Abstract

This article presents an account of our research on the discovery and development of new-generation fluorine-containing antibacterial agents against drug-resistant tuberculosis, targeting FtsZ. FtsZ is an essential protein for bacterial cell division and a highly promising therapeutic target for antibacterial drug discovery. Through design, synthesis and semi-HTP screening of libraries of novel benzimidazoles, followed by SAR studies, we identified highly potent lead compounds. However, these lead compounds were found to lack sufficient metabolic and plasma stabilities. Accordingly, we have performed extensive study on the strategic incorporation of fluorine into lead compounds to improve pharmacological properties. This study has led to the development of highly efficacious fluorine-containing benzimidazoles as potential drug candidates. We have also performed computational docking analysis of these novel FtsZ inhibitors to identify their putative binding site. Based on the structural data and docking analysis, a plausible mode-of-action for this novel class of FtsZ inhibitors is proposed.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Antibacterial, Fluorine-containing benzimidazoles, FtsZ, Structure-activity relationship, Metabolic and plasma stability, Docking, Molecular modeling

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) was responsible for 1.5 million deaths in 2014, which was second only to HIV/AIDS related fatalities among all infectious diseases [1,2]. TB is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and is highly contagious when airborne [3]. It has been estimated that 90% of humans who are exposed to or infected with the pathogen have latent-TB, which has a 10% chance of progressing to an active-TB diseased state during their lifetime [4]. Recent statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate an estimated 9.6 million new TB cases globally in 2014 [1,2]. Among these cases, 12% were HIV-positive individuals with 0.4 million deaths, which demonstrates the ability of the bacteria to target immunocompromised patients [1,2]. In 2014, 480,000 cases of MDR-TB were estimated, but only 123,000 cases were actually detected and reported [1,2]. MDR-TB, which is resistant to at least one of the three second-line antibiotics and fluoroquinolones, is classified as extensively drug resistant-TB (XDR-TB). About 9.7% of MDR-TB cases have been classified as XDR-TB by WHO in 2015 and 105 countries have reported at least one case of XDR-TB [1,2].

1.1. FtsZ as the target for the drug discovery of new-generation anti-TB agents

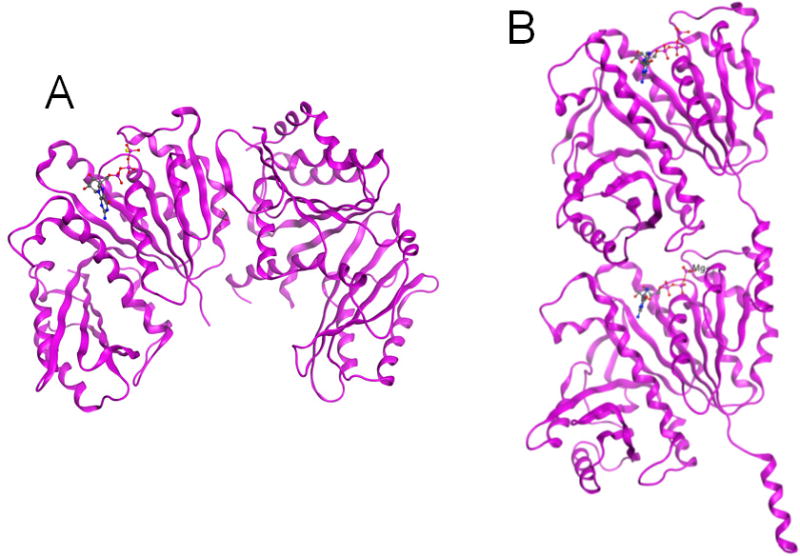

The globally spread resistance to existing therapeutics has become a major clinical challenge for effective treatment of the disease. Thus, in order to address the drug resistance issue, there is an urgent need for the identification of novel therapeutic targets. Therefore, FtsZ, an essential bacterial cytokinesis protein, has been recognized as a highly promising therapeutic target [5–9]. FtsZ polymerizes bi-directionally in the presence of GTP, at the center of the cell to form “Z-ring” [10–14]. Several other cell division proteins are recruited to undergo Z-ring contraction, resulting in septum formation and cell division [10–14]. Consequently, the inhibition of critical FtsZ assembly would block the cell division, which should lead to bacterial growth inhibition and cell death [5,7,8,15–17]. Crystal structures of the head-to-head lateral FtsZ dimer of M. tuberculosis (pdb: 1RLU) [12], as well as the head-to-tail longitudinal FtsZ dimer of M. jannacschii (pdb: 1W5A) [18] are shown in Fig. 1. The key function of FtsZ in the Z-ring formation and bacterial cell division is illustrated in Fig. 2 [5,19].

Fig. 1.

Crystal structures of FtsZ. (A) head-to-head lateral FtsZ dimer of M. tuberculosis (pdb: 1RLU) [12]; (B) head-to-tail longitudinal FtsZ dimer of M. jannacschii (pdb: 1W5A) [18].

Fig. 2.

(A) FtsZ monomers polymerize in the presence of GTP, forming protofilaments. (B) Protofilaments line up at the center of the cell to form the highly dynamic Z-ring, which is anchored to the bacterial cell membrane by FtsA and ZipA. FtsZ monomers readily exchange with FtsZ molecules incorporated into the Z-ring. (C) Contraction of the Z-ring leads to invagination of the cell membrane. (D) Septation is completed and the Z-ring dissipates. Adapted from Reference [19].

As described above, FtsZ emerged as a promising new target for antibacterial drug discovery. Thus, in the last decade, FtsZ inhibitors have been actively investigated for pathogen specific as well as broad-spectrum antibacterial drug discovery against a variety of pathogens [5,8,19–22]. As a result, several types of compounds have been identified as promising leads for antibacterial drug development, e.g., OTBA [23], 2-alkoxycarbonylamino-pyridines [24], 2-carbamoylpteridine [25], taxanes [8,15,26], benzimidazoles [5,27–32], GTP analogs [33,34], benzo[c]phenathridines [35,36], isoquinolines [35,37,38], PC190723 [39,40], Zantrins [6] and chrysophaentins [41]. However, against Mtb-FtsZ, only taxanes [15] and benzimidazoles [27] have been studied as promising leads after the pioneering work by the Southern Research Institute group [24,25,37,42].

1.2. Strategic incorporation of fluorine into drug leads to improve their potency and pharmacological properties

The importance of fluorine in medicinal chemistry is evident based on the fact that a large number of fluorinated compounds have been approved by the FDA for medical use [43–47]. In fact, fluorine is recognized as the second “favorite heteroatom” after nitrogen in the current drug design [48]. It has been demonstrated that the replacement of a C-H or C-O bond with a C-F bond in biologically active compounds often introduces beneficial pharmacological properties such as higher metabolic stability, increased binding to target molecules, and enhanced membrane permeability [49,50]. Small atomic radius, high electronegativity, nuclear spin of ½, and low polarizability of the C-F bond are among the special properties that make fluorine and organofluorine groups very attractive in chemical biology and medicinal chemistry. Accordingly, it is currently a common practice in drug discovery to explore fluoro-analogs of lead compounds under development. This account describes and discusses our case study on the strategic incorporation of fluorine into new-generation anti-TB agents based on the benzimidazole scaffold, targeting Mtb-FtsZ.

