Abstract

The efficient delivery of foreign nucleic acids (transfection) into cells is a critical tool for fundamental biomedical research and a pillar of several biotechnology industries. There are currently three main strategies for transfection including reagent, instrument, and viral based methods. Each technology has significantly advanced cell transfection; however, reagent based methods have captured the majority of the transfection market due to their relatively low cost and ease of use. This general method relies on the efficient packaging of a reagent with nucleic acids to form a stable complex that is subsequently associated and delivered to cells via nonspecific electrostatic targeting. Reagent transfection methods generally use various polyamine cationic type molecules to condense with negatively charged nucleic acids into a highly positively charged complex, which is subsequently delivered to negatively charged cells in culture for association, internalization, release, and expression. Although this appears to be a straightforward procedure, there are several major issues including toxicity, low efficiency, sorting of viable transfected from nontransfected cells, and limited scope of transfectable cell types. Herein, we report a new strategy (SnapFect) for nucleic acid transfection to cells that does not rely on electrostatic interactions but instead uses an integrated approach combining bio-orthogonal liposome fusion, click chemistry, and cell surface engineering. We show that a target cell population is rapidly and efficiently engineered to present a bio-orthogonal functional group on its cell surface through nanoparticle liposome delivery and fusion. A complementary bio-orthogonal nucleic acid complex is then formed and delivered to which chemoselective click chemistry induced transfection occurs to the primed cell. This new strategy requires minimal time, steps, and reagents and leads to superior transfection results for a broad range of cell types. Moreover the transfection is efficient with high cell viability and does not require a postsorting step to separate transfected from nontransfected cells in the cell population. We also show for the first time a precision transfection strategy where a single cell type in a coculture is target transfected via bio-orthogonal click chemistry.

Short abstract

We report a combined cell surface engineering and bio-orthogonal click chemistry strategy to precisely deliver nucleic acids to cells with high viability and efficiency.

Introduction

The ability to efficiently deliver nucleic acids into cells (transfection) is of central importance to advance human health.1 Transfection has revolutionized fundamental studies of cell biology, biotechnology, agriculture, microbiology, genetics, cancer, disease, medicines, and biomedical research.2−7 Cutting edge research fields and medicines rely on the efficient delivery of nucleic acids into a range of cell types for applications that span gene editing, therapeutics, fundamental cell biology studies, vaccine development, human and plant biotechnology, and scaling protein production among many other life science based applications.8−11 Although transfection is of central importance and one of the most vital tools in all of biological research, most cell types are not easily transfected with foreign nucleic acids due to a variety of nucleic acid stability, delivery, and host cell defense mechanisms. Furthermore, the ability to transfect cells with nucleic acids in vitro and in vivo is not straightforward due to rapid nucleic acid degradation in serum containing media or in vivo conditions. As transfection is an initial step in many biological studies, poor cell transfection results in tremendous waste in time spent in multiple rounds of transfection to improve cell count and money spent in extra labor and reagents. Due to its vital importance, reagents that promote transfection are one of the most essential tools in life science research and product lines in the life science commercial market estimated at over $1.5 billion/year.12

The key challenge for efficient and broad scope of nucleic acid to cell transfection is at the molecular level: how to deliver negatively charged nucleic acids to negatively charged cells at physiological conditions in serum, with the least number of steps, while ensuring high viability and efficiency and no postsorting of transfected and nontransfected cells. To address these requirements, a range of delivery methods, instrument methods, and viral methods have been developed for transfection, but each suffers from various drawbacks related to cost, viability, and efficiency.13,14

The overwhelming strategy to deliver nucleic acids to cells is based on a transfection reagent binding to nucleic acids, which is then delivered to cells via adhesion to the cell surface. There are three main steps in nucleic acid delivery to cells: (1) (Packaging) Reagent forming a complex with nucleic acids. (2) (Delivery) Adhesion of the nucleic acid/complex to cell surfaces followed by endocytosis. (3) (Release) Lysosomal escape of the nucleic acids within cells. To be useful to the broad research community, these processes must be designed with minimal number of steps, with high viability and efficiency, and in the presence of serum in cell culture. Current strategies and products focus on delivering as much nucleic acid as possible via electrostatic complexation of nucleic acids with excess positive charge polyamine polymers or small molecules. The highly cationic nucleic acid complex is then added to cells in culture, where serum proteins rapidly absorb and degrade a significant fraction of the complex and the remaining active complex fraction then associates electrostatically with anionic cell surfaces. The nucleic acid complex undergoes endocytosis, and a small functional fraction escapes the lysosome to be expressed (transfect) in the cell. Although these techniques have revolutionized biotechnology, biomedical research, and human health, there remain significant limitations with this overall transfection strategy: (1) highly toxic to cells; (2) low viability of remaining cells; (3) low overall expression in cell population; (4) unable to specifically transfect cells in cocultures; (5) not general for a broad range of cell types; (6) poor rates of transfection in primary cells or stem cells; (7) must include a separate sorting step to separate transfected versus nontransfected cells for expansion.

To significantly advance transfection technology and cell biologic research, new methods that look for alternatives to electrostatics may broaden the scope of cell transfection. New strategies to associate and deliver nucleic acids to cell surfaces, which do not use electrostatics but rather use selective click chemistry, may lead to remarkable new ways for cell transfection to foster new cell studies, precise in vivo transfection, and manipulation of cell behavior. The new strategy must overlay with a transfection procedure that has to feature several characteristics: (1) straightforward with few manipulation steps; (2) no complex instrumentation; (3) high viability; (4) high efficiency; (5) no post-cell-sorting step; (6) precision cell transfection in cocultures; (7) inexpensive.

Herein, we introduce a new general strategy to deliver nucleic acids to cells. The method is based on a cell surface engineering and bio-orthogonal strategy to package and deliver nucleic acids to cells using rapid artificial surface labeling and targeting. This method generates a nucleic acid complex with a bio-orthogonal group and a cell surface engineered to present the complementary bio-orthogonal group for adhesion and delivery. This method is based on oxime click chemistry and does not rely on nonspecific electrostatic interactions between the nucleic acid complex and the cell. The methodology we term SnapFect has these characteristics: (1) mild; (2) efficient; (3) high viability; (4) no post-cell-sorting steps; (5) precision targeting of specific cells in coculture; (6) compatible with complex media; (7) transient cell surface engineering; (8) no alteration in cell behavior due to mild liposomal and bio-orthogonal chemistry; (9) minimal two step protocol; (10) compatible with siRNA, CRISPR, and microfluidic technology.

Liposome fusion has been used as a strategy for the delivery of chemical and biological cargoes into mammalian cells for a variety of biosensing, drug studies, and therapeutic applications.15,16 In this study, we used the liposome strategy to deliver novel lipid-like functional molecules efficiently to a cell surface, where liposome fusion takes advantage of hydrophobic interactions of micelles and lipid bilayers to insert into the outer cell membrane structure, while the composition of the liposome nanoparticle plays a significant role in inducing particle adhesion and fusion.

