Highlights

-

•

Comparative degradation of DBP by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F.

-

•

Degradation in MSM and contaminated samples.

-

•

Kinetics of DBP degradation.

-

•

Stoichiometry of DBP degradation and biomass formation.

-

•

Phthalate esters genes identification.

Keywords: Phthalate ester degradation, Endocrine disruptors, Degradation kinetics, Stoichiometry, Gene identification

Abstract

Dibutyl phthalate is (DBP) the top priority toxicant responsible for carcinogenicity, teratogenicity and endocrine disruption. This study demonstrates the DBP degradation capability of the two newly isolated bacteria from municipal solid waste leachate samples. The isolated bacteria were designated as Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F after scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, Gram-staining, antibiotic sensitivity tests, biochemical characterization, 16S-rRNA gene identification and phylogenetic studies. They were able to grow on DBP, benzyl butyl phthalate, monobutyl phthalate, diisodecyl phthalate, dioctyl phthalate, and protocatechuate. It was observed that Pseudomonas sp. V21b was more efficient in DBP degradation when compared with Comamonas sp. 51F. It degraded 57% and 76% of the initial DBP in minimal salt medium and in DBP contaminated samples respectively. Kinetics for the effects of DBP concentration on Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F growth was also evaluated. Stoichiometry for DBP degradation and biomass formation were compared for both the isolates. Two major metabolites diethyl phthalate and monobutyl phthalates were identified using GC–MS in the extracts. Key genes were amplified from the genomes of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F. DBP degradation pathway was also proposed.

1. Introduction

Phthalic acid esters (PAEs) are a class of compounds which are used as plasticizers in plastics manufacturing. They are popular due to low costs and easy of fabrication [1]. These are added with polyvinyl chloride (PVC) to provide mechanical strength as well flexibility [2]. These plasticizers are widely distributed in building materials, food packaging, transportation, home furnishing, medical devices and cosmetic products [3]. They are also used in photographic films, lubricating oils, textile fabrics, medical devices and aerospace technology [4]. They are recalcitrant to degradation in the environment due to their low solubility [5]. DBP has been detected in various environments including soil, rivers [6], air [7], landfill leachates [8] and lake sediments [9].

PAEs have been listed as top priority toxicants by European Union, US EPA, and China Monitoring Committee [10]. PAEs are known for causing cancer and defects in reproductive development [11]. PAEs have been reported as toxicants for humans and they disrupt endocrine signaling [12]. They were reported for malformation of the reproductive tract, hypospadias, and cryptorchidism in mice [13]. They are known for irritation of the skin, blurred vision and stone formation in the bladder [14]. DBP is one of the most widely used PAE and it has been detected in various environments [15]. DBP is responsible for carcinogenicity, hepatotoxicity, and teratogenicity [16]. These plasticizers do not have a covalent interactions with PVC, therefore there is always a possibility for leaching of plasticizers to the environment [17]. After leaching, they reach the soil and groundwater. Being top priority toxicants, removal of DBP from the environment is a matter of concern.

Microbial degradation of PAEs is the most effective method for their degradation because the natural process of degradation such as photodecomposition and hydrolysis are not efficient [18]. It was concluded from the previous studies that aerobic degradation of PAEs is more efficient as compared to anaerobic degradation [19]. The researchers have reported biodegradation of PAEs by bacteria isolated from activated sludge, mangrove sediments and wastewater [20]. Degradation by pure cultures of microorganisms was reported for degradation of butyl-benzyl phthalate [21]. Degradation of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate was reported in wastewater treatment systems [22]. A few papers described the identification of microorganisms on biodegradability of DBP by pure cultures [23]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PP4, Pseudomonas sp. PPD were reported for degradation of phthalate ester isomers [18]. Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas aureofaciens were reported for degradation of dimethyl phthalate ester at 400 mg/L [24]. Plasmid-mediated degradation of ortho and para phthalate ester was reported for Pseudomonas fluorescens [25]. Biodegradation of the DBP by Pseudomonas fluorescens B-1 was also reported [15]. Comamonas acidovoran Fy-1 was reported for degradation of dimethyl phthalate at higher concentrations [26].

Despite the studies reported for DBP biodegradation by the bacteria from genus Comamonas and Pseudomonas, these studies are inefficient in explaining (i) the mechanism of DBP degradation by the bacteria (ii) degradation of the DBP in the environmental samples collected from the PAEs contaminated sites (iii) kinetics of DBP degradation and (iv) stoichiometry of DBP degradation. The above-unsolved problems compel the scientific community to perform extensive and detailed studies on phthalate esters degradation to remove these pollutants from the environments.

