History of Present Illness

At the time of her initial presentation to a reproductive psychiatry clinic in 2015, “Ms. P” was a 30 year old, divorced female at approximately 8 weeks gestation with her fifth child. She presented on referral from her obstetrician regarding chronic use of prescription opioid medication. The patient was in her usual state of health until 2008 when she was in a motor vehicle accident and fractured her coccyx bone and began to experience pelvic and neck pain. Following the accident, her primary care physician prescribed Hydrocodone for pain. She was maintained on Hydrocodone with dosage increases until 2014 when she was switched to Oxycodone due to inadequate pain control.

On presentation, Ms. P was taking Oxycodone 10mg Q4 hours (60mg Morphine Equivalent Dose) as prescribed and reported inadequate pain control with a negative impact on ability to work and care for her four children. She and the father of the baby expressed concern about the use of Oxycodone during pregnancy. When she learned she was pregnant, she stopped her Oxycodone abruptly and experienced significant withdrawal symptoms. She then resumed her usual dose and tried to cut down on the medication dose, but was unsuccessful. She endorsed a strong urge to use Oxycodone, but was requesting help in discontinuing the medication during pregnancy.

Ms. P reports that in the past two years she has frequently run out of Oxycodone before the next refill because of increasing the dosage on her own. She denies ever obtaining Oxycodone illegally and reported she generally can find a physician to refill her Oxycodone early and increase her dosage when requested. She reports feeling preoccupied with concerns that she may run out of Oxycodone and spends significant time attending doctor's appointments to acquire Oxycodone at the expense of time with her children and other activities. She has tried on three prior occasions to cut down or discontinue Oxycodone without success. Each month she becomes anxious and irritable because of fear of running out of Oxycodone which often results in arguments with the father of the baby and being “very short” with her children. She reports significant strain on her relationship with her mother who feels that she is a different person since initiating these medications. Her mother currently refuses to have a relationship with the patient if she continues to use prescription opioids. Review of the South Carolina State Prescription Drug Monitoring Program database reflects four different providers of Oxycodone in different medical practices, multiple early refills of medication and increasing dosage of Oxycodone over time, but no overlapping prescriptions. The patient denies any use or abuse of alcohol, tobacco, illicit or other prescribed substances.

Ms. P's Brief Pain Inventory(1) indicated that her average pain was a 6/10 and worst pain was 7/10 in the past 24 hours. Her current dose of Oxycodone was providing 10% pain relief. She also indicated significant impairment 7/10-10/10 in seven domains of functioning including general activity, walking, work, mood, enjoyment in life, relationships and sleep. Her Current Opioid Misuse Measure(2) was 31 (highly suggestive of opioid misuse). Urine drug testing was negative for amphetamines, barbiturates, cocaine, marijuana, methadone, phencyclidine and opioids, but confirmatory testing revealed Oxycodone.

Assessment of Pertinent and Challenging Clinical Issues

Ms. P's presentation is consistent with an Opioid Use Disorder of moderate severity as evidenced by escalating amounts of opioid use, unsuccessful attempts to quit or cut down her opioid use, continued use of opioids despite persistent interpersonal problems, opioid cravings, and spending an excessive amount of time obtaining opioid medications.

The pharmacological treatment for prescription opioid use disorder in pregnancy is controversial. The standard of care for women with heroin use disorder in pregnancy, established over 30 years ago, is treatment with opioid agonist therapies such as methadone or buprenorphine, as opposed to medication-assisted withdrawal.(3) One rationale for this approach is that a repeated cycle of withdrawal and relapse, which is often seen in opiate use disorder when individuals attempt to go “cold turkey” would be worse for the developing fetus than a stable dose of prescribed opioids. However, with exposure throughout pregnancy to opioid maintenance medications, there is a 60-80% incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome,(4) often requiring a stay in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. It is unclear, however if maintenance medications, as opposed to medication-assisted withdrawal, should be the standard of care for pregnant women with prescription opioid use disorder(5) and if so, how best to taper these medications.

