Abstract

Human tissues are intricate ensembles of multiple cell types embedded in complex and well-defined structures of the extracellular matrix (ECM). The organization of ECM is frequently hierarchical from nano to macro, with many proteins forming large scale structures with feature sizes up to several hundred microns. Inspired from these natural designs of ECM, nanotopography-guided approaches have been increasingly investigated for the last several decades. Results demonstrate that the nanotopography itself can activate tissue-specific function in vitro as well as promote tissue regeneration in vivo upon transplantation. In this review, we provide an extensive analysis of recent efforts to mimic functional nanostructures in vitro for improved tissue engineering and regeneration of injured and damaged tissues. We first characterize the role of various nanostructures in human tissues with respect to each tissue-specific function. Then, we describe various fabrication methods in terms of patterning principles and material characteristics. Finally, we summarize the applications of nanotopography to various tissues, which are classified into four types depending on their functions: protective, mechano-sensitive, electro-active, and shear stress-sensitive tissues. Some limitations and future challenges are briefly discussed at the end.

Keywords: Nanotopography, Tissue engineering, Regenerative medicine, Biomaterials, Cell–material interface

1. Introduction

Human organs maintain homeostasis, transfer information, generate force, and adapt to changes in the environment. Organs may lose functions over time due to excessive use and inevitable aging, or unexpectedly through disease or other pathologies. Damaged organs can be regenerated with the aid of various drugs, mechanical supports or transplantation. Here, regenerative medicine refers to technology that could be used for reconstructing damaged tissues or organs with various items and techniques including cells, scaffolds, medical devices or gene therapy [1]. Since the introduction of regenerative medicine in 1980s, the field has rapidly grown at an amazing rate, and it is in the transient stage progressing from basic research toward clinical applications [2]. Additionally, costs associated with healthcare are rising dramatically to meet the demands of an ever increasingly older population. For example, in the USA, the expenditure for healthcare reached 17.3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and this percentage is estimated to continue to increase in the future [1]. Furthermore, in research fields, the scientific publications on regenerative medicine, number of submitted and accepted patents, and number of companies working on commercializing regenerative medicine products and therapies are also gradually increasing [2].

In regenerative medicine, therapies generally focus on a specific organ and must meet the heterogeneity and demands of the individual organs. Therefore, regenerative medicine has to start from the understanding of underlying cellular behaviors, tissue specific environment, and cause of tissue degradation and injury. In terms of cellular behavior, for example, cells in various tissues respond differently according to diverse factors such as physical topography or rigidity (durotaxis) [3], gradient of cellular adhesion sites (haptotaxis) [4], electric fields (electrotaxis) [5], and chemical factors (chemotaxis) [6,7]. Importantly, different cells may behave oppositely even under identical stimuli: fibroblasts migrate toward the more rigid region while neurons stretch neurite to the direction of softer site. Furthermore, the environmental effects originate from the organ-specific functions such as protection (skin), mechanical maintenance (bone), transmission of force (ligament and tendons), conduction of electrical signal (neuron), blood circulation (heart and vessels), and force generation (skeletal muscle).

Among the various factors described above, physical cues are of great importance since cells reside in a physical microenvironment with tissue specific topography and rigidity. Such physical structures are widely observed in the human body such as the neuronal network in the brain, aligned myofibrils in the heart and skeletal muscle, and collagen fibers in the skin. Since these structures are intended for tissue specific functions, pathology may change the physical nanostructures in these organs, which results in the malfunction or disconnection of signal or force transfer. For example, it is well known that neurons in the human brain have a radially spreading morphology connecting the cerebral cortex and white matter. In the case of physiological malfunctions such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s diseases, neuronal interconnections are severely damaged, thus losing informational pathways [8]. The goals of regenerative medicine with the aid of nanostructures lie in facilitating guided cell migration and proliferation to restore physiological structures and functions and minimizing possible side effects. To fabricate the observed natural structures with distinct physical properties, various materials and fabrication methods have been used over time.

In this review, we provide an extensive overview on recent efforts for constructing in vivo-like microenvironment with nanofabricated structures and results of cell-specific functions dependent on physical cues. In the first section, the tissue-specific nanostructures will be characterized with respect to their specific functions and physiology such as protective, mechano-sensitive, electro-active and shear stress-sensitive characteristics. In the second section, nanofabrication techniques will be summarized in terms of patterning principles and material characteristics. In the third section, examples of tissue-specific cell functions, tissue-mimicking systems and in vivo implantation results of these systems will be described in conjunction with the physiological similarity of these tissues in their functional roles. We believe that this extensive overview on studies examining the relation of cells to their physical microenvironment will present an in-depth understanding on current regenerative medicine strategies.

2. Microenvironment of human tissues: role of nanotopography

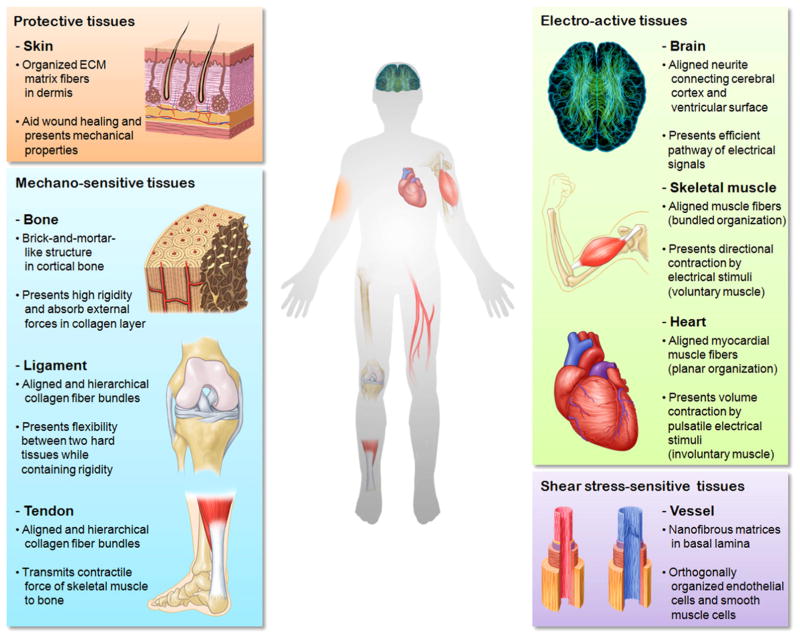

The tissues in the human body contain nanoscale structures which assist tissue-specific functions. As shown in Fig. 1, nanostructures in the human body can be classified depending on their functions and physiological environment into four types, namely protective tissue (skin), mechano-sensitive tissues (bone, ligament/tendon), electro-active tissues (neuron, skeletal muscle, heart) and shear stress-sensitive tissue (blood vessel). Since these tissues are exposed to different stimuli and environments, an understanding of each tissue-specific structure is required.

Fig. 1.

Various nanostructures in the human body. The tissues are classified into four categories, namely protective, mechano-sensitive, electro-active and shear stress-sensitive tissues with respect to the tissue specific environment and functions.

2.1. Protective tissues

The skin protects internal tissues and organs from external irritations such as light, pathogens and chemicals. The skin must thus be sufficiently rigid to withstand physical trauma and act as a physical barrier to the external environment and elastic enough to absorb mechanical impact from outside. For these reasons, the skin has moderate elastic modulus of 7–50 MPa [9,10]. From a structural point of view, the skin is composed of three layers: epidermis, dermis and hypodermis. Among these, well aligned ECM fibers such as collagen, fibronectin and keratin fibers (diameter of few tens of nanometers) are observed in the dermis and are responsible for mechanical support and the regulation of cell functions. These ECM fibers have diameters of 60–120 nm with the length of few micrometers. In the dermis, the diameter of ECM fibers increases as the skin depth increases [11]. Generally, it has been known that the matrix fibers in the unwounded dermis are organized in a basket-weave meshwork [12]. There is also macroscopically directional anisotropy of collagen fibers, which is called Langer’s line [13]. With this alignment of ECM fibers, the skin demonstrates anisotropic mechanical properties [14]. For example, due to the alignment of ECM matrix fibers, skin wound healing following a cesarean section is affected by the incision direction, showing better healing and smaller scar formation in transverse incisions compared to sagittal incisions. The presence of nanotopography and its effects on cell and tissue function has inspired in vitro wound healing studies.

2.2. Mechano-sensitive tissues

Mechano-sensitive tissues refer to those tissues that are continuously exposed to mechanical force while walking or exercising, including bone, ligament and tendon. To endure external forces and support the body’s structure, bone (4.5–20 GPa) [15–17] and ligament/tendon (10 MPa–2 GPa) [9,10,18] have relatively high elastic moduli. Mechano-sensitive tissues also act mechanically as a damper, to absorb or diminish abrupt mechanical changes of the body system. Interestingly, mechano-sensitive tissues have hierarchical structures. As shown in Fig. 1, the bone is composed of two distinct areas: cortical bone (also known as compact bone) which has concentric cylindrical features and cancellous bone (also known as spongy bone) which has a spongy-like structure. Especially, in cortical bone, such high mechanical rigidity originated from brick-and-mortar structures, comprising plate-like mineral crystals stacked within the collagen matrix [19,20]. The mineral platelets (dahllite, also known as carbonated apatite) have average lengths and widths of 50×25 nm2, and thicknesses of 1.5–4 nm [21,22]. The collagen fibers found in bone have a diameter of about 80–100 nm, comprised of triple helixes of collagen molecules with a diameter of ~1.5 nm and a length of ~300 nm which are organized in a staggered way [22,23]. Since the mineral platelets are also stacked in a staggered manner and embedded in a collagen matrix, externally applied stresses can be redistributed and fracture energy can be absorbed or dissipated in daily activities such as walking and running [24]. In contrast, the cancellous bone is less dense, softer, and less stiff, and contains red bone marrow, where hematopoiesis, the production of blood cells, occurs.

