Abstract

Background:

Ephedra is among Palestinian medicinal plants that are traditionally used in folkloric medicine for treating many diseases. Ephedra is known to have antibacterial and antioxidant effects. The goal of this study is to evaluate the antioxidant activity of different extracts from the Ephedra alata plant growing wild in Palestine, and to analyze their phenolic and flavonoid constituents by HPLC/PDA and HPLC/MS.

Materials and Methods:

Samples of the Ephedra alata plant grown wild in Palestine were extracted with three different solvents namely, 100% water, 80% ethanol, and 100% ethanol. The extracts were analyzed for their total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), antioxidant activity (AA), as well as phenolic and flavonoids content by HPLC/PDA/MS.

Results:

The results revealed that the polarity of the extraction solvent affects the TPC, TFC, and AA of extracts. It was found that both TPC and AA are highest for plant extracted with 80% ethanol, followed by 100% ethanol, and finally with 100% water. TFC however was highest in the following order: 100% ethanol > 80% ethanol > water. Pearson correlation indicated that there is a significant correlation between AA and TPC, but there is no correlation between AA and TFC. Simultaneous HPLC-PDA and UHPLC-MS analysis of the ethanolic plant extracts revealed the presence of Luteolin-7-O-glucuronide flavone, Myricetin 3-rhamnoside and some other major polyphenolic compounds that share myricetin skeleton.

Conclusion:

Ephedra alata extract is rich in potent falvonoid glycosidic compounds as revealed by their similar overlaid UV-Vis spectra and UHPLC-MS results. On the basis of these findings, it is concluded that Ephedra alata constitutes a natural source of potent antioxidants that may prevent many diseases and could be potentially used in food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical products.

Keywords: Ephedra Alata, HPLC, LC/MS, antioxidant activity, phenolic content, flavonoid content

Introduction

Ephedra is a medicinal plant belonging to the Ephedraceae family. There are many Ephedra species present worldwide, among these are Ephedra Alata, Ephedra Lristanica, Ephedra Sarcocarpa, Ephedra strobiliacea, Ephedra procera, and Ephedra pachyclada (Rustaiyan et al. (2011). Ephedra alata grows widely in Palestine. It is used in traditional medicine to treat allergies, bronchial asthma, chills, colds, coughs, edema, fever, flu, headaches. This plant also shows antimicrobial and anticancer activities (Konar & Singh (1979); Nawwar et al. (1985); O’Dowd et al. (1998)). It has been a natural source of alkaloids such as ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and other related compounds (Parsaeimehr et al. (2010). In addition to alkaloids, Ephedra is a source of phenolic compounds and therefore possesses a high antioxidant capacity (Eberhardt et al. (2000)). Ephedra has been reported to contain various phenolic compounds, such as trans-cinnamic acid, catechin, syringin, epicatechin, symplocoside, kaempferol 3-O-rhamnoside 7-O-glucoside, isovitexin 2-O-rhamnoside, which contribute significantly to the antioxidant activity of the plant (Amakura et al. (2013)). Phenolic compounds are plant secondary metabolites, which play important roles in disease resistance, and protection against pests (Servili & Montedoro G. (2002)). Phenolic compounds are also believed to play an essential role as a health protecting factor. Scientific evidence suggests that utilizing diets rich in antioxidants reduce the risk of chronic diseases including cancer and heart malfunction (Prakash et al. (2011)). The main characteristic of antioxidant compounds is their ability to scavenge free radicals such as peroxide, hydroperoxide or lipid peroxyl and thus inhibit the oxidative mechanisms that lead to degenerative diseases ((Prakash et al. (2011)).

To date, the scientific literature does not report about the antioxidant activity and phenolic content or flavonoid content of any type of Ephedra plant from Palestine. Therefore, a study of the Palestinian Ephedra Alata constitutes a valuable addition to the available literature. Abundant literature dealing with total phenolic and flavonoids content as well as antioxidant activity came out of different countries including those of the Middle East. In Iran, for example, Rustaiyan et al (2011) has determined TPC and AA (FRAP and DPPH assays) of methanolic extracts of Ephedra Lristanica and Ephedra Sarcocarpa (Rustaiyan et al. (2011). Three different Ephedra species growing in Iran, namely, Ephedra strobiliacea, Ephedra procera, and Ephedra pachyclada were also investigated for TPC and AA (Parsaeimehr et al. (2010)). Moreover, Dehkordi et al. (2015) has also determined TPC, and AA of ethanolic extract of Ephedra procera growing in Iran (Dehkordi et al. (2015). Harisaranraj et al. (2009) have determined TPC and TFC of Ephedra Vulgaris grown in India (Harisaranraj et al. (2009)). Alali et al. (2007) had determined TPC and AA of 95 plant species (including Ephedra alata Decne.) from Jordan and found that this plant is rich with phenolic compounds (Alali et al. (2007)). Kumar and Singh (2011) has determined AA of ethanol extracts from Trans Himalayan medicinal plants including one type of Ephedra (Ephedra gerardiana) in India (Kumar & Singh (2011)).

The objectives of the current investigation is to determine the AA, TPC and TFC of different extracts from Ephedra alata plant growing wild in Palestine, and to analyze their phenolic and flavonoid constituents by HPLC/PDA and HPLC/MS. Antioxidants contents were assayed using FRAP, CUPRAC, DPPH, and ABTS colorimetric methods. TPC and TFC of the extracts were evaluated using Folin-Ciocalteau, and aluminum chloride colorimetric methods, respectively. The correlations between antioxidant activity and total phenolic content or total flavonoid content were investigated. Additionally, correlations between the various antioxidant assays were performed. Finally, simultaneous chromatographic HPLC-PDA and LC-MS profiles using reversed phase columns were used to separate and disclose the identity of some active phenolic compounds.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Ephedra alata plant was collected from the southern part of the West Bank, Palestine in February 2015. The plant species is properly authenticated by Professor Khalid Sawalha, the director of biodiversity research laboratory, Al-Quds University. The plant was air-dried in the dark at room temperature for five days, then milled to a powdered plant material, and then stored in fridge until extraction.

