Abstract

Exposure to smoking-associated environmental cues during smoke cessation elicits self-reported urge/craving to smoke, which precipitates relapse even after prolonged abstinence. Incubation of cue-induced cigarettes craving during abstinence has been observed in human smokers recently. The present studies assessed cue-induced nicotine-seeking behavior under different withdrawal conditions in rats with a history of nicotine self-administration. We found that non-reinforced operant responding during cue-induced nicotine seeking after different periods of withdrawal from nicotine exhibited an inverted U-shaped curve, with higher levels of responding after 7–21 days of withdrawal than those after 1-day withdrawal. Cue-induced nicotine seeking responding is long-lasting and persists even after 42 days of forced withdrawal in the home cages. Interestingly, repeated testing of cue-induced nicotine seeking at different withdrawal time points (1, 7, 14, 21 and 42 days) in the same individual alleviated responding as compared with the between-subjects assessment. Furthermore, extinction training during nicotine withdrawal significantly decreased cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior. Together, profound time-dependent incubation of cue-induced craving in nicotine-experienced rats were observed. In addition, repeated cue exposure or extinction training decreases cue-induced craving. The demonstration of incubation of nicotine craving phenomenon in both rat and human studies provides support for the translational potential of therapeutic targets for relapse uncovered through mechanism studies in rats.

Keywords: nicotine, cue-induced nicotine seeking, withdrawal, extinction, self-administration

INTRODUCTION

Relapse to smoking in abstinent smokers is a major hurdle in the promotion of smoking cessation (Agboola et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2004; Shiffman et al., 2008). The successful abstinence rates are low even after treatment with the available smoking cessation aids such as nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion and varenicline (Anthenelli et al., 2016; Jorenby et al., 2006; Perkins et al., 2010). Accumulating clinical studies show that smoking cessation is associated with increased craving, which has been indicated to be a negative predictor of abstinence (Doherty et al., 1995; Powell et al., 2010). Self-reported baseline (non-provoked) craving starts to increase within the first hours of abstinence (Brown et al., 2013; Bujarski et al., 2015), peaks within the first few days and then subsides gradually (Tsaur et al., 2015). This baseline craving may contribute to relapse to smoking occurred soon after quitting. However, smoking-cue-induced (provoked) cigarette craving time-dependently increases within the first 35 days of abstinence despite progressively decreasing baseline craving and withdrawal symptoms (Bedi et al., 2011). Although the majority of smokers relapse within the first weeks of abstinence, relapse can occur even after prolonged abstinence (Garvey et al., 1992). The conditioned-craving induced by smoking-associated cue may be an important factor underlying this time-delayed relapse (Bedi et al., 2011).

In the preclinical laboratory settings, the motivational properties of stimuli that had previously been associated with the reinforcing effects of nicotine are assessed in the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking procedure (Chiamulera, 2005; Epstein et al., 2006). While most animal studies on nicotine seeking used a reinstatement model that involves extinction of the nicotine-reinforced responding, in most cases extinction is not a condition experienced by human smokers before relapse conditions occur. The incubation of craving model specifically assesses drug craving after withdrawal without extinction training (Grimm et al., 2001). Time-dependent increases in cue-induced drug seeking have been observed after withdrawal from cocaine (Grimm et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2004a), heroin (Airavaara et al., 2011; Shalev et al., 2001), alcohol (Bienkowski et al., 2004), and methamphetamine (Shepard et al., 2004) self-administration in rats. One of the common findings in these studies is the significant long-lasting drug craving after forced abstinence. Specifically, persistence of drug craving was observed after 180 days of cocaine withdrawal (Grimm et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2004a; Lu et al., 2004b), after 66 days of heroin withdrawal (Shalev et al., 2001; Shiffman et al., 2008), after 56 days of alcohol withdrawal (Bienkowski et al., 2004), or after 51 days of methamphetamine withdrawal (Shepard et al., 2004) in rats.

