Abstract

Background: Focus groups are often used to involve families as codesigners of weight management interventions. Focus groups, however, are seldom designed to elicit families' strengths and positive experiences. The purpose of this study was to describe the use of the Appreciative Inquiry process in the conduct of focus groups to engage families in the design of a weight management intervention for adolescents.

Methods: A convenience sample of 44 parents (84% female; 82% minority) of adolescent children with a BMI ≥ 85th percentile, who were in the 6th–8th grade in a large urban school, participated in focus groups designed to elicit family-positive experiences and strengths regarding healthy living. A structured set of questions based on the Appreciative Inquiry process was used in the focus groups. Analyses consisted of the constant comparative method to generate themes.

Results: Parent-positive perceptions regarding their family's healthy living habits were reflected in five themes: (1) Having healthy children is a joy; (2) Becoming healthy is a process; (3) Engaging in healthy habits is a family affair; (4) Good health habits can be achieved despite obstacles; and (5) School, community, and social factors contribute to their family's health habits. Parents generated ideas to improve their families' health.

Conclusions: Focus groups based on the Appreciative Inquiry process were found to be a useful approach to discover features that are important to low-income, urban-living parents to include in an adolescent weight management program. Recommendations for designing and conducting focus groups based on the Appreciative Inquiry process are provided.

Keywords: : adolescent weight management, appreciative inquiry, focus groups, intervention design, obesity

Introduction

Effective interventions to address childhood obesity are being sought to improve the current health and decrease the likelihood of future health problems in these children.1,2 Weight management is especially problematic in urban, low-income families, and effective family- and community-focused interventions for the treatment of obesity in economically disadvantaged youth remain elusive.2 Hearing first-hand from families about their approaches to achieving healthy weights is one way to design interventions for this population that comprised features that will be useful and engaging for them. Focus groups with target populations of interventions have been an effective qualitative method to develop new interventions.

Historically, focus group research with parents and children has been designed to elicit insight into specific barriers or perceived obstacles to behavior change and engagement in weight management interventions,3–5 including sociocultural challenges,6,7 beliefs, and attitudes that may interfere with or enhance behavioral changes.8,9 Although focus groups have been used successfully to assess the benefits/barriers associated with behavior change approaches, they seldom are designed to determine individuals' and families' strengths and positive experiences.

Weight management interventions that are built on families' strengths and positive experiences may be more effective than those built to overcome barriers10 in that, they may be more culturally acceptable and feasible for incorporation into family life. In line with the growing body of literature on the effectiveness of using an asset-based approach to activate individuals to make behavior change,11,12 our team conducted focus groups designed to elicit the strengths and positive experiences of parents of overweight/obese adolescents regarding the healthy living behaviors in their family.

As part of engaging the families as codesigners of a weight management intervention for adolescents, we used Appreciative Inquiry methodology in focus groups to identify parent perceptions of what they were doing right, their individual values, positive experiences, and dreams for healthy living in their families.

Appreciative Inquiry

Appreciative Inquiry, shown to successfully promote change in organizations,13–15 has been proposed as a new approach to health behavior change.16 Appreciative Inquiry emphasizes an affirmative process that focuses on the positive—on fostering change based on tapping into an individual's core values and peak experiences.15,17 It is the study of what activates human systems to function at their best. Appreciative Inquiry posits that instead of solving problems, emphasis is placed on what is going right. That something right is then built upon to do more right. It is a process in which positive change is facilitated through energized and creative images of possibility based on strengths.15,18 Table 1 lists the assumptions of the Appreciative Inquiry process.

Table 1.

