Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play an important role in innate immune responses against pathogenic microorganisms or tissue damage. Nucleic acid (NA)-sensing TLRs localize in intracellular vesicular compartments and recognize foreign- and host-derived nucleotides. Inappropriate activation of NA-sensing TLRs can cause pathogenic inflammation and autoimmunity. Multiple regulatory mechanisms exist to limit recognition of self-NAs. This review summarizes recent progress that has been made in understanding how NA-sensing TLRs are regulated via trafficking, proteolytic cleavage, as well as ligand processing and recognition.

Introduction

The innate immune system recognizes microbes using a limited set of germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). These receptors have been evolutionarily selected to recognize highly conserved features of microbes, known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [1]. TLRs have emerged over the past 20 years as crucial PRRs. These receptors share common structural features: an extracellular leucine-rich-repeat (LRR) domain that binds to ligand, a transmembrane domain, and a cytosolic Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) homology domain. Activation of TLRs induces production of inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons as well as induction of adaptive immunity [2].

Nearly half of TLRs recognize nucleic acid ligands. TLR3, TLR7/8 and TLR9 reside intracellularly and respond to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and DNA, respectively. TLR13 has been recently reported to recognize bacterial ribosomal RNA [3]. Although sensing of microbial nucleic acid is crucial for effective immunity, it raises the potential risk of self-recognition, which can lead to autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [4]. Multiple regulatory mechanisms have been developed by the host to prevent the activation of TLRs by self-derived nucleic acid. The first of these mechanisms is receptor localization. Localization within endosomal compartments limits the recognition of self-derived ligands that are released by dying cells and primarily found in the extracellular space [5]. This compartmentalization is reinforced by the requirement for proteolytic processing of NA-sensing TLRs. In order to become a functional receptor, the extracellular LRR domain of TLR3, 7, 8, and 9 needs to be cleaved by endosome-resident proteases [6,7]. In this way, proteolysis of TLRs is inherently linked to their intracellular localization. In addition to strategies based on receptor compartmentalization, expression levels of TLRs have to be tightly controlled to avoid excessive stimulation. TLR7 is the prime example of this principle, as simply increasing TLR7 gene copy number can lead to autoimmune disease [8,9]. A suboptimal codon-bias of the Tlr7 gene has recently been shown to safeguard from excessive receptor expression by negatively impacting Tlr7 transcription and translation [10]. Besides regulation at the receptor level, there is emerging evidence that delivery and processing of nucleic acid ligands can influence TLR activation [11]. In this review we will highlight recent work on regulatory mechanisms targeting the trafficking of NA-sensing TLRs, receptor proteolysis, as well as recognition and processing of ligands.

Regulation of receptor trafficking

NA-sensing TLRs are known to traffic via the conventional secretory pathway (from ER to Golgi). Multiple levels of regulation underlie the trafficking of TLRs, including the initial steps of ER export. Several folding chaperones, including gp96 and PRAT4A, are involved in TLR protein folding within the ER [12–14]. Sorting of intracellular TLRs is controlled by the trafficking chaperone Unc93b1, which physically interacts with TLRs and regulates ER export and partitioning to endolysosomes [15,16]. A non-functional allele of Unc93b1 that abolishes this interaction (H412R) is retained in the ER and results in loss of endosomal TLR signaling in humans and mice [17,18]. Recently, another ER membrane protein, named LRRC59, has been shown to be involved in this process, likely by assisting the loading of NA-sensing TLRs into COPII vesicles [19]. In spite of these findings, how Unc93b1 or LRRC59 coordinate with other factors for exporting TLRs from the ER remains poorly understood.

All nucleic acid sensing TLRs traffic to endosomes via an Unc93b1-dependent manner and studies of Unc93b1 reveal potential competition between individual TLRs during trafficking. For instance, the Unc93b1 D34A mutation results in preferred interaction and trafficking of TLR7 over TLR9 and leads to TLR7-dependent lethal inflammation in mice [20,21]. The competition between TLR7 and -9 might explain the opposing roles of these two receptors in lupus mouse models, where disease is ameliorated by the loss of TLR7 but paradoxically exacerbated by the loss of TLR9 [22,23]. These results indicate a role of Unc93b1 in preventing aberrant NA-sensing TLR responses via controlling their ER export rates distinctly. Whether the selective trafficking of TLRs by Unc93b1 relies on additional proteins remains an unsolved question.

NA-sensing TLRs are believed to function in multiple intracellular organelles. Several mechanisms that regulate sorting of TLRs to specialized signaling compartments have been described. For example, TLR9 is sorted to lysosomal compartments through multi-vesicular bodies by ESCRT system. The compartmentalization of TLR9 in this process requires its ubiquitination [24]. Another example of specialized trafficking of TLRs between intracellular organelle subtypes depends on Adaptor Protein 3 (AP-3). In macrophages, AP-3 is responsible for the trafficking of TLR9 from endosomes to a specialized lysosome-related organelle, where activation of TLR9 leads to production of type I IFN rather than proinflammatory cytokines [25]. This concept of specialized signaling endosomes was first appreciated by comparing the TLR9 response to oligonucleotides with differential access to these specialized endosomes [26]. Since the initial introduction of this concept not much progress has been made toward understanding the cell biology underlying these observations. One reason might be the challenge in identifying subpopulations of endosomes and lysosomes involved in TLR signaling, due to the highly dynamic nature of the endocytic membrane system and lack of sufficient endosomal markers. Moreover, cell type-specific variations of the endosomal landscape and differences in TLR trafficking further complicate the picture. At this point we do not have a generalized view of the logic underlying specialized TLR signaling compartments.

