Abstract

Heparanase, the sole heparan sulfate degrading endoglycosidase, regulates multiple biological activities that enhance tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Heparanase expression is enhanced in almost all cancers examined including various carcinomas, sarcomas and hematological malignancies. Numerous clinical association studies have consistently demonstrated that upregulation of heparanase expression correlates with increased tumor size, tumor angiogenesis, enhanced metastasis and poor prognosis. In contrast, knockdown of heparanase or treatments of tumor-bearing mice with heparanase-inhibiting compounds, markedly attenuate tumor progression further underscoring the potential of anti-heparanase therapy for multiple types of cancer. Heparanase neutralizing monoclonal antibodies block myeloma and lymphoma tumor growth and dissemination; this is attributable to a combined effect on the tumor cells and/or cells of the tumor microenvironment. In fact, much of the impact of heparanase on tumor progression is related to its function in mediating tumor-host crosstalk, priming the tumor microenvironment to better support tumor growth, metastasis and chemoresistance. The repertoire of the physiopathological activities of heparanase is expanding. Specifically, heparanase regulates gene expression, activates cells of the innate immune system, promotes the formation of exosomes and autophagosomes, and stimulates signal transduction pathways via enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities. These effects dynamically impact multiple regulatory pathways that together drive inflammatory responses, tumor survival, growth, dissemination and drug resistance; but in the same time, may fulfill some normal functions associated, for example, with vesicular traffic, lysosomal-based secretion, stress response, and heparan sulfate turnover. Heparanase is upregulated in response to chemotherapy in cancer patients and the surviving cells acquire chemoresistance, attributed, at least in part, to autophagy. Consequently, heparanase inhibitors used in tandem with chemotherapeutic drugs overcome initial chemoresistance, providing a strong rationale for applying anti-heparanase therapy in combination with conventional anti-cancer drugs. Heparin-like compounds that inhibit heparanase activity are being evaluated in clinical trials for various types of cancer. Heparanase neutralizing monoclonal antibodies are being evaluated in pre-clinical studies, and heparanase-inhibiting small molecules are being developed based on the recently resolved crystal structure of the heparanase protein. Collectively, the emerging premise is that heparanase expressed by tumor cells, innate immune cells, activated endothelial cells as well as other cells of the tumor microenvironment is a master regulator of the aggressive phenotype of cancer, an important contributor to the poor outcome of cancer patients and a prime target for therapy.

Keywords: Heparanase, tumorigenesis, inflammation, exosomes, autophagy, heparanase-inhibiting compounds, chemoresistance, clinical trials

1. Introduction/Preface

Heparanase is an endoglucuronidase that cleaves heparan sulfate (HS) thereby altering the structure and function of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) and contributing to tumor-mediated remodeling of both cell surfaces and the extracellular matrix (Bernfield et al., 1999; Hammond et al., 2014; Ilan et al., 2006; Iozzo and Sanderson, 2011; Rivara et al., 2016). These actions dynamically impact multiple regulatory pathways, most notably by accelerating cell invasion and augmenting the bioavailability of growth factors and cytokines bound to HS (Bernfield et al., 1999; Iozzo and Sanderson, 2011). Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, PCR and Western blot analyses demonstrate that heparanase expression is enhanced in almost all cancers examined including, for example, ovarian, pancreatic, gastric, renal, head & neck, colon, bladder, brain, prostate, breast and liver carcinomas (Hammond et al., 2014; Ilan et al., 2006; Rivara et al., 2016; Vlodavsky et al., 2012; Vreys and David, 2007; Zhang et al., 2011) as well as Ewing’s sarcoma (Cassinelli et al., 2016; Cassinelli et al., 2013; Shafat et al., 2011), multiple myeloma (Kelly et al., 2003; Ramani et al., 2013; Ritchie et al., 2011) and B-lymphomas (Weissmann et al., 2016). Numerous clinical association studies have consistently demonstrated that upregulation of heparanase expression correlates with increased tumor size, tumor angiogenesis, enhanced metastasis and poor prognosis (Hammond et al., 2014; Ilan et al., 2006; Rivara et al., 2016; Vlodavsky et al., 2012; Vreys and David, 2007).

A causal role of heparanase in tumor metastasis was demonstrated by the increased lung, liver and bone colonization of cancer cells following overexpression of the heparanase gene, and by a marked decrease in the metastatic potential of cells subjected to heparanase gene silencing. (Edovitsky et al., 2004; Lerner et al., 2008). The pro-tumorigenic effect of heparanase is attributed primarily to its HS degrading activity, facilitating cell invasion and ‘priming’ the tumor microenvironment. This notion is reinforced by in vivo studies indicating a marked inhibition of tumor growth in mice treated with heparanase-inhibiting heparin-like compounds (i.e., PI-88 = Mupafostat, Roneparstat = SST0001, Necuparanib = M402, PG545) which are currently being tested in clinical trials in cancer patients (Pala et al., 2016; Pisano et al., 2014; Rivara et al., 2016). A marked inhibition of tumor growth and dissemination was also exerted by heparanase neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in xenograft models of lymphoma and myeloma, emphasizing the significance of the enzymatic activity of heparanase in promoting tumorigenesis (Weissmann et al., 2016). In addition, both enzymatically active and inactive heparanase promotes signal transduction, including Akt, STAT, Src, Erk, HGF-, IGF- and EGF-receptor signaling (Barash et al., 2010; Ilan et al., 2006; Sanderson and Iozzo, 2012), highlighting the notion that non-enzymatic activities of heparanase play a significant role in heparanase-driven tumor progression (Fux et al., 2009a; Fux et al., 2009b). Moreover, heparanase induces the transcription of pro-angiogenic (i.e., VEGF-A, VEGF-C, COX-2, MMP-9), pro-thrombotic (i.e., tissue factor), pro-inflammatory (i.e., TNFα, IL-1, IL-6), pro-fibrotic (i.e., TGFβ), mitogenic (i.e., HGF), osteolyic (RANKL) and various other genes (Cohen-Kaplan et al., 2008b; Goodall et al., 2014; Ilan et al., 2006; Nadir et al., 2006; Parish et al., 2013; Purushothaman et al., 2008), thus significantly expanding its functional repertoire and mode of action in promoting aggressive tumor behavior (Barash et al., 2010; Ilan et al., 2006; Sanderson and Iozzo, 2012). Recent studies (detailed later in this review) emphasize the involvement of heparanase in autophagy (Shteingauz et al., 2015), exosome formation (Thompson et al., 2013), activation of the immune system (Goodall et al., 2014; Hermano et al., 2014) and chemoresistance (Ramani et al., 2015; Shteingauz et al., 2015), further highlighting its significance in mediating the crosstalk between tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment and in dictating the tumor response to stress, anti-cancer drugs and host factors. Thus, the published data supporting a role for heparanase in tumor progression is strong and well supported by in vitro and pre-clinical studies as well as by extensive research focusing on human cancer patients.

Several up-to-date reviews successfully describe basic and translational aspects related to the involvement of heparanase in cancer and inflammation (Hermano et al., 2012; Li and Vlodavsky, 2009; McKenzie, 2007; Vreys and David, 2007). The present review focuses primarily on recent new developments in the ‘heparanase field’, including its function in the tumor microenvironment, hematological malignancies, exosome formation, autophagy, chemoresistance, polarization of macrophages and toll-like receptor activation. Recently resolved structural features and translational aspects are also addressed.

1.1. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans

HSPG exert their multiple functional impacts via several distinct mechanisms that combine structural, biochemical and regulatory aspects. By interacting with other macromolecules such as laminin, fibronectin, and collagens I and IV, HSPG contribute to the structural integrity, self-assembly and insolubility of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and basement membrane, thus intimately modulating cell-ECM interactions (Bernfield et al., 1999; Timpl and Brown, 1996; Udo Hacker, 2005). HSPG also directly transfer information from the extracellular space to intracellular kinases and cytoskeletal elements and thus affect cell signaling, adhesion and motility (Aalkjaer and Boedtkjer, 2009). The biosynthesis of HS takes place in the Golgi apparatus and has been studied in great detail. Briefly, the polysaccharide chains are modified at various positions by sulfation, epimerization and N-acetylation, yielding clusters of sulfated disaccharides separated by low or non-sulfated regions (Iozzo and Sanderson, 2011; Lindahl and Li, 2009). The compositions of HS chains are adapted to their function and can differ between cells and tissues even when the core HSPG protein is the same (Wu et al., 2015). The modular nature and heterogeneity of HS structure provide interaction sites for a large number of different binding partners and is central to the proper biological function of HS (Bernfield et al., 1999; Lindahl and Li, 2009) in the control of normal and pathological processes, among which are morphogenesis, tissue repair, cancer metastasis, inflammation, vascularization, atherosclerosis, thrombosis, diabetic nephropathy and diabetes (Iozzo and Sanderson, 2011; Lindahl and Li, 2009). HSPGs not only provide a storage depot for heparin-binding molecules, but also decisively regulate their accessibility, function and mode of action. Cleavage of HSPGs would ultimately release these proteins and convert them into bioactive mediators, ensuring rapid tissue response to local or systemic cues. This function of HS provides the cell with a rapidly accessible reservoir, precluding the need for de novo synthesis when the requirement for a particular protein is increased (Vlodavsky et al., 1991; Vlodavsky et al., 2011).

