Abstract

Background

There is a lack of instruments and studies written in Spanish evaluating physical fitness, impeding the determination of the current status of this important health indicator in the Latin population, especially in Colombia. The aim of the study was two-fold: to examine the validity of the International Fitness Scale (IFIS) with a population-based sample of schoolchildren from Bogota, Colombia and to examine the reliability of the IFIS with children and adolescents from Engativa, Colombia.

Methods

The sample comprised 1,873 Colombian youths (54.5% girls) aged 9–17.9 years. We measured their adiposity markers (waist-to-height ratio, skinfold thickness, percentage of body fat and body mass index), blood pressure, lipids profile, fasting glucose, and physical fitness level (self-reported and measured). A validated cardiometabolic risk index score was also used. An age- and sex-matched subsample of 229 schoolchildren who were not originally included in the sample completed the IFIS twice for reliability purposes.

Results

Our data suggest that both measured and self-reported overall physical fitness levels were inversely associated with percentage of body fat indicators and the cardiometabolic risk index score. Overall, schoolchildren who self-reported “good” or “very good” fitness had better measured fitness levels than those who reported “very poor/poor” fitness (all p < 0.001). The test-retest reliability of the IFIS items was also good, with an average weighted kappa of 0.811.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that self-reported fitness, as assessed by the IFIS, is a valid, reliable, and health-related measure. Furthermore, it can be a good alternative for future use in large studies with Latin schoolchildren from Colombia.

Keywords: Child, Physical fitness, Surveys and questionnaires, Risk factors, Self-report

Introduction

Physical fitness is a state of being that includes skill- and health-related to present and future health outcomes. In particular, cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), muscular fitness (MF) (e.g., muscle endurance, muscle strength, muscle power), and motor fitness (e.g., balance, coordination) can be immensely influenced by lifestyle factors (Ortega et al., 2008). Previous large cohort studies have shown that a lack of physical fitness (i.e., CRF) is an independent risk factor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (LaMonte et al., 2005), even exceeding the influence of other classic factors of CVD such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking and obesity (Lee et al., 2012; Swift et al., 2013). Similarly, MF in both men and women represents a different and independent predictor of cardiometabolic disease (Vaara et al., 2014) in young people and adolescents (Artero et al., 2011; Magnussen et al., 2012). Ruiz et al. (2009) reported a relationship between neuromotor fitness (i.e., muscle endurance, muscle strength, muscle power, speed, flexibility, agility, balance, coordination and reaction time) and health-related outcomes. In their study, physical fitness outcomes were positively related with blood pressure, and inversely related with adiposity markers, such as fat mass and abdominal obesity in children and adolescents (Ruiz et al., 2009).

Nevertheless, due either to the level of complexity involved in estimating physical fitness or the expense and difficulty associated with recruiting a qualified testing team and providing accessories, several authors have described easily-administered instruments that do not require sophisticated technology and are/have been validated by self-report scales or questionnaires, such as the five-level activity index (PAI) (Jackson et al., 2012). Researchers working on the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) study developed a self-report questionnaire regarding physical fitness questionnaire called the International Fitness Scale (IFIS) (Ortega et al., 2011). This scale has been validated in adolescents from nine European countries (Ortega et al., 2011), in young adults (18–30 years of age) (Ortega et al., 2013) and children (9–12 years of age) in Spain (Sánchez-López et al., 2015). Moreover, the IFIS has been shown to be strongly associated with CVD risk factors such as body fat or metabolic syndrome (Ortega et al., 2011; Ortega et al., 2013), even in Spanish women with fibromyalgia (Álvarez-Gallardo et al., 2016). Therefore, it appears to be a valid and reliable instrument to measure skill- and health-related physical fitness levels in several populations.

However, there is a lack of instruments and studies written in Spanish evaluating physical fitness, which hampers the determination of the current status of this important health indicator in the Latin population, especially in Colombia. Although the studies noted above have confirmed the validity of the IFIS with European populations, the authors claimed that there is a need to investigate the validity and reliability of this instrument when measuring self-reported physical fitness in other countries and populations (Español-Moya & Ramírez-Vélez, 2014). To the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the validity and reliability of the IFIS outside Europe. Therefore, the present study expands upon the knowledge regarding the application of the IFIS in Latin populations (Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015). The aim of the study was two-fold: to examine the validity of the IFIS with a population-based sample of schoolchildren from Bogota, Colombia and to examine the reliability of the IFIS with children and adolescents from Engativa, Colombia.

Methods

Study design

Schoolchildren included in this secondary analysis are part of The Fuprecol Study (Asociación de la Fuerza Prensil con Manifestaciones Tempranas de Riesgo Cardiovascular en Niños y Adolescentes Colombianos in Spanish) carried out in Bogotá, Colombia. We selected 27 schools, which had already collaboration agreements established with our research center and therefore were selected primarily for pragmatic, budgetary and logistical reasons. The Fuprecol Study methodology has been published elsewhere (Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015; Prieto-Benavides, Correa-Bautista & R., 2014; Rodríguez-Bautista et al., 2014). Data were collected from 2013 to 2016 and the analysis was done in 2016.

