Abstract

Background

Overweight and obesity prevention interventions rarely take into account the unique role of fathers in promoting healthy home environments.

Objective

To use qualitative methodology to examine the views of Hispanic mothers of 2-to-5-year-old children regarding fathers’ roles in promoting healthy behaviors at home.

Design

Nine focus groups were conducted in Spanish with Hispanic mothers of preschool-aged children (n=55) from October to December, 2015.

Participants/settings

Hispanic mothers were recruited from churches, community agencies, and preschools located in five zip codes in the southwest part of Oklahoma City, OK.

Analysis

Questions examined the views of Hispanic mothers regarding fathers’ roles in promoting healthy behaviors at home. Focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed in Spanish, translated into English, and coded and analyzed for themes by two coders using NVivo v.10 software.

Results

Four themes were identified: fathers’ disagreement with mothers about food preferences and preparation, fathers’ support for child’s healthy eating, fathers’ support for child’s physical activity, and fathers’ lack of support for a healthy home food environment. Fathers’ traditional expectations about the type of foods and portion sizes adults should eat conflicted with mothers’ meal preparations. Mothers reported that, while they favored eating low-calorie meals, the meals fathers preferred eating were high-calorie meals (i.e., quesadillas). In general, fathers supported healthy eating and physical activity behaviors for their children. Supportive behaviors for children included preparing healthy meals, using healthier cooking methods, grocery shopping with their children for healthy foods, and asking the child to participate in household chores and/or play sports. Fathers’ unsupportive behaviors included bringing high-calorie foods, such as pizza, and sugary drinks into the home, using sweets and savory foods for emotion regulation, and displaying an indulgent parental feeding style.

Conclusions

Mothers' views of fathers' perceived roles in child eating and physical activity, and maintaining a healthy eating environment, have important implications for the success of promoting healthy behaviors in the homes of Hispanic families.

Keywords: Hispanic, fathers, family, healthy eating, preschoolers

INTRODUCTION

The food environment has an important influence on family eating behaviors at home.1 Among Spanish-speaking Latino families, determinants of food in the home have been explained by mothers’ food preparation skills, family members’ food preferences, and culinary traditions.2 Parental food practices modeling consumption of fruits and vegetables in Hispanic homes have been positively associated with availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables.3 In contrast, parental acculturation level, as assessed by language spoken at home, and perceived benefits of consuming fast food have been inversely related with availability of fruits and vegetables at home.3 Attention to the home food environment is important because of its association with consuming a healthy diet.4 Availability of high-calorie foods in the home and parents’ frequent consumption of soda and energy-dense snacks have been linked with decreased diet quality in Hispanic children.5 Therefore, attention to the multiple aspects of the home food environment is critical because of the influence of food available and family eating behaviors.6–8 Yet, there is limited research documenting the role fathers have in home food availability or support for family healthy eating.

Parents also have the ability to model healthy physical activity (PA) behaviors for their children that can last a lifetime.9,10 While qualitative studies have reported Hispanic parents’ views of their role in promoting healthy food behaviors at home,2,11–13 few studies have described parents’ views regarding fostering PA behaviors.11,13,14 Hispanic parents’ engagement in child activities, and modeling PA, were identified as practices that encouraged preschoolers’ PA.14 Turning the television off was discussed by Hispanic parents as an important strategy to help overweight children lose weight.13 Mexican and Mexican-American fathers participating in focus groups described employing an authoritarian or authoritative approach to family PA and being more physically active than mothers.11 In the U.S., there is an obesity prevalence gap between racial and/or ethnic groups that seems to widen in the early developmental years.15 Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic/Latino children have greater sugar-sweetened beverage intake at age 2 and fast food intake at age 3, and a higher prevalence of having a television in the room where the child sleeps at age 4 than do Non-Hispanic White children; all have been documented as early risk factors for childhood obesity.16 Thus, identifying parental and familial factors that may affect children’s food and PA behaviors and, thus, childhood obesity prevalence in minority groups is important in the progression to health equality.

Important examinations of father-child feeding and PA behaviors have gained attention.17–19 Multicultural fathers’ full-time employment status has been associated with fewer hours of home food preparation than their part-time/employed counterparts; fathers’ life-work stress was associated with less encouragement of child’s healthful eating, less frequent family meals, lower consumption of fruits and vegetables, and more consumption of fast foods.20 However, limited studies have examined the role of Hispanic fathers in cultivating healthy family behaviors at home.2,11,21,22 Findings from these few studies suggest that fathers contribute to the availability of unhealthy foods in the home,2,21 and may not support mothers’ healthy eating or engagement in PA,22 but support child PA.11 An exploration of mothers’ views of fathers’ roles in supporting a healthy home environment and children’s eating and PA behaviors may be a way to gain information on family-life aspects to inform obesity prevention interventions. This is especially relevant among Hispanic families for whom nuclear and extended family is important.23 In Hispanics, preschool-aged children have the highest prevalence of obesity in the U.S., while adults have the second highest.24,25 The first step in developing effective interventions to promote healthy behaviors is gaining an in-depth understanding of why individuals behave the way they do.26,27 Focus group research is carefully planned to allow researchers to develop an understanding of why groups adopt new behaviors and maintain these behaviors once they have been initiated. The purpose of the present study was to use qualitative methodology to examine the views of Hispanic mothers of 2-to-5-year-old children regarding fathers’ roles in promoting healthy behaviors at home.