Similarly, ligaments and tendons, which are fibrous connective tissues, connecting two tissues together, also contain hierarchical nanostructures for their functions. Ligaments connect bone to bone at joints, with enough flexibility to allow the joint movement while containing sufficient rigidity to prevent dislocation, and are commonly observed in knees and shoulders. Tendons connect skeletal muscle to bone to transfer force for the movement. For ligaments and tendons, it is composed of four levels of hierarchy: collagen molecule, collagen fiber, fascicle, and tendon fiber. The collagen fibers are composed of bundles of collagen molecules in a triple helix (diameter of ~1.3 nm) which are packed in a staggered manner. The bundles of collagen fibers with a diameter of 50–500 nm are embedded in a proteoglycan-rich matrix [24], forming a fascicle (diameter of 50–300 μm). Finally, fascicles form tendon fibers with a diameter of 100–500 μm [25]. Due to multilevel, hierarchical, and staggered organization, ligaments and tendons dissipate abruptly applied mechanical force by slippage between collagen molecules or fibers. These uni-directionally aligned hierarchical nanostructures provide sufficient compliance for dynamic action and mechanical impact by inter-fiber sliding which is aided by deformation of the proteoglycan layer [26,27].

2.3. Electro-active tissues

Unlike the passive structures in mechano-sensitive tissues, electro-active tissues have active structures which respond to electrical stimuli. As can be inferred from the name ‘electro-active’, electro-active tissues respond to pulsatile or abrupt electrical stimuli. Brain tissue is an electro-active tissue in which information and stimulation received from the eyes, ears and skin are processed through the relay of signals by neurons. When these signals are received, the data is transmitted as an electrical pulse which is called action potential. These signals are collected through the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). Here, the CNS includes the retina, brain and spinal cord, and the PNS refers to the rest of the nervous system such as sensory receptors and effectors in organs. To transmit a great amount of signals to the cerebral cortex of the brain, which is believed to be the brain’s central processing region, neurons are constructed of well-organized structures. The neurons in the brain are guided by radial glial cells (RGCs) which connect the ventricular surface to the cortical surface [28]. The RGCs have two long radial processes which are extended in opposite directions and have relatively low elastic modulus of ~600 Pa (converted from shear modulus measurements of ~200 Pa with the relation between shear and elastic modulus, E=2G (1+ν), where E: elastic modulus, G: shear modulus, and ν: Poisson ratio) [29]. Since the neurite outgrowth is directed by topographical guidance toward the longitudinal direction of RGCs and attracted toward a physically softer environment (RGCs have lower elastic modulus compared to neurons. Elastic modulus of neuron: 0.1–10 kPa [30]), neurons extend radially their structures [31].

As opposed to neurons which are only electrically active, skeletal muscle and heart tissue are active both mechanically and electrically. Skeletal muscle and heart tissue are commonly composed of muscular structures which can contract upon electrical stimuli. Skeletal muscles are composed of hundreds or even thousands of longitudinally aligned cylindrically-shaped muscle fibers. Each muscle fiber is a multinucleated cell having diameters ranging from 5 to 100 μm and lengths from 1 to 2 mm even to few centimeters [32]. In the center of these fibers, protein filaments named myofibrils exist in a tubular morphology, and are composed of contractile elements called sarcomeres, the basic functional unit for muscles. Sarcomeres contract from the inter-fibril sliding of F-actin and myosin filaments [33]. This contractility is mediated by motor neurons which are connected to PNS. Although individual sarcomeres contract ~2.4 μm (sarcomere length can change from 1.25 to 3.65 μm), greater contractions can be achieved by a serial arrangement of sarcomeric units [32,34]. Furthermore, a single muscle fiber can only exert a force of 10.2–14.3 μN FL/s (slow fiber, where FL is fiber length), 43.9–71.4 N FL/s (fast fiber), but this contractile force can be enhanced by parallel organization of fiber bundles up to 1.58 W/l (slow fiber), 7.96–10.64 W/l (fast fiber) [35].

Although cardiac muscle has similar sarcomeres, its organization and morphology is different from that of skeletal muscle. In vivo, cardiomyocytes have two-dimensional rectangular leaflet-like morphology with typical lengths of 100–150 μm and widths of 20–35 μm, unlike the cylindrical morphology of skeletal muscle fibers [36]. Such cardiomyocyte morphology is a result of the planar organization of its sarcomeres as a repeating banded structure which comprises a myofibril, being unidirectionally aligned within the cell. Specifically, for coordinated and synchronized contractions of the heart, the action potentials are conducted unidirectionally through gap junction structures termed intercalated disks (IDs) which are usually located in both of the longitudinal ends of cardiomyocytes. In certain pathologies, the distribution and location of IDs may become random. This leads to a random distribution of the action potentials generated in the sinoatrial (SA) node throughout the myocardium, giving rise to myocardial fibrillation [37]. Thus, for proper mechanical contraction and electrical conduction, unidirectionally aligned sarcomeric structures are important.

2.4. Shear stress-sensitive tissues

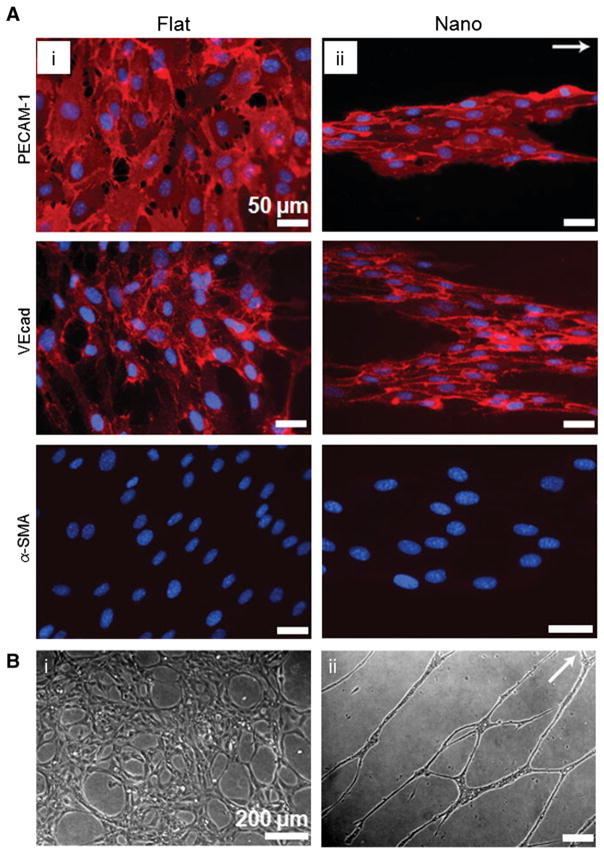

Blood vessels are tissues that are continuously exposed to mechanical stimuli, especially fluidic shear stress and cyclic expansion/contraction due to cardiac contractions. Endothelial cells (ECs) line the interior of blood vessels (endothelium) and show aligned morphology toward the longitudinal direction, responding to flow forces. Vascular tissue can be divided into a number of branches with hierarchical organizations when tissue specific functions are required, such as the filtration in the kidney, gas exchange in the lungs, and extensive branching for coronary circulation. As can be inferred from the classification ‘shear stress-sensitive’, fluidic shear stress is a crucial factor for vascular cell function including proliferation, elongation, and protein secretion. The shear stress applied to the surface of the inner vessel wall ranges from 10 to 70 dyn/cm2 (arteries), or 1 to 6 dyn/cm2 (veins) [38]. In the vascular system, basal lamina guides the endothelial cells in the blood vessel, and is composed of collagen IV and laminin-1 fibers with nanometer scale [39,40]. In addition to the physical nanostructures in natural basal lamina, nanotopographical cues can also be a possible tool for inducing and facilitating cellular functions since the mechano-receptor of shear stress might be the same with that of physical stimuli such as rigidity and topography [41]. Detailed descriptions will be given in Section 4.3. As an additional functional component, smooth muscle cells (SMCs) comprise the medial layer of the blood vessel, covering blood vessels circumferentially guided by basal lamina. The main function of SMCs is to maintain fluidic homeostasis through the interaction with ECs. In order to investigate the function of SMCs as a vascular mediator, the alignment of SMCs as well as the expression of functional markers can be achieved through culturing SMCs on micro- and nanopatterned surfaces.

