The switch from self-renewal to differentiation coincides with a shorter S phase in which replication forks are faster.

Keywords: cell cycle, CDK inhibitors, replication, differentiation, cell fate decision, self renewal, erythropoiesis, hematopoiesis

Abstract

Cell cycle regulators are increasingly implicated in cell fate decisions, such as the acquisition or loss of pluripotency and self-renewal potential. The cell cycle mechanisms that regulate these cell fate decisions are largely unknown. We studied an S phase–dependent cell fate switch, in which murine early erythroid progenitors transition in vivo from a self-renewal state into a phase of active erythroid gene transcription and concurrent maturational cell divisions. We found that progenitors are dependent on p57KIP2-mediated slowing of replication forks for self-renewal, a novel function for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. The switch to differentiation entails rapid down-regulation of p57KIP2 with a consequent global increase in replication fork speed and an abruptly shorter S phase. Our work suggests that cell cycles with specialized global DNA replication dynamics are integral to the maintenance of specific cell states and to cell fate decisions.

INTRODUCTION

The timing and execution of developmental cell fate decisions are incompletely understood. The cell cycle is implicated in such decisions through interactions between cell cycle and transcriptional regulators (1–3) and through cell cycle phase–specific receptiveness to differentiation cues (4–7). Reconfiguration of lineage-specific chromatin loci, a prerequisite for the execution of cell fate decisions, was hypothesized to require S phase, because the passage of the replication fork transiently disrupts nucleosomes (8, 9). However, developmental transitions and associated dynamic changes in chromatin are possible in the absence of S phase (10–15). Notwithstanding these findings, S phase is essential for activation or silencing of some genes in yeast (16, 17) and for a subset of cell fate decisions in metazoa (18–22), although the precise role and underlying mechanisms linking S phase to these decisions remain unclear.

We recently identified an S phase–dependent cell fate decision that controls the transition from self-renewal to differentiation in the murine erythroid lineage (23). Erythroid progenitors at the colony-forming unit erythroid (CFUe) stage (24) undergo a number of self-renewal cell divisions before switching into a phase of active erythroid gene transcription, known as erythroid terminal differentiation (ETD), during which they mature into red cells while undergoing three to five additional cell divisions. The switch from self-renewal to ETD is tightly regulated because it determines the number of CFUe progenitors and erythroid output (24, 25). Many of the transcription factors that drive the ETD, including GATA-1, Tal-1, and Klf1, are well characterized (26, 27). However, the cellular context and signals that determine their timing of activation are not well understood.

To address these questions, we studied the murine fetal liver, an erythropoietic tissue rich in erythroid progenitors. Our recent work using this model system showed that the transition from the self-renewing CFUe to ETD in vivo coincides with the up-regulation of the cell surface marker CD71, making it accessible to molecular study (23). We found that ETD is activated during early S phase, in a rapid cell fate switch that comprises a number of simultaneous commitment events, including the onset of dependence on the hormone erythropoietin (Epo) for survival, chromatin reconfiguration (23), and an unusual process of global DNA demethylation (28). These commitment events are dependent on S-phase progression, because their induction can be reversibly prevented by reversibly arresting DNA replication (23).

Here, we explore the requirement for S-phase progression during this cell fate switch, by asking whether S phase at the time of the switch might differ from S phase in preceding cycles. We previously noted that the switch to ETD coincides with an increase in intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, possibly indicating a shorter S phase (23, 28). Although the length of the G1 phase is well documented as a regulatory target of growth factors and differentiation signals (4, 7), much less is known regarding the regulation of S-phase length in mammals. By contrast, the well-studied postfertilization cleavage cycles of model organisms, such as frog and Drosophila, last only minutes and comprise an extremely short S phase; S phase lengthens abruptly at the midblastula transition (29–32). This marked change in S-phase length is the result of altered firing efficiency of origins of replication, which transition from synchronous and efficient firing during the short cleavage cycles to asynchronous and less efficient firing at the midblastula transition (30, 33). Although far less is known regarding the possible regulation of S-phase length during mammalian development, older reports have noted transient S-phase shortening during key cell fate decisions, including shortening of S phase to <3 hours in epiblasts of mouse and rat embryos as they transition through the primitive streak and become either endoderm or mesoderm (34–36). The relevance of altered S-phase duration to mammalian differentiation and the underlying mechanisms are not known.

In this work, we determine that the transition from CFUe to ETD entails a transient shortening of S phase, in part regulated by p57KIP2, a member of the Cip/Kip family of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors (CDKIs) (37–40). In a novel function for this protein, we find that p57KIP2 prolongs the duration of S phase in self-renewing progenitors, a function essential for their viability both in vivo and in vitro. The mechanism controlling S-phase duration does not involve altered firing of replication origins but, instead, altered speed of replication forks. In the presence of p57KIP2, replication forks are slower; p57KIP2 down-regulation with activation of the ETD results in globally faster forks.

RESULTS

Activation of ETD coincides with S-phase shortening

To study the activation of ETD in vivo, we divided erythroid lineage cells in the fetal liver into six sequential developmental subsets, subsets 0 to 5 (S0 to S5), based on the expression of cell surface markers CD71 and Ter119 (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A) (23, 41, 42). Subsets S0 and S1 contain progenitors with CFUe colony-forming potential (giving rise to colonies of 16 to 32 red cells within 72 hours), whereas subsets S2 to S5 contain maturing erythroblasts undergoing ETD, marked by the expression of the erythroid cell surface marker Ter119 (23). We have previously shown that the switch to ETD in CFUe progenitors involves a series of events that are synchronized with the cell cycle and that can be followed in an orderly manner by observing changes in CD71 and Ter119 expression (23). Thus, CFUe progenitors undergo a limited number of self-renewal divisions while in the S0 subset, including the last cell division of the CFUe progenitor stage. The progenies of this last cell division (Fig. 1A, colored purple) undergo a sharp increase in cell surface CD71 when in early S phase of the cycle, transitioning into the S1 subset. This transition, which depends on S-phase progression, marks the switch to ETD and the onset of Epo dependence. The ensuing induction of erythroid genes, including expression of the cell surface marker Ter119 and transition into the S2 subset, takes place around the time that these cells undergo the next mitosis. Therefore, the S1 subset contains largely S-phase cells during a rapid transition from CFUe to ETD (Fig. 1A) (23).

Fig. 1. S-phase shortening at the transition from self-renewal to differentiation in vivo.

(A) Schematic depicting sequential flow cytometric fetal liver subsets S0 to S5 during erythroid differentiation (see flow cytometric profile in fig. S1A). Seventy percent of S0 and all of S1 cells have CFUe potential. The transition from S0 to S1 marks a switch from CFUe self-renewal to differentiation. The S0/S1 switch is S phase–dependent and takes place in the early S phase of the last CFUe generation (23). (B) Double-deoxynucleoside label approach. Pregnant female mice were injected with EdU at t = 0 and with BrdU following a time interval I. Fetal livers were harvested and analyzed shortly after the BrdU pulse. Cells in S phase of the cycle at the time of the EdU pulse incorporate EdU into their DNA and retain this label as they progress through the cycle (represented as green cells). Cells entering S phase continue to take up EdU during the interval I, until EdU is cleared from the blood (shown as dashed green circles). Similarly, cells that are in S phase during the BrdU pulse become labeled with BrdU (red). The “green only” cells (EdU+BrdU−) represent cells that were in S phase during the first EdU pulse but have exited S phase during the interval I. This cell fraction f is proportional to the length of the interval I, as long as I is shorter than the gap phase (G2 + M + G1). By trial and error, we found that, for I to be shorter than the gap phase of S1 cells, it needs to be ≤2 hours. The linear relationship between I and f can be expressed in terms of the cell cycle length I/Tc = f, where f is the cells that exited S phase in interval I [measured as % (EdU+BrdU−) cells], I is the interval between EdU and BrdU pulses, and Tc is the cell cycle length. This relationship gives the length of the cycle as Tc = I/f. The length of S phase, Ts, can then be calculated from fraction s, of all cycling cells that take up the BrdU label (%BrdU+), as Ts = s × Tc. In preliminary experiments, we used longer BrdU pulses. These showed that nearly all cells were labeled with BrdU, suggesting that essentially all cells are cycling. Therefore, we made no corrections for the fraction of cycling cells. (C) Representative experiment as described in (B). Pregnant female mice were pulsed with EdU, followed by a BrdU pulse after an interval of 2 hours. Upper two panels show fetal liver cells from mice that were pulsed only with EdU, or only with BrdU, but processed for labeling for both deoxynucleosides in the same way as the double-labeled mice. Lower panels show EdU and BrdU labeling in fetal liver subsets that were explanted after the second pulse, sorted by flow cytometry, and then each processed for EdU and BrdU incorporation. In this specific experiment, a third of all S1 and S2 cells exited S phase in a 2-hour interval, giving a cell cycle length of 2/0.33 = 6 hours; only 14% of S0 exited S phase in the same time interval, giving a cell cycle length of 2/0.14 = 14.3 hours. Because 64% of S1 and 44% of S0 cells are BrdU+, their S-phase lengths are 0.64 × 6 = 3.84 hours and 0.44 × 14.3 = 6.3 hours, respectively. (D) Summary of five independent experiments as described above. The linear relationship between I and the cells that exited S phase, f, allows calculation of a mean cycle and length. S1, empty symbols; S0, filled symbols. r2 = 0.95 for S1 and 0.85 for S0. Results in table are mean ± SE. Pulses were reversed (BrdU first, EdU second) in one experiment, without effect on results (included here). The y axis intercepts are not at 0 because it takes approximately 20 min for peak absorption of each deoxynucleoside (fetal livers are explanted 20 min after the second injection). (E) Durations of cell cycle and cell cycle phases. The length of each cell cycle phase was calculated by multiplying the fraction of cells in each cell cycle phase following the second pulse by the total cell cycle length [measured as in (D)].

