Abstract

Rapid prototyping and fabrication of elastomeric molds for sterile culture of engineered tissues allow for the development of tissue geometries that can be tailored to different in vitro applications and customized as implantable scaffolds for regenerative medicine. Commercially available molds offer minimal capabilities for adaptation to unique conditions or applications versus those for which they are specifically designed. Here we describe a replica molding method for the design and fabrication of poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) molds from laser-etched acrylic negative masters with ∼0.2 mm resolution. Examples of the variety of mold shapes, sizes, and patterns obtained from laser-etched designs are provided. We use the patterned PDMS molds for producing and culturing engineered cardiac tissues with cardiomyocytes derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells. We demonstrate that tight control over tissue morphology and anisotropy results in modulation of cell alignment and tissue-level conduction properties, including the appearance and elimination of reentrant arrhythmias, or circular electrical activation patterns. Techniques for handling engineered cardiac tissues during implantation in vivo in a rat model of myocardial infarction have been developed and are presented herein to facilitate development and adoption of surgical techniques for use with hydrogel-based engineered tissues. In summary, the method presented herein for engineered tissue mold generation is straightforward and low cost, enabling rapid design iteration and adaptation to a variety of applications in tissue engineering. Furthermore, the burden of equipment and expertise is low, allowing the technique to be accessible to all.

Keywords: : cardiac regeneration, hydrogel polymers, PDMS molds, stem cells, tissue engineering

Introduction

In the last decade, there has been an increasing demand for the development of large organ-, patient-, or site-specific engineered tissues and scaffolds,1 with the goal of customized, and thus personalized, tissue engineering therapy. Natural and synthetic hydrogels have been explored as tissue scaffolds for decades due to their biocompatibility, high permeability to oxygen and nutrients, and ability to gel under mild chemical conditions for immobilizing living cells.2

Manipulating hydrogel morphology can be useful to design scaffolds with desirable mechanical or degradation properties, to create hydrogels that can accommodate various assays,3 and to study the effects of tissue structure on cell alignment and phenotype.4–6 For instance, specimens with well-defined and reproducible shapes are required for mechanical testing of hydrogels, and tight control over their geometries is fundamental for obtaining coherent and reproducible results.7 Regarding the in vivo implantation of engineered constructs, the possibility of mimicking the morphological and biophysical characteristics of healthy tissues or of reproducing the exact geometry of a tissue defect is of primary interest for personalized regenerative medicine.8–12

Among the techniques available for the fabrication of customized hydrogels is replica molding, which consists of creating the desired shape from an elastomeric negative mold by polymerizing the hydrogel in the mold. Poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) is commonly the material of choice for generating molds due to its flexibility, chemically inert composition, and low cost. PDMS molds have been widely used for the production of engineered tissues, microfluidics, and electronic devices. However, the generation of the masters used for casting PDMS generally requires time-consuming and expensive microfabrication techniques, such as photolithography. Recently, three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a more accessible and affordable technology to produce resin masters, but chemical interactions occur between PDMS and the resin surface, interfering with PDMS curing. Post-treatment of the 3D printed resin master is therefore a necessary step to allow homogeneous curing of PDMS. Novel approaches to replica molding are needed to simplify the production process and encourage customization of hydrogel-based engineered tissues.

In this work, we describe an alternative tissue molding method that allows the facile, rapid, and low-cost production of plastic masters for custom PDMS mold fabrication on the millimeter to centimeter scale. By using a laser cutter/etcher, we are able to etch master molds with specific shapes and patterns that are designed in vector graphic files. The use of laser-etching techniques is not novel in tissue engineering, as other groups have previously reported the use of laser etching/cutting of acrylic sheets to produce patterned masks for seeding cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells in microchannels.13 However, laser etching has not yet been adopted for the formation of large engineered tissues for in vitro and in vivo applications. In our laboratory, we produce hydrogel-based engineered cardiac tissues using laser-etched mold designs with geometries tailored for drug delivery, electrical activation, mechanical testing, and in vivo assessment. In this study, we demonstrate versatility and reproducibility of the engineered tissues that can be obtained using PDMS molds cast in laser-etched masters, and we provide examples of molds specifically tailored to excitation, with the creation of physiological and disease models, and for ease of implantation, with sequential modifications of the design and of the biomaterials used for rat cardiac surgery. Finally, we show the design and production of a customized implantable engineered tissue made from human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes for cardiac regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Creating vector format master mold designs

(a) The cutting patterns of most commercial laser cutters are directed by vector graphic files produced by vector graphic editors such as Adobe Illustrator (Adobe System, Inc., San Jose, CA) and the open source program Inkscape (Inkscape Project, www.inkscape.org). Colors selected in the graphic files will be used to dictate power, speed, and dots per inch (DPI) (or frequency) settings for the laser cutter, corresponding to the depth of cutting or etching and the rate of energy transfer (Fig. 1A).

(b) Molds are designed with at least one color assigned to etching, via the laser cutter's raster mode. For the experiments reported herein, a ULS 6.75 model laser cutter equipped with a 75 W laser was used. Etched features in the master mold will translate to positive features in the final PDMS molds with feature height corresponding to etching depth. Additional etching colors can be used to create PDMS molds with varying feature heights.

(c) At least one color is generally assigned to cutting, via the laser cutter's vector mode, to cut the master mold from the sheet of stock material. Rounded corners facilitate using tape to form a seal around the edge of the master mold, to prevent PDMS from leaking during the casting process.

(d) Colors should be chosen in the design process such that they can correspond to settings in the laser cutter's software in RGB, CMYK, or hexadecimal format. Assignable colors and color format will depend on the laser cutter software.

(e) Mold designs were fabricated with dimensions as small as 10 × 3 mm to as large as 2 × 1.5 cm, with a minimum 6 mm border between the edge of the mold geometry and the edge of the master mold. The wide border will facilitate trimming of the PDMS meniscus that forms along the edge of the master mold during casting. Mold dimensions can be chosen to accommodate tissue culture plates of various sizes (e.g., 10 cm, 6-well plates, 24-well plates), as well as for compatibility with preconditioning regimens such as electric stimulation that requires submersion of electrodes in the culture medium adjacent to tissue molds. The upper limits for mold dimensions are prescribed by the laser-etching machine and its material bed (80 × 45 cm for the Universal Laser Systems (ULS) 6.75 model laser cutter used in this study), which is much larger than what is required for culture of engineered tissues.

