Abstract

Background: Measuring free drug concentration following systemic administration of a liposomal drug is a crucial aspect of the assessment of its in vivo behavior. Therefore we require an efficient method to separate free drug in the plasma from encapsulated drug. Objectives: To study the pharmacokinetics of free doxorubicin (DOX) released from liposomal doxorubicin (L-DOX) in rats. Methods: L-DOX was prepared with encapsulation efficiency of 90% and was injected intravenously into rats. A solid-phase extraction (SPE) method coupled with UPLC–MS/MS was used to measure the concentration of F-DOX in rat plasma without disrupting the integrity of L-DOX. Results: This method exhibited a linear range of F-DOX from 0.2 to 200 ng/mL. Recovery, precision, linearity and accuracy of this technique appear satisfactory for pharmacokinetic study. The constituents of F-DOX ranged from 5.35% to 14.09% of total DOX in plasma at each time point measured after L-DOX administration. Conclusion: SPE method was suitable for studying the pharmacokinetics of F-DOX in rats receiving L-DOX.

Keywords: Pharmacokinetics, Doxorubicin, Liposomes, Solid-phase extraction

1. Introduction

Doxorubicin (DOX) is an anthracycline chemotherapeutic drug that possesses broad spectrum anti-tumor activity (Young et al., 1981). It effectively resisted a variety of malignancies including gastric cancer, acute leukemia, small-cell lung cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, lymphoma, and breastcarcinoma. Unfortunately, DOX causes myocardium damage that is cumulative and irreversible (Tao et al., 2016, Chatterjee et al., 2010, Xie et al., 2016, Zaheer et al., 2017). This side reaction is particularly serious about children. In clinical practice, the cumulative dose of DOX must be limited to reduce cardiotoxicity (Rahman et al., 2007, Zaidi et al., 2017).

Liposomes are phospholipid bilayer vesicles, which can be used as delivery vehicles for chemotherapeutics (Tahover et al., 2015, Gohar et al., 2017). Liposomal DOX (L-DOX), particularly pegylated L-DOX, have shown significant therapeutic advantages. Studies have shown that L-DOX has lower toxicity and equivalent or higher anti-tumor effects compared to free DOX (F-DOX). Because only F-DOX has toxicological and pharmacological effects, understanding its pharmacokinetics (PK) can potentially lead to relatively precise prediction of the toxicity and efficacy of L-DOX in vivo (Liu et al., 2016, Richly et al., 2009, Muhammad et al., 2017).

Previous pharmacokinetic studies on L-DOX have mostly focused on the total DOX (T-DOX), which is the sum of F-DOX and encapsulated DOX (E-DOX). To study the concentration of F-DOX in the plasma, a reliable method is needed to separate free drug from liposomes while preventing drug leakage from the liposomes (Chen et al., 2016, Hilger et al., 2005).

Here, we describe a method for extracting and quantifying F-DOX in the plasma of rats treated with L-DOX. This method was based upon the finding that liposomes can pass through solid-phase C18 silica gel cartridges without being absorbing, but F-DOX is retained on the stationary phase.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

DOX (purity 99.6%) and daunorubicin (purity 99.7%) were obtained from Zhejiang HISUN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Cholesterol and Hydrogenated soybean phospholipids (HSPC) were obtained from Sinopharm group Co. Ltd. Distearoyl phosphatidylethanolamine-PEG2000 (DSPE-PEG200) was purchased from Xi’an Ruixi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, and formic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Animals

Male Wistar rats (275 ± 5 g) were purchased from Jilin University Animal Experiment Center. Animals were fed in a well-ventilated environment under the standard of illumination, temperature and humidity. Food and water were sufficiently supplied and allowed them to adapt the laboratory environment for at least one week. The rats were fasted 12 h with free water before administration. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Jilin University.

