Abstract

Few studies have examined the associations between health and the cross-border ties that migrants maintain with their family members in communities of origin. We draw on theory related to social ties, ethnic identity, and mental health to examine cross-border ties as potential moderators of the association between migration-related stress and psychological distress among Latino migrants. Using data from the National Latino and Asian American Survey, we find that remittance sending is associated with significantly lower levels of psychological distress for Cuban migrants, and difficulty visiting home is associated with significantly greater psychological distress for Puerto Rican migrants. There were significant associations between migration-related stressors and psychological distress, although these associations fell to non-significance after accounting for multiple testing. We found little evidence that cross-border ties either buffer or exacerbate the association between migration-related stressors and psychological distress. We consider the findings within the current political and historical context of cross-border ties and separation.

Keywords: Immigrant health, cross-border ties, migration-related stress, psychological distress

INTRODUCTION

Sociologists interested in the integration of migrant populations in the United States (U.S.) have long observed the ways in which newcomers maintain connections with family and friends in their communities of origin, as well as the processes by which these home country connections are weakened, strengthened, or altered as immigrants settle into destination communities (Handlin 1951; Thomas and Znaniecki 1918–1919 (1996)). In the past several decades, scholarship documenting the cross-border activities of migrants to the U.S. has expanded rapidly, charting the ways in which migrants maintain social, cultural, economic, and political connections with their communities of origin (Levitt and Jaworsky 2007; Waldinger 2015).

Despite the vast scholarship documenting the existence of cross-border ties, researchers have only recently begun to link cross-border ties and health outcomes (Acevedo-Garcia et al. 2012; Viruell-Fuentes and Schulz 2009). To address this gap, we draw on the broader literature linking social ties and ethnic identity to mental health outcomes to theorize how cross-border ties might be associated with migrant mental health in both positive and negative ways. Further, because migrants grapple with cross-border ties at the same time that they face experiences of social, economic, and occupational integration in the U.S. (Portes and Rumbaut 2014), we examine whether cross-border ties moderate the effects of stressors related to migration and integration (Viruell-Fuentes 2007)—including stressors related to social and occupational experiences, legal status, and family life—on mental health outcomes. Because immigrant transnationalism and integration are not mutually exclusive processes, it is critical to focus on the mental health impacts of both cross-border connections and circumstances of integration (Portes and Rumbaut 2014).

At the same time that scholars focused on cross-border ties have paid limited attention to how these ties might matter for health outcomes, with few exceptions (e.g., Viruell-Fuentes and Schulz 2009), immigrant health researchers have paid limited attention to the cross-border nature of immigrants’ social ties. Despite the large body of work on familism and family cultural conflict with relationship to immigrant mental health outcomes, public health studies have seldom considered where migrants’ family members are located geographically (Mulvaney-Day, Alegria and Sribney 2007; Rivera et al. 2008), and thus have implicitly assumed that immigrant social ties are located solely within the U.S. In the current study, we focus explicitly on the potential associations between ties to family and friends across borders and psychological distress and Latino migrants living in the U.S., and the ways in which these ties might intersect with migration-related stressors, including legal status stressors and family stressors that result from migration.

We begin this paper with a review of the literature on cross-border ties, including the political and historical determinants of these ties. We then summarize prior research pertaining to the relationship between cross-border ties and migrant mental health. Next, we draw on literature linking social ties and ethnic identity, respectively, to mental health to propose a set of mechanisms by which cross-border ties might serve as sources of both risk and resilience for Latino migrants facing migration-related stressors in the U.S.

CROSS-BORDER TIES

Historical and Contemporary Sociological Accounts

Sociologists have stressed the importance of cross-border social and economic ties for U.S. immigrants since the large immigration waves at the turn of the twentieth century. Thomas and Znaniecki (1918–1919 (1996)) first documented these ties by examining letters written by Polish emigrants to family members in their home country; these letters included requests for economic support, inquiries about return visits, and information and emotional support from family members on both ends of the communication.

The focus on the ways in which migrants maintain social, economic, and political connections across borders has continued in present-day sociological inquiry. Much of the contemporary sociological examination of cross-border ties is situated within the broader field of transnationalism, which refers to the social, political, economic, and cultural spaces formed and “constantly reworked by migrants’ simultaneous embeddedness in more than one society” (Levitt and Jaworsky 2007) and the flow of capital, goods, ideas, and individuals within these spaces. As applied to migrants and their family members, transnational scholarship has drawn attention to the “dual lives” of those who engage with communities and countries of origin, even as they undergo processes of integration within the host country (Levitt and Jaworsky 2007; Portes and Rumbaut 2014; Smith 2006). The broader literature on transnationalism includes wide-ranging areas of inquiry related to the influence of several factors—migrant capital, organizations (e.g., hometown associations), and social and cultural changes—on the political, economic, religious, and health-related landscape of communities of origin, as well as on the integration of migrants themselves within host communities (Creighton et al. 2011; Garip 2012; Levitt and Jaworsky 2007; Portes 2007; Portes and Rumbaut 2014).

Determinants of Cross-border Ties

Both individual and macro-level factors influence the prevalence and pattern of the cross-border ties maintained by migrants. At the individual level, one’s social, economic, and political status in the U.S. may structure cross-border ties. Activities like cross-border phone calls and sending at least some amount of money to family and friends in countries of origin may be common among recently arrived immigrants. However some cross-border activities, including cross-border entrepreneurial and political activities, involve substantial economic investment (Portes and Rumbaut 2014; Waldinger 2015), and researchers have shown that return travel to the country of origin is more common among migrants who have been in the U.S. for longer periods of time, who have established employment, and who have savings sufficient to cover the high cost of international travel (Portes and Rumbaut 2014; Soehl and Waldinger 2010).

Macro-level historical and political factors in both places of origin and reception also influence the nature of cross-border ties. The policies, programs, and economic circumstances of a sending country or community can have a significant influence on cross-border activities after migration. For example, Duany (2010) reported that, relative to other migrant groups from Latin America, Puerto Ricans are less likely to send remittances, possibly because Puerto Rico has more public safety net programs (e.g., social security, supplemental food programs) that reduce the need for remittances. In contrast, Mexican, Central American, and some South American migrants report high levels of remittance sending; many of the communities and families in these areas are dependent on the economic resources resulting from migrant labor in the U.S. (Duany 2010).

Contextual factors in the receiving country also shape cross-border ties. The migration policies of the host government (Portes and Rumbaut 2014) and the resulting stratification of migrants by legal status are two of the most significant aspects of the migrant reception context. For example, for the 5.9 million Mexican migrants in the U.S. who are unauthorized (Passel and Cohn 2014), a return trip to Mexico entails a high level of risk due to the dangers associated with crossing the U.S.-Mexico border (Cornelius 2001). Cuban migrants have also historically faced serious barriers to returning to their home country due to the heavy regulation of return visits for U.S. residents (Eckstein 2010). In contrast, because they are U.S. citizens, Puerto Rican migrants are able to move back and forth between the U.S. and Puerto Rico more freely; while important economic barriers persist, there are no legal restraints on movement. Finally, cross-border ties are also structured by the intersection of policies in both the host and receiving contexts. For example, in the early decades of Cuban migration to the U.S., both the U.S. and Cuba placed significant barriers on cross-border engagement, including phone calls and remittances.

Cross-border Ties and Migrant Mental Health

Despite the rich history of inquiry into the nature, prevalence, and determinants of migrant cross-border ties, the social science literature has only recently begun to pay attention to the potential role of these ties in shaping migrant health, including mental health. In the past decade, a small number of studies have uncovered significant associations between cross-border ties and outcomes related to self-rated health, health behaviors, and mental health among contemporary migrants in the U.S. (Alcántara, Molina and Kawachi 2014; Heyman, Núñez and Talavera 2009; Viruell-Fuentes 2006; Viruell-Fuentes and Schulz 2009). Torres (2013) found a set of countervailing associations between cross-border ties and self-rated health for a sample of young adult Latino immigrants in Southern California. Simply having a close relative abroad was significantly associated with better reports of self-rated health for foreign-born respondents, while reporting cross-border separation from parents at some point during childhood was significantly associated with poorer self-rated health. Analyzing a more specific measure of mental health, Alcántara and colleagues (2015) also found both positive and negative effects of cross-border ties: Among a nationally representative sample of adult Latino immigrants, sending remittances to family members abroad was associated with significantly lower odds of experiencing a major depressive episode in the past year. In contrast, respondents who had recently visited their country of origin had significantly greater odds of experiencing a major depressive episode in the past year. In addition, studies by both Miranda and colleagues (2005) and Grzywacz and colleagues (2006) found significant associations between cross-border family separation and poorer mental health among Latino migrants.

