Abstract

Background

Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion (MERS) is a rare clinico-radiological entity characterized by the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) finding of a reversible lesion in the corpus callosum, sometimes involved the symmetrical white matters. Many cases of child-onset MERS with various causes have been reported. However, adult-onset MERS is relatively rare. The clinical characteristics and pathophysiologiccal mechanisms of adult-onset MERS are not well understood. We reviewed the literature on adult-onset MERS in order to describe the characteristics of MERS in adults and to provide experiences for clinician.

Methods

We reported a case of adult-onset MERS with acute urinary retension and performed literature search from PubMed and web of science databases to identify other adult-onset MERS reports from Januarary 2004 to March 2016. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was followed on selection process. And then we summarized the clinico-radiological features of adult-onset MERS.

Results

Twenty-nine adult-onset MERS cases were reviewed from available literature including the case we have. 86.2% of the cases (25/29) were reported in Asia, especially in Japan. Ages varied between 18 and 59 years old with a 12:17 female-to-male ratio. The major cause was infection by virus or bacteria. Fever and headache were the most common clinical manifestation, and acute urinary retention was observed in 6 patients. All patients recovered completely within a month.

Conclusion

Adult-onset MERS is an entity with a broad clinico-radiological spectrum because of the various diseases and conditions. There are similar characteristics between MERS in adults and children, also some differences.

Keywords: Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion, Adult-onset MERS, Encephalitis, Encephalopathy, Corpus callosum, Reversible plenial lesion

Background

Tada et al. first identified the concept of mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion (MERS) as a rare clinico-radiological syndrome in 2004 [1, 2]. In general, patients with MERS presented with mild central nervous system symptoms such as consciousness disturbance, seizures and headache and recovered completely within a month [1, 3]. MERS is divided into two types according to the lesion location. MERS type I, the typical form, most involves a singular lesion in the midline of the splenium of the corpus callosum (SCC), while MERS type II most commonly presents lesions in the symmetrical cerebral white matter or the anterior aspect of the corpus callosum with similar signal manifestations [4, 5]. The typical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features are transient high-signal-intensity on T2-weighted images (T2WI), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images (FLAIR), and diffusion-weighted images (DWI), decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of the lesion on ADC maps, and hyper-isointense signals on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) sequences without contrast enhancement [1, 4, 6]. Previous studies have identified that MERS can be triggered by infection including influenza virus [7], rotavirus [8], mumps virus [9], Mycoplasma pneumoniae [10] or Legionella pneumophila [11]. In addition to infection, MERS has also been reported to be associated with the administration of antiepileptic drugs [12–14].

Many child-onset MERS cases have been reported, most in Asia, especially Japan [1, 15]. However, adult-onset MERS is relatively rare. Here we reported a case of adult-onset MERS with acute urinary retention. It has been speculated that the characteristics of MERS in adults are different from that in children. So we utilized this opportunity to review the literature on adult-onset MERS in order to describe the clinico-radiological features and establish a clinical position of the disease.

Methods

Case presentation

A previously healthy 37-year-old man was admitted to our hospital due to a 9-day history of headache and vomiting. Ten days prior to admission, he suddenly developed a fever of 40 °C, diarrhea and headache. After taking oral antipyretics, he still had a fever of 38–39 °C. Three days before admission, his body temperature returned to normal. Two days before admission, he suffered acute urinary retention and was treated by temporary transurethral catheterization at another hospital. One day before admission, he came to our hospital for acute urinary retention and the catheter was kept. Neurological examination revealed nuchal rigidity positive. Chemistry panel and urine analysis showed no abnormalities except for an elevated blood white cell counts (10.99 × 109/L), C-reactive protein level (9.41 mg/L) and decreased serum sodium (131.8mml/L). Routine immunological screening and tumor markers were negative. Lumbar puncture showed an elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure of 190mmH2O. CSF examination demonstrated an increase in white blood cells (97/ul) and protein content (124 mg/dl). The CSF etiological examination was negative. Oligoclonal bands, IgG index and myelin basic protein were within the normal ranges in CSF. Paraneoplastic antibodies were negative. Cranial MRI scans taken on the day after admission showed abnormal signals in SCC, which was hyperintense on T2WI and DWI imaging, decreased on ADC, isointense on T1WI with no contrast enhancement (Fig. 1). The plain and enhancement spinal cord MRI showed no obvious abnormalities. He received intracranial pressure reduction, antiviral, anti-inflammatory and experimental anti-tuberculosis. His urinary retention and fever resolved within 10 days. The follow-up MRI scan taken 14 days after the initial examination showed previous lesion disappeared (Fig. 2). He was discharged home without neurological complications. The final diagnosis was MERS with acute urinary retention.

