Abstract

Objective

Readmission rate is increasingly used as a quality outcome measure after surgery. The purpose of this study was to establish, using a national database, the baseline readmission rates and risk factors for readmission after pediatric neurosurgical procedures.

Methods

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program–Pediatric database was queried for pediatric patients treated by a neurosurgeon from 2012 to 2013. Procedures were categorized by current procedural terminology code. Patient demographics, comorbidities, preoperative laboratory values, operative variables, and postoperative complications were analyzed via univariate and multivariate techniques to find associations with unplanned readmission within 30 days of the primary procedure.

Results

A total of 9799 cases met the inclusion criteria, 1098 (11.2%) of which had an unplanned readmission within 30 days. Readmission occurred 14.0 ± 7.7 days postoperatively (mean ± standard deviation). The 4 procedures with the highest unplanned readmission rates were CSF shunt revision (17.3%), repair of myelomeningocele > 5 cm in diameter (15.4%), CSF shunt creation (14.1%), and craniectomy for infratentorial tumor excision (13.9%). Spine (6.5%), craniotomy for craniosynostosis (2.1%), and skin lesion (1.0%) procedures had the lowest unplanned readmission rates. On multivariate regression analysis, the odds of readmission were greatest in patients experiencing postoperative surgical site infection (SSI; deep, organ/space, superficial SSI and wound disruption: OR > 12 and p < 0.001 for each). Postoperative pneumonia (OR 4.294, p < 0.001), urinary tract infection (OR 4.262, p < 0.001), and sepsis (OR 2.616, p = 0.006) also independently increased the readmission risk. Independent patient risk factors for unplanned readmission included Native American race (OR 2.363, p = 0.019), steroid use > 10 days (OR 1.411, p = 0.010), oxygen supplementation (OR 1.645, p = 0.010), nutritional support (OR 1.403, p = 0.009), seizure disorder (OR 1.250, p = 0.021), and longer operative time (per hour increase, OR 1.059, p = 0.014).

Conclusions

This study may aid in identifying patients at risk for unplanned readmission following pediatric neurosurgery, potentially helping to focus efforts at lowering readmission rates, minimizing patient risk, and lowering costs for health care systems.

Keywords: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, quality outcome, pediatric neurosurgery, readmission

Unplanned readmissions after surgery present medical and financial challenges for health care systems and have emerged as an important quality and efficiency measure.2,14,18 Recent health care reforms have led the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to penalize providers for higher rates of unplanned readmission.7 Furthermore, unplanned readmission provides a quality outcome metric that may prove useful in quality improvement, patient risk stratification, and counseling patients and families prior to operations.2,14,18 Previous studies have demonstrated that readmission in pediatric patients can be accurately predicted from preexisting patient conditions and severity of admission.3,13

Unplanned readmission has not been well studied in pediatric neurosurgery despite growing attention paid to unplanned readmission as a quality outcome measure. Pediatric neurosurgery had the highest morbidity and mortality rates of any pediatric surgical specialty in a beta phase report of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality Improvement Program–Pediatric (NSQIP-P) database, indicating a need to assess patient risk factors for complications, readmission, and other outcome measures in neurosurgery.4 Previous studies have investigated return to system (readmission or reoperation) after pediatric neurosurgery at a single institution9,21,26 and 30-day outcomes after pediatric shunt surgery;20 to our knowledge, however, no study has used a national, multiinstitutional patient database with follow-up to analyze risk factors for readmission after any pediatric neurosurgical procedure. Identifying the baseline rate of readmission for common pediatric neurosurgical procedures is useful to provide a benchmark for quality improvement efforts. Additionally, examining the risk factors for unplanned readmission will facilitate evidence-based patient risk stratification by health care systems to develop guidelines to reduce the likelihood of unplanned readmission.

The purpose of this study was to analyze patient and operative risk factors for unplanned readmission within 30 days of primary pediatric neurosurgical procedures by using a national surgical patient database with follow-up.

Methods

Data Source

The ACS-NSQIP-P is a nationwide, prospectively collected patient database with over 50 participating institutions and more than 300 patient variables.1 It includes the following de-identified and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant variable categories: patient demographics, comorbidities, operative variables, preoperative lab values, primary procedure current procedural terminology (CPT) codes, ICD-9 codes, and 30-day postoperative events such as readmission, reoperation, mortality, and complications.

Rates of discrepancies between data abstractors are less than 2% as data abstractors are trained by the ACS to ensure quality.1 Postdischarge 30-day follow-up occurs by telephone or letter.1 Previous studies have shown that the NSQIP-P achieved 91.4% confirmed 30-day follow-up.4 Institutional participation in the NSQIP is associated with reductions in postoperative adverse events11 and allows for a more thorough risk-adjusted analysis compared with administrative databases.25 The NSQIP has been shown to accurately capture all-cause and unplanned readmission occurrences, as compared with medical records information regarding cause of readmission.22 Our institution does not require institutional review board approval for NSQIP studies given that NSQIP data are nonidentifiable and HIPAA compliant.24

Data Acquisition

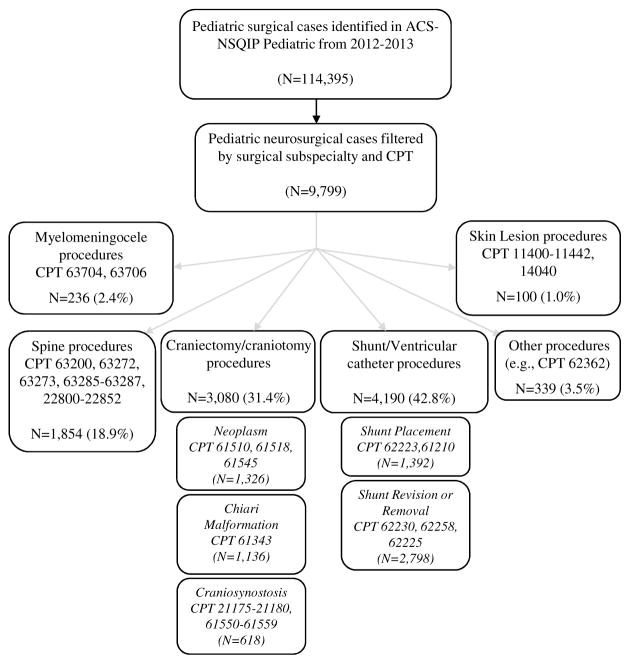

We queried the NSQIP-P database for patients younger than 18 years (at the time of the procedure) who had undergone a procedure performed by a neurosurgeon or pediatric neurosurgeon in the period from 2012 to 2013. Procedures were grouped by CPT codes into the following procedural categories: spine; craniotomy for craniosynostosis; craniotomy for neoplasm; craniotomy for Chiari decompression; shunt or ventricular catheter placement; shunt or ventricular catheter revision, removal, or irrigation; myelomeningocele (MMC) repair; skin lesion; and other. Procedure categories and specific CPT codes within each category are listed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Cohort selection by surgical subspecialty and procedural classification by CPT code.

