Abstract

BACKGROUND

In multicenter studies, tight glycemic control targeting a normal blood glucose level has not been shown to improve outcomes in critically ill adults or children after cardiac surgery. Studies involving critically ill children who have not undergone cardiac surgery are lacking.

METHODS

In a 35-center trial, we randomly assigned critically ill children with confirmed hyperglycemia (excluding patients who had undergone cardiac surgery) to one of two ranges of glycemic control: 80 to 110 mg per deciliter (4.4 to 6.1 mmol per liter; lower-target group) or 150 to 180 mg per deciliter (8.3 to 10.0 mmol per liter; higher-target group). Clinicians were guided by continuous glucose monitoring and explicit methods for insulin adjustment. The primary outcome was the number of intensive care unit (ICU)–free days to day 28.

RESULTS

The trial was stopped early, on the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring board, owing to a low likelihood of benefit and evidence of the possibility of harm. Of 713 patients, 360 were randomly assigned to the lower-target group and 353 to the higher-target group. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the median number of ICU-free days did not differ significantly between the lower-target group and the higher-target group (19.4 days [interquartile range {IQR}, 0 to 24.2] and 19.4 days [IQR, 6.7 to 23.9], respectively; P = 0.58). In per-protocol analyses, the median time-weighted average glucose level was significantly lower in the lower-target group (109 mg per deciliter [IQR, 102 to 118]; 6.1 mmol per liter [IQR, 5.7 to 6.6]) than in the higher-target group (123 mg per deciliter [IQR, 108 to 142]; 6.8 mmol per liter [IQR, 6.0 to 7.9]; P<0.001). Patients in the lower-target group also had higher rates of health care–associated infections than those in the higher-target group (12 of 349 patients [3.4%] vs. 4 of 349 [1.1%], P = 0.04), as well as higher rates of severe hypoglycemia, defined as a blood glucose level below 40 mg per deciliter (2.2 mmol per liter) (18 patients [5.2%] vs. 7 [2.0%], P = 0.03). No significant differences were observed in mortality, severity of organ dysfunction, or the number of ventilator-free days.

CONCLUSIONS

Critically ill children with hyperglycemia did not benefit from tight glycemic control targeted to a blood glucose level of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter, as compared with a level of 150 to 180 mg per deciliter.

Tight glycemic control to a blood glucose level of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter (4.4 to 6.1 mmol per liter) was originally shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in a single-center, randomized clinical trial involving critically ill adult surgical patients,1 but subsequent trials involving adults have not shown benefit. 2–4 Results of trials of tight glycemic control in critically ill children have been inconsistent5–8; retrospective studies have consistently shown an association between hyperglycemia and poor outcomes. 9–12 A single-center, randomized trial involving children, most of whom had undergone cardiac surgery, showed significantly lower mortality and infection rate and shorter length of stay with lower glucose targets than with higher glucose targets, despite high rates of severe hypoglycemia (blood glucose level, <40 mg per deciliter [2.2 mmol per liter]).5 Other investigators found significantly lower morbidity with lower glucose targets than with higher glucose targets in pediatric patients with burns.8 Multicenter trials of tight glucose control involving children have included mostly patients who have undergone cardiac surgery and have not shown lower mortality, shorter length of stay, or fewer health care–associated infections with lower glucose targets than with conventional glucose control6 or standard care7 but have shown lower 12-month health care costs.6

A survey of pediatric intensivists identified wide variation in glycemic control practice and equipoise between lower and higher glucose targets, which justifies further study.13 Pediatric intensivists indicated that safe adjustment of continuous intravenous insulin to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia was crucial.10,11,13 Thus, the current Heart and Lung Failure–Pediatric Insulin Titration (HALF-PINT) trial tested the hypothesis that tight glycemic control to a target range of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter (lower target) versus a target range of 150 to 180 mg per deciliter (8.3 to 10.0 mmol per liter; higher target) would increase the number of intensive care unit (ICU)–free days in critically ill children with hyperglycemia who have cardiovascular or respiratory failure; the trial targeted an enriched cohort of pediatric patients in the ICU who could benefit most from tight glucose control — those with the greatest risk of death and longest lengths of stay.14,15 Continuous glucose monitoring and computer-guided insulin adjustment were used to minimize hypoglycemia.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND OVERSIGHT

A total of 35 centers screened children 2 weeks to 17 years of age who were receiving vasoactive support for hypotension or invasive mechanical ventilation. Only patients with a measured blood glucose level greater than 130 mg per deciliter were assessed for exclusion criteria. We excluded children who had diabetes, those who had inadequate vascular access, and those who had undergone cardiac surgery. Children underwent randomization at 32 sites (see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org).

A data and safety monitoring board, whose members were appointed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, monitored trial data and oversaw patients’ safety. Central ethics review was coordinated by the institutional review board at Boston Children’s Hospital, with appropriate signed institutional reliance agreements. A total of 10 study sites established reliance relationships; at the remaining sites, oversight was conducted by a local institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians, and assent was obtained from patients when appropriate.

All the authors participated in the design of the study and vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol (available at NEJM.org). Nova Biomedical provided glucose meters (Nova StatStrip), test strips, management software, and training support at no cost, and Edwards Life-sciences provided closed blood-sparing sampling systems (VAMP Jr. System) at no cost. Dexcom provided continuous glucose-monitoring systems and sensors (G4 Platinum) at a reduced rate, and Medtronic MiniMed provided continuous glucose-monitoring systems and sensors (Guardian REAL-Time and Enlite) at a reduced rate. These companies were not involved in the study design or drafting of the manuscript and did not review the manuscript before it was submitted for publication.