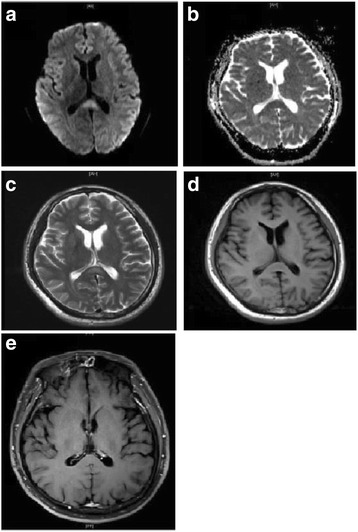

Fig. 1.

Initial cranial MRI of the patient. The lesion in the midline of SCC was hyperintensity on DWI (a) and T2WI (c), decreased ADC value (b), isointense signals on T1WI (d), and no contrast enhancement (e)

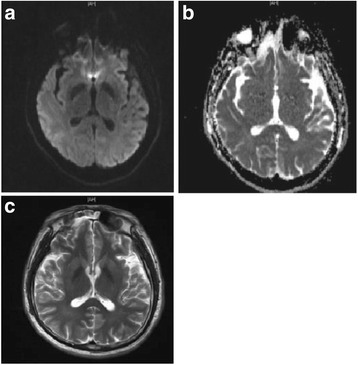

Fig. 2.

Follow up cranial MRI. The follow up cranial MRI showed no lesion on any sequence (a: DWI, b: ADC, c: T2WI)

Literature search and selection

To better understand the characteristics of adult-onset MERS, we performed a literature search to identify other reports (reviews, case reports or case series) from Januarary 2004 to March 2016, using the PubMed and web of science databases with the following terms, ‘mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion’/‘MERS’/‘reversible splenial lesion’. All pertinent English language articles were retrieved. A hand-search by reviewing the reference sections of the retrieved articles was also performed. The non-English language articles, child-onset MERS reports and not getting full-text articles were excluded. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline on selection process.

Data extraction

Two investigators collected data from the selected articles. The following information were extracted: last name of the first author, country where the study was performed, the reported patient’s age, gender, CNS symptoms, neurological examination, etiology, auxiliary examination, therapy and outcome.

Results of literature review

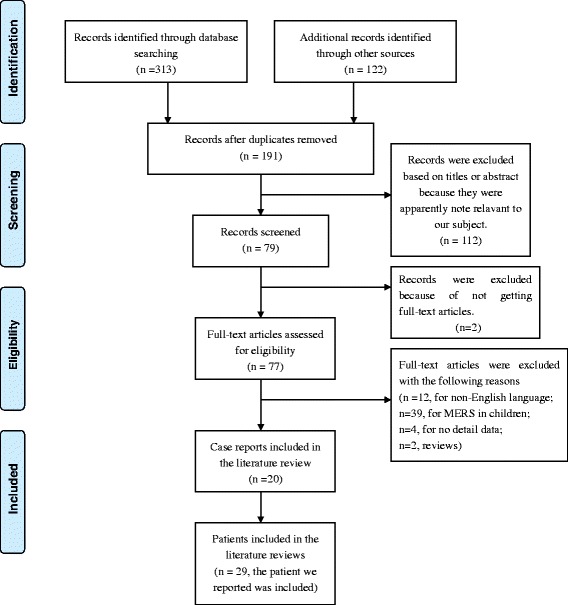

A total of 435 articles between Januarary 2004 and March 2016 were identified by preliminary electronic literature search and hand search. The selection process was presented in Fig. 3. The characteristics of the included cases were presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Flow diagram of studies selection process

Table 1.