The impact of the nicotine withdrawal period on vulnerability to nicotine seeking induced by re-exposure to nicotine-associated cues is largely unknown. Abdolahi et al observed cue-induced nicotine seeking after 1 day or 7 days of forced withdrawal in rats (Abdolahi et al., 2010). They found that the 7-day withdrawal group had higher responding during the reinstatement testing than the 1-day withdrawal group. Compared with the studies of other drugs of abuse as indicated above, the time frame used in this study is very short. Bedi et al examined the time course (on Days 7, 14 and 35) of smoking-cue-induced craving in humans after smoking cessation. They found that cue-induced cigarette craving increased with abstinence, with greater craving observed in the 35-day abstinence group than in the 7-day abstinence group. Interestingly, when the participants received repeated cue exposure on Days 7, 14 and 35, these individuals exhibited weaker cue-induced craving on Day 35 than those who underwent single cue exposure on the final abstinence Day 35. To characterize the dynamic changes of cue-induced nicotine craving over the course of withdrawal in rats, we first assessed cue-induced nicotine seeking behavior over different periods (1, 7, 14, 21 or 42 days) of forced withdrawal from nicotine self-administration by using a between-subjects assessment in rats (Experiment 1a). Because the clinical study indicates that repeated cue exposure may cause some extinction of the conditioned response in the within-subject group (Bedi et al., 2011), we also assessed repeated testing of cue-induced nicotine seeking at different forced withdrawal time points (1, 7, 14, 21 and 42 days) in the same group of rats (within-subjects assessment; Experiment 1b). Cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior that involves extinction training after self-administration is the most commonly used procedure in animal studies for the evaluation of the motivational properties of nicotine-associated cues (Chiamulera, 2005; Epstein et al., 2006). We predicted that rats that undergo extinction training during withdrawal may exhibit lower cue-induced craving as compared with those observed in the forced withdrawal rats because extinction training suppresses conditioned behavioral responses through learning of new contextual relationships (Bouton, 2002). To test this hypothesis, we assessed cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking over different periods of withdrawal with extinction training (between-subjects assessment; Experiment 2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Male Wistar rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC), weighing 300–350 g at the start of the experiments, were housed two per cage on a reverse 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium. All behavioral testing occurred during the dark phase. The rats had unrestricted access to water except during testing and were food-restricted to 22–24 g of rat chow per day, provided to them at least 1 h after the end of behavioral testing. The animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the experiments were approved by the University of California, San Diego, Animal Care and Use Committee. Naive rats were used for each experiment described below.

Apparatus

Standard operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) each housed in a sound-attenuated box were used. In each chamber, the right side wall contained two metal retractable levers mounted 6.5 cm above the metal grid floor of the chamber with a stimulus light located above each lever. A food receptacle was located between the two levers. A house light was located on the left side wall. Food was dispensed via a food dispenser. Intravenous infusions were delivered by an infusion pump (Razel, Scientific Instruments, Stamford, CT) through Tygon tubing protected by a spring lead that was connected on one end to a swivel to allow free movement of the animal and on the other end to the catheter base mounted in the midscapular region of the animal.

Nicotine self-administration

Rats were first trained to lever press for food (45 mg Noyes standard food pellets) during 1 h sessions daily. Responding on the active lever resulted in the delivery of food pellets. Responses on the inactive lever were recorded but had no consequences. The delivery of a food pellet was earned by responding five times on the active lever. After 5–7 days of food self-administration training, rats were surgically prepared with an intravenous catheter that was inserted into the right jugular vein under isoflurane (1–3% in oxygen) anesthesia as described previously (Liechti et al., 2007). After one week recovery from intravenous catheter implantation, rats were allowed to self-administer nicotine (0.03 mg/kg free base/infusion in a volume of 0.1 ml over 1 s) during 1 h sessions daily. (-)Nicotine hydrogen tartrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in saline, and the pH was adjusted to 7.4. The nicotine infusion was delivered by an infusion pump and was earned by responding five times on the active lever (FR5TO20s). The infusions were paired with a cue light located above the active lever, which was lit simultaneously with the initiation of the food reward and remained illuminated throughout the 20 s time-out period, during which responding was recorded but not reinforced. Responses on the inactive lever were recorded but had no consequences. Each session began with the insertion of the levers and the illumination of a houselight that remained on for the entire session. At the end of each session, the houselight was turned off and the levers retracted. Rats were considered to have acquired stable self-administration when they pressed the active lever more than twice the number of times they pressed the inactive lever and received a minimum of six infusions/1 h session, with less than 20% variance in the number of infusions earned per session over three consecutive sessions. Rats were allowed to self-administer nicotine for 3 weeks (5 days/week).

Withdrawal with extinction

The experimental conditions of the 1-hour daily extinction training were identical to those of the nicotine self-administration procedures described above, with the exception that the responses on the active lever will have no consequences (i.e., no cue-light presentation, no nicotine infusion, no syringe pump activation and noise).

Withdrawal without extinction

Rats were housed in home cages in the animal facility and handled every other day.

Cue-induced nicotine seeking

Nicotine seeking sessions were initiated by the presentation of a single noncontingent cue light (20 s), followed by extension of the active and inactive levers into the testing chamber. Responses on the active lever led to contingent presentations of the discrete cue light and the delivery of a saline infusion (0.1 ml/ 1 s) to maximize the drug-associated cues that were experienced during the drug seeking sessions. Cue-induced responding was measured as the number of responses on the active lever throughout the test session, including during the timeout periods. Responses on the inactive lever were recorded but had no consequences.

Experimental designs

Experiment 1: Cue-induced nicotine-seeking behavior after withdrawal without extinction

Two different experimental designs were used (see the timeline of experimental procedures in Figure 1). Experiment 1a used a between-subjects assessment. After establishing stable nicotine self-administration, rats were randomly assigned to one of the five groups (n=8–9/group), counterbalanced for number of nicotine infusions earned per session. Different groups of rats then underwent different periods of withdrawal from nicotine (1, 7, 14, 21 or 42 days) in home cages before the cue-induced nicotine seeking testing. Experiment 1b used a within-subjects assessment. After establishing stable nicotine self-administration, a group of rats (n=8) underwent withdrawal from nicotine in home cages and were tested repeatedly for cue-induced nicotine seeking on Days 1, 7, 14, 21 and 42 after withdrawal from nicotine self-administration.