2. Effects of the fluorine and organofluorine substitutions on the potency and metabolic stability of benzimidazole-based FtsZ inhibitors as novel anti-TB agents

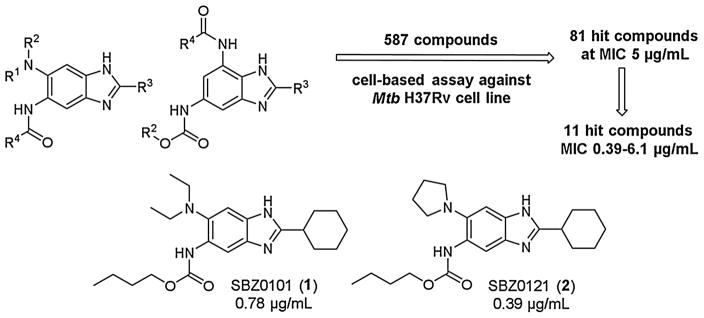

We started our drug discovery project for new-generation anti-TB agents, targeting the key cell division protein of M. tuberculosis, Mtb-FtsZ, from the design, moderately high throughput (HTP) synthesis of libraries of 2,5,6- and 2,5,7-trisubstituted benzimidazoles, and their whole cell screening. Moderately HTP screening of those compound libraries by the microplate Alamar blue assay [27,51] against M. tuberculosis H37Rv at 5 μg/mL concentration identified a good number of hit compounds [27]. Furthermore, selected early lead compounds from these hits exhibited promising MIC values in the range of 0.39–6.1 μg/mL against drug sensitive (H37Rv) as well as drug resistant clinical strains of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 3) [27]. It has been shown that these lead compounds inhibited FtsZ assembly in a dose dependent manner, and enhanced the GTPase activity of Mtb-FtsZ [27].

Fig. 3.

Early lead compounds from hit benzimidazoles [28].

Moreover, benzimidazoles, SBZ0101 (1) and SBZ0121 (2) (Fig. 3), were found to be bactericidal through kill characteristics analysis [31]. It has also be shown that 1 and 2 are active against non-replicating Mtb grown under low oxygen conditions [31], which is unexpected and very exciting since it indicates that these compounds have potential to be effective against latent TB infection.

SBZ0101 (1) was evaluated in two different animal models of acute TB infection to investigate if 1 can reduce the bacterial load during an acute infection and inhibit dissemination from the site of infection to secondary sites [31]. In the first acute infection animal study which uses immune incompetent GKO mice (C57BL/6-Ifngtm1ts, Jackson Laboratories), 1 reduced the bacterial load of M. tuberculosis H37Rv by 0.71–0.17 log10 CFU in the lungs and 0.41–0.36 log10 CFU in spleen [31]. In the second dissemination model of infection using immune competent C57BL/6 mice, 1 reduced the bacterial load of M. tuberculosis Erdman in the spleen by log10 1.6–0.49 CFU [31]. Thus, these animal studies show that 1 has some encouraging efficacy as an early lead compound against an acute infection and can prevent dissemination to secondary sites.

Since these two early lead compounds have shown promising antibacterial activities in vitro and in vivo, a host of preclinical evaluations on the pharmacological properties of 1 were performed. In these evaluations, 1 exhibited very good permeability (Caco2/TC7), safe for hERG affinity, not an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A4, and very clean kinase profile (only one kinase in selected 50 kinases panel). Also, 1 did not show cytotoxicity (IC50 > 400 μM) in Vero cells [31]. However, 1 was found to have an issue with plasma stability in mice, which was identified as the most urgent need for improvement. Although 1 was stable in human blood plasma (only 5% clearance), it was moderately unstable in murine blood plasma (56% clearance) at 37 °C for 4 h. SBZ0121 (2) was even worse, i.e., 9% and 98.5% clearance in human and murine plasma, respectively. The stability of 1 in murine plasma was found to be improved to 10% clearance in the presence of a hydrolase inhibitor, phenylsulfenylmethyl fluoride (PMSF). Thus, it was clear that the carbamate moiety of 1 was the cause of the instability. Metabolic stability (against liver microsomes) of 1 and 2 were problematic as well, especially in rat and mouse (92–100% clearance) although the stability in human microsomes was better (78 and 83% clearance, respectively) (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Fluorine-containing benzimidazoles, their potency and metabolic stability.a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. No./Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | Code | MIC (μg/mL) H37Rv | CLogPb | % metabolic clearance human/rat/mousec |

| 1 | Cy | OBu-n | Et2N | SBZ0101 | 2.0 | 7.15 | 78/92/98 |

| 2 | Cy | OBu-n | (CH2CH2)2N | SBZ0121 | 1.0 | 6.20 | 83/100/97 |

| 3 | Cy | OCH2CF3 | Et2N | SBZ0105 | 1.56 | 6.36 | 71/56/100 |

| 4 | Cy | OCH2CF3 | (CH2CH2)2N | SBZ0125 | 0.31 | 5.41 | 20/10/96 |

| 5 | Cy | OBu-n | Me2N | SBZ0131 | 0.06 | 6.09 | 97/95/99 |

| 6 | Cy | Ph | Me2N | SBZ0132 | 1.56 | 5.66 | 97/46/97 |

| 7 | Cy | 4-F-Ph | Me2N | SBZ01321 | 0.63 | 5.87 | 78/48/96 |

| 8 | Cy | 4-CF3-Ph | Me2N | SBZ01322 | 0.44 | 6.67 | 25/10/44 |

| 9 | Cy | 4-MeO-Ph | Me2N | SBZ01323 | 0.31 | 5.78 | 39/26/49 |

| 10 | Cy | 4-CHF2O-Ph | Me2N | SBZ01324 | 0.31 | 6.23 | 55/40/82 |

| 11 | Cy | 4-CF3O-Ph | Me2N | SBZ01325 | 0.16 | 6.89 | 39/14/45 |

| 12* | Cy | 4-CF3O-Ph | Me2N | SBO01325* | 6.25 | 6.74 | 56/22/71 |

| 13 | Cy | 4-CF3O-Ph | MeO | SBZ01A25 | 1.44 | 6.0 | 46/64/95 |

| 14 | Et2CH | 4-CF3O-Ph | Me2N | SBZ02325 | 0.31 | 6.76 | 68/12/45 |

| 15 | PhCH2 | 4-CF3O-Ph | Me2N | SBZ03325 | 1.25 | 6.34 | 27/81/49 |

| 16 | 4,4-F2-Cy | 4-CF3O-Ph | Me2N | SBZ01325-2F2 | 1.25 | 6.27 | 9/0/0 |

| 17 | 4,4-F2-Cy | OBu-n | Me2N | SBZ0131-2F2 | 0.63 | 5.48 | 80/55/94 |

| 18 | Cy | 4-CF3S-Ph | Me2N | SBZ01326 | 0.67 | 7.39 | 95/22/45 |

| 19 | Cy | 2,4-F2-Ph | Me2N | SBZ013201 | 0.31 | 5.63 | 55/40/64 |

| 20 | Cy | 2,4-F2-Ph | MeO | SBZ01A201 | 1.32 | 4.74 | 52/61/63 |

| 21 | Cy | 2,6-F2-4-Br-Ph | Me2N | SBZ0132021 | 1.56 | 6.09 | 52/61/63 |

| 22 | Cy | 2,6-F2-4-MeO-Ph | Me2N | SBZ0132022 | 2.5 | 5.32 | 23/20/46 |

| 23 | Cy | 2-F-4-CF3O-Ph | Me2N | SBZ013251 | 0.16/0.31 | 6.68 | 13/17/4 |

| 24 | Cy | 2-F-4-CF3-Ph | Me2N | SBZ013221 | 0.16 | 6.42 | 12/14/13 |

| 25 | Cy | 2,3-F2-4-CF3-Ph | Me2N | SBZ0132211 | 0.39 | 6.50 | 5/0/17 |

Some non-fluorine-containing benzimidazoles are listed as well for comparison purpose.

Calculated by the ChemDraw program.

Metabolic stability was determined by incubating for 4 h at 37 °C and then analyzing the samples by LC–MS/MS.

