Abstract

Loss of pancreatic β-cell function is a hallmark of Type-II diabetes mellitus (DM). It is a chronic metabolic disorder that results from defects in both insulin secretion and insulin action. Recently, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study reported that Type-II DM is a progressive disorder. Although, DM can be treated initially by monotherapy with oral agent; eventually, it may require multiple drugs. Additionally, insulin therapy is needed in many patients to achieve glycemic control. Pharmacological approaches are unsatisfactory in improving the consequences of insulin resistance. Single therapeutic approach in the treatment of Type-II DM is unsuccessful and usually a combination therapy is adopted. Increased understanding of biochemical, cellular and pathological alterations in Type-II DM has provided new insight in the management of Type-II DM. Knowledge of underlying mechanisms of Type-II DM development is essential for the exploration of novel therapeutic targets. Present review provides an insight into therapeutic targets of Type-II DM and their role in the development of insulin resistance. An overview of important signaling pathways and mechanisms in Type-II DM is provided for the better understanding of disease pathology. This review includes case studies of drugs that are withdrawn from the market. The experience gathered from previous studies and knowledge of Type-II DM pathways can guide the anti-diabetic drug development toward the discovery of clinically viable drugs that are useful in Type-II DM.

Keywords: Type-II diabetes mellitus, therapeutic targets, discontinued drugs, insulin resistance

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the oldest disease known to mankind since about 3,000 years ago and is referred to in ancient Egyptian treatise.1 The prevalence of DM is continuously increasing and recent estimate shows that DM incidence will rise from 366.2 million people to 551.8 million by 2030.2,3 Generally, DM is classified as either Type-I or II, but Type-II DM is more prevalent form of diabetes. The long-term macrovascular and microvascular complications associated with Type-II DM typically ends up in morbidity and mortality. Type-II DM has a complex and multifactorial pathogenesis. It occurs either due to impaired insulin secretion by pancreas or development of insulin resistance at target tissues. Insulin maintains the energy homeostasis by increasing glucose uptake into peripheral tissues and decreasing release of stored lipids from adipose tissue.4 Dysfunction of β-cell decreases insulin secretion and alters the glucose homeostasis.5 Multiple biochemical pathways show the correlation between hyperglycemia and vascular complications. Type-II DM has a role in the development of cardiovascular and kidney diseases.6–8 Type-II DM is manifested by increased glucose production, defective insulin secretion and abnormal insulin action.9,10 The β-cell associated changes in the secretion of insulin initiates the cellular signaling cascade. Activation of advanced glycation end products, stimulation of Di-acyl glycerol kinase pathway and oxidative stress reduces the β-cell functioning.

The currently available anti-diabetic drugs used to treat Type-II DM are associated with potential adverse effects.11,12 Excessive insulin release by widely used anti-diabetic drugs like sulfonylureas causes hypoglycemia.13 Similarly, use of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR-γ) agonists is associated with weight gain, fluid retention, urinary bladder cancer, osteoporosis and cardiovascular complications.14 Rosiglitazone is PPAR agonist and widely used anti-diabetic drug. It acts primarily through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and its use is associated with weight gain and edema. Similarly, the antidiabetic effect of metformin exhibits the partial involvement of AMPK and shows the associated adversities. Despite promising preclinical results, the drug 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide nucleotide failed to demonstrate its efficacy in phase I clinical trial. Due to safety concerns, many promising molecules like dual-acting PPAR γ/α or pan modulators of PPAR are still awaiting the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Remedial approaches for the management of Type-II DM are aimed to delay the onset of complications following treatment with antidiabetic drugs. The search for more efficacious and safer antidiabetic agents is an active area of research. Newer drugs lacking the adverse effects of conventional antidiabetics and having ability to control hyperglycemia are critically needed. Incidence of Type-II DM can be minimized by identification of risk factors responsible for its occurrence. Understanding of mechanisms of actions of antidiabetic drugs, signaling pathways and therapeutic targets of Type-II DM can guide the development of clinically useful antidiabetic drugs. Present review provides an overview of underlying mechanisms of action of antidiabetic drugs. This paper also contains information on promising therapeutic targets of Type-II DM evolved from pharmacological and molecular studies.

Promising therapeutic targets

The treatment of Type-II DM and management of diabetic complications is a complex area of therapy. Limited treatment opportunities and shortage of therapeutic agents used to delay the diabetic complications are main hurdles in the treatment of Type-II DM. This therapeutic mystery can be resolved by the identification of novel therapeutic targets and development of new drugs. Postprandial euglycemia is maintained by gut-derived peptide hormones (incretins), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) (neuropeptide) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide/glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) through the stimulation of insulin secretion. Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) is a protease enzyme responsible for degradation of incretins. Inhibition of DPP-IV prevents the degradation of incretins, GLP-1 and GIP. It leads to elevated lowering of blood glucose level and control of hyperglycemia.15 Alogliptin is selective DPP-IV inhibitor approved by FDA for the treatment of Type-II DM in 2013. Development of insulin resistance in humans and rodents is a consequence of abnormal or overexpressed glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3). Two isozymes of GSK-3 that is, GSK-3α and GSK-3β are present in mammals. GSK-3β-2 is an alternative splice variant of GSK-3β.16 Although, GSK-3α and GSK-3β have close similarity in their catalytic domains, they differ at their N- and C-terminal regions.17 Selective GSK-3 inhibitors demonstrated their efficacy in animal models of Type-II DM through the increased insulin action in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle.18 Identification and understanding of therapeutic targets in Type-II DM is essential for the designing of therapeutic strategy. Various therapeutic targets in Type-II DM are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Classification of diabetic therapeutic targets according to molecular group and signaling molecules

| Signal transduction and molecular mechanism | Targets | Genes | Subcellular locations | Biological process | Associated drug(s) | Related disease(s) with this gene | Associated pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G protein-coupled receptor | Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor, gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor and bile acid sequestrate | GLP1R, GIPR GPBAR1 | Plasma membrane, extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus | GLP1R, GIPR GPBAR1 stimulates the adenylyl cyclase pathway results in increased insulin synthesis and release | GLP1R; exenatide liraglutide lixisenatide albiglutide dulaglutide GPBAR1; betulinic acid |

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, neoplasms, obesity, pancreatic neoplasms, metabolic syndrome X, Cushing syndrome, colitis, carcinoma | a) Signaling by GPCR b) Integration of energy metabolism c) Peptide ligand-binding receptors metabolism.71 |

| G protein-coupled receptor | Free fatty acid receptor or GPCR40, G protein-coupled receptor 119 and 39 | FFAR1 GPR119 GPR39 | Nucleus, plasma membrane, peroxisome | Protein metabolism | FFAR1; Palmitic acid, oleic acid, linoleic acid. GPR119; oleoylglycerol anandamide |