Study population

The subsample consisted of 2,144 schoolchildren, a subsample of the FUPRECOL study. In this sample, 1,873 schoolchildren (54.5% girls) had valid data from the IFIS and anthropometric and blood parameter assessments; consequently, they were included in this study. The exclusion criteria included having a clinical diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, having Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus, being pregnant, using alcohol or drugs, and not having lived in Bogota for at least one school year. Exclusion from the study was made effective a posteriori, without the students being aware of their exclusion, to avoid any undesired situations.

Sample of the reliability study (Engativa, Bogota)

The test-retest study was conducted with a separate age-matched sample of Colombian children and adolescents from the Engativa district, which is located north of Bogota. Based on the minimum size required for validity studies and assuming an attrition rate of 30%, a sample of at least 100 boys and 100 girls was randomly selected from the FUPRECOL study. The sample size was also satisfactory, according to the following formula: n = [(Zα∕2 + Zβ)∕[F(Z0) + F(Z1)]]2 + 3. α = 0.05 (2-side), β = 0.1, Z0.1 = 1.282, F(Z0) = 0 and F(Z1) = 0.40, (Lemeshow et al., 1990).

A total of 229 participants (124 boys and 105 girls) aged 9–17.9 years successfully completed the IFIS on two occasions (one week apart) and were included in the reliability study. In addition, after the retest of the IFIS, physical fitness was measured in this sample using a battery of tests from the FUPRECOL study. The sample size was adequate for both validation and reliability, according to the estimations presented in several studies (Ortega et al., 2013; Sánchez-López et al., 2015; Álvarez-Gallardo et al., 2016). The characteristics of this sample did not differ from those of the FUPRECOL study cohort regarding SES or the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, the same methods were used and investigators employed the IFIS in both studies.

Measurements

Self-reported fitness

Self-reported fitness was assessed using the IFIS, which was originally validated in nine European countries and languages (HELENA study) (Ortega et al., 2011) (http://www.helenastudy.com/IFIS). The IFIS is comprised of 5 Likert-scale questions about self-reported fitness (very poor, poor, average, good, and very good) relating to perceived overall fitness and its main components: CRF, MF, speed and agility, and flexibility. In Colombia, the IFIS had high validity and moderate-to-good reliability in a study with collegiate students (Español-Moya & Ramírez-Vélez, 2014; Sánchez-López et al., 2015) and schoolchildren (Ortega et al., 2011) in European adolescents. All the information about the IFIS can be found at no cost at the website of the PROFITH research group, the original developer of this tool: http://profith.ugr.es/IFIS.

Anthropometric and adiposity variables

Data on the variables were collected at the same time in the morning (between 7:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m.) following an overnight fast in accordance with the ISAK (International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry) guidelines (Marfell-Jones, Stewart & De Ridder, 2006). Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.10 kg with the participant lightly dressed using a portable electronic weight scale (Tanita® BC544; Tanita, Tokyo, Japan) with a low technical error of measurement (TEM = 0.510). Body height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm in bare or stocking feet with the adolescent standing upright against a portable stadiometer (Seca® 274; Seca, Hamburg, Germany; TEM = 0.019). Their BMI was calculated as their body weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in meters (Ruiz et al., 2009). Body fat percentage was measured by bioelectrical impedance with a frequency current of 50 kHz using a BIA-TANITA® Model BF689 (Tanita, Tokyo, Japan; TEM = 0.639) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mean of the two readings taken in the morning under controlled temperature and humidity conditions and after urination and a 15-minute rest when the participants was shoeless and fasting, was used.

Physical fitness

The physical fitness parameters were measured as described previously, and specific aspects relating to the validity and reliability have been reported elsewhere (Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015; Español-Moya & Ramírez-Vélez, 2014). CRF was assessed using the 20-minute shuttle run test (Leger et al., 1988), and the time that it took to complete the last one-half stage (in minutes) was recorded. Results were recorded to the nearest stage completed. The Léger equation was used to determine VO2max (ml/kg/min) in each participant (Leger et al., 1988).

Musculoskeletal fitness (MF) was assessed using two tests. The standing broad jump (lower limb explosive strength assessment) was performed twice, and the best score was recorded (in kg). Additionally, the handgrip strength test (upper-body musculoskeletal strength) was performed using the T-18 TKK SMEDLY III® standard adjustable handle analogue handgrip dynamometer (Takei Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd, Niigata, Japan). Two trials were allowed in each hand, and the average score was recorded (in kg). Thus, the values of handgrip strength that are presented here combined the results of left- and right-handed subjects, without any consideration of hand dominance (España-Romero et al., 2010).

Speed and agility (speed of movement, coordination and agility assessment) were measured using the 4 × 10 shuttle run test. The time that it took to complete the test was recorded to the nearest tenth of a second.

Flexibility was measured according to the standard sit-and-reach test for range of movement (in cm).