2-cyclohexyl-5-dimethylamino-6-(4-trifluorimethoxy)benzamido-1,3-benzoxazole.

Accordingly, we synthesized and examined the 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl ester derivatives of 1 and 2, i.e., SBZ0105 (3) and SBZ0125 (4), which showed considerable increase in potency (e.g., 4: MIC 0.31 μg/mL) and substantial improvements in stabilities in both human and rat (Table 1, entries 3 and 4) [28]. It is noteworthy that 4 exhibited only 1% clearance in human plasma, 20% clearance in human microsomes and 10% clearance in rat microsomes. However, the introduction of a trifluoriethyl ester did not improve the stabilities in murine plasma and microsomes.

In the meantime, we performed extensive SAR study and optimization of these early leads, 1 and 2, through systematic structural modifications at the 5 and 6 positions, keeping the cyclohexyl group at the 2 position intact [28]. This SAR study led to the identification of a highly potent lead compound, SBZ0131 (5) (MIC 0.06 μg/mL), bearing a 6-N,N-dimethylamino group (Table 1, entry 5) [28]. It was found that the introduction of an N,N-dimethylamino group in place of an N,N-diethylamino or pyrrolidinyl group at the 6 position increased the potency substantially. However, as easily anticipated, the plasma (murine: 88% clearance) and metabolic stabilities (95–99% clearance in human, rat and murine microsomes: entry 5) of this highly potent compound were poor, except for the stability in human blood plasma (6% clearance). Thus, 5 cannot be a good compound to examine in vivo although it is an excellent compound for in vitro and cell-based studies.

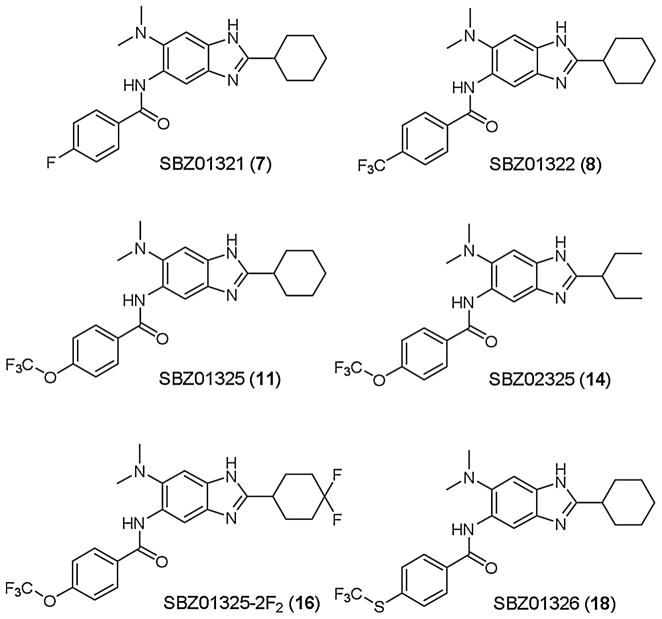

Accordingly, we turned our attention to the corresponding 5-benzamidobenzimidazoles, which should be more stable than benzimidazoles bearing a 5-carbamate group [28]. However, the most basic 5-benzamido-2-cyclohexylbenzimidazole 6 was found to be as labile as 5 in human and murine microsomes, although there was a substantial improvement (95–48% clearance) in rat microsomes (Table 1, entry 6). Therefore, we explored substituent effects on the metabolic lability of 5-benzamido-2-cyclohexyl-benzimidazoles. We introduced F, CF3, MeO, CHF2O, and CF3O groups to the 4-position of the 5-benzamido moiety of 6 to examine their effects (Fig. 4) [28]. As Table 1 (entries 7–11) shows, the 4-F group only moderately improved the stability in human microsomes, whereas the 4-CF3 group dramatically improved the stability in the microsomes of three species (entries 7 and 8). The 4-MeO group also exhibited slightly weaker but similar improvement in metabolic stability as compared to the 4-CF3 group, and increased potency (9: MIC 0.31 μg/mL) (entry 9). These results strongly suggest that the 4 position of the 5-benzamido moiety is the major site for hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 oxidases (CYPs).

Fig. 4.

Fluorine-containing benzimidazoles.

Next, we introduced 4-CHF2O and 4-CF3O groups, which are increasingly popular fluorine-containing substituents in medicinal chemistry, to examine their effects [28]. As Table 1 shows, the introduction of the 4-CHF2O group (entry 10) did not improve the metabolic stability as well as MIC as compared to the 4-MeO group, suggesting a possible lability of its C-H bond against oxidation. In contrast, the introduction of 4-CF3O group (entry 11) exhibited clear improvement in metabolic stability (39%, 14% and 45% clearance in human, rat, and murine microsomes, respectively) and MIC (0.16 μg/mL). The stability in blood plasma was also improved (0% and 24% clearance in human and murine plasma, respectively). Because of its improved plasma and metabolic stability, SBZ01325 (11), was selected for in vivo efficacy study on the acute TB model in mice [30].

Since it was found that the introduction of 4-CF3O group improved both potency and metabolic/plasma stability, we synthesized analogs of SBZ01325 (11) bearing a benzoxazole skeleton (SBO01325, entry 12), a 6-methoxy group (entry 13), a 2-(1-ethylpropyl) group (entry 14) and a 2-benzyl group (entry 15) as shown in Table 1 [28]. Among these analogs, only SBZ02325 (14) maintained high potency (MIC 0.31 μg/mL) with good stability in rat microsomes (12% clearance) (Table 1, entry 14). We also synthesized the 2-(4,4-difluorocyclohexyl) analog of 11 (SB01325-2F2: 16, Fig. 4) and examined its potency and metabolic stability (entry 16) [52]. To our surprise, the introduction of a gem-difluoromethylene group at the 4 position of the 2-cyclohexyl moiety completely shut down the metabolism by CYPs. The result clearly indicates that the cyclohexyl group at the 2 position is a site for CYP-metabolism and the 4,4-gem-difluorocyclohexyl group plays a key role in extremely high metabolic stabilization. At the same time, however, the introduction of the gem-difluorocyclohexyl group substantially reduced its potency, and thus this unique modification was not pursued further. It should be noted that the 4,4-gem-difluorocyclohexyl group alone is not responsible for the remarkable enhancement of metabolic stability, i.e., the corresponding 4,4-gem-difluorocyclohexyl analog of 11, bearing a n-butyl carbamate group at the 5 position (SBZ0131-2F2: 17, Fig. 4) [52] did not show exceptional metabolic stability, although it was considerably better than the parent SBZ0131 (5) (entry 17). In addition, we examined the effects of a 4-CF3S group on the potency and metabolic stability, as compared to that of a 4-CF3O group by synthesizing the CF3S analog of 11 (SBZ01326: 18) [52]. As Table 1 shows, the potency was only slightly affected by the CF3S group, but metabolic stability in human microsomes was dramatically reduced (95% clearance), keeping those in rat and murine microsomes at good to moderate level (22% and 45% clearance, respectively) (entry 18). The result may indicate that the oxidation of sulfur by CYP3A4 takes place in human microsomes.

SBZ01325 (11) exhibited substantially improved in vivo efficacy as compared to that of 1, but it was still far weaker than the current front line TB drug, isoniazid (INH), in an acute infection model in mice, which is mainly attributable to its insufficient metabolic stability [31]. Accordingly, we continued our SAR study and optimization of the metabolic stability of SBZ01325 series of benzimidazoles. We focused our attention to the potential blockage or mitigation of metabolism (hydroxylation/oxidation by CYPs and hydrolysis of amide by hydrolases) through substitution of the 2 position of the 5-benzamido moiety. Thus, we investigated the effect of 2-fluoro group on the metabolic stability and potency.

