Abstract

Background: Pulmonary nodules are frequently detected during diagnostic chest imaging and as a result of lung cancer screening. Current guidelines for their evaluation are largely based on low-quality evidence, and patients and clinicians could benefit from more research in this area.

Methods: In this research statement from the American Thoracic Society, a multidisciplinary group of clinicians, researchers, and patient advocates reviewed available evidence for pulmonary nodule evaluation, characterized six focus areas to direct future research efforts, and identified fundamental gaps in knowledge and strategies to address them. We did not use formal mechanisms to prioritize one research area over another or to achieve consensus.

Results: There was widespread agreement that novel tests (including novel imaging tests and biopsy techniques, biomarkers, and prognostic models) may improve diagnostic accuracy for identifying cancerous nodules. Before they are used in clinical practice, however, better evidence is needed to show that they improve more distal outcomes of importance to patients. In addition, the pace of research and the quality of clinical care would be improved by the development of registries that link demographic and nodule characteristics with patient-level outcomes. Methods to share data from registries are also necessary.

Conclusions: This statement may help researchers to develop impactful and innovative research projects and enable funders to better judge research proposals. We hope that it will accelerate the pace and increase the efficiency of discovery to improve the quality of care for patients with pulmonary nodules.

Contents

Overview

Introduction

Methods

Results

Framing Research Questions for Novel Diagnostic Procedures

Nodule Registries

Data Sharing

Diagnostic Imaging and Invasive Procedures

Biomarkers

Prediction and Prognostic Models

Emerging Treatments

Logistics and Implementation

Patient-centered Outcomes

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Overview

Pulmonary nodules are frequently detected during diagnostic chest imaging and as a result of lung cancer screening. Current guidelines for their evaluation are largely based on low-quality evidence, and patients and clinicians could benefit from more research in this area.

In this research statement from the American Thoracic Society, a multidisciplinary group of clinicians, researchers, and patient advocates reviewed available evidence for pulmonary nodule evaluation, characterized areas to direct future research efforts, and identified fundamental gaps in knowledge and strategies to address them.

We developed the following key recommendations:

-

•

The efficacy and effectiveness of new diagnostic strategies (including novel imaging tests and biopsy techniques, biomarkers, and prognostic models) should be evaluated using established phases of test development, from identification of a novel strategy or characteristic to establishment of clinical utility.

-

•

Registries that link demographic and nodule characteristics with patient-level outcomes should be developed.

-

•

Pulmonary nodule evaluation strategies are guided by subsequent treatment options for early-stage lung cancer, and these treatments should be rigorously studied.

-

•

Potential interventions and quality metrics to improve nodule evaluation processes should be studied before requiring their implementation.

-

•

Tests and interventions should be evaluated for their impact on patient-centered outcomes.

This statement may help researchers develop impactful and innovative proposals and enable funders to better judge novel research proposals. We hope that it will quicken the pace and increase the efficiency of discovery to improve the quality of care for patients with pulmonary nodules.

Introduction

Hundreds of thousands of patients are diagnosed every year with incidental pulmonary nodules (1–3), fueled by the ever-increasing number of individuals who undergo imaging studies (4–7). The number of patients with pulmonary nodules will increase, because multiple organizations, including the American Thoracic Society (ATS), recommend annual low-dose computed tomography (CT) screening for adults at high risk of developing lung cancer (8–13). These recommendations are based on the results of the National Lung Screening Trial, which showed that screening decreased lung cancer mortality (14). But this benefit came with a substantial drawback, as almost 40% of subjects had a positive screening test result during the three rounds of screening, mostly as a result of pulmonary nodule identification.

The majority of pulmonary nodules are benign, but the most worrisome cause of a pulmonary nodule is bronchogenic carcinoma. Because of the lethality of lung cancer, the difficulty of sampling small lesions for biopsy, and the relatively slow rate of growth even if the nodule is lung cancer, it is recommended that most patients with nodules undergo further evaluation (15–17). Patients essentially have three options to consider after a nodule is identified: (1) active surveillance; (2) additional diagnostic procedures, including positron emission tomography (PET), biopsy (percutaneous or bronchoscopic), and surgical removal; or (3) no further monitoring or workup (17, 18). Optimizing benefit and reducing risk for patients undergoing nodule evaluation requires the patient and clinician to balance a desire for the certainty of a diagnosis against the tolerance for the unknown, while assessing the likelihood of malignancy, the yield and risk of invasive procedures, and the potential risk of delayed diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Patients with pulmonary nodules want to know how likely the nodule is to be cancer, what are the safest and most reliable methods of diagnosis, which nodules can be serially observed and which need more invasive evaluation, and what are the best ways to discuss these concerns with their clinicians (19, 20). For the most part, answers to these fundamental questions are based on limited, indirect, or low-quality evidence.

We convened a workshop to establish a framework for lung nodule evaluation research and to facilitate the pace, impact, and efficiency of discovery. Outlining important research questions and potential strategies for evaluation by multidisciplinary groups can better and more effectively address the needs of patients (21).

Methods

We assembled an international multidisciplinary (medical oncology, nursing, pulmonary, radiology, thoracic surgery, and public health) group of researchers, clinicians, and patient advocate stakeholders with expertise in pulmonary nodules at the May 2013 ATS International Conference. We obtained representation from the following ATS committees and assemblies: Documents Development and Implementation Committee, Patient and Family Education Committee, Behavioral Science and Health Services Research Assembly, Clinical Problems Assembly, Nursing Assembly, Thoracic Oncology Assembly, and the Patient Advisory Roundtable (COPD Foundation and Free to Breathe). Conflicts of interest were disclosed and managed according to the policies and procedures of the ATS.

The chairs (C.G.S. and M.K.G.) identified several topics for discussion that were vetted before the workshop. Participants were selected as moderators for breakout sessions, and each provided input about the planned agenda. We selected six focus areas: (1) diagnostic imaging and invasive procedures, (2) biomarkers, (3) prognostic models, (4) emerging treatments, (5) logistics and implementation, and (6) patient-centered outcomes.

The workshop consisted of presentations by experts in related fields, including screening for colorectal cancer, comparative effectiveness research, and lung cancer biomarker research. After these presentations, each participant engaged in breakout sessions in two of the focus areas, depending on interest. We did not use formal checklists or consensus methods, because we did not intend to prioritize one area or specific topic over another (21).

If available, participants considered the findings of systematic reviews when evaluating these topics but did not conduct new or updated reviews. Participants discussed key questions related to five topics: (1) identify the information/knowledge gaps, (2) identify why the topic is important, (3) identify relevant stakeholders, (4) review appropriate methods and approaches to address the gaps, and (5) identify potential sources of research funding.

Participants also suggested potential derivatives. For example, we identified tools or methods that would enhance or facilitate research efforts. Participants also identified potential products that could be developed after evaluating many of the key questions. Each item includes: (1) a description, (2) how it would improve care or advance the field, (3) what resources would be required for development, (4) what resources would be required for validation and evaluation, and (5) how would it be implemented.

After the workshop, a writing committee drafted a report based on an outline developed by the project co-chairs. The draft was circulated to the members of the writing group with revisions at each step and consensus achieved through discussion. The final document was approved by the ATS Board of Directors as an Official ATS Policy Statement.

