Abstract

Lung cancers with activating KRAS mutations are characterized by treatment resistance and poor prognosis. In particular, the basis for their resistance to radiation therapy is poorly understood. Here we describe a radiation resistance phenotype conferred by a stem-like subpopulation characterized by mitosis-like condensed chromatin (MLCC), high CD133 expression, invasive potential, and tumor-initiating properties. Mechanistic investigations defined a pathway involving osteopontin and the EGFR in promoting this phenotype. Osteopontin/EGFR-dependent MLCC protected cells against radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks and repressed putative negative regulators of stem-like properties such as CRMP1 and BIM. The MLCC-positive phenotype defined a subset of KRAS-mutated lung cancers that were enriched for co-occurring genomic alterations in TP53 and CDKN2A. Our results illuminate the basis for the radiation resistance of KRAS-mutated lung cancers with possible implications for prognostic and therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: KRAS, SPP1, EGFR, Lung Cancer, Radiation

INTRODUCTION

The KRAS gene encodes a GTPase involved in relaying signals from the cell membrane to the nucleus. Upon the introduction of point mutations (mut), most commonly at codons 12 and 13, the KRAS protein becomes constitutively active and acquires oncogenic properties. Activating mutations in KRAS are common, with the most frequent allelic mutations in codons 12 and 13 affecting almost 140,000 new cases of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), colorectal cancer, and pancreatic cancer in the United States per year (1). KRASmut cancers often have a poor prognosis and exhibit treatment resistance, particularly to agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (2–5). For many years, it has been known that mutations in KRAS may enhance cellular resistance to ionizing radiation (IR) though this connection has not been without controversy (6–8). In particular, only sparse clinical data have come out to suggest that the radiation resistance associated with the KRASmut genotype that is observed in the laboratory can also be seen in patients (9, 10). A variety of underlying mechanisms have been investigated to explain the radiation resistance of KRASmut cancer cells, but no consistent model has emerged (8, 11–14).

Cancer stem cells (CSC), also referred to as tumor-initiating or tumor-propagating cells, may promote metastases development and recurrence after therapy (15, 16). In radiation biology, “clonogenic” tumor cells have been defined as cells that have the capacity to produce an expanding family of daughter cells and form colonies after irradiation in an in-vitro assay or give rise to a recurrent tumor in in-vivo models. Whether or to which degree clonogenic cells represent CSCs is unclear. Because the goal of radiation therapy in curative intent is to eradicate the last surviving clonogen or CSC, as a single clonogenic cell remaining after completion of treatment may give rise to a local tumor recurrence, the relationship between radiation resistance and CSC-like tumor cells is of considerable interest (15, 17). Generally, cancer cells with CSC-like phenotypes or markers have been found to be radiation resistant (18–20). Enhanced DNA damage response and repair pathways have been discussed as one underlying mechanism (21, 22). Interestingly, KRAS has been recently linked to CSC-like phenotypes (1, 23–26). For example, in one report, a KRAS-dependent pathway promoted tumor initiation, anchorage independence, and self-renewal (23).

EGFR together with Aurora B kinase and Protein Kinase C alpha (PKCα) maintains mitosis-like condensed chromatin (MLCC) in a subpopulation of KRASmut cancer cells in interphase (27). The condensed chromatin is characterized by a mitosis-typical co-localization of phosphorylated serine 10 and trimethylated lysine 9 on histone 3 (H3S10p and H3K9me3). This modification may be involved in developmentally regulated gene regulation (28) but the primary biological function of MLCC in cancer cells has remained unclear. Furthermore, the data suggest that MLCC physically protects genomic DNA against the induction of lethal DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) by IR (27).

We set out to elucidate the mechanisms of radiation resistance associated with KRAS mutations in NSCLC. We found evidence for a previously unknown link between the radiation resistant and CSC-like phenotypes in KRASmut NSCLC cells and tumors. Unexpectedly, MLCC promoted not only radiation resistance but also CSC-like properties. Our data lead to a better understanding of the heterogeneity of KRASmut NSCLCs where a subset of cancers contains a radiation resistant fraction of MLCC-expressing cells that represents a novel therapeutic target.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

Annotated NSCLC cell lines were originally obtained from the MGH/Sanger cancer cell line collection http://www.cancerrxgene.org/translation/CellLine in the time period 2009–10, with the exception of A549 cells which were purchased from ATCC, as described in detail in previous publications (27, 29). Cell cultures were passaged for < 3 months after thawing an individual frozen vial. The identity of the cell lines had been tested as described using a set of 16 short tandem repeats (STR) (AmpFLSTR Identifier KIT, ABI). In addition, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiles based on a panel of 63 SNPs assayed using the Sequenom Genetic Analyzer was used for in-house identity checking whenever a cell line was propagated and confirmed uniqueness of cell lines for the ones without available STR (27, 29). On some cell lines additional authentication was performed by Bio-Synthesis, Inc (Lewisville, TX). No cell line tested positive for mycoplasma (MycoAlert, Lonza). 3D tumor spheres and isogenic KRASwt NCI-H1703 NSCLC cells with or without stable expression of a KRASmut transgene were cultured and treated as described previously (27). For generation of A549 IR survivor cell lines, A549 cells were irradiated with 2 or 8 Gy single dose concurrently with 2 μM erlotinib and seeded for colony formation. After two weeks, individual colonies were expanded for subsequent experiments.

Animal studies

Tumor xenografts were grown and treated as described previously (27, 30). For tumor initiation and growth studies, 2×105 cells were injected into the flanks of nude mice (nu/nu, Charles River Laboratories). Additional experiments were performed using 7- to 14- week-old male and female NMRI (nu/nu) mice, as described previously (31). KRASmut or wt xenografts were either untreated and excised at a volume of ~180 cm³, received 50 mg/m2 of erlotinib for two days and were harvested 4.5h after last application of erlotinib, were irradiated with 1 Gy and excised 30 min after fraction, or irradiated with 4 Gy and excised 24h after irradiation. Some tumors also received a combined treatment of irradiation and erlotinib. All irradiations were given using 200 kV X-rays (0.5 mm Cu), at a dose rate of ~1 Gy/min. Up to five animals were irradiated simultaneously in special designed plastic tubes fixed on a lucite plate and the tumor-bearing leg was positioned in the irradiation field by a foot holder distal to the tumor. Snap frozen samples and single-cell suspension generated from the xenografts were subjected to γ-H2AX staining or CD133 flow cytometry, respectively. In some experiments, tumor tissue samples from KRASmut and wt NCI-H1703 xenografts were maintained in complete medium, subjected to ex-vivo treatment with erlotinib, and snap frozen for subsequent immunofluorescence microscopy analysis.