We synthesized 2,4-difluoro analog (19) [28], 4-bromo-2,6-difluoro analog (20) [52], and 2,6-difluoro-4-methoxy analog (21) [52] of SBZ0132 (6) and examined their potency and metabolic stability. As Table 1 shows (entries 19, 21 and 22), the introduction of a 2,6-difluorobenzamido group considerably reduced the potency and the blocking of two ortho positions of the benzamido group did not improve metabolic stability. A 4-methoxy group was more effective than 4-bromo group to increase metabolic stability. The introduction of a 6-methoxy group in place of an N,N-dimethylamino group substantially reduced potency although metabolic stability is in the same range (Table 1, entry 20) [53].

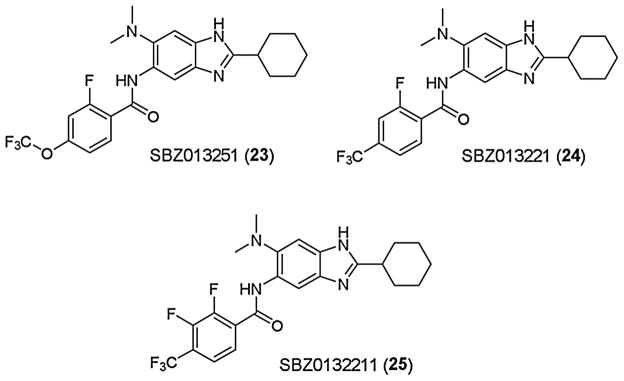

Since the introduction of a fluorine substituent at the 2 position of 5-benzamido moiety was found to be effective in improving metabolic stability without affecting potency, we synthesized the 2-fluoro analog (SBZ013251: 23) of SBZ01325 (11), as well as 2-fluoro analog (SBZ013221: 24), and 2,3-difluoro analog (SBZ0132211: 25) of SBZ01322 (8) and examined their potency and metabolic stability (Fig. 5) [32,52]. These three analogs exhibited impressive metabolic stability in human (5–13% clearance), rat (0–17% clearance) and murine (4–17% clearance) microsomes and maintained high potency (MIC 0.16–0.39 μg/kg) (Table 1, entries 23–25). SBZ013251 (23) and SBZ0132211 (25) also showed excellent stability in human (2 and 1% clearance) and murine (12 and 11% clearance) plasma. Accordingly, these three analogs were evaluated for their in vivo efficacy in an acute TB infection model in mice [32].

Fig. 5.

Highly potent fluorine-containing benzimidazoles.

Treatment with SBZ013251 (23) reduced the M. tuberculosis Erdman bacterial load in the lungs by log10 6.1/6.3 CFU via oral (PO)/Intraperitoneal (IP) administration, respectively. SBZ013221 (24) also reduced the bacterial load in the lungs by 5.6/5.8 Log10 CFU via PO/IP administration, respectively. Treatment with both 23 and 24 totally cleaned the bacteria in the spleen when the compounds were delivered either PO (>log10 4.96 CFU reduction) or IP (>log10 3.89 CFU reduction) [32]. These results are truly remarkable as novel drug lead compounds, which exhibited comparable efficacy to the gold standard anti-TB drug, INH, used as a positive control. In contrast, treatment with 25 resulted in modest 1.7/2.5 log10 CFU reduction via PO, as well as 2.1/3.4 log10 CFU reduction via IP, in bacterial load in the lungs and spleen, respectively [32]. Since 25 showed only slightly weaker potency and lower metabolic stability in mice than 23 (Table 1, entry 25), the substantial difference in their in vivo efficacies indicates a limited correlation between the MIC/metabolic stability in vitro and the activity in vivo. However, the kill characteristics of 25, compared to those of 23 and 24, clearly indicate the difference in potency, predicting poorer outcome in efficacy in vivo (see Fig. 9, Section 3.2.2.) [32]. These results demonstrate the importance of the determination of kill characteristics for antibacterial drug discovery. More detailed description and discussion on the biological evaluations are presented in Section 3.2.

3. Biological evaluations of fluorine-containing benzimidazoles as anti-TB agents, targeting Mtb-FtsZ

3.1. In vitro potency and in vivo efficacy of SBZ01325 (11)

3.1.1. In vitro potency of 11 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv and clinical strains

The MIC value for SBZ01325 (11) against a common laboratory strain of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (drug-sensitive) as well as different clinical stains of M. tuberculosis, i.e., TN587 (INH-resistant, Kat G S315T mutation) [54], NHN382 (INH-resistant, Kat G-Del) [54], W210 (Kat G wild type) and NHN20 (INH-resistant) is 0.16 μg/mL based on the microplate Alamar Blue assay (MABA) [27,51]. The results clearly indicate that 11 is equally potent against drug-sensitive and drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis [30]. The antibacterial activity was found to be concentration dependent with a typical sigmoidal curve. Also, there was no difference in kill characteristics among the different M. tuberculosis strains and clinical isolates [31]. These results strongly suggest that Mtb-FtsZ is a novel target and the inhibitors of this target can completely circumvent the resistance to existing anti-TB drugs. Also, 11 is not cytotoxic (IC50 > 100 μM) to Vero cells [30].

3.1.2. Frequency of resistance (FOR) assessment

In order to examine potential drug resistance caused by genetic mutations upon exposure of bacteria to drugs in the case of benzimidazole-based Mtb-FtsZ inhibitors, M. tuberculosis H37Rv (26,000 cells) was plated on 1.6 μg/mL of 11, which is 10 times the experimentally determined MIC value (0.16 μg/mL) as mentioned above. This is a standard method to determine the “frequency of resistance”, i.e., probability of the occurrence of a mutation in the bacterial population that provides a selective advantage upon exposure to a drug, conferring resistance. No mutants were observed, and no single resistant colony was obtained, either. Thus, the FOR should be extremely low [30].

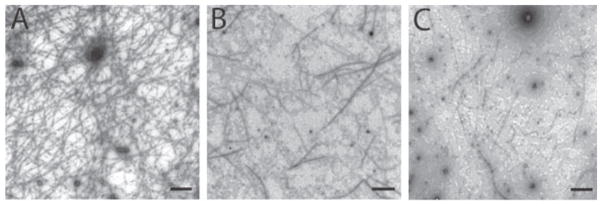

3.1.3. Mtb-FtsZ-polymerization inhibitory activity

As mentioned above, the early lead compound 1 was found to inhibit the polymerization of Mtb-FtsZ in dose-dependent manner, which clearly indicated that Mtb-FtsZ was the molecular target of 1 and constituted the most important mode of action (MOA) for this novel class of anti-TB agents. To confirm that a more potent lead 11 shares the same MOA, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of Mtb-FtsZ treated with 11 were taken to examine the ability of 11 to inhibit the polymerization and aggregation of Mtb-FtsZ [30]. As Fig. 6 shows, the treatment of Mtb-FtsZ (5 μM) with 11 at 40 μM following addition of GTP (25 μM) produced fewer, shorter and thinner FtsZ polymers (Fig. 6B) as compared to control, i.e., untreated protein (Fig. 6A). The inhibitory effect at 80 μM was even more remarkable, wherein only a few dispersed FtsZ polymers and aggregates of FtsZ nucleates were observed (Fig. 6C). These studies confirm that Mtb-FtsZ is the molecular target of 11, as anticipated for this class of novel benzimidazoles [30].

Fig. 6.

TEM images of Mtb-FtsZ. FtsZ (5 μM) was polymerized by GTP (25 μM) in the absence (A) and presence of 11 at 40 μM (B) and 80 μM (C). Images are at 49,000 × magnification (scale bar 500 nm). Adapted from Reference [30].