The primary audience for this report includes clinicians, scientists, and patients who are affected by pulmonary nodules or lung cancer and undergo lung cancer screening. Institutions and organizations that solicit and fund research projects in these areas may also use this report to guide their efforts and decisions, particularly those that focus on patient-centered outcomes. Finally, healthcare systems and purchasers may find this report helpful when evaluating the evidence base for implementation of performance measures for the care of patients with pulmonary nodules.

Results

We identified several key questions and derivatives (Tables 1 and 2) for each focus area as well as several themes that overlapped multiple areas. These cross-cutting themes are discussed first, followed by a section for each focus area.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Questions

| Gaps | Importance | Stakeholders | Methods/Approaches | Funding | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic imaging and invasive procedures | ||||||

| Question 1: How can we validate current practice guidelines for the evaluation of lung nodules? | ||||||

| Effectiveness of and adherence to the current practice guidelines, associated patient outcomes, and resource use engendered by the guidelines are unknown, especially for subsolid nodules | Determine the proper balance of benefit and harm at the patient and system level | Patients | Comparative effectiveness research methodologies | AHRQ | ||

| Determine the cost effectiveness of evaluation strategies | Clinicians (P, R, TS) | Cost-effectiveness methods | ACRIN | |||

| Determine clinician adherence based on guidelines | Industry | Randomized and pragmatic trials of evaluation strategies | Foundations | |||

| Determine when to incorporate into clinical practice | Payers | NIH (NHLBI/NCI) | ||||

| Guideline developers | VA | |||||

| Question 2: How and when should advances in image-based detection and characterization of lung nodules (e.g., computer-aided detection methods) and nonsurgical biopsy techniques become incorporated into clinical practice? | ||||||

| Identification and reporting of lung nodules is unpredictable | Use of new modalities based on test characteristics, without understanding of risks and benefits, may be associated with adverse outcomes (unnecessary testing, anxiety, and inappropriate use) | Patients | Comparative effectiveness research methodologies, including evaluation of test characteristics in usual care settings and risks/benefits of use | ACR | ||

| Ability to measure and characterize nodules is inconsistent | Inappropriately slow uptake of new modalities can lead to missed opportunities to intervene in patients with early cancer | Clinicians (P, R) | Cost-effectiveness methods | AHRQ | ||

| Surveillance practices vary | Efficacy of standardized review and reporting of imaging findings demonstrated in similar circumstances (e.g., mammography) | Healthcare systems | Randomized and pragmatic trials of new technologies | Industry | ||

| No definition of the added value of a new technology | Industry | Quasi-experimental approaches | NIH (NHLBI/NCI) | |||

| Biomarkers |

||||||

| Question 1: Can we optimize biomarker acquisition from small specimens? |

||||||

| Amount of histological and molecular information required from small specimens is increasing | Acquisition of adequate tissue for assessment of potential biomarkers | Patients | Bench research to determine feasibility | AHRQ | ||

| Optimal procedures to provide sufficient specimens are unknown | Prioritization of testing as number of targeted therapeutics increase | Clinicians (MO, P, TS) | Comparative effectiveness methodologies, including evaluation of proposed procedures | Cooperative oncology groups (e.g., SWOG) | ||

| Quality of procedures in clinical settings is unknown | More accurate prediction of rates of growth and risk of malignancy | Healthcare systems | Observational studies | DOD | ||

| Industry | Translational research to determine efficacy of biomarker acquisition in a usual care setting | Foundations | ||||

| Payers | Randomized and pragmatic trials of new technologies | Industry | ||||

| Policy makers | NIH (NCI) | |||||

| VA | ||||||

| Question 2: Can risk biomarkers distinguish between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules as well as aggressive and nonaggressive tumors? | ||||||

| Pathogenesis of cancer development, growth, and spread is poorly understood | Identification of biomarkers can also identify key mechanisms of cancer development and spread | Patients | Bench development of biomarkers | ATS | ||

| Current clinical prediction models may not be sufficiently accurate to influence practice | Use of biomarkers may improve discrimination between benign and malignant nodules | Clinicians (P, RO, TS) | Validation studies | DOD | ||

| Current diagnostic testing processes do not adequately differentiate patients who should receive different intensity of follow up | Benefit of new technologies should outweigh harms and costs both at patient and population level | Healthcare systems | Comparative effectiveness research methodologies | EDRN | ||

| Industry | Randomized and pragmatic trials, including examination of observation surveillance vs. biopsy, guided by biomarker risk assessment | Foundations | ||||

| Policy makers | Industry | |||||

| Payers | NIH (NCI) | |||||

| VA | ||||||

| Prognostic models | ||||||

| Question 1: What clinical, laboratory, and radiologic characteristics can be used to improve lung cancer risk prediction and improve subsequent outcomes? |

||||||

| Models for estimating the probability of malignancy in patients with solid solitary pulmonary nodules have been developed and validated at population level but not in routine practice settings | Widespread adoption of lung cancer screening will increase the number of smokers identified with subsolid and/or multiple nodules | Patients | Comparative effectiveness research methodologies, including evaluation of risk factors, radiologic features, and novel biomarkers | Foundations | ||

| Accuracy of these models for estimating risk of lung cancer for patients with subsolid and/or multiple nodules is unknown | Accurate assessment of the risk of lung cancer has important implications for the need of additional, and potentially invasive, follow-up procedures | Clinicians (P, R, TS) | Validation across multiple settings and populations | NIH (NCI) | ||

| Healthcare systems | VA | |||||

| Payers | ||||||

| Policy makers | ||||||

| Medical societies | ||||||

| Question 2: Which small, slow-growing nodules can be observed with serial imaging vs. requiring biopsy or resection? | ||||||

| Risk of invasion and/or metastasis for slow-growing, potentially malignant lung nodules is not well characterized | Screening will cause overdiagnosis of slowly growing cancers that would not otherwise spread or metastasize | Patients | Observational studies evaluating the association of risk factors, radiologic features, and novel biomarkers with risk of aggressive, invasive cancer | DOD | ||

| Which subset of slow-growing 1- to 3-cm nodules can be followed with serial imaging vs. need for biopsy and/or treatment is unclear | Predictive models of the risk of spread and metastasis may be helpful in guiding clinical management | Clinicians | Validation across multiple settings and populations | Foundations | ||

| Healthcare systems | NIH (NCI) | |||||

| Payers | VA | |||||

| Policy makers | ||||||

| Medical societies | ||||||

| Emerging treatments | ||||||

| Question 1: What is the effectiveness of SBRT and other ablative therapies for patients with stage IA NSCLC? |

||||||

| Despite increases in the use of SBRT for stage IA NSCLC, its effectiveness compared with surgical resection for operable patients has not been established | Many patients with nodules are not candidates for anatomic surgical resection | Patients | Comparative effectiveness research, including resection vs. SBRT | Cooperative oncology groups | ||

| Emerging therapies for early-stage NSCLC will influence upstream diagnostic testing and decision-making, including the necessity of definitive tissue diagnosis | Clinicians (P, RO, TS) | Trials (SBRT ongoing trials have encountered difficult recruitment) | NIH (NCI) | |||

| Healthcare systems | Cost-effectiveness methods | VA | ||||

| Industry | Multicenter phase II trials to evaluate ablative procedures such as RFA, cryoablation, and microwave ablation | |||||

| Payers | Randomized phase II trial to compare RFA to SBRT for stage IA NSCLC with tumors ≤ 3 cm | |||||

| Policy makers | ||||||

| Question 2: What interventions or therapies may stop or slow the growth rate of lung cancer that is identified as small nodules? | ||||||

