Abstract

Background

The role of axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) has increasingly been called into question among patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes. Two recent trials have failed to show a survival difference in sentinel node-positive breast cancer patients who were randomized either to undergo completion ALND or not. Neither of the trials, however, included breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy or those with tumors larger than 5 cm, and power was debatable to show a small survival difference.

Methods

The prospective randomized SENOMAC trial includes clinically node-negative breast cancer patients with up to two macrometastases in their sentinel lymph node biopsy. Patients with T1-T3 tumors are eligible as well as patients prior to systemic neoadjuvant therapy. Both breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy, with or without breast reconstruction, are eligible interventions. Patients are randomized 1:1 to either undergo completion ALND or not by a web-based randomization tool. This trial is designed as a non-inferiority study with breast cancer-specific survival at 5 years as the primary endpoint. Target accrual is 3500 patients to achieve 80% power in being able to detect a potential 2.5% deterioration of the breast cancer-specific 5-year survival rate. Follow-up is by annual clinical examination and mammography during 5 years, and additional controls after 10 and 15 years. Secondary endpoints such as arm morbidity and health-related quality of life are measured by questionnaires at 1, 3 and 5 years.

Discussion

Several large subgroups of breast cancer patients, such as patients undergoing mastectomy or those with larger tumors, have not been included in key trials; however, the use of ALND is being questioned even in these groups without the support of high-quality evidence. Therefore, the SENOMAC Trial will investigate the need of completion ALND in case of limited spread to the sentinel lymph nodes not only in patients undergoing any breast surgery, but also in neoadjuvantly treated patients and patients with larger tumors.

Trial registration

NCT 02240472, retrospective registration date September 14, 2015 after trial initiation on January 31, 2015.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Sentinel lymph node biopsy, Axillary lymph node dissection, Survival, Macrometastasis

Background

Lymph node metastasis is one of the factors of greatest prognostic importance in breast cancer [1–3]. Lymph node metastases are classified as isolated tumor cells (≤ 0.2 mm and/or <200 cells), micrometastasis (> 0.2 but ≤2 mm and/or >200 cells) and macrometastasis (> 2 mm) [4]. Sentinel node (SN) biopsy has proven to be a reliable method [5], and several follow-up studies have shown that it is safe to refrain from completion axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in sentinel node-negative breast cancer [6–10]. The greatest advantage of the SN biopsy approach is the significant decrease in the frequency and severity of arm problems since fewer lymph nodes are removed from the axilla [11–14].

In SN-positive patients, no additional metastases are found in the remaining lymph nodes removed on ALND in about 50–65% of patients [15]. After the publication of the ACOSOG Z0011 trial in 2011 [16], refraining from completion ALND in SN-positive cases has been embraced widely especially in the US [17, 18]. This trial randomized SN-positive patients to either undergo ALND or to refrain from completion axillary surgery. After a median follow-up period of over 6 years, no difference in the rate of axillary recurrence was found, and survival was even slightly better among patients who only underwent SN biopsy (disease-free survival 83.9%, compared with 82.2% for patients who underwent ALND), although the difference was not statistically significant. The study has received some criticism [19, 20]. ACOSOG Z0011 only included patients with tumors up to 5 cm in size who underwent breast-conserving surgery, receiving whole-breast postoperative radiotherapy.

Another study (IBCSG 23–01), in which SN-positive patients were randomized to either undergo completion ALND or not, was published in 2013 [21]. This study included only patients with SN micrometastases, but also showed slightly better disease-free survival in the group operated with SN biopsy alone (87.8% compared with 84.4% for those who underwent ALND), though the difference was not statistically significant here either. Neither the ACOSOG Z0011 study nor the IBCSG 23–01 study succeeded in enrolling the planned number of patients and the studies do not have sufficiently high power to detect small differences.

There are a few studies suggesting that ALND may still have some therapeutic benefit: The rate of axillary recurrence among SN-positive patients who did not undergo ALND was a striking 2.0% after just 30 months, despite otherwise favorable prognostic factors (compared with 0.4% among those who underwent completion ALND) in a report by Park et al. [22]. In the Dutch MIRROR study [23] the rate of axillary recurrence was more than twice as high among patients with SN micrometastases who did not undergo ALND compared with SN-negative patients.