Chemicals and Reagents

2,4,6-tripyridyl-S-triazine (TPTZ), hydrochloric acid 37% (w/w), sodium hydroxide, ferric chloride trihydrate, ferrous sulfate heptahydrate, potassium persulphate, sodium acetate, sodium carbonate, sodium nitrite, aluminum chloride, methanol, folin-ciocalteu reagent, Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid), gallic acid, cupper chloride, neocuproine, 99.9% ethanol, ammonium acetate, DPPH, methanol, ABTS (2,2-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzothialozine-sulphonic acid)), and potassium persulphate were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. All chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade. The acetonitrile and water were of an HPLC grade from Sigma. Phenolic and flavonoids standards: Vanillic acid, Ferulic acid, Syringic acid, trans-cinnamic acid, Catechin, p-coumaric acid, Sinapic acid, 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid, Rutin hydrate, Caffeic acid, Quercetin, Gallic acid, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, chlorogenic acid, Taxifolin, Luteolin 7-glucoside, Apigenin 7-glucoside, Luteolin, Quercetin 3-D-galactose were from Sigma.

FRAP reagent was prepared according to Benzie and Strain (1999) [15] by the addition of 2.5 mL of a 10 mM tripydyltriazine (TPTZ) solution in 40 mM HCl plus 2.5 mL of 20mM FeCl3.6H2O and 25 mL of 0.3M acetate buffer at pH 3.6. Acetate buffer (0.3M) was prepared by dissolving 16.8 g of acetic acid and 0.8g of sodium hydroxide in 1000 mL of distilled water.

Extraction of the Plant

Dry powder of plant material (five grams) was extracted separately with 50 ml of three extraction solvents (water, 80% ethanol, and 100% ethanol) in water bath at 37°C for three hours with and without sonication. The extracts were then filtered and the filtrate was evaporated using rotary evaporator at 40 °C and reduced pressure. The resulting crude viscous extracts were stored at 4°C until used for analysis (TPC, TFC, and AA) and HPLC analysis.

HPLC and UHPLC Instrumentation Systems

The analytical HPLC is Waters Alliance (e2695 separations module), equipped with 2998 Photo diode Array (PDA). Data acquisition and control were carried out using Empower 3 chromatography data software (Waters, Germany). The chromatography was performed under reverse phase conditions using a TSQ Quantum Access MAX (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) which includes a Dionex Pump with degasser module, an Accela PDA detector and an Accela Autosampler.

Chromatographic Conditions

The HPLC analytical experiments of the crude water, 80% ethanol and 100% ethanol extracts were run on ODS column of Waters (XBridge, 4.6 ID x 150 mm, 5 μm) with guard column of Xbridge ODS, 20 mm x 4.6mm ID, 5 μm. The mobile phase is a mixture of 0.5% acetic acid solution (A) and acetonitrile (B) ran in a linear gradient mode. The start was a 100% (A) that descended to 70% (A) in 40 minutes. Then to 40% (A) in 20 minutes and finally to 10% (A) in 2 minutes and stayed there for 6 minutes and then back to the initial conditions in 2 minutes. The HPLC system was equilibrated for 5 minutes with the initial acidic water mobile phase (100 % A) before injecting next sample. All the samples were filtered with a 0.45 μm PTFE filter. The PDA wavelengths range was from 210-500 nm. The flow rate was 1 ml/min. Injection volume was 20 μl and the column temperature was set at 25°C. The HPLC system was then equilibrated for 5 minutes with the initial mobile phase composition prior injecting the next sample. All the samples were filtered via 0.45 μm micro porous disposable filter.

The UHPLC chromatographic separations were performed on a Kinetex™ (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) column (C8, 2.6 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size, 100 x 2.1 mm), protected by a UHPLC SecurityGuard™ (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) cartridge (C8, for 2.1 mm ID column). The injection volume was 10 μL, the oven temperature was maintained at 35°C. The chromatographic separation was achieved using the same HPLC linear gradient program using formic acid instead of acetic acid at a constant flow rate of 0.4 mL/min over a total run time of 70 min. The samples were detected by a TSQ Quantum Access Max mass spectrometer in positive ion mode using Electron Spray ionization (ESI) and full scan acquisition. Air was produced (SF 2 FF compressor, Atlas Copco, Belgium). Purified nitrogen was used as source and exhaust gases.

Samples of the crude extracts were prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/ml by dissolving 50 mg of crude extract in 10 ml of respective solvent (water, 80% ethanol, or 100% ethanol).

Measurement of Antioxidant Activity

FRAP Assay

The antioxidant activity of the extracts was determined using a modified method of the assay of ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) of Benzie and Strain (1999). Freshly prepared FRAP reagent (3.0 mL) was warmed at 37 C and mixed with 40 μl of the extract and the reaction mixtures were later incubated at 37 C. Absorbance at 593 nm was read with reference to a reagent blank containing distilled water which was also incubated at 37 C for up to 1 hour instead of 4 min, which was the original time applied in FRAP assay. Aqueous solutions of known Fe+2 concentrations in the range of 2-5 mM were used for calibration, and results were expressed as mmol Fe+2 /g.