Patient demographics included age, sex, and race. Patient comorbidities of interest included obesity, pulmonary comorbidity, gastrointestinal comorbidity, renal comorbidity, CNS comorbidity, cardiac comorbidity, steroid use (within 30 days before the principal procedure or at the time the patient was being considered as a candidate for surgery; did not include short-term use, such as a 1-time pulse, limited short course, or a taper of less than 10 days), chemotherapy within 30 days prior to surgery, radiotherapy within 90 days prior to surgery, open wound (with or without infection), tracheostomy at the time of surgery, immune disease or immunosuppressant use, nutritional support (intravenous or nasogastric tube), bleeding disorder, hematological disorder, current or previous history of malignancy, history of prematurity, intraventricular hemorrhage, preoperative systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis within 48 hours prior to surgery, and congenital malformation of any organ system (detailed list of conditions included within each NSQIP-P categorical comorbidity variable shown in online-only Supplement S1).

Operative and hospital variables of interest included hospital length of stay; inpatient or outpatient status; concurrent procedure status; prior operation within 30 days; transfer status; discharge destination; operative time; American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score; blood transfusion; elective, urgent, or emergent triage; and wound classification.

Preoperative lab values of interest included hypoalbuminemia, hyponatremia, hypernatremia, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, thrombocytopenia, elevated aspartate transaminase (AST), elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN), abnormal prothrombin time (PT), and abnormal partial thromboplastin time (PTT).

Postoperative complications included infections (surgical site infection [SSI], sepsis, urinary tract infection [UTI], pneumonia, central line bloodstream infection), wound disruption, unplanned intubation, renal failure or insufficiency, coma lasting more than 24 hours, cerebrovascular accident (CVA; stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage) or intracranial hemorrhage, seizure, peripheral nerve injury, cardiac arrest, graft or prosthesis failure, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism (PE). The NSQIP-P data on time to postoperative complications were analyzed.

Unplanned readmission is defined in the NSQIP database as “any unplanned readmission for any reason within 30 days of the principal surgical procedure. The readmission has to be classified as an ‘inpatient’ stay by the readmitting hospital, or reported by the patient/family as such.”1 Unplanned readmission is coded in the NSQIP “if the readmission was unplanned.” Previous studies have demonstrated that an unplanned readmission designation in the NSQIP has greater than 95% agreement with hospital chart records regarding planned versus unplanned readmission designation.22

We defined readmission risk factors as any patient characteristic or event (pre- or postoperatively) that increased the likelihood of postoperative readmission. This definition included postoperative complications (for example, SSI) that could also be reasons for readmission.

Data Analysis

Univariate analysis of unplanned readmission outcome association with procedure type, patient demographics, patient comorbidities, preoperative lab values, operative variables, and postoperative complications was performed using the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or univariate logistic regression where appropriate. Variables with significance of p ≤ 0.20 in the univariate analyses were then entered into a multivariate analysis via binary logistic regression and were considered independently significant when p ≤ 0.05. As a secondary analysis, we applied a Bonferroni correction to the univariate analysis to correct for the higher risk of Type I error due to the use of over 100 independent variables. In this case, only variables with p ≤ 0.002 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate analysis (the αcorrected value for reaching significance in the Bonferroni correction is calculated by dividing the original α value—in our case, 0.2—by the number of independent variables in the analysis). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed for multivariate regression model validation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp.).

Results

A total of 9799 cases met our inclusion criteria, 1098 (11.2%) of which had an unplanned readmission within 30 days. An additional 166 readmissions were planned, making a total of 1264 postoperative readmissions within 30 days. The average time to unplanned readmission after the primary procedure was 14.04 ± 7.74 days (mean ± SD).

Procedures with the highest unplanned readmission rates included replacement or irrigation of ventricular catheter (CPT code 62225, commonly used to describe revision of the proximal catheter of a shunt system, 19.7% readmitted), replacement or revision of CSF shunt (CPT code 62230, used to describe revision of a valve or distal catheter in a shunt system, 16.0% readmitted), MMC repair > 5 cm diameter (CPT code 63706, 15.4% readmitted), creation of CSF shunt (CPT code 62223, 14.1% readmitted), and craniectomy for excision of infratentorial brain tumor (CPT code 61518, 13.9% readmitted). Mortality for 3 of these procedures (MMC repair, shunt placement, and infratentorial tumor excision) was greater than the mortality for the general pediatric neurosurgical population in this study. All but 1 of the 5 procedures with the highest readmission rates were relatively common, with each of the 4 accounting for more than 5% of the total procedures performed (MMC repair > 5 cm accounted for only 1.3% of all procedures). The highest rates of unplanned readmission by procedure are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Highest 30-day unplanned readmission rates by individual procedure.

| CPT | Procedure Description | N | %† | Unplanned Readmission, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62225 | Replacement/irrigation, ventricular catheter | 867 | 8.8 | 19.7 |

| 62230 | Replacement or revision of CSF shunt | 1521 | 15.5 | 16.0 |

| 63706 | Repair of MMC > 5 cm diameter | 123 | 1.3 | 15.4 |

| 62223 | CSF shunt creation | 1072 | 10.9 | 14.1 |

| 61518 | Craniectomy for infratentorial tumor excision | 561 | 5.7 | 13.9 |

CPT = Current procedural terminology, CSF = cerebrospinal fluid, MMC = myelomeningocele.

Percent of all procedures

Rates of unplanned readmission varied significantly according to procedural category (as defined by lists in Fig. 1), ranging from 1.0% for skin lesion procedures to 16.8% for shunt revision, removal, and irrigation procedures. Two procedure categories showed no significant difference in the rate of unplanned readmission compared with all other procedures: craniotomy for neoplasm and other (primarily baclofen pump placement procedures). Procedure category associations with unplanned readmission can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Procedure category association with unplanned readmission via univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using binary logistic regression and chi-square test. Complete procedure categorization, including CPT codes within each category, may be seen in Figure 1.

| Procedure Category | Percent Readmitted | Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | No Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | Crude OR‡ | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shunt/ventricular catheter, revision/removal/irrigation | 16.8 | 471 (42.9) | 2327 (26.7) | 2.058 | 1.809–2.340 | <0.001 |

| Myelomeningocele repair | 14.4 | 34 (3.1) | 202 (2.3) | 1.344 | 0.930–1.944 | 0.117 |

| Shunt/ventricular catheter, placement | 13.4 | 187 (17.0) | 1205 (13.8) | 1.277 | 1.079–1.512 | 0.005 |

| Craniotomy, neoplasm | 11.8 | 157 (14.3) | 1169 (13.4) | 1.076 | 0.899–1.288 | 0.426 |

| Other* | 10.6 | 36 (3.3) | 303 (3.5) | 0.940 | 0.661–1.335 | 0.793 |

| Craniotomy, Chiari malformation | 7.0 | 79 (7.2) | 1057 (12.1) | 0.561 | 0.442–0.711 | <0.001 |

| Spine | 6.5 | 120 (10.9) | 1734 (19.9) | 0.493 | 0.405–0.600 | <0.001 |

| Craniotomy, craniosynostosis | 2.1 | 13 (1.2) | 605 (7.0) | 0.160 | 0.092–0.279 | <0.001 |

| Skin lesion | 1.0 | 1 (0.1) | 99 (1.1) | 0.079 | 0.011–0.568 | <0.001 |

Unadjusted odds ratio with respect to each variable’s null state; i.e., the odds ratio is in reference to all other procedures not in that individual category.