This study is an endeavor to compare the two newly isolated DBP degraders, which have shown efficient DBP degradation capability individually in both the minimal salt medium supplemented with DBP in the laboratory and in the DBP contaminated samples collected from the environmental site.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Substrates used for the growth of bacteria including DBP, dioctyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate, protocatechuate, mono-butyl phthalate and di-isobutyl phthalate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. HPLC grade solvents including acetonitrile and isopropyl alcohol were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Isolation and characterization of DBP degrading bacteria

DBP degrading bacteria were isolated using enrichment culture method. For isolation of DBP degrading bacteria, leachate was collected from Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) landfill site at Ghazipur, New Delhi (location co-ordinates 28∘ 37′ 22.4′’N and 77∘ 19′ 25.7′’E). The physical parameters of the samples were pH 8.4, COD 31600, TDS 29700, Cl 1174.2 and Fe 9.81. Collected samples were stored at 4 °C until use. In the enrichment culture a minimal salt medium (MSM) with composition 3.5 g K2HPO4, 1.5 g KH2PO4, 0.27 g MgSO4, 1 g NH4Cl, 0.03 g Fe2(SO4)3·7H2O and 0.03 g CaCl2 in 1 l distilled water was prepared. MSM was adjusted to pH 6.8, autoclaved at 121 °C and 15 psi for 20 min. To avoid the precipitate formation in the MSM a separate trace element solution containing magnesium sulfate and iron sulfate was prepared. The prepared solution was filter sterilized with membrane filter (Merck Millipore, pore diameter 0.22 μm) [27]. In an Erlenmeyer flask 100 ml MSM, 1 ml trace element solution and 1 ml MSW leachate was added. DBP has very low solubility in aqueous solutions, therefore, DBP was emulsified with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 80 and added to the MSM medium in Erlenmeyer flask at 10–2000 mg/L. After addition, the flasks were incubated in shaking incubator at 30 °C and 180 rpm. After 48 h, the culture from the flask was spreaded on MSM agar plates with DBP as sole carbon source. A single isolated colony was sub cultured in fresh MSM medium supplemented with DBP as sole carbon source and again culture was spreaded on MSM agar plates. Sub culturing procedure was repeated seven times. Two isolated colonies numbered 21b and 51F were selected for further studies.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to examine the surface morphology of 21b and 51F. To observe the internal features of the bacteria, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used. SEM and TEM of strains 21b and 51F were performed at Advanced Instrumentation Research Facility (AIRF), Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. For analyzing bacterial cells in electron microscopy, cells were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde for 3 h at room temperature. After washing with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, post-fixation of the cells was performed in 2% osmium tetroxide solution [28]. The ability to retain Gram-stain by the bacteria was tested using Gram-stain kit from Hi-Media Lifesciences. Biochemical characterization of the bacteria was performed with biochemical tests [29]. Catalase activity was performed by assessment of bubble production in 3% (v/v) H2O2 [30]. Oxidase activity was examined using 1% (w/v) tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine from Himedia lifesciences [30]. Arginine dihydrolase was performed according to the method described earlier [31]. Indole production and Voges–Proskauer tests were performed as described earlier [32]. Citrate utilization, lipase production, and nitrate reduction were carried out as described earlier [33]. Urease production was determined by the method described earlier [34]. Susceptibility of the bacteria towards antibiotics was tested by spreading the bacterial suspension on MSM agar plates supplemented with 10–100 μg/mL of antibiotic tested. Benzene ring cleavage by the bacteria was examined using Rothera‘s test. For Rothera‘s test 5 ml bacterial culture saturated with solid ammonium sulfate was mixed with few drops of 2% sodium nitroprusside solution and liquor ammonia. The appearance of a bluish-purple ring after 15 min incubation, indicates the presence of the ketone bodies in it [35].

2.3. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of the isolates

Identification of strain 21b and strain 51F was performed by 16S-rRNA gene identification. Genomic DNA of the strain 21b and 51F was isolated using Fast DNA® SPIN Kit for soil from MP Bio. The 16S-rRNA gene was amplified using bacterial universal primers 27F and 1492R in PCR thermocycler [36]. The 50 μl PCR reaction contained 25 μl PCR master mix (Thermo Scientific), 2 μl forward primer, 2 μl reverse primers, 23 μl sterile water and 1 μl genomic DNA. PCR mixture was applied to Applied Biosystems Gene Amp PCR system 9700 with time programing, 10 min at 95 °C, 35 cycles of 60 s at 95 °C, 90 s at 54 °C, and 60 s at 72 °C and 5 min at 72 °C. The amplified gene products were gel purified with HiYield™ PCR DNA Mini Kit from Real Genomics™ (Ref catalog no. YDF100). Sequencing of the gel purified products was performed at DNA sequencing facility UDSC, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India. The method used for sequencing of the PCR products was di-deoxy termination method with bacterial universal primers: 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). After sequencing, the sequences were combined using BioEdit program. The resulting combined 16S-rRNA sequences were compared with the representative sequences from bacterial organisms in GenBank and aligned using CLUSTAL W [37]. Phylogenetic analyses were carried out with Maximum Composite Likelihood method [38] using MEGA version 5 [39]. The 16S-rRNA sequences of 21b and 51F were submitted to NCBI database with accession numbers KJ885186 and KJ918727 respectively.

2.4. Substrate utilization tests

The isolated strains 21b and 51F were examined for growth on substrates, including protocatechuic acid (PC), diethyl phthalate (DEP), dioctyl phthalate (DOP), benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP), monobutyl phthalate (MBP) and diisodecyl phthalate. These substrates were added at 2000 mg/L. The growth of strains 21b and 51F was measured with Perkin Elmer Lambda 25 UV/vis spectrophotometer at 600 nm.

