Abstract

In addition to expediting patient recovery, community gardens that are associated with medical facilities can provide fresh produce to patients and their families, serve as a platform for clinic-based nutrition education, and help patients develop new skills and insights that can lead to positive health behavior change. While community gardening is undergoing resurgence, there is a strong need for evaluation studies that employ valid and reliable measures. The objective of this study was to conduct a process evaluation of a community garden program at an urban medical clinic to estimate the prevalence of patient awareness and participation, food security, barriers to participation, and personal characteristics; garden volunteer satisfaction; and clinic staff perspectives in using the garden for patient education/treatment. Clinic patients (n=411) completed a community garden participation screener and a random sample completed a longer evaluation survey (n=152); garden volunteers and medical staff completed additional surveys. Among patients, 39% had heard of and 18% had received vegetables from the garden; the greatest barrier for participation was lack of awareness. Volunteers reported learning about gardening, feeling more involved in the neighborhood, and environmental concern; and medical staff endorsed the garden for patient education/treatment. Comprehensive process evaluations can be utilized to quantify benefits of community gardens in medical centers as well as to point out areas for further development, such as increasing patient awareness. As garden programming at medical centers is formalized, future research should include systematic evaluations to determine whether this unique component of the healthcare environment helps improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: gardening, urban health, process evaluation, community gardens, agriculture

Introduction

More than two decades of research suggests that patients who can enjoy the view of a garden outside their hospital window, and those who can go outside and experience nature first-hand, heal more quickly and experience marked psychological benefits when compared to those not exposed to a natural environment [1-5]. In addition to expediting patient recovery, gardens that are associated with medical facilities can provide fresh produce to patients and their families, can serve as a platform for clinic-based nutrition education, and may help patients develop new skills and insights that can lead to positive health behavior change. Such changes to the healthcare environment could potentially improve the health of patients, staff and the surrounding community.

Community gardens at medical facilities that supplement the diets of their patients with fresh produce may also help reduce instances of food insecurity by helping stretch food dollars [6-8]. Unchanged since 2008, approximately 14.0% of US households reported food insecurity at least some time during the year in 2013, and 5.6% reported very low food security [9]. Rates of food insecurity were substantially higher than the national average for households near or below the Federal poverty line, households located in nonmetropolitan areas and in the Southeastern US, households with children headed by single women or single men, and Black and Hispanic households [9-11]. Although meeting dietary recommendations is challenging for the general population, when compared to non-gardeners, community gardeners report consuming more servings of fruits and vegetables and are more likely to meet national dietary recommendations to consume at least five servings of fruits and vegetables each day [12-15]. In addition to changes in individual-level behaviors, community gardens may also promote community cohesion, beautification, civic engagement, and social well-being [14, 16-19].

Community gardens that are associated with outpatient clinics are unique in that they can potentially provide patients with prevention and/or treatment-based experiential learning as a component of their healthcare experience. Further, clinic gardens can enhance the healthcare environment, transforming it from a place for treatment to a place of health promotion and disease prevention. In 2009, a community garden was developed at an urban outpatient clinic in X, North Carolina, where services are provided on a free or reduced fee basis to individuals at or below 200% of the Federal poverty level. The purpose of the community garden is to provide fresh produce to clinic patients, facilitate nutrition education, provide a place for respite, and cultivate patient-provider relationships.

While community gardening is undergoing resurgence, there is a strong need for evaluation studies that employ valid, reliable, and widely accepted measures [18]. Therefore, the overall goal of this study was to conduct a process evaluation of patient, volunteer, and staff participation in the clinic community garden. The primary objectives of this study were to (1) calculate the percent of patients who reported awareness of the garden, who had received food from the garden, and who had visited the garden; (2) describe patient demographics and health information, household food security, and participation in the community garden; and (3) determine whether patients who received food from the garden differed by demographic characteristics and household food security vs. those who never received food from the garden. The secondary objectives were to characterize community garden volunteers and assess satisfaction with volunteering; and assess medical professionals' opinions and interest in using the garden for patient treatment and education.