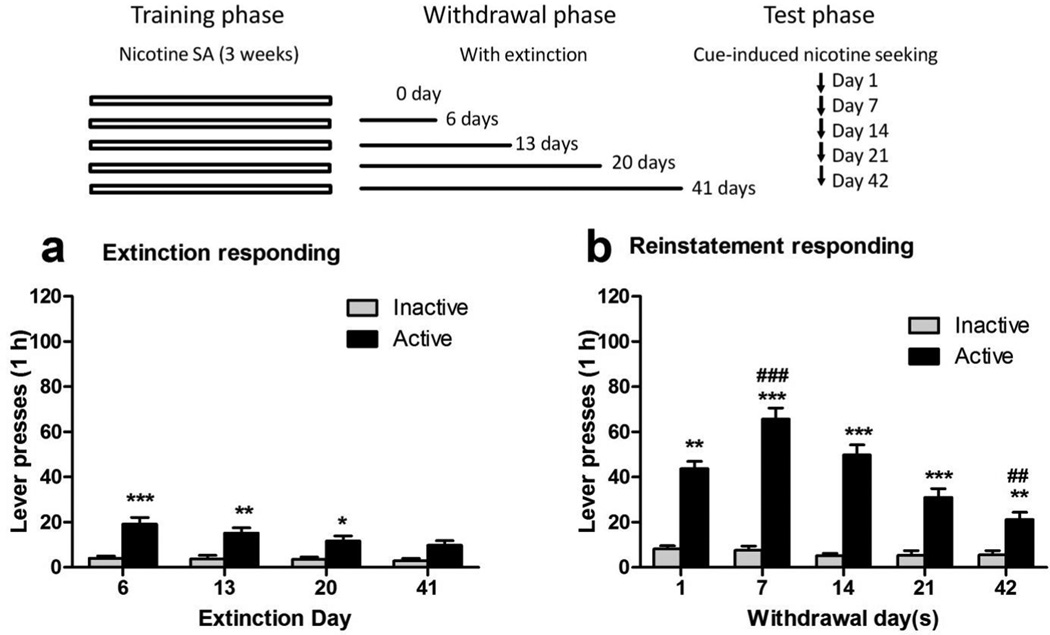

Figure 1.

Cue-induced relapse of nicotine-seeking behavior after withdrawal without extinction in rats. (a) Between-subjects assessment. Total active and inactive lever presses in cue-induced reinstatement tests after withdrawal from nicotine self-administration for 1 (n=9), 7 (n=9), 14 (n=8), 21 (n=8) or 42 (n=9) days. (b) Within-subject assessment. Total active and inactive lever presses in cue-induced reinstatement tests after withdrawal from nicotine self-administration for 1, 7, 14, 21 and 42 days (n=8). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with inactive lever presses at the same time points. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, compared with active lever presses in 1-day withdrawal.

Experiment 2: Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior after withdrawal with extinction

A between-subjects assessment was used for this experiment (see the timeline of experimental procedures in Figure 2). After establishing stable nicotine self-administration, rats were randomly assigned to one of the five extinction groups (n=8–10/group), counterbalanced for number of nicotine infusions earned per session. Different groups of rats then underwent different periods of extinction training (i.e., 0, 6, 13, 20 or 41 consecutive daily extinction training). Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking testing was conducted 1 day after the last extinction phase (For the 0 day of extinction group, nicotine seeking was tested 1 day after the last self-administration session). Therefore, the reinstatement testing in different groups was conducted on days 1, 7, 14, 21 and 42 after withdrawal from nicotine self-administration, which was correspondent with the nicotine seeking testing timeline in Experiment 1.

Figure 2.

Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior after withdrawal with extinction in rats. (a) Total active and inactive lever presses in the last extinction session after 6 (n=10), 13 (n=8), 20 (n=8) or 41 (n=9) consecutive daily extinction training. (b) Total active and inactive lever presses in cue-induced reinstatement tests after 1 (n=10), 7 (n=10), 14 (n=8), 21 (n=8) or 42 (n=9) days of withdrawal with extinction training. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with inactive lever presses at the same time points. ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, compared with active lever presses after 1 day of withdrawal with extinction.

Statistical analyses

Data in Experiments 1a and 2 were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Withdrawal period as the between-subjects factor. Data in Experiment 1b were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with repeated-measures, with Withdrawal period as the within-subjects factor.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Cue-induced nicotine-seeking behavior after withdrawal without extinction

Time-dependent changes in incubation of cue-induced nicotine seeking were observed in either between-subjects or within-subjects assessment (Fig. 1). However, the patterns were different in these two experiments.

