The US spends more on health care per capita than any other developed country, yet this higher spending is not associated with better health outcomes. In an influential article, Alan Garber and Jonathan Skinner (2008) argued this “unique inefficiency” may be due to institutional features of the US health care system – specifically, a predominantly fee-for-service system of reimbursement coupled with few supply-side constraints – fueling the rapid adoption and diffusion of medical technologies with small or unknown benefits.

In practice, testing this proposition is difficult. In their Journal of Economic Literature review, Amitabh Chandra and Skinner (2012) argue that “less effective” treatments diffuse more widely in the US than in other countries but cite only limited data from a few case studies. For example, they note that the US and the UK have similar use of intensive care unit (ICU) beds for conditions such as cardiac surgery that clearly indicate post-surgical ICU care. However, ICU bed use rates are higher in the US relative to the UK for elderly people (over age 85), for whom they argue ICU days are likely to be less cost-effective.

Such comparisons are complicated by at least two factors. First, obtaining consistent measures of healthcare utilization across countries in a way that holds the quality of health care services constant is challenging. For example, a given cardiovascular surgery procedure in the US may be higher or lower quality than an administration of the same procedure in Canada. Given data constraints, these measurement issues are difficult to overcome. Second, differential levels of medical technology diffusion across countries do not tell us whether the US is using “too much” or “too little” medical care from a social perspective.

In this paper, we use cross-country data on prescription drug sales newly linked with an arguably objective measure of drug “quality” to make progress on this question. Our data allows us to observe drug sales across countries at the package level – e.g. sales of bottles of 30 10mg tablets of Lipitor – providing a relatively consistent measure of utilization across countries. Our drug quality measure, developed by France’s public health agency, has the goal of quantifying a drug’s improvement over existing therapies. While this measure has limitations, it arguably makes progress on understanding the welfare implications of cross-country differences in drug diffusion.

We use these data to document how higher and lower quality drugs diffuse in the US relative to four comparison countries: Australia, Canada, Switzerland, and the UK. Our tabulations provide evidence that lower quality drugs diffuse more in the US relative to high quality drugs, compared to our four comparison countries. These patterns are consistent with Garber and Skinner’s (2008) assertion that US health care may indeed be “uniquely inefficient.”

I. Data

Our data on drug sales is drawn from the MIDAS dataset produced by IMS Health, a market research firm. This data is sourced from audits of retail pharmacies, hospitals, and other sales channels, and includes sales to both private and public purchasers. These data record quarterly unit sales and revenues at the “package” level – e.g. sales of bottles of 30 10mg tablets of Lipitor – from 2000–2013.

Our drug quality measure is from Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS), France’s public health authority. This data is available for drugs currently sold in France or whose sale in France stopped within the past three years.1 The HAS data include two quality measures: SMR (service médical rendu/actual benefit), an absolute rating of drug importance that determines whether reimbursement in France is justified; and ASMR (amélioration du service médical rendu/improvement in actual benefit), a relative rating of therapeutic value compared to existing treatments. Importantly, these SMR and ASMR scores are assigned independent of price, which is negotiated after these scores are assigned. That is, SMR and ASMR scores are not cost-effectiveness evaluations, but rather are assessments of clinical value.

For two reasons, we focus in this short paper on the ASMR measure rather than the SMR measure. First, most drugs are in practice included in a single SMR category, whereas drugs are relatively more distributed across the five ASMR ratings – ASMR I/Major, ASMR II/Important, ASMR III/Moderate, ASMR IV/Minor, and ASMR V/No improvement. Second, tabulations of the SMR measure against an outside quality measure – a flag for whether the drug was granted “priority review” at the US Food and Drug Administration – suggested little correlation, whereas the expected positive correlation emerged between ASMR ratings and FDA priority review flags. To economize on space, we aggregate ASMR into two categories: more (I/II/III) and less (IV/V) important.