In order to tailor both the cell surface and the nucleic acid complex with complementary molecules that can undergo a chemoselective click reaction in vitro and in vivo without side reactions, we used bio-orthogonal chemistry. Bio-orthogonal chemistry refers to a special suite of organic chemistry reactions that can be performed at physiological conditions in complex mixtures including serum containing media and in vivo and in vitro biological systems without side reactions with native biomacromolecules.17,18 Tremendous research has been performed to investigate and expand the scope of these special chemical reactions. Several new types of bio-orthogonal reactions have been discovered including click, hydrazone, thiol–ene, Diels–Alder, etc. However, the most popular click reaction is the copper catalyzed Huisgen 3 + 2 alkyne and azide reaction, hydrazone and oxime chemistry. Pioneering efforts by several researchers have shown the utility of these reactions for many biological applications ranging from in vivo targeting, drug delivery, antibody–drug conjugates, protein engineering, proteomics, imaging, and biosensing.19,20

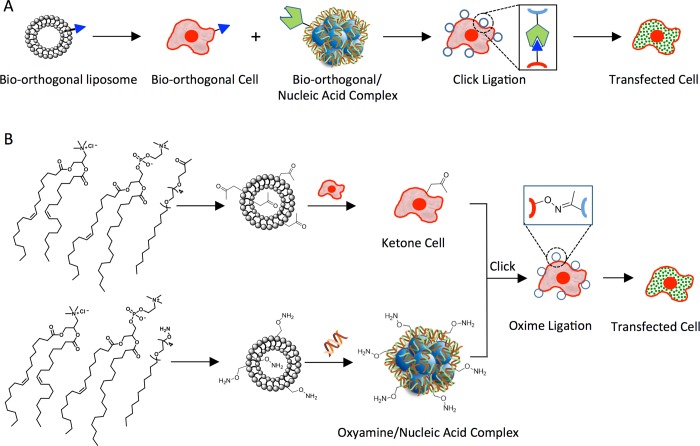

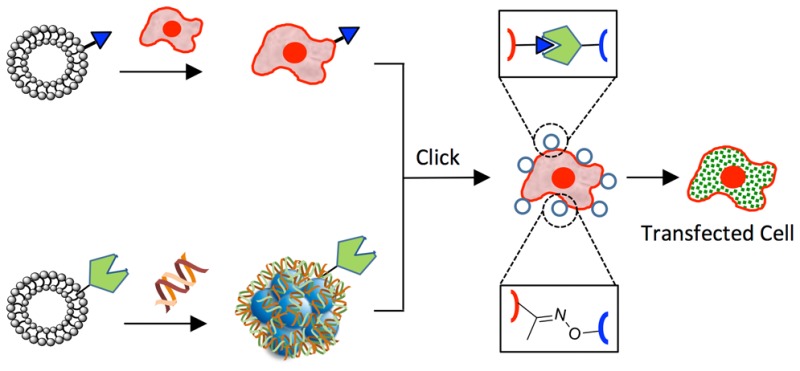

Figure 1 shows a new approach for cell nucleic acid transfection that integrates liposome fusion, bio-orthogonal chemistry, and cell surface engineering (SnapFect). We have previously shown the fast and efficient delivery of lipid-like bio-orthogonal molecules to cell surfaces via liposome fusion that provide cells with new capabilities ranging from photochemical, redox, and biosensor for a range of applications.21−23 We have also demonstrated the assembly of cells through bio-orthogonal click chemistry at the cell surface interface in cell culture conditions and in microfluidics to generate a range of coculture spheroid and 3D tissues for stem cell differentiation studies and for the generation of functional liver and cardiac tissues.24−29

Figure 1.

Schematic of the combined liposome fusion, bio-orthogonal chemistry, and cell surface engineering strategy for selective nucleic acid transfection of cells (SnapFect). (A) A liposome containing a bio-orthogonal lipid-like molecule is delivered to a cell surface via rapid liposome fusion. A complementary bio-orthogonal nucleic acid/liposome complex is formed and added to the tailored cell. The nucleic acid/liposome complex undergoes a fast click reaction at the cell surface. The nucleic acid/lipoplex is then endocytosed where the nucleic acid/lipoplex dissociates and is translated. (B) A molecular view of the mild and selective bio-orthogonal mediated transfection of cells. A bio-orthogonal liposome that is slightly positively charged containing a ketone group is synthesized and added to cell culture to facilitate ketone display through cell surface fusion. A complementary oxyamine liposome is generated that is slightly positively charged in order to complex with nucleic acids. The oxyamine/nucleic acid lipoplex is then added to the ketone presenting cells where rapid oxime formation occurs at the cell surface. The nucleic acid is then endocytosed and released within the cell. No transfection occurs if either of the bio-orthogonal pair is missing from the components. The SnapFect strategy is mild, fast, and specific and relies on an interfacial click reaction for transfection.

In this study, the bio-orthogonal liposome fuses rapidly to a range of cell types to present the functional group on the cell surface. The liposome fusion strategy for tailoring cell surfaces is fast and efficient and does not require complex, slow, or laborious molecular biology or invasive metabolic biosynthesis technology (Figure 1A). The liposome fusion cell surface engineering strategy is mild and does not alter cell viability or cell behavior. A complementary bio-orthogonal liposome is used to complex with nucleic acids to generate a hybrid bio-orthogonal nucleic acid/lipoplex. Upon addition of the bio-orthogonal nucleic acid/lipoplex to the engineered cell a rapid click ligation occurs at the cell surface. The nucleic acid/lipoplex is then internalized, released, and expressed for efficient transfection of the cell.

Figure 1B describes a molecular view of the bio-orthogonal mediated transfection strategy. We have previously shown the use of liposome fusion to deliver and install ketone and oxyamine groups on cell surfaces for applications in coculture spheroid and tissue engineering. A keto-liposome is formed and delivered to the target cell. A complementary oxyamine-liposome is complexed with nucleic acids to form a bio-orthogonal oxyamine/nucleic acid-lipoplex. The lipoplex is then added to the cells where it rapidly forms an oxime bond to the cell surface. The association is based on a bio-orthogonal click chemical ligation method and not through electrostatics or physical adsorption processes. The lipoplex is then endocytosed, and the nucleic acid is released and expressed to transfect the cell.