As critical innate immune sensors, NA-sensing TLRs are continually trafficked to endosomal compartments even in the absence of infection. However, TLR trafficking can be regulated at different levels in response to nucleic acid ligands. There is evidence that the ER export rate of TLR9 is modulated as a result of CpG oligonucleotide stimulation [27,28]. Phosphorylation of TLR9 by Src kinases is necessary for its appropriate intracellular localization and stability [29,30]. Another example from TLR3 studies indicates that TLR trafficking from early endosomes into late endosomes can also be modulated in response to synthetic ligands or pathogens [31]. Notably, all this regulation seem to function in a TLR-specific manner, which may help the host control response levels against specific stimuli without disturbing overall immune homeostasis. Ligand-induced regulation provides the host a way to set up feedback mechanisms in response to nucleic acid ligands. The coordination between ligand-dependent and –independent regulation of NA-sensing TLR trafficking requires further investigation.

Proteolytic processing of TLRs

By restricting the functional form of TLRs to endosomal compartments, proteolytic processing has been appreciated as a crucial regulatory checkpoint to limit self-recognition. Additional levels of this regulation are cell type or receptor-specific differences among the cellular compartments in which the processing takes place, the enzymes involved in TLR cleavage and their pH requirements; all of which allow a fine-tuned regulation of receptor processing among different cell types or under different cellular activation states.

Lysosomal cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidases with acidic pH optima have been implicated in the cleavage of TLRs [6,32–34], with the exception of human TLR7 and -8. These two receptors can be cleaved by the furin-like proprotein convertase, which operates at neutral pH and might therefore generate functional hTLR7 and -8 before they reach acidic endosomes [7,35]. Cleavage of TLR9 seems to be a pre-requisite for TLR activation, as a pre-cleaved receptor (lacking the N-terminal half of the ectodomain) does not support TLR9 activation [36,37]. Puzzling at first, this observation can now be explained by the fact that the N-terminal cleavage product has to stay associated with the C-terminal half to form a functional receptor [36]. This principle also applies to the other NA-sensing TLRs [7,38,39]. Consistent with this finding, the crystal structures of TLR7, -8, and -9 provide structural evidence for the requirement of TLR processing and the continuing association of the two cleavage products [40–42]. As a unifying rule, nucleic acid ligands for TLR3, -7, -8 and -9 seem to directly contact both the N-terminal and C-terminal half of the receptor, forming a “molecular bridge” holding the individual pieces together [40–43]. In the case of TLR7, an additional disulfide bond between Cys98 and Cys475 links the N-terminal fragment to the rest of the receptor [38], whereas no covalent interactions have been detected for the other TLRs.

The fact that the N-terminal fragment remains associated with endosomal TLRs after proteolytic cleavage raises the question of what role proteolytic processing plays. Biochemical as well as structural studies of TLR8 and -9 reveal that proteolytic cleavage is dispensable for ligand binding, as uncleaved receptor binds equally well to nucleic acid ligands [40,44,45]. Instead, processing is required for ligand-induced oligomerization of the two TLR protomers, as without processing the uncleaved Z-loop region has been suggested to sterically interfere with receptor dimerization [45].

In summary, the proteolytic cleavage of intracellular TLRs neither releases the N-terminal half nor alters the overall receptor conformation. However, it profoundly impacts ligand-mediated dimerization and activation of TLRs.

TLR structure and ligand recognition

TLRs have been notoriously difficult to crystallize. Only recently, the structure of TLR7 bound to its natural ligands has been solved, so that finally structures are available for TLR3, -7, -8, and -9 [40,42,43,46].

There is still inconsistency of whether NA-sensing TLRs exist as a monomer or dimer before ligand engagement. The unbound ectodomain (ECD) of TLR3 has been shown to crystallize as a monomer [47], as does the ectodomain of TLR9. Upon addition of ligand both TLR3 and -9 form dimers. However, another study looking at full-length TLR9 in cells suggested that TLR9 exists as a pre-formed homodimer and ligand binding simply induces a conformational change necessary for receptor activation [48]. The discrepancy between these findings may be explained by the incomplete structural information, which only considers the TLR ECDs and therefore, might not reflect the physiological condition of full-length receptor within a cell.

The structure of TLR9 reveals that binding of agonist DNA contacts the N-terminal fragment of one TLR9 and the C-terminal half of another TLR9 molecule, inducing ligand-dependent dimerization [40]. In contrast, inhibitory DNA only interacts with the N-terminal fragment and does not trigger dimerization of TLR9. It has been well appreciated that the immunostimulatory activity of oligonucleotides is sequence-dependent and requires a core CpG motif [49]. The differential interaction of agonist and inhibitory DNA with the TLR9 ECD provides the first mechanistic explanation for this sequence-dependent regulation. Furthermore, methylated CpG yield weaker binding to and dimerization of TLR9 compared to ummethylated CpG, supporting the original paradigm that TLR9 evolved to sense bacterial-derived unmethylated DNA. As all of these studies have been using synthetic short CpG-oligonucleotides, the question still remains how TLR9 deals with the recognition of complex genomic DNA. Assuming that genomic DNA is degraded within the endolysosome into random fragments with varying immunogenicity, the ability to overcome the activation threshold of TLR9 may be a function of competition between agonist and inhibitory DNA sequences and may depend on the species-specific genomic GC content or the epigenetic status of the DNA.