Method

Setting

The outpatient clinic community garden is placed on the clinic property, and is located in a historic African-American neighborhood. The surrounding area is characterized by high rates of poverty (over 40% have an annual income of less than $15,000) and marked racial diversity (up to 76% minority, versus 39% for the entire county). North Carolina has higher prevalence of food insecurity (16.7%) and very low food security (6.4%) compared to the US averages of 14.0% and 5.6% [9]. Through a partnership between community, medical, and academic organizations, the garden was developed to cultivate fresh produce for patients of the medical clinic and residents of the surrounding neighborhood. Philanthropic foundations and other grant funding have financially supported the development and maintenance of the garden, and the costs associated with running the garden are approximately $2,000 each year. Garden volunteers (including volunteer groups, patients, neighbors, physicians, students, and master gardeners) plan, plant seeds and transplants, maintain the garden, harvest the produce, and deliver it to the adult medicine clinic for patients to take home. The seasonal variety of produce grown reflects cultural preferences and includes leafy greens, radishes, onions, turnips, peas, beets, carrots, okra, cucumbers, peppers, eggplant, beans, squash, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, blueberries, and herbs.

Garden produce reaches clinic patients and neighborhood residents in different ways. Produce is harvested by volunteers and displayed in the adult medical clinic where patients are provided bags and invited to take home the produce they prefer. Patients and neighborhood residents may also visit the garden to pick fresh produce themselves. Lastly, patients, neighborhood residents, medical clinic staff, volunteers, and community partners are invited to participate in harvest days. There are no eligibility criteria to receive food from the garden. Nutrition education at the garden or involving fresh garden produce takes place informally, initiated by health practitioners during patient visits or as part of a diabetes education class. Medical practitioners take patients to the garden, incorporate the garden produce into counseling in the office, and send their patients home with produce bags. There is no referral process, and patients who are exposed to one or more components of the garden are not followed. Development of this evaluation study was intended to be the first of many assessments to help shape programming, monitoring and evaluation centered on the medical clinic community garden.

Study Design and Recruitment

A cross-sectional survey study design was used to evaluate clinic community garden participation among patients, community volunteers, and clinic staff. Data was collected during the months of September through November in 2012. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board. The study team coordinated with the adult medical clinic staff so that patient recruitment and survey administration was not disruptive. All adult male and female patients who had previously visited the clinic and were attending appointments during the study period were recruited to verbally complete the three-question community garden participation screener during their appointment check-in procedures. Patients were then randomly selected and recruited by research personnel in the clinic to complete an additional in-person survey after checkout. A daily appointment list was generated from all follow-up patients scheduled to attend the adult medicine clinic. To randomly select patients for the survey, patients were assigned random numbers using a computer program, random numbers were sorted, and patients were approached in order of the sorted list. To prevent double sampling, the medical record number for each participant approached was entered into a system and future appointments for that patient were excluded from the patient appointments list generated each day. Patients were included in the study if they were 18 years or older and had previously been seen in the adult outpatient clinic at least once. Patients were excluded from participation if they did not understand English, or were cognitively impaired and could not complete the survey, as judged by the nursing staff or primary care physician.

To characterize the community garden volunteers and assess their satisfaction with volunteering, a convenience sample of 71 community garden volunteers were recruited to complete an online survey. The garden manager provided a list of volunteer names and contact information. Volunteers were recruited if they were 18 years of age or older and had volunteered in the community garden; and excluded if they did not understand English. The staff of the adult medicine clinic was also recruited in person by members of the research team to complete a brief survey during clinic hours inquiring satisfaction, interest, and impact of the community garden regarding clinical programming. Staff included Registered Nurses and Licensed Nurse Practitioners, physicians, and Physician Assistants, pharmacists, and administrative staff.

Instruments

The patient survey included a modified version of the Adult Community Gardener Survey, developed by the Community Food Security Coalition, and was used to assess patient participation in and satisfaction with the community garden, patient demographics and health characteristics [20]. Food insecurity was measured using the US Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form [21-22]. Patient fruit and vegetable intake was assessed using the 2-item cup fruit and vegetable screening module [23-24]. During survey administration, examples of one cup equivalents were given to help aid participants with recall of portion sizes. The portion sizes for one-cup equivalents were developed using information from the USDA MyPyramid website [23]. The patient survey was informally pilot-tested among a group of 20 patients who attended an ongoing diabetes education class at the clinic. Each patient completed the survey and specific survey items were discussed as a group (data not included here).