INTERVENTIONS AND OUTCOMES

A detailed description of the study methods was published previously.16 Patients were randomly assigned, with the use of a central computer, to receive tight glucose control with a target of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter (lower-target group) or 150 to 180 mg per deciliter (higher-target group), with continuous intravenous insulin adjusted to maintain the blood glucose level in the target range. Randomization was performed according to a permuted-block design with stratification according to study site. Bedside clinicians were aware of the study-group assignments, given the need to manage insulin therapy. The intervention began in each patient when hyperglycemia was confirmed (two consecutive blood glucose levels of ≥150 mg per deciliter) and ended when the patient met study-defined, site-independent criteria for ICU discharge, including the discontinuation of vasoactive infusions and invasive mechanical ventilation or noninvasive ventilation that provided at least 5 cm of water pressure, or after 28 days, whichever came first.

The blood glucose level was controlled with the use of continuous intravenous regular human insulin. The timing of blood glucose measurements, dosing of insulin, and glucose rescue boluses were guided by the bedside computerized Children’s Hospital Euglycemia for Kids Spreadsheet (CHECKS)7,17 protocol (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Blood glucose was measured with the use of an identical glucose meter at all the study sites, after blood was drawn through a closed blood-sparing system, preferentially from an existing arterial catheter. Continuous glucose monitoring was used to signal impending hypoglycemia.18–20 These specific devices were incorporated into the study design to mitigate the risk of hypoglycemia, to ensure consistency across centers, and to address limitations of previous studies.21,22 Age-based minimum glucose-infusion rates were recommended at 5 mg (0.3 mmol) per kilogram of body weight per minute in patients younger than 6 years of age and at 2.5 mg (0.1 mmol) per kilogram per minute in patients 6 years of age or older.23 Site staff were supported by the Clinical Coordinating Center with live computer support, a 24-hour telephone hotline, and automatic messaging to alert staff of defined events, such as severe hypoglycemia.

The primary outcome was the number of ICU-free days to day 28, which is the inverse equivalent of 28-day hospital mortality–adjusted ICU length of stay.2,4,24–26 The number of ICU-free days was considered to be zero for children who did not meet the ICU discharge criteria or who were transferred or died by day 28. Secondary outcomes included 90-day mortality, severity of organ dysfunction (according to the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction [PELOD] score27), the number of ventilator-free days to day 28, the incidence of health care–associated infection according to current published definitions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),28 and the incidence of hypoglycemia. Health care–associated infections were adjudicated by local independent infectious disease officers, who were responsible for reporting ICU-associated infections to national surveillance programs. These officers were not formally unaware of the study-group assignments. Nutritional intake and indexes of glycemic control were tracked during the period of ICU stay, according to a priori definitions.16

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We calculated the sample size on the basis of the primary outcome measure of the number of ICU-free days to day 28, using an estimated hospital mortality of 8% and a mean ICU length of stay of 8.5 days in the higher-target group, as calculated from the Pediatric Intensive Care Audit Network database.29,30 We estimated that to achieve 90% power at the 5% level of significance, with three interim analyses, we would have to enroll 1880 patients in the study to detect 20% lower mortality and 1 day shorter ICU length of stay with the lower target than with the higher target. This would equate to 1.25 more ICU-free days with the lower target than with the higher target (19.19 vs. 17.94). Given a slower-than-expected enrollment after 3 years, the sample size was revised to achieve 80% power with 1414 patients.

Analysis of the primary outcome was performed on an intention-to-treat basis and used proportional-hazards regression with adjustment for age group and severity of illness in the first 12 hours of ICU stay (as assessed with the use of the Pediatric Risk of Mortality [PRISM] III-12 score31). Additional analyses were performed on a per-protocol basis, which excluded patients who had undergone randomization and never received the intervention and those whose guardian withdrew full consent.

The characteristics of the patients at baseline and the glycemia and insulin therapy variables were compared with the use of Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and Fisher’s exact tests. Data on glycemic control included all blood glucose levels as measured with a bedside glucose meter. Sensor measurements were used whenever glucose-meter measurements were unavailable. Time-weighted glucose averages were calculated from serial measurements. Glucose measurements were interpolated at half-hour intervals from available measurements; the time to the target range (from randomization to the first measured glucose level in the target range) and the percentage of time in the target range were calculated from the interpolated curves. Other analyses used proportional-hazards regression for time-to-event outcomes, linear regression for continuous outcomes, and logistic regression for binary outcomes, with adjustment for age group and severity of illness. All P values are two-tailed and have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons. Analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute); StatXact software, version 11.1 (Cytel); East software, version 6.4 (Cytel); and GraphPad Prism software, version 7.00 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Enrollment began in April 2012 and ended in September 2016. The recruitment was stopped early at 50% enrollment. Although the data did not cross prespecified efficacy or futility boundaries, conditional power analyses showed a 1% chance of detecting a significant result even if the number of ICU-free days was 1.25 days longer in the lower-target group than in the higher-target group with 100% enrollment (see the Supplementary Appendix). On the basis of all available data, the data and safety monitoring board recommended halting the trial.