Despite the compelling findings from nascent research on cross-border ties and health, many questions remain unanswered. In particular, because cross-border connection occurs at the same time that migrants are undergoing processes of social, economic, and occupational integration within the United States (Portes and Rumbaut 2014), there is a need to understand how cross-border ties and stressors related to the processes of migration and integration intersect in their influence on mental health outcomes. The current study examines two possible roles of cross-border ties in shaping mental health outcomes. First, cross-border connection may serve as a source of resilience for migrants living in the United States, and may buffer the negative impacts of migration-related adversity on mental health outcomes.1 Second, the burden of cross-border social and economic ties, and the challenges related to cross-border separation may serve as a source of risk for U.S. migrants and may exacerbate the negative association between migration-related stressors and mental health by increasing migrants’ sense of social isolation in the face of adversity.

In the following section, we draw on a broader research literature linking social ties and ethnic identity, respectively, to mental health outcomes in order to generate a number of mechanisms by which cross-border ties in particular might be linked to mental health. Throughout, we emphasize the potential for cross-border ties to serve as sources of both risk and resilience for the mental health outcomes of migrants in the U.S. We additionally indicate how the presence of these ties might interact with the stressors faced by migrants in the United States; although this framework has broader applications, we limit our focus to a specific subset of Latino migrants in the United States. We then apply this framework of risk and resilience to specific dimensions of cross-border ties, including cross-border separation and remittance sending.

SOCIAL TIES, ETHNIC IDENTITY, AND MENTAL HEALTH

Scholars linking social ties to mental health have not proposed a singular theory, but rather a set of overlapping mechanisms by which social ties might shape mental health outcomes directly (i.e. main effects), and in interaction with other chronic or acute stressors (Kawachi and Berkman 2001; Thoits 2011). Specifically, social ties can have a positive influence on mental health through pathways of elevated self-esteem, an increased sense of purpose, and feelings of belonging or inclusion (Thoits 2011). Because social ties may help individuals manage chronic, everyday life stressors (e.g., everyday discrimination, occupational stressors) and cope in the aftermath of stressful life events, these ties may buffer the adverse impacts of these stressors on mental health outcomes (i.e. stress-buffering). However, social ties can also be a source of emotional or financial burden and conflict, which may have direct, negative impacts on mental health; moreover, these ties may even exacerbate the adverse influence of other stressors on mental health outcomes (i.e. stress-exacerbating).

Cross-border ties may also serve to strengthen ethnic identity among migrants in the U.S., (Viruell-Fuentes 2006; Viruell-Fuentes and Schulz 2009), which may in turn impact mental health outcomes. Scholars have also proposed that ethnic identity may serve as a source of both risk and resilience for the mental health outcomes of racial and ethnic minority group members (Mossakowski 2003; Phinney 1990; Umaña-Taylor and Updegraff 2007). For one, a strong sense of identification and commitment to one’s ethnic group may be associated with heightened self-esteem and a sense of belonging to a broader ethnic community. Ethnic identity and its potential benefits might be particularly important in the context of the isolation and exposure to everyday and structural discrimination that racial and ethnic minority immigrants face in the United States (Viruell-Fuentes, Miranda and Abdulrahim 2012; Yip, Gee and Takeuchi 2008). As a result, strengthened ethnic identity may have a direct, protective effect on mental health, but may also buffer the adverse impact of discrimination and other stressors on mental health outcomes (Mossakowski 2003; Torres and Ong 2010). However, researchers have also found that ethnic identity can exacerbate the impact of discrimination on mental health outcomes—if ethnic identity comprises a “core” part of an individual’s overall identity, racial or ethnic-based discrimination that targets that core identity might pose an even greater threat to mental health (Yip, Gee & Takeuchi, 2008).

In sum, the literatures on social ties and ethnic identity, respectively, suggest that these forces directly impact mental health in both positive and negative ways, and may also moderate the adverse effects of migration-related stressors on mental health – either buffering or exacerbating the impact of these stressors on health. We subsequently apply this framework of both risk and resilience to the analysis of cross-border social ties, proposing a number of mechanisms by which cross-border ties might have both protective and negative impacts on mental health, and how they might intersect with migrant experiences in the United States to shape mental health.

Cross-border Ties as Sources of Resilience

Cross-border social ties may serve as a unique source of emotional support by promoting a positive sense of self and a feeling of belonging within a broader familial and ethno-national group, particularly in the context of exposure to discrimination, social isolation, and economic challenges (Viruell-Fuentes and Schulz 2009). Family members living across borders may also serve as unique sources of informational support about how to manage adversities in the United States, for example, by providing advice about self-care and sending medications from abroad in the face of barriers to formal healthcare services (Heyman, Núñez and Talavera 2009; Menjívar 2002b).

Remittance sending is one aspect of cross-border ties with the potential to have positive implications for mental health. Remittances are one of the most ubiquitous types of cross-border activities among Latino migrants; in 2010, remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean totaled $58.1 billion, with over $20 billion sent to Mexico alone (World Bank, 2011). For many Latino migrants, remittances remain both an expectation and a viable economic strategy to sustain households in the home country, and research has shown that remittances have significant economic, social, and health impacts on families and communities in countries of origin (Carling 2014; Frank 2005; McKenzie and Menjívar 2011).

Remittances may serve as sources of resilience for migrant mental health. Remittances have symbolic and emotional meaning (Carling 2014), and are often interpreted as an indicator of family cohesion, as being motivated by a sense of altruism, and as a way to fulfill familial obligations and reinforce linkages within the broader family network (Eckstein 2010; Humphries, Brugha and McGee 2009). Experimental and observational studies have shown that the act of giving itself improves mental health (Schwartz et al. 2003; Telzer et al. 2010), although this research has not been extended to cross-border acts of giving. The act of sending remittances to family members abroad in particular may facilitate a sense of role fulfillment and meaning for immigrants, as well as a sense of self-efficacy, particularly if a primary motivation for migration was to help remaining family members in the country of origin. Thoits (2011) suggested that fulfilling roles and obligations within social relationships can provide a sense of “mattering” to others. This sense of “mattering” may be particularly protective of mental well-being in the context of social, political, and economic exclusion faced by many U.S. migrants.

Remittances may also lead to improved socio-economic standing for both migrants and family members living in their country of origin (Eckstein 2010), which may lead to increased status for the migrant in cross-border networks; continued participation in cross-border networks would allow migrants to use individuals in the country of origin as points of social comparison. Experiencing upward socio-economic mobility relative to others in an individual’s cross-border network might buffer the negative effects of migration-related stressors experienced in the United States (Alcántara, Chen and Alegria 2014; Jin et al. 2012).

Cross-Border Ties as Sources of Risk

While cross-border ties may yield a greater sense of social support and belonging, the existence of these ties may also be associated with a sense of social isolation and family separation. The very fact that families are connecting across borders means that they are geographically separated, either temporarily or for extended periods of time (Menjívar 2002a). For U.S. migrants who have undocumented family members, cross-border separation may increasingly be the result of deportation (Dreby 2015; Gonzalez-Barrera and Krogstad 2014), which has direct, negative implications for the psychological well-being of the family members who remain in the United States (Chaudry et al. 2010; Dreby 2015). Family separation may entail the loss of an important source of social support for migrants in the U.S., and may mean that migrants are not able to provide as much direct support to family members living in countries of origin as they would like to (Grzywacz et al. 2006; Horton 2009).