The volunteer survey included questions from the Adult Community Gardener Survey to assess volunteer satisfaction with participation in maintaining the clinic garden, demographic and income characteristics [20]. Volunteer fruit and vegetable intake was assessed using the same 2-item cup fruit and vegetable screening module (previously described) [23-24]. A visual call-out box proving examples of one cup equivalents placed next to these questions to help aid volunteer participants with recall of portion sizes. Developed by the research team, the staff survey collected information regarding interest level and satisfaction in the community garden. Staff were also asked how often they told patients about the community garden and garden produce, whether they had ever used the garden as a platform for education, and whether they intended to use it with patients in the future.

Data Analysis

We expected to obtain generalizable data from the in-depth patient survey with a minimum of 150 participants [20]. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, North Carolina, 2010). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviations, and frequencies) were calculated for patient characteristics, community garden participation and barriers to participation. The prevalence of patient participation was estimated by calculating the percent (95% CI) of patients who had received vegetables, heard of the garden, and who had visited the garden. T-tests for continuous variables and non-parametric fisher exact and chi-square tests were used to determine differences in community garden awareness by patient characteristics. Descriptive statistics were also calculated for volunteer characteristics, volunteer satisfaction, and satisfaction among outpatient clinic staff. The first author manually organized answers to the three open-ended questions in the volunteer survey, and main themes were generated. All steps in the analysis were discussed and reviewed with the research team.

Results

Patient Health-Related Characteristics and Community Garden Participation

Between 100 and 180 patient appointments were scheduled each day during the data collection period. These numbers do not reflect cancelled appointments and no-shows. Approximately 825 patients were potentially eligible to complete the 3-question screener during the data collection period. Of those, 411 patients completed the screener (50% response rate). Among patients who completed the 3-question screener (N=411; mean age 52 years, 66% female, 69% African-American, 26% white), 18% had received fresh vegetables from the outpatient clinic community garden, 39% had heard of the garden, and 10% had visited the garden (Table 1). Patients who were African-American (p=0.06), female (p=0.03), and slightly older (57.6 years; p=0.0018) were more likely to have received vegetables. Similarly, patients who were African-American (p=0.0001), female (p=0.18), and slightly older (55.3 years; p=0.0015) were also more likely to be aware of the community garden (Table 2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Patient Participation in Medical Center Community Garden Program (N=411).

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs)a,b | 52.1 (14.5) |

| Genderb | |

| Male | 114 (33.8) |

| Female | 223 (66.2) |

| Race or Ethnicityb,c | |

| White/Caucasian | 86 (25.5) |

| Black/African American | 232 (68.8) |

| Hispanic | 15 (4.5) |

| Asian | 1 (0.3) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 2 (0.6) |

| Has received fresh vegetables from the medical center community gardend | 18.0 (0.14, 0.22) |

| Has heard of the medical center community gardend | 39.2 (0.34, 0.44) |

| Has visited the medical center community gardend | 10.2 (0.08, 0.14) |

Data are displayed as No. (%) unless otherwise noted:

mean (SD);

Reduced sample size due to missing data; data displayed for respondents not missing demographic information.

One participant reported both African American and Hispanic.

% (95% CI).

Table 2. Garden Participation Level by Patient Demographic Information (n=337).

| Received Vegetables (n=56) | Heard of Garden (n=129) | Visited Garden (n=32) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racea | |||

| White/Caucasian (n=86) | 8 (14.3)σ | 20 (15.5)σ | 3 (9.4) |

| Black/African American (n=232) | 46 (82.1)τ | 106 (82.2)τ | 28 (87.5) |

| Other (n=19) | 2 (3.6)σ | 3 (2.3)σ | 1 (3.1) |

| Genderb | |||

| Male (n=114) | 12 (21.4)σ | 38 (29.5)σ | 10 (31.3) |

| Female (n=223) | 44 (78.6)τ | 91 (70.5)τ | 22 (68.7) |

| Mean Age (SE)b | |||

| Yes | 57.6 (1.9)τ | 55.3 (1.3)τ | 54.2 (2.3) |

| No | 51.0 (0.9)σ | 50.2 (1.0)σ | 51.9 (0.8) |

Data are displayed as No. (%) unless otherwise noted; values with different superscripts indicate significant differences (p<0.05).

Reduced sample size due to missing data.

Statistical significance determined using fisher's exact test.

Statistical significance determined using chi-square test.

