Abstract

Many molecular epidemiologic studies have explored the possible links between interleukin-12 (IL-12) polymorphisms and various cancers. However, results from these studies remain inconsistent. This meta-analysis is aimed to shed light on the associations between three common loci (rs568408, rs2243115, rs3212227) of IL-12 gene and overall cancer risk. Our meta-analysis finally included 33 studies comprising 10,587 cancer cases and 12,040 cancer-free controls. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the cancer risk. We observed a significant association between IL-12B rs3212227 and overall cancer risk, especially in hepatocellular carcinoma, nasopharyngeal cancer, and among Asians. IL-12A polymorphisms (rs2243115 and rs568408) were found no influence on overall cancer risk. Nevertheless, stratification analyses demonstrated that rs568408 polymorphism contributed to increasing cancer risk of Caucasians and cervical cancer. And, rs2243115 may enhance the risk of brain tumor. These findings provided evidence that IL-12 polymorphisms may play a potential role in cancer risk.

Keywords: interluekin-12, cancer risk, polymorphism, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

According to the data provided by Cancer statistics, 2017, around 1,688,780 new cancer patients and 600,920 cancer-related deaths will develop in America in 2017 [1]. And, it was estimated that a number of 4,292,000 new cancer patients and 2,814,000 cancer-related deaths would occur in China in 2015 [2]. These data declared that cancer has represented a substantial public health burden. It has been proved that cancer was a multifactorial disease due to dynamic interactions between the environmental exposures and host genetic background. The mechanisms of inherited factors effecting on tumor is still not known clearly, though the carcinogenesis and tumor-immunity function of cytokines have been well established [3]. In fact, one of the pivotal control mechanisms in pathogenesis of tumor was considered to be cytokine-mediated immunity [4]. For instance, interferon, a cytokine with strongly anti-tumor effects, was widely used in treatment of many cancers, especially for hematological malignant tumor such as chronic myeloid leukemia and hairy cell leukemia [5]. Likewise, Interleukins (ILs) were promising in immunotherapy for many cancers because they can enhance the immune response against both infections and tumors. In previous clinical trials several candidates of ILs (such as IL-1a, IL-2, and IL-18) were failed to show corresponding effectiveness on tumors, and other ILs (including IL-7, IL-10, IL-15 and IL-21) showed severe adverse side effects during treatment [6]. Thus, exploration and discovery new, effective immune-modulators are imperative. Interleukin-12 (IL-12), which is characteristic as a link between the innate and acquired immune response [7], is one of the most potential candidates for tumor immunotherapy.

IL-12 is mainly produced by activated antigen-presenting cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and monocytes. As a heterodimeric cytokine, IL-12 protein is formed by two disulfide-linked polypeptide chains comprising p35 and p40, which are encoded by IL-12A gene and IL-12B gene, independently. And it mapped to human chromosomes 3p12-q13.2 and 5q31-33 [8]. IL-12 can potently induce the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cell to Th1 cells and augment cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses, as well as promote activation of natural killer (NK) cells, and secretion of interferon-γ [9]. Moreover, IL-12 can impair the mechanism of neoangiogenesis in tumors by antagonizing the pro-angiogenic signals. Animal experiments extensively showed that both nonspecific and specific antitumor immune responses were enhanced after transfecting IL-12 gene into tumor cells [10, 11]. In addition, clinical trials indicated that serum level of IL-12 was related to the severity of gastric cancer patients [12], and also influenced the progression of colorectal cancer [13].

Because of these pleiotropic activities of IL-12, dozens of molecular epidemiologic studies have explored the influences of IL-12 polymorphisms on susceptibility of various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma [14–19], colorectal cancer [13, 20, 21] and gastric cancer [22–24], etc. The most commonly fascinating loci were rs3212227 in IL-12B gene, rs568408 and rs2243115 in IL-12A genes, perhaps owing to their function to influence IL-12 gene expression, reduce protein synthesis, and subsequently result in cancer. Unfortunately, the functional role on cancer risk that IL-12 gene polymorphisms played was still uncertain. For instance, a study performed by Sun et al. found that IL-12A rs568408 may increase the susceptibility on colorectal cancer [20], being contrary to the conclusion of the study by Huang et al. which suggested IL-12A rs568408 was not associated with colorectal cancer[21]. And, a previous study reported that the loci of rs3212227 in IL-12B gene definitely contributed to increasing cervical cancer risk in Chinese population [25]. However, another study found IL-12B rs3212227 polymorphism exhibited a protective effect [26], while an earlier study showed that there was no relationship between cervical cancer and IL-12B rs3212227 in Korean population [27]. Hence, we conducted this study according to currently published data to investigate the precise relationship between these three common variants and various cancers risk.

RESULTS

Characteristics of eligible studies

As the flow diagram showed Figure 1, we identified a total of 72 publications from the PubMed, web of knowledge, Embase, WanFang, VIP and CNKI databases using the search words, fifteen obviously irrelevant studies and six reviews were excluded firstly. Fourteen studies were excluded from our meta-analysis after screening the titles and abstracts because they were not researching on rs568408, rs2243115 and rs3212227 polymorphisms (2 studies) or cancer (4 studies), and 8 studies were excluded for not case-control studies. The remaining 37 studies evaluated for eligibility by reading the full-text; 3 studies were excluded owing to either lack of complete data or presence of irrelevant data that focused on other IL-12 polymorphisms; one study was written neither in English nor in Chinese. Ultimately, 33 studies with 10,587 cancer cases and 12,040 cancer-free controls were elected in this meta-analysis to explored the relationship of IL-12A rs568408 (10 studies), IL-12A rs2243115 (9 studies), and IL-12B rs3212227 (30 studies) polymorphisms and cancer risk. According to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), all included studies obtained a score of 6 or more, which was defined as a high quality. Among these, 3 studies were written in Chinese and 30 studies in English. The genotype frequencies in 2 studies [17, 18] were not provided completely, we could only evaluated the data based on dominant model. The eligible studies involved several different cancer types including hepatocellular, colorectal, gastric, cervical, breast, prostate, osteosarcoma, esophageal, brain, cervical, ovarian, nasopharyngeal, lung, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cutaneous malignant melanoma. Every study was in according with HWE except for two [20, 28]. The main characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. The distributions of rs568408, rs2243115, and rs3212227 polymorphisms of IL-12 among cases and controls are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. The flow diagram of the meta-analysis, according to the PRISMA 2009.