Treatments

X-ray treatments were performed as described (30, 31). Erlotinib, Saracatinib (LC Laboratory, Woburn, MA), and ABT-263 (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and depending on the experiment were added 1–24 hours prior to irradiation at 2 μM, 1 μM, and 1 μM final concentration, respectively. The drugs were maintained for the duration of the respective experiment. Human osteopontin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was dissolved in deionized water. Drugs were aliquot and stored according to manufacturers’ guidelines.

Cell proliferation and survival assays

Clonogenic survival assays were performed as previously published (29). Determination of cell numbers at 3 or 5 days after irradiation was performed by using a fluorescent nucleic acid stain Syto60 or CellTiter-Glo (CTG) luminescence assay (Promega, Madison, WI), respectively, as described (29).

RNA interference

Transfections were carried out with 200 nM validated SPP1 siRNA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or a scrambled control siRNA (Ambion, Foster City, CA) using the X-tremeGENE Transfection Kit (Roche, Branford, CT) as described (27). Western blotting and subsequent experiments were carried out 48 hours after transfection.

Flow cytometry

Cells were incubated with CD133/1 (AC133) - PE antibody (Miltenyi Biotec, Cambridge, MA) with the dilution of 1:11 for up to 107 cells/100 μL of buffer at 4 °C for 2 hours. High and low CD133 expressing cells were subjected to sterile sorting by flow cytometry with 4 Laser BD FACSAria II Cell Sorter at MGH Pathology Flow Cytometry Core.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

The presence of MLCC and its characteristics have been previously described (27). Cells with MLCC were detected using a specific antibody against co-localized H3S10p and H3K9me3, and cells displaying the typical granular interphase pattern were scored as MLCC-positive as described. Staining and visualization of γ-H2AX, and 53BP1 foci were also performed as previously described (27). For visualization of BIM expression (#2933, Cell Signaling) the same protocol was used.

Western blotting

Whole cell lysates were prepared using standard methods. Specific antibodies against OPN, H3K9me3, total-H3, and CRMP1 (ab8448, ab8898, ab10799 and ab62558, respectively, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), BIM (#2933, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and β-actin (A2228, Sigma-Aldrich, Natick, MA) were used with 1:100 dilution. Immunocomplexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham Corp, Pittsburgh, PA) using goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to horseradish peroxidase as a secondary antibody (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Cells were seeded at 106 per 10-cm plate, and cross-linking was carried out using 1.5% formaldehyde. Procedures were performed using standard protocols. Primers used in the ChIP assays: CRMP1: Forward: 5′-GAAATCTGCTTGGGAGCAGC-3′, Reverse: 5′-GCCTAAAATCCCTGTCAATG-3′, BIM3: Forward: 5′-CCTCCCGAGGCTTCACACCG-3′, Reverse: 5′-CACCTACCCCAACCCGGCGG-3′ BIM7: Forward: 5′-GCAGTGATTGGGCGTAGGAG-3′, Reverse: 5′-TCAAGTGGTGGTAGTGGCGG-3′, GAPDH: Forward: 5′-GTATTCCCCCAGGTTTACAT-3′, Reverse: 5′- TTCTGTCTTCCACTCACTCC-3′,

Tumor sphere invasion assay

The tumor sphere invasion assay was performed using the 96 Well 3D Spheroid BME Cell Invasion Assay kit (# 3500-096-K, Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD), and the invasiveness of tumor spheres was analyzed following the manufacturer’s protocols.

Genomic analyses

Microarray analysis was performed on RNA collected from 2–3 biological replicates of NCI-H1703 clones. RNA was purified using the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions including treatment with DNAase. 1 μg of total RNA was used to create double-stranded cDNA using the cDNA Synthesis System (Roche). Double-strand cDNA was labeled with Cy3 using the Roche One Color DNA Labeling kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. 6 μg of labeled DNA was hybridized to 12×135K Human Expression arrays (Roche/NimbleGen) for 20 hours following the manufacturerʼs protocol. Arrays were washed using a NimbleGen wash buffer kit and scanned on a ms200 scanner. Images were aligned and features were extracted using NimbleScan 2.6 software.

We performed raw data quality control by principle component analysis and subsequent clustering by visualizing the distribution of expression levels to identify experimental outliers. After outlier removal, raw data files for each sample were normalized, background-corrected and saved to logarithmic scale using a Robust Multi-Array Analysis. Normalized data were analyzed and presented using R project. The normalized data from the experiments were fit into linear models using the Bioconductor package limma. Pair-wise comparisons of interest were performed using moderated t-statistics to test for significant differential expression. False discovery rate (FDR) at the .05 level for each probe was computed. Probes with p<0.05 and showing a fold change > 1 were considered differentially expressed. All probes were annotated with gene names.

To better visualize the effect of differentially expressed genes, pathway analysis was performed on those transcripts that had a significance of P < 0.05. Enriched networks, pathways, cellular processes etc were generated through the use of IPA (Ingenuity® Systems) in all three contrasts. The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) was used to annotate genes with chromosomal location in order to cluster highly repressed genes in mutant samples.

Microarray expression data generated for the current study have been made publicly available through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE79486). Microarray expression data were also obtained from the publicly available Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE).

For additional genomic analyses, data from patients with lung adenocarcinoma with wt or mut KRAS retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas through the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics site (32) or the Oncomine Cancer Microarray database (33).

