of PST and behavioral activation. The second session, conducted after a 2–4-week interval, was also face-to-face and lasted ~1 h. In the second session, strategies for resolving the problems were discussed and a resolution plan was selected. The third and fourth sessions were conducted over the telephone at a 2–3-week interval from the previous session. Each session was reviewed and supervised by a trained psycho-oncologist (TA). One trained nurse provided the intervention. The nurse had no experience of psychiatry or PST (but did have experience of oncology) and was trained to deliver the intervention (especially PST) using role-play training by trained psycho-oncologists and psychologists.

Outcome measures

Feasibility

The feasibility of the intervention program was evaluated by the percentage of participants who entered the intervention and by adherence to the program. We defined a participation rate of 50% or more as feasible. Adherence to the intervention program was defined by the proportion of participants who completed the post-intervention questionnaires (T2). We defined a post-intervention completion rate of 80% or more as indicating good feasibility.

Supportive Care Needs Survey–Short Form 34 (SCNS-SF34)

The SCNS-SF34 is a self-administered instrument designed to assess the perceived needs of patients with cancer (19). The SCNS-SF34 comprises 34 items covering five domains of need: psychological (10 items), health system and information (11 items), physical and daily living (5 items), patient care and support (5 items), and sexuality (3 items). Participants were asked to indicate their level of need for help over the last month related to having cancer, using five response options: 1 = No Need (Not applicable), 2 = No Need (Satisfied), 3 = Low Need, 4 = Moderate Need, and 5 = High Need. Subscale scores were obtained by summing the individual items for each subscale. A total score was obtained by summing the subscale scores (range, 34–170). A high score indicated higher perceived need. The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the SCNS-SF34 has been established (20).

Psychological distress

To preliminarily evaluate the effectiveness of this intervention program, we used the Profile of Mood States (POMS) and the Japanese version of the Concern about Recurrence Scale (CARS-J).

The POMS is a 65-item self-rating scale measuring mood disturbance and is a widely used, reliable measure of emotional distress (21). The POMS has subscales for anxiety, depression, vigor, fatigue and confusion. In addition, a score for total mood disturbance is obtained by summing the subscale scores. Participants rated each item on a four-point scale (where a high score indicated a higher negative mood, with the exception of vigor, where a higher score indicated positive mood). The POMS has been validated in patients with cancer and demonstrated to be reliable for Japanese people (22).

We measured the threat of breast cancer recurrence using the CARS-J, a 26-item self-report scale originally developed in the United States (23). The CARS-J has subscales covering the impact of threat, threat of health and death, womanhood, self-value and role. In this study, we only used the impact of threat subscale. A higher score indicates a higher threat of recurrence of breast cancer. The reliability and validity of the CARS-J has been previously demonstrated (24).

QOL

Participants’ QOL was assessed using the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) (25). This is a 30-item self-report questionnaire covering functional (global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning) and symptom-related aspects (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties) of QOL for patients with cancer. The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 have been confirmed (26). A high functional score represents high QOL. A high symptom score indicates strong symptoms.

Satisfaction with medical care

We included one item on to capture changes in satisfaction with pre- and post-intervention medical care reported by participating women with breast cancer. The item was scored on a 10-point scale (response options ranged from 1 = Not at all to 10 = Very satisfied).

Sociodemographic and biomedical factors

An ad hoc self-administered questionnaire was used to obtain information on participants’ sociodemographic status, including marital status, level of education, and employment status. Performance status, as defined by the ECOG, was evaluated by the attending physicians. All other medical information (duration since diagnosis, clinical stage and anti-cancer treatment) was obtained from participants’ medical records.

Statistical analysis

To test the preliminary usefulness of the intervention program, a paired T-test was conducted to investigate differences between baseline assessment (T1) and post-intervention (T2). A P value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant; all reported P values are two-tailed. We also evaluated the effect size (ES) to assess the strength of the intervention using Cohen's d (27). ES was calculated as (mean for T2 − mean for T1)/pooled standard deviations (SD); where pooled SDs were calculated as the square root of (SD (T2)2 + SD (T1)2/2). Cohen's d of 0.2–0.3 is regarded as a small effect, ~0.5 as a medium effect, and greater than 0.8 as a large effect.