| Low-quality evidence suggests some therapies may prevent the development of cancer in high-risk patients | Chemoprevention has strong potential to improve mortality and reduce morbidity | Patients | Comparative effectiveness research, including analysis of administrative data | Cooperative oncology groups | ||

| Evidence for the effectiveness of treating patients with nodules with these potential therapies is lacking | Any potential treatment needs to be very safe and well tolerated because many patients with nodules do not have lung cancer | Clinicians (P, RO, TS) | Multicenter phase II trials | Industry | ||

| Healthcare systems | Randomized trials | NIH (NCI) | ||||

| Industry | VA | |||||

| Payers | ||||||

| Policy makers | ||||||

| Implementation | ||||||

| Question 1: How should nodule evaluation processes and tools be implemented to optimize risks and benefits? |

||||||

| Which nodule evaluation strategies can be implemented in routine-care settings that maximize patient-centered outcomes is unclear | Limited evidence suggests systemic, standardized, and multidisciplinary approaches to nodule evaluation are associated with better outcomes | Patients | Comparative effectiveness methodologies | Foundations | ||

| Unclear which processes and strategies offer the most benefit to patients with least risk and appropriate resource use | Clinicians (N, MO, P, R, RO, TS) | Randomized and pragmatic trials | Healthcare systems | |||

| Healthcare systems | NIH (NCI) | |||||

| Payers | VA | |||||

| Policy makers | ||||||

| Medical societies | ||||||

| Question 2: Which, if any, performance measures and quality metrics should be incorporated into routine practice? |

||||||

| Which, if any, performance measures will most positively impact practice is unclear | Current guidelines are based on low-quality evidence, and inappropriate use of performance measures may negatively impact outcomes | Patients | Comparative effectiveness methodologies | Foundations | ||

| Quality assessment is essential for developing high-quality care and minimizing harms | Clinicians (N, MO, P, R, RO, TS) | Randomized and pragmatic trials | Healthcare systems | |||

| Healthcare systems | NIH (NCI) | |||||

| Payers | VA | |||||

| Policy makers | ||||||

| Medical societies | ||||||

| Patient-centered outcomes | ||||||

| Question 1: What are the unmet needs and critical concerns of patients, families, clinicians, and other stakeholders surrounding pulmonary nodule evaluation? |

||||||

| Clinicians, researchers, and other stakeholders may not understand patients’ concerns | Patient needs should drive agenda for further research and improvements in patient care | Patients | Techniques to build consensus, give all stakeholders a voice, and prioritize topics (e.g., modified Delphi approach, nominal group technique, analytic hierarchy process) | AHRQ | ||

| Relevant stakeholders have not discussed competing priorities and unmet needs of different parties | All stakeholders should have a voice | Clinicians (N, MO, P, R, RO, TS) | Patient-centered outcomes research, including mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to elicit patient views | DOD | ||

| Healthcare systems | Foundations | |||||

| Payers | NIH (NCI) | |||||

| Policy makers | PCORI | |||||

| VA | ||||||

| Question 2: How can patient–clinician communication processes and tools influence patient-centered outcomes when a potentially malignant nodule has been identified? | ||||||

| Most patients do not understand their personal risk of lung cancer | Poor communication processes may lead to distress and anxiety | Patients | Patient-centered outcomes research, including observational, mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate the association of risk communication with patient-centered outcomes | AHRQ | ||

| Patient–clinician communication is suboptimal in the context of lung nodule evaluation | Overestimating lung cancer risk may lead to inappropriate choices (e.g., resection of low-risk nodule, longer than necessary follow-up) | Clinicians (N, MO, P, R, RO, TS) | Randomized and pragmatic trials of communication and/or decision-making tools | DOD | ||

| Most patients and clinicians do not optimally engage in shared decision-making, including in setting of nodule evaluation | Underestimating lung cancer risk may be associated with harmful behaviors (continued smoking) and nonadherence with nodule evaluation | Healthcare systems | Foundations | |||

| Suboptimal decision-making processes in which patient views are not fully incorporated may be associated with patient distress and nonadherence with subsequent screening or nodule evaluation | Payers | NIH (NCI) | ||||

| Policy makers | PCORI | |||||

| VA | ||||||

Definition of abbreviations: ACR = American College of Radiology; ACRIN = American College of Radiology Imaging Network; AHRQ = Agency for Health Care Research and Quality; ATS = American Thoracic Society; DOD = Department of Defense; EDRN = Early Detection Research Network; MO = medical oncology; N = nursing; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NSCLC = non–small cell lung cancer; P = pulmonary; PCORI = Patent-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; R = radiology; RFA = radiofrequency ablation; RO = radiation oncology; SBRT = stereotactic body radiotherapy; TS = thoracic surgery; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Table 2.

Summary of Derivatives

| Description | How/Why? | Development Resources | Validation/Evaluation | How/Where? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-cutting derivatives | ||||

| Nodule registries: EMR-based radiology reports with links to patient-level administrative data for identification and description of lung nodules on chest imaging | Development of clinically useful EMR-based registries, potentially aided by natural language processing, will facilitate ongoing research and quality improvement initiatives | ATS (BSHSR, Clinical Problems, nursing, TOA) | Multicenter adoption and tracking of subsequent management | Make available on ATS (and other) websites once validated |

| Identifying patients with nodules and associated clinical and radiological characteristics is currently very expensive or impractical | Other professional societies | Compare to prior management | Cooperate with providers of reporting systems or EMR to incorporate | |

| Could reduce variability in practice | Consensus statement on reporting elements, incorporation into reporting systems/EMR | Partner with other stakeholders such as the American College of Radiology, ACCP, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Society for Radiation Oncology, American College of Physicians | ||

| Could inform clinicians about appropriate management | ||||

| Consortiums to pool clinical data and specimens for biomarker development and validation in screening centers | Could provide diverse, unbiased approach to validate biomarkers and strategies to implement biomarkers | ATS (TOA, RCMB, Clinical Problems) | Patient testing | Potential partners include ATS, DOD/VA, foundations, IASLC, NCI and CRN, NIH-NHLBI |

| Could guide use of biomarkers, refine diagnostic approach to lung nodules | Grants: NCI | Lab testing | ||

| Healthcare systems | Clinician testing | |||

| Payers | ||||

| Policy makers | ||||

| Development of a framework and consensus manual on added value of new technologies for the evaluation of pulmonary nodules | Could provide minimal requirements or gold standards for the level of evidence of the study itself, mathematical evaluation of added value, balance of gain in diagnostic accuracy vs. additional efforts and costs of the new technology. Could improve translation of research outcomes to clinical practice and to educate clinicians | Consensus statement developed by working group connected to association (researchers, clinicians, patients, systems, payers, grant funders) | Multicenter adoption and tracking of subsequent management | Connect to ATS/ACCP to form working group of interested experts |

| Pragmatic trials | Review of literature and consensus meetings | |||

| Comparative effectiveness research methodologies | ||||

| Diagnostic imaging and invasive procedures | ||||

| Evidence-based, easily electronically accessed (web, mobile applications) user (clinician and patient)-friendly lung cancer risk stratification tools for pulmonary nodules. Could include unbiased information on lung cancer risk stratification, commercially available diagnostic tests, and listings of clinical expertise based on availability of technologies and nodule clinics | Could improve risk estimation by clinicians. Could provide tailored information for patients. Could improve information dissemination, regionalization, decision-making, and resource use | ATS (BSHSR, Clinical Problems, nursing, TOA) | Patient testing | Conference |