2.5. Kinetics of DBP degradation by strains 21b and strain 51F

Kinetics of DBP degradation studies were carried out in 100 ml of sterile MSM containing trace element solution (pH adjusted to 6.8) with 1% inoculum. DBP at 1000–2000 mg/L concentration was added to the flasks as sole carbon source and no other carbon source was provided. After inoculation, the flasks were incubated at 30 °C and 180 revolutions per minute in incubator shaker. Residual DBP quantification and metabolic intermediates identification were performed by collecting samples from the running culture at every 24 h. The collected samples were extracted with ethyl acetate in 1:1 ratio. The obtained residue was dissolved in methanol and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. The filtrate obtained was used for analysis in HPLC and Gas Chromatography [40]. Quantification of the residual DBP was performed using Shimadzu HPLC system. The column used for the analysis was, Ascentis® C 18 column, 5 μm, 25 cm x 4.6 cm from Sigma-Aldrich. Two mobile phases were used: A-water/acetonitrile (15:85) v/v and B-100% acetonitrile. A gradient programing: 0 − 3 min 100% A and 6.5–19.5 min 100% B was used. Run time for the samples was 45 min and flow rate 0.6 ml/min was applied. DBP was detected with UV detector at 225 nm [41]. DBP standard curve in the range 10 mg/L to 100 mg/L was prepared to determine the concentration of residual DBP in the samples. Identification of the metabolic intermediates was performed with GC–MS system at Advanced Instrumentation Research Facility, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. In GC, Rtx-5MS—Low-Bleed GC Column was used with column temperature 100 °C, injection temperature 250 °C and total flow 16.3 ml/min. For determination of biomass in terms of dry weight, bacterial cells were harvested, filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter and dried in an oven at 100 °C. Dried biomass was measured with weighing balance [42].

2.6. Identification of phthalate esters degrading genes

Polymerase chain reaction was used for identification of genes responsible for phthalate esters degradation. Primers used for the amplification of PAEs degradation are listed in Table 1. Time programing used for thermo cycler was: 5 min at 95 °C, 30 cycles for 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at Tm of corresponding primers, 90 s at 72 °C and final extension for 7 min at 72 °C [43]. After amplification, the amplified products were gel purified and sequenced at DNA sequencing facility UDSC, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India. Sequencing of the amplicons was performed with specific primers for each gene and amplicons were cloned into an M13 vector.

Table 1.

Primers used for identification of PAEs degrading genes.

| Primer name | Gene name | References |

|---|---|---|

| Oph A1/A2 | Phthalate 4,5 dioxygenase reductase | [43] |

| Oph B | Phthalate dihydrodiol dehydrogenase | [43] |

| Oph C | 3,4-Dihydroxyphthalate decarboxylase | [43] |

| Oph D | d-galactonate transporter | [43] |

| Tph A2 | Terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase oxygenase component large subunit | [43] |

| Tph A3 | Terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase oxygenase component small subunit | [43] |

| Tph B | Terephthalate dihydrodiol dehydrogenase | [43] |

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by F-test and one-way ANOVA with three replicates data using data analysis tool pack in Microsoft excel. The hypothesis was made at 5% level of significance to calculate P and F values.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Isolation and characterization of the bacteria

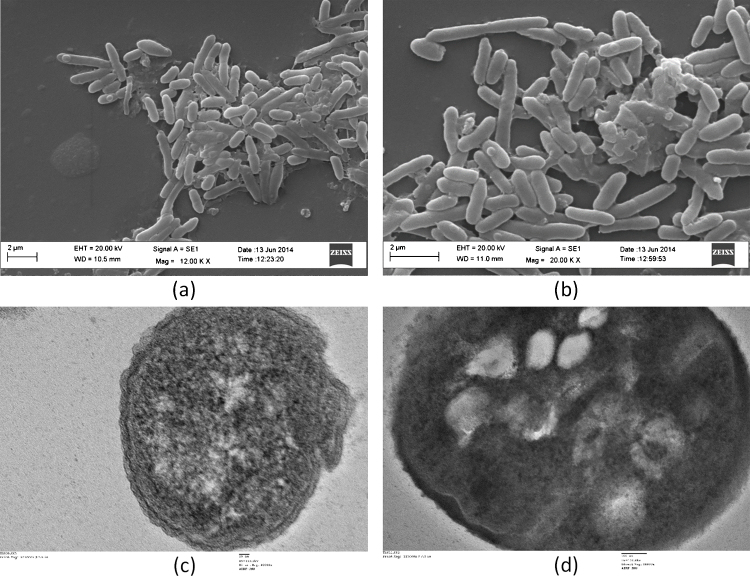

PAEs degrading bacteria were isolated as described in the materials and methods. The isolated bacteria were identified using Gram-staining, biochemical characterization, SEM and TEM. Strain 21b was rod-shaped, aerobic, without flagella and Gram- negative. It was positive for catalase, citrate utilization, oxidase, lipase and protease. It was negative for indole, methyl red and Voges-Proskauer. Strain 51F was rod-shaped, aerobic, without flagella and Gram-negative. It was positive for oxidase, catalase, urease and citrate utilization. It was negative for arginine dihydrolase, β-galactosidase, β-glucosidase, glucose fermentation, lysine decarboxylase, ornithine decarboxylase, nitrate reduction, hydrogen sulfide production and indole test. Strain 21b was resistant to chloramphenicol (100 μg mL−1) and susceptible to ampicillin (10 μg mL−1), penicillin (10 μg mL−1), kanamycin (10 μg mL−1), tetracycline (10 μg mL−1), and streptomycin (10 μg mL−1). The features observed from the SEM of strain 21b is presented in Fig. 1(a). SEM at 12 KX revealed that strain 21b was rod-shaped, smooth, without flagella with length ∼1.5 μm and width ∼0.4 μm. TEM of strain 21b is presented in Fig. 1(c). TEM of strain 21b at 40 KX revealed the presence of outer membrane, peptidoglycan layer and plasma membrane in it. Strain 51F was resistant to chloramphenicol (100 μg mL−1), ampicillin (10 μg mL−1), penicillin (10 μg mL−1) and kanamycin (10 μg mL−1). It was susceptible to tetracycline (10 μg mL−1) and chloramphenicol (10 μg mL−1). The features observed from the SEM of strain 51F is presented in Fig. 1(b). SEM at 20 KX revealed that strain 51F was rod-shaped, smooth, without flagella with length ∼2.5 μm and width ∼0.5 μm. TEM of strain 51b is presented in Fig. 1(d). TEM of strain 21b at 20 KX revealed that outer membrane, peptidoglycan layer and plasma membrane were not distinguishable. In the center of the bacterium, vacuole type structures were observed.