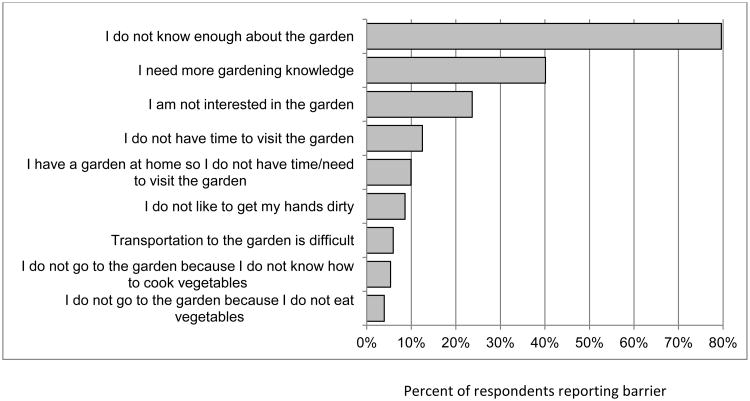

Approximately 200 patients with appointments in the adult medicine clinic were approached for recruitment to complete the additional, longer survey. Twenty patients did not speak English and 28 refused participation, yielding 152 participants who completed the additional survey (76% response rate). Approximately 61% of the respondents were African-American, 62% were female, and 84% were 41 years or older (Table 3). Thirty-eight percent completed more than 12 years of education, 40% reported unemployment, 17% were retired, and 50% reported low or very low food security. Patients reported consuming 0.8 ± 1.0 cups of fruit and 1.1 ± 0.9 cups of vegetables each day, and the most commonly used food preparation methods included boiling, steaming, and pan-frying. Sixty-six percent reported high blood pressure, 30% reported type 2 diabetes mellitus, 20% reported cancer, and 18% reported heart disease. Of the 20% of patients who had received food from the garden, approximately 67% received it only once. Among the 50% who had heard of the community garden, approximately 57% had seen it, 40% reported that someone told them about it, and almost 20% had visited the community garden. Patients who were older (P=0.035), African-American (P=0.004), or retired (P=0.018) were more likely to be aware of the community garden. The most common barrier to participation was awareness (80%), 40% reported needing more gardening knowledge, and 72% of the patients were interested in learning more about the community garden (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Patient Demographic and Health Information, Household Food Security, and Community Garden Participation (n=152).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 58 (38.2) |

| Women | 94 (61.8) |

| Age (y) | |

| 19-30 | 14 (9.2) |

| 31-40 | 10 (6.6) |

| 41-50 | 37 (24.3) |

| 51-60 | 48 (31.6) |

| ≥ 60 | 43 (28.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 93 (61.2) |

| Hispanic | 7 (4.6) |

| White/Caucasian | 50 (32.9) |

| Other | 3 (2.1) |

| Educational Attainmenta | |

| < 12 years | 37 (24.8) |

| HS graduate or GED | 55 (36.9) |

| >HS education | 57 (38.3) |

| Employment Status | |

| Unemployed | 61 (40.1) |

| Employed part-time | 13 (8.6) |

| Employed full-time | 22 (14.5) |

| Disability | 30 (19.7) |

| Retired | 26 (17.1) |

| High Or Marginal Food Security | 72 (50.0) |

| Low Food Security | 35 (24.3) |

| Very Low Food Security | 37 (25.7) |

| Daily Fruit Intake (cups/day)b | 0.8 (1.0) |

| Daily Vegetable Intake (cups/day)b | 1.1 (0.9) |

| Most Common Vegetable Preparation Methodsa | |

| Raw | 91 (59.9) |

| Boil | 80 (52.6) |

| Steam | 76 (50.0) |

| Pan Fry | 59 (38.8) |

| Medical Conditions | |

| Heart disease | 28 (18.4) |

| Stroke | 17 (11.2) |

| High blood pressure | 100 (65.8) |

| Diabetes | 46 (30.3) |

| Cancer | 30 (19.7) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder | 13 (8.6) |

| Patients who have received produce | 30 (19.7) |

| Received only 1 bag | 20 (66.7) |

| Received 2 or more bags, less than monthly | 5 (16.7) |

| Received 2 or more bags, monthly | 2 (6.7) |

| Received 2 or more bags, weekly | 3 (10.0) |

| Patients who have heard of the community garden | 76 (50.0) |

| Have seen ita | 43 (56.6) |

| Have seen signsa | 9 (11.8) |

| Was told about it by someone:a | 30 (39.5) |

| Nurse | 11 (36.7) |

| Doctor | 7 (23.3) |

| Another staff member | 4 (13.3) |

| Someone else (such as a friend) | 8 (26.7) |

| Patients who have visited the community garden | 15 (19.7) |

| Patients who have volunteered at the garden | 2 (2.6) |

Reduced sample size due to missing data.