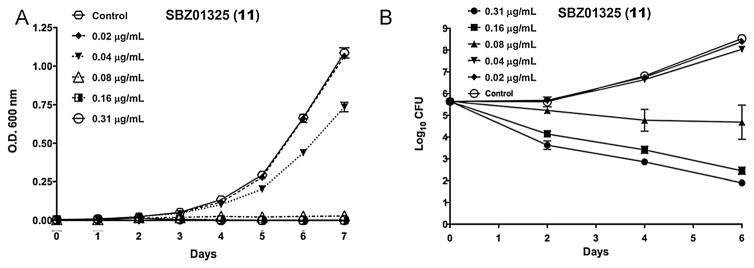

3.1.4. Killing characteristics of 11 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv

To examine the killing characteristics of 11, the bacterial growth of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the bactericidal effect of 11 were monitored by OD600 nm over 7 days in the presence of different concentrations of 11 (Fig. 7) [30]. As Fig. 7A shows, 11 is a concentration-dependent anti-TB agent. It is noteworthy that bacterial growth was affected by sub-MIC concentrations (0.16–0.02 μg/mL) of 11 (Fig. 4A). As Fig. 7B clearly indicates, 11 is bactericidal even at a sub-MIC concentration (0.08 μg/mL).

Fig. 7.

Killing characteristics of 11 against whole bacteria. The time dose curves were generated from OD600 nm (a) and from CFU enumeration (b) data. Different concentrations of the compound were tested in triplicate and the mean and standard deviation of the OD600 nm values or the CFU counts from Day 0, 2, 4, and 6 were plotted against time using GraphPad Prism Version 5.0d. Adapted from Reference [30].

3.1.5. In vivo efficacy of 11 in an acute TB infection model in mice

The in vivo efficacy of 11 was evaluated in an acute murine model of TB infection with C57BL/6-Ifngtm1ts (GKO) mice (Jackson Laboratories) using 50 mg/kg dose twice a day (b.i.d) via IP administration (Fig. 8) [30]. INH was used as a control via IP using 20 mg/kg does once a day (qd). In this acute model, all mice treated with 11 reduced the bacterial load by 1.7 log10 CFU (p value, 0.0001) in the lungs and that by 2.7 log10 CFU (p value 0.0002) in the spleen with one mouse having no detectable bacteria at the lowest level of detection [30]. It should be noted that 11 is the first lead compound in this class exhibited significant in vivo efficacy in both the lungs and spleen, as a result of the strategic incorporation of an organofluorine group.

Fig. 8.

Efficacy of 11 in an acute murine model of TB infection. Scatter plot of the CFU counts from the lung and spleens of infected mice after drug therapy with 11 delivered IP at 50 mg/kg b.i.d. The colony counts were converted to logarithms. The lower level of detection was 1 log10 CFU. Outliers were identified by the Grubbs’ Test using an online calculator (GraphPad Software). A scatter plot of the CFU data from the lung and spleen of individual mice from the treatment and control groups were plotted with the mean and SE from each group using GraphPad Prism Version 5.0d. Adapted from Reference [30].

3.2. In vitro potency and in vivo efficacy of SBZ013251 (23), SBZ013221 (24) and SBZ0132211 (25)

3.2.1. In vitro potency of 23, 24 and 25 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv and clinical strains

As Table 2 shows, advanced lead compounds, 23, 24 and 25, are almost equally potent (24 is the most potent with MIC 0.18 μg/mL) against M. tuberculosis H37Rv and clinical strains with different level of drug resistance, in a similar manner to 11 and other lead compounds in this series [32]. Also, the cytotoxicities of these three lead compounds are negligible (IC50 > 200 μM) in Vero cells [32]. The growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis H37Rv by these three lead compounds was sigmoidal and concentration-dependent, which are indicative of in vivo efficacy, as exemplified in the case of 11, described above.

Table 2.

In vitro anti-TB activity of 23, 24 and 25 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv and clinical strainsa (MIC μg/mL).

| Benzimidazoles | H37RV | NHN382 | TN587 | W210 | NHN20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBZ013251 (23) | 0.31 ± 0.22 | 0.31 ± 0 | 0.31 ±0 | 0.47 ±0.22 | 0.24 ±0.11 |

| SBZ013221 (24) | 0.16 ±0.1 | 0.16 ±0 | 0.24 ±0.11 | 0.31 ±0 | 0.16 ±0 |

| SBZ0132211 (25) | 0.39 ± 0.16 | 0.37 ± 0.24 | 0.31 ± 0 | 0.47 ± 0.22 | 0.39 ± 0.33 |

For the resistance characteristics of these clinical strains, see Section 3.1.1.

3.2.2. Killing characteristics of 23, 24 and 25 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv

The killing characteristics of 23, 24 and 25 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv were determined by monitoring the time course of bacterial growth and their bactericidal effect in the presence of these Mtb-FtsZ inhibitors over 7 days in the same manner as that described for 11 (see Section 3.1.4) [32]. Results are summarized in Fig. 9. It is clear that all three lead compounds are dose-dependent anti-TB agents. SBZ013251 (23) reduced the number of viable bacteria by 2.8 log10 CFU at 1× MIC by day 2 and by 2.9 log10 CFU at day 6 (Fig. 9d). SBZ013221 (24) reduced the number of bacteria by 2.5 log10 CFU at day 2 at 1× MIC and continued to reduce the number through day 6 by almost 4 log10 CFU (Fig. 9e). SBZ0132211 (25) exhibited weaker bactericidal activity reducing the bacterial load only by 0.8–1.7 log10 CFU in the first 2 days when dosed at the MIC level (Fig. 9f). Furthermore, 25 required 3–6× MIC concentration to achieve the same level of bacterial viability, i.e., 3.6–4.4 log10 CFU reduction in bacterial load, as that with 23 or 24 at 1× MIC (Fig. 9f). Accordingly, it was anticipated that there would be substantial difference in the in vivo efficacy between 25 and 23 or 24 in an acute TB infection model in mice.

Fig. 9.

Killing characteristics of 23, 24 and 25. Separate curves were generated for each compound. The time dose curves were generated from OD600nm (a–c) and from CFU enumeration (d–f) data. Different concentrations of the compound were tested in triplicate and the mean and standard deviation of the OD600nm values or the CFU counts from Day 0, 2, 4, and 6 were plotted against time using GraphPad Prism Version 5.0d (GraphPad Software).