All statistical procedures were performed with SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0J (SPSS Inc).

The present study is registered at University hospital Medical Information Network – Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN-CTR, identifier: UMIN000001108).

Results

Participant characteristics

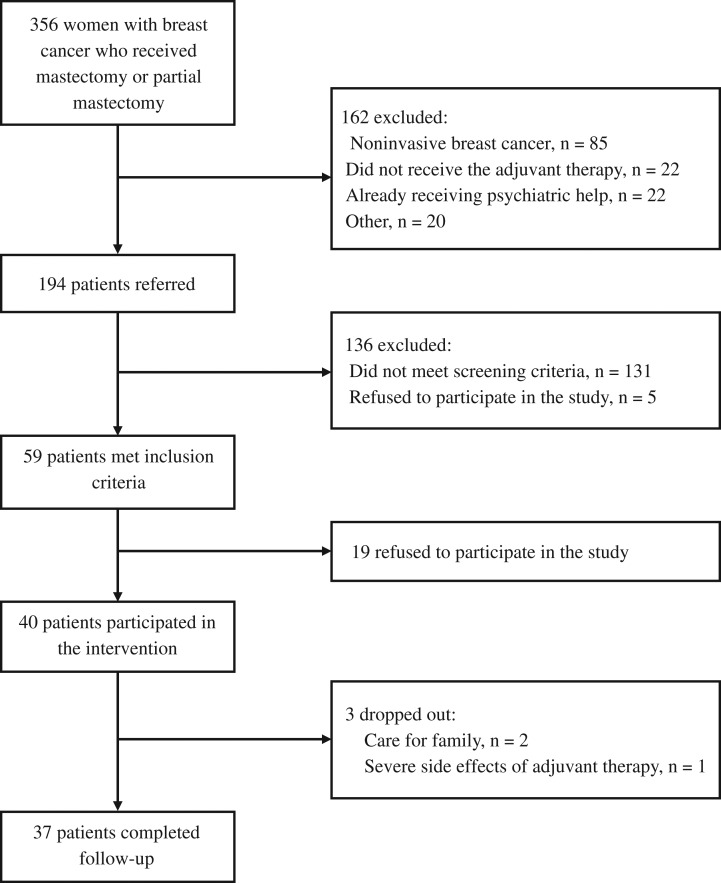

In total, 356 patients were assessed for potential eligibility, and 194 were asked to undergo screening for distress (Fig. 1). Finally, 59 patients met the inclusion criteria and 40 patients consented to participate in the intervention. Table 2 summarizes participants’ sociodemographic and clinical factors at baseline.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study sample.

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics (n = 37)

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55 (11) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| ≤High school | 21 (57) |

| >Some college or university | 16 (43) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Full-time | 5 (13) |

| Part-time | 4 (11) |

| Unemployed | 28 (76) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 29 (78) |

| Divorced/widowed | 6 (16) |

| Single | 2 (6) |

| Disease stage, n (%) | |

| 0 | 2 (5) |

| I | 17 (46) |

| II | 16 (44) |

| III | 2 (5) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |

| Mastectomy | 11 (30) |

| Partial mastectomy | 26 (70) |

| Lymph node resection, n (%) | |

| Presence | 12 (32) |

| Anticancer treatment, n (%) | |

| Chemotherapy (undergone) | 28 (76) |

| Trastuzumab (undergone) | 4 (11) |

| Hormonal therapy (undergone) | 22 (60) |

| Distress and impact thermometer | |

| Distress, mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.4) |

| Impact, mean (SD) | 3.6 (2.1) |

| Performance statusa, n (%) | |

| 0 | 37 (100) |

SD, standard deviation.

aEastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

Of the 40 patients who consented to participate, 37 completed the T2 follow-up. The reasons for dropout (n = 3) from the study were: care for their family (n = 2) and side effects of treatment (n = 1).

Feasibility

The participation rate in the intervention was 68% (40/59), and the rate of adherence to the intervention program was 93% (37/40). The average times taken for the intervention were 132 min (±29 min) for the interview sessions (Sessions 1 and 2) and 64 min (±22 min) for the telephone sessions (Sessions 3 and 4). Most participants reported that they were satisfied with the intervention, with the mean satisfaction score being 8.0 ± 1.5 (response options ranged from 1 = Not at all to 10 = Very satisfied).