Information of 29 adult-onset MERS cases

| Reported by, location, reference | Case no. | Sex, age (years) | symptomsis | Neurological examination | Etiology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, China | 1 | M, 37 | Fever, UT | cervical rigidity (+) | NQ |

| Tada et al. [1] Japan | 2 | F, 59 | Fever, vertigo, lethargy | NS | NQ |

| 3 | F, 18 | Fever, seizure, delirium | NS | NQ | |

| 4 | M, 19 | Fever, cough, delirium, seizure | NS | NQ | |

| 5 | F, 25 | Fever, vesicular, headache, drowsiness, nausea | NS | VZV | |

| 6 | M, 22 | Fever, hallucination, delirium | NS | NQ | |

| Jun-ichi et al. [22] Japan | 7 | M, 31 | Headache, fever, drowsiness, disorientation, memory disturbance | drowsiness, disorientation, memory disturbance | NQ |

| Jeong-Seon et al. [6] Korea | 8 | M, 59 | Dysarthria, drowsiness,fever | Normal | NQ |

| Nida Tascilar et al. [27] Turkey | 9 | F, 26 | Fever, headache, phonophobia, photophobia, dizziness, UT | Neck stiffness (+), positive Kernig’s sign, right truncal and gait ataxia | NQ |

| Makiko et al. [28] Japan | 10 | F, 23 | Fever, headache, UT | Unsteady gait, patellar tendon reflexes, plantar reflexes, abdominal wall reflexes diminished | NQ |

| Henning Vollmann et al. [29] Germany | 11 | M, 42 | Fever, vomit, headache | Mild ataxia, disturbance of gait | Tick-bites |

| Dimitri Renard et al. [30] France | 12 | M, 43 | Stuporous state | GCS E4M5V2, mutism, persistent hiccup | Anti-Yo rhombenceh- halitis |

| Shingo Mitraki et al. [31] Japan | 13 | M, 29 | Consciousness disturbance | Drowsy, disoriented | pneumonia |

| Hideki Shibuya et al. [10] Japan | 14 | M, 30 | Fever, consciousness disturbance | Glasgrow coma scale: E4V1M6 | Mycoplasma- pneumoniae |

| Balasubramanyam Shankar et al. [32] India | 15 | F, 28 | Fever, vomiting, paresthesia | Drowsy, neck rigidity, up going plantar reflex | NQ |

| Soon Young Ko et al. [33] Korea | 16 | M, 30 | Fever, alalia | dysarthra | Nonfulminant hepatitis A |

| Makoto Hibino et al. [34] Japan | 17 | F, 24 | Fever, diarrhea, abdominal pain, weakness of right upper extremity | Right-side hemiparesis, hemianesthesia, Chaddock (+) | adenovirus |

| Yuji Tomizawa et al. [11] Japan | 18 | M, 49 | Fever, gait difficulty | Wide-based gait, fine postural tremors, mildly exaggerate deep tendon reflexes | Legionella pneumophila- serogroup 2 |

| Robert M et al. [35] America | 19 | M, 41 | Fever, headache, delirium, consciousness disturbance, tremor, gait instability, paresthesias, UT | Slow thought, mild difficulty finding words, intention tremor of the left arm, dysmetria of lower extremities, broad-based gait | ipilimumba |

| Jing Jing Pan et al. [36] China | 20 | F, 18 | Fever | (−) | NQ |

| 21 | M, 26 | Fever, acute UT | Nuchal rigidity (+) | NQ | |

| 22 | F, 23 | Fever, headache, disturbance of consciousness | Kerning (+) | C-section | |

| 23 | M, 21 | Fever, headache, acute UT, intestinal obstruction | Kerning (+) | NQ | |

| Shuo Zhang et al. [37] China | 24 | F, 26 | Headache, fever, seizure, somnolence | Somnolence | Mycoplasm-a |

| 25 | F, 34 | Dizziness, fever, somnolence | Somnolence | Mumps virus | |

| 26 | M,25 | Headache, fever, cognitive impairment, behavioral disorders, confusion | Cognitive impairment, behavioral disorders, confusion | Herpes simplex virus | |

| Eylem Degirmenci et al. [38] Turkey | 27 | M, 27 | Headache, apathy, nausea, vomiting | Bilateral papilledema, mildly altered mental status | NQ |

| Naila Alakbarvova et al. [39] Turkey | 28 | M, 46 | Headache, vomiting, nausea, diarrea, abdominal pain, generalized tonic-clonic seizure | Confusing with time disorientation | Amanita phalloides intoxication |

| Matthias Gawlitza et al. [40] Germany | 29 | F, 28 | disorientated | Disorientated, confusion | Hemolytic uremic syndrome |

M male, F female, UT urinary retention, NS no statement, NQ no required, VZV varicella zoster virus

Table 2.