To analyze the cell cycle characteristics of CFUe progenitors during this transition, we injected pregnant female mice with the nucleoside analog bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and harvested embryos 30 min after injection. The cartoon in fig. S1B illustrates two distinct parameters of replication that may be obtained from this experiment. First, the number of cells in S phase is measured on the basis of their incorporation of BrdU into replicating DNA (BrdU+ cells). Second, the rate of BrdU incorporation into S-phase cells, measured as the BrdU median fluorescence intensity within the S-phase gate (fig. S1B, dashed black line), indicates the intra–S-phase rate of DNA synthesis (43, 44). We found that, in spite of being exposed to the same BrdU pulse in vivo, S-phase cells within a single fetal liver vary substantially in their BrdU incorporation rate, depending on their stage of differentiation. Specifically, in the shown example in fig. S1C, BrdU median fluorescence intensity (MFI) is 54% higher in S1 compared with S0 of the same fetal liver (fig. S1, C and D). This result is consistent with our earlier data in subsets sorted from pooled fetal livers, which showed that the average BrdU incorporation rate in S1 cells is 55 ± 13% higher than in S0 [mean ± SEM of six independent experiments, P = 0.02 (23, 28)]. This result indicates a substantially faster DNA synthesis rate in S-phase cells in the S1 subset, compared with S0 cells, and suggests that genome replication in S1 cells might be completed sooner, resulting in a shorter S phase (fig. S1B).

Here, we examined this possibility by using a double-nucleoside label approach (45, 46). We injected pregnant female mice sequentially with two distinct deoxynucleoside analogs of thymidine: first with a pulse of 5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU), followed, after an interval “I,” by a BrdU pulse (Fig. 1, B to E). We explanted fetal livers immediately (20 min) following the second BrdU pulse, isolated S0 and S1 cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and analyzed cells for incorporation of EdU, BrdU, or both. To calculate S phase and the cell cycle length, we measured two parameters. First, we measured the EdU+BrdU− cell fraction, which represents cells that were in S phase during the first EdU pulse but have exited S phase during the ensuing interval I. This cell fraction is therefore proportional to the duration of I (Fig. 1B). Second, we measured the fraction of cells that are BrdU+ (including both BrdU+EdU+ and BrdU+EdU− cells), which corresponds to the fraction of cells in S phase just before embryo harvest. (Note that, because of the finite but unknown clearance time for the first EdU pulse in vivo, cells entering S phase during the interval I continue to incorporate EdU, denoted by a hashed green line in Fig. 1B. It is therefore not possible to use the fraction of EdU+ cells as a measure of the fraction of cells in S phase.) Five independent experiments, with I either 1 or 2 hours, and including one experiment in which the EdU and BrdU labels were reversed, resulted in the expected linear relationship between I and the fraction of cells that exited S phase (r2 = 0.95 and 0.85 for S1 and S0, respectively; Fig. 1D). We calculated the length of the cell cycle as 15 ± 0.3 hours (mean ± SE) and 5.8 ± 0.1 hours for S0 and S1 cells, respectively, suggesting a marked cell cycle shortening at the S0/S1 transition. S-phase shortening contributed to the shortening of the cycle, decreasing by >40% [from 7.1 ± 0.3 hours in S0 to 4.1 ± 0.2 hours in S1 cells (mean ± SEM)], which corresponds to a 73 ± 15% increase in intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate. This shortening agrees with the increased BrdU incorporation rate at the transition from S0 to S1 (fig. S1, C and D) (23), validating the latter approach as a measure of intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in our system. In addition to S-phase shortening, G1 and G2-M phases also become substantially shorter with the switch from S0 to S1 (Fig. 1E).

Our results are consistent with early reports documenting a doubling time of 6 hours for murine CFUe in vivo (24) and an extremely short S phase of 2.5 hours for rat erythroblasts (45). Here, we go beyond these findings, clearly linking cell cycle and S-phase shortening with a cell fate switch, from self-renewal in S0 to ETD in S1.

p57KIP2 is expressed in S phase, slowing intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate

To investigate the mechanism of S-phase shortening in S1 cells, we compared the expression of cell cycle regulators in S0 and S1. We previously found that p57KIP2 is expressed in S0 and is rapidly down-regulated with the transition to S1 (23). By contrast, other members of the Cip/Kip family, p21CIP1 and p27KIP1, are not significantly expressed in S0 and S1 and are instead induced later, at the very end of ETD (23). p57KIP2 was previously documented to act in the G1 phase, where it inhibits the transition from G1 to S phase (37, 38). Here, we examined the cell cycle phase in which p57KIP2 is expressed, by sorting freshly explanted S0 and S1 cells enriched for either G1 or S phase, based on their DNA content (Fig. 2A). We found that the highest levels of p57KIP2 mRNA and protein were attained in S phase of S0 cells (Fig. 2, B and C). There was a significant, 50-fold decline in p57KIP2 mRNA in S-phase cells between S0 and S1 (P = 0.0079, Mann-Whitney test), whereas there was no significant difference in p57KIP2 mRNA levels between S0 and S1 cells in G1 phase of the cycle, where it was expressed at lower levels.

Fig. 2. p57KIP2 regulates intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate.

(A) DNA content histograms of freshly explanted and sorted fetal liver cells enriched for either G1 or S phase, from either the S0 or S1 subsets. DNA content histograms of the sorted subsets are overlaid on the DNA content histograms of the parental S0 or S1 populations. DNA content was visualized with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342. Representative of five independent sorts. (B) p57KIP2 mRNA expression is highest in S phase of S0 cells. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed in samples sorted as in (A). Data are means ± SEM for five independent sorting experiments. Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney test. (C) Western blotting on fetal liver samples sorted as in (A). Representative of two experiments, each with 30 fetal livers. (D) Intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate following retroviral transduction of S0 cells with shRNA targeting p57KIP2 or with a nonsilencing control shRNA (NS). Cells were pulsed with BrdU for 30 min, 20 hours after transduction. (E) Summary of four independent p57KIP2 knockdown experiments as in (D). Intra–S-phase DNA synthesis is expressed relative to controls transduced with nonsilencing shRNA. Samples were pulsed with BrdU for 30 min, 20 to 60 hours after transduction. Statistical significance was assessed with a paired t test. (F) p57KIP2 exerts dose-dependent inhibition of DNA synthesis within S-phase cells. S0 cells were transduced with p57KIP2–internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)–hCD4 (ICD4) or with “empty” vector (MICD4). Eighteen hours after transduction, cells were pulsed with BrdU for 30 min. Transduced cells were divided into gates 1, 2, and 3 (top left panel), expressing increasing levels of hCD4. Corresponding cell cycle analyses for each gate are shown (top right panels), including BrdU MFI for the S-phase gates in italics. See also fig. S2. Lower panels: Similar analysis relating MICD4, p57-ICD4, or p57T329A-ICD4 expression (hCD4-MFI) with either the number of cells in S phase (lower left panel) or BrdU MFI (lower right panel). Representative of six independent experiments.

These findings suggested a possible S-phase function for p57KIP2. To test this, we used short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to target p57KIP2 in S0 cells that were explanted and cultured in the presence of Epo and dexamethasone (Dex), conditions that promote CFUe self-renewal (47). In addition to the expected increase in the number of S-phase cells, knockdown of p57KIP2 resulted in the doubling of intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate (which increased by 2 ± 0.29–fold, mean ± SD, P = 0.005) relative to cells transduced with nonsilencing shRNA (Fig. 2, D and E).