2.3. Preparation of L-DOX

L-DOX had a lipid composition of HSPC/cholesterol/DSPE-PEG2000 (11:8:1 mol/mol). Doxorubicin liposomes was prepared by remote loading, which was driven by transmembrane (NH4)2SO4 gradient (Iftakhar et al., 2015, Fritze et al., 2006). The concentration of DOX in the liposomes was 2 mg/mL. The encapsulation efficiency of DOX liposomes was determined using a Sephadex G50 size exclusion column.

2.4. Analysis of DOX concentration

A UPLC-MS/MS system was used to analyze the concentration of DOX. The system consists of an ACQUITY UPLC® system from Waters Corp (Milford, MA, USA) coupled a Xevo TQ-S triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters) with an ESI source at the positive mode. The mobile phase was run with mobile phase ‘A’ (water/0.1% formic acid) and mobile phase ‘B’ (acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid) under a 0.4 mL/min flow rate through a C18 column (2.1 ∗ 50 mm, 1.7 μm) (Waters Corp, Milford, MA, USA) (Liu et al., 2008). A linear gradient was: mobile phase ‘A’ linear increased to 70% from 10% within 2.5 mins followed by maintaining 70% for 1 min. And then the mobile phase immediately return to initial mobile phase to equilibrate column for 1.5 min, resulting in a total run time of 5 mins. The temperature of column and auto-sampler temperature were kept at 30 and 10 °C. Five μL sample was injected into UPLC-MS/MS system to analyze.

DOX and the internal standard (IS) (daunorubicin) were detected as charged ions: m/z 544.20 → 397.21 and m/z 528.18 → 321.19 (Zhang et al., 2014), respectively. The mass spectrometer conditions were: source temperature 150 °C, cone voltage 30V, capillary voltage 3 kV, and desolvation temperature 500 °C. The desolvation, cone, and collision (Argon) gas flow rates were 1000, 150 L/h and 0.17 mL/min, respectively. The collision energy was optimized as 5 V for DOX and IS. Data was performed using Mass Lynx software (version 4.1).

2.5. Preparation of stock solution, calibration standard, and quality control samples

Total DOX (T-DOX) stock solutions consisted of F-DOX and E-DOX. The fraction of E-DOX was above 90%. The stock solutions of F-DOX and T-DOX were diluted by blank plasma to establish calibration curves at DOX concentrations of 0.2, 1, 2, 20, 40, 100, 160, or 200 ng/mL. Daunorubicin at 20 ng/mL was used as an IS. DOX concentrations of 160, 40, 1 ng/mL were used as higher quality control (HQC), middle quality control (MQC) and lower quality control (LQC), respectively.

2.6. Method validation

The validation of this method was evaluated by FDA guidelines for bioanalytical method validation, including: selectivity, recovery, matrix effect criteria, calibration curve, precision and accuracy, stability of the sample at various test or storage conditions and dilution integrity.

2.7. Separation and extraction of plasma F-DOX and T-DOX

F-DOX in plasma was separated from E-DOX using SPE method by an Oasis HLB column (Waters) (Sottani et al., 2013). First, 50 μL plasma sample containing IS (20 ng/mL) was loaded without vacuum. The HLB column was then cleaned by 1 mL of water, and then eluted with 1 mL of methanol containing 2% acetic acid in order to elute F-DOX adsorbed to the HLB column. The eluted solution was dried with nitrogen at 37 °C and the residue was resuspended with 100 μL of the initial mobile phase.

Liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) was used to extract T-DOX in plasma: 200 μL 6% (w/v) borate buffer (pH 9.5) was added into 50 μL plasma sample containing IS (20 ng/mL) (van Asperen et al., 1998), The analytes were extracted 2 min using 1 mL of chloroform/1-propanol (4:1, v/v) under mixing, and then centrifgued for 10 min at 2827 g and 20 °C. The organic layer was dried with nitrogen at 37 °C and the residue was reconstituted with 100 μL initial mobile phase.