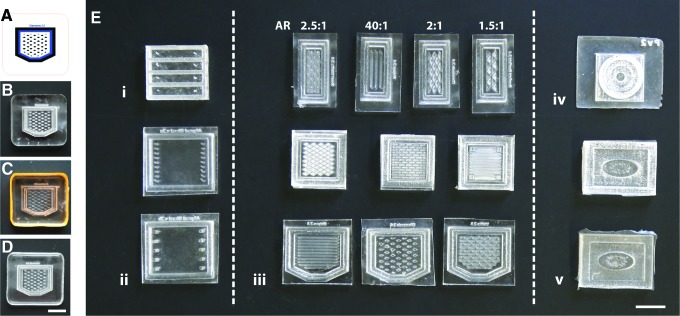

FIG. 1.

Fabrication of PDMS molds with varying geometries and internal features for the production of engineered cardiac tissues. (A) Master molds are designed as vector graphic files compatible with the laser cutting software. (B) Quarter inch thick acrylic stock material is etched and cut with the laser cutter. (C) The laser-etched acrylic master mold is surrounded by tape and PDMS (4 mL) is cast into the master mold, degassed under vacuum, and cured overnight at 60°C. (D) The final PDMS mold is then removed from the master and ready for sterilization. (E) Many geometries of PDMS molds have been customized for specific applications in cardiac regeneration. (i) Rectangular molds with elongated posts at their extremities (aspect ratio: 5.7:1) and (ii) sheets (aspect ratio: 1.2:1) were evaluated for mechanical testing. (iii) Molds with varying dimensions and patterns were designed for modulating cell alignment and scaled up for in vivo implantation. (iv) Concentric layered and (v) confined geometries were developed for spatiotemporal drug delivery. Scale bars = 1 cm. PDMS, poly(dimethylsiloxane). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Laser cutting master molds

(a) A hard plastic that responds well to laser cutting and the temperatures necessary for fast PDMS curing (∼60°C) is most desirable as the master mold material. Plastic thickness can be dictated by the requirements of the PDMS molds and the limits of laser cutter's maximum cutting and etching depths. For our applications, ¼" thick acrylic has been suitable and is more economical than Delrin (Fig. 1B).

(b) Stock material should be positioned on the bed of the laser cutter and the distance from the laser to the material should be adjusted according the manufacturer's specifications.

(c) If speed, power, and DPI/frequency settings specific to the master mold material and the laser cutter are not available, calibration runs may be necessary to identify settings that yield the desired specifications. For the ULS 6.75 model laser cutter with a 75 W laser, Power = 32, Speed = 3, DPI = 500 produced an etch depth of ∼3.3 mm in acrylic, and Power = 100, Speed = 1, DPI = 1000 cut ¼″ thick acrylic cleanly. Calipers can be used to evaluate etch depth.

(d) Once master molds have been fabricated, they should be cleaned to remove as much debris as possible. Fine brushes and compressed air can be used to clean cut troughs of waste material.

Preparing PDMS molds for cell or tissue culture

(a) Before casting PDMS (Sylgard 184®; Dow Corning Corporation, Auburn, MI), apply strips of tape suitable for temperatures of 60°C (Fisherbrand™ colored label tape works well) around the edges of the master mold and press firmly to keep PDMS in place during the casting process (Fig. 1C).

(b) Prepare PDMS according to the manufacturer's specifications and degas the liquid PDMS to remove all air bubbles in a vacuum chamber. It should be noted that the hydrophobic properties of PDMS can cause it to adsorb hydrophobic small molecules. If this will be problematic for a desired application, the PDMS molds could be treated with an antifouling agent such as polyhydrophilic or polyzwitterionic materials.14 Alternatively, a PDMS mold could be used as a master for fabricating molds of another material, such as agarose.

(c) Place the master mold in a transport dish (e.g., 10-cm culture plate) and pour the degassed PDMS over the taped plastic master mold until the desired base thickness is achieved. In determining base thickness, the focal range of any inverted microscopes that might be used for imaging during tissue formation in the PDMS mold should be taken into consideration. A 1–2 mm base thickness is common. Then, degas the PDMS-coated molds under vacuum until all bubbles are removed.

(d) Place the degassed, coated molds into an oven set to 60°C overnight to allow the PDMS to cure. Alternatively, the molds can be left at ambient temperature for ∼72 h to cure. In either case, molds must be left on a level surface to ensure an even thickness.

(e) After curing, the PDMS molds can be gently removed from the plastic master molds (Fig. 1D) by peeling the cured PDMS out of the negative master by hand or with forceps. If multiple PDMS molds are generated adjacent to one another using one plastic mold, cutting the PDMS molds apart with a razor blade first will facilitate removal. Trim away excess PDMS.

(f) For sterilization, PDMS molds can be placed in autoclave pouches, sealed with autoclave indicator tape, and autoclaved under a standard gravity cycle. Cured Sylgard 184(R) will remain stable up to 200°C. Alternatively, soaking in 70% ethanol for 15 min and allowing to thoroughly air dry in a sterile biosafety cabinet provides adequate sterility for most applications.

Casting collagen and fibrin hydrogel tissues

(a) Depending on the application, it may be necessary to adhere the PDMS molds to the bottom of a cell culture dish. The hydrophobic surface of PDMS makes it well suited for adhering to the bottom of untreated polycarbonate dishes with the application of firm pressure. However, after repeated use, the strength of this bond tends to deteriorate, likely due to the adsorption of molecules on the PDMS. If repeated mold use is desired, a natural or synthetic adhesive, such as fibrin or silicone sealant cured overnight, can be used to ensure attachment.

(b) Neutralized collagen, fibrinogen, and thrombin solutions should be prepared at concentrations necessary to achieve the desired final concentration in the construct formulation. Collagen should be kept on ice until casting, and fibrinogen should not be mixed with thrombin until immediately before casting. Cells should be harvested and resuspended at a concentration necessary to achieve the desired cell density in the construct formulation. Account for cell volume when calculating final volume of hydrogel and cells together.

(c) Before casting tissues, the top surface of the mold should be treated with oxygen plasma to create a hydrophilic surface necessary for cell attachment and desirable for ease of pipetting into the mold for uniform, cohesive gelation. This can easily be performed with a handheld plasma device such as the BD-20A high-frequency generator (Litton Engineering, Grass Valley, CA). Alternatively, molds can be treated with pluronic F-127 to reduce protein adsorption. Surface treatment should be performed immediately before seeding or casting, as the polarity change will deteriorate over time.