| Other professional societies | Lab testing | Peer-reviewed journal | ||

| Healthcare systems | Clinician testing | Research study | ||

| Payers | Feedback section on website | ATS website | ||

| Policy makers | Website developer, content development, connection to an association (e.g., ATS, ACCP, patient advocacy group) | |||

| Biomarkers | ||||

| Incorporation of data elements regarding small specimen acquisition and processing into a voluntary registry that acquires quality and performance data from interventional pulmonary procedures | Could provide education to interventional pulmonary programs. Could enhance standardization of protocols and innovation to improve performance | ATS/ACCP | Patient testing | Conference |

| Grants | Lab testing | Peer-reviewed journal | ||

| Healthcare systems | Clinician testing | Research study | ||

| Payers | ||||

| Policy makers | ||||

| Implementation | ||||

| Development of evidence-based performance measures and quality metrics | Could improve quality and adherence to guidelines. Could facilitate reporting of nodule and patient characteristics | Healthcare systems | Stakeholder consensus | Output from stakeholder conference |

| Patient stakeholder groups | ||||

| Payers | ||||

| Policy makers | ||||

| Professional societies | ||||

| Patient-centered outcomes | ||||

| Multi-stakeholder consensus group whose purpose is to use formal methods to elicit unmet patient needs, prioritize a research agenda, identify concerns, and offer potential solutions | Uses formal methods to obtain consensus from multiple stakeholders. Sets a research agenda based on needs identified as most important to patients, with input from multiple stakeholders | ATS (BSHSR, Clinical Problems, nursing, TOA, PAR) | Elicit feedback from others not involved in group but pulled from same stakeholder groups to ensure face validity | Conference |

| Healthcare systems | Potential funding from NCI, PCORI, professional societies, and healthcare systems | |||

| Other professional societies | ||||

| Patients | ||||

| Patient advocacy organizations | ||||

| Payers | ||||

| Policy makers | ||||

| Instruments that measure decision quality specific to issues surrounding lung cancer screening and nodule evaluation | Context-specific instruments better able to measure decision quality than generic instruments. Could help measure effect of decision support tools | ATS (BSHSR, Clinical Problems, nursing, TOA) | Patient testing | Conference |

| Grants | Peer-reviewed journal | |||

| Healthcare systems | Research study | |||

| Payers | ||||

| Policy makers | ||||

| Individually tailored patient- and clinician-accessible communication aids, including decision support tools and educational materials that address key patient questions and improve satisfaction with decision-making | Could improve patient–clinician communication processes. Could allow patients to weigh options based on their own preferences and values. Could facilitate shared decision-making | ATS (BSHSR, Clinical Problems, SOTO, PAR) | Patient testing | Conference |

| Grants | Clinician testing | ATS website | ||

| Healthcare systems | Lab testing/role play/simulated clinic visits | |||

| Payers | Actual recorded clinic visits | |||

| Policy makers | ||||

Definition of abbreviations: ACCP = American College of Chest Physicians; ATS = American Thoracic Society; BSHSR = Behavioral Science and Health Services Research; CRN = Cancer Research Network; DOD = Department of Defense; EMR = electronic medical record; IASLC = International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NIH = National Institutes of Health; PAR = Public Advisory Roundtable; PCORI = Patent-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; RCMB = Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology; SOTO = Section on Thoracic Oncology; TOA = Thoracic Oncology Assembly; VA = Veterans Affairs.

Framing Research Questions for Novel Diagnostic Procedures

There is a fair amount of evidence that novel diagnostic imaging and invasive procedures, biomarkers, and predictive models can improve diagnostic accuracy and predict the risk of future events, such as developing lung cancer. Unfortunately, the evaluation of most of these tests and algorithms has been limited to uncontrolled studies of diagnostic accuracy performed in specialized centers. There are limited data regarding whether they influence outcomes that are more important to patients, clinicians, and/or healthcare systems. We agreed that novel diagnostic procedures should be proven to provide incremental value above and beyond currently available information before they are widely adopted into clinical care.

Many novel diagnostic tests and procedures have promise for improving care for patients with pulmonary nodules. These include imaging methodologies, such as computer-aided detection (X-ray [22] and CT scan [23–25]), computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) (26–29), volume and mass analysis (30, 31), gated PET imaging (32, 33), PET imaging using novel radioactive tracers (32, 33), novel algorithms to reconstruct CT images allowing lower radiation dose (32–34) (e.g., model-based iterative reconstruction), and procedures such as navigational bronchoscopy and radial ultrasound (17). There is also great potential for novel biomarkers to distinguish benign from malignant nodules and aggressive versus relatively indolent cancers (35, 36). Biomarkers can be classified in multiple ways based on anatomic site of sampling (e.g., serum, sputum, urine, and exhaled breath markers), target of detection (e.g., DNA methylation, gene expression, and ELISA), or type (e.g., DNA, microRNA, and autoantibody). In addition, several models using patient and nodule characteristics for predicting cancer risk in patients with solid nodules have been developed (37–41), but more studies are needed to determine whether these models provide incremental value above and beyond clinical judgment and intuition (42).

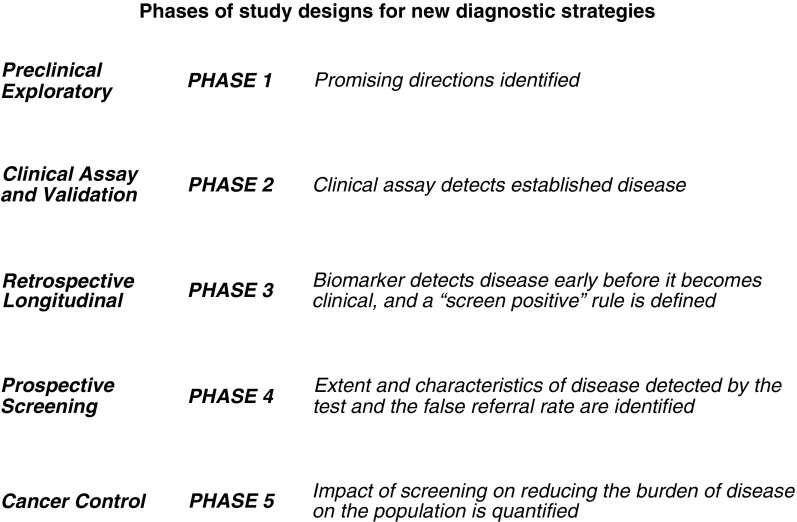

It is critical to develop novel diagnostic tests and strategies to improve diagnostic accuracy for patients with pulmonary nodules. But at least over the short term, it might be more impactful to demonstrate that existing diagnostic technologies improve patient-centered outcomes. Use of defined phases of research should guide how these tests are evaluated (43–46) (Figure 1). Few to no prospective trials of diagnosis or the impact of potential novel tests or strategies on clinical outcomes have been performed.

Figure 1.

Proposed phases of study designs for new diagnostic strategies for improving ability to predict which pulmonary nodules are benign and which are cancerous (adapted by permission from Reference 44).