We also examined the effect on S phase of p57KIP2 overexpression in S0 cells. We previously found that this led to cell cycle and differentiation arrest at the S0/S1 transition (23). Here, we subdivided transduced S0 cells digitally into gates based on their expression level of p57KIP2, as indicated by an hCD4 reporter linked through an IRES to p57KIP2 (Fig. 2F) (23). We found that p57KIP2 exerted dose-dependent slowing of intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate (Fig. 2F and fig. S2). As expected, in addition, p57KIP2 inhibited the transition from G1 to S in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2F). A degradation-resistant mutant of p57KIP2, p57 T329A, was more potent in its ability to slow down intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, whereas its ability to inhibit the G1- to S-phase transition was comparable to wild-type p57KIP2 (Fig. 2F). Together, both our knockdown and overexpression experiments suggest that p57KIP2 is a candidate inhibitor of intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, capable of prolonging S-phase duration in S0 cells.

p57KIP2-deficient embryos are anemic as a result of abnormal erythropoiesis

To test whether p57KIP2 regulates S-phase duration in erythroid progenitors, we examined embryos deleted for the cdkn1c gene, which encodes p57KIP2 (48, 49). p57KIP2 deficiency was previously found to result in perinatal death, associated with a variety of developmental abnormalities, including abnormal abdominal muscles, intestines, kidney, adrenals, and bones (48, 49). However, erythropoiesis in p57KIP2-deficient mice was not examined. p57KIP2 is a paternally imprinted gene. We examined p57KIP2−/− and p57KIP2+/−m (heterozygous embryos that inherited the maternal null allele) at midgestation. We found that, whereas a proportion of the p57KIP2-deficient embryos were morphologically abnormal, the majority had preserved gross normal morphology, enabling us to easily identify and explant the fetal liver (Fig. 3A). p57KIP2-deficient embryos appeared paler than wild-type littermates (Fig. 3A) and were anemic (hematocrit: 19.5 ± 1.1 for wild-type embryos versus 14.0 ± 1.0 and 13.0 ± 1.6 for p57KIP2−/− and p57KIP2+/−m embryos, respectively, mean ± SE) (Fig. 3B). Anemia in the p57KIP2-deficient embryos was likely the result of abnormal erythropoiesis because these embryos had smaller fetal livers containing significantly fewer cells (Fig. 3C). Flow cytometric profiles of the fetal liver suggested abnormal erythroid differentiation (Fig. 3, D and F). Thus, the ratio of S3 to S0 cells in p57KIP2-deficient fetal livers was significantly reduced (Fig. 3, D and F). Notably, the absolute number of S0 cells per fetal liver was unchanged compared with wild-type littermate embryos because the frequency of S0 cells within the fetal liver of p57KIP2-deficient embryos was increased in proportion to the decrease in the total number of fetal liver cells (Fig. 3, C and E). The reduced S3 to S0 ratio therefore indicates a failure of S0 cells to differentiate efficiently into S3 erythroblasts. This failure is explained by increased cell death: There was a significant negative correlation between the frequency of S3 cells in the p57KIP2-deficient fetal livers and apoptosis of either S0 (r = −0.77, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3G) or S1 cells (r = −0.86, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3G). In contrast, there was no significant correlation between the number of apoptotic S0 or S1 cells and S3 frequency in wild-type littermate embryos (Fig. 3G). Together, these results show that p57KIP2 deficiency causes anemia, secondary to cell death at the S0 and S1 progenitor stage, resulting in reduced number of maturing S3 erythroblasts.

Fig. 3. Anemia and abnormal erythropoiesis in p57KIP2-deficient embryos.

(A) p57KIP2+/−m and wild-type littermate embryos on embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5). The p57KIP2+/−m embryo is pale and has a smaller fetal liver. (B) p57KIP2-deficient embryos are anemic, as seen from their significantly reduced hematocrit (n = 64 embryos, E13.5). (C) Fewer fetal liver cells in p57KIP2-deficient embryos compared with wild-type littermates (n = 121 embryos). (D) Abnormal erythroid differentiation in p57KIP2-deficient embryos. A representative CD71/Ter119 plot showing fewer S3 erythroblasts in the p57KIP2−/− embryo compared with wild-type littermate. (E) Increased frequency of S0 cells in p57KIP2-deficient fetal livers, measured as in (D), from 7.9 ± 0.46% (mean ± SE, wild-type embryos, n = 36) to 10.6 ± 1% (p57KIP2−/−, n = 14) and 10.0 ± 0.38% (p57KIP2−/−m, n = 25). The absolute number of S0 cells is unchanged because the total number of fetal liver cells is reduced proportionally to 67% of wild-type for both p57KIP2−/−m and p57KIP2−/− embryos [see (C)]. (F) Reduced ratio of S3 to S0 erythroblast number, measured as in (D), for a total of 74 embryos. (G) Inverse correlation between apoptosis in the S0 or S1 subsets and S3 frequency in the fetal livers of p57KIP2-deficient embryos. No significant correlation was seen in the fetal livers of wild-type littermates. Fetal livers were freshly explanted and immediately stained for annexin V binding. n = 75 embryos.

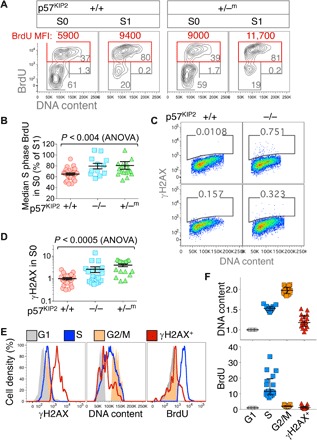

Premature S-phase shortening and DNA damage are found in p57KIP2-deficient S0 progenitors

We examined the cell cycle status in p57KIP2-deficient fetal livers, by subjecting pregnant female mice at midgestation to a 30-min pulse of BrdU. Fetal livers were then explanted and individually analyzed for intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate (Fig. 4, A and B). In wild-type embryos, intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in S0 cells was 65 ± 0.02% of the peak intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in S1 cells of the same fetal liver (mean ± SE, n = 29) (Fig. 4, A and B), in agreement with our observation of S-phase shortening at the S0/S1 transition (fig. S1, C and D, and Fig. 1, B to E). By contrast, intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate of littermate p57KIP2-deficient S0 cells was significantly faster, reaching 80 ± 0.05% (p57KIP2−/−, n = 12) and 80 ± 0.07% (p57KIP2+/−m, n = 18) of the peak intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate of the corresponding S1 cells in each fetal liver (P < 0.004; Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 4. Prematurely short S-phase and replication-associated DNA damage in p57KIP2-deficient fetal liver.

(A) Premature increase in intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, measured as BrdU MFI, in p57KIP2-deficient embryos. Representative cell cycle analysis of p57KIP2+/−m and wild-type littermate embryos. Embryos were pulsed in vivo with BrdU for 30 min before fetal livers were explanted. (B) Premature increase in intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in p57KIP2-deficient embryos. Data summary, analyzed as in (A); n = 29 (+/+), 12 (−/−), and 18 (+/−m). For each embryo, S-phase BrdU MFI in S0 is expressed as a percentage of S-phase BrdU MFI in S1 of the same fetal liver. (C) Increased γH2AX in S0 cells of p57KIP2-deficient embryos. Representative examples of freshly explanted fetal livers of p57KIP2-deficient embryos and wild-type littermates, labeled with an antibody against γH2AX. DNA content was measured using 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD). See also fig. S3. (D) Increased γH2AX in S0 cells of p57KIP2-deficient embryos. Summary of data obtained as in (C) for a total of n = 79 embryos. γH2AX measured in arbitrary fluorescence units. (E) Distribution of γH2AX labeling, DNA content, and BrdU incorporation in G1, S, or G2-M phases of the cell cycle and in γH2AX-positive cells, all in the S0 subset of a single p57KIP2−/− fetal liver. Embryos were pulsed in vivo with BrdU for 30 min, and fetal livers were harvested, fixed, and labeled for BrdU incorporation, DNA, and γH2AX. S0 cells were subdivided digitally into cell cycle phase gates based on their DNA content and BrdU incorporation. Cells positive for γH2AX were gated based only on γH2AX signal regardless of cell cycle phase. (F) p57KIP2-deficient γH2AX-positive S0 cells are slowed or arrested in S phase. Data summary for 17 p57KIP2−/+m fetal livers, analyzed as in (E). Each data point is BrdU MFI (bottom) or median DNA content (top) for all cells in a specific category (G1, S, G2-M, or γH2AX-positive) in a single fetal liver. BrdU MFI and median DNA content were normalized to their respective values in G1 cells of the S0 subset in each fetal liver.

The prematurely fast intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in p57KIP2-deficient S0 cells may have contributed to their increased apoptosis (Fig. 3G). We found a significant increase in the number of γH2AX-positive S0 cells in freshly explanted p57KIP2-deficient fetal livers (Fig. 4, C and D). DNA content analysis of γH2AX-positive S0 cells in p57KIP2-deficient fetal livers shows that they are distributed in S phase of the cycle, although fewer γH2AX-positive cells reach late S phase (Fig. 4, C, E, and F). Thus, the DNA contents of S- and G2-M–phase cells in the S0 subset of each fetal liver were 153 ± 1.2% and 198 ± 2.2% of the DNA content in G1, respectively (mean ± SEM for 17 p57KIP2+/−m embryos); the DNA content of γH2AX-positive cells in the same fetal livers was 121 ± 3.6% of the G1 content (Fig. 4, E and F). These findings suggest that γH2AX-associated DNA damage occurred in S phase of the cycle, and raise the possibility that it was a consequence of the prematurely fast intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in these cells. We found that S-phase cells that were also positive for γH2AX incorporated little or no BrdU, consistent with S-phase slowing or arrest secondary to DNA damage and replicative stress (Fig. 4, E and F).