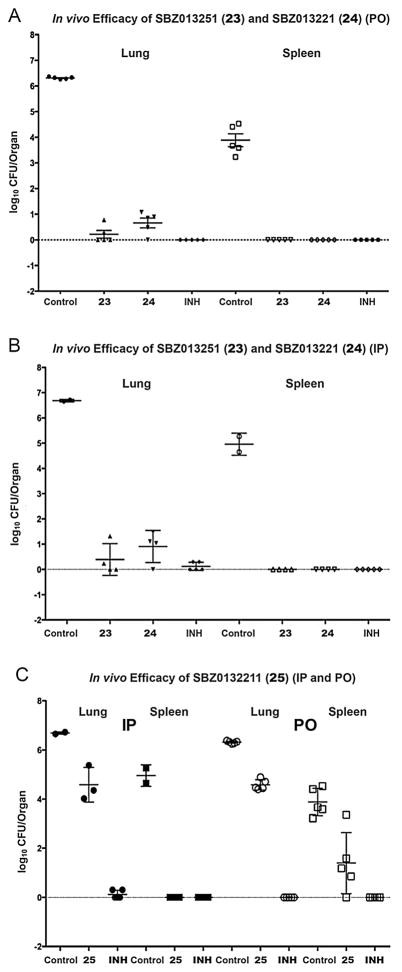

3.2.3. In vivo efficacy of 23, 24 and 25 in a TB murine model of infection

The in vivo efficacy of 23, 24 and 25 were evaluated in an acute infection model of M. tuberculosis Erdman in C57BL/6-Ifngtm1ts (GKO) mice (Jackson Laboratories), in a manner similar to the case of 11 described in the Section 3.1.5 [32]. Results are summarized in Table 3 and data plots are shown in Fig. 10. Each test compound was delivered at 50 mg/kg dose via IP and PO twice a day (b.i.d), starting on day 5 post infection till the endpoint of day 15 [32]. SBZ013251 (23) reduced the bacterial load in the lungs by log10 6.1 CFU via PO and log10 6.3 CFU via IP (Table 3, entries 3 and 4). In one of the 5 animals treated with 23 via PO and one of the 4 animals treated with 23 via IP, the lungs appeared clear. In a similar manner, 24 reduced the bacterial load in the lungs by 5.6 Log10 CFU via PO and 5.8 log10 CFU via IP, respectively (entries 5 and 6). In one of the 5 animals treated with 24 via PO, the lungs appeared clear, but all of the animals treated with 24 via IP had some counts in the lungs (Fig. 10A and B). It is worthy of note that 23 and 24 demonstrated efficacy comparative to the front-line and gold standard anti-TB drug, INH, which was delivered via IP at 20 mg/kg dose once a day (q.d.) as a positive control (entries 9 and 10) [32]. Further, there were no detectable bacteria in the spleen of mice groups treated with 23 and 24 either via PO or IP. treated groups when delivered either IP or PO (Fig. 10A and B). In contrast, treatment with 25 resulted in a statistically significant but modest reductions in bacterial load in the lungs and spleen, i.e., 1.7 and 2.5 log10 CFU (via PO); 2.1 and 3.4 log10 CFU (via IP), respectively (entries 7 and 8; Fig. 10C) [32].

Table 3.

In vivo efficacy of 23, 24 and 25 in an acute murine model of TB infection via IP or PO b.i.d.

| Entry | Benzimidazole | Route | log10 CFU Lungs | Δ | log10 CFU Spleen | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | IP | 6.69 ± 0.05 n = 2 | N/A | 4.96 ± 0.43 n = 2 | N/A |

| 2 | PO | 6.31 ± 0.04 n = 5 | N/A | 3.89 ± 0.56 n = 5 | N/A | |

| 3 | SBZ013251 (23) | IP | 0.39 ± 0.63 n = 4 | −6.30 | 0 ± 0 n = 4 | −4.96 |

| 4 | PO | 0.22 ± 0.34 n = 5 | −6.10 | 0 ± 0 n = 5 | −3.89 | |

| 5 | SBZ013221 (24) | IP | 0.91 ± 0.64 n = 4 | −5.78 | 0 ± 0 n = 4 | −4.96 |

| 6 | PO | 0.66 ± 0.43 n = 5 | −5.65 | 0 ± 0 n = 5 | −3.89 | |

| 7 | SBZ0132211 (25) | IP | 4.59 ± 0.71 n = 3 | −2.10* | 1.60 ± 0.0 n = 3 | −3.36 |

| 8 | PO | 4.58 ± 0.21 n = 5 | −1.72 | 1.40 ± 1.24 n = 5 | −2.49 | |

| 9 | INH | IP | 0.12 ± 0.16 n = 5 | −6.57 | 0 ± 0 n = 5 | −4.96 |

| 10 | PO | 0 ± 0 n = 5 | −6.31 | 0 ± 0 n = 5 | −3.89 |

n = number of animals survived. Δ = difference in log10 CFU between the means from the test and control groups: p values < 0.001 unless otherwise noted.

p value < 0.01.

Fig. 10.

In vivo efficacy data for 23, 24 and 25 in an acute murine model of TB infection.

4. Computational docking study on the putative binding site of the advanced lead SBZ013251 (23) in Mtb-FtsZ

4.1. Docking study on the putative binding site of 23 in Mtb-FtsZ

4.1.1. Mtb-FtsZ head-to-tail longitudinal model structure

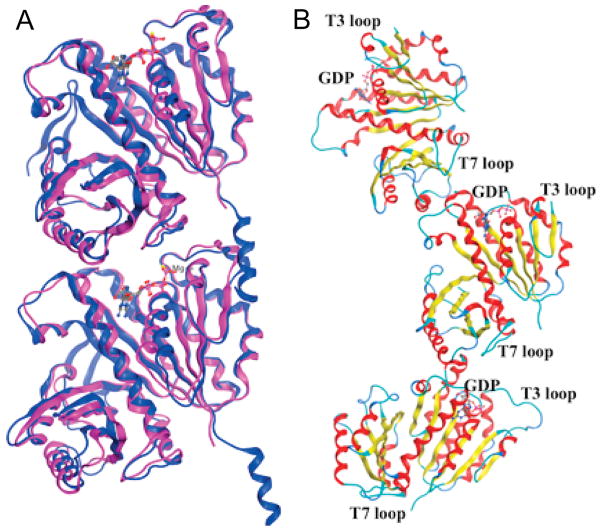

In order to understand the molecular basis of the MOA of the highly efficacious novel anti-TB drug lead compounds, targeting Mtb-FtsZ described above, we performed molecular modeling study using computational docking methods. In this study, we first constructed a key Mtb-FtsZ longitudinal dimer model based on the protein X-ray crystallography data of the head-to-head lateral dimers of Mtb-FtsZ, as well as the head-to-tail longitudinal dimer of Methanococcus jannacschii FtsZ (Mj-FtsZ). Curved head-to-tail trimer of GDP-bound Mtb-FtsZ crystal structure was also used in this study.

The protein crystal structures of head-to-head lateral dimers of Mtb-FtsZ with GTPγS (1RLU), GDP (1RQ7) and citrate (1RQ2) are available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [12]. However, no crystal structure of head-to-tail dimer of Mtb-FtsZ has been reported to date. Nevertheless, the crystal structure of head-to-tail dimer of Mj-FtsZ is available (1W5A) [18]. Our preliminary global docking study to identify potential binding sites of benzimidazole-based FtsZ inhibitors in the 1RLU and 1RQ7 structures, using AutoDock [55] and Dock [56] programs, indicated that a binding site near the nucleotide binding site was the most promising. Since it has been shown that the novel benzimidazole-based FtsZ inhibitors accelerate the GTPase activity of Mtb-FtsZ and destabilize FtsZ polymers, it was quite reasonable that the binding site near the GTP binding site was identified through a global docking study. As the GTP binding site in Mtb-FtsZ is located at the interface of the head-to-tail longitudinal dimer, there was a clear need to construct a head-to-tail dimer model through protein alignment of the crystal structures of GTPγS-bound Mtb-FtsZ (1RLU) [12] and GTP-bound Mj-FtsZ (1W5A) [18]. As Fig. 11A shows, the alignment of Mtb-FtsZ and Mj-FtsZ, using the MOE program (ver. 2015.10) is excellent (rsmd ~1.4 Å). This is not surprising because FtsZ is a highly conserved protein essential for cell division among a variety of bacterial species. In a similar manner, a GDP-bound FtsZ head-to-tail dimer model was constructed by protein alignment of GDP-bound Mtb-FtsZ (1RQ7) and GTP-bound Mj-FtsZ (1W5A). We also used the crystal structure of a GDP-bound curved Mtb-FtsZ trimer (4KWE) [57] (Fig. 11B) for docking in connection to the proposed mode of action for these FtsZ inhibitors, blocking the polymerization of FtsZ monomers and destabilizing FtsZ polymers, as discussed below.

Fig. 11.