1.2. Heparanase

Unlike the well resolved biosynthetic pathway of HS, the mode of HS breakdown is less characterized. While synthesis and modification of HS chains require the activity of an array of enzymes, degradation of mammalian HS is primarily carried out by one enzyme, heparanase (HPSE), which cleaves the HS side chains of HSPGs into fragments of 10–20 sugar units (Vlodavsky et al., 1999). Enzymatic activity capable of cleaving glucuronidic linkages and converting macromolecular heparin to physiologically active fragments was first identified by Ogren and Lindahl (Ogren and Lindahl, 1975). Subsequent studies revealed that the same endo-β-D-glucuronidase (heparanase) is critically involved in various pathologies such as cancer (Arvatz et al., 2011b; Ilan et al., 2006; Parish et al., 2001; Vlodavsky et al., 2011; Vlodavsky and Friedmann, 2001), inflammation (Lerner et al., 2011; Li and Vlodavsky, 2009), thrombosis (Baker et al., 2012; Nadir et al., 2010), atherosclerosis (Blich et al., 2012; Osterholm et al., 2012; Planer et al., 2011) and kidney dysfunction (Gil, 2011; van den Hoven et al., 2006). As a direct result of these studies, heparanase was advanced from being an obscure enzyme with a poorly understood function to a highly promising drug target, offering new treatment strategies for various cancers and other diseases.

Heparanase is initially translated as a preproenzyme containing a signal sequence spanning Met1–Ala35. Cleavage of this signal sequence by signal peptidase yields an inactive 65-kDa pro-heparanase, which must undergo further processing for activity. Proteolytic removal by cathepsin L (Abboud-Jarrous et al., 2008) of a linker spanning Ser110–Gln157 liberates an N-terminal 8-kDa subunit and a C-terminal 50-kDa subunit, which remain associated as a noncovalent heterodimer in mature active heparanase (Levy-Adam et al., 2003). Heparanase present in late endosomes and lysosomes plays an essential housekeeping role in catabolic processing of internalized HSPGs (Escobar Galvis et al., 2007a), and, as discussed below, in autophagy (Shteingauz et al., 2015) and exosome formation (Thompson et al., 2013). Importantly, heparanase can be trafficked to the cell surface or released into the ECM, where it affects breakdown of extracellular pools of HS (Nadav et al., 2002). Heparanase-mediated breakdown of HS in the ECM has several effects on the behavior of nearby cells. Weakening of structural HS networks in the ECM directly facilitates cell motility and invasion into surrounding tissues (Sasaki et al., 2004). Latent pools of growth factors stored by HS are released upon breakdown by heparanase and subsequently promote increased cell proliferation, motility and angiogenesis (Elkin et al., 2001; Vlodavsky et al., 1991). HS fragments generated by heparanase activity can also activate downstream signaling cascades (Goodall et al., 2014). Whereas controlled heparanase activity plays an important part in physiological processing of the ECM, tissue repair (Zcharia et al., 2005b), hair follicle growth (Zcharia et al., 2005a) and immune surveillance, aberrant heparanase expression is associated with inflammation and cancer, strongly correlating with metastasis and worsened clinical prognoses (Hammond et al., 2014; Ilan et al., 2006; Rivara et al., 2016; Vlodavsky et al., 2012). Only one gene with heparanase catalytic activity has been identified in mammals, suggesting that loss of heparanase activity may not easily be compensated for by the cell. Accordingly, as discussed below, heparanase inhibition has attracted intense interest as an anticancer strategy and oligosaccharide-like HS mimetics are being tested in clinical trials for various types of cancer (Hammond et al., 2014; Pisano et al., 2014; Rivara et al., 2016; Vlodavsky et al., 2012).

Heparanase is a member of the glycoside hydrolase 79 (GH79) family of carbohydrate-processing enzymes (Hulett et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2015). It catalyzes hydrolysis of internal GlcUA (β1→4) GlcNS linkages in HS, with net retention of anomeric configuration (Wilson et al., 2014). Heparanase-mediated breakdown of HS is not indiscriminate but instead is restricted to a small subset of GlcUAs, thus reflecting a requirement for specific N- and O-sulfation patterns on neighboring sugars (Okada et al., 2002; Peterson and Liu, 2012; Pikas et al., 1998). The GH79 family of carbohydrate-processing enzymes belongs to the larger GH-A clan, which is characterized by a (β/α)8 domain containing the catalytic site (Cantarel et al., 2009). The crystal structure of human heparanase has been recently resolved, revealing how an endo-acting binding cleft is exposed by proteolytic activation of latent pro-heparanase (Wu et al., 2015). A cleft spanning ~10 Å in the (β/α)8 domain of the apo-enzyme was identified, suggesting that the HS-binding site is contained within this part of the enzyme (Wu et al., 2015). The cleft contained residues Glu343 and Glu225, which have been identified as the catalytic nucleophile and acid-base of heparanase (Hulett et al., 2000) required for retaining the catalytic mechanism (Davies and Henrissat, 1995). In accordance with the negatively charged nature of its HS substrate, the heparanase binding cleft is lined by basic side chains contributed by Arg35, Lys158, Lys159, Lys161, Lys231, Arg272, Arg273 and Arg303 (Wu et al., 2015). The positioning of the 8-kDa-subunit C terminus and 50-kDa-subunit N terminus clearly indicates that the excised Ser110–Gln157 linker of pro-heparanase should lie very near or even within the active site cleft of the (β/α)8 domain (Abboud-Jarrous et al., 2008; Abboud-Jarrous et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2015). This positioning would hinder incoming HS substrates and is consistent with a previously proposed steric-block mechanism for pro-heparanase inactivation by its own linker (Abboud-Jarrous et al., 2008; Abboud-Jarrous et al., 2005; Nardella et al., 2004). A single-chain constitutively active heparanase was obtained by connecting the 8 and 50 kDa subunits with a spacer of three glycine-serine pairs. This preparation (HepGS3) is comparable to the processed, heterodimeric enzyme with regard to specific activity, profile of hydrolysis products, and inhibition by heparin (Nardella et al., 2004). Our own crystal structure of the HepGS3 protein (Livnah, Golan, et al., unpublished results) revealed structural features (i.e., TIM-barrel domain that contains the two catalytic glutamic acids and two heparin-binding domains, attached to a β-sandwich C-terminal domain) (Fig. 1) identical to the recently resolved crystal structure of the native enzyme (Wu et al., 2015). The newly resolved 3D structure of heparanase and its interaction with HS substrates provides a long-anticipated structural rationale that ties together the results of numerous biochemical studies on the HS sulfation patterns required for heparanase cleavage (Peterson and Liu, 2010; Pikas et al., 1998). The crystal structure confirmed that sulfation is key for heparanase interaction with HS and that the recognized cleavage site is a trisaccharide accommodated in the heparanase binding cleft. Structurally, −2 N-sulfate and +1 6O-sulfate appear to be the main determinants for recognition, because these directly contact the enzyme through hydrogen-bonding networks (Wu et al., 2015).

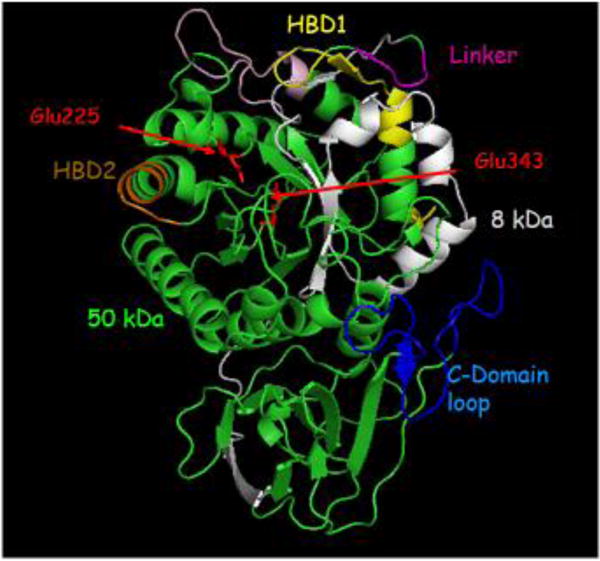

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of heparanase. Heparanase is composed of a TIM-barrel fold which contains the active site of the enzyme and a C-terminus domain required for secretion and signaling function of the protein. Heparanase has a catalytic mechanism which includes a putative proton donor at Glu225 and a nucleophile at Glu343 (red) as well as the heparin/heparan sulfate binding domains (HBD1 = Lys158-Asp171 & HBD2 = Gln270-Lys280; yellow and brown, respectively) that are located in close proximity to the active site micro-pocket fold. The C-domain is comprised of 8 β-strands arranged in two sheets, as well as a flexible, unstructured loop that lies in-between (blue). Notably, the 8 kDa subunit (gray) enfolds the 50 kDa subunit (green), contributing β/α/β unit to the TIM-barrel fold and, moreover, one of the 8 β strands that comprise the C-domain.