(d) During tissue casting, care should be taken to ensure that the construct solution makes contact with all edges of the mold cavity and is evenly distributed. Pipette ejection beyond the first stop should not be used to avoid creating bubbles in the tissue constructs. Collagen-based tissues should be incubated for 45 min to 1 h to allow the hydrogel to polymerize before media are added to cover the tissues. If constructs are incubated and kept in culture, change culture media carefully so as not to disturb constructs every 48–72 h for cardiomyocytes and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). If other cell types are immobilized in the constructs, medium change should be planned according to the recommended instructions provided by the suppliers to ensure maximum cell health.

(e) After use, molds can be cleaned with bleach, ethanol, and distilled water, dried, and autoclaved again up to 10 times for future use.

Tissue implantation in vivo

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the U.S. NIH Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol No. 1310000025).

(a) Myocardial infarcts are induced in 8-week-old (250 g) male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratory) by ischemia/reperfusion as previously described.15 Rats are anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 90 mg/kg ketamine and 8 mg/kg xylazine. They are intubated, mechanically ventilated, and kept on a warming pad for the duration of the surgical procedure. After exposing the heart by thoracotomy, the left anterior descending coronary artery is occluded for 60 min, then reperfusion is performed, and the chest cavity is closed. Animals receive analgesic according to best practices.

(b) Four days after ischemia/reperfusion injury, engineered tissues are implanted over the myocardial infarct. Rats are anesthetized with 3–5% isoflurane supplemented with oxygen, intubated, and mechanically ventilated. The chest cavity is opened by thoracotomy through the same incision. The implant is washed in sterile PBS, lifted from the culture dish on forceps, placed over the heart, and sutured on the epicardial surface of the left ventricle with three 7–0 sutures (VP702X, Surgipro II, Covidien). The chest is closed aseptically and animals recover under monitoring and with analgesic.

(c) To improve handling of the large engineered tissues and to maintain their integrity during implantation, the mechanical strength of the constructs is increased by preparing collagen–fibrin interpenetrated polymer networks (by mixing 8 mg/mL fibrinogen, 20 U aprotinin, and 5 μL of 200 U/mL thrombin with 720 μL collagen for each construct) or by casting a fibrin sheet (250 μL of 33 mg/mL fibrinogen mixed with 3 μL of 200 U/mL thrombin) on top of the collagen constructs 10 min before implantation. In vitro culture duration of engineered tissue impacts stiffness and handling properties.

(d) Rats are examined daily and receive analgesic (buprenorphine 0.01–0.05 mg/kg) as needed, up to two doses per day for 2 days postsurgery. Seven days after the implant surgery, animals are sacrificed by pentobarbital overdose (180 mg/kg) and hearts are harvested for histological evaluation.

Cardiac differentiation, neonatal rat cardiomyocyte harvest, isolation of MEFs, and optical mapping of action potential in vitro

A detailed description of the methods adopted to derive cardiomyocytes from hiPSCs and to harvest neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and MEFs is reported in the Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec). The optical mapping protocol, based on the use of the voltage-sensitive dye di-4 ANEPP to measure action potentials of cardiomyocytes in the engineered constructs, is also described in the Supplementary Data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used. Samples were considered statistically different for p-values <0.05.

Results

The fabrication method described herein enables the rapid production of PDMS molds from laser-etched acrylic masters (Fig. 1A–D) and it has been adopted in our laboratory for the production of engineered cardiac tissue. PDMS molds with varying size, shape, and geometrical features (Fig. 1E) were produced to study specific in vitro processes or to tailor the anatomical characteristics of the tissue for intended use in vitro or in vivo. For instance, rectangular molds with posts at the extremities were designed for in vitro mechanical testing of tissues to anchor the tissue during compaction and enable cellular tension to facilitate cardiomyocyte alignment along the major axis of the construct (Fig. 1Ei). The design consists of a single 1.7 × 1.5 cm mold containing four individual 1.7 × 0.3 cm chambers to produce n = 4 identical tissue replicates that can be cultured in the same conditions and that fit in one well of a six-well plate culture dish.

For biaxial mechanical testing of larger tissue sheets, 1.8 × 1.5 cm PDMS molds with multiple posts on their lateral sides were fabricated (Fig. 1Eii) and could be redesigned with posts along the top and bottom edges for increased tissue uniformity. Addition of rectangle-, triangle-, diamond-, and striped-shaped features with different aspect ratios (Fig. 1Eiii), similar to a previously described design of rectangular posts with more labor-intensive micromolding techniques,16 was used to modulate cellular alignment within thick tissue sheets. Several PDMS molds were produced with various internal features, their size was scaled up, and their shape was optimized in vitro before use in vivo as cardiac implants (Fig. 1Eiv). Figure 1Eiii shows molds with rectangle, striped, diamond, and triangle features (top row, left to right), large molds with diamond, rectangle, and striped features (middle row, left to right), and in vivo-optimized molds with striped, diamond, and rectangle features (bottom row, left to right). An important optimization of the mold design for in vivo implantation of patterned constructs was utilizing cut corners for easy surgical alignment with the adult rat heart's apex (Fig. 1Eiii, bottom row).

Concentric circle and confined elliptical geometries with varying post spacing (Fig. 1Eiv, v) were adopted to test the spatiotemporal release of drugs and growth factors in 3D constructs. More specifically, the concentric circle geometry, composed of three stacked, vertical layers with increasing diameter (Fig. 1Eiv), is designed for the production of hybrid scaffolds cast in separate, contacting layers to allow the combination of up to three spatially distinct biomaterial conditions providing different drug/molecule release. The use of such scaffolds for drug delivery applications enables the use of spatiotemporal cues in the z-direction. The confined elliptical geometries (Fig. 1Ev) instead incorporate different drug release conditions in distinct x–y regions of the same scaffold. In this case, two hydrogels, either made of the same or different biomaterials, are formed in the same plane and are separated with posts at different spacing, which allows for varied contact area between gels. We provide here three representative examples on the use of this method for the fabrication of engineered tissues, focusing in particular on cardiac regeneration.

Tissue compaction in patterned engineered tissues

Rectangular molds (Fig. 1Eiii, top row) incorporating posts with unique shapes were produced to assess the influence of tissue-level geometric cues on tissue compaction (Fig. 2A). PDMS molds with diamond-, triangle-, and rectangle-shaped or striped posts were cast from acrylic masters and used to fabricate engineered tissues by immobilizing MEFs (Fig. 2) or primary rat cardiac cells (Fig. 3).