METHODS

Recruitment and Participants

A purposive sampling method28 was used to recruit participants from churches, community agencies, preschools, and daycares located in five zip codes in the southwest part of Oklahoma City, OK, where the highest concentration of Hispanic families live.29 Recruitment was conducted with the assistance of a community health worker who visited sites to attract information-rich cases (individuals who are personally experiencing the phenomenon being studied) whose responses to the interview questions would provide detailed information about feeding behaviors in Hispanic families with preschool-aged children.30 A screening was conducted to ensure that the inclusion criteria of self-identification as Hispanic, living with the target child and the child's father, and family being low income per Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program eligibility criteria31 were met. Fifty-five Hispanic mothers of 2-to-5-year-old children participated in nine focus groups conducted from October to December, 2015. The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. All participants provided written informed consent before data collection.

Qualitative Methodology

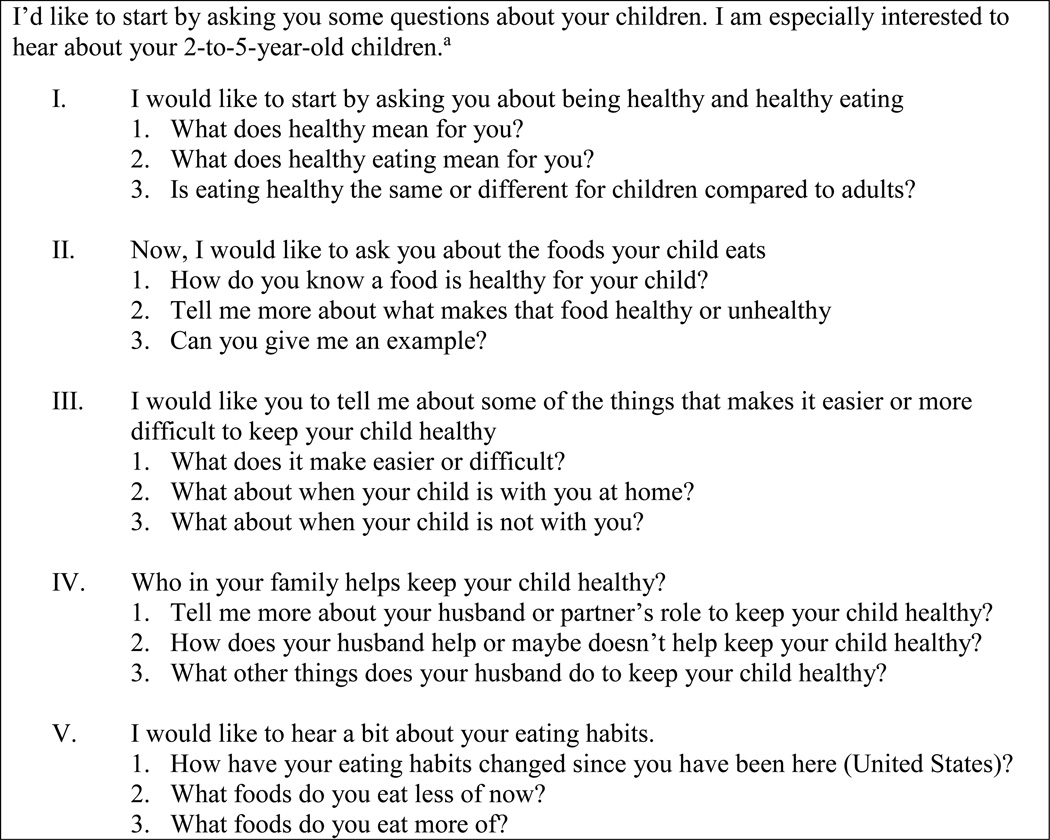

Researchers (KL, PB, and MC) formulated the focus group interview questions based on input from a participatory planning group of six community stakeholders (a Head Start teacher, a director of a bilingual child development center, a nutrition and wellness educator working with Hispanic families, a social worker, a family and community partnership coordinator of a non-profit organization, and the director of health services of a community agency) with an interest in the well-being of the Hispanic Community in Oklahoma City, a literature review of nutrition and health promotion studies,32–36 and the investigators’ previous experience working with Hispanic families. After the initial draft was developed, the interview guide was reviewed by the stakeholders, and modifications were made. Then, the interview guide was translated into Spanish using Marin’s double translation methodology,37 and was pilot tested with two mothers with characteristics similar to the target group. Amendments were made after the pilot test. Discussion topics included foods the child eats, challenges to keeping preschoolers healthy, family member(s) that helped mothers to keep their preschoolers healthy, and mothers’ eating habits. Sample questions from the interview guide are shown in the Figure.