2. Heparanase and the tumor microenvironment

2.1. Impact of host heparanase on tissue susceptibility to carcinogenesis and tumor initiation

Compelling evidence tie heparanase with human cancer, but the timing of its induction and the significance of heparanase in the early phases of tumor initiation and development were not elucidated. To address this issue, we have utilized non-transformed human mammary epithelial cell line (MCF10A). Ectopic overexpression of heparanase resulted in expanded and disorganized acinar structures coincident with increased cell proliferation (Boyango et al., 2014). These features were far more dramatic when heparanase was overexpressed in MCF10AT1 cells that acquired the ability for xenograft growth after transfection with aberrant T24 Ha-Ras. Importantly, unlike the parental cells, xenograft lesions formed by heparanase overexpressing MCF10AT1 cells, were diagnosed as invasive carcinoma, indicating that heparanase cooperates with Ras to promote mammary tumor progression (Boyango et al., 2014). In subsequent studies, we exposed heparanase overexpressing transgenic (Hpa-Tg) mice and wt mice to two-steps DMBA/TPA skin carcinogenesis because more than 90% of skin cancer initiated by DMBA carries Ha-Ras activating mutations (Schwarz et al., 2013). In this 2-stage carcinogenesis model, DMBA induces mutations in dermal epithelium at an early stage, while TPA elicits an inflammatory response that drives further transformation, resulting in papilloma development. We found the Hpa-Tg model significantly more sensitive to carcinogen induced tumor formation. Indeed, the Hpa-Tg mice experienced 10-fold increase in tumor burden and rampant macrophage infiltration consistent with aggressive and invasive carcinomas. Strikingly, genetic ablation of heparanase resulted in a dramatic attenuation of tumorigenesis upon carcinogen exposure. Pharmacological inhibition of heparanase with the heparanase-inhibiting compound PG545 (Dredge et al., 2011) potently inhibited tumor establishment and the invasion of macrophages into the tumor per se, clearly depicting a critical role of heparanase in skin tumorigenesis (Boyango et al., 2014). Mechanistically, heparanase and Ras cooperatively promoted Met phosphorylation and the activation of various downstream oncogenic relays, such as Erk, Src, and Akt. Concurrent with increased Akt activation, FOXO1 was sequestered within the cytosol upon heparanase expression. However, inhibition with PG545 attenuated signaling and permitted nuclear occupancy of FOXO1 concomitant with a substantial decrease in phosphorylated Akt. These results uncover a critical role of heparanase and Ras in promoting early phases of tumorigenesis, indicating that pharmacological intervention targeting the enzymatic and signaling activities of heparanase may provide a valid avenue for combatting initial tumor development (Boyango et al., 2014).

2.2. Heparanase in hematological malignancies

The vast majority of studies on the mode of heparanase action and its impact on cancer progression focused on solid tumors (Arvatz et al., 2011b; Hammond et al., 2014; Ilan et al., 2006; Rivara et al., 2016). With the exception of multiple myeloma that exemplify a tumor that closely depends on the tumor microenvironment (Sanderson and Yang, 2008; Ramani et al., 2013), little is known about the involvement of heparanase in hematological malignancies. Recent studies on myeloma (Ramani et al., 2016; Ramani et al., 2015) and lymphomas (Weissmann et al., 2016) contribute to our basic understanding of the multifaceted nature of heparanase functions in cancer and in particular its pronounced impact on the cross talk between the tumor and the tumor microenvironment.

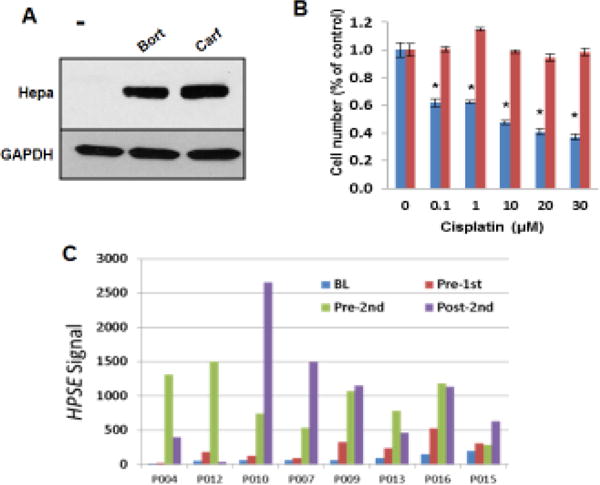

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most prevalent hematologic malignancy in the United States (Vincent Rajkumar, 2014). The emergence of novel, targeted therapeutics (e.g., bortezomib, thalidomide) has greatly improved survival rates in patients with myeloma (Laubach et al., 2014); however, there is still an unmet need in identifying and developing therapies designed to further prevent the progression of this disease without sacrificing patient quality of life. Recognition that the myeloma tumor microenvironment helps drive the aggressive nature of myeloma has led to new strategies for attacking the tumor microenvironment (Meads et al., 2008). Heparanase has been shown to promote an aggressive malignant phenotype, in part by synergizing with syndecan-1 (CD138) to create a niche within the bone marrow microenvironment further driving myeloma growth and dissemination (Iozzo and Sanderson, 2011; Ramani et al., 2013; Sanderson and Iozzo, 2012). Moreover, active heparanase can be detected in the bone marrow of most myeloma patients and the presence of high levels of this enzyme correlates with enhanced angiogenic activity, an important promoter of myeloma growth and progression (Kelly et al., 2003). Many of the pro-tumorigenic effects of heparanase in myeloma have been shown to rely upon increased expression and shedding of syndecan-1 (Ramani et al., 2013). This proteoglycan is expressed on most myeloma tumor cells and is a critical determinant of myeloma cell survival and growth (Beauvais et al., 2016). Heparanase enhances syndecan-1 shedding by up-regulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) that are recognized as syndecan sheddases (Purushothaman et al., 2008; Ramani et al., 2016). Heparanase-mediated shortening of HS chains on syndecan-1 also contributes to shedding, presumably by providing increased access of sheddases to the syndecan-1 core protein (Ramani et al., 2012). Importantly, heparanase-induced shedding of syndecan-1 was recently shown to couple VEGF receptor-2 with α4β1 integrin on both myeloma and endothelial cells. This receptor coupling led to activation of VEGF receptor-2 signaling that promoted myeloma cell invasion and endothelial tube formation (Jung et al., 2016). In addition, heparanase enhances the expression of HGF that can associate with shed syndecan-1 and facilitate paracrine signaling via its high affinity receptor, c-Met (Ramani et al., 2011). This discovery reveals for the first time how via a single mechanism, heparanase can stimulate both tumor metastasis and angiogenesis. It was further demonstrated that heparanase stimulates expression of VEGF, MMP-9 and RANKL, it promotes ERK signaling and represses expression of CXCL10 (Barash et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2010). Through these actions, heparanase dynamically impacts multiple regulatory pathways within the tumor microenvironment that together drive myeloma survival, growth, dissemination and osteolysis. Moreover, heparanase plays a role in modulating the sensitivity of myeloma cells to therapy. Increased expression and secretion of heparanase was detected in myeloma cells following treatment with bortezomib or melphalan and high expression of heparanase by these cells rendered them less susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of bortezomib or melphalan (Ramani et al., 2015). These data are clinically relevant as they are consistent with our finding that heparanase gene expression increases dramatically in myeloma patients following chemotherapy (Ramani et al., 2015). Moreover, heparanase expression within the bone marrow microenvironment is associated with shorter event-free survival of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated with high dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation (Mahtouk et al., 2007). Together, these findings imply that heparanase is a desirable and druggable therapeutic target whose inhibition will disrupt the myeloma microenvironment and diminish tumor growth and chemoresistance, while causing minimal side effects in patients. These results prompted a First in Man, multicenter phase I clinical study, currently ongoing in advanced heavily pre-treated refractory myeloma patients who have exhausted currently available lines of therapy (Rivara et al., 2016). The drug of choice is Roneparstat (SST0001), a potent inhibitor of heparanase enzyme activity (IC50~3 nM). It consists of a chemically modified heparin (ROH = reduced oxidized N-acetylated heparin) that is non-anticoagulant and is not degraded by the enzyme (Naggi et al., 2005). We have extensively studied Roneparstat in several models where human myeloma tumor cells were injected either subcutaneously, into fragments of human fetal bone implanted in mice (SCID-hu), or intravenously into the mouse tail vein. Roneparstat significantly inhibited growth, angiogenesis and bone metastasis of myeloma tumors in these models (Ritchie et al., 2011). Moreover in a model of dexamethasone resistant MM, the combination of Roneparstat with dexamethasone inhibited tumor growth. Consistent with the compound’s ability to inhibit heparanase activity, analysis of subcutaneous tumors from animals treated with Roneparstat revealed that the level of VEGF, HGF and MMP-9 were dramatically reduced and angiogenesis was repressed compared to animals treated with vehicle (Ritchie et al., 2011). When human myeloma cells expressing a high level of heparanase were injected intravenously, they home to and grew almost exclusively, in bone. In this model, Roneparstat monotherapy did not significantly inhibit tumor growth; however, it was highly effective when used in combination with bortezomib or melphalan (Ramani et al., 2015). The ability of Roneparstat to dramatically reduce tumor growth in bone when used in combination with either bortezomib or melphalan indicates that blocking heparanase diminishes drug resistance in myeloma (Ramani et al., 2015).

2.3. Heparanase enhances myeloma progression via CXCL10 down regulation

Applying an inducible model system we have demonstrated that heparanase induction markedly promotes tumor development by CAG myeloma, in agreement with the decisive role of heparanase in myeloma progression (Ramani et al., 2013; Ritchie et al., 2011). Utilizing gene array methodology we found that heparanase induction associates with CXCL10 down-regulation (Barash et al., 2014). Moreover, heparanase gene silencing resulted in elevation of CXCL10 transcription, collectively implying that heparanase levels inversely associate with CXCL10 expression. CXCL10 is therefore a member of a growing list of genes (i.e., VEGF, VEGF-C, TF, RANKL, HGF, and MMP9) regulated by heparanase and associated with tumorigenesis. A novel set of genes under heparanase regulation has been characterized in T cells (He et al., 2012). In this context, nuclear heparanase was shown to regulate the transcription of a cohort of inducible immune response genes by controlling histone H3 methylation (He et al., 2012), further expanding the transcriptional potential of heparanase (Parish et al., 2013).