When cue-induced nicotine seeking at different withdrawal periods (1, 7, 14, 21 or 42 days) were tested in different groups of rats (between-subjects assessment; Fig. 1a), the responding on the previous active lever exhibited an inversed U-shaped curve, with maximal responding observed in the 7-day withdrawal group. Similar levels of responding were also observed in the 14-day and 21-day, but not the 42-day, withdrawal groups. Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of Withdrawal period: F4,76 = 6.07, p < 0.001, Lever: F1,76 = 155.7, p < 0.001, and Withdrawal period × Lever interaction: F4,76 = 5.04, p < 0.01. The post hoc tests revealed a significant increase in active lever responding in 7-day (p < 0.01), 14-day (p < 0.05), and 21-day (p < 0.05) withdrawal groups, but not in 42-day groups, as compared with the 1-day withdrawal group.

When cue-induced nicotine seeking at different withdrawal periods (1, 7, 14, 21 and 42 days) were tested in the same group of rats (within-subjects assessment; Fig. 1b), the maximal responding on the active lever was also observed after 7-day withdrawal. Then there was a time-dependent decrease in responding after 14, 21 and 42 days of withdrawal. Two-way ANOVA with repeated-measures indicated a significant main effect of Withdrawal period: F4,56 = 13.65, p < 0.001, Lever: F1,56 = 56.35, p < 0.001, and Withdrawal period × Lever interaction: F4,56 = 10.97, p < 0.001. The post hoc tests revealed a significant increase in active lever responding after 7 days (p < 0.001) and 14 days (p < 0.05), but not after 21 or 42 days, of withdrawal as compared with the 1-day withdrawal group.

Experiment 2: Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior after withdrawal with extinction

Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior after different withdrawal with extinction periods were tested in different groups of rats (Fig. 2). Figure 2a presents the total active and inactive lever presses in the last extinction session after 6, 13, 20 or 41consecutive daily extinction training. There was a time-dependent decrease in active lever responding after prolonged extinction training. Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of Extinction period: F3,62 = 2.84, p < 0.05, and Lever: F1,62 = 53.93, p < 0.001. Figure 2b presents the total active and inactive lever presses during cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking testing. The maximal responding on the active lever was also observed after 7-day withdrawal with extinction. Then there was a time-dependent decrease in responding after 14, 21 and 42 days of withdrawal with extinction. Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of Extinction period: F4,80 = 17.41, p < 0.001, Lever: F1,80 = 33.3, p < 0.001, and Extinction period × Lever interaction: F4,80 = 14.62, p < 0.001. The post hoc tests revealed a significant increase in active lever responding after 7 days (p < 0.001), but not after 14 or 21 days, of withdrawal with extinction, compared with the 1-day withdrawal group. Moreover, there was a significant decrease in active lever responding after 42 days (p < 0.01) of withdrawal with extinction, compared with the 1-day withdrawal group.

