Abstract

Abnormal accumulation of TDP-43 into cytoplasmic or nuclear inclusions with accompanying nuclear clearance, a common pathology initially identified in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), has also been found in Alzheimer’ disease (AD). TDP-43 serves as a splicing repressor of nonconserved cryptic exons and that such function is compromised in brains of ALS and FTD patients, suggesting that nuclear clearance of TDP-43 underlies its inability to repress cryptic exons. However, whether TDP-43 cytoplasmic aggregates are a prerequisite for the incorporation of cryptic exons is not known. Here, we assessed hippocampal tissues from 34 human postmortem brains including cases with confirmed diagnosis of AD neuropathologic changes along with age-matched controls. We found that cryptic exon incorporation occurred in all AD cases exhibiting TDP-43 pathology. Furthermore, incorporation of cryptic exons was observed in the hippocampus when TDP-43 inclusions was restricted only to the amygdala, the earliest stage of TDP-43 progression. Importantly, cryptic exon incorporation could be detected in AD brains lacking TDP-43 inclusion but exhibiting nuclear clearance of TDP-43. These data support the notion that the functional consequence of nuclear depletion of TDP-43 as determined by cryptic exon incorporation likely occurs as an early event of TDP-43 proteinopathy and may have greater contribution to the pathogenesis of AD than currently appreciated. Early detection and effective repression of cryptic exons in AD patients may offer important diagnostic and therapeutic implications for this devastating illness of the elderly.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, ALS/FTD, Hippocampal sclerosis, TDP-43 proteinopathy, cryptic exon, neurodegeneration

Introduction

TDP-43 neuronal and glial inclusions have unified FTD and ALS neuropathologically into one disease spectrum [22]. Moreover, missense mutations in TDP-43 are also linked to familial ALS, strongly supporting the idea that TDP-43 proteinopathy is central to the pathogenesis of sporadic disease [15, 24]. As a member of heterogeneous ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), TDP-43 is thought to play roles in regulating RNA splicing, stability, and transport through its RNA-recognition domains [5]. Initial studies suggest that TDP-43 may regulate alternative splicing of a subset of conserved exons [23, 27]. Recent studies indicate of TDP-43 binds to UG dinucleotide repeat and represses the splicing of nonconserved cryptic exons [18, 25]. When TDP-43 is depleted, nonconserved cryptic exons are spliced into messenger RNA, often introducing frameshifts and/or premature stop codons, promoting nonsense-mediated decay of target RNAs. Coupled with the finding that polypyrimidine track-binding protein 1 (PTBP1) and polypyrimidine track-binding protein 2 (PTBP2) repress cryptic exons by utilizing CU dinucleotide repeat, TDP-43 represents the founding member of this unique class of microsatellite binding cryptic exon repressors [17]. Importantly, TDP-43’s role in repressing nonconserved cryptic exons has been maintained across evolution and nonconserved cryptic exon incorporation was readily observed in postmortem brain tissues from ALS and FTD patients [18], suggesting that this splicing defect is one mechanism underlying TDP-43 proteinopathy.

While extracellular neuritic β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and intracellular tau neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are well-recognized canonical hallmarks for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), TDP-43-positive inclusions have recently been identified in 30–70% of brains with pathologically diagnosed AD [3, 13]. The morphological characteristics of the TDP-43 deposition are similar across different regions of the brain, predominantly neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions; less commonly dystrophic neurites and only rarely intranuclear inclusions [11]. However, the TDP-43 burden in AD appears to follow a stereotypic topographic progression [10, 11]. The abnormal TDP-43 accumulation in neuronal cytoplasm, neurites, or nucleus starts in the amygdala, then moves to the entorhinal cortex and subiculum, subsequently to the dentate fascia of the hippocampus and occipitotemporal cortex, then to limbic as well as brainstem regions, and finally to basal ganglia and middle frontal cortex. Importantly, greater cognitive impairment and medial temporal atrophy are associated with greater TDP-43 burden and more extensive TDP-43 distribution [12, 14]. TDP-43 pathology-positive subjects are 10 times more likely to be cognitively impaired at death compared to TDP-43-pathology negative cases. However, how the TDP-43 effects on cognition and brain atrophy are mediated are not known. We speculate that loss of TDP-43’s ability to repress cryptic exons may contribute to this exacerbated cognitive decline in AD cases exhibiting TDP-43 pathology. It is possible that the nuclear depletion of TDP-43 rather than its cytoplasmic aggregates contributes to disease pathogenesis. In our initial attempt to address this important question, we screened postmortem brain tissues to determine whether TDP-43 repression of nonconserved cryptic exons are impaired in AD brains.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The brain bank at Johns Hopkins Brain Resource Center database from 2000 to May 2006 was searched for cases with AD neuropathologic change and adequate frozen tissue available from the dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus for additional molecular and histologic studies. All AD subjects had been prospectively recruited and followed in the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) between 1986 and 2016 and had undergone a clinical evaluation by a dementia specialist, completed neuropsychological testing and were determined to be cognitively impaired before death. All AD cases fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (1) age over 65 years old, (2) less than 24 hour postmortem interval (PMI) between the times of death and tissue collection, (3) no mixed co-morbid conditions such as Lewy body disease and tauopathies. All control cases, in addition to satisfying the above age and PMI criteria, had no medical history of neurodegenenative diseases and no significant pathological findings in the brain except hypoxic-ischemic changes as confirmed by both histologic examination and immunohistochemical staining with Aβ, phospho-tau, synuclein, TDP-43, and ubiquitin antibodies. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB. All patients or their proxies provided written informed consent before participating in any research activity.