Importantly, CXCL10 gene silencing resulted in tumor xenografts that were bigger than control myeloma tumors, while overexpression of CXCL10 or its injection into tumor bearing mice resulted in a marked decrease in tumor development, clearly depicting anti-cancer properties of CXCL10 in myeloma. Taken together, we identified a novel molecular mechanism that underlines the pro-tumorigenic function of heparanase in myeloma and involves down regulation of CXCL10. This chemokine appears to operate in three independent manners to suppress myeloma progression, directly attenuating myeloma cell proliferation; attenuating endothelial cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis; and chemoattracting anti-tumor immune cells. Hence, CXCL10 can be regarded as a tumor suppressor in this malignancy. Our results indicate that CXCL10 and especially the CXCL10-Ig fusion protein, may be applied as a novel therapeutic modality in myeloma (Barash et al., 2014).

2.4. Heparanase-neutralizing antibodies attenuate lymphoma and myeloma tumor growth and metastasis by targeting heparanase in the tumor microenvironment

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of cancers that arise from developing lymphocytes and produce tumors predominantly in lymphoid structures (i.e., bone marrow) but also in extra-nodal tissues. Collectively, lymphomas constitute the fifth most common cancer in North America, with more than 90% of the patients being affected by lymphomas of B cell origin (Scott and Gascoyne, 2014). Despite overall improvements in outcomes of lymphoma, approximately 30–40% of patients have disease that is either refractory or relapses after standard therapy (Ansell, 2015). The microenvironment of B cell lymphomas contains variable numbers of immune cells (i.e., T-cells, macrophages, neutrophils), stromal cells (i.e., fibroblasts), and endothelial cells (Blonska et al., 2015; Scott and Gascoyne, 2014; Shain et al., 2015), many of which have been reported to express heparanase (Matzner et al., 1985; Vlodavsky et al., 1992). A complex cross-talk between lymphoma cells and their microenvironment is bidirectional and multiple secreted factors and cell surface molecules contribute to the activation of signaling pathways in both the lymphoma and stromal cells (Blonska et al., 2015), many of which are targets for the development of lymphoma therapeutics (Mehta-Shah and Younes, 2015). In a recent study, we provided evidence that heparanase is expressed by B-lymphomas, and that heparanase inhibitors restrain tumor growth. Furthermore, we describe the development of novel heparanase-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that attenuate lymphoma growth by targeting heparanase in the tumor microenvironment (Weissmann et al., 2016). Our results with the newly developed mAbs are described below, further highlighting the potential of heparanase as a valid target for drug development.

Four carbohydrate-based heparanase inhibitors have reached clinical trials (Pala et al., 2016; Pisano et al., 2014; Rivara et al., 2016). These compounds apparently work by binding to the heparin/HS-substrate binding domain of the enzyme, thus blocking its accessibility to natural HS substrates. Owing to their heparin-based nature, these compounds can bind, in addition, many heparin-binding proteins in vivo leaving open the question as to how much of their anti-tumor effect is due specifically to blocking heparanase activity. Monoclonal antibodies against cancer-related targets have met with considerable success due to their specificity and long half-life in humans, yet none have been tested against heparanase in preclinical cancer models towards further clinical development. We have identified three potential heparin-binding domains of heparanase (Levy-Adam et al., 2005). Particular attention was given to the Lys158-Asp171 heparin binding domain (designated HBD1) since a peptide (termed KKDC) corresponding to this sequence physically interacts with heparin and HS, with high affinity, and inhibits heparanase enzymatic activity (Levy-Adam et al., 2005). We have followed this rationale and generated a panel of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) attempting to target the interaction of heparanase with its HS substrate. We have selected two mAbs (9E8, H1023) that neutralize heparanase enzymatic activity (Weissmann et al., 2016) and demonstrated that both antibodies substantially decreased the cellular uptake of latent heparanase, a HS-dependent mechanism that limits extracellular retention of the enzyme and enables intracellular processing of the latent enzyme into its active form (Gingis-Velitski et al., 2004b; Ilan et al., 2006). Thus, the newly generated antibodies not only neutralize the enzyme extracellularly, but also diminish uptake and accumulation of heparanase inside the cell (Fig. 2) (Weissmann et al., 2016).

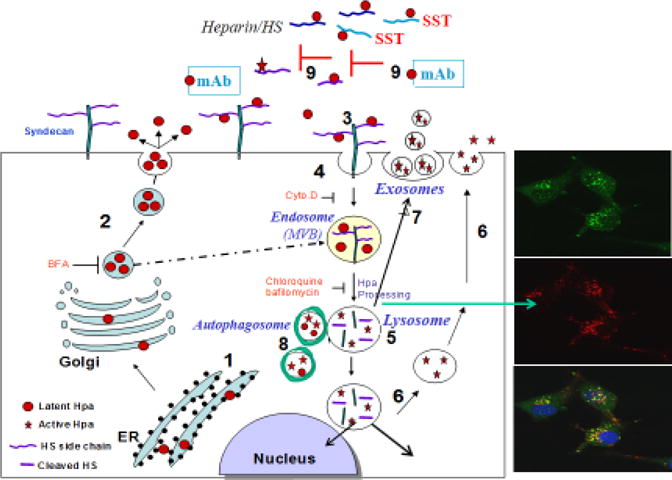

Figure 2.

Schematic model of heparanase trafficking. Pre-pro-heparanase is first targeted to the ER lumen via its signal peptide (1). The 65 kDa pro-heparanase is then shuttled to the Golgi apparatus, and is subsequently secreted via vesicles that bud from the Golgi (2), a step that is inhibited by Brefeldin A (BFA). Once secreted, heparanase rapidly interacts with cell membrane HSPGs (i.e., syndecan family members) (3), followed by a rapid endocytosis of the heparanase-syndecan complex that accumulates in late endosomes (4). These steps are inhibited by heparin, glycol-split heparin (SST) and heparanase neutralizing mAb (9), all of which bind to the heparin/HS binding domains of the enzyme, resulting in extracellular accumulation of the latent enzyme and depletion of the intracellular content of the active 50 + 8 kDa enzyme. Fusion of endosomes to lysosomes results in heparanase processing and activation (primarily by cathepsin L) (5) that, in turn, participates in the turnover of HS side chains in the lysosome. Heparanase processing is inhibited by chloroquine and Bafilomycin A, inhibitors of lysosomal proteinases via alkalinization of the lysosomal pH. Typically, heparanase appears in perinuclear lysosomal vesicles (right panels: heparanase-green; lysotracker-red). Lysosomal heparanase may translocate to the nucleus, where it affects gene transcription, and/or can get secreted via secretory lysosomes (6) and exosomes (7). Heparanase promotes the formation of exosomes and autophagosomes (8), resulting in accelerated tumor growth and chemoresistance.

Both the 9E8 (IgM) and H1023 (IgG) mAbs markedly inhibited cell invasion and tumor metastasis, the hallmarks of heparanase function. Moreover, both mAbs inhibited the spontaneous metastasis of ESb mouse lymphoma cells from the subcutaneous primary lesion to the liver (Weissmann et al., 2016). Decreased blood vessel density in Raji Burkitt’s lymphoma treated with mAb 9E8 and H1023 (Weissmann et al., 2016) critically stamps the pro-angiogenic capacity of heparanase (Ilan et al., 2006). This is likely due to reduced release by heparanase of angiogenic-promoting factors sequestered in the bone marrow ECM (Elkin et al., 2001). Importantly, treatment with mAb 9E8 or mAb H1023, as a single agent, attenuated the growth of CAG myeloma and Raji lymphoma tumors, and even greater inhibition was observed when combining the two mAbs together (Fig. 3) (Weissmann et al., 2016), in agreement with the notion that combining two different mAbs increases the inhibitory outcome. Not surprising, mAb 9E8 and H1023 are not cytotoxic to lymphoma or myeloma cells, implying that the mAbs do not exert a direct effect on tumor cells but rather affect the tumor microenvironment. This is best demonstrated with Raji Burkitt’s lymphoma cells that lack intrinsic heparanase activity due to gene methylation (Shteper et al., 2003), yet tumor xenografts produced by the same cells exhibit typical heparanase activity (Fig. 3) (Weissmann et al., 2016). Thus, the ability of mAbs 9E8 and H1023 to attenuate the growth of these tumors is due primarily to neutralization of heparanase contributed by the tumor microenvironment (Weissmann et al., 2016). This implies that the host contributes a significant amount of heparanase, and that inhibition of this fraction is sufficient to attenuate tumor growth. This notion was further supported by showing that mouse El-4 lymphoma cells developed larger (3.5-fold) tumor xenografts when transplanted in heparanase overexpressing transgenic (Hpa-tg) mice vs. wild type C57BL mice. In contrast, smaller (8.5-fold) tumors developed when the same cells were inoculated into heparanase knockout (Hpa-KO) mice vs. wild type mice, further implying that host heparanase plays a decisive role in tumor progression. The finding that EL4 lymphoma cells grew aggressively in Hpa-tg but not wt animals is particularly instructive because EL4 lymphoma cells lack heparanase expression, leaving only host cells to contribute heparanase. (Gutter-Kapon et al., unpublished data).

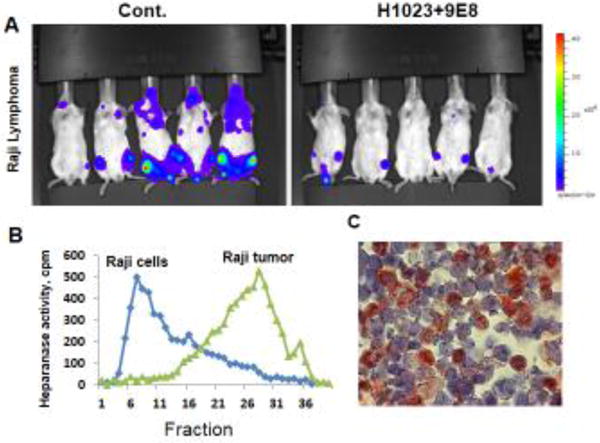

Figure 3.