Data are displayed as No. (%) unless otherwise noted:

mean (SD).

Figure 1. Patient Barriers to Community Garden Participation.

Volunteer Characteristics, Satisfaction, and Personal Impact

Of the 71 community garden volunteers recruited for participation in this study, 30 completed the volunteer survey (42% response rate). Ninety-three percent of the volunteer respondents were white, 83% were female, and 47% were between the ages of 19 and 30 (n=30; Table 4). On average, volunteers reported consuming 1.9 ± 0.9 cups of fruit and 2.3 ± 0.9 cups of vegetables each day. When asked about the personal impact as a result of working in the community garden, volunteers reported that they had learned more about gardening (97%), gained new gardening skills (96%), felt more involved in the neighborhood (82%), cared more about the environment (61%), and knew more about the environment (60%). Additionally, volunteers reported that they taught family or friends to garden (47%), ate food that is fresher, were more physically active (40%), ate new kinds of foods (27%), and ate less fast food (20%).

Table 4.

Volunteer Demographic Information and Community Garden Participation (n=30).

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 5 (16.7) |

| Women | 25 (83.3) |

| Age (y) | |

| 19-30 | 14 (46.7) |

| 31-40 | 5 (16.7) |

| 41-50 | 2 (6.7) |

| 51-60 | 5 (16.7) |

| ≥ 60 | 4 (13.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 1 (3.3) |

| White/Caucasian | 28 (93.3) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3.3) |

| Educational Attainment | |

| College graduate | 9 (30.0) |

| Graduate school | 21 (70.0) |

| Employment Status | |

| Unemployed | 6 (21.4) |

| Employed part-time | 5 (17.9) |

| Employed full-time | 12 (42.9) |

| Refuse or don't know | 1 (3.6) |

| Retired | 4 (14.3) |

| Daily Fruit Intake (cups/day)a | 1.9 (0.9) |

| Daily Vegetable Intake (cups/day)a | 2.3 (0.9) |

| Patient at Downtown Health Plaza | 1 (3.3) |

| Staff Member of Downtown Health Plazab | 5 (17.2) |

Data are displayed as No. (%) unless otherwise noted:

mean (SD).

Reduced sample size due to missing data:

When asked what they liked best about volunteering in the community garden, common themes included community involvement, helping others, working with other volunteers, and spending time outside in the garden. One volunteer stated, “I started coming to the garden to help put fresh food on someone's table that might not otherwise have access. I keep coming back because I enjoy the variety of people I have met and what I have learned about gardening. There is an energy at the garden that is contagious.” When asked what they liked least about volunteering at the community garden, the most common theme was time constraints, followed by limitations in confidence and knowledge of gardening skills. When asked if and how the community garden has made a difference in their life, the most common themes were feeling a sense of community and meeting the needs of the community. Additional themes included learning more about food insecurity, providing an outlet and reducing stress, meeting new people, feeling a sense of fulfillment, and learning about growing produce.

Clinical Staff Support

All of the 20 regular outpatient clinic staff completed the survey. Staff responded favorably in using the community garden in patient treatment and education (Table 5). The frequency of patient referral varied such that 30% told their patients about the community garden ‘all of the time,’ 40% reported ‘most of the time,’ and 30% reported ‘some of the time.’ Approximately 40% of the medical professionals reported that they had used the community garden for patient education, which included discussing availability and value of fresh produce, discussing the importance of vegetables in the diet, discussing the differences between fresh and canned vegetables and how to cook them, offering vegetables as part of discussion about diet and type 2 diabetes, mentioning that home grown produce provides vitamins and fiber, teaching how to use fresh vegetables, and discussing the benefits of eating fresh vegetables. All of the respondents reported that the community garden could be used ‘as an effective tool for nutrition education,’ and nearly all agreed it could be used ‘as a tool to address issues of food insecurity,’ ‘to facilitate patient/provider communication,’ and ‘to provide access to fresh produce among patients in the clinic.’

Table 5.