2.8. UPLC analyses

It was necessary to demonstrate that solid-phase extraction (SPE) was appropriate for the separation of F-DOX from E-DOX. It was evaluated by the percentage of F-DOX (F%) in the samples. T-DOX in L-DOX consisted of F-DOX and E-DOX, the fraction of F-DOX was about 10%. The F% value was calculated following the equation: F% = CF/C0 × 100% (Yang et al., 2013), where CF is the concentration of F-DOX in QCs and C0 is the nominal concentration of T-DOX. The value of CF may be the sum of F-DOX originally exist in the L-DOX QCs sample, as well as the DOX released from E-DOX in the process of extraction or mixing with plasma. For further researching the integrity of liposomal in the extraction process, the liposomal fractions were washed with 200 μL waters and re-run through a new HLB column. The following value of CF2 after operating sample through a new HLB would represent the concentration of F-DOX releasing from liposomal. Theoretically, the value of F% after two-step extraction (F2%) should be very low if the HLB column could separate F-DOX from E-DOX without damaging the liposomes during the extraction procedure and the F- DOX was completely recovered by HLB column in one step (Deshpande et al., 2010).

If the extraction procedure damaged the liposomes, the method cannot be used to accurately appraise F-DOX in plasma. We have verified liposome integrity during the extraction process as follows. After the first run of L-DOX spiked into blank plasma through HLB column, the liposomal fraction was collected in 1.5 mL polypropylene tube, the liposomal fractions were suggested to 3 cycles of freeze/thaw, or vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged 1078g for 10 min at 20 °C, and re-run through a newly HLB column. Processing Stabilities were assessed by F2% (Bellott et al., 2001).

2.9. PK study

The rats received a single dose 1.45 mg/kg of L-DOX or 0.145 mg/kg of DOX intravenously. At 10 min, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96, 108, 120, 132, 144, 168, 180 and 192 h, the plasma was harvested from rats. The blood samples were centrifuged immediately at 1078g for 10 min to obtain plasma. The plasma samples of L-DOX-treated rats were divided into two portions: one was used to measure the T-DOX concentration, the other to determine the concentration of F-DOX (Zhang et al., 2011). Pharmacokinetic parameter analysis was calculated by a noncompartmental approach (WinNolin software version 5.2, Pharsight, Mountain View, CA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Extraction procedure and method optimization

A challenge in developing sample extraction method was separation of F-DOX from E-DOX. An HLB cartridge was selected for this purpose based upon the finding that free drug can be retained on the stationary phase, while liposomes can pass through reversed-phase silica gel cartridges without being absorbed. A potential risk is liposome leakage due to exposure to vortex, organic solvent, centrifugation, HLB resin, and especially at elevated temperature.

The solubility of DOX is dependent on pH (Forner et al., 2014, Nawaz et al., 2017, Feng et al., 2016). Therefore, borate buffer was added to enhance the solubility of DOX, which also altered the oil-water partition coefficient of DOX. On the other hand, it is necessary to release the DOX from L-DOX completely to measure the T-DOX. Liposomes could be completely destroyed by organic solvent to release free DOX. Addition of 1 mL of chloroform/1-propanol (4:1, v/v) was found to destroy L-DOX, precipitate plasma proteins, and to extract DOX from the matrix with high recovery (Samad et al., 2017).