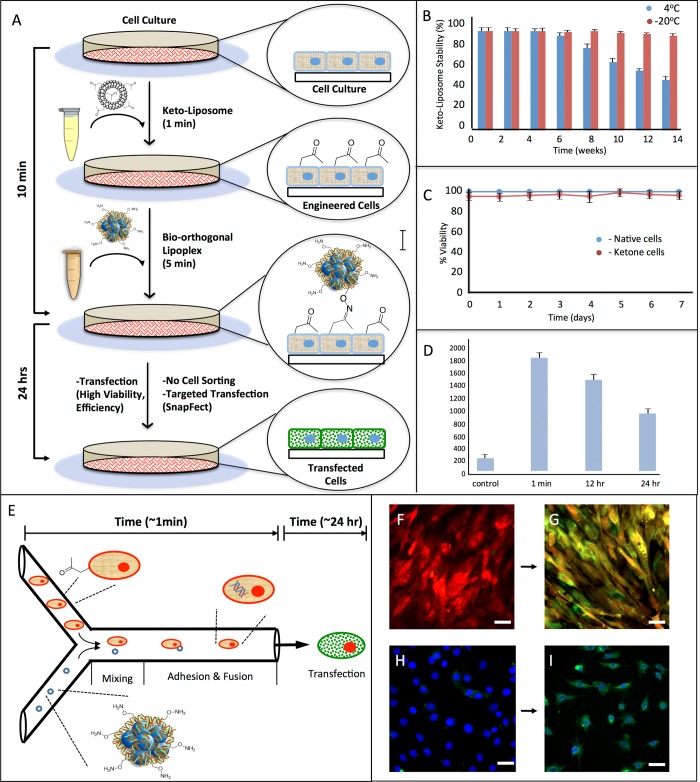

Although the key parameters for successful cell transfection are the viability and efficiency rate and the broad scope of cell types to be transfected, equally important considerations for the practical utility of transfecting cells are the number of steps, the cost of reagents, and the duration of the transfection procedure. Ideally, the transfection reagents are stable and can be stored without significant degradation or loss of transfection ability for long time periods, and the number of steps are minimal and performed in serum containing cell culture media. Figure 2A shows the general SnapFect transfection procedure based on bio-orthogonal mediated reagents. To a cell culture the keto-liposome 100 μL at 5% v/v is added for 5 min. We found efficient installation of the ketone group on the cell surface within seconds to minutes of liposome exposure. The bio-orthogonal oxyamine lipoplex is formed through straightforward addition of the oxyamine lipoplex to pDNA. To the keto engineered cells the bio-orthogonal oxyamine lipoplex is added for 5 min. Interfacial oxime ligation occurs at the cell surface, and the cells are then evaluated after 24 h for transfection viability and efficiency. The overall SnapFect transfection procedure is 2 steps and takes less than 10 min to complete. Figure 2B shows the plot of the stability of the liposome ketone reagent. The keto-liposome can be generated with straightforward procedures and stored in the liposome format for months at low temperatures without loss of transfection ability. Figure 2C is a plot describing the viability of cells undergoing the liposome fusion procedure to install ketones on the cell surface. We have previously shown that the liposome fusion procedure is mild and fast and that the cells are indistinguishable from native cells in behavior and viability.21−29Figure 2D shows that the ketone groups on the cell surface after liposome fusion are transient and decrease over time due to cell growth and proliferation. Flow cytometry and viability studies show that the number of bio-orthogonal groups on the cell surface are few in number and reduced after a few rounds of cell division. The liposome fusion procedure is fast and mild, and we found that cells presenting bio-orthogonal groups compared to control native cells are indistinguishable in viability and behavior.21−29 We discovered that a 1 min exposure of keto-liposomes to cells installs approximately 2000 ketone groups on the cell surface by flow cytometry. Over time, the cells proliferate and the ketone groups are diluted from the cells through growth and division. After 24 h the amount of ketone groups on the cell surfaces is reduced and the treated cells are indistinguishable from nontreated (control) native cells.21−23 This transient nature of the ketone group dilution from the cell surface is a key feature of this strategy and is important for various post-transfection applications. The ketone group is only temporary and used as a molecular handle for targeting the cell for transfection (transient cell surface engineering). Figure 2E shows that the bio-orthogonal mediated transfection method is compatible with various technologies and can also be performed in microfluidic flow. We observed that less than 1 min is required for cells to be efficiently decorated with ketone groups and less than 1 min for lipoplex adhesion in microfluidic flow (0.8 μL/min). Cells were evaluated after 24 h and showed high transfection efficiency and viability (>90%). Red fluorescent protein (RFP) keto cells were flowed through a microfluidic channel where a bio-orthogonal oxyamine lipoplex (containing plasmid green fluorescent protein (pGFP)) rapidly adhered with the cell. After 24 h all the RFP cells were expressing GFP and turned either yellow or green. Figure 2H shows that fibroblast cells are also efficiently transfected in microfluidic flow to express GFP. The microfluidic integration with transfection demonstrates the flexibility of the SnapFect strategy and the ability to combine this method with advanced multiplex technologies. Furthermore, we performed a series of siRNA knockdown experiments using the SnapFect method. For example, to a population of GFP expressing Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts that were tailored with ketone groups we added the GFP siRNA complexed with oxyamine. Using a similar protocol as described in Figure 2A we observed efficient knockdown of GFP in the fibroblasts with high viability. The SnapFect method may be used for both transfection and siRNA knockdown applications. It should be noted that the ketones on the cell surface are reduced over time similar to a transient transfection. By modulating the time and concentration of keto-liposomes, varying amounts of ketones may be installed on the cell surface (2,000–100,000). We found that cells that contained initially over 50,000 ketones determined by flow cytometry were able to undergo click transfection even after several rounds of cell division (3 or 4 rounds of division) and time (4–7 days) post liposome fusion. Although the amount of ketone lipids is reduced due to dilution from cell proliferation and time, there remain enough ketones on the cell surface to foster the bio-orthogonal mediated association and transfection of the oxyamine nucleic acid lipoplex. This observation may be important for new types of experiments that require delayed cell transfection.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the overall straightforward procedure to transfect cells via bio-orthogonal chemistry and cell surface engineering (SnapFect). (A) A keto-liposome is added to cells in culture. The liposome rapidly fuses with cells and presents the ketone groups on the cell surface within seconds. To the keto-engineered cells a DNA/oxyamine lipoplex is added. The bio-orthogonal DNA/lipoplex quickly clicks onto the cell surface via oxime ligation. The oxime reaction is fast and mild and can be performed at physiological conditions in vitro and in vivo. The DNA is then endocytosed/released and transfects the cell. The procedure is straightforward, uses minimal time and steps, and can be performed on adhered or suspended cells and in serum containing cell culture. (B) Stability of the liposome-ketone reagent for cell surface engineering at various temperatures and durations. The entire experiment was replicated, run independently over 20 times, and averaged. (C) Viability of the cells after liposome-ketone fusion treatment. The liposome fusion method is mild, and there is no difference in viability or behavior between treated and normal untreated (native) cells. (D) The liposome-ketone fusion to present ketones on the cell surface is transient. After 1 min of liposome-ketone fusion treatment to the cells, the cells have approximately 2000 ketones, as determined by flow cytometry, which are rapidly reduced on the cell surface after 24 h due to dilution via growth and division of the cells. (E) The bio-orthogonal mediated nucleic acid transfection strategy is fast and can be performed in a microfluidic format. The mixing of the keto tailored cells with the nucleic acid lipoplex for transfection occurs in less than 1 min. The cells are then visualized after 24 h and show high viability and efficiency of transfection. The entire experiment was replicated over 100 times and run independenly, and the images were compared to controls where one or both pairs of the click chemistry groups are missing from the surface of the cell or the nucleic acid complex. (F) Red fluorescent protein expressing fibroblasts that are transfected with GFP in the microfluidic format. The cells turn yellow and green after GFP transfection via the fast microfluidic method (G). (H) Nuclei stained 3T3 fibroblasts are flowed through the microfluidic channel and mixed with GFP nucleic acid lipoplex (1 min). (I) The fibroblasts are visualized after 24 h and are efficiently transfected and show green fluorescence with high viability and efficiency. Each microfluidic transfection experiment was replicated over 100 times, analyzed by fluorescence imaging and protein gel analysis, and compared to controls where one or both pairs of the click chemistry pair are missing from the surface of the cell or in the nucleic acid complex.

