Abstract

Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences and regulate expression of genes. The molecular and genetic mechanisms in most patients with inherited platelet defects are unknown. There is now increasing evidence that mutations in hematopoietic TFs are an important underlying cause for defects in platelet production, morphology, and function. The hematopoietic TFs implicated in patients with impaired platelet function and number include runt-related transcription factor 1, Fli-1 proto-oncogene, E-twenty-six (ETS) transcription factor (friend leukemia integration 1), GATA-binding protein 1, growth factor independent 1B transcriptional repressor, ETS variant 6, ecotropic viral integration site 1, and homeobox A11. These TFs act in a combinatorial manner to bind sequence-specific DNA within promoter regions to regulate lineage-specific gene expression, either as activators or repressors. TF mutations induce rippling downstream effects by simultaneously altering the expression of multiple genes. Mutations involving these TFs affect diverse aspects of megakaryocyte biology, and platelet production and function, culminating in thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction. Some are associated with predisposition to hematologic malignancies. These TF variants may occur more frequently in patients with inherited platelet defects than generally appreciated. This review focuses on alterations in hematopoietic TFs in the pathobiology of inherited platelet defects.

Introduction

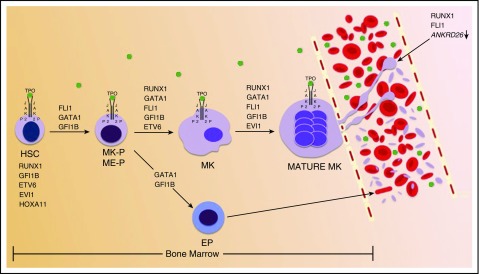

The complex process of platelet production starts with hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation and megakaryocyte (MK) lineage commitment, followed by MK maturation and eventual platelet release.1 These processes are temporally and spatially regulated by hematopoietic transcription factors (TFs) and stimulated by thrombopoietin1 (TPO) (Figure 1). TFs are proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences and regulate expression of genes. They function in a combinatorial manner as activators and repressors.2,3 There is increasing evidence that mutations in hematopoietic TFs are an important underlying cause of inherited defects in platelet production, structure, and function. TF mutations can induce multiple effects by concurrently altering expression of numerous target genes. Several hematopoietic TFs have been implicated in platelet disorders and include RUNX1, FLI1, GATA1, GFI1B, ETV6, EVI1, and HOXA11 (Table 1). These are described in this review. They regulate processes involved in MK lineage commitment and maturation and platelet biogenesis.4,5

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of hematopoietic TFs involved in normal platelet genesis. RUNX1, GFI1B, ETV6, EVI1, and HOXA11 are expressed in HSCs. As denoted above black arrows, various hematopoietic TFs, in combination with TPO stimulation, function to promote HSC differentiation, MK lineage commitment and maturation, and proplatelet formation and platelet release. Proplatelet formation and platelet release are also driven by RUNX1 and FLI1 silencing of ANKRD26. TPO is shown by green dots. EP, erythroid progenitor; ETS, E-twenty-six; ETV6, ETS variant 6; EVI1, ecotropic viral integration site 1; FLI1, Fli-1 proto-oncogene, ETS transcription factor; GATA1, GATA-binding protein 1; GF1IB, growth factor independent 1B transcriptional repressor; HOXA11, homeobox A11; ME-P, MK-erythroid progenitor; MK-P, MK progenitor; P, phosphorylated; RUNX1, runt-related transcription factor 1.

Table 1.

Hematopoietic TF mutations and platelet defects

| TF | Chromosome location | Selected gene targets | Platelet dysfunction* | Associated hematologic abnormalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUNX1 | 21q22.3 | ALOX12, PF4, MYL9, PRKCQ, MPL, MYH9, MYH10, NFE2, PCTP, PLDN, ANKRD26 | Yes | Increased risk of MDS/AML |

| FLI1 | 11q24.1-24.3 | ITGA2B, GP1BA, GP6, GP9, MPL, PF4, NFE2, RAB27B, ANKRD26 | Yes | Unknown |

| GATA1 | Xp11.23 | GP1BA, GP1BB, ITGA2B, GP9, PF4, MPL, NFE2 | Yes | Dyserythropoiesis |

| GFI1B | 9q34.13 | BCLXL, SOCS1, SOCS3, CDKN1A, GATA3, MEIS1, RAG1/2 | Yes | Red cell aniso/poikilocytosis |

| ETV6 | 12p13 | PF4 | Unknown | Dyserythropoiesis; Increased risk of ALL |

| EVI1 | 3q26.12 | RBM8A, MPL, ITGA2B, ITGB3 | Unknown | BM failure |

| HOXA11 | 7p15.2 | Unknown | BM failure |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ALOX12, 12-lipoxygenase; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MYL9, platelet myosin light chain; PCTP, phosphatidylcholine transfer protein; PF4, platelet factor 4; PLDN, pallidin; PRKCQ, protein kinase C-θ.

All of the TF mutations have been associated with variable thrombocytopenia. Platelet count may be normal, as seen in some patients with mutations in RUNX1 or FLI1. Thrombocytopenia may be particularly severe in patients with mutations in GATA1, ETV6, EVI1, and HOXA11 (platelet count <20 × 109/L). Abnormalities in platelet morphology, especially in AGs and DGs, and in aggregation and secretion responses on platelet activation have been described in association with mutations in RUNX1, FLI1, GATA1, and GFI1B. These abnormalities are described in the text and, for RUNX1, shown in Figure 2.

Some patients previously described with platelet defects, such as storage pool deficiency and other abnormalities, have more recently turned out to have mutations in specific TFs.6-10 In 1969, Weiss et al described a family with an autosomal dominant inherited platelet disorder due to decreased dense granule (DG) contents.11 This family was subsequently found to also have partial α-granule (AG) deficiency,12 and in 2002 reported to have a heterozygous Y260X mutation in RUNX1.6 Similarly, an underlying TF variant has been found in other patients.7,9,10,13 These studies advance a paradigm shift regarding the genetic basis of inherited platelet defects from mutations in candidate genes, based on the altered platelet phenotype to mutations in TFs that concurrently dysregulate diverse genes and pathways to impact platelet number and function. Moreover, the same platelet phenotype may result from mutations in more than one TF or mechanisms. For example, AG deficiencies are associated with mutations in RUNX1,6,10,14 GATA1,13 and GFI1B,7,9 in addition to NBEAL2.15

The advent of state-of-the art approaches, such as the next-generation sequencing (NGS), has augmented the discovery of TF mutations.8,10,16 It is emerging that TF mutations may be the genetic basis of platelet defects more commonly than generally considered. For example, Stockley et al8 found RUNX1 or FLI1 mutations in 6 of 13 index patients with clinical bleeding and impaired platelet aggregation and DG secretion studied with NGS; this has also been observed in other studies.7,10 Some TF mutations are associated with concurrent defects in erythropoiesis (eg, GATA1) or an increased risk of hematologic malignancy (RUNX1, ETV6) with implications for prognosis and management.3,17-20 Germ line alterations in hematopoietic TFs therefore need to be considered in the pathogenesis of inherited platelet defects.