TLR7 and 8 seem to recognize their ligands in a manner distinct from ligand binding by TLR9. The TLR7 structure reveals two ligand-binding sites that function synergistically in the activation of the receptor [42]. The first site is occupied by a single guanosine (or its derivatives), which is sufficient to induce receptor dimerization. The second site binds a short ssRNA oligoribonucleotide preferable containing a non-terminal uridine. Binding of the second ligand synergistically enhances the affinity for guanosine to the first site. An analogous mechanism of ligand recognition is employed by TLR8, although uridine is preferred over guanosine in the first binding site [46,50].

None of the two ligands alone is sufficient to induce TLR7 activation. Thus, TLR7 is a dual receptor for guanosine and uridine-containing ssRNA. Similar to the sequence-dependency of TLR9 ligands, the ssRNA sequence determines the binding affinity and activation of TLR7. Interestingly, the synthetic guanosine analog R848 (Resiquimod) binds in a similar manner to TLR7 as guanosine. However, slightly different amino acid contacts compared to guanosine and a higher overall affinity makes this small-chemical ligand sufficient to activate TLR7 even in the absence of ssRNA.

Cargo handling and processing of ligands

TLR ligands themselves are subject to regulation. The stimulatory capacity of ligands depends on the type of ligand, local concentration, stability, the mode of uptake, as well as the type of endosomes these ligands can access. Generally, nucleic acids alone are not sufficient to break TLR tolerance, but association with molecules that protect them from degradation can transform them into potent TLR activators. A number of accessory proteins have been discovered that bind to DNA or RNA and facilitate their uptake and activation of TLRs. Also nucleic acids presented in the form of immune complexes are very potent activators of TLRs. During conditions of autoinflammation or autoimmunity, accessory proteins and immune complexes are found in higher serum concentrations and contribute to enhanced self-recognition and inflammation. We refer readers interested in this particular subject to several excellent reviews [44,51].

A major mechanism to prevent self-recognition through TLR9 is the continuous degradation of DNA by DNases. Recently, DNases have also been shown to be required for TLR9 activation by processing DNA into shorter stimulatory cleavage products [52]. These findings place DNases as critical regulators of TLR9 activation by controlling the availability of stimulatory ligands in vivo. Three different DNase families exist: DNase I, II, and III, which are localized and operate in the circulation, lysosomes, or the cytoplasm, respectively. Lack or loss-of-function of DNase I causes lupus-like disease in humans and mice [53,54]. The specific receptors responsible for recognition of the undigested DNA remain to be identified. Likewise, deficiency of DNase I-like III, another member of the DNase I family, causes an aggressive form of familial SLE [55]. In contrast to DNase I, DNase I-like III has the ability to degrade DNA encapsulated in lipids or in the form of dense chromatin particles [56,57]. Accordingly, DNase I-like III-deficient mice experience an elevated concentration of circulating DNA-containing microparticles and develop autoantibodies to DNA and chromatin, followed by an SLE-like disease [58]. The clinical manifestations could be completely rescued by MyD88 deficiency, indicating a role for TLRs in sensing the DNA-containing microparticles. DNase II deficiency causes accumulation of DNA in lysosomes and lethal anemia in mice [59]. Surprisingly, TLR9 has been ruled out as the sensor for lysosomal DNA in this model. Instead, accumulated DNA seems to leak out into the cytosol and induces Sting and Aim2-mediated inflammation, two cytosolic DNA sensing pathways [60,61]. The inability of TLR9 to respond to accumulated DNA in lysosomes could be later explained by the requirement of DNase II to process and provide suitable DNA pieces for TLR9 activation [52]. This idea is also in line with structural data showing that TLR9 does not bind to dsDNA, emphasizing the need for processing to generate ssDNA [40].

Likewise, TLR7 and –8 are stimulated by breakdown products of RNA, such as guanosine or uridine, and TLR3 binds dsRNA fragments of 40–50 nucleotides of length. Analogous to the function of DNase II, this would predict the existence of processing mechanisms for endosomal RNA sensors. So far, the specific enzymes (RNases and phosphatases) involved in processing of lysosomal RNA have not been identified.

In addition to guanosine, TLR7 can also bind and respond to deoxyguanosine, a breakdown product of DNA [62]. This raises the possibility that, in addition to RNA, TLR7 can also respond to DNA degradation products in the presence of oligoribonucleotides. This theory might shed light on the puzzling observation that DNase II-deficient mice show elevated anti-RNA antibodies, suggesting that accumulated DNA in lysosomes can activate TLR7 [63].

Altogether, these examples raise interesting possibilities about the initial source of nucleic acid breakdown products for TLR7. Nucleosides could be derived from the cytosol of dying cells as intermediates of nucleic-acid metabolism, whereas nucleotides could simply be breakdown products of digested DNA and RNA. Future studies will hopefully elucidate how nucleic acids are being degraded in the lysosome, identify the required enzymes, and decipher how nucleic-acid metabolism may regulate innate immune sensing.

Concluding remarks

Considering the multitude of TLRs that have evolved to sense nucleic acids, the recognition of microbial DNA or RNA clearly represents a key strategy by which the innate immune system detects infection. However, the detection of nucleic acids comes with the risk of self-recognition and autoimmunity. Therefore, tight regulation of NA-sensing TLRs at multiple levels is required to limit responses against self. For some of these regulatory principles the field has made considerable progress within the last years, including the critical role of Unc93b1 in TLR trafficking and signaling, structural evidence for receptor proteolysis and ligand recognition, as well as the processing of nucleic acids. Yet, there are still many open questions about the endogenous source and the nature of these nucleic acid ligands, the diverse pathways regulating TLR trafficking to endosomes, and the components that define endosomes with distinct TLR signaling properties. Better knowledge of the regulatory mechanisms of intracellular TLR signaling will shed light on the pathogenesis of autoimmunity and inflammatory diseases and will provide important clues for the development of new diagnostics and therapeutic approaches to treat these diseases.