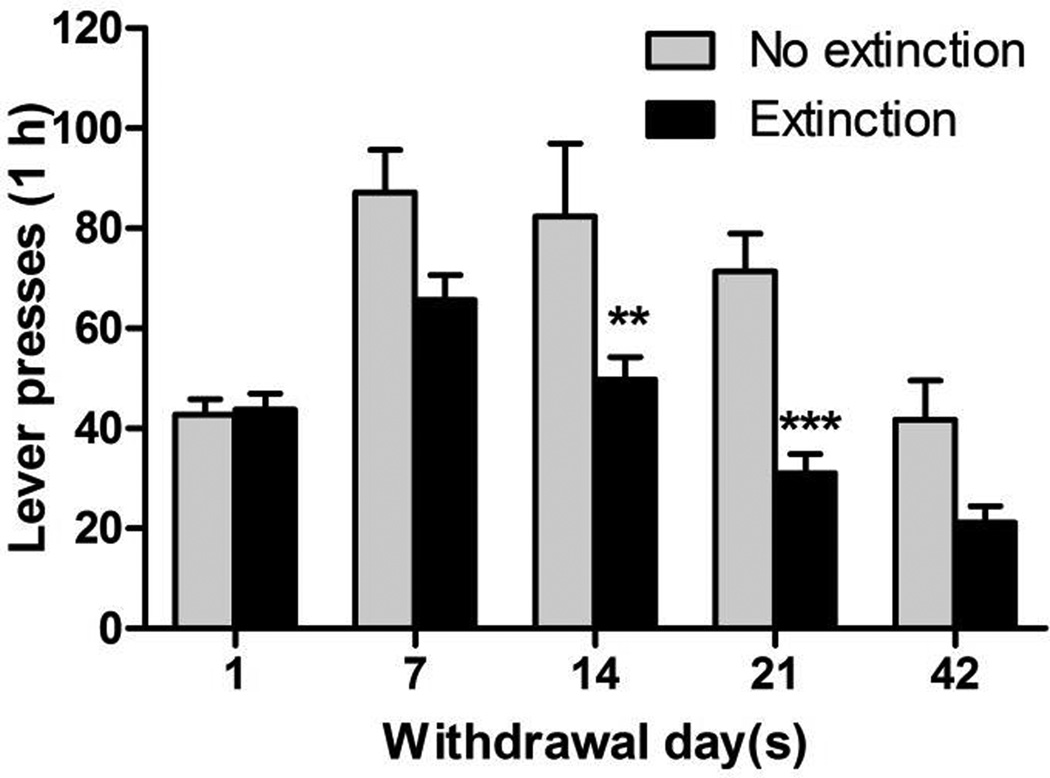

We then compared the active lever responding in Fig. 1a and Fig. 2b to indicate the difference between extinction training and forced withdrawal in the home cage on incubation of cue-induced craving (Fig. 3). Compared with withdrawal without extinction groups, there was a significant decrease in responding in the withdrawal with extinction groups, indicating that extinction training decreased nicotine craving induced by exposure to nicotine-associated environmental cues. Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of Withdrawal Condition: F1,78 = 28.32, p < 0.001, Withdrawal Period: F4,78 = 14.5, p < 0.001, and Withdrawal Condition × Withdrawal Period interaction: F4,78 = 2.69, p < 0.05. The post hoc tests revealed a significant decrease in active lever responding after 14 days and 21 days (p < 0.001), but not after 7 or 42 days, of withdrawal with extinction, compared with the responding in the withdrawal without extinction groups at the corresponding time points.

Figure 3.

Cue-induced nicotine-seeking responding after withdrawal with or without extinction training. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, difference between withdrawal without extinction and withdrawal with extinction.

DISCUSSION

The present studies show the profound time-dependent changes in cue-induced nicotine-seeking behavior under different withdrawal conditions in nicotine-experienced rats. Non-reinforced operant responding during cue-induced nicotine seeking after different periods of withdrawal from nicotine in the home cages exhibited an inverted U-shaped curve, with higher levels of responding after 7–21 days of withdrawal than those after 1-day withdrawal. Cue-induced drug seeking responding after 42 days of forced withdrawal in the home cages was lower than those after 7–21 days of withdrawal, but was similar as those after 1 day of withdrawal, suggesting that nicotine associated cue-induced nicotine seeking is long-lasting and persists. Interestingly, repeated testing of cue-induced nicotine seeking at different withdrawal time points in the same individual (within-subjects assessment) alleviated subsequent reinstatement responding as compared with those observed in the between-subjects assessment. Furthermore, extinction training during nicotine withdrawal significantly decreased cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior.

Time-dependent changes of incubation of nicotine craving

Conditioned motivational effects of smoking-associated environmental stimuli (e.g., the sight and smell of a lit cigarette or contexts within which smoking occurs) contribute to the maintenance of tobacco smoking (Rose, 2006; Rose et al., 1993), and play a critical role in eliciting drug seeking and relapse to drug taking in humans (Childress et al., 1999; O'Brien et al., 1998; O'Brien and McLellan, 1996). Similarly, specific environments in which individuals smoke can generate strong self-reported urges or craving to smoke (Conklin, 2006). Interestingly, a recent human study indicated that this cue-induced craving increased with abstinence duration in cigarette smokers, with higher level of craving after 35-day abstinence than that after 7-day abstinence (Bedi et al., 2011).

The property of nicotine to facilitate the formation of strong associations between environmental cues and nicotine taking has been observed reliably in animals as well. In rats, environmental cues associated with nicotine delivery enhanced both the acquisition and maintenance of nicotine self-administration (Caggiula et al., 2001, 2002). Furthermore, contingent presentation of nicotine-associated conditioned stimuli prolonged the extinction of nicotine seeking in rats (Caggiula et al., 2001; Donny et al., 1999). In addition, nicotine-seeking behavior can be reinstated by response-contingent presentation of nicotine-paired stimuli (LeSage et al., 2004; Liechti et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2006).