3.2. Method validation

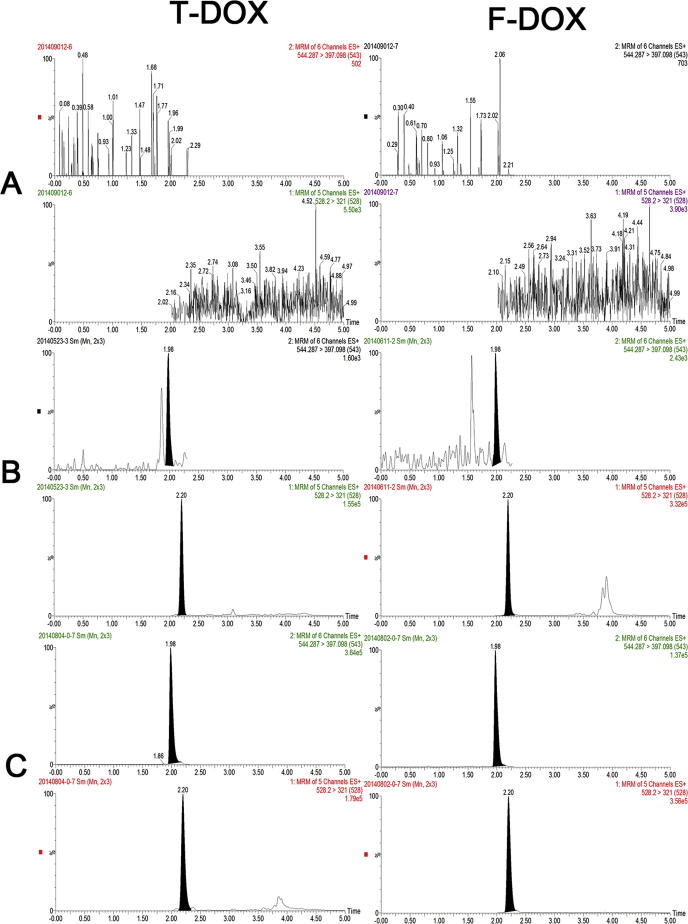

There was no obvious interference of the blank plasma sample at the retention times of the DOX and IS. The retention time of DOX and IS were 1.98mins and 2.20mins, respectively. The calibration curves were validated at the concentration range of 0.2–200 ng/mL for T-DOX and F-DOX in plasma to fit with weighting factors 1/x2. The least-squares linear regression constants (r2) were greater or equal to 0.99. The method specificity of measuring F-DOX and T-DOX were shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The chromatograms of F-DOX, T-DOX and IS. (A) A blank plasma sample without DOX and IS adding; (B) the LLOQ sample (0.2 ng/mL for F-DOX and 0.2 ng/mL for T-DOX); (C) a real plasma sample collected after intravenous administration of 1.45 mg kg−1 L-DOX 24 h.

The intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy of the method were evaluated using three different concentrations QCs and the results are summarized in Table 1. Dilution accuracy of T-DOX and F-DOX were evaluated. Accuracy and RSD% were 97.75% and 9.22% at a dilution factor of 100, respectively. The accuracy and RSD% of F-DOX were 100% and 7.25%, at a dilution factor of 20, respectively.

Table 1.

Intra- and inter-day precision and accuracy.

| Intra-day (n = 6) |

Inter-day (n = 18) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-DOX | LQC | MQC | HQC | LQC | MQC | HQC |

| Nominal conc. (ng/mL) | 1 | 40 | 160 | 1 | 40 | 160 |

| Mean | 0.905 | 36.01 | 153.86 | 0.9 | 37.66 | 153.23 |

| Precision (RSD %) | 9.74 | 4.94 | 5.98 | 4.82 | 9.51 | 4.44 |

| Accuracy (RE %) | −9.5 | −10 | −3.8 | −10 | −5.85 | −4.23 |

| F-DOX | LQC | MQC | HQC | LQC | MQC | HQC |

| Nominal conc. (ng/mL) | 1 | 40 | 160 | 1 | 40 | 160 |

| Mean | 1.042 | 39.97 | 167.27 | 1.044 | 39.9 | 160.74 |

| Precision (RSD %) | 9.08 | 4.45 | 4.65 | 2.95 | 1.05 | 8.62 |

| Accuracy (RE %) | 4.2 | −0.1 | 4.5 | 4.44 | −0.25 | 0.46 |

F-DOX was stable at 25 °C for 4 h and at 10 °C for 12 h when kept in the auto-sampler. T-DOX was stable under conditions as follows: at 25 °C for 4 h; at 10 °C for 12 h when kept in the auto-sampler; stored at −70 °C for 2 months; or after 3 freeze/thaw cycles (from −70 °C to 25 °C). The stability results of F-DOX and T-DOX are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Stability results of QC samples at different conditions (n = 6).