Furthermore, while remittances may have beneficial properties for the family members who receive them, they may also create a temporary or persistent sense of obligation as well as a source of economic strain for family members abroad (Carling, 2014). This burden may be particularly acute for migrants who are already experiencing financial strain, underemployment, or other familial obligations in the United States; financial strain may in turn be linked to poorer health outcomes (Kahn and Pearlin 2006). In addition to having direct, adverse impacts on mental health, the strain of cross-border separation, either from family members or a broader ethno-national community, and the potential burden of remittance sending, may exacerbate the adverse mental health impact of stressors experienced in the United States. For example, the obligation to remit money to family members abroad may heighten migrants’ existing concerns about unemployment or legal status stressors (e.g. threat of deportation), and family separation may entail the loss of important sources of social support and coping in the face of stressors experienced by migrants in the U.S.

HYPOTHESES

We expect that remittance sending, one dimension of cross-border connection, will be on balance associated with significantly lower levels of psychological distress (main effect), despite the potential for countervailing adverse impacts of the financial burden of remittance sending on mental health. We further expect that the negative effect of migration-related stressors on psychological distress will be diminished for those who send remittances across borders (interaction effect). Conversely, we expect that cross-border separation, measured by difficulty visiting family and friends abroad, will be associated with significantly higher psychological distress (main effect), and that the negative effect of immigration-related stress on psychological distress will be exacerbated for those who report having difficulty visiting family and friends abroad (interaction effect).

Given the heterogeneity of Latino migrants in the sample and the political conditions that affect migrants’ ability to make return visits and send remittances, we expect these overall patterns to differ across ethno-national subgroups. Specifically, we expect that the main and buffering effects of remittance sending will be greater for Mexican and Cuban immigrant respondents (relative to other respondents) because members of these groups are more likely to face barriers to making return trips, which may heighten the positive impact of connecting without physically returning (i.e., through remittance-sending). Finally, we expect that the main and exacerbating effects of reporting difficulty visiting home will be greater for Mexican and Cuban migrants, whose barriers to return are related to formidable geopolitical and physical barriers (at least at the time of the NLAAS survey), and smaller for Puerto Ricans and other Latinos who face more straightforward economic barriers to return. Given this context, difficulty of return may be indicative of more permanent or longer-term separation between migrants and their family members for Mexican and Cuban respondents relative to other respondents.

METHODS AND MEASURES

Data come from the 2002/2003 National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLAAS), a nationally representative in-person survey of U.S. and foreign-born Latino and Asian-Americans (Alegria et al. 2003). Despite the dramatic change in migration policy and the lives of migrant populations in the U.S. since the fielding of the NLAAS, no other population health survey to our knowledge has collected data on both the detailed cross-border social ties of immigrant populations and nuanced measures of self-reported mental health outcomes. In addition, the NLAAS is unique in that it contains a large enough sample of each major Latino subgroup, which enables us to take into account the heterogeneous nature of the Latino migrant population with stratified analyses.

The NLAAS included a multi-stage national probability sample of the non-institutionalized U.S. adult population, with supplemental samples that targeted regions with a high density of Latino and Asian households (Heeringa et al. 2004). Interviews were conducted in either English or Spanish. A total of 2554 Latinos were included in the final sample, with a response rate of 75.5%. Given that U.S.-born respondents did not answer questions about cross-border ties, we only included Latin American-born respondents (n=1630), including those born in Puerto Rico, in our analysis. We further excluded 57 respondents who volunteered that they had no family members or friends in their country of origin, for a total analytic sample of 1573.

Measures

Outcome

The dependent variable is the Kessler-10 scale of psychological distress, a 10-item scale of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Kessler et al. 2002). Respondents were asked if in the previous 30 days they experienced the following seven symptoms, with five-item responses ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time”: tired for no good reason, nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, worthless, depressed, that everything was an effort. An additional three items measured severity of symptoms, whereby respondents specified how often they felt “so nervous that nothing could calm you down,” “so restless you could not sit still”, and “so depressed that nothing could cheer you up”. When no symptoms were reported, we coded the severity items as zero, or “none of the time”. We coded items to reflect that higher scores meant higher levels of distress. The reliability coefficient for the Latino immigrant sample was α=0.94.

Immigration-related Stress

The key independent variables were generated from a 9-item scale of migration-related stress measures adapted from the Hispanic Stress Inventory (Cervantes, Padilla and Snyder 1990). A principal components analysis suggests that the 9 items load onto three factors, which we refer to as 1) migration-related family stress (felt guilty leaving family and friends in one’s country of origin; have limited contact with family and friends in country of origin), 2) legal status stress (avoid social or government agencies due to fear of deportation; avoid health services due to fear of deportation; are questioned about legal status) and 3) everyday migration stress, which include the remaining scale items (treated badly due to fair/poor English; difficult to find work due to Latino descent; less respect in U.S. as in country of origin; ; limited interaction due to fair/poor English).2 Given the skewed distribution of each domain, we created three binary measures contrasting those reporting any migration-related stress (i.e. family stress, legal status stress, or everyday migration stress) versus none. By collapsing these migration-related stress domains into three binary variables, we are able to assess how each of these domains may interact differently with measures of cross-border ties, and by ethno-national subgroup. We note that we do not use the legal status stress component in models for Puerto Rican respondents, given the very low indication of fear of deportation among this group.

Cross-border Ties and Covariates

The key moderating variables include a binary measure of whether or not respondents send money to family members in their country of origin (i.e. remittance sending), and a binary measure of whether or not respondents report difficulty visiting relatives and friends in their country of origin. For the latter measure, respondents were asked to indicate difficulty visiting on a four-item scale ranging from “very difficult” to “not difficult at all”. Responses were collapsed into a binary variable grouping those reporting that visiting was “not very” or “not at all” difficult with those reporting that visiting was “somewhat” or “very” difficult; those who had no family or friends abroad were excluded from the analysis (n = 57).

Covariates include age, gender, and two indicators of socio-economic status: less than high school education versus high school education or greater, whether or not respondents have enough money to meet basic needs, and a continuous measure of annual household income. The latter indicators are particularly important. Although it is possible that the relationship between cross-border ties and distress may be mediated by economic conditions (i.e. sending remittances or making visits home reduces economic resources, contributing to poorer mental health), economic conditions may also be an important confounder, whereby remittance-sending or difficulty visiting home may reflect nothing more than one’s economic ability to do so. We include both measures given that the indicator of annual household income does not take into account expenditures or respondents’ perceived financial burden, which may be an important predictor of both cross-border activity and psychological distress.

We controlled for time spent in the U.S. with a binary indicator of fewer than 20 years in the U.S. (the sample mean) versus 20 or more years. We controlled for citizenship status for all but the Puerto Rican sample. We control for respondent marital status, and tested other measures of family and neighborhood ties. Specifically, we tested 1) a continuous measure of neighborhood social cohesion, 2) a binary indicator of whether or not respondents migrated to the U.S. to join their family members, and 3) a measure of whether or not respondents live with at least one other family member. None of these measures improved model fit as measured by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), so we excluded them from the analysis.