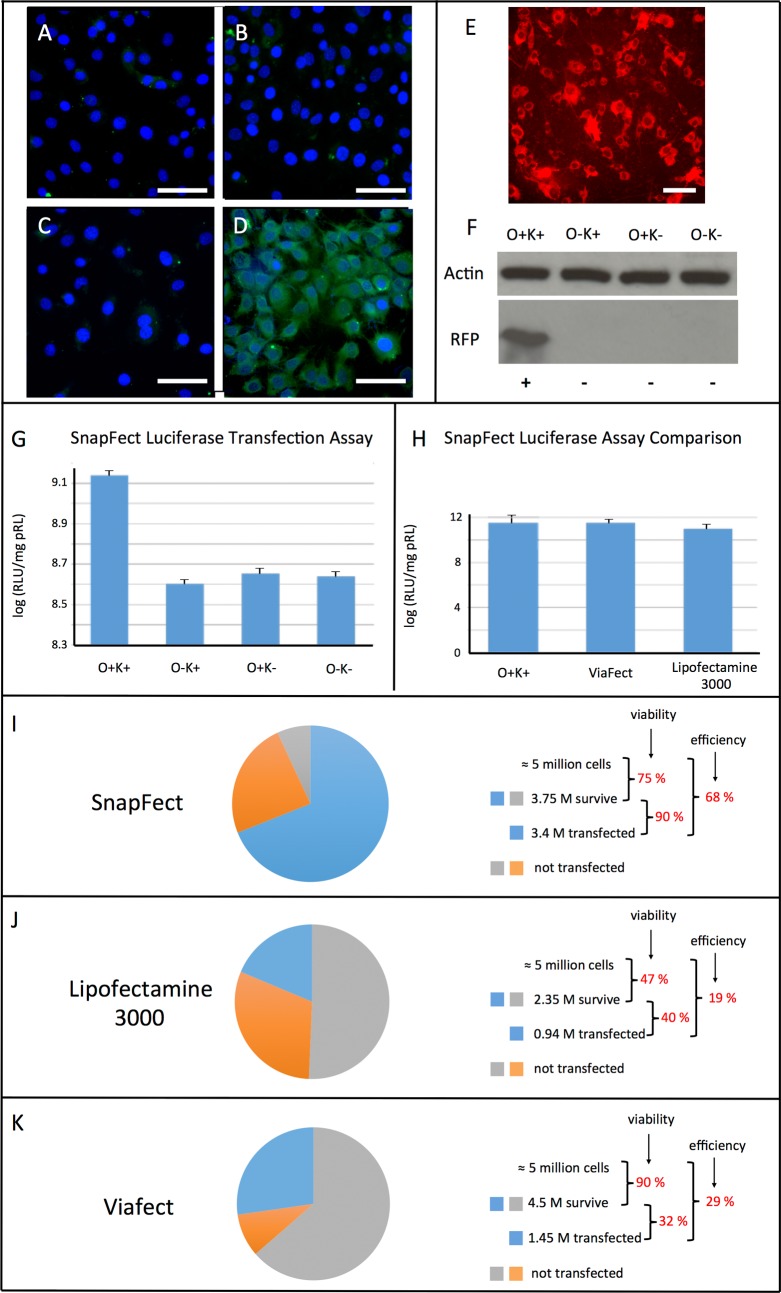

To demonstrate the bio-orthogonal mediated transfection (SnapFect) of cells we performed and evaluated several standard transfection assays. Figure 3A shows a fluorescent image of native C3H10T1/2 cells stained with DAPI, a nuclei dye in culture. Figure 3B shows these same cells after treatment with a bio-orthogonal GFP-oxyamine lipoplex. While no transfection occurred due to the C3H10T1/2 cells not presenting ketones on their surface. Figures 3C and 3D show that, when C3H10T1/2 cells present ketone groups, they are efficiently transfected with GFP delivered via a bio-orthogonal nucleic acid/oxyamine lipoplex. Figure 3E shows the fluorescent image result of the transfection of pRFP (red fluorescent protein) to ketone presenting fibroblasts. Figure 3F presents a Western blot analysis showing that only when the right combination of bio-orthogonal pairs is presented on the cell surface and on the nucleic acid lipoplex respectively does transfection occur. Fibroblasts presenting ketone groups via liposome fusion and delivery (K+) on their surfaces are efficiently transfected with pRFP oxyamine/lipoplexes (O+). Any other combination does not result in transfection, clearly demonstrating that transfection is mediated by the bio-orthogonal click reaction and not by an electrostatic or other nonspecific interaction process.

Figure 3.

Bio-orthogonal mediated transfection (SnapFect) evaluation and comparison. (A) Fluorescent image of native C3H10T1/2 cells with DAPI nuclei stain. (B) Fluorescent image of native C3H10T1/2 cells treated with oxyamine containing DNA-lipoplex. No transfection occurred since the cells did not present ketone groups on their cell surface. (C) Fluorescent image of native CH310T1/2 cells and (D) image of the cells presenting ketone groups exposed to GFP oxyamine lipoplex after 24 h. GFP expression resulted due to specific bio-orthogonal mediated transfection. (E) Representative image of RFP transfected fibroblast cells via click chemistry mediated transfection. (F) A protein gel showing that the expression of RFP is mediated by the correct pairing of the bio-orthogonal chemistry functional groups on the cell surface and on the DNA-lipoplex. O+ and K+ represent oxyamine containing lipoplexes (O+) and ketone presenting cells (K+) used for RFP transfection. O– and K– represent conditions where either oxyamine or ketone was not present on the cell surface or DNA-lipoplex. Only the correct combination resulted in bio-orthogonal mediated transfection. These experiments were performed over 10 times and showed similar results. (G, H) Luciferase transfection assay for fibroblasts using the bio-orthogonal mediated transfection strategy. (H) Comparison of luciferase assay transfection for the bio-orthogonal mediated strategy (SnapFect) and leading commercial transfection reagents. The luciferase assays were replicated over 10 times and averaged (p < 0.1) (I–K) Comparison of viability, efficiency, and amount of cells transfected between SnapFect and other commercial transfection reagents. Initially 5 million cells were used, and the amount of surviving cells that were transfected resulted in the percent efficiency of transfection. SnapFect has the highest ratio of viable cells to viable and transfected cells and therefore does not require further separation of cells and requires fewer cells for transfection. For example, SnapFect requires only 5 million cells to generate 3.4 million transfected cells without post sorting of cells, whereas Lipofectamine and Viafect require 18 million and 11.5 million cells respectively to obtain 3.4 million transfected cells with the additional step of separating viable transfected versus viable nontransfected cells. Each of the experiments (I–K) was replicated over 30 times and averaged.

Figure 3G shows a transfection assay based on expressing luciferase in fibroblast cells. The luciferase enzyme is only expressed and functional in cells when the correct bio-orthogonal pair is used for transfection. All other combinations of surface presenting functional groups lead to no transfection and therefore no luciferase activity. Figure 3H shows a comparison of luciferase expression in cells for our bio-orthogonal transfection (SnapFect) compared to two cationic based commercial reagents. Figure 3I–K shows a comparison of viability and efficiency of transfection between SnapFect and commercial reagents. For these sets of experiments a population of 5 million cells were used and compared for transfection viability and efficiency after the transfection protocol using the commercial reagents. Viability was calculated based on the number of cells that survived compared to the initial 5 million cell population after treatment with the transfection reagent. The efficiency of transfection was then calculated in two ways. The first efficiency is the ratio of the number of viable transfected cells to the number of viable surviving cells after treatment. The second (overall efficiency) is the number of viable transfected cells to the initial amount of total cells (5 million). For SnapFect the viability is 75% (3.75 million cells survived over 5 million initial cells), the efficiency is 90% (3.4 million transfected cells over 3.75 million cells), and the overall efficiency is 68% (3.4 million transfected cells over 5 million initial cells). A key consideration is that the number of cells that survive compared to the number of cells transfected (first efficiency) is very high for SnapFect compared with other reagent products. With a high first efficiency no additional sorting step is required for post processing, since essentially all cells that survive are transfected. However, for the other reagents the first efficiency is 40% and 32% respectively. This requires a postsorting step to separate the surviving nontransfected cells and the surviving transfected cells, leading to extra procedures and increased time, cost, and effort required to produce a transfected population of cells. As a comparison, SnapFect requires only 5 million cells to generate 3.4 million transfected cells without postsorting of cells, whereas Lipofectamine and Viafect require 18 million and 11.5 million cells respectively to obtain the same 3.4 million population of transfected cells, with the added step of separating via FACS to obtain viable transfected cells. Because of the mild bio-orthogonal mediated transfection of SnapFect, fewer cells, reagents, and media and less time and labor are necessary, along with the elimination of the additional postsorting step of other methods.