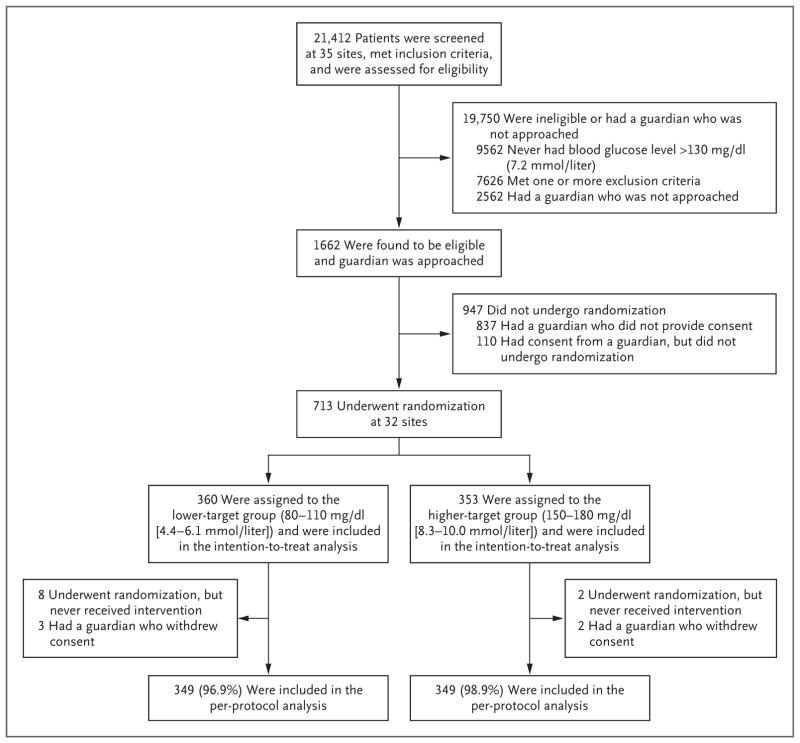

A total of 713 patients underwent randomization at 32 sites. A total of 360 patients were assigned to the lower-target range, and 353 to the higher-target range; these patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis of the primary outcome (Fig. 1, and Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Ten patients were withdrawn by study staff before the intervention owing to a change in eligibility status, and 5 whose guardians withdrew full consent were not included in the per-protocol analyses; thus, the per-protocol analysis included 698 patients (349 patients in each group). The characteristics of the patients in the two study groups were similar at baseline (Table 1).

Figure 1. Assessment, Randomization, and Follow-up of the Study Patients.

The informed-consent rate was 50% (825 of 1662 patients). Only patients with a measured blood glucose level greater than 130 mg per deciliter were assessed for exclusion criteria. Two additional patients underwent randomization and were in the study when it was stopped early; these patients are not included in the analyses according to the stipulation of the data and safety monitoring board. Additional details are provided in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Patients at Baseline, According to Study Group.*

| Characteristic | Lower Target (N = 349) | Higher Target (N = 349) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at ICU admission | ||

| Median (IQR) — yr | 5.5 (1.4–12.5) | 6.7 (1.7–12.8) |

| Age group — no. (%) | ||

| <2 yr | 100 (28.7) | 101 (28.9) |

| 2 to <7 yr | 94 (26.9) | 82 (23.5) |

| 7 to <18 yr | 155 (44.4) | 166 (47.6) |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 164 (47.0) | 169 (48.4) |

| Black race — no./total no. (%)† | 86/336 (25.6) | 85/335 (25.4) |

| Hispanic ethnic group — no./total no. (%)† | 79/348 (22.7) | 82/347 (23.6) |

| Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category of 1 — no. (%)‡ | 242 (69.3) | 237 (67.9) |

| Pediatric Overall Performance Category of 1 — no. (%)‡ | 226 (64.8) | 217 (62.2) |

| Any known genetic syndrome — no. (%) | 59 (16.9) | 69 (19.8) |

| Primary reason for ICU admission — no. (%) | ||

| Respiratory, including infection | 182 (52.1) | 183 (52.4) |

| Cardiovascular, including shock | 58 (16.6) | 51 (14.6) |

| Neurologic | 30 (8.6) | 34 (9.7) |

| Traumatic | 35 (10.0) | 24 (6.9) |

| Postoperative care | 18 (5.2) | 31 (8.9) |

| Gastrointestinal or hepatic | 16 (4.6) | 15 (4.3) |

| Other§ | 10 (2.9) | 11 (3.2) |

| Insulin at randomization — no. (%) | 44 (12.6) | 57 (16.3) |

| Glucocorticoid therapy at randomization — no. (%) | 184 (52.7) | 178 (51.0) |

| Inotropic support for hypotension at randomization — no. (%) | 182 (52.1) | 168 (48.1) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization — no. (%) | ||

| Endotracheal tube | 336 (96.3) | 331 (94.8) |

| Tracheostomy | 8 (2.3) | 13 (3.7) |

| None | 5 (1.4) | 5 (1.4) |

| ECMO at randomization — no. (%) | 13 (3.7) | 20 (5.7) |

| PRISM III-12 score¶ | ||

| Median | 12 | 12 |

| IQR | 7–19 | 7–18 |

| Risk of death in the ICU, according to PRISM III-12 score — % | ||

| Median | 11.7 | 9.5 |

| IQR | 2.7–39.1 | 2.9–30.9 |

Patients in the lower-target group had their blood glucose level controlled to a target range of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter (4.4 to 6.1 mmol per liter), and those in the higher-target group to a target range of 150 to 180 mg per deciliter (8.3 to 10.0 mmol per liter). There were no significant between-group differences in the characteristics at baseline in the perprotocol population. ECMO denotes extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ICU intensive care unit, and IQR interquartile range.

Race and ethnic group were as reported in the medical record.

The scales for the Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category and Pediatric Overall Performance Category range from 1 to 6, with lower scores indicating less disability.

Other includes oncologic, renal, metabolic, and hematologic reasons.

The scale for the Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score from the first 12 hours in the ICU (the PRISM III-12 score) ranges from 0 to 74, with higher scores indicating a higher risk of death.