It is important to consider which tests show the most promise to impact clinical practice when choosing candidates for prospective studies. Currently, most patients with nodules undergo follow-up CT scans (16). Given the relatively low risk of serial imaging, the negative predictive value of a novel test will likely need to be very high to substantially reduce the number of patients who require follow-up imaging or the total number of scans these patients receive. Conversely, a novel test would need to have very high positive predictive value to recommend surgical resection when information from currently available imaging studies suggests the nodule is benign or can be safely monitored. Accordingly, studies that report the likelihood of how the biomarker would change decision-making (e.g., the net reclassification index [47]) may be useful to guide decisions for which tests should be studied past Phase 2 (Figure 1). In addition, explicit information of the risks of the novel test (including invasiveness and costs to patients and systems), feasibility, and data regarding the potential use of the test (see Reference 48 as an example) would strengthen research proposals.

Although developed for biomarkers, use of the prospective-specimen-collection and retrospective-blinded-evaluation (PRoBE) design may improve the rigor of intermediate phases of novel test development and could strengthen research proposals for other diagnostic tests and strategies (45). The crux of the PRoBE design requires a priori consideration of how the novel test will change diagnostic accuracy above current methods while also stipulating data collection processes. Furthermore, while awaiting trials for evidence regarding the impact of diagnostic imaging and procedures on health outcomes, it may be helpful to use evidence-based grading systems to more formally evaluate their clinical utility (49, 50).

Nodule Registries

The pace of discovery would be substantially improved through the creation of nodule registries. Current research is stymied by the lack of reliable methods to identify patients with nodules in routine practice. Notably, the ATS and American College of Chest Physicians recommend the use of a registry to support lung cancer screening efforts, and use of a registry is required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (51, 52). Registries should be based on protocolized radiology reports, with detailed information regarding imaging and nodule characteristics and recommendations (53). As an example, the Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADS), developed by the American College of Radiology to support lung cancer screening, is a reporting tool (54, 55) that could serve as one element of a registry. Ideally, data regarding risks for lung cancer and nodule development, such as age, smoking characteristics, occupational exposures (e.g., asbestos), family history, and geographic information (e.g., residence in endemic fungal areas and radon exposure) would be linked with the electronic medical record. Natural language processing is increasingly used to identify nodule characteristics and may be useful to identify other data from the electronic medical record that are not routinely collected in individual data fields (56).

Registries should incorporate data regarding oncologic outcomes, procedures (including complications), smoking cessation efforts, adherence to management guidelines, and resource use. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare Program (57) collects similar information and should guide the collection of patient-level variables. Healthcare systems may want to emulate the registry used by the Department of Veterans Affairs to support its pilot lung cancer screening program (58). Some data may be challenging to collect by individual systems because patients frequently receive care at multiple institutions, so processes will need to be developed to link nodule data via healthcare information exchange.

Registries should ideally be a core component of system-level interventions to facilitate patient care. They are unlikely to gain traction if solely used for research purposes. They should optimize current practices and information technology systems to be feasible, user friendly, and cost effective. Registries could be used to track patients to improve adherence to follow-up plans and longitudinally follow changes in nodule characteristics. Given that most institutions lack systematic methods to identify or follow patients with nodules, registries could guide quality-improvement efforts. They could also be used as recruitment tools for trials and in comparative effectiveness research (59). Finally, registries themselves should be evaluated for their impact on patient-centered outcomes, healthcare system resource use, and costs.

Data Sharing

Registries are necessary but not sufficient to improve research efforts. Methods to share the data in registries are also required. For example, nodule consortiums could facilitate validation of prognostic models and increase the ability to test their clinical effectiveness. In addition, consortiums to pool clinical data with specimens should be developed. The ability to compare different diagnostic tests and implementation strategies will also be greatly facilitated by consortiums.

In particular, biomarker studies are often limited by lack of generalizability and inability to validate the marker in other settings. Registries should collect data regarding small sample acquisition and processing and have the ability to be linked with specimen banks. Several existing groups and consortiums could serve as models for collaboration, including COPD Outcomes-based Network for Clinical Effectiveness and Research Translation (CONCERT), the Early Detection Research Network of the National Cancer Institute, and the American College of Chest Physicians Quality Improvement Registry (AQuIRE) (60) (61–63).

Diagnostic Imaging and Invasive Procedures

Practice guidelines for the evaluation of lung nodules must be studied. Current recommendations regarding follow-up imaging and procedures after nodule detection (15–17) are based on indirect evidence regarding the risk of malignancy, the expected growth rate of malignant nodules, the capability to detect growth, and the risks of radiation, rather than evidence from randomized trials or large, well-designed observational studies. Guidelines for the management of subsolid nodules are grounded in even weaker evidence than those for solid nodules and should also be studied (15). It may also be helpful for guideline developers to use a living guideline model to more rapidly and efficiently disseminate important developments in the field (64).

Biomarkers

Given expected changes in treatment options, it will be important to obtain adequate samples from small specimens. Although most developmental work to date has used specimens from patients with advanced lung cancer, more research is required to understand the accuracy and prognostic value of biomarkers in local and regional stage disease. Optimizing the ability to test for multiple markers in small samples will also help to evaluate pathogenesis of cancer development, growth, and spread. Focusing biomarker studies on mechanistic factors will facilitate development of targeted therapies that can decrease or stop malignant nodule growth and metastasis.

Prediction and Prognostic Models

It is important to determine what factors accurately estimate the probability of lung cancer among patients with nodules and whether their use leads to improved outcomes. Several models for predicting cancer risk in patients with solid nodules have been developed, but they require additional validation (37–41). Only one model has explicitly included identification of multiple nodules as a predictor (39). No model has been developed for subsolid nodules, a common finding among subjects undergoing lung cancer screening. It is also important to assess the value of incorporating into future models readily available CT scan findings, such as the presence of emphysema. Another key issue is related to the concern for overdiagnosis of screening-detected nodules. Models that accurately predict nodule growth, invasion, and metastasis or other determinants of prognosis would be valuable to clinicians and patients and may help reduce overtreatment of slow-growing cancers. Finally, it will be useful to follow the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) reporting guidelines (65, 66).

Emerging Treatments

Treatment options for early-stage lung cancer directly impact the evaluation of pulmonary nodules (17, 18) and thus should be rigorously evaluated. For instance, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) has rapidly disseminated as a treatment for patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer at high risk for perioperative morbidity and mortality. A variety of other ablative therapies, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation, and microwave ablation, have been used for inoperable patients (67). However, there are no randomized trials comparing ablative therapies to surgery (67), and recent studies of SBRT versus sublobar resection were terminated early due to poor accrual (68). Because of the risks and challenges of biopsy in marginal surgical candidates, many patients with nodules undergo ablative therapy without a diagnosis of lung cancer (69). It will be important to compare the efficacy and effectiveness of emerging therapies to surgery to guide decision-making about the risks and benefits of different evaluation strategies and treating patients with pulmonary nodules that may not be cancerous. Guidelines (17) and decision models (70) should be evaluated for which patients SBRT constitutes acceptable treatment when a tissue diagnosis is not established.

It is also important to study the effectiveness of novel therapies on cancer prevention and tumor growth among patients with nodules. Trials of novel prevention agents and comparative effectiveness studies of potential existing therapies (e.g., oral or inhaled iloprost) should be conducted (71). Nodule growth on surveillance imaging may be an important intermediate outcome in these trials if they are underpowered to detect differences in lung cancer mortality (72).