Fig. 1.

(a) Scanning electron micrograph of strain 21b. Scale bar 2 μm. (b) Scanning electron micrograph of strain 51F. Scale bar 2 μm.(c) Transmission electron micrograph of strain 21b. Scale bar 20 nm. (d) Transmission electron micrograph of strain 51F. Scale bar 100 nm.

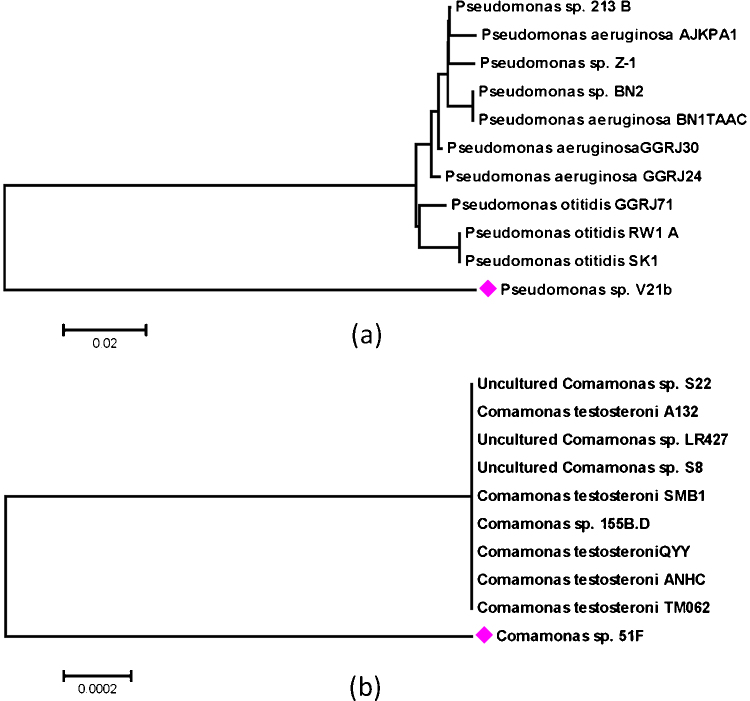

The 16S-rRNA gene sequences obtained from the strains 21b and 51F were compared with the nucleotide sequences present in the NCBI database. It was observed that 16S-rRNA gene sequence of strain 21b, found the maximum identity with [43] (Accession number (GU204968.1)). Therefore, strain 21 B was designated as Pseudomonas sp. V21b. Fig. 2(a) presents the phylogenetic relationship of Pseudomonas sp. V21b with other bacterial sequences present in the NCBI nucleotide database. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) are shown above the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths (below the branches) in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. Codon positions included were 1st + 2nd + 3rd + Noncoding. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the dataset (Complete deletion option). There were a total of 1281 positions in the final dataset. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA5. The values like 0.002, 0.004 denotes evolutionary distance between different species and values such as 99 and 100 denotes the similarities between different species. Similarly, 16S-rRNA gene sequence from strain 51F on comparison with nucleotide sequences present in NCBI database, found the maximum identity with (Accession number KM462142.1). Therefore, strain 51F was designated as Comamonas sp. 51F. Fig. 2(b) presents the phylogenetic relationship of Comamonas sp. 51F with other bacterial sequences present in the NCBI nucleotide database.

Fig. 2.

(a) Phylogenetic tree of Pseudomonas sp. V21b. (b) Phylogenetic tree of Comamonas sp. 51F. The evolutionary history was inferred using the UPGMA method.

3.2. Substrate utilization tests

Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F were able to grow on substrates protocatechuate, benzyl butyl phthalate, monobutyl phthalate, dioctyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate and dodecyl phthalate (Table 2). The growth of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F decreases as the length and complexity of hydrocarbon attached to the phthalate molecule increases [26]. The observed growth for Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F was higher in substrates PC, MBP and DEP. The growth was maximum on PC and it was minimum for diisodecyl phthalate for both Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F.

Table 2.