INSULIN TREATMENT AND BLOOD GLUCOSE MANAGEMENT

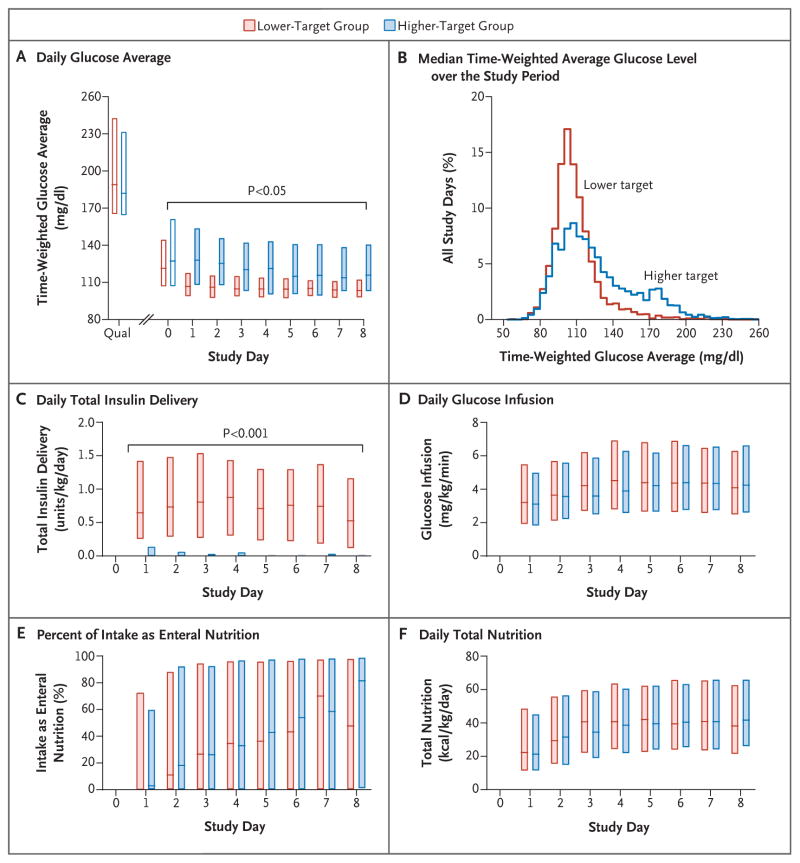

The blood glucose measurements that qualified patients for randomization were similar in the lower-target group and the higher-target group (median, 189 mg per deciliter [interquartile range, 165 to 243] and 182 mg per deciliter [interquartile range, 164 to 232], respectively [10.5 mmol per liter {interquartile range, 9.2 to 13.5} and 10.1 mmol per liter {interquartile range, 9.1 to 12.9}, respectively]; P = 0.25) (Fig. 2A and Table 2). The measurements at the start of the intervention were also similar in the lower-target group and the higher-target group (133 mg per deciliter [interquartile range, 110 to 160] and 131 mg per deciliter [interquartile range, 107 to 165], respectively [7.4 mmol per liter {interquartile range, 6.1 to 8.9} and 7.3 mmol per liter {interquartile range, 5.9 to 9.2}, respectively]; P = 0.80).

Figure 2. Glucose, Insulin, and Nutrition Levels, According to Study Group.

Daily data are for the first 8 study days (the median duration of stay in the intensive care unit). Panel A shows time-weighted glucose averages obtained from a linear interpolation of the glucose values that were used to administer the tight-glycemic-control protocol. Open bars indicate either the value used to qualify for the study (Qual) or a partial study day (day 0, the day of randomization), and shaded bars indicate full study days (midnight to 11:59 p.m.). To convert values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551. Panel B shows the median time-weighted average glucose level over the entire study period. Panel C shows the daily total insulin delivery, Panel D the daily glucose-infusion rates, Panel E the daily percentage of total nutrition given enterally, and Panel F the daily total nutrition. In each panel, the boxes represent the interquartile range, and the horizontal lines the median. P values for the comparison between groups were calculated with the use of Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (without adjustment for multiple comparisons).

Table 2.

Glycemia and Insulin Therapy after Randomization, According to Study Group.*

| Variable | Lower Target (N = 349) | Higher Target (N = 349) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| First qualifying blood glucose level — mg/dl | 0.25 | ||

|

| |||

| Median | 189 | 182 | |

| IQR | 165–243 | 164–232 | |

|

| |||

| Duration from first qualifying blood glucose level to randomization — hr | 0.37 | ||

| Median | 19.7 | 19.4 | |

| IQR | 12.5–28.8 | 11.9–26.2 | |

|

| |||

| Blood glucose level at start of intervention — mg/dl | 0.80 | ||

| Median | 133 | 131 | |

| IQR | 110–160 | 107–165 | |

|

| |||

| Treated with insulin therapy — no. of patients (%) | 344 (98.6) | 215 (61.6) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| No. of days of insulin therapy | <0.001 | ||

| Median | 5 | 1 | |

| IQR | 3–9 | 0–4 | |

|

| |||

| Average daily insulin dose — units/kg/day | <0.001 | ||

| Median | 0.74 | 0.01 | |

| IQR | 0.37–1.20 | 0.00–0.14 | |

|

| |||

| Adherence to protocol recommendations — no. of recommendations/total no. (%) | 49,835/51,212 (97.3) | 49,921/50,329 (99.2) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| No. of average daily glucose measurements | <0.001 | ||

| Median | 17.4 | 7.0 | |

| IQR | 13.9–19.6 | 5.5–11.5 | |

|

| |||

| Time to the target range — hr | <0.001 | ||

| Median | 5.5 | 1.5 | |

| IQR | 2.5–11.5 | 0.5–3.0 | |

|

| |||

| Time in the target range — % of time | <0.001 | ||

| Median | 57 | 91 | |

| IQR | 43–67 | 81–96 | |

|

| |||

| Time-weighted glucose average — mg/dl | |||

| Median | 109 | 123 | <0.001 |

| IQR | 102–118 | 108–142 | |

|

| |||

| Hypoglycemia — no. of patients (%)‡ | |||

|

| |||

| Severe | |||

|

| |||

| All | 18 (5.2) | 7 (2.0) | 0.03 |

| Unrelated | 5 (1.4) | 6 (1.7) | 0.71 |

| Related | 13 (3.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Any | |||

|

| |||

| All | 79 (22.6) | 33 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Unrelated | 26 (7.4) | 29 (8.3) | 0.62 |

| Related | 64 (18.3) | 5 (1.4) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Hypokalemia — no. of patients (%)§ | 76 (21.8) | 64 (18.3) | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| Insulin-dosing error — no. of patients (%) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0.37 |

To convert values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551.

For hypoglycemia and hypokalemia, P values for the comparison between treatment groups were calculated with the use of logistic regression with adjustment for age group and PRISM III-12 score. For other variables, P values were calculated with the use of the Wilcoxon rank-sum or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, in the per-protocol population.