In Sweden, most patients with SN macrometastases receive adjuvant radiotherapy to the axillary region. A large European study (AMAROS) randomizing over 1400 SN-positive patients, of whom 861 with SN-macrometastases, to either undergo completion ALND or to have axillary radiotherapy showed no difference in disease-free or overall survival [24]. Subsequently, several countries now approve axillary radiotherapy in lieu of axillary lymph node dissection.

None of the described trials included a sufficient amount of patients treated by mastectomy to draw any conclusions on the need of ALND. It is also unclear whether the tumor size should be limited to 5 cm at most or whether larger, although not locally advanced tumors may be included along the same line of thought. Finally, as the rates of breast cancer treated by neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NAST) are rising internationally, the question how to surgically treat the axilla post NAST in the event of a positive pre-NAST SN biopsy needs to be answered. The SENOMAC trial attempts to answer these highly important questions in an international collaborative effort.

Methods

This prospective multicenter non-inferiority trial randomizes breast cancer patients with macrometastasis in at most two sentinel nodes to either undergo completion ALND (arm A) or not to have any further axillary surgery (arm B), and is conducted according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. For inclusion and exclusion criteria, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria according to the SENOMAC study protocol

| Inclusion criteria | Primary invasive breast cancer T1-T3a |

| Preoperative ultrasound of the axilla performed | |

| Macrometastasis in not more than two lymph nodes at sentinel node biopsy | |

| Written informed consent | |

| Age 18 years or older | |

| Exclusion criteria | Palpable regional lymph node metastasis prior to surgery |

| Regional or distant metastases outside of the ipsilateral axilla | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Bilateral invasive breast cancer, if one side meets any exclusion criteria | |

| Medical contraindication for radiotherapy or systemic treatment | |

| Inability to absorb or understand the meaning of the study information; for example, through disability, inadequate language skills or dementia | |

| Prior history of invasive breast cancer |

aAccording to the TNM classification system

Aims and endpoints

The main aim of this study is to evaluate whether it is safe to refrain from completion ALND in individuals with breast cancer and SN macrometastasis. Primary endpoint is breast cancer-specific survival at 5 years. Secondary endpoints are locoregional recurrence, disease-free survival and overall survival, but also arm morbidity, health economic outcome and health-related quality of life.

Preoperative assessment

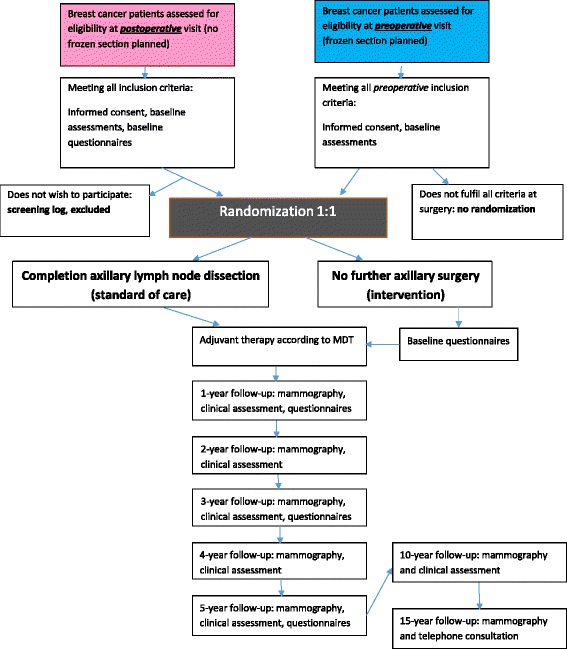

Preoperative assessment is carried out in accordance with local practice with triple diagnostics, namely clinical assessment, imaging evaluation and cytological or histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis. Ultrasound of the axillary region is required and suspicious nodes must be biopsied. Patients with up to two non-palpable preoperatively diagnosed axillary metastases may nevertheless undergo SN biopsy and be included. All types of breast surgery are eligible in this trial. Frozen section may be performed or omitted in the study which warrants different logistic considerations, see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of inclusion pathways in the SENOMAC Trial depending on the use of frozen section at sentinel node biopsy

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy

Patients planned for neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NAST) may be included in this trial in case all inclusion criteria are met. Thus, patients without palpable lymph node metastases may undergo SN biopsy prior to start of their neoadjuvant treatment. Eligible patients may be randomized and included in this trial. Randomization is recommended to be performed before start of neoadjuvant therapy but must at the very latest take place before the first clinical or radiological response evaluation. In case of tumor progression during NAST and/or the appearance of palpable lymph node metastases, participation in the trial is discontinued and the reason for study termination recorded in the electronic Case Report Form (eCRF). The decision to discontinue participation in the trial should always be discussed at a multidisciplinary team conference.