Heparanase neutralizing mAbs attenuate tumor growth. NOD/SCID mice were inoculated (i.v.) with luciferase-labelled Raji-lymphoma cells (A). Mice were treated with mAb 9E8 and mAb H1023 (500 μg/mouse every other day) and tumor growth was evaluated by IVIS imaging. Notably, Raji cells lack heparanase activity (B, Raji cells) whereas tumors developed by Raji cells exhibit typical heparanase activity (B, Raji tumors, fraction 20–35). Bone marrow cells are positively stained for heparanase (C), suggesting that the neutralizing mAbs attenuate lymphoma growth by targeting heparanase activity contributed by the tumor microenvironment.

3. Heparanase in acute and chronic inflammation

HS is known to control inflammatory responses at multiple levels, including sequestration of cytokines/chemokines in the extracellular space, modulation of leukocyte interactions with endothelium and ECM, and initiation of innate immune responses through interactions with toll-like receptors 4 (TLR4) (Akbarshahi et al., 2011; Axelsson et al., 2012; Bode et al., 2012; Brunn et al., 2005; Gotte, 2003; Johnson et al., 2002; Parish, 2006; Wang et al., 2005). Thus, HS remodeling by heparanase may affect several aspects of inflammatory reactions, such as leukocyte recruitment, extravasation and migration towards inflammation sites; release of cytokines and chemokines anchored within the ECM or cell surfaces, as well as activation of innate immune cells (Goldberg et al., 2013; Li and Vlodavsky, 2009; Zhang et al., 2014). The link between inflammation and heparanase was first demonstrated more than two decades ago, prior to cloning of the heparanase gene, when HS-degrading activity was discovered in immunocytes (neutrophils, activated T-lymphocytes) and found to contribute to their ability to extravasate and accumulate in target organs (Lider et al., 1989; Lider et al., 1990; Matzner et al., 1985; Naparstek et al., 1984; Vlodavsky et al., 1992). In addition, non-enzymatic functions of the enzyme were found to promote pro-inflammatory cell adhesion and signal transduction (Riaz et al., 2013). Anti-inflammatory effects demonstrated for heparanase-inhibiting substances (i.e., heparin, synthetic heparin-mimicking compounds) in animal and clinical studies (Edovitsky et al., 2004; Floer et al., 2010; Goldberg et al., 2013; Hershkoviz et al., 1995; Parish et al., 1998; Young, 2008) further support the involvement of the enzyme in inflammatory reactions.

Heparanase expression is up-regulated in the colon of patients suffering from Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (Doviner et al., 2006; Lerner et al., 2011; Waterman et al., 2007), and in the synovial fluid and tissue of patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, but not in unaffected individuals (Li et al., 2008). Heparanase has also been implicated in the severity of atherosclerosis, as its expression is increased in vulnerable coronary plaques as opposed to stable plaques and controls (Blich et al., 2013).

Notably, heparanase gene silencing resulted in decreased delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction (Edovitsky et al., 2006), and heparanase knockout mice showed reduced airway and acute lung injury responses in models of allergy and sepsis (Poon et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2012). Furthermore, transgenic mice overexpressing heparanase are endowed with increased DTH (Edovitsky et al., 2006), colon (colitis) (Lerner et al., 2011), pancreas (unpublished data) and skin (psoriasis-like) (Lerner et al., 2014) inflammation, collectively implying that heparanase is an important player in the inflammatory reaction (Goldberg et al., 2013; Li and Vlodavsky, 2009; Zhang et al., 2014). With the accumulation of experimental data, a complex picture of the versatile role of heparanase in inflammation is evolving, whereby heparanase may act either in facilitating or limiting inflammatory responses, depending on the cellular/extracellular context. Below we discuss several emerging mechanistic concepts reflecting the involvement of heparanase in inflammatory reactions, primarily via modulating the activity of innate immune cells.

3.1. Neutrophils and sepsis

Cumulative evidence suggests that heparanase affects the activities of several types of innate immunocytes, including neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic and mast cells (Benhamron et al., 2006; Benhamron et al., 2012; Blich et al., 2013; Lerner et al., 2011; Massena et al., 2011; Schmidt et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011). Of those, neutrophils represent the important effectors in the acute inflammatory responses. The consequence of heparanase action on neutrophil behavior was highlighted in a study by Schmidt et al., focusing on enzymatic degradation of endothelial glycocalyx in sepsis-associated lung injury. Glycocalyx, the thin gel-like endothelial layer that coats the luminal surface of blood vessels, is composed of HS and other glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans and glycoproteins (Constantinescu et al., 2003; Weinbaum et al., 2007). It serves as a barrier to circulating cells and controls availability of endothelial surface adhesion molecules to circulating leukocytes (Constantinescu et al., 2003; Weinbaum et al., 2007). In the mouse model of sepsis-associated inflammatory lung disease, rapid induction of heparanase activity (through TNFα-dependent mechanism) was demonstrated in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (Schmidt et al., 2012). Heparanase induction was also found in biopsies of human inflammatory lung disease (Schmidt et al., 2012). Moreover, sepsis-associated loss of pulmonary glycocalyx and endothelial hyperpermeability were attenuated in heparanase-null mice and in mice treated with inhibitors of heparanase enzymatic activity (Schmidt et al., 2012). It was suggested that the lung microvasculature is masked by HS-rich glycocalyx that has to be removed by lung expressed heparanase in order for neutrophils to entrap in the pulmonary vasculature in response to LPS septic signals (Schmidt et al., 2012). Unlike this work, applying the same heparanase-null mice as well as ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 double knockout mice, we have demonstrated that lung entrapment of neutrophils in response to systemic LPS does not require either heparanase mediated degradation of the pulmonary HS rich glycocalyx or neutrophil recognition of vascular ICAM-1 and 2 (Petrovich et al., 2016). Thus, although lung endothelial heparanase may be triggered by LPS and other systemic inflammatory signals to unmask the pulmonary vasculature (Schmidt et al., 2012), it appears that this heparanase-dependent step is not a rate-limiting step in LPS-triggered neutrophil entrapment in the pulmonary vasculature. We therefore favor the possibility that septic conditions modeled by systemic LPS trigger a deformation of neutrophils by their cytoskeletal stiffening resulting in ICAM-, β2 integrin- and heparanase- independent mechanical entrapment inside the thin capillary vessels (Mizgerd et al., 1997; Petrovich et al., 2016; Worthen et al., 1989). Our results are consistent with a study by Morris et al., which has ruled out a role for lung heparanase in neutrophil infiltration to lungs exposed to intranasal LPS (Morris et al., 2015). Likewise, neutrophil emigration from blood to the inflamed skin or peritoneal cavity was shown to be heparanase independent (Stoler-Barak et al., 2015). We also found no role for T cell-based heparanase in effector T cell entrapment inside this vasculature although these T cells express high levels of the enzyme (Stoler-Barak et al., 2015). Overall, our results indicate that effector T cells use their constitutively adhesive LFA-1 to readily recognize pulmonary ICAM-1 and 2 independently of heparanase mediated glycocalyx degradation, probably because their large and stiff nucleus allows these cells to readily penetrate the thick glycocalyx barrier without HS degradation.

3.2. Heparanase is critical for neutrophil entry to lungs exposed to tobacco smoke

Given that heparanase activity is implicated in multiple chronic inflammatory processes (Hermano et al., 2012; Lerner et al., 2011; Naggi et al., 2005), we searched for a potential role of the enzyme in neutrophil emigration to lungs subjected to a prolonged smoke exposure. A daily exposure of wt mice to high levels of tobacco smoke for 2 weeks resulted in a significant infiltration of neutrophils to the lung parenchyma and a small fraction of these neutrophils also penetrated the bronchoalveolar space (Petrovich et al., 2016). Strikingly, heparanase deficiency resulted in dramatically reduced numbers of neutrophils entrapped either in the lung or recovered in the BAL (Petrovich et al., 2016). The contributions of heparanase to neutrophil migration and retention in smoke exposed lungs are probably more complex than those of LPS induced neutrophil migration to lungs. For example, in a model of ear inflammation, endothelial heparanase was suggested to remodel the HS-rich vascular basement membrane (Benhamron et al., 2006). A similar function may be mediated by pulmonary heparanase during prolonged exposure to smoke and potentially other air irritants. Moreover, lung heparanase may be also involved in transcriptional regulation of neutrophil attracting chemokines, as evident from the reduced levels of smoke triggered CXCL5 transcription detected in heparanase null lungs. These results collectively suggest a role of lung heparanase in neutrophil recruitment to smoke exposed lungs, which could be partially due to aberrant transcription of neutrophil attracting chemokines by smoke inflamed lungs (Petrovich et al., 2016).