This case is further complicated by a chronic pain condition that could potentially worsen with the discontinuation of Oxycodone and the progression of pregnancy. While there is evidence to support nonpharmacological (exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy) and nonopioid pharmacological treatments (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) for musculoskeletal pain in non-pregnant populations, the effectiveness of these therapies in pregnancy are unknown. Further, the use of NSAIDs during pregnancy carry significant risks and patients frequently report poor response to acetaminophen.

Treatment Plan and Course

Shared-decision making is a collaborative process between the provider and patient to make health-care related decisions when there is more than one medically reasonable option.(6) For Ms. P, shared-decision making techniques were used to guide overall treatment choice and weekly medication management decisions. The clinician first provided available evidence related to medication-assisted withdrawal and opioid maintenance medications, methadone and buprenorphine, for pregnant women with opioid use disorder. The patient discussed her values and preferences, including her preference to not take maintenance medication due to difficulties with access, cost and concern for potential harms to her fetus and newborn. While she preferred to stop prescription opioid medications, she felt she needed treatment for her pain condition, especially in the absence of opioid medication. We discussed evidence-based opioid-alternative pain interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Chronic Pain(7,8) which has demonstrated a reduction in chronic pain severity and improvement in functioning among non-pregnant populations.(8,9)

The patient, father of the baby, psychiatrist and obstetrician agreed that the patient's medications would be tapered slowly each week(10) in conjunction with CBT for Chronic Pain and routine obstetrics care. Opioid risk mitigation strategies such as a patient-physician agreement, monitoring of misuse behaviors, weekly review of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program database and urine drug screens with confirmatory testing of prescribed opioids would be employed to maximize patient safety and minimize opioid risks.

Treatment included a total of 7, 60-90 minute weekly sessions of CBT for Chronic Pain and medication management. Each week the provider assessed for symptoms of withdrawal,(11) and pain level,(1) discussed the patient's readiness to adjust her medications and arrived at a decision to either reduce or continue the current opioid medication dose. During the weekly CBT sessions, the father of the baby cared for Ms. P's children and therefore, unable to attend these appointments. However, at Ms. P's request, following each session, Ms. P, the father of the baby and provider would discuss in-person or via speaker phone the treatment plan for the next week. Ms. P felt this made her more likely to adhere to the prescribed medication regime and strategies were discussed for how the father of the baby could support her in making positive changes.

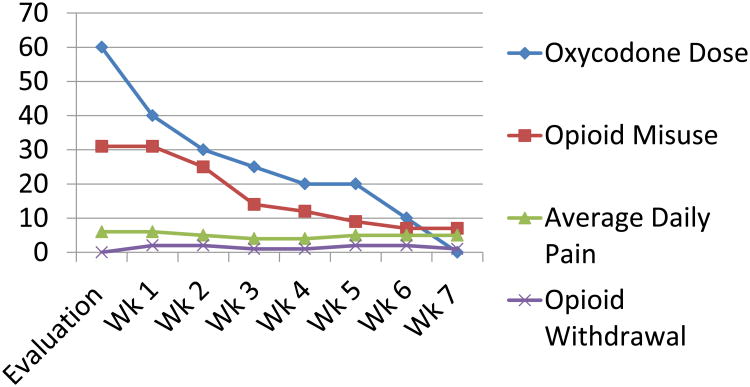

On average, the Oxycodone dose was decreased by 5-10mg per week except for week 4-to-5 when the patient was experiencing significant pregnancy related nausea (Figure 2). The small adjustments appeared to have subtle positive physiological and psychological effects and increased self-efficacy around opioid cessation. Between 6-to-7 weeks of therapy, the patient decided to stop her Oxycodone 5mg BID and experienced mild withdrawal symptoms that resolved within 24 hours. She stated that the medication was not helping her pain and was just preventing withdrawal, ‘so I figured I would just get it [withdrawal] over with’. At treatment week 7, Ms. P's average pain was a 5/10, worst pain in the past 24 hours was 6/10 and current treatment was providing 40% pain relief. She also indicated less functional impairment in 7 domains of functioning including general activity, walking, work mood, enjoyment in life, relationships with others and sleep, compared to pre-treatment. Her Current Opioid Misuse Measure(2) was 7 (unlikely opioid misuse).