CNKI: China National Knowledge Infrastructure.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Year | Country | Ethnic | Method | Source of control | Cancer type | Case/control | SNP. | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tan[14] | 2015 | China | Asian | iMLDR | Population | HCC | 395/686 | 1,2,3 | 7 |

| Sun[20] | 2015 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Hospital | CRC | 257/236 | 1,2,3 | 7 |

| Yin[22] | 2015 | China | Asian | SNPscan | Hospital | GAC | 234/476 | 2,3 | 7 |

| Jafarzadeh[35] | 2015 | Iran | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Population | BC | 100/100 | 3 | 6 |

| Winchester[36] | 2015 | USA | Caucasian | MassArray | Population | PC | 566/530 | 3 | 9 |

| Saxena[15] | 2014 | India | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Population | HCC | 59/153 | 3 | 6 |

| wang[37] | 2013 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Population | OSC | 106/210 | 1,2,3 | 7 |

| Sun[38] | 2013 | China | Asian | SNPscan | Hospital | EC | 380/380 | 3 | 8 |

| Jaiswal[39] | 2013 | Indian | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Hospital | BLC | 200/200 | 3 | 6 |

| Tao[40] | 2012 | Mixed | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Population | EC | 426/432 | 1,3 | 6 |

| Sima[41] | 2012 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Hospital | BT | 170/222 | 2,3 | 7 |

| Kaarvatn[42] | 2012 | Croatia | Caucasian | TaqMan | Mixed | BC | 191/194 | 3 | 6 |

| Carvalho[26] | 2012 | Brazil | Mixed | PCR-RFLP | Population | CC | 162/76 | 3 | 6 |

| Roszak[25] | 2012 | Poland | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | Population | CC | 405/405 | 1,3 | 7 |

| Hu[43] | 2012 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Hospital | OC | 92/38 | 3 | 6 |

| Huang[21] | 2012 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Hospital | CRC | 410/450 | 3 | 6 |

| Liu[16] | 2011 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | population | HCC | 869/891 | 1,2,3 | 9 |

| Chaaben[44] | 2011 | Tunisia | African | Taqman | population | NPC | 247/284 | 3 | 6 |

| Ter-Minassian[45] | 2011 | USA | Caucasian | MassArray | Population | BT | 261/319 | 2 | 8 |

| Yang[19] | 2011 | China | Asian | Taqman | Hospital | HCC | 608/612 | 3 | 6 |

| Wu[24] | 2009 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | Population | GC | 1035/1073 | 3 | 7 |

| Chen[46] | 2009 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | population | CC | 404/404 | 1,2,3 | 9 |

| Miteva[13] | 2009 | Bulgaria | Caucasian | PCR–RFLP | Hospital | CRC | 85/134 | 3 | 6 |

| Wei[47] | 2009 | China | Asian | PCR–RFLP | Hospital | NPC | 302/310 | 3 | 6 |

| Zhao[48] | 2009 | China | Asian | PCR–RFLP | Hospital | BT | 210/220 | 3 | 6 |

| Ognjanovic[17] | 2009 | USA | Caucasian | Taqman | population | HCC | 117/223 | 3 | 9 |

| Han[27] | 2008 | Korea | Asian | PCR–RFLP | Hospital | CC | 150/179 | 3 | 7 |

| Hou[23] | 2007 | USA | Caucasian | TaqMan | Population | GC | 257/428 | 1 | 6 |

| Lee[49] | 2007 | USA | Asian | TaqMan | Population | LC | 119/113 | 1 | 8 |

| Wang[50] | 2006 | USA | Caucasian | TaqMan | Population | NHL | 1130/941 | 1,3 | 9 |

| Nieters[18] | 2005 | China | Asian | PCR–RFLP | Hospital | HCC | 250/250 | 3 | 8 |

| Howell[51] | 2003 | UK | Caucasian | ARMS-PCR | Hospital | CMM | 145/229 | 3 | 7 |

PCR: polymerase chain reaction; RFLP: restriction fragment length polymorphism; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; GC: gastric cancer; CRC: colorectal cancer; BC: breast cancer; PC: prostate cancer; OSC: osteosarcoma; EC: esophageal cancer; BLC: bladder cancer; BT: brain tumor; CC: cervical cancer; OC: ovarian carcinoma; NPC: nasopharyngeal cancer; GC: gastric cancer; LC: lung cancer; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CMM: cutaneous malignant melanoma. SNP No.1: rs568408 (3′ UTR G>A) in IL-12A; 2: rs2243115 (5′UTR T>G) in IL-12A; 3: rs3212227 (3′ UTR A>C) in IL-12B; NOS: the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Table 2. Genotype distribution and allele frequency of IL-12 polymorphisms.

| First author | Genotype (N) | Allele frequency (N) | MAF | HWE | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | |||||||||||

| Total | AA | AB | BB | Total | AA | AB | BB | A | B | A | B | |||

| rs568408 | ||||||||||||||

| Tan 2015[14] | 395 | 313 | 76 | 6 | 686 | 511 | 161 | 14 | 702 | 80 | 1183 | 189 | 0.102 | 0.750 |

| Sun 2015[20] | 257 | 172 | 83 | 2 | 236 | 181 | 55 | 0 | 427 | 89 | 417 | 55 | 0.172 | 0.040 |

| Wang2013[37] | 106 | 66 | 37 | 3 | 210 | 156 | 47 | 7 | 169 | 61 | 359 | 61 | 0.265 | 0.150 |

| Tao 2012[40] | 430 | 276 | 142 | 12 | 432 | 304 | 112 | 16 | 694 | 184 | 720 | 144 | 0.210 | 0.170 |

| Roszak 2012[25] | 405 | 253 | 128 | 24 | 450 | 306 | 125 | 19 | 634 | 140 | 737 | 163 | 0.181 | 0.180 |

| Liu 2011[16] | 802 | 504 | 277 | 21 | 861 | 631 | 220 | 10 | 1285 | 289 | 1482 | 240 | 0.184 | 0.060 |

| Chen 2009[46] | 404 | 253 | 145 | 6 | 404 | 285 | 112 | 7 | 651 | 221 | 682 | 126 | 0.253 | 0.290 |

| Hou 2007[23] | 257 | 211 | 8 | 38 | 428 | 306 | 112 | 10 | 430 | 8 | 724 | 132 | 0.018 | 0.950 |

| Lee 2007[49] | 118 | 101 | 17 | 0 | 113 | 81 | 31 | 1 | 219 | 81 | 193 | 33 | 0.270 | 0.290 |

