Abstract

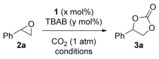

The cooperative catalytic activity of several metal corrole complexes in combination with tetrabutyl‐ammonium bromide (TBAB) has been investigated for the reaction of epoxides with CO2 leading to cyclic carbonates. It was found that the use of just 0.05 mol % of a manganese(III)corrole with 2 mol % TBAB exhibits excellent catalytic activity under an atmosphere of CO2.

Keywords: carbon dioxide fixation, cooperative catalysis, corroles, quaternary ammonium salts, sustainable chemistry

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is available in almost infinite amounts in our atmosphere and oceans, but its utilization as feedstock for the chemical industry is often prevented by its thermodynamic stability. Nevertheless, significant progress has been made in the utilization of CO2 as a simple C1 synthon for organic synthesis over the last years.1 However, only a few large‐scale industrial processes utilizing CO2 as a simple feedstock for organic reactions have been achieved so far, such as the production of urea, methanol, salicylic acid, or cyclic carbonates.

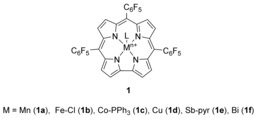

Dioxolanones are useful intermediates to synthesize vicinal diols,2 which are industrially useful monomers, polymers, surfactants, plasticizers, cross‐linking agents, curing agents, and solvents, to name a few applications only.3 The synthesis of organic carbonates by catalytic insertion of carbon dioxide into a carbon–oxygen bond of an epoxide usually requires the use of high temperature and pressure. Various catalysts for this reaction have been developed, including metal complexes4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 (e.g., metal–salen complexes and metalloporphyrins) and organocatalysts (e.g., quaternary onium salts or N‐heterocyclic carbenes).11 Among these catalysts, metalloporphyrins have shown relatively high catalytic activity under CO2 autoclave conditions (>5 bar) and at elevated temperatures (usually >100 °C).4, 8, 9, 10 In contrast to porphyrin‐based systems, the closely related corrole macrocycle can stabilize metal ions in higher oxidation states,12, 13, 14, 15, 16 making them unique reagents with extraordinary catalytic properties.17, 18 In this study, we focused on manganese, iron, cobalt, copper, antimony and bismuth 5,10,15‐tris(pentafluorophenyl) corrole (MTpFPC) complexes 1 a–f (Figure 1) for CO2 fixation reactions. The center metal ions are complexed as BiIII,13 CoIV,14 CuII,15 FeIV,14, 16 and MnIII,14 accordingly, and the three C6F5‐groups in the meso positions 5, 10, and 15 of the macrocycle withdraw electron density from the 18‐π‐electron system. A consequence of this effect is the improved stability of such high‐valent metal corroles. Nozaki and co‐workers recently reported the use of Fe corroles and bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium chloride as an additive for the copolymerization of epoxides with CO2 under high pressure conditions.18 Interestingly, in this case study, the formation of the cyclic carbonates was more or less totally suppressed. Based on our recent interest in the use of metal corroles as catalysts17a and the recent progress in the use of cooperative CO2‐fixation catalyst systems based on metal complexes in combination with simple nucleophilic halide sources such as tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB),5 we reasoned that the use of alternative metal‐based corroles together with TBAB may result in a very powerful cooperative catalyst system for the CO2 fixation with epoxides. Such a catalyst system may even operate under an atmospheric pressure of CO2 at low temperature. Because of this lower CO2 pressure, we argued that this synergistic catalyst combination may allow us to selectively access cyclic carbonates instead of polymerization products, which would thus result in a highly complementary approach to Nozaki's impressive polymerization protocol18 by relying on a similar corrole system.

Figure 1.

Structures of metal corrole complexes 1 a–f used in this work.

Table 1 gives an overview of the most significant results obtained in a detailed screening of different metal corroles 1 in combination with TBAB as a cheap nucleophilic organic halide source for the solvent‐free CO2 fixation of styrene oxide (2 a) under an atmosphere of CO2 (using a balloon). As expected, only the synergistic combination of corroles 1 and TBAB allows for a reasonable conversion within a relatively short reaction time (at slightly elevated temperatures). In contrast, the absence of either 1 or TBAB resulted in no or only very slow formation of 3 a only (entries 1–4). Testing of the different metal corroles 1 a–f next showed that Mn‐ and Fe‐based ones clearly outperformed the other metal complexes tested herein (entries 1 and 5–9). Owing to the superior catalytic performance of Mn‐corrole 1 a we further fine‐tuned the reaction conditions with this system (entries 10–13). Hereby, it was found that reducing the catalyst loading below 0.01 mol % 1 a resulted in a reduced conversion rate (entries 10 and 11). On the other hand, carrying out the reaction with 0.05 mol % 1 a and 2 mol % TBAB (entry 12) leads to a higher conversion, and a slightly longer reaction time of 8 h results in almost full conversion of 2 a under relatively mild conditions with low Mn‐corrole loadings (entry 13).