RUNX1

RUNX1, also known as core-binding factor subunit α-2 (CBFA2) or AML1, is encoded by the RUNX1 gene on chromosome 21q22.3. It is a member of the Runt family of three TFs that share a 128 amino acid (aa) conserved runt homology domain near the N-terminus; this domain associates with its co-factor, CBFβ and binds to sequence-specific DNA to regulate gene expression.21 RUNX1 is indispensible for definitive hematopoiesis. RUNX1 knockout mice lack primary hematopoiesis during embryogenesis and die in utero because of bleeding.22 Conditional RUNX1 knockouts in mouse models show impaired MK maturation, with presence of abnormal micro-MKs and significant reduction in MK polyploidization.23 In patients with RUNX1 mutations, MKs cultured from stem cells also demonstrate defects in differentiation and polyploidization.17,24 This has been associated with dysregulated nonmuscle myosin IIA (MYH9) and IIB (MYH10) expression, with impaired MYH10 silencing and reduced MYL9 and MYH9 expression.24 Reconstitution of MYH10 silencing promotes MK polyploidization by allowing progression from mitosis to endomitosis (chromosome replication without cell division).24,25 Detection of platelet MYH10 protein expression has been proposed as a marker for genetic defect in RUNX1 and FLI1.26 RUNX1 regulates expression of numerous genes and pathways in MK/platelet genes.27,28 Platelet transcript profiling of a patient with heterozygous RUNX1 mutation showed downregulation of MK/platelet genes involved in diverse aspects of platelet production, structure, signaling, and function.28

Mutations in RUNX1 are associated with thrombocytopenia, impaired platelet function, and a predisposition to acute leukemia. In 1985, Dowton et al29 described a kindred of 22 members with a bleeding tendency, autosomal dominant thrombocytopenia and impaired platelet aggregation responses; 6 family members developed hematologic malignancies, including leukemia in 4 patients. Through this and other reports,29-31 this entity came to be referred to as familial platelet disorder with predisposition to AML (Mendelian Inheritance of Man [MIM] 601399). Linkage analysis of patients with familial platelet disorder/AML mapped a potential locus to the long arm of chromosome 21q22.31,32 In 1999, Song et al17 identified heterozygous mutations in RUNX1 (formerly CBFA2) in affected members of 6 families to establish the causal link, subsequently shown in several other families.6,33

Several families with RUNX1 mutations have been reported and this disorder is likely under-recognized in patients with platelet defects. Most mutations are within the conserved runt domain with decreased RUNX1 binding to the target DNA,6 although a mutation in the transactivating domain near the C-terminus has also been reported.6 The mutations usually result in haplodeficiency, but in some patients there is markedly decreased RUNX1 activity due to a dominant negative effect.6,34 Notably, the human phenotype is not recapitulated in murine heterozygous RUNX1 mutations.35 Patients with RUNX1 mutations typically have a mild-to-moderate bleeding tendency due to the platelet dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, with normal-sized platelets; some patients may not have thrombocytopenia or bleeding symptoms.8,36,37

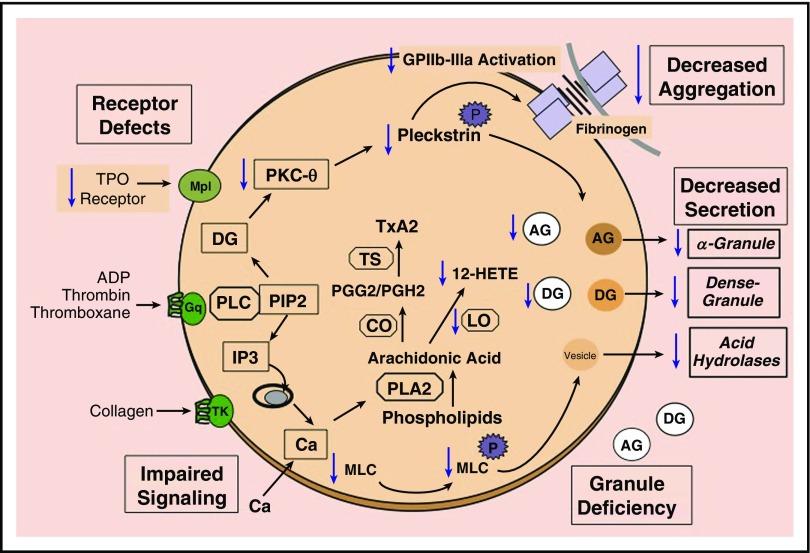

Platelet function abnormalities described in RUNX1 haplodeficiency include impaired platelet aggregation and secretion upon activation, DG and/or AG deficiency, and decreased phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC) and pleckstrin, activation of αIIbβ3, production of 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (a product of ALOX12), and protein kinase C-θ (which phosphorylates pleckstrin and other proteins) (Figure 2).6,15,24,38,39 Deficiencies of DG or AG or of both granules have been reported, although not all studies examined both granule subsets. Platelet albumin and immunoglobulin G, two AG proteins not synthesized by MKs, were also reduced in 1 patient, suggesting a defect in platelet uptake and incorporation into granules.38 Decreased expression of platelet PLDN has been observed in RUNX1 haplodeficiency and PLDN is a direct transcriptional target of RUNX1.40 This provides a potential mechanism for the DG deficiency because PLDN is involved in DG biogenesis, as observed in the pallid mouse and human Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome.41,42 Moreover, patients with RUNX1 mutations have defects in mechanisms that regulate agonist-stimulated secretion from AGs and DGs, as well as of the acid hydrolase containing vesicles, unrelated to a deficiency of granule contents.8,43-45 Overall, the impaired secretion is related to abnormalities in granule biogenesis, as well as in secretory mechanisms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of selected platelet responses to activation and platelet function abnormalities associated with RUNX1 mutations. Platelet receptor activation results in the formation of intracellular mediators that regulate the end responses, such as aggregation and secretion from AGs and DGs, and from vesicles bearing acid hydrolases. Receptor activation leads to hydrolysis of PIP2 by phospholipase C to form diacylglycerol, which activates protein kinase C, and IP3, which mediates the rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. Protein kinase C phosphorylates numerous proteins including pleckstrin. The increase in Ca2+ levels leads to other responses, such as activation of MYC kinase to phosphorylate MLC and activation of PLA2, which mediates the release of free arachidonic acid from phospholipids. Arachidonic acid is converted by CO and TS to thromboxane A2. Numerous defects in platelet function have been described in platelets with RUNX1 haplodeficiency. These are shown with downward arrows (blue). Included below in this legend in parenthesis are some of the relevant genes that are RUNX1 targets and downregulated in RUNX1 haplodeficiency. The abnormalities include reduction in the surface receptors for TPO (MPL); defects in signaling mechanisms, including impaired pleckstrin and MLC phosphorylation, and decreased PRKCQ and MLC (MYL9); decreased ALOX12 and 12-HETE production; impaired activation of GPIIb-IIIa and aggregation on platelet activation; DG (PLDN) and AG (PF4) deficiency; and impaired secretion of AG and DG contents and from vesicles containing acid hydrolases. Other genes shown to be downregulated and not shown in the figure include PCTP and NFE2. 12-HETE, 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; ADP, adenosine 5′-diphosphate; CO, cyclooxygenase; IP3, inositoltrisphosphate; LO, lipoxygenase; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PGG2, prostaglandin G2; PGH2, prostaglandin H2; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; TS, thromboxane synthase; TxA2, thromboxane A2.