Figure.

Sample questions from the semi-structured Focus Group Guide to examine the views of Hispanic mothers of 2-to-5 year-old children regarding fathers' roles in promoting healthy behaviors at home.

aIn qualitative research participants are asked open-ended questions that allow participants to share their beliefs and why they behave the way they do. The information about fathers’ roles in healthy behavior was elicited through question groups III, IV, and V.

A brief demographic questionnaire was constructed. Participants’ acculturation was assessed with two questions: 1) years of residence in the U.S. and 2) the language that participants generally read and speak (response options: only Spanish, Spanish better than English, Both equally, English better than Spanish, and only English).38 These proxies were used to discuss the possible relationship of mothers’ acculturation level with mothers’ perceptions of fathers’ behaviors. The questionnaire was translated into Spanish using similar methodology as indicated before.37 Participants completed the questionnaire before the focus group.

Focus groups were moderated by the principal investigator (KL), who had prior training in focus group research, and assisted by two student observers. The principal investigator is bilingual (Spanish-English) and has experience working with Hispanic families from different countries in community-based programs. The groups (n=9) were held at the local Latino Community Development Center in Oklahoma City, OK. Focus groups lasted approximately 120 minutes and had six participants on average. All focus groups were conducted in Spanish. After the meeting, participants received a $20 store gift card. Saturation (when no new information is being heard in interviews)30 was reached with the sixth focus group. However, as this was an understudied population, the decision was made to conduct an additional three groups to confirm that saturation had been reached.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded focus groups were transcribed verbatim in Spanish, translated into English by a certified translator, and checked for accuracy by the principal investigator (KL). To ensure the validity of the translations and the quotes, a professional translator who did not participate in the Spanish to English translations back translated the transcripts (English to Spanish) and all quotes. The back translations were discontinued when comparisons of five out of the nine transcripts with the original Spanish-language transcripts did not reveal major discrepancies. Similarly, the back translated quotes were checked for accuracy. No inconsistencies were found. These methods have been previously reported in qualitative work with Hispanics.12,39 Analyses were informed by grounded theory. Grounded theory is an inductive approach that allows theory to emerge from the data collected, thus “grounding” the theory in data, rather than selecting a theoretical framework or hypotheses a priori.40 NVivo v.10 software (QSR International) was used to code transcripts. Codes represented concepts within questions from the interview guide and concepts that emerged during the group. KL and MC developed the codebook, coded two transcripts together, and then revised the codebook. The remaining transcripts were coded independently with high agreement between coders. Any disagreements between coders were discussed until consensus was reached. Researchers analyzed the coded transcripts using thematic analysis, which is an inductive process. Researchers closely examined the coded text and identified “themes” or patterns that emerged across participants both within and across codes. Themes were often composed of several subthemes that identified multiple influences of the father on family eating and PA practices. After the identification of themes, the transcripts were reviewed again to select representative quotes for each theme. The transcripts were reviewed a final time for additional supporting and disconfirming evidence of themes.40,41

RESULTS

Mothers’ mean age was 34.6 ± 8.0 years. Eighty-two percent (n=45) had high school education or less, 78% (n=43) were unemployed, and 53% (n=29) participated in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Place of birth responses were Mexico, 85% (n=47), Central or South America, 11% (n=6), and U.S., 4% (n=2). Mothers spent a mean of 12.0 ± 6 years in the U.S., and 89% (n=49) spoke only Spanish or Spanish better than English.

The Table presents themes and representative quotes. A description of the themes follows.

Table.

Focus group themes and supporting quotes from fifty-five Hispanic mothers of 2-to-5-year-old children living in Oklahoma City, OK regarding their views of fathers' roles in promoting healthy behaviors at home

| Theme 1: Fathers’

disagreement with mothers about food preferences and preparation |

Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Traditional expectations about the type of foods to eat and portion sizes |

“And if you give them cereal

for dinner, you are lazy. I do it so that I don’t gain

weight and he says it is because I am lazy. It is very difficult.