Primarily baclofen pump placement (82% of procedures in this category).

Some patient characteristics and demographics, including length of hospitalization, prior operation within 30 days of the current procedure, admission through the emergency room, home discharge, and Native American race were significantly different between readmitted and nonreadmitted groups on univariate analysis. No difference was seen for age, neonate status, patient sex, inpatient or outpatient status, white race, African American race, Pacific Islander race, unknown race, or transfer from an outside hospital or rehab facility. A longer hospitalization was a significant protective factor for unplanned readmission via univariate logistic regression (OR = 0.993 per day increase, 95% CI = 0.987–0.999, p = 0.033). Patient demographics and characteristics are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Patient demographic association with unplanned readmission via univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, or univariate logistic regression where appropriate. Continuous variables are expressed as median (25th percentile – 75th percentile).

| Parameter | Unplanned Readmission, | No Unplanned Readmission, | Crude OR‡ | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 5.3 (1.1–12.0) | 5.8 (1.0–11.9) | 1.002 | 0.991–1.013 | 0.781 |

| Neonate, n (%) | 79 (7.2) | 649 (7.5) | 0.962 | 0.755–1.226 | 0.807 |

| Total length of stay (days) | 3 (2–7) | 3 (2–5) | 0.993 | 0.987–0.999 | 0.033 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 593 (54.0) | 4661 (53.6) | 1.018 | 0.897–1.154 | 0.797 |

| Female | 505 (46.0) | 4040 (46.4) | Ref. | ||

| Reported Race, n (%) | 0.183 | ||||

| White | 813 (74.0) | 6391 (73.5) | Ref. | ||

| African American | 149 (13.6) | 1157 (13.3) | 1.012 | 0.841–1.219 | 0.897 |

| Asian | 25 (2.3) | 194 (2.2) | 1.013 | 0.664–1.546 | 0.952 |

| Native American | 12 (1.1) | 45 (0.5) | 2.096 | 1.104–3.979 | 0.024 |

| Pacific Islander | 2 (0.2) | 22 (0.3) | 0.715 | 0.168–3.045 | 0.650 |

| Unknown | 97 (8.8) | 892 (10.3) | 0.855 | 0.685–1.067 | 0.166 |

| Patient Status, n (%) | 0.213 | ||||

| Inpatient | 1038 (94.5) | 8135 (93.5) | Ref. | ||

| Outpatient | 60 (5.5) | 566 (6.5) | 0.831 | 0.632–1.092 | |

| Prior operation within 30 days, n (%) | 62 (5.6) | 348 (4.0) | 1.436 | 1.088–1.896 | 0.013 |

| Concurrent procedure, n (%) | 54 (4.9) | 475 (5.5) | 0.896 | 0.671–1.196 | 0.523 |

| Transfer Status | <0.001 | ||||

| Admitted from home/clinic/doctor’s office | 620 (56.5) | 6117 (70.3) | Ref. | ||

| Admitted through ER | 390 (35.5) | 1852 (21.3) | 2.078 | 1.812–2.383 | <0.001 |

| Transfer from outside hospital or rehab facility | 88 (8.0) | 732 (8.4) | 1.186 | 0.937–1.502 | 0.156 |

| Discharge Destination | |||||

| Home | 1067 (97.2) | 8294 (95.3) | Ref. | ||

| Other (rehab, separate facility, skilled care, unskilled care) | 31 (2.8) | 407 (4.7) | 0.592 | 0.409–0.858 | 0.006 |

ER = Emergency room, Ref. = Reference category.

Unadjusted odds ratio; for categorical variables without an explicitly listed reference category, the odds ratio is in reference to cases in which that variable is not true.

Several patient comorbidities were significantly associated with unplanned readmission on univariate analysis, including the presence of any comorbidity, the presence of any non-CNS comorbidity, pulmonary comorbidity (specific conditions significantly associated with readmission: asthma, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, oxygen supplementation, and structural pulmonary abnormality), gastrointestinal comorbidity (specific condition significantly associated with readmission: esophageal, gastric, or intestinal disease), CNS comorbidity (specific conditions significantly associated with readmission: history of CVA or TBI, CNS tumor, developmental delay, cerebral palsy, seizure disorder, and structural CNS abnormality), steroid use greater than 10 days, chemotherapy within 30 days prior to surgery, radiotherapy within 90 days prior to surgery, open wound, tracheostomy at time of surgery, history of prematurity (specifically, 25–28 weeks gestation), intraventricular hemorrhage, nutritional support, and current or previous malignancy. No difference was observed for obesity, renal comorbidity, cardiac comorbidity, immune disease or immunosuppressant use, bleeding disorder, hematological disorder, gestational period > 28 weeks, SIRS or sepsis within 48 hours prior to surgery, or congenital malformation. Patient comorbidities are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Patient comorbidities associated with unplanned readmission via univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, or logistic regression where appropriate.

| Parameter | Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | No Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | Crude OR‡ | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of any comorbidity | 1069 (97.4) | 7877 (90.5) | 3.856 | 2.648–5.165 | <0.001 |

| Presence of any non-CNS comorbidity | 620 (56.5) | 3821 (43.9) | 1.657 | 1.460–1.880 | <0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI for age) | 145 (13.2) | 1148 (13.2) | 1.001 | 0.832–1.205 | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary comorbidity | 227 (20.7) | 1481 (17.0) | 1.271 | 1.087–1.486 | 0.003 |

| Ventilator dependent | 37 (3.4) | 325 (3.7) | 0.899 | 0.636–1.270 | 0.610 |

| Pneumonia | 2 (0.2) | 20 (0.2) | 0.792 | 0.185–3.393 | 1.000 |

| Asthma | 78 (7.1) | 501 (5.8) | 1.252 | 0.977–1.603 | 0.077 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 1.585 | 0.185–13.583 | 0.510 |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 86 (7.8) | 492 (5.7) | 1.418 | 1.117–1.799 | 0.005 |

| Oxygen support | 72 (6.6) | 421 (4.8) | 1.380 | 1.066–1.787 | 0.019 |

| Structural pulmonary abnormality | 71 (6.5) | 400 (4.6) | 1.435 | 1.106–1.787 | 0.009 |