Neuropathological examinations

Neuropathological examinations were performed according to National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) guidelines [9, 20]. Every specimen was assigned an “ABC” score that incorporates histopathologic assessments of amyloid β deposits (A) using a modified version of Thal phases of Aβ accumulation[26], Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage (B) using a modified Bielschowsky silver stain[4], and neuritic plaque scoring (C) using CERAD recommendations [19].

RT-PCR of Cryptic Exon Targets

Total RNA was extracted from human brain tissue using Trizol (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, K1622). Cryptic exons in GPSM2 and ATG4B were amplified using the primers described previously[18].

For GPSM2 cryptic exon:

PCR reactions were performed using Dream Taq Green PCR Master Mix (2X) (Thermo Scientific, K1081) with the following protocol:

| Initial Denaturation: | 95°C for 60s |

| 45 Cycles: | 95°C for 30s |

| 60°C for 30s | |

| 72°C for 30s | |

| Final Extension: | 72°C for 5min |

For ATG4B cryptic exon:

PCR reactions were performed using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB, M0530S) with the following protocol:

| Initial Denaturation: | 98°C for 60s |

| 45 Cycles: | 98°C for 8s |

| 63°C for 12s | |

| 72°C for 30s | |

| Final Extension: | 72°C for 7min |

For HDGFRP2 cryptic exon, the following primers were used in this study:

HDGFRP2-F: CTGCGCTAAAGATGTCGGTCT

HDGFRP2-R: TGCTTCCCTCCCTTCTGATGC

PCR reaction was performed using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB, M0530S) with the following protocol:

| Initial Denaturation: | 98°C for 30s |

| 35 Cycles | 98°C for 8s |

| 68°C for 12s | |

| 72°C for 15s | |

| Final Extension: | 72°C for 7min |

PCR products were then analyzed by gel electrophoresis, excised, and extracted using the Monarch DNA Gel Extraction Kit (NEB, #T1020S). Sanger sequencing was performed with the 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequencing data was aligned using UCSC Blast to ensure that the amplified product originated from cryptic exon splicing.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated by immersion in a descending series of ethanols. Antigen retrieval was performed using a microwave for 3 min in 10mM citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0). Tissue was incubated for one hour with blocking solution (3% goat serum, 1× TBS and 0.3% Triton X), incubated overnight with primary antibodies (rabbit polyclonal anti-TDP-43, 1:200, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL; anti-NeuN, 1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), subsequently incubated for 1 h with secondary Alexa Fluor 488 goat-anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 594 goat-anti mouse (1:200, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) and counterstained with DAPI (Pierce). Sections were mounted and cover slipped with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Images were obtained using an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope with FITC, Texas Red, and DAPI filters. To visualize co-localization, images from each filter were layered in Photoshop. The tester who performed the visual scan was blind to the cryptic exon status. Nuclear clearance of TDP-43 was considered when the TDP-43 nuclear staining intensity was less than one-tenth of the average TDP-43 nuclear staining intensity from ten randomly selected neurons on the same section.