Here we showed that nicotine associated-cue elicited nicotine-seeking behavior even after 42 days of forced withdrawal at home cages, with responding at similar levels as that after 1 day of withdrawal (Fig. 1a), indicating that cue-induced craving is long-lasting in rats with a history of nicotine self-administration. This finding is consistent with previous study showing that cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking was observed at 41 days after nicotine self-administration (Liu et al., 2008). Moreover, the non-reinforced operant responding was higher after 7, 14 or 21 days of withdrawal than those after 1 day or 42 days of withdrawal, suggesting an inverted U-shaped curve of incubation of nicotine craving in rats. Interestingly, while this manuscript was in review, a report of similar results was published by Funk et al which showed that rat exhibited maximal nicotine-seeking responding on withdrawal day 14 compared to days 1, 7 or 28 (Funk et al., 2016). The similar findings in two independent studies conducted in different laboratories at the similar time provide strong evidence demonstrating the characteristic time-dependent changes of incubation of nicotine craving in rats, a reliable phenomenon that can be detected repeatedly. This incubation of craving phenomenon in rats is congruent with incubation of cue-induced cigarette craving in human smokers as discussed above (Bedi et al., 2011). We noticed that cue-induced craving increases within 35 days of abstinence in smokers, while our study shows an inverted U-shaped curve over 42 days of forced withdrawal in nicotine-experienced rats. Several possibilities may contribute to the different patterns of craving across time in these two studies. First, in human study participants smoked cigarette for years and were tested for cue-induced craving over 35 days of abstinence, while in rat study rats self-administered nicotine for 3 weeks and tested for cue-induced craving over 42 days of withdrawal. Second, human cigarette smoking has more complicated environmental cues than those in nicotine self-administration rats in the laboratory settings. Interestingly, it seems that the inverted U-shaped function of drug craving is a general phenomenon observed after a prolonged withdrawal from different drugs of abuse in rats. For example, maximal cocaine-seeking responding was observed after Day 30 and Day 60 of withdrawal from cocaine self-administration, followed by decreased responding after Day 180 of withdrawal (Grimm et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2004a; Lu et al., 2004b). Moreover, maximal drug seeking was reported after Days 6 and Day 12 of heroin withdrawal in rats, followed by decreased responding after Day 25 and Day 66 of withdrawal (Shalev et al., 2001). In addition, maximal responding was observed after Days 28 of withdrawal from alcohol self-administration, followed by decreased responding after Day 56 of withdrawal (Bienkowski et al., 2004). It is possible that similar to the baseline (non-provoked) craving, smoking-cue-provoked cigarette craving may subside slowly over prolonged abstinence. In support of this hypothesis, meta-analyses of data showed that relapse rate was 17% in weeks 9–12 post abstinence versus 8% at week 52 post abstinence (Agboola et al., 2015), suggesting a gradually decreased craving over time with long-term smoking cessation. Thus, to fully characterize the longitudinal changes in cue-induced cigarette craving after abstinence in humans, a prolonged period (beyond 35 days of abstinence) may be necessary.

It is worth to mention that to examine the translational potential of this model, the experimental design we used here in rats is very similar to that used in human studies. In human studies, smokers abstained from smoking for different periods of time before they were exposed to a cue session on the final abstinence day without any extinction training (Bedi et al., 2011). In the present study, the rats also underwent different periods of forced withdrawal before they were exposed to cues previously associated with nicotine self-administration, without extinction before cue session. The demonstration of incubation of cue-induced nicotine craving phenomenon in both human and rat studies provides support for the translational potential of therapeutic targets for relapse uncovered through mechanism studies in rats. Furthermore, this time-dependent changes in cue-induced drug seeking in nicotine-experienced rats are in line with previous findings in rats after withdrawal from other drugs of abuse, such as cocaine (Grimm et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2004a), heroin (Shalev et al., 2001; Shiffman et al., 2008), alcohol (Bienkowski et al., 2004), and methamphetamine (Shepard et al., 2004) self-administration. Thus, incubation of craving is a general phenomenon for addiction to most drugs of abuse, although different drugs of abuse may exhibit different time-dependent patterns as discussed above.

It should be noted that the negative affective and somatic symptoms of acute nicotine withdrawal and self-reported baseline (non-provoked) craving peaks within the first few days and then subsides in smokers (Bedi et al., 2011; Tsaur et al., 2015). Similarly, in the preclinical studies, nicotine withdrawal-induced aversive affective signs, such as depression-like anhedonia and anxiety-like behavior, and somatic signs peaks 1–2 days after withdrawal from nicotine and then subsides quickly in rats (Kenny et al., 2003; Skjei and Markou, 2003). It has been demonstrated that early withdrawal symptoms and baseline craving contribute to the high rates of relapse within the first weeks of abstinence (Doherty et al., 1995; Powell et al., 2010). However, relapse can occur even after prolonged abstinence when these nicotine withdrawal symptoms and baseline craving have abated (Garvey et al., 1992). On the contrary, the conditioned-craving induced by nicotine-associated cue increased with longer withdrawal and persisted for a long period, as shown in the present study and others, therefore may be an important factor underlying this time-delayed relapse (Bedi et al., 2011). In addition, it has been indicated that the shifts from negative affect to positive affect and deficits in response inhibition at longer time points during smoking cessation may also contribute to relapse after a period of abstinence (Bujarski et al., 2015; Tsaur et al., 2015). The neurobiological mechanisms underlying incubation of nicotine craving is largely unknown. Notably, more Fos positive neurons in different brain areas (e.g., amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens) were detected after 14 days of nicotine withdrawal than after 1 day in rats. Moreover, selective inactivation of these Fos-positive neurons in the central amygdala decreased incubation of nicotine seeking (Funk et al., 2016). Human imaging studies indicate that exposure to nicotine-associated cues increased BOLD activity in the amygdala (McClernon et al., 2007; Sutherland et al., 2013). Thus, it seems that the amygdala, a brain site that is critically involved in the incentive motivations aspects of drug-associated cues and drug seeking, plays an important role in incubation of nicotine craving.