Cupric Reducing Antioxidant Power (CUPRAC Assay)

The cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity of the extracts was determined according to the method of Apak et al. (2008). 100 μl of sample extract was mixed with 1ml each of 10 mM of cupper chloride solution, 7.5 mM of neocuproine alcoholic solution (99.9% ethanol), and 1 M (pH 7.0) of ammonium acetate buffer solution, and 1 ml of distilled water to make final volume 4.1 ml. After 30 min, the absorbance was recorded at 450 nm against the reagent blank. Standard curve was prepared using different concentrations of Trolox. The results were expressed as μmol Trolox/g.

Free Radical Scavenging Activity Using DPPH (DPPH Assay)

DPPH assay is based on the measurement of the scavenging ability of antioxidants towards the stable DPPH radical, and the procedure was done according to Brand-Williams et al. (1995). A 3.9 mL aliquot of a 0.0634 mM of DPPH solution in methanol (95%) was added to 100 μl of each extract. The mixture was vortexed for 5-10 sec. The change in the absorbance of the sample extract was measured at515 nm for 30 min till the absorbance reached a steady state. The percentage inhibition of DPPH of the test sample and known solutions of Trolox were calculated by the following formula:

Where A° is the absorbance of a solution of 100μl methanol 95% and 3.9 ml of DPPH at 515 nm, and A is the absorbance of the sample extract at 515 nm. Methanol (95%) was used as a blank. Standard curve was prepared using different concentrations of Trolox. The results were expressed as μmol Trolox/g.

Free Radical Scavenging Activity Using ABTS (ABTS Assay)

A modified procedure using ABTS (2, 2-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzothialozine-sulphonic acid)) as described by Pellegrini et al. (1999) was used. The ABTS stock solution (7 mM) was prepared through reaction of 7 mM ABTS and 2.45 mM of potassium persulphate as the oxidant agent. The working solution of ABTS+’ was obtained by diluting the stock solution in 99.9% ethanol to give an absorption of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. 200 μl sample extract was added to 1800 μΐ of ABTS+’ solution and absorbance readings at 734 nm were taken at 30 °C exactly 10 min after initial mixing (A). The percentage inhibition of ABTS+’of the test sample and known solutions of Trolox were calculated by the following formula:

Where A° is the absorbance of a solution of 200μl of distilled water and 1800μl of ABTS+’ at 734 nm, and A is the absorbance of the test sample at 734 nm. The calibration curve between % inhibition and known solutions of Trolox (50-1000μM) was then established. The radical-scavenging activity of the test samples was expressed as Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity TEAC μmol Trolox/g sample).

Total Phenolic Content (Folin-Ciocalteau Assay)

Total phenolics were determined using Folin-Ciocalteau reagents (Singleton & Rossi (1965)). Ephedra plant extracts or gallic acid standard (40 μl) were mixed with 1.8 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (prediluted 10-fold with distilled water) and allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 min, and then 1.2 mL of sodium bicarbonate (7.5%, w/v) was added to the mixture. After standing for 60 min at room temperature, absorbance was measured at 765 nm. Aqueous solutions of known gallic acid concentrations in the range of 10 - 500 mg/L were used for calibration. Results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/ g sample.

Total Flavonoid Content

The determination of total flavonoids was performed according to the colorimetric assay of Kim et al. (2003). Distilled water (4 mL) was added to 1 mL of the extract in a test tube. Then, 0.3 mL of 5% sodium nitrite solution was added, followed by 0.3 mL of 10% aluminum chloride solution. Test tubes were incubated at ambient temperature for 5 minutes, and then 2 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide were added to the mixture. Immediately, the volume of reaction mixture was made to 10 mL with distilled water. The mixture was thoroughly mixed using test tube shaker and the absorbance of the pink color developed was determined at 510 nm. Aqueous solutions of known catechin concentrations in the range of 50 - 100 mg/L were used for calibration and the results were expressed as mg catechin equivalents (CEQ)/ g sample.

Statistical Analysis

Three samples of Ephedra plant were independently analyzed and all of the determinations were carried out in triplicate. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA, Release 8.02, 2001). Comparisons of means with respect to the influence of extraction solvent on TPC, TFC, and AA were carried out using the GLM procedure, treating the main factor (extraction solvent) separately using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Bonferroni procedure was employed with multiple t-tests in order to maintain an experiment-wise of 5%.

Pearson correlations were calculated to test the relation between individual quality indicators with each one of the other quality indices. The NOMISS option was used in order to obtain results consistent with subsequent multiple regression studies.

Results and Discussion

Total Phenolic Contents (TPC)

TPC of Ephedra Alata plant extracts using three different solvents is shown in Table 1. As it is obvious from this table, the extraction solvent has an effect on the TPC of the ephedra extracts where significant differences (p < 0.05) between the TPC of the three extracts are indicated by different small letters (a, b, and c). The highest TPC was found for the plant material when extracted with 80% ethanol (101.2 ± 0.9 mg/g), followed by plant material extracted with 100% ethanol (40.9 ± 0.2 mg/g) and finally with water (30.9 ± 0.5 mg/g). These results show that TPC were only 40% and 30% when the plant material was extracted by 100% ethanol and distilled water respectively as compared with the TPC extracted with 80% ethanol indicating the higher solubility of the phenolic compounds in 80% ethanol.

Table 1.

Total phenolic content (TPC as mg Gallic acid/g DW*), total flavonoids contents (TFC as mg catechin/g DW), FRAP (mmol Fe+2/g DW), CUPRAC (μmol Trolox/g DW), DPPH (μmol Trolox/g DW), ABTS (μmol Trolox/g DW), DPPH % inhibition, and ABTS % inhibition of Ephedra Alata plant extracted with water, 80% ethanol, and 100% ethanol.

| TPC** (mg/g) | TFC (mg/g) | FRAP (mmol/g) | CUPRAC μmol/g) | DPPH (μmol/g) | ABTS (μmol/g) | DPPH % inhibition | ABTS % inhibition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 30.9c ± 0.5 | 4.2c ± 0.10 | 7.1c ± 0.1 | 2182c ± 25 | 305.7c ± 3.4 | 40.5c ± 1.0 | 88.7c ± 0.5 | 81.9c ± 0.6 |

| Ethanol (80 %) | 101.2a± 0.9 | 9.8b± 0.1 | 21.3a± 0.4 | 6442a± 52 | 482.5a± 1.7 | 66.0a± 1.5 | 95.3a± 0.6 | 91.0a± 0.6 |

| Ethanol (95 %) | 40.9b ± 0.2 | 19.5a ± 0.3 | 11.1b ± 0.2 | 3272b± 30 | 351.7b ± 1.2 | 47.5b ± 1.0 | 91.5b ± 0.6 | 87.0b ± 0.3 |

DW: Dry weight

Results are expressed as average of three samples of Ephedra Alata shoots. Different small letters within column indicate significant difference (p < 0.05, n = 3).

The results showed that Ephedra plant investigated in this study are richer with phenolic compounds (101.2 mg/g using the best extraction solvent) than that of Guava and Plum fruits reported earlier (1.26-2.47mg/g in guava, 1.25-3.73 mg/g in plums) (Thaipong et al. (2006)). As plant phenolics have multifunctional properties and can act as singlet oxygen quenchers and scavenge free radicals, the presence of substantial amounts of these compounds in Palestinian Ephedra promotes the latter as an important source of antioxidants which if properly consumed may reduce risk associated with degenerative diseases and provide health promoting advantage.

It is interesting to compare TPC of Palestinian Ephedra with Ephedra from other countries. For example, Ephedra alata Decne from Jordan was analyzed for TPC and was found to have 16.2 and 11.9 mg GA/g for aqueous and methanolic extracts, respectively which is lower than TPC of Ephedra Alata investigated in this study. Results of a study of Ghasemi et al. (2013) indicated that total phenolic content in the extract of Ephedra pachyclada collected from Iran was 45 mg of GAE/g dry weight (Ghasemi Pirbalouti et al. (2013)).

Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The results of ferric chloride colorimetric test for determining flavonoids content are presented in Table 1. The same statistical analyses as for TPC were performed for total flavonoids content (TFC), and the results (Table 1) showed that significant differences between total flavonoids content of the plant materials extracted with the three solvents were obtained, where significant differences (p < 0.05) indicated by small letters (a, b, and c). The highest TFC was found for the plant material when extracted with 100% ethanol (19.5 ±0.4 mg/g) which is two times significantly higher than that extracted with 80% ethanol (9.8 ±0.1 mg/g) and the later was two times significantly higher than the TFC extracted with water (4.2 ±0.1 mg/g). Comparing the trend of solvent effect on TFC and TPC, there is a difference in the two trends where the highest content of TPC was obtained when the plant was extracted with 80% ethanol while the TFC was obtained when the plant material was extracted with 100% ethanol. This can be attributed to the polarity of the extraction solvent and the flavonoids, where flavonoids need less polar solvent (or higher amount of ethanol e.g. 100% ethanol). Apparently, mixed solvents of intermediate polarities (100% or 80% ethanol) are the most suitable extracting solvents for recovering the highest amounts of phenolic and flavonoid compounds which have both polar and nonpolar functional groups.

These results demonstrated that the Ephedra plant extracts are rich with flavonoids (range: 4.2-19.5 mg/g). Comparing TFC of Ephedra plant analyzed in this study with Ephedra from other countries revealed that the Ephedra grown in Palestine is richer with flavonoids, for example according to the study of Harisaranraj et al. (2009) of Ephedra vulgaris from India, total flavonoids was found to be 1.48±0.20 mg/100 g (Harisaranraj et al. (2009)).

Antioxidant Activity (AA)

Evaluation of AA is becoming increasingly relevant in the field of nutrition as it provides useful information with regard to health promoting and functional quality of raw materials whether they are fruits, vegetables, or medicinal plants (Scalfi et al. (2000). This parameter accounts for the presence of efficient oxygen radical scavengers, such as phenolic compounds. The antioxidant activity of phenolics is mainly due to their redox properties, which make them acting as reducing agents, hydrogen donors, and singlet oxygen quenchers.

There are two types of antioxidant assays used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of plant extracts. The first category measures the potential of plant extracts to reduce ions or oxidants (to act as reducing agents) like ferric ion, cupric ion. The main two assays of this antioxidant activity category are FRAP (measures the reduction potential of ferric to ferrousion), and CUPRAC (measures the reduction of cupric to cuprous ion). The second category of antioxidant activity measures the ability of plant extracts to scavenge free radicals. DPPH and ABTS assays (where DPPH and ABTS are stable free radicals) are the two main examples of this category. These assays are used because they are quick and simple to perform, and reaction is reproducible and linearly related to the molar concentration of the antioxidant(s) present.

Reducing Potential of Plant Extracts

FRAP assay

FRAP assay measures the reducing potential of an antioxidant reacting with a ferric tripyridyltriazine (Fe3+- TPTZ) complex and producing a colored ferrous tripyridyltriazine (Fe2+-TPTZ). The reducing properties are associated with the presence of compounds which exert their action by breaking the free radical chain by donating a hydrogen atom. The reduction of Fe3+-TPTZ complex to blue-colored Fe2+-TPTZ occurs at low pH.