Analytic Model

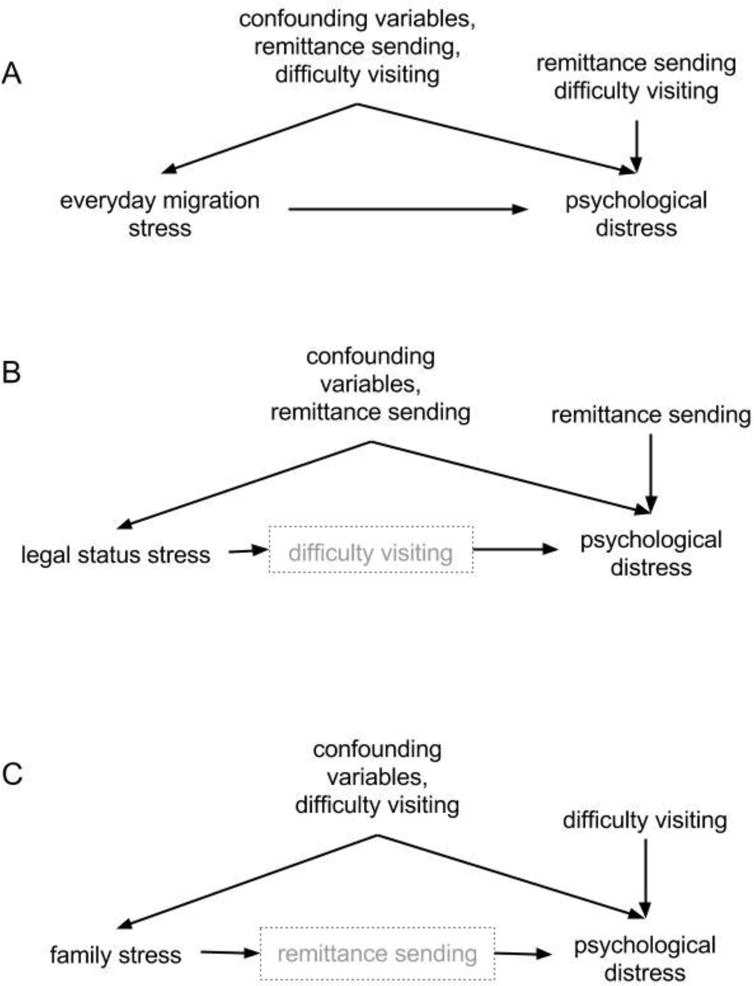

Figure 1 presents directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) (Robins 2001) that demonstrate the logic of our analyses. Panel A guides the model in which everyday migration stress is the exposure, and both measures of cross-border ties serve as potential moderators of the relationship between everyday migration stress and psychological distress.

Figure 1.

Directed Acyclical Graphs (DAGs) of relationships between immigration-related stress, cross-border lies, and psychological distress

The relationship between each of the two other dimensions of migration-related stress and possible moderating effects of cross-border ties may differ from the model depicted in Panel A. For one, while we cannot make causal inferences with our cross-sectional data, we believe that legal status stress may have an underlying causal impact on difficulty visiting home. While those who report fear of deportation are not necessarily undocumented, they may be more likely to be undocumented, hold temporary protective status or another legal status that contributes to their limited ability to visit their country of origin. Under this model, including difficulty visiting home in the regression would bias the association between legal status stress and psychological distress if difficulty visiting home is a mediator of the relationship (see DAG in Figure 1, Panel B). We therefore only consider remittance sending as a potential moderator (and confounder) of the relationship between legal status stress and psychological distress.

Similarly, migration-related family stress may have an underlying causal association with remittance-sending, given that remittance-sending may be motivated by a sense of feeling guilty about leaving one’s country of origin, and may be reflective of having limited contact with family and friends in one’s country of origin (i.e. the two components of family-related immigration stress). We therefore exclude remittance sending from these models given that it is a plausible mediator of the relationship between immigration-related family stress and psychological distress (see Figure 1, Panel C). We only include the measure of difficulty visiting home as a potential moderator of the relationship between immigration-related family stress and psychological distress.

Analyses

We estimate descriptive statistics by ethno-national subgroup; Ns are unweighted and percentages take into account the survey design, including sampling weights. All models are stratified by these four sub-groups to account for differences in the political and historical context of each of these groups. We first estimated unadjusted associations of psychological distress on the dimensions of migration-related stress, cross-border measures, and covariates, respectively. Following the DAGs in Figure 1, we then fit adjusted models with main effects of immigration-stress, cross-border ties, possible confounders, and interaction effects of immigration-stress and cross-border ties.

Given the skewed nature of the distress outcome towards lower values, we estimate generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and a log link. The exponentiated coefficients for these models have a multiplicative interpretation (Faraway 2006). For example, the exponentiated coefficient on the main effect of everyday migration stress would be the ratio of the expected distress score when everyday migration stress is experienced relative to the expected distress score when everyday migration stress is not experienced, holding all covariates constant. Analyses incorporated the complex survey design, including sampling weights and subgrouping for Latino migrant subgroups (Heeringa et al. 2004), using the –svy—package in STATA (v.13). We used multiple imputation by chained equations (30 imputed datasets) to address missing data using the –ice- package in STATA. Results across the imputed datasets were combined using Rubin’s combining rules (Rubin 1987). We accounted for multiple tests using the False Discovery Rate method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995).

Results

Table 1 presents weighted descriptive statistics for the entire sample of Latino migrants. The sample is just over 40 years on average and half are women. More than half reported having less than a high school education. Over half indicated having enough money to meet their basic needs, and the average household income was just under $40,000 per year. Almost two thirds of respondents reported experiencing any everyday migration-related stress, nearly forty percent reported any legal status stress, and 53% reported any migration-related family stress. About 40% remitted money to their relatives in their country of origin, while 57% reported difficulty visiting their family and friends in their country of origin. The mean distress score was about 14 (scale range: 10–50).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for a nationally-represenative sample of Latino immigrants (n=1573), National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), 2002/2003.

| N % | mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distress (range 10–50) | 14.6 (6.8) | |

| Immigration-related Stress | ||

| Discrimination | 1000 | (66.1) |

| Legal status stress | 463 | (39.1) |

| Family-related stress | 814 | (52.7) |

| Cross-border Ties | ||

| Remit to relatives in country of origin | 637 | (43.3) |

| Difficulty visiting family and friends | 955 | (57.3) |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||

| Age, y | 42.7 (15.6) | |

| Female | 873 | (48.3) |

| Less than a high school education | 729 | (55.6) |

| Has enough money to meet basic needs | 842 | (55.2) |

| Annual household income, dollars | 39479.5 (41339.9) | |

| Married | 1052 | (70.3) |

| Immigration factors | ||

| Twenty years or more in the U.S. | 671 | (35.6) |

| U.S. Citizen | 693 | (33.5) |

| Ethno-national Identity | ||

| Puerto Rican | 211 | (7.7) |

| Cuban | 465 | (6.5) |

| Mexican | 481 | (55.6) |

| Other Latino | 416 | (30.2) |

Notes: Ns are unweighted, percentages are weighted; n=57 foreign-born Latino respondents reported having no family or friends in their country of origin and were exlcuded from the sample.

Table 2 presents unadjusted and adjusted (main effects only) exponentiated regression coefficients for the generalized linear models of distress. Everyday migration-related stress was significantly associated with higher levels of psychological distress for Puerto Rican migrants only (exp(b): 1.20, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.37, adjusted models). Legal status stress was associated with significantly greater psychological distress for Cuban, Mexican and Other Latino migrants, (exp(b): 1.13, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.23 for Cuban migrants; 1.09, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.16 for Mexican migrants; exp(b): 1.14, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.29 for Other Latinos, all adjusted models). After accounting for multiple testing, the associations between legal status stress and psychological distress for Cuban and Mexican migrants, respectively, just reached non-significance (both p=0.05); the remaining associations between migration-related stressors and psychological distress were not significant after accounting for multiple testing. Migration-related family stress was not significantly associated with psychological distress for any of the ethno-national sub-groups.

Table 2.