Figure 2. Weekly oxycodone dose, opioid withdrawal symptoms and self-report opioid misuse and pain.

Weekly dose of oxycodone, weekly patient-report of opioid misuse measured by the Current Opioid Misuse Measure, weekly patient-report of average daily pain measured by the Brief Pain Inventory, weekly opioid withdrawal measured by the Current Opioid Withdrawal Scale completed by the provider.

At week 7, Ms. P felt that the demands of childcare, full-time employment and regular obstetric and psychiatric appointments at different locations were becoming untenable. We had completed the CBT for Chronic Pain protocol, and she felt confident that she would not use prescription opioids and instead manage her pain with CBT tools. An appointment was made for three weeks later and the patient did not attend this appointment.

At 32 weeks gestation, Ms. P called and left a message with her obstetrician that her pelvic and neck pain was worsening and she wanted to restart an opioid medication. The obstetrician contacted the psychiatrist to discuss a collaborative approach to her care. The obstetrician had continued to see the patient at regular obstetric appointments and felt that the described pain was consistent with the normal progression of pregnancy and did not warrant opioid therapy, but offered a referral to physical therapy, an abdominal belt and an appointment with the psychiatrist to review CBT techniques and discuss any other non-opioid pain management options. In a phone call follow-up with the psychiatrist, Ms. P revealed several recent stressors; the father of the baby had recently relapsed to substance use which had put significant strain on their relationship and sitting at a desk for several hours each day was worsening her back and neck plan. The psychiatrist worked with the patient via phone applying problem solving and stress management techniques and reviewed applicable CBT concepts in three separate 45-60 minute phone calls.

The patient continued to attend routine obstetric appointments. She had a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery at 38 weeks gestation. The newborn was healthy and without any evidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome during its hospital stay. The patient's urine drug screen on delivery was negative for all substances including opioids and confirmatory testing for oxycodone and hydrocodone were negative. Based on the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program database, the patient last received a controlled substance from her psychiatrist at 20 weeks gestation.

Ms. P was given a prescription for oxycodone/acetaminophen 5mg/325mg Q6hours (total of 20 tablets) and ibuprofen 800mg Q6hrs upon discharge from the postpartum unit. She called the psychiatrist to discuss the use of this oxycodone/acetaminophen and pain management strategies, then. Ms. P opted to fill the prescription of ibuprofen and gave the oxycodone/acetaminophen prescription to her pharmacist to hold and not fill, unless she called and requested it. After one month, the prescription was voided and at 6 months postpartum, the patient continues to not use controlled substances for her pain.

Epidemiology of Prescription Opioid Use and Use Disorder in Pregnancy

The prevalence of prescription opioid use during pregnancy has increased significantly over the past decade with 14-22% of pregnant women filling a prescription opioid medication during pregnancy.(12,13) In the United States, the proportion of pregnant women filling prescription opioids varies by state and ranges from 9.5% to 41.6%, with southern states having the greatest number of women using opioids during pregnancy.(13,14) Similarly, there is variation based on insurance coverage ranging from 14.4% among those with private insurance to 21.6% among those with Medicaid filling a prescription for opioid medication.(12,13)

Over the past decade the overall prevalence of other substance use disorder in pregnancy has remained stable, with approximately 5% of women reporting drug use during pregnancy.(15,16) However, the proportion of pregnant women with prescription opioid use disorder has changed dramatically. In a nationwide sample of 57 million pregnant women admitted to a hospital for delivery, the prevalence of opioid use disorder doubled from 0.17% in 1998 to 0.39% in 2011.(17) Similarly, nationwide data from the Treatment Episodes Data Set(18) which tracks admissions to 83% of US substance abuse treatment facilities, demonstrated that the proportion of pregnant women with prescription opioid use disorder has increased from 2% in 1992 to 28% in 2012.