The antioxidant test based on FRAP assay of Ephedra plant extracts using three different solvents are presented in Table 1 (expressed as mmol Fe+2/g of dry plant material). Statistical analyses showed that there are significant differences between total flavonoids content as a function of extraction solvent (Table 1), where significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated by different small letters (a, b, and c).

Table 1 revealed that antioxidant activity (FRAP) of the Ephedra plant increased as the polarity of solvent changes (80% ethanol > 100% ethanol > water), where FRAP values were found to be about two and three times significantly higher when extracted with 80% ethanol compared to 100% ethanol and water, respectively.

The trend of extraction solvent on the FRAP values was found to be the same as for TPC but different from TFC. This suggest that there is a correlation between AA (expressed as FRAP) and TPC, reflecting the fact that total phenolics are the major determinant of AA. Pearson correlation revealed that FRAP (as well as other antioxidant activities under study) were highly and significantly correlated to TPC but were not correlated with TFC, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Pearson coefficients between quality indices (TPC, TFC, FRAP, CUPRAC, and DPPH)

| TPC (mg/g) | TFC (mg/g) | FRAP (mmol/g) | CUPRAC (μmol/g) | DPPH (μmol/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC (mg/g) TFC (mg/g) FRAP (mmol/g) | -0.022 0.989*** | 0.1269 | |||

| CUPRAC (μmol/g) | 0.993*** | 0.0937 | 0.999*** | ||

| DPPH (μmol/g) | 0.992*** | 0.0984 | 0.999*** | 0.999*** | |

| ABTS (pmol/g) | 0.989*** | 0.125 | 0.999*** | 0.999*** | 0.999*** |

Significance indicated as

for p < 0.05,

for p < 0.01, and

for p < 0.001, n = 9.

As in the case of TPC and TFC, ethanol (100% or 80%) gives higher amounts of AA (FRAP) compared with water as extraction solvent of Ephedra plant.

CUPRAC Assay

Although FRAP antioxidant assay has been very popular among researchers, CUPRAC assay is a relatively new assay developed by Apak et al. (2008). It utilizes the copper(II)-neocuproine [Cu(II)-Nc] reagent as the chromogenic oxidizing agent and is based on the cupric reducing ability of reducing compounds to cuprous.

Table 1 shows the CUPRAC antioxidant activity (expressed as μmole Trolox/g) of Ephedra plant extracts using three different solvents. Statistical analyses showed that there are significant differences between AA using the three extraction solvents, where significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated by different small letters (a, b, and c).

Results showed that CUPRAC antioxidant activity of the Ephedra plant increased in the following order: 80% ethanol > 100% ethanol > water which is the same trend as FRAP antioxidant activity, and TPC but different from TFC, which suggests that there is a correlation between CUPRAC AA and TPC. Pearson correlation confirms the correlation between CUPRAC antioxidant activity and total phenolic content but no correlation with total flavonoids content (TFC), see Table 2.

Free Radical Scavenging Ability of Plant Extracts

DPPH Assay

DPPH is a free radical compound and has been widely used to test the free radical scavenging ability of various samples (Sakanaka et al. (2005)). It is a stable free radical with a characteristic absorption at 517 nm that was used to study the radical-scavenging effects of extracts. As antioxidants donate protons to this radical, the absorption decreases. Antioxidants, on interaction with DPPH, either transfer an electron or hydrogen atom to DPPH, thus neutralizing its free radical character (Naik et al. (2003)). The color changed from purple to yellow and the absorbance at wavelength 517 nm decreased.

DPPH assay is based on the ability of the stable free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl to react with hydrogen donors including phenolics. The bleaching of DPPH solution increases linearly with increasing amount of extract in a given volume.

Table 1 shows the % inhibition of DPPH free radicals by the Ephedra plant extracted with the three solvents. Statistical analyses showed that there are significant differences between % inhibitions using the three extraction solvents, where significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated by different small letters (a, b, and c), see table 1.

Table 3 shows the % inhibition of DPPH at different concentrations of the crude extract (from 10 to 150 μg/mL). This data shows that the extracts exhibited a dose dependent scavenging activity (a linear relationship between % of DPPH inhibition and concentration (y = 0.594x + 2.216, with R2 of 0.997), where y is the % of inhibition and x is the concentration). From this linear relationship, IC50 which is the concentration required to quench 50% of the DPPH free radicals was determined and was found to be 78 μg/mL.

Table 3.

% inhibition of DPPH and ABTS free radicals by different concentrations of Ephedra Alata plant extract.

| Concentration of DPPH μg/mL) | % inhibition of DPPH * | Concentration of ABTS μg/mL) | % inhibition of ABTS * |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 10 | 9.2 ± 0.3 |

| 20 | 13.6 ± 1.2 | 20 | 18.9 ± 0.7 |

| 40 | 26.2 ± 1.0 | 40 | 37.1 ± 0.9 |

| 80 | 53.6 ± 1.4 | 80 | 66.0 ± 1.1 |

| 150 | 94 ± 2.1 | 100 | 88.4 ± 1.5 |

Results are expressed as Average ± standard deviation of three samples.

DPPH antioxidant activity of Ephedra plant extracts using three different solvents was expressed as μmole Trolox/g (Table 1). Statistical analyses showed that there are significant differences between AA using the three extraction solvents, where significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated by different small letters (a, b, and c).

Results showed that DPPH antioxidant activity of the Ephedra plant increased in the following order: 80% ethanol > 100% ethanol > water which is the same trend as TPC, FRAP, and CUPRAC antioxidant activity. Correlation studies showed a significant correlation between DPPH and TPC but not with TFC (Table 2).