A relatively small number of TFs in the genome regulate tissue-specific expression of a large number of genes.5 Thus, multiple defects observed in MKs and platelets arise due to dysregulation of numerous RUNX1 target genes. Our platelet transcript profiling studies of a patient with RUNX1 haplodeficiency showed that genes regulating several platelet pathways were downregulated.28 Some have been shown to be direct transcriptional targets of RUNX1, including ALOX12,39 PF4,14 MYL9,46 PRKCQ,47 PLDN,40 and the TPO receptor (MPL).48 Another gene downregulated and a target of RUNX1 is PCTP,49 which encodes for a protein implicated in platelet responses mediated by PAR4 agonist activation.50 TF NF-E2 (NFE2) is also a transcriptional target of RUNX1.51 NF-E2 has been implicated in platelet granule development and αIIbβ3 signaling.51 These alterations impact various aspects of MK and platelet biology.

Recently, Connelly et al52 have validated the causative role of RUNX1 mutations and advanced the potential for gene therapy. Using induced pluripotent stem cells from skin fibroblasts of 2 patients with RUNX1 Y260X mutation, they demonstrated impaired MK production and abnormalities including the presence of vacuoles and reduction in AGs and DGs. Targeted in vitro mutation correction rescued the defects in MK production and phenotype, with upregulation of relevant MK genes.

RUNX1 haplodeficiency is associated with increased risk of AML or MDS, with a >40% risk at a median age of 33 years.36 The malignant transformation is heralded by the development of additional somatic mutations in genes, such as CDC25C, GATA2, TET2, MLL2, and RB1.53,54 The level of RUNX1 activity appears to be important in predisposing to leukemic predisposition.34 Relevant to note, acquired RUNX1 mutations are common in patients with MDS and myeloid malignancies.55 Sporadic germ line deletions involving chromosome 21q22 that include the RUNX1 gene have also been reported, and may result in syndromic features (dysmorphic facies, mental retardation, and organ abnormalities) and predisposition to hematologic malignancies.36

Recognition of RUNX1 and other mutations is important to prevent unnecessary therapies, such as based on an erroneous diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenic purpura. In patients with RUNX1 mutations who develop MDS or leukemia, use of an undiagnosed RUNX1 haplodeficient sibling donor has been associated with recurrence of leukemia.37 It has been suggested that patients undergo surveillance for MDS and leukemia with clinical examination and blood counts every 6 to 12 months.56

FLI1

The FLI1 gene is located on the distal end of the long-arm of chromosome 11 (11q24.1-q24.3) and is a member of the ETS family of TFs.57,58 It has 452 aas, and shares with other ETS family members a winged helix-turn-helix ETS domain of 85 aas that recognizes DNA consensus sequence 5′-GGAA/T-3′.58 FLI1 plays critical roles in megakaryopoiesis and angiogenesis.3 FLI1 knockout mice die of embryonic hemorrhage, attributed to the FLI1 role in both megakaryopoiesis and endothelium, and hemangioblast specification.3 Murine heterozygous FLI1 mutation does not recapitulate the human hematologic phenotype.59 FLI1 transcriptionally binds and regulates a number of MK/platelet relevant genes, including for ITGA2B, GP1BA, GP9, THPO, and PF4.3

Hemizygous FLI1 defects occur due to distal deletion of part of the long-arm of chromosome 11 and are associated with Jacobsen syndrome (MIM 147791), and the associated platelet disorder, Paris-Trousseau syndrome (PTS) (MIM 188025). Most cases of Jacobsen syndrome occur from de novo mutation in a parental gamete, with the rest from translocations or chromosomal rearrangement abnormalities that lead to loss of distal chromosome 11 material.60 Patients with Jacobsen syndrome may have dysmorphic facies, developmental delay, and multiple organ abnormalities (eg, cardiac, renal and genitourinary, neurologic, and hematologic).61 More than 90% of patients with Jacobsen syndrome also have PTS, attributed to deletion of FLI1. Such patients have variable bleeding tendency, congenital macrothrombocytopenia, and platelet dysfunction with impaired AG and DG secretion in response to thrombin.8,59,62 A characteristic feature is the presence of giant AGs (1 to 2 μm) in 1% to 5% of platelets.59,62 There is dysmegakaryopoiesis with increased MKs in the bone marrow (BM).59 The MK population is dimorphic, one normal and one with small immature MKs, due to transient monoallelic FLI1 expression in progenitors.62,63 Interestingly, the platelet count in children with Jacobsen syndrome/PTS may spontaneously improve over months to years.60

Recent studies using NGS have uncovered novel FLI1 variants in patients with platelet dysfunction. Stockley et al8 identified FLI1 mutations (3 missense and 1 4-bp deletion) in 3 of 13 unrelated index patients with excessive bleeding, and decreased platelet aggregation and reduced DG secretion. Additionally, Stevenson et al59 reported on 2 patients with a PTS phenotype due to homozygous FLI1 missense mutations inherited from consanguineous parents and predicted to alter the ETS DNA binding domain. The parents had normal a platelet count and function, indicating that the mechanisms by which FLI1 variants lead to platelet defects remain to be fully elucidated.