Exponentiated coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for generalized linear models of psychological distress by measures of cross-border ties and migration-related stressors, National Latino and Asian American Study, 2002/2003

| Puerto Rican (n=211) |

Cuban (n=465) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||||

| Exp (b) | 95% CI | Exp (b) | 95% CI | |||||||||||

| Immigration-related Stressors | ||||||||||||||

| Everyday migration stress | 1.29 | ** | (1.12, 1.49) | 1.20 | * | (1.04, 1.37) | 1.11 | * | (1.01, 1.22) | 1.07 | (0.97, 1.19) | |||

| Legal status stress | 1.19 | ** | (1.06, 1.32) | 1.13 | ** | (1.03, 1.23) | ||||||||

| Family-related stress | 1.08 | (0.93, 1.26) | 0.99 | (0.89, 1.09) | 1.05 | (0.97, 1.14) | 1.02 | (0.96, 1.08) | ||||||

| Cross-border Ties | ||||||||||||||

| Sends remittances | 0.81 | * | (0.68, 0.96) | 0.88 | (0.74, 1.03) | 0.84 | ** | (0.75, 0.94) | 0.87 | ** | (0.79, 0.95) | § | ||

| Difficulty visiting | 1.29 | *** | (1.18, 1.42) | 1.15 | ** | (1.05, 1.26) | § | 1.06 | (0.98, 1.14) | 1.01 | (0.96, 1.06) | |||

| Socio-demographic Factors | ||||||||||||||

| Age, y | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | ** | (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.00) | |||||

| Female | 1.06 | (0.89, 1.25) | 0.95 | (0.83, 1.08) | 1.21 | *** | (1.13, 1.29) | 1.19 | *** | (1.12, 1.26) | § | |||

| Less than high school education | 1.22 | * | (1.03, 1.46) | 1.01 | (0.89, 1.15) | 1.23 | *** | (1.11, 1.36) | 1.12 | (0.99, 1.26) | ||||

| Has enough money to meet basic needs | 0.74 | ** | (0.63, 0.87) | 0.83 | * | (0.69, 0.99) | 0.85 | *** | (0.81, 0.89) | 0.94 | (0.88, 1.01) | |||

| Annual household income × $10000 | 0.98 | *** | (0.97, 0.99) | 0.99 | (0.98, 1.00) | 0.98 | *** | (0.97, 0.98) | 0.99 | ** | (0.98, 0.99) | § | ||

| Married | 0.82 | ** | (0.72, 0.94) | 0.88 | (0.77, 1.00) | 0.92 | * | (0.85, 0.99) | 0.99 | (0.91, 1.09) | ||||

| Immigration-related measures | ||||||||||||||

| Twenty years or more in the US | 1.09 | (0.97, 1.22) | 1.05 | (0.91, 1.20) | 1.06 | (0.96, 1.18) | 1.07 | * | (1.01, 1.13) | |||||

| US citizen | 0.98 | (0.88, 1.09) | 0.93 | (0.86, 1.02) | ||||||||||

|

Mexican (n=481) |

Other Latino (n=416) |

|||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||||

| Exp (b) | 95% CI | Exp (b) | 95% CI | Exp (b) | 95% CI | Exp (b) | 95% CI | |||||||

| Immigration-related Stressors | ||||||||||||||

| Everyday migration stress | 1.06 | (0.98, 1.15) | 1.02 | (0.93, 1.11) | 1.13 | ** | (1.05, 1.23) | 1.05 | (0.96, 1.15) | |||||

| Legal status stress | 1.08 | * | (1.02, 1.15) | 1.09 | ** | (1.03, 1.16) | 1.13 | (0.98, 1.31) | 1.14 | * | (1.00, 1.29) | |||

| Family-related stress | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.10) | 1.02 | (0.92, 1.12) | 1.01 | (0.92, 1.11) | 0.99 | (0.92, 1.07) | ||||||

| Cross-Border Ties | ||||||||||||||

| Sends remittances | 0.94 | ** | (0.91, 0.98) | 0.96 | (0.91, 1.02) | 0.96 | (0.84, 1.10) | 1.00 | (0.88, 1.13) | |||||

| Difficulty visiting | 1.04 | (0.98, 1.11) | 1.01 | (0.95, 1.08) | 1.13 | * | (1.00, 1.26) | 1.04 | (0.95, 1.15) | |||||

| Socio-demographic Factors | ||||||||||||||

| Age, y | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.00) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.00) | ||||||

| Female | 1.17 | *** | (1.12, 1.22) | 1.14 | *** | (1.07, 1.21) | § | 1.21 | *** | (1.14, 1.29) | 1.20 | *** | (1.13, 1.28) | § |

| Less than high school education | 1.00 | (0.91, 1.09) | 0.97 | (0.92, 1.04) | 1.15 | (0.99, 1.35) | 1.08 | (0.94, 1.25) | ||||||

| Has enough money to meet basic needs | 0.91 | * | (0.84, 0.98) | 0.91 | * | (0.86, 0.98) | 0.85 | ** | (0.76, 0.94) | 0.92 | (0.84, 1.02) | |||

| Annual household income × $10000 | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.02) | 0.98 | *** | (0.97, 0.99) | 0.99 | *** | (0.98, 0.99) | § | |||

| Married | 0.90 | ** | (0.84, 0.96) | 0.91 | * | (0.84, 0.99) | 0.95 | (0.86, 1.06) | 1.01 | (0.91, 1.11) | ||||

| Immigration-related measures | ||||||||||||||

| Twenty years or more in the US | 1.01 | (0.90, 1.13) | 0.96 | (0.85, 1.08) | 1.00 | (0.87, 1.15) | 1.04 | (0.95, 1.15) | ||||||

| US citizen | 1.05 | (0.94, 1.17) | 1.08 | (0.99, 1.17) | 0.99 | (0.91, 1.08) | 1.08 | (0.96, 1.20) | ||||||

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001,

p<0.05 after accounting for multiple testing.

Notes: Adjusted models control for all immigration-related stressors, cross-border ties, socio-demographic factors and immigration-related measures. Legal status fear and citizenship status omitted for Puerto Rican migrants due to very small or zero cell sizes for some values

Sending remittances was associated with lower levels of psychological distress for all but those in the “Other Latino” group in unadjusted models: sending remittances was associated with 19% lower distress scores (exp(b): .81, 95% CI: .68, .96) for Puerto Rican migrants, 16% lower distress scores for Cuban migrants (exp(b): 0.84, 95% CI: .75, .94), and 6% lower distress scores for Mexican migrants (exp(b): .94, 95% CI: .91, .98). The association remains significant only for the Cuban migrant sample in adjusted models: sending remittances is associated with 13% lower distress scores (exp(b): .87, 95% CI: .79, .95) for Cuban migrants, and this association remains significant after accounting for multiple testing. Difficulty visiting home is associated with higher psychological distress only for Puerto Rican migrants. It is associated with 15% greater distress scores after adjusting for covariates (exp(b): 1.15, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.26), and this association was still significant after accounting for multiple testing.

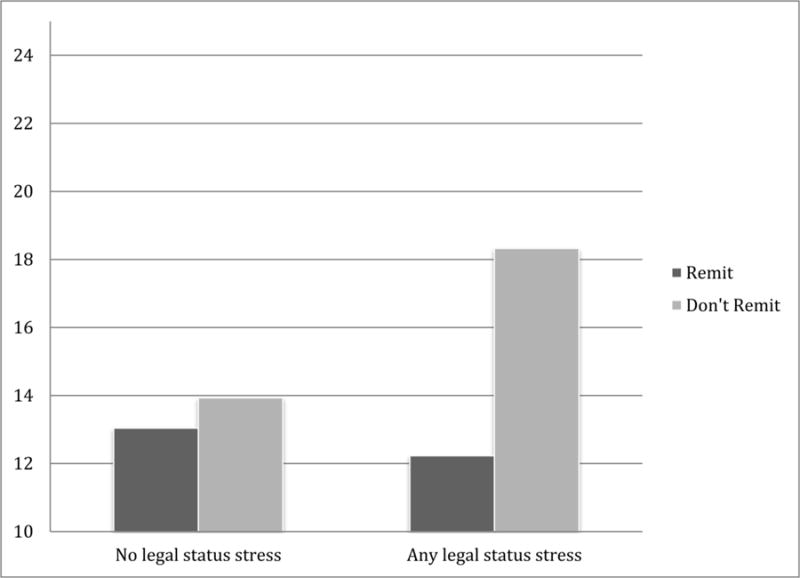

In Appendix Table A we present the adjusted interactions between dimensions of migration-related stress and cross-border ties according to the DAGs presented in Figure 1. The only significant interaction observed was between remittance sending and legal status fear among Cuban migrants. Among Cuban migrants only, remittance sending reduced the association between legal status fear and psychological distress by 29% (exp(b): .71, 95% CI: .64, .80). This interaction is presented graphically in Figure 2; this interaction term remained significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

Figure 2.