RESULTS

KRAS mutations are associated with radiation resistance in NSCLC

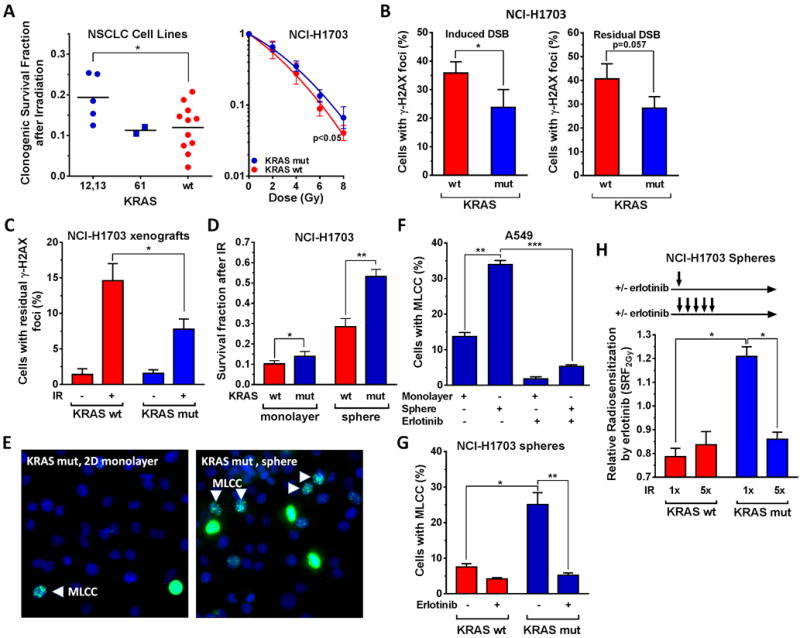

It has remained unclear to which extent KRAS mutations represent a biomarker of radiation resistance and which mechanisms may contribute to the radiation resistant cellular phenotype. As a hypothesis-generating exercise, we observed inferior treatment outcomes for KRASmut compared to wild-type (wt) NSCLCs in a small cohort of patients with locally advanced disease treated with radiation, prompting us to investigate the heterogeneity of radiation resistance in NSCLC further (Fig. S1A). In a panel of 18 NSCLC cell lines, KRAS codon 12/13 mutations were associated with increased survival of 62% after single dose irradiation (Fig. 1A, left panel). Expression of a KRASmut transgene at physiological levels in KRASwt NCI-H1703 cells (27) (Fig. S1B) produced a comparable survival increase of 55% (Fig. 1A, right panel). Consistent with this data, lower numbers of IR-induced DSB were observed in KRASmut versus wt cells (Fig. 1B), which was confirmed in xenografts (Fig. 1C). Unexpectedly, the difference in radiation resistance between KRASmut and wt cells was more pronounced in tumor spheres compared to monolayer cultures (87% compared to 36% survival increase, respectively) (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. KRAS mutation (mut) is associated with radiation resistance in NSCLC.

A, Left panel, Clonogenic survival of a panel of NSCLC cell lines after 6 Gy single dose ionizing radiation (IR) exposure, grouped according to KRAS status. Each data point represents one cell line. Statistical comparison by T-test. B, Right panel, Clonogenic survival of an isogenic NSCLC pair either wild-type (wt) for KRAS or stably transfected with a KRASmut transgene. Statistical comparison of fitted survival curves with the F-test. B, Left panel, Percentage of tumor cells with at least 20 γ-H2AX foci 15 minutes after exposure to 1 Gy. Right panel, Percentage of cells with at least 20 γ-H2AX foci at 24 hours (h) after 8 Gy irradiation. C, Percentage of tumor cells with at least 20 γ-H2AX foci from isogenic xenografts harvested 24h after irradiation of mice with 1 Gy. D, Survival fraction of cells in 2D monolayer and tumor sphere culture following treatment with 2 Gy. E, Representative immunofluorescence images showing co-localized H3S10p and H3K9me3 in monolayer and 3D cultured KRASmut A549 cells using a specific dual antibody. Punctate interphase-like staining pattern consistent with MLCC indicated by arrows. Diffuse nuclear staining consistent with metaphase. F, Percentage of A549 cells with MLCC grown in monolayer or sphere culture +/− treatment with erlotinib for 1h. G, Analogous to panel F, percentage of cells with MLCC. H, Relative radiosensitization of tumor spheres by erlotinib using single dose (2 Gy × 1) or fractionated irradiation (2 Gy × 5, 24h apart). Irradiations are illustrated by arrows. Radiosensitization factors were derived using the CTG assay as described (29). In all panels, bars or data points represent mean +/− standard error based on typically at least three biological repeat experiments, * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.01, *** p≤0.001 (T-test).

In agreement with this difference in radiation resistance, the fraction of KRASmut cells with the recently described radioresistance marker MLCC (27) was substantially increased when cells were grown under sphere versus monolayer conditions (Fig. 1E,F). This did not reflect any differences in cell cycle distribution (Fig. S1C). As we reported previously for monolayer cultures (27), MLCC expression in spheres was sensitive to erlotinib (Fig. 1F,G), implicating EGFR in promoting the radiation resistant phenotype of KRASmut cells. Strikingly, the radiosensitizing effect of erlotinib was lost upon fractionated irradiation of KRASmut spheres (Fig. 1H, Fig. S1D), which suggested enrichment with a radioresistant subpopulation. Because tumor spheres are known to promote the growth of CSC-like cells (24, 34), these observations encouraged us to further pursue potential links between MLCC and stemness in KRASmut NSCLC cells.

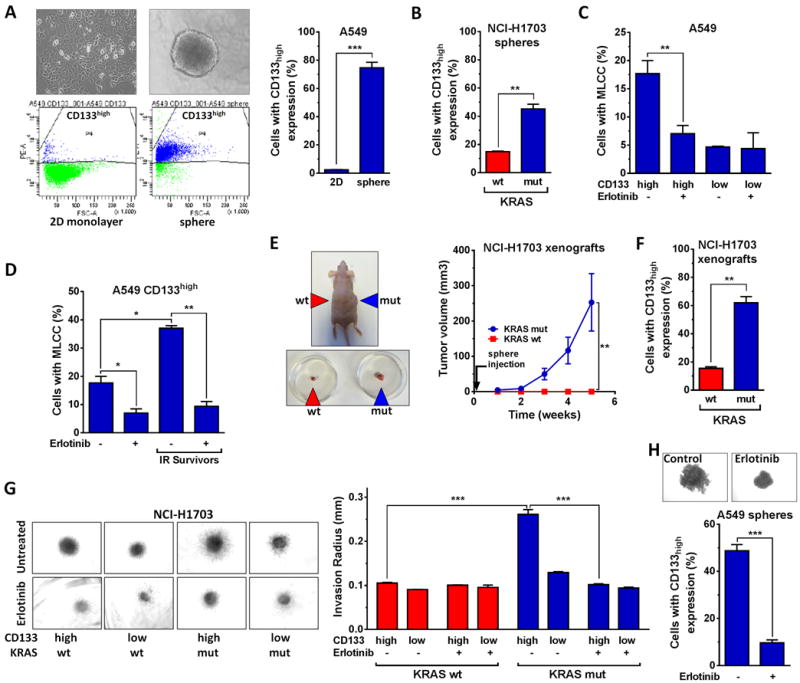

Radiation resistant MLCC-containing cells exhibit a CSC-like phenotype

In keeping with the enrichment of tumor spheres for CSC-like cells we observed an increase in the fraction of cells with high expression of the CSC marker CD133 (CD133high) (Fig. 2A, Fig. S2A) and greater vimentin expression (Fig. S2B) in spheres compared to monolayer cultures. Further, KRASmut spheres contained a higher number of CD133high expressers (Fig. 2B) and were larger in size than wt spheres (Fig. S2C). CD133high but not CD133low cells were enriched for erlotinib-sensitive MLCC (Fig. 2C). We next subjected KRASmut cells to irradiation and clonally expanded surviving cells (Fig. S2D,E). CD133high cells from these IR survivors were further enriched for MLCC-containing cells compared to the cell population pre-irradiation (Fig. 2D). Consistent with this finding, fractionated but not single dose irradiation as shown in Fig. 1H also increased the percentage of CD133high cells compared to unirradiated controls (Fig. S2F). Together, these data establish a link between the radiation resistant MLCC cell fraction and CD133high expression.