Biochemical assessments

Blood samples were obtained from each subject early in the morning, following a 10-hour overnight fast. Before the samples were taken, the fasting condition was confirmed by the child and the parents. Blood samples were obtained from an antecubital vein, and analyses were subsequently completed within one day of collection. The cholesterol linked to high-density lipoproteins (HDL-c), glucose, triglycerides (TG) and total cholesterol were measured using colorimetric enzymatic methods with a Cardiocheck analyzer. The fraction of cholesterol linked to low-density lipoproteins (LDL-c) was calculated using the Friedewald formula (Friedewald, Levy & Fredrickson, 1972). The precision performance of these assays was within the manufacturer’s specifications.

Cardiometabolic risk assessment

We calculated a cardiometabolic risk index (CMRI) as that reflects a continuous score of the five metabolic syndrome risk factors. An age-adjusted CMRI (composite z-score) was calculated for each participant using the following formula: CMRI = z-WC +z-triglycerides +z-HDL-C +z-glucose+z-SBP +zDBP. The HDL-c value was then multiplied by −1, as it is inversely related to cardiovascular risk.

The components of the score were selected based on the International Diabetes Federation’s (Zimmet et al., 2007) and the modified De Ferranti et al.’s (2004) definitions of metabolic syndrome (MetS). The higher the CMRI value, the higher the cardiovascular risk. All cut-off values were based on data that were obtained from schoolchildren internationally (Chan et al., 2015; Cruz et al., 2004; Suárez-Ortegón et al., 2012).

Sexual maturation

Participants self-assessed their sexual maturation of secondary sex characteristics (breast and pubic hair development for girls, genital and pubic hair development for boys; ranging from stage I to V), according to the criteria of Tanner & Whitehouse (1976) and Matsudo & Matsudo (1994). The data were recorded on paper by the FUPRECOL evaluators.

Ethics statement

The Fuprecol Study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration for Human Studies and approved by the Colombian Data Protection Authority (Resolution 008430/1993 Ministry of Health) and the Review Committee for Research on Human Subjects at the University of Rosario (Code No CEI-ABN026-000262). All participants were informed of the study’s goals, and written informed consent was obtained from participants and their parents or legal guardians.

Statistical analysis

The test-retest reliability of the IFIS was indicated by the weighted kappa coefficient, which is more appropriate when dealing with ordered categorical data (Cohen, 1968). The internal consistency of the scales was assessed by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha. The ratings system developed by Landis & Koch (1977) was used to interpret the reliability and internal consistency results, where values ranging from 0.81 to 1.00 represent almost perfect agreement/consistency, 0.61 to 0.80 represent substantial agreement/consistency, 0.41 to 0.60 represent moderate agreement/consistency, 0.21 to 0.40 represent fair agreement/consistency, 0.00 to 0.20 represent slight agreement/consistency, and <0.00 represent poor agreement/consistency. The ability of the IFIS to rank Colombian youths into appropriate physical fitness levels correctly was determined using analysis of variance without any adjustment and then after adjusting (analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)) for sex, age and sexual maturation. Measured fitness variables were entered as dependent variables, whereas self-reported fitness variables were entered as fixed factors. We studied the association between self-reported fitness and both body fat and CMRI using ANCOVA after adjusting for sex, age and sexual maturation. Pairwise post hoc hypotheses were tested using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons using four categories (very poor/poor, average, good and very good). The number of MetS criteria was calculated for each physical fitness component and its categories using the Jonckheere–Terpstra test for trends. All the analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 21 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