| Wang 2006[50] | 941 | 671 | 238 | 32 | 1130 | 839 | 270 | 21 | 1580 | 238 | 1948 | 312 | 0.131 | 0.890 |

| rs2243115 | ||||||||||||||

| Tan 2015[14] | 395 | 326 | 63 | 6 | 685 | 549 | 128 | 8 | 715 | 75 | 1226 | 144 | 0.095 | 0.861 |

| Sun 2015[20] | 257 | 225 | 31 | 1 | 236 | 212 | 24 | 0 | 481 | 33 | 448 | 24 | 0.064 | 0.411 |

| Yin 2015[22] | 235 | 197 | 36 | 2 | 466 | 387 | 75 | 4 | 430 | 40 | 849 | 83 | 0.085 | 0.862 |

| Wang2013[37] | 106 | 89 | 16 | 1 | 210 | 175 | 31 | 4 | 194 | 18 | 381 | 39 | 0.085 | 0.073 |

| Sun 2013[38] | 368 | 311 | 56 | 1 | 370 | 308 | 58 | 4 | 678 | 58 | 674 | 66 | 0.079 | 0.499 |

| Sima 2012[41] | 170 | 140 | 25 | 5 | 222 | 198 | 24 | 0 | 305 | 35 | 420 | 24 | 0.103 | 0.395 |

| Liu 2011[16] | 861 | 735 | 125 | 1 | 874 | 732 | 137 | 5 | 1595 | 127 | 1601 | 147 | 0.074 | 0.604 |

| Ter-Minassian 2011[45] | 248 | 115 | 113 | 20 | 317 | 180 | 114 | 23 | 343 | 153 | 474 | 160 | 0.308 | 0.403 |

| Chen 2009[46] | 404 | 342 | 60 | 2 | 404 | 337 | 64 | 3 | 744 | 64 | 738 | 70 | 0.079 | 0.984 |

| rs3212227 | ||||||||||||||

| Tan 2015[14] | 395 | 104 | 201 | 90 | 686 | 200 | 347 | 139 | 409 | 381 | 747 | 625 | 0.482 | 0.605 |

| Sun 2015[20] | 257 | 69 | 140 | 48 | 236 | 71 | 124 | 41 | 278 | 236 | 266 | 206 | 0.459 | 0.295 |

| Yin 2015[22] | 234 | 60 | 132 | 42 | 466 | 152 | 221 | 93 | 252 | 216 | 525 | 407 | 0.462 | 0.436 |

| Jafarzadeh 2015[35] | 100 | 58 | 32 | 10 | 100 | 59 | 33 | 8 | 148 | 52 | 151 | 49 | 0.260 | 0.280 |

| Winchester 2015[36] | 866 | 535 | 274 | 57 | 830 | 568 | 227 | 35 | 1344 | 388 | 1363 | 297 | 0.224 | 0.046 |

| Saxena 2014[15] | 59 | 19 | 31 | 9 | 148 | 63 | 71 | 14 | 69 | 49 | 197 | 99 | 0.415 | 0.345 |

| Wang 2013[37] | 106 | 27 | 50 | 29 | 210 | 78 | 101 | 31 | 104 | 108 | 257 | 163 | 0.509 | 0.585 |

| Sun 2013[38] | 368 | 116 | 176 | 76 | 370 | 112 | 179 | 79 | 408 | 328 | 403 | 337 | 0.446 | 0.635 |

| Jaiswal 2013[39] | 200 | 87 | 94 | 19 | 200 | 111 | 74 | 15 | 268 | 132 | 296 | 104 | 0.330 | 0.590 |

| Tao 2012[40] | 426 | 109 | 216 | 101 | 432 | 148 | 213 | 71 | 434 | 418 | 509 | 355 | 0.491 | 0.701 |

| Sima 2012[41] | 170 | 66 | 86 | 18 | 222 | 71 | 116 | 35 | 218 | 122 | 258 | 186 | 0.359 | 0.275 |

| Kaarvatn 2012[42] | 191 | 126 | 59 | 6 | 194 | 104 | 73 | 17 | 311 | 71 | 281 | 107 | 0.186 | 0.419 |

| Carvalho 2012[26] | 162 | 100 | 49 | 13 | 76 | 31 | 37 | 8 | 249 | 75 | 99 | 53 | 0.231 | 0.531 |

| Roszak 2012[25] | 405 | 212 | 174 | 19 | 450 | 289 | 151 | 10 | 598 | 212 | 729 | 171 | 0.262 | 0.056 |

| Hu 2012[43] | 92 | 16 | 42 | 34 | 38 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 74 | 110 | 42 | 34 | 0.598 | 0.360 |

| Huang 2012[21] | 410 | 93 | 219 | 98 | 450 | 124 | 230 | 96 | 405 | 415 | 478 | 422 | 0.506 | 0.578 |

| Liu 2011[16] | 831 | 249 | 422 | 160 | 844 | 272 | 414 | 158 | 920 | 742 | 958 | 730 | 0.446 | 0.983 |

| Chaaben 2011[44] | 247 | 74 | 124 | 49 | 284 | 135 | 118 | 31 | 272 | 222 | 388 | 180 | 0.449 | 0.497 |

| Yang2011[19] | 608 | 156 | 309 | 143 | 612 | 195 | 302 | 115 | 621 | 595 | 692 | 532 | 0.489 | 0.919 |

| Wu 2009[24] | 1035 | 347 | 508 | 180 | 1073 | 333 | 554 | 186 | 1202 | 868 | 1220 | 926 | 0.419 | 0.086 |

| Chen 2009[46] | 404 | 127 | 199 | 78 | 404 | 150 | 185 | 69 | 453 | 355 | 485 | 323 | 0.439 | 0.357 |

| Miteva 2009[13] | 85 | 50 | 31 | 4 | 134 | 80 | 45 | 9 | 131 | 39 | 205 | 63 | 0.229 | 0.443 |

| Wei 2009[47] | 302 | 58 | 165 | 79 | 310 | 98 | 152 | 60 | 281 | 323 | 348 | 272 | 0.535 | 0.938 |

| Zhao 2009[48] | 210 | 38 | 115 | 57 | 220 | 70 | 106 | 44 | 191 | 229 | 246 | 194 | 0.545 | 0.736 |

| Ognjanovic 2009[17] | 117 | 57 | / | / | 223 | 128 | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Tamandani 2009[28] | 200 | 63 | 134 | 3 | 200 | 88 | 104 | 8 | 260 | 140 | 280 | 120 | 0.350 | 0.001 |

| Han 2008[27] | 150 | 32 | 87 | 31 | 179 | 52 | 88 | 39 | 151 | 149 | 192 | 166 | 0.497 | 0.877 |

| Wang 2006[50] | 926 | 565 | 310 | 51 | 1110 | 641 | 397 | 72 | 1440 | 412 | 1679 | 541 | 0.222 | 0.322 |

| Nieters 2005[18] | 249 | 56 | / | / | 250 | 72 | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Howell2003[51] | 145 | 95 | 42 | 8 | 229 | 139 | 77 | 13 | 232 | 58 | 355 | 103 | 0.200 | 0.591 |

A: the major allele, B: the minor allele, MAF: minor allele frequencies; HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Quantitative synthesis of rs568408 and rs2243115 polymorphisms

In the meta-analysis, we derived data from 10 studies including 4115 cancer cases and 4950 cancer-free controls for rs568408, 9 studies containing 3004 cancer cases and 3784 cancer-free controls for rs2243115, respectively.