3. Fabrication methods for nanotopography

3.1. Historical background

The controlled microenvironment is intended for elucidating or guiding the expression of cellular functions. To address this controllability, a great number of fabrication methods have been introduced in the last few decades. Since many reviews are currently available for numerous fabrication methods [42–49], we will focus on the methods that deal with synthetic polymers and their related fabrication techniques. Some fabrication methods described in this section are still valid for the structuring of natural polymers.

According to Moore et al., the first cell culture with topographical cue was reported by R. G. Harrison in 1914 [50]. In his seminal work, he cultured embryonic frog cells on a spider web attached on a cover slip, demonstrating guided elongation of cells along the fibers [50,51]. A few years later, in 1929, P. Weiss reported on the important role of mechanical structures, and in 1934, he further expanded the principle of topographical guidance by culturing neurons on a cover glass covered with oriented, rod-like fibrin, demonstrating aligned nerve fibers in vitro [52]. Although these pioneering works demonstrated that topographical guidance could be an important cue for cellular polarization, the underlying mechanisms could not be elucidated due to the lack of sophisticated fabrication methods.

The intracellular signaling processes responsible for these cellular responses have been revealed rapidly by introducing reproducible abrication techniques with synthetic polymers. Although various fabrication techniques were already established many years ago, the adaptation into the biological field has only been initiated recently. For example, according to Cao et al., although photolithography has been a well-established, commercially available technique in semiconductor industry in the early 1970s, its introduction as a biological platform was first explored in 1988 by Kleinfeld and coworkers [53,54]. By using this method, guided neurite outgrowth and grid formation were demonstrated. As a bottom-up approach, electrospinning was first introduced in 1934 as a patent by A. Formhals [55,56]. However, its adaptation into the biomedical engineering field occurred in the early 2000s with biodegradable poly(lactic acid) (PLA) or poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) [57,58]. Finally, the introduction of soft lithography in early 1990s by George Whitesides [59,60] has led to an enormous increase in projects and reports investigating this technology for biomedical engineering purposes. Due to the successful utilization of polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS) as a flexible mold, controlled physical topography could now be made in a cost-effective, low-expertise fashion.

3.2. Fabrication methods

Various nanofabrication methods are summarized in Table 1 in terms of the requirement of template and the type of energy sources. In general, the fabrication methods can be classified into two categories: template-assisted and template-free methods. The template-assisted fabrication methods require a certain mold which can be (i) transparent or opaque depending on the utilization of light, (ii) rigid or flexible depending on the pressure requirements, and (iii) compact or permeable to various solvents with respect to the usage of solvents. These template-assisted fabrication techniques can be further categorized with respect to the energy sources required for physical modification. The energy sources can be classified into five types: thermal, optical, physical, chemical and electrical.

Table 1.

Classification of nanofabrication methods in terms of the use of template and type of energy sources. For each method, patterning principle, pattern shapes, and materials used are summarized.

| Template | Energy source | Methods | Mechanism | Resulting patterns | Processable polymers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template-assisted | Thermal | Replica molding (RM) | Thermal cross-linking of cavity-filled prepolymer | Negative shape of the mold | Thermocurable |

| Nanoimprint lithography (NIL) | Plastic deformation of polymer resin above Tg | Negative shape of the mold | Thermoplastic, conductive | ||

| Optical | Photolithography | Solubility change upon selective UV exposure | Depends on mask design | Photo-curable | |

| UV-assisted molding | Photo cross-linking of cavity filled prepolymer | Negative shape of the mold | Photo-curable | ||

| Physical | Capillary force lithography (CFL) | Capillary rise of thermoplastic polymer resin above Tg | Partially filled negative shape of the mold | Thermoplastic, solvent soluble | |

| Micromolding in capillaries (MIMIC) | Capillary-driven microchannel filling | Negative shape of the mold | Solvent soluble | ||

| Chemical | Microcontact printing (μCP) | Transfer of materials by using the relative surface energy difference | Extruded patterns of elastomeric stamp | Proteins, SAMs | |

| Electrical | Electrochemical deposition | Electrochemical reduction of the materials on the conductive electrode | Negative shape of the mold (fully or partially filled) | Conductive | |

| Template-free | Thermal | Block copolymer (BCP) lithography | Microphase separation of two immiscible polymers | Nanoscale hole, line and lamellar structure | Block copolymer |

| Optical | E-beam lithography | Solubility change upon selective irradiation of focused electron beam | Arbitrary pattern dependent on the pathway of electron beam | E-beam sensitive | |

| Direct laser writing | Selective cross-linking of polymer by laser irradiation | Arbitrary pattern dependent on the pathway of laser beam | Photo-curable | ||

| Physical | Wrinkle | Mechanical buckling between elastic substrate and rigid film | Random or aligned micro- or nanolines | Elastomer | |

| Crack | Mechanical fracture of the stiff film adhered onto elastic substrate | Aligned or inter-crossing line pattern | Elastomer | ||

| Chemical | Dip-pen lithography | Direct writing of molecules with sharp tip | Arbitrary pattern dependent on the pathway of sharp tip | SAMs | |

| Salt leaching/gas foaming | Selective dissolution of salt particulates/bubble formation in polymer block | Polymer block with numerous voids | Solvent soluble | ||

| Electrical | Electrospinning | Electric field-induced fiber drawing from the polymer solution | Three dimensional nanofibrous mesh | Solvent soluble |

Thermocurable: poly(dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS), and other thermocurable materials.

Photo-curable: photoresist, polyurethane (PU)-based, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based, poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (pNIPAM) and others.

Thermoplastic: polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polystyrene (PS), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), polycaprolactone (PCL) and others.

Conductive: polyaniline (PANi), poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), polypyrrole (PPy) and others.

Block copolymer: polystyrene-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) (PS-b-PMMA), poly(styrene-b-ethylene oxide)(PS-b-PEO), styrene–butadiene–styrene (SBS) and others. Elastomer: usually PDMS.

Solvent soluble: thermoplastic, conductive.

E-beam sensitive: PMMA, e-beam sensitive photoresists and others. SAMs: self-assembled monolayers.

Thermal energy can crosslink prepolymers filled into the cavities of molds (replica molding, RM) [61] or plastically deform thermoplastic polymers by applying heat and mechanical pressure together (nanoimprint lithography, NIL) [62,63]. Usually utilization of thermal energy requires a long process time for crosslinking and heating/cooling. Nonetheless, such technique requires low expertise (in the case of RM) and can make fine structures down to 10 nm (in the case of NIL).

Optical energy utilizes light with the appropriate wavelength for photo crosslinking. The type of template may differ depending on the requirement of selective exposure. Photolithography selectively illuminates light through an optically pre-defined mask. Due to selective exposure, the solubility of the exposed and unexposed polymer regions becomes different, which are subsequently removed selectively by material-specific solvents [64,65]. On the other hand, ultraviolet (UV)-assisted molding utilizes physically pre-defined molds for structuring. In UV-assisted molding, photocurable prepolymers are drop-dispensed onto molds and the whole area is illuminated for a few tens of seconds, resulting in a negative replica of the mold [66]. Since a large portion of UV-curable polymers is susceptible to oxygen-inhibited crosslinking, a sheet of engineering plastics can be used as a supporting blanket to prevent oxygen penetration [67].

Physical energy utilizes capillary force as a driving force. When a liquid drop is in contact with a solid surface, Laplace pressure is generated at the liquid–solid interface. This Laplace pressure can drive liquids to rise into the mold cavity (capillary force lithography, CFL) [68,69], or attract liquid inside the microchannels (micromolding in capillaries, MIMIC) [70]. In both cases, the mold is hydrophilic enough to generate Laplace pressure, and permeable enough to allow air or solvents to dissipate during the molding process. To meet such requirements, PDMS-based materials have been widely used.

With chemical factors, pre-defined patterns can be transferred onto the target substrate similar to stamping. This process is called microcontact printing (μCP) [71]. To be used as a stamp, a material has to meet several requirements such as flexibility for conformal contact, low surface energy for efficient transfer, and inertness for minimized degradation of transferred materials. By considering such requirements, μCP usually utilizes PDMS stamps prepared from RM. Materials such as proteins, self-assembled monolayers (SAMs), or even metals and ceramics can be transferred through μCP. The minimum feature size is determined by the scale of stamp patterns.

Electrical energy utilizes electrochemical oxidation/reduction at the interface between conductive substrates and ionic solutions. When an electric field is applied between a conductive substrate and electrochemically reducible solution, the ions accumulate onto the substrate. The resulting pattern morphology can be guided by the utilization of pre-defined structures on the substrate, or certain types of mold. Although this method can present highly precise structures depending on the structural guidance, it is only applicable to ionic or conductive materials [72,73].

Template-free fabrication techniques do not require pre-defined molds. Similar to the template-assisted fabrication methods, template-free methods can be classified into five categories depending on the energy sources.

Thermal energy can facilitate nanoscale self-assembly through the mobility of the polymer chain. Block copolymer lithography (BCP lithography) utilizes the microphase separation of two immiscible polymer chains in the presence of heat or solvents. The domains of block copolymers, which have two distinctive polymer chains with the total length of few tens of nanometers chemically bound to them, are separated due to the affinity among identical polymers, resulting in regularly ordered nanostructures. With BCP lithography, lines, pillars, and pits can be fabricated with the dimension down to ~15 nm [74,75].