| GI comorbidity | 222 (20.2) | 1257 (14.4) | 1.501 | 1.280–1.759 | <0.001 |

| Esophageal/gastric/intestinal disease | 218 (19.9) | 1228 (14.1) | 1.508 | 1.285–1.769 | <0.001 |

| Biliary/liver/pancreatic disease | 9 (0.8) | 54 (0.6) | 1.323 | 0.652–2.688 | 0.421 |

| Renal comorbidity | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 1.132 | 0.139–9.211 | 1.000 |

| Renal failure | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.0) | 1.982 | 0.221–17.749 | 0.448 |

| Dialysis | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.0) | 1.982 | 0.221–17.749 | 0.448 |

| CNS comorbidity | 1036 (94.4) | 7606 (87.4) | 2.406 | 1.848–3.132 | <0.001 |

| Coma >24 hours | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| History of CVA or TBI | 95 (8.7) | 534 (6.1) | 1.449 | 1.153–1.819 | 0.002 |

| CNS tumor | 218 (19.9) | 1360 (15.6) | 1.337 | 1.140–1.568 | <0.001 |

| Developmental delay | 371 (33.8) | 2273 (26.1) | 1.443 | 1.262–1.650 | <0.001 |

| Cerebral palsy | 129 (11.7) | 704 (8.1) | 1.512 | 1.239–1.846 | <0.001 |

| Neuromuscular disorder | 112 (10.2) | 840 (9.7) | 1.063 | 0.863–1.309 | 0.552 |

| Seizure disorder | 254 (23.1) | 1324 (15.2) | 3.629 | 2.209–5.961 | <0.001 |

| Structural CNS abnormality | 862 (78.5) | 6342 (72.9) | 1.359 | 1.168–1.581 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac comorbidity | 126 (11.5) | 922 (10.6) | 1.094 | 0.897–1.333 | 0.378 |

| Steroid use* | 138 (12.6) | 678 (7.8) | 1.701 | 1.400–2.067 | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy in 30 days prior to surgery | 33 (3.0) | 109 (1.3) | 2.442 | 1.646–3.642 | <0.001 |

| Radiotherapy in 90 days prior to surgery | 10 (0.9) | 28 (0.3) | 2.847 | 1.379–5.877 | 0.008 |

| Open wound (with or without infection) | 39 (3.6) | 188 (2.2) | 1.668 | 1.174–2.368 | 0.007 |

| Tracheostomy at time of surgery | 32 (2.9) | 145 (1.7) | 1.771 | 1.202–2.611 | 0.005 |

| Immune Disease/immunosuppressant use | 13 (1.2) | 74 (0.9) | 1.397 | 0.772–2.527 | 0.302 |

| Nutritional support (IV or NG tube) | 168 (15.3) | 833 (9.6) | 1.706 | 1.426–2.041 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding disorder | 9 (0.8) | 53 (0.6) | 1.349 | 0.663–2.741 | 0.416 |

| Hematologic disorder | 36 (3.3) | 240 (2.8) | 1.195 | 0.837–1.706 | 0.332 |

| Current or previous malignancy | 191 (17.4) | 1046 (12.1) | 1.541 | 1.302–1.825 | <0.001 |

| History of prematurity | 0.002 | ||||

| Term birth (≥ 37 weeks gestation) | 744 (67.8) | 6167 (70.9) | Ref. | ||

| 33–36 weeks gestation | 97 (8.8) | 732 (8.4) | 1.098 | 0.877–1.376 | 0.414 |

| 29–32 weeks gestation | 50 (4.6) | 378 (4.3) | 1.096 | 0.809–1.487 | 0.554 |

| 25–28 weeks gestation | 110 (10.0) | 593 (6.8) | 1.538 | 1.237–1.911 | <0.001 |

| ≤ 24 weeks gestation | 36 (3.3) | 241 (2.8) | 1.238 | 0.865–1.772 | 0.243 |

| Unknown | 61 (5.6) | 590 (6.8) | 0.857 | 0.651–1.128 | 0.270 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 141 (12.8) | 873 (10.0) | 1.321 | 1.092–1.598 | 0.005 |

| Congenital malformation, any system | 402 (36.6) | 3247 (37.3) | 0.970 | 0.852–1.105 | 0.667 |

| SIRS/Sepsis within 48 hr before surgery | 19 (1.7) | 130 (1.5) | 1.161 | 0.714–1.887 | 0.514 |

CVA = cerebrovascular accident (stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage), BMI = body mass index, GI = gastrointestinal, TBI = traumatic brain injury, IV = intravenous, NG = nasogastric, SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome, NA = not applicable, Ref. = reference categorical variable.

Steroid use is defined as use of oral or parenteral corticosteroid within 30 days prior to the principal procedure or at the time the patient is being considered as a candidate for surgery; does not include short term use, such as a one-time pulse, limited short course, or a taper of less than 10 days.

Unadjusted odds ratio is in reference to the null state for variables without an explicitly defined reference category; i.e., the odds ratio is in reference to cases without the comorbidity listed.

Few preoperative laboratory values were significantly associated with unplanned readmission on univariate analysis; these included hypoalbuminemia and elevated WBC count. No difference was seen for hyponatremia, hypernatremia, elevated WBC count, thrombocytopenia, elevated AST, elevated BUN, abnormal PT, abnormal PTT, or anemia. Preoperative laboratory values are displayed in Table 5. Of note, not all patients had preoperative laboratory values measured.

Table 5.

Preoperative laboratory value association with unplanned readmission via univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using logistic regression and Fisher’s exact test.

| Parameter (% w/lab value)† | Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | No Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | Crude OR‡ | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoalbuminemia (19.7) | 51 (4.6) | 320 (3.7) | 1.276 | 0.943–1.726 | 0.130 |

| Hyponatremia (58.0) | 42 (3.8) | 280 (3.2) | 1.196 | 0.859–1.665 | 0.281 |

| Hypernatremia (58.0) | 17 (1.5) | 114 (1.3) | 1.185 | 0.709–1.980 | 0.486 |

| Elevated WBC (67.4) | 78 (7.1) | 496 (5.7) | 1.265 | 0.988–1.620 | 0.066 |

| Thrombocytopenia (67.0) | 57 (5.2) | 398 (4.6) | 1.142 | 0.859–1.519 | 0.361 |

| Elevated AST (18.1) | 14 (1.3) | 115 (1.3) | 0.964 | 0.552–1.685 | 1.000 |

| Elevated BUN (55.2) | 5 (0.5) | 51 (0.6) | 0.776 | 0.309–1.948 | 0.831 |

| Abnormal PT (36.4) | 53 (4.8) | 370 (4.3) | 1.142 | 0.850–1.534 | 0.386 |

| Abnormal PTT (37.5) | 65 (5.9) | 516 (5.9) | 0.998 | 0.765–1.302 | 1.000 |

| Anemia (68.2) | 89 (8.1) | 618 (7.1) | 1.154 | 0.915–1.454 | 0.239 |

WBC = white blood cell, AST = aspartate transaminase, BUN = blood urea nitrogen, PT = prothrombin time, PTT = partial thromboplastin time.