ABTS Assay

The ABTS assay measures the relative antioxidant ability of extracts to scavenge the radical-cation ABTS+ produced by the oxidation of 2,2’-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonate.

Table 1 shows the % inhibition of ABTS free radicals by the plant extracted with the three solvents. Statistical analyses showed that there are significant differences between AA using the three extraction solvents, where significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated by different small letters (a, b, and c), see Table 1.

Table 3 shows the % inhibition of ABTS at different concentrations of the crude extract (from 10 to 100 μg/mL). This data shows that the extracts showed a dose dependent scavenging activity (a linear relationship between % of ABTS inhibition and concentration (y = 0.849x + 1.47, with R2 of 0.995), where y is the % of inhibition and x is the concentration). From this linear relationship, IC50 was determined and was found to be about 57 μg/mL.

ABTS antioxidant activity of Ephedra plant extracts using three different solvents was expressed as μmol Trolox/g (Table 1). Statistical analyses showed that there are significant differences between AA using the three extraction solvents, where significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated by different small letters (a, b, and c).

Results showed that ABTS antioxidant activity of the Ephedra plant increased in the following order: 80% ethanol > 100% ethanol > water which is the same trend as FRAP, CUPRAC, and DPPH antioxidant activities. Additionally, this trend is the same as TPC but different from TFC, which suggests that there is a correlation between ABTS and TPC. As it is obvious from table 2, there is a correlation between ABTS and TPC but not with TFC.

It is interesting to compare AA (ABTS) of Palestinian Ephedra with Ephedra from other countries. For example, Ephedra alata Decne from Jordan was analyzed for ABTS and was found to have 46.6 and 60.2 μmol Trolox/ g DW for aqueous and methanolic extracts, respectively which is comparable to Ephedra investigated in this study.

Pearson Correlation Analyses

A correlation between antioxidant activity (each of FRAP, CUPRAC, DPPH, and ABTS) and total phenolic content or total flavonoid content, as well as between total phenolic content and total flavonoid content was performed (table 2). Additionally, correlations between the four antioxidant assays (FRAP, CUPRAC, DPPH, and ABTS) were also performed (table 2).

Pearson correlation revealed that all antioxidant activities under study were highly and significantly correlated to TPC but were not correlated with TFC. All antioxidant activities were also highly and significantly correlated with each other.

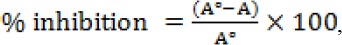

HPLC-PDA Profiles of Ephedra Alata Extracts

To enrich the active ingredients present in Ephedra alata, two extractions methods were adopted and the extract components were directly examined on HPLC-PDA at different wavelengths. The first extract method is based on soaking the stems of Ephedra alata separately in water, 80% ethanol and in 100% ethanol. The second technique however utilized sonication of the same weight of the herb stems using the same solvent volume for three hours. Eighteen phenolic and flavonoid standards mixture were injected and separated simultaneously to identify the presence of any of these compounds in the crude extracts. Calibration curve of each individual standard was also prepared at three concentration levels namely 50, 100 and 250 ppm. It was noticed that extraction by sonication is much more efficient in comparison to typical infusion procedure (Figure 1).

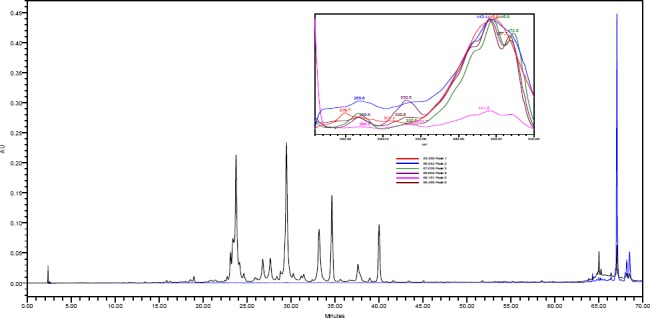

Figure 1.

Overlaid HPLC-PDA chromatograms of crude 100% ethanol Ephedra alata extract using infusion (red) and sonication (blue) methods at 350 nm.

Moreover, the solvents extraction power using sonication was in the order of 100% ethanol, 80% ethanol and water respectively. Figure 2 showed overlaid chromatograms of the three crude extracts at 350 nm. This wavelength was selected since the main Ephedra alata peaks showed a maximum absorption close to it.

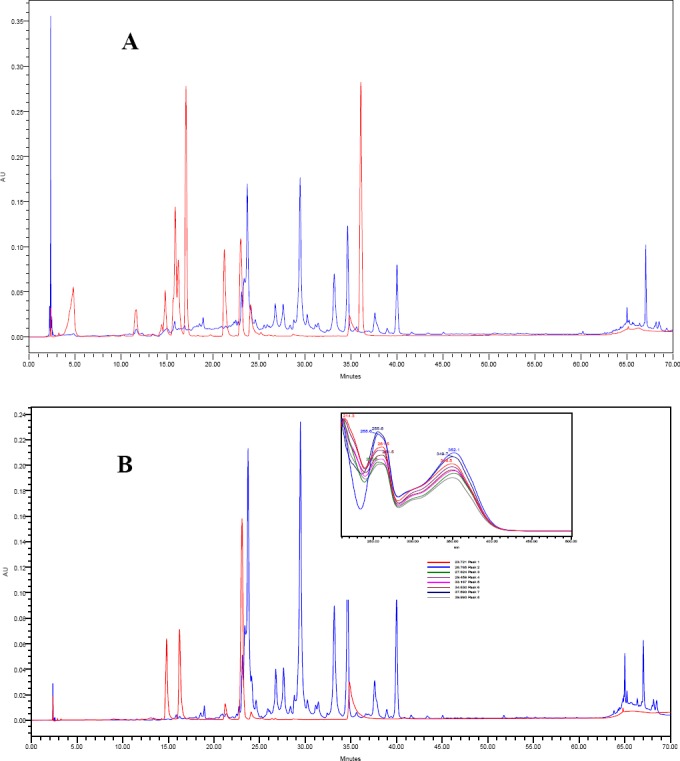

Figure 2.