Optically defined structures are the results of selective illumination of light sources. In nanoscale optical patterning, patterns can only be fabricated in a serial manner, which usually requires a long process time, thus being limited to a small area. For example, electron-beam lithography (e-beam lithography, EBL) utilizes a focused electron beam for selective chain scission of photoresists. Since the diameter of the electron beam can be controlled by the current, sub 10 nm structure can be fabricated [76]. Laser direct writing uses laser as a light source. Since sub-micrometer scale structures in the different heights can be made with the point exposure of a femtosecond laser, laser direct writing can be used for fabricating complex three-dimensional nanostructures [77,78].

Physical methods without the aid of template usually utilize self assembly. Wrinkles and cracks are the results of mechanical energy storage (wrinkle) or emission (crack) processes. Wrinkling is a mechanical buckling as a result of mismatch of elastic modulus, which occurs when external forces are applied onto a bi-layered system (e.g., rigid films on top of an elastic substrate). Depending on the ratio of elastic modulus and thickness of rigid films, features with sizes from few tens of nanometers to few tens of micrometers can be fabricated. The degree of ordering or randomness can be modulated from the direction of applied forces [79,80]. Alternatively, cracking is a mechanical fracture occurring on the rigid films adhering onto an elastic substrate. The depth of the cracks can be controlled by modulating the thickness of rigid film, and spacing by applied mechanical stress [81–83].

Chemical forces are used for two-dimensional but highly ordered dip-pen lithography (DPL) and three-dimensional but less ordered salt leaching and gas foaming. Dip-pen lithography directly writes SAMs onto the substrate with a sharp tip as a consequence of chemical diffusion between tip and substrate [84,85]. Although in the first generation of DPL a single atomic force microscopy (AFM) tip was utilized, recently such a long process time has been resolved by introducing an array of sharp tips writing in parallel simultaneously [86]. Salt leaching and gas foaming similarly generate three dimensional porous polymer blocks. In salt leaching, water-soluble salt particulates are mixed with polymer solution, and then dissolved after curing, leaving behind innumerous pores [87]. Similarly, gas foaming uses gas bubbles to make voids in a polymer block [88]. However, the uniform control of gas bubbles is relatively difficult compared to that of salt particles.

An electrical energy source can be used for electrospinning. Electrospinning is a result of electric-field induced solution being pulled onto the substrate. As a consequence, three-dimensionally stacked fibril structures can be made. The diameter of fibers can be controlled by various parameters such as polymer molecular weight, concentration of solution, electric field potential, flow rate of the polymer solution and distance between needle and collector. In terms of fiber orientation, the aligned fiber mats can be fabricated with a rotating mandrel, whereas the random matrices can be fabricated with a stationary collecting plate. One of the most important features of electrospinning is that it can present three-dimensional meshes with high porosity (~90%) into which oxygen and soluble factors can penetrate [57,89,90].

4. Applications of nanotopography to tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

As described in many pioneering works, cell shape is a crucial mediator for growth and differentiation [91,92]. Recently, with the help of μCP patterning method, McBeath et al. demonstrated selective differentiation of MSCs depending on the size of micro islands [93]. Kilian et al. also showed differentiation of MSCs on contact printed topography with various geometric cues such as aspect ratio of rectangles and sharpness of polygons [94]. With unprecedented revolution of nanotechnology and bioengineering, it has been well established that the planar or three-dimensional synthetic ECM could induce morphological change through (i) the control of the number and distribution of focal adhesions and (ii) the modulation of effective modulus or protein adsorption [95]. Undoubtedly, such a generation of synthetic topography has to reflect tissue-specific natures such as protective, mechano-sensitive, electro-active and shear stress-sensitive functions.

In this section, representative examples of reconstructed tissue functions in vitro and tissue generation in vivo are described based on the tissue-specific environment. Although further studies are required for the better emulation of a sophisticated physiological environment, it is believed that the results below demonstrate the potential of creating nanotopographical guidance cues to regulate tissue functions.

4.1. Protective tissues

The main purpose of protective tissues lies in protecting intra-body organs from external damages such as mechanical impact, pathogens, and harmful chemicals. In the human body various protective tissues exist in the skin and dura mater in the brain and spinal cord. The thin membrane in the brain absorbs an external impact with mechanical damping through the cerebrospinal fluid filled beneath the arachnoid membrane, while the dura mater protects the nervous system as a rigid shield. Among these tissues, the skin has distinctive functions, such as wound healing by progressive closing of the wound with the assistance of ECM, as well as inhibition of invasion of pathogens with a sieving mechanism of ECM. Although a handful of studies has demonstrated nanotopography-guided wound healing with dura mater [96,97], our understanding is generally limited as to detailed mechanisms on directed cell migration and the role of ECM.

4.1.1. Skin

Although great advances have been made for skin replacement therapy, strategies to engineer skin must focus not only on replicating its physiology and biological stability, but also preserving the original esthetic nature of uninjured skin. Skin tissue engineering strategies focus on epidermal, dermal or composite tissue generation or regeneration. The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin, being comprised of stratified epithelial cells and resides on the basal lamina. Since the basal lamina is comprised of an ECM fiber layer, including type IV collagen, laminin, fibronectin and heparin sulfate proteoglycan [98], it has a well-defined micro- and nanotopography with a series of ridges and invaginations termed rete ridges and papillary projections [99]. This topography has been shown to modulate cell function [100]. The dermis is the collagen-rich skin layer underneath the basal lamina and is composed of a meshwork of ECM fibers with diameters in the nanoscale level (30–130 nm). These nanostructures are also responsible for modulating cell proliferation, migration, differentiation and apoptosis as well as providing mechanical support and a network that can facilitate nutrient transport and diffusion [101]. Micro- and nanofabrication techniques thus can be used to generate scaffolds which can emulate native tissue properties (such as ECM architecture), promote cell attachment and clinically assist in the healing and regeneration process.

For the efficient infiltration of host tissues in the dermis, attachment and spreading are important factors to estimate the capability of scaffold. As the dermis is comprised of a meshwork of ECM fibers, electrospinning has been employed as a tool for generating nanopatterned scaffolds for dermal regeneration. Venugopal et al. used electrospinning to create mesh fiber scaffolds of poly(caprolactone) (PCL), collagen, and PCL–collagen composite. The scaffolds could be fabricated on a large scale (11×7 cm2 scaffolds) with diameters ranging from 170 to 250 nm and with high (>90%) porosity, allowing for nutrient diffusion and cell migration. Although the human dermal fibroblasts were shown to attach to all these scaffolds, the cells exhibited a different morphology on the PCL scaffolds from that of the PCL–collagen scaffolds. The PCL–collagen blended scaffolds also were mechanically more stable than the collagen scaffolds. Moreover, PCL–collagen and collagen both demonstrated higher cell proliferation, indicating increased biocompatibility [102,103]. In parallel, individual PCL fibers were coated with collagen to improve proliferation [104]. A similar experiment using dextran/PLGA electrospun fiber scaffolds and mouse dermal fibroblasts also demonstrated cell attachment without the need for ECM precoating or treatment, with enhanced cell viability (up to 10 days) and penetration into the fiber scaffolds [105].

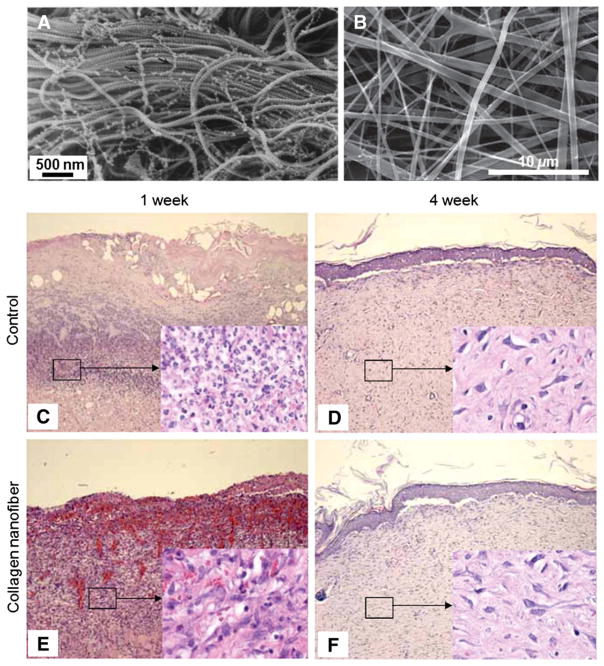

Natural biopolymers have also been explored as dermal scaffold materials. Min et al. used electrospun silk fibroin nanofibers (average diameter: 90 nm) and found higher adhesion and spreading area of human keratinocytes and fibroblasts when cultured on collagen-coated scaffolds, as compared to untreated polystyrene scaffolds and scaffolds treated with laminin and fibronectin [106]. Similar results were found in chitin scaffolds, demonstrating an increase in attachment after collagen type-I treatment [107]. Rho et al. electrospun collagen nanofiber scaffolds (average diameter: 460 nm) and crosslinked the scaffolds to improve mechanical integrity (Fig. 2). Keratinocytes adhered well and spread to collagen-coated or laminin coated scaffolds in vitro, and in vivo implantation of acellular scaffolds in an open wound healing test showed faster early-stage healing than gauze-treated controls [108]. These works suggest that for dermal repair, biocompatibility, biodegradation and mechanical stability must be considered together when selecting a scaffold material as well as determining scaffold dimension, porosity, and design.

Fig. 2.

(A) Scanning electron microscope images of collagen type VI network observed in human neonatal foreskin. (B) Electrospun type I collagen as a biomimetic nanofibrous extracellular matrix. (C–F) In vivo wound healing test at 1 and 4 weeks. In the 1-week collagen nanofiber group, surface debris disappeared and promoted proliferation of young capillaries and fibroblast was observed (E), while in the control group surface debris exists and dense infiltration of leukocytes and fibroblasts was observed, demonstrating promoted early stage skin wound healing with the assistance of nanofiber matrix (C). However, in the 4-week group, the healing processes were similar (D, F).

A is reprinted with permission from ref. [14]. B–F are reprinted with permission from ref. [108].

For epidermal repair strategies, Rheinwald et al. developed in vitro techniques that could subculture autologous keratinocytes into large sheets of epithelial tissue termed cultured epithelial autografts (CEAs) [109]. Due to the fragility and suboptimal engraftment rates, the necessity of suitable scaffolds that can support CEAs has been increasing. Smith et al. utilized photolithography to create polyvinyl alcohol/polyvinyl acetate copolymer hydrogel sheets of square-shaped micropits and microcolumns (100×100 μm2, 250×250 μm2 and 500×500 μm2 dimensions) of varying depths (5, 10 and 200 μm) [110]. The microtopographical features have to be porous to allow cell migration from the scaffold to host surfaces as well as protective to prevent cells from being sheared off the surface of the scaffold. Cell transfer from micropatterned scaffolds showed a higher grafting efficiency than flat scaffolds and provided more protection from induced shear stress [110].

Additionally, CEA engraftment was more effective on allograft, autologous or engineered dermal substrates [111–113], suggesting the necessity of further investigation of keratinocyte–surface and topography interactions, particularly at the nanoscale level to improve CEA engraftment. Pins et al. used laser machining and soft lithography to microfabricate an analog of the basal lamina with precise topographic features, i.e., channels of varying widths and depths (40 to 200 μm range), on gelatin or type I collagen–glycosaminoglycan (GAG) scaffolds [99]. These lamina analogs were laminated onto dermal substitutes (collagen sponges) to create a bio-inspired model of skin ECM. Cultured keratinocytes were seeded on the surface (lamina analog) of the scaffold and further cultured at the air–liquid interface to induce differentiation and cornification of the epidermis. After 10 days, cells formed a stratified epidermis, and even demonstrated skin-like invaginations of the epidermal surface depending on channel depth [99]. This method of generating stratified epidermis with skin-like topography has also been shown to be compatible with photolithographic techniques [114]. These surface features of skin, such as rete ridges, may also assist appropriate skin function and provide epidermal mechanical stability [115], emphasizing the importance of lamina topography for appropriate skin generation and function.

4.2. Mechano-sensitive tissues

Mechano-sensitive tissues are constantly subjected to external mechanical stresses generated by gravity, muscular contractions, and fluid flows. When the tissues are under mechanical stresses, cells and tissues adapt to their microenvironment by altering the expressions of specific ECM proteins. For example, lack of mechanical stimulus due to microgravity and prolonged bed rest induces atrophy of muscle, tendon, and bone [116,117]. On the other hand, mechanical overload on cardiac myocytes caused by high blood pressure results in pathological cardiac hypertrophy [118]. In addition, mechanically stressed dermal fibroblasts have been shown to differentiate into myofibroblasts expressing-smooth muscle actin [119]. These physiological evidences confirm that various tissues in our body are subjected to mechanical stimulations. Recently, nanotechnology research has been geared toward the fabrication of nanotopographical substrates with physiologically relevant mechanical stimuli to elucidate the role of mechanical forces on cell and tissue behavior [44,120]. These fabricated surfaces are utilized to simulate in vivo environments in a laboratory setting for the elucidation of the effects of specific ECM protein structures that are involved in mechanical stimuli [44].

A key feature of mechanosensitive tissues is that they convert mechanical signals into biochemical responses [121,122]. Many critical mechanosensitive molecules and cellular components, such as cadherins, growth factors, receptors, myosin motors, integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, stretch-activated ion channels, caveolae and other structures and signaling molecules have been identified as key molecules involved in mechanotransduction at the cellular levels. However, little is known about how these different molecules constructively function within tissue structures to produce the orchestrated cellular behavior required for mechanosensation [123]. It is well understood that ECMs function as force conduits in tissues. In addition, integrins have come to be viewed as critical mechanoreceptors within cells to translate mechano-stimulations. The ECM dynamic and matrix stiffness, through integrin receptors, are translated into cytoskeletal tensions. For example, cell traction forces in vivo are transmitted through integrins and they are resisted by the elasticity of the ECM. Several in vitro studies have confirmed the existence of traction forces experienced by cells through the use of elastic substrates that mimic ECM rigidity [124]. The process of integrin-mediated mechanotransduction relies on the ability of the proteins of focal adhesions to change their chemical activity state when physical forces are applied. Several studies have examined cellular focal adhesion behavior using a range of nanometric scale substrates with shallow pits and grooves via photolithography [125], direct laser irradiation [126], and EBL [127]. A key consequence of nanogroove substrates for the study of cell interface is that nanogrooved surfaces may induce enhanced tissue organization and facilitate active self-assembly of ECM molecules to further mediate cell attachment and orientation. Nanogroove features have been shown to modulate protein adsorption and integrin binding. Furthermore, nanogroove substrates also influence the orientation of focal adhesion and fibrinogenesis. However, recent evidences reveal that at the single cell level, cells’ immediate responses to the stiffness of their environment are independent of cell–substrate or cell–ECM forces [128]. Since tissues are interconnected with ECMs and cells, overall interplay and mechanisms of mechanotransduction at the tissue level still need to be elucidated.

4.2.1. Ligament/tendon

Almost all connective tissues are under mechanical tension, even at rest. Ligaments and tendons are fibrous connective tissues that connect bones to other bones and muscles to bones, respectively. They are comprised mainly of hierarchical collagen fibers, and fibroblasts within these ECMs are exposed to dynamic stress, and structural properties of the ligament are influenced by these forces. Ligaments and tendons have an extremely poor intrinsic capacity to regenerate, and even those that do regenerate have significantly inferior biochemical and biomechanical properties in comparison to healthy native tissue [129]. In ligaments, fibroblasts are aligned along the collagen fibers in the longitudinal direction of the tissue and in the principal strain direction. Ligament and tendon cells respond to stretching and other mechanical loads by increasing their level of intracellular calcium, and these cells release ATP in response to mechanical stimulation. Since physiological strains are involved in the maintenance of ligament function, several research projects have been conducted to elucidate mechanical stimulation in the development of an engineered ligament construct [130]. Indeed, several studies show that the rate of collagen synthesis and fibroblast differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) is enhanced by mechanical stresses [131].

For the regeneration of ligament and tendon, several options including autografts, allografts, and xenografts have been utilized for the repair or replacement of damaged tissues [132]. In addition, a variety of synthetic materials has been utilized for ligament replacements, including polytetrafluroethylene (Gore-Tex), polyester (Dacron), carbon fibers, and ligament-augmentation devices (LAD) made of polypropylene [133–135]. For tissue engineering approaches of ligament and tendon regeneration, modified synthetic biomaterial scaffolds have been developed. These scaffolds have been modified to promote cell attachment and orderly tissue repair. For example, Lin et al. showed that when polyglycolic acid (PGA) sutures coated with PCL were unbraided and seeded with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) cells, they can support fibroblast attachment and proliferation [136]. Additionally, aligned collagen and silk have been used clinically for decades, and they were subsequently adopted in order to provide the necessary mechanical competence of developing ligaments through in vitro cultivation followed by in vivo implantation [137–139]. Altman et al. have developed a processed silk scaffold that has shown promise as ligament replacement solution, and Teh et al. further utilized silk scaffolds system with knitted and aligned components for effective tendon and ligament tissue engineering [140].

Recognizing the importance of microstructure on cell adaptation, several investigators utilized novel fabrication strategies to produce nanofibers as a ligament/tendon tissue engineering solution [141]. Through the process of electrospinning, fibers with diameters at the nanoscale can be constructed with a variety of different mechanical properties [142]. Aligned nanofibers that are longitudinally oriented support fibroblasts to retain a spindle-shaped morphology and secrete more collagen matrix compared to cells seeded on randomly oriented scaffolds when subjected to uniaxial strain [137,143]. These results indicate that orientation and mechanical cues by scaffolds play an important role in ligament and tendon tissue regeneration.

4.2.2. Bone

Bone tissue engineering is an increasing field of research as the treatment of large bone defects remains an unsolved problem. The most usual strategy is to isolate MSCs or osteoblasts from the patients by biopsy and to grow sufficient quantities of tissue in vitro on implantable, three-dimensional scaffolds for use as a bone substitute. For the scaffold design, substrates with varying surface chemistry and topography have been shown to affect osteogenic differentiation. In recent scaffold designs for bone tissue engineering, researchers have included substrate system with micro-nanoscale topographies to enhance the osteogenic efficiency and bone formation [125,144–148]. For example, Ohgushi et al. demonstrated that bone marrow cells embedded in porous hydroxyapatite (HA) ceramics can induce bone formation at 3 weeks upon implantation, with potential applications to bone regeneration [148].

The bone formation depends on the cooperation of several factors such as soluble bioactive factors, physical microenvironment, and specific cell types. Of these factors, mechanical strain plays a crucial role in bone growth, homeostasis, and repair, where osteoblasts and osteocytes, as mechanosensing cells, direct these processes as can be seen from the work of Jagodzinski et al. where the effect of mechanical stretching was more pronounced than that of the chemical stimulus, dexamethasone [122]. During bone formation, bone mass is retained or increased by the activity of these mechanosensing cells upon mechanical load. In a clinical setting, mechanical stimuli are important local regulators of callus and ultimately bone tissue formation during healing of fracture repair. During orthopedic fracture repair, the mechanical loading environment has been controlled by the use of an external fixator or through defined rehabilitation programs. Recently, artificial mechanical environments have been created via fabrication of osteoinductive scaffolds that release a calcium channel agonist to modulate the mechanosensitivity of osteoblasts [149]. In addition, recently Curtin et al. have introduced highly porous collagen nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) scaffolds with plasmid-DNA delivery platform for stem cell-based bone formation [150]. nHA particles, which are calcium phosphate minerals, are bioresorbable and non-toxic. In addition, nHA particles exhibit a high binding affinity for DNA due to interaction between calcium ions in the apatite and the negatively charged phosphate groups in DNA [150].

The exact mechanism by which bone adapts to its mechanical environment is still unknown. However, the application of mechanical loads has a beneficial effect on the quality and quantity of in vitro generated bone tissues. For example, a study on mechanical loading on osteoblasts in three-dimensional collagen scaffolds under mechanical stress reported that static forces increased cell proliferation and promoted the expression of osteoblastic differentiation markers, such as alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin [151]. Alternatively, dynamic stresses enhanced the osteocalcin expression but inhibited cell growth and alkaline phosphatase expression [151]. Tanaka et al. also reported that mouse osteoblasts seeded in three-dimensional collagen scaffold under a uniaxial mechanical strain reduced the proliferation rate, while the expression of osteocalcin was increased [152]. Recently, several in vitro studies with microfabrication tools demonstrated that cell shape, independent of soluble factors, has a strong influence on the osteogenic differentiation and commitment of stem cells [93,153,154].

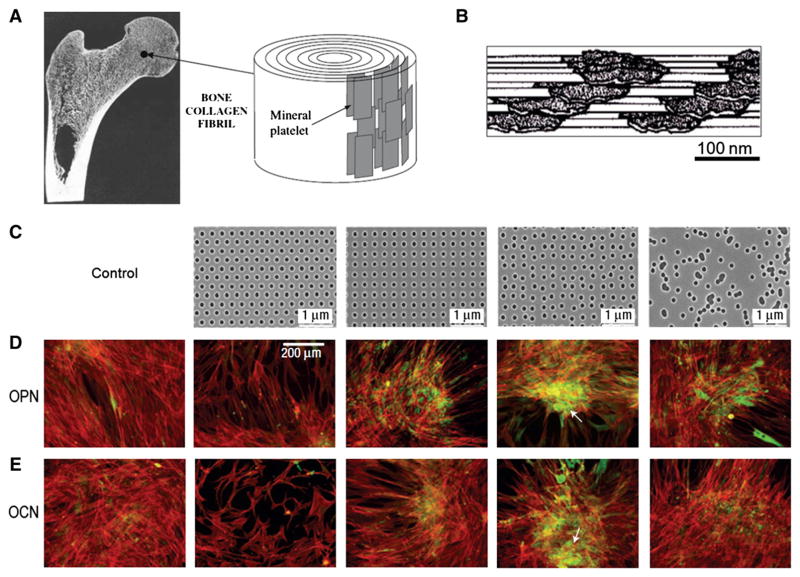

In terms of substrate design and stem cell differentiation, hydrophobic nanopillar structure and 400 nm dot patterns showed enhanced osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells [155,156]. Wilkinson et al. have shown that microtopographical features with nanoscale cues mimicking osteoclast resorption pits were used to promote in vitro bone formation without any osteogenic additives in the medium [157]. Similarly, Dalby et al. reported that the osteogenic differentiation and self-renewal of MSCs are mediated by nano patterned substrates [144,145,158] (Fig. 3). When human MSCs (hMSCs) were maintained on dot patterns and displaced randomly by up to 50 nm on box axes from their initial position, the cells showed more osteogenic differentiation while self-renewal of MSCs was evident on the substrates with ordered nano patterns. Recently, it is clearly evident that cellular interactions at the substrate interface and the induction of focal adhesion formation play central roles in the process of osteospecific differentiation and subsequent osteogenesis. The fabrication of complex three-dimensional biomedical devices to include nanoscale feature, however, is a complicated process associated with low reproducibility. Nevertheless, these nanoscale features have provided valuable information regarding specific ECM-mediated osteogenic differentiation and bone formation.

Fig. 3.

(A) The nanostructures of cortical bone composed of plate-like mineral crystals with a dimension of 2–4 nm-thick and up to 100 nm in length. (B) Cross-sectional view of bone structure. The plate-like crystals are embedded in collagen matrix with the volume ratio of mineral to matrix on the order of 1:2, demonstrating stratified stacks with slightly dislocated centers. (C) Nanopit arrays fabricated by nanoimprint lithography with poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA). The feature size is 120 nm in diameter, 100 nm in depth, 300 nm center-to-center spacing with arrangement of hexagonal, square, displaced square (±50 nm from true center) and random. (D–E) Osteopontin (OPN) and osteocalcin (OCN) of osteoprogenitors after 21 days of culture. Dense aggregates and enhanced OPN and OCN levels were observed in displaced square 50 (±50 nm from true center ) substrate (fourth column of C, D and E).

A is reprinted with permission from ref. [20]. B is reprinted with permission from ref. [19]. C, D and E are reprinted with permission from ref. [127].

4.3. Electro-active tissues

Electro-active tissues refer to those that can receive, transfer and even react with electrical signals. The electro-receiving tissues include various perception organs such as ganglion cells in the retina, mechano receptors such as the Meissner corpuscle and Ruffini endings in skin, and the cochlear cilia in inner ear. In these tissues, external stimuli are converted into electrical signals called ‘action potentials’ which are electrochemical pulses that propagate within neural and motor cells. When the action potential is generated, it is progressively transmitted along the electro-transferring nerve network which includes the PNS and CNS. Finally, the transferred information to the brain may activate certain organs such as skeletal muscle (voluntary) or heart, and the gastro intestinal tract (involuntary).

Due to the inherent environment in vivo, some of these tissues have shown distinctive responses to the applied electrical signals in vitro. For example, inspired from the inherent electric field existing in the corneal epithelial layer, Song and Zhao demonstrated that an externally applied electric field could accelerate wound closing or opening depending on the field direction [5,159]. Furthermore, Langer and coworkers demonstrated longer neurite length and increased proliferation on electrically conductive substrate [160]. In the case of skeletal muscles, myocyte showed rapid myotube formation on electrically conductive substrates even in the absence of electrical stimuli [161]. Cardiomyocytes cultured under electrical stimulus demonstrated higher ultrastructural formation and cell–cell coupling at 8 days of culture [162,163]. As can be seen from these results, electrical cues have demonstrated a significant role in tissue regeneration. Since the electrical functions of previously described tissues are subjected to the physical nanostructures in them, they must have well organized structures for effective electrical signal transfer such as unidirectional contraction of muscular tissues.

Although some electro-active tissues contain well organized nano-structures, the clinical or engineering approaches were not guided by nanotopography. For example, as the retina, responsible for receiving optical stimuli and transforming it into electrical signals, has well aligned cellular morphologies guided by RGCs, it has been widely studied with the addition of electronic devices such as imaging sensors [164] or cell sheet engineering without introduction of nanotopography [165]. The cochlear cilia in the inner ear detects motion as relative ciliary motions which may be regulated by the opening and closing of ion channels and its nanostructures are not easily replicated with topography. Furthermore, some other tissues have been treated in a macro-scale manner due to the large overall feature size. For instance, the PNS can play a critical role in signal transfer from and toward the spine, and has a relatively large size compared to the CNS (saphenous nerves have diameters of up to 2–3 cm and a length of ~40 cm) [166]. Therefore, it could be usually reconnected end-to-end with surgery when damaged. For these reasons, in this section the electro-active tissues will be confined into three organs: the heart, skeletal muscle and neurons in the brain.

4.3.1. Heart

Critical factor to heart function is the structural organization of heart tissue, specifically the elongated and anisotropic nature of cardiomyocytes which allows for anisotropic heart contraction and action potential propagation [167]. Consequently, cardiac tissue engineering seeks to engineer physiological heart tissue, which demonstrates elongated and well aligned cardiomyocytes, cell-dense monolayers, matured structural organizations such as striated sarcomeres, aligned actin cytoskeleton, and connexin43 expression at cell–cell contacts, and synchronous, anisotropic contraction as well as anisotropic action potential propagation [168]. Although many approaches have been taken to generate physiological cardiac tissue, topographical effects have increasingly come into focus as a critical aspect of the cardiac microenvironment which can modulate a variety of cell functions. As a result, micro- and nanofabrication techniques have emerged as robust and inexpensive methods for recapitulating the topography of the cardiac microenvironment to control cardiomyocyte morphology and function.

Early microfabrication-based cardiac tissue engineering approaches utilized photolithographic techniques to create anisotropic cardiac tissue. Rohr et al. used photolithography to pattern lines of photoresist on glass which prevented cell attachment, thus generating lanes of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) of varying widths, down to 65 μm on glass. The NRVMs demonstrated a more elongated morphology in the narrowest lanes [169]. Thomas et al. used the same techniques and found that NRVMs grown in narrower lanes also demonstrated greater elongation (elongation ratio: ~4) and cardiomyocytes grown in lanes generated faster propagation of action potential than NRVMs cultured on flat polystyrene surfaces [170]. McDevitt et al. used μCP of laminin lines varying from 5 to 50 μm in width which were printed on non-adhesive polystyrene surfaces (preincubated with 1% bovine serum albumin, BSA) or spin-coated on PLGA biodegradable surfaces [171]. Cultured NRVMs also demonstrated elongated myocyte morphology, upregulation of connexin43 at cell–cell borders and intercalated disks, and synchronous contraction if the distance between the NRVM lanes was small enough [171]. From these initial studies, it has become apparent that certain microfabrication techniques could be used to control the morphology and organization of myocytes.

Despite these initial advances, as cardiac tissue is extremely cell-dense, methods of controlling cardiomyocyte morphology and organization without restricting tissue formation are more desirable. Bursac et al. used microabraded polyvinyl chloride (PVC) cover slips with microgrooves ranging from 0.5 to 5 μm-wide and 0.2 to 2 μm-deep as well as microcontact printing with 12 or 25 μm-equally-spaced fibronectin lanes to culture NRVMs. Both techniques demonstrated elongated, well aligned cardiac tissue, as well as anisotropic electrical properties. Specifically, longitudinal to transverse conduction velocity ratio, a measure of the anisotropy of the action potential, increased for patterned surfaces [172]. Confluent, cell-dense tissue was best achieved by the abraded surfaces. Other microgrooved surfaces have been used to affect cardiomyocyte size as well as connexin43 and n-cadherin expression in addition to cell orientation and alignment [173–175]. Functionally, microgrooved surfaces have also been shown to alter intracellular calcium dynamics as well as expression and regulatory properties of voltage-gated calcium channels [176,177]. Au et al. combined microgrooved surfaces with electrical field stimulation in parallel and perpendicular to the groove directions. When the orientation of the microtopography and the electric field is orthogonal, NRVMs aligned to the topographical cues rather than the electrical field direction. On the other hand, cells cultured on microgrooves parallel to electrical stimulation demonstrated increased elongation, alignment, and some increased electrical functionality [178]. These approaches have sought to combine multiple aspects of the cardiac microenvironment, but still suffer from scaffold non-uniformity and lack of topographical stimuli which are more biomimetic and thus on the nanoscale level.

Another technique which has been used to generate biomimetic scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering is electrospinning. This approach is versatile as it offers the advantage of porosity for increased nutrient and waste exchange, smaller and tunable feature sizes that are more similar to ECM fiber dimensions, and the ability to generate aligned fiber scaffolds similar to the native ECM structure of the heart [179]. Shin et al. first used electrospun PCL scaffolds with fiber diameters ranging from 100 nm to 5 μm and found excellent NRVM attachment. Generated cardiac tissue was cell-dense, showing synchronized contractions [180]. Due to the porosity of the scaffolds, these cardiac monolayers could be stacked up to 5 layers thick without core ischemia [181]. However, although these scaffolds incorporated ECM-like structures and formed cell-dense tissues, they still lacked the anisotropic nature of native heart tissue. Zong et al. used a post-processing of uniaxial stretching to align and orient electrospun biodegradable fibers with an average diameter of 1 μm. NRVMs cultured on aligned fiber scaffolds demonstrated elongation and alignment along the orientation of the fibers [182]. Other techniques, such as rotary jet spinning, have also been used to create aligned fiber scaffolds which could demonstrate similar effects on cardiomyocytes [183–185].

Rockwood et al. used aligned and random electrospun polyurethane scaffolds with an average fiber diameter of 2.0 μm and showed a decrease of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) expression of NRVMs cultured on electrospun scaffolds versus tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) controls [186]. Here, a decrease of ANP is indicative of a more mature cardiomyocyte phenotype. More interestingly, aligned scaffolds showed a lower level of ANP relative to both random electrospun scaffolds and TCPS [186]. Aligned fiber scaffolds also have anisotropic mechanical properties with differential stiffness in the radial and circumferential directions [187]. This is similar to the mechanics of native heart tissue [188]. More recent advances of electrospun scaffolds include incorporation of nanofibers into collagen gels to increase cardiomyocyte attachment and mechanical properties of construct [189]. Furthermore, incorporation of bioactive [190,191] and electroconductive materials in the fiber polymers could modulate cell function and connexin43 expression [192]. To overcome diffusion limitations of 3D cardiac tissue generation, stacked, aligned fiber mats with a macroscopic biodegradable nutrient delivery system were also reported [193]. These advances are exciting but still suffer from certain limitations, namely insufficient cell characterization, reproducibility, scalability and a limited amount of materials compatible with the spinning process.

Other nanoscale approaches have examined alternatives to electrospinning to generate nanostructured scaffolds with various materials or utilize alternative techniques with greater controllability over scaffold design. Feingberg et al. used surface-initiated assembly on poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) [p(NIPAAm)] surfaces to create nanofabrics of ECM proteins, such as fibronectin, laminin and collagen. Depending on the protein, fabrics could form nanofibers<100 nm in diameter. Cardiomyocytes seeded onto generated nanofabrics adhered well, elongated and aligned to the underlying matrix [194]. Luna et al. used highly anisotropic wrinkles as a cell culture platform with periods ranged from 400 nm to 50 μm. Cultured NRVMs and embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (eSC-CMs) showed alignment, elongation and upregulation of connexin43 at cell–cell contacts [195].

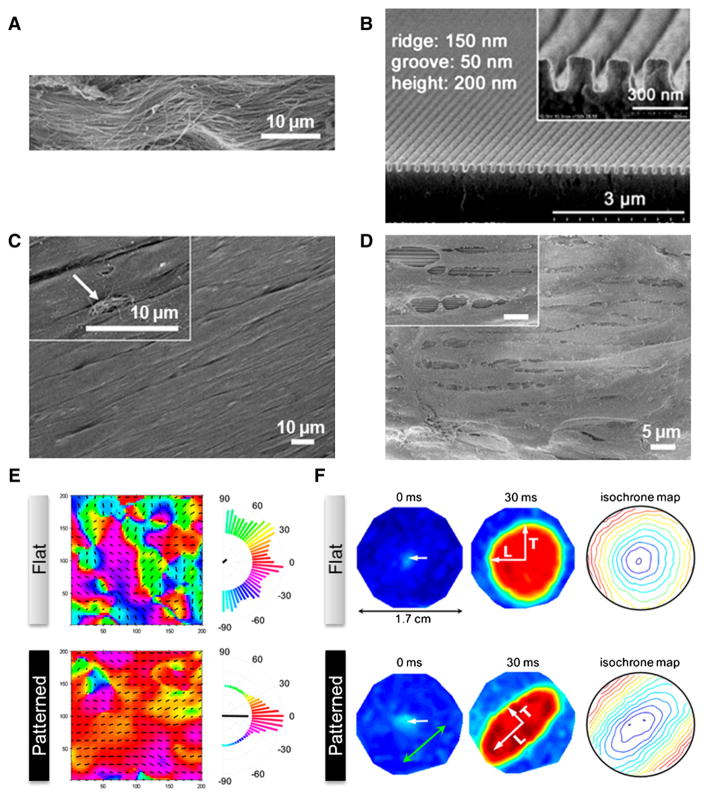

Kim et al. has used CFL to fabricate a number of well-defined nano-structured polymer substrates. They first demonstrated that NRVMs adhered more robustly to nanopillar polyethylene glycol (PEG) scaffolds having nanopillars (diameter of 150 nm, height of 400 nm) than flat PEG surfaces [196]. These nanopillars also promoted self-assembly of three dimensional aggregates of NRVMs. Kim et al. also demonstrated that using UV-assisted CFL, they could fabricate well-defined nanogrooved PEG substrates which could mimic ECM fiber dimensions (PEG scaffolds containing well-defined arrays nanogrooves with various sizes from a width of 150 nm, a spacing of 50 nm and a height of 200 nm to a width of 800 nm, a spacing of 800 nm and a depth of 500 nm) (Fig. 4). NRVMs cultured on these surfaces not only demonstrated elongation and alignment to the nanocues and formed a cell-dense monolayer, but also had anisotropic contractions and action potential generation as well as connexin43 upregulation. Further, the cells also demonstrated different sensitivities to the nanogroove dimensions. For example, the NRVMs cultured on 800 nm-wide and 800 nm-spaced scaffolds showed larger size, highest connexin43 expression upregulation and the fastest longitudinal conduction velocity [197] than other nanopatterned and flat PEG scaffolds. As a versatile nanofabrication technique, CFL has shown high controllability and reproducibility in a wide range of studies examining the precise relationship between nanotopography and cardiomyocyte function and development [69].

Fig. 4.

(A) Scanning electron microscopy image of ex vivo myocardium of adult rat heart. Unidirectionally organized matrix fibers were observed. (B) Heart-inspired nanopatterned substratum made of polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogels. (C) Magnified view of well-aligned rat myocardium. (D) Scanning electron microscopy image of NRVMs cultured on anisotropically nanofabricated substratum, showing similar morphology to (C). (E) Contraction map of NRVM monolayers cultured on flat and nanopatterns. Unlike the random contraction on flat substratum, NRVMs cultured on anisotropic nanopattern demonstrated unidirectional contraction, which is similar to real heart. (F) Action potential propagation analysis of NRVMs cultured on flat and anisotropic nanopatterns. Point stimulation of 3 Hz in 0 ms (indicated by white arrows) propagated anisotropically on cells cultured on nanopatterns, while isotropic propagation was observed in the flat case.

Reprinted with permission from ref. [167].

4.3.2. Skeletal muscle

Skeletal muscle generates force through contraction of the striated multinucleate myotubes that span the length of the muscle. These myotubes have a distinct directionality and are arranged in a parallel array, allowing for force propagation along a common axis [198]. In the mature skeletal muscle tissue, myotubes mature into myofibers, which are arranged in bundles. These fibers are surrounded by a thick ECM layer termed the perimysium [199]. The perimysium consists of collagen fibers that are organized into discrete populations which can extend along and across muscle fibers. Transverse collagen fibers interconnect muscle fibers at discrete points termed perimysial plates, and thick bands of collagen have been observed to run longitudinally along the muscle fibers, although the precise relationship between ECM–cell interactions are still poorly understood [199]. Tissue-engineered skeletal muscle must mimic the organization and physiological function of skeletal muscle. To this aim, previous studies directed the fusion of muscle precursor cells (myoblasts) into myotubes. Although myoblasts can be cultured and differentiated under typical culture conditions in vitro, the resulting myotubes lacked morphological organization, resulting in less functional tissues [198]. Thus, micro and nanofabrication strategies have been employed to direct the formation of organized, functional myotubes and skeletal muscle in vitro.

Parker et al. used μCP of ECM islands to determine whether constraining cell shape and cell traction forces could alter cell migration characteristics. C2C12 mouse myoblasts cultured on square 50×50 μm2 ECM islands formed microspikes (a cell process which helps drive cellular motion) at the corners of the ECM island, whereas cells cultured on symmetrical 50 μm diameter circle ECM islands extended cell processes at random [200]. This study showed that the resulting traction forces from a cell’s microenvironment could be used to direct cell migration. Clark et al. used photolithography and ECM precoating to create lanes of varying widths (5–100 μm) of laminin on glass. Although cell density also plays a role in myotube formation and fusion, H2Kb myogenic cells plated at high density responded to the laminin pattern and aligned themselves to the lanes. Alignment was enhanced when conditions were switched to induce differentiation and after myotube formation, supporting the hypothesis that the prealignment of myoblasts can enhance aligned myotube formation [201]. Interestingly, wider lanes did not result in wider myotube formation, but instead multiple well-aligned myotubes of a fixed width [201].

Other studies to examine the importance of contact guidance in myoblast alignment and myotube formation utilized traditional microfabrication techniques, such as photolithography, hot embossing and soft lithography to create microtopographical cues. Evans et al. used photolithography to pattern 5–100 μm wide channels of varying depths (deep: 2–6 μm, shallow: 0.04–0.14 μm) on glass and cultured fetal and neonatal murine myoblasts on these surfaces. Both neonatal and fetal myoblasts demonstrated a high degree of alignment across all groove widths in the deep microchannels. However, in shallow microchannels only fetal myoblasts responded to the topographical cues, demonstrating that structural elements in the cellular microenvironment play a role in cell positioning and alignment as well the stage of cell maturity [202]. Many subsequent studies sought to explore the sensitivity of myoblast to microenvironment dimension. Clark et al. found that nanogratings (width of 130 nm, spacing of 130 nm and depth of 210 nm) could induce alignment of H2Kb myoblasts, while myotube formation was inhibited [203]. Along with earlier results on microtopography, such nanogratings may actually inhibit myoblast reorganization as the substrate’s topography inhibits lateral migration of the cells and prevents end-to-end coupling of myoblasts [201,203]. Conversely, channels too wide (400 μm) have also only demonstrated short-range ordering of C2C12 myoblasts [204], due to perhaps features too large to restrict random orientation of myoblasts. Altomare et al. compared the effects of microcontact printed ECM with equally sized microgrooves, showing no significant difference in the alignment of C2C12 cells [205].

Further studies have shown enhanced alignment of both primary and C2C12 mouse myoblasts in deeper microgrooves of narrower widths (5 μm depth, 5–10 μm width) [206], C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes in rougher microabraded surfaces [207], in shallow wavy microgrooves (3–6 μm width, 0.4–0.7 μm depth) [208], and in deep narrow microchannels (2 μm width, 7 μm depth) [198]. Other micropatterns, such as square and diamond posts, did not inhibit the alignment of myoblast and myotube. Instead, myotubes were aligned at differing angles to the lattice pattern depending on feature size for myoblasts maximizing the contact area between the cell and the topographical surface [209]. In the study examining C2C12 cells cultured on microabraded surfaces, the expression levels of skeletal muscle specific proteins did not significantly differ between the culture conditions, suggesting that the differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts was not influenced by topographical features [207]. These studies all indicate that a specific range of topographical dimensions can profoundly affect myoblast alignment, and myotube formation and alignment.

More recent works investigating the effects of submicron and nanoscale topography on skeletal muscle have helped to elucidate cell–topography interactions. Huber et al. used electrospinning to fabricate aligned nylon 6/6 fiber scaffolds consisting of ribbons 1.5 μm×400 nm in size. C2C12s cultured on the aligned fiber scaffolds were organized accordingly to the fiber direction forming a continuous sheath, and differentiated into myotubes [210]. This approach is unique in that aligned myotubes were formed without the need for confinement of the cells, resulting in a continuous tissue. Wang et al. cultured C2C12 cells on nanogrooved substrates (450 and 900 nm width) of varying depths (100, 350 and 550 nm) and observed elongation and alignment of C2C12 to topographical cues across all substrates. Further, proliferation of C2C12 cells was inhibited and differentiation into myotubes was enhanced on grooved substrates, and C2C12s responded differentially to pattern depth, exhibiting more elongated structures in deeper grooved substrates [211]. The elongation and alignment of C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes have also been shown in oriented small diameter (10–15 nm) carbon nanowhiskers [212]. Huang et al. used uniaxial stretching of electrospun poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) scaffolds to produce oriented 500 nm diameter fiber scaffolds and compared the topographical effects on the nanoscale (electrospun PLGA nanofiber with diameter of 500 nm) to microgrooved (patterned PDMS with width/space of 10 μm width and depth of 2.8 μm) scaffolds. Although both scaffolds demonstrated elongation and alignment to the topographical cues, the nanofibers promoted longer myotube formation and inhibited cell proliferation compared to flat controls and micropatterned substrates [213]. Further exploration of micro- to nanotopographical effects on skeletal muscle cells may elucidate the crucial process in the ECM–cell interactions found in native perimysium.

4.3.3. Neurons

On the cellular scale, the nervous system consists of neurons which transmit electrochemical signals, and glial cells which support neurons. Neurons are comprised of a cell body (or soma), an axon (extended long structure to transmit signals to the synapse, the junction between neurons), and dendrites (branched structure around the cell body for receiving signal from other neurons at synapse), and axon and dendrites in vitro called neurites collectively. Some axons are covered by a myelin sheath, an insulator helping fast action potential transfer.

The center of the nervous system, the brain, takes charge of perception and information processing, controls most of motions and behaviors in body, and maintains homeostasis. The significant functions of the brain require electrochemical signal transfer mediated by neurons; therefore, the specific connections between neurons are very important. For the efficient connection and thus effective neuronal process, neurite outgrowth is a fundamental phase in which undifferentiated neurons extend to neurites before differentiating to axons and dendrites subsequently. During neurite outgrowth process, neurons extend leading tips called growth cones, and the growth cone senses the extracellular chemical, mechanical, and topographical environments, which guide the directional structure and movement of an axon and dendrites [31].