Table 1.

Identification of the optimum catalyst system for the CO2 fixation of epoxide 2 a.

| Entry[a] | 1 [mol %] | TBAB [mol %] | T [°C] | t [h] | Conv.[b] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mn 1 a (0.05 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 48 |

| 2 | – | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 9 |

| 3 | Mn 1 a (0.05 %) | – | 60 | 4 | n.r. |

| 4 | Mn 1 a (0.05 %) | 1 % | 25 | 4 | 8 |

| 5 | Fe 1 b (0.05 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 34 |

| 6 | Co 1 c (0.05 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 13 |

| 7 | Cu 1 d (0.05 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 13 |

| 8 | Sb 1 e (0.05 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 12 |

| 9 | Bi 1 f (0.05 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 15 |

| 10 | Mn 1 a (0.01 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 29 |

| 11 | Mn 1 a (0.003 %) | 1 % | 60 | 4 | 15 |

| 12 | Mn 1 a (0.05 %) | 2 % | 60 | 4 | 60[c] |

| 13 | Mn 1 a (0.05 %) | 2 % | 60 | 8 | >95[d] |

[a] 4 mmol scale (neat); [b] determined by 1H NMR of the reaction mixture; [c] less than 15 % conversion in the absence of 1 a; [d] the product could be quantitatively isolated after filtration over a short plug of silica.19 n.r.=no reaction.

Having identified the best‐suited cooperative catalyst combination and reaction conditions for the solvent‐free CO2‐fixation of epoxide 2 a, we next investigated the scope of this protocol by using other simple epoxides 2 (Table 2). Most of the epoxides reacted at a similar rate to the parent styreneoxide 2 a at 60 °C. Only the diphenylmethylether‐based starting material (entry 6) and epichlorhydrine (entry 7) showed a slightly slower conversion of less than 90 % under standard conditions. In contrast, some aliphatic epoxides even showed good conversion at room temperature (entries 10–12), thus proving the generality of this method for the CO2 fixation with epoxides 2.

Table 2.

Application scope.

| Entry[a] | R | T [°C] | t [h] | Conv.[b] [%] | Yield[c] [%] | TON[d] | TOF[d] [h−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ph | 60 | 8 | >95 | 94 | 1880 | 235 |

| 2 | Ph | 25 | 8 | 25 | 24 | 480 | 60 |

| 3 | 4‐Cl‐C6H4 | 60 | 8 | >98 | 96 | 1920 | 240 |

| 4 | 4‐F‐C6H4 | 60 | 8 | >98 | 98 | 1960 | 245 |

| 5 | PhOCH2 | 60 | 8 | >95 | 94 | 1880 | 235 |

| 6 | Ph2CHOCH2 | 60 | 8 | 71 | 70 | 1400 | 175 |

| 7 | ClCH2 | 60 | 8 | 89 | 88 | 1760 | 220 |

| 8 | vinyl | 60 | 8 | >98 | 93 | 1860 | 232 |

| 9 | but‐3‐enyl | 60 | 8 | >98 | 98 | 1960 | 245 |

| 10 | but‐3‐enyl | 25 | 20 | >98 | 98 | 1960 | 98 |

| 11 | Me | 25 | 8 | 57 | 55 | 1100 | 137 |

| 12 | Me | 25 | 20 | >95 | 88 | 1760 | 88 |

[a] 4 mmol scale (neat); [b] judged by 1H NMR of the reaction mixture; [c] isolated yield after filtration over a short plug of silica; [d] based on 1 a. TON=turnover number; TOF=turnover frequency.

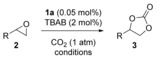

The synergistic effect of an organic nucleophilic halide source and a Lewis acidic metal complex for these CO2‐fixation reactions has been the subject of detailed recent mechanistic studies.5, 7, 8 For example the groups of North et al. and Ren and Lu have done systematic investigations of salen‐ and salphen‐based systems,5, 7 while Hasegawa et al. have carried out very detailed DFT investigations for porphyrin‐based catalyst systems at elevated CO2 pressure.8 Based on these comprehensive studies we propose that the herein‐reported Mn‐corrole 1 a/TBAB system operates through an analogous mechanism (Scheme 1). To corroborate the mechanism, we performed DFT calculations of the three main proposed intermediates A–C. The corrole macrocycle exhibits a dome‐shaped structure after coordination with the ring‐opened substrate (intermediate A) and the manganese atom lies slightly above the plane defined by the four nitrogen atoms of the corrole ring. The Mn atom is coordinated by the four nitrogen atoms and axially by the oxygen atom of the ring‐opened epoxide. After the insertion reaction of CO2, the axial pyramidal conformation is distorted (see structure B). Herein, one O atom originating from CO2 is axially coordinating with a distance of 1.8 Å to the manganese ion, and the other oxygen atom is 2.86 Å apart from the Br methylene group and can easily perform, in the final step, the ring‐closure to the cyclic carbonate 3.