And my husband has to eat with hot peppers and

everything.” (Focus group

1) “So at night, he tells me to make him some quesadillas. And I tell him, but I made soup, I made a stew, made rice, do you have to eat quesadillas every night? I tell him I used to like quesadillas but I don’t know why I have to make quesadillas every night. I tell him, you can eat something else and he wants just quesadillas, true. Every day, every night and so I think that influences how I feed my girls and their mealtimes.” (Focus group 8) “My husband… well he is really chubby. When I married him, he was used to my mother-in law cooking, like tortillas and flour, and lots of red meat every day…I felt bad because I do not eat meat, I eat cooked squash or something like that, and my husband is used to food cooked with lard and fried and I do not. These are habits like she [another participant] says that come from our ancestors and my husband still wants to eat that type of food.” (Focus group 2) |

| Tempting mothers to eat against their wishes | “…and husbands don’t understand about diets…and even when you don’t want anymore, they say, come on just a little bit. And I don’t have to eat at night anymore and they are like sit with me to keep me company. And it makes my mouth water. I tell him, I can’t eat at night, if you know how I have my sugar.” (Focus group 2) |

|

Theme 2: Fathers’ support

for child healthy eating |

|

| Support: Use of modeling behaviors to feed children fruits and vegetables, prepare healthy meals, and involve children in grocery shopping |

“What my husband does is to

take them fishing. He takes them fishing so they go running

outdoors, and what he does is to give them fruit, and salads,

because my kids love salads, and [he] cooks baked

chicken nuggets and he chops it and adds it in the salad. And that

way he has food to take with him for the children.”

(Focus group 2) “My husband takes them shopping to buy fruits, greens… they wash them and prepare them and eat them together.” (Focus group 7) |

| Lack of support: Use of food for emotion regulation or displaying an indulgent parenting style |

My husband likes to spoil them. If

he [child] wants a churro and sometimes we are home

and it is late, and sometimes so that he [child]

doesn’t cry or for another reason, well he goes to

the store and buys it for him.” (Focus group

4). “Or when the boy wants chips when we come out of the doctor’s office…[mother asking father] What do you buy a large bag for…Buy him a small one, the smallest one. And give it to him. And it is to just take the temptation away. Difference is that one is wrong: it is more convenient to buy him the large one, has more. But it is worse what he will eat. Buy him the small bag and that is it. There is no more, no more no more. But doesn’t buy in large amounts.” (Focus group 8) |

|

Theme 3: Fathers’ support

for child’s physical activity |

|

| Playing sports with children or asking children to help with household chores. |

“In my case, my husband, since

he likes to play soccer, he tells the children to come and play

soccer with him if they are watching TV. And they go with their dad.

Sometimes they even take the baby. They carry her and take her for a

walk. Sometimes they also play with a ball.” (Focus

group 9) “My husband also comes home after work and he asks the children to go outside to help or to play so that they are not inside watching TV.” (Focus group 9) |

|

Theme 4: Fathers’ lack of

support for a healthy food environment |

|

| Making high-calorie foods available in the home |

“My husband sometimes buys

boxes of frozen burritos and all those soups [referring to

Maruchana ramen noodle

soup], but I do not let them [children] eat

because they know I do not like those foods.”(Focus

group 6) “My husband works at the pizza place, forget it and I tell him not to bring pizza because if you keep bringing pizza for him, he will continue to gain weight. It is better not to bring him any more pizza. He says he will not bring him anymore and later, with the pizza, and the other one does not want anything with him and the little one is on the same path and I tell him no, don’t bring him, he is doing good. He is not fat or skinny. I tell him don’t bring him.” (Focus group 1). “Like my husband, he picked up the groceries. He came with who knows how many cokes and think I don’t know why [he] brought so many and I said why you want them for? [He says] well I will drink them. And I tell him: And you think you will drink them by yourself? I tell him, you bring food for your son, but you don’t want him to continue like this. I tell him no, don’t bring anymore. I tell him one thing, his son doesn’t drink the water now…And then I tell him, you know well you don’t need to bring that [coke], there is water. I tell him and you don’t bring diet, you should have brought diet.” (Focus group 3). |

| Involving fathers in nutrition education classes |

“Like in my case, if my

husband came [mother talking about nutrition education for

the family], he [father] would see that he

should not bring soda home nor pizza. He would help with

that.” (Focus group

1). “…they did something and everybody came and they had daycare for the children, they were given food because the husbands come very hungry. They [husbands] were given healthy food and it was good. They [husbands] were told that what they were eating was very healthy and had the class and it was for couples. I thought that was very good.” (Focus group 2). |

Toyo Suisan Company.

Fathers’ Disagreement with Mothers about Food Preferences and Preparation

Mothers reported that fathers were unsupportive and disagreed with the types of foods mothers ate and prepared for the family. Mothers often expressed that fathers’ expectations about the traditional foods (i.e., quesadillas), portion sizes adults should eat, and preparation methods conflicted with mothers’ views of healthier foods/meals options. Mothers described trying to eat healthier foods, perhaps at different times, to reduce temptation from the less healthy options the fathers requested, but fathers insisted that mothers keep them company during meals.

Fathers’ Support for Child Healthy Eating

Fathers’ food modeling reflected support for child healthy eating. This included feeding children fruits and vegetables, preparing healthy meals, and involving children in grocery shopping for fruits and vegetables. In contrast, fathers’ use of foods for emotion regulation or displaying an indulging parenting style were reflected by feeding their children sweets and savory foods when they cried, or buying the child large amounts of foods.