Diabetes mellitus obesity, glucagonoma, organ neoplasms, insulinoma, gastrinoma, fatty liver, metabolic disease | a) Signaling by GPCR b) Peptide ligand-binding receptors c) Incretin synthesis, secretion, and inactivation d) Integration of energy metabolism e) Gastrin-CREB signalling pathway via PKC and MAPK |

| Tyrosine kinase | Insulin receptors | INSR | Plasma membrane, cytosol, endosome, extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, nucleus | Phosphorylation of receptor substrates Glucose homeostasis | Insulins • Sulfonylureas • Meglitinides |

Diabetes mellitus, Donohue syndrome, Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, hyperinsulinism, diabetic neuropathies, glucose intolerance, Lewy body disease, proteinuria | a) GPCR pathway b) Insulin receptor signaling cascade c) Translation insulin regulation d) Nanog in mammalian ESC pluripotency |

| Dehydrogenase | 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 | HSD11B1 | Endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, cytosol, peroxisome | Increase intracellular cortisol by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and activation of glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathway | BVT-14225 BVT-2733 Pyridyl sulfonamide | Obesity hypertension, cortisone reductase deficiency, dermatitis, diabetes mellitus, Type-II | a) Metabolism b) Steroid hormone biosynthesis c) Prostaglandin synthesis72 |

| Oxidoreductase | Cytochrome P450 family 3, subfamily A, polypeptide 4 | CYP3A4 | Endoplasmic reticulum, extracellular, cytosol, Golgi apparatus, nucleus, plasma membrane, cytoskeleton | Metabolism | Ritonavir | Breast neoplasm, prostatic neoplasm, osteosarcoma, hepatitis, torsades de pointes, diabetes mellitus, kidney failure, anxiety | a) Biological oxidations b) Chemical carcinogenesis c) Cytochrome P450 – arranged by substrate type |

| Growth factor | Fibroblast growth factor 21 | FGF21 | Extracellular, cytosol, mitochondria, nucleus, peroxisome | Effects on normalizing glucose, lipid, and energy homeostasis | – | Obesity, fatty liver, diabetes mellitus, anorexia, ketosis. hypertension, stress, metabolic syndrome x, metabolic disease, lipodystrophy, liver neoplasm |

a) Apoptotic pathways in synovial fibroblasts b) GPCR pathway c) TGF-β pathway d) ERK signaling e) CREB pathway |

| Glucose co-transporter | Sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 | SLC5A2 | Plasma membrane, cytosol | 1) Insulin-mediated glucose uptake in muscle and adipose tissue. 2) GLUT1 mediates insulin-independent glucose transport |

Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, remogliflozin, empagliflozin, sergliflozin (inhibitors) | hypertension diabetes mellitus, Type-II aminoaciduria glucosuria | a) Transmembrane transport of small molecules b) Metabolism c) Hexose transport |

| Transcription factor | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | PPARG | Extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, peroxisome, nucleus, cytoskeleton | On activation, they induce peroxisome proliferation and lead to metabolism of dietary fats | Aleglitazar, muraglitazar, tesaglitazar | Inflammation hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, acute lung injury, acute kidney injury |

a) Nuclear receptor transcription pathway b) Metabolism c) Fatty acid, triacylglycerol, and ketone body metabolism d) Pathways in cancer.73 |

| Transcription factor | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, single transducer and activation of transcription 4, RANK1 | NFkB1 STAT4 TNFRSF11A | Nucleus, cytosol, plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, peroxisome | Regulation of cytokine production, proliferation | Curcumin, anethol, ursolic acid, capsaicin | Adenocarcinoma, colonic neoplasms, diabetes mellitus, obesity, liver cirrhosis, kidney failure, brain ischemia, liver diseases, hyperoxaluria, ovarian cysts, fatty liver, cerebral hemorrhage, breast neoplasms, autoimmune disease | a) TWEAK pathway b) 4–1BB pathway c) RANK signaling in Osteoclasts d) Cytosolic sensors of pathogen-associated DNA CNTF signaling e) GPCR pathway f) TGF-β pathway g) IL12-mediated signaling events |

| Transcription factor | Estrogen-related receptor-α | ESRRA | Nucleus, mitochondria, peroxisome | Metabolism | Cyclohexamethylaminem, 5,7-dihydroxy-4 methoxyisoflavone | Breast neoplasm, metabolic disease, diabetes mellitus, carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, neoplasm | a) Fatty acid, triacylglycerol, and ketone body metabolism b) Metabolism c) Gene expression d) Nuclear receptor transcription pathway |

| Serine/threonine protein kinase | AMPK mechanistic targets of rapamycin | PRKAB1 MTOR | Nucleus, extracellular, cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum | Anabolism, catabolism, metabolism | Metformin, phenformin, acadesine | Disease progression, stomach neoplasms, colonic neoplasms, diabetes mellitus, multiple myeloma, neurotoxicity, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal carcinoma, ovarian neoplasm | a) Insulin receptor signalling b) Signaling by GPCR c) ERK Signaling d) PI-3K cascade e) Signaling by FGFR f) mTOR Pathway |

| Ligase | Acetyl CoA, carboxylase α, Acetyl CoA, Carboxylase β | ACACA ACACB | Cytosol, mitochondrion chloroplast, nucleus, peroxisome | Skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation | – | Carcinoma, fatty liver, insulin resistance, breast neoplasm, malignant neoplasm, hyperlipidemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia | a) Defective BTD causes biotidinase deficiency b) Regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis by SREBP c) Fatty acid metabolism d) Metabolism |

| Interleukin receptor | Interleukin 12, interleukin 1, interleukin 18 | IL12B IL1R1 IL18 |

Extracellular, cytosol, mitochondria | Cytokine-mediated signaling pathway | IL-12(P40)2 DIAGRAM EPIC-InterActs |

Multiple sclerosis, liver cirrhosis, hypothermia, reperfusion injury, glioma, asthma, diabetes mellitus, skin diseases, hypersensitivity, brain ischemia, pneumonia | a) PEDF-induced signaling b) TGF-β pathway c) Allograft rejection Toll-like receptor signaling pathway d) Akt signaling e) PEDF-induced signaling f) ERK signaling.74 |

| Kinase and transferase | Glycogen synthase kinase 3-β, Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3 kinase, catalytic subunit-α, AKT1, Glucokinase (Hexokinase 4) | GSK3B PIK3CA AKT1 GCK |

Plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, extracellular, Golgi apparatus, nucleus, peroxisome, cytoskeleton, vacuole, endosome | Cellular response to stress, signal transduction, hemostasis, signal transduction via activation of PIK3 pathway | CHIR, SB216763, TWS119, Eplerenone | Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, prostatic neoplasm, depressive disorder, myocardial infarction, muscular atrophy, kidney injury, heart failure, arthritis, Parkinson disease, carcinoma, polycystic ovary syndrome, liver cirrhosis | a) Signaling by FGFR b) PI-3K cascade c) Translation Insulin regulation of translation d) Development HGF signaling pathway e) Insulin receptor signalling cascade f) Signaling by Interleukins g) Apoptotic pathways h) Regulation of β-cell development i) Metabolism j) Activation of cAMP-Dependent PKA |

Note: ‘–’ indicates growth factor does not have associated drug(s).