Figure 2. Association of MLCC with CSC-like phenotype in KRASmut NSCLC.

A, Left, Upper panels, Representative light microscopy images to illustrate growth of KRASmut A549 cells in monolayer (left) or sphere (right) culture. Left, Lower panels, Representative flow cytometry histograms to show the percentage of cells with high expression of the putative CSC marker CD133 (CD133high) (see also Fig. S2A). Right panel, percentage of CD133high expressing cells without any treatment. B, Analogous to panel A, Percentage of CD133high cells under sphere conditions. C, Percentage of cells with MLCC staining as a function of CD133 expression +/− treatment with erlotinib for 1h. D, Percentage of CD133high expressers with MLCC signal +/− erlotinib treatment. IR survivors indicate cells that were expanded from single cells surviving previous irradiation (Fig. S2D,E). E, Left, representative image of NCI-H1703 xenografts following implantation of cell suspensions into both flanks as indicated. Right panel, cell suspensions containing 2 × 105 cells from KRASmut or wt tumor spheres were injected into the flanks of nude mice (n=5) and tumor volumes were measured at the indicated times after injection. F, Percentage of CD133high cells in KRASmut and wt xenografts. G, Left panel, Representative images of a tumor sphere invasion assay with CD133high and CD133low expressers following treatment with 2 μM erlotinib. Right panel, Average length of sphere invasion radius was determined using ImageJ from 3 independent repeats. H, Representative images (upper panel) and percentage of CD133high cells (lower panel) +/− treatment with erlotinib for 24h. See Fig. 1 for data presentation and statistical comparisons.

To further investigate the CSC-like phenotype of our KRASmut model, we performed experiments where KRASmut cell suspensions with a high fraction of CD133high expressers proved to be substantially more tumorigenic than KRASwt cells when injected into nude mice (Fig. 2E). The increased fraction of CD133high expressing cells was preserved in these KRASmut xenografts (Fig. 2F). Further, KRASmut CD133high cells demonstrated the most pronounced invasion phenotype (Fig. 2G). Lastly, EGFR inhibition downregulated not only MLCC in KRASmut cells (Fig. 1F,G), but also suppressed invasion (Fig. 2G), sphere growth, and CD133 expression (Fig. 2H). In summary, these data suggest that EGFR is important for maintaining the radiation resistant CSC-like phenotype.

KRAS-dependent cellular radiation resistance is mediated by the SPP1 gene product osteopontin

To identify novel factors that may promote the radiation resistant phenotype of KRASmut NSCLC cells, we surveyed differentially expressed genes and pathways between isogenic KRASmut and wt NCI-H1703 cells (Fig. 3A, Fig. S3). One of the most significantly upregulated genes in KRASmut cells, compared to either endogenous wt or exogenous overexpression of wt KRAS, was SPP1. The protein product of SPP1 is osteopontin (OPN). Osteopontin is a member of the SIBLING (small integrin-binding ligand and N-linked glycoprotein) family, and it has a secreted and an intracellular form, which have been reported to be elevated in many cancer types (35–37). We found osteopontin levels to be elevated in both whole cell lysates and in media of KRASmut NCI-H1703 cultures compared to wt controls (Fig. 3B). Osteopontin expression was also notably increased in other KRASmut NSCLC cell lines (Fig. 3C). In order to determine the importance of SPP1/osteopontin for the radiation resistance of KRASmut cells, we depleted osteopontin by RNA interference in a total of 8 NSCLC cell lines (Fig. 3D, Fig. S4A). We first studied our isogenic NCI-H1703 model where osteopontin depletion led to radiosensitization of KRASmut but not wt cells (Fig. 3E, Fig. S4B). Conversely, addition of recombinant osteopontin to the media enhanced the radiation resistance of KRASwt but not mut cells (Fig. 3F). Depletion of osteopontin also increased the number of IR-induced DSB in KRASmut cells but failed to do so in wt cells (Fig. 3G).

Figure 3. Osteopontin (SPP1) promotes radiation resistance of KRASmut NSCLC cells.

A, Rank of highest differentially expressed genes in KRASmut NCI-H1703 cells compared to cells with endogenous wt (left) or exogenous overexpression of wt KRAS (right). Expression data from SPP1 probes are marked with stripes. B, Whole cell lysates and culture medium from KRASmut cells compared to wt controls were subjected to Western blotting with an osteopontin (OPN) specific antibody. C, Whole cell lysates from NSCLC cell lines were subjected to Western blotting with an OPN antibody. D, Western blot of KRASmut and wt NCI-H1703 cells transfected with scrambled control (Con) siRNA or siRNA against SPP1. E, Fraction of surviving NCI-H1703 cells following OPN depletion and irradiation with 2 Gy using the syto60 assay. Data were normalized to the survival fraction of irradiated wt control cells. F, Clonogenic survival fraction of NCI-H1703 cells +/− addition of recombinant OPN (1 μg/mL) for 1h prior to 6 Gy IR. G, Fraction of cells containing at least 20 53BP1 foci 15 minutes after 1 Gy IR following siRNA transfection +/− treatment with erlotinib. H, Fraction of KRASmut NCI-H1792 cells with at least 20 γ-H2AX foci 15 minutes after 1 Gy IR, transfected with siRNA +/− treatment with a histone methyl-transferase inhibitor (HMTi, Chaetocin at 100nM), as described (27). I, Cell survival fraction after 2 Gy with or without the treatments indicated, analogous to panel H. See Fig. 1 for data presentation and statistical comparisons. NS, not significant.

To elucidate the mechanisms by which osteopontin knock-down may cause radiosensitization, we co-treated cells with erlotinib. Pharmacological inhibition of EGFR enhanced the number of induced DSB, as reported previously (27). However, in an osteopontin-depleted background, EGFR inhibition had no effect (Fig. 3G), suggesting that osteopontin and EGFR regulate DSB induction in an epistatic manner. Furthermore, both osteopontin and EGFR promoted MLCC (Fig. S4C), and upon disruption of MLCC through pharmacological inhibition of histone methyl-transferases both osteopontin and EGFR lost their ability to regulate DSB induction (Fig. 3H, Fig. S4D). In complete agreement with these data, osteopontin depletion led to radiosensitization only if MLCC was not disrupted (Fig. 3I). Lastly, we did not find that inhibition of DNA-PKcs, PI3K, or MEK resulted in KRASmut-specific radiosensitization (Fig. S4E,F). Together, these data indicate that the radiation resistance of KRASmut NSCLC cells is promoted by SPP1/osteopontin through EGFR-dependent MLCC which represses DSB induction.