Assumptions of the Appreciative Inquiry Process

| Assumptions of appreciative inquiry |

| • In every human situation, something works |

| • What we focus on, becomes our reality |

| • The language we use shapes our reality. The act of asking questions influences the outcome in some way |

| • People have more confidence going into the future (unknown) when they carry forward parts of the present (known) |

| • If we carry parts of the past into the future, they should be what are best about the past |

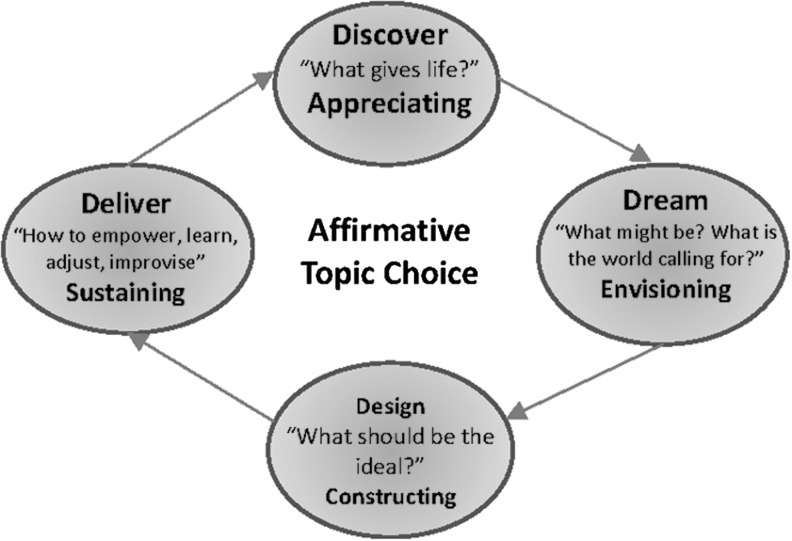

The Appreciative Inquiry process uses the four-dimensional (4D) cycle as its basic framework (Fig. 1).19 A positive core that exemplifies energy, enthusiasm, commitment, and action is the starting point. The first phase, Discovery, focuses on identifying “the best of what is” and “what gives life” to an organization (in this case, a family). In small group interviews, questions are used to promote positive success stories, enrich those images, enhance dialogue, and bring positive attributes into focus. In the second phase, Dream, questions focus on envisioning “what might be.” The group explores hopes and dreams and are encouraged to dream beyond the boundaries of what has been in the past and instead envision big, bold future possibilities.

Figure 1.

The appreciative inquiry 4D process. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. From (Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change), copyright© (2005) by (Cooperrider DL, Whitney, DK), Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., San Francisco, CA.15 All rights reserved. www.bkconnection.com. 4D, four-dimensional.

In the third phase, Design, participants explore and make choices about “what should be,” developing statements that describe the ideal. In the final phase, Deliver, sustainment of commitments for change is a focus. The focus groups described herein were designed to address the Discover and Dream phases of the 4D Cycle. The purpose of this article is to describe the use of Appreciative Inquiry for the conduct of focus groups to engage low-income, urban families in the design of a weight management program for adolescents. We describe parents' descriptions regarding healthy living that arose from focus groups using an Appreciative Inquiry approach and examples are provided of how the family-positive experiences and strengths learned in the focus groups were used in the design of a weight management program for adolescents and their families.

Materials and Methods

Sample

The convenience sample consisted of 44 parents/guardians (hereafter referred to as parents) of urban adolescent children with a BMI in the 85th percentile or higher, who were in the 6th, 7th, or 8th grade of the Cleveland Municipal School District. Parents were aged 29–85 years (mean = 43; SD = 11.9); 84% were female. Sixty-four percent self-identified as African American, 18% as White, and 16% as Hispanic; 41% were married and the average household size was 4.6 people. Parents' education level ranged from 7 to 16 years of school completed, with a mean of 12.4 (SD = 1.9).

Procedures

Focus groups were conducted during Spring 2011 following human subjects approval of the study protocol by the Institutional Review Board. The overall purpose of the focus groups was to engage parents of middle school, low-income urban youth as codesigners of a weight management intervention. Parents were recruited by telephone from a list of children participating in the We Run This City Youth Marathon Program, a local YMCA program conducted in the Cleveland school district.20

Potential participants were included in the study if they were parents of children in the 6th, 7th, or 8th grade of the Cleveland Municipal School District, with a BMI in the 85th percentile or higher as determined by trained study personnel in a school obesity screening program. Participants were invited to attend a series of two focus group sessions 1 month apart held in a local YMCA. All, but one parent, attended both sessions. Parents provided written informed consent and completed demographic data during their first group session and engaged in a discussion in which a structured discussion guide was used consisting of a set of questions based on the Appreciative Inquiry process (Table 2). Sessions were led by project staff who were given brief training in the philosophy and methods of the Appreciative Inquiry process.