Randomization

Web-based randomization may occur either after the receipt of the frozen section results during surgery or after receipt of the final histopathological results postoperatively. Patients randomized to arm A will undergo completion ALND of levels I and II, which may be performed either at the same session (when randomization is based on frozen section results) or in a second session. Patients randomized to arm B will not undergo further axillary surgery.

Randomization is based on permutated block technique and performed 1:1; treatment arms are stratified per country. In the event that the final histopathology results show that a randomized patient does not meet all criteria (e.g., additional metastasis identified during SN sectioning), the patient must be excluded. Patients who fulfil all inclusion criteria and receive information about the trial but are not randomized are to be registered in screening logs on site.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires regarding arm morbidity, health-related quality of life and health economy will be provided at baseline as well as after 1, 3 and 5 years. The instruments used are the Lymphedema Functioning, Disability and Health Questionnaire (Lymph-ICF) [25], the EQ-5D-5 L utility scores [26], and EORTC’s well-validated QLQ-30 [27, 28] and BR-23 [29] questionnaires. Apart from the traditional paper version, online versions of all instruments will be made available. Answers are coded with an individual study code and collected centrally at the Study Center in Stockholm.

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant systemic therapy should be given in accordance with national clinical guidelines of each participating country. After breast-conserving surgery, the remaining ipsilateral breast parenchyma must be irradiated. Boost to the tumor bed should be applied according to each country’s national guidelines. Post-mastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT) and radiotherapy to the regional lymph node basins are based on each country’s national guidelines. It is, however, mandatory, that for those participating in this trial, radiotherapy should not be extended or changed based on which arm the patient is randomized to, ie, sentinel node biopsy only should be regarded as a substitute for axillary clearance.

In Sweden, radiotherapy to regional lymph node basins follows the recommendations of the Swedish National Guidelines. The regional lymph node target (CTV) is composed of axilla level 2 and 3, interpectoral lymph nodes and supraclavicular fossa (i.e. axilla level 4) which means that level 1 is omitted from the regional lymph node CTV. For detailed volume description, please see the target definition at ESTRO consensus guideline on target volume delineation for elective radiation therapy of early stage breast cancer, version 1.1. [30].

The exact regional lymph node target is to be reported in the eCRF prospectively throughout the trial. Irradiation of internal mammary nodes (IMN) should be handled according to national guidelines of each country and treatment of IMN must be recorded in the eCRF.

Fractionation schedule is chosen according to local practice, i.e. 2 Gy/f × 25 over 33–35 days to the breast and regional lymph nodes. A slightly lower total dose to the nodes (~46 Gy) is accepted. Hypofractionated radiotherapy can be chosen, i.e. 2.67 Gy/f × 15–16 over 19–22 days. Dose and fractionation is to be reported prospectively.

Data management

All data are registered using an electronic Case Report Form (eCRF). Monitoring is performed according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. In the eCRF, data on age, completed surgery, tumor and lymph node characteristics, as well as neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy are collected, as well as status at annual follow-up. Data are managed by the Clinical Trial Unit at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden.

Monitoring and follow-up

Patients will be followed by annual clinical examination and mammography for 5 years.

Each follow-up visit must take place within +/− 2 months from the randomization date, and data are to be completed in the eCRF within 1 month from the follow-up visit. Additional diagnostic measures, e.g. axillary ultrasound, biopsies or other investigations, are carried out according to clinical findings. In case of suspected axillary recurrence, a CT of the thoracic region is requested in order to define the level of recurrence in the axilla and exclude further metastatic spread.

Sample size

The goal of the study is to establish that the intervention (no further axillary surgery) is statistically non-inferior to standard of care (completion ALND) for the primary endpoint breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) at 5 years.

Clinical non-inferiority is in this study defined as a 5-year BCSS not worsened by more than 2.5% when refraining from ALND. To show that (i.e. a 5-year BCSS of 89.5% in the intervention group compared to 92% in the standard of care group - using a one-sided α of 10% and with a power of 80%) a total of 225 breast cancer deaths need to be observed in the study. This corresponds to show that the upper one-sided 90% confidence interval for the hazard ratio (HR: Intervention/Standard of care) falls below 1.33. Power calculations are based on Swedish data which may differ from survival outcomes in other countries. Therefore, stratification according to country of primary treatment is performed.