Severe hypoglycemia was defined as a blood glucose level below 40 mg per deciliter (2.2 mmol per liter), and any hypoglycemia as a blood glucose level below 60 mg per deciliter (3.3 mmol per liter). Hypoglycemia was considered by the investigators to be related or unrelated to insulin administration according to prospectively defined criteria.16 Patients may have had both unrelated and related hypoglycemia events, so the sums of the values in those categories may exceed the overall total.

Hypokalemia was defined as a potassium level below 2.5 mmol per liter.

There was significant separation of blood glucose levels between the groups for the first 18 days of the intervention (P<0.05 for each daily comparison) (Fig. S2 in Supplementary Appendix). The median time-weighted average glucose level over the study period was 109 mg per deciliter in the lower-target group (interquartile range, 102 to 118 [6.1 mmol per liter {interquartile range, 5.7 to 6.6}]), as compared with 123 mg per deciliter in the higher-target group (interquartile range, 108 to 142 [6.8 mmol per liter {interquartile range, 6.0 to 7.9}]) (P<0.001) (Fig. 2B).

Nearly all the patients in the lower-target group (344 of 349 patients [98.6%]) received insulin therapy per protocol, with a median dose of 0.74 units per kilogram per day over the study period, as compared with 215 of 349 patients in the higher-target group (61.6%) with a median dose of 0.01 units per kilogram per day (Fig. 2C). Bedside clinicians were highly adherent to the insulin-dosing recommendations of the CHECKS protocol (49,835 of 51,212 recommendations [97.3%] in the lower-target group vs. 49,921 of 50,329 [99.2%] in the higher-target group, P<0.001). In addition to continuous glucose monitoring, providers performed more blood glucose measurements per 24-hour period in the lower-target group (median, 17.4 measurements [interquartile range, 13.9 to 19.6]) than in the higher-target group (median, 7.0 measurements [interquartile range, 5.5 to 11.5] (P<0.001).

Severe hypoglycemia (blood glucose level, <40 mg per deciliter) that was considered by the investigators, according to prospectively defined criteria,16 to be related to insulin administration occurred in 13 of 349 patients (3.7%) in the lower-target group, as compared with 1 of 349 (0.3%) in the higher-target group (P = 0.01). With the inclusion of instances in which severe hypoglycemia was considered to be unrelated to insulin administration, the total incidence was higher in the lower-target group than in the higher-target group (18 patients [5.2%] vs. 7 [2.0%], P = 0.03). Three patients, all of whom had had seizure activity in the ICU before enrollment in the trial, had seizures during an episode of hypoglycemia. No other complications of hypoglycemia were reported. The incidence of hypokalemia (potassium level, <2.5 mmol per liter32) was similar in the two groups.

NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT

Over the first 8 study days (the median length of ICU stay), the glucose-infusion rates, the percentage of intake as enteral nutrition, and the level of total nutrition were similar in the two groups (Fig. 2D, 2E, and 2F). By the eighth day, patients in the lower-target group and those in the higher-target group were receiving more than half their intake as enteral feedings, with similar caloric content (median, 38 kcal per kilogram per day [interquartile range, 21 to 63] and 42 kcal per kilogram per day [interquartile range, 26 to 66], respectively; P = 0.36). Over the entire study period, patients in the lower-target group and those in the higher-target group received a similar percentage of their nutrition enterally (53% [interquartile range, 3 to 86] and 55% [interquartile range, 6 to 88], respectively; P = 0.46). The median glucose-infusion rates over the study period were consistent with study recommendations in the combined treatment groups (5.6 mg per kilogram per minute [interquartile range, 3.8 to 7.0] [0.3 mmol per kilogram per minute {interquartile range, 0.2 to 0.4}] in patients <6 years of age, and 2.6 mg per kilogram per minute [interquartile range, 1.9 to 3.6] [0.1 mmol per kilogram per minute {interquartile range, 0.1 to 0.2}] in those ≥6 years of age).

OUTCOMES

In the intention-to-treat analysis that included 713 patients, the median number of ICU-free days did not differ significantly between the lower-target group and the higher-target group (19.4 days [interquartile range, 0 to 24.2] and 19.4 days [interquartile range, 6.7 to 23.9], respectively; P = 0.58) (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). In the per-protocol analysis involving 698 patients, the median number of ICU-free days also did not differ significantly between the lower-target group and the higher-target group (20.0 days [interquartile range, 1.0 to 24.2] and 19.4 days [interquartile range, 7.1 to 23.9], respectively; P = 0.86) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Study Outcomes and Adverse Events, According to Study Group, in the Per-Protocol Population.

| Variable | Lower Target (N = 349) | Higher Target (N = 349) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of ICU-free days through day 28 | 0.86 | ||

|

| |||

| Median | 20.0 | 19.4 | |

| IQR | 1.0–24.2 | 7.1–23.9 | |

|

| |||

| Assigned zero ICU-free days — no. (%) | 87 (24.9) | 70 (20.1) | 0.14 |

| Died by day 28 | 47 (13.5) | 32 (9.2) | |

| Did not meet ICU discharge criteria by day 28 | 33 (9.5) | 37 (10.6) | |

| Transferred to an ICU in a nonparticipating institution by day 28 | 7 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

|

| |||

| No. of ventilator-free days through day 28 | 0.84 | ||

| Median | 21.8 | 20.9 | |

| IQR | 8.4–25.0 | 11.9–24.4 | |

|

| |||

| No. of hospital-free days through day 28 | 0.60 | ||

| Median | 8 | 6 | |

| IQR | 0–17 | 0–16 | |

|

| |||

| Hospital mortality — no. (%) | |||

| At day 28 | 47 (13.5) | 32 (9.2) | 0.09 |

| At day 90 | 52 (14.9) | 40 (11.5) | 0.22 |

|

| |||

| Maximum PELOD score† | 0.38 | ||

| Median | 13 | 13 | |

| IQR | 11–23 | 11–22 | |

|

| |||

| Maximum daily vasoactive-inotrope score33 | 0.55 | ||

| Median | 5 | 4 | |

| IQR | 0–15 | 0–13 | |

|

| |||

| New seizure — no. (%) | 5 (1.4) | 10 (2.9) | 0.20 |

|

| |||

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation — no. (%) | 10 (2.9) | 11 (3.2) | 0.80 |