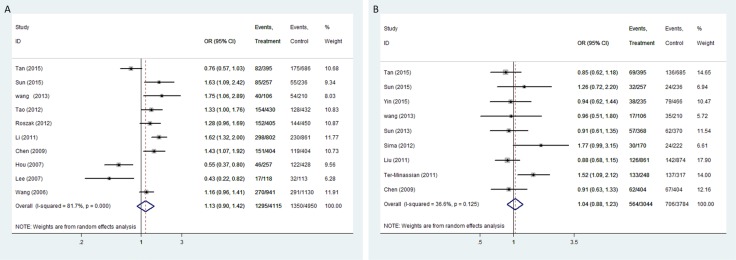

The pooled analysis proved that IL-12A rs568408 polymorphisms was associated with overall cancer risk on allele comparison (A vs. G: OR = 1.18, 95%CI: 1.01-1.38, P = 0.04). However, no significant association was found after excluding one study [20] not according to the HWE (All P > 0.05, Figure 2). In stratified analysis by ethnicity, we observed an increased risk of overall cancers among Caucasians (recessive model: OR = 2.63, 95% CI = 1.05-6.56; homozygote model: OR = 2.46, 5% CI = 1.20-5.06; allele model: OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.05-1.35). The subgroup analysis by cancer type showed rs568408 polymorphism increased cervical cancer risk under three genetic models (allele model: OR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.07-1.52; heterozygous model: OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.09-1.66; dominate model: OR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.10-1.65). Rs2243115 polymorphism was associated with brain tumor under dominate model (OR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.18-2.11), heterozygous model (OR = 1.53, 95 % CI = 1.13-2.07) and allele model (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.03-2.24). However, the subgroup analysis based on source of controls proved IL-12A polymorphisms (rs568408 and rs2243115) have no influence on cancer susceptibility in both hospital-based and population-based controls subgroups (all P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of OR with 95%CI for the IL-12 polymorphisms with cancer risk under dominant model (A) rs568408; (B) rs2243115). CI: confidence interval, OR: odds ratio.

Quantitative synthesis of rs3212227 polymorphism

We gained 9950 patients and 11180 control subjects from 30 studies of rs3212227 polymorphism. IL-12B rs3212227 was proved to enhance overall cancer risk (C vs. A: OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.05-1.25; CC vs. AA: OR = 1.32, 95%CI: 1.11-1.56; AC vs. AA: OR= 1.21, 95%CI: 1.08-1.35, P = 0.001; AC+CC vs. AA: OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.10-1.40, P < 0.001; CC vs. AC+AA: OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.04-1.31). The similar results were obtained after excluding studies with HWE disequilibrium (C vs. A: OR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.05-1.25; CC vs. AA: OR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.12-1.58; AC vs. AA: OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 1.06-1.34; AC+CC vs. AA: OR = 1.23, 95%CI: 1.09-1.38; CC vs. AC+AA: OR = 1.18, 95%CI: 1.05-1.32).