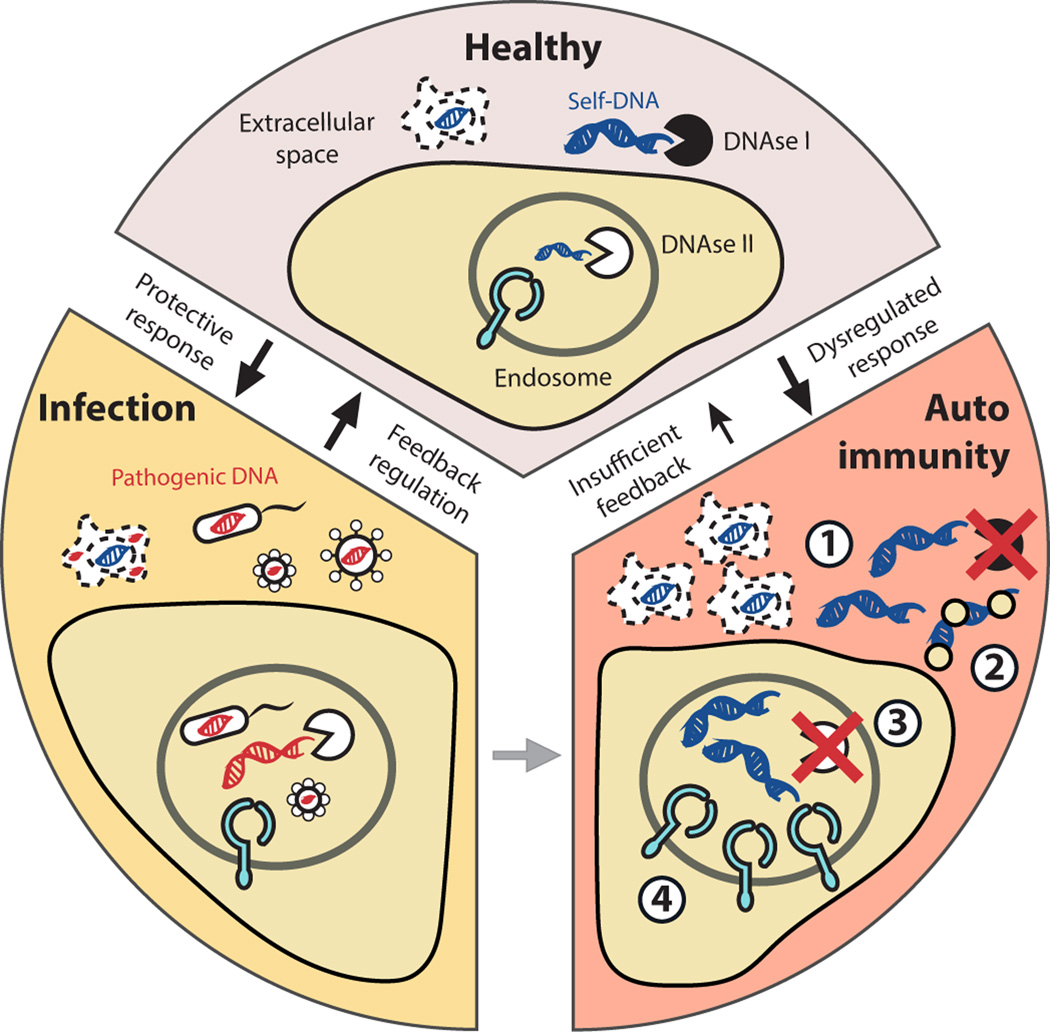

Figure 1.

Self versus non-self discrimination by NA-sensing TLRs and how dysregulated responses can lead to autoimmunity. The intracellular localization of NA-TLRs limits the recognition of self-nucleic acids that are derived from dying cells and primarily found in the extracellular space. DNases continuously degrade free DNA to avoid autoimmune responses. Upon infection, microbial DNA is released into the endolysosome, where it engages with TLRs and triggers a protective immune response. 1) Accumulation of self-nucleic acids due to defective clearance, 2) elevated levels of stabilizing proteins that protect DNA/RNA from degradation, 3) deficient degradation of nucleic acids, 4) as well as increased TLR7 levels can lead to autoimmunity. In some instances, infections can also trigger or exacerbate autoimmunity.