Scheme 1.

Proposed synergistic catalysis mode for the Mn‐corrole 1 a‐ and TBAB‐catalyzed CO2 fixation with epoxides (based on recent studies),7, 8 and calculated molecular structures of the proposed intermediates A–C.

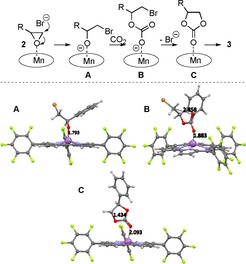

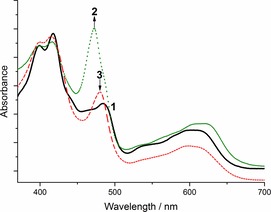

To obtain further mechanistic details, we investigated the time course UV/Vis spectral changes occurring to the catalyst 1 a during the reaction. The typical UV/Vis absorption spectrum of 1 a and propylene oxide (Figure 2, solid black line, 1) changes significantly after addition of TBAB under a CO2 atmosphere (dotted green line, 2). While the Soret band maximum at 410–420 nm remained unaffected, a strong increase of the absorption band and a hypsochromic shift from 485 to 472 nm was immediately observed (Figure 2, transition 1→2). The latter absorption band is known to be very sensitive towards axial ligation and the change in absorption wavelength can be attributed to the binding of an axially ligated oxygen atom either as alkoxide intermediate A and/or carbonate intermediate B (compare with Scheme 1).20, 21 To get further information regarding the expected intermediates (Scheme 1) and the apparent suggestion that the electronic spectra presented in Figure 2 reflect them, we compared the spectral changes upon coordination of simple model compounds to corrole 1 a (i.e., an alkoxide for intermediate A, a carboxylate for intermediate B, Figures S1 and S2). The hereby obtained UV/Vis spectra are identical to the UV/Vis spectrum of 1 a in the presence of propylene oxide, TBAB and CO2 (dotted green line, Figure 2) and clearly support the presence of an axially ligated oxygen.20, 21 However, no noticeable differences between the spectra obtained upon coordination of an alkoxide or a carboxylate to 1 a could be detected, still making it impossible to unambiguously assign the illustrated UV/Vis spectrum in Figure 2 (dotted green line, 2) to either intermediate A or B.

Figure 2.

UV/Vis absorption spectra of 1 a during the CO2 fixation reaction of propylene oxide to 4‐methyl‐1,3‐dioxolan‐2‐one. Solid black line: 1 a in propylene oxide at 20 °C; dotted green line: after addition of propylene oxide, TBAB and CO2 bubbling; dashed red line: after full conversion of propylene oxide to cyclic carbonate 3.

Finally, after full conversion of propylene oxide to carbonate 3 the UV/Vis absorption spectrum (Figure 2, dashed red line, 3) changes back, comparably to the one observed in the beginning for the non‐reacted catalyst species 1 a (Figure S3).

After recycling the manganese corrole species (column chromatography of the reaction mixtures first with heptanes/EtOAc=10:1–3:1 to isolate the carbonates and then with heptanes/EtOAc=1:1 to elute the catalyst), analysis of ESI‐MS and 19F NMR spectra (Figures S4 and S5) revealed that the manganese corrole remained intact and was reusable for further transformations.

To conclude, we have identified that TBAB/MnIIIcorrole 1 a is the best‐suited cooperative catalyst combination so far. Owing to the superior catalytic performance of Mn‐corrole 1 a we further fine‐tuned the reaction conditions with this system. Hereby, it was found that reducing the catalyst loading below 0.01 mol % 1 a resulted in a reduced conversion rate. On the other hand, carrying out the reaction with 0.05 mol % 1 a and 2 mol % TBAB led to an increased conversion, and finally a slightly longer reaction time (8 h) results in >95 % conversion of 2 under relatively mild conditions with low Mn‐corrole loadings.

The dramatic changes observed in the time course UV/Vis spectra for 1 a during the reaction could be attributed to the effect of axial binding of the oxygen atom of the ring‐opened epoxide, and to the intermediate B after CO2 insertion/fixation. Finally, we have shown that recycling of the Mn‐corrole is possible and makes the Lewis‐acidic manganese corrole complex reusable for further transformations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We kindly acknowledge financial support of the projects FWF‐P28167‐N34 and P26387‐N28 by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). The NMR spectra were acquired in collaboration with the University of South Bohemia (CZ) with financial support from the European Union through the EFRE INTERREG IV ETC‐AT‐CZ program (project M00146, “RERI‐uasb”).

