Abstract

In this issue of Cancer Cell, Sheltzer et al. shed new light on Theodor Boveri's century-old hypothesis by demonstrating that aneuploidy characterized by single-chromosome gains acts to suppress tumorigenesis and that aneuploidy itself is a nidus for genomic instability.

Over 100 years ago, Theodor Boveri hypothesized that cells harboring numerical karyotype abnormalities, a condition known as aneuploidy, were the foundational driving force governing tumorigenesis (Boveri, 2008). Indeed, aneuploidy is a ubiquitous feature of nearly all cancers. However, whether aneuploidy is a cause or consequence of transformation has been difficult to define experimentally and has remained a hot topic of discussion in cancer biology (Naylor and van Deursen, 2016). On one hand, several mouse models of aneuploidy have been shown to be tumor prone (Ricke et al., 2008). On the other hand, aneuploidy has been shown to elicit several intrinsic tumor-suppressive mechanisms (Gordon et al., 2012; Santaguida and Amon, 2015). The complexity of the aneuploidy-cancer relationship was perhaps best illustrated by aneuploidy-prone CENP-E mutant mice, which are both protected from and susceptible to cancer depending on the tissue context (Weaver et al., 2007).

In 2009, Boveri's hypothesis was finally supported with mechanistic experimental evidence (Baker et al., 2009). Using a mouse model of whole-chromosome instability (W-CIN)—that is, each cell division within the organism had the propensity of generating daughter cells with random karyotypic abnormalities—it was demonstrated that aneuploidy can promote tumorigenesis through loss of tumor suppressor heterozygosity. This principle is akin to acquiring a mutator phenotype since W-CIN promotes aneuploidy and facilitates the loss of chromosomes carrying wild-type tumor suppressors. Accordingly, the result of chromosomal instability in this context is an aneuploid daughter cell with one less chromosome than normal and therefore only one copy of a critical tumor suppressor gene, like p53, that happens to be mutated.

Around this same time, Angelika Amon's group published a groundbreaking study showing that primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with additional chromosomes proliferated slower and were more resistant to immortalization than their euploid counterparts (Williams et al., 2008). This study was subsequently supplemented by work from other groups showing that aneuploidy elicits several potent tumor-suppressive stress responses, including senescence, cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and mitotic catastrophe.

Thus, given the seemingly contradictory evidence for and against aneuploidy as a tumor promoter, Boveri's long-standing hypothesis continues to remain an important unanswered question for the field of cancer biology.

In this issue of Cancer Cell, the Amon group is back with what is sure to be another milestone in the persistent quest to critically test Boveri's famous hypothesis (Sheltzer et al., 2017). The major significance of this study is 2-fold: it demonstrates that aneuploidy characterized by single-chromosome gains suppresses tumorigenesis in vivo and is a source of genomic instability in diploid organisms.

To do this, the authors, led by Jason Sheltzer, generated trisomic MEF lines for chromosomes 1, 13, 16, and 19 using an innovative breeding strategy that takes advantage of naturally occurring Robertsonian translocations and random nondisjunction in the germline of male mice. They then assessed the ability for trisomy to induce spontaneous immortalization. Interestingly, not only did trisomic MEFs fail to display any cancer-related phenotypes in vitro, they also were prone to cellular senescence with rates of irreversible cell-cycle arrest directly correlating with the size of the trisomic chromosome (Figure 1). That is, MEFs trisomic for chromosome 1, the largest mouse chromosome, senesced at earlier passages and to a higher degree than MEFs trisomic for chromosome 19, the smallest mouse chromosome. Importantly, even in the context of oncogenic signaling that strongly promotes uncontrolled cell proliferation, single-chromosome gains decreased population doubling. Again, the degree to which trisomy of chromosomes 1, 13, 16, and 19 were able to inhibit proliferation was directly proportional to the size of the trisomic chromosome.

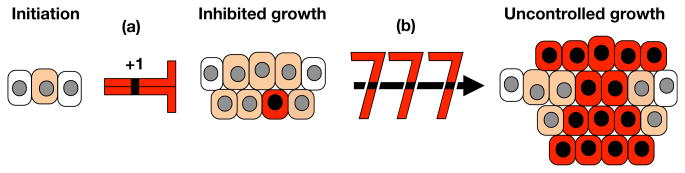

Figure 1. Single Chromosome Gains Slow Neoplastic Growth But Set the Stage for Malignancy.