Abbreviations: BTD, biotidinase deficiency; cAMP: Cyclic adenosine monophosphate; ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinase; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptors; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1; GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; HGF, Hepatocyte growth factor; PI-3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PEDF, pigment epithelium-derived factor; TGF-Beta, transforming growth factor β; TWEAK, TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B.

Table 2.

Classification of diabetic therapeutic targets according to molecular mechanism

| Targets | Gene | Subcellular locations | Molecular function | Biological process | Associated drug(s) | Related disease(s) with this gene | Associated pathways | Gene that shares disease with this gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islet amyloid polypeptide | IAPP | Extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, plasma membrane | Signaling molecule, signal transduction | Aggregation of amylin in insoluble amyloid fibrils and corresponds to insulin resistance | Pramlintide exenatide amylinamide | Diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, hypertension, stomach ulcer, primary malignant, neoplasm | 1) Signaling by GPCR 2) PEDF induced signaling 3) ERK signaling 4) Akt signaling |

TP53 TNF VEGFA BCL2 IL6 INS |

| ATP-sensitive potassium channel | KCNJ11 | Extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, plasma membrane, cytoskeleton | Cation channel | Cation transport | Repaglinide, Nateglinide, Sulfonylurea | Diabetes mellitus, seizures, neonatal diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, nesidioblastosis, hypertension, parkinsonian disorders, sciatic neuropathy, obesity | 1) Type-II diabetes mellitus 2) Integration of energy metabolism 3) Inwardly rectifying K+ channels 4) Metabolism |

INS-IGF2 IL6 VEGFA IL6 TNF ACE APOE INS-IGF2 PPARG MTHFR |

| Heat shock protein | HSPD1 | Plasma membrane, cytosol, endosome, extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, nucleus, chloroplast, vacuole | Chaperone | Protein metabolism | 6-podoacetamido, subrem, fleroscinse | Endotoxemia, HIV infection, adenocarcinoma, acute coronary syndrome, cardiomyopathy, infarction | 1) Biosynthesis of the N-glycan precursor 2) SIDS susceptibility pathways 3) Legionellosis Validated targets of C-MYC transcriptional activation |

TNF IL6 IL10 IL1B IL1A IFNG MMP9 TLR4 VEGFA CCL2 CXL2 PTGS2 CXCL2 IL1RN |

| Insulin sensitizer | INS | Plasma membrane, cytosol, endosome, extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, nucleus, chloroplast, vacuole | Signaling molecule | Protein metabolism | Metformin sulfonylureas cholesterol | Diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, hyperinsulinism, hypertension, glucose intolerance | 1) I nsulin receptor signalling cascade 2) Translation insulin regulation of translation 3) Regulation of β-cell development 4) Ras signaling pathway |

INS-IGF2 IL6 TNF TP53 VEGFA IGF1 IL1B TGFB1 ACE BCL2 APOE |

| Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein | MTTP | Endoplasmic reticulum, extracellular, cytosol, Golgi apparatus, nucleus, plasma membrane, cytoskeleton | Other transporter, transfer/carrier protein | Lipid metabolism and other transport | CP-346086 | Abetalipoproteinemia, fatty liver, abdominal obesity, hyperlipidemias, leukemia, cardiovascular disease | 1) Lipoprotein metabolism 2) Metabolism 3) Statin pathway 4) Fat digestion and absorption |

TNF IL6 TP53 INS-IGF2 INS VEGFA MTHFR IL1B IL10 |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase1 | PTP1B | Endoplasmic reticulum, cytosol, nucleus, cytoskeleton, plasma membrane, endosome | – | Leptin and insulin signaling pathways | BVT948 TCS401 Alexidine dihydrochloride | Obesity, insulin resistance, insulin sensitivity | – | – |

| Carbonyl reductase1 | CBR1 | Cytosol, nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria | Reductase | – | – | Pulmonary hypertension, breast neoplasm, pulmonary venocclusive disease, hyperandrogenism, pulmonary hypertension, reperfusion injury, diabetes mellitus, Type-II | 1) Metabolism 2) Arachidonic acid metabolism 3) Chemical carcinogenesis 4) Doxorubicin pathway |

VEGFA TGFB1 TNF1 MMP9 IL6 TP53 PPARG HIF1A MTHFR PTGS2 |

| Alpha glucosidase | GAA | Plasma membrane, cytosol, endosome, extracellular, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, nucleus | Hydrolase | – | Acabose, miglitol, voglibose | Glycogen storage, left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiomyopathy, ventricular dysfunctioning, ataxia, neurodegenerative disease, diabetes mellitus, heart disease | 1) Metabolism 2) Notch-mediated HES/HEY network Development 3) VEGF signaling via VEGFR2 – generic cascades Glucuronidation |

TNF IL6 INS VEGFA INS-IGF2 ACE AR IL1B IGF1 TP53 APOE PIK3CA IL10 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor B | VEGFB | Extracellular, mitochondria, nucleus | Signling molecule | Hemostasis | – | Retinal vein occlusion, brain injury, atherosclerosis, hypertrophy, inflammation, tumor progression | 1) Apoptotic pathways 2) Synovial Fibroblasts 3) GPCR pathway 4) TGF-β pathway 5) ERK signaling 6) CREB pathway |

VEGFA IL6 TNF MMP9 PTGST2 IGF1 MMP2 PPARG CCL2 TIMP1 THBS1 |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type F | PTPRF | Plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, extracellular, golgi apparatus, nucleus, peroxisome | Hydrolase Phosphatase | – | Stomach neoplasm, obesity, acromegaly, pheochromocytoma, breast carcinoma, melanoma, carcinoma, amastia | 1) PAK pathway 2) Insulin signaling 3) Translation insulin regulation of translation |

TP53 MYC EGF EGFR ESR1 IGF1 IL6 PIK3CA BCL2 STAT4 |

|

| Signal-regulatory protein-α | SIRPA | Plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, extracellular, nucleus, peroxisome, cytoskeleton | Signaling molecule | Hemostasis | – | Schizophrenia, brain neoplasms, carcinoma, precancerous conditions, autoimmune diseases | 1) Cell junction organization 2) Hemostasis 3) Cardiac progenitor differentiation 4) Cell surface interactions at the vascular wall 5) Osteoclast differentiation |