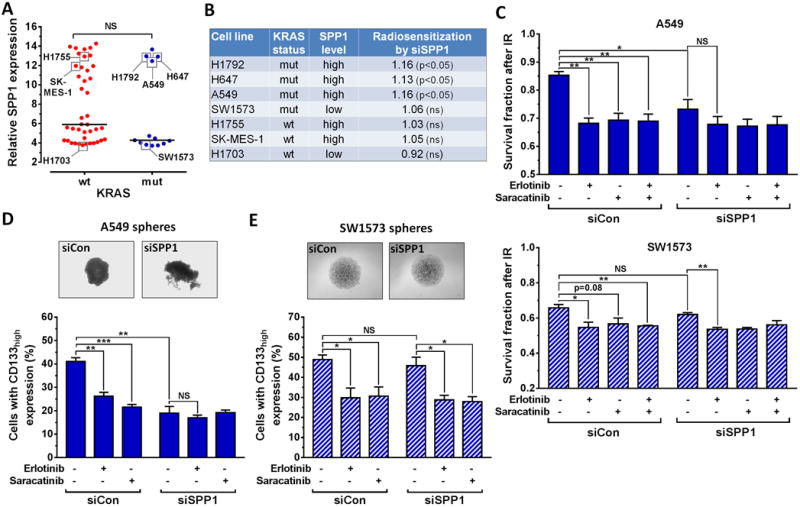

Functional heterogeneity with regard to SPP1 expression and cellular radiation resistance

To better understand the importance of SPP1 across different genomic contexts, we compared SPP1 expression in a panel of NSCLC cell lines (Fig. 4A) as well as human lung cancers (Fig. S5A). Unexpectedly, we did not observe a significant difference in SPP1 expression between KRASmut and wt genotypes. We thus hypothesized that functional differences may exist between high SPP1 expression in KRASmut vs. KRASwt cells. Indeed, osteopontin depletion by siRNA radiosensitized KRASmut but not wt cells in a chromatin- and EGFR-dependent manner using DSB induction and cell survival as endpoints (Fig. S5B,C). Together, these data, summarized in Fig. 4B, suggest that osteopontin enhances radiation resistance most strongly in high SPP1-expressing KRASmut cells but not in high SPP1-expressing KRASwt cells.

Figure 4. Functional heterogeneity of SPP1/osteopontin in NSCLC cell lines.

A, Relative gene expression of SPP1 in 54 NSCLC cell lines with known KRAS status. Horizontal lines represent the median in each group. B, Summary of radiosensitization achieved with siRNA-mediated depletion of osteopontin based on the data in Fig. 3E, 4C, S5C. C, Survival fractions of A549 and SW1573 cells in the syto60 assay following siRNA transfection and inhibitor treatments as indicated. Cells were irradiated with 2 Gy 1h after adding inhibitor. D, Upper panel, representative images of A549 spheres, and Lower Panel, A549 cells with CD133high expression after treatments as indicated. E, Results for SW1573 cells analogous to panel D. See Fig. 1 for data presentation and statistical comparisons. NS, not significant.

Next, we asked which factors may support radiation resistance in low SPP1-expressing KRASmut cells. In A549 cells with high SPP1 expression (Fig. 4A), siSPP1 transfection caused statistically significant radiosensitization compared to cells transfected with control siRNA but this was not seen in SW1573 cells which have low SPP1 (Fig. 4B,C). Depletion of osteopontin abolished the radiosensitizing effect of erlotinib in A549 cells (Fig. 4C), consistent with the data shown in Fig. 3I. In contrast, erlotinib retained its radiosensitizing effect in osteopontin-depleted SW1573 cells.

Osteopontin has been reported to signal to EGFR through Src Family Kinases (SFK) (38). We thus hypothesized that SW1573 cells may depend on SFK signaling even though osteopontin did not play a role for radiation resistance. Treatment with a potent inhibitor of SFK, particularly c-Src, indeed achieved radiosensitization similar to erlotinib (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, while osteopontin depletion only suppressed sphere growth and CD133 expression in A549 but not SW1573 cells, SFK inhibition affected these endpoints in both cell lines (Fig. 4D,E) and disrupted the formation of MLCC (Fig. S5D). Taken together, these data suggest that the osteopontin/SFK pathway is epistatic with EGFR signaling in terms of promoting stem-like features and radiation resistance. Therefore, osteopontin overexpression may promote MLCC-dependent radioresistance in some but not all KRASmut NSCLCs.

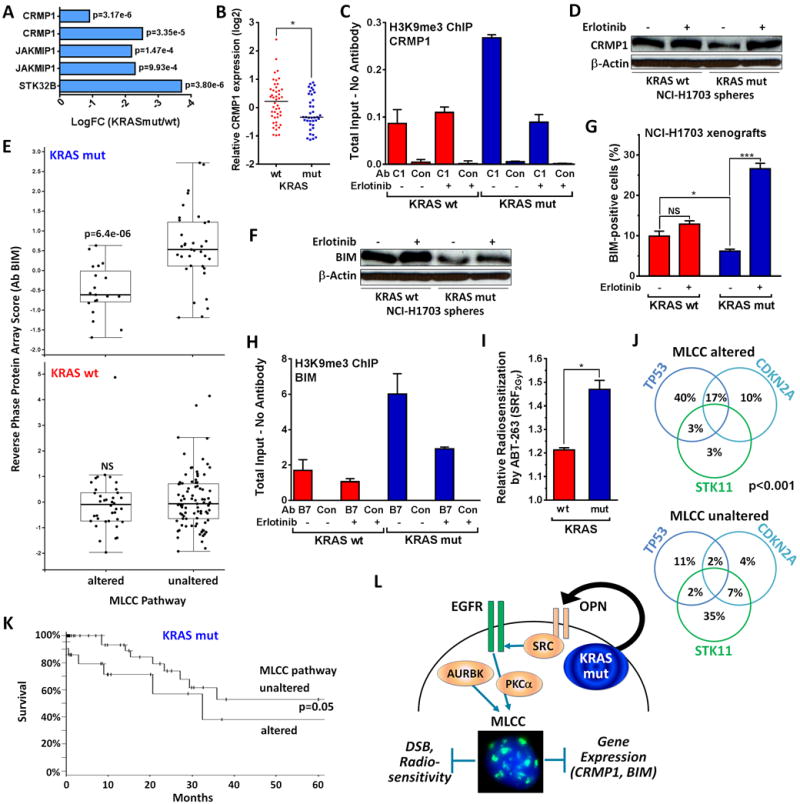

MLCC is associated with gene repression and poor prognosis in KRASmut NSCLC

To better understand the functional link between MLCC and CSC-like phenotype, we surveyed genes repressed in KRASmut compared to wt NCI-H1703 cells and noted a downregulated gene cluster comprised of CRMP1, JAKMIP1, and STK32B (Fig. 5A, Fig. S6A). Interestingly, CRMP1, Collapsin response mediator protein-1, belongs to the CRMP family and has been implicated in antagonizing tumor invasion and metastasis (39). CRMP1 was significantly repressed in KRASmut versus wt NSCLCs (Fig. 5B). Using chromatin immunoprecipitation we demonstrated that H3K9me3 is enriched at the CRMP1 locus in KRASmut compared to wt cells and sensitive to erlotinib treatment, which correlated well with CRMP1 protein levels (Fig. 5C,D). These observations support the idea that MLCC-mediated downregulation of genes such as CRMP1 promotes the KRASmut phenotype.