The elevated number of γH2AX-positive cells in p57KIP2-deficient embryos persisted for the remainder of erythroblast differentiation (fig. S3, A and B). Notably, wild-type S1 cells showed relatively low levels of γH2AX staining, suggesting that they are adapted in some way to high rates of DNA synthesis (fig. S3B).

In summary, our analysis of p57KIP2-deficient embryos in vivo uncovers a novel intra–S-phase function for p57KIP2 as a suppressor of global DNA synthesis rate. p57KIP2 exerts this function in early erythroid CFUe progenitors in the S0 subset, increasing S-phase duration and enhancing cell viability, at least in part by reducing replicative stress. The premature shortening of S phase in p57KIP2-deficient S0 cells suggests that loss of p57KIP2 is sufficient to induce S-phase shortening. p57KIP2 down-regulation is therefore a likely mechanism underlying S-phase shortening during the S0/S1 cell fate switch.

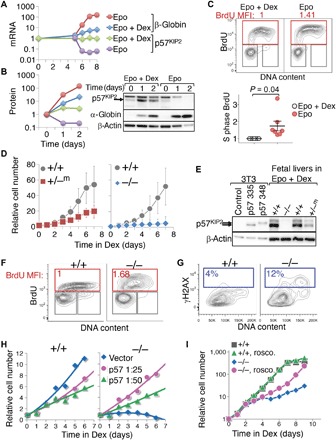

p57KIP2 is essential for self-renewal of CFUe in vitro

We next examined whether we could model the S-phase function of p57KIP2 in vitro. Glucocorticoids slow or arrest the differentiation of CFUe progenitors in culture, promoting extensive self-renewal instead (47, 50). Withdrawal of glucocorticoids from the culture precipitates the prompt induction of ETD and its completion within ~72 hours (47, 51, 52). The precise mechanism by which glucocorticoids promote self-renewal is not fully understood, but several pathways have been implicated recently (53–55). Here, we found that CFUe undergoing self-renewal in vitro in the presence of the synthetic glucocorticoid Dex expressed p57KIP2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 5, A and B). Withdrawal of Dex resulted in rapid induction of erythroid gene transcription and also in a rapid (<24 hours) loss of p57KIP2 expression (Fig. 5, A and B). These changes in p57KIP2 expression were associated with corresponding cell cycle changes: CFUe undergoing self-renewal in the presence of Dex had a slow intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate that increased abruptly with the withdrawal of Dex (Fig. 5C) (in measurements taken 20 to 60 hours after Dex withdrawal, BrdU MFI increased by 74 ± 29%, mean ± SEM, P = 0.04). The stimulatory impact of p57KIP2 down-regulation on intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate following Dex withdrawal mirrors our observations in vivo, during the switch to ETD at the S0/S1 transition (fig. S1, C and D, and Fig. 1, C to E).

Fig. 5. p57KIP2 is essential to CFUe self-renewal in vitro.

(A) p57KIP2 mRNA levels during CFUe self-renewal in vitro and following the switch to differentiation. Wild-type S0 cells were cultured for 5 days in self-renewal medium (“Dex + Epo”). Cells were washed and then placed either in differentiation medium (“Epo”) or back in self-renewal medium (“Epo + Dex”). Dex withdrawal leads to rapid down-regulation of p57KIP2 and to concurrent rapid induction of erythroid genes, such as α-globin or β-globin. mRNA measured by qRT-PCR, normalized to β-actin, and expressed relative to t = 0. (B) Western blot and protein band quantification during CFUe self-renewal in vitro and following the switch to differentiation. Experiment as in (A); on day 0, CFUe progenitors were replaced either in self-renewal medium (Epo + Dex) or in differentiation medium (Epo). The p57KIP2 band was identified using control cells transduced with retroviral vector expressing p57KIP2, as in (E). The uppermost band on the p57KIP2 blot is an unrelated cross-reacting band seen in Epo + Dex cultures [see (E)]. Legend as in (A), except that blue diamonds and red circles represent α-globin. (C) Cell cycle status of CFUe during self-renewal in vitro (Epo + Dex) and 20 to 60 hours following Dex withdrawal (Epo). BrdU MFI in Epo is expressed relative to its value in matched control cells undergoing Dex-dependent self-renewal. Top: Representative example. Bottom: Summary of seven matched cultures from three independent experiments. Statistical significance, paired t test. (D) p57KIP2-deficient S0 CFUe cells fail to self-renew in vitro. S0 cells derived from individual wild-type or littermate p57KIP2-deficient fetal livers were cultured in medium containing Epo + Dex. Cell numbers are relative to t = 0, mean ± SE of four (for +/−m) or five (for −/−) embryos. See also fig. S4A. (E) Western blot of p57KIP2 protein on day 9 of Dex-dependent CFUe self-renewal in vitro. Control 3T3 cells transduced with either empty vector or vectors expressing each of two p57KIP2 isoforms are also shown. Fetal liver cells express only the shorter 335–amino acid isoform of p57KIP2. Low levels of the p57KIP2 protein are also detectable in p57KIP2+/−m cells following 9 days of culture in Epo + Dex (see also fig. S4, B and C). Note that the top band is an unrelated cross-reacting band. (F) Increased intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in p57KIP2-deficient CFUe undergoing Dex-dependent self-renewal in vitro for 6 days. BrdU MFI in the S-phase gate is expressed relative to the wild-type littermate value. Representative of three independent experiments. (G) Increased number of γH2AX-positive cells in p57KIP2−/− CFUe undergoing Dex-dependent self-renewal, relative to wild-type littermate culture. Representative of three independent experiments. (H) p57KIP2 rescues p57KIP2-deficient CFUe self-renewal. p57KIP2-deficient S0 cells were transduced with low-titer virus (viral supernatant at the indicated dilutions) encoding p57KIP2 or with empty vector. Cells transduced with p57KIP2 showed significant improvement in self-renewal. Wild-type S0 cells transduced in parallel showed a reduction in self-renewal rate. (I) The CDK inhibitor drug roscovitine rescues self-renewal of p57KIP2-deficient CFUe. p57KIP2−/− S0 cells and wild-type S0 cells from littermate embryos were harvested and cultured in self-renewal medium containing Epo + Dex in the presence or absence of roscovitine. See also fig. S6B.

Next, we assessed the role of p57KIP2 during CFUe self-renewal in vitro. We established Dex cultures from individual fetal livers of either p57KIP2-deficient or wild-type littermate embryos. By day 6, the number of self-renewing cells in the wild-type cultures increased 50-fold. By contrast, there was no amplification of cells in cultures from p57KIP2−/− fetal livers, suggesting a novel, essential role for p57KIP2 during Dex-dependent self-renewal in vitro (Fig. 5D and fig. S4A; n = 5 independent cultures from individual p57KIP2−/− embryos and 4 cultures from wild-type littermates). p57KIP2+/−m cultures showed an intermediate but significantly reduced amplification compared with wild type (17-fold) (n = 4 independent p57KIP2+/−m cultures and 4 cultures from wild-type littermates) (Fig. 5D and fig. S4A). The difference between p57KIP2−/− and p57KIP2+/−m cultures is likely explained by a low level of expression of p57KIP2 in the p57KIP2+/−m cultures (Fig. 5E), which became evident with increasing days in culture (fig. S4, B and C). It may represent a selective advantage for cells in which the imprinted p57KIP2 allele was incompletely silenced, further underscoring the importance of p57KIP2 expression to CFUe self-renewal. Notably, there was no compensatory up-regulation of either p21CIP1 or p27KIP2 in Dex cultures of p57KIP2-deficient cells (fig. S4, B and C).

The failure of p57KIP2-deficient CFUe to undergo self-renewal was associated with a substantial increase in cell death (fig. S5). The intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in cultures of p57KIP2-deficient CFUe was increased compared with matching wild-type cultures (Fig. 5F). Further, consistent with our observations in vivo, the frequency of γH2AX-positive cells was also elevated (Fig. 5G). DNA damage associated with faster replication is therefore a likely cause of cell death in p57KIP2-deficient CFUe in vitro, analogous to the death of S0 CFUe in vivo (Figs. 3G and 4D). DNA damage leading to cell death may potentially explain the apparently paradoxical requirement for a CDK inhibitor during self-renewal and population growth. We were able to restore self-renewal potential to the p57KIP2−/− CFUe cultures by transducing the p57KIP2−/− cells with retroviral vectors expressing p57KIP2 (Fig. 5H), indicating that this effect is cell-autonomous.