Satisfaction, Participation, and Interest in the Medical Center Community Garden Among Medical Professionals (n=20).

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Tell patients about the community garden (Yes) | 20 (100.0) |

| Some of the time | 6 (30.0) |

| Most of the time | 8 (40.0) |

| All of the time | 6 (30.0) |

| Tell patients about the free garden produce bags (Yes) | 20 (100.0) |

| Some of the time | 4 (20.0) |

| Most of the time | 9 (45.0) |

| All of the time | 7 (35.0) |

| Have used community garden for patient education (Yes) | 8 (40.0) |

| Level of interest in using community garden for patient education | |

| Very interested | 5 (20.0) |

| Already using it with patients | 6 (30.0) |

| Agreement in usefulness of community garden activities (Strongly Agree/Agree) | |

| Can be used as an effective tool for nutrition education | 20 (100.0) |

| Can be used as a tool to address issues of food insecurity | 17 (85.0) |

| Can be used to facilitate patient/provider communication | 19 (95.0) |

| Provides access to fresh produce among clinic patients | 20 (100.0) |

| Has volunteered at community gardena | 4 (21.1) |

| Overall experience with community gardena | |

| Good | 4 (22.2) |

| Excellent | 14 (77.8) |

| Professiona | |

| Physician | 2 (10.5) |

| Physician Assistant | 2 (10.5) |

| Pharmacist | 1 (5.2) |

| Nurse/CAN | 10 (52.6) |

| Other | 4 (21.1) |

Reduced sample size due to missing data:

Discussion

Community gardening has been recognized as a new paradigm for community engagement and wellness. The extent to which this paradigm can be applied to the healthcare environment is the underlying topic of this paper. A process evaluation of a clinic community garden was pursued to help shape future programming and to answer important questions regarding value and reach. Although recommendations have been made for the evaluation of community gardens, this is the first known community garden study to apply process evaluation principles. The findings of this evaluation of patient, volunteer, and staff participation in a clinic community garden helped identify several important factors that may promote its maintenance and improve its effectiveness. One of the most noticeable findings was the lack of patient awareness of and actual use of the garden. While 70% of healthcare providers reported telling patients about the garden and 40% reported using the garden for patient education purposes, only 39% of patients reported being aware of its existence. In general, patients did not endorse barriers to engagement with the community garden, with fewer than one-tenth mentioning transportation, time, lack of interest in eating or cooking vegetables as barriers. Rather, 80% of patients reported lack of knowledge as a primary barrier for visiting the community garden, and 72% were interested in learning more. Therefore, activities aimed to increase awareness of the community garden, such as cooking demonstrations, as well as increased promotion in-clinic and through social media outlets, may be effective strategies to increase participation among clinic patients. High levels of interest among patients may also increase the likelihood of successful patient recruitment for clinic programs that use the garden as a platform for nutrition education.

Another noticeable finding was that two-thirds of the patients who received garden produce had only done so once. Receiving garden produce from a clinic community garden sparingly is not going to alleviate experiences of food insecurity. However, it may serve as a nudge for individuals to seek nutrition assistance services. It is also important to consider this finding when developing interventions to address food insecurity and clinic garden-based programming in general. Rather than a clinic farm stand, the most effective use of a clinic community garden space may instead consist of focused nutrition education programming with consistent patient participants. Although we did not specifically ask about barriers to receiving produce, it may be that with the lack of awareness of the community garden, patients were unaware of where the produce had come from, or that they could come and receive bags at other times other than during visits. It is expected that increased awareness of the garden may improve uptake of food bags by patients.

As a result of working in the community garden, volunteers reported eating more fresh food, being more physically active, learning about gardening, feeling more involved in the neighborhood, and teaching family/friends to garden. Previous research has reported similar findings [7, 25]. Garden volunteers in this study also reported caring more about the environment as a result of working in the garden. Similarly, others have reported that community gardens are associated with increases in environmental stewardship and have been used as a tool to facilitate environmental literacy [26-27]. Community gardens are known to promote community building, civic engagement, social capital, and social well-being [14, 17-19, 25-26]. Community garden volunteers in this study reported similar values. When asked what they liked best about volunteering in the garden, the most common responses were community involvement, helping others, working with others, and spending time outside.