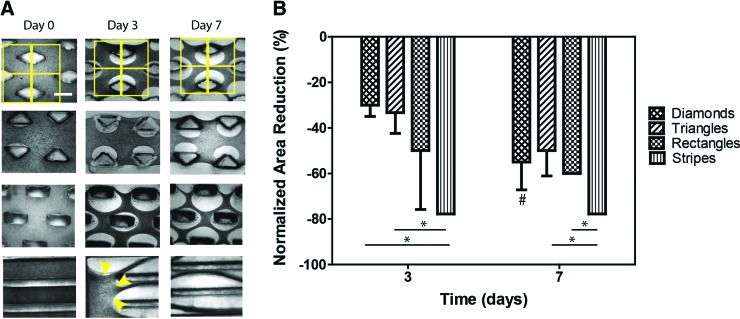

FIG. 2.

Tissue compaction assay of patterned collagen scaffolds. (A) Brightfield images of engineered tissues produced in the patterned PDMS molds (diamonds, triangles, rectangles and stripes; top to bottom). Constructs were fabricated by immobilizing MEFs (2 × 106 cells per construct) in 1.25 mg/mL collagen hydrogel. Scale bar = 1 mm. Matrix remodeling is visible from 1 day of culture onward. Compaction is quantified by dividing the brightfield images in multiple nonoverlapping 1.5 × 1.5 mm squares centered on post midlines to measure the area occupied by the tissue between posts (first row, yellow squares) and normalizing the value by the area measured at day 0. The edges of the constructs (e.g., yellow arrows) were not included in the analysis. (B) Quantification of tissue compaction by measurement of the tissue area normalized to day 0. ANOVA was used to test differences among groups (*p < 0.05), and paired t-test analysis was performed to compare the means of constructs at day 3 versus day 7 (#p < 0.05). ANOVA, analysis of variance; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

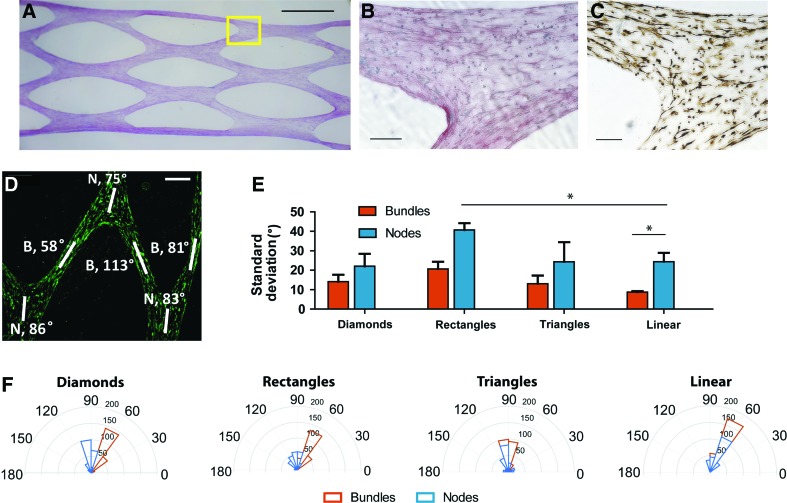

FIG. 3.

Evaluation of cardiomyocyte alignment in patterned constructs. (A) Picrosirius red staining of the whole diamond-featured construct, scale = 1 mm. The yellow box shows the area visualized at higher magnification in (B, C). Tissue region showing three bundles of tissue meeting at a node and stained with picrosirius red for collagen (B) and with cardiac troponin T for cardiomyocytes (C), scale bars = 200 μm. (D) α-Actinin immunohistochemistry staining (green) in the diamond-shaped construct reveal cardiomyocyte alignment in tissue bundles and nodes (indicated with the letters B and N, respectively). (E) Comparison of the standard deviations of mean cell alignment in the different patterned tissues. (F) The orientation of cardiomyocytes in single bundles and nodes is represented with rose plots showing a radial histogram of alignment degree (0–180) and cell count (0–200). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Remodeling of the collagen matrix by MEFs, assessed by extent of tissue compaction, was visible after 1 day of culture. This manifested as increased pore dimensions and reduced tissue bundle diameters between the geometric features, and continued up to 7 days (end of the experiment). Within this time frame, the kinetics of compaction appeared to be altered by macroscopic geometry, with the striped geometry (aspect ratio of the stripes = 40:1) yielding the fastest compaction into long tissue bundles (78% area reduction after 7 days). The shape and aspect ratio of the internal features of the striped geometry were designed to be significantly different in comparison to the diamond, rectangle, and triangle geometries, to provide an anisotropic reference for the evaluation of compaction of single tissue bundles along the long axis of the features. MEFs immobilized in constructs with diamond-, rectangle- and triangle-shaped posts, designed with similar aspect ratio of the posts (2.0:1, 2.5:1, and 2.0:1, respectively) and number of posts per area, showed comparable remodeling of collagen (55% ± 5% area reduction at day 7).

Effects of geometry on cardiomyocyte alignment and action potential propagation

Several studies have reported that the morphology of 3D constructs has a considerable effect on cell behavior,17,18 impacting cell phenotype, alignment, and function. Tissue anisotropy, that is, the directionally dependent organization of cells and matrix in 3D space, is of particular interest for cardiac regeneration, because cardiomyocyte alignment follows the fiber angle of the muscular wall to maximize ejection fraction with each contraction.19 Anisotropic cardiac constructs were created in PDMS molds containing internal geometrical features (Fig. 3) by combining collagen (1.25 mg/mL) with neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (1 × 106 cells/construct). As with MEF-engineered constructs, homogeneous cell dispersion and progressive tissue compaction were observed (Fig. 3A, B). Alignment of the immobilized cardiomyocytes was superior within tissue bundles, while tissue nodes (where bundles intersect) resulted in greater variation in cellular orientation (Fig. 3C–F). The spatial orientation of the cells was determined by processing the α-actinin signal in MATLAB, and representative rose plots of cell alignment in one bundle and one node of each patterned tissue are shown in Figure 3D. Comparing the rose plots and the standard deviations in the tissue nodes and bundles, we determined that diamonds, triangles, and stripes provide enhanced cardiomyocyte alignment. However, due to difficult handling and breakage of the striped constructs and difficulty in loading triangular molds without introducing bubbles, we utilized diamond features for the design of engineered tissues for cardiac regeneration in vivo.

The design of the cardiac constructs was further optimized to provide uniform action potential propagation in the engineered tissues. Optical mapping was performed on cardiac tissue constructs produced in the PDMS molds with varying geometries defined by post shape, size, and aspect ratio, and with different cell types, such as neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, cocultures of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts, or hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Constructs were stained with voltage-sensitive dye di-4 ANEPPS, and action potential propagations were recorded at 1000 f/s as described in the Supplementary Data. Representative action potential propagation maps of cardiac constructs show nonuniform activation that led to reentrant electrical patterns in an initial design (Fig. 4A) and a redesigned tissue mold geometry that has uniform conduction (Fig. 4B).

