Abstract

Exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, mitochondrial contents, and bacterial and viral products induces neutrophils to transition from a basal state into a primed one, which is currently defined as an enhanced response to activating stimuli. Although, typically associated with enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the NADPH oxidase, primed neutrophils show enhanced responsiveness of exocytosis, NET formation, and chemotaxis. Phenotypic changes associated with priming also include activation of a subset of functions, including adhesion, transcription, metabolism, and rate of apoptosis. This review summarizes the breadth of phenotypic changes associated with priming and reviews current knowledge of the molecular mechanisms behind those changes. We conclude that the current definition of priming is too restrictive. Priming represents a combination of enhanced responsiveness and activated functions that regulate both adaptive and innate immune responses.

Keywords: neutrophils, priming, cytokines, chemotaxis, apoptosis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst, exocytosis

Introduction

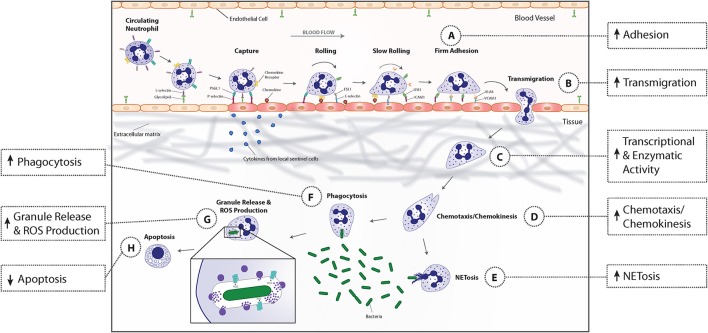

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes, or neutrophils, account for 40–60% of peripheral blood leukocytes in humans (Summers et al., 2010). They play an essential role in the innate immune response, as demonstrated by the development of life-threatening infections or uncontrolled inflammation in individuals with severe neutropenia or genetic disruption of neutrophil anti-microbial capabilities (Kannengiesser et al., 2008; van de Vijver et al., 2012; Moutsopoulos et al., 2014; Nauseef and Borregaard, 2014). Figure 1 shows the multistep process of neutrophil recruitment in response to microbial invasion, including adhesion to vascular endothelium, transmigration into the interstitial space, chemotaxis/chemokinesis toward the site of infection, phagocytosis of pathogens, destruction of microbes within phagosomes by release of antimicrobial granule contents following granule fusion and ROS generation at the phagosomal membrane, and amplification and organization of the inflammatory response. Uncontrolled or prolonged neutrophil activation uses antimicrobial responses to injure normal host cells, leading to pathologic changes to tissues and organs in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (Nathan, 2006). Consequently, neutrophil activation is normally tightly regulated.

Figure 1.

Priming-associated phenotypic changes and their effect on neutrophil functional responses. Neutrophils in circulating blood are in a resting state, characterized by a round morphology, non-adherence, minimal transcriptional activity, and a limited capacity to respond to activating stimuli. Microbial entry into tissues or tissue injury induces local immune cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines that modify endothelial cell adhesion molecule profile and enter the bloodstream to begin priming neutrophils. Upon exposure to these priming agents, neutrophils undergo an increase in enzymatic and transcriptional activity that results in activation and synthesis of inflammatory mediators and enzymes that mediate downstream phenotypic and functional changes. Immediately, neutrophils begin to change their adhesion receptor pattern by shedding selectins, fusing secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane which leads to increased integrin expression, and a rapid increase in the gene expression of several surface receptors that allows newly primed cells to more rapidly adhere to endothelial cells (A). This phenotypic change coupled with the release of granules containing matrix metalloproteases, promotes neutrophil migration into inflamed tissues (B). The priming process continues when neutrophils bind to extracellular matrix proteins (C). Binding of neutrophil extracellular matrix receptors leads to an increase in actin polymerization, available receptors from secretory vesicle degranulation, and intracellular signaling that results in enhanced chemotaxis and chemokinesis (D). When primed neutrophils encounter bacteria, their phagocytic capacity is increased due to the upregulation in the number and affinity of receptors on the plasma membrane (F). By then, ROS production, granule release (G), and NET formation (E) have been primed to augment microbicidal activities. Finally, priming prolongs neutrophil lifespan by activating anti-apoptotic signal transduction pathways and transcription factors that decrease transcription of pro-apoptotic factors (H).

Circulating neutrophils exist in a basal state, characterized by non-adherence, a round morphology, minimal transcriptional activity, and a limited capacity to respond to activating stimuli. That limited response protects against unwarranted inflammatory responses and tissue injury (Sheppard et al., 2005). To effectively clear invading organisms, neutrophils must be capable of mounting rapid, vigorous responses to activating stimuli. The transition to a state of enhanced responsiveness has been termed priming (Condliffe et al., 1998; El-Benna et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2013). It occurs in vitro following neutrophil exposure to pro-inflammatory lipids and cytokines, chemokines, mitochondrial contents, and bacterial and viral products (El-Benna et al., 2008). Neutrophil priming in vitro represents an in vivo phenomena, as primed neutrophils have been identified in humans with infections, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, traumatic injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Bass et al., 1986; McLeish et al., 1996; Ogura et al., 1999; Naegele et al., 2012). Although, substantial circumstantial evidence suggests that primed neutrophils participate in a number of human diseases, direct evidence is lacking. The relative contribution of neutrophil priming to the severity of human inflammatory diseases is an important gap in knowledge that needs to be addressed.

Historically, the term “priming” was primarily used to describe the augmented reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation upon neutrophil stimulation because of the depth of knowledge of molecular mechanisms of NADPH oxidase complex assembly, the ease of measurement of ROS generation, and the importance of ROS to anti-microbial activity. Figure 1 illustrates that primed neutrophils demonstrate a number of phenotypic changes in addition to enhanced NADPH oxidase activation, including granule release, cytokine and lipid synthesis, adhesion and transmigration, enhanced chemotaxis, and delayed apoptosis. Thus, neutrophil priming is not just a transition state in which neutrophils become more responsive to activating stimuli. We believe a new definition of priming is required to include the activation of a subset of neutrophil functions as opposed solely to a heightened state of responsiveness. In this review of the recent advances in neutrophil priming, we will highlight the functional evidence for the activation of a subset of neutrophil functions during priming and review the current state of knowledge of the molecular basis for those phenotypic changes to illustrate this new definition. Our goal is to encourage research that will provide a more complete understanding of priming, leading to identification of new targets for treatment of inflammatory and infectious diseases. Much of our discussion focuses on the effects of TNFα, as studies frequently use that cytokine as a model priming agent. The large number of agents capable of initiating priming of neutrophil respiratory burst activity was recently reviewed (El-Benna et al., 2016). We compare current state of knowledge of the effects of those priming agents on the various phenotypic changes to those induced by TNFα in Table 1.

Table 1.

Known priming agents' capacity to induce phenotypic changes in neutrophils.

| Priming Agent | Adhesion | Chemotaxis | Phagocytosis | Granule Release | NET formation | Apoptosis | Inflammatory Mediators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemoattractants | fMLF | ↑ (El Azreq et al., 2011) | ↑ Halpert et al., 2011 | ↑ Richardson and Patel, 1995 | ↑Uriarte et al., 2011 | ? | No change Klein et al., 2001 | ↑Browning et al., 1997 |

| C5a | ↑ Jagels et al., 2000 | ↑ Halpert et al., 2011 | ↑/↓ Morris et al., 2011; Tsuboi et al., 2011 | ↑ DiScipio et al., 2006 | ? | ↓ Perianayagam et al., 2002 | ↑ Finsterbusch et al., 2014 | |

| LTB4 | ↑ Eun et al., 2011 | ↑ Afonso et al., 2012 | ↑ Mancuso et al., 2001 | ↑ Kannan, 2002 | ? | ↓ Klein et al., 2001 | ↑ Finsterbusch et al., 2014 | |

| PAF | ↑ Kulkarni et al., 2007 | ↑ Shalit et al., 1987 | ↑ Rosales and Brown, 1991 | ↑ Andreasson et al., 2013 | ? | ↓ Khreiss et al., 2004 | ↑ Aquino et al., 2016 | |

| Cytokines | TNF-α | ↑ Bouaouina et al., 2004 | ↑ Montecucco et al., 2008 | ↑ Della Bianca et al., 1995 | ↑ McLeish et al., 2013, 2017 | ↑ Hazeldine et al., 2014 | ↑/↓ Murray et al., 1997 | ↑ Bauldry et al., 1991; Jablonska et al., 2002b |

| GM-CSF | ↑ Yuo et al., 1990 | ↑ Cheng et al., 2001 | ↑ Kletter et al., 1989 | ↑ Kowanko et al., 1991 | ↑ Yousefi et al., 2009 | ↓ Klein et al., 2000 | ↑ DiPersio et al., 1988b; Lindemann et al., 1988 | |

| IFN-γ | ↑ Klebanoff et al., 1992 | ↓ Aas et al., 1996 | ↑ Melby et al., 1982 | ↑ Cassatella et al., 1988 | ? | ↑ Perussia et al., 1987 | ↑ Humphreys et al., 1989 | |

| IL-1β | ↑ Brandolini et al., 1997 | ↑ Brandolini et al., 1997 | ? | ↑ Brandolini et al., 1997 | ? | ? | ? | |

| IL-8 | ↑ Detmers et al., 1990 | ↑ Baggiolini and Clark-Lewis, 1992 | ↑ Richardson and Patel, 1995 | ↑ Baggiolini and Clark-Lewis, 1992 | ↑ Hazeldine et al., 2014; Podaza et al., 2016 | ↓ Acorci et al., 2009 | ? | |

| IL-15 | ? | ↑ Mastroianni et al., 2000 | ↑ Musso et al., 1998 | ? | ? | ↓ Mastroianni et al., 2000 | ↑ Musso et al., 1998; Jablonska et al., 2001 | |

| IL-18 | ↑ Wyman et al., 2002 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↑ Wyman et al., 2002 | ↑ Jablonska et al., 2002a | |

| IL-33 | ? | ↑ Le et al., 2012 | ↑ Lan et al., 2016 | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Adiponectin | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| Microbial Products | LPS | ↑ Hayashi et al., 2003; Sabroe et al., 2003 | ↓/↑ Fan and Malik, 2003; Hayashi et al., 2003 | ↑ Hayashi et al., 2003 | ↑ Fittschen et al., 1988; Ward et al., 2000 | ↑ Hazeldine et al., 2014 | ↓ Klein et al., 2001 | ↑ Cassatella, 1995) |

| LAMs | ? | No change Fietta et al., 2000 | No change Fietta et al., 2000 | ↑ Faldt et al., 2001 | ? | ? | ? | |

| Lipopeptide | ↑ Hayashi et al., 2003; Sabroe et al., 2003 | ↓/↑ Aomatsu et al., 2008 | ↑ Hayashi et al., 2003 | ↑/↓ (Whitmore et al., 2016) | ? | Minimal effect Sabroe et al., 2003 | ↑/↓ Whitmore et al., 2016 | |

| Flagellin | ↑ Hayashi et al., 2003 | ↓ Hayashi et al., 2003 | ↑ Hayashi et al., 2003 | ? | ? | No change/↓ Francois et al., 2005; Salamone et al., 2010 | ↑/↓ Hayashi et al., 2003 | |

| Others | ATP | ? | ↑ Ding et al., 2016 | ? | ↑ Aziz et al., 1997; Meshki et al., 2004 | ? | ? | ? |

| Substance P | ↑ Dianzani et al., 2003 | ↑ Marasco et al., 1981; Perianin et al., 1989 | ? | ↑ Marasco et al., 1981 | ? | ↓ Bockmann et al., 2001 | ↑ Perianin et al., 1989; Wozniak et al., 1989 | |

| CL097, CL075 | ? | ? | ? | ↑ Makni-Maalej et al., 2012 | ? | ? | ? | |

| Adhesion | – | – | ↑ Kasorn et al., 2009 | ↑ Xu and Hakansson, 2002 | ? | ↓ Mayadas and Cullere, 2005 | ↑ Steadman et al., 1996 | |

Table 1 shows the phenotypic changes induced by agents known to prime neutrophil respiratory burst activity. All the priming agents listed in this table are known inducers of enhanced NADPH oxidase activity. ↑refers to an increase in activity compared to unprimed neutrophils, ↓refers to a decrease in activity, and ? indicates an unknown effect of priming agent.

Phenotypic changes during priming

Respiratory burst activity

For decades, enhanced respiratory burst activity has defined a primed neutrophil. The respiratory burst generates ROS through conversion of molecular oxygen to superoxide by the multi-component NADPH oxidase complex. The oxidase is comprised of three membrane subunits (gp91phox/NOX2, p22phox, and Rap1A) and four cytosolic proteins (p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and Rac2). Spatial separation of the membrane and cytosolic components maintains enzymatic inactivity in resting neutrophils. Upon stimulation, the cytosolic components translocate to the membrane to form the catalytically active enzyme complex. Phosphorylation of cytosolic NADPH oxidase components is necessary for translocation of those components to the plasma membrane. One of the major targets of phosphorylation is the p47phox subunit. Phosphorylation of a number of serines (Ser303–Ser379) early in the activation process facilitates p47phox docking to membrane and cytosolic oxidase components, leading to assembly of the functional oxidase (El-Benna et al., 1994, 1996; Groemping et al., 2003).

Non-receptor tyrosine kinases and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) are signaling molecules that participate in priming respiratory burst activity by TNFα (El-Benna et al., 1996; McLeish et al., 1998; Forsberg et al., 2001; Dewas et al., 2003; Boussetta et al., 2010). Inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity blocks the activation of p38 MAPK by TNFα (McLeish et al., 1998), indicating that tyrosine kinases participate in priming by activating p38 MAPK. TNFα-mediated activation of the p38 MAPK pathway contributes to priming by enhancing plasma membrane translocation of the cytosolic components of the NADPH oxidase and by increasing expression of the plasma membrane oxidase components. Enhanced translocation of cytosolic components results from p38 MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of Ser345 on p47phox. Phosphorylation of Ser345 initiates a series of conformational changes in p47phox that result in hyperactivation of the NADPH oxidase. The initial event is binding of the prolyl isomerase Pin1 to the phospho-Ser345 site (Boussetta et al., 2010). This produces a conformational change in p47phox that exposes additional amino acids for phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC). Phosphorylation by PCK produces a second conformational change that promotes p47phox binding to p22phox. That interaction leads to translocation and assembly of all the cytosolic oxidase components with the membrane NADPH oxidase components. Pin1 is also involved in priming by GM-CSF and CL097, a TLR8 agonist (Makni-Maalej et al., 2012, 2015). Unlike TNFα, GM-CSF induces phosphorylation of Ser345 on p47phox through activation of ERK1/2, not p38 MAPK (Boussetta et al., 2010; Makni-Maalej et al., 2015). This observation indicates that multiple signal transduction pathways induce the same molecular events required for priming. Those redundant signal transduction pathways are unlikely to serve as effective therapeutic targets.

Over a decade ago, it was suggested that TNFα and LPS play a role in respiratory burst priming by influencing membrane trafficking (DeLeo et al., 1998; Ward et al., 2000). Direct confirmation was provided recently by selectively blocking exocytosis prior to priming through the use of cell-permeable, peptide inhibitors of SNARE protein interactions (Uriarte et al., 2011; McLeish et al., 2013). Those studies determined that exocytosis of secretory vesicles and gelatinase granules is required for priming by TNFα and platelet activating factor. Exocytosis could be contributing to priming by increasing plasma membrane expression of receptors, signaling molecules, and/or NADPH oxidase membrane components. The role of receptor and signaling molecule expression in priming was examined by measuring the activation of p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 in neutrophils primed during inhibition of exocytosis (Uriarte et al., 2011). The absence of granule exocytosis had no effect on activation of either MAPK, indicating that increased expression of receptors and signaling molecules does not contribute to priming (Uriarte et al., 2011). Inhibition of Pin1 activity had no effect on neutrophil granule exocytosis (McLeish et al., 2013). We interpret those studies to indicate that enhanced translocation of cytosolic oxidase components and increased expression of membrane oxidase components are independent events, both of which are required for priming.

A second membrane trafficking event that participates in priming respiratory burst activity is clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Moreland and colleagues reported that the NADPH oxidase assembles on endosomes, and the subsequent H2O2 production was required for neutrophil priming by endotoxin (Moreland et al., 2007; Volk et al., 2011; Lamb et al., 2012). We have confirmed those observations and determined that endocytosis is an upstream event in neutrophil granule exocytosis.

Neutrophil granule release

Neutrophil granules are divided into four classes based on granule density and contents (Borregaard and Cowland, 1997; Lominadze et al., 2005; Rørvig et al., 2013). Secretory vesicles are created by endocytosis, while gelatinase (tertiary), specific (secondary), and azurophilic (primary) granules are formed from the trans-Golgi network during neutrophil maturation (Borregaard, 2010). Granule subsets undergo an ordered release based on stimulus intensity, termed graded exocytosis (Sengelov et al., 1993, 1995). Secretory vesicles undergo exocytosis more easily and completely than gelatinase granules. Specific and azurophilic granules, which contain toxic anti-microbial components, undergo the most limited exocytosis. An in vivo study showed that neutrophils migrating into a skin blister created in normal human subjects release nearly 100% of their secretory vesicles, 40% of gelatinase granules, 20% of specific granules, and < 10% of azurophilic granules (Sengelov et al., 1995).

We recently reported that TNFα directly stimulated exocytosis of secretory vesicles and gelatinase granules (McLeish et al., 2017). Those results support previous studies showing that exocytosis of secretory vesicles and gelatinase granule is required for TNFα-induced priming (McLeish et al., 2013). Neither TNFα nor fMLF, alone, stimulated exocytosis of specific and azurophilic granules. However, TNFα primed the release of both granule subsets upon subsequent stimulation by fMLF (McLeish et al., 2017). The ability of TNFα to prime exocytosis of azurophilic granules was also reported by Potera et al. (2016). Thus, differential regulation of exocytosis of the four granule subsets by TNFα primes the two major neutrophil anti-microbial defense mechanisms for enhanced release of ROS and toxic granule contents, while protecting against cell injury from inappropriate release of those toxic products. On the other hand, Ramadass et al. showed that GM-CSF both stimulated and primed exocytosis of gelatinase, specific, and azurophilic granules in mouse neutrophils (Ramadass et al., 2017). The basis for differences between TNFα and GM-CSF could be due to disparate capabilities of priming agents or to species differences.

Proteins that control priming by regulating exocytosis have only recently been identified. As pharmacologic inhibition of p38 MAPK prevents TNF-α stimulated exocytosis (Mocsai et al., 1999; Uriarte et al., 2011; McLeish et al., 2013), we employed a phosphoproteomic analysis by mass spectrometry to identify proteins phosphorylated by the p38 MAPK pathway during TNFα stimulation (McLeish et al., 2017). Four of the proteins identified, Raf1, MARCKS, ABI1, and myosin VI, were previously shown to be involved in exocytosis in various cells. We confirmed that Raf1 participates in TNFα-stimulated exocytosis. Catz and colleagues used neutrophils from transgenic mice to identify Rab27a and its target, Munc13-4, as mediators of neutrophil exocytosis stimulated by GM-CSF (Ramadass et al., 2017). They showed that Rab27a, but not Munc13-4, was required for GM-CSF priming of exocytosis to subsequent stimulation by TLR agonists or formyl peptides. Thus, the mechanisms that control neutrophil exocytosis during priming offer potential targets for intervention in inflammatory processes in which neutrophil priming is involved.

Adhesion, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis

As shown in Figure 1, microbial invasion or tissue injury releases pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMPs) molecules that induce sentinel immune cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines. Those cytokines modify both endothelial cell and neutrophil adhesion molecule expression to facilitate the capture of circulating neutrophils and to mediate their migration into tissues. As shown in Table 1, all priming agents for which there are data directly activate neutrophil adhesion. However, differential regulation of adhesion molecule expression and activation by different priming agents may produce different rates of neutrophil adhesion and migration efficiency. For example, neutrophil exposure to TNFα increases plasma membrane expression of the β2 integrin receptor, CD11b/CD18, through exocytosis of secretory vesicles; decreases expression of the selectin receptor CD62-L through receptor shedding; and induces sustained activation of CD11b/CD18 through inside-out signaling (Condliffe et al., 1996; Swain et al., 2002). On the other hand, PAF increases surface expression of the CD11b/CD18, has no effect on selectin expression, and induces only transient activation of CD11b/CD18 (Berends et al., 1997; Khreiss et al., 2004). The in vivo significance of those differences in adhesion molecule expression and activation remains to be determined.

With the exception of IFNγ, neutrophil chemotaxis is enhanced by all priming agents for which there are data (Table 1). In addition to increased expression of adhesion molecules and receptors resulting from exocytosis, priming agents increase actin reorganization (Borgquist et al., 2002), and enhances chemokinesis and chemotaxis (Montecucco et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2015). For example, treatment of neutrophils with PAF, IL-8, or TNFα, alone, induces chemokinesis, while subsequent exposure to an fMLF gradient leads to enhanced neutrophil chemotaxis (Drost and MacNee, 2002). Additionally, TNFα-primed neutrophils gain the ability to migrate toward the chemokine CCL3, which is found in inflammatory sites, but is normally not a neutrophil chemo attractant (Montecucco et al., 2008).

Neutrophil adhesion through both the engagement of neutrophil β2 integrin receptors with endothelial cell adhesion molecules and the binding of neutrophil receptors with extracellular matrix proteins primes respiratory burst activity (Stanislawski et al., 1990; Dapino et al., 1993; Liles et al., 1995). Neutrophil adhesion induces other priming phenotypes, including exocytosis of secretory vesicles and gelatinase granules and a reduced rate of apoptosis (Hu et al., 2004; McGettrick et al., 2006; Paulsson et al., 2010). Thus, transmigration of neutrophils into the extravascular space can be expected to directly induce some of the features of priming.

When neutrophils arrive at the site of infection, they demonstrate increased phagocytosis due to upregulation in the number and affinity of phagocytic receptors (Condliffe et al., 1998; Rainard et al., 2000; Le et al., 2012). Table 1 lists the effects of specific priming agents on phagocytosis. Exposure of bovine neutrophils to the combination of two priming agents, TNFα and C5a each at suboptimal concentrations, enhanced both the rate of phagocytosis and the killing capacity toward serum opsonized Staphylococcus aureus (Rainard et al., 2000); and incubation of human neutrophils with insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) results in a significant increase in phagocytosis of both IgG-opsonized S. aureus and serum-opsonized Candida albicans (Bjerknes and Aarskog, 1995). Increased neutrophil phagocytosis is dependent on the concentration and incubation time with IGF-1, and is due to increased complement receptor (CR) 1 and CR3 expression. IGF-1 enhances Fcγ receptor-dependent phagocytosis through increased receptor function and activation, while Fcγ receptor expression is unchanged (Bjerknes and Aarskog, 1995). Thus, neutrophil exposure to the complex milieu of priming agents in vivo is likely to produce additive or synergistic changes in functional responses. Defining neutrophil responses in that complex environment will require application of systems biology methodologies.

Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation

Since their first description in 2004, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) have received intense investigation. Although, the majority of studies have measured NET formation by resting neutrophils, neutrophils from normal subjects primed by TNFα in vitro demonstrated robust NET formation following a 3 h exposure to anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (Kessenbrock et al., 2009). Enhanced NET formation in primed neutrophils is supported by other in vitro studies using GM-CSF and TNFα (Yousefi et al., 2009; Hazeldine et al., 2014). The effect of priming agents on NET formation is listed in Table 1.

Despite their original classification as the third bacterial killing mechanism, current opinion leans toward NETs being important contributors to autoimmunity and tissue injury, rather than antibacterial activity (Sorensen and Borregaard, 2016). In vivo, enhanced NET formation following a systemic change in levels of inflammatory cytokines has been described in cancers, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes (Chechlinska et al., 2010; Naegele et al., 2012; Fadini et al., 2016). Using a chronic myelogenous leukemia mouse model, Demers and colleagues reported that non-malignant neutrophils showed enhanced NET formation, leading to increased coagulation and thrombosis (Demers et al., 2012). Priming of NET formation was reproduced in control mice by sequential administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and LPS. The authors suggested that priming NET formation by systemic cytokines plays a role in cancer progression. While the current literature indicates that enhanced NET formation is a component of neutrophil priming, the functional consequences of that response remain to be determined.

Secretion of lipid and cytokine mediators

As summarized in Table 1, primed neutrophils demonstrate increased metabolic and transcriptional activity that leads to synthesis of a number of pro- and anti-inflammatory chemokines, cytokines, and lipids. Although, the ability of neutrophils to synthesize those products is less than that of macrophages, the large number of neutrophils present at sites of inflammation is postulated to influence both innate and adaptive immune responses through release of those inflammatory mediators.

Pro-inflammatory lipid mediators like leukotriene B4 (LTB4) can be produced de novo by the arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) pathway in neutrophils and play important roles in aggregation, degranulation, and chemotaxis (O'Flaherty et al., 1979; Flamand et al., 2000). The production of these lipid mediators occurs through a series of biochemical events that primarily take place in the perinuclear region where membrane phospholipids are first converted to arachidonic acid (AA) by the calcium–dependent enzyme phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Luo et al., 2003; Leslie, 2004). The newly synthesized AA is then converted by 5-LO into leukotriene A4(LTA4), which is the immediate precursor of LTB4. Neutrophil production of LTB4 is responsible for a second wave of neutrophil recruitment during inflammation, a process termed “swarming” (Lammermann et al., 2013). This is one of many examples of amplification loops initiated by neutrophils (Nemeth and Mocsai, 2016).

Direct activation of neutrophils by fMLF does not lead to the detectable release of leukotrienes, but priming with GM-CSF, LPS, or TNFα followed by fMLF stimulation significantly increases LTB4 release (see Table 1; DiPersio et al., 1988a; Schatz-Munding and Ullrich, 1992; Palmantier et al., 1994; Seeds et al., 1998; Zarini et al., 2006). All three of these priming agents activate PLA2 and increase AA release without increasing intracellular Ca2+ (DiPersio et al., 1988b; Schatz-Munding and Ullrich, 1992; Zarini et al., 2006). The elevation in available AA substrate leads to prolonged activation of 5-LO and enhanced production of downstream lipid mediators (Surette et al., 1993, 1998; Doerfler et al., 1994). Once produced, LTB4 can exert autocrine effects. It primes neutrophil responses to toll-like-receptor (TLR) agonists, resulting in enhanced cytokine (IL-8, TNFα) secretion (Gaudreault et al., 2012). TLR9 mRNA levels are upregulated upon priming with LTB4, but there is no increase in surface expression of TLR2, TLR4, or the co-receptors TLR1 and TLR6 following LTB4 exposure (Gaudreault and Gosselin, 2009; Gaudreault et al., 2012). Instead, neutrophil LTB4-induced hyper-responsiveness is mediated by the potentiation of TLR-induced intracellular signaling. TAK1 and p38 MAPK, which are essential in TLR-activated cytokine release, are phosphorylated and activated following LTB4 interaction with its seven transmembrane-spanning receptor.

PAF is another lipid inflammatory mediator whose production is primed in neutrophils. Both LPS and GM-CSF enhance PAF synthesis in response to activating stimuli (Aglietta et al., 1990; Surette et al., 1998). After priming with GM-CSF, there is increased enzymatic activity of acetyl transferase, the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of PAF (Aglietta et al., 1990). However, the pattern of PAF synthesis after LPS priming is attributed to a biphasic, autocrine response. The early peak in production is due to the direct effect of LPS, while the delayed peak is a result of LPS-induced IL-8 and TNF-α release (Bussolati et al., 1997).

Neutrophils modulate inflammation through the release of stored or newly produced cytokines and chemokines (Cassatella, 1999). Exposure of neutrophils to priming agents leads to an increase in synthesis and release of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, CXCL1, CXCL2, CCL3 (MIP-1α), CCL4 (MIP-1β) (Roberge et al., 1998; Zallen et al., 1999; Jablonska et al., 2002b; Choi et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2013). The inducible synthesis of the majority of cytokines and chemokines results from increased gene transcription (Marucha et al., 1991; Cassatella et al., 1995; Cassatella, 1996, 1999; Fernandez et al., 1996). TNFα, LPS, and GM-CSF increase intra-nuclear translocation of NF-κB, C/EBP, or CREB transcription factors (Cloutier et al., 2007, 2009; Mayer et al., 2013). LPS induces a biphasic production of IL-8. For the first few hours (2–6 h) of exposure, LPS directly stimulates IL-8 synthesis, but the second wave of sustained IL-8 release (up to 18 h) is due to the endogenous release of TNFα and IL-1β (Cassatella et al., 1993).

Release of neutrophil extracellular vesicles

Cell-derived vesicles represent a mechanism for cell-cell communication. Exosomes are 50–100 nm vesicles released from multivesicular bodies that are involved in antigen presentation and cell-to-cell transfer of receptors or RNA (Gyorgy et al., 2011). Larger vesicles, called microvesicles or microparticles express tissue factors on their surface that are capable of initiating coagulation. Neutrophils undergoing apoptosis or stimulated by chemotactic agents, opsonic receptors, or TNFα release microparticles. However, the microparticles have varying compositions and functional capabilities, depending on the stimulus (Dalli et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2014; Lorincz et al., 2015). Microparticles obtained from neutrophils stimulated by chemotactic agents or phorbol esters activate cytokine (IL-6) secretion from endothelial cells and platelets (Mesri and Altieri, 1998; Pluskota et al., 2008). Chemotactic peptide-induced microparticles increase secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine transforming growth factor-β and interfere with the maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells (Gasser and Schifferli, 2004; Eken et al., 2010). Auto-antibody-stimulated release of neutrophil microparticles was suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of vasculitis (Hong et al., 2012). Additional activities ascribed to neutrophil microparticles include suppression of bacterial growth, activation of endothelial cell cytokine production, altered cytokine profile of natural killer cells and monocytes, and increased coagulation (Mesri and Altieri, 1998; Timar et al., 2013a,b; Pliyev et al., 2014). An understanding of the stimuli and signal transduction pathways leading to formation and release of neutrophil extracellular vesicles and their roles in inflammation remains to be developed.

Rate of apoptosis

Table 1 indicates that neutrophil apoptosis is variably affected in response to priming agents. While LPS, GM-CSF, IL-8, and LTB4 have been found to extend neutrophil lifespan in vitro, PAF, fMLF, and IL-6 show no effect, and TNFα shows a biphasic response where it promotes apoptosis during the first 8 h of exposure, followed by a delayed rate of apoptosis at later times (Klein et al., 2000, 2001; Cowburn et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2014). Primed neutrophils from patients with multiple sclerosis, ANCA-associated vasculitis, and liver cirrhosis show increased apoptosis (Harper et al., 2001; Klimchenko et al., 2011; Naegele et al., 2012), while neutrophils from patients at risk of multiple-organ failure and individuals presenting with septic peritonitis, severe trauma, or septic trauma show a decrease in apoptosis (Ertel et al., 1998; Biffl et al., 1999, 2001; Nolan et al., 2000; Feterowski et al., 2001). Those conflicting reports of the effect of inflammation on apoptosis in vivo are likely due to different priming agents involved in different diseases, different responses during the time course of disease, and differences in the neutrophil micro-environment, such as cell density (Hannah et al., 1998).

The mechanisms underlying the effects of priming on neutrophil apoptosis have been partially characterized. As for TNFα, increased rates of apoptosis during the first hours of exposure are associated with activation of caspase cascades (Murray et al., 1997). TNFα also induces an early, PI-3K-mediated increase in mRNA levels for Bad, a member of the BCL2 family that regulates apoptosis. On the other hand, decreased neutrophil apoptosis observed at later time points is associated with a reduction in Bad mRNA levels (Cowburn et al., 2002). GM-CSF, IL-8, LPS, and LTB4 decrease the rate of neutrophil apoptosis through activation of ERK1/2 and/or PI-3K/Akt pathways (Klein et al., 2000, 2001). Incubation of neutrophils with fMLF had no effect on the rate of apoptosis, despite activation of both ERK1/2 and Akt (Klein et al., 2001). GM-CSF was also shown to decrease mRNA levels of Bad, while increasing its phosphorylation (Cowburn et al., 2002). A RNA seq study comparing TNFα and GM-CSF priming pathways showed that out of 580 genes differentially expressed between both agents, 58 were implicated in the delay of apoptosis. Thus, each priming agent produced a distinct profile of pro- and anti-apoptotic genes (Wright et al., 2013). The varying rates of neutrophil apoptosis may serve different functions in the inflammatory response. For example, a reduced rate of apoptosis early in the recruitment of neutrophils results in a brisk accumulation of primed neutrophils. On the other hand, an enhanced rate of apoptosis at later time points promotes resolution through loss of active neutrophils and a change in phenotype of monocytes engulfing apoptotic neutrophils.

Conclusions

The altered neutrophil functions described in this review indicate that priming is a complex phenomenon. Priming involves enhanced respiratory burst, exocytosis, NET formation, and chemotaxis in response to a second stimulus. Priming, however, is not just preparation for an enhanced response to a second stimulus. Priming involves activation of a subset of neutrophil responses, including adhesion, transcription, cytoskeletal reorganization, translocation and expression of receptors, and other molecules, the rate of constitutive apoptosis, metabolic activity, and phagocytosis. The altered neutrophil responses associated with priming primarily result in amplification of the inflammatory response. Although, recruitment of primed neutrophils improves the clearance of invading microbes, the risk of directly injuring surrounding cells is increased. Moreover, the increased synthesis and release of cytokines and lipids by primed neutrophils, combined with increased neutrophil recruitment and life-span, result in an increased local concentration of pro-inflammatory agents. Those agents recruit and prime additional neutrophils, leading to an enhanced innate immune response. Neutrophil-dependent recruitment and activation of dendritic cells and various lymphocyte subsets also enhances the adaptive immune response.

We propose that the current definition of priming, which focuses on a transition state to an enhanced responsiveness to a second stimulus, is too restrictive. Neutrophil priming also results in activation of a subset of neutrophil responses that regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Additionally, neutrophil responses to priming agents vary depending on concentration of the priming agent, time of exposure, and the specific priming agent (Potera et al., 2016; McLeish et al., 2017). It seems likely that neutrophils are exposed to graded concentrations of priming agents as they progress through the multistep process of recruitment, as occurs with chemoattactants. This leads to the hypothesis that, similar to graded granule exocytosis, priming occurs in a graded manner during a neutrophil's journey to the site of inflammation. This graded response allows neutrophils to acquire functions in an ordered manner, as required during recruitment. A fully primed neutrophil that releases a maximal amount of toxic chemicals would occur when an optimal concentration of a priming stimulus is encountered. Combining knowledge of the molecular events with an understanding of priming at a systems level will identify therapeutic targets for neutrophil functions that exacerbate individual diseases, while preserving the functions that participation in host defense.

Author contributions

Contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript IM, KM, SU; designed and illustrated the figure IM.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

- Aas V., Lappegard K. T., Siebke E. M., Benestad H. B. (1996). Modulation by interferons of human neutrophilic granulocyte migration. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 16, 929–935. 10.1089/jir.1996.16.929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acorci M. J., Dias-Melicio L. A., Golim M. A., Bordon-Graciani A. P., Peracoli M. T., Soares A. M. (2009). Inhibition of human neutrophil apoptosis by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: role of interleukin-8. Scand. J. Immunol. 69, 73–79. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso P. V., Janka-Junttila M., Lee Y. J., McCann C. P., Oliver C. M., Aamer K. A., et al. (2012). LTB4 is a signal-relay molecule during neutrophil chemotaxis. Dev. Cell 22, 1079–1091. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aglietta M., Monzeglio C., Apra F., Mossetti C., Stern A. C., Giribaldi G., et al. (1990). In vivo priming of human normal neutrophils by granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor: effect on the production of platelet activating factor. Br. J. Haematol. 75, 333–339. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1990.tb04345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson E., Onnheim K., Forsman H. (2013). The subcellular localization of the receptor for platelet-activating factor in neutrophils affects signaling and activation characteristics. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013:456407. 10.1155/2013/456407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aomatsu K., Kato T., Fujita H., Hato F., Oshitani N., Kamata N., et al. (2008). Toll-like receptor agonists stimulate human neutrophil migration via activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Immunology 123, 171–180. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino E. N., Neves A. C., Santos K. C., Uribe C. E., Souza P. E., Correa J. R., et al. (2016). Proteomic analysis of neutrophil priming by PAF. Protein Pept. Lett. 23, 142–151. 10.2174/0929866523666151202210604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz K. A., Cawley J. C., Treweeke A. T., Zuzel M. (1997). Sequential potentiation and inhibition of PMN reactivity by maximally stimulated platelets. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61, 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M., Clark-Lewis I. (1992). Interleukin-8, a chemotactic and inflammatory cytokine. FEBS Lett. 307, 97–101. 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80909-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass D. A., Olbrantz P., Szejda P., Seeds M. C., McCall C. E. (1986). Subpopulations of neutrophils with increased oxidative product formation in blood of patients with infection. J. Immunol. 136, 860–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauldry S. A., McCall C. E., Cousart S. L., Bass D. A. (1991). Tumor necrosis factor-alpha priming of phospholipase A2 activation in human neutrophils. An alternative mechanism of priming. J. Immunol. 146, 1277–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berends C., Dijkhuizen B., de Monchy J. G., Dubois A. E., Gerritsen J., Kauffman H. F. (1997). Inhibition of PAF-induced expression of CD11b and shedding of L-selectin on human neutrophils and eosinophils by the type IV selective PDE inhibitor, rolipram. Eur. Respir. J. 10, 1000–1007. 10.1183/09031936.97.10051000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffl W. L., Moore E. E., Zallen G., Johnson J. L., Gabriel J., Offner P. J., et al. (1999). Neutrophils are primed for cytotoxicity and resist apoptosis in injured patients at risk for multiple organ failure. Surgery 126, 198–202. 10.1016/S0039-6060(99)70155-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffl W. L., West K. E., Moore E. E., Gonzalez R. J., Carnaggio R., Offner P. J., et al. (2001). Neutrophil apoptosis is delayed by trauma patients' plasma via a mechanism involving proinflammatory phospholipids and protein kinase C. Surg. Infect. 2, 289–293; discussion: 294–285. 10.1089/10962960152813322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerknes R., Aarskog D. (1995). Priming of human polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocytes by insulin-like growth factor I: increased phagocytic capacity, complement receptor expression, degranulation, and oxidative burst. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 80, 1948–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockmann S., Seep J., Jonas L. (2001). Delay of neutrophil apoptosis by the neuropeptide substance P: involvement of caspase cascade. Peptides 22, 661–670. 10.1016/S0196-9781(01)00376-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgquist J. D., Quinn M. T., Swain S. D. (2002). Adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins modulates bovine neutrophil responses to inflammatory mediators. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71, 764–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borregaard N. (2010). Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity 33, 657–670. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borregaard N., Cowland J. B. (1997). Granules of the human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocyte. Blood 89, 3503–3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaouina M., Blouin E., Halbwachs-Mecarelli L., Lesavre P., Rieu P. (2004). TNF-induced beta2 integrin activation involves Src kinases and a redox-regulated activation of p38 MAPK. J. Immunol. 173, 1313–1320. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussetta T., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., Hayem G., Ciappelloni S., Raad H., Arabi Derkawi R., et al. (2010). The prolyl isomerase Pin1 acts as a novel molecular switch for TNF-alpha-induced priming of the NADPH oxidase in human neutrophils. Blood 116, 5795–5802. 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandolini L., Sergi R., Caselli G., Boraschi D., Locati M., Sozzani S., et al. (1997). Interleukin-1 beta primes interleukin-8-stimulated chemotaxis and elastase release in human neutrophils via its type I receptor. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 8, 173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning D. D., Pan Z. K., Prossnitz E. R., Ye R. D. (1997). Cell type- and developmental stage-specific activation of NF-kappaB by fMet-Leu-Phe in myeloid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7995–8001. 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussolati B., Mariano F., Montrucchio G., Piccoli G., Camussi G. (1997). Modulatory effect of interleukin-10 on the production of platelet-activating factor and superoxide anions by human leucocytes. Immunology 90, 440–447. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1997.00440.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella M. A. (1995). The production of cytokines by polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Immunol. Today 16, 21–26. 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80066-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella M. A. (1996). Interferon-gamma inhibits the lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha gene transcription in human neutrophils. Immunol. Lett. 49, 79–82. 10.1016/0165-2478(95)02484-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella M. A. (1999). Neutrophil-derived proteins: selling cytokines by the pound. Adv. Immunol. 73, 369–509. 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60791-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella M. A., Cappelli R., Della Bianca V., Grzeskowiak M., Dusi S., Berton G. (1988). Interferon-gamma activates human neutrophil oxygen metabolism and exocytosis. Immunology 63, 499–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella M. A., Gasperini S., Calzetti F., McDonald P. P., Trinchieri G. (1995). Lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-8 gene expression in human granulocytes: transcriptional inhibition by interferon-gamma. Biochem. J. 310(Pt 3), 751–755. 10.1042/bj3100751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella M. A., Meda L., Bonora S., Ceska M., Constantin G. (1993). Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits the release of proinflammatory cytokines from human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Evidence for an autocrine role of tumor necrosis factor and IL-1 beta in mediating the production of IL-8 triggered by lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 178, 2207–2211. 10.1084/jem.178.6.2207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chechlinska M., Kowalewska M., Nowak R. (2010). Systemic inflammation as a confounding factor in cancer biomarker discovery and validation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 2–3. 10.1038/nrc2782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S. S., Lai J. J., Lukacs N. W., Kunkel S. L. (2001). Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor up-regulates CCR1 in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 166, 1178–1184. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. C., Jung J. W., Kwak H. W., Song J. H., Jeon E. J., Shin J. W., et al. (2008). Granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) augments acute lung injury via its neutrophil priming effects. J. Korean Med. Sci. 23, 288–295. 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier A., Ear T., Blais-Charron E., Dubois C. M., McDonald P. P. (2007). Differential involvement of NF-kappaB and MAP kinase pathways in the generation of inflammatory cytokines by human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81, 567–577. 10.1189/jlb.0806536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier A., Guindi C., Larivee P., Dubois C. M., Amrani A., McDonald P. P. (2009). Inflammatory cytokine production by human neutrophils involves C/EBP transcription factors. J. Immunol. 182, 563–571. 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condliffe A. M., Chilvers E. R., Haslett C., Dransfield I. (1996). Priming differentially regulates neutrophil adhesion molecule expression/function. Immunology 89, 105–111. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-711.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condliffe A. M., Kitchen E., Chilvers E. R. (1998). Neutrophil priming: pathophysiological consequences and underlying mechanisms. Clin. Sci. 94, 461–471. 10.1042/cs0940461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowburn A. S., Cadwallader K. A., Reed B. J., Farahi N., Chilvers E. R. (2002). Role of PI3-kinase-dependent Bad phosphorylation and altered transcription in cytokine-mediated neutrophil survival. Blood 100, 2607–2616. 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalli J., Montero-Melendez T., Norling L. V., Yin X., Hinds C., Haskard D., et al. (2013). Heterogeneity in neutrophil microparticles reveals distinct proteome and functional properties. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 2205–2219. 10.1074/mcp.M113.028589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapino P., Dallegri F., Ottonello L., Sacchetti C. (1993). Induction of neutrophil respiratory burst by tumour necrosis factor-alpha; priming effect of solid-phase fibronectin and intervention of CD11b-CD18 integrins. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 94, 533–538. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb08230.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeo F. R., Renee J., McCormick S., Nakamura M., Apicella M., Weiss J. P., et al. (1998). Neutrophils exposed to bacterial lipopolysaccharide upregulate NADPH oxidase assembly. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 455–463. 10.1172/JCI949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Bianca V., Dusi S., Nadalini K. A., Donini M., Rossi F. (1995). Role of 55- and 75-kDa TNF receptors in the potentiation of Fc-mediated phagocytosis in human neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 214, 44–50. 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers M., Krause D. S., Schatzberg D., Martinod K., Voorhees J. R., Fuchs T. A., et al. (2012). Cancers predispose neutrophils to release extracellular DNA traps that contribute to cancer-associated thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 13076–13081. 10.1073/pnas.1200419109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmers P. A., Lo S. K., Olsen-Egbert E., Walz A., Baggiolini M., Cohn Z. A. (1990). Neutrophil-activating protein 1/interleukin 8 stimulates the binding activity of the leukocyte adhesion receptor CD11b/CD18 on human neutrophils. J. Exp. Med. 171, 1155–1162. 10.1084/jem.171.4.1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewas C., Dang P. M., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., El-Benna J. (2003). TNF-alpha induces a. phosphorylation of p47(phox) in human neutrophils: partial phosphorylation of p47phox is a common event of priming of human neutrophils by TNF-alpha and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Immunol. 171, 4392–4398. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dianzani C., Collino M., Lombardi G., Garbarino G., Fantozzi R. (2003). Substance P increases neutrophil adhesion to human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 139, 1103–1110. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q., Quah S. Y., Tan K. S. (2016). Secreted adenosine triphosphate from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans triggers chemokine response. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 31, 423–434. 10.1111/omi.12143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio J. F., Billing P., Williams R., Gasson J. C. (1988a). Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and other cytokines prime human neutrophils for enhanced arachidonic acid release and leukotriene B4 synthesis. J. Immunol. 140, 4315–4322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio J. F., Naccache P. H., Borgeat P., Gasson J. C., Nguyen M. H., McColl S. R. (1988b). Characterization of the priming effects of human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on human neutrophil leukotriene synthesis. Prostaglandins 36, 673–691. 10.1016/0090-6980(88)90013-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiScipio R. G., Schraufstatter I. U., Sikora L., Zuraw B. L., Sriramarao P. (2006). C5a mediates secretion and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 from human eosinophils and neutrophils. Int. Immunopharmacol. 6, 1109–1118. 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerfler M. E., Weiss J., Clark J. D., Elsbach P. (1994). Bacterial lipopolysaccharide primes human neutrophils for enhanced release of arachidonic acid and causes phosphorylation of an 85-kD cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 1583–1591. 10.1172/JCI117138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drost E. M., MacNee W. (2002). Potential role of IL-8, platelet-activating factor and TNF-alpha in the sequestration of neutrophils in the lung: effects on neutrophil deformability, adhesion receptor expression, and chemotaxis. Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eken C., Martin P. J., Sadallah S., Treves S., Schaller M., Schifferli J. A. (2010). Ectosomes released by polymorphonuclear neutrophils induce a MerTK-dependent anti-inflammatory pathway in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39914–39921. 10.1074/jbc.M110.126748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Azreq M. A., Garceau V., Bourgoin S. G. (2011). Cytohesin-1 regulates fMLF-mediated activation and functions of the beta2 integrin Mac-1 in human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 89, 823–836. 10.1189/jlb.0410222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Benna J., Dang P. M., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A. (2008). Priming of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation: role of p47phox phosphorylation and NOX2 mobilization to the plasma membrane. Semin. Immunopathol. 30, 279–289. 10.1007/s00281-008-0118-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Benna J., Faust L. P., Babior B. M. (1994). The phosphorylation of the respiratory burst oxidase component p47phox during neutrophil activation. Phosphorylation of sites recognized by protein kinase C and by proline-directed kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23431–23436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Benna J., Han J., Park J. W., Schmid E., Ulevitch R. J., Babior B. M. (1996). Activation of p38 in stimulated human neutrophils: phosphorylation of the oxidase component p47phox by p38 and ERK but not by JNK. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 334, 395–400. 10.1006/abbi.1996.0470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Benna J., Hurtado-Nedelec M., Marzaioli V., Marie J. C., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., Dang P. M. (2016). Priming of the neutrophil respiratory burst: role in host defense and inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 273, 180–193. 10.1111/imr.12447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel W., Keel M., Infanger M., Ungethum U., Steckholzer U., Trentz O. (1998). Circulating mediators in serum of injured patients with septic complications inhibit neutrophil apoptosis through up-regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Trauma 44, 767–775; discussion: 775–766. 10.1097/00005373-199805000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eun J. C., Moore E. E., Banerjee A., Kelher M. R., Khan S. Y., Elzi D. J., et al. (2011). Leukotriene b4 and its metabolites prime the neutrophil oxidase and induce proinflammatory activation of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Shock 35, 240–244. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181faceb3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadini G. P., Menegazzo L., Rigato M., Scattolini V., Poncina N., Bruttocao A., et al. (2016). NETosis delays diabetic wound healing in mice and humans. Diabetes 65, 1061–1071. 10.2337/db15-0863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faldt J., Dahlgren C., Ridell M., Karlsson A. (2001). Priming of human neutrophils by mycobacterial lipoarabinomannans: role of granule mobilisation. Microbes Infect. 3, 1101–1109. 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01470-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Malik A. B. (2003). Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) signaling augments chemokine-induced neutrophil migration by modulating cell surface expression of chemokine receptors. Nat. Med. 9, 315–321. 10.1038/nm832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M. C., Walters J., Marucha P. (1996). Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of GM-CSF-induced IL-1 beta gene expression in PMN. J. Leukoc. Biol. 59, 598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feterowski C., Weighardt H., Emmanuilidis K., Hartung T., Holzmann B. (2001). Immune protection against septic peritonitis in endotoxin-primed mice is related to reduced neutrophil apoptosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 1268–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietta A., Francioli C., Gialdroni Grassi G. (2000). Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan affects human polymorphonuclear and mononuclear phagocyte functions differently. Haematologica 85, 11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterbusch M., Voisin M. B., Beyrau M., Williams T. J., Nourshargh S. (2014). Neutrophils recruited by chemoattractants in vivo induce microvascular plasma protein leakage through secretion of TNF. J. Exp. Med. 211, 1307–1314. 10.1084/jem.20132413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fittschen C., Sandhaus R. A., Worthen G. S., Henson P. M. (1988). Bacterial lipopolysaccharide enhances chemoattractant-induced elastase secretion by human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 43, 547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamand N., Boudreault S., Picard S., Austin M., Surette M. E., Plante H., et al. (2000). Adenosine, a potent natural suppressor of arachidonic acid release and leukotriene biosynthesis in human neutrophils. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161(2 Pt 2), S88–S94. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_1.ltta-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg M., Löfgren R., Zheng L., Stendahl O. (2001). Tumour necrosis factor-alpha potentiates CR3-induced respiratory burst by activating p38 MAP kinase in human neutrophils. Immunology 103, 465–472. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01270.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois S., El Benna J., Dang P. M., Pedruzzi E., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., Elbim C. (2005). Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by TLR agonists in whole blood: involvement of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and NF-kappaB signaling pathways, leading to increased levels of Mcl-1, A1, and phosphorylated Bad. J. Immunol. 174, 3633–3642. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser O., Schifferli J. A. (2004). Activated polymorphonuclear neutrophils disseminate anti-inflammatory microparticles by ectocytosis. Blood 104, 2543–2548. 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault E., Gosselin J. (2009). Leukotriene B4 potentiates CpG signaling for enhanced cytokine secretion by human leukocytes. J. Immunol. 183, 2650–2658. 10.4049/jimmunol.0804135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault E., Paquet-Bouchard C., Fiola S., Le Bel M., Lacerte P., Shio M. T., et al. (2012). TAK1 contributes to the enhanced responsiveness of LTB(4)-treated neutrophils to Toll-like receptor ligands. Int. Immunol. 24, 693–704. 10.1093/intimm/dxs074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groemping Y., Lapouge K., Smerdon S. J., Rittinger K. (2003). Molecular basis of phosphorylation-induced activation of the NADPH oxidase. Cell 113, 343–355. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00314-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorgy B., Szabo T. G., Pasztoi M., Pal Z., Misjak P., Aradi B., et al. (2011). Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2667–2688. 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpert M. M., Thomas K. A., King R. G., Justement L. B. (2011). TLT2 potentiates neutrophil antibacterial activity and chemotaxis in response to G protein-coupled receptor-mediated signaling. J. Immunol. 187, 2346–2355. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah S., Nadra I., Dransfield I., Pryde J. G., Rossi A. G., Haslett C. (1998). Constitutive neutrophil apoptosis in culture is modulated by cell density independently of beta2 integrin-mediated adhesion. FEBS Lett. 421, 141–146. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01551-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper L., Cockwell P., Adu D., Savage C. O. (2001). Neutrophil priming and apoptosis in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis. Kidney Int. 59, 1729–1738. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590051729.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F., Means T. K., Luster A. D. (2003). Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood 102, 2660–2669. 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazeldine J., Harris P., Chapple I. L., Grant M., Greenwood H., Livesey A., et al. (2014). Impaired neutrophil extracellular trap formation: a novel defect in the innate immune system of aged individuals. Aging Cell 13, 690–698. 10.1111/acel.12222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Eleftheriou D., Hussain A. A., Price-Kuehne F. E., Savage C. O., Jayne D., et al. (2012). Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies stimulate release of neutrophil microparticles. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 49–62. 10.1681/ASN.2011030298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M., Miller E. J., Lin X., Simms H. H. (2004). Transmigration across a lung epithelial monolayer delays apoptosis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Surgery 135, 87–98. 10.1016/S0039-6060(03)00347-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys J. M., Hughes V., Edwards S. W. (1989). Stimulation of protein synthesis in human neutrophils by gamma-interferon. Biochem. Pharmacol. 38, 1241–1246. 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90329-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonska E., Izycka A., Wawrusiewicz N. (2002a). Effect of IL-18 on IL-1beta and sIL-1RII production by human neutrophils. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 50, 139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonska E., Kiluk M., Markiewicz W., Jablonski J. (2002b). Priming effects of GM-CSF, IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha on human neutrophil inflammatory cytokine production. Melanoma Res. 12, 123–128. 10.1097/00008390-200204000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonska E., Piotrowski L., Kiluk M., Jablonski J., Grabowska Z., Markiewicz W. (2001). Effect of IL-15 on the secretion of IL-1beta, IL-1Ra and sIL-1RII by PMN from cancer patients. Cytokine 16, 173–177. 10.1006/cyto.2001.0931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagels M. A., Daffern P. J., Hugli T. E. (2000). C3a and C5a enhance granulocyte adhesion to endothelial and epithelial cell monolayers: epithelial and endothelial priming is required for C3a-induced eosinophil adhesion. Immunopharmacology 46, 209–222. 10.1016/S0162-3109(99)00178-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. L., III., Kuethe J. W., Caldwell C. C. (2014). Neutrophil derived microvesicles: emerging role of a key mediator to the immune response. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 14, 210–217. 10.2174/1871530314666140722083717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S. (2002). Amplification of extracellular nucleotide-induced leukocyte(s) degranulation by contingent autocrine and paracrine mode of leukotriene-mediated chemokine receptor activation. Med. Hypotheses 59, 261–265. 10.1016/S0306-9877(02)00213-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannengiesser C., Gerard B., El Benna J., Henri D., Kroviarski Y., Chollet-Martin S., et al. (2008). Molecular epidemiology of chronic granulomatous disease in a series of 80 kindreds: identification of 31 novel mutations. Hum. Mutat. 29, E132–E149. 10.1002/humu.20820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasorn A., Alcaide P., Jia Y., Subramanian K. K., Sarraj B., Li Y., et al. (2009). Focal adhesion kinase regulates pathogen-killing capability and life span of neutrophils via mediating both adhesion-dependent and -independent cellular signals. J. Immunol. 183, 1032–1043. 10.4049/jimmunol.0802984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessenbrock K., Krumbholz M., Schonermarck U., Back W., Gross W. L., Werb Z., et al. (2009). Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat. Med. 15, 623–625. 10.1038/nm.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khreiss T., Jozsef L., Chan J. S., Filep J. G. (2004). Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase couples platelet-activating factor-induced adhesion and delayed apoptosis of human neutrophils. Cell. Signal. 16, 801–810. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff S. J., Olszowski S., Van Voorhis W. C., Ledbetter J. A., Waltersdorph A. M., Schlechte K. G. (1992). Effects of gamma-interferon on human neutrophils: protection from deterioration on storage. Blood 80, 225–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J. B., Buridi A., Coxon P. Y., Rane M. J., Manning T., Kettritz R., et al. (2001). Role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase in chemoattractant and LPS delay of constitutive neutrophil apoptosis. Cell. Signal. 13, 335–343. 10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00151-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J. B., Rane M. J., Scherzer J. A., Coxon P. Y., Kettritz R., Mathiesen J. M., et al. (2000). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor delays neutrophil constitutive apoptosis through phosphoinositide 3-kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways. J. Immunol. 164, 4286–4291. 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kletter Y., Bleiberg I., Golde D. W., Fabian I. (1989). Antibody to Mol abrogates the increase in neutrophil phagocytosis and degranulation induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Eur. J. Haematol. 43, 389–396. 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1989.tb00325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimchenko O., Di Stefano A., Geoerger B., Hamidi S., Opolon P., Robert T., et al. (2011). Monocytic cells derived from human embryonic stem cells and fetal liver share common differentiation pathways and homeostatic functions. Blood 117, 3065–3075. 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowanko I. C., Ferrante A., Harvey D. P., Carman K. L. (1991). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor augments neutrophil killing of Torulopsis glabrata and stimulates neutrophil respiratory burst and degranulation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 83, 225–230. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05619.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S., Woollard K. J., Thomas S., Oxley D., Jackson S. P. (2007). Conversion of platelets from a proaggregatory to a proinflammatory adhesive phenotype: role of PAF in spatially regulating neutrophil adhesion and spreading. Blood 110, 1879–1886. 10.1182/blood-2006-08-040980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb F. S., Hook J. S., Hilkin B. M., Huber J. N., Volk A. P., Moreland J. G. (2012). Endotoxin priming of neutrophils requires endocytosis and NADPH oxidase-dependent endosomal reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 12395–12404. 10.1074/jbc.M111.306530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammermann T., Afonso P. V., Angermann B. R., Wang J. M., Kastenmuller W., Parent C. A., et al. (2013). Neutrophil swarms require LTB4 and integrins at sites of cell death in vivo. Nature, 498, 371–375. 10.1038/nature12175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan F., Yuan B., Liu T., Luo X., Huang P., Liu Y., et al. (2016). Interleukin-33 facilitates neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in S. aureus-caused peritonitis. Mol. Immunol. 72, 74–80. 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le H. T., Tran V. G., Kim W., Kim J., Cho H. R., Kwon B. (2012). IL-33 priming regulates multiple steps of the neutrophil-mediated anti-Candida albicans response by modulating TLR and dectin-1 signals. J. Immunol. 189, 287–295. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie C. C. (2004). Regulation of arachidonic acid availability for eicosanoid production. Biochem. Cell Biol. 82, 1–17. 10.1139/o03-080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles W. C., Ledbetter J. A., Waltersdorph A. W., Klebanoff S. J. (1995). Cross-linking of CD18 primes human neutrophils for activation of the respiratory burst in response to specific stimuli: implications for adhesion-dependent physiological responses in neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 58, 690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann A., Riedel D., Oster W., Meuer S. C., Blohm D., Mertelsmann R. H., et al. (1988). Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces interleukin 1 production by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J. Immunol. 140, 837–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. J., Song C. W., Yue Y., Duan C. G., Yang J., He T., et al. (2005). Quercetin inhibits LPS-induced delay in spontaneous apoptosis and activation of neutrophils. Inflamm. Res. 54, 500–507. 10.1007/s00011-005-1385-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lominadze G., Powell D. W., Luerman G. C., Link A. J., Ward R. A., McLeish K. R. (2005). Proteomic analysis of human neutrophil granules. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 1503–1521. 10.1074/mcp.M500143-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorincz A. M., Schutte M., Timar C. I., Veres D. S., Kittel A., McLeish K. R., et al. (2015). Functionally and morphologically distinct populations of extracellular vesicles produced by human neutrophilic granulocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 98, 583–589. 10.1189/jlb.3VMA1014-514R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Jones S. M., Peters-Golden M., Brock T. G. (2003). Nuclear localization of 5-lipoxygenase as a determinant of leukotriene B4 synthetic capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12165–12170. 10.1073/pnas.2133253100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makni-Maalej K., Boussetta T., Hurtado-Nedelec M., Belambri S. A., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., El-Benna J. (2012). The TLR7/8 agonist CL097 primes N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine-stimulated NADPH oxidase activation in human neutrophils: critical role of p47phox phosphorylation and the proline isomerase Pin1. J. Immunol. 189, 4657–4665. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makni-Maalej K., Marzaioli V., Boussetta T., Belambri S. A., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., Hurtado-Nedelec M., et al. (2015). TLR8, but not TLR7, induces the priming of the NADPH oxidase activation in human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 97, 1081–1087. 10.1189/jlb.2A1214-623R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso P., Nana-Sinkam P., Peters-Golden M. (2001). Leukotriene B4 augments neutrophil phagocytosis of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 69, 2011–2016. 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2011-2016.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marasco W. A., Showell H. J., Becker E. L. (1981). Substance P binds to the formylpeptide chemotaxis receptor on the rabbit neutrophil. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 99, 1065–1072. 10.1016/0006-291X(81)90727-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marucha P. T., Zeff R. A., Kreutzer D. L. (1991). Cytokine-induced IL-1 beta gene expression in the human polymorphonuclear leukocyte: transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation by tumor necrosis factor and IL-1. J. Immunol. 147, 2603–2608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroianni C. M., d'Ettorre G., Forcina G., Lichtner M., Mengoni F., D'Agostino C., et al. (2000). Interleukin-15 enhances neutrophil functional activity in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 96, 1979–1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayadas T. N., Cullere X. (2005). Neutrophil beta2 integrins: moderators of life or death decisions. Trends Immunol. 26, 388–395. 10.1016/j.it.2005.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer T. Z., Simard F. A., Cloutier A., Vardhan H., Dubois C. M., McDonald P. P. (2013). The p38-MSK1 signaling cascade influences cytokine production through CREB and C/EBP factors in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 191, 4299–4307. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGettrick H. M., Lord J. M., Wang K. Q., Rainger G. E., Buckley C. D., Nash G. B. (2006). Chemokine- and adhesion-dependent survival of neutrophils after transmigration through cytokine-stimulated endothelium. J. Leukoc. Biol. 79, 779–788. 10.1189/jlb.0605350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish K. R., Klein J. B., Lederer E. D., Head K. Z., Ward R. A. (1996). Azotemia, TNF alpha, and LPS prime the human neutrophil oxidative burst by distinct mechanisms. Kidney Int. 50, 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish K. R., Knall C., Ward R. A., Gerwins P., Coxon P. Y., Klein J. B., et al. (1998). Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades during priming of human neutrophils by TNF-alpha and GM-CSF. J. Leukoc. Biol. 64, 537–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish K. R., Merchant M. L., Creed T. M., Tandon S., Barati M. T., Uriarte S. M., et al. (2017). Frontline Science: tumor necrosis factor-α stimulation and priming of human neutrophil granule exocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1189/jlb.3HI0716-293RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish K. R., Uriarte S. M., Tandon S., Creed T. M., Le J., Ward R. A. (2013). Exocytosis of neutrophil granule subsets and activation of prolyl isomerase 1 are required for respiratory burst priming. J. Innate Immun. 5, 277–289. 10.1159/000345992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby K., Midtvedt T., Degre M. (1982). Effect of human leukocyte interferon on phagocytic activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. B 90, 181–184. 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1982.tb00102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshki J., Tuluc F., Bredetean O., Ding Z., Kunapuli S. P. (2004). Molecular mechanism of nucleotide-induced primary granule release in human neutrophils: role for the P2Y2 receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C264–C271. 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesri M., Altieri D. C. (1998). Endothelial cell activation by leukocyte microparticles. J. Immunol. 161, 4382–4387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocsai A., Ligeti E., Lowell C. A., Berton G. (1999). Adhesion-dependent degranulation of neutrophils requires the Src family kinases Fgr and Hck. J. Immunol. 162, 1120–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucco F., Steffens S., Burger F., Da Costa A., Bianchi G., Bertolotto M., et al. (2008). Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) induces integrin CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1) up-regulation and migration to the CC chemokine CCL3 (MIP-1alpha) on human neutrophils through defined signalling pathways. Cell. Signal. 20, 557–568. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland J. G., Davis A. P., Matsuda J. J., Hook J. S., Bailey G., Nauseef W. M., et al. (2007). Endotoxin priming of neutrophils requires NADPH oxidase-generated oxidants and is regulated by the anion transporter ClC-3. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33958–33967. 10.1074/jbc.M705289200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A. C., Brittan M., Wilkinson T. S., McAuley D. F., Antonelli J., McCulloch C., et al. (2011). C5a-mediated neutrophil dysfunction is RhoA-dependent and predicts infection in critically ill patients. Blood 117, 5178–5188. 10.1182/blood-2010-08-304667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutsopoulos N. M., Konkel J., Sarmadi M., Eskan M. A., Wild T., Dutzan N., et al. (2014). Defective neutrophil recruitment in leukocyte adhesion deficiency type I disease causes local IL-17-driven inflammatory bone loss. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 229ra40. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J., Barbara J. A., Dunkley S. A., Lopez A. F., Van Ostade X., Condliffe A. M., et al. (1997). Regulation of neutrophil apoptosis by tumor necrosis factor-alpha: requirement for TNFR55 and TNFR75 for induction of apoptosis in vitro. Blood 90, 2772–2783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musso T., Calosso L., Zucca M., Millesimo M., Puliti M., Bulfone-Paus S., et al. (1998). Interleukin-15 activates proinflammatory and antimicrobial functions in polymorphonuclear cells. Infect. Immun. 66, 2640–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naegele M., Tillack K., Reinhardt S., Schippling S., Martin R., Sospedra M. (2012). Neutrophils in multiple sclerosis are characterized by a primed phenotype. J. Neuroimmunol. 242, 60–71. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. (2006). Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 173–182. 10.1038/nri1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauseef W. M., Borregaard N. (2014). Neutrophils at work. Nat. Immunol. 15, 602–611. 10.1038/ni.2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth T., Mocsai A. (2016). Feedback amplification of neutrophil function. Trends Immunol. 37, 412–424. 10.1016/j.it.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan B., Collette H., Baker S., Duffy A., De M., Miller C., et al. (2000). Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis after severe trauma is NFkappaβ dependent. J. Trauma 48, 599–604; discussion: 604–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty J. T., Showell H. J., Becker E. L., Ward P. A. (1979). Neutrophil aggregation and degranulation. Effect of arachidonic acid. Am. J. Pathol. 95, 433–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura H., Tanaka H., Koh T., Hashiguchi N., Kuwagata Y., Hosotsubo H., et al. (1999). Priming, second-hit priming, and apoptosis in leukocytes from trauma patients. J. Trauma 46, 774–781; discussion: 781–773. 10.1097/00005373-199905000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmantier R., Surette M. E., Sanchez A., Braquet P., Borgeat P. (1994). Priming for the synthesis of 5-lipoxygenase products in human blood ex vivo by human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Lab. Invest. 70, 696–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsson J. M., Jacobson S. H., Lundahl J. (2010). Neutrophil activation during transmigration in vivo and in vitro A translational study using the skin chamber model. J. Immunol. Methods 361, 82–88. 10.1016/j.jim.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perianayagam M. C., Balakrishnan V. S., King A. J., Pereira B. J., Jaber B. L. (2002). C5a delays apoptosis of human neutrophils by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-signaling pathway. Kidney Int. 61, 456–463. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perianin A., Snyderman R., Malfroy B. (1989). Substance P primes human neutrophil activation: a mechanism for neurological regulation of inflammation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 161, 520–524. 10.1016/0006-291X(89)92630-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perussia B., Kobayashi M., Rossi M. E., Anegon I., Trinchieri G. (1987). Immune interferon enhances functional properties of human granulocytes: role of Fc receptors and effect of lymphotoxin, tumor necrosis factor, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Immunol. 138, 765–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]