Table 2.

Appreciate Inquiry Questions Used in Focus Groups

| 1. Describe a time when you felt really good about the health of your child and his or her healthy living habits |

| • What about this experience made it good? What did you appreciate about it? |

| • What makes you feel proud about this? |

| • What was it about you that made this happen? |

| • What was it about others that made this happen? |

| • What other factors in the environment or situation supported this positive experience? |

| • Was there an aspect of your routines that supported this positive experience? |

| • What do you think caused these good experiences? |

| 2a. Imagine a world where everyone could be in charge of their own health and care. What are the most important things you would need to take care of your own and your family's health? |

| 2b. Imagine that you live in a truly health community. What would be different from the way things are now? |

| • What role do you see for yourself? |

| • What steps could your community take to ensure a healthy future? |

| 3. If I were to give you three wishes that could be used to improve your family's healthy living, what would those three wishes be? |

| • What things would need to be in place for those wishes to come true? |

| • What would you do? |

| • What would others in your life need to do? |

Data were collected using digital recordings and observer notes. Each focus group session lasted 2 hours, consisting of 6–15 participants. Transportation was provided; participants received a $50 money order for their participation in each session. A total of eight focus group sessions were conducted. In the first focus group session, parents were asked to relate their high points of and successes in raising a healthy child, as well as to describe their ideas of the ideal healthy living environment and community. In the second focus group session, participants reviewed a summary of their suggestions from the first focus group session and assisted the study team to use those suggestions to design specific features to be incorporated into a weight management program for adolescents and their families.

Analyses

Modified thematic qualitative analyses21 of the focus group transcripts were conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher external to the study team and a coder within the study team. Themes were derived from each segment using coding, clustering, and categorizing.22 Differences in coding between the two coders were adjudicated through discussion. The primary themes and subthemes were identified for each question. Selected quotes were dispersed throughout the summaries to support and vivify some of the themes and related findings. To protect anonymity of the participants, the names were changed to pseudonyms. In the second focus group session, participant reviews of the findings from the first focus group session served to establish credibility of the findings.23,24

Results

Question 1. “Describe a time when you felt really good about the health of your child and his or her healthy living habits.”

Parental perceptions of what they feel good about and are proud of regarding their child's health and healthy living habits are reflected in five themes: (1) having healthy children is a joy; (2) becoming healthy is a process; (3) engaging in healthy habits is a family affair; (4) good health habits can be achieved despite obstacles; and (5) school, community, and social factors contribute to their child's health habits. Examples of parents' expressions reflecting these themes are provided below.

Having Healthy Children Is a Joy

Most parents stated that they were simply happy that their children were engaged in healthy activities. The children were engaged in organized sports at school, including softball, ice skating, football, volleyball, basketball, martial arts, the YMCA, taking walks or walking to school, or exercising using the Wii or the treadmill. Parents were proud of their children's involvement in physical activities. One mother proudly shared that her children did not have any major illnesses and had never been hospitalized. Another parent conveyed that although there were multiple health problems in her family and she also had health problems, she was relieved that her child was healthy, “…when you are sitting around and you sick all the time, to see somebody else (her son) is well, it makes me feel good.”

Becoming Healthy Is a Process

The parents witnessed that good health habits were acquired by children over time. Although the rationale for becoming healthy varied, several youth took the initiative to establish good health habits on their own. For example, Darrel requested to walk, rather than be driven to school. He began drinking water, rather than soda, even when offered soft drinks by family members. Another male child of a participant was described as becoming increasingly aware of changes in his body and concerned about his appearance and taking matters into his own hands by eliminating snacks.

Two parents, who described their daughters as “lazy,” were pleasantly surprised when their daughters decided, on their own, to become involved in the YMCA marathon program. One parent reacted to her daughter's decision to run, “You? For real!!!? I want to see this …! I'm gonna be the main one in the stands just rooting you on!”