Usefulness of supportive care needs, psychological distress and QOL

The changes in SCNS-SF34, POMS, CARS-J, EORTC QLQ-C30 and satisfaction with medical care scores for those who completed follow-up are shown in Table 3. The mean total SCNS-SF34 score showed a significant decrease post-intervention from pre-intervention (pre 90.9 ± 18.5 vs. post 77.3 ± 22.6, t = 3.614, P < 0.01, ES = 0.59). For the SCNS-SF34 subscales, physical and psychological needs were significantly improved after the intervention (P < 0.01, ES = 0.75 and P < 0.01, ES = 0.56, respectively), whereas care needs, information needs and sexual needs showed no statistically significant change.

Table 3.

Mean pre- and post-intervention scores for all study outcomes

| Outcome | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | P value | d (Effect size) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| SCNSa | ||||||

| Physical | 13.5 | 3.3 | 10.6 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.75 |

| Psychological | 29.8 | 7.4 | 24.6 | 8.1 | 0 | 0.56 |

| Patient care | 11.6 | 3.8 | 10.8 | 3.6 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| Information | 31.2 | 8.6 | 26.7 | 10.2 | 0.16 | 0.42 |

| Sexuality | 4.9 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.24 |

| Total need | 90.9 | 18.5 | 77.3 | 22.6 | 0 | 0.59 |

| POMSb | ||||||

| Vigor | 6.4 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 5.3 | 0.01 | 0.49 |

| Depression | 11.9 | 7.6 | 10.3 | 9 | 0.3 | 0.17 |

| Anger/Hostility | 6.6 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 0.64 | 0.06 |

| Fatigue | 10.9 | 5.7 | 9.2 | 6 | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| Tension/Anxiety | 9.3 | 4.4 | 9.1 | 5.9 | 0.83 | 0.03 |

| Confusion | 9 | 3.8 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 0 | 0.49 |

| Total mood disturbance | 41.4 | 25 | 33.3 | 29.8 | 0.1 | 0.29 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30c | ||||||

| Global health status | 50.2 | 18.3 | 54.3 | 20.1 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

| Physical functioning | 75 | 15.4 | 79.6 | 15.5 | 0.03 | 0.37 |

| Role functioning | 64.9 | 22.8 | 73.4 | 25.6 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| Emotional functioning | 71 | 15.3 | 76.8 | 18.1 | 0.04 | 0.35 |

| Cognitive functioning | 65.8 | 22.2 | 75.2 | 17.8 | 0 | 0.54 |

| Social functioning | 66.7 | 22.6 | 76.1 | 22.4 | 0.01 | 0.49 |

| Fatigue | 45.9 | 21.9 | 42 | 19.3 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 11.7 | 15.6 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 0 | 0.71 |

| Pain | 33.8 | 21.3 | 32 | 25 | 0.64 | 0.08 |

| Dyspnea | 27.9 | 27.8 | 18.9 | 23 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| Insomnia | 36.9 | 23.3 | 29.7 | 27 | 0.15 | 0.24 |

| Appetite loss | 21.6 | 25.1 | 13.5 | 20 | 0.05 | 0.34 |

| Constipation | 23.4 | 23.4 | 18.9 | 24.3 | 0.28 | 0.18 |

| Diarrhea | 9.9 | 15.4 | 7.2 | 13.9 | 0.37 | 0.15 |

| Financial difficulties | 38.7 | 28.9 | 24.3 | 29 | 0 | 0.67 |

| CARS-Jd | 16.2 | 5.3 | 15.6 | 5.3 | 0.44 | 0.15 |

| Satisfaction | 7.7 | 1.3 | 8 | 1.4 | 0.14 | 0.24 |

aSupportive Care Needs Survey–Short Form.

bProfile of Mood States.

cEuropean Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire.

dConcerns about Recurrence Scale, Japanese version.

There were no statistically significant changes in POMS scores for psychological distress after the intervention, with the exception of the vigor and confusion subscales that showed significant improvement after the intervention. There was no statistically significant change in fear of recurrence as measured by the CARS-J after the intervention. In addition, there were no statistically significant changes in the total global QOL index, although physical function, role function, emotional function, cognitive function and social function showed statistically significantly improvement. Satisfaction with medical care did not show a statistically significant change from pre- to post-intervention.