(A) Protein alignment of GTPγS-bound Mtb-FtsZ (1RLU, purple) and GTP-bound Mj-FtsZ (1W5A, blue); (B) Crystal structure of curved head-to-tail trimer of GDP-bound Mtb-FtsZ (4KWE). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

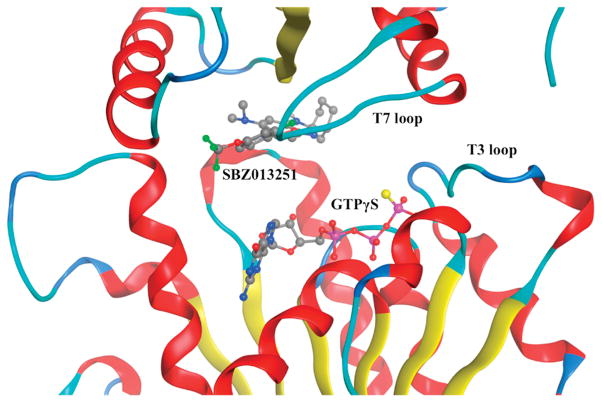

4.1.2. Mtb-FtsZ dimer model structure bound to FtsZ-inihibitor SBZ013251 (23) and GTPγS

SBZ013251 (23) was docked to the Mtb-FtsZ head-to-tail dimer model (Fig. 11A) and the best docking energy was scored using the MOE program [58]. Fig. 12 shows the docking site and docking pose of 23, as well as its relative position to GTPγS. The docking energy score is −8.49 kcal/mol and the distance to GTPγS is ~5 Å. Fig. 13 illustrates the 2D interaction diagram of 23 with the amino acid residues in the binding site. As Figs. 12 and 13 indicate, FtsZ-inhibitor 23 binds to the hydrophobic interface of two FtsZ subunits, very close to the T7 loop, which is known to be critical to FtsZ’s GTPase activity. Also, its closeness to the phosphate moieties of GTPγS strongly imply plausible mechanisms to accelerate GTP hydrolysis through more detailed analysis.

Fig. 12.

Docked pose of SBZ013251 (23) with GTPγS-bound Mtb-FtsZ head-to-tail dimer model.

Fig. 13.

2D interaction diagram of 23 with GTPγS-bound Mtb-FtsZ head-to-tail dimer model.

4.1.3. Plausible mode of action for the benzimidazole-based Mtb-FtsZ inhibitors

Li et al. reported the structure of novel curved head-to-tail trimer of Mtb-FtsZ and proposed that FtsZ protofilaments use a “hinge-opening” mechanism for the generation of constrictive force for Z-ring contraction in bacterial cell division [57]. The proposed mechanism provided a strong basis for us to deduce a highly plausible MOA of the benzimidazole-based FtsZ inhibitors. Fig. 14 illustrates our proposed mechanism or MOA of FtsZ inhibitors that block the polymerization of FtsZ monomers and protofilaments, as well as destabilize FtsZ polymers. Under a normal bacterial cell division process, GTP binds to FtsZ monomers to promote the formation of FtsZ protofilaments and straight FtsZ polymers. When the length of a FtsZ polymer reaches certain length, GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP to form a curved FtsZ polymer for Z-ring formation and constriction. However, in the presence of the benzimidazole-based FtsZ inhibitors, which binds to FtsZ close to the GTP biding site and accelerate the GTP hydrolysis, FtsZ monomers and nucleates cannot form normal straight FtsZ protofilaments and polymers. The fact that this type of FtsZ inhibitors can degrade preformed FtsZ polymers strongly indicates the ability of the FtsZ inhibitors to interact with GTP-bound FtsZ polymers, enhancing the GTPase activity of FtsZ to hydrolyze GTP to GDP and further degrading FtsZ polymers.

Fig. 14.

Proposed mode of action for the benzimidazole-based Mtb-FtsZ inhibitors. Adapted from Reference [57] with permission and modified.

To further probe this proposed MOA, FtsZ inhibitor 23 was docked to the “hinge-opened” GDP-bound dimer unit of the curved Mtb-FtsZ trimer. There were two possible binding sites, i.e., one site very close to GDP (Fig. 15A) and the other close to the T7 loop (Fig. 15B) with docking scores −7.18 kcal/mol and −7.09 kcal/mol, respectively. Accordingly, the interactions of 23 with the “hinge-opened” FtsZ dimer unit appear to be considerably weaker than those with the head-to-head longitudinal FtsZ dimer. Nevertheless, 23 may still contribute to the further destruction of FtsZ protofilaments. Also, we have found that 23 binds to the GDP-bound FtsZ head-to-tail dimer model strongly with energy score −8.89 kcal/mol (Fig. 15C). This might suggest that this type of FtsZ inhibitors trigger the degradation of FtsZ architecture via the “hinge-opening” or another destabilization mechanism, which does not need to involve GTP hydrolysis.

Fig. 15.

Docked poses of SBZ013251 (23) to (A) “hinge-opened” dimer unit of the curved GDP-bound Mtb-Ftz trimer, close to the GDP binding site; (B) “hinge-opened” dimer unit of the curved GDP-bound Mtb-Ftz trimer, close to the T7 loop; (C) the binding pocket between the T7 loop and GDP binding site in the head-to-tail longitudinal GDP-bound Mtb-FtsZ dimer model.

5. Conclusions

Emergence of severe drug resistance to currently available anti-TB drugs is imposing a serious threat to human health worldwide. Most of anti-TB drugs target cell wall biosynthesis, nucleic acid synthesis and protein synthesis. In the last decade, FtsZ, an essential protein for bacterial cell division and growth has emerged as a highly promising new molecular target for the discovery of novel antibacterial agents. FtsZ is a highly conserved and ubiquitous bacterial protein that plays a critical role in bacterial cytokinesis. Thus, the inhibition of FtsZ assembly causes the disruption of septum formation and bacterial cell division, leading to cell death. Since FtsZ is a totally new target for anti-TB agents, the FtsZ-inhibitors should not have any resistance to the drug-resistant strains for clinically used anti-TB drugs at present. We found that novel benzimidazoles inhibited the nucleation/aggregation/polymerization of Mtb-FtsZ effectively in a dose-dependent manner through enhancement of its GTPase activity through design and synthesis of compound libraries, as well as semi-HTP screening. For the optimization of lead anti-TB benzimidazoles, we have extensively investigated the strategic incorporation of fluorine and organofluorine groups into these lead compounds in order to increase the potency against drug-sensitive and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains, as well as enhance metabolic and plasma stabilities. As described above, we have successfully developed highly efficacious fluorine-containing benzimidazoles as potential new-generation anti-TB agents through these concentrated efforts.

Two novel fluorine-containing FtsZ-inhibitors, SBZ013251 (23) and SBZ13221 (24), exhibited impressive in vivo efficacy, equivalent to that of the gold standard anti-TB drug, isoniazid (INH), against M. tuberculosis Erdman in an acute murine model of TB infection, as well as the same high potency against drug-sensitive and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains. The latter results confirm that FtsZ-inhibitors are indeed effective against M. tuberculosis strains resistant to the currently used anti-TB drugs. As the CLogP values in Table 1 indicate, these highly potent advanced lead compounds are hydrophobic, which require formulations using excipients for solubilization. Thus, the optimization efforts are continuing to lower the CLogP values, including further modifications and prodrug approaches as well as nano-formulations.