GATA1

GATA1 is a zinc finger TF encoded by the GATA1 gene located on the short-arm of the X-chromosome (Xp11.23). It is member of a family of TFs that bind to the GATA motif of DNA.5 GATA1 has 2 homologous zinc fingers: the N-terminal finger, which associates with a nuclear co-factor protein called friend of GATA1 (FOG1) to enhance stability of GATA1 binding to complex or palindromic DNA binding sites, and the C-terminal zinc finger that mediates binding to the GATA DNA motif.64,65 GATA1 is critical in both megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis.3,5 It is highly expressed in MKs and erythroid cells, as well as mast cells and eosinophils, and is indispensable for terminal differentiation of these lineages.3,5,64,65 GATA1 knockout mice die in utero at approximately day 10 from severe anemia.3 A wide spectrum of MK genes contain GATA1 motifs within their cis-regulatory domain, including GP1BA, GP1BB, ITGA2B, GP9, PF4, THPO, and NFE2.65,66

Several families have been described with X-linked platelet and red cell disorders associated with distinct GATA1 variants (Table 2). The initial reports described families with macrothrombocytopenia and dyserythropoiesis with or without anemia (MIM 300367), with severity of anemia dependent on the extent of disruption of GATA1 interaction with FOG1. In one pedigree,67 2 boys had severe fetal anemia and thrombocytopenia requiring in utero red cell and platelet transfusions. Both children underwent HSC transplant (HSCT). Genetic analysis revealed GATA1 V205M mutation that markedly impaired GATA1 interaction with FOG1. In another family65 with severe dyserythropoietic anemia and thrombocytopenia, 6 affected boys died before age 2. The family had GATA1 D218Y mutation, which conferred a similar degree of impairment in GATA1/FOG1 interaction as with GATA1 V205M mutation. Mutations with less severe alterations in GATA1/FOG1 affinity (GATA1 D218G, G208S, G208R) also manifest with thrombocytopenia, but are only mildly affected by red cell abnormalities, with dyserythropoiesis, but without significant anemia.66,68,69

Table 2.

Platelet disorders associated with GATA1 mutations

| Clinical disorder | Genetic mutation | Extent of disruption of GATA1/FOG1 interaction | Degree of anemia | Degree of thrombocytopenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenia ± dyserythropoietic anemia (MIM 300367) | V205M | Severe | ++ | ++/+++ |

| D218Y | Severe | ++ | +++ | |

| D218G | Mild | − | +/++/+++ | |

| G208S | Mild | − | ++ | |

| G208R | Unknown | ++ | +++ | |

| Thrombocytopenia with β-thalassemia (MIM 314050) | R216Q | − (disrupts DNA binding) | ± | + and GPS |

| Macrocytic anemia; neutropenia; normal platelet count (MIM 300835) | Splice mutation 332G->C, V74L | − | +/++/+++ (many cases also with neutropenia) | − |

| Dyserythropoietic anemia; MK dysplasia; thrombocytosis | Splice mutation in 5′-untranslated region | − | +++ (occasional neutropenia) | − |

Anemia: hemoglobin (Hb) ≥10 g/dL (+); Hb 7 to <10 g/dL (++); and Hb <7 g/dL (+++).

Thrombocytopenia: 70 000 to 90 000 × 109/L (+); ≥20 000 to <70 000 × 109/L (++); and <20 000 × 109/L (+++).

GPS, Gray platelet syndrome.

GATA1 mutations have also been implicated in X-linked thrombocytopenia with β-thalassemia (MIM 314050), as first described in 1977.70 These patients had moderate macrothrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, AG deficiency, imbalanced globin chain synthesis, red cell hemolysis, and evidence of dyserythropoiesis and dysmegakaryopoiesis.64,70,71 GATA1 R216Q mutation identified in these patients is unique in that, unlike other previously described GATA1 mutations, GATA1/FOG1 interaction is not disrupted; rather, there is impaired binding of the GATA1 N-finger to complex or palindromic DNA sequences.64,71 Subsequently, a family with the GPS was also found to have GATA1 R216Q mutation; one member displayed a mild β-thalassemia–like phenotype.13

Individuals with GATA1 mutations have shown reduced platelet aggregation in response to collagen and decreased agglutination with ristocetin, consistent with reduced expression of GPVI and GPIb-IX-V complex, respectively.66,72 One study showed decreased platelet guanosine 5′-triphosphate binding protein GαS (GNAS) expression.66 Platelet life span in these patients appears to be normal.66 In patients with significant bleeding from thrombocytopenia and/or platelet dysfunction, HSCT or genetic therapy has been proposed.68

More recently, families with GATA1 splice mutations have been described.73,74 Affected individuals had normal or elevated platelet counts with evidence of platelet dysfunction. For example, a family73 with macrocytic anemia and neutropenia (X-linked anemia with or without neutropenia and/or platelet abnormalities [MIM 300835]) was found to have a germ line GATA1 splice mutation (332G- > C,V74L), which leads to production of only short GATA1 protein isoforms. Platelet studies demonstrated impaired platelet aggregation upon activation with adenosine 5′-diphosphate, epinephrine, and collagen; AGs and DGs were decreased. Another report74 described a child with dyserythropoietic anemia, MK dysplasia, and thrombocytosis, with a splice mutation in the GATA1 5′-untranslated region that also resulted in short GATA1 protein isoforms. Platelet aggregation in response to arachidonic acid was decreased, although the child did not have bleeding symptoms.

GFI1B

GFI1B, a zinc finger TF encoded by the GFI1B gene, is located on the long-arm of chromosome 9 (9q34.13) and has 3 domains: an N-terminal repressor “SNAG” (SNAIL/GFI1) domain where epigenetic modifiers are recruited, a less well characterized middle domain, and a C-terminal DNA binding domain. The C-terminal domain contains 6 zinc fingers; zinc fingers 3 to 5 mediate DNA binding, whereas the remaining interact with other proteins.9 GFI1B functions as a transcriptional repressor and utilizes epigenetic processes to modulate the chromatin structure of the target gene.75

GFI1B is essential for both megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis and is expressed in HSCs, ME-Ps, and during maturation of erythroid cells and MKs.75 Regulation of transforming growth factor β signaling by GFI1B controls lineage-specific differentiation from ME-Ps.75-77 GFI1B knockout mice die at approximately embryonic day 15, likely due to both defective megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis.78 Known GFI1B transcriptional targets include BCLXL, SOCS1, SOCS3, CDKN1A, GATA3, MEIS1, and RAG1/2.75

GFI1B has been linked to platelet disorders relatively recently. In 2013, a family initially described in 197679 with autosomal dominant mild-to-moderate macrothrombocytopenia, red cell anisopoikilocytosis, AG deficiency, and platelet dysfunction, was shown to have a single nucleotide insertion in exon 7 of GFI1B (c.880-881insC).7 The variant predicted a frameshift affecting the fifth zinc finger of GFI1B, in the DNA binding domain.7 A second family with GPS phenotype and autosomal dominant GFI1B mutation was described shortly after.9 This family, initially described in 1968,80 was found to have a nonsense mutation in exon 6 of GFI1B (c.859C → T, p. Gln287*), which produces a truncated GFI1B protein without 44 C-terminal amino acids), including 4 aas within the fifth zinc finger DNA-binding domain.9 Functional studies were consistent with a dominant negative effect exerted by mutant GFI1B protein.9 Subsequently, 8 additional patients with GFI1B mutations (7 distinct variants) have been identified, with mutations being biallelic in 1 patient.76 These patients were identified by NGS during evaluation for inherited platelet dysfunction. Another family has been reported81 with a GFI1B mutation and phenotype similar to the first two described families.