There are substantial maternal, fetal and newborn risks associated with opioid use disorder during pregnancy. In addition to risk of unintentional overdose and death as seen in the general population,(19,20) opioid use disorder during pregnancy are associated with considerable obstetric morbidity and mortality including increased risk of maternal cardiac arrest, blood transfusion, cesarean delivery and death.(17) Other obstetric complications include increased risk of intrauterine growth-restriction, oligohydramnosis, placental abruption, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, severe preeclampsia or eclampsia and stillbirth.(17) A recent systematic review evaluating potential fetal harms associated with prescription opioid use in pregnancy reveal the possibility for poor fetal growth, birth defects and preterm birth, but findings are inconsistent and methodological limitations inherent to the study of medications in pregnancy hinder our ability to draw definitive conclusions.(21) Neonatal abstinence syndrome is due to maternal use of opioids during pregnancy. Neonatal abstinence syndrome occurs in approximately 60% of newborns exposed to perinatal prescription opioids(22) and is characterized as by hyperirritability of the central nervous system and dysfunction of the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system, resulting in serious illness and death if untreated.(23) The incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome has increased 5-fold in the past decade. Currently a baby is born every 25 minutes in the US with neonatal abstinence syndrome, and the impact on newborn health and utilization of healthcare resources makes it a major public health concern.(4,22) On average, the cost of caring for a newborn with neonatal abstinence syndrome is $65,000, compared to $5,000 for a healthy newborn. Currently, Medicaid is covering 87% of the total costs of care of newborns with neonatal abstinence syndrome.(4) Unfortunately, pregnant women with prescription opioid use disorder are often not aware of the risk for and potential severity of neonatal abstinence syndrome.

Diagnosis and Treatment of an Opioid Use Disorder

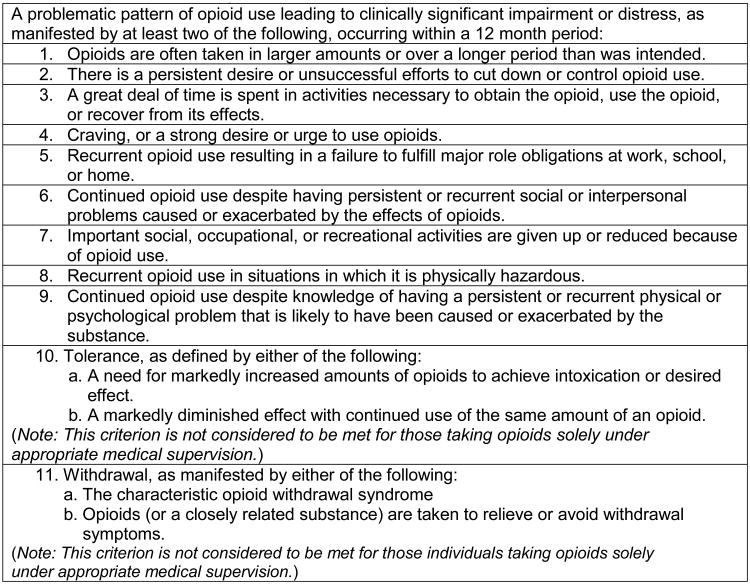

The diagnosis of an opioid use disorder during pregnancy is no different than non-pregnant populations (Figure 1). The standard of care for women with heroin use disorder in pregnancy is treatment with opioid agonist therapies such as methadone or buprenorphine, as opposed to medication-assisted withdrawal(3) and is based on data collected prior to the prescription opioid epidemic. These data include retrospective chart reviews including a total of 389 women withdrawn from methadone using different tapering strategies of varying length (3-56 days) and in different treatment settings (e.g., outpatient, intensive outpatient, inpatient).(25-29) Rates of conversion to methadone or relapse to heroin use collectively ranged from 41%-96%, with poor obstetric outcomes related to relapse to drug use.(25,29) One retrospective study comparing methadone maintenance to a 3 or 7 day methadone-assisted withdrawal(28) demonstrated that 52.2% of those completing methadone-assisted withdrawal eventually converted to methadone maintenance. Women on methadone maintenance stayed in treatment longer (110 vs. 20 days), attended more obstetrical visits (8.3 vs. 2.3) and were more likely to deliver at the program hospital.(28)

Figure 1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition Opioid Use Disorder Diagnostic Criteria.