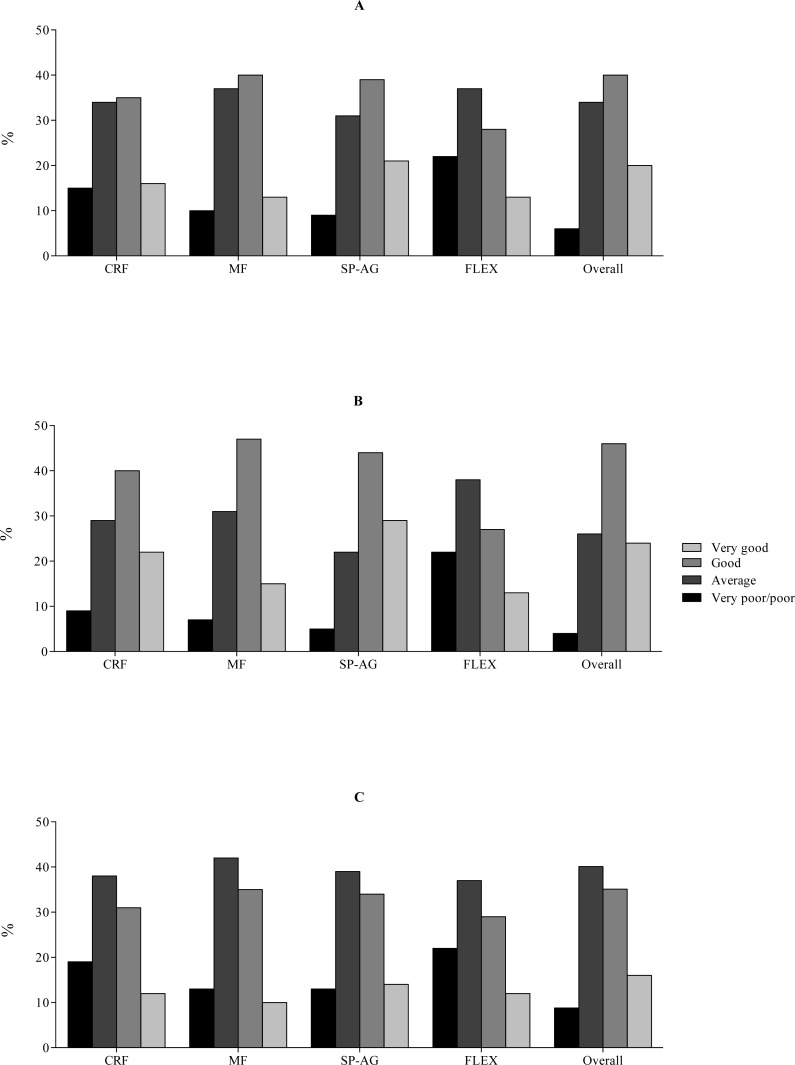

The distribution of the self-reported responses on the IFIS using a 5-point Likert scale was shifted to the right in both genders, with a low percentage of participants reporting a very poor/poor fitness level (Fig. 1). Specifically, poor overall fitness was reported by 2% of the schoolchildren, whereas 4% reported poor, 34% reported average, 40% reported good, and 20% reported very good fitness. Participants who reported average, good, and very good CRF, musculoskeletal fitness, speed/agility, and flexibility had better measured CRF, MF, speed/agility, and flexibility compared to schoolchildren who reported a very poor/poor fitness level on the IFIS (Table 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of the responses to the five questions of the International FItness Scale (IFIS) of schoolchildren in Bogota, Colombia.

CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness; MF, muscular fitness; SP-AG, speed and agility; FLEX, flexibility; and Overall, overall physical fitness (A) Oveall; (B) Boys; (C) Girls.

Table 1. Unadjusted and adjusted means and standard error (SE) of measured physical fitness by self-reported physical fitness categories in Colombian children and adolescents, The FUPRECOL Study (n = 1, 873).

| Components | Very poor/Poor (1) n = 119 | Average (2) n = 618 | Good (3) n = 756 | Very good (4) n = 380 | P-value | Pairwise comparisonsc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 2–3 | 3–4 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | ||||||||

| 20-m shuttle run (VO2max) | 38.7 (0.3) | 40.6 (0.2) | 42.7 (0.1) | 44.4 (0.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Handgrip (kg) | 37.7 (0.5) | 38.8 (0.2) | 39.5 (0.2) | 39.2 (0.4) | 0.009 | 0.286 | 0.328 | 1.000 |

| Standing-long jump (cm) | 132.6 (2.1) | 127.8 (1.1) | 127.5 (0.9) | 132.5 (1.8) | 0.029 | 0.294 | 1.000 | 0.139 |

| Shuttle run 4 ×10 m (s)b | 15.3 (0.1) | 14.9 (0.1) | 14.3 (0.1) | 14.1 (0.1) | <0.001 | 0.081 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Sit and reach (cm) | 20.1 (0.3) | 20.6 (0.2) | 21.3 (0.5) | 22.5 (0.3) | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.355 |

| Adjusteda | ||||||||

| 20-m shuttle run (VO2max) | 40.0 (0.4) | 40.7 (0.1) | 42.2 (0.1) | 43.0 (0.2) | <0.001 | 0.790 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Handgrip (kg) | 37.8 (0.5) | 38.9 (0.2) | 39.4 (0.2) | 39.3 (0.4) | 0.050 | 0.042 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Standing-long jump (cm) | 136.6 (2.1) | 127.9 (1.0) | 127.3 (1.0) | 132.0 (1.9) | 0.036 | 0.318 | 1.000 | 0.183 |

| Shuttle run 4 ×10 m (s)b | 15.2 (0.1) | 14.8 (0.1) | 14.4 (0.1) | 14.1 (0.1) | <0.001 | 0.068 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sit and reach (cm) | 20.8 (0.3) | 20.5 (0.2) | 21.4 (0.5) | 22.4 (0.3) | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.592 |

Notes.

Analysis of covariance adjusted for sex, age and sexual maturation status.

Lower scores indicating higher levels of speed-agility.

Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons.

Table 2 shows the test-retest reliability statistics in children and adolescents from Engativa, Colombia for the five items that compose the IFIS, that is, overall fitness and four main fitness components: CRF, MF, speed and agility, and flexibility. The weighted kappa values ranged from 0.775 (handgrip) to 0.847 (standing long jump), and the average weighted kappa was 0.811.