Fathers’ Support for Child Physical Activity

Mothers explained that fathers’ awareness of their children being sedentary (e.g., watching TV) prompted them to ask children to engage in PA. Fathers played sports (e.g., soccer) with their children, or asked children to help with age-appropriate household chores.

Fathers’ Lack of Support for a Healthy Food Environment

Fathers contributed to the availability of high-calorie foods in the home. Mothers faced specific challenges to making healthy foods available to their children when fathers brought home additional foods, like pizza or regular soda. Mothers talked about their desire for fathers to attend nutrition education classes so fathers would learn about healthful foods.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study aimed to examine the views of Hispanic mothers regarding fathers’ roles in promoting healthy behaviors at home. Participants reported that fathers generally disagreed with the types of foods that mothers ate and prepared. Others have indicated that Latino women reported that their male partners discouraged them from cooking healthful meals or participating in outdoor PA.22 Mothers explained that fathers regularly preferred to eat traditional foods/prepared meals that mothers perceived to be high-calorie and less healthy. Cuy-Castellanos et al.42 indicated that post-migrant Hispanic males discussed their preference for traditional Hispanic foods. Cespedes et al.43 reported that Mexican wives described preparing meals that were preferred by their spouses and that family consumption patterns favored frequent consumption of breaded and fried foods. Low-income pregnant Hispanic women acknowledged that their husbands’ food preferences were central to women’s food purchases, preparation, and consumption.44 Fathers’ meal consumption patterns and desire for mothers to keep them company at mealtimes took precedence; these scenarios tempted mothers to eat foods against their wishes. Familism, “a strong identification and attachment of individual with their families, and strong feelings of loyalty, reciprocity and solidarity among members of the same family,”45 is an important cultural value among Hispanics. Family gatherings/pressure to eat and family food preferences for unhealthy and/or traditional foods were identified as themes in focus groups with Mexican/Mexican-American women when discussing the role of familism and weight loss treatment outcomes.46 Regular family meals have been significantly associated with family dietary quality.47 Future research may consider investigating the role of familism in frequency of family meals and type of foods (i.e., traditional versus not) served at the table among Hispanic families.

Although women in the present study had spent a considerable number of years in the U.S., the majority still spoke only Spanish, or Spanish more than English, in the home. Acculturation has been described as the adoption of American cultural values, practices, and identity, and has been used to explain influences on immigrants’ food behaviors.48 Along with acculturation, enculturation, defined as the maintenance or retention of the culture of origin, represents cultural domains of variability of Latino immigrants in the U.S.49 Mothers’ responses here may reflect characteristics of the acculturation process and enculturation. For instance, traditional Mexican couple roles describe the husband as the dominant person in the relationship who must be consulted for family decisions, while the wife is expected to respect, obey, and be tolerant of her husband’s behaviors.50 Examples of these marital roles may be reflected in mothers’ responses to maintain preparation of traditional foods for their husbands or eating foods that their husbands asked them to eat, but that they did not wish to eat (enculturation). In contrast, mothers’ discussions of challenging husbands to eat different meals or refusing to eat foods that may be detrimental to their well-being or perceived as less healthy may illuminate the shift in marital roles with a subsequent renegotiation of the traditional roles towards a more egalitarian marital relationship that occurs in the process of acculturation to the U.S.49

While fathers displayed some behaviors that did not support healthy behaviors at home, mothers also commented that fathers made some contributions to healthy family eating and PA, such as feeding their children fruits and vegetables, preparing healthy meals for their children, involving children in grocery shopping for fruits and vegetables, and encouraging child’s PA by playing sports with them (Table). Findings regarding Hispanic fathers’ food parenting behaviors are limited. A qualitative study reported that Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant fathers acknowledged the importance of parental role modeling for children’s healthy lifestyle.11 Quantitative findings with Mexican-American fathers indicated that, while fathers’ positive involvement in child eating (i.e., monitoring high-calorie foods, providing small servings) was not significantly associated with child’s weight status, pressuring the child to eat, restricting food, or using food to control behaviors were associated with weight status.51 Future studies may include assessments of Hispanic fathers’ feeding practices and father and child food intake to elucidate whether fathers’ feeding practices or food consumption may influence children’s diets.

Mothers reported that fathers involved their children in sports and monitored their children’s sedentary level to prompt them to help with household chores. Turner et al.11 reported that fathers involving children in physical activities, like playing soccer, and fathers with an authoritative or authoritarian parenting style promoted family PA. Fathers’ PA modeling and monitoring behaviors are important for child obesity prevention. A qualitative study with Hispanic parents of 3-to-5-year-old children reported that parental modeling for PA activity encouraged children’s PA.14 Parental monitoring has also been associated with higher levels of PA in a multiethnic sample of school-age children.52 In a sample of 81 Latino preschool-aged children attending Head Start, 90.1% exceeded U.S. recommendations for daily PA of at least 120 m/day, and had more PA on the weekends than on weekdays.53 Hispanic fathers’ possible contributions to child PA by engaging them in leisure activity (i.e., walks), sports (i.e., soccer), or household chores, as shared by mothers in the study, should be further investigated.

