Abstract

Objective:

To clarify the association between pain and sleep in fibromyalgia.

Methods:

Electronic databases, including PsycINFO, the Cochrane database for systematic reviews, PubMed, EMBASE, and Ovid were searched to identify eligible articles. Databases independently screened and the quality of evidence using a reliable and valid quality assessment tool was assessed.

Results:

In total, 16 quantitative studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. According to the results, increased pain in fibromyalgia was associated with reduced sleep quality, efficiency, and duration and increased sleep disturbance and onset latency and total wake time. Remarkably, depressive symptoms were also related to both pain and sleep in patients with fibromyalgia.

Conclusion:

Management strategies should be developed to decrease pain while increasing sleep quality in patients with fibromyalgia. Future studies should also consider mood disorders and emotional dysfunction, as comorbid conditions could occur with both pain and sleep disorder in fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a complicated musculoskeletal syndrome that affects between 0.7% and 4.8% of the global population.1 Most (90%) individuals with FM are women.2 According to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the criteria for FM diagnosis include pain for at least 3 months, but FM patients also experience poor sleep, fatigue, depression, stress, and anxiety.3 Most (90%) FM patients experience sleep disorder,2,4,5,7 which exerts a negative effect on health-related quality of life, leading to issues such as unrefreshing sleep and daytime tiredness, causing difficulties with wakefulness.8 Observational evidence indicates that FM patients’ pain is directly related to poor sleep.9,10 Several aspects of sleep, including duration, disturbance, and efficiency, could be related to pain.11 In addition, poor sleep has been shown to decrease both pain thresholds12 and cognitive skills in pain management.13 Moreover, a longitudinal analysis showed that interactivity between pain and sleep disturbance was associated with depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis,14 and patients with FM have also been found to experience comorbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, and stress.3,15

Although sleep and pain have been evaluated frequently in patients with chronic pain, the nature of the relationship between these variables remains unclear in FM. Identifying the relationship between pain and sleep in FM could provide insight for the development of efficient interventions. Therefore, the goal of this systematic review was to 1) determine whether pain is related to sleep, 2) identify the sleep dimensions related to pain in FM, and 3) provide information regarding future research directions, to facilitate the achievement of better health outcomes in FM.

Methods

This systematic review aimed to examine the relationship between pain and sleep in FM. While the studies included in the review were not based on the assessment of interventions, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines16 were considered during the review. The methodology used in the review was similar to strategies used in previous research11,17 and involved 3 stages. Stage 1 consisted of a systematic examination of the literature using keywords. Stage 2 involved a) scanning related article titles and abstracts according to particular inclusion criteria, and b) examination of full papers and extraction of evidence. Stage 3 involved the use of a valid quality assessment instrument to classify the included studies according to quality.

Literature search

The literature search was completed between November 2011 and March 2016. Electronic databases, including PsycINFO (until December 2012), the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, PubMed, EMBASE, and Ovid (from October 2015 to March 2016), were searched. The database search was performed using a combination of several keywords including “fibromyalgia,” “fibromyalgia syndrome,” “chronic pain,” “pain,” “sleep,” “sleep quality,” “problematic sleep,” and “sleep disturbance/s.” Moreover, the reference lists of all related articles were scanned to identify additional relevant articles.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were selected according to language (English), year of publication (from 1990 to 2015), research methods (quantitative), and variables (pain and sleep in FM). The inclusion criteria were as follows: FM patients aged 18 years or older and diagnosed with FM according to ACR criteria as participants 3). The results of the included studies were retrieved according to the significance level for the results, which was set at p<0.05. The included studies used different measurement tools to assess sleep and pain. The studies could include measurement of other FM symptoms such as depression, stress, physical functioning, fatigue, and anxiety. However, the review focused mainly on remarkable findings regarding pain and sleep, to improve understanding of these variables in FM. Several studies that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, such as those that did not measure pain and sleep simultaneously, were excluded from the review. In addition, studies examining only facial pain in FM were excluded to avoid misconception.

Assessment of evidence quality

Authors used the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment instrument18 to categorize the selected studies according to quality. Classifications were then compared to make final decisions regarding the quality of each study. The EPHPP quality assessment instrument was used to analyze the following 6 factors: selection bias, allocation bias, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals and drop-outs.18 Quality for each factor was rated as “high,” “medium,” or “low.” Overall research quality was considered high, medium, and low if these factors received only high ratings, <4 high ratings and one low rating, and ≥2 low ratings, respectively. This tool has been identified as a suitable quality assessment instrument for the evaluation of randomized controlled trials and non-randomized controlled trials.19 In addition, it has been used in >30 systematic reviews.18

This systematic review aimed to answer current research questions by systematically specifying, selecting, and critically evaluating related research and analyzing the evidence from the included studies. Systematic reviews may or may not include statistical analysis (meta-analysis) to summarize the findings.16 As the included studies varied in terms of methodology, participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, and other factors, statistical analysis was not included in the current systematic review, and the evidence was synthesized qualitatively.

Results

Literature search

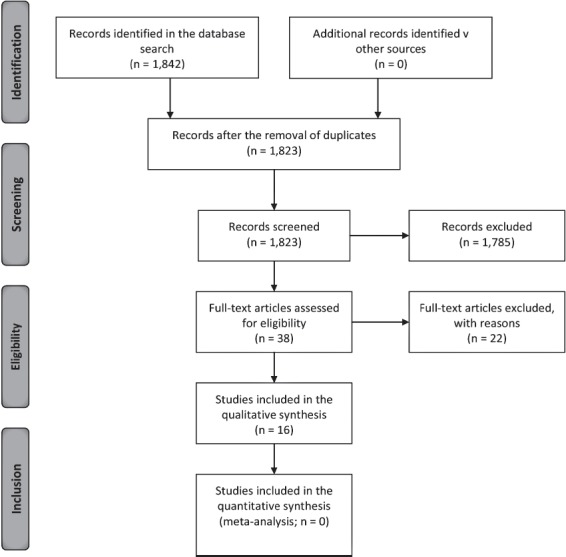

Of 1,842 database citations, 16 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for the systematic review (Figure 1). The publication years for the included studies ranged from 1996 to 2015. In addition, the research designs used in the selected studies varied (Table 1). The studies were conducted in the United States,20-29 Spain,30-32 the United Kingdom,33,34 and Turkey.35

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram illustrating the study inclusion process, adapted from Moher et al.16

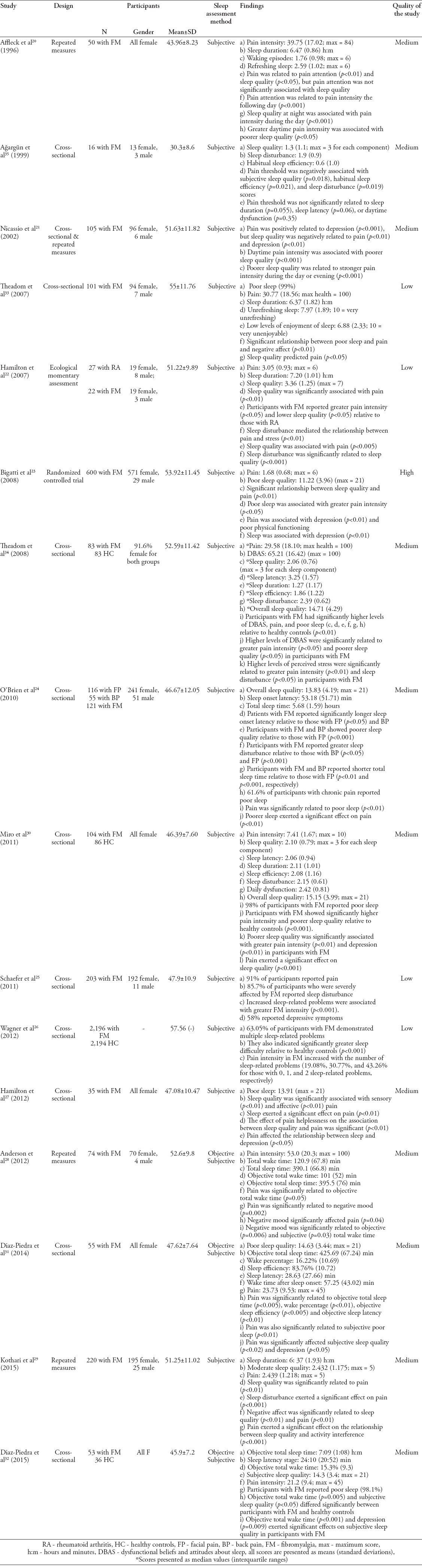

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the studies and comparison of the outcomes.

Assessment of the quality of included studies

According to the EPHPP assessment tool, one study demonstrated high,23 11 studies demonstrated medium20,21,24,27-32,34,35 and 4 studies demontrated as low quality.25-27,33 (Table 1).

Outcome measures. Pain assessment tools

Most of the studies (n=6) measured pain using the McGill Pain Questionnaire, which has demonstrated very good reliability36 and validity,37 and one study used the shorter version of this scale, which has shown good reliability and validity.38 Three studies used the visual analog scale, which has shown good reliability and validity in various populations.39-41 Two studies used sensory testing, which evaluates pain threshold on the fingers.42,43 One study used the pain rating index, which is known to be an effective instrument.44-46 Two studies used ecological momentary assessment, which involves multiple assessments of individuals in their natural environments.47,48 In addition, 2 studies used 3 pain subscales from various validated questionnaires,49,50 and one study used the Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire, which measures several health domains including pain.

Sleep assessment tools. Subjective tools

Most of the studies (n=10) assessed sleep using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,51,52 which has demonstrated reliability and validity. In addition, 2 studies used different reliable, valid questionnaires,53,54 and 2 studies used sleep diaries via ecological momentary assessment, which has been identified as effective assessment method.55,56 Another study used a sleep subscale from a different validated questionnaire.49 However, several studies used multiple measurement tools to evaluate sleep.

Objective tools

Two studies used polysomnography (PSG) recording, which allows objective assessment of sleep parameters.57 Polysomnography is a very reliable means of assessing sleep in patients with chronic conditions.58,59 In addition, one study used actigraphy, which is strongly associated with PSG with respect to sleep duration.60,61

Dimension of sleep

Sleep duration was subjectively assessed in 8 studies20,22,24,29,30,33-35 and objectively assessed in 2 studies.31,32 One study28 assessed sleep duration both objectively and subjectively. In addition, 4 studies24,28,31,32 indicated reductions in total sleep time in FM patients. One study31 reported that objective total sleep time was significantly associated with pain, while another study35 found that this relationship was non-significant. In total, 9 studies of medium quality and 2 studies of low quality consistently demonstrated reduced sleep duration in FM patients.

Sleep quality was subjectively evaluated by 13 studies20-24,27,29-35 Studies of high (n=1), medium (n=9), and low quality (n=2) reported poor sleep quality in FM. Most studies found a significant relationship between pain and poor sleep quality in individuals with FM. Sleep disturbance was assessed subjectively in 8 studies22,24-26,29,30,34,35 In total, medium (n=5) and low quality (n=3), consistently reported that FM patients experienced pain and sleep disturbance. In addition, 4 studies reported subjective24,30,34,35 and 2 studies reported objective31,32 sleep onset latency. In total, 6 studies of medium quality reported that sleep onset latency ranged between approximately 24 and 58 min. Three studies of medium quality examined objective total wake time;28,31,32 of these, 2 studies reported that total wake time was significantly associated with pain in individuals with FM.28,31

Moreover, 3 and 2 studies of medium quality reported reduced subjective30,34,35 and objective31,32 sleep efficiency, respectively. In addition, 2 of these studies31,35 found that sleep efficiency was significantly associated with pain in FM patients. One medium quality study34 showed relationships between dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep and poor sleep quality and pain in FM (Table 1).

Overall sleep

Nine studies (one high, 5 medium, and 3 low quality) found that sleep exerted a significant effect on pain in FM;20-24,26,27,29,33 however, one study of medium quality28 failed to demonstrate this effect. In contrast, 4 studies of medium quality21,30,31,35 showed that pain significantly influenced sleep. However, in 2 studies of medium quality,23,32 this effect was nonsignificant (Table 1).

Pain, sleep, and mood

A few studies (2 medium and one low quality) demonstrated that negative affect and stress were associated with sleep quality29,33 and pain.29,34 Similarly, one study of medium quality showed that negative mood was significantly related to pain and objective and subjective total wake time.28 In addition, one study of medium quality showed that negative mood mediated the relationship between pain and sleep in FM.24 In contrast, 7 studies (one high, 5 medium, and one low quality) reported that FM patients experienced depression.21,23,25,27,30-32 Moreover, depression was independently associated with pain and sleep in FM.21,23,27 Two studies of moderate quality indicated that pain and sleep quality influenced depression independently;31,32 however, only one of these studies demonstrated that depression influenced sleep directly32 (Table 1).

Summary

The findings demonstrated a significant association between pain and poor sleep in FM patients. In addition, pain exerted a significant effect on sleep, and sleep exerted a significant effect on pain. However, although only half of the studies included in the review analyzed psychological variables, the finding that depression was associated with both pain and sleep in FM patients was remarkable (Table 1).

Discussion

The objective of this systematic review was to enhance understanding regarding the relationship between pain and sleep in FM. The findings showed that FM patients who experienced intense pain also experienced poor sleep. More specifically, several sleep dimensions, including total wake time and sleep quality, disturbance, efficiency, onset latency, and duration, were associated with pain in FM patients.

The results of the review indicated that FM patients experienced greater pain intensity and poorer sleep (manifested as sleep disturbance, daytime sleepiness, and daytime dysfunction) relative to healthy individuals.26,30,32,34 In addition, overall sleep was negatively associated with pain in FM patients. Disorders in the dimensions of sleep could affect overall sleep, which could interact with pain.11

The findings identified sleep disturbance, which was associated with pain,35 as a sleep dimension that FM patients experienced frequently.22,24-26,29,30,34,35 Sleep disturbance could be regarded as failure of the reparative function of sleep,62-64 which could cause hyperalgesia.13,65-68 Patients with chronic pain, including FM, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, cancer pain, headaches, and chronic fatigue syndrome, reported different types of sleep disturbance.11,69,70 Moreover, sleep disturbance has been identified as a principal symptom of FM5,71 and associated with both sleep quality and pain intensity.72-74 Sleep disturbance in FM has been defined as difficulty falling asleep and maintaining sleep, reductions in sleep time, multiple interruptions to sleep during the night, and unfreshing sleep.72,75-77 These problems could result in poor sleep quality, reduced sleep efficiency, and increased sleep onset latency.64,78 The results of this review are consistent with those of previous studies that reported increased sleep onset latency, reduced sleep duration, and poor sleep efficiency in FM patients. Sleep efficiency was associated with both subjective and objective pain,31,35 while total wake time was associated solely with objective pain, in FM patients.28,31 The review also included one study31 indicating that pain was objectively related to sleep duration and sleep onset latency. However, another study35 did not observe subjective relationships between these sleep dimensions and pain. Although both studies31,35 were of medium quality, various findings in the review could have resulted from differences between objective and subjective sleep measurements.

The association between pain and sleep is complicated.79 Clinical and experimental evidence has indicated that chronic pain is associated with increased levels of irritability during sleep,80,81-83 resulting in awakening.84 Several longitudinal studies involving patients with chronic pain have established that pain and poor sleep could affect one another.67,80 The findings of this review support the results of previous research suggesting that pain and sleep share a bidirectional relationship, which is difficult to understand in FM. The number of studies indicating that sleep influenced pain was higher relative to that of studies suggesting that pain influenced sleep.

However, pain and sleep might not share a direct relationship in FM.82,85 This relationship could be affected by various factors, including mood disorders, in patients with chronic pain.86-92 The current findings21,23,25,27,30-32 indicated that FM patients experienced depression in parallel with pain and poor sleep. In addition, few studies in the review considered the significant role of pain-related cognition, such as pain attention20 and pain helplessness,27 in pain intensity. Moreover, negative effect has been associated with poor sleep in individuals with chronic pain.93-96 Consistent with the results of previous research, the current findings24,28,29,33 suggest that negative mood in FM patients could affect the association between pain and sleep disturbance, as a covariate. Considering that these patients generally experience greater stress relative to healthy individuals,97-99 it is not surprising that negative emotional functioning interacts with FM symptoms. Although this review provides important insights into the association between pain and sleep in FM, it was subject to several limitations that should be noted. Most studies included in the review used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to assess sleep subjectively, while few studies used objective measures such as PSG and actigraphy. However, some differences were observed between the studies that used objective and subjective sleep assessments. Despite the finding that objective and subjective sleep assessment methods are moderately related,100,101 they have different functions in sleep assessment.11,102 Moreover, the observational findings of some studies did not allow inference of a causal relationship between pain and sleep. Although we used the EPHPP, which is a valid, reliable quality assessment tool,18,19 the studies included in the review were generally of lower quality because of their study designs. Overall, the findings should be considered with caution, as some studies of the same quality reported contradictory results. This could be explained by differences in research methods between the studies or authors’ misconceptions regarding the quality assessment process. Furthermore, some studies in the review regarding sleep quality as a sleep dimension, while others considered it an overall sleep score. Therefore, the results were difficult to interpret. In addition, the relationship between pain and sleep could be influenced by other FM symptoms that were not identified in the review. The studies in the review differed in terms of sample size, participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, reporting of control variables, and research methods. These differences could have affected both the interpretation and summary of the results.

The review indicated that the relationship between pain and sleep could be bidirectional in FM. In addition, this relationship could interact with depressive symptoms. Findings suggested that several dimensions of sleep, including sleep disturbance, onset latency, and efficiency, were associated with pain in FM. More specifically, sleep disturbance was identified as the most important sleep dimension and should be the focus of FM research. This review is significant, as it sought to enhance understanding of the association between sleep and pain in FM in the context of subjective and objective sleep dimensions. This could guide future research that aims to improve health-related quality of life in FM patients. The enhancement of sleep could reduce pain, and reductions in pain could enhance sleep in FM patients. However, additional studies involving mixed designs are required to determine whether 1) pain drives poor sleep, 2) poor sleep leads to greater pain intensity, and 3) pain and sleep share an indirect relationship that interacts with depression in FM. In addition, further studies examining sleep should use both objective and subjective measurement tools where available, as differences between sleep assessment tools could lead to misconceptions. In light of comprehensive research, multidisciplinary interventions should be developed to reduce pain and depressive symptoms and enhance sleep quality, which could improve health outcomes for patients with FM.

Acknowledgment

Authors gratefully acknowledge Ezaldeen Al Subainy for his assistance with the Arabic translation of the abstract. Also, the authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. Finally, they would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable recommendations.

References

- 1.Bergman S. A general practice approach to management of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain and fibromyalgia (Revised) In: Adebajo OA, Dickson J, editors. Collected Reports on the Rheumatic Diseases. Series 4 (Revised) Halmstad (SW): Arthritis Research Campaign; 2005. pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe F. New American College of Rheumatology Criteria for Fibromyalgia: A Twenty-Year Journey. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:583–584. doi: 10.1002/acr.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cote KA, Moldofsky H. Sleep, daytime symptoms, and cognitive performance in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:2014–2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaver JL, Lentz M, Landis CA, Heitkemper MM, Buchwald DS, Woods NF. Sleep, psychological distress, and stress arousal in women with fibromyalgia. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:247–257. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199706)20:3<247::aid-nur7>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lashley FR. A review of sleep in selected immune and autoimmune disorders. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003;17:65–80. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mease P, Arnold LM, Choy EH, Clauw DJ, Crofford LJ, Glass JM, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome module at OMERACT 9: domain construct. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2318–2329. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Consoli G, Marazziti D, Ciapparelli A, Bazzichi L, Massimetti G, Giacomelli C, et al. The impact of mood, anxiety, and sleep disorders on fibromyalgia. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:962–967. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Affleck G, Tennen H, Urrows S, Higgins P, Abeles M, Hall C, et al. Fibromyalgia and women’s pursuit of personal goals: a daily process analysis. Health Psychol. 1998;17:40–47. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Mease PJ, Burgess SM, Palmer SC, Abetz L, et al. Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly GA, Blake C, Power CK, O’Keeffe D, Fullen BM. The association between chronic low back pain and sleep: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:169–181. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f3bdd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu YH, Silmana AJ, Macfarlane GJ, Ray D, Gupta A, Dickens C, et al. Poor sleep and depression are independently associated with a reduced pain threshold. Results of a population based study. Pain. 2005;115:316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kundermann B, Spernal J, Huber MT, Krieg JC, Lautenbacher S. Sleep deprivation affects thermal pain thresholds but not somatosensory thresholds in healthy volunteers. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:932–937. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145912.24553.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicassio PM, Wallston KA. Longitudinal relationships among pain, sleep problems, and depression in rheumatoid arthritis. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:514–520. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnold LM, Hudson JI, Keck PE, Auchenbach MB, Javaras KN, Hess EV. Comorbidity of fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1219–1225. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati M, Tetzlaff AJ, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:118–121. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.3.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effective Public Health Practice Projec. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. [[cited 2009]]. Available from http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html .

- 19.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1–173. doi: 10.3310/hta7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Affleck G, Urrows S, Tennen H, Higgins P, Abeles M. Sequential daily relations of sleep, pain intensity, and attention to pain among women with fibromyalgia. Pain. 1996;68:363–368. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicassio PM, Moxham EG, Schuman CE, Gevirtz RN. The contribution of pain, reported sleep quality, and depressive symptoms to fatigue in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2002;100:271–279. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton N, Catley D, Karlson C. Sleep and the affective response to stress and pain. Health Psychol. 2007;26:288–295. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bigatti SM, Hernandez AM, Cronan TA, Rand KL. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: Relationship to pain and depression. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59:961–967. doi: 10.1002/art.23828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien EM, Waxenberg LB, Atchison JW, Gremillion HA, Staud RM, McCrae CS, et al. Negative mood mediates the effect of poor sleep on pain among chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:310–319. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181c328e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaefer C, Chandran A, Hufstader M, Baik R, McNett M, Goldenberg D, et al. The comparative burden of mild, moderate and severe fibromyalgia: results from a cross-sectional survey in the United States. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner JS, DiBonaventura MD, Chandran AB, Cappelleri JC. The association of sleep difficulties with health-related quality of life among patients with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton NA, Pressman M, Lillis T, Atchley R, Karlson C, Stevens N. Evaluating evidence for the role of sleep in fibromyalgia: A test of the sleep and pain diathesis model. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:806–814. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9421-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson RJ, McCrae CS, Staud R, Berry RB, Robinson ME. Predictors of clinical pain in fibromyalgia: Examining the role of sleep. J Pain. 2012;13:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kothari DJ, Davis MC, Yeung EW, Tennen HA. Positive affect and pain : mediators of the within-day relation linking sleep quality to activity interference in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2015;156:540–546. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460324.18138.0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miro E, Martinez MP, Sanchez AI, Prados G, Medina A. When is pain related to emotional distress and daily functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome?The mediating roles of self-efficacy and sleep quality. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16:799–814. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diaz-Piedra C, Catena A, Miro E, Martinez MP, Sanchez AI, Buela-Casal G. The impact of pain on anxiety and depression is mediated by objective and subjective sleep characteristics in fibromyalgia patients. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:852–859. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz-Piedra C, Catena A, Sánchez AI, Miró E, Pilar Martínez MM, Buela-Casal G. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: The role of clinical and polysomnographic variables explaining poor sleep quality in patients. Sleep Med. 2015;16:917–925. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theadom A, Cropley M, Humphrey KL. Exploring the role of sleep and coping in quality of life in fibromyalgia. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theadom A, Cropley M. Dysfunctional beliefs, stress and sleep disturbance in fibromyalgia. Sleep Med. 2008;9:376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ağargün MY, Tekeoğlu I, Güneş A, Adak B, Kara H, Ercan M. Sleep quality and pain threshold in patients with fibromyalgia. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40:226–228. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Love A, Leboeuf C, Crisp TC. Chiropractic chronic low back pain sufferers and self-report assessment methods. Part I. A reliability study of the Visual Analogue Scale, the Pain Drawing and the McGill Pain Questionnaire. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearce J, Morley S. An experimental investigation of the construct validity of the McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1989;39:15–121. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burckhardt CS, Clark S, Bennett RM. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryce TN, Budh CN, Cardenas DD, Dijkers M, Felix ER, Finnerup NB, et al. Pain after spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. Report of the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Spinal Cord Injury Measures meeting. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:421–440. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2007.11753405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen MP. Measurement of Pain. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, editors. Bonica’s management of pain. Philadelphia (PA): Williams &Wilkins; 2010. pp. 251–270. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain. 2011;152:2399–2404. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raymond NC, de Zwaan M, Fails PL, Nugent SM, Ackard DM, Crosby RD, et al. Pain thresholds in obese binge-eating disorders subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;37:202–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00244-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ağargün MY, Tekeooğu I, Kara H, Adak B, Ercan M. Hypnotizability, pain threshold, and dissociative experiences. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:69–71. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicassio PM, Radojevic V, Schoenfeld-Smith K, Dwyer K. The contribution of family cohesion and the pain-coping process to depressive symptoms in fibromyalgia. Ann Behav Med. 1995;17:349–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02888600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicassio PM, Schoenfeld-Smith K, Radojevic V, Schuman C. Pain coping mechanisms in fibromyalgia: relationship to pain and functional outcomes. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1552–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicassio PM, Schuman C, Radojevic V, Weisman MH. Helplessness as a mediator of health status in fibromyalgia. Cognit Ther Res. 1999;23:181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stone A, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Ann Behav Med. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stone AA, Broderick JE, Porter LS, Kaell AT. The experience of rheumatoid arthritis pain and fatigue: Examining momentary reports and correlates over one week. Arthritis Care Res. 1997;10:185–193. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mason JH, Silverman SL, Weaver AL, Simms RW. Impact of fibromyalgia on multiple aspects of health status. Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;94:33. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkinson C, Stewart-Brown S, Petersen S, Paice C. Assessment of the SF-36 version 2 in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol. 1999;53:46–50. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicassio PM, Ormseth SR, Custodio MK, Olmstead R, Weisman MH, Irwin MR. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12:1–12. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.720315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cole JC, Motivala SJ, Buysse DJ, Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Irwin MR. Validation of a 3-factor scoring model for the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in older adults. Sleep. 2006;29:112. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK. Psychometric comparisons of the standard and abbreviated DBAS-10 versions of the dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep questionnaire. Sleep Med. 2001;2:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15:376–381. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tennen H, Affleck G. Daily processes in coping with chronic pain: methods and analytic strategies. In: Zeidner M, Endler N, editors. Handbook of Coping. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1996. pp. 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moskowitz DS, Young SN. Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31:13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCall WV, Erwin CW, Edinger JD, Krystal AD, Marsh GR. Ambulatory polysomnography: technical aspects and normative values. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;9:68–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Donoghue GM, Fox N, Heneghan C, Hurley DA. Objective and subjective assessment of sleep in chronic low back pain patients compared with healthy age and gender matched controls: a pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;2:101–122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pejovic S, Natelsonö BH, Basta M, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Mahr F, Vgontzas AV. Chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia in diagnosed sleep disorders: a further test of the ‘unitary’ hypothesis. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:53. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lichstein KL, Stone KC, Donaldson J, Nau SD, Soeffing JP, Murray D, et al. Actigraphy validation with insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft M, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. American Academy of Sleep Medicine Review Paper. Sleep. 2003;26:342–392. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lentz MJ, Landis CA, Rothermel J, Shaver JL. Effects of selective slow wave sleep disruption on musculoskeletal pain and fatigue in middle aged women. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1586–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Older SA, Battafarano DF, Danning CL, Ward JA, Grady EP, Derman S, et al. The effects of delta wave sleep interruption on pain thresholds and fibromyalgia-like symptoms in healthy subjects;correlations with insulin-like growth factor I. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1180–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lautenbacher S, Kundermann B, Krieg JC. Sleep deprivation and pain perception. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:357–369. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilson KG, Watson ST, Currie SR. Daily diary and ambulatory activity monitoring of sleep in patients with insomnia associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 1998;75:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Onen SH, Alloui A, Gross A, Eschallier A, Dubray C. The effects of total sleep deprivation, selective sleep interruption and sleep recovery on pain tolerance thresholds in healthy subjects. J Sleep Res. 2001;10:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edwards RR, Almeida DM, Klick B, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT. Duration of sleep contributes to next-day pain report in the general population. Pain. 2008;137:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dzierzewski JM, Williams JM, Roditi D, Marsiske M, McCoy K, McNamara J, et al. Daily variations in objective night time sleep and subjective morning pain in older adults with insomnia: Evidence of covariation over time. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:925–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marty M, Rozenberg S, Duplan B, Thomas P, Duquesnoy B, Allaert F. Quality of sleep in patients with chronic low back pain: a case-control study. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:839–844. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0660-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parrino L, Zucconi M, Terzano M. Sleep fragmentation and arousal in the pain patient. In: Lavigne G, Sessle B, Choiniere M, et al., editors. Sleep and Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 2007. pp. 213–231. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moldofsky H. The contribution of sleep-wave physiology for fibromyalgia. Adv Pain Res Ther. 1990;17:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perlis ML, Giles DE, Bootzin RR, Dikman ZV, Fleming GM, Drummond SPA, et al. Alpha sleep and information processing, perception of sleep, pain and arousability in fibromyalgia. Int J Neurosci. 1997;89:265–280. doi: 10.3109/00207459708988479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.MacDonald S, Linton SJ, Jansson-Frojmark M. Cognitive vulnerability in the development of concomitant pain and sleep disturbances. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15:417–434. doi: 10.1348/135910709X468089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moldofsky H. Rheumatic manifestations of sleep disorders. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:59–63. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328333b9cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moldofsky H. Management of sleep disorders in fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2002;28:353–365. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(01)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.White KP, Speechley M, Harth M, Ostbye T. The London Fibromyalgia Epidemiology Study: Comparing the demographic and clinical characteristics in 100 random community cases of fibromyalgia versus controls. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1577–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cohen MJM, Menefee LA, Doghramji l, Anderson WR, Frank ED. Sleep in chronic pain: Problems and treatments. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2000;12:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Landis CA, Lentz MJ, Rothermel J, Buchwald D, Shaver JL. Decreased sleep spindles and spindle activity in midlife women with fibromyalgia and pain. Sleep. 2004;27:741–750. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilson KG, Eriksson MY, D’Eon JL, Mikail SF, Emery PC. Major depression and insomnia in chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:77–83. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain interrelate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:119–132. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Deardorff W. Breaking the cycle of chronic pain and insomnia. [[cited 2005]]. Available from http://www.spine-health.com/wellness/sleep/chronic-pain-and-insomnia-breaking-cycle .

- 82.Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14:1539–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ohayon MM. Relationship between chronic painful physical condition and insomnia. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carrette S. Fibromyalgia 20 years later: what have we really accomplished? J Rheumatol. 1995;22:590–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tang NK, Goodchild CE, Sanborn AN, Howard J, Salkovskis PM. Deciphering the temporal link between pain and sleep in a heterogeneous chronic pain patient sample: a multilevel daily process study. Sleep. 2012;35:675A–687A. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harrison L, Wilson S, Heron J, Stannard C, Munafò M. Exploring the associations shared by mood, pain-related attention and pain outcomes related to sleep disturbance in a chronic pain sample. Psychol Health. 2016;446:1–13. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2015.1124106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hall M, Buysse DJ, Nowell PD, Nofzinger EA, Houck P, Reynolds CF, et al. Symptoms of stress and depression ascorrelates of sleep in primary insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:227–230. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Engel CC, von Korff M, Katon WJ. Back pain in primary care: Predictors of high health-care costs. Pain. 1996;65:197–204. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Okifuji A, Turk DC, Sherman JJ. Evaluation of the relationship between depression and fibromyalgia syndrome: Why aren’t all patients depressed? J Rheumatol. 2000;27:212–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Berber JSS, Kupek E, Berber SC. Prevalence of depression and its relationship with quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. The Brazilian Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;45:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Börsbo B, Peolsson M, Gerdle B. The complex interplay between pain intensity, depression, anxiety and catastrophising with respect to quality of life and disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1605–1613. doi: 10.1080/09638280903110079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lepine JP, Briley M. The epidemiology of pain in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:3–7. doi: 10.1002/hup.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aalto TJ, Malmivaara A, Kovacs F, Herno A, Alen M, Salmi L, et al. Preoperative predictors for postoperative clinical outcome in lumbar spinal stenosis: systematic review. Spine. 2006;31:E648–E663. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231727.88477.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Trief PM, Grant W, Fredrickson B. A prospective study of psychological predictors of lumbar surgery outcome. Spine. 2000;25:2616–2621. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walker MP, Harvey AG. Obligate symbiosis: sleep and affect. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:215–217. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Prather AA, Bogdan R, Hariri AR. Impact of sleep quality on amygdala reactivity, negative affect, and perceived stress. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:350–358. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828ef15b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Reich JW. Vulnerability to stress among women with chronic pain from fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:215–226. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2303_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zautra AJ, Johnson LM, Davis MC. Positive affect as a source of resilience for women in chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:212–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rutledge DN, Jones K, Jones CJ. Predicting high physical function in people with fibromyalgia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Morin CM, Gibson D, Wade J. Self-reported sleep and mood disturbance in chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:311–314. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pilowsky I, Crettenden I, Townley M. Sleep disturbance in pain clinic patients. Pain. 1985;23:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vitello MV, Moe KE, Larsen LH, Prinz PN. Age related sleep change: relationships of objective and subjective measures of sleep in healthy older men and women. Sleep Research. 1997;26:220. [Google Scholar]