TNF SR1 CDKN2A PTGS2 L10 FNG |

SIRT-1: insulin resistance and insulin availability

SIRT-1 refers to sirtuin (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog)-1. It is a member of sirtuin protein family known as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) – dependent histone deacetylase, which is preserved in evolution from bacteria to humans.19 In human, seven different types of sirtuin are present. SIRT-1 is a protein deacetylase present in the cytoplasm and nucleus of cell. SIRT-1 is widely studied for its effects in various metabolic disorders. SIRT-1 utilizes oxidized NAD as a cofactor and is negatively regulated either by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide or its deacetylation product nicotinamide.20 SIRT-1 deacetylates various substances, including uncoupling protein 2 (UCP-2) and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma co-activator 1α (PGC-1α). SIRT-1 also exhibits control over metabolic tissues such as skeletal muscles, liver and adipose tissues.21 The UCP2 is a specific uncoupling protein present in the inner membrane of brown adipocytes’s mitochondria and acts as negative regulator of insulin secretion. However, PGC-1α is the main regulator of glucose production in the liver that controls the entire gluconeogenic pathway.22 Interestingly, SIRT-1 is prominently expressed in β-cells of pancreas. SIRT-1 regulates the insulin secretion and sensitizes the peripheral tissues to the action of insulin.23,24 SIRT-1 regulates the PPAR-γ expression and thereby controls the process of adipogenesis and fat storing in the adipose tissues.25 Additionally, SIRT-1 plays an important role in the differentiation of muscle cells and regulation of metabolism in the liver. Therefore, extensive involvement of SIRT-1 in the control and regulation of insulin action describes its significance as a therapeutic target in Type-II DM.

SIRT-1: overproduction of ATP

SIRT-1 is located in the cytoplasm and nucleus of pancreatic β-cells. Moynihan et al observed that suppression of UCP-2 due to over expression of SIRT-1 in pancreatic β-cells of mice enhances the production of ATP.26 SIRT-1 increases the insulin secretion with some reduction in the glycolytic flux. The oxidative phosphorylation and suppression of mitochondrial UCP-2 uncoupling were proposed as the cause of elevated ATP levels. Whereas, Guarente and Kenyon27 observed that decreased SIRT-1 activity and elevated mitochondrial protein UCP-2 level causes significant reduction in the ATP production. PGC-1α is a transcriptional co-activator that favorably modulates the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through the stimulation of activity of gluconeogenic genes and suppression of activity of glycolytic genes. The β-cells of pancreas secrete both SIRT-1 and PGC-1α in small quantities. Gerhart Hines et al28 reported that SIRT-1 causes activation of PGC-1α and exhibits inhibitory effect on glucose metabolism in liver. Sirtuin agonists enhance the metabolic efficiency through increased insulin secretion and/or improved insulin sensitivity.29,30 Sirtuin causes the extension of life span and improvement of metabolism in simple organisms. It suggests the role of sirtuin pathway as a therapeutic target in metabolic diseases. However, rigorous genetic tests that need to confirm the ability of sirtuin as modulator of metabolism are still awaited.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B: a dynamic player in insulin resistance

Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), belongs to the family of PTP enzymes encoded by Ptpn1 gene. It is a ubiquitously expressed, monomeric enzyme having 435 amino acids with molecular weight of 50 kDa.31,32 Dephosphorylated PTP1B regulates the important cell signaling events during cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis.32 Structurally, the N-terminal domain of PTP1B consists of two aryl phosphate-binding sites namely a high-affinity catalytic site that contains the nucleophile cysteine residue and low-affinity non-catalytic site containing the Arg24 and Arg254 residues.33 Whereas, the C-terminal domain of PTP1B includes proline residues and the hydrophobic amino acid residues 400–435. These residues are responsible for locating PTP-1B at the cytoplasmic phase of the endoplasmic reticulum.34 In insulin signaling pathway, PTP1B dephosphorylates several substrates such as tyrosine residues 1,162 and 1,163, which causes subsequent termination of receptor tyrosine kinase cascade. The binding of insulin to the insulin receptor (IR) phosphorylates the IR subunit 1 and causes the down-regulation of insulin signaling pathway.35 Moreover, PTB1B controls the interaction between IRS1 and IRS2, which modulates the hepatic insulin action and insulin sensitivity.36 Thus, PTB1B plays a vital role in the insulin resistance and it is one of the important therapeutic targets in Type-II DM.

PTP1B inhibitors

It is evident that decreased PTP1B activity is related to increased insulin activity, which has a protective effect in diabetes.37 The PTP1B is a negative regulator of insulin signaling. The ability of PTP1B inhibitors to prolong the actions of insulin denotes their potential in the management of Type-II DM.38 Ertiprotafib belongs to the class of compounds that potently inhibit the PTP1B activity and normalizes plasma glucose and insulin levels in genetically diabetic and/or obese animals in experimental models of Type-II DM.39 One of the synthetic trissulfotyrosyldodecapeptides inhibited the IR dephosphorylation and enhanced the insulin signaling in Chinese hamster ovary cells over expressing human IRs.40

Sodium-glucose linked transporter (SGLT): role in glucose transport and regulation

Type-II DM has complex and multifactorial pathophysiology. Decrease in insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells due to development of insulin resistance is the hallmark of Type-II DM. The insulin resistance in liver, brain and muscle leads to increased glucagon secretion, lipolysis and increased absorption of glucose by nephrons. Glucose is a vital source of energy for carrying out various cellular and metabolic processes. Lipoidal nature of cell membrane restricts the entry of polar glucose to extracellular region. Glucose is transported via two types of glucose transporters namely glucose transporter (GLUT) transporter and sodium-glucose transporter (SGT). There are 14 different types of GLUT transporters and 7 types of SGT are characterized. The GLUT transporter protein is a 12 membrane-spanning helical structure having amino and carboxyl terminals that are exposed on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane. GLUT facilitates passive transport of glucose according to concentration gradient. In contrast, sodium glucose co-transporter involves the active transfer of glucose across the cell membrane against concentration gradient at the use of energy. Among various types of SGLT, only SGLT-1 and SGLT-2 facilitate the reabsorption of glucose into the plasma. Thus, inhibition of this process is proposed to decrease the blood glucose level and promote glucosuria. The kidney plays an important role in the glucose homeostasis. In a healthy adult, about 180–190 g of glucose per day is filtered from the glomeruli.41 Out of this filtered glucose, about 95% is reabsorbed through SGLT and circulatory glucose levels are maintained.42 The up-regulation of SGLT-2 in Type-II DM causes increased transportation of glucose and subsequent hyperglycemia.