|

| |||

| New ECMO initiated after randomization — no. (%) | 8 (2.3) | 5 (1.4) | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| Glucocorticoid therapy after randomization — no. (%) | 264 (75.6) | 269 (77.1) | 0.56 |

|

| |||

| Renal-replacement therapy — no. (%) | 41 (11.7) | 31 (8.9) | 0.19 |

|

| |||

| Red-cell transfusion — no. (%) | 158 (45.3) | 150 (43.0) | 0.62 |

|

| |||

| Empirical or treatment antibiotic agent — no. (%) | 326 (93.4) | 338 (96.8) | 0.04 |

|

| |||

| Health care–associated infection — no. (%) | 12 (3.4) | 4 (1.1) | 0.04 |

|

| |||

| Catheter-associated bloodstream infection | 0.03‡ | ||

| Events — no./no. of central-venous-catheter–days | 5/2577 | 0/2784 | |

| Rate per 1000 central-venous-catheter–days | 1.94 | 0 | |

|

| |||

| Catheter-associated urinary tract infection | 1.0‡ | ||

| Events — no./no. of bladder-catheter–days | 5/2287 | 4/2230 | |

| Rate per 1000 bladder-catheter–days | 2.19 | 1.79 | |

|

| |||

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 0.11‡ | ||

| Events — no./no. of ventilator-days | 3/3182 | 0/3371 | |

| Rate per 1000 ventilator-days | 0.94 | 0 | |

|

| |||

| All infections with positive cultures — no. (%)§ | 29 (8.3) | 34 (9.7) | 0.52 |

P values for the comparison between treatment groups were calculated with the use of proportional-hazards, linear, or logistic regression with adjustment for age group and PRISM III-12 score, as appropriate, except where noted.

Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD) scores range from 0 to 71, with higher scores indicating more severe multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Owing to zero counts or low event frequency, the P value was calculated with the use of exact Poisson regression.

All infections include health care–associated infection as well as upper respiratory tract infection (e.g. tracheitis), lower respiratory tract infection not associated with ventilator (e.g. pneumonia), bloodstream infection not associated with catheter, colitis, urinary tract infection not associated with a urinary catheter, other wound infection, abdominal abscess, empyema, meningitis, and neck abscess.

Secondary outcomes are reported according to the per-protocol analysis (Table 3). Of these, a significantly higher incidence of total health care–associated infections was noted in the lower-target group than in the higher-target group (12 of 349 patients [3.4%] vs. 4 of 349 [1.1%], P = 0.04) — specifically, a higher rate of catheter-associated bloodstream infections in the lower-target group (1.94 vs. 0 infections per 1000 central-venous-catheter–days, P = 0.03). The incidence of all culture-positive infections, including those that did not meet the CDC definitions of health care–associated infection, did not differ significantly between the lower-target group and the higher-target group (29 patients [8.3%] and 34 patients [9.7%], respectively; P = 0.52). Conversely, empirical treatment with antibiotic agents without specific positive cultures was widespread and was slightly less common in the lower-target group than in the higher-target group (326 patients [93.4%] vs. 338 [96.8%], P = 0.04).

Mortality at 28 days was non-significantly higher in the lower-target group than in the higher-target group (47 of 349 patients [13.5%] and 32 of 349 [9.2%], respectively; P = 0.09) and did not differ significantly between groups at 90 days (52 [14.9%] and 40 [11.5%], respectively; P = 0.22). No significant between-group differences were found in the number of ventilator-free days (P = 0.84) or the number of hospital-free days (P = 0.60). Other markers of the severity of illness were elevated similarly in the two groups, including the maximum PELOD score (P = 0.38), the maximum daily vasoactive-inotrope score (P = 0.55), the incidence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (P = 0.80), and cannulation for the delivery of extracorporeal life support (P = 0.37). There were no associations between health care–associated infection, severe hypoglycemia, or any hypoglycemia with either 28-day or 90-day hospital mortality (P>0.05 for all comparisons by Fisher’s exact test). Adjustment for study site did not appreciably change the results.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter, randomized trial, we found no significant difference in the number of ICU-free days (or 28-day hospital mortality–adjusted length of stay in the ICU) or in any secondary outcomes with tight glucose control targeted to a blood glucose level of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter versus a level of 150 to 180 mg per deciliter. The enriched cohort of critically ill children with hyperglycemia had higher mortality at 90 days (13.2%) and a longer length of stay in the ICU (approximately 8 days) than in previous studies of tight glucose control in children.5–7,14,15 The 28-day hospital mortality was non-significantly higher in the lower-target group than in the higher-target group (P = 0.09), and the between-group difference in hospital mortality was not significant at 90 days. There was no association between mortality and rates of infection or hypoglycemia.

There was a higher incidence of CDC-defined health care–associated infections, specifically catheter-associated bloodstream infections, in the lower-target group than in the higher-target group. However, there was no significant between-group difference in the overall incidence of culture-positive infection, according to definitions reported in previous studies of tight glucose control.5,6 Although a higher incidence of bloodstream infections might be biologically plausible, given the greater frequency of glucose testing in the lower-target group, the overall profile of infectious outcomes is unexplained.