Adapted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

These data collectively demonstrate that pregnant women with heroin use disorder are at high risk for relapse to drug use if they undergo medication-assisted withdrawal and that agonist maintenance therapies, such as methadone or buprenorphine, should be the standard of care.(3) Although there are obstetric and newborn risks associated with maintenance medications,(30) heroin relapse places women at high risk for infectious diseases, exposures to violence, legal consequences and poor obstetric outcomes. As such, experts conclude that the risks of relapse to heroin use far out weights the risks of maintenance medications.(3)

It is unclear, however if this same rationale applies to the treatment of pregnant women with prescription opioid use disorder. The few studies that have compared demographic and drug use characteristics of those with prescription opioid vs. heroin use disorder have demonstrated differences.(31,32) Compared to those with heroin use disorder, those with prescription opioid use disorder are more likely to be white, receive legal income, use private insurance, and have greater family and social supports.(31,33) For women, these characteristics have been associated with increased addiction treatment retention and completion.(34,35) Importantly, those with prescription opioid use disorder are less likely to use non-opioid illicit drugs or injection drug use,(31-33,36) compared to those with a heroin use disorder. Therefore, it is unlikely that pregnant women have the same risks associated with non-opioid illicit drug use or for blood borne infections, nor are their fetuses at risk for the dramatic cycles of high level opiate exposure and withdrawal, as seen with intravenous heroin use. High risk behaviors and legal consequences associated with heroin use are also not as common in prescription opioid use disorder. The 2013 and 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health demonstrated that 50.5% of people who misused prescription opioids got them from a friend or relative for free, and 22.1% got them from a doctor.(37,38) Recent data also suggests that prescription opioids can be successfully withdrawn during pregnancy without an increased risk for poor obstetric outcomes.(10) Further, newborn outcomes including neonatal abstinence syndrome appear to be improved among women undergoing medication-assisted withdrawal.(5,10,39-41) At present, however it remains unclear if pregnant women with a prescription opioid use disorder that undergo medication-assisted withdrawal are at high risk for relapse to prescription opioid use or other drug use.

Since the start of the prescription opioid epidemic, there have been five published studies including a total of 613 pregnant women with primarily prescription opioid use disorder who attempted medication-assisted withdrawal.(5,10,39-41) One small study comparing opioid-assisted withdrawal (N=8) to methadone (N=12) or buprenorphine (N=5) in a comprehensive outpatient treatment program found no differences in maternal obstetric outcomes or urine drug screens between groups.(5)

Two national cohort studies completed in Norway(39) and Canada(40) reviewed the maternal and newborn outcomes of opioid-dependent women participating in outpatient opioid maintenance programs, who lowered their medication dose during pregnancy. A range of 40-80% of pregnant women with opioid use disorder were able to reduce their maintenance opioid medication and approximately 2-10% were able to completely stop opioid medication during pregnancy.(39,40) At the time of delivery, 50-100% were successful at using only the reduced medication and had favorable newborn outcomes.(39,40)

In a retrospective cohort study of 95 pregnant women electing inpatient opioid detoxification, 56% (53/95) were successful with opioid cessation.(41) Those who were successful in stopping had longer inpatient detoxification admissions (median days 25 vs. 15 days) and were more likely to complete the entire detoxification program compared to women that were not successful.(41) Most recently, Bell et al. (2016)(10) reported no increased risk for poor obstetric outcomes in 301 pregnant women with opioid use disorder who stopped drug use during pregnancy, even with vastly different withdrawal protocols including abrupt cessation with symptomatic treatment (108 incarcerated women), a 5-10 day inpatient buprenorphine-assisted withdrawal protocol (100 women) and a 6-12 week outpatient buprenorphine-assisted withdrawal protocol (93 women). Groups differed in risk for relapse with the greatest risk among those with little to no outpatient care following inpatient detoxification (77%). Rates of relapse to prescription opioid use were 17.2% among women who completed an inpatient taper followed by discharge to a group home, and 17.4% among women completing an outpatient taper with intensive outpatient follow-up care.(10)

Taken together, these data demonstrate that women can reduce or discontinue their use of prescription opioid medications during pregnancy with a low risk for poor obstetric and newborn outcomes and low risk for relapse to drug use for those receiving longer and more intensive follow-up care.(10,41) Overall these data are reassuring given the limited access and suboptimal adherence to methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatments,(42) as well as the common patient preference to discontinue opioid medications during pregnancy.(28,44) However, the characteristics of optimal care for pregnant women with prescription opioid use disorder who choose medication-assisted withdrawal are largely unknown and future research in this area is greatly needed.