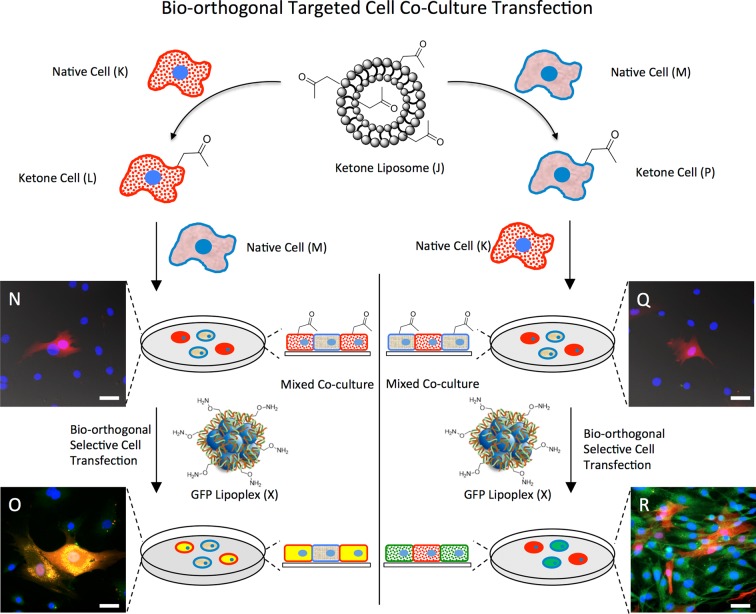

The ability to selectively target a specific cell or cell type for gene and drug delivery in a coculture in vitro and in vivo is of fundamental interest and a common major hurdle in many therapeutic applications for cancer and other chronic diseases. By utilizing the SnapFect strategy we demonstrate a precision transfection method to selectively transfect a single cell type in a coculture (Figure 4). To selectively deliver pDNA two cell populations were chosen (C3H10T1/2 (M) and RFP HDNFs (K)) where each was cell surface engineered with ketone liposomes and then mixed with a second untreated native cell type. In one scenario (left panel of Figure 4), this produced a coculture containing keto-RFP HDNF (L) cells and native C3H10T1/2 cells (M), with another coculture containing native RFP-HDNF (K) cells and keto-C3H10T1/2 cells (P) (right panel of Figure 4). Both of the cocultures were then treated with an identical bio-orthogonal pGFP oxyamine-lipoplex (X). Fluorescence microscopy of DAPI stained keto-RFP HDNF (N) cells and native C3H10T1/2 cells (M) show upon treatment with oxy-lipoplexes of pGFP that only RFP-HDNF cells are transfected and turn yellow due to a combination of red and green fluorescence within the cell (Figure 4 O). Fluorescence imaging of DAPI stained native RFP-HDNF (K) cells and keto-C3H cells (P) shows a coculture. Upon treatment with bio-orthogonal oxyamine-lipoplex pGFP (X) keto-C3H10T1/2 (P) cells express GFP protein selectively and turn green, while the nonlabeled RFP-HDNF cells remain unaffected (Figure 4R). These results demonstrate that the SnapFect method is able to precision target and transfect a specific cell type in a coculture. Since the transfection is only mediated by bio-orthogonal chemistry and not electrostatic or other nonspecific interactions, this selectivity may open many new possibilities for targeted delivery and transfection in vitro and in vivo for new applications, using these artificial receptors.

Figure 4.

Precision transfection via bio-orthogonal mediated ligation in cocultures. (Left) RFP expressing HDNF cells (K) are cell surface engineered to present ketone groups (L) via rapid liposome fusion (J). Nonfluorescent C3H10T/1/2 cells and ketone presenting HDNF cells (L) are mixed to generate a coculture (N). To this coculture a bio-orthogonal oxyamine presenting GFP-lipoplex (X) is added. Only the ketone presenting cells (L) are targeted for selective transfection via the oxyamine presenting lipoplex (X) via oxime ligation. (O) Fluorescent image showing that only the HDNF presenting ketones are transfected with GFP and are yellow. (Right) Nonfluorescent C3H10T1/2 cells (M) are cell surface engineered to present ketone groups (P) via rapid liposome fusion (J). Red fluorescent HDNF cells (K) and ketone presenting C3H10T1/2 cells (P) are mixed to generate a coculture (Q). To this coculture a bio-orthogonal oxyamine presenting GFP-lipoplex (X) is added. Only the ketone presenting cells (P) are targeted for selective transfection via the oxyamine presenting lipoplex (X) via oxime ligation. (R) Fluorescent image showing that only the CH310T1/2 cells presenting ketones are transfected with GFP and turn green. The experiments were replicated over 20 times with similar results as determined by fluorescence imaging and protein gel analysis. These coculture results show that transfection is only mediated through targeted bio-orthogonal chemistry and not nonspecific electrostatic interactions.

Conclusion

In summary, a new strategy that integrates liposome fusion, cell surface engineering, and bio-orthogonal chemistry (SnapFect) was developed and used to demonstrate rapid and efficient nucleic acid cell transfection and knockdown via click chemistry. The approach installs a bio-orthogonal molecule on the surface of a cell, while the complementary bio-orthogonal functional group is associated with a nucleic acid that subsequently performs an interfacial click reaction at the cell surface for efficient nucleic acid delivery. Unlike conventional reagent transfection methods that use various molecules composed of positively charged polyamines to complex with nucleic acids which then are associated with negatively charged cells via electrostatic association, the SnapFect method relies on a precise chemoselective click chemistry. The method was designed to have broad scope and utility, which is mild and efficient, has minimal steps and no additional sorting step (of viable transfected and viable nontransfected cells), and can be performed on a range of cell types and in various cell culture conditions. Furthermore, selective cell transfection and gene silencing can be performed in cocultures due to the specific requirement that only cells presenting bio-orthogonal groups are targeted for transfection. As this is a new technology for target transfection, there would be numerous applications in paracrine signaling and tissue engineering. For example, two different cell types may be assembled and the signaling between them studied over time and then modified with a real-time transfection that would allow for a time course evaluation of cell behavior response. We believe that there would be numerous new experiments in a systems biology format where multiple cell types signaling networks could be studied but a particular pathway targeted (modulated) by transfection and how that would affect various pathways and cellular behavior including motility, apoptosis, differentiation, and cell division. We also show that the SnapFect transfection method can occur in microfluidic flow, which opens numerous applications using the power of microfluidic technology. The liposome fusion method is fast and can be used to simultaneously engineer the cell surface with bio-orthogonal groups and to deliver various other small molecules and cargoes into the cell. We have demonstrated the bio-orthogonal cell surface engineering approach to generate cells with photoactive, redox, and fluorescent capabilities.21−23 Furthermore, we have used the method to generate coculture spheroids and scaffold free 3-dimensional tissues for stem cell differentiation studies and liver and cardiac tissue on-a-chip applications.28,29 The key feature in this strategy is the rapid placement of an artificial receptor (bio-orthogonal group) on the cell surface without the use of invasive molecular biology or the use of modified metabolites to tailor the cell surface. This strategy is a platform technology and can be used to label and deliver a range of molecules to cells in vitro and in vivo. Future studies to tailor cell surfaces with various bio-orthogonal groups, nanoparticles, or fluorescent probes may be pursued for various theranostic and systems biology type applications and studies.30,31 The SnapFect method provides a new way of thinking about delivery and targeting cells for various applications in fundamental biological studies from gene editing to immunotherapy.32,33 The method is also compatible with other nucleic acid based biotechnologies such as CRISPR and RNAi. We have previously shown that the cell surface engineering approach also works in a wide range of cell types including stem cells and primary cells, while also showing applicability in bacteria. The ability to install a range of molecules on the cell surface will have broad utility in cell biology and tissue engineering and as a molecular handle for a range of bioanalytical sorting, in vivo transfection, and tracking technologies.34,35

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Cell Cultures

Cellular Culture C3H10T1/2

For our model system we used C3H10T1/2 mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (ATCC) which were cultured and incubated for 3 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in 10 cm culture plates (Fisher Scientific) with media changed every other day using DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1% v/v PS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) as additives. The cell cultures used for experiments were between 2 and 6 passages.