Logistics and Implementation

Processes for nodule evaluation should be optimally implemented into routine care settings, because many patients do not receive guideline-adherent follow up (73, 74). Evidence supporting specific system-level interventions for nodule evaluation is limited, but these have been shown to be helpful in other settings (75–77). Possible interventions could include: creation of multidisciplinary teams, standardized reporting of results, development of care pathways, and development of registries to track patients with nodules. It is important to study the facilitators and barriers, effects on health outcomes, unintended consequences, and cost effectiveness of these interventions.

Performance measures and quality metrics will undoubtedly be developed. Indeed, the dissemination of lung cancer screening into practice has been accompanied by calls to institute these measures (51, 78). However, there is little high-quality evidence on which to base specific measures or to establish quality thresholds. A multi-stakeholder group should identify potential metrics, categorize the evidence base for their use, and suggest steps for adoption and implementation. Possible quality indicators include accuracy of image acquisition and processing, timeliness of reporting, the use of a tracking system, the percentage of benign diagnoses among surgically resected nodules, the percentage of nondiagnostic bronchoscopic and CT-guided nodule biopsies, timely diagnosis and treatment of malignant nodules, and complication rates from biopsies and resections. The ATS has previously recommended that measures be subjected to rigorous review and testing before widespread implementation (79). In addition, it will be important to study the implementation process itself to more effectively and efficiently establish the interventions in real-world settings.

Patient-centered Outcomes

Patient centeredness is defined by the Institute of Medicine as care “that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” (80). To conduct innovative patient-centered research, the field should incorporate feedback from diverse stakeholders to understand the unmet needs of patients, their families, and their clinicians. Some patients suffer psychological harm when a pulmonary nodule is discovered during screening (81–85) or incidentally (19, 20, 86, 87). We identified communication processes as the most likely factors that that could be modified to improve patient-centered outcomes. Tools and systems designed to improve communication processes should be evaluated regarding their effect on outcomes important to patients. To ensure these tools are helpful and ultimately used in practice, they should be developed with systematic input from stakeholders.

As a next step to this statement, it would be optimal to form an organized, multi-stakeholder group, similar to the CONCERT effort (88). Like CONCERT, this effort should use formal consensus processes to elicit concerns and unmet needs from multiple stakeholders. The purpose of the group would be to prioritize research and assess the evolving needs of the patient and research community.

Discussion

Our workshop identified many research questions regarding the evaluation of pulmonary nodules. Given the large numbers of patients affected, which is likely to increase with the implementation of lung cancer screening, it is critical to conduct research to answer the most pressing questions.

We developed the following key recommendations:

-

•

The efficacy and effectiveness of new diagnostic strategies (including novel imaging tests and biopsy techniques, biomarkers, and prognostic models) should be evaluated using established phases of test development, from identification of a novel strategy or characteristic to establishment of clinical utility.

-

•

Registries that link demographic and nodule characteristics with patient-level outcomes should be developed.

-

•

Pulmonary nodule evaluation strategies are guided by subsequent treatment options for early-stage lung cancer, and these treatments should be rigorously studied.

-

•

Potential interventions and quality metrics to improve nodule evaluation processes should be studied before requiring their implementation.

-

•

Tests and interventions should be evaluated for their impact on patient-centered outcomes.

There were substantial overlaps in the key research gaps we identified. For instance, participants recognized the need to validate novel prediction models, imaging tests, invasive procedures, and biomarkers. We also agreed that these interventions need to be rigorously evaluated in randomized and/or pragmatic trials for their effects on patient, clinician, and healthcare system outcomes before widespread implementation. The ATS may want to consider how to frame these issues more broadly, because processes related to the evaluation of diagnostic tests and prognostic markers are relevant to many problems in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. This framework would provide actionable criteria for discovery and validation and to assess impact on patient outcomes.

Pulmonary nodules are just one of many incidental findings commonly identified when patients undergo imaging procedures. A recent Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues related to incidental and secondary findings recommended that professional organizations develop guidelines and best management practices; that research efforts should be funded to evaluate the frequency of incidental findings along with their costs, benefits, and harms; and that all affected patients have access to information regarding individualized risks and benefits to make informed decisions (89). Researchers may want to use our framework along with this statement to guide future proposals.

Workshop participants identified the lack of nodule registries as a key barrier to research and quality improvement efforts. The American College of Radiology created the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) to address a similar barrier (90) and could serve as a guide for nodule registries. This system was developed with input from multiple stakeholders, initially to support the needs of clinicians to better understand and use the information contained in radiology reports. We agreed that nodule registries need to be carefully designed and implemented and shown to be useful if they are to be widely adopted.

Limitations

We did not use formal methods to achieve consensus and therefore did not attempt to set priorities. We did not include representatives from health systems, purchasers, or groups that fund research, so inclusion of these stakeholders in future discussions may be helpful. The international participants did not seem to have disparate views, but this report likely does not fully represent the views of stakeholders from other countries. Finally, we included stakeholders from organizations that represent patients who are often identified with a nodule and influenced by lung cancer screening efforts, but there are no readily identifiable organizations that advocate specifically on behalf of patients with pulmonary nodules. We hope that one outcome of this statement is to facilitate the creation of multidisciplinary stakeholder groups that more fully incorporate patient views.

Conclusions

This statement establishes a research framework to address fundamental questions about the care of patients with pulmonary nodules. We engaged clinical and patient stakeholders to address questions of importance. This statement may help researchers develop impactful and innovative proposals and enable funders to better judge novel research proposals. We hope that it will quicken the pace and increase the efficiency of discovery to improve the quality of care for patients with pulmonary nodules.

Acknowledgments

Members of the Writing Committee are as follows:

Christopher G. Slatore, M.D., M.S. (Chair)

Michael K. Gould, M.D., M.S. (Co-Chair)

Nanda Horeweg, M.D., Ph.D.

James R. Jett, M.D.

David E. Midthun, M.D.

Charles A. Powell, M.D.

Renda Soylemez Wiener, M.D., M.P.H.

Juan P. Wisnivesky, M.D., Dr.P.H.

Workshop Attendees:

Doug A. Arenberg, M.D.

David H. Au, M.D., M.S.

Peter B. Bach, M.D., M.A.P.P.

Christine D. Berg, M.D.

Robert L. Keith, M.D.

Bill Clark, B.S.

Harry J. de Koning, M.D., Ph.D.

Frank C. Detterbeck, M.D.

Steve M. Dubinett, M.D.

Barbara M. Fischer, M.D., Ph.D.

Michael K. Gould, M.D., M.S.

Edward A. Hirschowitz, M.D.

Kathy Hopkins, M.S., R.N.

Nanda Horeweg, M.D.

James R. Jett, M.D.

Jerry A. Krishnan, M.D., Ph.D.

Ann N. Leung, M.D.

Pierre P. Massion, M.D.

Peter J. Mazzone, M.D., M.P.H.

David E. Midthun, M.D.

Georgia L. Narsavage, Ph.D., A.P.R.N.

David E. Ost, M.D., M.P.H.

Charles A. Powell, M.D.

Dawn Provenzale, M.D., M.S.

Christopher G. Slatore, M.D., M.S.

Anil Vachani, M.D.

Regina Vidaver, Ph.D.

Renda Soylemez Wiener, M.D., M.P.H.

Avrum Spira, M.D., M.Sc.

Juan P. Wisnivesky, M.D., Dr.P.H.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jerry A. Krishnan, M.D., Ph.D.; Dawn Provenzale, M.D., M.S.; and Avrum Spira, M.D., M.Sc., for their insight and willingness to provide advice during the workshop.