Effects of extinction on cue-induced nicotine seeking

Interestingly, incubating of cue-induced craving was weaker in within-subjects assessment than in between-subjects assessment. In within-subjects assessment, only 7-day and 14-day withdrawal showed increased nicotine seeking responding as compared to 1-day withdrawal (Fig. 1b), while 21-day withdrawal exhibited the similar responding as 1-day withdrawal. The weaker craving observed in within-subject assessment in rats is consistent with the report in humans which showed that when the participants received repeated cue exposure on Days 7, 14 and 35, these individuals exhibited weaker cue-induced craving on Day 35 than those who underwent single cue exposure on the final abstinence Day 35 (Bedi et al., 2011). One possible explanation for this observation is that some extinction of the conditioned responses occurs when the subjects are exposed repeatedly to nicotine-associated cues (including the contextual and discrete cues) during the drug seeking tests at different withdrawal periods. That is, repeated exposure to cues decreases conditioned motivational effects of nicotine-associated environmental stimuli, therefore attenuating cue-induced craving.

This notion is further supported by the findings in the experiments assessing cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior after different periods of withdrawal with extinction training (Fig. 2a). Similar to reinstatement after withdrawal without extinction training, nicotine seeking responding induced by discrete cue was higher in the 7-days extinction group than that observed in the 1-days extinction group, suggesting that incubation of craving phenomenon exists even under withdrawal with extinction condition. However, extended extinction significantly diminished cue-induced craving, as supported by the evidence that 14-day extinction group showed similar responding as 1-day group, and, most prominently, 42-day extinction group exhibited lower responding than 1-day group. These findings strongly suggest the inhibitory efficacy of extinction training on the motivational power of environmental cues previously associated with nicotine administration in rats. Extinction training is an inhibitory form of learning that suppresses conditioned behavioral responses through learning of new contextual relationships (Bouton, 2002, 2004; Rescorla, 2001). It should be note that rats were exposed to the contextual cue during the extinction training in the present study. So this training facilitates drug-context cue disassociation and extinction of nicotine contextual memory, while preserves drug-discrete cue association. It was the discrete cue-induced craving that was observed during the reinstatement tests in this experiment. Compared with cue-induced nicotine seeking after withdrawal without extinction training, the reinstatement responding after withdrawal with extinction training was significantly decreased (Fig. 2b), indicating a less craving state after extinction training. These findings may have significantly clinical implications, suggesting that cue-exposure therapy may be helpful to prolong abstinence and prevent relapse in drug dependent patients.

In sum, the present study demonstrated time-dependent changes in cue-induced nicotine seeking and the persistence of cue-induced craving in nicotine-experienced rats. In addition, repeated cue exposure or extinction training decreases cue-induced craving. Future research will elucidate the neurobiological substrates underlying incubation of cue-induced nicotine craving in rats. Furthermore, in addition to smoking-associated cues, re-exposure to cigarettes or stress also triggers relapse even after prolonged abstinence. Thus, future study will explore whether cravings induced by nicotine-priming or stressors also increase with extended periods of abstinence.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants 20KT-0046 and 24RT-0034 from Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP) and R21DA040195 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to XL.

AM has received contract research support from AstraZeneca and Forest Laboratories and an honorarium from AbbVie, Germany, during the last three years.

Footnotes

Authors Contribution: JL and KT carried out the experiments. XL performed data analysis. XL and AM designed the study. XL wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the content and approved the final version before submission.