Discussion

This single-arm intervention study demonstrated that a novel intervention based on the collaborative care model and focused on perceived unmet needs of women with breast cancer resulted in a good participation rate and a high adherence to the program. The participation rates of previous intervention studies to relieve the distress of patients with breast cancer after cancer diagnosis ranged from 34% to 90% (28–31), although the participation rate was below half in many studies. Our participation rate was better than that in a previous study in Japan, where 35% of patients with breast cancer participated in group psychotherapy (32). In addition, the adherence rate in our program was good, which suggests the program has high clinical applicability. Our results indicate that the present intervention program is feasible for patients with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy.

A possible reason for the good participation rate in our study was the initial screening for the level of psychological distress. The most common reason for those who refused to participate was ‘not interested’ (33). Selecting patients with breast cancer with unmet needs using a screening method may lead to a better participation rate. Another possible reason for our participation rate was the schedule of the intervention. The time taken per session and number of intervention sessions in our study was likely to acceptable to patients with breast cancer. In addition, the face-to-face intervention sessions were provided within participants’ clinical visits, and two of the four sessions were administered by telephone and did not require additional clinic visits.

Our findings supported the preliminary usefulness of our collaborative care intervention, in which nurses provided brief psychotherapy, psychoeducation and care management under the supervision of a psycho-oncologist. This might have contributed to improving the total unmet needs as well as the physical and psychological unmet needs of patients with breast cancer. However, improvement in participants’ unmet needs in terms of patient care, information, and sexuality did not reach statistical significance, despite a tendency toward overall improvement. In this study, we used PST as psychotherapy to support coping with stress in women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy after surgery. Previous studies on PST for patients with cancer used differing numbers of PST sessions. Allen et al. used six PST sessions but did not show a significant effect on psychological distress (28). However, Nezu et al. found that PST was effective for the distress of patients with cancer after 10 sessions (34). We used four sessions, two interview-based sessions and two telephone sessions, to align with the usual clinical setting. PST might also be too brief to improve participants’ unmet needs for information, sexuality, and patient care, and additional sessions or individualized sessions might be required for those who have high needs in these areas.

Another possible reason for the non-significant improvement in the unmet patient care, information, and sexuality needs of patients with breast cancer may, in part, have been the competence of the therapist. Although the nurse did not have experience of providing PST for patients with breast cancer, she had sufficient training and time to conduct the psychotherapy. In addition, we believe that the nurse's competence in PST was supplemented and supported by supervision from a psycho-oncologist. In a future trial, we need to consider the competence of therapy providers.

Our analysis of effect size showed modest effectiveness after the intervention. As the intervention was feasible and brief, this suggests that the intervention was substantially effective in improving the unmet needs of patients with breast cancer.

As secondary outcomes, QOL, psychological distress, and threat of recurrence showed partial improvement following the collaborative care intervention. However, although a common problem identified by patients with breast cancer in the PST session was ‘threat of recurrence,’ this is a difficult problem to address. A correlation between threat of recurrence of cancer and problem-solving skills has been reported in a previous study (35). This suggests there is a need to consider additional PST sessions to develop better problem-solving skills in a future trial.

Our intervention was based on the collaborative care model, and included distress screening, psychological intervention provided by a nurse, and close collaboration with mental health professionals and medical oncologists. The intervention showed a statistically significant and moderate effect size. Therefore, as a brief and useful intervention, it may contribute to improving the unmet needs of patients with breast cancer in clinical practice.

The present study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted in one institution. Institutional bias may therefore be a problem and the generalizability of the findings might be limited. Second, because the intervention had a multicomponent structure, we could not determine the specific effect and/or effectiveness of each intervention component. Third, the study lacked a control group, making it difficult to present the actual usefulness of the program. Finally, the scale used to measure satisfaction with medical care has not yet been adequately validated.