SGLT-2 inhibition: a prospect to amend our therapeutic strategy

It is well established that inhibition of glucose reabsorption from kidney tubules improves the glucose homeostasis.43 Recently, SGLT-2 inhibitors demonstrated their effect on glycemic control in animal models of diabetes as well as Type-II DM patients.44 Clinical evidence for dual inhibition of SGLT-1 and SGLT-2 is available.45 SGLT-1 is the chief intestinal glucose transporter that reabsorbs about 10% of total renal glucose.46 Functional deficit of SGLT-1 leads to glucose malabsorption, which is exhibited by gastrointestinal symptoms.47 As SGLT-1 inhibition is associated with glucose malabsorption, selective SGLT-2 inhibitors were developed to avoid the SGLT-1-induced malabsorption state. SGLT-2 inhibitor decreases renal glucose reabsorption, increases urinary glucose excretion, improves the peripheral insulin sensitivity and enhances pancreatic β-cell function to maintain blood glucose levels.48,49

Besides control of blood glucose level, SGLT-2 inhibitors also reduce blood pressure, body weight and lower the risk of hypoglycemia.50 The glucose-lowering effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors is comparable with the effect of metformin and dipeptidyl peptidase-4, (DPP-4) inhibitors when used as monotherapy. Thus, SGLT-2 inhibitors are suggested as alternative first-line therapeutic agents when metformin cannot be used. The first SGLT-2 inhibitor, canagliflozin was approved by the FDA in March 2013.51 Canagliflozin was studied in Type-II DM patients and compared clinically with standard antidiabetic drugs like metformin, glimepiride, sitagliptin, pioglitazone, etc. In phase III trial, canagliflozin at the dose of 100 mg and 300 mg showed the favorable effects in Type-II DM patients. Following the approval of canagliflozin, another SGLT-2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin is approved by the FDA for use in adults with Type-II DM in January 2014.52 The clinical efficacy and safety of the dapagliflozin as a SGLT-2 inhibitor were extensively studied using 14 clinical trials and evidence is widely documented.53–55 Similarly, other molecules such as ipragliflozin and ertugliflozin are in development pipeline and currently at phase III trials.56

GSK-3: constructive treats

Glycogen synthase, is a rate limiting enzyme involved in glycogen biosynthesis. GSK-3 was identified in the late 1970s, and possesses an ability to phosphorylate the glycogen synthase.57,58 The GSK-3 is conserved signaling molecule that belongs to serine/threonine kinases. It has an important role in diverse biological processes. It was observed that abnormal GSK-3 activity is associated with multiple human pathologies such as diabetes, psychiatric diseases, neurode-generative and inflammatory diseases.59 This observation laid down the foundation of hypothesis that GSK-3 inhibition has therapeutic benefits in various ailments. It has directed the research toward the discovery and design of selective GSK-3 inhibitors. The reported GSK-3 inhibitors include small molecules isolated from natural and marine sources or obtained from chemical synthesis. These inhibitors may act through multiple mechanisms, including competitive or non-competitive inhibition of ATP. Academic and industrial efforts have been made toward the discovery and development of novel GSK-3 inhibitors.60 Several chemical families with great structural diversity are reported to emerge as GSK-3 inhibitors. The number of small molecule GSK-3 inhibitors is on continuous rise and most of these inhibitors are in the early discovery phase.

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt

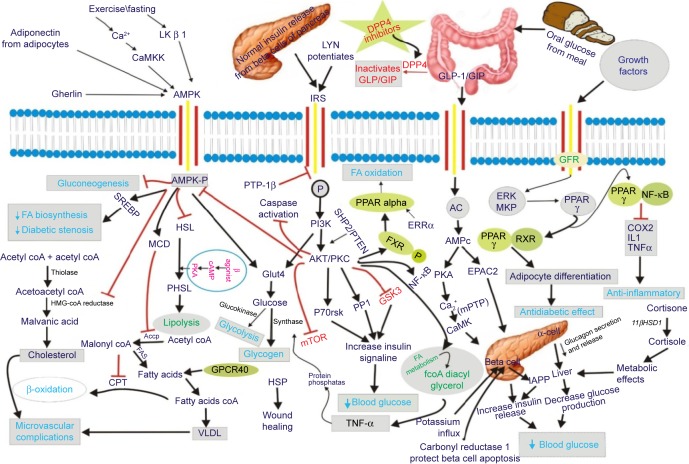

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and its downstream effector, serine-threonine protein kinase (Akt) are chief signaling enzymes implicated in cell survival and metabolic control.61,62 The phosphorylation of downstream apoptotic molecules such as BAX, Bcl-2-associated death promoter (BAD) and GSK-3β by PI3K/Akt elicit potent anti-apoptotic effect. The PI3K/Akt pathway is responsible for insulin-mediated glucose metabolism as well as protein synthesis and inactivation of its downstream target GSK-3, which is crucial for glucose sensing and β-cell growth.63 Thus, GSK-3 β can be the possible target for β-cell protective agents.64 Wortmannin, an antagonist of PI3K through down-regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling, inhibited the cell proliferation and induced the apoptosis.65 Different mechanisms and biological targets involved in Type-II DM are presented as Figure 1 and Table 3.

Figure 1.

Involvement of different mechanisms for Type-II diabetes with targets.

Abbreviations: 11βHSD1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1; AC, adenylyl cyclase; Accp, acyl carrier protein; AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide nucleotide; AMPc, cyclic AMP; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; AMPK-P, phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase; CaMKK, calcium mediated mitogen protein kinase kinase; coA, coenzyme A; COX2, cyclooxygenase2; CPT, carnitine palmitoyltransferase; DAG, Di-acyl glycerol; DM, diabetes mellitus; DP4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; DPP4, inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase 4; EPAC2, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; ERRα, estrogen-related receptor-α; FA, fatty acid; FAS, fatty acid synthetase; fcoA, fluoroacetyl coenzyme A; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GFR, growth factor receptor; GIP, gastric inhibitory polypeptide/glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; GPCR40, G-protein-coupled receptor 40 family; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; HSL, hormone sensitive lipase; HSP, heat shock protein; IAPP, amylin, or islet amyloid polypeptide; IL1, interleukin 1; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; LK, β 1 tumour suppressor kinase; LYN, belongs to Src family of protein tyrosin kinase; MCD, malonyl-CoA decarboxylase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NF-κB, nuclear factor NF-kappa B; P, phosphorylation; P70rsk, p70 ribosomal S6 kinases; PHSL, P-hormone-sensitive lipase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PP1, protein phosphatase 1; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PTP-1β, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1β; RXR, retinoid X receptor; SGT, sodium glucose transporter; SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding proteins; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; UKPDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study; VLDL, very low density lipoprotein.

Table 3.