Auxiliary examination and treatment of 29 adult-onset MERS cases

| Case no. | Initial examination | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (109/L) | CRP (g/L) | Serum sodium (mmol/L) | CSF WBC (106/L) | MRI | EEG | ||

| 1 | 10.99 | 9.41 | 131.8 (hyponatremia) | 97 | SCC | NE | mannitol, low dose methylprednisolone, ACV, anti-tuberculosis |

| 2 | NS | NS | NS | 500 | SCC | Slow BA | ACV, antibiotics |

| 3 | NS | NS | NS | 17 | SCC | Slow BA and spikes | PB, PSL |

| 4 | NS | NS | NS | Normal | SCC | Slow BA | ACV, PHT, PSL |

| 5 | NS | NS | NS | NE | SCC | NE | ACV |

| 6 | NS | NS | NS | Normal | SCC | Slow BA | ACV, antibiotics, PSL |

| 7 | 18.8 | 17.0 | NS | 253 | Entire CC and peripheral WM | NS | antibiotics |

| 8 | normal | normal | normal | normal | SCC and frontal WM | NS | No specific therapy |

| 9 | normal | normal | normal | 408 | SCC | normal | Ceftriaxone, ACV, ampicillin, catheterization |

| 10 | normal | normal | normal | normal | SCC, WM | NS | Methylprednisolone pulse, PSL, catheterization |

| 11 | NS | normal | 132 (hyponatremia) | 33 | SCC | NS | Ceftriaxone, ACV, symptomatic therapy of headache and fever |

| 12 | NS | normal | 133 (hyponatremia) | 6 | SCC, frontoparie-tal WM, putamina, thalami | Diffuse slowing wave | Antiepileptic treatment, methylprednisolone pulse, immunoglobulin treatment |

| 13 | elevated | elevated | NS | normal | Entire CC | NS | methylprednisolone pulse, immunoglobulin treatment |

| 14 | NS | NS | NS | NS | SCC | NS | Levofloxacin |

| 15 | NS | NS | NS | 60 | SCC, bilateral WM | Slow activity, frontal sharp wave | Empirical corticosteroids and ACV |

| 16 | 3.48 | NS | 138 | NS | SCC | abnormal | hemodialysis |

| 17 | normal | 12.21 | normal | NE | SCC | NS | No specific therapy |

| 18 | elevated | 22.9 | 130 | 3 | SCC | NS | Antibiotics |

| 19 | normal | normal | normal | 128 | SCC | NS | oral PSL and methylprednisolone pulse |

| 20 | 6.08 | normal | 137.0 | 90 | SCC | abnormal | methylprednisolone pulse, oral PSL |

| 21 | 7.10 | normal | 130.2 | 100 | SCC, insula, caudate nucleus | abnormal | Oral methylprednisolone and PSL |

| 22 | 11.20 | normal | 138.6 | 12 | SCC | abnormal | Oral methylprednisolone and PSL |

| 23 | 8.20 | normal | 126.5 | 80 | SCC | abnormal | Oral PSL |

| 24 | NS | NS | NS | 3 | SCC | Occipital slow waves | Mannitol, diazepam, macrolides antibiotics and moxifloxacin |

| 25 | NS | NS | NS | 7 | SCC | Occipital slow waves | Interferon, ribavirin |

| 26 | NS | NS | NS | 112 | SCC | Occipital slow waves | Ganciclovir, mannitol, antibiotics |

| 27 | normal | normal | normal | 150 | SCC | NS | Acetazolamide, antibiotics, oseltamivir |

| 28 | 17.8 | NQ | normal | normal | SCC | NS | Risperidone, clozapine, venlafaxine and diazepam, antipsychotic and intoxication treatment |

| 29 | NS | NS | NS | NS | SCC | NS | eculizumab |

WBC white blood cell, CRP C-reactive protein, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, EEG electroencephalography, NE no examined, NS no statement, BA basic activity, ACV acyclovir, PB Phenobarbital, PSL prednisolone, PHT phenytoin, WM white matters

Of the 29 adult-onset MERS patients, 11 were from Japan, 8 from China, 3 from Turkey, 2 from Germany, 2 from Korea, 1 from France, 1 from India and 1 from America. From a geographical point of view, 86.2% of the countries were in Asia (25/29), especially in Japan (11/29).