In order to unambiguously demonstrate the nuclear clearance of TDP-43 and lack of any nuclear or cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in multiple neurons, a 3-D video was constructed from z-stack images captured on confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 700; NIH Award S10 OD016374). Z stack images were set at 0.335 μm thickness capturing a total depth of 9.06 μm using a 63x/1.4 PanApo oil objective. Imaris software version 7.72 was used to reconstruct 3D video form the z-stack images.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed with primary antibodies recognizing N-terminal TDP-43 (rabbit antibody 10782-2-AP, 1:2000, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL) or phosphorylated TDP-43 (monoclonal antibody pS409/410, 1:1000, Cosmo Bio, Carlsbad, CA). Antigen retrieval was performed using a microwave for 3 min in 10mM citrate buffer at pH 6.0. To calculate the number of neurons with nuclear clearance of TDP-43, three representative high-power field views of the dentate gyrus region for each case were selected and only cells with unambiguously neuronal morphology were counted. The ratio was calculated as the number of neurons with nuclear clearance over the total number of neurons in the same high-power field.

Results

To explore the contribution of depletion of TDP-43 in AD cases, we examined a cohort of AD brains: nine cases with low level (ages ranging from 68–96 years old, median age 84 years old), nine cases with intermediate level (ages ranging from 74–101 years old, median age 86 years old), and eight cases with high level AD (ages ranging from 66–94 years old, median age 83 years old) neuropathologic changes according to the NIA-AA guidelines [20] as well as eight age-matched controls (ages ranging from 67–94 years old, median age 70.5 years old, Table 1). Cases were selected to exclude co-morbid conditions such as Lewy body disease and tauopathies. Available frozen tissue from dentate gyrus region in hippocampus were collected no longer than 24 hours PMI (control group: average PMI 13.375 hours; low AD: 13.11 hours; intermediate AD: 8.67 hours and high AD group: 12 hours). TDP-43 proteinopathy was confirmed by distinct neuronal inclusions with accompanying nuclear clearance in seven of the eight high level AD cases (87.5%, Fig. S1, Table 1). Among them, three cases had TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions identified only in the amygdala (Fig. S1-D), the initial stage for TDP-43 to spread in brain [10, 11]. The other four cases showed additional TDP-43 pathology in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus (Fig. S1-C), a stage III according to the updated TDP-43 staging scheme [11]. Similarly, TDP-43 pathology was confirmed in four of the nine intermediate level AD cases (44.4%). All four cases were at stage III TDP-43 pathology with TDP-43 deposition in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. In contrast, no inclusion of TDP-43 was present in any of the low level AD and control brains (Fig. S1-A, B). The testers who performed the subsequent RT-PCR procedures were blinded to the aforementioned information as the control case numbers were mixed with the AD case numbers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of all cases used in this study.

| Case# | Diagnosis | CERAD Score | Braak Stage | Age | Sex | PMI (h) | TDP-43 Pathology | Cryptic Exon Incorporation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | High AD | C | VI | 66 | F | 14 | Dentate | Yes |