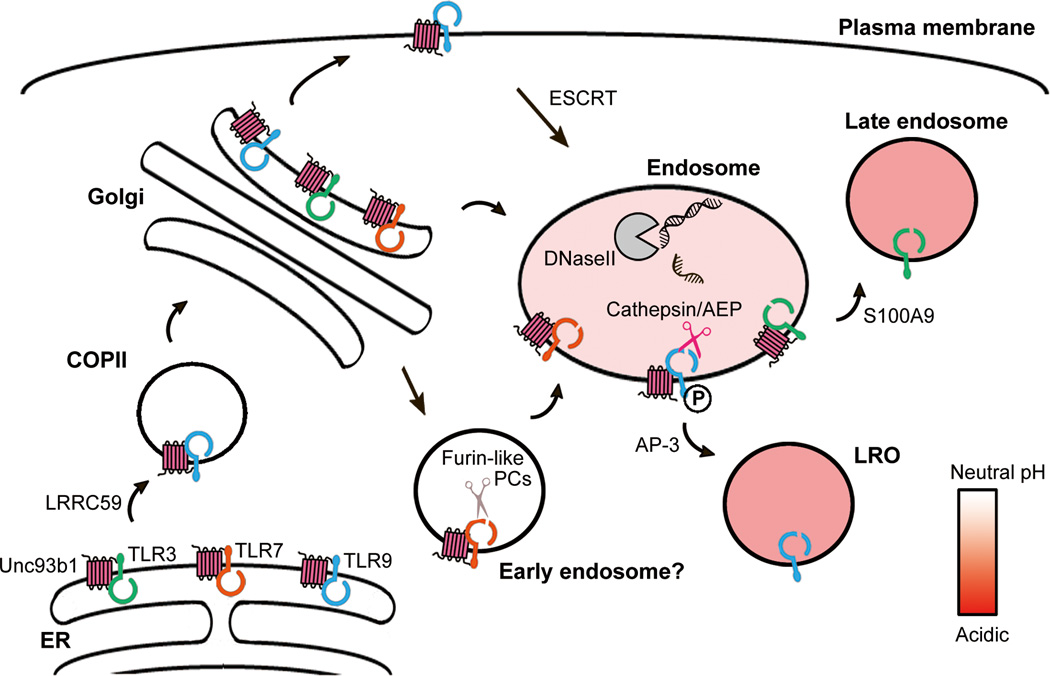

Figure 2.

Trafficking pathways regulating the localization of NA-sensing TLRs. Unc93b1 interacts with all NA-sensing TLRs in the ER and facilitates export into COPII vesicles. Unc93b1 remains associated with TLRs after exit from the ER. Individual TLRs may access distinct intracellular compartments and are subject to specific sorting mechanisms. AEP: asparagine endopeptidase; ESCRT: endosomal sorting complexes required for transport; LRO: lysosome-related organelle; PC: proprotein convertase.

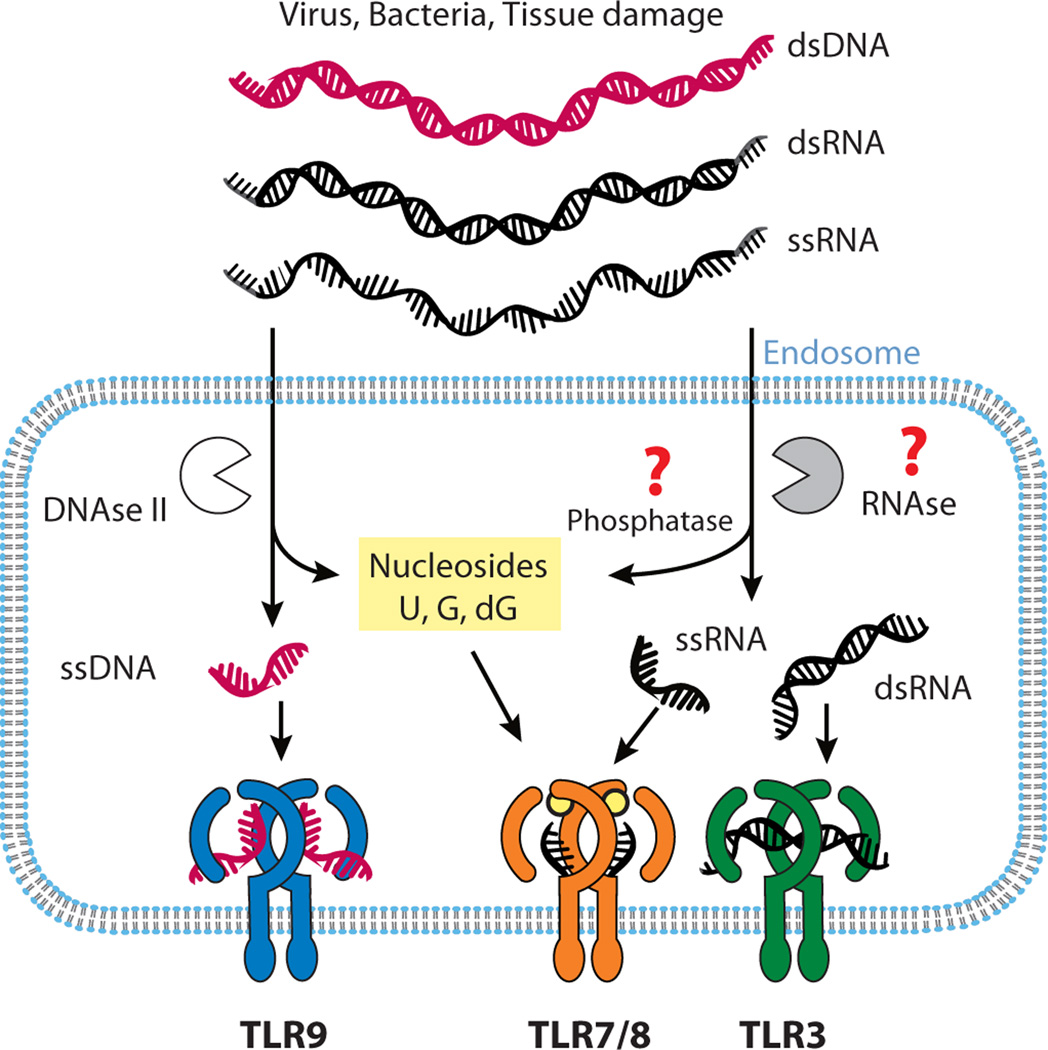

Figure 3.