Distribution of therapeutic targets of diabetes mellitus

| Molecular function | No of targets | Biological process | No of targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine kinase | 1 | Phosphorylation | 1 |

| Dehydrogenase | 1 | Lipid metabolism | 1 |

| Growth factor | 1 | Homeostasis | 2 |

| Transport | 2 | Insulin resistance | 2 |

| Serine/threonine kinase | 2 | Transport and uptake | 2 |

| Ligase | 2 | Fatty acid oxidation | 2 |

| Transfer carrier protein | 2 | Insulin release | 3 |

| Oxidoreductase | 2 | Signal transduction | 4 |

| Signaling molecule | 3 | Protein metabolism | 5 |

| Interleukin receptor | 3 | Cytokine mediated | 5 |

| Transcription factor | 4 | Other metabolism | 5 |

| Hydrolase and protease | 4 | ||

| G-protein-coupled receptor | 5 | ||

| Kinase/Transferase | 7 |

Discontinued drugs

Diabetes is the 6th major cause of worldwide deaths.66 Alarming increase in the incidence of diabetes demands for successful therapies. American biopharmaceutical research organizations are engaged in the development of about 180 new medicines for diabetes and related conditions. Currently, about 200 clinical trials on diabetic patients are ongoing in USA. Promising leads from the development pipeline have shown a hope for the control of diabetes complications at an affordable cost. However, failure of drugs to demonstrate promising results in the clinical trials and incidences of market withdrawal have resulted in the decline in interest of major pharmaceutical companies in diabetes research. In between 2012 and 2013 and in 2014, ~22 and 14 antidiabetic drugs were discontinued from various phases of drug development. Details of these discontinued drugs are described in Table 4. Piramal Life Sciences discontinued the development of three antidiabetic drugs namely, P-11187, P-1736–05 and P-7435 in 2014. The P-11187 is G-protein-coupled receptor 40 (GPCR40) agonist, which showed promising results in Type-II diabetes. It acts through the stimulation of glucose-induced insulin secretion.67 P-11187 was described as an oral, highly selective and potent partial agonist of human, rat and mouse GPCR40 with effective concentration 50 (EC50) value of 14.4, 2.53 and 4.25 nM, respectively.68 P-1736-50 was considered as a PPAR-γ activator, but in preclinical studies, it failed to demonstrate its efficacy and hence was discontinued from further research. Piramal Life Sciences also discontinued the development of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 inhibitor P-7435 due to business focus. Similarly, Takeda discontinued TAK-875 (Fasiglifam) due to its hepatotoxic potential in phase III clinical trial. The MK-0893 is another molecule discontinued from the development process by Merck due to safety issues. Glucokinase is a major enzyme that phosphorylates glucose into glucose-6-phosphate. It is essential for glycogenesis and plays an important role in the hepatic glucose clearance. In 2013, Takeda was developing TAK-329 as glucokinase activator, but due to unexpected reasons, Takeda discontinued the development of this drug. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and GIP are produced in intestine. The active forms of GLP and GIP increase the insulin secretion and regulate the glucose homeostasis. Upon release, GLP and GIP are immediately inactivated by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DP4) hence they have very short half-life.69 Therefore, the discovery of DP4 inhibitors is a promising approach toward the development of novel anti-diabetic drugs. The SYR-472 was a highly selective, long active DP4 inhibitor from Takeda that was discontinued due to its high development cost. Recently, Takeda has discontinued the development of combined PPAR-γ/α activator, sipoglitazar in phase III.70 Various anti-diabetic drugs that are discontinued from further research or withdrawn from the market are described in Table 4.

Table 4.

Discontinued anti-diabetic drugs

| Compound | Company | Mechanism | Status (phase) at discontinuation | Date of discontinuation | Reason for discontinuation | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-11187 | Piramal | GPCR40 agonist | Phase I | – | Business focus | Highly selective, potent and orally active partial agonist of free fatty acid receptor 1 (GPCR40). Act through potentiation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion | 68 |

| TAK-875 | Takeda | GPCR40 agonist | Phase III | 27 Dec 2013 | Hepatotoxicity | GPCR40 agonist having potential to cause liver injury | |

| P-7435 | Piramal | DGAT-1 inhibitor | Phase I | – | Business focus | Diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 1) inhibitor. Potential to treat dyslipidemia and elevated glycemia in Type-II diabetes | 75 |

| P-7436 | Piramal | Unknown | Preclinical | Business focus | Initially designated as PPAR-γ activator but it failed to demonstrate this activity in preclinical studies | ||

| NN1954 and NN1956 | Novo Nordisk | Oral insulin (to supply baseline insulin) | Phase I | – | Not disclosed | Long-acting insulin analogs delivered by oral tablets by so-called gastrointestinal permeation enhancement technology | 68 |

| MK-0893 | Merck | Glucagon receptor antagonist | Phase II | – | Unexpected toxicity | Demonstrated toxicity in clinical studies like increased levels of LDL & transaminase, elevated blood pressure and body weight | |

| BMS-788 (XL-652) | BMS (Exelixis) | Liver X Receptor (LXR) partial agonist | Phase I | 03 Jan 2014 | Not disclosed | LXR is a novel target for impacting cardiovascular and metabolic disorders acting through cholesterol transport. BMS-788 is a small-molecule agonist of LXR | 68 |

| Betatrophin | Janssen | β-cell trophin | Preclinical | – | Not disclosed | Betatrophin has role in the growth of pancreatic β-cells | |

| LY-2382770 | Eli Lilly | TGF-β mAb | Phase II | 21 Apr 2014 | Not disclosed | Demonstrated nephroprotective effect in both Type-1 and Type-II diabetic subjects | 68 |

| DiaPep227 (AVE-0277) | Hyperion | Heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60)-derived peptide | Phase III | – | Data integrity | Effective in the prevention and treatment of Type-1 diabetes and autoimmune Type-II diabetes | |

| AJD-101 | Ajinomoto/Daiichi Sanko | Insulin secretagogue | Phase II | 02 Dec 2008 | Unspecified | Stimulates insulin independent glucose uptake through the activation of insulin signaling pathway | |

| KRP-104 | Kyorin/ActiveX | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor | Phase II | – | Business focus | Acts through elevation of incretins. Discontinued due to strategic decision of company |

68 |

| NN9223 | Novo Nordisk | GLP-1 agonist | Phase II | 21 Jun 2012 | Dropped in favor of new candidate semaglutide | Acts through incretin pathways | |

| PF-04991532 | Pfizer | Glucokinase activator | Phase II | 10 May 2012 | Unspecified | Hepatoselective glucokinase activator | 68 |

| PSN-821 | Astellas/OSI Pharmaceuticals | GPR119 agonist | Phase II | 04 Feb 2013 | Unspecified | GPR119 receptors are G-protein coupled receptors that respond to fatty acids and stimulate insulin secretion | 68 |

| Tagatose | Spherix/Biospherics | Hexose (fructose epimer) | Phase III | – | Failure to comply with regulatory requirements | It is a naturally occurring monosaccharide and functional sweetener | 75 |

| Tesaglitazar AZ-242 | AZ | PPAR-α and PPAR-γ agonist | Phase III | May 2006 | Adverse events | Demonstrated adverse effects like elevated serum creatinine and decreased glomerular filtration rate | |

| Muraglitazar; BMS-298585 | BMS | PPAR-α and PPAR-γ agonist | Phase III | May 2006 | Adverse events | Showed cardiovascular side effect | |

| CYT009-GhrQb | Cytos Biotechnology | Ghrelin | Phase II | 07 Nov 2006 | Poor efficacy | CYT009-GhrQb is a vaccine | |

| R-1438 | Hoffmann-La Roche | Unspecified | Phase II | 19 Oct 2006 | Poor efficacy | – | |

| Sipoglitazar (TAK-654) | Takeda | Unspecified | Phase II | 12 Sep 2006 | Poor efficacy and adversity | – | |

| Troglitazone | Daiichi Sankyo | PPAR-α and PPAR-γ agonist | – | 21 March 2000 | Hepatotoxicity | About 63 liver failure deaths are linked with the use of troglitazone | 76 |

| Pioglitazone | Takeda | PPAR-γ agonist | – | 2011 (France) 2013 (India) |

Bladder cancer | Withdrawn from market due to increased risk of bladder cancer in patients taking Actos (pioglitazone) for a long time for the treatment of Type-II diabetes mellitus | 5 |

| Phenformin | Ciba-Geigy | AMP-activated protein kinase | – | October 1976 | Lactic acidosis | Withdrawn from market due to potential to cause lactic acidosis |

Note: ‘–’ indicates the date of discontinuation of drug is unclear.