| Stability tests | Theoretical conc. (ng/mL) | Found conc. (ng/mL) | Precision (RSD %) | Accuracy (RE %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-DOX | |||||

| Short term | LQC | 0.905 | 1.03 | 10.11 | 13.81 |

| MQC | 36.01 | 35.59 | 4.79 | −1.15 | |

| HQC | 153.86 | 152.77 | 4.77 | −0.71 | |

| Auto-sampler | LQC | 0.905 | 1.03 | 10.22 | 14.18 |

| MQC | 36.01 | 35.54 | 4.89 | −1.29 | |

| HQC | 153.86 | 146.95 | 8.33 | −4.49 | |

| Freeze-thaw | LQC | 0.905 | 0.92 | 6.84 | 1.84 |

| MQC | 36.01 | 40.22 | 5.01 | 11.7 | |

| HQC | 153.86 | 150.15 | 2.96 | −2.41 | |

| Long term | LQC | 0.905 | 0.967 | 7.42 | 6.81 |

| MQC | 36.01 | 38.9 | 3.04 | 8.03 | |

| HQC | 153.86 | 156.22 | 3.49 | 1.53 | |

| F-DOX | |||||

| Short term | LQC | 1.04 | 1.07 | 9.75 | 3.04 |

| MQC | 39.97 | 41.66 | 3.85 | 4.22 | |

| HQC | 167.27 | 166.76 | 3.48 | −0.30 | |

| Auto-sampler | LQC | 1.04 | 0.96 | 11.07 | −7.68 |

| MQC | 39.97 | 40.2 | 3.8 | 0.55 | |

| HQC | 167.27 | 167.86 | 6.02 | 0.35 | |

The extraction recoveries were 83.48%, 81.11%, 85.00% for F-DOX and 83.41%, 75.16%, 88.05% for T-DOX at LQCs, MQCs and HQC (n = 6). Matrix effects were 79.35%, 96.77%, 94.03% for F-DOX and 84.22%, 75.36%, 59.27% for T-DOX at LQCs, MQCs and HQCs (n = 6), respectively. Matrix effects of IS were observed 91.67% and 60.75% by HLB and LLE method extraction, respectively. The RSD% was less than 15%.

3.3. Method feasibility

The three levels of QCs of L-DOX solution (n = 6) were extracted using HLB method and quantified concentration. The percentage of F-DOX (F2%) in HQC, MQC and LQC samples after two-step extraction were 2.05%, 1.53% and 0, respectively. Because of the recovery of F-DOX was only about 80%, so the theoretical value of F2% was about 2% when liposomes are not destroyed. It was negligible that the value of F2% compared to the percent of F-DOX originally exist in L-DOX. Thus, the results showed that HLB can efficiently separate E-DOX and F-DOX in plasma.

The values of (F2%) were 0, 2.18% and 2.31% at three QC levels, respectively, showing little liposome leakage during vortex for 1 min and centrifugation of the blood at 1078g for 10 min at 25 °C. The values of (F2%) were 0, 2.93% and 3.63% at three QC levels, respectively, after liposome was subjected to 3 freeze/thaw cycles. These data show that centrifugation and vortex are safe for liposome integrity, whereas freeze-thaw cycles had a small effect on the integrity of liposomes. The feasibility results were summarized in Table 3, Table 4.

Table 3.

Feasibility results of HLB and LLE method.

| HLB (n = 6) | LQC | MQC | HQC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal conc. (ng/mL) | 1 | 40.00 | 160.00 |

| Mean of CF2 (ng/mL) | Naa | 0.61 | 3.28 |

| Mean of F2% | Nab | 1.53 | 2.05 |

| RSD % | Nab | 14.82 | 6.67 |

No response.

Not applicable.