Not all patients have listed preoperative lab measurements recorded; percentage is % of total patient cohort with preoperative lab measurements, normal or abnormal.

Unadjusted odds ratio is in reference to null state; i.e., in relation to cases in which the given lab value is normal.

Operative variables significantly associated with unplanned readmission on univariate analysis included a shorter operation, triage status, ASA classification, and perioperative blood transfusion (protective). No difference was observed for wound classification overall (p = 0.310); however, dirty and/or infected wound status was entered into the multivariate analysis (p < 0.2). Although a longer operation was protective for readmission on univariate logistic regression (OR = 0.960 per hour increase, 95% CI = 0.925–0.995, p = 0.027), a longer operation emerged as an independently significant risk factor for readmission on multivariate analysis (OR = 1.059 per hour increase, 95% CI = 1.006–1.114, p = 0.029). The protective effect of a longer operation (a 4% decrease in readmission risk per hour increase in operative time) diminished when accounting for all variables in the multivariate analysis and actually became a risk factor (a 5% increase in readmission risk per hour increase in operative time). This was expected, as longer operations are typically performed in patients with more severe underlying conditions and are more likely to result in postoperative complications. Operative variable analysis is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Operative variable association with unplanned readmission via univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, or univariate logistic regression where appropriate. Continuous variables expressed as median (25th percentile–75th percentile).

| Parameter | Unplanned Readmission | No Unplanned Readmission | Crude OR‡ | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of Operation (minutes) | 69 (41–139) | 82 (47–159) | 0.960 | 0.925–0.995 | 0.027 |

| Triage, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Elective | 685 (62.4) | 6551 (75.3) | Ref. | ||

| Emergent | 248 (22.6) | 1198 (13.8) | 1.980 | 1.691–2.318 | <0.001 |

| Urgent | 165 (15.0) | 952 (10.9) | 1.658 | 1.380–1.991 | <0.001 |

| ASA Class, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 20 (1.8) | 476 (5.5) | Ref. | ||

| II | 334 (30.4) | 3438 (39.5) | 2.312 | 1.458–3.667 | <0.001 |

| III | 692 (63.0) | 4411 (50.7) | 3.734 | 2.370–5.882 | <0.001 |

| IV | 48 (4.4) | 346 (4.0) | 3.302 | 1.925–5.664 | <0.001 |

| V | 0 (0.0) | 12 (0.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| Unknown | 4 (0.4) | 18 (0.2) | 5.289 | 1.638–17.077 | 0.005 |

| Perioperative blood transfusion, n (%) | 70 (6.4) | 667 (7.7) | 0.820 | 0.636–1.058 | 0.129 |

| Wound Classification, n (%) | 0.310 | ||||

| Clean | 1044 (95.1) | 8362 (96.1) | Ref. | ||

| Clean-contaminated | 30 (2.7) | 206 (2.4) | 1.166 | 0.791–1.720 | 0.437 |

| Contaminated | 9 (0.8) | 57 (0.7) | 1.265 | 0.624–2.562 | 0.514 |

| Dirty and/or infected | 15 (1.4) | 76 (0.9) | 1.581 | 0.905–2.761 | 0.107 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists, NA = not applicable, Ref. = reference category.

Unadjusted odds ratio; for categorical variables without an explicit reference category, odds ratios are in reference to cases in which the variable was not true (null state).

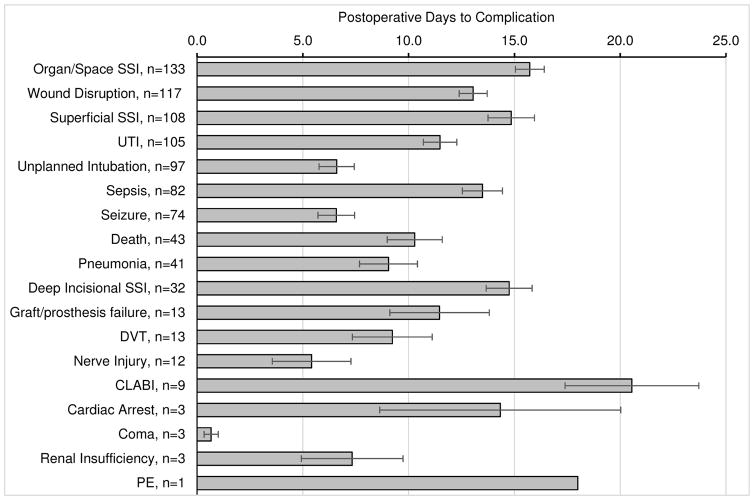

Postoperative complications (systemic infections or SSIs, seizure, coma, unplanned reintubation, nerve injury, organ failure, graft failure, venous thromboembolism) occurred in 1237 (12.6%) of cases and were the strongest predictors of unplanned readmission. Data on days to postoperative complications are displayed in Fig. 2. Complications significantly associated with unplanned readmission on univariate analysis included any complication, any infection (superficial SSI, deep SSI, organ/space SSI, sepsis, UTI, pneumonia, central line–associated bloodstream infection), wound disruption, unplanned intubation, CVA, seizure, graft or prosthesis failure, and DVT. No differences were seen for renal insufficiency, acute renal failure, coma > 24 hours, peripheral nerve injury, PE, or cardiac arrest (some events were not statistically testable due to a prohibitively low number of events). Postoperative complications analysis is displayed in Table 7.

Fig. 2.

Postoperative days to complication data (expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean with n = number of events per complication). Average time to unplanned readmission was 14.04 ± 7.74 days postoperatively (mean ± standard deviation). CLABI = central line–associated bloodstream infection.

Table 7.

Postoperative complications associated with unplanned readmission via univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed via binary logistic regression and Fisher’s exact test.

| Complication | Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | No Unplanned Readmission, n (%) | Crude OR‡ | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any complication* | 312 (28.4) | 404 (4.6) | 3.356 | 2.895–3.890 | <0.001 |

| Any Infection | 219 (19.9) | 205 (2.4) | 10.326 | 8.431–12.646 | <0.001 |

| Superficial SSI | 52 (4.7) | 56 (0.6) | 7.674 | 5.233–11.255 | <0.001 |

| Deep SSI | 23 (2.1) | 9 (0.1) | 20.833 | 9.524–45.455 | <0.001 |

| Organ/space SSI | 96 (8.7) | 37 (0.4) | 22.435 | 15.268–32.966 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 52 (4.7) | 30 (0.3) | 14.369 | 9.126–22.623 | <0.001 |

| UTI | 35 (3.2) | 70 (0.8) | 4.060 | 2.692–6.122 | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 15 (1.4) | 26 (0.3) | 4.621 | 2.440–8.752 | <0.001 |

| Central line bloodstream infection | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.1) | 3.698 | 0.991–15.873 | 0.070 |

| Wound dehiscence | 74 (6.7) | 43 (0.5) | 14.551 | 9.937–21.306 | <0.001 |

| Unplanned intubation | 20 (1.8) | 77 (0.9) | 2.078 | 1.265–3.412 | 0.006 |

| Renal insufficiency | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Acute renal failure | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Coma > 24 hrs | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| CVA/intracranial hemorrhage | 11 (1.0) | 31 (0.4) | 2.830 | 1.419–5.647 | 0.005 |

| Seizure | 23 (2.1) | 51 (0.6) | 3.629 | 2.209–5.961 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral nerve injury | 1 (0.1) | 11 (0.1) | 1.389 | 0.179–10.766 | 1.000 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 1.585 | 0.185–13.514 | 0.510 |

| Graft/prosthesis failure | 9 (0.8) | 4 (0.0) | 17.857 | 5.525–58.824 | <0.001 |

| Deep Venous Thrombosis | 5 (0.5) | 8 (0.1) | 4.971 | 1.623–15.221 | 0.010 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