The age of onset varied between 18 and 59 years old, with an average of 31. Twelve patients were females (41.38%) with a 12:17 female-to-male ratio. Fifteen patients had identified causes, including 5 virus infections, 3 pneumoniae, and 1 mycoplasma infection. One patient developed MERS due to Amanita phalloides toxication, one because of tick-bites. One patient had emotional and behavioral changes presenting with auditory hallucinations within 10 days after C-section.

Fever had preceded or simultaneously presented with neurologic symptoms in 24 patients. Twelve patients complained of headache while having MERS, and disturbance of consciousness was observed in 15 cases. Seizure occurred in 4 cases, and acute urinary retention in 6 patients. 75.9% of the patients (22/29) had an isolated lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum. Six patients had lesions in both splenium and extracallosal. One patient had lesions in the entire corpus callosum. Lumbar punctures were performed in 23 patients, 15 of which had elevated CSF WBCs. Sixteen patients had their serum sodium reported, 6 of which had decreased levels. EEG was performed in 23 patients, 14 of which were abnormal.

The patients were treated with antiviral therapy, antibiotics, corticosteroids, IVIG, intravenous osmotic diuretic and isotonic fluid. Thirteen patients received corticosteroids therapy, 5 of which received a methylprednisolone pulse therapy. No case resulted in neurological sequelae.

Discussion

We reported a previously healthy 37-year-old man who suffered MERS associated with acute urinary retention. A lesion in the SCC resulting in acute urinary retention has rarely been reported. We considered acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) being the main differential diagnosis. In comparison with the lesions in MERS which show no contrast enhancement and usually disappear quickly [1], the corpus callosum lesions in ADEM are usually asymmetrical, contrast-enhancing, extend to the white matter and spinal cord [16], and resolve over weeks to months. Our patient’s cranial MRI showed an isolated abnormal signal in the SCC with no contrast enhancement. His spinal cord MRI showed no obvious abnormalities. The follow-up MRI scan revealed normalized findings within two weeks. So the patient was diagnosed as MERS instead of ADEM.

At first, a reversible isolated SCC lesion on MRI was diagnosed as MERS [1]. Recent studies suggested additional similar lesions in the cerebral white matter and anterior aspects of the corpus callosum in some encephalitis/encephalopathy patients should also been regarded as MERS (type 2 MERS) [4, 5]. Since the radiologic range of MERS had been expanded, patient no.7, 8, 10, 12, 15, 21 and 29 were included in the literature review.

Similar to child-onset MERS, most adult-onset MERS patients were also reported in Asia, including Japan, China and India. Interestingly, the majority cases were reported in recent five years. The phenomenon may be related to ethnics and social factors, as well as lack of diagnostic awareness and criteria before 2011. The common neurological manifestations of MERS in adult were headache and disturbance of consciousness. However, disturbance of consciousness and seizures were the most common neurological symptoms in children [15]. We suspect that it is related to children’s immature central nervous system and blood brain barrier.

The pathogenesis of MERS is still unknown. There are several hypotheses, including intramyelinic edema, axonal damage, hyponatemia, and oxidative stress [1, 17, 18]. High signal intensity on DWI and decreased ADC values of white matter have been observed in MERS. The possible explanation for this is intrmyelinic edema resulting from separation of myelin layers [19, 20] and local infiltration of inflammatory cells [1, 3]. In this review, we found that more than half (15/23) cases had elevated white cells in the CSF. A previous small sample study reported that patients with MERS has an elevated IL-6 and IL-10 levels in CSF, however, the sample is not enough for any conclusions to be drawn [17]. ADC may return to normal within a week if the intramyelinic edema or inflammatory infiltrate resolves quickly. Takanashi et al. [21] reported that most patients with MERS had mild hyponatremia with a mean serum sodium level (131.0 ± 4.1 mmol/L) lower than that of the healthy group. Our review revealed that 6/16 MERS patients had hyponatremia upon admission. All these indicate that hyponatremia might be a possible cause of MERS. Taken all together, MERS is a rare syndrome with unclear pathogenesis. None of the existing hypotheses explains why MERS specially involves the site splenium.