Table 2. Test–retest (1 week apart) reliability of self-reported fitness in schoolchildren from Bogota, Colombia (n = 229).

| IFIS components | Test mean (SD) | Re-test mean (SD) | Kappa | 95% CI | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | 3.75 (0.81) | 3.71 (0.85) | 0.834 | 0.786–0.871 | 0.733 |

| Muscular fitness | 3.42 (0.97) | 3.52 (0.97) | 0.775 | 0.710–0.825 | 0.743 |

| Speed and agility | 3.54 (0.89) | 3.55 (0.86) | 0.847 | 0.803–0.881 | 0.763 |

| Flexibility | 3.78 (0.95) | 3.7 (0.94) | 0.797 | 0.739–0.842 | 0.726 |

| Overall fitness | 3.24 (1.00) | 3.33 (1.01) | 0.802 | 0.745–0.846 | 0.789 |

Notes.

- IFIS

- International Fitness Scale

- SD

- standard deviation

- α

- Cronbach’s alpha

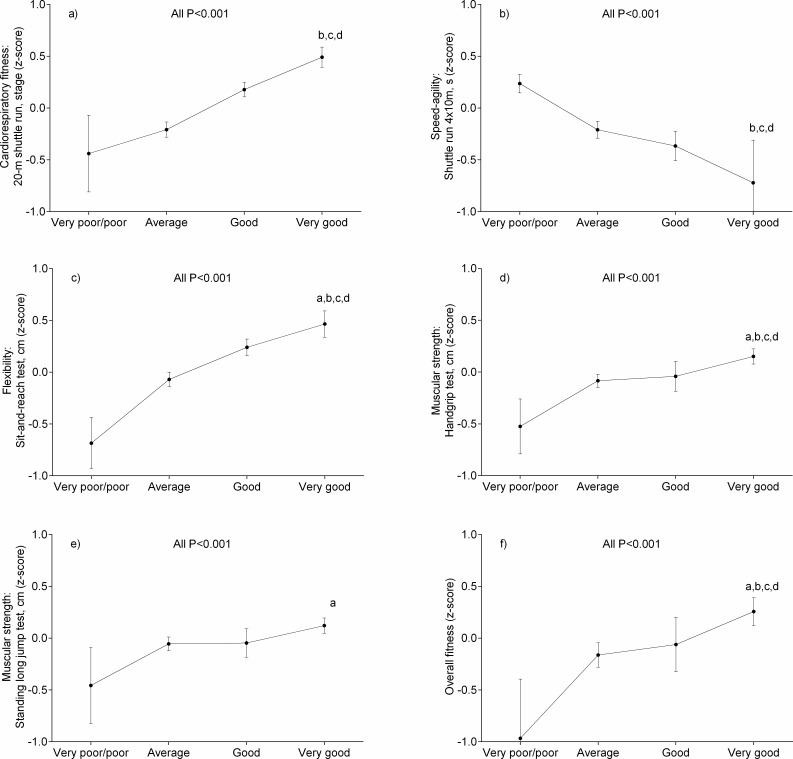

The relationships between self-reported and measured variables are show in Fig. 2. Overall, participants with a high level of self-reported fitness (i.e., good and very good categories) had higher measured CRF, MF, speed and agility, and flexibility compared to schoolchildren reporting very poor/poor fitness level (all p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Associations between measured physical fitness and self-reported physical fitness categories in schoolchildren from Bogota, Colombia.

Data represented means and 95% confidence intervals. Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons: (A) “good” vs “very good”; (B) “average” vs “very good”; (C) “very poor/poor” vs “very good”; (D) “very poor/poor” vs “very good”. Data represented means and 95% confidence intervals. All significance levels were p < 0.001.

Figure 3 shows the association between self-reported fitness categories and CMRI and body fat. We observed an inverse association between body fat and CRF, MF, speed and agility, flexibility, and overall fitness (Fig. 3A). Finally, the CMRI score in Fig. 3B shows that a high level of self-reported CRF, MF, speed and agility, flexibility, and overall fitness is related to a lower CVD risk. For all the associations, the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Figure 3. Associations between self-reported fitness, cardiometabolic risk index and body fat in schoolchildren from Bogota, Colombia.

CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness; HG, handgrip strength; SLT, standing long jump test; SP-AG, speed and agility; Overall, overall physical fitness. ≠ Significance levels were p (trend) <0.001.

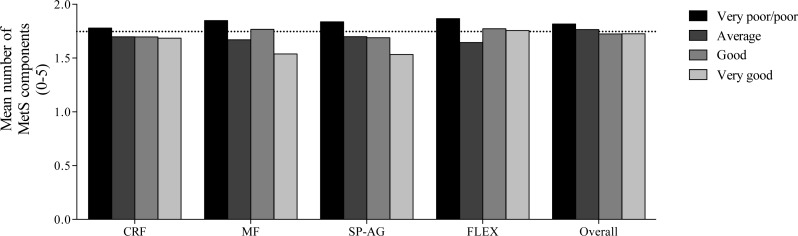

Finally, Fig. 4 shows a dose–response relationship between self-reported physical fitness components, their categories and the number of MetS criteria (as defined by De Ferranti et al., 2004) in children and adolescents. As shown in the figure, a significant trend across categories was observed for all the components (ps < 0.001).