It is anticipated that the study will be able to recruit up to 700 patients per year during a 5-year period giving a total sample size of 3500 patients. With allowance for an extra year of follow-up the necessary number of events (225) is expected to be reached. The total study time will be approximately 7 years.

Data monitoring committee

An independent data monitoring committee will review the data and carry out one closed interim analysis 3 years after the date on which the first study patient was randomized, or when 2000 patients have been included in the study, whichever comes first. The purpose of this interim analysis is to assess the recruitment to the study, the rate of overall breast-cancer related events and to make sure that patients in the intervention group do not appear to fare significantly worse than patients in the standard of care group. The committee may recommend terminating the study if a significant benefit in favour of standard of care for breast-cancer deaths is shown, such that the HR for intervention versus standard of care significantly (p = 0.001) exceeds 1, or if the recruitment is so low that that the necessary number of events is unlikely to be reached. If the committee determines that it is safe to proceed with the study, the results of the analysis will remain unknown to everyone except the committee members.

Statistical methods

For the primary endpoint breast cancer-specific survival, time will be calculated from the date of randomization to the date of breast cancer death (BCD). A breast cancer death will be defined as a death with information of a preceding or concurrent regional or distant recurrence. Isolated ipsilateral in-breast recurrences will thus not count towards BCD. Disease-free survival time is calculated from the date of randomization to the date of loco-regional recurrence, date of distant recurrence, date of second malignancy or date of death, whichever comes first. For event-free patients time will be calculated from the date of randomization to the date of last visit.

Event-specific cumulative incidence rates - taking competing risks into account - will be estimated using non-parametric methods. Differences in time to failure will be tested using the log-rank test. The effect of the intervention on time to failure will be estimated using proportional hazards regression. Both unadjusted analyses and analyses adjusting for potential confounding factors will be performed. Longitudinal health-related quality of life data will be analysed using generalized linear models. Test for interactions between treatment and time – indicating a differential effect of treatment over time – will also be performed. Both intent-to-treat analyses and treatment received analyses will be performed for the primary outcome.

All analyses will be performed using StataCorp 2015 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Discussion

Despite a general decline in the use of ALND after the first publication of the results from the ASOSOG Z0011 trial in 2011 [16], there is still considerable variation in surgical management of the axilla across European centers [31]. Even after the recent publication of long-term results from the same study, showing essentially no difference in recurrence rates between patients undergoing or omitting completion ALND [32], the base of evidence remains small. A review by Schmidt-Hansen et al. [33] identified only three prospective randomized trials comparing SN-biopsy with or without completion ALND in patients with SN metastases, reporting on a total of 2020 patients. This said, two of these three trials did exclusively include cases of SN-micrometastasis (AATRM 048/13/2000 and IBCSG-23-01) and the third trial (ACOSOG Z0011) included only 430 patients with SN-macrometastases while the remaining 301 patients had SN-micrometastases only; the size of SN-metastasis was not reported on the 125 patients left in the intent-to-treat sample (N = 856). Thus, evidence on the significance of completion ALND in patients with SN-macrometastasis is limited to a small sample of individuals with T1-T2 tumors treated by breast-conserving surgery. Despite this, the use of ALND in SN-positive disease seems to decrease even in patients treated by mastectomy [34]; in other instances, ALND may be replaced by regional radiotherapy after the results of the AMAROS trial [24]. This clearly leaves a need for further prospective trials, including patients treated by mastectomy.

In the setting of neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NAST), it has been argued that SN biopsy pre NAST has the disadvantage to necessitate a second axillary intervention (ALND) in case of SN-macrometastases in cN0 patients [35]. The false negative rate in repeat SN biopsy after NAST is high [36] but is acceptable if performed primarily after NAST in case at least three SN can be identified. While the latter has become routine in some countries, SN biopsy is still performed prior to NAST in Sweden and other countries in case of clinical node negativity. The SENOMAC trial gives the opportunity to benefit from the up-front staging information the SN biopsy can offer in cN0 patients while investigating whether a completion ALND is necessary in those with up to two SN macrometastases. Thus, this trial may conclude whether or not ALND is at all indicated in patients with pre NAST SN macrometastases, given that no tumor progression is observed during NAST.

In summary, the SENOMAC trial aims to answer the clinically pending questions concerning the indications for ALND in T1-T3 tumors in cN0 patients. Importantly, it not only includes both breast conservation and mastectomy but also patients selected for neoadjuvant systemic therapy.