Patients with GFI1B mutation have mild-to-moderate macrothrombocytopenia with variable bleeding tendency.7,9 Studies in one family showed impaired platelet aggregation in response to multiple agonists; response to collagen was impaired in all.7 Affected patients had reduced platelet expression of GPIbα and GPIIIa.7,9 Platelet AG contents were reduced.7,9 BM biopsy of an affected patient showed fibrosis and emperipolesis, with neutrophils within MKs.9 MKs generated ex vivo from 2 patients displayed dysplastic features.9 GFI1B mutation is associated with abnormal proplatelet formation and increased MK/platelet CD34 expression.9,81

ETV6

ETV6, also known as translocation-Ets leukemia is encoded by the ETV6 gene located on chromosome 12p13, and is a member of the ETS family. ETV6 has 452 aas that form a 57-KDa protein with 3 functional domains that include the pointed N-terminal, central regulatory, and C-terminal DNA binding domains.82 The C-terminal DNA binding domain contains the highly conserved ETS domain that recognizes the consensus DNA sequence 5-GGAA/T-3 within a 9- to 10-bp sequence.82 ETV6 functions as a transcriptional repressor and its activity is modulated through self-association and autoregulation, with the former occurring at the pointed N-terminal domain. ETV6 polymerization appears to increase the DNA binding affinity of the C-terminal domain.82 The central regulatory domain is important for ETV6 to fully exert transcriptional repression.18 ETV6 interacts with numerous binding partners, including FLI1, whereby it inhibits FLI1 transcriptional activity.83

ETV6 plays critical roles in hematopoiesis and vascular network maintenance.84,85 In mice, complete ETV6 knockout leads to embryonic lethality at day 10.5 to 11.5 with evidence of impaired yolk sac angiogenesis, and apoptosis of neural and mesenchymal cells.84 ETV6 is required for maintenance of hematopoiesis in the BM through supporting survival of HSCs, but is not strictly required for earlier hematopoiesis in the yolk sac or liver.84,85 ETV6 is also important in terminal maturation of MKs. Conditional ETV6 homozygous knockout mice had an ∼50% reduction in platelet count compared with heterozygous mutant mice, with an approximate fivefold compensatory elevation in MK-Ps.85

Heterozygous ETV6 germ line mutations have been identified in several families with inherited thrombocytopenia, variable red cell macrocytosis, and multiple members with hematologic malignancies, primarily B-cell ALL.18-20 Functional studies demonstrated impaired ETV6 nuclear localization, decreased transcriptional repression through a dominant negative mechanism, and defects in MK maturation.18-20 Germ line ETV6 mutations have been implicated in ∼1% of childhood ALL patients.86

Patients with heterozygous germ line ETV6 mutations have variable thrombocytopenia, with platelet count ranging from 8 to 132 000 × 109/L.18,20 Platelet ultrastructure and mean volume are normal with the presence of a few elongated AGs.18 It is unknown if platelet function is impaired in these patients. BM studies show the presence of hypolobulated MKs and mild dyserythropoiesis,18

EVI1

EVI1 is encoded by the MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus (MECOM) gene located on chromosome 3 (3q26.2).5,87 EVI1 is a zinc finger TF; the N-terminal domain has 5 zinc fingers that recognize a GATA-like motif and a C-terminal domain that consists of 3 zinc fingers that recognize an ETS-like motif.87 Through the C-terminal eighth zinc finger, EVI1 interacts with itself and other TFs, including RUNX1 and GATA1 (as well as SPI1, SMAD3, and FOS).87 EVI1 is expressed in HSCs, MKs, and platelets5 and is essential for HSC self renewal.88 EVI1 knockout mice die in utero at approximately day 10.5, with evidence of bleeding, hypocellularity, and paraxial mesenchyme disruption.89 In conditional EVI1 knockout mice, there is loss of HSC renewal, although HSC differentiation is preserved.89 In cell lines, EVI1 knockdown has been demonstrated to impair MK differentiation with reduction in ITGA2B and ITGB3 expression.5 EVI1 downregulates the TPO receptor (MPL).90

Mutations in MECOM with alteration of the EVI1 protein have been implicated in the congenital disorder radioulnar synostosis and amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (RUSAT).87 Earlier candidate gene analysis in 2 unrelated families with RUSAT91,92 associated heterozygous mutations in HOXA11, which encodes a TF implicated in bone morphogenesis and MK differentiation. However, several individuals have been reported with RUSAT but without a HOXA11 mutation.87 Three such individuals were found to carry missense variants in MECOM.87 The mutations are located within the eighth zinc finger of EVI1, and postulated to attenuate target DNA binding and/or decrease EVI1 interaction with self or other regulatory proteins.87

Patients with RUSAT are characterized by congenital fusion of the proximal radius, and ulna and severe thrombocytopenia (<10 × 109/L).87,91,93 MKs are markedly decreased or absent in the BM.93 Affected patients often develop BM failure, and several have been treated with HSCT. Interestingly, 3 individuals with RUSAT had sensorineural hearing impairment (1 with HOXA11 and 2 with MECOM mutations).87 Congenital deletion of part of chromosome 3q26 has also been reported; affected infants had thrombocytopenia, with 1 child developing aplastic anemia.94,95

EVI1 has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of another congenital platelet disorder, the thrombocytopenia with absent radii (TAR) syndrome. The thrombocytopenia may be transient and improve over time.93 Most TAR syndrome patients are thought to be from compound inheritance, with mutation of the RBM8A gene on one allele and mutation of an EVI1 regulatory region of the RBM8A gene on the other allele.96 The latter results in decreased RBM8A transcription and production of the gene product, Y14. The risk of familial malignancy with MECOM mutations is unknown, although individuals with severe thrombocytopenia and/or BM failure often undergo HSCT at a young age. High expression of MECOM is implicated in 5% to 10% of sporadic AML patients and is an adverse prognostic marker.87 In leukemia cells, EVI1 disruption attenuates proliferation.89

Mutations in regulatory TF-binding sites

Apart from mutations in the genes encoding the TF, mutations in the regulatory TF-binding sites of transcriptional targets may also produce a clinical platelet disorder.97,98 One example is the heterozygous variants in the 5′-untranslated region of ANKRD26 associated with autosomal dominant thrombocytopenia.99,100 ANKRD26 encodes for an inner cell membrane protein that interacts with signaling proteins.97 The ANKRD26 variants abrogate binding of RUNX1 and FLI1, resulting in the loss of ANKRD26 silencing, hyperactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases pathway, and impaired proplatelet formation,97,99,100 Another example is a heterozygous missense mutation involving the GATA1-binding site in the promoter of GP1BB.98 The patient had velocardiofacial syndrome with already partial deletion of one chromosome 22 (including GP1BB) and decreased platelet GPIbβ expression.