Does not include variables not coded within NSQIP (e.g., shunt failure) or perioperative/postoperative blood transfusion requirement.

SSI = surgical site infection, UTI = urinary tract infection, CVA = cerebrovascular accident, NA = not applicable.

Unadjusted odds ratio with respect to each variable’s null state (i.e., cases in which the given complication was not present).

For shunt operations with the highest readmission rates (CPT codes 62223, 62230, 62225), the overall 30-day unplanned readmission rate was 16.3%. Within these 3 shunt operations, the most common reasons for readmission were shunt failure or mechanical device complication (ICD-9 code 996.2, 31.2% of readmissions), need for another shunt procedure (CPT codes 62223–62258, 17.9% of readmissions), and organ or space SSI (8.5% of readmissions). Other less common reasons for readmission among the 3 shunt operations with the highest readmission rate included headache (2.5%), wound disruption (2.1%), and seizure (2.0%). Similarly, in patients who underwent craniectomy for excision of brain infratentorial tumor (CPT code 61518, 30-day unplanned readmission rate of 13.9%), the most common reasons for readmission included hydrocephalus (19.2% of readmissions), wound disruption (11.5% of readmissions), and organ or space SSI (7.7% of readmissions).

Results from the multivariate logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 8. Numerous variables emerged as independently significant risk factors, including (in order of decreasing odds ratio): deep incisional SSI; organ or space SSI; wound disruption; superficial incisional SSI; graft or prosthesis failure; postoperative pneumonia; postoperative UTI; postoperative sepsis; postoperative seizure; Native American race; shunt or ventricular catheter removal, replacement, or irrigation procedure; shunt or ventricular catheter placement procedure; MMC repair procedure; presence of any comorbidity; home discharge; oxygen supplementation; steroid use > 10 days; nutritional support; prior operation within 30 days of the current procedure; transfer from emergency room; preexisting seizure disorder; and longer operative time. Several factors emerged as independently significant protective factors for readmission, including longer hospital stay, spine procedure, and craniotomy for craniosynostosis procedure. Increasing length of stay proved to be a significant protective factor (OR = 0.956 per day increase, 95% CI 0.946–0.966, p < 0.001); however, this variable is not included in Table 8 because of the decreasing time window in which readmission can occur as the length of stay increases. Variables that did not remain in the model when applying a Bonferroni correction for multiple measures were Native American race, oxygen supplementation, home discharge, prior operation within 30 days of index procedure, longer operative time, MMC repair procedures, and shunt placement procedures (marked with asterisks in Table 8).

Table 8.

Logistic regression analysis of variables independently associated with unplanned readmission. Variables were included for analysis when p ≤ 0.2 by univariate Fisher’s exact, chi-square, or univariate logistic regression tests. Variables were considered independently significant when p ≤ 0.05 in multivariate logistic regression.

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep incisional SSI | 25.547 | 10.229–63.373 | <0.001 |

| Organ/space SSI | 19.156 | 11.618–31.585 | <0.001 |

| Wound disruption | 17.582 | 10.750–28.756 | <0.001 |

| Superficial incisional SSI | 12.151 | 7.783–18.973 | <0.001 |

| Graft/prosthesis failure | 11.074 | 2.882–42.548 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 4.294 | 2.045–9.017 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative UTI | 4.262 | 2.598–6.992 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative sepsis | 2.616 | 1.321–5.181 | 0.006 |

| Postoperative seizure | 2.532 | 1.398–4.587 | 0.002 |

| Native American race* | 2.363 | 1.149–4.861 | 0.019 |

| Shunt revision/removal/irrigation procedure | 2.283 | 1.679–3.103 | <0.001 |

| Shunt placement procedure* | 2.128 | 1.542–2.937 | <0.001 |

| MMC procedure* | 1.979 | 1.066–3.675 | 0.031 |

| Presence of any comorbidity | 1.943 | 1.086–3.478 | 0.025 |

| Home discharge* | 1.885 | 1.208–2.942 | 0.005 |

| Oxygen supplementation* | 1.645 | 1.128–2.399 | 0.010 |

| Steroid use > 10 days | 1.411 | 1.087–1.831 | 0.010 |

| Nutritional support (IV or NG tube) | 1.403 | 1.088–1.809 | 0.009 |

| Prior operation within 30 days of index procedure* | 1.378 | 1.001–1.897 | 0.049 |

| Transfer from ER | 1.273 | 1.046–1.549 | 0.016 |

| Preexisting seizure disorder | 1.250 | 1.034–1.510 | 0.021 |

| Operative time (per hour increase)* | 1.059 | 1.006–1.114 | 0.029 |

| Spine procedure | 0.703 | 0.503–0.984 | 0.040 |

| Craniotomy for craniosynostosis | 0.291 | 0.151–0.560 | <0.001 |

SSI = surgical site infection, UTI = urinary tract infection, MMC = myelomeningocele, ER = emergency room, IV = intravenous, NG = nasogastric, CI = confidence interval.

Indicates variables excluded from corrected Bonferroni multivariate logistic regression model due to p-value failing to reach αcorrected ≤ 0.002 by univariate analysis.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis for validation of the logistic regression model yielded a C-statistic, or area under the curve, of 0.759 (95% CI 0.744–0.775, p < 0.001). An area under the curve ≥ 0.7 by ROC analysis indicates an acceptable multivariate logistic regression model with significantly greater predictive ability than chance alone.

Discussion

We have identified rates of unplanned readmission as well as independent risk factors for readmission in a national pediatric neurosurgical population. To our knowledge, this is the first study in which the NSQIP database has been used to examine rates and risk factors for readmission after pediatric neurosurgery. While previous studies have reported return to system after pediatric neurosurgery at single institutions9,21,26 or after pediatric shunt surgery,20 the statistical power of a large national patient sample may provide a more representative picture of readmission outcomes for general pediatric neurosurgical procedures.