Predicted psychological distress score by migration-related legal status stress and remittance-sending for Cuban migrants (n=465)

Discussion

Our study aimed to identify main effect associations between indicators of cross-border ties, migration-related stress, and psychological distress, and subsequently examined how these cross-border ties may moderate the associations between migration-related stressors and psychological distress. The influence of cross-border ties on the mental health of immigrants has been suggested by early sociologists, but has only begun to be explored by immigrant health researchers. Conversely, recent sociological literature on transnationalism in general, and cross-border family ties in particular, has paid little attention to the role of cross-border ties in shaping health outcomes (Levitt and Jaworsky 2007).

Our findings reveal significant main effect associations between cross-border ties, domains of migration-related stress, and psychological distress for some migrant groups. After accounting for multiple testing, however, the only main effect associations that remained were between difficulty visiting home and psychological distress for Puerto Rican migrants, and between remittance-sending and psychological distress for Cuban migrants. The main effect associations between legal status stress and psychological distress just reached non-significance for Mexican and Cuban subgroups (p=.05) after accounting for multiple testing. There was little support for the hypothesis that cross-border ties moderate the relationship between migration-related stressors and psychological distress. Specifically, there was a significant interaction effect between remittance-sending and legal status stress for Cuban migrants only. The association was in the hypothesized direction: remittance sending appeared to buffer the association between legal status stress and psychological distress for this sub-group.

Remittance sending and health

The significant associations between remittance sending and psychological distress for Cuban migrants in particular confirms earlier findings related to cross-border ties and health. For example, Alcántara and colleagues (2015) found that a one percentage increase in remittance dollars sent relative to household income was associated with 20% lower odds of past-year major depressive disorder among the same nationally-representative sample of Latino migrants in the NLAAS. Torres (2013) found that parental remittance sending was associated with significantly greater odds of reporting better categories of self-reported health among second generation Latinos in Southern California. Studies have also found evidence of a relationship between giving money and other family assistance (Telzer and Fuligni 2009; Telzer et al. 2010) – which is reflected in our indicator of remittance sending – and psychological outcomes. For example, in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study, Telzer and co-authors (2010) found that Latino adolescents were observed to have reward centers in the brain activated during activities that simulated giving money to family members. While this study did not specify where money was sent (i.e. to nearby or cross-border family) it sheds light on how giving within cross-border families may have beneficial effects for Latino mental health.

Cross-border separation and health

On the other hand difficulty visiting home was a significant predictor of higher levels of psychological distress only for Puerto Rican migrants. Despite literature suggesting a link between cross-border family separation and mental health (Miranda et al. 2005), there were no independent significant associations between difficulty visiting home and psychological distress for the other migrant sub-groups. There are several possible reasons for this limited finding. The overwhelming majority of Cuban migrants noted that it would be difficult to visit their country of origin, which accurately reflects the political and historical context of the survey we used; the limited variability on this measure likely limits our ability to detect any effects. The Mexican migrant sample had lower psychological distress scores on average, and also more limited variability in these scores, which might have made it more difficult to detect significant effects of exposures or their moderators for this group. The heterogeneity of the “Other Latino” group likely makes it difficult to detect any significant associations between cross-border ties, migration-related stressors, and health. Finally, as we discuss further on, we do not know from the survey questions which family members migrants had difficulty visiting and, conversely, which family members were present in the U.S. to buffer any adverse impact of cross-border separation.

Migration-related stress and health

We found no significant associations between migration-related family stress and psychological distress, as measured by questions of feeling guilty about leaving and having limited contact with family and friends in one’s country of origin. This findings may be due to the ambiguity around which family members migrants have limited contact with or felt guilty about leaving, a limitation of the data that we expand on below. The indicator of legal status stress was significantly associated with higher levels of psychological distress for Mexican, Cuban migrants although this association dropped to marginal significance (p=0.05) for each of these two groups after adjusting for multiple testing. The association between legal status stress and psychological distress was not significant for Other Latino migrants after accounting for multiple testing. Despite similar associations between legal status stress and psychological distress, the prevalence of legal status stress was much higher among Mexican migrants (47% compared to 17% for Cuban migrants and 34% for Other Latinos migrants). The differing rates of legal status stress reflect the fact that Cuban migrants may be questioned about their legal status they cannot be deported once arrived on U.S. soil. Again, the limited variability in psychological distress scores may have made it difficult to detect significant associations even for substantial social stressors. While deportation has also impacted Central American migrant sub-groups, significant associations between legal status stress and psychological distress might be obscured by the inclusion of Central American migrants with the heterogeneous “Other Latino” group. Despite these non-significant or marginally significant associations, Latino migrants and their families have expressed heightened levels of concern about deportation–either for themselves or members of their families and communities–given the expansion of immigration enforcement efforts after the fielding of the NLAAS (Gonzalez-Barrera and Krogstad 2014; Hugo Lopez et al. 2013). More recent data on both concern about deportation and mental health outcomes is needed to assess the degree to which such concerns are impacting migrants and their family members. Nevertheless, our results suggest that even potentially protective psychological effects of cross-border giving and connection may not be enough to reduce any adverse impacts of living in fear of deportation, a stressor that may be increasingly salient for the mental well being of Latino migrants in the U.S.

There are several limitations to our study. First, it is based on cross-sectional data; as such, we were unable to address questions regarding the causal pathway between migration-related stress and cross-border social ties, respectively, with mental health outcomes. There may be a reciprocal relationship between mental health and engagement with social networks as well as family-, discrimination-, and legal status-related migration concerns. For example, individuals who experience greater psychological distress might simply withdraw interaction with family members abroad as they might do with more proximal social networks. Future studies using longitudinal data are necessary to shed light on how individuals may engage with or withdraw from cross-border social relationships as their own mental health status varies.

Second, all of the measures we used (i.e., the exposure, moderator, and outcome measures) are based on self-reports, which may result in further bias. For example, those who are significantly more distressed may be more likely to report higher levels of migration-related stress, or more challenges related to visiting one’s country of origin.

Third, the level of detail among the measures of cross-border ties is limited. That is, we do not know which family members respondents are connecting with abroad, and how intimate the relationship is between respondent and family members living across borders. We are thus unable to assess whether cross-border ties with weaker connection including friends or members of an extended family matter to the same extent or in the same ways as do closer ties for the mental health and well-being of migrants. Separation from and connection with close family members abroad, including children and parents, might have more bearing on the mental health of immigrants in the U.S.; however, future research is needed to further shed light on this issue.

Fourth, the lack of measures in the NLAAS related to economic assistance to family members or friends within the U.S. precluded analyses of the benefits of giving money across borders versus giving money in general. Another area for future research that we were not able to address in our analysis is the potential for heterogeneous effects of cross-border ties on mental health outcomes by dimensions of time in the U.S., age at migration, and age. For example, the meaning of cross-border ties and the kinds of activities immigrants engage in likely vary depending on life stage and age-specific social networks (Smith 2006).

Finally, there have been many changes in the political, economic, and social contexts of both sending and receiving countries since the NLAAS was fielded in 2002 and 2003. Cross-border ties for Mexican and some Central American migrants may increasingly be the result of families separated by the deportation of one or more members (Gonzalez-Barrera and Krogstad 2014). In addition, remittance-sending peaked in 2006, and then declined dramatically in the aftermath of the Great Recession, with initial signs of an increase after 2010 for some Latino migrant groups (Cohn, Gonzalez-Barrera and Cuddington 2013). Cross-border social ties may have become increasingly common for some migrant groups since the survey. For example, recent changes toward normalized relations between the United States and Cuba hold the promise of increasing cross-border communication and visits (Baker 2014). More generally, the increasingly widespread use of Internet technology over the last decade as well as declines in the cost of long-distance calls and the expanded availability of low-cost video may have allowed for increased cross-border connection (Bacigalupe and Cámara 2012). Thus, the current results should be interpreted with caution given these changes in the political and social contexts of both immigrant-sending and immigrant-receiving countries.

Despite these limitations, our study moves the field of immigrant health forward by considering the role of cross-border ties as social determinants of migrant mental health, and the potential for cross-border connections to serve as sources of both risk and resilience for migrant populations. Our findings also contribute to the broader sociological literature on cross-border ties by highlighting the potential for cross-border ties to influence mental health, a dimension that merits further consideration in future scholarship. Our work might be extended by future analyses that consider heterogeneity in the relationship between cross-border ties and mental health by migrants’ economic conditions. For example, while remittance sending might be protective of mental health in general these protective effects may be attenuated for migrants who report significant economic strain.