Abbreviations: AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; GPCR-40, G-protein-coupled receptor 40; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; LDL, low density lipoproteins; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Conclusion

Scientific studies encircling the diabetes and its complications are on continuous rise. The annual cost of diabetes to the USA health care system is $100 billion. Despite the availability of numerous antidiabetic drugs, search for the novel leads that completely cure Type-II DM is an ongoing quest. The disease architecture in Type-II DM is so complicated that even magic bullets, which selectively target one protein, fail to restore the biological network to healthy state. The current research scenario highlighted the need for identification and exploration of therapeutic targets in Type-II DM. Successful modulation of these biological targets can result in the cure of diabetes and associated complications. The present review provides an overview of therapeutic targets and their role in Type-II DM. This information can be used to plan the therapeutic strategies for the management of Type-II DM.

Search strategy

We searched data bases like PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Gene cards and DisGenNET along with proceedings available on websites of the American Diabetes Association and European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Full text articles published between 1980 and 2016 and written in English are included in present review. Databases were searched with keywords like names of target, gene, discontinued drugs, drugs withdrawn from market and inhibitors in development.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support received under Young Scientist Research Scheme (File no SB/YS/LS-114/2013) of Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, India. Also, the research support from the University Program for Advanced Research (UPAR) and Center-Based Interdisciplinary grants from the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor of Research and Graduate Studies of United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, UAE to Shreesh Ojha is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mali A, Bhise S, Katyare SS. Omega-3 fatty acids and diabetic complications. Omega-3 fatty acids. Springer. 2016:221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guariguata L, Whiting D, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw J. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassanzadeh V, Mehdinejad MH, Ferrante M, et al. Association between polychlorinated biphenyls in the serum and adipose tissue with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci. 2016;5(9):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Nogueiras R. Endocrine control of energy homeostasis. Mole Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolen S, Feldman L, Vassy J, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and safety of oral medications for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(6):386–399. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox CS, Coady S, Sorlie PD, et al. Increasing cardiovascular disease burden due to diabetes mellitus. Circ. 2007;115(12):1544–1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandyopadhyay P. Cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus. Drug News Perspect. 2006;19(6):369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nat. 2001;414(6865):813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1333–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeFronzo RA, Bonadonna RC, Ferrannini E. Pathogenesis of NIDDM: a balanced overview. Diabetes Res. 1992;15(3):318–368. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phung OJ, Scholle JM, Talwar M, Coleman CI. Effect of noninsulin antidiabetic drugs added to metformin therapy on glycemic control, weight gain, and hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2010;303(14):1410–1418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzoulaki I, Molokhia M, Curcin V, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes prescribed oral antidiabetes drugs: retrospective cohort study using UK general practice research database. Brit Med J. 2009;339:b4731. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Staa T, Abenhaim L, Monette J. Rates of hypoglycemia in users of sulfonylureas. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(6):735–741. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinetti G, Lestavel S, Bocher V, et al. PPAR-α and PPAR-γ activators induce cholesterol removal from human macrophage foam cells through stimulation of the ABCA1 pathway. Nat Med. 2001;7(1):53–58. doi: 10.1038/83348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aulinger BA, Bedorf A, Kutscherauer G, et al. Defining the role of GLP-1 in the enteroinsulinar axis in type 2 diabetes using DPP-4 inhibition and GLP-1 receptor blockade. Diab. 2014;63(3):1079–1092. doi: 10.2337/db13-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali A, Hoeflich KP, Woodgett JR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3: properties, functions, and regulation. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2527–2540. doi: 10.1021/cr000110o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: functional insights from cell biology and animal models. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:40. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ring DB, Johnson KW, Henriksen EJ, et al. Selective glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors potentiate insulin activation of glucose transport and utilization in vitro and in vivo. Diab. 2003;52(3):588–595. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zillikens MC, van Meurs JB, Rivadeneira F, et al. SIRT1 genetic variation is related to BMI and risk of obesity. Diab. 2009;58(12):2828–2834. doi: 10.2337/db09-0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibiger IB, Berggren PO. A SIRTain role in pancreatic beta cell function. Cell Metab. 2005;2(2):80–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Sun X, Hua L, et al. SIRT1 gene polymorphisms are associated with growth traits in Nanyang cattle. Mol Cell Probes. 2013;27(5–6):215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, et al. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature. 2003;423(6939):550–555. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun C, Zhang F, Ge X, et al. SIRT1 improves insulin sensitivity under insulin-resistant conditions by repressing PTP1B. Cell Metab. 2007;6:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bordone L, Motta MC, Picard F, et al. Correction: Sirt1 regulates insulin secretion by repressing UCP2 in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS Biol. 2015;13(12):e1002346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finck BN, Kelly DP. PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):615–622. doi: 10.1172/JCI27794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moynihan KA, Grimm AA, Plueger MM, et al. Increased dosage of mammalian Sir2 in pancreatic beta cells enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice. Cell Metab. 2005;2(2):105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guarente L, Kenyon C. Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nat. 2000;408(6809):255–262. doi: 10.1038/35041700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerhart-Hines Z, Rodgers JT, Bare O, et al. Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through SIRT1/PGC-1alpha. EMBO J. 2007;26(7):1913–1923. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haigis MC, Guarente LP. Mammalian sirtuins – emerging roles in physiology, aging, and calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 2006;20(21):2913–2921. doi: 10.1101/gad.1467506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell. 2006;127(6):1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid B, Wimmer M, Tag C, Hoffmann R, Hofer HW. Protein phosphotyrosine phosphatases in Ascaris suum muscle. Mol Biochem Parasito. 1996;77(2):183–192. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adachi M, Sekiya M, Arimura Y, et al. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase expression in pre-B cell NALM-6. Cancer Res. 1992;52(3):737–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi T, Cleveland JL, Ihle JN. Identification of novel protein tyrosine phosphatases of hematopoietic cells by polymerase chain reaction amplification. Blood. 1991;78(9):2222–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JF, Gong K, Wei DQ, Li YX, Chou KC. Molecular dynamics studies on the interactions of PTP1B with inhibitors: from the first phosphate-binding site to the second one. Prot Engineer Des Sel. 2009;22(6):349–355. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakke J, Haj FG. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B substrates and metabolic regulation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;37:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picha KM, Patel SS, Mandiyan S, Koehn J, Wennogle LP. The role of the C-terminal domain of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B in phosphatase activity and substrate binding. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(5):2911–2917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, Mas Gutierrez JA, Sanz-Gonzalez S, Ros M, Burks DJ, Valverde AM. Inhibition of PTP1B restores IRS1- mediated hepatic insulin signaling in IRS2-deficient mice. Diabetes. 