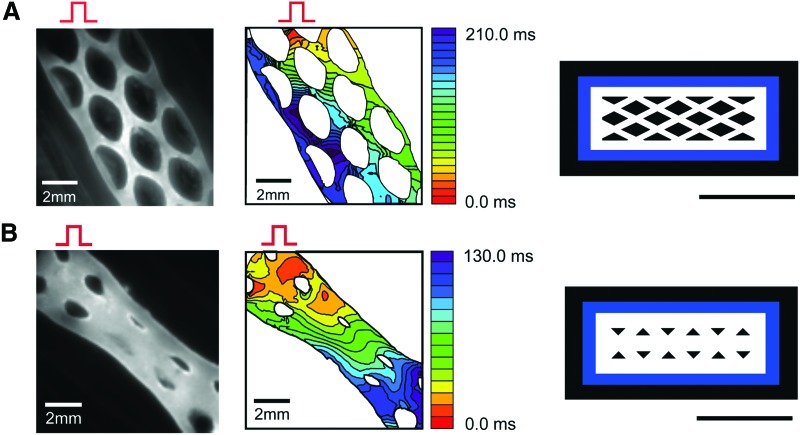

FIG. 4.

Conduction velocity and action potential propagation in different mold designs. Left panels: di-4 ANEPPS fluorescence images from the engineered tissues. The bipolar stimulation electrode was located on the upper region of field of view (red pulse), which initiates actin potential propagation. Middle panels: action potential propagation maps. The isochronal lines are drawn every 10 ms interval. Right panels: mold designs, Adobe Illustrator vector graphic files, scale bars = 1 cm. (A) Diamond-shaped design with thick borders compared to the thickness of the internal tissue bundles caused re-entry in the cardiac tissue. Construct was prepared with 1.25 mg/mL collagen and cocultures of P1 2 × 106 neonatal Sprague-Dawley rat cardiomyocytes and P1 2 × 106 cardiac fibroblasts, and paced at 10 V, 4 ms, 1 Hz for 3 days before optical mapping. (B) Example of uniform action potential propagation obtained with a triangle-shaped design with increased bundle size. 1.25 mg/mL collagen and 10 × 106 hiPSC-cardiomyocytes were used to produce the construct, which was stimulated at 10 V, 4 ms, 1 Hz for 5 days. hiPSC, human-induced pluripotent stem cell. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

In the example of Figure 4A, the action potentials propagated faster along the long axis edges of the tissue versus in the transverse direction, where conduction velocity was 0.11 mm/ms along the borders of the construct and 0.04 mm/ms in the transverse direction. As a result, delivering a premature stimulation caused a conduction block in the transverse direction and initiated a reentrant arrhythmia that lasted 20 s (Supplementary Movie SM1). This result was eye opening, suggesting that the thickness of the tissue border relative to the internal bundles could impact the conduction velocity and path, and in doing so increase the risk for reentrant arrhythmia formation in the engineered cardiac tissue. This tissue geometry could be utilized as a disease-in-a-dish model of reentrant arrhythmia, as previously shown in two-dimensional (2D) culture.20 However, we wanted to improve the uniformity of the action potential propagation in the engineered tissues, and so we redesigned the tissue molds to increase the thickness of the tissue bundles in the interior of the construct while slightly reducing the thickness of the borders to avoid reentry (Fig. 4B). An equal 1:1 ratio of tissue bundle thickness in the geometrical pattern versus borders led to uniform signal propagation along the cardiac tissue with improved overall conduction velocity (0.17 mm/ms) and had a human-like action potential duration (APD) of 290 ms (Supplementary Movie SM2).

In vivo implantation of anisotropically aligned engineered cardiac tissue

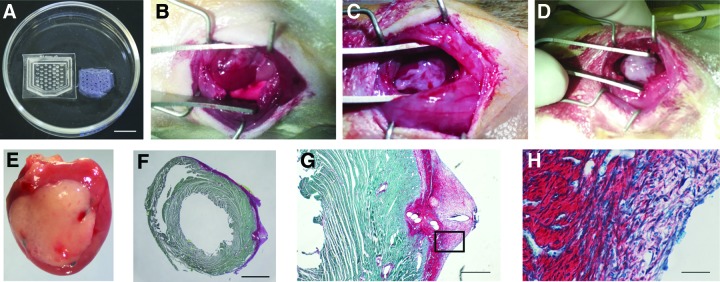

For in vivo implants, cardiac-engineered tissues were produced in larger molds (Fig. 5A) to span the scar and contact border zone and surrounding healthy tissues of infarcted rat hearts. Full coverage of the infarct area to contact the border zone and surrounding healthy tissue was achieved by designing 2 × 1.5 cm cardiac constructs with cut corners at the apex. The main axis of the tissue and internal diamond-shaped anisotropic posts were horizontal to match the circumferentially oriented epicardial fibers of the left ventricular free wall (Fig. 5A). Large cardiac tissues were sutured on the infarcted left ventricle (Fig. 5B) and were retained on the heart until explant (at 7 days), showing uniform adhesion with no visible separation of graft and myocardial tissue and robust cellular engraftment as detected by the persistence of the implanted tissue (Fig. 5E).

FIG. 5.

Cardiac constructs implanted on the epicardial surface of the left ventricle 4 days after infarct. (A) PDMS-patterned mold designed for implant on rat hearts (left) and resulting cardiac construct (right). Scale bar = 1 cm. (B–D) Optimization of the handling and implantation of collagen scaffolds: 1.25 mg/mL collagen-based cardiac tissues cultured for 4 days are soft and difficult to suture (B), while fibrin sheet casting (C) and interpenetrated network constructs made of 1.25 mg/mL collagen and with 8 mg/mL fibrin (D) maintained tissue integrity and improved handling and engraftment over the implant site. (E) An explanted heart 7 days after receiving an engineered tissue shows the epicardial cardiac graft and the location of three blue polypropylene sutures. (F–H) Histology of collagen constructs containing 6.8 × 106 hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes implanted on the healthy heart of male nude Sprague-Dawley rats 9 days after implant. (F) Cross-section of a whole apical section of the heart stained with picrosirius red and fast green (scale bar = 2 mm) shows the complete coverage of the left ventricle with the collagen scaffold (collagen stained in red). Images of the construct taken at higher magnification (G, scale bar = 500 μm and H, scale bar = 50 μm) show the presence of cells in the implant. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