The strengths of the trial include 35 recruiting sites, explicit methods to control glucose and limit hypoglycemia, extensive standardized training of clinicians, and remote support with continuous quality monitoring from the Clinical Coordinating Center. Thus, the protocol was explicit and reproducible, and the rate of adherence to the protocol was high. Glucose control was achieved quickly after randomization, with significant separation in glucose levels between the groups for almost 3 weeks. The rates of severe hypoglycemia were low, as compared with other studies of tight glucose control.2,4,5,6

The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that targeting a blood glucose level of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter would be superior to consensus recommendations from published critical care and endocrine societies (blood glucose levels of 150 to 180 mg per deciliter,34 140 to 180 mg per deciliter [7.8 to 10.0 mmol per liter],35 and 140 to 200 mg per deciliter [7.8 to 11.1 mmol per liter]36). Our survey of pediatric intensivists indicated that there was equipoise between higher-target and lower-target ranges, that the use of a “no glycemic control” group was unacceptable, and that intensivists were not willing to infuse dextrose to elevate the glucose level intentionally above 150 mg per deciliter. Thus, the trial was a practical, replicable test of insulin therapy that was targeted to two ranges in an enriched population of critically ill children with hyperglycemia, rather than a glycemic clamp trial comparing glycemia at two ranges. The difference in glycemia that was observed between the lower-target group and the higher-target group (109 vs. 123 mg per deciliter) was similar to that observed in previous multicenter trials involving children (107 vs. 114 mg per deciliter [5.9 vs. 6.3 mmol per liter]6 and 112 vs. 121 mg per deciliter [6.2 vs. 6.7 mmol per liter]7), although it was less pronounced than the between-group difference in a single-center trial (113 vs. 158 mg per deciliter [6.3 vs. 8.8 mmol per liter]5) in which early parenteral nutrition was routine and conventional treatment was associated with a higher incidence of hyperglycemia.

Our results are consistent with those from other multicenter trials involving other critically ill children. The SPECS (Safe Pediatric Euglycemia in Cardiac Surgery) trial7 and the CHiP (Control of Hyperglycaemia in Paediatric Intensive Care) trial6 showed no significant differences in ICU length of stay or mortality among children who had undergone cardiac surgery or in children who had not undergone cardiac surgery. The CHiP trial showed that among patients who had not undergone cardiac surgery, the mean 12-month health care costs were lower in the group that was assigned to a lower target blood glucose range than in the group that was assigned to conventional glycemic control, a finding that was most likely attributable to a shorter hospital stay for the index admission among those assigned to the lower target. Notably, the hospital length of stay in our trial did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Our results differ from those of a single-center study conducted in Leuven, Belgium,5 that showed substantially lower mortality, a shorter length of stay in the ICU, and a lower rate of infections with tight glucose control to lower glucose targets than to higher glucose targets, despite a significantly higher rate of severe hypoglycemia. Our study did not show any of these benefits, and the patients had less hypoglycemia overall, but the average glucose level in the higher-target group in our study was lower than the level in the higher-target group in the single-center study. In studies involving adults, an explanation for similar incongruities relates to differences in site-specific practices regarding parenteral nutrition.37 More recent findings in critically ill children indicate that the early initiation of parenteral nutrition leads to poorer outcomes than later initiation.38 The patients in the current study had a lower prevalence of parenteral nutrition than did those included in the trial conducted in Leuven.5

We ultimately planned for 1414 patients to be enrolled and to undergo randomization, on the basis of revised power calculations for 80% power, but the study was stopped after the first interim analysis, at 50% enrollment, because the data indicated a low likelihood of benefit and evidence of the possibility of harm (e.g., the non-significantly higher mortality, the health care–associated infection profile, and the risk of severe hypoglycemia) in the lower-target group. A conditional power analysis indicated that continuation of the trial had a negligible potential (1% chance) of arriving at a different conclusion.

The study used continuous monitoring and a computerized algorithm to minimize the incidence, severity, and duration of hypoglycemia, which is the most important risk of glycemic control. As in the SPECS trial, our study showed a low rate of severe hypoglycemia. Unlike in the SPECS trial, nearly half the episodes of severe hypoglycemia (11 of 25 patients) in our trial were judged to be unrelated to insulin infusion but to be related rather to underlying illness or the abrupt discontinuation of caloric supply.

Our study has certain limitations. First, informed consent was obtained only after hyperglycemia was confirmed, which created a delay between the onset and treatment of hyperglycemia. Second, it was not possible for the bedside team to be unaware of the study-group assignment. Concern for bias was mitigated by the explicitly defined intervention and primary outcome. Third, in order to compare two tight glucose-control targets within the range of usual care, we did not include a third group in which hyperglycemia was not treated. Thus, the two study groups had explicitly managed glucose and insulin adjustment.

In conclusion, in this multicenter, randomized trial involving a population of patients who had not undergone cardiac surgery, we found no significant between-group difference in the number of ICU-free days (or 28-day hospital mortality–adjusted ICU length of stay) or in any secondary outcomes when tight glycemic control with insulin administered to achieve a target blood glucose range of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter was compared with a target range of 150 to 180 mg per deciliter in critically ill children with hyperglycemia who had cardiovascular or respiratory failure. Significant differences in glycemia and insulin dose were observed. We conclude that in an enriched population of critically ill children with hyperglycemia, a blood glucose target of 150 to 180 mg per deciliter was associated with clinical outcomes that were similar to outcomes with a target of 80 to 110 mg per deciliter, with a lower risk of hypoglycemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants (U01HL107681-MA/VN and U01HL108028-DW) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, by endowed chairs (to Drs. Agus and Nadkarni), and by a departmental investigatorship (to Dr. Steil).

Funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and others; HALF-PINT ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01565941.

We thank the children who participated in this study and their parents and guardians, as well as the study coordinators at all the participating sites.

Appendix

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: Michael S.D. Agus, M.D., David Wypij, Ph.D., Eliotte L. Hirshberg, M.D., Vijay Srinivasan, M.D., E. Vincent Faustino, M.D., Peter M. Luckett, M.D., Jamin L. Alexander, B.A., Lisa A. Asaro, M.S., Martha A.Q. Curley, R.N., Ph.D., Garry M. Steil, Ph.D., and Vinay M. Nadkarni, M.D.