Conclusion

There is growing evidence that mutations in hematopoietic TFs represent an important genetic mechanism for inherited platelet disorders. These may be more common than previously appreciated in such patients. This shifts the emphasis from searching for causal gene variants based on phenotype and candidate genes, to the perspective that the driving mutation may be in a TF that regulates multiple genes expressed in MKs/platelets. This recognition is important also because of additional implications associated with TF mutations, such as the risk of malignancy. Overall, these patients are a unique source of information into the genetic and molecular mechanisms governing MK and platelet biology.

Acknowledgments

The assistance of Denise Tierney in the preparation of the manuscript is gratefully acknowledged.

This study was supported by research funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL109568).

Authorship

Contribution: N.S. and A.K.R. co-wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: A. Koneti Rao, Sol Sherry Thrombosis Research Center, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, 3400 N. Broad St, 204 MRB, Philadelphia, PA 19140; e-mail: koneti@temple.edu.

References

- 1.Eto K, Kunishima S. Linkage between the mechanisms of thrombocytopenia and thrombopoiesis. Blood. 2016;127(10):1234-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tijssen MR, Cvejic A, Joshi A, et al. . Genome-wide analysis of simultaneous GATA1/2, RUNX1, FLI1, and SCL binding in megakaryocytes identifies hematopoietic regulators. Dev Cell. 2011;20(5):597-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doré LC, Crispino JD. Transcription factor networks in erythroid cell and megakaryocyte development. Blood. 2011;118(2):231-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabbolini DJ, Ward CM, Stevenson WS. Thrombocytopenia caused by inherited haematopoietic transcription factor mutation: clinical phenotypes and diagnostic considerations. EMJ Hematol. 2016;4(1):100-109. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tijssen MR, Ghevaert C. Transcription factors in late megakaryopoiesis and related platelet disorders. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(4):593-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaud J, Wu F, Osato M, et al. . In vitro analyses of known and novel RUNX1/AML1 mutations in dominant familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia: implications for mechanisms of pathogenesis. Blood. 2002;99(4):1364-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson WS, Morel-Kopp MC, Chen Q, et al. . GFI1B mutation causes a bleeding disorder with abnormal platelet function. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(11):2039-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockley J, Morgan NV, Bem D, et al. ; UK Genotyping and Phenotyping of Platelets Study Group. Enrichment of FLI1 and RUNX1 mutations in families with excessive bleeding and platelet dense granule secretion defects. Blood. 2013;122(25):4090-4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monteferrario D, Bolar NA, Marneth AE, et al. . A dominant-negative GFI1B mutation in the gray platelet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(3):245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simeoni I, Stephens JC, Hu F, et al. . A high-throughput sequencing test for diagnosing inherited bleeding, thrombotic, and platelet disorders. Blood. 2016;127(23):2791-2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss HJ, Chervenick PA, Zalusky R, Factor A. A familialdefect in platelet function associated with imapired release of adenosine diphosphate. N Engl J Med. 1969;281(23):1264-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss HJ, Witte LD, Kaplan KL, et al. . Heterogeneity in storage pool deficiency: studies on granule-bound substances in 18 patients including variants deficient in alpha-granules, platelet factor 4, beta-thromboglobulin, and platelet-derived growth factor. Blood. 1979;54(6):1296-1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tubman VN, Levine JE, Campagna DR, et al. . X-linked gray platelet syndrome due to a GATA1 Arg216Gln mutation. Blood. 2007;109(8):3297-3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aneja K, Jalagadugula G, Mao G, Singh A, Rao AK. Mechanism of platelet factor 4 (PF4) deficiency with RUNX1 haplodeficiency: RUNX1 is a transcriptional regulator of PF4. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(2):383-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao AK. Inherited platelet function disorders: overview and disorders of granules, secretion, and signal transduction. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(3):585-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lentaigne C, Freson K, Laffan MA, Turro E, Ouwehand WH; BRIDGE-BPD Consortium and the ThromboGenomics Consortium. Inherited platelet disorders: toward DNA-based diagnosis. Blood. 2016;127(23):2814-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song WJ, Sullivan MG, Legare RD, et al. . Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noetzli L, Lo RW, Lee-Sherick AB, et al. . Germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red cell macrocytosis and predisposition to lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):535-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang MY, Churpek JE, Keel SB, et al. . Germline ETV6 mutations in familial thrombocytopenia and hematologic malignancy. Nat Genet. 2015;47(2):180-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topka S, Vijai J, Walsh MF, et al. . Germline ETV6 mutations confer susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukemia and thrombocytopenia. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(6):e1005262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coffman JA. Runx transcription factors and the developmental balance between cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell Biol Int. 2003;27(4):315-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Q, Stacy T, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe AH, Speck NA. Disruption of the Cbfa2 gene causes necrosis and hemorrhaging in the central nervous system and blocks definitive hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3444-3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichikawa M, Asai T, Saito T, et al. . AML-1 is required for megakaryocytic maturation and lymphocytic differentiation, but not for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells in adult hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2004;10(3):299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bluteau D, Glembotsky AC, Raimbault A, et al. . Dysmegakaryopoiesis of FPD/AML pedigrees with constitutional RUNX1 mutations is linked to myosin II deregulated expression. Blood. 2012;120(13):2708-2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lordier L, Bluteau D, Jalil A, et al. . RUNX1-induced silencing of non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIB contributes to megakaryocyte polyploidization. Nat Commun. 2012;3:717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antony-Debré I, Bluteau D, Itzykson R, et al. . MYH10 protein expression in platelets as a biomarker of RUNX1 and FLI1 alterations. Blood. 2012;120(13):2719-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaud J, Simpson KM, Escher R, et al. . Integrative analysis of RUNX1 downstream pathways and target genes. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun L, Gorospe JR, Hoffman EP, Rao AK. Decreased platelet expression of myosin regulatory light chain polypeptide (MYL9) and other genes with platelet dysfunction and CBFA2/RUNX1 mutation: insights from platelet expression profiling. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(1):146-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowton SB, Beardsley D, Jamison D, Blattner S, Li FP. Studies of a familial platelet disorder. Blood. 1985;65(3):557-563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerrard JM, Israels ED, Bishop AJ, et al. . Inherited platelet-storage pool deficiency associated with a high incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1991;79(2):246-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho CY, Otterud B, Legare RD, et al. . Linkage of a familial platelet disorder with a propensity to develop myeloid malignancies to human chromosome 21q22.1-22.2. Blood. 1996;87(12):5218-5224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arepally G, Rebbeck TR, Song W, Gilliland G, Maris JM, Poncz M. Evidence for genetic homogeneity in a familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia (FPD/AML) [letter] Blood. 1998;92(7):2600-2602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preudhomme C, Warot-Loze D, Roumier C, et al. . High incidence of biallelic point mutations in the Runt domain of the AML1/PEBP2 alpha B gene in Mo acute myeloid leukemia and in myeloid malignancies with acquired trisomy 21. Blood. 2000;96(8):2862-2869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antony-Debré I, Manchev VT, Balayn N, et al. . Level of RUNX1 activity is critical for leukemic predisposition but not for thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2015;125(6):930-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun W, Downing JR. Haploinsufficiency of AML1 results in a decrease in the number of LTR-HSCs while simultaneously inducing an increase in more mature progenitors. Blood. 2004;104(12):3565-3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liew E, Owen C. Familial myelodysplastic syndromes: a review of the literature. Haematologica. 2011;96(10):1536-1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owen CJ, Toze CL, Koochin A, et al. . Five new pedigrees with inherited RUNX1 mutations causing familial platelet disorder with propensity to myeloid malignancy. Blood. 2008;112(12):4639-4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun L, Mao G, Rao AK. Association of CBFA2 mutation with decreased platelet PKC-theta and impaired receptor-mediated activation of GPIIb-IIIa and pleckstrin phosphorylation: proteins regulated by CBFA2 play a role in GPIIb-IIIa activation. Blood. 2004;103(3):948-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaur G, Jalagadugula G, Mao G, Rao AK. RUNX1/core binding factor A2 regulates platelet 12-lipoxygenase gene (ALOX12): studies in human RUNX1 haplodeficiency. Blood. 2010;115(15):3128-3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao GF, Goldfinger LE, Fan DC, et al. . Dysregulation of PLDN (pallidin) is a mechanism for platelet dense granule deficiency in RUNX1 haplodeficiency. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(4):792-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang L, Kuo YM, Gitschier J. The pallid gene encodes a novel, syntaxin 13-interacting protein involved in platelet storage pool deficiency. Nat Genet. 1999;23(3):329-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cullinane AR, Curry JA, Carmona-Rivera C, et al. . A BLOC-1 mutation screen reveals that PLDN is mutated in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 9. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(6):778-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43.Rao AK. Spotlight on FLI1, RUNX1, and platelet dysfunction. Blood. 2013;122(25):4004-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabbeta J, Yang X, Sun L, McLane MA, Niewiarowski S, Rao AK. Abnormal inside-out signal transduction-dependent activation of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa in a patient with impaired pleckstrin phosphorylation. Blood. 1996;87(4):1368-1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao AK, Poncz M. Defective platelet secretory mechanisms in familial thrombocytopenia with transcription factor CBFA2 haplodeficiency [abstract]. Thromb Hemostas. 2001. Abstract #OC91.