Growth of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F in different substrates. PC-protocatechuate, MBP-monobutyl phthalate, DEP-diethyl phthalate, BBP-benzyl butyl phthalate, DOP-dioctyl phthalate and DIDP-diisodecyl phthalate.

| Strain name | Pseudomonas sp. V21b | Comamonas sp. 51F |

|---|---|---|

| PC | +++ | +++ |

| MBP | + | +++ |

| DEP | + | +++ |

| BBP | + | + |

| DOP | + | + |

| DIDP | + | + |

3.3. DBP biodegradation in MSM by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F

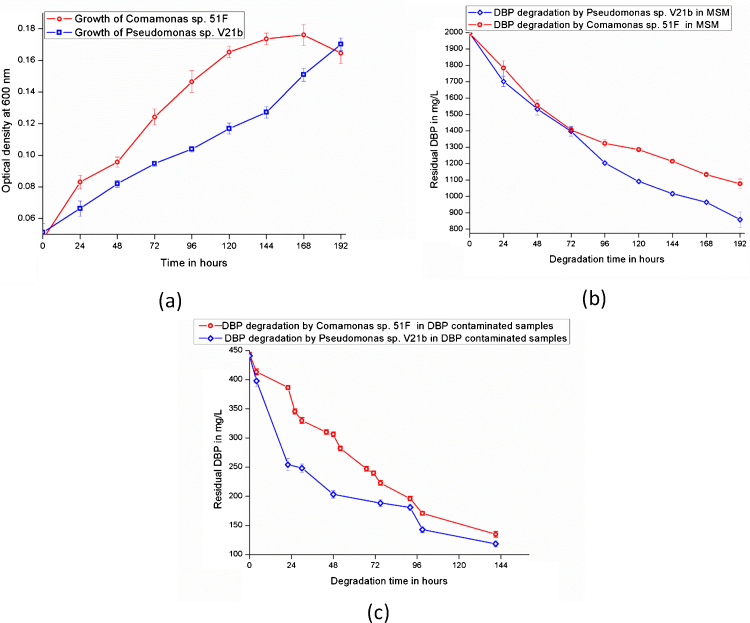

DBP biodegradation studies were conducted by growing Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F. On comparing the growth patterns of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F, it was observed that Pseudomonas sp. V21b grows at relatively steady rate from 0 h to 144 h. An increase in the growth was observed from 144 h to 192 h (Fig. 3(a)). From the growth curve of Comamonas sp. 51F, it was observed that there was an increase in the growth from 0 h to 24 h. A decrease in the growth was observed until 48 h, and after 48 h’ exponential growth phase was observed until 168 h. After 168 h a decline phase was observed without appearance of stationary phase.

Fig. 3.

(a) Comparative growth of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F. (b) Comparative degradation of DBP by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F in MSM. (c) Comparative degradation of DBP by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonassp. 51F in DBP contaminated samples.

Biodegradation of DBP by Pseudomonas sp. V21band Comamonas sp. 51F were examined in the MSM supplemented with DBP (Fig. 3(b)). From the figure, it was observed that at 0 h, Pseudomonas sp. V21b started degradation of DBP with an initial 1994 mg/L. After 24 h, 72 h, 144 h, and 192 h the amount of residual DBP calculated was 1702 mg/L, 1396 mg/L, 1016 mg/L, and 857 mg/L respectively. It was concluded from the DBP degradation by Pseudomonas sp. V21b in MSM that it degraded 57% DBP in 192 h. At 0 h, Comamonas sp. 51F started degradation of DBP with an initial 1994 mg/L. After 24 h, 72 h, 144 h, and 192 h the amount of DBP calculated was 1782 mg/L, 1405 mg/L, 1214 mg/L, and 1077 mg/L respectively. It was concluded from DBP degradation by Comamonas sp. 51F in MSM that it degraded 46% DBP in 192 h. DBP degradation was reported by researchers in bacteria from different genus such as Sphigomonas sp. DK4 (5 mg/L) [44], Pseudomonas fluorescens B-1(2.5 & 10) [15], Acinetobacter lwoffii (1000 mg/L) [45], Corynebacterium nitilophius G11 (100 mg/L), R. rhodochrous G2, G7 (100 mg/L) and R. Coprophilus G5, G9 (100 mg/L) [46]. The isolates identified in the study were able to degrade very high concentration of DBP i.e. 1994 mg/L. This amount is very high as reported in the previous studies. From the DBP biodegradation studies of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F in MSM supplemented with DBP as sole carbon source, it was observed that Pseudomonas sp. V21b was a faster degrader as compared to Comamonas sp. 51F.

3.4. DBP biodegradation in contaminated samples by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F

DBP degradation potentials of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F was examined in samples contaminated with DBP. While a majority of the studies were concentrated on the degradation of PAEs in minimal media [19], [46], this study focuses on DBP degradation in contaminated samples collected from a landfill site. For the experiment, DBP contaminated samples in liquid state were collected from the landfill site at Ghazipur, New Delhi, India. The amount of DBP was quantified using HPLC system and calculated DBP concentration in the contaminated samples was 441 mg/L. Fig. 3(c) presents the DBP degradation by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F in DBP contaminated samples. It was observed that, from an initial DBP 441 mg/L present in contaminated sample, Pseudomonas sp. V21b degraded half of it in 48 h and at the end of 144 h, only 110 mg/L DBP was left. Pseudomonas sp. V21b degraded 76% of the initial DBP in 144 h. It was also observed from Fig. 3(c) that Comamonas sp. 51F degraded approximately half of the DBP in 72 h and at the end of 144 h, only 135 mg/L was present. Comamonas sp. 51F degraded 69% of the initial DBP in 144 h. Therefore, from the biodegradation studies of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F in the samples contaminated with DBP it was observed that Pseudomonas sp. V21b was a fast degrader as compared to Comamonas sp. 51F.