In any patients presenting with symptoms of encephalitis/encephalopathy who are found to have lesions in the white matter, ADEM should be included in the differentials [1, 4, 22, 23]. ADEM is a post-infectious inflammatory disorder which can present with seizures, focal neurological signs or altered mental status days to weeks after the presumed infections [24]. MRI with contrast shows various enhancements of the lesions in ADEM depending on the stages of the acuity [24]. Other differential diagnoses include posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (usually hypertension-related and has subcortical white matter lesion), multiple sclerosis (characteristic relapsing-remitting course), Marchiafava-Bignami disease (often seen in alcoholism), ischemia (usually irreversible and has vascular territory distributions), diffuse axonal injury (head trauma-related), lymphoma (positive contrast enhancement), and extrapontine myelinolysis (happens with electrolyte abnormality) [25].

Even though the evidence of methylprednisolone pulse therapy and IVIG’s efficacy on MERS is still lacking, they are recommended for patients with infectious encephalopathy regardless of the pathogen or clinicl-radiological syndromes [26]. In this review, only five MERS patients were treated with methylprednisolone pulse therapy and two with IVIG treatment. However, all patients without methylprednisolone pulse therapy or IVIG recovered clinically completely, which suggests that those treatments may not be necessary.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we reported a case of an adult-onset MERS with acute urinary retention. Taken together with the previously reported cases, we suggest that MERS in adults is an entity with a broad clinico-radiological spectrum and the prognosis is good. From a geographical point of view, most adult-onset MERS patients were also reported in Asia. The common neurological manifestations were headache and disturbance of consciousness. There are similar characteristics between MERS in adults and children, also some differences.

Acknowledgment

None.

Funding

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81271309) and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Youth Programme (QML20150303).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

JLY provided the adult-onset MERS case. WLH conceived and designed the experiments. SNY performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. SKW performed the studies selection process. WQ and LY collected data from the selected articles. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The patient agreed his medical records, images to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the Medical Ethical Research Committee of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University. The patient gave consent to participate in this study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- ADEM