Although the study has some limitations, the results suggest that it is a feasible intervention program that incorporates the collaborative care model. Our intervention may be effective in improving the unmet needs of patients with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy. The usefulness of the intervention needs to be confirmed in a future well-designed randomized controlled trial.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Rumiko Yamashita, RN, who helped as a research assistant.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Bonevski B, Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Burton L, Cook P, Boyes A. Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer 2000;88:217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Girgis A, Breen S, Stacey F, Lecathelinais C. Impact of two supportive care interventions on anxiety, depression, quality of life, and unmet needs in patients with nonlocalized breast and colorectal cancers. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyes A, Girgis A, D'Este C, et al. Prevalence and correlates of cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 6 months after diagnosis: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 2012;12:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akechi T, Okuyama T, Endo C, et al. Patient's perceived need and psychological distress and/or quality of life in ambulatory breast cancer patients in Japan. Psychooncology 2011;20:497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyes A, Newell S, Girgis A, et al. Does routine assessment and real-time feedback improve cancer patients’ psychosocial well-being. Eur J Cancer Care 2006;15:163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McLachlan SA, Allenby A, Matthews J, et al. Randomized trial of coordinated psychosocial interventions based on patient self-assessments versus standard care to improve the psychosocial functioning of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:4117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, et al. Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Von Knorff M, Goldberg D. Improving outcomes in depression. BMJ 2001;323:948–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, et al. Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:484–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2611–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. IMPACT Investigators. Improving mood-promoting access to collaborative treatment: collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2836–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aranda S, Schofield P, Weih L, et al. Meeting the support and information needs of women with advanced breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 2006;95:667–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Day A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of problem solving treatment, antidepressant medication, and combined treatment for major depression in primary care. BMJ 2000;320:26–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mynors-Wallis L. Problem-solving Treatment for Anxiety and Depression: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Bell JL. Behavioral activation treatment for cancer (BAT-C) A Cancer Patient's Guide to Overcoming Depression and Anxiety: Getting Through Treatment and Getting Back to Your Life. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, 2007;81–138. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hopko DR, Armento ME, Robertson SM, et al. Brief behavioral activation and problem-solving therapy for depressed breast cancer patients: randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:834–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akechi T, Hirai K, Motooka H, et al. Problem-solving therapy for psychological distress in Japanese cancer patients: preliminary clinical experience from psychiatric consultations. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2008;38:867–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joint Study Group on the Sociology of Cancer The views of 7885 people who faced up to cancer: towards the creation of a database of patients’ anxieties. A report on research into the anxieties and burdens of cancer suffers from Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2004;28–30.

- 19. Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract 2009;15:602–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okuyama T, Akechi T, Yamashita H, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire (SCNS-SF34-J). Psychooncology 2009;18:1003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McNair D, Lorr A, Droppleman L. Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yokoyama K, Araki S, Kawakami N, et al. Production of the Japanese edition of profile of mood states (POMS): assessment of reliability and validity. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 1990;37:913–18. (In Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vickberg SM. The concerns about recurrence scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women's fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med 2003;25:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Momino K, Akechi T, Yamashita T, et al. Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS-J). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2014;44:456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kobayashi K, Takeda F, Teramukai S, et al. A crossvalidation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQC30) for Japanese with lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 1998;34:810–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen J. Statistical Analisys in the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc. Inc, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Allen SM, Shah AC, Nezu AM, et al. A problem-solving approach to stress reduction among younger women with breast carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2002;94:3089–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Doorenbos A, Given B, Given C, et al. Reducing symptom limitations: a cognitive behavioral intervention randomized trial. Psychooncology 2005;147:574–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kimman ML, Dirksen CD, Voogd AC, et al. Nurse-led telephone follow-up and an educational group programme after breast cancer treatment: results of a 2 × 2 randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:1027–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stagl JM, Bouchard LC, Lechner SC, et al. Long-term psychological benefits of cognitive-behavioral stress management for women with breast cancer: 11-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2015;121:1873–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fukui S, Kugaya A, Kamiya M, et al. Participation in psychosocial group intervention among Japanese women with primary breast cancer and its associated factors. Psychooncology 2001;10:419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Given C, Given B, Rahbar M, et al. Effect of a cognitive behavioral intervention on reducing symptom severity during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:507–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nezu A, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, et al. Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:1036–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Akechi T, Momino K, Yamashita T, et al. Contribution of problem-solving skills to fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;145:205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]