Conclusion

Our case highlights the clinical challenges of treating prescription opioid use disorder during pregnancy. The standard of care for the treatment for heroin use disorder is clear as the risks of relapse to heroin or IV heroin drug use far out weighs the risks of opioid maintenance medications such as methadone or buprenorphine. This rationale, however may not apply to pregnant women with prescription opioid use disorder. Increasing data suggests that the maternal and fetal risks associated with carefully monitored tapering or discontinuation of opioid medications are low and that this practice may help support patient preference and may be beneficial to the newborn. However, an integrated team approach including mental health specialists who can provide psychological and pharmacological treatments as well as continued follow-up to address pain, and ongoing stressors are critical to the continued cessation of opioids and the health of the mother and newborn. Pregnancy may represent an ideal time for this type of more intensive intervention as all pregnant women are afforded health insurance and they are often motivated toward positive health behaviors to invest in their newborns health and future.(45) Further, providing women with appropriate treatment and follow-up care could result in substantial cost savings by preventing or reducing rates and severity of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Further research is needed to determine appropriate tapering and follow-up regimens that enhance the success of medication-assisted withdrawal and reduce the risk for relapse. Further research is also needed to identify the demographic, psychiatric and psychosocial factors that increase the likelihood of unsuccessful medication-assisted withdrawal, as well as factors that protect individuals from relapse, in an effort to minimize the potential risks associated with relapse and ensure that our limited substance abuse treatment resources are allocated to those women at highest risk for relapse to drug use during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The efforts of Drs. Guille (1K23DA039318-01), Barth (1K23 DA039328-01A1) and McCauley (1K23 DA036566-01A1) are funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Brady's effort is funded by R25 DA020537, UL1 TR00006205S1, P50 DA016511, U10 DA01372, and K12 HD055885. The funding sources had no role in the preparation or writing of this review manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Drs. Guille, Barth, Mateus, McCauley and Brady report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):309–318. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, et al. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130(1-2):144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, and American Society of Addiction Medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: Opioid Abuse, Dependence, and Addiction in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1070–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256496e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000-2009. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307(18):1934–1940. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund IO, Fitzsimons H, Tuten M, Chisolm MS, O'Grady KE, Jones HJ. Comaparing methadone and buprenorphine maintenance with methadone-assisted withdrawal for the treatment of opioid dependence during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3:17–25. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S26288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared Decision Making — The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otis J. therapist guide. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2007. Managing chronic pain: A cognitive behavioral therapy approach. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otis J. Managing chronic pain: A cognitive behavioral therapy approach workbook. New York, New York: Oxford University Press Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain-United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell J, Towers CV, Hennessy MD, Heitzman C, Smith B, Chattin K. Detoxification from opiate drugs during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS) J Psychoact Drugs. 2003;35(2):253–259. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rathmell JP, Seeger JD, Doherty M, Fischer MA, et al. Patterns of opioid utilization in pregnancy in a large cohort of commercial insurance beneficiaries in the United States. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(5):1216–1224. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among medicaid-enrolled women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;0(0):1–5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein RA, Bobo WV, Martin PR, Morrow JA, Wang W, Chandrasekhar R, et al. Increasing pregnancy-related use of prescription opioid analgesics. Annals of Epidemiology. 2013;23:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2002 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. 2003 Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/, No. HHS Publication No. SMA 03-3836.

- 16.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2010 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. 2011 Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/, No. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658.

- 17.Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, Creanga AA, Leffert LR. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: Temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(6):1158–1165. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Treatment episode data set (TEDS) 1992-2010. 2013a Available at: http://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/dasis2/teds.htm.