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge the significant contribution of late Dorthe Grabau, senior pathologist, to the study design and protocol. The SENOMAC Trialists’ Group consists of, apart from the authors, the trial committees of each participating country, namely at the date of writing Peer Christiansen, Tove Filtenborg Tvedskov and Birgitte Offersen, Denmark, Toralf Reimer and Thorsten Kühn, Germany, Michalis Kontos, Greece, and Oreste Gentilini, Italy.

Funding

This trial is supported by grants from Swedish Research Council, Swedish Cancer Foundation, Swedish Society of Medicine, Swedish Breast Cancer Association (BRO) and Swedish Society for Medical Research. None of the funding bodies had any part in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data are managed by the Clinical Trials Unit at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Data access is only granted once the study is terminated. A dedicated Data Access Committee receives applications by third parts to use data or material collected during this trial and confirms data extraction with the Trial Committee.

Authors’ contributions

JdB is the sponsor and coordinating investigator of the SENOMAC trial. All listed authors have designed the trial protocol and are members of the Trial Committee. JdB drafted this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This trial was approved by the Ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, with registration number 2014/1165-31/1. Patients may only be randomized after written informed consent.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ACOSOG

American College of Surgeons Oncology Group

- ALND

Axillary lymph node dissection

- BCD

Breast cancer death

- BCSS

Breast cancer-specific survival

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTV

Clinical target volume

- eCRF

Electronic Case Report Form

- EORTC

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- ESTRO

European SocieTy for Radiotherapy and Oncology

- GCP

Good Clinical Practice

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IBCSG

International Breast Cancer Study Group

- IMN

Internal mammary nodes

- NAST

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy

- PMRT

Post-mastectomy radiotherapy

- SN

Sentinel Node

Contributor Information

Jana de Boniface, Phone: +46 70 2472305, Email: jana.de-boniface@ki.se.

Jan Frisell, Email: jan.frisell@ki.se.

Yvette Andersson, Email: yvette.andersson@regionvastmanland.se.

Leif Bergkvist, Email: leif.bergkvist@regionvastmanland.se.

Johan Ahlgren, Email: johan.ahlgren@regionorebrolan.se.

Lisa Rydén, Email: lisa.ryden@med.lu.se.

Roger Olofsson Bagge, Email: roger.olofsson@gu.se.

Malin Sund, Email: malin.sund@surgery.umu.se.

Hemming Johansson, Email: hemming.johansson@sll.se.

Dan Lundstedt, Email: dan.lundstedt@vgregion.se.

on behalf of the SENOMAC Trialists’ Group:

Peer Christiansen, Tove Filtenborg Tvedskov, Birgitte Offersen, Toralf Reimer, Thorsten Kühn, Michalis Kontos, and Oreste Gentilini

References

- 1.Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE. Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989;63(1):181–187. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890101)63:1<181::AID-CNCR2820630129>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Bauer M, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Fisher ER, Cruz AB, et al. Relation of number of positive axillary nodes to the prognosis of patients with primary breast cancer. An NSABP update. Cancer. 1983;52(9):1551–1557. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831101)52:9<1551::AID-CNCR2820520902>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soerjomataram I, Louwman MW, Ribot JG, Roukema JA, Coebergh JW. An overview of prognostic factors for long-term survivors of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(3):309–330. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th Edition. ISBN: 978-1-4443-3241-4 ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