Figure 4. Trend distribution of number of metabolic syndrome components criteria (defined by De Ferranti et al., 2004) according to self-reported physical fitness components and its categories (the Jonckheere–Terpstra test).

Horizontal line indicates the mean number of metabolic syndrome components in the overall population. CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness; MF, muscular fitness; SP-AG, speed and agility; and Overall, overall physical fitness.

Discussion

Our study shows that the IFIS had substantial validity and test-retest reliability for ranking schoolchildren according to their objectively measured health-related physical fitness. Additionally, self-reported CRF, MF, speed and agility, and flexibility as measured by the IFIS were negatively associated with lower CVD and adiposity risk in the schoolchildren who were examined.

Regarding the examination of the validity of the IFIS in Colombian schoolchildren, our results showed significant differences in the measured physical fitness components (CRF, MF, speed and agility, and flexibility) between schoolchildren reporting poor and very poor levels and those reporting average, good, and very good levels. These results are consistent with the studies of the HELENA project, which demonstrated that the IFIS has good validity in different populations (Ortega et al., 2011; Ortega et al., 2013; Sánchez-López et al., 2015). Results from the nine European countries showed that youths (3,528 adolescents aged 12.5–17.5 years) with good or very good physical fitness had better measured fitness compared to those self-reporting poor or very poor fitness on the IFIS; however, a linear dose–response relationship between self-reported and objectively measured physical fitness on the IFIS was observed (Ortega et al., 2011). In another study of 276 young adults (18–30 years of age), Ortega et al. (2013) observed that participants reporting good/very good CRF, musculoskeletal fitness and flexibility had better measured CRF, musculoskeletal fitness and flexibility compared to middle-aged adults reporting poor/very poor fitness.

Consistent with previous findings, there was a dose–response association between self-reported and measured CRF and flexibility, whereas the dose–response association between self-reported and measured MF was linear only when MF was expressed as an absolute value (Ortega et al., 2013). In addition, in Spanish children aged 9–12 years, Sánchez-López et al. (2015) observed that participants reporting average, good and very good CRF, MF, speed and agility, and flexibility had better performance cardiovascular endurance, musculoskeletal fitness, agility/speed and flexibility compared to those reporting very poor and poor physical fitness. Additionally, dose–response associations between self-reported and measured CRF, speed and agility, and flexibility as well as MF when expressed in absolute terms were observed (Sánchez-López et al., 2015). Moreover, even in specific populations such as women with fibromyalgia, the IFIS has shown good validity (Álvarez-Gallardo et al., 2016). The test-retest reliability of the IFIS observed in the present study revealed a weighted kappa ranging from 0.775 to 0.847 (average 0.811), which could be considered good agreement in our population. The reliability of the IFIS demonstrated in our study was higher than the test-retest coefficients observed in previous studies that analyzed Spanish children between nine and twelve years of age (average kappa = 0.70), adolescents from different European countries (kappa coefficients ranged from 0.54 to 0.65), Spanish young adults aged 18–30 years (average kappa = 0.70), and Spanish women with fibromyalgia (average kappa = 0.45). Differences across studies might be due to population characteristics; consequently, it would be interesting to replicate the study in other populations and perform future confirmatory studies to analyze the scale’s validity and reliability. Therefore, the present results suggest that the IFIS is a very reliable tool for use with Latin schoolchildren from Bogota, Colombia.

It has been shown that poor physical fitness (i.e., CRF) is an independent risk factor of CVD (LaMonte et al., 2005). In addition, it has been demonstrated that neuromotor fitness is associated with health outcomes such as systolic blood pressure and the sum of four skinfolds (Ruiz et al., 2009). The feasibility of conducting physical assessments to identify CVD risk factors is a crucial factor in environments in which time, equipment or qualified personnel might not be available (Ruiz et al., 2009). In this context, physical fitness questionnaires such as the IFIS might be useful, as self-reported fitness levels have been associated with CVD risk factors in different populations (Ortega et al., 2011; Ortega et al., 2013; Sánchez-López et al., 2015). Our study has shown that self-reported CRF, MF, speed and agility, flexibility, and overall fitness were inversely associated with CMRI and percentage of body fat, confirming previous studies of children (Ortega et al., 2011), young adults (Ortega et al., 2013), and adolescents (Sánchez-López et al., 2015) that also employed the IFIS. Sánchez-López et al. (2015) found that self-reported fitness levels were inversely associated with adiposity parameters (BMI, waist-to-height ratio and body fat-mass index). These authors also showed that CRF and speed and agility fitness levels were inversely associated with lower levels of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, HOMA, mean blood pressure and C-reactive protein. Taken together, these results suggest that the IFIS can be considered a useful instrument to investigate cardiometabolic risk using self-reported physical fitness indicators.