Figure 5. MLCC-associated gene repression in NSCLC.

A, Downregulation of gene cluster on chromosome 4p16 comprised of CRMP1, JAKMIP1, and STK32B in KRASmut NCI-H1703 cells compared to wt cells. B, Relative CRMP1 expression in a cohort of 85 lung adenocarcinomas. Horizontal lines represent medians, statistical comparison with Mann-Whitney test (two-sided). C, ChIP assays performed with KRASmut NCI-H1703 cells compared to wt following 1h treatment with 2 μM erlotinib. The immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified by real-time PCR with primers specific to the CRMP1 promoter, and the fold enrichment of input was normalized to the no antibody control. GAPDH was used as a negative control. D, Whole cell lysates from NCI-H1703 spheres were probed with a CRMP1-specific antibody +/− preceding erlotinib treatment for 18h. E, Reverse phase protein array scores for BIM in 230 patients with KRASmut or wt lung adenocarcinoma. Patients were grouped according to putative alterations in candidate genes supporting MLCC (Fig. S6B). F, Whole cell lysates from NCI-H1703 spheres were probed with a BIM-specific antibody +/− erlotinib treatment for 18h. G, Percentage of cells with nuclear BIM staining in xenografts from KRASmut versus wt NCI-H1703 cells. Tumor tissues were subjected to ex-vivo treatment with 2 μM erlotinib for 24h. H, ChIP analysis analogous to panel C. I, Relative radiosensitization following treatment of NCI-H1703 spheres with ABT-263 at 1 μM for 18h prior to irradiation with 2 Gy. J, Distribution of co-occurring mutations in KRASmut lung adenocarcinomas in the data set in panel E. Statistical comparison by Fisher’s Exact. K, Kaplan-Meier curves for patients with KRASmut NSCLC as a function of MLCC status, taken from panel E. Statistical comparison by logrank test. L, Dual model of KRASmut-dependent MLCC which represses DSB induction and promotes stem-ness. AURKB and PKCα were previously implicated in supporting MLCC expression (27). See Fig. 1 for data presentation and statistical comparisons.

We next investigated differential gene expression in KRASmut and wt NSCLCs harboring putatively activating alterations of MLCC pathway genes (Fig. S6B). Among the most downregulated proteins in KRASmut tumors with an altered MLCC pathway was BIM (BCL2-Like 11), a pro-apoptotic member of the B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 family of proteins (Fig. 5E, Fig. S7A). We confirmed that BIM repression was dependent on intact EGFR signaling both in cells and tumors (Fig. 5F,G, Fig. S7B,C). Intriguingly, the BIM locus was also enriched with H3K9me3 in KRASmut cells, similar to CRMP1, but not in wt cells (Fig. 5H). In order to reactivate BIM, we treated KRASmut cells with the BH3 mimetic ABT-263, which releases BIM from complexes with BCL-2 and BCL-xL (40). This treatment preferentially radiosensitized KRASmut spheres relative to wt cells which already have high BIM levels (Fig. 5I, Fig. S7D,E).

KRASmut NSCLCs with a putatively activated MLCC pathway and low BIM were significantly enriched for co-occurring genomic alterations in the TP53 and CDKN2A tumor suppressors (Fig. 5J), and furthermore, TP53 mutation trended with increased SPP1 expression (Fig. S7F). Lastly, the MLCC-positive subset of KRASmut tumors was associated with a worse survival than the remaining KRASmut tumors in a univariate analysis (Fig. 5K). Together, these findings indicate the presence of a KRASmut tumor subset with a stem-like phenotype that confers not only cellular radiation resistance but also worse prognosis.

DISCUSSION

Our efforts to uncover mechanisms of radiation resistance in KRASmut NSCLC have revealed novel insight into a stem-like phenotype of this aggressive cancer type. Key to our findings is a previously identified, but not well understood, small subpopulation of KRASmut cancer cells that is characterized by condensed chromatin (termed MLCC) (27). Dense chromatin can protect genomic DNA against lethal DSB upon exposure to IR, thereby conferring radiation resistance, but the primary biological function of MLCC is poorly understood (27, 28, 41, 42). Our data support a novel, dual model of MLCC which not only suppresses DSB induction but also serves to repress putative negative regulators of stem-like properties such as invasion and metastasis (CRMP1, BIM) (Fig. 5L). We have connected this CSC-like phenotype to EGFR and osteopontin pathways which co-operate in a previously unrecognized manner to regulate MLCC and DSB induction.

There exists controversy concerning the concept of CSC (43, 44). We have defined CSC as tumor-initiating cells, demonstrated by the enhanced ability of sphere-derived KRASmut cells to grow as xenografts in nude mice and heterogeneously express CD133 in these tumors (Fig. 2E,F). The MLCC-expressing radiation resistant subpopulation, which is enriched within the CD133high fraction of cells (Fig. 2C,D), has shown notable plasticity. For example, single-cell derived KRASmut populations have the ability to re-acquire MLCC expression in a subset of cells (Fig. 2D, Fig. S2D,E). These observations suggest a dynamic stem-like epigenetic state and argue against the presence of a clonally derived CSC population. Other data lend support to the emerging picture that KRASmut tumors are more stem-like than their wt counterparts, and that anchorage-independent growth conditions may reveal KRAS-dependent phenotypes (1, 23–25, 45). Interestingly, the PKC phosphorylation site S181 on KRAS is important for the oncogenic functions of mutated KRAS, and PKC inhibition represses tumorigenesis in KRASmut cancers. In addition, PKCα is required for MLCC expression in KRASmut cells (27). Together, these data strongly suggest that PKCα promotes the stem-like phenotype of KRASmut cancers (Fig. 5L). Osteopontin and SFK have not been previously implicated in promoting the radiation resistance of KRASmut versus wt tumor cells (Fig. 3,4). However, several recent reports highlight their importance for stem-like properties, while the role of EGFR in this regard is less clear (46–50). Osteopontin is an upstream activator of Src and EGFR signaling (38, 47, 51). Our data are thus entirely consistent with the hypothesis that this pathway promotes a stem-like phenotype in KRASmut NSCLC.