Complications

Postoperative infection, particularly SSI, was the strongest predictor of readmission. This observation is not surprising given that SSI is not uncommon and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly if not caught and treated early. Surgical site infection has been shown to cause up to 70% of reoperations after pediatric spine surgery17 and is one of the strongest predictors of readmission after pediatric plastic surgery.23 However, the relatively high rate of SSI and readmissions related to SSI could indicate a need to continue to study and improve preventative measures before, during, and after surgery (prophylactic antibiotic use, close monitoring of sterile technique, postoperative wound monitoring or cleaning) to prevent occurrences of SSI and SSI-related return to system. Additionally, wound disruption was a common reason for readmission and was independently associated with readmission.

Shunt failure was the most common ICD-9 diagnosis on readmission. In pediatric neurosurgery, shunt failure is a common and oftentimes unpreventable phenomenon, occurring in approximately 12% of pediatric shunt procedures within 30 days or less11 and in up to 46% of procedures when following failure rates for up to 1 year.6,10 The 30-day readmission rate for shunt operations (15.7%) in this study is substantially similar to that published in previous work20 and may be useful as a benchmark for future studies aimed at lowering adverse shunt surgery events. As expected, the majority of readmissions after a CSF shunting procedure are related to recurrent shunt difficulties. Aside from shunt failure, however, infection-related readmissions (organ or space SSI and wound disruption) were the most common reasons for readmission among the shunt procedures with the highest readmission rates. These results indicate that measures to prevent SSI and wound disruption could help to reduce unplanned readmission after pediatric neurosurgery.

Readmission occurred, on average, approximately 2 weeks postoperatively. Given that postoperative infections (systemic or SSI) were the strongest predictors of readmission, it is expected that the time course to readmission would follow a course similar to the time required for common infection complications to develop. Again, this finding highlights the need for improved postoperative wound monitoring and better operative wound management to prevent unplanned readmission. The present study supports the notion that ongoing efforts to minimize SSIs in pediatric neurosurgery have the greatest potential to reduce readmission rates.

Patient-Related Factors

The percentage of patients with any comorbidity was 91.3%, and 45.3% had any non-CNS comorbidity. The high comorbidity rate in pediatric neurosurgery relative to that in other specialties could be one possible cause of the higher readmission, morbidity, and mortality rates observed in this specialty relative to the rates in others.4 Comorbidities independently associated with readmission included the presence of any comorbidity, steroid use, oxygen support, nutritional support, and seizure disorder. Chronic steroid use has not been well studied in pediatric populations, although some institutions have initiated steroid avoidance protocols before renal transplantation surgery.15 Nutritional support has been indicated as a risk factor for readmission after pediatric cardiac surgery16 and cleft palate repair.19 The comorbid conditions that have a strong association with unplanned readmission could be used as preoperative risk stratification variables. Patients who are considered high-risk based on these findings may benefit from more careful discharge planning or increased outpatient attention in an effort to prevent readmission.

Native American race emerged as an independently significant risk factor for readmission. Native American race has been reported as a risk factor for readmission after orthopedic surgery12 and following sepsis,8 although its association with readmission after pediatric neurosurgical procedures has not been observed to our knowledge. While a plausible explanation for this is not apparent from these data, it is important to note disparities such as this as an area for future study. An important caveat to this observation, however, is that Native American patients make up a very small proportion of the NSQIP sample. Therefore, observations about this population are potentially subject to error given the magnified effect of small numbers of readmissions in a population with a small denominator. Furthermore, we are unable to determine socioeconomic or geographical data from the NSQIP-P data set, both of which may contribute to demographic differences in readmission rates.

Procedure and Hospital-Related Factors

We observed a higher rate of readmission among procedures related to CSF shunts, MMC repair, and craniotomy for infratentorial tumor excision. These findings are perhaps unsurprising as these procedures are typically performed in patients with multiple comorbidities and often require close follow-up for revisions. Previous studies have shown high rates of return to system in pediatric shunt surgery, with readmission rates similar to those reported here.20 Interestingly, 4 of the 5 procedures with the highest readmission rates composed over 40% of all procedures in the NSQIP-P neurosurgery cohort. Of the procedures with the highest readmission rates, operation for MMC repair was the least frequently performed (1.3% of all procedures), and its high readmission rate is expected given the myriad comorbidities that often occur in patients with MMC.5

Emergent or urgent triage status and admission through the emergency department were significant predictors of unplanned readmission on univariate analysis, although emergent or urgent triage was not a predictor on multivariate analysis. These findings are not surprising, yet they may aid in patient risk stratification when ascertaining patient readmission risk preoperatively.

Interestingly, a longer hospital stay was a significant protective factor in multivariate regression. This observation lends credence to the idea that for health care providers the goals of decreased hospital stay and decreased readmission may be competing.14 Efforts to decrease hospital length of stay may lead to increased readmission and vice versa. However, our data capture readmission within 30 days of the primary procedure, not from discharge; therefore, it follows that a longer hospitalization decreases the chance of readmission within 30 days because of a smaller window of time in which readmission (as defined within 30 days of the primary procedure) can occur.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the NSQIP-P database is limited by the type of data provided by the participating institutions and by the NSQIP categorical variables. Although the NSQIP-P is a national database, the case sample is not necessarily nationally representative. Trauma cases are not included in the database. Certain procedures (for example, CPT code 62201: endoscopic third ventriculostomy with choroid plexus cauterization) are not included either. The severity of categorically coded conditions cannot be ascertained, limiting our ability to associate certain patient conditions with readmission outcomes. Some comorbidities (for example, cardiac risk factors) are insufficiently granular and do not distinguish between different comorbidity subtypes (for example, atrial septal defect vs hypertrophic cardiomyopathy). Facility identifiers are not included in the NSQIP, which prevents analysis of facility outliers with substantially higher or lower rates of readmission. As is the case with many patient databases, preventative preoperative measures are not tracked, probably resulting in overestimation of risk factors. Furthermore, not all patients had their preoperative laboratory values measured; albumin and AST had missing value rates of greater than 80%, limiting our ability to interpret statistical analysis of the differences in preoperative laboratory values between groups. Data on exact reason (that is, ICD-9 diagnosis) for readmission in the NSQIP are not always reported or entirely clear. Of the 1098 unplanned readmissions, 746 (67.9%) were directly related to the primary procedure. Of the remaining 32.1% of readmissions unrelated to the primary procedure, the NSQIP data abstractors may not have captured the reason for readmission, which could limit the thoroughness of our readmission reason results. Using readmission as an outcome measure has particular caveats as higher or lower rates of readmission alone may not necessarily indicate poorer or better surgical care quality.

Finally, the large number of variables analyzed increases the risk of Type I error, or false-positive findings. The Bonferroni method of multiple measures correction is very conservative, greatly decreasing the risk of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis (Type I error), but at the cost of increasing the risk of incorrectly accepting the null hypothesis (Type II error). In most multivariate logistic regression analyses, a higher α is accepted when selecting variables to include in the model in an effort to avoid inappropriately excluding important variables. Thus, we present the corrected model for reference but base our discussion on the uncorrected model.