We have also performed computational docking study to identify putative binding site of SBZ013251 (23) bearing one fluorine and one trifluoromethoxy group, using the MOE program, which has led to a plausible unique mode of action for this class of novel FtsZ-inhibitors, which block the polymerization of FtsZ monomers and protofilaments, as well as destabilize and degrade FtsZ polymers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI078251 and U01 AI082164), and the New York State Office of Science, Technology and Academic Research (NYSTAR). The authors thank Professor Richard A. Slayden and Dr. Susan E. Knudson of the Colorado State University for their productive collaboration. The authors also acknowledge Drs. Laurent Goullieux, Alexandra Carreau, Sophie Lagrange and Héléne Vermet of Sanofi-Aventis R&D for their collaboration on preclinical studies.

Footnotes

This article is dedicated to Professor Steven H. Strauss on the occasion of his 2016 ACS Award for Creative Work in Fluorine Chemistry.

References

- 1.Fact sheet. World Health Organization; 2016. Tuberculosis. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2015. 2016 http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2015_executive_summary.pdf?ua=2011.

- 3.Bloom BR, Murray CJ. Tuberculosis: commentary on a reemergent killer. Science. 1992;257:1055–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuberculosis Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. TB facts. 2016 http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.html.

- 5.Kumar K, Awasthi D, Berger WT, Tonge PJ, Slayden RA, Ojima I. Future Med Chem. 2010;2:1305–1323. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margalit DN, Romberg L, Mets RB, Hebert AM, Mitchison TJ, Kirschner MW, RayChaudhuri D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404439101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vollmer W. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;73:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Q, Tonge Peter J, Slayden Richard A, Kirikae T, Ojima I. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:527–543. doi: 10.2174/156802607780059790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojima I, Kumar K, Awasthi D, Vineberg JG. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:5060–5077. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Yehuda S, Losick R. Cell. 2002;109:257–266. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goehring NW, Beckwith J. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R514–R526. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung AK, White LE, Ross LJ, Reynolds RC, DeVito JA, Borhani DW. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:953–970. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moller-Jensen J, Loewe J. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thanedar S, Margolin W. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Q, Kirikae F, Kirikae T, Pepe A, Amin A, Respicio L, Slayden RA, Tonge PJ, Ojima I. J Med Chem. 2006;49:463–466. doi: 10.1021/jm050920y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Respicio L, Nair PA, Huang Q, Burcu AB, Tracz S, Truglio JJ, Kisker C, Raleigh DP, Ojima I, Knudson DL, Tonge PJ, Slayden RA. Tuberculosis. 2008;88:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slayden RA, Knudson DL, Belisle JT. Microbiology. 2006;152:1789–1797. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28762-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliva MA, Cordell SC, Lowe J. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1243–1250. doi: 10.1038/nsmb855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haranahali K, Tong S, Ojima I. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016;24 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.05.003. E-pub ahead of print, 5/5/2016 org/2010.1016/j.bmc.2016.2005.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awasthi D, Kumar K, Ojima I. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2011;21:657–679. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.568483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Artola M, Ruiz-Avila LB, Vergonos A, Huecas S, Araujo-Bazan L, Martin-Fontecha M, Vazquez-Villa H, Turrado C, Ramirez-Aportela E, Hoegl A, Nodwell M, Barasoain I, Chacon P, Sieber SA, Andreu JM, Lopez-Rodriguez ML. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:834–843. doi: 10.1021/cb500974d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Ma S. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;95:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beuria TK, Singh P, Surolia A, Panda D. J Biochem. 2009;423:61–69. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White EL, Suling WJ, Ross LJ, Seitz LE, Reynolds RC. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:111–114. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds RC, Srivastava S, Ross LJ, Suling WJ, White EL. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:3161–3164. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh D, Bhattacharya A, Rai A, Dhaked HPS, Awasthi D, Ojima I, Panda D. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2979–2992. doi: 10.1021/bi401356y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar K, Awasthi D, Lee SY, Zanardi I, Ruzsicska B, Knudson S, Tonge PJ, Slayden RA, Ojima I. J Med Chem. 2011;54:374–381. doi: 10.1021/jm1012006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awasthi D, Kumar K, Knudson SE, Slayden RA, Ojima I. J Med Chem. 2013;56:9756–9770. doi: 10.1021/jm401468w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar K, Awasthi D, Lee SY, Cummings JE, Knudson SE, Slayden RA, Ojima I. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:3318–3326. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knudson SE, Awasthi D, Kumar K, Carreau A, Goullieux L, Lagrange S, Vermet H, Ojima I, Slayden RA. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudson SE, Kumar K, Awasthi D, Ojima I, Slayden RA. Tuberculosis. 2014;94:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knudson SE, Awasthi D, Kumar K, Carreau A, Goullieux L, Lagrange S, Vermet H, Ojima I, Slayden RA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:3070–3073. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laeppchen T, Hartog AF, Pinas VA, Koomen GJ, Den Blaauwen T. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7879–7884. doi: 10.1021/bi047297o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paradis-Bleau CB, Beaumont M, Sanschagrin F, Voyer N, Levesque RC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:1330–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parhi A, Lu S, Kelley C, Kaul M, Pilch DS, LaVoie EJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:6962–6966. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beuria TK, Santra MK, Panda D. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16584–16593. doi: 10.1021/bi050767+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathew B, Ross L, Reynolds RC. Tuberculosis. 2013;93:398–400. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parhi A, Kelley C, Kaul M, Pilch DS, LaVoie EJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:7080–7083. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haydon DJ, Stokes NR, Ure R, Galbraith G, Bennett JM, Brown DR, Baker PJ, Barynin VV, Rice DW, Sedelnikova SE, Heal JR, Sheridan JM, Aiwale ST, Chauhan PK, Srivastava A, Taneja A, Collins I, Errington J, Czaplewski LG. Science. 2008;321:1673–1675. doi: 10.1126/science.1159961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haydon DJ, Bennett JM, Brown D, Collins I, Galbraith G, Lancett P, Macdonald R, Stokes NR, Chauhan PK, Sutariya JK, Nayal N, Srivastava A, Beanland J, Hall R, Henstock V, Noula C, Rockley C, Czaplewski L. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3927–3936. doi: 10.1021/jm9016366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plaza A, Keffer JL, Bifulco G, Lloyd JR, Bewley CA, Chrysophaentins A-H. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9069–9077. doi: 10.1021/ja102100h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathew B, Srivastava S, Ross LJ, Suling WJ, White EL, Woolhiser LK, Lenaerts AJ, Reynolds RC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:7120–7128. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ojima I. Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Begue JP, Bonnet-Delpon D. J Fluorine Chem. 2006;127:992–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isanbor C, O’Hagan D. J Fluorine Chem. 2006;127:303–319. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Sánchez-Roselló M, Aceña JL, del Pozo C, Sorochinsky AE, Fustero S, Soloshonok VA, Liu H. Chem Rev. 2014;114:2432–2506. doi: 10.1021/cr4002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cottet F, Marull M, Lefebvre O, Schlosser M. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:1559–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirk KL. J Fluorine Chem. 2006;127:1013–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamazaki T, Taguchi T, Ojima I. In: Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Ojima I, editor. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester: 2009. pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins L, Franzblau SG. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1004–1009. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Awasthi D. PhD Thesis. Stony Brook University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park B. PhD Thesis. Stony Brook University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boyne ME, Sullivan TJ, amEnde CW, Lu H, Gruppo V, Heaslip D, Amin AG, Chatterjee D, Lenaerts A, Tonge PJ, Slayden RA. Antimicro Agent Chemother. 2007;51:3562–3567. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00383-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. J Comput Chem. 2009;16:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DOCK6.5, DOCK6.5. University of California; San Francisco: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, Hsin J, Zhao L, Cheng Y, Shang W, Huang KC, Wang HW, Ye S. Science. 2013;341:392–395. doi: 10.1126/science.1239248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chemical Computing Group Inc. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2015.10. 2015. [Google Scholar]