Mothers also described that fathers used both sweet foods and savory foods to regulate the child’s emotions or to indulge the child. Parental use of food to control children’s behaviors has been posited to make the food offered as reward more desirable than the food the child is rewarded for eating, or described as a practice that may be conducive to child emotional eating later in life.54 Mexican-American fathers’ use of food to control behavior was negatively associated with school-age children’s weight status.51 In a study with low-income minority fathers of preschoolers, use of food as reward was associated with child’s intake of sugar-sweetened beverages in Latino children, but not in African-American children.55

Mothers discussed fathers bringing high-calorie foods to the home and their desire for fathers to attend nutrition education classes to learn what healthful foods to bring into the home. Although availability and accessibility of foods in the home has been related to consumption in Hispanic5,56 and multiethnic families,8,57 examinations of the type of food(s) family members may bring into the home are limited. Ayala et al.21 assessed whether a spouse or partner engaged in unsupportive behaviors related to diet (e.g., purchasing unhealthy foods or eating snacks in front of the family) in a sample of Latino families, and indicated that mothers reported significantly higher levels of fathers’ unsupportive behaviors than did fathers for mothers. The findings of the present study provide insight into food behaviors in which fathers, especially Hispanic fathers, may engage and their potential contribution(s) to healthy behaviors at home.

Although father-child feeding behaviors are an emerging area of study, there is still limited information about the roles of fathers, especially minority fathers, in behaviors that promote or impair family healthy eating and PA behaviors. The present study contributes useful information by providing insights regarding mothers’ perceptions of fathers’ behaviors. For instance, while fathers may engage in supportive behaviors for healthy eating and PA with their children, they may also engage in behaviors that contradict having a healthy home environment, such as bringing in high-calorie foods. While the involvement of fathers in programs to improve their children’s health behaviors has been advocated,58 much work is needed to uncover the nutrition education topics that may be more relevant to targeting with fathers. Findings from the present study may aid in gaining such insight.

Finally, minor themes included the father being uninvolved in child feeding, fathers’ lack of support for mothers’ participation in nutrition education classes, and parenting rules and conflicts. In addition, future work may need to directly explore Hispanic fathers’ views of their perceived role in child feeding and child eating practices, and preferences for how nutrition education is delivered. This is especially important with low-income parents who are reported to work long hours, work overtime, or do not have structured work schedules.59 Further, examining fathers’ intentions and motivators for program adherence may increase the likelihood of males’ participation in health promotion and wellness programs.

The study had limitations. Mothers’ perceptions of fathers’ roles or support in family eating/PA may be influenced by factors not examined here, such as the quality of the marital relationship. Marital satisfaction is reportedly related to partners’ social, emotional, and physical well-being, and perceptions of social support.60–62 Socio-demographic characteristics of fathers were not collected. Acculturation was not assessed with a specific measurement tool. Qualitative studies are intended for generation of hypothesis, not for confirmation of findings. Mothers’ views of fathers’ healthy behaviors at home in this relatively small sample of 55 mothers cannot be generalized to the Hispanic families in Oklahoma City. Finally, maternal responses about healthy behaviors may have been influenced by social desirability bias, as this phenomenon has been reported elsewhere.63,64