The support and encouragement of parents played a significant role in helping the children use good health habits. For example, Barbara's daughter mimicked her health habits. Barbara ran 5 miles a day and lifted weights. Her daughter soon followed suit by walking with her mother. Other parents used other strategies to persuade their child to engage in healthy habits, including replacing unhealthy foods with healthy ones, talking to them about family history, and simply encouraging them and supporting them to make healthy choices. They encouraged them by attending their child's sporting events, serving as coaches in their child's team, and rooting for their child from the stands. One parent's words, “It's a cycle. As you root for your family, they root for you.”

Engaging in Healthy Habits Is a Family Affair

Family routines and rituals seemed to have a positive impact on establishing good health habits. Several parents indicated that eating together as a family was very important. Dinner time was an established, predicted, and pleasant event, in which family members could regroup as well as share experiences of the day. Other family routines were centered on outside activities. One family took walks together after dinner. Still another family maintained a garden. Also, to insure that good eating habits were established, one parent regularly took her son grocery shopping. Together they read labels and ingredients on products and selected nutritious food, while also allowing him to select other foods he liked.

Several families worked out together. As one mother attempted to lose weight after giving birth, her entire immediate family joined her in the effort. Part of family involvement was parent monitoring the child's health habits. One parent attended some of the practices and training sessions to make sure the program was safe for her children. Another set of parents was able to observe their child in action as they served as coaches for their child's softball team.

Good Health Habits Can Be Achieved Despite Obstacles

Several of the children had health conditions that presented challenges in the quest for establishing and maintaining good health habits. Parents were optimistic and proud of their children's resilience and self-directedness when faced with limitations and challenges that could have interfered with their participating in healthy activities. For example, one mother whose children had sickle cell anemia allowed them to participate in the We Run This City marathon program and reported that their involvement boosted their self-esteem.

Two other parents indicated that they had children with developmental delays who lost weight and had improved health habits after participating in the We Run the City marathon. Parents also discussed the challenges of raising a child with asthma and diabetes. Despite these conditions, these children were involved in a number of sports and other activities.

School, Community, and Social Factors Contribute to Their Child's Health Habits

Parents described schools, neighborhood and community activities, and social media as influencing their children's engagement in healthy behaviors. Parents believed that school teachers were often instrumental in conveying health-conscious messages and encouraging their children to become more physically active. Participants also described that the neighborhood can have an impact. The existence of neighborhood parks, fields, and swimming pools was described as being important for families to engage in outdoor activities.

The pros and cons of computer use and social media were evident as parents reflected on their child's health habits. One parent contrasted the pleasant memories of her childhood playing outdoors with the current impact of technology on children's physical activity. She was dismayed by the number of those who merely “sit in front of a screen all of the time.” Similarly, another parent was concerned that her daughter was not as active as she had been a few years ago: “She doesn't like sports. …the phone and the Facebook, that's it.” Other parents were pleased with their child's use of computers to engage them in exercise: “They (her son and his friends) come home from school and they go up there and play that Wii sport.”

Question 2a. Imagine a world where everyone could be in charge of their own health and care. What are the most important things you would need to take care of your own and your family's health?

Question 2b. Imagine that you live in a truly healthy community. What would be different from the way things are now? What role do you see for yourself? What steps could your community take to ensure a healthy future?

Parents described several images of what they thought would support healthy living in families and constitute a healthy community. Several parents asserted that access to optimal and affordable healthcare was extremely important. Parents described money as being core for taking care of the health of their family. Parents wanted better food choices at home and in the schools.

While one parent expressed the need for affordable healthy food (priced within the family budget), another stated that there is a need for acquiring a taste for healthy food. Exercise was also high on the list. Participants stated that their family could benefit from having a workout facility or a home gym (preferably equipped with music and videos), a swimming pool, tennis courts, or a soccer field. One parent hoped for the eradication of a specific childhood disease: “…that bit disease…PS3's and PS2's (X Box and computers), the screen disease.”

Others indicated that stress reduction was important. More than one parent yearned for “more time” and others felt that vacations were important. Another emphasized the significance of mental, as well as physical health. The desire for positive role models for their children was also stated. One parent said that it would be useful to her to have more support in her parenting role, particularly when attempting to sustain good health habits: “I need someone to lead me up.” Another parent stated that she wanted a “scanner” to thoroughly check out her family to make sure they were all healthy. Finally, one parent said that in addition to having good health habits, love and care were critical.

In response to the question of living in a truly healthy community, parents expressed the need for safer communities and more community resources, including readily accessible and affordable healthy food, healthy restaurants, free fruits and vegetables, community gardens, health bars, bike and walking trails, and local parks. Others stated that a truly healthy community would have no liquor stores, no bars, and no manufacturing of any kind of cigarettes or tobacco products.

One parent stated that a healthy community would have “ambassadors of mental health.” She went on to describe that “some inner city youth are angry and don't know why.” Having “mandatory classes for children to learn how to be respectful” would enhance the children's capacity to become good citizens as they developed. Others felt that “having more community gatherings could also contribute to the health of a community.” Finally, one parent asserted that the essence of a truly healthy community was “all residents would be health conscious.”

Question 3. If I were to give you three wishes that could be used to improve your family's healthy living, what would those three wishes be? What things would need to be in place for those wishes to come true? What would you do? What would others in your life need to do?

Table 3 provides a list of wishes expressed by parents regarding ways to improve their families' healthy living. These focused predominately on environmental and social factors such as the cost of healthcare and healthy foods, neighborhood safety, and the availability of health-promoting community resources. Parents also described roles they would assume in creating and maintaining a healthy community, including community healer, caregiver, village mother, advocate, activist, educator, and ambassador.

Table 3.

Parent's Wishes To Improve the Health of Their Family

| Parents' wishes |

| • Access to optimal and affordable healthcare |

| • Affordable healthy food |

| • Safer communities (end violence) |

| • Knock down boarded-up houses |

| • Good health would be automatic |

| • Reduced stress |

| • More time |

| • Reduce number of fast food restaurants |

| • Wealth should be shared among the people |

| • More community resources |

| • Better education |

| • Eliminate prepackaged food in cafeterias |

| • Reduce food advertisements and commercials |

Use of Information Learned from Focus Groups To Inform an Adolescent Weight Management Intervention

Table 4 describes the key points learned from the Appreciative Inquiry-based focus groups and their use in the design of a weight management intervention for urban adolescents and their families. Building on the positive experiences and dreams of the parents, specific features were included in the program to promote a family-centered approach to building healthy habits, provide opportunities for parents to show their pride for and cheer on their kids, keep children's interest in learning about and engaging in a healthy living, participate in community activities, and sustain behavior change.

Table 4.

Key Insights from Appreciative Inquiry Focus Groups and How They Were Used in Intervention Design

| Key insights | IMPACT intervention design elements |

|---|---|

| Building healthy habits is a family affair | • All members of the family invited to all intervention sessions |

| • Everyone in the family given an opportunity to try new activities (e.g., Salsa dancing, rock wall climbing) | |

| • Healthy cooking classes included information on how to cook together as a family | |

| • Family group social activities provided, such as bowling, Hip Hop, and roller skating | |

| Providing opportunities for parents to “cheer” for their kids | • Rock wall climbing, bowling |

| • Monthly Healthy Living Challenge contest | |

| • Training for We Run This City Youth Marathon | |

| • iPad Movie shows created by children | |

| • Graphs of weight loss over time | |

| Keeping children's interest in the intervention is important | • Variety of iPad games included in the intervention to aid in learning new concepts |

| • Use of warm-up games to start all sessions | |

| • Active sessions, such as African dancing | |

| • Each child created an iPad Healthy Living Movie | |

| • Each child used a camera to take pictures that represent what being healthy means to them (PhotoVoice) | |

| Participating in community activities | • Healthy Choices Grocery Shopping Tour in participants' local neighborhood |

| • Passport to a Healthier Family, a book of community activities for the family to record their participation in a weekly (contest) | |

| • Healthy Choices Fast Food Tour in participants' local neighborhood | |

| • Provision of a Community Resource Guide | |

| Sustaining behavior change is a difficult process | • Use of yoga to help manage stress |

| • Information on dealing with bullies | |

| • Discussion about emotions and eating | |

| • Between-session coaching calls | |

| • Use of raffles and small gifts as incentives | |

| • Managing “screen time” |

Discussion

Focus groups based on the Appreciative Inquiry process were found to be a useful approach to discover features that are important to low-income, urban-living parents to include in an adolescent weight management program. Consistent with the Appreciative Inquiry process, considerable energy was created in the focus groups by concentrating on family strengths and what currently was working well for them.

As families talked about their strengths and ideal views of healthy living and health-promoting communities, creative ideas of components to include in a family-based intervention program emerged. These included opportunities to cheer for their children, ways to participate in enhancing their community, and ways to actively engage with their children to sustain their children's interest in participating in a weight management program.

Several of their suggestions were incorporated into our intervention program. For example, monthly healthy living challenges were designed for families, such as “eat an apple every day for two weeks,” for which parents and children engaged in small, winnable competitions. Monthly “passports” were created that included a list of community activities in which the family could attend. This activity allowed families to try new activities in their community and cheer for each other as they completed their passports for a prize. We also used technology (iPads) on which the children competed in healthy living games and produced healthy living movies.

These ideas about how to promote healthy living may not have emerged if traditional focus group approaches had been employed that usually aim to elicit barriers and suggestions for solving problems associated with engaging in healthy living behaviors. Our findings of making health behavior change fun, shared, and part of a family lifestyle, community investment in family health, and improved accessibility to healthy foods and safe environments were consistent with themes found by others in the conduct of focus groups when enabling factors to health behavior change were sought.25,26

In contrast to focus group approaches using more traditional approaches that emphasize understanding the obstacles to making behavior change,3,4,6 strength-based approaches, such as Appreciative Inquiry, are designed to unleash creativity and garner positive energy and commitment to making change. We found that parents were able to describe idealized futures of healthy living, and generate specific strategies about their roles in realizing that future.

Similar to traditional focus group approaches, issues related to time, convenience, money, and availability of environmental and family resources related to healthy living and participating in a weight management program did arise in the Appreciative inquiry-based focus groups, but they were usually followed by ideas of how those situations could be different in the future and suggestions for improving them.

This qualitative study was the first to use a focus group methodology based on Appreciative Inquiry to elicit the positive experiences and strengths of predominately minority, low-income, urban-living families to codesign features of an adolescent weight management program. There are, however, some limitations of this study that should be considered. First, our sample consisted of parents whose children were participating in a school-based fitness program. Although the children were overweight or obese, it is possible that these families were more physically active and practiced healthier behaviors than families in which the children do not participate in a fitness-focused program, thus limiting the generalization of these findings.

An additional limitation of this study is that due to concerns about participant burden, the study team opted to use only the first two phases of the Appreciative Inquiry process, Discover and Dream. It is probable that if the last two phases of the process had been included, Design and Deliver, additional details in specific strategies for a weight management program may have emerged and greater commitment to making the changes required in moving toward a healthier future may have been garnered. This limitation is offset to some extent by the use of the phases of the Appreciative Inquiry process that focus on the promotion of high engagement, creativity, and positive energy in generating new ideas.

Despite these limitations, our findings indicate that focus groups using the Appreciative Inquiry process can be a useful method to engage families as codesigners of weight management programs. The Appreciative Inquiry approach creates considerable energy in the group which, in turn, promotes participant descriptions of positive futures and quick generation of numerous ideas about moving toward those positive images in the future.

Our team has recommendations for others who desire to use the Appreciative Inquiry process in the conduct of focus groups. A primary consideration is to be true to the Appreciative Inquiry process. The specific steps and exact questions used in the process are important.19 Leaders of focus groups using Appreciative Inquiry need to be trained in its use as this process can be particularly challenging to healthcare professionals who are trained to uncover and understand dysfunction in a system and predominately use problem-solving processes. It is a paradigm shift from the way we usually engage people to create change. It is recommended that to gain the maximum value of using this approach, it should not be combined in the same focus group sessions with questions designed to seek understanding of barriers or engage in problem-solving.

In conclusion, focus groups using Appreciative Inquiry can provide valuable information about features to include in a weight management program for adolescents and their families. We are currently testing our intervention designed with features learned in these focus groups in a 3-year randomized trial.27 As designers of weight management programs search for ways to include target populations as codesigners, Appreciative Inquiry offers a methodology that has the potential to create a horizon of new possibilities to promote positive action toward healthy lifestyles.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the planning and coordination of the focus groups by Jacqueline Charvat, PhD, and the assistance in recruitment provided by the We Run This City program staff at the YMCA of Greater Cleveland, including Ms. Tara Taylor and Barbara Clint, as well as the staff of the CWRU Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods for the collection of BMI and assisting with the recruitment efforts.

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, and the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (Grant Number U01 HL103622). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Institute of Child Health and Development.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Daniels SR, Jacobson MS, McCrindle BW, et al. . American Heart Association childhood obesity research summit executive summary. Circulation 2009;119:2114–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis AM, Daldalian MC, Mayfield CA, et al. . Outcomes from an urban pediatric obesity program targeting minority youth: The Healthy Hawks program. Child Obes 2013;9:492–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arai L, Panca M, Morris S, et al. . Time, monetary and other costs of participation in family-based child weight management interventions: Qualitative and systematic review evidence. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley GF, Goodred JK, Jago R, et al. . Parents' views on child physical activity and their implications for physical activity parenting interventions: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fulkerson JA, Kubik MY, Rydell S, et al. . Focus groups with working parents of school-aged children: What's needed to improve family meals? J Nutr Educ Behav 2011;43:189–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power TG, Bindler RC, Goetz S, Daratha KB. Obesity prevention in early adolescence: Student, parent, and teacher views. J Sch Health 2010;80:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Ventura AL, Pelaez-Ballestas I, Samano-Samano R, et al. . Barriers to lose weight from the perspective of children with overweight/obesity and their parents: A sociocultural approach. J Obes 2014;2014:575184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowgill BO, Chung PJ, Thompson LR, et al. . Parents' views on engaging families of middle school students in obesity prevention and control in a multiethnic population. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:E54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahlor L, Mackert M, Junker D, Tyler D. Ensuring children eat a healthy diet: A theory-driven focus group study to inform communication aimed at parents. J Pediatr Nurs 2011;26:13–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruhe MC, Bobiak SN, Litaker D, et al. . Appreciative inquiry for quality improvement in primary care practices. Qual Manag Health Care 2011;20:37–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredrickson BL, Branigan C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn Emot 2005;19:313–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotegard AK, Moore SM, Fagermoen MS, Ruland CM. Health assets: A concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:513–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushe GR. Advances in appreciative inquiry as an organization development intervention. Organ Dev J 1995;13:14–22 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bushe GR, Kassam AF. When is appreciative inquiry transformational? J Appl Behav Sci 2005;41:161–181 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooperrider DL, Whitney DK. Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change, First ed. Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore SM, Charvat J. Promoting health behavior change using appreciative inquiry: Moving from deficit models to affirmation models of care. Fam Community Health 2007;30(1 Suppl):S64–S74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludema JD, Cooperrider DL, Barrett FJ. Appreciative inquiry: The power of the unconditional positive question. In: Handbook of Action Research: The Concise Paperback Edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2006. pp. 155–165 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushe GR. Five theories of change embedded in appreciative inquiry. In: Cooperrider D, Sorenson P, Whitney D, Yeager T. (eds), Appreciative Inquiry: An Emerging Direction for Organization Development. Stipes: Champaign, IL, 2001, pp. 117–127 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooperrider DL, Whitney D, Stavros JM. Appreciative Inquiry Handbook. Crown Custom Publishing, Inc.: Brunswick, OH, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borowski E, Kofron R, Danosky L. “We Run This City” Youth Marathon Program: 2010 Evaluation Report. www.prchn.org/Downloads/2010%20WRTC%20Data%20Brief.pdf (Last accessed February7, 2017.)

- 21.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2003;15:85–109 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed. Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed. Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq 2010;16:837–851 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berge JM, Arikian A, Doherty WJ, Neumark-Sztainer D. Healthful eating and physical activity in the home environment: Results from multifamily focus groups. J Nutr Educ Behav 2012;44:123–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith KL, Straker LM, McManus A, Fenner AA. Barriers and enablers for participation in healthy lifestyle programs by adolescents who are overweight: A qualitative study of the opinions of adolescents, their parents and community stakeholders. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore SM, Borawski E, Cuttler L, et al. . IMPACT: A multi-level family and school intervention targeting obesity in urban youth. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;36:574–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]