In summary, we successfully modeled in vitro the novel functions that we first uncovered for p57KIP2 during S phase of CFUe progenitors in vivo. Our results show that p57KIP2 is expressed in self-renewing CFUe both in vitro and in vivo, where it slows intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, protects cells from DNA damage during DNA replication, and promotes cell viability. The switch to differentiation both in vivo and in vitro entails rapid down-regulation of p57KIP2, with ensuing increased intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate and S-phase shortening.

p57KIP2-mediated CDK inhibition underlies its S-phase functions

The Cip/Kip family member p21CIP1 interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), inhibiting S-phase DNA synthesis during the DNA damage response (56, 57). However, murine p57KIP2 lacks a PCNA interaction domain (58). To investigate the mechanisms underlying p57KIP2-mediated regulation of S-phase duration, we generated two distinct p57KIP2 point mutants within its conserved CDK-binding motif, p57W50G and p57F52A/F54A (59, 60). Neither of these mutants, when expressed in S0 cells, significantly inhibited intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, whereas cells transduced in parallel with similar levels of wild-type p57KIP2 successfully slowed or arrested S phase (fig. S6A). This result suggests that CDK binding by p57KIP2, and the likely ensuing CDK inhibition, mediates its intra–S-phase slowing of DNA synthesis.

We also investigated whether CDK inhibition could underlie the essential role that p57KIP2 plays in maintaining the viability of self-renewing CFUe. We treated p57KIP2-deficient fetal liver CFUe with the CDK inhibitor roscovitine, which preferentially inhibits S-phase cyclin/CDK activity (61). We found that a low concentration of roscovitine (0.5 μM) successfully rescued Dex-dependent self-renewal and expansion of p57KIP2-deficient CFUe while having little effect on the normal expansion of CFUe cultures derived from wild-type littermates (Fig. 5I). Population growth in cultures containing roscovitine was the result of CFUe self-renewal, as shown by their preserved CFUe colony potential (fig. S6B). Thus, paradoxically, inhibition of CDK activity promotes CFUe viability and self-renewal potential, in agreement with the essential requirement for p57KIP2 for these functions. Together, these results show that CDK inhibition is the likely mechanism through which p57KIP2 both suppresses intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate and promotes the viability and self-renewal potential of early erythroid progenitors.

Faster replication forks underlie S-phase shortening at the S0/S1 transition

CDK activity is required for the firing of origins of replication (62, 63). Suppression of CDK activity, leading to reduced origin firing, was recently implicated in the lengthening of S phase at the midblastula transition (64). Given the role of p57KIP2 both in CDK inhibition and in slowing intra–S-phase DNA synthesis, we sought to determine whether there were associated changes in origin firing frequency. To this end, we used DNA combing, a single-molecule DNA fiber approach that allows effects on origin firing and fork progression to be deconvoluted (65, 66). We explanted littermate wild-type and p57KIP2+/−m fetal livers at midgestation, allowing fetal liver cells to recover for 4 hours at 37°C. We then pulsed the cells for 10 min with 25 μM of the deoxynucleoside analog iododeoxyuridine (IdU). This was followed by a pulse of an eightfold higher concentration of a second deoxynucleoside analog, chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU), to abruptly switch from IdU to CldU and allow determination of fork directionality (Fig. 6A). The fetal liver cells were then placed on ice, and S0 and S1 cells were sorted by flow cytometry. Genomic DNA was combed from each of the wild-type and p57KIP2+/−m S0 and S1 populations, by isolating and stretching on glass coverslips. Combed DNA was stained for IdU (green fluorescence) and CldU (red fluorescence) incorporation and for single-stranded DNA (Fig. 6B, blue fluorescence). We measured distances between adjacent origins and the speed of forks during the IdU pulse (Fig. 6B). Only forks that moved throughout the IdU pulse, as reflected by immediately adjacent and consecutive blue, green, and red/yellow tracks, were included in the analysis of fork speed (Fig. 6B). (Of note, the beginning of CldU incorporation into the replication bubble is recognized at the point of first appearance of red fluorescence, whether or not green IdU fluorescence is simultaneously also present, together labeling as yellow; this is because intracellular IdU is still present at the onset of the second pulse. Where all three antibodies label DNA, the resulting color is white.) About 20 Mb was examined for each of the wild-type and p57KIP2+/−m S0 and S1 DNA, with an average fiber length of 1 Mb for each of the four samples (fig. S7A). We found no significant difference in the inter-origin distance between wild-type S0 and S1 cells or between wild-type and corresponding p57KIP2+/−m cells (Fig. 6C and fig. S7B). Fork speed in wild-type S1 cells was increased by 56% compared to wild-type S0 (2.43 ± 0.11 versus 1.56 ± 0.08 kb/min in S1 and S0, respectively, mean ± SE, P < 10−8). A similar result was obtained in an independent experiment in which S0 and S1 cells from a different inbred wild-type mouse strain (BALB/c) were similarly analyzed (fig. S8, A and B). Therefore, S-phase shortening in S1 in wild-type cells is the result of a significant global increase in fork processivity and does not reflect a change in origin firing efficiency.

Fig. 6. Global increase in replication fork speed at the transition from S0 to S1, regulated by p57KIP2.

(A) Experimental design. Fetal livers were individually explanted and allowed to recover for 4 hours at 37°C. After genotyping, all embryos of the same genotype (either +/+ or +/−m) were pooled and pulsed with IdU for 10 min, followed by CldU. Cells were then placed at 4°C, sorted into S0 and S1 subsets by flow cytometry, and processed for DNA combing. (B) Portion of a DNA fiber illustrating the identification and measurement of replication structures. For clarity, the same fiber is shown twice, with (bottom) or without (top) the blue fluorescence channel. IdU tracks are labeled green and are used to measure fork speed. CldU tracks are labeled red or yellow because, in addition to CldU (red), they contain DNA incorporating residual IdU (green). The red/yellow tracks are used to obtain fork directionality. Note that for fiber sections, where there is equivalent staining for red, blue, and green (which may occur during the second pulse), the fiber appears white (the sum total of red, green, and blue in the RGB color format); this does not reflect saturation of signal. See also fig. S9 for an example of a full microscope field. The blue fluorescence allows assessment of the DNA fiber continuity between replication bubbles or forks. This therefore allows localization of origins (marked “o”) as either equidistant from two forks proceeding in opposite directions or in the center of a green (IdU) track bordered by two red (CldU) tracks. The former is an origin that fired before the IdU pulse, whereas the latter is an origin that fired during the IdU pulse. Identification of origins allows the measurement of inter-origin distances as shown. Fork speed was measured as the length of green (IdU) tracks (in kilobase) for forks that moved throughout the IdU pulse (immediately adjacent blue, green, and red tracks) and divided by the duration of the pulse (10 min). (C) Scatter plots showing inter-origin distances (top) and fork speeds (bottom) for a single experiment, in which littermates p57KIP2+/−m and wild-type embryos were analyzed. See fig. S7 for additional analysis including fiber length distributions. P values are for a two-tailed t test of unequal variance between the indicated samples. Inter-origin distance was not significantly different between any of the samples. (D) Examples of fork trajectories during the 10-min IdU pulse from the data set in (C). The yellow dashed line indicates the transition from IdU to CldU. Only the IdU track was used for measurement of fork speed. (E) Violin plots for the data shown in (C).

Consistent with our earlier result showing premature S-phase shortening in p57KIP2-deficient embryos (Fig. 4, A and B), we found a 35% increase in fork speed of p57KIP2+/−m S0 cells compared with wild-type S0 cells (2.11 ± 0.09 kb/min versus 1.56 ± 0.08 kb/min, respectively; P = 10−5) (Fig. 6, C to E). Finally, there was a further 30% increase in fork speed with the transition from S0 to S1 in p57KIP2+/−m fetal liver (P = 0.0004; Fig. 6, C to E). Thus, p57KIP2 normally restrains S0 DNA synthesis rate by inhibiting fork processivity, as indicated by the elevated fork speed in p57KIP2+/−m S0 cells. Although fork speed in p57KIP2+/−m S0 cells is substantially faster than in wild-type S0, it is nevertheless still somewhat slower than fork speeds seen in S1 of the same fetal livers (Fig. 6, C and E). Together, these findings suggest that S-phase shortening at the S0 to S1 transition in wild-type cells is the result of down-regulation of p57KIP2, which restrains intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate in S0 cells by globally suppressing the processivity of replication forks.

We also used DNA combing to analyze the underlying mechanism of p57KIP2-mediated slowing of DNA synthesis rate during Dex-dependent CFUe self-renewal in vitro. In agreement with our findings in vivo, p57KIP2 deficiency resulted in significantly faster replication forks, with no significant change in inter-origin distance (fig. S8C).

DISCUSSION

We describe an acute change in S-phase duration and in the underlying dynamics of DNA replication, integral to an S phase–dependent erythroid cell fate decision. We show that the transition from self-renewal to ETD in CFUe progenitors entails a rapid increase in intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, resulting in a 40% shorter S phase. S-phase shortening is the result of an abrupt, global increase in the processivity of replication forks. We identify the CDKI p57KIP2 as a principal regulator of this process. p57KIP2 is expressed in S phase of self-renewing CFUe progenitors, where, through novel functions for this protein, it restrains the speed of replication forks, protecting cells from replication-associated DNA damage and maintaining cell viability. p57KIP2 down-regulation during the switch to ETD causes the observed increase in replication fork speed and a shorter S phase. Finally, we show that CDK inhibition by p57KIP2 is a likely mediator of its S-phase functions.