Table 4.

The liposome integrity under different conditions.

| Centrifugation (n = 6) | LQC | MQC | HQC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal conc. (ng/mL) | 1 | 40 | 160 |

| Mean of CF2 (ng/mL) | Naa | 0.87 | 3.69 |

| Mean of F2% | Nab | 2.18 | 2.31 |

| RSD % | Nab | 14.93 | 5.79 |

| 3 freeze/thaw (n = 6) | |||

| Nominal conc. (ng/mL) | 1 | 40 | 160 |

| Mean of CT (ng/mL) | Naa | 1.17 | 5.81 |

| Mean of F2% | Nab | 2.93 | 3.63 |

| RSD % | Nab | 10.64 | 12.90 |

No response.

Not applicable.

3.4. PK of E-DOX and F-DOX in plasma after DOX or L-DOX administration

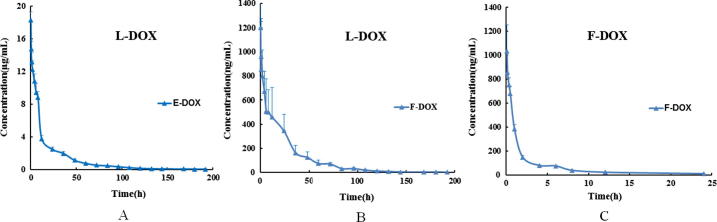

The plasma concentration-time curves of E-DOX and F-DOX are presented in Fig. 2. The PK parameters were evaluated by noncompartment model and the results were shown in Table 5.

Fig. 2.

the concentration-time profiles of E-DOX and F-DOX in plasma after DOX or L-DOX administration. (A) concentration-time curve of E-DOX after 1.45 mg/kg L-DOX administration, (B) concentration-time curve of F-DOX after 1.45 mg/kg L-DOX administration, (C) concentration-time curve of F-DOX after 0. 145 mg/kg DOX administration.

Table 5.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of E-DOX and F-DOX in plasma after administration of 0.145 mg/kg DOX or 1.45 mg/kg L-DOX in rats (mean ± SD, n = 5).

| Parameters | E-DOX after 1.45 mg/kg L-DOX administration | F-DOX after 1.45 mg/kg L-DOX administration | F-DOX after 0.145 mg/kg DOX administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1/2 (h) | 23.42 ± 2.34 | 22.97 ± 2.55 | 8.89 ± 0.11 |

| V (mL) | 53.51 ± 15.17 | – | 270.14 ± 12.20 |

| CL (mL/h) | 1.57 ± 0.31 | – | 21.08 ± 1.17 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 20438.29 ± 2752.22 | 1474.74 ± 944.45 | 1285.38 ± 347.21 |

| AUClast (ng h/mL) | 235495.16 ± 43790.35 | 20953.20 ± 6583.41 | 1764.94 ± 101.30 |

The PK profile of E-DOX in rat following a 1.45 mg/kg i.v. of L-DOX indicated a CL of 1.57 mL/h and V of 53.51 mL. The AUClast was found to be 235495.16 ng h/mL and the T1/2 was 23.42 h. These values were accrod with previous study of reduced rate of clearance and limited distribution of L-DOX (Juliano et al., 1978).

The PK profile of F-DOX in rats following a 1.45 mg/kg i.v. dose of L-DOX indicated an AUClast of 20953.20 ng h/mL and the T1/2 was 22.97 h. The parameters T1/2 of F-DOX were similar to those of E-DOX, so we speculated that F-DOX was drug released from L-DOX, and the AUC0–192h of F-DOX was only 8.9% of E-DOX following L-DOX administration. The fractions of F-DOX in plasma ranged from 5.35% to 14.09% of T-DOX at each time point measured after L-DOX administration.