Disclosures: The remaining authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdolahi A, Acosta G, Breslin FJ, Hemby SE, Lynch WJ. Incubation of nicotine seeking is associated with enhanced protein kinase A-regulated signaling of dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein of 32 kDa in the insular cortex. The European journal of neuroscience. 2010;31:733–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agboola S, McNeill A, Coleman T, Leonardi Bee J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking relapse prevention interventions for abstinent smokers. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2010;105:1362–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agboola SA, Coleman T, McNeill A, Leonardi-Bee J. Abstinence and relapse among smokers who use varenicline in a quit attempt-a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2015;110:1182–1193. doi: 10.1111/add.12941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airavaara M, Pickens CL, Stern AL, Wihbey KA, Harvey BK, Bossert JM, Liu QR, Hoffer BJ, Shaham Y. Endogenous GDNF in ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens does not play a role in the incubation of heroin craving. Addict Biol. 2011;16:261–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, St Aubin L, McRae T, Lawrence D, Ascher J, Russ C, Krishen A, Evins AE. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi G, Preston KL, Epstein DH, Heishman SJ, Marrone GF, Shaham Y, de Wit H. Incubation of cue-induced cigarette craving during abstinence in human smokers. Biological psychiatry. 2011;69:708–711. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Rogowski A, Korkosz A, Mierzejewski P, Radwanska K, Kaczmarek L, Bogucka-Bonikowska A, Kostowski W. Time-dependent changes in alcohol-seeking behaviour during abstinence. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;14:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological psychiatry. 2002;52:976–986. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learn Mem. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Hajek P, McRobbie H, Locker J, Gillison F, McEwen A, Beard E, West R. Cigarette craving and withdrawal symptoms during temporary abstinence and the effect of nicotine gum. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;229:209–218. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski S, Roche DJ, Sheets ES, Krull JL, Guzman I, Ray LA. Modeling naturalistic craving, withdrawal, and affect during early nicotine abstinence: A pilot ecological momentary assessment study. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2015;23:81–89. doi: 10.1037/a0038861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF. Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:515–530. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF. Environmental stimuli promote the acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:230–237. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamulera C. Cue reactivity in nicotine and tobacco dependence: a"multiple-action" model of nicotine as a primary reinforcement and as an enhancer of the effects of smoking-associated stimuli. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:74–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O'Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. The American journal of psychiatry. 1999;156:11–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA. Environments as cues to smoke: implications for human extinction-based research and treatment. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2006;14:12–19. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty K, Kinnunen T, Militello FS, Garvey AJ. Urges to smoke during the first month of abstinence: relationship to relapse and predictors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:171–178. doi: 10.1007/BF02246158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Mielke MM, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Maldovan V, Shupenko C, McCallum SE. Nicotine self-administration in rats on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;147:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s002130051153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Preston KL, Stewart J, Shaham Y. Toward a model of drug relapse: an assessment of the validity of the reinstatement procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D, Coen K, Tamadon S, Hope BT, Shaham Y, Le AD. Role of Central Amygdala Neuronal Ensembles in Incubation of Nicotine Craving. J Neurosci. 2016;36:8612–8623. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1505-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, Rosner B. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: a report from the Normative Aging Study. Addictive behaviors. 1992;17:367–377. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA, Shaham Y. Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature. 2001;412:141–142. doi: 10.1038/35084134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PJ, Gasparini F, Markou A. Group II metabotropic and alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA)/kainate glutamate receptors regulate the deficit in brain reward function associated with nicotine withdrawal in rats. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2003;306:1068–1076. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeSage MG, Burroughs D, Dufek M, Keyler DE, Pentel PR. Reinstatement of nicotine self-administration in rats by presentation of nicotine-paired stimuli, but not nicotine priming. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechti ME, Lhuillier L, Kaupmann K, Markou A. Metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptors in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens shell are involved in behaviors relating to nicotine dependence. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9077–9085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1766-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Palmatier MI, Donny EC, Sved AF. Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats: effect of bupropion, persistence over repeated tests, and its dependence on training dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0967-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Yee SK, Nobuta H, Poland RE, Pechnick RN. Reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior by drug-associated stimuli after extinction in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0134-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Grimm JW, Dempsey J, Shaham Y. Cocaine seeking over extended withdrawal periods in rats: different time courses of responding induced by cocaine cues versus cocaine priming over the first 6 months. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004a;176:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1860-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Grimm JW, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal: a review of preclinical data. Neuropharmacology. 2004b;47(Suppl 1):214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Hiott FB, Liu J, Salley AN, Behm FM, Rose JE. Selectively reduced responses to smoking cues in amygdala following extinction-based smoking cessation: results of a preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Addict Biol. 2007;12:503–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, McLellan AT. Myths about the treatment of addiction. Lancet. 1996;347:237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Mercincavage M, Fonte CA, Lerman C. Varenicline's effects on acute smoking behavior and reward and their association with subsequent abstinence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1816-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J, Dawkins L, West R, Pickering A. Relapse to smoking during unaided cessation: clinical, cognitive and motivational predictors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:537–549. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1975-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Are associative changes in acquisition and extinction negatively accelerated? J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2001;27:307–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE. Nicotine and nonnicotine factors in cigarette addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:274–285. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Behm FM, Levin ED. Role of nicotine dose and sensory cues in the regulation of smoke intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44:891–900. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90021-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev U, Morales M, Hope B, Yap J, Shaham Y. Time-dependent changes in extinction behavior and stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking following withdrawal from heroin in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:98–107. doi: 10.1007/s002130100748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard JD, Bossert JM, Liu SY, Shaham Y. The anxiogenic drug yohimbine reinstates methamphetamine seeking in a rat model of drug relapse. Biological psychiatry. 2004;55:1082–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. American journal of preventive medicine. 2008;34:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjei KL, Markou A. Effects of repeated withdrawal episodes, nicotine dose, and duration of nicotine exposure on the severity and duration of nicotine withdrawal in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:280–292. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland MT, Carroll AJ, Salmeron BJ, Ross TJ, Hong LE, Stein EA. Down-regulation of amygdala and insula functional circuits by varenicline and nicotine in abstinent cigarette smokers. Biological psychiatry. 2013;74:538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaur S, Strasser AA, Souprountchouk V, Evans GC, Ashare RL. Time dependency of craving and response inhibition during nicotine abstinence. Addiction research & theory. 2015;23:205–212. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2014.953940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]