Three independent lines of evidence support our finding that S phase becomes faster and shorter during this cell fate switch. First, intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate, as measured by BrdU incorporation rate, increased by ~50% (fig. S1) (23, 28). Second, the double-deoxynucleoside label approach, which measures the fraction of cells that leave S phase during a known time interval, independently confirmed S-phase shortening, from 7 to 4 hours (Fig. 1). Third, we found a global, ~50% increase in the speed of replication forks, as measured by DNA combing (Fig. 6 and fig. S8A). In addition to these findings in vivo, activation of ETD in Dex-dependent CFUe cultures in vitro is also tightly associated with S-phase shortening (Fig. 5F)—a process that is similarly caused by a global increase in replication fork speed (fig. S8C).

It is well established that DNA replication is reprogrammed during differentiation, as reflected by changes in usage of replication origins and in the timing of replication of chromatin domains (67–69). Our work shows that, in addition, the switch from self-renewal to differentiation fundamentally alters the replication program in an additional key respect through a global increase in replication fork speed. In model organisms, marked developmental changes in S-phase duration have been clearly linked to changes in origin firing (30). The speed of replication forks was implicated as a regulatory target in the DNA damage response (70–73) but not in developmental decisions in normal physiology. A recent report of faster forks in germinal center B cells receiving T cell help (74), together with our findings here in erythroid progenitors, raise the possibility that regulatory changes in global fork speed may be an intrinsic part of mammalian physiological developmental programs.

It is unclear at this time how faster DNA synthesis rate might affect chromatin metabolism. We previously found that the rapid increase in intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate at the S0/S1 transition is required for an unusual process of replication-dependent global DNA demethylation, which functions to accelerate erythroid gene transcription (28). Thus, an intriguing possibility is that the elevated speed of the replication fork reduces the efficiency of DNA methylation and potentially alters other DNA methylation–dependent epigenetic marks, thereby affecting cell fate. Increased fork speed per se, although necessary, is not sufficient for precipitating a cell fate decision because p57KIP2-deficient S0 cells did not appear to undergo premature ETD in spite of their prematurely fast DNA synthesis rate.

Our work identifies a novel S-phase function for the CDKI p57KIP2. p57KIP2 is an established negative regulator of the transition from G1 to S phase, although it was shown to associate with and inhibit both G1- and S-phase cyclin/CDK complexes in vitro (37, 38). Here, we present several lines of evidence strongly suggesting that p57KIP2 lengthens S phase by globally suppressing replication fork processivity. We found that p57KIP2 mRNA and protein were specifically expressed in S phase of S0 CFUe (Fig. 2, A to C). Knockdown (Fig. 2, D and E) or exogenous overexpression of p57KIP2 in these cells (Fig. 2F and fig. S2) correspondingly altered intra–S-phase DNA synthesis in a dose-dependent manner. Finally, in p57KIP2-deleted embryos, intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate and global fork speed were both increased by ~50% in S0 cells in vivo (Figs. 4, A and B, and 6, C to E) and in vitro (Fig. 5F and fig. S8C).

Unlike p21CIP1, which interacts with PCNA to retard replication forks during the DNA damage response (57, 75), the slowing of S phase by p57KIP2 depends on its binding and likely inhibition of cyclin/CDK complexes (fig. S6). Our work therefore suggests that, in addition to the known requirement for CDK activity in origin firing (62, 63), it also regulates the processivity of replication forks. Future work will be needed to test this hypothesis and to identify the critical CDK targets.

We found that p57KIP2 promotes the viability of self-renewing CFUe progenitors in S0 in vivo (Fig. 3G) and in vitro (Fig. 5D and fig. S5). Viability and self-renewal were restored to p57KIP2-deficient CFUe in vitro by retroviral transduction of p57KIP2 (Fig. 5H) or by treatment with the CDK inhibitor drug roscovitine (Fig. 5I), demonstrating the cell-autonomous and cell-specific, CDK-inhibitory role of p57KIP2 in these functions. The apparently paradoxical requirement for CDK inhibition in the expansion of CFUe might be explained, at least in part, by the replication stress that results in its absence. Replication stress, which entails the slowing or stalling of replication fork progression and/or DNA synthesis (70), is evident in p57KIP2-deficient cells from the increased number of γH2AX-positive cells that are largely arrested in S phase of the cycle (Figs. 4, C to F, and 5G and fig. S3). Therefore, by restraining the speed of replication forks, p57KIP2 protects CFUe cells from replication stress and promotes their viability. Unlike S0 cells, S1 cells do not undergo increased apoptosis, in spite of their faster replication forks. Further, S1 cells have lower levels of γH2AX than S0 cells. It will therefore be of interest to investigate whether the transition from S0 to S1 entails an adaptation that preserves the viability of these cells in the face of faster forks. Nevertheless, we previously found that cells at the S0/S1 transition are particularly sensitive to hydroxyurea (23), a finding that might be explained by the increased speed of replication forks.

These novel S-phase functions of p57KIP2 may also underlie the apoptosis and abnormal development of non-erythroid tissue progenitors in p57KIP2 embryos (48, 49) and in patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome secondary to p57KIP2 mutations (76, 77). Specifically, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) deficient in p57KIP2 have a severe deficit in self-renewal capacity, which impairs their ability to engraft and was attributed to reduced quiescence (78, 79). Our work suggests that, in addition, p57KIP2 may enhance HSC self-renewal by restraining intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate and reducing replication-associated DNA damage. The finding that p57KIP2 is an essential mediator of Dex-dependent CFUe expansion cultures provides a novel insight into the mechanism by which glucocorticoids sustain these cultures, and is of potential translational relevance in the development of mass production of erythroid progenitors in vitro that rely on this culture system (52, 80).

In conclusion, our work uncovers previously unknown regulation of S-phase replication dynamics that is integral to cell developmental states in the erythroid lineage. It shows that CDK inhibition and slow forks are essential to the viability of self-renewing progenitors and that a rapid global increase in fork speed takes place with the switch to differentiation. It identifies the Cip/Kip CDKI protein p57KIP2 as a regulator of fork speed and raises the possibility of similar mechanisms operating during other instances of S phase–dependent cell fate decisions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Female mice heterozygous for a deletion of the cdkn1c gene (B6.129S7-Cdkn1ctm1Sje/J, Jackson Laboratory stock no. 000664) were bred with wild-type C57BL/6J mice or male cdkn1c heterozygous mice. All experiments were done with littermate p57KIP2-deficient or wild-type control embryos. All embryos were genotyped before further processing of the fetal livers.

Isolation and flow cytometric analysis of erythroid progenitors

Fetal livers were harvested from midgestation mouse embryos (E12.5 to E13.5), mechanically dissociated, labeled with antibodies to CD71 and Ter119 and with lineage markers, and sorted by flow cytometry as described (23, 81). Cells were sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) using a 100-μm nozzle. Flow cytometric analysis was done on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) cytometer. FACS data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.). In some experiments, S0 cells were isolated from fetal liver cells using EasySep magnetic beads (StemCell Technologies) by negative sorting for CD71, Ter119, Gr1, Mac1, and CD41.

Antibodies used in flow cytometric and EasySep purifications

The following antibodies were used in flow cytometric and EasySep purifications: phycoerythrin (PE)/Cy7 rat anti-mouse CD71 (RI7217) (BioLegend 113812), PE rat anti-mouse Ter119 (Ter119) (BD Biosciences 553673), allophycocyanin (APC) rat anti-mouse Ter119 (Ter119) (BD Biosciences 557909), APC rat anti-mouse Ter119 (Ter119) (BD Biosciences 557909), biotin rat anti-mouse CD71 (C2) (BD Biosciences 557416), biotin rat anti-mouse Ter119 (BD Biosciences 553672), biotin rat anti-mouse Ly-6G and Ly-6C/Gr1 (RB6-8C5) (BD Biosciences 553125), biotin rat anti-mouse CD11b/Mac1 (M1/70) (BD Biosciences 557395), biotin rat anti-mouse CD41 (MWReg30) (Thermo Scientific MA1-82655), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) rat anti-mouse Ly-6G and Ly-6C/Gr1 (RB6-8C5) (BD Biosciences 553127), FITC rat anti-mouse CD11b/Mac1 (M1/70) (BD Biosciences 557396), FITC rat anti-mouse CD41 (MWReg30) (BD Biosciences 553848), FITC rat anti-mouse CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2) (BD Biosciences 553087), FITC hamster anti-mouse CD3e (145-2C11) (BD Biosciences 553061), PE annexin V (BD Biosciences 556421), and Alexa Fluor 488 mouse anti-H2AX (pS139) (N1-431) (BD Biosciences 560445).