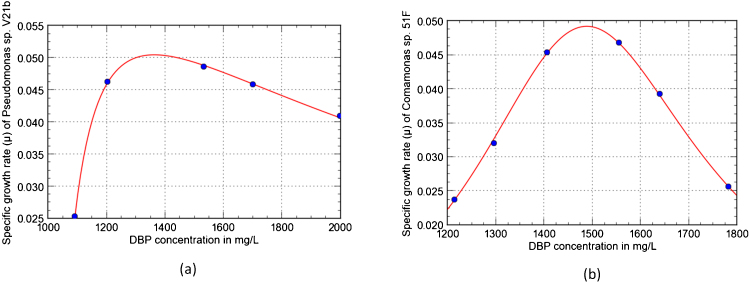

3.5. Biodegradation kinetics and DBP degradation stoichiometry

Researchers have reported degradation kinetics of phthalate esters by using various models. For example, degradation kinetics of organic pollutants were explained by first order equations in different studies [15], [47]. In another study, a second order equation was reported for degradation of phthalate esters by algae Chlorella pyrenoidosa [48]. DBP degradation was also reported by a modified Gompertz model in Gordonia sp. QH-11 [49]. In a continuous culture system, Haldane substrate inhibition model was used to explain DBP degradation [50]. DBP Biodegradation kinetics by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F were explained by drawing a plot of specific growth rate (μ) and DBP concentration (Sav.). Fig. 4a presents the effect of increase in DBP concentration on the specific growth rate (h−1) for Pseudomonas sp. V21b. Fig. 4b presents the effect of increase in DBP concentration on the specific growth rate (h−1) for 51F. From Fig. 4(a), it was observed that as the concentration of DBP increased up to ∼1300 mg/L, there was an increase in the specific growth rate of Pseudomonas sp. V21b but a decrease in the specific growth rate was observed after 1300 mg/L. In case of Comamonas sp. 51F (Fig. 4(b)), an increase in the growth rate of Comamonas sp. 51F was observed until DBP ∼1500 mg/L, but a decrease in specific growth was observed after it. The kinetics reported here is a rational model which is a different perspective for presenting growth kinetics.

Fig. 4.

(a) DBP degradation kinetics of Pseudomonas sp. V21b. (b) DBP degradation kinetics of Comamonas sp. 51F.

Calculation of stoichiometry for substrate consumption and biomass formation was performed using dry weight estimation method. Dry weight calculation from the both Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F was used to calculate yield using the Eq. (1) [51].

| (1) |

Calculated yield for Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F were 0.37 and 0.35 respectively.

Stoichiometry for DBP utilization and biomass formation by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F is presented in Eqs. (2) & (3). The Eqs. (2) and (3) were derived from the standard equations of bacterial substrate and biomass estimations [51].

| (2) |

| (3) |

From the Eq. (2) it was observed that for every 100 g DBP consumed by the bacteria, 37 g biomass was produced by Pseudomonas sp. V21b. Similarly, from the Eq. (3) it was observed that for every 100 g DBP consumed by the bacteria 35 g biomass was produced by Comamonas sp. 51F. In another study, Acinetobacter sp. 33F produced 43 g biomass for every 100 g DBP consumed [52]. Therefore, the biomass production by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F was less as compared to Acinetobacter sp. 33F.

3.6. Identification of the metabolic intermediates

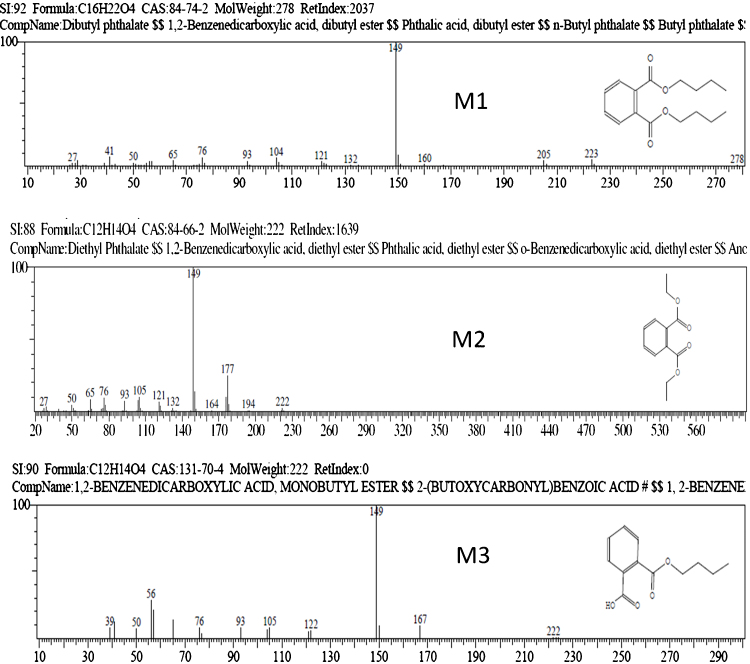

Transformation of DBP by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F were determined by analyzing the GC–MS results. For the analysis, samples were collected at 24 h’ intervals from the running culture in the flasks. After analyzing the samples collected for DBP degradation by Pseudomonas sp. V21b, diethyl phthalate was identified as major intermediate compond. The metabolites were identified by comparing the mass spectrum at a particular retention time (RT) with published mass spectra from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database. Similarly, for Comamonas sp. 51F, two major intermediates diethyl phthalate and monobutyl phthalate were identified (Fig. 5). The m/z ratio determined by mass spectrometry for DBP (M1) (RT 12.49) were 41, 76, 104, 149, 205, 223, and 278. The m/z ration observed for diethyl phthalate (M2)(RT 10.20) were 222, 177 and 149. Similarly, the m/z ratio observed for monobutyl phthalate (M3)(RT 10.70) were 167, 149 and 56. Fig. 5 presents the metabolic intermediates identified in DBP degradation by 21b and 51F.