- 19.Olsen Y. The CDC guideline on opioid prescribing: Rising to the challenge. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1577–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy M. Opioid overdose deaths rose fivefold among US women in 10 years. BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yazdy MM, Desai RJ, Brogly SB. Prescription Opioids in Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes: A Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Genet. 2015;4:56–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patrick SW, Dudley J, Martin PR, Harrell FE, Warren MD, Hartmann KE, et al. Prescription opioid epidemic and infant outcomes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):842–850. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doberczak TM, Kandall SR, Wilets I. Neonatal opiate abstinence syndrome in term and preterm infants. Journal of Pediatrics. 1991;118(6):933–937. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blinick G, Wallach RC, Jerez E. Pregnancy in narcotics addicts treated by medical withdrawal. The methadone Detoxification Program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;105(7):997–1003. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(69)90117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maas U, Kattner E, Weingart-Jesse B, Schäfer A, Obladen M. Infrequent neonatal opiate withdrawal following maternal methadone detoxification during pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 1990;18(2):111–118. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1990.18.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dashe JS, Jackson GL, Olscher DA, Zane EH, Wendel GD., Jr Opioid detoxification in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(5):854–858. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luty J, Nikolaou V, Bearn J. Is opiate detoxification unsafe in pregnancy? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(4):363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones HE, O'Grady KE, Malfi D, Tuten M. Methadone maintenance vs. methadone taper during pregnancy: Maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Addict. 2008;17(5):372–386. doi: 10.1080/10550490802266276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blinick G, Wallach RC, Jerez E, Ackerman BD. Drug addiction in pregnancy and the neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125(2):135–142. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy JJ, Leamon MH, Parr MS, Anania B. High-dose methadone maintenance in pregnancy: Maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3):606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer B, Patra J, Firestone Cruz M, Gittins J, Rehm J. Comparing heroin users and prescription opioid users in a Canadian multi-site population of illicit opioid users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(6):625–632. doi: 10.1080/09595230801956124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenblum A, Parrino M, Schnoll SH, Fong C, Maxwell C, Cleland CM, et al. Prescription opioid abuse among enrollees into methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigmon SC. Characterizing the emerging population of prescription opioid abusers. Am J Addict. 2006;15(3):208–212. doi: 10.1080/10550490600625624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Predictors of substance abuse treatment retention among women and men in an HMO. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(10):1525–1533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green CA, Polen MR, Dickinson DM, Lynch FL, Bennett MD. Gender differences in predictors of initiation, retention, and completion in an HMO-based substance abuse treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23(4):285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brands B, Blake J, Sproule B, Gourlay D, Busto U. Prescription opioid abuse in patients presenting for methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73(2):199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. 2014 NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863.; Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [PubMed]

- 38.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015 Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/, HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH.

- 39.Welle-Strand GK, Skurtveit S, Tanum L, Waal H, Bakstad B, Bjarkø L, et al. Tapering from Methadone or Buprenorphine during Pregnancy: Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes in Norway 1996-2009. Eur Addict Res. 2015;21(5):253–261. doi: 10.1159/000381670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dooley R, Dooley J, Antone I, Guilfoyle J, Gerber-Finn L, Kakekagumick K, et al. Narcotic tapering in pregnancy using long-acting morphine: An 18-month prospective cohort study in northwestern Ontario. Can Fam Phys. 2015;61(2):e88–e95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart RD, Nelson DB, Adhikari EH, McIntire DD, Roberts SW, Dashe JS, et al. The obstetrical and neonatal impact of maternal opioid detoxification in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(3):267.e1–267.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schottenfeld RS, O'Malley SS. Meeting the growing need for heroin addiction treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(5):437–438. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin CE, Longinaker N, Terplan M. Recent trends in treatment admissions for prescription opioid abuse during pregnancy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin J, Thomas Payte J, Zweben JE. Methadone maintenance treatment: A primer for physicians. J Psychoact Drugs. 1991;23(2):165–176. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1991.10472234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wisner KL, Sit DKY, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):490–498. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]