2010;59(3):588–599. doi: 10.2337/db09-0796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang ZY, Lee SY. PTP1B inhibitors as potential therapeutics in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Expert Opin Investig Drug. 2003;12(2):223–233. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erbe DV, Wang S, Zhang YL, et al. Ertiprotafib improves glycemic control and lowers lipids via multiple mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(1):69–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.005553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kole HK, Garant MJ, Kole S, Bernier M. A peptide-based protein-tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor specifically enhances insulin receptor function in intact cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(24):14302–14307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliva RV, Bakris GL. Blood pressure effects of sodium-glucose co-transport 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. J Am Soc Hyperten: JASH. 2014;8(5):330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polidori D, Sha S, Mudaliar S, et al. Canagliflozin lowers postprandial glucose and insulin by delaying intestinal glucose absorption in addition to increasing urinary glucose excretion: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2154–2161. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujimori Y, Katsuno K, Nakashima I, et al. Remogliflozin etabonate, in a novel category of selective low-affinity sodium glucose cotransporter (SGLT2) inhibitors, exhibits antidiabetic efficacy in rodent models. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2008;327(1):268–276. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zambrowicz B, Freiman J, Brown PM, et al. LX4211, a dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor, improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(2):158–169. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sands AT, Zambrowicz BP, Rosenstock J, et al. Sotagliflozin, a Dual SGLT1 and SGLT2 Inhibitor, as Adjunct Therapy to Insulin in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(7):1181–1188. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koepsell H. The Na+-D-glucose cotransporters SGLT1 and SGLT2 are targets for the treatment of diabetes and cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;170:148–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fiscaletti M, Lebel MJ, Alos N, Benoit G, Jantchou P. Two cases of mistaken polyuria and nephrocalcinosis in infants with glucose-galactose malabsorption: a possible role of 1,25(OH)2D3. Horm Res Paediatr. 2017 doi: 10.1159/000454951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mather A, Pollock C. Glucose handling by the kidney. Kidney Int Suppl. 2011;(120):S1–S6. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeFronzo RA. Insulin and renal sodium handling: clinical implications. Int J Obes. 1981;5(Suppl 1):93–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.List JF, Whaley JM. Glucose dynamics and mechanistic implications of SGLT2 inhibitors in animals and humans. Kidney Int Suppl. 2011;(120):S20–S27. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilding JP, Norwood P, T’Joen C, Bastien A, List JF, Fiedorek FT. A study of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving high doses of insulin plus insulin sensitizers: applicability of a novel insulin-independent treatment. Diab Care. 2009;32(9):1656–1662. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaku K, Inoue S, Matsuoka O, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin as a monotherapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japanese patients with inadequate glycaemic control: a phase II multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diab Obes Metab. 2013;15(5):432–440. doi: 10.1111/dom.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji L, Ma J, Li H, et al. Dapagliflozin as monotherapy in drug-naive Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, blinded, prospective phase III study. Clin Ther. 2014;36(1):84–100.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henry RR, Murray AV, Marmolejo MH, Hennicken D, Ptaszynska A, List JF. Dapagliflozin, metformin XR, or both: initial pharmacotherapy for type 2 diabetes, a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(5):446–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim GW, Chung SH. Clinical implication of SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Arch Pharmacol Res. 2014;37(8):957–966. doi: 10.1007/s12272-014-0419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang QM, Fiol CJ, DePaoli-Roach AA, Roach PJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta is a dual specificity kinase differentially regulated by tyrosine and serine/threonine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(20):14566–14574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodgett JR, Cohen P. Multisite phosphorylation of glycogen synthase. Molecular basis for the substrate specificity of glycogen synthase kinase-3 and casein kinase-II (glycogen synthase kinase-5) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;788(3):339–347. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 7):1175–1186. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xie H, Wen H, Zhang D, et al. Designing of dual inhibitors for GSK-3beta and CDK5: virtual screening and in vitro biological activities study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(11):18118–18128. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dudek H, Datta SR, Franke TF, et al. Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine-threonine protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;275(5300):661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ravingerova T, Matejikova J, Neckar J, Andelova E, Kolar F. Differential role of PI3K/Akt pathway in the infarct size limitation and antiarrhythmic protection in the rat heart. Mol cell Biochem. 2007;297(1–2):111–120. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yin D, Woodruff M, Zhang Y, et al. Morphine promotes Jurkat cell apoptosis through pro-apoptotic FADD/P53 and anti-apoptotic PI3K/Akt/NF-kappaB pathways. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;174(1–2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crouthamel MC, Kahana JA, Korenchuk S, et al. Mechanism and management of AKT inhibitor-induced hyperglycemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(1):217–225. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mussmann R, Geese M, Harder F, et al. Inhibition of GSK3 promotes replication and survival of pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(16):12030–12037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.World Health Organization . Investing to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases: Third WHO Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases. World Health Organization; 2015. [Accessed January 28, 2017]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/152781/1/9789241564861_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hedrington MS, Davis SN. Discontinued in 2013: diabetic drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23(12):1703–1711. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.964859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colca JR. Discontinued drug therapies to treat diabetes in 2014. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015;24(9):1241–1245. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.1058777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim NH, Yu T, Lee DH. The nonglycemic actions of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:368703. doi: 10.1155/2014/368703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abel T, Feher J. A new therapeutic possibility for type 2 diabetes: DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin) Orv Hetil. 2010;151(25):1012–1016. doi: 10.1556/OH.2010.28910. Hungarian. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Doyle ME, Egan JM. Mechanisms of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 in the pancreas. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113(3):546–593. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vitku J, Starka L, Bicikova M, et al. Endocrine disruptors and other inhibitors of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 and 2: tissue-specific consequences of enzyme inhibition. J Ster Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;155(Pt B):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marx N, Schönbeck U, Lazar MA, Libby P, Plutzky J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators inhibit gene expression and migration in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1998;83(11):1097–1103. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mayer-Barber KD, Sher A. Cytokine and lipid mediator networks in tuberculosis. Immunol Rev. 2015;264(1):264–275. doi: 10.1111/imr.12249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colca JR. Discontinued drugs in 2012: endocrine and metabolic. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22(10):1305–1313. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.829038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Graham DJ, Green L, Senior JR, Nourjah P. Troglitazone-induced liver failure: a case study. Am J Med. 2003;114(4):299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01529-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]