We make three sample restrictions. First, we restrict attention to drugs with an ASMR rating. Second, some of our comparisons of interest require restricting attention to drugs launched in both the US and in a given comparison country; in these analyses, we restrict attention to drugs launched in the year 2000 or later in both countries, so that we focus on a sample of drugs for which our IMS sales data (which starts in 2000) measures the beginning of the diffusion curve. Finally, we restrict attention to brand-name (non-generic) drugs, as an analysis of the dynamics of brand and generic diffusion over time was beyond the scope of this short paper.

We link the HAS ASMR ratings to non-generic drugs recorded by the IMS MIDAS data as sold in France by merging on product name. Specifically, we first attempt a straight match of local French IMS product names with HAS product names. For any unmatched IMS product names we attempted a manual match to HAS product names. We then assign the ASMR rating for a given French product name to all observations in the IMS data with the same international product name and/or molecule name. Of the around 2,000 non-generic products that the IMS data records as being sold in France between 2000–2013, 60% are matched to the HAS data.

Our comparison countries are Australia, Canada, Switzerland, and the UK. Of note is that our HAS drug quality measures are only available for drugs commercialized in France, which complicates the UK comparison in the following sense. Drug approval procedures in the European Union (EU) – either centralized or via mutual recognition – mean that the cost of launch elsewhere in Europe conditional on launch in France is lower than the cost of launch in the US.2 Hence, we expect drugs launched in the UK to have more similarity to France in our sample than one would expect from a random sample of drugs sold globally.3

II. Preliminary results: Cross-country drug launches

Our main analyses compare patterns of drug diffusion conditional on launch for the sub-sample of molecules sold in both the US and the relevant comparison country. In order to understand selection into that sample, we here first briefly summarize patterns of product launches across countries.4

Higher quality (ASMR I/II/III) drugs are almost always launched in both countries. When higher quality drugs are not launched in both countries, they are almost always only launched in the US: in no comparison are more than 5% of higher quality drugs only launched in the comparison country. Lower quality (ASMR IV/V) drugs are somewhat more likely to be launched only in the US relative to Canada (14% in the US vs. 5% in Canada) and Australia (14% in the US vs. 10% in Australia), and slightly less likely relative to Switzerland (8% in the US vs. 13% in Switzerland) or the UK (3% in the US vs. 16% in the UK).

In terms of launch timing, higher quality drugs are most often launched in the same month in the US and any of the four comparison countries (79–92%). When not launched simultaneously, higher quality drugs are almost always launched first in the US: in no comparison are more than 5% of higher quality drugs first launched in the comparison country. For lower quality drugs the share of simultaneous launches is slightly lower (66–78%), and when not launched simultaneously drugs are roughly equally likely to be first launched in the US versus any of the comparison countries.

III. Main results: Cross-country drug diffusion

Our key research question of interest is: how do higher- and lower-quality drugs diffuse over time in the US relative to our comparison countries? We measure diffusion by sales of standard units (that is, quantities rather than revenues), and again focus our quality metric on a comparison of more (ASMR I/II/III) and less (ASMR IV/V) important drugs. We analyze diffusion over the first six years after a product is launched, during which time a new product should generally not face any generic competition.

We start by analyzing a specification which pools our four comparison countries across all six post-launch years of diffusion. Specifically, for molecule m in country c in year t relative to the drug’s launch in country c we estimate:

| (1) |

where δm are molecule fixed effects, ζt are fixed effects for years relative to the drug’s launch in country c, and νc are country fixed effects. We report 95% confidence intervals based on robust standard errors. Our interest is in a test for equality of the γ and α coefficients, which tests whether low quality drugs diffuse more than high quality drugs in the US relative to our comparison countries. Our estimate of γ is 36.61 (standard error 7.307) and our estimate of α is 64.05 (standard error 6.790). The p-value from an F-test for equality of these two coefficients is 0.005. This suggests that the US is uniquely inefficient in the sense that low quality drugs diffuse more quickly compared to high quality drugs in the US relative to our comparison countries.