| 2 | High AD | B | VI | 87 | F | 17 | Dentate | Yes |

| 3 | High AD | C | VI | 70 | M | 8 | Dentate | Yes |

| 8 | High AD | C | V | 94 | F | 18 | Dentate | Yes |

| 9 | High AD | C | VI | 79 | M | 5 | Amygdala | Yes |

| 10 | High AD | C | V | 92 | F | 12 | Amygdala | Yes |

| 11 | High AD | C | VI | 91 | F | 16 | Amygdala | Yes |

| 12 | High AD | C | V | 67 | M | 6 | Neg | No |

| 13 | Int AD | C | IV | 74 | F | 5 | Dentate | Yes |

| 14 | Int AD | B | III | 86 | F | 3 | Neg | Yes |

| 15 | Int AD | C | IV | 86 | F | 5 | Dentate | Yes |

| 16 | Int AD | B | VI | 101 | F | 8 | Dentate | Yes |

| 19 | Int AD | C | IV | 81 | F | 15 | Dentate | Yes |

| 20 | Int AD | B | IV | 93 | M | 8 | Neg | Yes |

| 21 | Int AD | A | IV | 79 | F | 12 | Neg | Yes |

| 22 | Int AD | B | III | 80 | F | 15 | Neg | Yes |

| 25 | Int AD | B | IV | 91 | M | 7 | Neg | Yes |

| 26 | Low AD | B | II | 96 | M | 3 | Neg | No |

| 27 | Low AD | A | II | 84 | M | 24 | Neg | No |

| 28 | Low AD | C | II | 68 | F | 13 | Neg | No |

| 29 | Low AD | B | II | 85 | M | 8 | Neg | No |

| 30 | Low AD | B | I | 93 | M | 8 | Neg | No |

| 31 | Low AD | C | I | 82 | F | 14 | Neg | No |

| 32 | Low AD | B | II | 96 | F | 22 | Neg | No |

| 33 | Low AD | A | I | 83 | M | 9 | Neg | No |

| 34 | Low AD | B | II | 78 | M | 17 | Neg | No |

| 4 | Control | 0 | 0 | 67 | M | 19 | Neg | No |

| 5 | Control | 0 | 0 | 68 | M | 6 | Neg | No |

| 6 | Control | 0 | 0 | 77 | M | 20 | Neg | No |

| 7 | Control | 0 | 0 | 72 | M | 13 | Neg | No |

| 17 | Control | 0 | 0 | 87 | F | 7 | Neg | No |

| 18 | Control | 0 | 0 | 68 | F | 12 | Neg | No |

| 23 | Control | 0 | 0 | 94 | M | 15 | Neg | No |

| 24 | Control | 0 | 0 | 69 | M | 15 | Neg | No |

Dentate: inclusions seen in both amygdala and dentate gyrus of hippocampus. Amygdala: inclusions only seen in amygdala. Neg: no inclusions seen. PMI (h): post-mortem interval (hours).

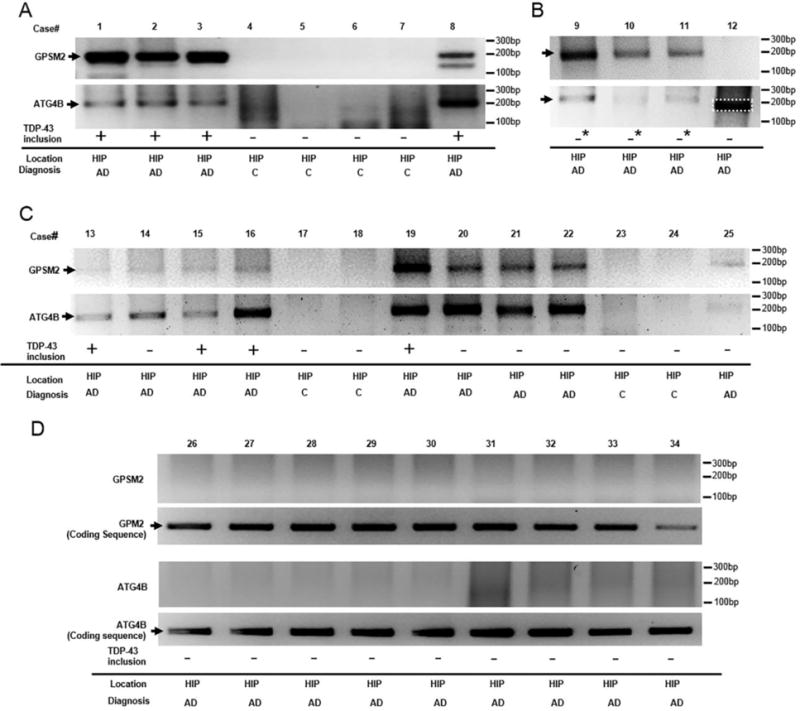

To determine whether TDP-43 repression of nonconserved cryptic exons are impaired in AD brains, we examined the presence of cryptic exons from hippocampus, the most severely affected region in AD. We first used the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) protocol previously designed to amplify across the cryptic exon splice junctions of GPSM2 and ATG4B, the two cryptic exons that have been shown in ALS-FTD cases (Fig. S2-A) [18]. Corresponding PCR products were observed in all eleven TDP-43 inclusion-positive cases with high and intermediate AD levels, but were absent in any of the low level AD or control cases (Fig. 1); the successful amplification of cryptic exon RT-PCR products was further validated by DNA sequencing in all of the eleven samples (Fig. S2-B, C). Interestingly, the presence of cryptic exons in hippocampus was detected in all three AD brains in which TDP-43 inclusions were restricted to the amygdala (cases #9–11). Most surprisingly, cryptic exon incorporations were observed in the five intermediate AD cases which did not exhibit distinct inclusions (Fig. 1C, cases #14, #20–22 and #25), suggesting that TDP-43 inclusion is not a prerequisite for the incorporation of cryptic exons. In summary, seven out of the eight (87.5%) high level AD and all nine intermediate level AD cases (100%) exhibit cryptic exon incorporation.