- 5.Nieweg OE, Jansen L, Valdés Olmos RA, Rutgers E, Peterse JL, Hoefnagel KA, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26(Suppl 4):S11–S16. doi: 10.1007/s002590050572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson Y, de Boniface J, Jönsson PE, Ingvar C, Liljegren G, Bergkvist L, et al. Axillary recurrence rate 5 years after negative sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99(2):226–231. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Costantino JP, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary- lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):927–933. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pepels MJ, Vesthens JH, de Boer M, Smidt M, van Diest PJ, Borm GF, et al. Safety of avoiding routine use of axillary dissection in early stage breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125(2):301–313. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Ploeg IM, Nieweg OE, van Rijk MC, Valdés Olmos RA, Kroon BB. Axillary recurrence after a tumour-negative sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(12):1277–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veronesi U, Galimberti V, Mariani L, Gatti G, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer: early results in 953 patients with negative sentinel node biopsy and no axillary dissection. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celebioglu F, Perbeck L, Frisell J, Gröndal E, Svensson L, Danielsson R. Lymph drainage studied by lymphoscintigraphy in the arms after sentinel node biopsy compared with axillary lymph node dissection following conservative breast cancer surgery. Acta Radiol. 2007;48(5):488–495. doi: 10.1080/02841850701305440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Land SR, Kopec JA, Julian TB, Brown AM, Anderson SJ, Krag DN, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in sentinel node-negative adjuvant breast cancer patients receiving sentinel-node biopsy or axillary dissection: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project phase III protocol B-32. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):3929–3936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Reintgen DS, Blumencrantz PW, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3657–3663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sackey H, Magnuson A, Sandelin K, Liljegren G, Bergkvist L, Fülep Z, et al. Arm lymphoedema after axillary surgery in women with invasive breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2014;101(4):390–397. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Degnim AC, Griffith KA, Sabel MS, Hayes DF, Cimmino VM, Diehl KM, et al. Clinicopathologic eatures of metastasis in nonsentinel lymph nodes of breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2003;98(11):2307–2315. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Blumencrantz PW, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(6):569–575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caudle AS, Hunt KK, Tucker SL, Hoffman K, Gainer SM, Lucci A, et al. American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011: impact on surgeon practice patterns. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(10):3144–3151. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2531-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gainer SM, Hunt KK, Beitsch P, Caudle AS, Mittendorf EA, Lucci A. Changing behavior in clinical practice in response to the ACOSOG Z0011 trial: a survey of the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(10):3152–3158. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2523-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliano AE, Morrow M, Duggal S, Julian TB. Should ACOSOG Z0011 change practice with respect to axillary lymph node dissection for a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer? Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29(7):687–692. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latosinsky S, Berrang TS, Cutter CS, George R, Olivotto I, Julian TB, et al. CAGS and ACS evidence based reviews in surgery. 40. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis. Can J Surg. 2012;55(1):66–69. doi: 10.1503/cjs.036011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, Viale G, Luini A, Veronesi P, Baratella P, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23–01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park J, Fey JV, Naik AM, Borgen PI, Van Zee KJ, Cody HS., 3rd A declining rate of completion axillary dissection in sentinel lymph node- positive breast cancer patients is associated with the use of a multivariate nomogram. Ann Surg. 2007;245(3):462–468. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250439.86020.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pepels MJ, de Boer M, Bult P, van Dijck JA, van Deurzen CH, Menke-Pluymers MB, et al. Regional recurrence in breast cancer patients with sentinel node micrometastases and isolated tumor cells. Ann Surg. 2012;255(1):116–121. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823dc616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, Meijnen P, van de Velde CJ, Mansel RE, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive senintel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devoogdt N, De Groef A, Hendrickx A, Damstra R, Christiaansen A, Geraerts I, et al. Lymphoedema functioning, disability and health questionnaire (Lymph-ICF): reliability and validity. Phys Ther. 2011;91(6):944–957. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen MF, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, Hammerlid E, van Pottelsberghe C, Curran D, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(14):1796–1807. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, Franklin J, te Velde A, Muller M, et al. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire Module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2756–2768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Offersen BV, Boersma LJ, Kirkove C, Hol S, Aznar MC, Biete Sola A, et al. ESTRO consensus guideline on target volume delineation for elective radiation therapy of early stage breast cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2015;114:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gondos A, Jansen L, Heil J, Schneeweiss A, Voogd AC, Frisell J, et al. Time trends in axilla management among early breast cancer patients: persisting major variation in clinical practice across European centers. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(6):712–719. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1136751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giuliano AE, Ballman K, McCall L, Beitsch P, Whitworth PW, Blumencrantz P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: long-term follow-up from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (Alliance) ACOSOG Z001 randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2016;264(3):413–420. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt-Hansen M, Bromham N, Haster E, Reed MW. Axillary surgery in women with sentinel node-positive operable breast cancer: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Spring. 2016;5:85. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1712-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenny TC, Dove J, Shabahang M, Woll N, Hunsinger M, Morgan A, et al. Widespread implications of ACOSOG Z0011: effect on total mastectomy patients. Am Surg. 2016;82(1):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ataseven B, von Minckwitz G. The impact of neoadjuvant treatment on surgical options and outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, Fleige B, Hausschild M, Helms G, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):609–618. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are managed by the Clinical Trials Unit at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Data access is only granted once the study is terminated. A dedicated Data Access Committee receives applications by third parts to use data or material collected during this trial and confirms data extraction with the Trial Committee.