Footnotes

This official Research Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) was approved by the ATS Board of Directors, April 2015

C.G.S. is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDP 11-227) as well as resources and the use of facilities at the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, Oregon.

The Department of Veterans Affairs did not have a role in the conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, or in the preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

Author Disclosures: C.G.S. received research support from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the American Lung Association, and the Radiation Oncology Institute; he was a speaker for the National Lung Cancer Partnership and on an advisory committee pertaining to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services lung cancer screening decisions. J.R.J. received research support from Oncimmune Inc. D.E.M. received research support from Integrated Diagnostics. C.A.P. was a consultant for Pfizer. J.P.W. was a consultant and on an advisory committee for EHE International. M.K.G. received research support from Archimedes and is an author for UpToDate. N.H. and R.S.W. reported no relevant commercial interests.

References

- 1.Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Clinical practice: the solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2535–2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. Raleigh, NC: Lulu; 2008. Dartmouth atlas of health care. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holden WE, Lewinsohn DM, Osborne ML, Griffin C, Spencer A, Duncan C, Deffebach ME. Use of a clinical pathway to manage unsuspected radiographic findings. Chest. 2004;125:1753–1760. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.5.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao VM, Levin DC. The overuse of diagnostic imaging and the Choosing Wisely Initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:574–576. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao VM, Levin DC, Parker L, Frangos AJ, Sunshine JH. Trends in utilization rates of the various imaging modalities in emergency departments: nationwide Medicare data from 2000 to 2008. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8:706–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meer AB, Basu PA, Baker LC, Atlas SW. Exposure to ionizing radiation and estimate of secondary cancers in the era of high-speed CT scanning: projections from the Medicare population. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Lee C, Feigelson HS, Flynn M, Greenlee RT, Kruger RL, Hornbrook MC, Roblin D, et al. Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:2400–2409. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, Azzoli CG, Berry DA, Brawley OW, Byers T, Colditz GA, Gould MK, Jett JR, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307:2418–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, Field JK, Jett JR, Keshavjee S, MacMahon H, Mulshine JL, Munden RF, Salgia R, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN guidelines on lung cancer screening. 2012 [accessed 2012. Jun 27]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/lung_screening.pdf

- 11.Samet JM, Crowell R, San Jose Estepar R, Rand CS, Rizzo AA, Yung R.American Lung Association. Providing guidance on lung cancer screening to patients and physicians. 2012[accessed 2012 Jun 27]. Available from: http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/lung-cancer/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines/lung-cancer-screening.pdf

- 12.Wender R, Fontham ET, Barrera E, Jr, Colditz GA, Church TR, Ettinger DS, Etzioni R, Flowers CR, Gazelle GS, Kelsey DK, et al. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:107–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moyer VA. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks JD National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naidich DP, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, Schaefer-Prokop CM, Pistolesi M, Goo JM, Macchiarini P, Crapo JD, Herold CJ, Austin JH, et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2013;266:304–317. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, Herold CJ, Jett JR, Naidich DP, Patz EF, Jr, Swensen SJ Fleischner Society. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237:395–400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, Mazzone PJ, Midthun DE, Naidich DP, Wiener RS. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e93S–e120S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ost DE, Gould MK. Decision making in patients with pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:363–372. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0679CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slatore CG, Press N, Au DH, Curtis JR, Wiener RS, Ganzini L. What the heck is a “nodule”? A qualitative study of veterans with pulmonary nodules. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:330–335. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201304-080OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slatore CG, Golden SE, Ganzini L, Wiener RS, Au DH. Distress and patient-centered communication among veterans with incidental (not screen-detected) pulmonary nodules: a cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:184–192. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201406-283OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viergever RF, Olifson S, Ghaffar A, Terry RF. A checklist for health research priority setting: nine common themes of good practice. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schalekamp S, van Ginneken B, Koedam E, Snoeren MM, Tiehuis AM, Wittenberg R, Karssemeijer N, Schaefer-Prokop CM. Computer-aided detection improves detection of pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs beyond the support by bone-suppressed images. Radiology. 2014;272:252–261. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bogoni L, Ko JP, Alpert J, Anand V, Fantauzzi J, Florin CH, Koo CW, Mason D, Rom W, Shiau M, et al. Impact of a computer-aided detection (CAD) system integrated into a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) on reader sensitivity and efficiency for the detection of lung nodules in thoracic CT exams. J Digit Imaging. 2012;25:771–781. doi: 10.1007/s10278-012-9496-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y, de Bock GH, Vliegenthart R, van Klaveren RJ, Wang Y, Bogoni L, de Jong PA, Mali WP, van Ooijen PM, Oudkerk M. Performance of computer-aided detection of pulmonary nodules in low-dose CT: comparison with double reading by nodule volume. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:2076–2084. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2437-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szucs-Farkas Z, Patak MA, Yuksel-Hatz S, Ruder T, Vock P. Improved detection of pulmonary nodules on energy-subtracted chest radiographs with a commercial computer-aided diagnosis software: comparison with human observers. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1289–1296. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraioli F, Serra G, Passariello R. CAD (computed-aided detection) and CADx (computer aided diagnosis) systems in identifying and characterising lung nodules on chest CT: overview of research, developments and new prospects. Radiol Med (Torino) 2010;115:385–402. doi: 10.1007/s11547-010-0507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Xu Y, Ma Y, Ma B. Neural network ensemble-based computer-aided diagnosis for differentiation of lung nodules on CT images: clinical evaluation. Acad Radiol. 2010;17:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MC, Boroczky L, Sungur-Stasik K, Cann AD, Borczuk AC, Kawut SM, Powell CA. Computer-aided diagnosis of pulmonary nodules using a two-step approach for feature selection and classifier ensemble construction. Artif Intell Med. 2010;50:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kusano S, Nakagawa T, Aoki T, Nawa T, Nakashima K, Goto Y, Korogi Y. Efficacy of computer-aided diagnosis in lung cancer screening with low-dose spiral computed tomography: receiver operating characteristic analysis of radiologists’ performance. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:649–655. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholten ET, de Hoop B, Jacobs C, van Amelsvoort-van de Vorst S, van Klaveren RJ, Oudkerk M, Vliegenthart R, de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, Mali WT, et al. Semi-automatic quantification of subsolid pulmonary nodules: comparison with manual measurements. Plos One. 2013;8:e80249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cascio D, Magro R, Fauci F, Iacomi M, Raso G. Automatic detection of lung nodules in CT datasets based on stable 3D mass-spring models. Comput Biol Med. 2012;42:1098–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kubota K, Murakami K, Inoue T, Saga T, Shiomi S. Additional effects of FDG-PET to thin-section CT for the differential diagnosis of lung nodules: a Japanese multicenter clinical study. Ann Nucl Med. 2011;25:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s12149-011-0528-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohno Y, Nishio M, Koyama H, Fujisawa Y, Yoshikawa T, Matsumoto S, Sugimura K. Comparison of quantitatively analyzed dynamic area-detector CT using various mathematic methods with FDG PET/CT in management of solitary pulmonary nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:W593-602. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen B, Barnhart H, Richard S, Robins M, Colsher J, Samei E. Volumetric quantification of lung nodules in CT with iterative reconstruction (ASiR and MBIR) Med Phys. 2013;40:111902. doi: 10.1118/1.4823463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nana-Sinkam SP, Powell CA. Molecular biology of lung cancer. Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e30S–e39S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassanein M, Callison JC, Callaway-Lane C, Aldrich MC, Grogan EL, Massion PP. The state of molecular biomarkers for the early detection of lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:992–1006. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Edell ES. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:849–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gould MK, Ananth L, Barnett PG Veterans Affairs SNAP Cooperative Study Group. A clinical model to estimate the pretest probability of lung cancer in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules. Chest. 2007;131:383–388. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, Roberts H, Liu G, Soghrati K, Yasufuku K, Martel S, Laberge F, Gingras M, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:910–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herder GJ, van Tinteren H, Golding RP, Kostense PJ, Comans EF, Smit EF, Hoekstra OS. Clinical prediction model to characterize pulmonary nodules: validation and added value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Chest. 2005;128:2490–2496. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schultz EM, Sanders GD, Trotter PR, Patz EF, Jr, Silvestri GA, Owens DK, Gould MK. Validation of two models to estimate the probability of malignancy in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules. Thorax. 2008;63:335–341. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.084731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balekian AA, Silvestri GA, Simkovich SM, Mestaz PJ, Sanders GD, Daniel J, Porcel J, Gould MK. Accuracy of clinicians and models for estimating the probability that a pulmonary nodule is malignant. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:629–635. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-107OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. The efficacy of diagnostic imaging. Med Decis Making. 1991;11:88–94. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9101100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson ML, Thornquist M, Winget M, Yasui Y. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pepe MS, Feng Z, Janes H, Bossuyt PM, Potter JD. Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1432–1438. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schully SD, Carrick DM, Mechanic LE, Srivastava S, Anderson GL, Baron JA, Berg CD, Cullen J, Diamandis EP, Doria-Rose VP, et al. Leveraging biospecimen resources for discovery or validation of markers for early cancer detection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv012. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerr KF, Wang Z, Janes H, McClelland RL, Psaty BM, Pepe MS. Net reclassification indices for evaluating risk prediction instruments: a critical review. Epidemiology. 2014;25:114–121. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vachani A, Tanner NT, Aggarwal J, Mathews C, Kearney P, Fang KC, Silvestri G, Diette GB. Factors that influence physician decision making for indeterminate pulmonary nodules. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1586–1591. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201405-197BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gopalakrishna G, Langendam MW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Leeflang MM. Guidelines for guideline developers: a systematic review of grading systems for medical tests. Implement Sci. 2013;8:78. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gopalakrishna G, Mustafa RA, Davenport C, Scholten RJ, Hyde C, Brozek J, Schünemann HJ, Bossuyt PM, Leeflang MM, Langendam MW. Applying Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) to diagnostic tests was challenging but doable. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazzone P, Powell CA, Arenberg D, Bach P, Detterbeck F, Gould M, Jaklitsch MT, Jett J, Naidich D, Vachani A, et al. Components necessary for high-quality lung cancer screening: American College of Chest Physicians and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Chest. 2015;147:295–303. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen TS, Chin J, Ashby L, Hermansen J, Hutter JD.Decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (cag-00439n). 2015 [accessed 2015. Feb 6]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274