Isolation of G1- and S-phase cells from S0 and S1 erythroid subsets

E13.5 fetal livers were harvested from wild-type BALB/cJ mice (Jackson Laboratory stock no. 000651), mechanically dissociated, resuspended at 106 cells/ml, and maintained at 37°C for 15 min with Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) (l-glutamine, 25 mM Hepes) (Gibco), 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco, HyClone), penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml; Invitrogen), 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and Epo (2 U/ml). Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml; Invitrogen H3570) was added for 40 min at 37°C. Cells were collected, washed, and labeled with antibodies to CD71, Ter119, and lineage markers and with the cell viability dye 7AAD (BD Biosciences 559925). Cells were then sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). G1- and S-phase cells in the S0 and S1 subsets were gated on the basis of DNA content, as reflected by Hoechst fluorescence.

Cell cycle analysis

Pregnant female mice at midgestation were injected with BrdU [200 μl of stock (10 mg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] intraperitoneally. E13.5 embryos were harvested 30 min later. To determine DNA replication rate in vitro, cells were pulsed at a final concentration of 33 μM BrdU for 30 min. Cells were immediately labeled with the LIVE/DEAD Kit (Invitrogen L23105), fixed, and permeabilized. Erythroid subsets were identified using anti-CD71 (BD Biosciences 113812) and anti-Ter119 (BD Biosciences 553673). BrdU incorporation and DNA content were detected by biotin-conjugated anti-BrdU (Abcam ab171059), streptavidin-conjugated APC (Invitrogen S868), and 7AAD (BD Biosciences 559925).

Measurement of S-phase duration

Pregnant female mice were intraperitoneally injected with 200 μl of EdU (3.3 mol/25 g mouse), followed either 1 or 2 hours later with BrdU (3.3 mmol/25 g mouse), and sacrificed 20 min following the second injection. Fetal livers were labeled with lineage markers Ter119 and CD71, and S0 and S1 cells were sorted. Sorted subsets were then labeled with the LIVE/DEAD Kit (Invitrogen L23105), fixed in 70% ethanol, denatured in 4 M hydrochloric acid, and washed in phosphate/citric buffer. EdU incorporation was detected using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Invitrogen C10425), and BrdU incorporation was detected using Alexa Fluor 647 mouse anti-BrdU (Invitrogen B35133).

In vitro CFUe expansion cultures (51, 82)

To isolate Ter119-negative cells, fresh fetal liver cells were stained with biotin-conjugated anti-Ter119 (BD Biosciences 553672) at a 1:100 ratio, followed by EasySep magnetic separation (StemCell Technologies). Cells were grown in StemPro-34 serum-free medium supplemented with nutrient supplement (Invitrogen), 1 μM Dex (Sigma), stem cell factor (SCF) (100 ng/ml; PeproTech), insulin-like growth factor 1 (40 ng/ml; PeproTech), Epo (2 U/ml), penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml; Invitrogen), and 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 2 × 106 cells/ml and supplemented daily with fresh medium and growth factors. To test the effect of roscovitine on p57KIP2−/− fetal liver cells in expansion culture, cells were grown and maintained as described above with the additional daily supplement of 0.5 μM roscovitine (EMD Millipore 557360). To switch to differentiation medium, after being maintained in expansion medium for 4 to 5 days, Ter119-negative cells were isolated again using EasySep magnetic beads (StemCell Technologies). Cells were then transferred to IMDM (l-glutamine, 25 mM Hepes) (Gibco), 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco, HyClone), penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml; Invitrogen), 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and Epo (2 U/ml).

Retroviral transduction with p57 constructs

Retroviral constructs were generated in the MSCV-IRES-hCD4 vector backbone, as described (23). p57 mutant (p57T329A) was previously described (23). CDK-binding mutants defective of p57W50G and p57F52A/F54A were generated using PCR with the following primers: CCAGAACCGCGGGGACTTCAACTTCC and TCCTCGGCGTTCAGCTCG (for p57W50G) and CGCCCAGCAGGATGTGCCTCTTC and TTGGCGTCCCAGCGGTTCTGGTC (for p57F52A/F54A). The entire open reading frame was sequenced to verify correct mutagenesis. Viral supernatants were prepared as described (23). S0 cells were transduced by spin infection at 2000 rpm, 30°C for 1 hour in fibronectin-coated dishes supplemented with polybrene (4 μg/ml) (Sigma). Cells were incubated with SCF (100 ng/ml) and interleukin-3 (IL-3) (10 ng/ml; PeproTech) overnight before cell cycle analysis.

Knockdown experiments

shRNA targeting p57KIP2 (clone SM22685-D-5 V2MM_81921) was subcloned into the LMP (MSCV/LTRmiR30-PIG) microRNA-adapted retroviral vector containing an “IRES-GFP” reporter (Open Biosystems). Similarly, a nonsilencing negative control shRNA (RHS4971, Open Biosystems) that is processed by the endogenous RNA interference pathway but will not target any mRNA sequence in mammals was subcloned into LMP. Sorted S0 cells were transduced with retroviral vectors, expressing shRNA for 16 hours in the presence of SCF and IL-3. Cells were then cultured for Epo ± Dex for 20 to 72 hours before cell cycle analysis.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from fetal liver cells using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Micro Kit and the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and quantified by the Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Reagent Kit (Thermo Scientific). The SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) was used in reverse transcription. qPCR was conducted in the ABI 7300 sequence detection system with TaqMan reagents and TaqMan MGB probes (Applied Biosystems).

TaqMan probes

The following TaqMan probes were used: β-actin (Mm02619580_g1), β-globin (Mm01611268_g1), p21CIP1 (Mm00432448_m1), p27KIP1 (Mm00438168_m1), and p57KIP2 (Mm01272135_g1).

Western blot analysis

Sorted fetal liver cells or fetal liver cells from expansion and differentiation cultures were incubated in lysis buffer [1% NP-40, 50 mM tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol supplemented with protease inhibitors] and rotated at 4°C for 30 min. Supernatants were prepared by centrifugation at 4°C for 15 min and quantified by the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). Protein electrophoresis was carried out using the NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gel System and the Bolt Bis-Tris Plus Gel System (Invitrogen). Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were probed with antibodies against p57KIP2 (Abcam ab75974), β-actin (Abcam ab8227), p21CIP1 (Abcam ab109199), p27KIP1 (Cell Signaling Technology 3698), and α-globin (Abcam ab92492). Target protein bands were detected by ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad) and quantified using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad). Negative and positive controls were used in all Western blots, consisting of lysates of either 3T3 or 293T cells, transduced with either “empty vector” or retroviral vector expressing the relevant test protein.

DNA combing

Freshly harvested fetal liver cells were allowed to recover in Epo-containing medium at 37°C for 4 hours. They were then pulsed with IdU (25 μM) for 10 min, followed immediately, without intervening washes, by a CldU pulse (200 μM) for 20 min. Cells were labeled with CD71 and Ter119 antibodies as described above, and subsets S0 and S1 were sorted by flow cytometry. The sorted cells were washed in PBS and embedded in agarose plugs (0.75% low-melt agarose; Bio-Rad). Plugs were incubated in proteinase K (0.2 mg/ml; Roche) solution at 37°C for 48 hours. After extensive washing, agarose plugs were melted and digested with β-agarase. Genomic DNA was gently resuspended in 0.2 M MES buffer (pH 5.4) and combed on silanized coverslips using the Molecular Combing System (Genomic Vision). Combed DNA was denatured in 2 M hydrochloric acid and labeled with rat anti-BrdU (Abcam ab6326) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG; Life Technologies A11007) to identify IdU tracks, with mouse anti-BrdU (BD Biosciences 347580) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen A11029) to identify CldU tracks, and with anti–single-stranded DNA rabbit IgG (Immuno-Biological Laboratories Co. Ltd. 18731), biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (BD Biosciences 550338), BV421 streptavidin (BioLegend 405226), and BV421 anti-human IgG (BioLegend 409317) to identify single-stranded DNA fibers.

Fluorescence microscopy was carried out on a Zeiss Axioskop 40 fluorescence microscope. Separate exposures were taken for red, blue, and green fluorescence for each field and merged using the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP). Up to 40 consecutive fields were photographed and merged digitally for each of the final image files that were then analyzed by a scientist that was blinded to sample identity. DNA track lengths were measured using GIMP. IdU track lengths were tracks that were labeled only with green fluorescence. Examples of original fluorescence images are shown in fig. S9 and in the Supplementary Image files. The spreadsheet data set for the DNA combing experiment in Fig. 6 and fig. S7 is in data file S1.