The findings of this study also helped to identify important factors that will promote the maintenance of other medical center-based community garden programs, such as clinic support. Overall, medical center staff reported that the community garden was a useful component of the clinical environment, and identified the garden as an important component in nutrition education. Nearly half of all clinical staff reported that they had used the garden for patient education and as a catalyst for discussions pertaining to food production, food access, and food preparation. However, the staff need to be made aware that there may be a communication gap between them telling the participants about the garden and the produce bags and the participants' awareness of the garden program. Staff may feel that mentioning the garden to a participant on one occasion is sufficient, but it may take repeat reminders about the garden and produce bags to increase awareness among patients. Furthermore, the neighborhood community development corporation, one of the partners engaged in the community garden, received a large grant to increase neighborhood access to healthful foods. While the majority of funding is dedicated to the introduction of a market retail space, employment training, catering, and a restaurant, a portion of the budget will be appropriated to the garden for outreach activities, including cooking demonstrations, educational outreach and training. These types of outreach activities may lead to greater awareness and participation.

This study is not without limitations. The study design was cross-sectional and findings are specific to a community garden located at an urban outpatient clinic. Therefore, the findings are not generalizable to other community garden settings, and may be most useful for program planning and future research. Seasonal variation in garden produce and volunteerism was not considered in the study design. Although a random patient sampling protocol was used to minimize selection bias, it may have still influenced the results, especially considering patients who did not attend their scheduled appointments. It is also important to consider the limited reach of the clinic community garden during the time of this evaluation. While facilitators and barriers to patient awareness and participation in the community garden were investigated, factors not included in this study may help explain the lower awareness rates. Additional factors should be considered in future evaluations and the use of semi-structured interviews and focus groups may help provide further clarity. Lastly, while patient participation rates were high for the three-question patient participation screener and longer patient survey, the number of patients who reported receiving food from the garden (or were exposed to the garden) was not large enough to make comparisons by demographic characteristics, household food security, and important outcome data such as fruit and vegetable intake.

This systematic, comprehensive evaluation also had several strengths. The process evaluation was multidimensional, including an evaluation of patient awareness and participation, volunteer participation, and staff support. The random patient sampling protocol was another strength of this study, and its use is strongly recommended for future studies. The patient and volunteer community garden surveys were developed using validated tools, and were culturally adapted and informally pilot tested prior to their use. The patient and staff response rates were also high. The patient response rate was 76% for the detailed survey, and the staff response rate was 100%.

Conclusion

Comprehensive process evaluations can be utilized to quantify benefits of community gardens in medical centers as well as to point out areas for further development, such as increasing patient awareness. As nutrition education and garden programming are formalized and implemented, future research should continue to include systematic evaluations, such as summative evaluation and long-term follow-up to determine whether this unique component of the healthcare environment helps improve patient outcomes. A particularly unique opportunity for research at the administrative and community levels could focus on the recent ruling by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) that allows nonprofit hospitals to claim the help they provide their communities to ensure adequate nutrition as part of their exemption from federal taxation [28]. In addition to claiming tax credit for prescription programs that substitute healthier foods for medicine and programs that reduce the cost of fruits and vegetables in farmers markets and grocery stores, this ruling could help nonprofit hospitals claim tax credit for their efforts surrounding hospital-based community gardens and urban farms. Monitoring and evaluation may help motivate hospitals streamline their efforts toward improving community nutrition and healthful food access.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted in the Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy at Wake Forest School of Medicine and Comprehensive Cancer Center at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, 27157 NC, USA. We wish to thank those who volunteered their time and effort at the Downtown Health Plaza Goler Community Garden, the staff at the Downtown Health Plaza, and Michael Suggs and Gwen Jackson, with the Goler Community Development Corporation, for their time and partnership. This work was supported by the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest School of Medicine and the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Control Traineeship. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984;224(4647):420–421. doi: 10.1126/science.6143402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulrich RS. Human responses to vegetation and landscapes. Landscape Urban Planning. 1986;13:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulrich RS, Quan X, Zimring C, Joseph A, Choudhary R. The role of the physical environment in the hospital of the 21st century: a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Concord, CA: Center for Health Design; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin HR, Owens AJ, Golden G. An investigation to determine whether the built environment affects patients' medical outcomes. Martinez, CA: Center for Health Design; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman SA, Varni JW, Ulrich RS, Malcarne VL. Post-occupancy evaluation of health gardens in a pediatric cancer center. Landscape Urban Planning. 2005;73:167–183. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johanson DB, Smith LT. Testing the recommendations of the Washington State Nutrition and Physical Activity Plan: The Moses Lake Case Study. [Accessed December 22, 2015];Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006 3(2):A64. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/apr/05_0096.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carney PA, Hamada JL, Rdesinski R, Sprager L, Nichols KR, Liu BY, Pelayo J, Sanchez MA, Shannon J. Impact of a community garden project on vegetable intake, food security and family relationships: A community-based participatory research study. Journal ofCommunity Health. 2012;37(4):874–881. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9522-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang S, Holt AM, Azevedo E. An assessment of the barriers to accessing food among food-insecure people in Cobourg, Ontario. Chronic Disease and Injuries in Canada. 2011;31(3):121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman-Jensen A, Gregory C, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2013, ERR-173. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; Sep, 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams EJ, Grummer-Strawn L, Chavez G. Food insecurity is associated with increased risk of obesity in California women. Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133:1070–1074. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute Fact Sheet: Cancer Health Disparities. [Accessed December 22, 2015]; http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/disparities/cancer-health-disparities.