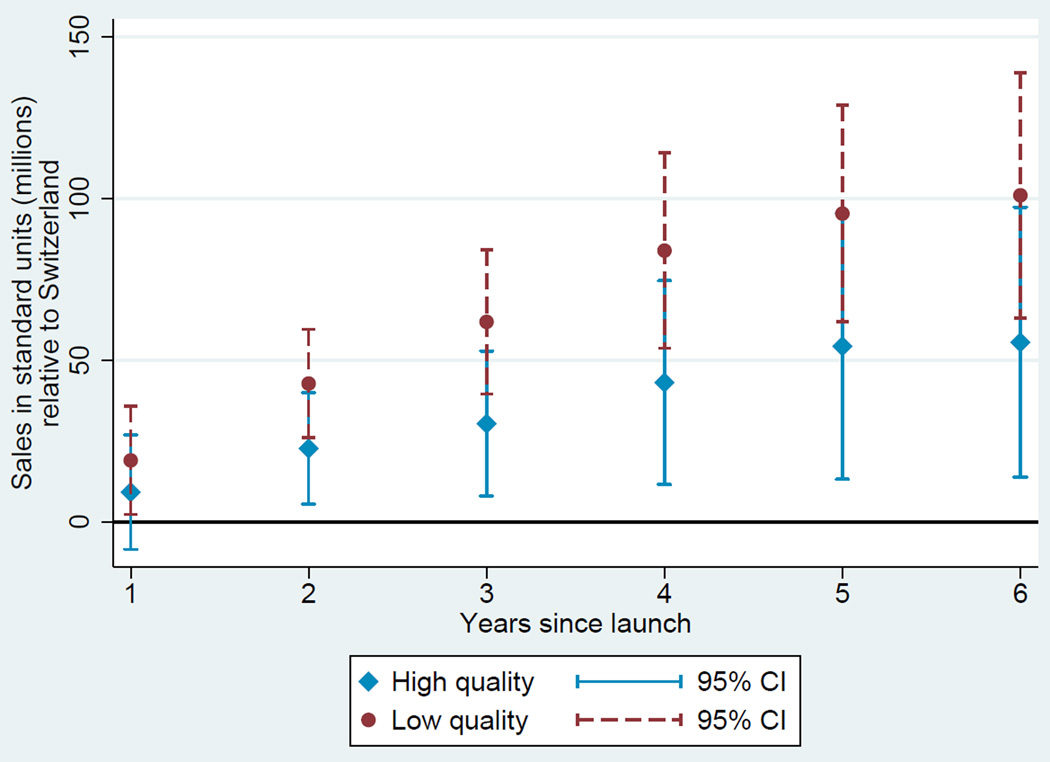

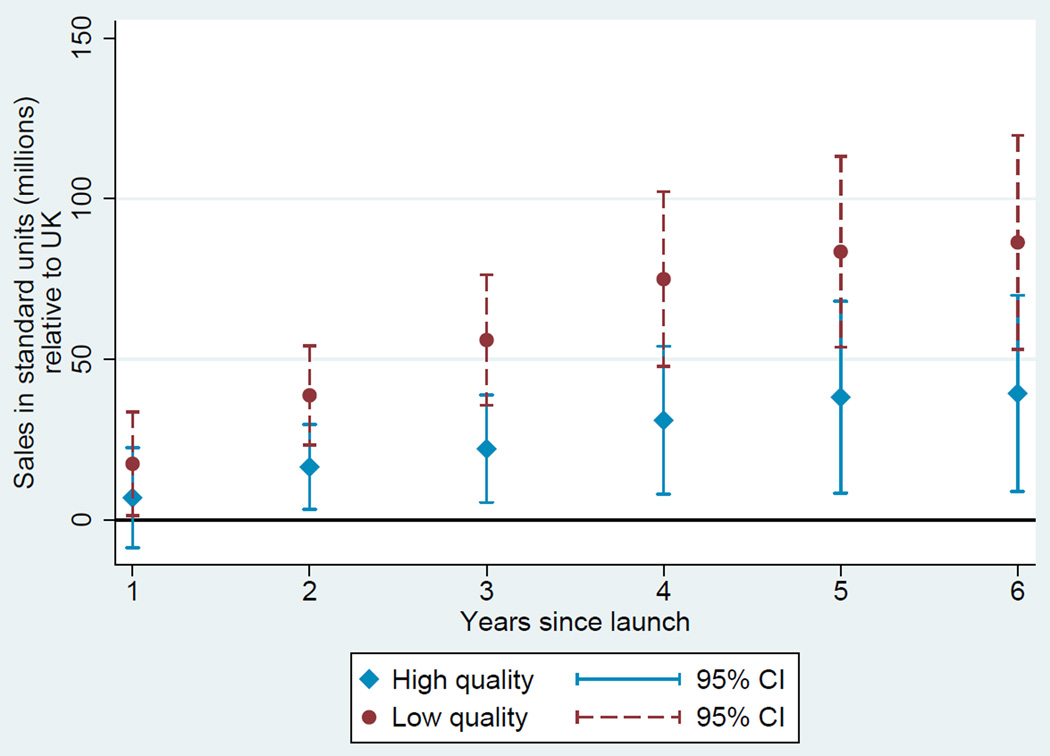

The same pattern holds qualitatively if we compare the US against each of our comparison countries individually (γ < α in all four comparisons), although the difference in coefficients is only statistically significant for the UK and Switzerland. All of these results are strengthened if we omit ASMR III (the “intermediate”) quality category, in which case the analogous p-values for all comparisons – the pooled country comparison, and all four individual country comparisons – is less than 0.001.

To provide a graphical version of these results, we plot country-specific diffusion curves for molecule m in country c in year t relative to the drug’s launch in country c based on this specification:

| (2) |

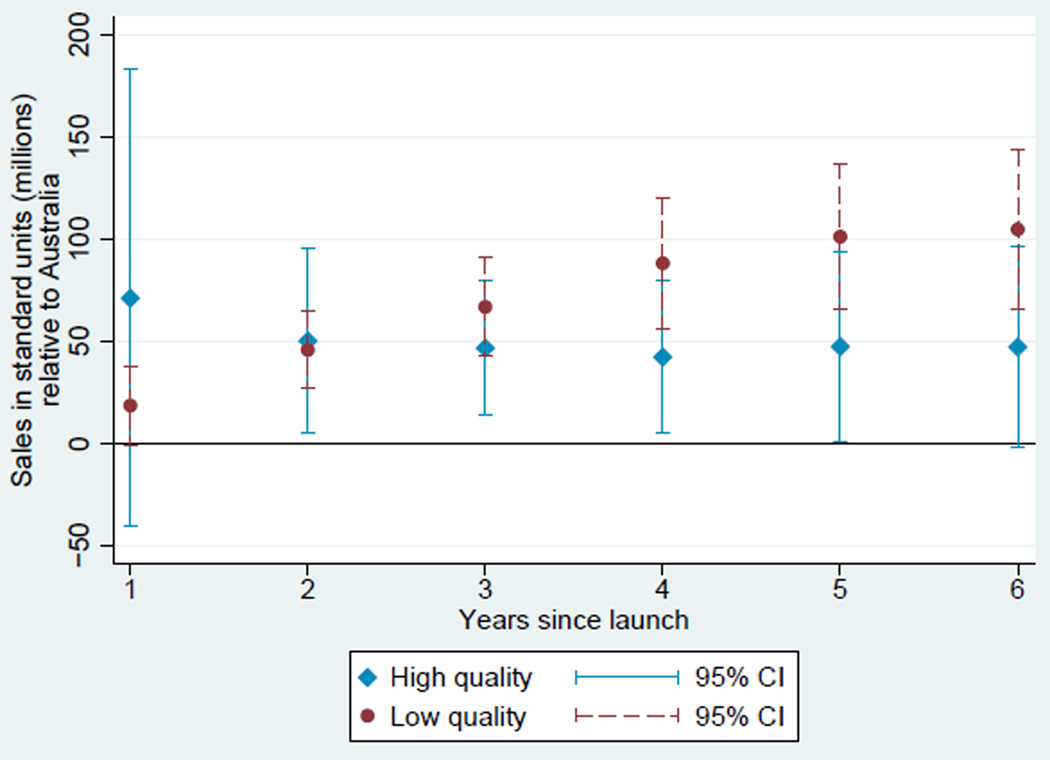

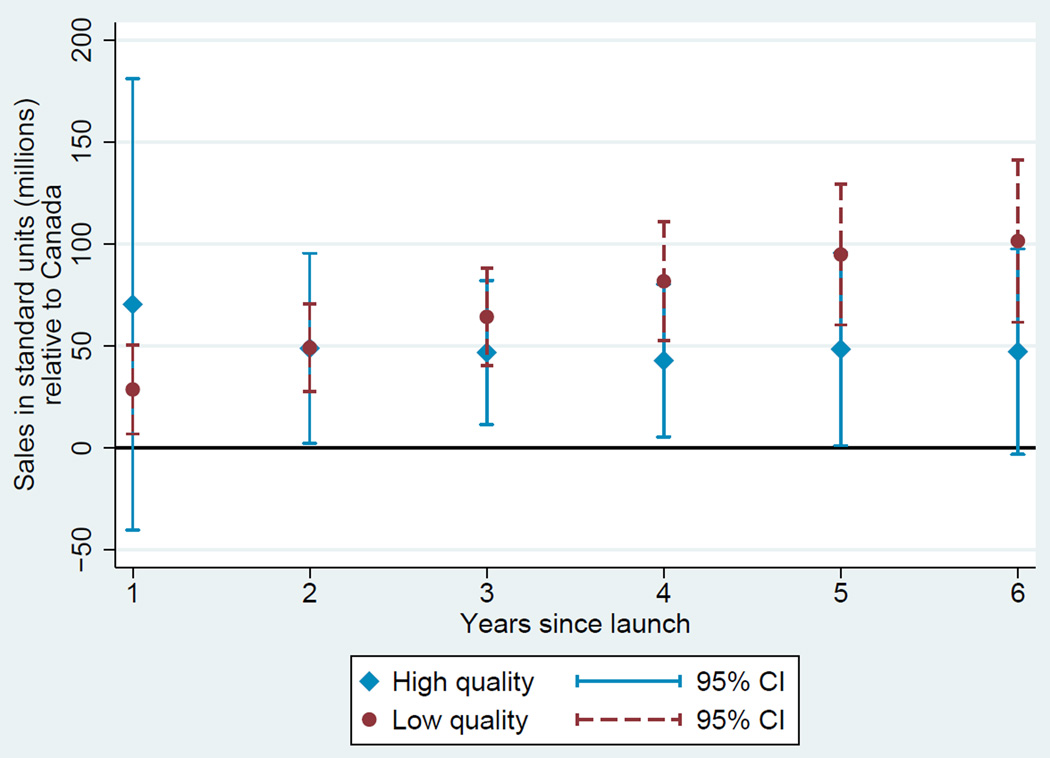

Based on these estimates, we plot two diffusion curves. First, we plot a diffusion curve for lower quality drugs based on ψ + γt in each year t relative to the country-specific year of launch. Second, we plot a diffusion curve for higher quality drugs based on ψ + ϕ + γt + νt in each year t relative to the country-specific year of launch. The diffusion curve for lower quality drugs is plotted in each of Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 in darker colored red coefficients (with dashed 95% confidence interval bars), and the diffusion curve for higher quality drugs is plotted in lighter colored blue coefficients (with solid 95% confidence interval bars).

Figure 1.

Diffusion: US and Australia

Figure 2.

Diffusion: US and Canada

Figure 3.

Diffusion: US and Switzerland

Figure 4.

Diffusion: US and UK

While the confidence intervals for low and high quality drugs are overlapping in this more disaggregated comparison, qualitatively the overall patterns are remarkably consistent: with the exception of the year of and first year after launch in the Australia and Canada, lower quality drugs consistently diffuse more in the US relative to higher quality drugs, judged relative to any of the four comparison countries.