Aneuploidy, an abnormal number of chromosomes, is a hallmark of human cancers and associated with poor clinical outcome. Sheltzer et al. show that single-chromosome gains (+1) are persistent inhibitors of neoplastic growth (a) even in the presence of strong drivers of uncontrolled growth. Chromosome gains are found to be a source of chromosomal instability, allowing rare cells after a long lag phase to fortuitously hit a jackpot (b) of “chromosome rearrangements” that unleashes uninhibited tumor cell growth resulting in malignancy.

Next, in the key experiment, the authors transduced their trisomic MEFs with two cooperating oncogenes to abolish the proliferation differences between the trisomic and euploid cell lines and tested their ability to form tumors in xenograft assays. Despite the fact that the transduced trisomic and euploid cell lines proliferated at similar rates in culture, the trisomic lines formed much smaller tumors in vivo, thereby providing strong evidence that aneuploidy characterized by chromosome gains acts as a potent suppressor of tumorigenesis (Figure 1). Complementary experiments in which extra chromosomes were injected into chromosomally stable human colorectal cancer confirmed that chromosome gains are robust inhibitors of tumor growth.

Finally, the authors set out to discover how cells adapt to the trisomic state during transformation and tumorigenesis. These efforts revealed that trisomy, despite being tumor suppressive, drove cells to acquire additional structural and/ or numerical chromosome abnormalities to compensate for the initial growth impairment, which, over time, promoted a state of increased tumorigenicity and improved fitness (Figure 1).

Testing Boveri's hypothesis has proven to be more challenging and rewarding than anyone could have foreseen. Our current best evidence still leaves us without a clear-cut answer as to the role of aneuploidy in tumorigenesis. It appears that the answer to this question may depend not only on the nature of the aneuploidy— whether a chromosome is lost or gained—but also on the complex genomic compensation that follows. In the end, we are still left with the tremendous challenge to translate these fundamental discoveries into practical solutions for patients with cancer. The study from Sheltzer et al. highlights the urgent need to elucidate the compensatory mechanisms that are activated within the aneuploid cell. How do aneuploid cells induce senescence and apoptosis? Are these pathways mutated in cancer cells? How can we pharmacologically induce senesce and/or apoptosis in cancer cells based on their abnormal karyotype? How do aneuploid cells evade senescence and apoptosis? How can we inhibit these pathways therapeutically? By what mechanism(s) do aneuploid cells continue to rearrange their genome? Can this be prevented or even enhanced to kill cancer cells? Are the ongoing genomic rearrangements random, or are there patterns? Addressing this next generation of questions will undoubtedly require the same level of persistence as testing Boveri's original hypothesis. However, these efforts hold the promise of tremendous impact on cancer treatment given that aneuploidy and chromosome number instability are among the most universal hallmarks of cancer.

Acknowledgments

J.M.v.D. is supported by NIH grants R01CA96985 and R01CA126828 and by the Paul F. Glenn Foundation. R.M.N. is supported by an individual fellowship from the NIH (F30 CA189339) and by the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

References

- Baker DJ, Jin F, Jeganathan KB, van Deursen JM. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveri T. J Cell Sci. 2008;1(21)(Suppl 1):1–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DJ, Resio B, Pellman D. Nat. Rev Genet. 2012;13:189–203. doi: 10.1038/nrg3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor RM, van Deursen JM. Annu. Rev Genet. 2016;50:45–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricke RM, van Ree JH, van Deursen JM. Trends Genet. 2008;2(4):457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaguida S, Amon A. Nat. Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:473–485. doi: 10.1038/nrm4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheltzer JM, Ko JH, Replogle JM, Habibe Burgos NC, Chung ES, Meehl CM, Sayles NM, Passerini V, Storchova Z, Amon A. Cancer Cell. 2017;31 doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.12.004. S1535-6108(16)30599-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BA, Silk AD, Montagna C, Verdier-Pinard P, Cleveland DW. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BR, Prabhu VR, Hunter KE, Glazier CM, Whittaker CA, Housman DE, Amon A. Science. 2008;322:703–709. doi: 10.1126/science.1160058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]