M. Tiffner, S. Gonglach, M. Haas, W. Schöfberger, M. Waser, Chem. Asian J. 2017, 12, 1048.

Contributor Information

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schöfberger, Email: wolfgang.schoefberger@jku.at.

Prof. Dr. Mario Waser, Email: mario.waser@jku.at.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Aresta M., Dibenedetto A., Angelini A., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1709–1742; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Liu Q., Wu L., Jackstell R., Beller M., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5933–5947; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Rintjema J., Kleij A. W., Synthesis 2016, 48, 3863–3878. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trost B. M., Angle S. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 6123–6124. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clements J. H., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 663–674. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ema T., Miyazaki Y., Koyama S., Yano Y., Sakai T., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 4489–4491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Castro-Osma J. A., North M., Wu X., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 2100–2107; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. North M., Pasquale R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2946–2948; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 2990–2992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Decortes A., Kleij A. W., ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 831–834; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Chang T., Jin L., Jing H., ChemCatChem 2009, 1, 379–383; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Paddock R. L., Nguyen S. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11498–11499; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Whiteoak C. J., Kielland N., Laserna V., Escudero-Adan E. C., Martin E., Kleij A. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Lu X.-B., Liang B., Zhang Y.-J., Tian Y.-Z., Wang Y.-M., Bai C.-X., Wang H., Zhang R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3732–3733; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Lu X.-B., Zhang Y.-J., Liang B., Li X., Wang H., J. Mol. Catal. A 2004, 210, 31–34; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Lu X.-B., Darensbourg D. J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1462–1484; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Ren W.-M., Liu Y., Lu X.-B., J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 9771–9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ema T., Miyazaki Y., Shimonishi J., Maeda C., Hasegawa J.-Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15270–15279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jin L., Jing H., Chang T., Bu X., Wang L., Liu Z., J. Mol. Catal. A 2007, 261, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aida T., Inoue S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Li F., Xiao L., Xia C., Hu B., Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 8307–8310; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Zhou Y., Hu S., Ma X., Liang S., Jiang T., Han B., J. Mol. Catal. A 2008, 284, 52–57; [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Tsutsumi Y., Yamakawa K., Yoshida M., Ema T., Sakai T., Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5728–5731; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11d. Yang H., Wang X., Ma Y., Wang L., Zhang J., Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 7773–7782; [Google Scholar]

- 11e. Toda Y., Komiyama Y., Kikuchi A., Suga H., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6906–6910; [Google Scholar]

- 11f. Liu S., Suematsu N., Maruoka K., Shirakawa S., Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4611–4615; [Google Scholar]

- 11g. Caló V., Nacci A., Monopoli A., Fanizzi A., Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 2561–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abu-Omar M. M., Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 3435–3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reith L. M., Stiftinger M., Monkowius U., Knör G., Schoefberger W., Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 6788–6797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barata J. F. B., Graça M., Neves P. M. S., Faustino M. A. F., Tomé A. C., Cavaleiro J. A. S., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 3192–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lemon C. M., Huynh M., Maher A. G., Anderson B. L., Bloch E. D., Powers D. C., Nocera D. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2176–2180; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 2216–2220. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simkhovich L., Goldberg I., Gross Z., Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 5433–5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Schöfberger W., Faschinger F., Chattopadhyay S., Bhakta S., Mondal B., Elemans J. A. A. W., Müllegger S., Tebi S., Koch R., Klappenberger F., Paszkiewicz M., Barth J. V., Rauls E., Aldahhak H., Schmidt W. G., Dey A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2350–2355; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 2396–2401; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Aviv-Harel I., Gross Z., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 717–736. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakano K., Kobayashi K., Ohkawara T., Imoto H., Nozaki K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8456–8459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The presence of minor amounts of remaining unreacted 2 a can be rationalized by the fact that traces of 2 a condense on the top of the reaction tube and subsequently cannot undergo CO2 insertion.

- 20.For related studies on Mn-corroles see:

- 20a. Kumar A., Goldberg I., Botoshansky M., Buchman Y., Gross Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15233–15245; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Shen J., El Ojaimi M., Chkounda M., Gros C. P., Barbe J.-M., Shao J., Guilard R., Kadish K. M., Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 7717–7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For a related spectroscopic study on metalloporphyrins: Guo M., Dong H., Li J., Cheng B., Huang Y.-Q., Feng Y.-Q., Lei A., Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1190–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary