Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic, relapsing, immunological, inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD). It has been reported that UC, which is studied using a dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis model, is associated with the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the apoptosis of intestine epithelial cells (IEC). Mitochondrial NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2) has been reported as an essential enzyme in the mitochondrial antioxidant system via generation of NADPH. Therefore, we evaluated the role of IDH2 in DSS-induced colitis using IDH2-deficient (IDH2-/-) mice. We observed that DSS-induced colitis in IDH2-/- mice was more severe than that in wild-type IDH2+/+ mice. Our results also suggest that IDH2 deficiency exacerbates PUMA-mediated apoptosis, resulting from NF-κB activation regulated by histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity. In addition, DSS-induced colitis is ameliorated by an antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) through attenuation of oxidative stress, resulting from deficiency of the IDH2 gene. In conclusion, deficiency of IDH2 leads to increased mitochondrial ROS levels, which inhibits HDAC activity, and the activation of NF-κB via acetylation is enhanced by attenuated HDAC activity, which causes PUMA-mediated apoptosis of IEC in DSS-induced colitis. The present study supported the rationale for targeting IDH2 as an important cancer chemoprevention strategy, particularly in the prevention of colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Colitis, DSS, IDH2, Mitochondria, Apoptosis

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

DSS-induced colitis model is associated with the production of ROS.

-

•

IDH2 is an essential enzyme in the mitochondrial antioxidant system.

-

•

IDH2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis.

-

•

IDH2 deficiency exacerbates apoptosis through the PUMA/NF-κB/HDAC axis.

-

•

Protection of NAC against DSS-induced colitis IDH2-deficient mice was observed.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic, relapsing, immunological, inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) [1], [2]. IBD causes various symptoms such as loss of bodyweight, abdominal pain, and diarrhea with blood [3]. According to numerous studies, IBD is associated with genetic and environmental factors, immunological disorders, and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, the pathogenesis of IBD remains poorly understood [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6].

Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) is a sulfated polysaccharide containing ~17% sulfur with up to three sulfates groups per glucose molecule. The DSS-induced mouse model of colitis is one of the most widely used models that mimic UC-like disease in humans [7]. Oral administration of DSS in spring water to mice results in inflammation in the mid-distal colon, similar to the human IBD symptom. This leads to decreased body weight, bloody diarrhea, and eventually death in a time- and dose-dependent manner [8], [9]. Colitis is associated with apoptosis in human UC [10], [11], [12], [13], and DSS-induced mouse colitis is associated with apoptosis of intestine epithelial cells (IEC) [13], [14], [15]. Under normal conditions, apoptosis not only plays a role in homeostasis through maintaining cell amounts in tissues, but also in defense mechanisms when cells are impaired by disease or toxins. However, when these toxins, such as radiation, toxic agents, or ROS, exceed the threshold, apoptosis is elevated in an uncontrollable manner and consequently, this abnormal apoptosis causes a set of diseases [16], [17].

Among many causative factors, ROS has a crucial role in the induction of apoptosis [18]. ROS such as superoxide anions (O2-), hydroxyl radicals (HO·), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are produced in vivo as by-products of aerobic metabolism, and also as defense mechanisms in immune cells against pathogens, intracellular signaling pathways as messengers, and from environmental factors such as radiation and xenobiotic compounds [19]. These ROS oxidize biological macromolecules such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which cause damage to the cell [20]. In order to defend against damage by ROS, cells are equipped with elaborate anti-oxidant defense systems. These defense systems include anti-oxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutaredoxin, and preoxiredoxin, and antioxidant-related enzymes such as reduced glutathione (GSH) and NADPH [21]. When these antioxidant systems are impaired by increased ROS production from environmental factors or lack of cellular antioxidant capacity, it causes a number of diseases in human [22], [23].

The mitochondrial NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2) catalyzes the conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate, producing NADPH from NADP+ in mitochondria [24]. NADPH is an essential reducing equivalent for both the thioredoxin and glutathione systems [25]. Therefore, IDH2 is implicated as a critical antioxidant enzyme in the regulation of redox status and reduction of oxidative stress-induced damage [26]. Recently, it was reported that knockout of the IDH2 gene exacerbates dopaminergic neurotoxicity [26] and cardiac hypertrophy [27]. In the present study, we used IDH2 deficient mice to investigate the functional relationship between IDH2 and colonic injury in the DSS colitis model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal care and experimental protocols

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Kyungpook National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were performed using 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice with different genotypes, including wild-type IDH2+/+ and knockout IDH2-/- mice, generated by breeding and identified by PCR genotyping, as previously described [28]. The mice were housed in microisolator rodent cages at 22 °C with a 12 h light/dark cycle and allowed free access to water and standard mouse chow. The mice were divided into four groups, with 7–12 mice per group (WT, WT + DSS, KO, KO + DSS). Colitis was established by administration of 2% DSS in drinking water for 7 consecutive days. Rodents surviving during the period after administration were calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method. For the N–acetylcysteine (NAC) experiment, mice were pretreated with NAC (100 mg/kg) for 3 days, and treatment was continued during DSS administration for 1 week, induced by intraperitoneal injection.

2.2. Evaluation of colitis

The disease activity index (DAI) of colitis was determined by scoring the loss of weight, stool consistency, and stool bleeding in accordance with the method described previously [29], [30]. The DAI value was evaluated by an observer unaware of the treatment groups.

2.3. Histological analysis

For histopathological scores, colon tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then soaked in 30% sucrose in PBS. After cryoprotection, the tissue was embedded in OCT compound and cryosectioned into slices 3 µm in thickness. The histological scores were measured by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of mice colon, which showed damage and severe infiltration. Crypt injury and inflammation was evaluated by an observer unaware of the treatment groups [31]. For Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) staining, colon tissue samples were prepared as described for H&E staining and examined using the PAS staining kit (Sigma, St Louis, MO) following the manufacturer's protocol. The histological scores were calculated as increased mucus production was observed in PAS-stained sections of mice colon. H2O2 level was measured using 3,3-diaminobenzidine-HCl (DAB). Briefly, cryosectioned colon tissue, 3 µm in thickness, was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in 0.1 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing glucose (1 mg/ml) and DAB (1 mg/ml), in turn, washed with normal saline (0.9% NaCl) twice, and counterstained using hematoxylin. DAB-stained slides were mounted on glass slides, and both were analyzed under an Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss AG; Oberkochen, Germany).

2.4. Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Antibodies were purchased from the following sources: anti p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA), anti c-caspase 3, anti c-PARP, anti acetyl-H3, and anti acetyl-H4 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti p65 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), anti acetyl-p65 (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), anti 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) (AbCam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti NADPH (Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK) and anti 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) (Millipore, Milford, MA). Three-micrometer thick colon sections were rinsed in PBS, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the appropriate primary antibodies. The colon sections were then washed with PBS, and incubated with the appropriate fluorophore-conjugated, or biotinylated secondary antibody processed with an avidin-biotin complex kit (VECTASTAIN ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Biotinylated secondary antibody was visualized with 3,3-diaminobenzidine-HCl (DAB). Fluorescent antibody stained slides were then treated with an anti-photo bleaching reagent and sealed with cover glass, and DAB stained slides were mounted on glass slides. Both were analyzed under an Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss AG; Oberkochen, Germany).

2.5. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity

MPO activity was determined as a measure of neutrophil activity. Colon tissues (50 mg) were washed, homogenized in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at a ratio of 50 mg tissue to 1 ml buffer, and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was homogenized in 300 μl of potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HTAB; Sigma, St Louis, MO). The suspension was sonicated for 20 s on ice, and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was blended with an enzyme substrate buffer containing 0.167 mg/ml O-dianisidine hydrochloride (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide. The changes for MPO activity were determined using absorbance values measured at 405 nm.

2.6. Immunoblot analysis

Antibodies were purchased from the following sources: anti GSH (Virogen, Waterstown, MA), anti nitrotyrosine (AbCam, Cambridge, MA), anti dinitophenol (DNP) (Sigma, St Louis, MO), anti PUMA (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Conventional immunoblotting protocols were applied to detect the target proteins. Total proteins were separated on 10–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies, and immune reactive antigens were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.7. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining

To evaluate apoptosis, colon tissue sections were used for TUNEL staining using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. TUNEL-stained slides were lightly counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) before final mounting. The stained slides were analyzed under an Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss AG; Oberkochen, Germany).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Results are shown as the mean ± SD. Analyses were performed using a two-tailed t-test. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. DSS-induced colitis in IDH2-/- mice

To test whether IDH2 plays a role in induction of DSS-induced acute colitis, IDH2+/+ and IDH2-/- mice were exposed to 2% DSS in their drinking water for 7 consecutive days. When we observed the survival rate of DSS-induced acute colitis, there was remarkable change in mortality between IDH2+/+ and IDH-/- mice. IDH2-/- mice had a 57.1% survival rate at 7 days; however, none of the IDH2+/+ mice died during the study period (Fig. 1A), reflecting the observed IDH2-/- preference for DSS susceptibility. As we observed the survival rate of the mice, we explore the severity of colitis in detail by evaluating the DAI value of IDH2+/+ and IDH2-/- mice under DSS treatment. UC is known to cause loss of bodyweight, abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea [1], [2]. We observed that the DAI value was dramatically enhanced in the mice with IDH2-/- compared to those in the IDH2+/+ group (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that IDH2-/- is highly susceptible to DSS-induced colitis. It is well known that DSS-induced colitis affects the colon, therefore; after DSS administration for 1 week, the mice were sacrificed, and the colon length was measured. After 1 week of DSS exposure, the mean length of the colons from IDH2-/- mice was significantly shorter than that of the colons from the control mice without DSS exposure (Fig. 1C). To determine the histological characteristics of colons influenced by DSS in detail, we performed freeze-sectioning of the colon tissue. Oral administration of 2% DSS for 1 week resulted in colitis-associated histologic alterations, including shortening of colonic crypts, infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lamina propria, and separation of the crypt base from the muscularis mucosae. Increased DSS-induced histological basis of colitis severity was found in IDH2-/- mice as compared with their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 1D and Fig. 1E). Neutrophils are the hallmark infiltrating leukocytes in the DSS-induced inflamed colon [32]. The level of neutrophil infiltration into the colon and the degree of damage on the crypts of IDH2+/+ mice and IDH2-/- mice was evaluated. The score of IDH2-/- mice was higher than that of IDH2+/+ mice (Fig. 1F). Intestinal MPO activity was measured as an indicator of the extent of neutrophil infiltration. The MPO activity appeared to be significantly higher in the IDH2-/- mice compared to DH2+/+ mice when exposed to DSS (Fig. 1G). Thus, IDH2 deficiency aggravates colitis survival and seems to be associated with increased accumulation of neutrophils. Collectively, these results suggest that the presence of the IDH2 gene has a strong effect on DSS-induced colitis. However, why the absence of the IDH2 gene aggravates DSS-induced colitis remained unclear. Therefore, we further explored the detailed mechanism of DSS-induced colitis in IDH2-/- mice.

Fig. 1.

DSS-induced colitis in IDH2-/- mice. IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice were treated with 2% DSS for 1 week to induce colitis. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of DSS-treated IDH2 mice. n = 7–12 of each group. (B) Disease activity index (DAI) scores were evaluated for 7 consecutive days. (C) Lengths of colons from IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of colon tissues after 1 week of DSS administration. (E) Periodic Acid Schiff staining was performed with cryosectioned colon tissue slices, 3 µm in thickness. (F) The average for each element in the histological score for IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (G) Colonic myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice with DSS administration was measured using absorbance values measured at 405 nm. In B-G, results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3–6 mice of each group). *P<0.05, versus DSS-treated wild-type mice.

3.2. IEC apoptosis of DSS-induced colitis in IDH2-/- mice

It has previously been reported that DSS-induced colitis is related to IEC apoptosis [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. To study the role of IDH2 in IEC apoptosis, we performed TUNEL staining with colon tissue removed from DSS-induced colitis IDH2+/+ and IDH2-/- mice. As shown in Fig. 2A, more TUNEL stained spots were observed in IDH2-/- mice than in IDH2+/+ mice (Fig. 2A). In order to confirm the induction of IEC apoptosis, we stained cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 3 as active forms in colon tissue. In agreement with the data in Fig. 2A, these signals were increased in IDH2-/- mice compared to IDH2+/+ mice (Fig. 2B and Fig. 2C). Next, we evaluated why the level of apoptosis in IDH2-/- mice was higher than in IDH2+/+ mice. It has been reported that PUMA-mediated apoptosis is associated with DSS-induced colitis [13]. Therefore, we confirmed the PUMA level in DSS-induced mice colon tissues. The PUMA level in IDH2-/- mice was elevated in comparison to that in IDH2+/+ mice (Fig. 2D and Fig. 2E). These results suggest that the difference in severity of colitis depends on the presence of the IDH2 gene due to the level of apoptosis. PUMA is directly activated by NF-κB, a key player in intestinal inflammation [33]. NF-κB is a key transcription factor involved in promoting the pro-inflammatory mediators [34]. Although NF-κB is indispensable for maintaining immune functions, its excessive activation leads to stimulation of immune cells, resulting in inflammation [35]. Recently, it has been noted that acetylation of p65 plays an important role in regulation of NF-κB activation [36]. Acetylated p65 is subsequently deacetylated by histone deacetylase (HDAC) [36], [37], which promotes binding to IκBα. Thus, it has been proposed that deacetylation of p65 by HDAC represents the intracellular switch controlling the activation status of NF-κB [36]. Accumulating evidence suggests that HDAC regulates not only the acetylation levels of H3 and H4 underlying nucleosomes, but also the activity of NF-κB in a number of ways [38]. Therefore, we observed the activation of NF-κB through p65 acetylation in colon tissue of DSS-induced colitis in IDH2+/+ and IDH2-/- mice. The activation of NF-κB reflected by the acetylation of p65 in the colon tissue of IDH2-/- mice was higher than that in IDH2+/+ mice (Fig. 2F). In addition, we determined the activity of HDAC indirectly through evaluation of the acetylation levels of H3 and H4. As shown in Fig. 2G and Fig. 2H, significantly higher levels of acetylated H3 and H4 were observed in the colon tissue from IDH2-/- mice compared to that from IDH2+/+ mice. Taken together, these results suggest that the apoptosis level in IDH2 deficient mice was elevated by increased levels of PUMA, resulting from enhanced NF-κB activation by suppression of HDAC activity.

Fig. 2.

Intestine epithelial cell (IEC) apoptosis of DSS-induced colitis in IDH2-/- mice. (A) TUNEL staining of colon tissues from DSS-treated IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (B) Immunofluorescent staining for c-PARP in colon tissues from DSS-treated IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (C) Immunohistochemical staining for c-caspase 3 and (D) PUMA in colon tissues from DSS-treated IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (E) Immunoblots comparing the levels of PUMA in colon tissue extracts from DSS-treated IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. Actin was used as a loading control. Quantification of PUMA levels normalized to actin is shown. (F) Immunofluorescent staining for acetyl-p65, (G) acetyl-H3, and (H) acetyl-H4 in colon tissues from DSS-treated IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. Histograms represent the quantification of fluorescence intensity. The figure shows representative data of 3–6 independent experiments. In A-B and E-H, the results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3–6 mice of each group). *P<0.05, versus DSS-treated wild-type mice.

3.3. Modulation of redox status in colon tissues of IDH2-/- mice

The major enzyme to generate mitochondrial NADPH is the mitochondrial isoenzyme IDH2 [26]. Thus, deficiency of IDH2 activity may induce an imbalance of the redox status in mitochondria, which subsequently increases the vulnerability of colon cells to DSS. In order to elucidate the mechanisms by which deficiency of IDH2 leads to an increase in apoptosis, resulting from the HDAC/NF-κB/PUMA axis, we attempted to analyze the redox status. It has been reported that the activity of HDAC is affected by oxidative stress [38], [39], while IDH2 plays an important role in the activity of anti-oxidant enzymes [24]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the effect of IDH2 deficiency on the redox status affects the activity of HDAC. We observed the redox status in mitochondria of DSS-induced colitis using IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. The redox status of IDH2-/- mice was impaired more than that of IDH2+/+ mice as reflected by a decrease in NADPH and an increase of glutathionylated proteins in colonic tissues (Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B). There are numerous oxidative stress-induced conditions during which the redox status and GSH/GSSG ratio are perturbed [40]. Protein S-glutathionylation is a post-translational modification of protein sulfhydryl groups that occurs under oxidative stress [41]. The elevated ROS levels in the colonic tissues of DSS-induced colitis, which were measured as the increased level of H2O2 through DAB staining (Fig. 3C), and oxidative damage, such as lipid peroxidation (Fig. 3D), oxidative DNA damage (Fig. 3E), and protein oxidation (Fig. 3F) were significantly higher in IDH2-/- mice compared to IDH2+/+ mice. Lipid peroxidation was measured for the HNE protein adduct analysis using an anti-HNE antibody, and the levels of oxidative protein damage were measured by determining the number of derivatized carbonyl groups on oxidized proteins by immunoblotting [28]. Oxidative DNA damage was evaluated by measuring the level of 8-OH-dG adducts in DNA using an 8-OH-dG antibody [42]. In addition, the nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity was found to be relatively stronger in IDH2-/- mice compared with IDH2+/+ mice, which indirectly reflects the higher level of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in IDH2-/- mice (Fig. 3G). These results supported the notion that deficiency of the IDH2 gene deteriorates the redox status and inhibits the activity of HDAC. Therefore, our results suggest that increased ROS production aggravates DSS-induced colitis through IEC apoptosis, resulting from the PUMA/NF-κB/HDAC axis.

Fig. 3.

Modulation of redox status in colon tissues of IDH2 mice. (A) Immunofluorescent staining for NADPH in colon tissues from DSS-treated IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (B) The levels of glutathionylated adducts in colon tissue extracts were measured with anti-GSH antibody. (C) Quantification of hydrogen peroxide level by histochemical staining with DAB. (D) Immunofluorescent staining for HNE protein adducts and (E) 8-OHdG DNA adducts in colon tissues from DSS-treated IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (F) The levels of oxidized protein adducts and (G) nitrosylated protein adducts in colon tissue extracts were measured with anti-DNP and anti-nitrotyrosine antibodies, respectively. Histograms represent the quantification of fluorescence intensity. The figure shows representative data of 3–6 independent experiments. In A, D and E, the results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3–6 mice of each group). *P<0.05, versus DSS-treated wild-type mice.

3.4. Protective effects of NAC against DSS-induced colitis

To confirm the influence of increased oxidative stress on DSS-induced colitis, we evaluated the effect of NAC on the treatment of UC caused by DSS in IDH2 mice. It was previously shown that NAC reduced oxidative stress by improving the thiol redox status [43]. We evaluated the DAI value of DSS-administered IDH2-/- mice treated with NAC against IDH2-/- mice administered only DSS. As shown in Fig. 4A, IDH2-/- mice treated with DSS alone had a higher rated score than DSS-administered IDH2-/- mice with NAC (Fig. 4A). After the mice were sacrificed, we measured the colon length of both the DSS-only intake group and the DSS with NAC group. The colon length of the DSS with NAC-treated group was longer than that of the DSS-only group (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the colon morphology and histological score of DSS-induced colitis in the NAC and DSS-treated group were ameliorated compared to that in the DSS-only treated group (Fig. 4C and Fig. 4D). To demonstrate whether NAC affects the molecular mechanisms involved in DSS-induced colitis, we attempted to analyze apoptosis and the HDAC/NF-κB/PUMA axis. We performed TUNEL staining with colon tissue of the NAC with DSS-treated group and the DSS-only treated group. The TUNEL staining signal for the NAC with DSS-treated group was increased compared to that of the DSS-only treated group (Fig. 4E). In relation to apoptosis, we evaluated the level of PUMA in colon tissue. The PUMA levels in the DSS with NAC-treated group were observed to be elevated compared to those of the DSS-only treated group (Fig. 4F). Next, we observed the activity of NF-κB through acetylation in the colon tissue of both the NAC with DSS and DSS-only treated groups. The activity of NF-κB in the NAC and DSS-treated group was elevated compared to that of the DSS-only treated group (Fig. 4G). Additionally, we observed the levels of H3 and H4 acetylation in colon tissue of both the NAC with DSS and DSS-only treated groups. The levels of acetylation in H3 and H4 of the NAC with DSS treated-group were significantly increased compared to that of the DSS-only treated group (Fig. 4H and Fig. 4I). These results suggest that DSS-induced colitis is ameliorated by NAC through protection against oxidative stress, which results from deficiency of the IDH2 gene. In conclusion, deficiency of IDH2 leads to increased ROS levels, which inhibits HDAC activity. In turn, the activation of NF-κB is enhanced by attenuated HDAC activity, causing PUMA-mediated apoptosis in IEC in DSS-induced colitis.

Fig. 4.

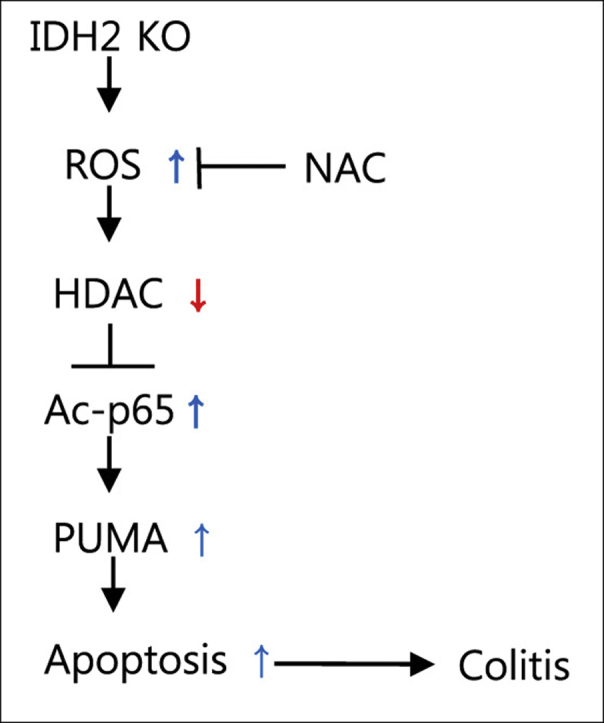

Protective effects of NAC against DSS-induced colitis. NAC (100 mg/kg) was injected into mice for 3 consecutive days before DSS administration and treatment was continued during DSS administration for 7 consecutive days. (A) DAI scores were evaluated for 7 consecutive days. (B) Colon lengths of IDH2-/- and IDH2+/+ mice. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of colon tissues. (D) The average histological score for each element. (E) TUNEL staining of colon tissues. (F) Immunohistochemical staining of PUMA in colon tissues. (G) Immunofluorescent staining of acetyl-p65, (H) acetyl-H3, and (I) acetyl-H4 in colon tissues. Histograms represent the quantification of fluorescence intensity. The figure shows representative data of 3–6 independent experiments. Results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3–6 mice of each group). *P<0.05, versus DSS-treated wild-type mice. (J) Schematic diagram summarizing that IDH2 deficiency promotes an increase in the level of ROS, which suppresses the activity of HDAC. The low activity of HDAC enhances acetylation level of p65, a NF-κB subunit, which in turn, induces PUMA-mediated apoptosis. This axis was inhibited by the scavenging of ROS by NAC.

In summary, in this present study, we show that IDH2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis, possibly due to modulation of the redox status, with a concomitant increase in PUMA-mediated apoptosis presumably through the PUMA/NF-κB/HDAC axis. The present study supports the rationale of targeting IDH2 as an important cancer chemoprevention strategy, particularly in the prevention of colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (Grant No. NRF-2015R1A4A1042271).

Contributor Information

Jin Hyup Lee, Email: jinhyuplee@korea.ac.kr.

Jeen-Woo Park, Email: parkjw@knu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Xavier R.J., Podolsky D.K. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podolsky D.K. Inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:928–937. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109263251306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada S., Koyama T., Noguchi H., Ueda Y., Kitsuyama R., Shimizu H., Tanimoto A., Wang K.Y., Nawata A., Nakayama T., Sasaguri Y., Satoh T. Marine hydroquinone zonarol prevents inflammation and apoptosis in dextran sulfate sodium-induced mice ulcerative colitis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouma G., Strober W. The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:521–533. doi: 10.1038/nri1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andus T., Gross V. Etiology and pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease--environmental factors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rezaie A., Parker R.D., Abdollash M. Oxidative stress and pathogenesis of infammatory bowel disease: an epiphenomenon or the cause? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007;52:2015–2021. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boismenu R., Chen Y. Insights from mouse models of colitis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000;67:267–278. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieleman L.A., Palmen M.J., Akol H., Bloemena E., Peña A.S., Meuwissen S.G., Van Rees E.P. Chronic experimental colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) is characterized by Th1 and Th2 cytokines. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998;114:385–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz-Granados N., Howe K., Lu J., McKay D.M. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced colonic histopathology, but not altered epithelial ion transport, is reduced by inhibition of phosphodiesterase activity. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:2169–2177. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65087-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelblum K.L., Yan F., Yamaoka T., Polk D.B. Regulation of apoptosis during homeostasis and disease in the intestinal epithelium. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2006;12:413–424. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217334.30689.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwamoto M., Koji T., Makiyama K., Kobayashi N., Nakane P.K. Apoptosis of crypt epithelial cells in ulcerative colitis. J. Pathol. 1996;180:152–159. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199610)180:2<152::AID-PATH649>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagiwara C., Tanaka M., Kudo H. Increase in colorectal epithelial apoptotic cells in patients with ulcerative colitis ultimately requiring surgery. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2002;17:758–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu W., Wu B., Wang X., Buchanan M.E., Regueiro M.D., Hartman D.J., Schoen R.E., Yu J., Zhang L. PUMA-mediated intestinal epithelial apoptosis contributes to ulcerative colitis in humans and mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011;121:1722–1732. doi: 10.1172/JCI42917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araki Y., Mukaisyo K., Sugihara H., Fujiyama Y., Hattori T. Increased apoptosis and decreased proliferation of colonic epithelium in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Oncol. Rep. 2010;24:869–874. doi: 10.3892/or.2010.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranganathan P., Jayakumar C., Li D.Y., Ramesh G. UNC5B receptor deletion exacerbates DSS-induced colitis in mice by increasing epithelial cell apoptosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014;18:1290–1299. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norbury C.J., Hickson I.D. Cellular responses to DNA damage. Annu. Rev. Phamacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:367–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D.R. Schultz, W.J. Harringto, Apoptosis: programmed cell death at a molecular level. In Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism (Vol. 32, No. 6, pp. 345-369). WB Saunders, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Circu M.L., Aw T.Y. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apel K., Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray P.D., Huang B.W., Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halliwell B., Gutteridge J.M. Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem. J. 1984;219:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2190001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limón-Pacheco J., Gonsebatt M.E. The role of antioxidants and antioxidant-related enzymes in protective responses to environmentally induced oxidative stress. Mut. Res. 2009;674:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MatÉs J.M., Pérez-Gómez C., De Castro I.N. Antioxidant enzymes and human diseases. Clin. Biochem. 1999;32:595–603. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(99)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jo S.H., Son M.K., Koh H.J., Lee S.M., Song I.H., Kim Y.O., Lee Y.S., Jeong K.S., Kim W.B., Park J.W., Song B.J., Huh T.L. Control of mitochondrial redox balance and cellular defense against oxidative damage by mitochondrial NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:16168–16176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustacich D., Powis G. Thioredoxin reductase. Biochem. J. 2000;346:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim H., Kim S.H., Cha H., Kim S.R., Lee J.H., Park J.W. IDH2 deficiency promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and dopaminergic neurotoxicity: implications for Parkinson's disease. Free Rad. Res. 2016;50:853–860. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2016.1185519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ku H.J., Ahn Y., Lee J.H., Park K.M., Park J.W. IDH2 deficiency promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;80:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S., Kim S.Y., Ku H.J., Jeon Y.H., Lee H.W., Lee J., Kwon T.K., Park K.M., Park J.W. Suppression of tumorigenesis in mitochondrial NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase knockout mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X.F., Li A.M., Li J., Lin S.Y., Chen C.D., Zhou Y.L., Wang X., Chen C.L., Liu S.D., Chen Y. Low molecular weight heparin relieves experimental colitis in mice by downregulating IL-1β and inhibiting syndecan-1 shedding in the intestinal mucosa. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murano M., Maemura K., Hirata I., Toshina K., Nishikawa T., Hamamoto N., Sasaki S., Saitoh O., Katsu K. Therapeutic effect of intracolonically administered nuclear factor κB (p65) antisense oligonucleotide on mouse dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2000;120:51–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erichsen K., Milde A.M., Arslan G., Helgeland L., Gudbrandsen O.A., Ulvik R.J., Berge R.K., Hausken T., Berstad A. Low-dose oral ferrous fumarate aggravated intestinal inflammation in rats with DSS-induced colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2005;11:744–748. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000174374.83601.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farooq S.M., Stadnyk A.W. Neutrophil infiltration of the colon is independent of the FPR1 yet FPR1 deficient mice show differential susceptibilities to acute versus chronic induced colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012;57:1802–1812. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang P., Qiu W., Dudgeon C., Liu H., Huang C., Zambetti G.P., Yu J., Zhang L. PUMA is directly activated by NF-κB and contributes to TNF-α-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1192–1202. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoesel B., Schmid J.A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2013;12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Q., Verna I.M. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L.F., Fischle W., Verdin E., Greene W.C. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Sciemce. 2001;293:1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1062374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiernan R., Brès V., Ng R.W., Coudart M.P., El Messaoudi S., Sardet C., Jin D.Y., Emiliani S., Benkirane M. Post-activation turn-off of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription is regulated by acetylation of p65. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2758–2766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman I., Marwick J., Kirkham P. Redox modulation of chromatin remodeling: impact on histone acetylation and deacetylation, NF-κB and pro-inflammatory gene expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;68:1255–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito K., Hanazawa T., Tomita K., Barnes P., Adcock I.M. Oxidative stress reduces histone deacetylase 2 activity and enhances IL-8 gene expression: role of tyrosine nitration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;315:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bharath S., Hsu M., Kaur D., Rajagopalan S., Andersen J.K. Glutathione, iron and Parkinson's disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:1037–1048. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chai Y.C., Ashraf S.S., Rokutan K., Johnston R.B., Thomas J.A. S-thiolation of individual human neutrophil proteins including actin by stimulation of the respiratory burst: evidence against a role for glutathione disulfide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;310:273–281. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins A.R., Horváthová E. Oxidative DNA damage, antioxidants and DNA repair: applications of the comet assay. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2001;29:337–341. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aruoma O.I., Halliwell B., Hoey B.M., Butler J. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1989;6:593–597. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]