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: the Division of Medicine Critical Care (M.S.D.A., J.L.A., G.M.S.) and the Department of Cardiology (D.W., L.A.A.), Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston; the Division of Pediatric Critical Care, University of Utah Medical School, Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, and Intermountain Medical Center, Murray — both in Utah (E.L.H.); Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (V.S., V.M.N.) and the Perelman School of Medicine (V.S., M.A.Q.C., V.M.N.) and the School of Nursing (M.A.Q.C.), University of Pennsylvania — all in Philadelphia; Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT (E.V.F.); and Children’s Medical Center Dallas and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas (P.M.L.).

Footnotes

The authors’ full names, academic degrees, and affiliations are listed in the Appendix.

Drs. Agus and Steil report holding a pending patent related to methods and systems for managing diabetes (U.S. provisional patent number, 62/326,496); and Dr. Steil, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Becton, Dickinson, and Company, consulting fees from Roche, and continuous glucose monitors and sensors for use in another study from Dexcom. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1108–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preiser JC, Devos P, Ruiz-Santana S, et al. A prospective randomised multicentre controlled trial on tight glucose control by intensive insulin therapy in adult intensive care units: the Glucontrol study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1738–48. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1585-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vlasselaers D, Milants I, Desmet L, et al. Intensive insulin therapy for patients in paediatric intensive care: a prospective, randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2009;373:547–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macrae D, Grieve R, Allen E, et al. A randomized trial of hyperglycemic control in pediatric intensive care. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:107–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agus MSD, Steil GM, Wypij D, et al. Tight glycemic control versus standard care after pediatric cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1208–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeschke MG, Kulp GA, Kraft R, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in severely burned pediatric patients: a prospective randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:351–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0190OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faustino EV, Apkon M. Persistent hyperglycemia in critically ill children. J Pediatr. 2005;146:30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faustino EVS, Bogue CW. Relationship between hypoglycemia and mortality in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:690–8. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e8f502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirshberg E, Larsen G, Van Duker H. Alterations in glucose homeostasis in the pediatric intensive care unit: hyperglycemia and glucose variability are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:361–6. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318172d401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivasan V, Spinella PC, Drott HR, Roth CL, Helfaer MA, Nadkarni V. Association of timing, duration, and intensity of hyperglycemia with intensive care unit mortality in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:329–36. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000128607.68261.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirshberg EL, Sward KA, Faustino EVS, et al. Clinical equipoise regarding glycemic control: a survey of pediatric intensivist perceptions. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:123–9. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31826049b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruttimann UE, Pollack MM. Variability in duration of stay in pediatric intensive care units: a multiinstitutional study. J Pediatr. 1996;128:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slater A, Shann F, Pearson G. PIM2: a revised version of the Paediatric Index of Mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:278–85. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1601-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agus MS, Hirshberg E, Srinivasan V, et al. Design and rationale of Heart and Lung Failure–Pediatric INsulin Titration Trial (HALF-PINT): a randomized clinical trial of tight glycemic control in hyperglycemic critically ill children. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016 Dec 30; doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.12.023. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steil GM, Deiss D, Shih J, Buckingham B, Weinzimer S, Agus MSD. Intensive care unit insulin delivery algorithms: why so many? How to choose? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:125–40. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piper HG, Alexander JL, Shukla A, et al. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring in pediatric patients during and after cardiac surgery. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1176–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaies MG, Langer M, Alexander J, et al. Design and rationale of safe pediatric euglycemia after cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial of tight glycemic control after pediatric cardiac surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:148–56. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31825b549a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steil GM, Langer M, Jaeger K, Alexander J, Gaies M, Agus MS. Value of continuous glucose monitoring for minimizing severe hypoglycemia during tight glycemic control. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:643–8. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31821926a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellomo R, Egi M. What is a NICESUGAR for patients in the intensive care unit? Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:400–2. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60557-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van den Berghe G, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients: NICE-SUGAR or Leuven blood glucose target? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3163–70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bier DM, Leake RD, Haymond MW, et al. Measurement of “true” glucose production rates in infancy and childhood with 6,6-dideuteroglucose. Diabetes. 1977;11:1016–23. doi: 10.2337/diab.26.11.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:125–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arabi YM, Dabbagh OC, Tamim HM, et al. Intensive versus conventional insulin therapy: a randomized controlled trial in medical and surgical critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3190–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f21aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De La Rosa GDC, Donado JH, Restrepo AH, et al. Strict glycaemic control in patients hospitalised in a mixed medical and surgical intensive care unit: a randomised clinical trial. Crit Care. 2008;12:R120. doi: 10.1186/cc7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leteurtre S, Martinot A, Duhamel A, et al. Validation of the Paediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD) score: prospective, observational, multicentre study. Lancet. 2003;362:192–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC/NHSN surveillance definitions for specific types of infections. 2017 Jan; ( http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/17pscnosinfdef_current.pdf)

- 29.Draper E, Fleming T, McKinney P, Parslow R, Thiru K, Willshaw A. National report of the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network: January 2004–December 2006. Universities of Leeds and Leicester; 2007. ( http://www.picanet.org.uk/Audit/Annual-Reporting/Annual-Report-Archive/PICANet_National_Report_2007.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashley A, Draper E, Fleming T, et al. National report of the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network: January 2006–December 2008. Universities of Leeds and Leicester; 2008. ( http://www.picanet.org.uk/Audit/Annual-Reporting/Annual-Report-Archive/PICANet_National_Report_2009.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an updated Pediatric Risk of Mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:743–52. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gennari FJ. Hypokalemia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:451–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808133390707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaies MG, Gurney JG, Yen AH, et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:234–8. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b806fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobi J, Bircher N, Krinsley J, et al. Guidelines for the use of an insulin infusion for the management of hyperglycemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3251–76. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182653269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, Di-Nardo M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1119–31. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qaseem A, Chou R, Humphrey LL, Shekelle P. Inpatient glycemic control: best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29:95–8. doi: 10.1177/1062860613489339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marik PE, Preiser JC. Toward understanding tight glycemic control in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2010;137:544–51. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fivez T, Kerklaan D, Mesotten D, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill children. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1111–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.