Conclusion

Researchers have long been interested in factors that contribute to the resilience of migrant populations. Despite an extensive focus on family ties, there has been very little exploration of where family members are located, and whether or not the locality of these ties matters for health and well-being. The importance of identifying risk and resilience factors for the mental health of immigrants is critical, as the flow of international migrants is expanding dramatically. If migration has the potential to be disruptive to social networks, with adverse consequences for mental health, knowledge about how ties are maintained across borders can inform policy and intervention. Our study fills an important gap in the field by providing evidence of the conditions under which cross-border ties serve as sources of resilience for some Latino migrants. We encourage future health surveys of migrant populations to include measures of cross-border ties. Future qualitative and experimental research would also help elucidate some of the mechanisms linking cross-border ties to mental health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

J. M.T. and K.E.R. were funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholars program at the UCSF/UC Berkeley site at the time of the study. C.A was supported by HL115941-01S1 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. This paper was presented at the 2015 meeting of the Population Association of America and a conference on migration and health at the University of California, Los Angeles (March 2015).

Biographies

Jacqueline M. Torres is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholar at the Center for Health and Community at University of California, San Francisco, and the School of Public Health at University of California, Berkeley. Her research includes work on the circumstances of migration, cross-border ties, and health outcomes for immigrants to the United States and in Mexico. Her work has been published in the American Journal of Public Health and Social Science & Medicine, among others.

Carmela Alcántara is Assistant Professor of Social Work at Columbia University School of Social Work. Her interdisciplinary program of research integrates frameworks and methodologies from psychology, public health, social work, and medicine to understand how structural and social factors affect mental health, cardiovascular health, and sleep particularly in racial/ethnic and immigrant communities. Her work has been published in the American Journal of Public Health, SLEEP, Social Science & Medicine, and the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, among others.

Kara E. Rudolph is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholar at the Center for Health and Community at University of California, San Francisco, and the School of Public Health at University of California, Berkeley. Her research applies causal inference methods to the study of social and contextual influences on mental health and substance use in disadvantaged urban areas of the United States. Her work has been published in the American Journal of Epidemiology and the American Journal of Public Health, among others.

Edna Viruell-Fuentes is Associate Professor of Latina/Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her interdisciplinary, multi-methods research examines the structural contexts of Latina/Latino and migrant health from a transnational perspective. Her works has been published in Social Science & Medicine, the American Journal of Public Health, Ethnicity & Health, and the Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, among others. She is the recipient of the University of Illinois’ Helen Corley Petit Award for her exemplary record.

Appendix Table A.

Exponentiated coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for generalized linear models of psychological distress by measures of cross-border ties and migration-related stressors, 2002/2003 National Latino and Asian American Study.

| Puerto Rican (n=211) | Cuban (n=465) | Mexican (481) | Other Latino (n=416) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp (b) | 95% CI | Exp (b) | 95% CI | Exp (b) | 95% CI | Exp (b) | |||||

| Everyday migration stress | 1.20 | (.99, 1.46) | 1.09 | (.95, 1.24) | 1.08 | (.93, 1.25) | 1.10 | (.97, 1.24) | |||

| Remittances | 1.00 | (.86, 1.16) | .94 | (.82, 1.06) | 1.05 | (.94, 1.16) | 1.05 | (.90, 1.22) | |||

| Difficulty visiting | 1.05 | (.86, 1.27) | 1.00 | (.89, 1.11) | 1.02 | (.94, 1.11) | 1.07 | (.91, 1.27) | |||

| Remittances* everyday migration stress | .77 | (.57, 1.03) | .87 | (.74, 1.03) | .90 | (.78, 1.04) | .94 | (.83, 1.05) | |||

| Difficulty visiting* everyday migration stress | 1.16 | (.86, 1.55) | 1.07 | (.90, 1.27) | 1.03 | (.88, 1.19) | 1.00 | (.84, 1.19) | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Legal status stress | – | – | 1.31 | *** | (1.20, 1.44) | 1.13 | * | (1.03, 1.27) | 1.24 | (.95, 1.61) | |

| Remittances | – | – | .94 | (.86, 1.01) | .99 | (.92, 1.07) | 1.05 | (.96, 1.14) | |||

| Remittances* legal status fear | – | – | .71 | *** | (.64, .80)§ | .95 | (.83, 1.09) | .88 | (.66, 1.17) | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Family-related migration stress | 1.05 | (.91, 1.22) | 1.06 | (.91, 1.24) | 1.10 | (.98, 1.23) | 1.08 | (.94, 1.25) | |||

| Difficulty visiting | 1.29 | ** | (1.10, 1.52) | 1.03 | (.94, 1.13) | 1.09 | (.98, 1.22) | 1.14 | (.97, 1.35) | ||

| Difficulty visiting* family-related migration stress | .85 | (.62, 1.16) | .97 | (.78, 1.20) | .90 | (.77, 1.04) | .87 | (.71, 1.08) | |||

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

p<0.05 after accounting for multiple testing. Note: Controlling for age, gender, educational attainment, annual household income, subjective economic status, marital status, citizenship status and years in the U.S.

Footnotes

Exposure to migration-related stressors has been linked to poorer mental health for Latinos in the U.S., and may contribute to the erosion of any initial health advantages that Latino immigrants have over their U.S.-born counterparts (Cook et al. 2009; Torres and Wallace 2013).

We note that the domain of everyday migration stress includes items that reflect discrimination, or unfair treatment, as well as circumstances related to linguistic, social, and occupational integration. Referring to this domain as entirely related to discrimination would be inaccurate; it would be equally inaccurate to refer to the domain as one of “acculturative” stress as has been common in the immigrant health literature, and debated elsewhere (Torres and Wallace 2013). We therefore labeled this domain ‘everyday’ migration stress to encompass the broad range of included items.

Contributor Information

Jacqueline M. Torres, UC San Francisco, Center for Health and Community, 3333 California Street, San Francisco, CA.

Carmela Alcántara, Columbia University, School of Social Work, 622 W 168th Street, PH-9, Room 9-319, New York, NY 10032.

Kara E. Rudolph, UC Berkeley, School of Public Health.

Edna A. Viruell-Fuentes, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Department of Latina/Latino Studies.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia Dolores, Sanchez-Vaznaugh Emma V, Viruell-Fuentes Edna A, Almeida Joanna. Integrating Social Epidemiology into Immigrant Health Research. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(12):2060–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara Carmela, Chen Chih-Nan, Alegria Margarita. Do Post-Migration Perceptions of Social Mobility Matter for Latino Immigrant Health? Social Science & Medicine. 2014;101:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara Carmela, Chen Chih-Nan, Alegria Margarita. Transnational Ties and Past-Year Major Depressive Episodes Among Latino Immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015;21(3):486–95. doi: 10.1037/a0037540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara Carmela, Molina Kristine M, Kawachi Ichiro. Transnational, Social, and Neighborhood Ties and Smoking Among Latino Immigrants: Does Gender Matter? American Journal of Public Health. 2014;105(4) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria Margarita, Jackson James S, Kessler Ronald C, Takeuchi David. In: Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES), 2001–2003 [United States] Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, editor. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupe Gonzalo, Cámara Maria. Transnational Families and Social Technologies: Reassessing Immigration Psychology. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2012;38(9):1425–38. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Peter. U.S. to Restore Full Relations with Cuba, Erasing a Last Trace of Cold War Hostility. The New York Times 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Yoav, Hochberg Yosef. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Carling Jørgen. Scripting Remittances: Making Sense of Money Transfers in Transnational Relationships. International Migration Review. 2014;48(s1):s218–s62. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes Richard C, Padilla Amado M, de Snyder Nelly Salgado. Reliability and Validity of the Hispanic Stress Inventory. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12(1):76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudry Ajay, Capps Randy, Pedroza Juan Manuel, Castañeda Rosa Maria, Santos Robert, Scott Molly M. Facing our Future: Children in the Aftermath of Immigration Enforcement. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn D’Vera, Gonzalez-Barrera Ana, Cuddington Danielle. Remittances to Latin America Recover – But Not to Mexico. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cook Benjamin, Alegria Margarita, Lin Julia Y, Guo Jing. Pathways and Correlates Connecting Latinos’ Mental Health With Exposure to the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2247–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius Wayne. Death at the Border: Efficacy and Unintended Consequences of U.S. Immigration Control Policy. Population and Development Review. 2001;27(4):661–85. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton Michael J, Goldman Noreen, Teruel Graciela, Rubalcava Luis. Migrant Networks and Pathways to Child Obesity in Mexico. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(5):685–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreby Joanna. U.S. Immigration Policy and Family Separation: The Consequences for Children’s Well-Being. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;132:245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duany Jorge. To Send or Not to Send: Migrant Remittances in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2010;630(1):205–23. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein Susan. Immigration, Remittances, and Transnational Social Capital Formation: A Cuban Case Study. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2010;33(9):1648–67. [Google Scholar]