The strengths of the present study are: (i) this is one of the first studies on IFIS validity in a Latin population, explicitly describing the conceptual framework within which the IFIS was applied; and (ii) the present study has advanced the current knowledge regarding the validity and reliability of the IFIS, because we investigated these issues in a very large sample from a different country than those where the IFIS has been previously tested. However, the present study also has limitations. Although we investigated the validity and reliability of the IFIS in schoolchildren in a Latin country, more studies are needed for additional cross-validation testing in different ethnic groups of South America and other regions. In addition, the present data might have been affected by the average fitness level of the region, as all the schoolchildren assessed were recruited from the same region of Colombia. Although the instrument is not immune to the problems that are inherent in all self-report instruments such as their sensitivity to social prejudice, convenience and coherence, it has been shown that the IFIS is reliable in terms of estimating youth physical fitness.

Conclusion

Our results have shown that the IFIS has validity when ranking Latin schoolchildren according to their directly measured health-related physical fitness. In addition, the present study has shown that the IFIS has good test-retest reliability in this population. Furthermore, a high level of self-reported fitness was associated with lower CVD and adiposity risk in children and adolescents from Bogota, Colombia.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bogota district students, teachers, schools, and staff for their enthusiastic participating in the study.

Funding Statement

The FUPRECOL Study was supported by the Instituto Colombiano para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Tecnología “Francisco José de Caldas” COLCIENCIAS under Grant Contract No 671-2014 Code 122265743978. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Robinson Ramírez-Vélez conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Sandra Milena Cruz-Salazar conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments.

Myriam Martínez conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools.

Eduardo L. Cadore contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper.

Alicia M. Alonso-Martinez conceived and designed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables.

Jorge E. Correa-Bautista analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools.

Mikel Izquierdo contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Francisco B. Ortega wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Antonio García-Hermoso performed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Human Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

The Review Committee for Research on Human Subjects at the University of Rosario (Code No CEI-ABN026-000262) approved all the study procedures. A comprehensive verbal description of the nature and purpose of the study and its experimental risks was given to the participants and their parents/guardians. This information was also sent to parents/guardians by mail. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and subjects before participation in the study. The protocol was in accordance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and current Colombian laws governing clinical research on human subjects (Resolution 008430/1993 Ministry of Health).

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data was made available for peer review but cannot be published due to legal restrictions and ethical imposed by the authors’ IRB (Uviversidad del Rosario (No CEI-ABN026-000262, Resolution 008430/1993 Ministry of Health). The subjects are children and adolescent students of Public Schools Colombia (Law No 1.581, October 2012 and National Decret No 1377 de 2013) and did not give consent to share their data. The authors are able to share a de-identified data set with other academic researchers who have obtained IRB approval from their institution to analyze these data. These researchers will be required to sign a data confidentiality and protection agreement.