Cell cycle and γH2AX analysis in vivo

Pregnant female mice were intraperitoneally injected with 200 μl of BrdU (10 mg/ml). Mice were sacrificed at 30 min after injection. Fetal livers were fixed and permeabilized; digested with deoxyribonuclease (DNase) I; labeled for BrdU incorporation, non-erythroid lineage markers, and cell surface markers CD71 and Ter119; and analyzed by flow cytometry. Where indicated, cells were labeled with antibodies against γH2AX before the DNase I digestion.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare measured parameters from the three different genotypes (wild-type, p57KIP2+/−m, and p57KIP2−/−) with the GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. Statistical significance of the DNA combing data was assessed using Student’s t test. Mann-Whitney test was used for non-normally distributed data sets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Yu (University of Virginia) for generously providing the p57KIP2-null mice. Funding: This work was funded by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar award LLS 1728-13, R01DK100915, and R01DK099281 (M.S.), R01CA095175 (R.S.), and R01GM098815 (N.R.). Author contributions: M.S. conceived the work, designed and performed experiments, and analyzed data; Y.H., D.H., R.P., and M.F. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data; N.R., D.R.I., and R.S. contributed to experimental design; Y.H. and M.S. wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/5/e1700298/DC1

fig. S1. The transition from self-renewal to differentiation at S0/S1 is associated with a transient increase in intra–S-phase DNA synthesis rate.

fig. S2. p57KIP2 exerts dose-dependent inhibition of DNA synthesis within S-phase cells.

fig. S3. Increased γH2AX in p57KIP2-deficient fetal liver.

fig. S4. Analysis of p57KIP2-deficient CFUe undergoing self-renewal in vitro.

fig. S5. Increased cell death in p57KIP2−/− S0 CFUe during self-renewal in vitro.

fig. S6. CFUe self-renewal requires the CDK-binding and inhibition functions of p57KIP2.

fig. S7. DNA combing analysis of freshly explanted fetal livers from wild-type and p57KIP2+/−m embryos associated with the experiment in Fig. 6.

fig. S8. DNA combing experiments.

fig. S9. DNA combing: Example of fluorescence image file used for scoring data.

data file S1. Spreadsheet containing the data set for the DNA combing experiment in Fig. 6.

Image files

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Lim S., Kaldis P., Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: Roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development 140, 3079–3093 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu W., Schneider J. W., Condorelli G., Kaushal S., Mahdavi V., Nadal-Ginard B., Interaction of myogenic factors and the retinoblastoma protein mediates muscle cell commitment and differentiation. Cell 72, 309–324 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird J. J., Brown D. R., Mullen A. C., Moskowitz N. H., Mahowald M. A., Sider J. R., Gajewski T. F., Wang C.-R., Reiner S. L., Helper T cell differentiation is controlled by the cell cycle. Immunity 9, 229–237 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu L., Skoultchi A. I., Coordinating cell proliferation and differentiation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 91–97 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai J., Weiss M. L., Rao M. S., In search of “stemness”. Exp. Hematol. 32, 585–598 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzales K. A. U., Liang H., Lim Y.-S., Chan Y.-S., Yeo J.-C., Tan C.-P., Gao B., Le B., Tan Z.-Y., Low K.-Y., Liou Y.-C., Bard F., Ng H.-H., Deterministic restriction on pluripotent state dissolution by cell-cycle pathways. Cell 162, 564–579 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton S., Linking the cell cycle to cell fate decisions. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 592–600 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weintraub H., Assembly of an active chromatin structure during replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 7, 781–792 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolffe A. P., Implications of DNA replication for eukaryotic gene expression. J. Cell Sci. 99 (Pt. 2), 201–206 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henikoff S., Nucleosome destabilization in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 15–26 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu C.-P., Blau H. M., Reprogramming cell differentiation in the absence of DNA synthesis. Cell 37, 879–887 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartenstein V., Posakony J. W., Sensillum development in the absence of cell division: The sensillum phenotype of the Drosophila mutant string. Dev. Biol. 138, 147–158 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edgar B. A., O’Farrell P. H., The three postblastoderm cell cycles of Drosophila embryogenesis are regulated in G2 by string. Cell 62, 469–480 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris W. A., Hartenstein V., Neuronal determination without cell division in Xenopus embryos. Neuron 6, 499–515 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Nooij J. C., Hariharan I. K., Uncoupling cell fate determination from patterned cell division in the Drosophila eye. Science 270, 983–985 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller A. M., Nasmyth K. A., Role of DNA replication in the repression of silent mating type loci in yeast. Nature 312, 247–251 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aparicio O. M., Gottschling D. E., Overcoming telomeric silencing: A trans-activator competes to establish gene expression in a cell cycle-dependent way. Genes Dev. 8, 1133–1146 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgar L. G., McGhee J. D., DNA synthesis and the control of embryonic gene expression in C. elegans. Cell 53, 589–599 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weigmann K., Lehner C. F., Cell fate specification by even-skipped expression in the Drosophila nervous system is coupled to cell cycle progression. Development 121, 3713–3721 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forlani S., Bonnerot C., Capgras S., Nicolas J. F., Relief of a repressed gene expression state in the mouse 1-cell embryo requires DNA replication. Development 125, 3153–3166 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambros V., Cell cycle-dependent sequencing of cell fate decisions in Caenorhabditis elegans vulva precursor cells. Development 126, 1947–1956 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher D., Méchali M., Vertebrate HoxB gene expression requires DNA replication. EMBO J. 22, 3737–3748 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pop R., Shearstone J. R., Shen Q., Liu Y., Hallstrom K., Koulnis M., Gribnau J., Socolovsky M., A key commitment step in erythropoiesis is synchronized with the cell cycle clock through mutual inhibition between PU.1 and S-phase progression. PLOS Biol. 8, e1000484 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory C. J., Tepperman A. D., McCulloch E. A., Till J. E., Erythropoietic progenitors capable of colony formation in culture: Response of normal and genetically anemic W/WV mice to manipulations of the erythron. J. Cell. Physiol. 84, 1–12 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara H., Ogawa M., Erythropoietic precursors in mice with phenylhydrazine-induced anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 1, 453–458 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantor A. B., Orkin S. H., Transcriptional regulation of erythropoiesis: An affair involving multiple partners. Oncogene 21, 3368–3376 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wontakal S. N., Guo X., Smith C., MacCarthy T., Bresnick E. H., Bergman A., Snyder M. P., Weissman S. M., Zheng D., Skoultchi A. I., A core erythroid transcriptional network is repressed by a master regulator of myelo-lymphoid differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 3832–3837 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shearstone J. R., Pop R., Bock C., Boyle P., Meissner A., Socolovsky M., Global DNA demethylation during mouse erythropoiesis in vivo. Science 334, 799–802 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spradling A., Orr-Weaver T., Regulation of DNA replication during Drosophila development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 21, 373–403 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordman J., Orr-Weaver T. L., Regulation of DNA replication during development. Development 139, 455–464 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foe V. E., Mitotic domains reveal early commitment of cells in Drosophila embryos. Development 107, 1–22 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duronio R. J., Developing S-phase control. Genes Dev. 26, 746–750 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKnight S. L., Miller O. L. Jr, Electron microscopic analysis of chromatin replication in the cellular blastoderm Drosophila melanogaster embryo. Cell 12, 795–804 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snow M. H. L., Bennett D., Gastrulation in the mouse: Assessment of cell populations in the epiblast of tw18/tw18 embryos. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 47, 39–52 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mac Auley A., Werb Z., Mirkes P. E., Characterization of the unusually rapid cell cycles during rat gastrulation. Development 117, 873–883 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Farrell P. H., Stumpff J., Su T. T., Embryonic cleavage cycles: How is a mouse like a fly? Curr. Biol. 14, R35–R45 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuoka S., Edwards M. C., Bai C., Parker S., Zhang P., Baldini A., Wade Harper J., Elledge S. J., p57KIP2, a structurally distinct member of the p21CIP1 Cdk inhibitor family, is a candidate tumor suppressor gene. Genes Dev. 9, 650–662 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee M.-H., Reynisdóttir I., Massagué J., Cloning of p57KIP2, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor with unique domain structure and tissue distribution. Genes Dev. 9, 639–649 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pateras I. S., Apostolopoulou K., Niforou K., Kotsinas A., Gorgoulis V. G., p57KIP2: “Kip”ing the cell under control. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1902–1919 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Besson A., Dowdy S. F., Roberts J. M., CDK inhibitors: Cell cycle regulators and beyond. Dev. Cell 14, 159–169 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Socolovsky M., Nam H.-s., Fleming M. D., Haase V. H., Brugnara C., Lodish H. F., Ineffective erythropoiesis in Stat5a−/−5b−/− mice due to decreased survival of early erythroblasts. Blood 98, 3261–3273 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J., Socolovsky M., Gross A. W., Lodish H. F., Role of Ras signaling in erythroid differentiation of mouse fetal liver cells: Functional analysis by a flow cytometry-based novel culture system. Blood 102, 3938–3946 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scully R., Chen J., Ochs R. L., Keegan K., Hoekstra M., Feunteun J., Livingsto D. M., Dynamic changes of BRCA1 subnuclear location and phosphorylation state are initiated by DNA damage. Cell 90, 425–435 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ge X. Q., Jackson D. A., Blow J. J., Dormant origins licensed by excess Mcm2–7 are required for human cells to survive replicative stress. Genes Dev. 21, 3331–3341 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monette F. C., LoBue J., Gordon A. S., Alexander P. Jr, Chan P.-C., Erythropoiesis in the rat: Differential rates of DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Science 162, 1132–1134 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martynoga B., Morrison H., Price D. J., Mason J. O., Foxg1 is required for specification of ventral telencephalon and region-specific regulation of dorsal telencephalic precursor proliferation and apoptosis. Dev. Biol. 283, 113–127 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]