Figure 1.

Detection of cryptic exon incorporation in AD brain tissue. DNA fragments were detected from hippocampal region at 199 base pairs (bp) (GPSM2) and at 215 bp (ATG4B) for all cases (A–B, subjects with high level AD pathologic change, case #1–3, #8, and #9–11; C, subjects with intermediate level AD pathologic change, cases #13, #15–16, and #19) that displayed TDP-43 proteinopathy (+: inclusions seen in both amygdala and dentate gyrus of hippocampus; ─*: inclusions only seen in amygdala). In addition, cryptic exon incorporation was seen in five cases with intermediate AD pathologic changes (case #14, #20–22 and #25) that did not have detectable TDP-43 inclusions (─: no detectable inclusions found). In contrast, cases with low level AD pathologic change (D, cases #26–34) and controls (cases #4–7 in A, #17–18 and #23–24 in C) did not display these fragments. One case with high level AD pathologic change (#12) and no detectable TDP-43 inclusions failed to show cryptic exon incorporation (the band as outlined in B was of smaller size and confirmed to be negative by sequencing). Conserved exon expression for both targets was shown in D to rule out the possibility that lack of cryptic exon expression was due to technical failure or mRNA degradation. All cases with positive cryptic exon incorporation in A–C and conserved exon expression in D were confirmed by Sanger sequencing analysis. Case demographics and one sample of DNA sequencing validation are provided in table 1 and supplementary figure S2. C, control. HIP, hippocampus.

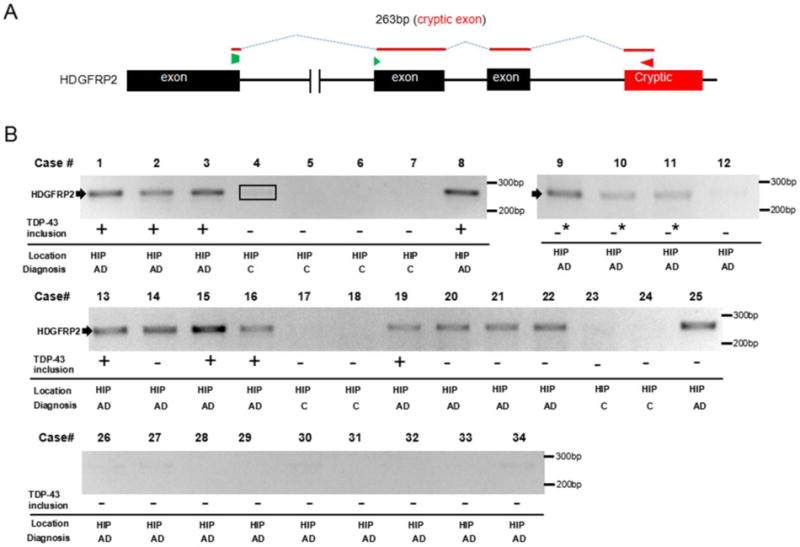

We then went on to further validate TDP-43 loss of function in these AD cases using additional cryptic exon targets identified from the original transcriptome analysis [18]. We identified primer pairs to amplify cryptic exon junctions in HDGFRP2. As expected, cryptic exon for HDGFRP2 was detected in all cases that displayed GPSM2 and ATG4B cryptic exon incorporation (Fig. 2). In order to further confirm that the presence of cryptic exons were driven by loss-of-function of TDP-43, we examined whether cryptic exon can be detected in brains of cases of hippocampal sclerosis (HS), which is defined by pyramidal cell loss and gliosis in the subiculum and CA1 region of the hippocampus [1]. It is a well-known feature of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and up to 71% of HS cases have been found to have TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions [2]. We randomly selected four neuropathologically confirmed HS cases from the Johns Hopkins Brain Bank that matched the age and PMI distribution of the AD patients in our study (ages ranging from 75–98, median age 81.5 years old, PMI average 13 hours, Supplementary Table S1). All four cases exhibited TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in the dentate fascia granular neurons. None of these cases exhibit amyloid accumulation and three of the four cases display lower level of NFTs (Braak stage II); thus, none of these cases qualified for the diagnosis of AD. All four cases displayed incorporation of cryptic exon for GPSM2, ATG4B and HDGFRP2 (Fig. S4), an observation that is consistent with the view that cryptic exon incorporation is not caused directly by β-amyloidosis or tauopathy.