IV. Conclusions

A number of papers have documented trends in the international diffusion of pharmaceuticals, including Danzon, Wang and Wang (2005), Kyle (2007), Kyle and Qian (2014), and Cockburn, Lanjouw and Schankerman (2016). These papers have attempted to quantify the inuence of factors such as intellectual property rights and price control policies on firms’ decisions to launch new drugs globally. To the best of our knowledge, this short paper is the first to analyze the international diffusion of pharmaceuticals separately by a measure of drugs’ therapeutic quality. While our drug quality measure is of course imperfect – in particular, while it is independent of price, assignment of these measures happens in the shadow of price negotiations – it arguably takes a step forward in understanding the welfare implications of cross-country differences in drug diffusion.

Our analysis compares drug diffusion in the US relative to a small number of comparison countries – Australia, Canada, Switzerland, and the UK – separately by drug quality levels. Our tabulations suggest that low quality drugs diffuse more quickly compared to high quality drugs in the US relative to these four comparison countries. That difference is statistically significant, and – as expected – is even stronger if we exclude drugs of “intermediate” quality levels. These patterns are consistent with Alan Garber and Jonathan Skinner’s (2008) assertion that the US health care system may be “uniquely inefficient” in the sense of fueling the rapid adoption and diffusion of medical technologies with small or unknown benefits.

Our hope is that the newly linked data developed in this paper can in the future be combined with an analysis of policy changes in order to analyze the potential roles of specific factors in explaining the higher diffusion of lower quality drugs in the US relative to other countries.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jane Choi for excellent research assistance, and to Amitabh Chandra, Dan Fetter, Amy Finkelstein, and Jon Skinner for helpful comments. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the NIH Common Fund, Office of the NIH Director, through grant U01-AG046708 to the NBER; the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NBER. Financial support from NSF Grant 1151497 and the Intellectual Property and Markets for Technology Chair at MINES ParisTech is also gratefully acknowledged. Kyle thanks Pfizer for access to the IMS data used.

Footnotes

Our version of the data is from 2 June 2016.

Costs of obtaining marketing authorization elsewhere in Europe is low, although pricing and reimbursement negotiations may add to launch costs.

Regulatory authorities in all five of the countries we analyze have harmonized requirements and share some data as part of the approval process as well as in assessing good manufacturing practices. However, obtaining a marketing authorization in non-EU countries is not subject to reciprocity agreements between these countries.

Because international product names can differ across countries, this comparison is at the molecule level.

Contributor Information

Margaret Kyle, MINES ParisTech (CERNA) and PSL Research University, V329, 60 boulevard Saint Michel, 75272 Paris Cedex 06 France.

Heidi Williams, Department of Economics, MIT, 50 Memorial Drive, E52-440, Cambridge MA 02142.

REFERENCES

- Chandra Amitabh, Skinner Jonathan. Technology Growth and Expenditure Growth in Health Care. Journal of Economic Literature. 2012;50(3):645–680. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn Iain, Lanjouw Jean, Schankerman Mark. Global Diffusion of New Drugs: The Role of Patent Policy, Price Controls and Institutions. American Economic Review. 2016;106(1):136–164. doi: 10.1257/aer.20141482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzon Patricia M, Wang Richard, Wang Liang. The Impact of Price Regulation on the Launch Delay of New Drugs – Evidence from Twenty-five Major Markets in the 1990s. Health Economics. 2005;14:269–292. doi: 10.1002/hec.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber Alan, Skinner Jonathan. Is American Health Care Uniquely Inefficient? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2008;22(4):27–50. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.4.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle Margaret. Pharmaceutical Price Controls and Entry Strategies. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2007;89(1):88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle Margaret, Qian Yi. Intellectual Property Rights and Access to Innovation: Evidence from TRIPS. NBER Working Paper 20779. 2014 [Google Scholar]