Fig. 5.

DBP degradation metabolic intermediates identified by GC–MS. Structure and m/z ratio of the identified metabolic intermediates. M1- dibutyl phthalate, M2-diethyl phthalate, and M3-monobutyl phthalate.

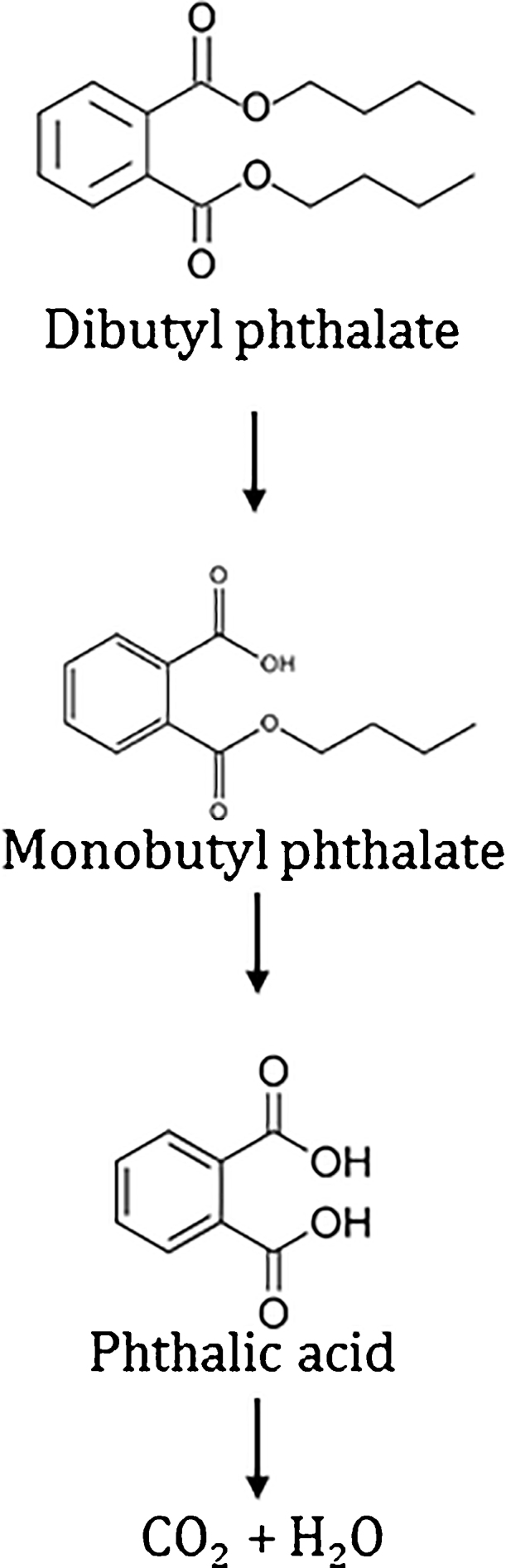

The pathway for degradation of PAEs consists of two steps: the first step converts phthalate di-esters to Phthalic acid (PA) via phthalate mono esters as the intermediate and in the second step, PA is converted to carbon dioxide or methane [6]. The first step is common in both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria [53]. The intermediate, PA is the central intermediate in biodegradation pathway for different substrates including fluorine [54], fluoranthene [55] and phenanthrene [56]. In aerobic conditions, PA is converted to a common intermediate known as protocatechuate [57]. Ring cleavage enzymes act on protocatechuate through either ortho-or meta-cleavage pathway for further degradation [23]. From the previously reported studies, it was observed that DBP is first converted to its monomer monobutyl phthalate (MBP) by an esterase and then monobutyl phthalate was converted to phthalic acid (PA)[20]. In the next step, PA is converted to 3,4 dihydroxy benzoic acid (protocatechuate). Protocatechuate (PC) is converted to carbon dioxide and water in the subsequent steps [58]. Protocatechuate is one of the important intermediates in various pathways including phthalates [55]. Protocatechuate then enters Krebs cycle after conversion to pyruvate and carbon dioxide. Protocatechuate is also present in benzoate degradation pathway [59]. In a study, it was reported that the cleavage of two ester linkages in phthalate molecules is mediated by the mutual association of two different bacteria [20]. In another study dimethyl, phthalic acid and dimethyl terephthalate were mineralized by Klebsiella oxytoca Sc and Methylobacterium mesophilium sr. The rate of dimethyl terephthalate degradation by Pasteurella multocida Sa and Sphingomonas paucimoblis SY were different [20].

A similar pathway for DBP degradation in landfill bioreactor was reported for Enterobacter sp. T5 isolated from municipal solid waste [19]. The study described the appearance of two major transient metabolites including phthalic acid (PA) and monobutyl phthalate (MBP). The degradation of DBP by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F in this study is different due to the appearance of diethyl phthalate. The metabolic intermediates identified in other studies such as PA and PC were not detected in this study. The reason for non-appearance of these compounds may be their short half-lives. Due to their short lives, they may have appeared for very short duration of time which is undetectable during sampling duration.The identified intermediate, MBP was produced by ester hydrolysis and DEP is produced by transesterification [27]. The final step of DBP degradation is the cleavage of PC ring. The appearance of positive Rothera‘s test, confirmed the cleavage of the benzene ring to produce carbon dioxide and water.