Nucleic acid processing and ligand binding by TLRs. Foreign as well as self-derived nucleic acids are delivered to the endolysosome where they are further processed by either DNase II or an unknown RNase to yield shorter fragments that can activate TLRs. TLR9 binds to short single-stranded oligonucleotides with a stimulatory core CpG motif. TLR7/8 recognize nucleoside breakdown products as well as oligoribonucleotides. TLR3 is activated by dsRNA.

Highlights.

Nucleic acid-sensing TLRs are regulated at multiple levels to maintain immunological tolerance to host-derived ligands.

The recently solved crystal structures of TLR7, -8, and -9 provide evidence for the need of proteolytic processing and the mode of ligand binding.

TLR7 and -8 are dual receptors for single nucleosides and short ssRNA oligoribonucleotides

The need for ligand processing to generate stimulatory nucleic acid fragments emerges as a new principle for TLR activation

Acknowledgments

Research in the Barton Lab is supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI072429, AI105184, and AI063302), the Lupus Research Institute, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Janeway CA., Jr Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54(Pt 1):1–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldenburg M, Kruger A, Ferstl R, Kaufmann A, Nees G, Sigmund A, Bathke B, Lauterbach H, Suter M, Dreher S, et al. TLR13 recognizes bacterial 23S rRNA devoid of erythromycin resistance-forming modification. Science. 2012;337:1111–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1220363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlee M, Hartmann G. Discriminating self from non-self in nucleic acid sensing. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:566–580. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton GM, Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Intracellular localization of Toll-like receptor 9 prevents recognition of self DNA but facilitates access to viral DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewald SE, Engel A, Lee J, Wang M, Bogyo M, Barton GM. Nucleic acid recognition by Toll-like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase. J Exp Med. 2011;208:643–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii N, Funami K, Tatematsu M, Seya T, Matsumoto M. Endosomal localization of TLR8 confers distinctive proteolytic processing on human myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:5118–5128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisitkun P, Deane JA, Difilippantonio MJ, Tarasenko T, Satterthwaite AB, Bolland S. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1124978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deane JA, Pisitkun P, Barrett RS, Feigenbaum L, Town T, Ward JM, Flavell RA, Bolland S. Control of toll-like receptor 7 expression is essential to restrict autoimmunity and dendritic cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;27:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newman ZR, Young JM, Ingolia NT, Barton GM. Differences in codon bias and GC content contribute to the balanced expression of TLR7 and TLR9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1362–E1371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518976113. Suboptimal codon bias of the Tlr7 gene locus, which correlates with low GC content, limits TLR7 expression relative to TLR9. Poor codon usage results in decreased gene transcription and translation and represents a new mechanism to establish low levels of TLR7, whose overexpression is known to cause autoimmunity.