- 53.Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Dann E, Black WC. Using radiology reports to encourage evidence-based practice in the evaluation of small, incidentally detected pulmonary nodules: a preliminary study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:211–214. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-242BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McKee BJ, Regis SM, McKee AB, Flacke S, Wald C. Performance of ACR lung-rads in a clinical ct lung screening program. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:273–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American College of Radiology. Lung CT screening reporting and data system (Lung-RADS) [accessed 2015. Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Resources/LungRADS

- 56.Danforth KN, Early MI, Ngan S, Kosco AE, Zheng C, Gould MK. Automated identification of patients with pulmonary nodules in an integrated health system using administrative health plan data, radiology reports, and natural language processing. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1257–1262. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31825bd9f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Cancer Institute. SEER-medicare: Medicare claims files. 2011 [accessed 2011 Dec 28]. Available from: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/medicare/claims.html

- 58.Kinsinger LS, Atkins D, Provenzale D, Anderson C, Petzel R. Implementation of a new screening recommendation in health care: the Veterans Health Administration’s approach to lung cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:597–598. doi: 10.7326/M14-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carson SS, Goss CH, Patel SR, Anzueto A, Au DH, Elborn S, Gerald JK, Gerald LB, Kahn JM, Malhotra A, et al. American Thoracic Society Comparative Effectiveness Research Working Group. An official American Thoracic Society research statement: comparative effectiveness research in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1253–1261. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1790ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yarmus LB, Akulian J, Lechtzin N, Yasin F, Kamdar B, Ernst A, Ost DE, Ray C, Greenhill SR, Jimenez CA, et al. American College of Chest Physicians Quality Improvement Registry, Education, and Evaluation (AQuIRE) Participants. Comparison of 21-gauge and 22-gauge aspiration needle in endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: results of the American College of Chest Physicians Quality Improvement Registry, Education, and Evaluation Registry. Chest. 2013;143:1036–1043. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krishnan JA, Lindenauer PK, Au DH, Carson SS, Lee TA, McBurnie MA, Naureckas ET, Vollmer WM, Mularski RA COPD Outcomes-based Network for Clinical Effectiveness and Research Translation. Stakeholder priorities for comparative effectiveness research in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a workshop report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:320–326. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-0994WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium [accessed 2015. Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.golcmc.com/

- 63.Early Detection Research Network [accessed 2015. Jul 22]. Available from: http://edrn.nci.nih.gov/

- 64.Cooke CR, Gould MK. Advancing clinical practice and policy through guidelines: the role of the American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:910–914. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0009PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:55–63. doi: 10.7326/M14-0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moons KGM, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, Ioannidis JPA, Macaskill P, Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Ransohoff DF, Collins GS. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:W1–73. doi: 10.7326/M14-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, Balekian AA, Murthy SC. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer. Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e278S–313S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Timmerman RD, Herman J, Cho LC. Emergence of stereotactic body radiation therapy and its impact on current and future clinical practice. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2847–2854. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rutter CE, Corso CD, Park HS, Mancini BR, Yeboa DN, Lester-Coll NH, Kim AW, Decker RH. Increase in the use of lung stereotactic body radiotherapy without a preceding biopsy in the United States. Lung Cancer. 2014;85:390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Louie AV, Senan S, Patel P, Ferket BS, Lagerwaard FJ, Rodrigues GB, Salama JK, Kelsey C, Palma DA, Hunink MG. When is a biopsy-proven diagnosis necessary before stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for lung cancer?: a decision analysis. Chest. 2014;146:1021–1028. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Keith RL. Lung cancer chemoprevention. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9:52–56. doi: 10.1513/pats.201107-038MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szabo E, Mao JT, Lam S, Reid ME, Keith RL. Chemoprevention of lung cancer. Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e40S–60S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, Dickerson J, Adams D, Stevens SM, Woller SC, Evans RS, Elliott CG. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiener RS, Gould MK, Slatore CG, Fincke BG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Resource use and guideline concordance in evaluation of pulmonary nodules for cancer: too much and too little care. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:871–880. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blackwood B, Murray M, Chisakuta A, Cardwell CR, O’Halloran P. Protocolized versus non-protocolized weaning for reducing the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation in critically ill paediatric patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD009082. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009082.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD008743. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008743.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kruis AL, Smidt N, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J, Boland MR, Rutten-van Mölken M, Chavannes NH. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD009437. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009437.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Proposed decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N) [accessed 2015. Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-proposed-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274