Overlaid HPLC-PDA chromatograms of crude water (blue), 80% ethanol (green) and 100% ethanol (red) extracts of Ephedra alata at 350 nm. The overlaid UV-Vis spectra of the main peaks are depicted at the right corner.

When the monitoring wavelength was set at two channels of 442 nm or 472 nm, the 100% ethanol extract showed few lipophilic peaks that eluted late between 64-68 minutes. These peaks were less pronounced in 80% ethanol and did not exist in the water extract (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overlaid HPLC-PDA chromatograms of Ephedra alata crude 100% ethanol at 350 nm (black) and 472 nm (blue). The overlaid UV-Vis spectra of the main peaks eluted later between 64-68 minutes are depicted at the right corner.

Figure 4 portrays the phenolic and flavonoids standards mixture and Ephera alata 100% ethanol extract at two channels of 272 nm (A) and 350 nm (B) respectively.

Figure 4.

Figure 4 Overlaid chromatograms of phenolic and flavonoids standards mixture and 100% ethanol extract of Ephera alata at 272 nm (A) and 350 nm (B) respectively. The overlaid UV-Vis spectra of the main peaks are depicted at the right corner of chromatogram (B).

As in figure 4, most of the compounds seen in the 100% ethanol extract does not match any of the standards injected as seen from their retention and UV-Vis spectra. However, almost all the main peaks shared maximum wavelengths of 348.5 nm-352.1 nm. These types of compounds are very close to isomeric flavonoid glycosides.

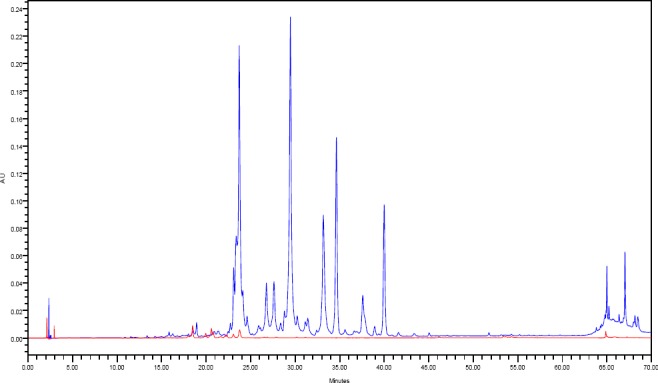

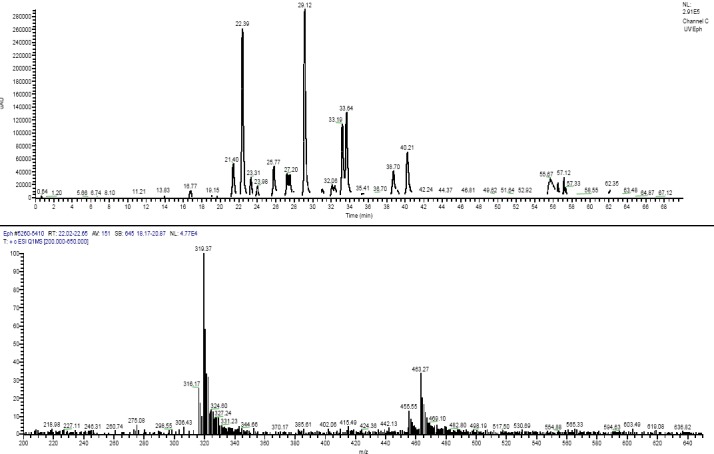

The full scanned LC-MS using the positive and negative electrospray ionization modes revealed the presence of Luteolin-7-O-glucuronide flavonoid (molecular ion [M+H]+ at m/z of 463.27 Da) at 22.39 minutes with a fragment ion at 319.37 Da signifying to the myricetin antioxidant skeleton (figure 5). The peak at 23.98 minutes showed a deprotonated molecular ion [M-H]- of 463.22 Da presumably indicating Myricetin 3-rhamnoside existence. Other major peaks appeared at retention of 29.12 minutes showed molecular ion [M-H]- at m/z of 505.33 Da. Ranged peaks from 33.19 to 33.64 minutes showed peaks at 557.73, 533.26 and 477.30 Da suggesting flavonoid-like structures with myricetin fragment backbone. Another peak at a retention time of 40.21 minutes showed a deprotonated peak molecular ion [M-H]- at 519.38 Da. The UHPLC-MS spectra for the latter few compounds were not sufficient to be deconvoluted. However, preparative HPLC collection of pure flavonoids from Ephedra plant along with NMR experiments would assist in the exact determination of their structure.

Figure 5.

UHPLC of the Ephedra alata ethanol extract (A) and the (+)-ESI mass spectrum of Luteolin-7-Oglucuronide flavonoid.

It is evident that all the major peaks showed a fragment at m/z of 319 Da which indicates that the isomeric flavonoids shared myricetin polyphenolic flavonoid compound which is known for its antioxidant and anticancer activities.