Figure 2.

Further validation of cryptic exon incorporation in AD brain tissue. (A) Diagram of RT-PCR detection strategy to amplify across the cryptic exon splice junction of HDGFRP2. (B) Sequencing confirmed 263 bp HDGFRP2 RT-PCR products were detected in the same cases that showed cryptic exon incorporation of GPSM2 and ATG4B. Similarly, GPSM2 and ATG4B negative cases did not display HDGFRP2 RT-PCR fragment (the band as outlined in case #4 was confirmed to be negative by sequencing). +: inclusions seen in both amygdala and dentate gyrus of hippocampus; ─*: inclusions only seen in amygdala; ─: no solid inclusions. C, control. HIP, hippocampus.

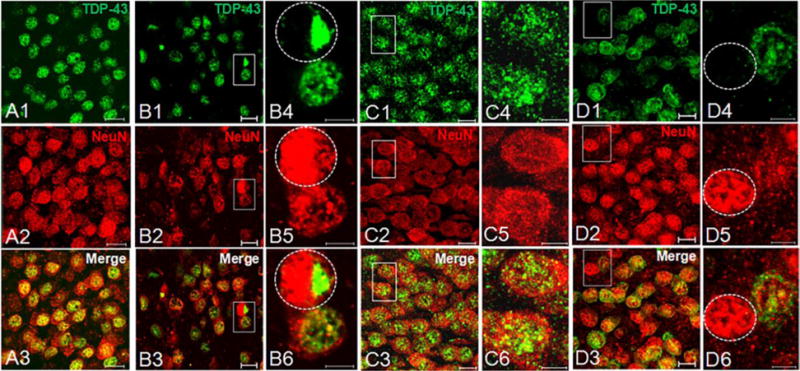

As nuclear function of TDP-43 is critical for cell survival [6, 7], we investigated whether depletion of nuclear TDP-43 as determined by the incorporation of cryptic exons occurs in neurons of AD brains lacking TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusion. We performed dual-label immunofluorescence analysis with antisera recognizing TDP-43 and a neuronal nuclear marker, NeuN (Fig. 3). Whereas no nuclear clearance of TDP-43 was seen in the high level AD case which lacked cryptic exon incorporation (case #12, Fig. 3C1–C3), nuclear clearance of TDP-43 was observed in hippocampal dentate fascia neurons in cases which exhibited incorporation of cryptic exons despite early TDP-43 deposition in amygdala (Fig. 3D1–D6 and supplementary video). Indeed, nuclear clearance of TDP-43 was observed in hippocampal dentate fascia neurons in all five cases which exhibited incorporation of cryptic exons despite complete absence of TDP-43 inclusion (Fig. S5), indicating that the depletion and corresponding loss of nuclear function of TDP-43 from neurons may represent an early event and the inclusion is not necessary to elicit cryptic exon incorporation. The number of neurons with nuclear clearance of TDP-43 varies from case to case, with the lowest one estimated at 1.26% and highest one at 11.18% (Fig. 4).

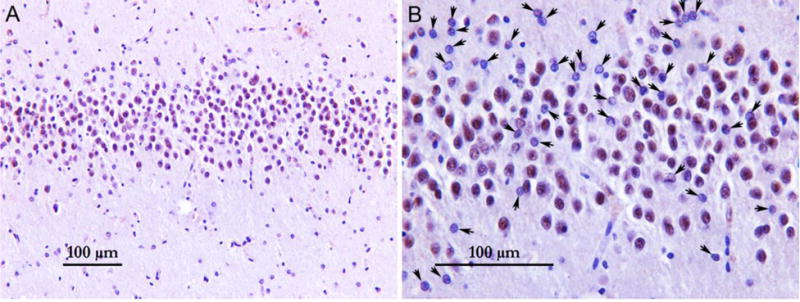

Figure 3.

Dual-label immunofluorescence for TDP-43 and NeuN in dentate fascia granule neurons. (A1–A3)Normal localization of nuclear TDP-43 (phosphorylation-independent antibody, green, A1) merged with neuronal nuclei (NeuN, red, A2) in a control subject (case #4, scale=10 μm). (B1–B3) Large nuclear inclusion and accompanying nuclear clearance (circled nucleus) in a subject with high level AD (case #8, scale=10 μm). Insets of higher magnification are shown in B4–B6 (scale=5 μm). (C1–C3) No cleared nucleus or inclusions are seen in dentate fascia, corresponding to preserved cryptic exon repression in a subject with high level AD (case #12, scale=10 μm). Insets of higher magnification are shown in C4–C6 (scale=5 μm). (D1–D3) In contrast, nuclear clearance of TDP-43 (circled nucleus) in a subject (case #9) with high level AD and TDP-43 inclusions present only in amygdala (scale=10 μm). Insets of higher magnification are shown in D4–D6 (scale=5 μm).