- 11.Miyake K, Shibata T, Ohto U, Shimizu T. Emerging roles of the processing of nucleic acids and Toll-like receptors in innate immune responses to nucleic acids. J Leukoc Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1189/jlb.4MR0316-108R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Liu B, Dai J, Srivastava PK, Zammit DJ, Lefrancois L, Li Z. Heat shock protein gp96 is a master chaperone for toll-like receptors and is important in the innate function of macrophages. Immunity. 2007;26:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K, Shibata T, Akashi-Takamura S, Kiyokawa T, Wakabayashi Y, Tanimura N, Kobayashi T, Matsumoto F, Fukui R, Kouro T, et al. A protein associated with Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 (PRAT4A) is required for TLR-dependent immune responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2963–2976. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu B, Yang Y, Qiu Z, Staron M, Hong F, Li Y, Wu S, Li Y, Hao B, Bona R, et al. Folding of Toll-like receptors by the HSP90 paralogue gp96 requires a substrate-specific cochaperone. Nat Commun. 2010;1:79. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YM, Brinkmann MM, Paquet ME, Ploegh HL. UNC93B1 delivers nucleotide-sensing toll-like receptors to endolysosomes. Nature. 2008;452:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature06726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee BL, Moon JE, Shu JH, Yuan L, Newman ZR, Schekman R, Barton GM. UNC93B1 mediates differential trafficking of endosomal TLRs. Elife. 2013;2:e00291. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinkmann MM, Spooner E, Hoebe K, Beutler B, Ploegh HL, Kim YM. The interaction between the ER membrane protein UNC93B and TLR3, 7, and 9 is crucial for TLR signaling. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:265–275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casrouge A, Zhang SY, Eidenschenk C, Jouanguy E, Puel A, Yang K, Alcais A, Picard C, Mahfoufi N, Nicolas N, et al. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in human UNC-93B deficiency. Science. 2006;314:308–312. doi: 10.1126/science.1128346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatematsu M, Funami K, Ishii N, Seya T, Obuse C, Matsumoto M. LRRC59 Regulates Trafficking of Nucleic Acid-Sensing TLRs from the Endoplasmic Reticulum via Association with UNC93B1. J Immunol. 2015;195:4933–4942. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukui R, Saitoh S, Matsumoto F, Kozuka-Hata H, Oyama M, Tabeta K, Beutler B, Miyake K. Unc93B1 biases Toll-like receptor responses to nucleic acid in dendritic cells toward DNA- but against RNA-sensing. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1339–1350. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukui R, Saitoh S, Kanno A, Onji M, Shibata T, Ito A, Onji M, Matsumoto M, Akira S, Yoshida N, et al. Unc93B1 restricts systemic lethal inflammation by orchestrating Toll-like receptor 7 and 9 trafficking. Immunity. 2011;35:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, Kashgarian M, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickerson KM, Christensen SR, Shupe J, Kashgarian M, Kim D, Elkon K, Shlomchik MJ. TLR9 regulates TLR7- and MyD88-dependent autoantibody production and disease in a murine model of lupus. J Immunol. 2010;184:1840–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiang CY, Engel A, Opaluch AM, Ramos I, Maestre AM, Secundino I, De Jesus PD, Nguyen QT, Welch G, Bonamy GM, et al. Cofactors required for TLR7- and TLR9-dependent innate immune responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasai M, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A. Bifurcation of Toll-like receptor 9 signaling by adaptor protein 3. Science. 2010;329:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1187029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honda K, Ohba Y, Yanai H, Negishi H, Mizutani T, Takaoka A, Taya C, Taniguchi T. Spatiotemporal regulation of MyD88-IRF-7 signalling for robust type-I interferon induction. Nature. 2005;434:1035–1040. doi: 10.1038/nature03547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Latz E, Schoenemeyer A, Visintin A, Fitzgerald KA, Monks BG, Knetter CF, Lien E, Nilsen NJ, Espevik T, Golenbock DT. TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:190–198. doi: 10.1038/ni1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu JY, Kuo CC. ADP-Ribosylation Factor 3 Mediates Cytidine-Phosphate-Guanosine Oligodeoxynucleotide-Induced Responses by Regulating Toll-Like Receptor 9 Trafficking. J Innate Immun. 2015;7:623–636. doi: 10.1159/000430785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chockalingam A, Rose WA, 2nd, Hasan M, Ju CH, Leifer CA. Cutting edge: a TLR9 cytoplasmic tyrosine motif is selectively required for proinflammatory cytokine production. J Immunol. 2012;188:527–530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasan M, Gruber E, Cameron J, Leifer CA. TLR9 stability and signaling are regulated by phosphorylation and cell stress. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100:525–533. doi: 10.1189/jlb.2A0815-337R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai SY, Segovia JA, Chang TH, Shil NK, Pokharel SM, Kannan TR, Baseman JB, Defrene J, Page N, Cesaro A, et al. Regulation of TLR3 Activation by S100A9. J Immunol. 2015;195:4426–4437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Cattaneo A, Gobert FX, Muller M, Toscano F, Flores M, Lescure A, Del Nery E, Benaroch P. Cleavage of Toll-like receptor 3 by cathepsins B and H is essential for signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9053–9058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115091109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi R, Singh D, Kao CC. Proteolytic processing regulates Toll-like receptor 3 stability and endosomal localization. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:32617–32629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.387803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sepulveda FE, Maschalidi S, Colisson R, Heslop L, Ghirelli C, Sakka E, Lennon-Dumenil AM, Amigorena S, Cabanie L, Manoury B. Critical role for asparagine endopeptidase in endocytic Toll-like receptor signaling in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;31:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hipp MM, Shepherd D, Gileadi U, Aichinger MC, Kessler BM, Edelmann MJ, Essalmani R, Seidah NG, Reis e Sousa C, Cerundolo V. Processing of human toll-like receptor 7 by furin-like proprotein convertases is required for its accumulation and activity in endosomes. Immunity. 2013;39:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onji M, Kanno A, Saitoh S, Fukui R, Motoi Y, Shibata T, Matsumoto F, Lamichhane A, Sato S, Kiyono H, et al. An essential role for the N-terminal fragment of Toll-like receptor 9 in DNA sensing. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1949. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinha SS, Cameron J, Brooks JC, Leifer CA. Complex Negative Regulation of TLR9 by Multiple Proteolytic Cleavage Events. J Immunol. 2016;197:1343–1352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanno A, Yamamoto C, Onji M, Fukui R, Saitoh S, Motoi Y, Shibata T, Matsumoto F, Muta T, Miyake K. Essential role for Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-unique cysteines in an intramolecular disulfide bond, proteolytic cleavage and RNA sensing. Int Immunol. 2013;25:413–422. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxt007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toscano F, Estornes Y, Virard F, Garcia-Cattaneo A, Pierrot A, Vanbervliet B, Bonnin M, Ciancanelli MJ, Zhang SY, Funami K, et al. Cleaved/associated TLR3 represents the primary form of the signaling receptor. J Immunol. 2013;190:764–773. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ohto U, Shibata T, Tanji H, Ishida H, Krayukhina E, Uchiyama S, Miyake K, Shimizu T. Structural basis of CpG and inhibitory DNA recognition by Toll-like receptor 9. Nature. 2015;520:702–705. doi: 10.1038/nature14138. This structural study establishes the molecular basis by which immunostimulatory CpG-oligonucleotides elicit TLR9 responses. Three distinct crystal structures of TLR9: unbound, bound to agonist DNA, bound to inhibitory DNA reveal the difference between these ligands in binding TLR9 and inducing receptor dimerization.

- 41.Tanji H, Ohto U, Shibata T, Miyake K, Shimizu T. Structural reorganization of the Toll-like receptor 8 dimer induced by agonistic ligands. Science. 2013;339:1426–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.1229159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang Z, Ohto U, Shibata T, Krayukhina E, Taoka M, Yamauchi Y, Tanji H, Isobe T, Uchiyama S, Miyake K, et al. Structural basis for activation of Toll-like receptor 7, a dual receptor for guanosine and single-stranded RNA. Immunity. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.011. In press. This study is the first one to introduce the natural ligands for TLR7. TLR7 harbors two distinct ligand binding sites: one for a single guanosine and the second one for a short ssRNA oligoribonucleotide. Both of these sites have to be bound to trigger receptor activation. In contrast, an artificial small-molecule agonist is able to activate TLR7 by binding the first site only. This new concept of TLR7 recognizing break-down products of nucleic acids suggests the existence of specific RNases involved in the processing of lysosomal RNA.