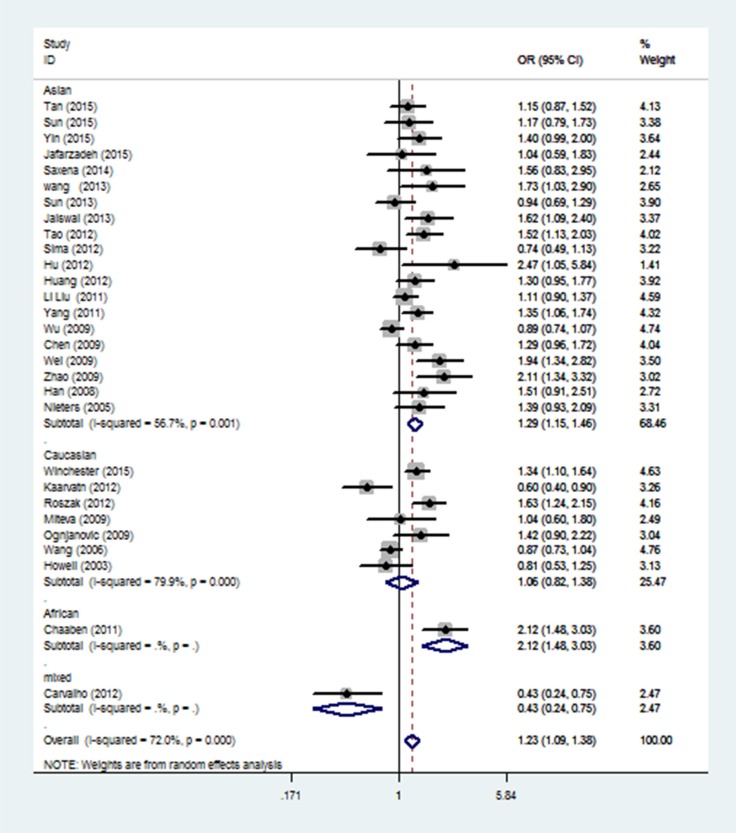

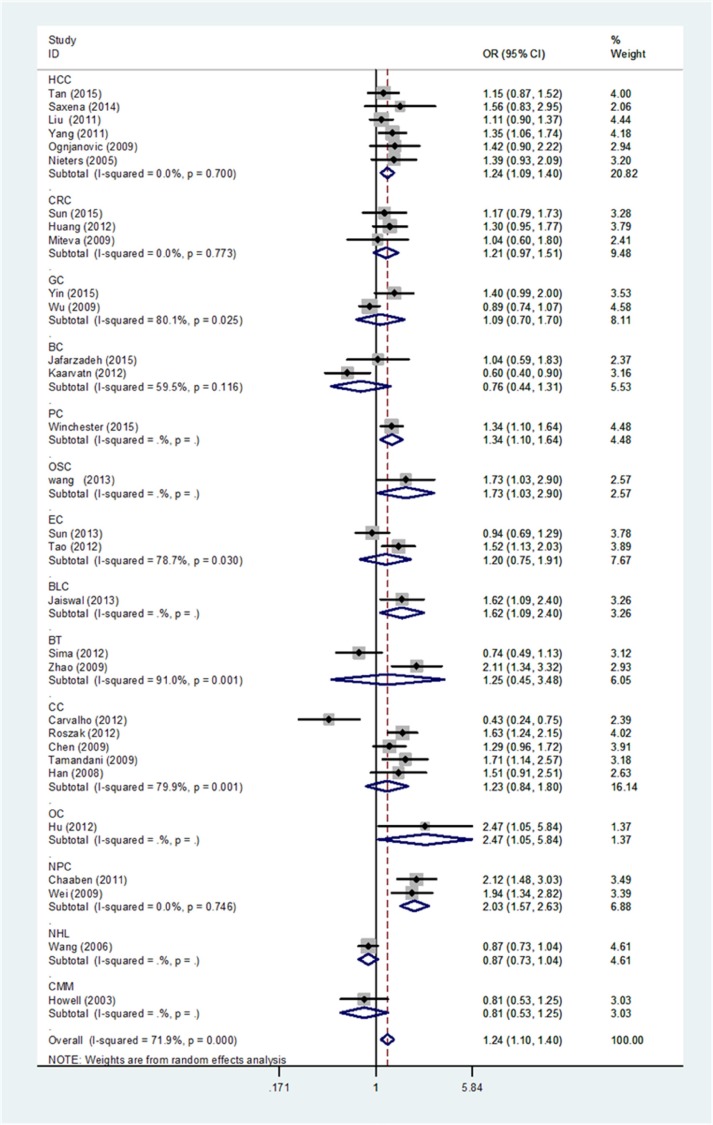

When stratification analysis performed by ethnicity (Figure 3), rs3212227 polymorphism exhibited to increase overall cancer risk among Asians (AC+CC vs. AA: OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.15-1.46; CC vs. AC+AA: OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.06-1.30; CC vs. AA: OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.17-1.62; AC vs. AA: OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 1.11-1.40; C vs. A: OR = 1.18, 95%CI: 1.09-1.28). In subgroup analysis by cancer type (Figure 4), rs3212227 was found to increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (AC+CC vs. AA: OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.09-1.40; CC vs. AC+AA: OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.00-1.37; CC vs. AA: OR = 1.30, 95%CI: 1.07-1.59; AC vs. AA: OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 1.02-1.35; C vs. A: OR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.04-1.25) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (AC+CC vs. AA: OR = 2.03, 95%CI: 1.57-2.63; CC vs. AC+AA: OR = 1.66, 95%CI: 1.23-2.25; CC vs. AA: OR = 2.49, 95%CI: 1.75-3.54; AC vs. AA: OR = 1.88, 95%CI: 1.43-2.47; C vs. A: OR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.34-1.90). When conducted a stratified analysis by the source of controls, rs3212227 polymorphism displayed an increased cancer risk among population-based studies and hospital-based studies in different comparison models. The detail results were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 3. Stratified analysis by ethnicity for the association between IL-12 rs3212227 polymorphism and cancer risk under dominant model (CC + AC vs. AA) according to the HWE.

CI: confidence interval, OR: odds ratio, HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Figure 4. Stratified analysis by cancer type for the association between IL-12B rs3212227 polymorphism and cancer risk under dominant model (CC + AC vs. AA) according to the HWE.

CI: confidence interval, OR: odds ratio. HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; GC: gastric cancer; CRC: colorectal cancer; BC: breast cancer; PC: prostate cancer; OSC: osteosarcoma; EC: esophageal cancer; BLC: bladder cancer; BT: brain tumor; CC: cervical cancer; OC: ovarian carcinoma; NPC: nasopharyngeal cancer; GC: gastric cancer; LC: lung cancer; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CMM: cutaneous malignant melanoma, HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

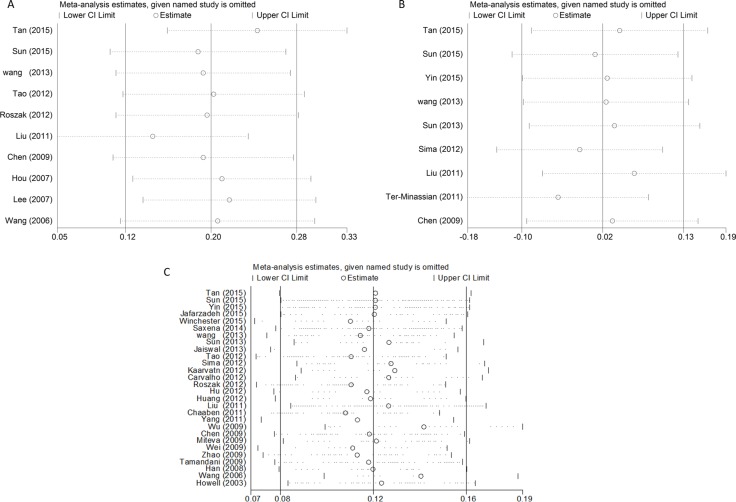

For the overall study, statistically significant heterogeneity existed in rs568408 polymorphism (AA+GA vs. GG, P < 0.0001, I2 = 82%; AA vs. GA+GG, P = 0.001, I2 = 68%; AA vs. GG, P = 0.009, I2 = 59%; GA vs. GG, P < 0.0001, I2 = 88%; A vs. G, P < 0.0001, I2 = 70%) and rs3212227 polymorphism (AC+CC vs. AA, P < 0.0001, I2 = 72%; CC vs. AA, P < 0.0001, I2 = 65%; AC vs. AA, P < 0.0001, I2 = 66%; C vs. A, P < 0.0001, I2 = 74%). Therefore, we conducted further subgroup analyses by cancer type, ethnicity and source of control (Supplementary Table 1). The sequential leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was adopted to evaluate each individual study's influence on the overall risk estimates. However, the results proved there was no single study could skew the pooled ORs significantly, indicating the credibility and reliability of this meta-analysis (shown in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of the associations between IL12 polymorphisms and cancer risk (A) rs568408; (B) rs2243115; (C) rs3212227).