3.3. Mode of action

In some experimental settings heparanase was noted to inhibit, rather than promote, inflammation. Thus, constitutive overexpression of heparanase in Hpa-tg mice attenuated intraluminal crawling of neutrophils in the cremaster muscle microvessels toward an extravascular chemokine source, reportedly due to reduction in endothelial surface HS chain length and altered ability of truncated HS to serve as a ligand for chemokines (Massena et al., 2011). Likewise, exploring acute inflammatory phenotypes of Hpa-tg mice in models of inflammatory (Li et al., 2012b) and neuroinflammation (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2012b) revealed that neutrophil recruitment and activation were attenuated in the presence of constitutively increased levels of heparanase in Hpa-tg mice. This was reportedly due to cleavage of HS on the endothelial cell surface and the resulting disruption of chemokine gradient(s) which is critical for directional migration of immune cells and infection resolution (Massena et al., 2011). Consequently, crawling of neutrophils toward chemokine-releasing gel was impaired in Hpa-tg mice; instead, Hpa-tg neutrophils exhibited random crawling, ultimately leading to severely reduced ability to clear bacterial infection (Massena et al., 2011). A similar situation may occur in pleural empyema, an inflammatory condition that progresses from acute to chronic, life-threatening phase. Heparanase expression and activity were markedly increased in patients with chronic vs. acute pleural empyema and in a mouse model of empyema (Lapidot et al., 2015). Unexpectedly, however, Hpa-tg mice exposed to empyema exhibited prolonged survival, supporting the occurrence of a protective anti-inflammatory mechanism in this model (Lapidot et al., 2015), likely due to impaired chemokine gradient and the attenuated recruitment of neutrophils.

In light of the reported anti-inflammatory effects of heparin (Young, 2008), increased levels of highly sulfated, “heparin-resembling” HS fragments, which are constantly present in Hpa-tg, as compared to wt mice (Escobar Galvis et al., 2007b; Li et al., 2005), may offer an explanation for the inhibitory effects of continuous heparanase overexpression on neutrophils in these settings (Li et al., 2012a; Zhang et al., 2012a). In addition, it was noted that the thickness of the glycocalyx varies greatly between microvessels from different tissues: it is almost 3 times thinner in cremaster (systemic) microvessels endothelium than in pulmonary endothelium (Schmidt et al., 2012). Thus, the overall effect of heparanase on neutrophil behavior may depend on the proportional contribution of glycocalyx removal (which is expected to facilitate neutrophil access to the blood vessel wall (Schmidt et al., 2012) versus the disturbance of chemokine gradients at the endothelial cell surface (which attenuates neutrophil recruitment (Li et al., 2012a; Massena et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012b). Additionally, effects of heparanase on acute inflammatory reactions in different organ/tissue settings may reflect different roles of the enzyme through distinctive phases of the inflammatory cascade or may be a consequence of tissue-specific patterns reported for HS (Allen et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2007; Ledin et al., 2004). Altogether, depending on the context and experimental system, overexpression of heparanase may exert opposing effect on acute inflammatory responses. Taking into account the complex nature of inflammation and the multifaceted action of heparanase, the end result depends on the intricate balance between its pro-inflammatory (i.e., tissue damage, infiltration of leukocytes) and anti-inflammatory (i.e., disruption of chemokine gradients) effects. The above examples illustrate the complexity and duality of heparanase function in inflammatory conditions. Regardless, increased heparanase levels in the course of Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis (Waterman et al., 2007), empyema (Lapidot et al., 2015), psoriasis (Lerner et al., 2014), pancreatitis (Koliopanos et al., 2001) and arthritis (Li et al., 2008), and the reduced severity of sepsis (Schmidt et al., 2012) and diabetic nephropathy (Gil et al., 2012) in heparanase knockout mice implies that heparanase inhibitors may prove beneficial in some of these pathological conditions. The ability of heparanase inhibitors (i.e., PG545, SST0001, PI-88) to restrain experimental acute pancreatitis (Khamaysi et al., unpublished data), diabetic nephropathy (Gil et al., 2012), and autoimmune type 1 diabetes (Parish et al., 2013; Ziolkowski et al., 2012) provides hope that these and other heparanase inhibitors will restrain the expanding variety of inflammation-based disorders.

3.4. Heparanase effects on macrophages in chronic inflammation

When acute inflammation is not properly resolved, the composition of the infiltrating leukocytes changes from neutrophils to macrophages, dominant cellular players in chronic inflammation. Heparanase ability to modulate macrophage responses was highlighted in studies focusing on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, the two chronic disorders collectively known as IBD, result from inappropriate persistent activation of the mucosal immunity by normal gut flora in genetically susceptible individuals (Xavier and Podolsky, 2007). In patients with IBD, an equilibrium between the immune response to pathogens and tolerance to the normal flora becomes unbalanced, leading to the uncontrolled uptake of proinflammatory substances (i.e., bacteria, bacterial products) from the gut lumen and triggering immune activation, cytokine release, and dysfunction of the epithelial barrier (Clayburgh et al., 2004; Xavier and Podolsky, 2007). Given the important role of HS in maintaining the integrity of the gut wall (Belmiro et al., 2005; Bode et al., 2008), enzymatic degradation of HS is thought to significantly affect colon permeability and inflammatory reactions. Analysis of glycosaminoglycan content in normal colonic tissue and colons of IBD patients revealed loss of HS from the subepithelial BM and from the vascular endothelium in the submucosa (Belmiro et al., 2005; Day and Forbes, 1999; Murch et al., 1993). In agreement, preferential expression of heparanase was reported in colonic epithelium of IBD patients during both acute and chronic phases of the disease (Lerner et al., 2011; Waterman et al., 2007). Of note, immunocytes in the involved areas exhibit little heparanase expression during all phases (Waterman et al., 2007). A similar temporo-spatial pattern of heparanase expression was observed in experimental dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced chronic colitis in mice (Lerner et al., 2011). It appears that in the setting of colitis, heparanase of epithelial origin modulates inflammatory phenotype of macrophages, preventing inflammation resolution and switching macrophage responses to chronic inflammation pattern (Lerner et al., 2011). In support of this notion, exacerbated chronic inflammatory phenotype and augmented recruitment and activation of macrophages were detected in colonic mucosa of Hpa-tg mice following induction of DSS colitis (Lerner et al., 2011). Moreover, recombinant heparanase strongly augmented in vitro activation of macrophages, resulting in increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Blich et al., 2013; Goodall et al., 2014; Hermano et al., 2014; Lerner et al., 2011). Activated macrophages can in turn induce epithelial heparanase expression (via a TNFα-dependent mechanism) and post-translational processing of the pro-enzyme via increased secretion of cathepsin L (Lerner et al., 2011) (Fig. 4), fueling a self-sustaining inflammatory circuit which could partially explain the so called “multiplier” effect in IBD, in which small elevation in initiating inflammatory stimuli leads to a large increase in downstream cytokines. Notably, augmented macrophage activation in response to heparanase was also reported in a model of neointimal lesions following vascular injury (Baker et al., 2009) and in atherosclerotic plaque progression toward vulnerability (Blich et al., 2013), further supporting a role of the enzyme in modulating macrophage responses. Moreover, our studies on the involvement of heparanase in diabetic nephropathy indicate that activation of kidney-infiltrating macrophages may represent an important mechanism through which heparanase contributes to chronic low-grade inflammation and renal damage in diabetic kidney disease (Goldberg et al., 2014).

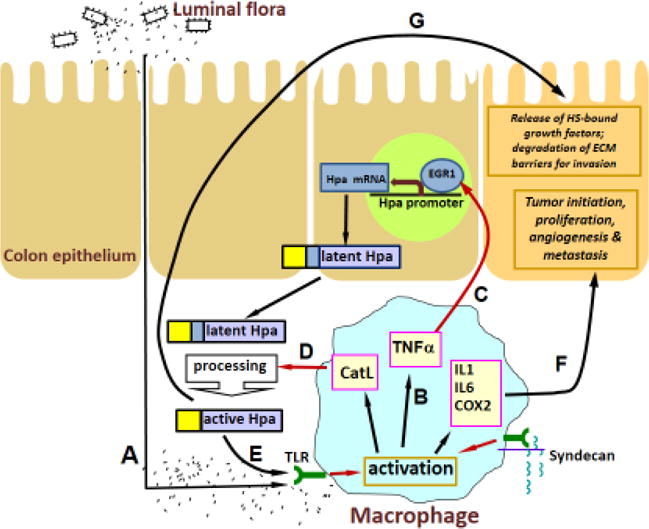

Figure 4.

A model of heparanase-driven vicious cycle that powers colitis and the associated tumorigenesis. Macrophages activated by excessive exposure to the luminal flora due to epithelial barrier dysfunction and activation of TLR4 (A) produce increased levels of TNF-α (B) and induce heparanase expression in the colon epithelium via EGR1 dependent mechanism (C). D. The secreted 65-kDa latent heparanase is processed into its enzymatically-active (8+50 kDa) form by cathepsin L (CatL), supplied by the activated macrophages, and in turn sensitizes macrophages to further activation by luminal flora (E), thus preventing inflammation resolution, switching macrophage responses to the chronic inflammation pattern and creating a tumor initiating inflammatory environment (F). In addition, heparanase promotes tumor take and progression via stimulation of angiogenesis, release of ECM-bound growth factors and bioactive HS fragments, and removal of extracellular barriers for invasion (G).