The PK profile of F-DOX in rat following a 0.145 mg/kg i.v. injection of DOX indicated a CL of 21.08 mL/h and V of 270.14 mL. The AUClast was found to be 1764.94 ng h/mL and the T1/2 was 8.89 h. The AUClast of F-DOX after 1.45 mg/kg L-DOX administration was approximately 11.88 times that following 0.145 mg/kg DOX administration. As mentioned above, we have prepared L-DOX with 90% encapsulation efficiency. As a result, a dose of 1.45 mg/kg L-DOX contained 0.145 mg/kg (10%) of F-DOX. Therefore, the initial concentration of F-DOX in L-DOX and DOX infusion was similar.

4. Conclusion

L-DOX in this study has the same composition as Doxil®, which is a listed drug for treatment of metastatic breast cancer and oophoroma. Recently there has been much interest in the development of generic versions of Doxil. PK studies are critical in establishing bioequivalence of liposomal formulations.

Most studies of the liposomal drugs PK were only determination the total plasma-drug concentrations. However, the total drug concentration may not be related to the pharmacological responses and toxicological. The concentration of free drug in the plasma was often closely related to toxicity or response. To accurately measure free drug concentration following L-DOX administration, it is crucial to separate F-DOX and E-DOX without damaging the liposomes. In this study we developed a sensitive, selective, fast and reliable solid phase extraction (SPE) method to quantify F-DOX in plasma. This method could been applied to study the PK profiles of F-DOX in rats after a single dose L-DOX administration and can potentially be valuable in clinical bioequivalence studies required for developing generic L-DOX formulations.

Funding sources

None.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Yaping Tian, Email: Yapingtian@163.com.

Jing Xie, Email: xiejing@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- Bellott R., Pouna P., Robert J. Separation and determination of liposomal and non-liposomal daunorubicin from the plasma of patients treated with Daunoxome. J. Chromatogr. B. 2001;757(2):257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee K., Zhang J., Honbo N., Karliner J.S. Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology. 2010;115(2):155–162. doi: 10.1159/000265166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Gao Y., Ashraf M.A., Gao W. Effects of the traditional chinese medicine dilong on airway remodeling in rats with OVA-induced-asthma. Open Life Sci. 2016;11(1):498–505. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande N.M., Gangrade M.G., Kekare M.B., Vaidya V.V. Determination of free and liposomal Amphotericin B in human plasma by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy with solid phase extraction and protein precipitation techniques. J. Chromatogr. B. 2010;878(3–4):315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Ashraf M.A., Peng L. Characterization of particle shape, zeta potential, loading efficiency and outdoor stability for chitosan-ricinoleic acid loaded with rotenone. Open Life Sci. 2016;11(1):380–386. [Google Scholar]