- Faraway Julian J. Extending the Linear Model with R: Generalized Linear, Mixed Effects and Nonparametric Regression Models. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Reanne. International Migration and Infant Health in Mexico. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2005;7(1):11–22. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-1386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garip Feliz. Repeat Migration and Remittances as Mechanisms for Wealth Inequality in 119 Communities from the Mexican Migration Project Data. Demography. 2012;49:1335–60. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barrera Ana, Krogstad Jens Manuel. US Deportations of Immigrants Reach Record High In 2013. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Trends Project; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz Joseph G, Quandt Sara A, Early Julie, Tapia Janeth, Graham Christopher A, Arcury Thomas A. Leaving Family for Work: Ambivalence and Mental Health Among Mexican Migrant Farmworker Men. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2006;8(1):85–97. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-6344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handlin Oscar. The Uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations that Made the American People. New York, NY: Grosset and Dunlap; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa Steven G, Wagner James, Torres Myriam, Duan Naihua, Adams Terry, Berglund Patricia. Sample Designs and Sampling Methods for the Collaborative Pyschiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):221–40. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman Josiah M, Núñez Guillermina G, Talavera Victor. Healthcare Access and Barriers for Unauthorized Immigrants in El Paso County, Texas. Family and Community Health. 2009;32(1):4–21. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000342813.42025.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton Sarah. A Mother’s Heart is Weighted Down with Stones: A Phnomenological Approach to the Experience of Transnational Motherhood. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2009;33(1):21–40. doi: 10.1007/s11013-008-9117-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo Lopez Mark, Taylor Paul, Funk Cary, Gonzalez-Barrera Ana. On Immigration Policy, Deportation Relief Seen As More Important Than Citizenship: A Survey of Hispanics and Asian Americans. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center: Hispanic Trends; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries Niamh, Brugha Ruairí, McGee Hannah. Sending Money Home: A Mixed-Methods Study of Remittances by Migrant Nurses in Ireland. Human Resources for Health. 2009;7(66) doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Lei, Wen Ming, Fan Jessie X, Wang Guixin. Trans-local Ties, Local Ties and Psychological Well Being Among Rural-to-Urban Migrants. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(2):288–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn Joan R, Pearlin Leonard I. Financial Strain Over the Life Course and Health Among Older Adults. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2006;47(1):17–31. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi Ichiro, Berkman Lisa F. Social Ties and Mental Health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–67. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ron C, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-LT, Walters EE, Zaslavsky M. Short Screening Scales to Monitor Population Prevalences and Trends in Non-Specific Psychological Distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–76. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt Peggy, Jaworsky Nadya B. Transnational Migration Studies: Past Developments and Future Trends. Annual Review of Sociology. 2007;33:129–56. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie Sean, Menjívar Cecilia. The Meanings of Migration, Remittances and Gifts: Views of Honduran Women who Stay. Global Networks. 2011;11(1):63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar Cecilia. Living in Two Worlds? Guatemalan-Origin Children in the United States and Emerging Transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2002a;28(2):531–22. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar Cecilia. The Ties That Heal: Guatemalan Immigrant Women’s Networks and Medical Treatment. International Migration Review. 2002b;36(2):437–66. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda Jeanne, Siddique Juned, Der-Martirosian Claudia, Belin Thomas R. Depression Among Latina Immigrant Mothers Separated From Their Children. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(6):717–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski Krysia N. Coping with Perceived Discrimination: Does Ethnic Identity Protect Mental Health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):318–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney-Day Norah E, Alegria Margarita, Sribney William. Social Cohesion, Social Support, and Health Among Latinos in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(2):477–95. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Cohn D’Vera. Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2014. Unauthorized Immigrant Totals Rise in 7 States, Fall in 14. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney Jean S. Ethnic Identity in Adolescents and Adults: A Review of Research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(3):499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro. Migration, Development, and Segmented Assimilation: A Conceptual Review of the Evidence. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2007;610:73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Rumbaut Ruben G. Immigrant America: A Portrait. Oakland, CA, USA and London, UK: University of California Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Fernando I, Guarnaccia Peter J, Mulvaney-Day Norah, Lin Julia Y, Torres Maria, Alegria Margarita. Family Cohesion and Its Relationship to Psychological Distress Among Latino Groups. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30(3):357–78. doi: 10.1177/0739986308318713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins James M. Data, Design, and Background Knowledge in Etiologic Inference. Epidemiology. 2001;12(3):313–20. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Donald B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Carolyn, Meisenhelder Janice Bell, Ma Yunsheng, Reed George. Altruistic Social Interest Behaviors are Associated with Better Mental Health. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(5):778–85. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000079378.39062.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Robert C. Mexican New York: Transnational Lives of New Immigrants. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Soehl Thomas, Waldinger Roger. Making the Connection: Latino Immigrants and their Cross-Border Ties. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2010;33(9):1489–510. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer Eva H, Fuligni Andrew J. Daily Family Assistance and the Psychological Well Being of Adolescents from Latin American, Asian, and European Backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):1177–89. doi: 10.1037/a0014728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer Eva H, Masten Carrie L, Berkman Elliot T, Lieberman Matthew D, Fuligni Andrew J. Gaining While Giving: An fMRI Study of the Rewards of Family Assistance among White and Latino Youth. Social Neuroscience. 2010;5(5):508–18. doi: 10.1080/17470911003687913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits Peggy A. Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52(2):145–61. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas William I, Znaniecki Florian. The Polish Peasant in Europe and America. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press; 1918–1919 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Torres Jacqueline M. Cross-border Ties and Self-Rated Health Status for Young Latino Adults in Southern California. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;81:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres Jacqueline M, Wallace Steven P. Migration Circumstances, Psychological Distress, and Self-Rated Physical Health for Latino Immigrants in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(9):1619–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres Lucas, Ong Anthony D. A Daily Diary Investigation of Latino Ethnic Identity, Discrimination, and Depression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(4):561–86. doi: 10.1037/a0020652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor Adriana J, Updegraff Kimberley A. Latino Adolescents’ Mental Health: Exploring the Interrelations among Discrimination, Ethnic Identity, Cultural Orientation, Self-Esteem, and Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(4):549–67. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes Edna A. “My Heart is Always There”: The Transnational Practices of First-Generation Mexican Immigrant and Second-Generation Mexican American Women. Identities-Global Studies in Culture and Power. 2006;13(3):335–62. [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes Edna A, Miranda Patricia Y, Abdulrahim Sawsan. More Than Culture: Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(12):2099–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes Edna A, Schulz Amy J. Toward a Dynamic Conceptualization of Social Ties and Context: Implications for Understanding Immigrant and Latino Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2167–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes Edna A. Beyond Acculturation: Immigration, Discrimination, and Health Research Among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(7):1524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger Roger. The Cross-Border Connection: Immigrants, Emigrants, and Their Homelands. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yip Tiffany, Gee Gilbert T, Takeuchi David T. Racial Discrimination and Psychological Distress: The Impact of Ethnic Identity and Age Among Immigrant and United States-Born Asian Adults. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(3):787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]