Cellular Culture HDNF/RFP

Red fluorescent protein expressing human neonatal dermal fibroblasts (ATCC) was cultured from liquid nitrogen storage and maintained using DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1% v/v PS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) as additives and passaged every 3 days. The cell cultures used for experiments were between 2 and 6 passages.

Cellular Engineering Ketone Liposome Formulation and Cell Priming

To form liposome solutions bearing ketone functionalities, into a 5 mL vial was added 120 μL of 2-dodecanone (Sigma-Aldrich) (10 mg/mL in CHCl3), followed by 454 μL of POPC (Avanti Polar Lipids) (10 mg/mL in CHCl3) followed by 10 μL of DOTAP (Avanti Polar Lipids) (10 mg/mL in CHCl3), which were then allowed to evaporate over 24 h. Once the CHCl3 is evaporated, 3 mL of fresh PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) is added, followed by tip sonication. Tip sonication of the lipid suspensions was carried out over 10 min in a 23 °C water bath and stored at 4 °C at 30 W. To apply ketone cell surface engineering to cultured cells, they need to be cultured with a confluency between 75 and 80%; the cell culture medium was then aspirated, followed by the addition of fresh serum containing medium (2 mL), and 5% v/v ketone liposome suspension (100 μL) was added and incubated with the cells under growth conditions for 5 min followed by three 3 mL washes of PBS and addition of fresh growth medium to the cells awaiting transfection.

General SnapFect Transfection of C3H10T1/2 Cells with phMGFP

C3H10T1/2 cells were cultured using standard protocols using 10% FBS and 1% penicillin streptomycin high glucose DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) in 10 cm culture plates (Fisher Scientific) over 2 days to 75% confluency before use. The C3H10T1/2 cells were then trypsinized using 0.25% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) 3 mL for 3 min followed by quenching with 6 mL of growth medium and centrifugation at 800 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was then isolated and resuspended in growth medium 10 × 103 cells/mL and seeded onto 1 cm2 prepared glass slides (180 μL). The following day the cells were treated using the general ketone cell surface engineering protocol, followed by the immediate addition of the prepared oxyamine lipoplex. To form the oxyamine lipoplex, into a sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube was added 15 μL of the oxyamine liposome suspension containing 210 μL of POPC (10 mg/mL), 60 μL of DOTAP (10 mg/mL), and 120 μL of dodecyl (tetraethylene glycol) oxyamine (10 mg/mL) in 3 mL of PBS, using tip sonication over 10 min in a 23 °C water bath and storage at 4 °C at 30 W. Then the fluorescent protein of interest was added, typically 2.0 μg of phMGFP (1.4 μg/μL). This mixture was then incubated at room temperature 23 °C for 30 min, then diluted with 200 μL of serum free DMEM medium, carefully pipetted onto the slide, and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 5 min. After a 5 min incubation period the samples were given HNDF serum containing growth medium and incubated for another 24–48 h. The slides were then fixed by washing 3 times with 3 mL of PBS followed by the addition of 5% formalin solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. The formalin solution was then drained and washed once with PBS followed by mounting to glass microscopy slips for fluorescent microscopy using an inverted Zeiss AX10 fluorescence microscope.

Targeted Coculture Method (HNDF/RFP and C3H10T1/2) Transfection of phMGFP upon HNDF Cells

HNDF cells were grown in 10 cm culture plates using standard protocol using 10% FBS and 1% penicillin streptomycin high glucose DMEM medium (Sigma-Aldrich) to 80% confluency and then trypsinized using 0.25% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) 3 mL for 3 min followed by quenching with 6 mL of growth medium and centrifugation at 800 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was then isolated and resuspended in growth medium 5 × 103 cells/mL and seeded onto 1 cm2 prepared glass slides (180 μL). The cells were then incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, followed by the addition of 2 mL of fresh growth medium. The following day (approximately 16 h), the cell medium was changed with fresh medium, and 5% v/v ketone liposome suspension (100 μL) was added to the growth medium and incubated for 5 min followed by three 3 mL washes of PBS. C3H10T1/2 cells were grown in 10 cm culture plates using the standard protocol and, once 75% confluent, were trypsinized using 3 mL of trypsin for 3 min followed by the addition of 6 mL of growth medium and centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was isolated and resuspended in growth medium to 1 × 104 cells/mL. The tissue plates containing slides with adherent HNDF/RFP cells were then drained of medium, and then 180 μL of C3H10T1/2 cell suspension was added and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 followed by the addition of 2 mL of fresh growth medium and incubation for 16 h. The lipoplex suspension was made fresh each time. To a sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube was added 60 μL of the oxyamine liposome suspension containing 410 μL of POPC (10 mg/mL), 60 μL of DOTAP (10 mg/mL), and 120 μL of dodecyl (tetraethylene glycol) oxyamine (10 mg/mL) followed by the addition of 2.0 μg of phMGFP (1.4 μg/μL). This mixture was then incubated at room temperature 23 °C for 30 min and then diluted with 700 μL of serum free DMEM medium. Then the 1 cm2 glass slides were washed twice with 3 mL of PBS; with the PBS drained, 200 μL of the lipoplex solution was carefully pipetted onto the slide and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 5 min. After the 5 min incubation period the samples were given HNDF serum containing growth medium and incubated for another 24–48 h. The slides were then fixed by washing 3 times with 3 mL of PBS followed by the addition of 5% formalin solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. The formalin solution was then drained and washed once with PBS followed by mounting to glass microscopy slips for fluorescent microscopy using an inverted Zeiss AX10 fluorescence microscope.

Firefly Luciferase Stability Assay

C3H10T1/2 mouse embryonic fibroblast cells were cultured and incubated for 3 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in 10 cm culture plates (Fisher Scientific) with medium changed every other day using DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1% v/v PS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) as additives. The cell cultures used for experiments were between 2 and 6 passages. The cells were then transferred using 3 mL of trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) into 6 well plates (Fisher Scientific) using 75K seeding density. The cells were grown overnight, transfected using the general transfection protocol the following day, and incubated for 24 h. The cells were surface engineered by forming a liposome solution bearing ketone functionalities, where a clean 5 mL vial was used, and 120 μL of 2-dodecanone (Sigma-Aldrich) (10 mg/mL in CHCl3) was added, followed by 454 μL of POPC (Avanti Polar Lipids) (10 mg/mL in CHCl3), followed by 10 μL of DOTAP (Avanti Polar Lipids) (10 mg/mL in CHCl3), which were then allowed to evaporate over 24 h. Once the CHCl3 is evaporated, 3 mL of fresh PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) is added, followed by tip sonication. Tip sonication of the lipid suspensions was carried out over 10 min in a 23 °C water bath followed by storage at 4 °C at 30 W.