References

- Álvarez-Gallardo et al. (2016).Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Soriano-Maldonado A, Segura-Jiménez V, Carbonell-Baeza A, Estévez-López F, McVeigh JG, Delgado-Fernández M, Ortega FB. International FItness Scale (IFIS): construct validity and reliability in women with fibromyalgia: the al-Ándalus Project. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016;97(3):395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.08.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artero et al. (2011).Artero EG, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, España-Romero V, Vicente-Rodríguez G, Molnar D, Gottr F, González-Gross M, Breidenassel C, Moreno LA, Gutiérrez A. Muscular and cardiorespiratory fitness are independently associated with metabolic risk in adolescents: the HELENA study. Pediatrics Diabetes. 2011;12:704–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan et al. (2015).Chan NP, Choi KC, Nelson EAS, Chan JC, Kong AP. Associations of pubertal stage and body mass index with cardiometabolic risk in Hong Kong Chinese children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatrics. 2015;15:1. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen (1968).Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin. 1968;70:213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz et al. (2004).Cruz ML, Weigensberg MJ, Huang TT-K, Ball G, Shaibi GQ, Goran MI. The metabolic syndrome in overweight Hispanic youth and the role of insulin sensitivity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89:108–113. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ferranti et al. (2004).De Ferranti SD, Gauvreau K, Ludwig DS, Neufeld EJ, Newburger JW, Rifai N. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in American adolescents findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Circulation. 2004;110:2494–2497. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145117.40114.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España-Romero et al. (2010).España-Romero V, Ortega FB, Vicente-Rodríguez G, Artero EG, Rey JP, Ruiz JR. Elbow position affects handgrip strength in adolescents: validity and reliability of Jamar, DynEx, and TKK dynamometers. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2010;24:272–277. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b296a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Español-Moya & Ramírez-Vélez (2014).Español-Moya MN, Ramírez-Vélez R. Psychometric validation of the International FItness Scale (IFIS) in Colombian youth. Revista Espanola De Salud Publica. 2014;88:271–278. doi: 10.4321/S1135-57272014000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald, Levy & Fredrickson (1972).Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical Chemistry. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson et al. (2012).Jackson AS, Sui X, O’Connor DP, Church TS, Lee D-C, Artero EG, Blair SN. Longitudinal cardiorespiratory fitness algorithms for clinical settings. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMonte et al. (2005).LaMonte MJ, Barlow CE, Jurca R, Kampert JB, Church TS, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness is inversely associated with the incidence of metabolic syndrome a prospective study of men and women. Circulation. 2005;112:505–512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.503805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis & Koch (1977).Landis JR, Koch GG. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics. 1977;33:363–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al. (2012).Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, Group LPASW. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 2012;380:219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger et al. (1988).Leger L, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. Journal of Sport Sciences. 1988;6:93–101. doi: 10.1080/02640418808729800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemeshow et al. (1990).Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW, Klar J, Lwanga SK. Adequacy of sample size in health studies. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1990. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Magnussen et al. (2012).Magnussen CG, Schmidt MD, Dwyer T, Venn A. Muscular fitness and clustered cardiovascular disease risk in Australian youth. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 2012;112:3167–3171. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfell-Jones, Stewart & De Ridder (2006).Marfell-Jones MJ, Stewart A, De Ridder J. International standards for anthropometric assessment. Potchefstroom: ISAK; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Matsudo & Matsudo (1994).Matsudo SMM, Matsudo VKR. Self-assessment and physician assessment of sexual maturation in Brazilian boys and girls: concordance and reproducibility. American Journal of Human Biology. 1994;6:451–455. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1310060406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega et al. (2008).Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, Sjöström M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:1–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega et al. (2011).Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, España Romero V, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Martínez-Gómez D, Manios Y, Béghin L, Molnar D, Widhalm K, Moreno LA, Sjöström M, Castillo MJ. The International Fitness Scale (IFIS): usefulness of self-reported fitness in youth. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;40:701–711. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega et al. (2013).Ortega F, Sanchez-Lopez M, Solera-Martinez M, Fernandez-Sanchez A, Sjöström M, Martinez-Vizcaino V. Self-reported and measured cardiorespiratory fitness similarly predict cardiovascular disease risk in young adults. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2013;23:749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Benavides, Correa-Bautista & R. (2014).Prieto-Benavides D, Correa-Bautista J, Ramírez-Vélez R. Physical fitness and screen time among children and adolescent from Bogotá, Colombia. Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2014;32:2184–2192. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.5.9576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Vélez et al. (2015).Ramírez-Vélez R, Rodrigues-Bezerra D, Correa-Bautista JE, Izquierdo M, Lobelo F. Reliability of health-related physical fitness tests among Colombian children and adolescents: the FUPRECOL study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0140875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Bautista et al. (2014).Rodríguez-Bautista Y, Correa-Bautista J, González-Jiménez E, Schmidt-RioValle J, Ramírez-Vélez R. Values of waist/hip ratio among children and adolescents from bogotá, colombia: the fuprecol study. Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2014;32:2054–2061. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.5.9633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz et al. (2009).Ruiz JR, Castro-Piñero J, Artero EG, Ortega FB, Sjöström M, Suni J, Castillo MJ. Predictive validity of health-related fitness in youth: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;43(12):909–923. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.056499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-López et al. (2015).Sánchez-López M, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, García-Hermoso A, Jiménez-Pavón D, Ortega F. Construct validity and test–retest reliability of the International Fitness Scale (IFIS) in Spanish children aged 9–12 years. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2015;25:543–551. doi: 10.1111/sms.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Ortegón et al. (2012).Suárez-Ortegón M, Ramírez-Vélez R, Mosquera M, Méndez F, Aguilar-de Plata C. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in urban Colombian adolescents aged 10–16 years using three different pediatric definitions. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2012;59:145–149. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift et al. (2013).Swift DL, Lavie CJ, Johannsen NM, Arena R, Earnest CP, O’Keefe JH, Milani RV, Blair SN, Church TS. Physical activity cardiorespiratory fitness and exercise training in primary and secondary coronary prevention. Circulation Journal. 2013;77:281–292. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner & Whitehouse (1976).Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH. Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of puberty. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1976;51:170–179. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.3.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaara et al. (2014).Vaara J, Fogelholm M, Vasankari T, Santtila M, Häkkinen K, Kyröläinen H. Associations of maximal strength and muscular endurance with cardiovascular risk factors. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;35:356–360. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmet et al. (2007).Zimmet P, Alberti KGM, Kaufman F, Tajima N, Silink M, Arslanian S, Wong G, Bennett P, Shaw J, Caprio S. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents–an IDF consensus report. Pediatrics Diabetes. 2007;8:299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data was made available for peer review but cannot be published due to legal restrictions and ethical imposed by the authors’ IRB (Uviversidad del Rosario (No CEI-ABN026-000262, Resolution 008430/1993 Ministry of Health). The subjects are children and adolescent students of Public Schools Colombia (Law No 1.581, October 2012 and National Decret No 1377 de 2013) and did not give consent to share their data. The authors are able to share a de-identified data set with other academic researchers who have obtained IRB approval from their institution to analyze these data. These researchers will be required to sign a data confidentiality and protection agreement.