- 46.Jalagadugula G, Mao G, Kaur G, Goldfinger LE, Dhanasekaran DN, Rao AK. Regulation of platelet myosin light chain (MYL9) by RUNX1: implications for thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction in RUNX1 haplodeficiency. Blood. 2010;116(26):6037-6045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jalagadugula G, Mao G, Kaur G, Dhanasekaran DN, Rao AK. Platelet protein kinase Ctheta deficiency with human RUNX1 mutation: PRKCQ is a transcriptional target of RUNX1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(4):921-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heller PG, Glembotsky AC, Gandhi MJ, et al. . Low Mpl receptor expression in a pedigree with familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia and a novel AML1 mutation. Blood. 2005;105(12):4664-4670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Songdej N, Mao G, Voora D, et al. . PCTP (phosphatidylcholine transfer protein) is regulated by RUNX1 in platelets/megakaryocytes and is associated with adverse cardiovascular events [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128(22). Abstract 365. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edelstein LC, Simon LM, Montoya RT, et al. . Racial differences in human platelet PAR4 reactivity reflect expression of PCTP and miR-376c. Nat Med. 2013;19(12):1609-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glembotsky AC, Bluteau D, Espasandin YR, et al. . Mechanisms underlying platelet function defect in a pedigree with familial platelet disorder with a predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia: potential role for candidate RUNX1 targets. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(5):761-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Connelly JP, Kwon EM, Gao Y, et al. . Targeted correction of RUNX1 mutation in FPD patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells rescues megakaryopoietic defects. Blood. 2014;124(12):1926-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshimi A, Toya T, Kawazu M, et al. . Recurrent CDC25C mutations drive malignant transformation in FPD/AML. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakurai M, Kasahara H, Yoshida K, et al. . Genetic basis of myeloid transformation in familial platelet disorder/acute myeloid leukemia patients with haploinsufficient RUNX1 allele. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Behrens K, Triviai I, Schwieger M, et al. . Runx1 downregulates stem cell and megakaryocytic transcription programs that support niche interactions. Blood. 2016;127(26):3369-3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The University of Chicago Hematopoietic Malignancies Cancer Risk Team, Drazer MW, Feurstein S, et al. . How I diagnose and manage individuals at risk for inherited myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2016;128(14):1800-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hou C, Tsodikov OV. Structural basis for dimerization and DNA binding of transcription factor FLI1. Biochemistry. 2015;54(50):7365-7374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oh S, Shin S, Janknecht R. ETV1, 4 and 5: an oncogenic subfamily of ETS transcription factors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(1):1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stevenson WS, Rabbolini DJ, Beutler L, et al. . Paris-Trousseau thrombocytopenia is phenocopied by the autosomal recessive inheritance of a DNA-binding domain mutation in FLI1. Blood. 2015;126(17):2027-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Favier R, Jondeau K, Boutard P, et al. . Paris-Trousseau syndrome: clinical, hematological, molecular data of ten new cases. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(5):893-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jacobsen P, Hauge M, Henningsen K, Hobolth N, Mikkelsen M, Philip J. An (11;21) translocation in four generations with chromosome 11 abnormalities in the offspring. A clinical, cytogenetical, and gene marker study. Hum Hered. 1973;23(6):568-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Breton-Gorius J, Favier R, Guichard J, et al. . A new congenital dysmegakaryopoietic thrombocytopenia (Paris-Trousseau) associated with giant platelet alpha-granules and chromosome 11 deletion at 11q23. Blood. 1995;85(7):1805-1814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raslova H, Komura E, Le Couédic JP, et al. . FLI1 monoallelic expression combined with its hemizygous loss underlies Paris-Trousseau/Jacobsen thrombopenia. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(1):77-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu C, Niakan KK, Matsushita M, Stamatoyannopoulos G, Orkin SH, Raskind WH. X-linked thrombocytopenia with thalassemia from a mutation in the amino finger of GATA-1 affecting DNA binding rather than FOG-1 interaction. Blood. 2002;100(6):2040-2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freson K, Matthijs G, Thys C, et al. . Different substitutions at residue D218 of the X-linked transcription factor GATA1 lead to altered clinical severity of macrothrombocytopenia and anemia and are associated with variable skewed X inactivation. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(2):147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Freson K, Devriendt K, Matthijs G, et al. . Platelet characteristics in patients with X-linked macrothrombocytopenia because of a novel GATA1 mutation. Blood. 2001;98(1):85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nichols KE, Crispino JD, Poncz M, et al. . Familial dyserythropoietic anaemia and thrombocytopenia due to an inherited mutation in GATA1. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):266-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mehaffey MG, Newton AL, Gandhi MJ, Crossley M, Drachman JG. X-linked thrombocytopenia caused by a novel mutation of GATA-1. Blood. 2001;98(9):2681-2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Del Vecchio GC, Giordani L, De Santis A, De Mattia D. Dyserythropoietic anemia and thrombocytopenia due to a novel mutation in GATA-1. Acta Haematol. 2005;114(2):113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thompson AR, Wood WG, Stamatoyannopoulos G. X-linked syndrome of platelet dysfunction, thrombocytopenia, and imbalanced globin chain synthesis with hemolysis. Blood. 1977;50(2):303-316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Balduini CL, Pecci A, Loffredo G, et al. . Effects of the R216Q mutation of GATA-1 on erythropoiesis and megakaryocytopoiesis. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91(1):129-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hughan SC, Senis Y, Best D, et al. . Selective impairment of platelet activation to collagen in the absence of GATA1. Blood. 2005;105(11):4369-4376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hollanda LM, Lima CS, Cunha AF, et al. . An inherited mutation leading to production of only the short isoform of GATA-1 is associated with impaired erythropoiesis. Nat Genet. 