- 12.Blanck H, Galuska D, Gillespie C, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Solera MK. Fruit and vegetable consumption among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56(10):213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanck HM, Thompson OM, Nebeling L, Yaroch AL. Improving fruit and vegetable consumption: use of farm-to-consumer venues among US adults. [Accessed December 22, 2015];Preventing Chronic Disease. 2011 8(2):A49. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/mar/10_0039.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alaimo K, Packnett E, Miles RA, Kruger DJ. Fruit and vegetable intake among urban community gardeners. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2008;40(2):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litt JS, Soobader MJ, Turbin MS, Hale JW, Buchenau M, Marshall JA. The influence of social involvement, neighborhood aesthetics, and community garden participation on fruit and vegetable consumption. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;72(11):1853–1863. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong D. A survey of community gardens in upstate New York: Implications for health promotion and community development. Health & Place. 2000;6:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(00)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teig E, Amulya J, Bardwell L, Buchenau M, Marshall JA, Litt JS. Collective efficacy in Denver, Colorado: strengthening neighborhoods and health through community gardens. Health and Place. 2009;15:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormack GR, Rock M, Toohey AM, Hignell D. Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: a review of qualitative research. Health and Place. 2010;16(4):712–726. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoellner J, Zanko A, Price B, Bonner J, Hill J. Exploring community gardens in a health disparate population: findings from a mixed methods pilot study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2012;6(2):153–165. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Research Center, Inc., and the Community Food Security Coalition. Community food project evaluation handbook and toolkit. Boulder, CO: National Research Center, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, Briefel RR. The effectiveness of a short form of the household food security scale. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1231–1234. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics. US household food security survey module: six-item short form. 2008 http://www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/foodsecurity/surveytools/short2008.pdf.

- 23.Yaroch AL, Tooze J, Thompson FE, Blanck HM, Thompson OM, Colon-Ramos U, Shaikj A, McNutt S, Nebeling LC. Evaluation of three short dietary instruments to assess fruit and vegetable intake: The National Cancer Institute's Food Attitudes and Behaviors (FAB) Survey. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erinosho TO, Moser RP, Oh AY, Nebeling LC, Yaroch AL. Awareness of the Fruits and Veggie-More Matters campaign, knowledge of the fruit and vegetable recommendation, and fruit and vegetable intake of adults in the 2007 Food Attitudes and Behaviors (FAB) Survey Appetite. 2012 Aug;59(1):155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.010. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glover TD, Parry DC, Shinew KJ. Building relationships, accessing resources: mobilizing social capital in community garden contexts. Journal of Leisure Research. 2005;37(4):450–474. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gough MZ, Accordino J. Public gardens as sustainable community development partners: motivations, perceived benefits, and challenges. Urban Affairs Review. 2013;49:851–887. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basile CG, White C. Respecting living things: environmental literacy for young children. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2000;28:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Hagstrom Report. [Accessed July 14, 2016];IRS: Nonprofit hospitals can claim nutrition access aid to avoid taxes. 2015 Jan 6;5(Number 1) Tuesday. http://www.hagstromreport.com/2015news_files/2015_0106_irs-nonprofit-hospitals-can-claim-nutrition-access-aid.html. [Google Scholar]