When implanting large collagen-based engineered tissues on a beating heart, one of the major challenges is poor construct mechanical strength, which is further compromised by the diamond-shaped pores of our designs. Diamond-patterned collagen-based cardiac tissues were difficult to suture on the epicardial surface of the left ventricle because they lacked rigidity, collapsed upon themselves, and moved easily on the heart with cardiac contractions and ventilation, often breaking into pieces and losing orientation relative to the whole heart when positioned in the surgical site with forceps (Fig. 5B). Adding a fibrin sheet over the scaffold 5–10 min before implantation and allowing gelation noticeably improved the ease of handling and suturing of the construct, with scaffolds retaining their integrity once positioned on the heart (Fig. 5C). However, we observed an increased frequency of chest adhesions during explant when using the fibrin sheet approach (qualitative observation, data not shown). Another strategy that we have adopted to increase the stiffness of the engineered tissues is the production of collagen–fibrin copolymer constructs, obtained by mixing fibrinogen, thrombin, and aprotinin with collagen during construct preparation (Fig. 5D). Durable collagen–fibrin constructs can be produced with this approach and are preferably implanted within 24 h, due to the fast fibrin degradation observed for longer in vitro culture of the constructs.

Discussion

PDMS mold fabrication from laser-cut polyacrylic masters is a reliable, easy, and low-cost method for the production of scaffolds and engineered tissues in the centimeter length scale with highly reproducible features with ∼200 μm resolution (Fig. 1). The rapid design and production afforded by this method enable customization for many applications and a suitable and affordable alternative to commercially available tissue engineering molds or microfabricated templates. The cultivation of engineered tissues in PDMS molds designed to fit 6- or 24-well plates offers several advantages, such as minimal handling of the constructs during culture and imaging, as well as the ability to customize culturing conditions, such as maintaining our cardiac constructs aligned with the direction of the electric field when electrically paced in culture.

The simplicity of this method for modulating mold geometry enables us to better understand how cells interact with the hydrogel to form a tissue and develop a collective behavior. In agreement with previous studies showing the cell-mediated remodeling of collagen gels by fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, and other cell types,21–23 MEFs induced gel compaction rapidly in the 3D tissue microenvironment and compaction continued for at least 7 days (Fig. 2). Acellular collagen constructs cultured for 72 h did not show degradation of the material (data not shown). We found that changing the shape of the posts when utilizing an array of posts influenced the local orientation of cells within the tissues and thereby affected global anisotropy. While maintaining an aspect ratio of the posts in the range of 2.0:1–2.5:1, we compared triangular-, rectangular-, and diamond-shaped posts, resulting in varied local alignment of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with Bian et al.24,25 who have previously shown fabrication of cardiac patches with neonatal rat cardiomyocytes aligned along the long axis of microfabricated rectangular posts. In our study, angle dispersion was greatest in tissue nodes (versus bundles), and nodal dispersion was minimized with anisotropic diamond-shaped posts.

Our studies demonstrate that manipulating the macroscopic geometry of engineered tissues modulates tissue anisotropy, cellular orientation, and cellular phenotype. These macroscopic cues to direct tissue form and function are critical for many tissue types, including the well-established anisotropy of cardiac muscle.19 The fiber orientation of myocardium is an essential feature for efficient mechanical function to maximize ejection of blood.26 Fiber orientation is also important for cell–cell coupling and cardiac conduction, and disruption of fiber architecture such as with an infarct can be associated with high risk for conduction blocks and re-entry formation, resulting in ventricular fibrillation.27–29 It has been shown that anisotropic orientation of cardiomyocytes increased anisotropy of action potential propagation and longitudinal conduction velocity.24,25 Our data confirm that anisotropic constructs have anisotropic conduction directed by tissue morphology (Fig. 4). Furthermore, our results extend this concept into the realm of tissue malfunction or disease-like states and demonstrate the role of tissue geometry in eliciting action potential reentrant arrhythmias (Fig. 4A). When the diameter of internal tissue bundles was small and the conduction velocity was slow in these bundles, the risk for conduction block increased and action potential propagation could be elicited in circular patterns, which underlies ventricular tachycardia.30,31 Both electrophysiological and anatomical characteristics such as slow conduction, unstable APD, fibrosis, and compact scar are known to facilitate reentry.32–37 Risks for reentry become higher when any nonspecific action of pharmacological intervention alters these parameters. Therefore, these engineered cardiac tissues showing reentry (Fig. 4A) could be used as arrhythmia models and utilized for in vitro drug screening. However, our goal was to create uniform tissues for implantation to ameliorate conduction blocks present in injured hearts, necessitating the redesign of the engineered tissue geometry. An increase in internal bundle diameter increased conduction velocity across the engineered tissue, which improved the safety factor for action potential propagation thereby eliminating the ability to initiate reentry (Fig. 4B). This example highlights the power of our customized molding process and the impact that tissue macroscopic shape has on functional properties of the tissue.

Utilizing our laser-etched diamond-post design for molding engineered tissue, we produced a customized hiPSC-derived cardiac tissue and developed surgical implantation strategies in a rat model of myocardial infarction. While numerous groups have implanted engineered tissues on the heart,38–40 development of the tissues specifically for improving the implantation process is an important goal in furthering the translation of engineered tissues into preclinical models. The size and shape of the implants were optimized with iterative design and testing according to the size and anatomical characteristics of 8-week-old rat hearts. The dimensions of the engineered tissues were scaled up to 2 cm wide × 1.5 cm long and the bottom corners were cut so that scaffold orientation relative to the heart's apex would be easily recognized on removal from the molds for implantation. Increasing the mechanical properties of our collagen-based constructs before implantation was a critical step for handling the constructs during surgery. Stiffer hydrogels were produced by mixing fibrin with collagen during construct preparation, so that the implants could be easily positioned and sutured on the surface of the beating heart (Fig. 5). This strategy can be adopted only when the constructs are implanted immediately after preparation or when an inhibitor of fibrinolysis (such as aprotinin) is used because fibrin has fast in vitro and in vivo degradation kinetics. When construct maturation in vitro before implantation is desired and engineered tissues are cultured for several days before being implanted, the formation of a fibrin sheet on top of the construct just before implantation provided similar durability for handling during implantation.