3.5. Heparanase in inflammation-associated cancer

Chronic inflammatory conditions present in the microenvironment of most tumors (Mantovani et al., 2008) contribute to cancer progression (Grivennikov et al., 2010; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011), among other mechanisms, through mobilization of tumor-supporting immunocytes (e.g., tumor associated macrophages, neutrophils) which supply bioactive molecules that foster survival, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Mantovani et al., 2008; Qian and Pollard, 2010). Moreover, in several anatomic sites chronic inflammation is crucially implicated in tumor initiation, producing a mutagenic environment through release of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species from infiltrating immune cells, generating cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and anti-apoptotic proteins and activating tumor stimulating signaling pathways (e.g., NF-kB, STAT3) (Grivennikov and Karin, 2010; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Mantovani et al., 2008; Qian and Pollard, 2010). Progression of Barrett’s esophagus to adenocarcinoma (Picardo et al., 2012); chronic gastritis to intestinal-type gastric carcinoma, chronic hepatitis C to hepatocellular carcinoma (Chiba et al., 2012); pancreatitis to pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Lowenfels et al., 1993) and colitis to colorectal cancer (Gupta et al., 2007) are well-known examples of inflammation-driven tumorigenesis. Remarkably, induction of heparanase prior to the appearance of malignancy was reported in essentially all of the above-mentioned inflammatory conditions, i.e., Barrett’s esophagus (Brun et al., 2009; Sonoda et al., 2010), hepatitis C infection (El-Assal et al., 2001), chronic pancreatitis (Koliopanos et al., 2001), Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis (Waterman et al., 2007 and Lerner et al., 2011). Given the causal role of heparanase in tumor progression in tissues in which cancer-related inflammation typically occurs [i.e., gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, liver (Brun et al., 2009; El-Assal et al., 2001; Hoffmann et al., 2008; Koliopanos et al., 2001; Naomoto et al., 2005; Nobuhisa et al., 2005; Sonoda et al., 2010; Xiong et al., 2012), it is conceivable that inflammation-induced heparanase may be involved in coupling inflammation and cancer. This notion is supported by a study utilizing a mouse model of colitis-associated colon carcinoma (Lerner et al., 2011), showing that heparanase promotes polarization of innate immunocytes toward pro-inflammatory and/or pro-tumorigenic phenotype (Fig. 4). By sustaining continuous activation of macrophages that supply cancer-promoting cytokines (i.e., TNFα, IL-1, IL-6), heparanase (produced primarily by inflamed epithelium and activated by cathepsin L contributed by tumor associated macrophages) (Fig. 4) participates in creating a tumorigenic microenvironment characterized by enhanced NFκB and STAT3 signaling, augmented levels of cyclooxygenase 2 and increased vascularization (Lerner et al., 2011).

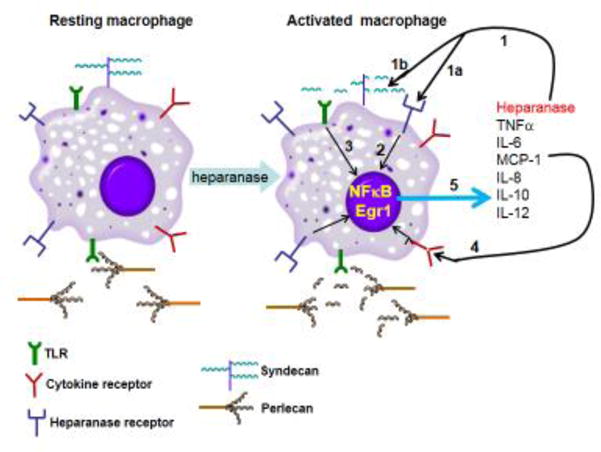

Blich et al., have reported that heparanase stimulates the release of cytokines from primary mouse peritoneal macrophages and the mouse macrophage cell line J774 (Blich et al., 2013). Similarly, Goodhall et al., showed that heparanase promotes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from both human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and TNFα) and mouse splenocytes (MCP-1, IL-6, TNFα), likely by generating soluble HS fragments that activate TLR-dependent pathway(s) (Goodall et al., 2014) (Fig. 5). This mechanism was supported by the significant inhibition of cytokine release upon inhibition of heparanase enzymatic activity and by showing that heparanase-induced cytokine release was dependent on MyD88, a key TLR adaptor molecule, and mediated in part through TLR-4 via the NF-κB pathway (Blich et al., 2013; Goodall et al., 2014). Notably, cytokine expression in response to heparanase is transcriptionally regulated, consistent with HS fragments acting through TLRs via NF-κB (Fig. 5). Indeed, heparanase-mediated cytokine release is reduced when cells are treated with the NF-κB inhibitor BAY117082 (Blich et al., 2013). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that resistin has been identified as a new interacting partner for heparanase (Novick et al., 2014). Resistin has been shown to bind and signal through TLR4, leading to an increase in the pro-inflammatory protein MCP-1 (Kopp et al., 2009). Together, these results identify a novel role for heparanase in the regulation of an inflammatory response that is distinct from the previously described physical breakdown of the ECM to promote efficient migration of leukocytes to sites of inflammation.

Figure 5.

Schematic model of the function of heparanase in activation of macrophages. Heparanase binds to a putative receptor that mediates its non-enzymatic signaling activity (1a). Heparanase also cleaves HS at the cell surface (syndecan) and ECM (perlecan) and releases HS fragments that then signal through MyD88-dependent tall-like receptors (1b) (e.g.,TLR4), leading to NF-κB cleavage and activation (3). An intriguing possibility is that intact extracellular HS inhibits TLR4 responses and macrophage activation, while its removal/degradation by heparanase relieves this inhibition, most likely by increasing accessibility of TLRs to their ligands. NF-κB upregulates the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokine, including: IL-8, IL-10, IL12, IL-6, TNF, IL-1β and MCP-1 (5). These cytokines promote (via cell surface receptors) inflammatory events and may also increase heparanase production via the Egr1 transcription factor. Altogether, these events contribute to a vicious cycle that induces inflammatory responses.

3.6. Involvement of heparanase in coupling aseptic inflammation and tumorigenesis

Pancreatic tumor microenvironment and in particular infiltrating inflammatory cells (largely macrophages), represents an important contributing factor to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) aggressiveness and resistance to treatment (Baumgart et al., 2013; Feig et al., 2012). We have highlighted a novel action of heparanase in coupling inflammation and cancer during PDAC progression (as a prototype of aseptic inflammation-associated tumor). We found that heparanase polarizes macrophages, stimulated by necrotic cells (which are abundantly present in both clinical and experimental PDAC (Hiraoka et al., 2010; Ijichi et al., 2011) toward tumor-promoting phenotype, characterized by augmented expression of several key cytokines driving pancreatic tumorigenesis. Utilizing a mouse model of heparanase-overexpressing pancreatic carcinoma, we demonstrated that the enzyme directs protumorigenic behavior of TAM. Overexpression of heparanase resulted in increased TAM infiltration. Moreover, well-recognized markers of protumorigenic macrophage population (i.e., MSR-2, CCL-2, IL-10, VEGF, IL-6) that are tightly implicated in the pathogenesis of PDAC (Jones et al., 2011; Lesina et al., 2011) were significantly upregulated in TAM isolated from heparanase-overexpressing mouse tumors (Hermano et al., 2014).

We hypothesized that heparanase facilitates tumor-promoting action of TAM activated by endogenous ligands originating in the PDAC microenvironment. In fact, several elements in the tumor microenvironment (e.g., ECM components, necrotic cell-derived substances) may affect macrophage behavior through TLR activation (Yu et al., 2013)). In particular, it is increasingly apparent that necrotic cancer cells may lead to more aggressive tumors because of the stimulatory role of necrosis-induced inflammation (Proskuryakov and Gabai, 2010). Importantly, treatment of necrotic cell-stimulated macrophages with active heparanase resulted in induction of key cytokines implicated in PDAC (including IL-6) and facilitated their ability to activate STAT3, a cornerstone of pancreatic carcinogenesis acting downstream IL-6 (Baumgart et al., 2013). Notably, activation of STAT3 was observed in experimental and clinical specimens of PDAC with increased heparanase levels (Hermano et al., 2014).

The exact mechanism of heparanase-mediated change in macrophage phenotype is not fully elucidated. One intriguing possibility is that intact extracellular HS inhibits TLR4 responses and macrophage activation, while its removal relieves this inhibition (Brunn et al., 2005), most likely by increasing accessibility of TLRs to their ligands. On the other hand, soluble HS fragments themselves were found to stimulate TLR (in particular TLR4) signaling in vitro (Brunn et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2010) and in pancreatic tissue in vivo (Yu et al., 2010). Importantly, heparanase releases bioactive HS degradation fragments from the ECM/cell surface (Elkin et al., 2001; Kato et al., 1998). While further investigation is warranted, our results reveal a novel role of heparanase in the molecular decision-making process that guides changes in the TAM phenotype during tumor development. Moreover, it implies that heparanase expression status may become highly relevant in defining target patient subgroup that is likely to benefit the most from treatment modalities that target TAM/IL-6 signaling, which are currently under intensive preclinical/clinical validation in PDAC and other tumor types (Fang and Declerck, 2013). Taken together, our findings describe a role of heparanase in powering cancer-related aseptic inflammation, highly relevant to the pathogenesis of PDAC and additional tumor types (Hermano et al., 2014). Heparanase inhibiting compounds and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies are expected to exert therapeutic benefits in both inflammation and malignancy by disrupting heparanase-driven heterotypic interactions between epithelial, endothelial, and immune cells.