Despite these limitations, this study may aid surgeons in identifying procedures and patient risk factors that predispose patients to a higher risk of readmission after pediatric neurosurgery. Patients undergoing longer procedures or procedures related to CSF shunting, MMC repair, or craniectomy for infratentorial brain tumor excision are at greater risk for readmission, especially if they are transferred from the emergency department. Patients undergoing spine procedures or craniotomy for craniosynostosis have a lower risk of readmission compared with those undergoing other procedures. Patients who are Native American, have any preexisting comorbidity, have undergone an operation in the previous 30 days, or have a seizure disorder should be considered at greater risk for unplanned readmission. In addition, patients who require oxygen supplementation, nutritional support, or long-term steroids should also be considered to have a greater risk for readmission. Finally, patients who experience postoperative infection (SSI or systemic infection) should be considered at the greatest risk for readmission. These data may also prove useful for family and patient counseling prior to neurosurgical operations.

Conclusions

This is the first study to use the pediatric NSQIP data to examine hospital readmission after shunt and nonshunt neurosurgical procedures in pediatric patients. Hospital readmission rates in this study are similar to previously published rates from other sources. Unsurprisingly, SSIs and wound-related complications are some of the most important contributors to hospital readmission; therefore, efforts directed at reducing infection may have the greatest impact on readmission.

There is significant readmission rate variability among different procedure categories. Procedures with the highest rates of unplanned readmission were CSF shunt revision or removal, MMC repair, CSF shunt placement, and craniectomy for infratentorial neoplasm. Procedures with the lowest unplanned readmission rates were spine procedures, craniosynostosis craniotomies, and skin lesion procedures.

We have identified many patient-related factors such as long-term steroid use, the need for nutritional support, and oxygen dependency. While these are not modifiable risk factors, they can be useful in identifying patients at high risk for readmission who could benefit from discharge planning or direct efforts to facilitate safe hospital discharge without readmission.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- ACS

American College of Surgeons

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CPT

current procedural terminology

- CVA

cerebrovascular accident

- DVT

deep venous thrombosis

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- MMC

myelomeningocele

- NSQIP-P

National Quality Improvement Program–Pediatric

- PE

pulmonary embolism

- PT

prothrombin time

- PTT

partial thromboplastin time

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SIRS

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- SSI

surgical site infection

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- WBC

white blood cell

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: all authors. Acquisition of data: Sherrod. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting the article: all authors. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Rocque. Statistical analysis: Rocque, Sherrod. Study supervision: Rocque.

References

- 1.American College of Surgeons. User Guide for the 2013 ACS NSQIP Pediatric Participant Use Data File. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2014. [Accessed February 23, 2016]. ( https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/nsqip/peds_puf_userguide_2013.ashx) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011;305:504–505. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Feudtner C, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305:682–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruny JL, Hall BL, Barnhart DC, Billmire DF, Dias MS, Dillon PW, et al. American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Pediatric: a beta phase report. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulbul A, Can E, Bulbul LG, Cömert S, Nuhoglu A. Clinical characteristics of neonatal meningomyelocele cases and effect of operation time on mortality and morbidity. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2010;46:199–204. doi: 10.1159/000317259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldarelli M, Di Rocco C, La Marca F. Shunt complications in the first postoperative year in children with meningomyelocele. Childs Nerv Syst. 1996;12:748–754. doi: 10.1007/BF00261592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; revisions to payment policies under the physician fee schedule, clinical laboratory fee schedule, access to identifiable data for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation models & other revisions to Part B for CY 2015. Fed Regist. 2014;79:67547–68092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang DW, Tseng CH, Shapiro MF. Rehospitalizations following sepsis: common and costly. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:2085–2093. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chern JJ, Bookland M, Tejedor-Sojo J, Riley J, Shoja MM, Tubbs RS, et al. Return to system within 30 days of discharge following pediatric shunt surgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;13:525–531. doi: 10.3171/2014.2.PEDS13493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochrane DD, Kestle JR. The influence of surgical operative experience on the duration of first ventriculoperitoneal shunt function and infection. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;38:295–301. doi: 10.1159/000070413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen ME, Liu Y, Ko CY, Hall BL. Improved surgical outcomes for ACS NSQIP hospitals over time: evaluation of hospital cohorts with up to 8 years of participation. Ann Surg. 2009;263:267–273. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dailey EA, Cizik A, Kasten J, Chapman JR, Lee MJ. Risk factors for readmission of orthopaedic surgical patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1012–1019. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, Goodman DM, Slonim AD, Sharma V, et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:286–293. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Public reporting of discharge planning and rates of readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2637–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0904859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lightner A, Concepcion W, Grimm P. Steroid avoidance in renal transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2011;16:477–482. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32834a8c74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackie AS, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, Mayer JE, Erickson LC. Risk factors for readmission after neonatal cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1972–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeod L, Flynn J, Erickson M, Miller N, Keren R, Dormans J. Variation in 60-day readmission for surgical-site infections (SSIs) and reoperation following spinal fusion operations for neuromuscular scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015 doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000495. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, Hall BL, Cohen ME, Williams MV, et al. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313:483–495. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paine KM, Paliga JT, Tahiri Y, Fischer JP, Wes AM, Wink JD, et al. An assessment of 30-Day complications in primary cleft palate repair: a review of the 2012 ACS NSQIP Pediatric. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2014;134(4 Suppl 1):9. doi: 10.1597/14-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piatt JH., Jr Thirty-day outcomes of cerebrospinal fluid shunt surgery: data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program-Pediatrics. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;14:179–183. doi: 10.3171/2014.5.PEDS1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarda S, Bookland M, Chu J, Shoja MM, Miller MP, Reisner SB, et al. Return to system within 30 days of discharge following pediatric non-shunt surgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;14:654–661. doi: 10.3171/2014.8.PEDS14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sellers MM, Merkow RP, Halverson A, Hinami K, Kelz RR, Bentrem DJ, et al. Validation of new readmission data in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tahiri Y, Fischer JP, Wink JD, Paine KM, Paliga JT, Bartlett SP, et al. Analysis of risk factors associated with 30-day readmissions following pediatric plastic surgery: a review of 5376 procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:521–529. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board. Frequently asked questions: Is IRB review required for use of public datasets? [Accessed February 23, 2016];UAB Research. ( http://www.uab.edu/research/administration/offices/IRB/FAQs/Pages/default.aspx?Topic=Datasets)

- 25.Weiss A, Anderson JE, Chang DC. Comparing the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program with the Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:815–816. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrubel DM, Riemenschneider KJ, Braender C, Miller BA, Hirsh DA, Reisner A, et al. Return to system within 30 days of pediatric neurosurgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;13:216–221. doi: 10.3171/2013.10.PEDS13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.