2006;38(7):807-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zucker J, Temm C, Czader M, Nalepa G. A child with dyserythropoietic anemia and megakaryocyte dysplasia due to a novel 5'UTR GATA1s splice mutation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(5):917-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Möröy T, Vassen L, Wilkes B, Khandanpour C. From cytopenia to leukemia: the role of Gfi1 and Gfi1b in blood formation. Blood. 2015;126(24):2561-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen L, Kostadima M, Martens JH, et al. ; BRIDGE Consortium. Transcriptional diversity during lineage commitment of human blood progenitors. Science. 2014;345(6204):1251033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Randrianarison-Huetz V, Laurent B, Bardet V, Blobe GC, Huetz F, Duménil D. Gfi-1B controls human erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation by regulating TGF-beta signaling at the bipotent erythro-megakaryocytic progenitor stage. Blood. 2010;115(14):2784-2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saleque S, Cameron S, Orkin SH. The zinc-finger proto-oncogene Gfi-1b is essential for development of the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages. Genes Dev. 2002;16(3):301-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ardlie NG, Coupland WW, Schoefl GI. Hereditary thrombocytopathy: a familial bleeding disorder due to impaired platelet coagulant activity. Aust N Z J Med. 1976;6(1):37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kurstjens R, Bolt C, Vossen M, Haanen C. Familial thrombopathic thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 1968;15(3):305-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kitamura K, Okuno Y, Yoshida K, et al. . Functional characterization of a novel GFI1B mutation causing congenital macrothrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(7):1462-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Green SM, Coyne HJ III, McIntosh LP, Graves BJ. DNA binding by the ETS protein TEL (ETV6) is regulated by autoinhibition and self-association. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(24):18496-18504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kwiatkowski BA, Bastian LS, Bauer TR Jr, Tsai S, Zielinska-Kwiatkowska AG, Hickstein DD. The ets family member Tel binds to the Fli-1 oncoprotein and inhibits its transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(28):17525-17530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang LC, Kuo F, Fujiwara Y, Gilliland DG, Golub TR, Orkin SH. Yolk sac angiogenic defect and intra-embryonic apoptosis in mice lacking the Ets-related factor TEL. EMBO J. 1997;16(14):4374-4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hock H, Meade E, Medeiros S, et al. . Tel/Etv6 is an essential and selective regulator of adult hematopoietic stem cell survival. Genes Dev. 2004;18(19):2336-2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moriyama T, Metzger ML, Wu G, et al. . Germline genetic variation in ETV6 and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a systematic genetic study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1659-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Niihori T, Ouchi-Uchiyama M, Sasahara Y, et al. . Mutations in MECOM, encoding oncoprotein EVI1, cause radioulnar synostosis with amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(6):848-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kataoka K, Sato T, Yoshimi A, et al. . Evi1 is essential for hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, and its expression marks hematopoietic cells with long-term multilineage repopulating activity. J Exp Med. 2011;208(12):2403-2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goyama S, Yamamoto G, Shimabe M, et al. . Evi-1 is a critical regulator for hematopoietic stem cells and transformed leukemic cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(2):207-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Buonamici S, Li D, Chi Y, et al. . EVI1 induces myelodysplastic syndrome in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(5):713-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thompson AA, Nguyen LT. Amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia and radio-ulnar synostosis are associated with HOXA11 mutation. Nat Genet. 2000;26(4):397-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Horvat-Switzer RD, Thompson AA. HOXA11 mutation in amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia with radio-ulnar synostosis syndrome inhibits megakaryocytic differentiation in vitro. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2006;37(1):55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thompson AA, Woodruff K, Feig SA, Nguyen LT, Schanen NC. Congenital thrombocytopenia and radio-ulnar synostosis: a new familial syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2001;113(4):866-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nielsen M, Vermont CL, Aten E, et al. . Deletion of the 3q26 region including the EVI1 and MDS1 genes in a neonate with congenital thrombocytopenia and subsequent aplastic anaemia. J Med Genet. 2012;49(9):598-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bouman A, Knegt L, Gröschel S, et al. . Congenital thrombocytopenia in a neonate with an interstitial microdeletion of 3q26.2q26.31. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A(2):504-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Albers CA, Paul DS, Schulze H, et al. . Compound inheritance of a low-frequency regulatory SNP and a rare null mutation in exon-junction complex subunit RBM8A causes TAR syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):435-439, S431-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bluteau D, Balduini A, Balayn N, et al. . Thrombocytopenia-associated mutations in the ANKRD26 regulatory region induce MAPK hyperactivation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):580-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ludlow LB, Schick BP, Budarf ML, et al. . Identification of a mutation in a GATA binding site of the platelet glycoprotein Ibbeta promoter resulting in the Bernard-Soulier syndrome. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(36):22076-22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Noris P, Perrotta S, Seri M, et al. . Mutations in ANKRD26 are responsible for a frequent form of inherited thrombocytopenia: analysis of 78 patients from 21 families. Blood. 2011;117(24):6673-6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pippucci T, Savoia A, Perrotta S, et al. . Mutations in the 5′ UTR of ANKRD26, the ankirin repeat domain 26 gene, cause an autosomal-dominant form of inherited thrombocytopenia, THC2. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):115-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]