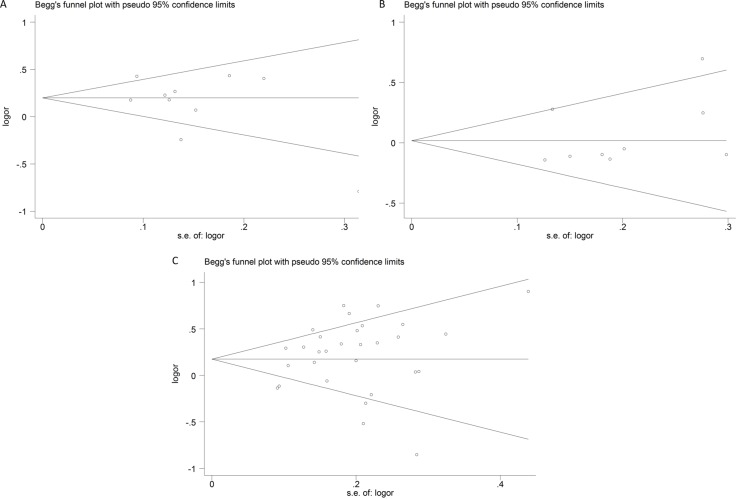

Publication bias

Publication bias of the eligible studies of these IL-12 polymorphisms was accessed by funnel plot and Egger's test. The symmetrical shapes of the funnel plots (Figure 6) and further statistical evidence provided by Egger's test (Table 3) showed the absence of publication bias (P > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Funnel plots of publication bias (A) rs568408; (B) rs2243115; (C) rs3212227).

Table 3. Egger's test for publication bias test of IL-12 polymorphisms.

| Egger’s test | Coefficient | SE | t | P > |t| | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs568408 | slope | 0.552139 | 0.228511 | 2.42 | 0.046 | 0.0117964–1.092481 |

| bias | −3.03665 | 1.803099 | −1.68 | 0.136 | −7.300299–1.227003 | |

| rs2243115 | slope | −0.20484 | 0.284498 | −0.72 | 0.495 | −0.877572–0.467887 |

| bias | 1.303655 | 1.599617 | 0.81 | 0.442 | −2.837692–6.454866 | |

| rs3212227 | slope | −0.0187827 | 0.1555829 | −0.12 | 0.905 | −3380125–0.300447 |

| bias | 1.225427 | 0.9578139 | 1.28 | 0.212 | −7398447–3.190699 |

SE: standard error; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Attracted to the effects of IL-12 polymorphisms in the onset risk of cancer, many researchers performed numerous molecular epidemiological studies to explore the connection. Regrettably, they were failed to achieve a coincident conclusion. Existing epidemiological studies showed a higher interest on the SNP of rs3212227 in IL-12B gene, but put less focus on the rs568408 and rs2243115 SNPs of IL-12A genes. Only one meta-analysis (including eighteen studies) focused on IL-12A polymorphisms and suggested that both rs568408 and rs2243115 polymorphisms of IL-12A did not connect with cancer susceptibility [29]. In our meta-analysis, we observed that rs568408 polymorphism increased cervical cancer risk and overall cancer risk among Caucasians, while rs2243115 polymorphism may be a high risk factor of brain tumor. And, the mutant C allele of rs3212227 polymorphism was proved to contribute to overall cancer's development, especially for hepatocellular carcinoma, nasopharyngeal cancer and among Asians.

What we found in this meta-analysis is contrary to the previous meta-analyses [29, 30], our study proved no association between cervical cancer and rs3212227 polymorphism, while rs568408 and rs2243115 polymorphisms were associated with cervical cancer and brain tumor respectively. Compared to the previous meta-analyses, this study included more eligible studies, conducted more detailed subgroup analyses, and also performed stringent quality control during data statistics. Thus, our results are more comprehensive and persuasive. In the past years, we considered only IL-12B polymorphism played an important role in cancer development and looked down on the function of IL-12A. This meta-analysis indicated that we should perform more comprehensive investigation both on the respective function and interaction of IL-12A and IL-12B.

As is depicted in introduction, IL-12 is a multiple effective cytokine that links the innate (NK cells) and acquirs (cytotoxic T lymphocytes) immune response [7]. Structurally, IL-12 is a heterodimer consisted of a 35 kD α-chain (p35 subunit) and a 40 kD β-chain (p40 subunit), the latter was shared with IL-23, another important member from IL-12 family. P35 and p40 are encoded by IL-12 A and IL-12 B gene, respectively. And, IL-12 p40 is produced in excess over the IL-12 and IL-23 heterodimers in average level [31]. We guess the amount of activated IL-12B gene was much more than activated IL-12A gene, thus we observed more mutation frequency in IL-12B rs3212227. In fact, both IL-12A and IL-12B gene have played a role in the development of cancer. Therefore, we speculated IL-12 polymorphisms may alter the IL-12 gene expression, decrease functional IL-12 protein synthesis, which ultimately brought about immune system dysfunction and lead to the development of malignant tumors. The clinical trials of IL-12 were rather disappointing, because systemic administration in cancer treatment was observed defined anti-tumor efficacy and severe toxic effects. Thus, it was now vigorously promoted to develop the gene therapy vectors which can express activated IL-12 locally in tumors. New avenues for IL-12 in cancer have been opened with technical advances in recent years, which are currently under research [32]. Our meta-analysis provided a direction to the further vivo and in vitro experiments.

Some possible limitations in this study need to be attended. Firstly, some potential source of heterogeneity, such as sex and environmental exposures, may have influence on the final results of the present study. Secondly, environmental factors were failed to evaluate, because lack of relevant data, such as family history, age, lifestyle, which might alter the real relation of IL-12 polymorphisms and the cancer risk. Thirdly, studies written in a third language were excluded (not in English or Chinese), thus, selection bias is inevitable. Fourthly, although we pooled all eligible publications together in our study, the sample size for some types of cancer were still small. For instance, there was only one or two literature available for cervical cancer. Thus, we should be cautious to explain our results. Finally, publication bias may exist in our meta-analysis because we could not gain the unpublished data.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis draws a reliable conclusion that these IL-12 polymorphisms (rs568408, rs2243115 and rs3212227) might be high risk factors for cancer, which indicated IL-12 may serve as a promising marker for cancer screening. Further well-designed multi-center studies with larger sample sizes (especially for rs568408 and rs2243115 polymorphisms of IL-12A) and detailed gene-environmental interactions are warranted to confirm our findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We followed the PRISMA statement to guide the process of this meta-analysis [33]