Figure 4.

Low-power field (A) and high-power field (B) view of the dentate gyrus region stained with TDP-43 phosphorylation-independent antibody (case #9). Arrows indicate neurons with nuclear clearance of TDP-43. Only cells with neuronal morphology (large nucleus with open chromatin and a prominent nucleolus) were counted.

Discussion

We report here for the first time that cryptic exon incorporation occurred not only in AD brains exhibiting TDP-43 pathology, but also in neurons lacking cytoplasmic inclusion but exhibiting nuclear clearance of TDP-43. Whether this is the case for other human diseases exhibiting TDP-43 pathology, such as ALS/FTD or sporadic inclusion body myopathy, remains to be seen. Interestingly, one illuminating patient, a 74-year-old female with frontotemporal dementia due to C9orf72 repeat expansion who underwent temporal lobe resection for epilepsy 5 years prior to her first frontotemporal dementia symptom was reported recently [28]. Archival surgical resection tissue demonstrated RNA foci, dipeptide repeat protein inclusions, and loss of nuclear TDP-43 but without TDP-43 inclusions despite florid TDP-43 inclusions at autopsy 8 years after first symptoms, raising important questions about the timing and significance of TDP-43-associated events. Similarly, our data strongly suggest that nuclear clearance of TDP-43 associated with its inability to repress cryptic exons may indicate an early pathogenic event that is much more widespread than currently appreciated.

While a variety of evidence supports a linear disease progression triggered by altered metabolism of β-amyloid leading to canonical pathological hallmarks of neuritic plaques and tau tangles in familial AD, our findings provide evidence to support a multifactorial problem underlying the clinical features of sporadic AD [8, 21]. Recently, we have shown that some populations of pyramidal neurons that are selectively vulnerable in AD are also vulnerable to TDP-43 depletion in mice, while other forebrain neurons appear spared [16]. Moreover, TDP-43 depletion in forebrain neurons of an AD mouse model exacerbates neurodegeneration, and correlates with increased prefibrillar oligomeric Aβ and decreased Aβ plaque burden. Therefore, failure to repress cryptic exons could potentially underlie the TDP-43 proteinopathy and may contribute to the worsening of cognitive decline observed in AD cases exhibiting TDP-43 pathology. Future studies designed to clarify the relationship between TDP-43 pathology and β-amyloidosis or tauopathy will provide mechanistic insights regarding the contribution of nuclear TDP-43 depletion in the pathogenesis of AD.

Interestingly, the contiguous spreading of TDP-43 in AD shares a similar but distinctly different pattern to tau spread as delineated by the Braak staging of neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) [4]. Both tau and TDP-43 spreads from the entorhinal and subiculum to the hippocampus and occipitotemporal gyrus before reaching the neocortex. However, tau pathology begins in the brainstem, in the form of hyperphosphorylated pretangles, prior to deposition of NFTs in transentorhinal cortex. These findings point to TDP-43 proteinopathy as a critical component to AD pathobiology and it appears that TDP-43 proteinopathy occurs after tau pathology. This hypothesis may explain our finding that cryptic exon incorporation was not observed in normal controls or in cases with low level AD pathologic change (Braak stage at either I or II) when the tau pathology is restricted to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions [4]. Of course, insights gleaned from our current effort with small sample size need to be further validated in future studies. To further clarify disease mechanism, it may also be important in the future to identify critical genes affected by cryptic exon incorporation that may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD. Our ability to develop ante-mortem biomarkers to detect cryptic exon incorporation during early stages of disease will allow stratification of AD individuals with or without TDP-43 pathology to empower clinical trials. Finally, future efforts designed to validate therapeutic strategy to repress cryptic exons in model systems may identify potential combination therapy in conjunction with anti-amyloid or anti-tau strategies to address the multifactorial nature of this devastating illness of the elderly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Rudow for assistance in collecting brain tissues. This research was supported in part by McKnight endowment fund for neuroscience (P.C.W and L.C.), the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center pilot grant (L.C.; NIH P50AG05146), the Packard Center for ALS (L.C. and P.C.W.), the JHU Neuropathology Pelda fund (P.C.W.) and the NIH grant (P.C.W.; R01 NS095969).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