We have reported here the use of laser-etched designs for the production of engineered tissues with size, shape, alignment, conduction properties, and durability tailored for cardiac regeneration in a rat infarct model; however this method can be used to customize constructs for many hydrogel/cell combinations for a variety of biomaterials (Supplementary Fig. S1) and tissue types, including skin, cartilage, bone, liver, brain, and others. Although molds can be decontaminated and sterilized in an autoclave after each use, recent studies showed that PDMS can absorb small hydrophobic molecules and proteins during culture, thus potentially altering the outcome of drug testing experiments or subsequent experiments if molds are reused.41 This poses a major limitation for studies evaluating drug and protein release, dose dependence, and cell signaling. A recent article by Su et al.42 compared PDMS to polystyrene (PS) and cyclo-olefin polymer (COP) microfluidic channels for drug screening applications, and demonstrated that both PS and COP were more suitable than PDMS when evaluating cardiotoxicity on human embryonic kidney cells by monitoring hERG (human ether-a-go-go related gene) potassium ion channel activity in response to five different drugs. We cast new PDMS molds for each experiment to minimize molecule carry over between experiments, but a double-molding approach could be used to cast other materials (such as agarose) in a PDMS-negative template produced either from a laser-etched positive mold or from a positive PDMS mold.

Conclusions and Future Directions

We have demonstrated a simple, cost-effective, rapid prototyping approach to generate customized geometries using PDMS molds cast from laser-etched acrylic templates for tissue engineering. Working in the millimeter to centimeter length scale enables development of large tissues for translational studies and personalized medicine. Future directions may utilize this workflow to develop increasingly complex 3D features, by fabricating constructs with specific shapes, features, biomaterials, or cell types. The molding process can be further optimized to incorporate a perfused microvasculature in the cardiac implant, by coculturing cardiomyocytes and stromal cells in the engineered tissue, as suggested by Roberts et al.,43 or by integrating microchannels in the design of the PDMS molds. Engineered tissues formed in these molds may be used as tissue units for a self-assembled building block approach, as proposed by Gwyther et al.44 Alternatively, the engineered tissue building blocks may be assembled into larger structures with controlled orientation by use of innovative technologies, such as the Bio-Pick, Place, and Perfuse (Bio-P3) instrument.45 Finally, the laser-etched molds may be designed with 3D features able to integrate and confine polymeric fibers, meshes, or sponges to reinforce the constructs and further modulate their internal structure and porosity.46–48