Not much is known about the factors that restrict stem-like properties. Chromatin condensation, such as MLCC, may be one way to control gene expression in this regard. This modification was recently found to control mesenchymal differentiation in non-cancerous cells (28). Our data indicate that in KRASmut cells MLCC downregulates CRMP1, a suppressor of invasiveness and metastasis in lung cancer (39, 52). However, it has not been previously linked to KRAS status. We also found an association of BIM repression with a stem-like phenotype (Fig. 5E–H). Interestingly, a recent study suggests that BIM-induced apoptosis may temper breast cancer metastasis by governing the survival of disseminating tumor cells (53). Our data suggest that low BIM levels are associated with stem-ness and radiation resistance in only a subset of KRASmut NSCLCs, which is enriched for TP53 mutations (Fig. 5J). Similarly, BIM expression in KRASmut NSCLC cell lines was heterogeneous and low BIM correlated with resistance to MEK/PI3K inhibitors (54). BIM re-expression or pharmacological release from BCL-2/xL complexes restored treatment sensitivity, similar to our data (Fig. 5I).

Lastly, we report a previously unrecognized mechanism of radiation resistance in stem-like NSCLC cells, i.e., suppression of DSB induction, a mechanism that stands in contrast to previous data showing enhanced repair of DNA damage in CSCs (18). We highlight two important connotations of this observation. First, our data do not rule out the possibility that other KRASmut tumor subsets may exhibit altered DNA damage responses/repair as an alternate mechanism of radiation resistance. Second, our findings, particularly in Fig. 1H, 2D, S2F, raise the interestingly possibility that enrichment for CSC-like, MLCC-positive tumor cells could account for at least some of the failures of combined radiation therapy with EGFR-directed targeted agents seen in the clinic. Because multiple factors in addition to EGFR may promote the MLCC-positive phenotype and because this phenotype can arise de-novo in cell populations derived from single cells that survive IR (Fig. S2D,E), we hypothesize that more than one molecular target will need to be inhibited to overcome the radiation resistance of KRASmut tumors in patients. This concept is consistent with the emerging notion that several CSC-associated pathways should be blocked in order to reduce stem cell load and treatment resistance (50, 55). Dissecting the inter-tumoral heterogeneity of KRAS-mutated cancers with regard to stemness and sensitivity to DNA damaging agents should be an important subject of future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center SPORE in Lung Cancer, NCI P50 CA090578 (H.Willers), American Cancer Society 123420RSG-12-224-01-DMC (H.Willers), UK Wellcome Trust 102696 (C.H. Benes), Cancer Clinical Investigator Team Leadership Award awarded by the National Cancer Institute though a supplement to P30CA006516 (T.S. Hong), Federal Share of program income earned by Massachusetts General Hospital on C06 CA059267, Proton Therapy Research and Treatment Center (T.S. Hong, H. Willers), R01GM097360 (J.R. Whetstine), and an American Lung Association Lung Cancer Discovery Award (J.R. Whetstine)