- Forner A., Gilabert M., Bruix J., Raoul J.-L. Treatment of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014;11(9):525–535. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritze A., Hens F., Kimpfler A., Schubert R., Peschka-Suess R. Remote loading of doxorubicin into liposomes driven by a transmembrane phosphate gradient. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembranes. 2006;1758(10):1633–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohar S., Abbas G., Sajid S., Sarfraz M., Ali1 S., Ashraf M., Aslam R., Yaseen K. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from raw milk and dairy products. Mat. Sci. Med. 2017;1(1):10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hilger R.A., Richly H., Grubert M., Oberhoff C., Strumberg D., Scheulen M.E., Seeber S. Pharmacokinetics (PK) of a liposomal encapsulated fraction containing doxorubicin and of doxorubicin released from the liposomal capsule after intravenous infusion of Caelyx/Doxil. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;43(12):588–589. doi: 10.5414/cpp43588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iftakhar A., Hasan I.J., Sarfraz M., Jafri L., Ashraf M.A. Nephroprotective effect of the leaves of aloe barbadensis (Aloe Vera) against toxicity induced by diclofenac sodium in albino rabbits. West Indian Med. J. 2015;64(5):462–467. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2016.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano R.L., Stamp D., McCullough N. Pharmacokinetics of liposome-encapsulated antitumor drugs and implications for therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1978;308:411–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb22038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.K., Gao P., Ashraf M.A., Wen J.B. The complete mitochondrial genomes of two weevils, Eucryptorrhynchus chinensis and E. brandti: conserved genome arrangement in Curculionidae and deficiency of tRNA-Ile gene. Open Life Sci. 2016;11(1):458–469. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yang Y., Liu X., Jiang T. Quantification of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and doxorubicinol in rat plasma by liquid chromatography/electro spray tandem mass spectroscopy: application to preclinical pharmacokinetic studies. Talanta. 2008;74(4):887–895. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad G., Rashid I., Firyal S. Practical aspects of treatment of organophosphate and carbamate insecticide poisoning in animals. Mat. Sci. Pharma. 2017;1(1):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz S., Shareef M., Shahid H., Mushtaq M., Sajid S., Sarfraz M. Lipid lowering effect of synthetic phenolic compound in a high- fat diet (HFD) induced hyperlipidemic mice. Mat. Sci. Pharma. 2017;1(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A.M., Yusuf S.W., Ewer M.S. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and the cardiac-sparing effect of liposomal formulation. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2007;2(4):567–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richly H., Grubert M., Scheulen M.E., Hilger R.A. Plasma and cellular pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin after intravenous infusion of Caelyx (TM)/Doxil (R) in patients with hematological tumors. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;47(1):55–57. doi: 10.5414/cpp47055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samad A.N.S., Amid A., Jimat D.N., Shukor A.N.A. Isolation and identification of halophilic bacteria producing halotolerant protease. Galeri Warisan Sains. 2017;1(1):07–09. [Google Scholar]

- Sottani C., Poggi G., Melchiorre F., Montagna B., Minoia C. Simultaneous measurement of doxorubicin and reduced metabolite doxorubicinol by UHPLC-MS/MS in human plasma of HCC patients treated with TACE. J. Chromatogr. B. 2013;915:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahover E., Patil Y.P., Gabizon A.A. Emerging delivery systems to reduce doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and improve therapeutic index: focus on liposomes. Anticancer Drugs. 2015;26(3):241–258. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X., Ashraf M.A., Zhao Y. Paired observation on light-cured composite resin and nano-composite resin in dental caries repair. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016;29(6):2169–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Asperen J., van Tellingen O., Beijnen J.H. Determination of doxorubicin and metabolites in murine specimens by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B. 1998;712(1–2):129–143. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H., Huang H., He W., Fu Z., Luo C., Ashraf M.A. Research on in vitro release of Isoniazid (INH) super paramagnetic microspheres in different magnetic fields. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016;29(6):2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Wang H., Liu M., Hu P., Jiang J. Determination of free and total vincristine in human plasma after intravenous administration of vincristine sulfate liposome injection using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1275:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R.C., Ozols R.F., Myers C.E. The anthracycline antineoplastic drugs. New Engl. J. Med. 1981;305(3):139–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107163050305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi N.A., Hamid A.A.A., Hamid T.A.T.H. Lactic acid bacteria with antimicrobial properties isolated from the instestines of Japanese quail (Coturnix Coturnix Japonica) Galeri Warisan Sains. 2017;1(1):10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer Z., Rahman U.S., Zaheer I., Abbas G., Younas T. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in poultry – an emerging concern related to future epidemic. Mat. Sci. Medica. 2017;1(1):15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Hu X., Song F., Liu Z., Xie Z., Jing X. Studies on the biological character of a new pH-sensitive doxorubicin prodrug with tumor targeting using a LC-MS/MS method. Anal. Meth. 2014;6(9):3159–3166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Sun J., Feng Z., Su X., Zhu M., Sui X., Liu Y., Tao M., Sun Y., Chen G., He Z. Quantification of doxorubicin in pegylated polymer micelles in rat plasma by methanol precipitation-ultrasonic emulsion breaking method and UPLC-MS-MS. Chromatographia. 2011;74(3–4):333–340. [Google Scholar]