CONCLUSIONS

Findings revealed that Hispanic mothers disagreed with fathers’ preferences about food preparation methods in the home. However, mothers perceived that fathers participate in behaviors that promote healthy behaviors in the home (i.e., supporting their children’s healthy eating and PA), yet also discourage healthy behavior in the home (i.e., being indulgent, using food as reward, and bringing high-calorie foods into the home). Gaining an understanding of the distinctive parenting behaviors and/or roles of Hispanic fathers versus mothers could identify new ways to involve parents in behaviors that support a healthy home. Future qualitative studies may consider exploring minority fathers’ and mothers’ views of aspects of the home environment, such as support for partner participation in nutrition education, family engagement in PA, frequency and structure of family meals, and perceived ability to promote healthy dietary and PA behaviors early in life through purposeful actions and activities. Examples include being a positive role model and encouraging healthy behaviors, or responsibility and beliefs about supporting the availability of healthy foods in the home. Such studies may identify similar and opposing views of fathers and mothers regarding keeping a healthy home. This information would be important for future hypothesis testing of the type of contribution that each parent may make in the home.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: Funding for this study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM104938 to the Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Resources (Dr. Lora pilot project awardee). The study sponsor did not have a role in the study design, collection and analysis of data, interpretation of findings, or manuscript writing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA. Model of the home food environment pertaining to childhood obesity. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(3):123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans A, Chow S, Jennings R, et al. Traditional foods and practices of Spanish-speaking Latina mothers influence the home food environment: implications for future interventions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(7):1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dave JM, Evans AE, Pfeiffer KA, Watkins KW, Saunders RP. Correlates of availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables in homes of low-income Hispanic families. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(1):97–108. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vepsalainen H, Mikkila V, Erkkola M, et al. Association between home and school food environments and dietary patterns among 9–11-year-old children in 12 countries. Int J Obes Suppl. 2015;5(Suppl 2):S66–S73. doi: 10.1038/ijosup.2015.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santiago-Torres M, Adams AK, Carrel AL, LaRowe TL, Schoeller DA. Home food availability, parental dietary intake, and familial eating habits influence the diet quality of urban Hispanic children. Child Obes. 2014;10(5):408–415. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Story M, Wall M. Associations between parental report of the home food environment and adolescent intakes of fruits, vegetables and dairy foods. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(1):77–85. doi: 10.1079/phn2005661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vereecken C, Haerens L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L. The relationship between children's home food environment and dietary patterns in childhood and adolescence. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(10A):1729–1735. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couch SC, Glanz K, Zhou C, Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Home food environment in relation to children's diet quality and weight status. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(10):1569–1579. e1561. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madsen KA, McCulloch CE, Crawford PB. Parent modeling: perceptions of parents' physical activity predict girls' activity throughout adolescence. J Pediatr. 2009;154(2):278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zecevic CA, Tremblay L, Lovsin T, Michel L. Parental Influence on Young Children's Physical Activity. Int J Pediatr. 2010;2010:468526. doi: 10.1155/2010/468526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner BJ, Navuluri N, Winkler P, Vale S, Finley E. A qualitative study of family healthy lifestyle behaviors of Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant fathers and mothers. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(4):562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez SM, Rhee K, Blanco E, Boutelle K. Maternal attitudes and behaviors regarding feeding practices in elementary school-aged Latino children: a pilot qualitative study on the impact of the cultural role of mothers in the US-Mexican border region of San Diego, California. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(2):230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flores G, Maldonado J, Duran P. Making tortillas without lard: Latino parents' perspectives on healthy eating, physical activity, and weight-management strategies for overweight Latino children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(1):81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor TM, Cerin E, Hughes SO, et al. What Hispanic parents do to encourage and discourage 3–5 year old children to be active: a qualitative study using nominal group technique. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:93. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon B, Pena MM, Taveras EM. Lifecourse approach to racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(1):73–82. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity: the role of early life risk factors. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(8):731–738. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallan KM, Daniels LA, Nothard M, et al. Dads at the dinner table. A cross-sectional study of Australian fathers' child feeding perceptions and practices. Appetite. 2014;73:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall L, Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Burrows TL, Lubans DR, Callister R. Children's intake of fruit and selected energy-dense nutrient-poor foods is associated with fathers' intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(7):1039–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vollmer RL, Adamsons K, Gorin A, Foster JS, Mobley AR. Investigating the Relationship of Body Mass Index, Diet Quality, and Physical Activity Level between Fathers and Their Preschool-Aged Children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(6):919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer KW, Hearst MO, Escoto K, Berge JM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parental employment and work-family stress: associations with family food environments. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(3):496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayala G, Ibarra L, Arredondo E, et al. Promoting Healthy Eating by Strengthening Family Relations: Design and Implementation of the Entre Familia: Reflejos de Salud Intervention. In: Ronit Elk, Landrine H., editors. Cancer Disparities: Causes and Evidence-Based Solutions. 1. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company LLC; 2012. pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrer RL, Cruz I, Burge S, Bayles B, Castilla MI. Measuring capability for healthy diet and physical activity. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):46–56. doi: 10.1370/afm.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villarreal R, Blozis SA, Widaman KF. Factorial invariance of a pan-Hispanic familism scale. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2005;27(4):409–425. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 Through 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284–2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotler P, Roberto N, Lee N. Social Marketing: Improving the Quality of Life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siegel M, Doner Lotenberg L. Marketing public health: Strategies to promote social change. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Los Angeles: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greater Oklahoma City Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. [Accessed January 3, 2017];Oklahoma City Hispanic Population. http://okchispanicchamber.org/pages/LivinginOklahomaCity/

- 30.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.USDA Food and Nutrition Service. [Accessed January 3, 2017];Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Eligibility. http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility.