4. Cellular uptake and trafficking of heparanase

4.1. Processing of heparanase is mediated by syndecan 1 cytoplasmic domain and involves syntenin and α-actinin

A number of studies have shown that secreted or exogenously added latent heparanase rapidly interacts with normal and tumor-derived cells, followed by internalization and processing into a highly active enzyme (Ben-Zaken et al., 2008; Gingis-Velitski et al., 2004a; Gingis-Velitski et al., 2004b; Nadav et al., 2002; Vreys et al., 2005; Zetser et al., 2004), collectively defined as heparanase uptake. Several approaches, including HS-deficient cells, addition of heparin or xylosides, and deletion of HS-binding domains of heparanase, provided compelling evidence for the involvement of HS in heparanase uptake (Gingis-Velitski et al., 2004b; Levy-Adam et al., 2005). Heparanase uptake is regarded a pre-requisite for the delivery of latent 65 kDa heparanase to lysosomes and its subsequent proteolytic processing and activation into 8 and 50 kDa protein subunits. Briefly, following uptake, heparanase was noted to reside primarily intracellularly within endocytic vesicles, assuming a polar, peri-nuclear localization and co-localizing with lysosomal markers (Goldshmidt et al., 2002; Nadav et al., 2002). Notably, heparanase processing was blocked by chloroquine and bafilomycin A1 which inhibit lysosomal proteases by raising the lysosome pH (Zetser et al., 2004; Zhitomirsky and Assaraf, 2015; 2016). Subsequent studies employing site-directed mutagenesis, gene silencing, and pharmacological inhibitors have identified cathepsin L as the primary lysosomal protease responsible for heparanase processing and activation (Abboud-Jarrous et al., 2008; Abboud-Jarrous et al., 2005). We have noted that syndecan-1 and 4 are internalized by cells following addition of exogenous heparanase, co-localizing with heparanase in endocytic vesicles (Gingis-Velitski et al., 2004b; Levy-Adam et al., 2010). Structurally, all syndecans are composed of an extracellular domain, membrane domain, and a conserved short C-terminal cytoplasmic domain divided into the first conserved region (C1), the variable domain (V), and the second conserved region (C2). Each of these cytoplasmic domains has been shown to interact with specific adaptor molecules and to mediate cellular function (Beauvais and Rapraeger, 2004; Tkachenko et al., 2005).

Heparanase interacts with syndecans by virtue of the typical high affinity that exists between an enzyme and its substrate. This high affinity interaction directs rapid and efficient cellular uptake of the heparanase-syndecan complex (Gingis-Velitski et al., 2004b; Shteingauz et al., 2014). Peptide corresponding to the heparin/HS binding domain of heparanase (Lys158-Asp171, termed KKDC) similarly associates with the plasma membrane and induces clustering of syndecans, resulting in improved cell spreading (Levy-Adam et al., 2005; Levy-Adam et al., 2008). Notably, syndecan clusters formed by the KKDC peptide were exceptionally large and failed to be internalized (Levy-Adam et al., 2005; Levy-Adam et al., 2008). Likewise, heparanase-2 (Hpa2), a close homolog of heparanase, binds HS with high affinity but fails to undergo internalization (Levy-Adam et al., 2010), implying that interaction and clustering per se are not sufficient for the internalization of syndecan and its cargo. We examined the role of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic domain in heparanase processing (Shteingauz et al., 2014). To this end, we transfected cells with a full length mouse syndecan-1 or deletion constructs lacking the entire cytoplasmic domain (delta), the conserved (C1 or C2) or variable (V) regions. Heparanase uptake was markedly increased following syndecan-1 overexpression, thus challenging the notion that cell surface HS is at saturation and does not limit ligand binding. In contrast, heparanase was retained at the cell membrane and its processing was impaired in cells overexpressing syndecan-1 deleted for the entire cytoplasmic tail (Shteingauz et al., 2014). Subsequent studies revealed that the C2 and V regions of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail mediate heparanase processing. Furthermore, syntenin, known to interact with syndecan C2 domain, and α actinin are essential for heparanase processing (Shteingauz et al., 2014). These results illustrate the tight regulation of heparanase activation, and shed light on syndecan-mediated endocytosis. Interestingly, syndecans and syntenin, via interaction with ALIX, have been implicated in regulating the biogenesis of exosomes (Baietti et al., 2012). Importantly, as discussed below, heparanase facilitates the production of exosomes and regulates their secretion and composition (Roucourt et al., 2015b), implying that heparanase-syndecan-syntenin establish a linear axis that regulates exosome formation (Shteingauz et al., 2014) and the related effects on tumor progression (Shteingauz et al., 2014).

4.2. Heparanase regulates secretion, composition, and function of tumor cell-derived exosomes

Exosomes are membrane-bound vesicles which are released into the extracellular space when a multivesicular endosome housing the exosomes fuses with the plasma membrane (Simons and Raposo, 2009; Tkach and Théry, 2016). Exosomes are powerful mediators of intercellular communication that drive tumor progression by regulating the behavior of tumor and host cells both locally within the tumor microenvironment and distally throughout the body (Peinado et al., 2011; Zhang and Grizzle, 2011). Exosomes accomplish this regulatory function by docking to recipient cells and delivering their cargo of protein, DNA, mRNA and miRNA (Simons and Raposo, 2009). When exosomes come in contact with recipient cells, the cells can undergo immediate stimulation through cell signaling mediated by exosomal proteins, or cell behavior can be modified by the proteins, microRNA or mRNA delivered by the exosome. Most cells secrete exosomes, but their secretion is upregulated in disease states. In cancer, secretion of exosomes often increases as tumors transit toward a more aggressive phenotype. The tumor-host crosstalk mediated by exosomes has multiple effects that can influence processes such as formation of the pre-metastatic niche, angiogenesis, host immune function as well as conferring anticancer drug resistance (Di Marzo et al., 2016; Peinado et al., 2012; Peinado et al., 2011; Wojtuszkiewicz et al., 2016; Zhang and Grizzle, 2011). Several members of the Rab protein family have been shown to control exosome formation and more recently it was reported that syndecan proteoglycans, through their interaction with the syntenin-ALIX complex, influence the biogenesis of exosomes (Baietti et al., 2012; Ostrowski et al., 2010; Peinado et al., 2011). Briefly, syntenin interacts with the syndecan core protein via two PDZ domains as well as with ALIX via three LYPXnL motifs (Baietti et al., 2012). ALIX then binds to ESCRT-III (endosomal-sorting complex required for transport), the machinery responsible for intraluminal vesicle formation at multivesicular endosomes (MVEs). Importantly, relevant to the current review, it was further demonstrated that heparanase activates the syndecan-syntenin-ALIX exosome pathway (Baietti et al., 2012; Roucourt et al., 2015b). Briefly, heparanase activity in endosomes trims long HS chains into shorter ones, allowing clustering of syndecans through lateral interactions between their HS polysaccharide chains (David and Zimmermann, 2016; Roucourt et al., 2015a). Heparanase-induced clustering is thought to stimulate the binding of syndecan cytoplasmic domains to the tandem PDZ domains of syntenin, driving ALIX-ESCRT-mediated sorting into exosomes (David and Zimmermann, 2016; Friand et al., 2015; Roucourt et al., 2015a). Notably, heparanase activity also facilitated the recruitment of CD63 into exosomes, in a syntenin-dependent manner (David and Zimmermann, 2016; Roucourt et al., 2015a). All in all, a complex picture is emerging, in which syndecans, CD63 and possibly other membrane proteins that associate with endosomal syndecan and/or tetraspanin-enriched microdomains, are sorted into exosomes by a shared heparanase-syndecan-syntenin-ALIX pathway machinery (David and Zimmermann, 2016; Friand et al., 2015). Heparanase effects on exosome biogenesis seem best explained by heparanase activity on syndecan, promoting the assembly of syndecan in complexes that, by recruiting syntenin and ALIX–ESCRT, promote endosomal membranes to bud (Friand et al., 2015). From that perspective, heparanase inhibitors (Vreys and David, 2007; Vreys et al., 2005) as well as specific syntenin-PDZ inhibitors might be of particular interest for cancer, where both exosome release and heparanase are often elevated in the more aggressive forms of disease (Ramani et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2013).

In support of the above considerations, the first evidence that heparanase was involved in exosome biogenesis came when we discovered that enhanced heparanase expression in myeloma cells, or exposure of cells to exogenous heparanase, dramatically increased exosome secretion (Thompson et al., 2013) (Fig. 2). Thus, heparanase released by a tumor cell or by host cells (e.g., macrophages) could diffuse within the microenvironment and impact neighboring tumor cells and enhance, among other effects, their secretion of exosomes. Heparanase enzyme activity is required for enhanced exosome secretion because enzymatically inactive forms of heparanase, even when present in high amounts, do not substantially increase exosome secretion (Thompson et al., 2013). Heparanase also impacts exosome protein cargo as reflected by higher levels of syndecan-1, VEGF and HGF in exosomes secreted by heparanase-high expressing cells as compared to heparanase-low expressing cells (Thompson et al., 2013). In functional assays, exosomes from cells with high expression of heparanase stimulated spreading of tumor cells on fibronectin and invasion of endothelial cells through extracellular matrix, better than did exosomes secreted by cells expressing low levels of heparanase, suggesting a role in promoting tumor cell spreading and angiogenesis (Thompson et al., 2013).

Our finding that heparanase is present in exosomes (Thompson et al., 2013) raises the possibility that the enzyme is delivered to distal locations via exosomes (Fig. 2). Because of the known role of heparanase in promoting angiogenesis and metastasis, delivery of the enzyme via exosomes may play a role in establishing niches to which tumor cells eventually home and grow. Our results indicate that heparanase can lead to secretion of exosomes that interact with both tumor and host cells and drive them toward behaviors associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype which includes drug resistance. Notably, because heparanase enhances exosome secretion, the tumor microenvironment will be bathed in much higher levels of exosomes when tumors are expressing high levels of heparanase. Emerging data indicate that exosomes can act as barriers to anti-cancer therapy by interacting with tumor cells and enhancing their chemoresistance (Au Yeung et al., 2016). Indeed, our ongoing studies reveal that heparanase enhances both exosome docking (Purushothaman et al., 2016) and exosome-mediated transfer of chemoresistance to tumor cells. Collectively, our studies reveal that heparanase helps drive exosome secretion, alters exosome composition and facilitates production and docking of exosomes that impact both tumor and host cell behavior thereby promoting tumor progression and chemoresistance (Thompson et al., 2013).

4.3. Heparanase enhances tumor growth and chemoresistance by augmenting autophagy