Search strategy

We obtained eligible studies prior to October 2016 from the PubMed, web of knowledge, Embase, WanFang, VIP and CNKI databases, using the terms: “cancer or carcinoma or tumor or neoplasm” and “polymorphism or variant or variation” and “interleukin-12 or IL-12”. In addition, we manually screened the references in the relevant reviews to ensure all relevant studies were not missed. Studies elected in this meta-analysis met the criteria as follows: (1) case-control studies evaluated the association of IL-12A rs568408, IL-12A rs2243115, or IL-12B rs3212227 polymorphisms with various cancer risks; (2) genotype distributions were sufficient for both cases and controls for data extraction; (3) published in English or Chinese. And we adopted following exclusion criteria: (1) repeat of previous studies, reviews, or abstracts; (2) not case-control design; (3) absence of detailed genotyping data; (4) duplication of previous data. If the overlap of data appeared in different publications, the paper included more samples were chosen.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators independently elected for following information from the all eligible studies: first author, publication year, cancer type, country, ethnicity, source of controls, genotyping platform, total number of cases and controls, genetic distribution among cases and controls, and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P value of controls. The subgroup analyses were performed according to cancer type, ethnicity (Asians, Caucasians), and source of controls. All patients in case group were confirmed by histology or pathology. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of the eligible studies [34], The total scores ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating better quality. Score of 0–5, 6-9 was considered as indicative of a low-, high-quality study, respectively. To resolve all disagreements of two investigators, a discussion with a senior investigator was conducted until a consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the cancer risk associated IL-12 polymorphisms (rs568408, rs2243115, rs3212227), we calculated ORs and 95% CI based on the genotypes in cases and controls. Five different genetic models were evaluated: (i) BB+ AB vs. AA (dominant model), (ii) BB vs. AA (homozygote model), (iii) AB vs. AA (heterozygote model), (iv) BB vs. AA+ AB (recessive model), (v) B vs. A (allele comparison). “A” represents the wild allele, while “B” represents the mutation allele. Heterogeneity among the studies was checked by Chi-square-based Q statistic and I2 test, and it was regarded as homogeneous if P > 0.10 in Chi-square-based Q statistic. When the effects were assumed to be homogeneous, we used the fixed-effects model to assess the pooled OR. Otherwise, the random-effects model was chosen. Furthermore, source of heterogeneity among studies was explored by subgroup analyses base on cancer type, ethnicity and source of control. We adopted Begg's and Egger's test to evaluate the possible sources of bias. Sensitivity analysis was chiefly performed by orderly removing individual study and rechecked the pooled ORs to assess the stability of the final results. All statistical analyses in this study were performed by software STATA (Version 14.0; Stata Corp, College Station, TX). A statistical significance was considered if P < 0.05 and all the statistics were two-sided.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES AND TABLES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (16BGL183), the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (2015JM8415) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (2011jdhz55).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smyth MJ, Cretney E, Kershaw MH, Hayakawa Y. Cytokines in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:275–93. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein D, Laszlo J. The role of interferon in cancer therapy: a current perspective. CA Cancer J Clin. 1988;38:258–77. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.38.5.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuzhalin AE, Kutikhin AG. Interleukin-12: clinical usage and molecular markers of cancer susceptibility. Growth Factors. 2012;30:176–91. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.678843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasek W, Zagożdżon R, Jakobisiak M. Interleukin 12: still a promising candidate for tumor immunotherapy? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:419–35. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1523-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–46. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Vecchio M, Bajetta E, Canova S, Lotze MT, Wesa A, Parmiani G, Anichini A. Interleukin-12: biological properties and clinical application. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4677–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He J, Gu D, Wu X, Reynolds K, Duan X, Yao C, Wang J, Chen CS, Chen J, Wildman RP, Klag MJ, Whelton PK. Major causes of death among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1124–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He XZ, Wang L, Zhang YY. An effective vaccine against colon cancer in mice: use of recombinant adenovirus interleukin-12 transduced dendritic cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:532–40. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakami S, Okubo K, Tsuji Y, Sakata H, Hamada S, Hirayama R. Serum interleukin-12 levels in patients with gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2004;34:1014–19. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2860-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miteva L, Stanilov N, Deliysky T, Mintchev N, Stanilova S. Association of polymorphisms in regulatory regions of interleukin-12p40 gene and cytokine serum level with colorectal cancer. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:924–31. doi: 10.3109/07357900902918486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan A, Gao Y, Yao Z, Su S, Jiang Y, Xie Y, Xian X, Mo Z. Genetic variants in IL12 influence both hepatitis B virus clearance and HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma development in a Chinese male population. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:6343–8. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4520-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxena R, Chawla YK, Verma I, Kaur J. Effect of IL-12B, IL-2, TGF-β1, and IL-4 polymorphism and expression on hepatitis B progression. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34:117–28. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L, Xu Y, Liu Z, Chen J, Zhang Y, Zhu J, Liu J, Liu S, Ji G, Shi H, Shen H, Hu Z. IL12 polymorphisms, HBV infection and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a high-risk Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1692–96. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ognjanovic S, Yuan JM, Chaptman AK, Fan Y, Yu MC. Genetic polymorphisms in the cytokine genes and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in low-risk non-Asians of USA. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:758–62. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nieters A, Yuan JM, Sun CL, Zhang ZQ, Stoehlmacher J, Govindarajan S, Yu MC. Effect of cytokine genotypes on the hepatitis B virus-hepatocellular carcinoma association. Cancer. 2005;103:740–48. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y. Polymorphisms of TGF- β1 and IL- 12B gene and risk of hepatocellular cancer in Guangxi—a case-control study. Chin J Publ Health. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun R, Jia F, Liang Y, Li L, Bai P, Yuan F, Gao L, Zhang L. Interaction analysis of IL-12A and IL-12B polymorphisms with the risk of colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9295–301. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang ZQ, Wang JL, Pan GG, Wei YS. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in IL-12 and IL-27 genes with colorectal cancer risk. Clin Biochem. 