M.S., W.B., K.C.L., J.P.L., P.C.W. and L.C. designed, analyzed and interpreted experiments. M.S, K.C.L. and H.H. performed the RT-PCR. W.B., Y.K. and M.S. performed the immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical stains. O.P., J.C.T. and L.C. evaluated brains tissues of AD and controls. L.C., W.B., M.S., and P.C.W. wrote the manuscript, and all authors discussed results and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Amador-Ortiz C, Dickson DW. Neuropathology of hippocampal sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;89:569–572. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)01253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, Personett D, Davies P, Duara R, Graff-Radford NR, Hutton ML, Dickson DW. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:435–445. doi: 10.1002/ana.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arai T, Mackenzie IR, Hasegawa M, Nonoka T, Niizato K, Tsuchiya K, Iritani S, Onaya M, Akiyama H. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta neuropathologica. 2009;117:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta neuropathologica. 2006;112:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buratti E, Baralle FE. TDP-43: gumming up neurons through protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang PM, Ling J, Jeong YH, Price DL, Aja SM, Wong PC. Deletion of TDP-43 down-regulates Tbc1d1, a gene linked to obesity, and alters body fat metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:16320–16324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen TJ, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. TDP-43 functions and pathogenic mechanisms implicated in TDP-43 proteinopathies. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:659–667. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrup K. The case for rejecting the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18:794–799. doi: 10.1038/nn.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, Parisi JE, Petrucelli L, Jack CR, Petersen RC, Dickson DW. Staging TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;127:441–450. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Petrucelli L, Liesinger AM, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW. Updated TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease staging scheme. Acta neuropathologica. 2016;131:571–585. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1537-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, Hu WT, Stroh DA, Baker M, Rademakers R, Boeve BF, Parisi JE, Smith GE, et al. Abnormal TDP-43 immunoreactivity in AD modifies clinicopathologic and radiologic phenotype. Neurology. 2008;70:1850–1857. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304041.09418.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Murray ME, Liesinger AM, Petrucelli L, Senjem ML, Ivnik RJ, Parisi JE, et al. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 and pathological subtype of Alzheimer’s disease impact clinical features. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:697–709. doi: 10.1002/ana.24493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Murray ME, Tosakulwong N, Liesinger AM, Petrucelli L, Senjem ML, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, et al. TDP-43 is a key player in the clinical features associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;127:d811–824. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1269-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard JP, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, et al. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:572–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaClair KD, Donde A, Ling JP, Jeong YH, Chhabra R, Martin LJ, Wong PC. Depletion of TDP-43 decreases fibril and plaque beta-amyloid and exacerbates neurodegeneration in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. Acta neuropathologica. 2016;132:859–873. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1637-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ling JP, Chhabra R, Merran JD, Schaughency PM, Wheelan SJ, Corden JL, Wong PC. PTBP1 and PTBP2 Repress Nonconserved Cryptic Exons. Cell Rep. 2016;17:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ling JP, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Wong PC. TDP-43 repression of nonconserved cryptic exons is compromised in ALS-FTD. Science. 2015;349:650–655. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta neuropathologica. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Three dimensions of the amyloid hypothesis: time, space and ‘wingmen’. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18:800–806. doi: 10.1038/nn.4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Huelga SC, Moran J, Liang TY, Ling SC, Sun E, Wancewicz E, Mazur C, et al. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:459–468. doi: 10.1038/nn.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, Hu X, Vance C, Rogelj B, Ackerley S, Durnall JC, Williams KL, Buratti E, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319:1668–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan Q, Krishna Yalamanchili H, Park J, De Maio A, Lu H-C, Wan Y-W, White JJ, Bondar VV, Sayegh LS, Liu X, et al. Extensive cryptic splicing upon loss of RBM17 and TDP43 in neurodegeneration models. Human molecular genetics. 2016 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–1800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, Konig J, Hortobagyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, et al. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nn.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vatsavayai SC, Yoon SJ, Gardner RC, Gendron TF, Vargas JN, Trujillo A, Pribadi M, Phillips JJ, Gaus SE, Hixson JD, et al. Timing and significance of pathological features in C9orf72 expansion-associated frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2016;139:3202–3216. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.