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from NIH R00 HL115123 (to K.L.K.C.), Brown University School of Engineering (to K.L.K.C.), and Brown University Dean's Emerging Areas of New Science Award (to K.L.K.C., B.-R.C., and Ulrike Mende, MD). They are grateful to Chris Bull and the Brown Design Workshop for training and support on the laser cutter/etcher, and to Ulrike Mende and Michelle King (RI Hospital and Brown University Alpert School of Medicine) for providing primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Neves L.S., Rodrigues M.T., Reis R.L., and Gomes M.E. Current approaches and future perspectives on strategies for the development of personalized tissue engineering therapies. Expert Rev Precis Med Drug Dev 1, 93, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman A.S. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54, 3, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCain M.L., Agarwal A., Nesmith H.W., Nesmith A.P., and Parker K.K. Micromolded gelatin hydrogels for extended culture of engineered cardiac tissues. Biomaterials 35, 5462, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee K.Y., and Mooney D.J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering. Chem Rev 101, 1869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kloxin A.M., Kloxin C.J., Bowman C.N., and Anseth K.S. Mechanical properties of cellularly responsive hydrogels and their experimental determination. Adv Mater 22, 3484, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aubin H., Nichol J.W., Hutson C.B., Bae H., Sieminski A.L., Cropek D.M., Akhyari P., and Khademhosseini A. Directed 3D cell alignment and elongation in microengineered hydrogels. Biomaterials 31, 6941, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu J.J., Chen G.W., Liu Y.C., and Hsu S.S. Influence of specimen geometry on the estimation of the planar biaxial mechanical properties of cruciform specimens. Exp Mech 54, 615, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayson W.L., Fröhlich M., Yeager K., Bhumiratana S., Chan M.E., Cannizzaro C., Wan L.Q., Liu X.S., Guo X.E., and Vunjak-Novakovic G. Engineering anatomically shaped human bone grafts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 3299, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moroni L., Curti M., Welti M., Korom S., Weder W., de Wijn J.R., and van Blitterswijk C.A. Anatomical 3D fiber-deposited scaffolds for tissue engineering: designing a neotrachea. Tissue Eng 13, 2483, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson B.N., Lancaster K.Z., Zhen G., He J., Gupta M.K., Kong Y.L., Engel E.A., Krick K.D., Ju A., Meng F., Enquist L.W., Jia X., and McAlpine M.C. 3D printed anatomical nerve regeneration pathways. Adv Funct Mater 25, 6205, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertassoni L.E., Cecconi M., Manoharan V., Nikkhah M., Hjortnaes J., Cristino A.L., Barabaschi G., Demarchi D., Dokmeci M.R., Yang Y., and Khademhosseini A. Hydrogel bioprinted microchannel networks for vascularization of tissue engineering constructs. Lab Chip 14, 2202, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhumiratana S., Bernhard J.C., Alfi D.M., Yeager K., Eton R.E., Bova J., Shah F., Gimble J.M., Lopez M.J., Eisig S.B., and Vunjak-Novakovic G. Tissue-engineered autologous grafts for facial bone reconstruction. Sci Transl Med 8, 343ra83, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner W.S., Wang X., Johnson S., Medberry C., Mendez J., Badylak S.F., McCord M.G., and McCloskey K.E. Cardiac tissue development for delivery of embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial and cardiac cells in natural matrices. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 100, 2060, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H., and Chiao M. Anti-fouling coatings of poly(dimethylsiloxane) devices for biological and biomedical applications. J Med Biol Eng 35, 143, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerbin K.A., Yang X., Murry C.E., and Coulombe K.L.K. Enhanced electrical integration of engineered human myocardium via intramyocardial versus epicardial delivery in infarcted rat hearts. PLoS One 10, e0131446, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bian W., and Bursac N. Engineered skeletal muscle tissue networks with controllable architecture. Biomaterials 30, 1401, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilchrist C.L., Ruch D.S., Little D., and Guilak F. Micro-scale and meso-scale architectural cues cooperate and compete to direct aligned tissue formation. Biomaterials 35, 10015, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liau B., Christoforou N., Leong K.W., and Bursac N. Pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac tissue patch with advanced structure and function. Biomaterials 32, 9180, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helm P., Beg M., Miller M.I., and Winslow R.L. Measuring and mapping cardiac fiber and laminar architecture using diffusion tensor MR imaging. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1047, 296, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadota S., Minami I., Morone N., Heuser J.E., Agladze K., and Nakatsuji N. Development of a reentrant arrhythmia model in human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac cell sheets. Eur Heart J 34, 1147, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munarin F., and Coulombe K.L.K. A novel 3-dimensional approach for cardiac regeneration. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2015, 1741, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H., Svoronos A.A., Boudou T., Sakar M.S., Schell J.Y., Morgan J.R., et al. Necking and failure of constrained 3D microtissues induced by cellular tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 20923, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng Z., Wagatsuma Y., Kikuchi M., Kosawada T., Nakamura T., Sato D., et al. The mechanisms of fibroblast-mediated compaction of collagen gels and the mechanical niche around individual fibroblasts. Biomaterials 35, 8078, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bian W., Badie N., Himel H.D., and Bursac N. Robust T-tubulation and maturation of cardiomyocytes using tissue-engineered epicardial mimetics. Biomaterials 35, 3819, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bian W., Jackman C.P., and Bursac N. Controlling the structural and functional anisotropy of engineered cardiac tissues. Biofabrication 6, 024109, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grosberg A., and Gharib M. A dynamic double helical band as a model for cardiac pumping. Bioinspir Biomim 4, 026003, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenton F.H., Cherry E.M., Hastings H.M., and Evans S.J. Multiple mechanisms of spiral wave breakup in a model of cardiac electrical activity. Chaos 12, 852, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ursell P.C., Gardner P.I., Albala A., Fenoglio J.J., Jr., and Wit A.L. Structural and electrophysiological changes in the epicardial border zone of canine myocardial infarcts during infarct healing. Circ Res 56, 436, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooks D.A., Tomlinson K.A., Marsden S.G., LeGrice I.J., Smaill B.H., Pullan A.J., and Hunter P.J. Cardiac microstructure: implications for electrical propagation and defibrillation in the heart. Circ Res 91, 331, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janse M.J. Electrophysiology of arrhythmias. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 92 Spec No 1, 9, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janse M.J. Electrophysiological changes in heart failure and their relationship to arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc Res 61, 208, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zipes D.P., Heger J.J., and Prystowsky E.N. Pathophysiology of arrhythmias: clinical electrophysiology. Am Heart J 106, 812, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elson J., and Mason J.W. General concepts and mechanisms of ventricular tachycardia. Cardiol Clin 4, 459, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevenson W.G. Mechanisms and management of arrhythmias in heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol 10, 274, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ducceschi V., Di Micco G., Sarubbi B., Russo B., Santangelo L., and Iacono A. Ionic mechanisms of ischemia-related ventricular arrhythmias. Clin Cardiol 19, 325, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilmour R.F., Jr., Gelzer A.R., and Otani N.F. Cardiac electrical dynamics: maximizing dynamical heterogeneity. J Electrocardiol 40, S51, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noujaim S.F., Auerbach D.S., and Jalife J. Ventricular fibrillation: dynamics and ion channel determinants. Circ J 71 Suppl A, A1, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmermann W.-H., Melnychenko I., and Eschenhagen T. Engineered heart tissue for regeneration of diseased hearts. Biomaterials 25, 1639, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wendel J.S., Ye L., Zhang P., Tranquillo R.T., and Zhang J.J. Functional consequences of a tissue-engineered myocardial patch for cardiac repair in a rat infarct model. Tissue Eng Part A 20, 1325, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinberger F., Breckwoldt K., Pecha S., Kelly A., Geertz B., Starbatty J., Yorgan T., Cheng K.-H., Lessmann K., Stolen T., Scherrer-Crosbie M., Smith G., Reichenspurner H., Hansen A., and Eschenhagen T. Cardiac repair in guinea pigs with human engineered heart tissue from induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Transl Med 8, 363ra148, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toepke M.W., and Beebe D.J. PDMS absorption of small molecules and consequences in microfluidic applications. Lab Chip 6, 1484, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su X., Young E.W.K., Underkofler H.A.S., Kamp T.J., January C.T., and Beebe D.J. Microfluidic cell culture and its application in high throughput drug screening: cardiotoxicity assay for hERG channels. J Biomol Screen 16, 101, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts M.A., Tran D., Coulombe K.L.K., Razumova M., Regnier M., Murry C.E., and Zheng Y. Stromal cells in dense collagen promote cardiomyocyte and microvascular patterning in engineered human heart tissue. Tissue Eng Part A 22, 633, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gwyther T.A., Hu J.Z., Christakis A.G., Skorinko J.K., Shaw S.M., Billiar K.L., and Rolle M.W. Engineered vascular tissue fabricated from aggregated smooth muscle cells. Cells Tissues Organs 194, 13, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blakely A.M., Manning K.L., Tripathi A., and Morgan J.R. Bio-pick, place, and perfuse: a new instrument for three-dimensional tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 21, 737, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandal B.B., Grinberg A., Seok Gil E., Panilaitis B., and Kaplan D.L. High-strength silk protein scaffolds for bone repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 7699, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang N.J., Yeh M.L., and Jhung Y.R. Fabricating PLGA sponge scaffold integrated with gelatin/hyaluronic acid for engineering cartilage. IEEE 35th Annual Northeast Bioengineering Conference 2009, 1, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X., You C., Hu X., Zheng Y., Li Q., Feng Z., Sun H., Gao C., and Han C. The roles of knitted mesh-reinforced collagen-chitosan hybrid scaffold in the one-step repair of full-thickness skin defects in rats. Acta Biomater 9, 7822, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burridge P.W., Matsa E., Shukla P., Lin Z.C., Churko J.M., Ebert A.D., Lan F., Diecke S., Huber B., Mordwinkin N.M., Plews J.R., Abilez O.J., Cui B., Gold J.D., and Wu J.C. Chemically defined and small molecule-based generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods 11, 855, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lian X., Hsiao C., Wilson G., Zhu K., Hazeltine L.B., Azarin S.M., Raval K.K., Zhang J., Kamp T.J., and Palecek S.P. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, E1848, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Desroches B.R., Zhang P., Choi B.R., King M.E., Maldonado A.E., Li W., Rago A., Liu G., Nath N., Hartmann K.M., Yang B., Koren G., Morgan J.R., and Mende U. Functional scaffold-free 3-D cardiac microtissues: a novel model for the investigation of heart cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302, H2031, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi B.R., Jang W., and Salama G. Spatially discordant voltage alternans cause wavebreaks in ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 4, 1057, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziv O., Morales E., Song Y.K., Peng X., Odening K.E., Buxton A.E., Karma A., Koren G., and Choi B.R. Origin of complex behaviour of spatially discordant alternans in a transgenic rabbit model of type 2 long QT syndrome. J Physiol 587, 4661, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.