Conclusions

The antioxidant activities, total phenolics content and total flavonoids content of Ephedra alata grown in Palestine were determined and presented. Analysis of phenolics and flavonoids of the extracts by HPLC/PDA and HPLC/MS were also performed. The antioxidant activity was measured using four different assays (FRAP, CUPRAC, DPPH, and ABTS), while total phenolic content and total flavonoid content of the extracts were measured using Folin Ciocalteau and aluminum chloride colorimetric methods, respectively. The results showed that the Ephedra alata grown in Palestine is rich in antioxidants, phenolics and flavonoids. Their antioxidant activity is comparable or higher to that of Epheda of other countries. There is a correlation between antioxidant activities and total phenolic content but not with total flavonoids content. The four antioxidant activity assays were highly and significantly correlated with each other.

List of Abbreviations and nomenclature: TPC: Total phenolic content, TFC: Total flavonoid content, AA: antioxidant activity, HPLC: High Performance Liquid Chromatography, CUPRAC: Cupric reducing antioxidant power, DPPH: Free radical scavenging activity using DPPH, ABTS: Free radical scavenging activity using ABTS, FRAP: Ferric reducing/antioxidant power

References

- 1.Alali FQ, Tawaha K, El-Elimat T, Syouf M, El-Fayad M, Abulaila K, Nielsen SJ, Wheaton WD, Falkinham J. O, III, Oberlies NH. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of aqueous and methanolic extracts of Jordanian plants: an ICBG project’. Natural Product Research. 2007;21:1121–1131. doi: 10.1080/14786410701590285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amakura Y, Yoshimura M, Yamakami S, Yoshida T, Wakana D, Hyuga M, Hyuga S, Hanawa T, Goda Y. Characterization of Phenolic Constituents from Ephedra Herb Extract. Molecules. 2013;18:5326–5334. doi: 10.3390/molecules18055326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apak R, Guclu K, Ozyurek M, Celik SE. Mechanism of antioxidant capacity assays and the CUPRAC (cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity) assay. Microchim. Acta. 2008;160:413–419. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benzie IF.F, Strain JJ. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: Direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Methods In Enzymology. 1999;299:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehkordi NV, Kachouie MA, Pirbalouti AG, Malekpoor F, Rabei M. Total phenolic content, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of the extract of ephedra procera fisch. et mey. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica Drug Research. 2015;72:341–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhardt MV, Lee C.Y, Liu RH. Antioxidant activity of fresh apples. Nature. 2000;405:903–904. doi: 10.1038/35016151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghasemi Pirbalouti A, Azizi S, Amirmohammadi M, Craker L. Healing effect of hydro-alcoholic extract of Ephedra pachyclada Boiss. in experimental gastric ulcer in rat. Acta Pol. Pharm. Drug Res. 2013;70:1003–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harisaranraj R, Suresh K, Saravanababu S. Evaluation of the Chemical Composition Rauwolfia serpentina and Ephedra vulgaris. Advances in Biological Research. 2009;3:174–178. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DO, Jeong SW, Lee CY. Antioxidant capacity of phenolic phytochemicals from various cultivars of plums. Food Chemistry. 2003;81:321–326. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konar RN, Singh MN. Production of plantlets from female gametophytes of Ephedra foliate Boiss. Z. Pflanzenphysiol. 1979;95:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar GP, Singh SB. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of ethanol extracts from Tran Himalayan medicinal plants. European Journal of Applied Sciences. 2011;3:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naik GH, Priyadarsini KI, Satav JG, Banavalikar MM, Sohoni PP, Biyani MK. Comparative antioxidant activity of individual herbal components used in Ayurvedic medicine. J. Phytochem. 2003;63:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nawwar MAM, Barakat HH, Buddrust J, Linscheidt M. Alkaloidal, lignan and phenolic constituents of Ephedra alata. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:878–879. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Dowd NA, McCauley G, Wilson JAN, Parnell TAK, Kavanaugh D. In vitro culture, micropropagation and the production of ephedrine and other alkaloids. In: Bajaj YPS, editor. Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 1998. p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsaeimehr A, Sargsyan E, Javidnia K. A Comparative Study of the Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antioxidant Activity and Total Content of Phenolic Compounds of Cell Cultures and Wild Plants of Three Endemic Species of Ephedra. Molecules. 2010;15:1668–1678. doi: 10.3390/molecules15031668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prakash A, Rigelhof F, MIller E. Antioxidant Activity. 2011 Available from World Wide Web: http://www.medlabs.com/downloads/antiox_acti_.pdf .

- 18.Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rustaiyan A, Javidnia K, Farjam MH, Aboee-Mehrizi F, Ezzatzadeh E. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of the Ephedra sarcocarpa growing in Iran. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5:4251–4255. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rustaiyan A, Javidnia K, Farjam MH, Mohammadi MK, Mohammadi N. Total phenols, antioxidant potential and antimicrobial activity of the methanolic extracts of Ephedra laristanica. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5:5713–5717. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakanaka S, Tachibana Y, Okada Y. Preparation and antioxidant properties of extracts of Japanese persimmon leaf tea (kakinoha-cha) J. Food Chem. 2005;89:569–575. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scalfi L, Fogliano V, Pentagelo A, Graziani G, Giordano I, Ritieni A. Antioxidant activity and general fruit characteristics in different ecotypes of Corbarini small tomatoes. J. Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:1363–1366. doi: 10.1021/jf990883h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Servili M, Montedoro G. Contribution of phenolic compounds in virgin olive oil quality. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 2002;104:602–613. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thaipong K, Boonprakob U, Crosby K, Cisneros-Zevallos L, Hawkins Byrne D. Comparison of ABTS DPPH, FRAP and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava fruit extracts. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2006;19:669–675. [Google Scholar]