- 43.Liu L, Botos I, Wang Y, Leonard JN, Shiloach J, Segal DM, Davies DR. Structural basis of toll-like receptor 3 signaling with double-stranded RNA. Science. 2008;320:379–381. doi: 10.1126/science.1155406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ewald SE, Barton GM. Nucleic acid sensing Toll-like receptors in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tanji H, Ohto U, Motoi Y, Shibata T, Miyake K, Shimizu T. Autoinhibition and relief mechanism by the proteolytic processing of Toll-like receptor 8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:3012–3017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516000113. Proteolytic cleavage of the TLR8 ectodomain is a prerequisite for receptor dimerization and activation. Using a TLR8 mutant with a non-cleavable ectodomain, the authors show that the uncleaved Z-loop sterically interferes with the dimerization process.

- 46.Tanji H, Ohto U, Shibata T, Taoka M, Yamauchi Y, Isobe T, Miyake K, Shimizu T. Toll-like receptor 8 senses degradation products of single-stranded RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:109–115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choe J, Kelker MS, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of human toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) ectodomain. Science. 2005;309:581–585. doi: 10.1126/science.1115253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Latz E, Verma A, Visintin A, Gong M, Sirois CM, Klein DC, Monks BG, McKnight CJ, Lamphier MS, Duprex WP, et al. Ligand-induced conformational changes allosterically activate Toll-like receptor 9. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:772–779. doi: 10.1038/ni1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vollmer J, Weeratna R, Payette P, Jurk M, Schetter C, Laucht M, Wader T, Tluk S, Liu M, Davis HL, et al. Characterization of three CpG oligodeoxynucleotide classes with distinct immunostimulatory activities. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:251–262. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geyer M, Pelka K, Latz E. Synergistic activation of Toll-like receptor 8 by two RNA degradation products. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:99–101. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee CC, Avalos AM, Ploegh HL. Accessory molecules for Toll-like receptors and their function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:168–179. doi: 10.1038/nri3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chan MP, Onji M, Fukui R, Kawane K, Shibata T, Saitoh S, Ohto U, Shimizu T, Barber GN, Miyake K. DNase II-dependent DNA digestion is required for DNA sensing by TLR9. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5853. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6853. Using primary cells from Dnase2a−/− Ifnar1−/− mice, this work establishes the requirement of lysosomal DNase II for TLR9 activation. CpG-A, which contains a DNase II-sensitive sequence motif, as well as genomic bacterial DNA need to be processed by DNase II to generate shorter DNA fragments able to stimulate TLR9.

- 53.Napirei M, Karsunky H, Zevnik B, Stephan H, Mannherz HG, Moroy T. Features of systemic lupus erythematosus in DNase1-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:177–181. doi: 10.1038/76032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yasutomo K, Horiuchi T, Kagami S, Tsukamoto H, Hashimura C, Urushihara M, Kuroda Y. Mutation of DNASE1 in people with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2001;28:313–314. doi: 10.1038/91070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Mayouf SM, Sunker A, Abdwani R, Abrawi SA, Almurshedi F, Alhashmi N, Al Sonbul A, Sewairi W, Qari A, Abdallah E, et al. Loss-of-function variant in DNASE1L3 causes a familial form of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1186–1188. doi: 10.1038/ng.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizuta R, Araki S, Furukawa M, Furukawa Y, Ebara S, Shiokawa D, Hayashi K, Tanuma S, Kitamura D. DNase gamma is the effector endonuclease for internucleosomal DNA fragmentation in necrosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilber A, Lu M, Schneider MC. Deoxyribonuclease I-like III is an inducible macrophage barrier to liposomal transfection. Mol Ther. 2002;6:35–42. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sisirak V, Sally B, D'Agati V, Martinez-Ortiz W, Ozcakar ZB, David J, Rashidfarrokhi A, Yeste A, Panea C, Chida AS, et al. Digestion of Chromatin in Apoptotic Cell Microparticles Prevents Autoimmunity. Cell. 2016;166:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.034. DNASE1L3 is required for the degradation of extracellular microparticle-associated chromatin released by apoptotic cells. These microparticles, when not continuously cleared, can serve as potential self-antigens able to activate NA-sensing TLRs and trigger autoimmune responses.

- 59.Yoshida H, Okabe Y, Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Nagata S. Lethal anemia caused by interferon-beta produced in mouse embryos carrying undigested DNA. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahn J, Gutman D, Saijo S, Barber GN. STING manifests self DNA-dependent inflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19386–19391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baum R, Sharma S, Carpenter S, Li QZ, Busto P, Fitzgerald KA, Marshak-Rothstein A, Gravallese EM. Cutting edge: AIM2 and endosomal TLRs differentially regulate arthritis and autoantibody production in DNase II-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2015;194:873–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shibata T, Ohto U, Nomura S, Kibata K, Motoi Y, Zhang Y, Murakami Y, Fukui R, Ishimoto T, Sano S, et al. Guanosine and its modified derivatives are endogenous ligands for TLR7. Int Immunol. 2016;28:211–222. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pawaria S, Moody K, Busto P, Nundel K, Choi CH, Ghayur T, Marshak-Rothstein A. Cutting Edge: DNase II deficiency prevents activation of autoreactive B cells by double-stranded DNA endogenous ligands. J Immunol. 2015;194:1403–1407. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]