Using our best conditions for transfecting pGFP (above), we substituted Firefly Luciferase (pRL) (Promega) to transfect C3H10T1/2 cells. The pRL lipoplex liposomes were synthesized by using a sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube: 60 μL of the oxyamine liposome suspension containing 210 μL of POPC (10 mg/mL), 60 μL of DOTAP (10 mg/mL), and 120 μL of dodecyl (tetraethylene glycol) oxyamine (10 mg/mL) was added followed by the addition of 2.0 μg of pRL (1.4 μg/μL). This mixture was then incubated at room temperature 23 °C for 30 min, then diluted with 200 μL of serum free DMEM medium, carefully pipetted onto the slide, and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 5 min. After the 5 min incubation period, the samples were washed with 3 mL of PBS, given HNDF serum containing growth medium, and incubated for another 24 h. Control experiments were conducted through the omission of ketone lipids to the pretreatment of the cells before transfection, while retaining the original ratio of background lipids, and through the omission of oxyamine bearing lipids from the formulation of the lipoplex. Transfected cell culture plates were then transferred to a 0 °C ice bath, washed twice with 2 mL of PBS, treated with 160 μL of lysis buffer, and mechanically scraped from the dishes and transferred into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. The lysate was then heated to 100 °C using a Labnet Accublock heating block for 5 min and frozen at −80 °C overnight. The following day pRL expression was quantified using an automated Berthold Lumat 3 (LB 9508) with luminol.

Western Blot Assay

Expression using pRFP was conducted in parallel to pRL luciferase expression analysis. C3H10T1/2 cells were collected using NP-40 lysis buffer (0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8], and 0.1 M NaF) containing 10 μg/mL (each) leupeptin and aprotinin, 5 μg/mL pepstatin A, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate. Protein extracts were denatured in SDS loading buffer at 95 °C for 5 min and then run in a 10% SDS–PAGE gel, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore), and blocked in 5% skim milk for 1 h prior to antibody incubation, using rabbit RFP antibody (Life Technologies).

Comparison Luciferase Assays Using Viafect and Lipofectamine 3000

Viafect (Promega) and Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies) reagents were optimized for use with C3H10T1/2 with phGFP and optical microscopy to determine the highest transfection efficiency using the recommended manufacturer protocols, and our general SnapFect protocol was used. Using the general growth protocol for C3H10T1/2 cells, the cells were seeded into 6 well plates at 35000 cells/well overnight. The following day 2.0 μg of pRL (0.14 μg/μL) was mixed with 6.0 μL of Viafect reagent, incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and then diluted to 200 μL of total volume using non serum containing medium. Then 200 μL of Viafect solution was added to the cells containing 2 mL of serum containing medium and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For Lipofectamine, the following day 9.8 μg of pRL (1.4 μg/μL) was mixed with 4.0 μL of P3000 reagent for 5 min and diluted with 125 μL of serum free medium. Then 4.4 μL of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent was diluted with 125 μL of serum free medium, and the two solutions were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Then 250 μL of complex solution was added to the cells containing 2.0 mL of serum containing medium and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Then the cells were investigated using our above Luciferase protocol.

Viability and Efficiency Comparison Assays Using phGFP of Viafect and Lipofectamine

Viability was determined using the above scaled up Luciferase protocol. Viafect (Promega) and Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies) reagents were used to transfect C3H10T1/2 cells with phGFP, and optical microscopy was used to determine viability and efficiency through cell counting using the recommended manufacturer protocols. Using the general growth protocol for C3H10T1/2 cells, the cells were seeded into 6 well plates at 35000 cells/well overnight. The following day 2.0 μg of phGFP (1.4 μg/μL) was mixed with 6.0 μL of Viafect reagent, incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and then diluted to 200 μL of total volume using non serum containing medium. Then 200 μL of Viafect solution was added to the cells containing 2 mL of serum containing medium and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For Lipofectamine, the following day 9.8 μg of phGFP (1.4 μg/μL) was mixed with 4.0 μL of P3000 reagent for 5 min and diluted with 125 μL of serum free medium. Then 4.4 μL of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent was diluted with 125 μL of serum free media, and then the two solutions were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Then 250 μL of complex solution was added to the cells containing 2.0 mL of serum containing medium and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. These experiments were all performed in parallel. Viability was determined through vital dye staining using 0.4% Trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) using the manufacturer protocol along with a (Bright-Line) visual hemocytometer for cell counting. Cell efficiency was determined using the above transfection protocols for Viafect, Lipofectamine, and SnapFect, where upon 24 h incubation with the relevant reagent the cells were fixed and observed using fluorescence microscopy. The visually fluorescent cells were counted as transfected while dark cells were counted as nontransfected using Image-J and compared with the cell count of control populations. Nine images from each well were averaged to determine efficiency of the reagent.

Microfluidic Device Fabrication and Design

The microchannel was designed with a simple Y-shape, where cell suspensions are brought together in the Y-joint mixing zone. In order to make a simple, cheap, and robust device, PMMA blocks were used as the device substrate. The experimental device was fabricated using laser ablation to etch PMMA blocks (1/8 in thickness, 1.25 in length, and 1.42 in width). The PMMA channels were laser etched using Versalaser 2.30 with a CO2 laser at 14.25 W power to produce parabolic channels with a measured base width of 170 μm, a peak height of 200 μm, and a channel length of 1.5 cm. The fluid inlet connections were fabricated using 406 μm (0.016 in) o.d. stainless steel capillary tubes with a 203 μm (0.008 in) i.d. and a length of 2.0 cm, which were embedded into the PMMA blocks using thermal heating to be in line with the channel flow axes, while the fluid outlet capillary was cut to 2.0 cm and embedded by thermal heating and pressure similarly to the fluid inlets and allowed to cool. The top block of PMMA is used to cap the channel through thermal bonding with the etched bottom block in a convection oven for 2 h at 275 °C and allowed to cool completely to room temperature over 2 h under pressure. Once cooled, the fluid connections are finished by slipping PEEK tubing (i.d. 203 μm/0.008 in) over the metal capillary and sealed using epoxy resin (3M). Finally, high pressure HPLC 1 mL Luer lock glass syringes (Hamilton) are connected to the PEEK tubing using finger tight female Luer fittings (UpChurch Scientific).

Microfluidic Transfection in Flow

C3H10T1/2 and HNDF/RFP cells were grown to approximately 80% confluency in 10 cm plastic growth plates (Fisher Scientific) and then treated with 5% vol/vol ketone bearing liposomes in serum containing medium, respectively, for 1 min followed by aspiration of medium; they were washed 3 times with PBS and then detached using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Once the cells were detached and neutralized by DMEM medium (10% FBS), the cell suspension was transferred to a 15 mL centrifuge tube and centrifuged down at 800 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and the remaining pellet was resuspended in DMEM medium to reach a final concentration of 2 × 105 cells/mL. The SnapFect reagent was generated using our oxyamine liposomes using the above general method for SnapFect liposomes. Once the ketone tailored cell suspensions were ready, 250 μL of the ketone tailored C3H10T1/2 suspension was loaded into a sterilized 1 mL gastight Luer lock Hamilton gas chromatography syringe, while 15 μL of the SnapFect reagent was diluted in 250 μL of non serum containing medium and loaded into a sterilized 1 mL gastight Luer lock Hamilton gas chromatography syringe. The connection tubing and microfluidic device were sterilized by passing 1 mL of 70% ethanol solution, followed by 1 mL of PBS buffer. Once sterilized, the loaded syringes were finger tightened onto male Luer connections and placed onto a Harvard 11 PLUS syringe pump. The flow rate was set to 8 μL/min for 5 min to purge air bubbles from the system, then reduced to 0.4 μL/min for 5 min, with a residence time within the device of approximately 1 min, where the initial fluid was discarded and subsequent eluent was collected onto 1 cm2 glass slides with serum containing medium. The 1 cm2 glass slides were prepared in advance and sterilized by sonication in 70% ethanol solution for 30 min. After the microfluidic flow was completed, the collecting slides were transferred to tissue culture plates and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 25 min. Then 3 mL of serum containing medium was added, and the slides were incubated under growth conditions for a further 24 h. After 24 h the transfected cells were then fixed by 3.8% formaldehyde solution for 15 min, followed with gentle washing with PBS. The cell samples were mounted and observed with a Zeiss AX10 fluorescence microscope.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI), OrganoLinx Inc., and a NSERC CREATE grant (Canada).