- 32.Chavez-Martinez A, Cason KL, Mayo R, Nieto-Montenegro S, Williams JE, Haley-Zitin V. Assessment of predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors toward food choices and healthy eating among Hispanics in South Carolina. Top Clin Nutr. 2010;25(1):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garbutt JM, Leege E, Sterkel R, Gentry S, Wallendorf M, Strunk RC. What are parents worried about? Health problems and health concerns for children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51(9):840–847. doi: 10.1177/0009922812455093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford PB, Gosliner W, Anderson C, et al. Counseling Latina mothers of preschool children about weight issues: suggestions for a new framework. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(3):387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson CM, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. It's all about the children: a participant-driven photo-elicitation study of Mexican-origin mothers' food choices. BMC Womens Health. 2011;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mier N, Ory MG, Medina AA. Anatomy of culturally sensitive interventions promoting nutrition and exercise in Hispanics: a critical examination of existing literature. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(4):541–554. doi: 10.1177/1524839908328991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marin G, VanOss Marin B. Research with Hispanic Populations. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mainous AG, 3rd, Diaz VA, Carnemolla M. Factors affecting Latino adults' use of antibiotics for self-medication. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(2):128–134. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.02.070149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miles MB, Huberman AM, editors. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuy Castellanos D, Downey L, Graham-Kresge S, Yadrick K, Zoellner J, Connell CL. Examining the diet of post-migrant Hispanic males using the precede-proceed model: predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling dietary factors. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(2):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cespedes E, Andrade GO, Rodriguez-Oliveros G, et al. Opportunities to Strengthen Childhood Obesity Prevention in Two Mexican Health Care Settings. Int J Pers Cent Med. 2012;2(3):496–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhoads-Baeza ME, Reis J. An exploratory mixed method assessment of low income, pregnant Hispanic women’s understanding of gestational diabetes and dietary change. Health Educ J. 2010 0017896910386287. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Triandis HCMG, Betancourt H, Lisnsky J, Chang B. Dimensions of familism among Hispanic and mainstream Navy recruits. Champaing, IL: University of Illinois; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLaughlin EA, Campos-Melady M, Smith JE, et al. The role of familism in weight loss treatment for Mexican American women. J Health Psychol. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1359105316630134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kornides ML, Nansel TR, Quick V, et al. Associations of family meal frequency with family meal habits and meal preparation characteristics among families of youth with type 1 diabetes. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(3):405–411. doi: 10.1111/cch.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayala GX, Baquero B, Klinger S. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: implications for future research. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(8):1330–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cruz RA, Gonzales NA, Corona M, et al. Cultural dynamics and marital relationship quality in Mexican-origin families. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28(6):844. doi: 10.1037/a0038123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galanti G-A. The Hispanic family and male-female relationships: An overview. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14(3):180–185. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tschann JM, Gregorich SE, Penilla C, et al. Parental feeding practices in Mexican American families: initial test of an expanded measure. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hennessy E, Hughes SO, Goldberg JP, Hyatt RR, Economos CD. Parent-child interactions and objectively measured child physical activity: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:71. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dawson-Hahn EE, Fesinmeyer MD, Mendoza JA. Correlates of Physical Activity in Latino Preschool Children Attending Head Start. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2015;27(3):372–379. doi: 10.1123/pes.2014-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Musher-Eizenman DR, Kiefner A. Food parenting: a selective review of current measurement and an empirical examination to inform future measurement. Child Obes. 2013;9(Suppl):S32–S39. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lora KR, Hubbs-Tait L, Ferris AM, Wakefield D. African-American and Hispanic children's beverage intake: Differences in associations with desire to drink, fathers' feeding practices, and weight concerns. Appetite. 2016;107:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ranjit N, Evans AE, Springer AE, Hoelscher DM, Kelder SH. Racial and ethnic differences in the home food environment explain disparities in dietary practices of middle school children in Texas. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ding D, Sallis JF, Norman GJ, et al. Community food environment, home food environment, and fruit and vegetable intake of children and adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(6):634–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morgan PJ, Lubans DR, Callister R, et al. The 'Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids' randomized controlled trial: efficacy of a healthy lifestyle program for overweight fathers and their children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35(3):436–447. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Devine CM, Farrell TJ, Blake CE, Jastran M, Wethington E, Bisogni CA. Work conditions and the food choice coping strategies of employed parents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(5):365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carr D, Freedman VA, Cornman JC, Schwarz N. Happy Marriage, Happy Life? Marital Quality and Subjective Well-Being in Later Life. J Marriage Fam. 2014;76(5):930–948. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holt-Lunstad J, Birmingham W, Jones BQ. Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):239–244. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9018-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allen JO, Griffith DM, Gaines HC. "She looks out for the meals, period": African American men's perceptions of how their wives influence their eating behavior and dietary health. Health Psychol. 2013;32(4):447–455. doi: 10.1037/a0028361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hebert JR, Clemow L, Pbert L, Ockene IS, Ockene JK. Social desirability bias in dietary self-report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(2):389–398. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller TM, Abdel-Maksoud MF, Crane LA, Marcus AC, Byers TE. Effects of social approval bias on self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2008;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]