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- MERS

Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion

- SCC

Splenium of the corpus callosum

References

- 1.Tada H, Takanashi J, Barkovich A, et al. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Neurology. 2004;63:1854–1858. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000144274.12174.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Monco JC, Cortina IE, Ferreira E, et al. Reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES): what's in a name? J Neuroimaging. 2011;21:e1–e14. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2008.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takanashi J-i. Two newly proposed infectious encephalitis/encephalopathy syndromes. Brain Dev. 2009;31:521–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Takanashi J, Barkovich A, Shiihara T, et al. Widening spectrum of a reversible splenial lesion with transiently reduced diffusion. Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:836–838. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Notebaert A, Willems J, Coucke L, Van Coster R, Verhelst H. Expanding the spectrum of MERS type 2 lesions, a particular form of encephalitis. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;48:135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho J-S, Ha S-W, Han Y-S, et al. Mild encephalopathy with reversible lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum and bilateral frontal white matter. J Clin Neurol. 2007;3:53–56. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2007.3.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takanashi J-i, Barkovich AJ, Yamaguchi K-i, Kohno Y. Influenza-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum: a case report and literature review. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:798–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Fuchigami T, Goto K, Hasegawa M, et al. A 4-year-old girl with clinically mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion associated with rotavirus infection. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:149–153. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.J-i T, Shiihara T, Hasegawa T, et al. Clinically mild encephalitis with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) after mumps vaccination. J Neurol Sci. 2015;349:226–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibuya H, Osamura K, Hara K, Hisada T. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Intern Med. 2012;51:1647–1648. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomizawa Y, Hoshino Y, Sasaki F, et al. Diagnostic utility of Splenial lesions in a case of Legionnaires’ disease due to Legionella pneumophila Serogroup 2. Intern Med. 2015;54:3079–3082. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SS, Chang K-H, Kim ST, et al. Focal lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum in epileptic patients: antiepileptic drug toxicity? Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polster T, Hoppe M, Ebner A. Transient lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum: three further cases in epileptic patients and a pathophysiological hypothesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:459–463. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.4.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda M, Shiroyama T, Tsukahara H, Shimono T, Aoki S, Takeda K. Transient splenial lesion of the corpus callosum associated with antiepileptic drugs: evaluation by diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1902–1906. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karampatsas K, Spyridou C, Morrison IR, Tong CY, Prendergast AJ. Rotavirus-associated mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS)—case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:1. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barkovich AJ. Pediatric neuroimaging: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyata R, Tanuma N, Hayashi M, et al. Oxidative stress in patients with clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) Brain Dev. 2012;34:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.J-i T, Maeda M, Hayashi M. Neonate showing reversible splenial lesion. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1481–1482. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.9.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelbrecht V, Scherer A, Rassek M, Witsack HJ, Mödder U. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the brain in children: findings in the normal brain and in the brain with white matter diseases 1. Radiology. 2002;222:410–418. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2222010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips MD, McGraw P, Lowe MJ, Mathews VP, Hainline BE. Diffusion-weighted imaging of white matter abnormalities in patients with phenylketonuria. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1583–1586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takanashi J-i, Tada H, Maeda M, Suzuki M, Terada H, Barkovich AJ. Encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion is associated with hyponatremia. Brain Dev. 2009;31:217–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Takanashi J-i, Hirasawa K-i, Tada H. Reversible restricted diffusion of entire corpus callosum. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247:101–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hong JM, Park MS, Jun D. Transient splenial lesion of the corpus callosum in patients with infectious disease. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2005;23:667–670. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyken PR. Viral diseases of the nervous system. Pediatr Neurol. 1994;1:499–501. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friese S, Bitzer M, Freudenstein D, Voigt K, Küker W. Classification of acquired lesions of the corpus callosum with MRI. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:795–802. doi: 10.1007/s002340000430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizuguchi M, Yamanouchi H, Ichiyama T, Shiomi M. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza and other viral infections. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tascilar N, Aydemir H, Emre U, Unal A, Atasoy HT, Ekem S. Unusual combination of reversible splenial lesion and meningitis-retention syndrome in aseptic meningomyelitis. Clinics. 2009;64:932–937. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000900017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitami M, Kubo S-i, Nakamura S, Shiozawa S, Isobe H, Furukawa Y. Acute urinary retention in a 23-year-old woman with mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:159. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vollmann H, Hagemann G, Mentzel H-J, Witte OW, Redecker C. Isolated reversible splenial lesion in tick-borne encephalitis: a case report and literature review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113:430–433. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renard D, Taieb G, Briere C, Bengler C, Castelnovo G. Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial, white matter, putaminal, and thalamic lesions following anti-Yo rhombencephalitis. Acta Neurol Belg. 2012;112:405-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Mitaki S, Onoda K, Ishihara M, Nabika Y, Yamaguchi S. Dysfunction of default-mode network in encephalopathy with a reversible corpus callosum lesion. J Neurol Sci. 2012;317:154–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shankar B, Narayanan R, Muralitharan P, Ulaganathan B. Evaluation of mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) by diffusion-weighted and diffusion tensor imaging. BMJ case reports. 2014;2014:bcr2014204078. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko SY, Kim BK, Kim DW, et al. Reversible splenial lesion on the corpus callosum in nonfulminant hepatitis a presenting as encephalopathy. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20:398–401. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2014.20.4.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hibino M, Horiuchi S, Okubo Y, Kakutani T, Ohe M, Kondo T. Transient Hemiparesis and Hemianesthesia in an atypical case of adult-onset clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible Splenial lesion associated with adenovirus infection. Intern Med. 2014;53:1183–1185. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conry RM, Sullivan JC, Nabors LB. Ipilimumab-induced encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:598–601. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan JJ, Zhao Y-y, Lu C, Hu YH, Yang Y. Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion: five cases and a literature review. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:2043–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Zhang S, Ma Y, Feng J. Clinicoradiological spectrum of reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES) in adults: a retrospective study of a rare entity. Med. 2015;94(6):e512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Degirmenci E, Degirmenci T, Cetin EN, Kıroğlu Y. Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) in a patient presenting with papilledema. Acta Neurol Belg. 2015;115:153–155. doi: 10.1007/s13760-014-0314-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alakbarova N, Eraslan C, Celebisoy N, Karasoy H, Gonul AS. Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) development after Amanita phalloides intoxication. Acta Neurol Belg. 2015:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Gawlitza M, Hoffmann KT, Lobsien D. Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible Splenial and Cerebellar lesions (MERS type II) in a patient with hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) J Neuroimaging. 2015;25:145–146. doi: 10.1111/jon.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.