Author Contributions

M.N.Y. designed the research. P.J.O., S.E., and D.R. performed the research. P.J.O., S.E., D.R., and M.N.Y. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Prof. Yousaf is an equity founder of OrganoLinX Inc.

References

- Naldini L. Gene therapy returns to centre stage. Nature 2015, 526, 351–360. 10.1038/nature15818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon C.; Billiet L.; Midoux P. Chemical vectors for gene delivery: uptake and intracellular trafficking. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 640–645. 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm F. M. Production of recombinant protein therapeutics in cultivated mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 1393–1398. 10.1038/nbt1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharei A.; Zoldan J.; Adamo A.; Sim W. Y.; Cho N.; Jackson E.; Mao S.; Schneider S.; Han M.-J.; Lytton-Jean A.; Bastoe P. A.; Jhunjhunwala S.; Lee J.; Heller D. A.; Kang J. W.; Hartoularos G. C.; Kim K.-S.; Anderson D. G.; Langer R.; Jensen K. F. A vector-free microfluidic platform for intracellular delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 2082–2087. 10.1073/pnas.1218705110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini L.; Blömer U.; Gallay P.; Ory D.; Mulligan R.; Gage F. H.; Verma I. M.; Trono D. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 1996, 272, 263–267. 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewapathirane D. S.; Haas K. Single cell electroporation in vivo within the intact developing brain. J. Visualized Exp. 2008, 17, e705. 10.3791/705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli V.; Robles V.; Cancela M. L.; Acker J. P.; Waskiewicz A. J.; Elezzabi A. Y. An alternative method for delivering exogenous material into developing zebrafish embryos. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 98, 1230–1241. 10.1002/bit.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S.; Webster P.; Davis M. E. PEGylation improves the receptor-mediated transfection efficiency of peptide-targeted, self-assembling, anionic nanocomplexes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 83, 97–111. 10.1078/0171-9335-00363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny G. D.; Bienemann A. S.; Tagalakis A. D.; Pugh J. A.; Welser K.; Campbell F.; Tabor A. B.; Hailes H. C.; Gill S. S.; Lythgoe M. F.; McLeod C. W.; White E. A.; Hart S. A. Multifunctional receptor-targeted nanocomplexes for the delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids to the Brain. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 9190–9200. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoor M.; Buers I.; Sietmann A.; Brodde M. F.; Hofnagel O.; Robenek H.; Lorkowski S. Efficient non-viral transfection of THP-1 cells. J. Immunol. Methods 2009, 344, 109–115. 10.1016/j.jim.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seferos D. S.; Giljohann D. A.; Hill H. D.; Prigodich A. E.; Mirkin C. A. Nano-Flares: Probes for Transfection and mRNA Detection in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 15477–15479. 10.1021/ja0776529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi-Bahktar P.; Mendez-Campos J.; Raju L.; Khalique N. A.; Jubeli E.; Larsen H.; Nicholson D.; Pungente M. D.; Fyles T. M. Structure–activity correlation in transfection promoted by pyridinium cationic lipids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 3080–3090. 10.1039/C6OB00041J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuris J. A.; Zuris J. A.; Thompson D. B.; Shu Y.; Guilinger J. P.; Bessen J. L.; Hu J. H.; Maeder M. L.; Joung J. K.; Chen Z.; Liu D. R. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 73–80. 10.1038/nbt.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. K.; Eberwine J. H. Mammalian cell transfection: the present and the future. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 3173–3178. 10.1007/s00216-010-3821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin V. P. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2005, 4, 145–160. 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson G. L. The Fluid Mosaic Model of Membrane Structure: Still relevant to understanding the structure, function and dynamics of biological membranes after more than 40 years. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 1451–1456. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sletten E. M.; Bertozzi C. R. Bioorthogonal Chemistry: Fishing for Selectivity in a Sea of Functionality. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6974–6998. 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J. R.; Onoa B.; Bustamante C.; Bertozzi C. R. Chemically tunable mucin chimeras assembled on living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 12574–12579. 10.1073/pnas.1516127112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay C. S.; Finn M. G. Click chemistry in complex mixtures: bioorthogonal bioconjugation. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 1075–1101. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D. M.; Nazarova L. A.; Prescher J. A. Finding the Right (Bioorthogonal) Chemistry. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 592–605. 10.1021/cb400828a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D.; Pulsipher A.; Luo W.; Mak H.; Yousaf M. N. Engineering cell surfaces via liposome fusion. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22, 2423–2433. 10.1021/bc200236m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D.; Pulsipher A.; Luo W.; Yousaf M. N. Synthetic Chemoselective Rewiring of Cell Surfaces: Generation of Three-Dimensional Tissue Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8704–8713. 10.1021/ja2022569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elahipanah S.; Radmanesh P.; Luo W.; O’Brien P. J.; Rogozhnikov D.; Yousaf M. N. Rewiring Gram-Negative Bacteria Cell Surfaces with Bio-Orthogonal Chemistry via Liposome Fusion. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27, 1082–1089. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien P. J.; Luo W.; Rogozhnikov D.; Chen J.; Yousaf M. N. Spheroid and Tissue Assembly via Click Chemistry in Microfluidic Flow. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 1939–1949. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W.; Westcott N. P.; Dutta D.; Pulsipher A.; Rogozhnikov D.; Chen J.; Yousaf M. N. A Dual Receptor and Reporter for Multi-Modal Cell Surface Engineering. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2219–2226. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W.; Pulsipher A.; Dutta D.; Lamb B. M.; Yousaf M. N. Remote Control of Tissue Interactions via Engineered Photo-switchable Cell Surfaces. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6313. 10.1038/srep06313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsipher A.; Dutta D.; Luo W.; Yousaf M. N. Cell surface engineering by a conjugation and release approach based on the formation and cleavage of oxime linkages upon mild electrochemical oxidation and reduction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9487–9492. 10.1002/anie.201404099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozhnikov D.; O’Brien P. J.; Elahipanah S.; Yousaf M. N. Scaffold Free Bio-orthogonal Assembly of 3-Dimensional Cardiac Tissue via Cell Surface Engineering. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39806. 10.1038/srep39806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozhnikov D.; Luo W.; Elahipanah S.; O’Brien P. J.; Yousaf M. N. Generation of a Scaffold-Free Three-Dimensional Liver Tissue via a Rapid Cell-to-Cell Click Assembly Process. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27, 1991–1998. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim E.; Kim T.; Paik S.; Haam S.; Huh Y.; Lee K. Nanomaterials for Theranostics: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 327–394. 10.1021/cr300213b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang H. Y.; Hofree M.; Ideker T. A Decade of Systems Biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 26, 721–744. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil D. N.; Smith E. L.; Brentjens R. J.; Wolchok J. D. The future of cancer treatment: immunomodulation, CARs and combination immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 273–290. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander J. D.; Joung J. K. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 347–355. 10.1038/nbt.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R.; Greene E. L.; Collinsworth G.; Grewal J. S.; Houghton O.; Zeng H.; Garnovskaya M.; Paul R. V.; Raymond J. R. Enrichment of transiently transfected mesangial cells by cell sorting after cotransfection with GFP. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan E. E.; Dean D. A. Intracellular Trafficking of plasmids during transfection is mediated by microtubules. Mol. Ther. 2006, 13, 422–428. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]