Footnotes

Conflicts: The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RK, McCormick F. Dragging ras back in the ring. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:272–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, Goddard AD, Heldens SL, Herbst RS, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han SW, Kim TY, Jeon YK, Hwang PG, Im SA, Lee KH, et al. Optimization of patient selection for gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer by combined analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation, K-ras mutation, and Akt phosphorylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2538–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsao MS, Aviel-Ronen S, Ding K, Lau D, Liu N, Sakurada A, et al. Prognostic and predictive importance of p53 and RAS for adjuvant chemotherapy in non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5240–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, Rigas J, Johnston M, Butts C, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2589–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernhard EJ, Stanbridge EJ, Gupta S, Gupta AK, Soto D, Bakanauskas VJ, et al. Direct evidence for the contribution of activated N-ras and K-ras oncogenes to increased intrinsic radiation resistance in human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cengel KA, Voong KR, Chandrasekaran S, Maggiorella L, Brunner TB, Stanbridge E, et al. Oncogenic K-Ras signals through epidermal growth factor receptor and wild-type H-Ras to promote radiation survival in pancreatic and colorectal carcinoma cells. Neoplasia. 2007;9:341–8. doi: 10.1593/neo.06823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim IA, Bae SS, Fernandes A, Wu J, Muschel RJ, McKenna WG, et al. Selective inhibition of Ras, phosphoinositide 3 kinase, and Akt isoforms increases the radiosensitivity of human carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7902–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mak RH, Hermann G, Lewis JH, Aerts HJ, Baldini EH, Chen AB, et al. Outcomes by Tumor Histology and KRAS Mutation Status After Lung Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wo JY, Zhu AX, McDonnell EI, Yeap B, Borger DR, Iafrate AJ, et al. Clinical and Molecular Predictors of Local Failure After SBRT for Liver Metastases: A Secondary Analysis of a Prospective Phase II Trial. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2015;93:S111–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minjgee M, Toulany M, Kehlbach R, Giehl K, Rodemann HP. K-RAS(V12) induces autocrine production of EGFR ligands and mediates radioresistance through EGFR-dependent Akt signaling and activation of DNA-PKcs. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:1506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams TM, Flecha AR, Keller P, Ram A, Karnak D, Galban S, et al. Cotargeting MAPK and PI3K signaling with concurrent radiotherapy as a strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1193–202. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleiman LB, Krebs AM, Kim SY, Hong TS, Haigis KM. Comparative analysis of radiosensitizers for K-RAS mutant rectal cancers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu D, Allsop SA, Witherspoon SM, Snider JL, Yeh JJ, Fiordalisi JJ, et al. The oncogenic kinase Pim-1 is modulated by K-Ras signaling and mediates transformed growth and radioresistance in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:488–95. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butof R, Dubrovska A, Baumann M. Clinical perspectives of cancer stem cell research in radiation oncology. Radiother Oncol. 2013;108:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:717–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann M, Krause M, Hill R. Exploring the role of cancer stem cells in radioresistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:545–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips TM, McBride WH, Pajonk F. The response of CD24(−/low)/CD44+ breast cancer-initiating cells to radiation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1777–85. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, Kalisky T, Dorie MJ, Kulp AN, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:780–3. doi: 10.1038/nature07733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause M, Yaromina A, Eicheler W, Koch U, Baumann M. Cancer stem cells: targets and potential biomarkers for radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7224–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rycaj K, Tang DG. Cancer stem cells and radioresistance. Int J Radiat Biol. 2014;90:615–21. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.892227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seguin L, Kato S, Franovic A, Camargo MF, Lesperance J, Elliott KC, et al. An integrin beta(3)-KRAS-RalB complex drives tumour stemness and resistance to EGFR inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:457–68. doi: 10.1038/ncb2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon BS, Jeong WJ, Park J, Kim TI, Min do S, Choi KY. Role of oncogenic K-Ras in cancer stem cell activation by aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt373. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barcelo C, Paco N, Morell M, Alvarez-Moya B, Bota-Rabassedas N, Jaumot M, et al. Phosphorylation at Ser-181 of oncogenic KRAS is required for tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013;74:1190–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang MT, Holderfield M, Galeas J, Delrosario R, To MD, Balmain A, et al. K-Ras Promotes Tumorigenicity through Suppression of Non-canonical Wnt Signaling. Cell. 2015;163:1237–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang M, Kern AM, Hulskotter M, Greninger P, Singh A, Pan Y, et al. EGFR-mediated chromatin condensation protects KRAS-mutant cancer cells against ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2825–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabbattini P, Sjoberg M, Nikic S, Frangini A, Holmqvist PH, Kunowska N, et al. An H3K9/S10 methyl-phospho switch modulates Polycomb and Pol II binding at repressed genes during differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:904–15. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-10-0628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Q, Wang M, Kern AM, Khaled S, Han J, Yeap BY, et al. Adapting a drug screening platform to discover associations of molecular targeted radiosensitizers with genomic biomarkers. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:713–20. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Morsbach F, Sander D, Gheorghiu L, Nanda A, Benes C, et al. EGF Receptor Inhibition Radiosensitizes NSCLC Cells by Inducing Senescence in Cells Sustaining DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6261–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurtner K, Deuse Y, Butof R, Schaal K, Eicheler W, Oertel R, et al. Diverse effects of combined radiotherapy and EGFR inhibition with antibodies or TK inhibitors on local tumour control and correlation with EGFR gene expression. Radiother Oncol. 2011;99:323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tam WL, Lu H, Buikhuisen J, Soh BS, Lim E, Reinhardt F, et al. Protein kinase C alpha is a central signaling node and therapeutic target for breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:347–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chambers AF, Wilson SM, Kerkvliet N, O’Malley FP, Harris JF, Casson AG. Osteopontin expression in lung cancer. Lung cancer. 1996;15:311–23. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singhal H, Bautista DS, Tonkin KS, O’Malley FP, Tuck AB, Chambers AF, et al. Elevated plasma osteopontin in metastatic breast cancer associated with increased tumor burden and decreased survival. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1997;3:605–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thalmann GN, Sikes RA, Devoll RE, Kiefer JA, Markwalder R, Klima I, et al. Osteopontin: possible role in prostate cancer progression. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1999;5:2271–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Das R, Mahabeleshwar GH, Kundu GC. Osteopontin induces AP-1-mediated secretion of urokinase-type plasminogen activator through c-Src-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11051–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shih JY, Yang SC, Hong TM, Yuan A, Chen JJ, Yu CJ, et al. Collapsin response mediator protein-1 and the invasion and metastasis of cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1392–400. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.18.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faber AC, Farago AF, Costa C, Dastur A, Gomez-Caraballo M, Robbins R, et al. Assessment of ABT-263 activity across a cancer cell line collection leads to a potent combination therapy for small-cell lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E1288–96. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411848112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elia MC, Bradley MO. Influence of chromatin structure on the induction of DNA double strand breaks by ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1580–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xue LY, Friedman LR, Oleinick NL, Chiu SM. Induction of DNA damage in gamma-irradiated nuclei stripped of nuclear protein classes: differential modulation of double-strand break and DNA-protein crosslink formation. Int J Radiat Biol. 1994;66:11–21. doi: 10.1080/09553009414550901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sourisseau T, Hassan KA, Wistuba I, Penault-Llorca F, Adam J, Deutsch E, et al. Lung cancer stem cell: fancy conceptual model of tumor biology or cornerstone of a forthcoming therapeutic breakthrough? J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:7–17. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antoniou A, Hebrant A, Dom G, Dumont JE, Maenhaut C. Cancer stem cells, a fuzzy evolving concept: a cell population or a cell property? Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3743–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.27305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujita-Sato S, Galeas J, Truitt M, Pitt C, Urisman A, Bandyopadhyay S, et al. Enhanced MET Translation and Signaling Sustains K-Ras-Driven Proliferation under Anchorage-Independent Growth Conditions. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2851–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao L, Fan X, Jing W, Liang Y, Chen R, Liu Y, et al. Osteopontin promotes a cancer stem cell-like phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via an integrin-NF-kappaB-HIF-1alpha pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6:6627–40. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lamour V, Henry A, Kroonen J, Nokin MJ, von Marschall Z, Fisher LW, et al. Targeting osteopontin suppresses glioblastoma stem-like cell character and tumorigenicity in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1047–57. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pietras A, Katz AM, Ekstrom EJ, Wee B, Halliday JJ, Pitter KL, et al. Osteopontin-CD44 signaling in the glioma perivascular niche enhances cancer stem cell phenotypes and promotes aggressive tumor growth. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:357–69. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bianchi-Smiraglia A, Paesante S, Bakin AV. Integrin beta5 contributes to the tumorigenic potential of breast cancer cells through the Src-FAK and MEK-ERK signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2013;32:3049–58. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thakur R, Trivedi R, Rastogi N, Singh M, Mishra DP. Inhibition of STAT3, FAK and Src mediated signaling reduces cancer stem cell load, tumorigenic potential and metastasis in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10194. doi: 10.1038/srep10194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mutrie JC, Chambers AF, Tuck AB. Osteopontin increases breast cancer cell sensitivity to specific signaling pathway inhibitors in preclinical models. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:680–90. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.8.16440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan SH, Chao YC, Chen HY, Hung PF, Lin PY, Lin CW, et al. Long form collapsin response mediator protein-1 (LCRMP-1) expression is associated with clinical outcome and lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2010;67:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merino D, Best SA, Asselin-Labat ML, Vaillant F, Pal B, Dickins RA, et al. Pro-apoptotic Bim suppresses breast tumor cell metastasis and is a target gene of SNAI2. Oncogene. 2015;34:3926–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hata AN, Yeo A, Faber AC, Lifshits E, Chen Z, Cheng KA, et al. Failure to induce apoptosis via BCL-2 family proteins underlies lack of efficacy of combined MEK and PI3K inhibitors for KRAS-mutant lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3146–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed SU, Carruthers R, Gilmour L, Yildirim S, Watts C, Chalmers AJ. Selective Inhibition of Parallel DNA Damage Response Pathways Optimizes Radiosensitization of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4416–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.