2012;45:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin J, Wang X, Wei J, Wang L, Shi Y, Zheng L, Tang W, Ding G, Liu C, Liu R, Chen S, Xu Z, Gu H. Interleukin 12B rs3212227 T > G polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of gastric cardiac adenocarcinoma in a Chinese population. Dis Esophagus. 2015;28:291–8. doi: 10.1111/dote.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou L, El-Omar EM, Chen J, Grillo P, Rabkin CS, Baccarelli A, Yeager M, Chanock SJ, Zatonski W, Sobin LH, Lissowska J, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Chow WH. Polymorphisms in Th1-type cell-mediated response genes and risk of gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:118–23. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Lu Y, Xu GY. Relationship between IL-12B gene polymorphism and susceptibility of gastric cancer. China Cancer. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roszak A, Mostowska A, Sowińska A, Lianeri M, Jagodziński PP. Contribution of IL12A and IL12B polymorphisms to the risk of cervical cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2012;18:997–1002. doi: 10.1007/s12253-012-9532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.do Carmo Vasconcelos de Carvalho V, de Macêdo JL, de Lima CA, da Conceição Gomes de Lima M, de Andrade Heráclio S, Amorim M, de Mascena Diniz Maia M, Porto AL, de Souza PR. IFN-gamma and IL-12B polymorphisms in women with cervical intraepithellial neoplasia caused by human papillomavirus. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:7627–34. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han SS, Cho EY, Lee TS, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Kim JG, Lee HP, Kang SB. Interleukin-12 p40 gene (IL12B) polymorphisms and the risk of cervical cancer in Korean women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;140:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamandani DM, Shekari M, Suri V. Interleukin-12 gene polymorphism and cervical cancer risk. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32:524–28. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318192519a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou L, Yao F, Luan H, Wang Y, Dong X, Zhou W, Wang Q. Functional polymorphisms in the interleukin-12 gene contribute to cancer risk: evidence from a meta-analysis of 18 case-control studies. Gene. 2012;510:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, Cheng S, Wang J, Cao C, Bunjhoo H, Xiong W, Xu Y. Interleukin-12B rs3212227 polymorphism and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:10235–42. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1899-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Andrea A, Rengaraju M, Valiante NM, Chehimi J, Kubin M, Aste M, Chan SH, Kobayashi M, Young D, Nickbarg E. Production of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1387–98. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang S, Wang Q. Factors determining the formation and release of bioactive IL-12: regulatory mechanisms for IL-12p70 synthesis and inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:509–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, Niu Y, Du L. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8:2–10. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jafarzadeh A, Minaee K, Farsinejad AR, Nemati M, Khosravimashizi A, Daneshvar H, Mohammadi MM, Sheikhi A, Ghaderi A. Evaluation of the circulating levels of IL-12 and IL-33 in patients with breast cancer: influences of the tumor stages and cytokine gene polymorphisms. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:1189–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winchester DA, Till C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Santella RM, Johnson-Pais TL, Leach RJ, Xu J, Zheng SL, Thompson IM, Lucia MS, Lippmann SM, Parnes HL, et al. Variation in genes involved in the immune response and prostate cancer risk in the placebo arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Prostate. 2015;75:1403–18. doi: 10.1002/pros.23021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Nong L, Wei Y, Qin S, Zhou Y, Tang Y. Association of interleukin-12 polymorphisms and serum IL-12p40 levels with osteosarcoma risk. DNA Cell Biol. 2013;32:605–10. doi: 10.1089/dna.2013.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun JM, Li Q, Gu HY, Chen YJ, Wei JS, Zhu Q, Chen L. Interleukin 10 rs1800872 T>G polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer in a Chinese population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:3443–47. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.6.3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaiswal PK, Singh V, Srivastava P, Mittal RD. Association of IL-12, IL-18 variants and serum IL-18 with bladder cancer susceptibility in North Indian population. Gene. 2013;519:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao YP, Wang WL, Li SY, Zhang J, Shi QZ, Zhao F, Zhao BS. Associations between polymorphisms in IL-12A, IL-12B, IL-12Rβ1, IL-27 gene and serum levels of IL-12p40, IL-27p28 with esophageal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1891–900. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sima X, Xu J, Li Q, Luo L, Liu J, You C. Gene-gene interactions between interleukin-12A and interleukin-12B with the risk of brain tumor. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31:219–23. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaarvatn MH, Vrbanec J, Kulic A, Knezevic J, Petricevic B, Balen S, Vrbanec D, Dembic Z. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the interleukin 12B gene is associated with risk for breast cancer development. Scand J Immunol. 2012;76:329–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu YZ, Zhang R. Association of IL-12B polymorphism with susceptibility to ovarian carcinoma. J Hunan Normal Univ. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben Chaaben A, Busson M, Douik H, Boukouaci W, Mamoghli T, Chaouch L, Harzallah L, Dorra S, Fortier C, Ghanem A, Charron D, Krishnamoorthy R, Guemira F, et al. Association of IL-12p40 +1188 A/C polymorphism with nasopharyngeal cancer risk and tumor extension. Tissue Antigens. 2011;78:148–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2011.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ter-Minassian M, Wang Z, Asomaning K, Wu MC, Liu CY, Paulus JK, Liu G, Bradbury PA, Zhai R, Su L, Frauenhoffer CS, Hooshmand SM, De Vivo I, et al. Genetic associations with sporadic neuroendocrine tumor risk. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1216–22. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen X, Han S, Wang S, Zhou X, Zhang M, Dong J, Shi X, Qian N, Wang X, Wei Q, Shen H, Hu Z. Interactions of IL-12A and IL-12B polymorphisms on the risk of cervical cancer in Chinese women. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:400–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei YS, Lan Y, Luo B, Lu D, Nong HB. Association of variants in the interleukin-27 and interleukin-12 gene with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:751–57. doi: 10.1002/mc.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao B, Meng LQ, Huang HN, Pan Y, Xu QQ. A novel functional polymorphism, 16974 A/C, in the interleukin-12-3′ untranslated region is associated with risk of glioma. DNA Cell Biol. 2009;28:335–41. doi: 10.1089/dna.2008.0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee KM, Shen M, Chapman RS, Yeager M, Welch R, He X, Zheng T, Hosgood HD, Yang D, Berndt SI, Chanock S, Lan Q. Polymorphisms in immunoregulatory genes, smoky coal exposure and lung cancer risk in Xuan Wei, China. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1437–41. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang SS, Cerhan JR, Hartge P, Davis S, Cozen W, Severson RK, Chatterjee N, Yeager M, Chanock SJ, Rothman N. Common genetic variants in proinflammatory and other immunoregulatory genes and risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9771–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Howell WM, Turner SJ, Theaker JM, Bateman AC. Cytokine gene single nucleotide polymorphisms and susceptibility to and prognosis in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Eur J Immunogenet. 2003;30:409–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2370.2003.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.