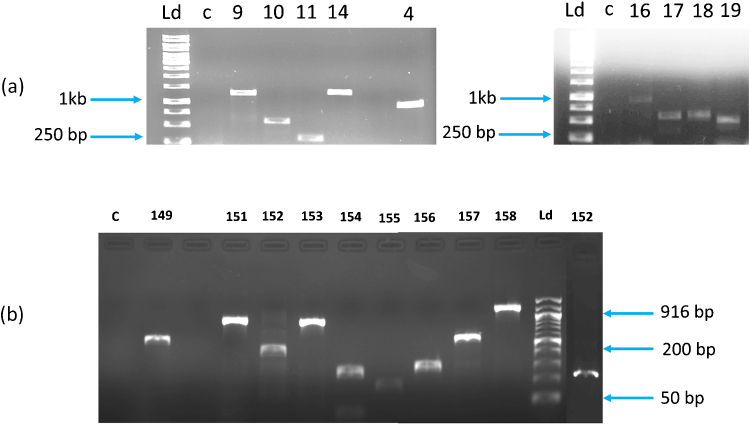

3.7. Identification of phthalates degrading genes

Molecular identification of major genes responsible for phthalate esters degradation pathway was performed to identify their role in the pathway. The genes were amplified using PCR. Table 3 presents the name of the genes and the size of amplicons amplified. The amplified genes are presented in Fig. 6. The genes amplified from the genomes of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F are Oph-A1/A2, Oph-B, Oph-C, Oph-D, Tph-A2, Tph-A3, and Tph-B. Oph-D codes for phthalate permease and it is responsible for transport of phthalate esters inside the bacterial cells. They belong to the major facilitator superfamily of proteins with twelve hydrophobic helices which are supposed to embed in the membrane to facilitate transport [60]. Similar permeases have been reported in P. putida NMH102-2 and B. cepacia ATCC 17616 [61]. These permeases were reported as operon consisting of multiple genes [9]. Oph-A1 codes for phthalate dioxygenase reductase and it catalyzes the introduction of two hydroxyl groups on the phthalate ester ring to yield phthalate dihydrodiols [55]. It is an iron-sulfur flavoprotein and accomplishes electron transfer from the reduced nicotinamide adenine nucleotide (NADH) to the one-electron acceptor, [2Fe-2S] [62]. Oph-B codes for Phthalate dihydrodiol dehydrogenase which dehygrogenates cis-4,5-dihydroxy-4,5-dihydrophthalate to 4,5-dihydroxyphthalate. Oph-C codes for 4,5-dihydroxyphthalate decarboxylase which decarboxylates the 4,5-dihydroxyphthalate to produce 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate or protocatechuate [63]. Tph-A2 codes for terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase oxygenase component large subunit and Tph-A3 codes for terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase oxygenase component small subunit. These enzymes catalyze double hydroxylation at positions 1 and 2 in the terephthalate molecule to produce 2-hydro-1,2-dihydroxy terephthalic acid [59]. In subsequent reactions, the 2-hydro-1,2-dihydroxy terephthalic acid is converted to 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate. This reaction is catalyzed by Tph-B which codes for terephthalate dihydrodiol dehydrogenase [18]. Based on the metabolic intermediates identified from the biodegradation of DBP by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F, a pathway for degradation of DBP is proposed (Fig. 7) [20], [53], [57].

Table 3.

Phthalate degrading genes identified from the genomes of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F.

| Amplicon number | Gene name | Enzyme name | Amplicon size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. V21b | |||

| 4 | Oph-B | Phthalate dehydrogenase | 1 kb |

| 9 | Tph-A2-N1,C1 | Terephthalate dioxygenase | 1.2 kb |

| 10 | Tph-B-F2,R3 | Terephthalate dehydroxygenase | 500 bp |

| 11 | Tph-B-F2,R1 | Terephthalate dehydroxygenase | 300 bp |

| 14 | Oph-C | Phthalate decarboxylase | 1 kb |

| 16 | Oph-D | Phthalate permease | 1 kb |

| 17 | Oph-A1 | Phthalate dioxygenase reductase | 500 bp |

| 18 | Tph-B-F1,R1 | Terephthalate dehydroxygenase | 500 bp |

| 19 | Tph-B-F2,R2 | Terephthalate dehydroxygenase | 500 bp |

| Comamonas sp. 51F | |||

| 149 | Tph-B-F2,R2 | Terephthalate dihydroxygenase | 500 bp |

| 151 | Oph-A1 | Phthalate dioxygenase reductase | 750 bp |

| 152 | OphD | Phthalate permease | 400 bp |

| 153 | TphB-F3,R3 | Terephthalate dihydroxygenase | 750 bp |

| 154 | OphC | Phthalate decarboxylase | 250 bp |

| 155 | Tph-A3 | Terephthalate dihydroxygenase | 150 bp |

| 156 | TphB-F3,R1 | Terephthalate dihydroxygenase | 300 bp |

| 157 | TphB-F2,R1 | Terephthalate dihydroxygenase | 500 bp |

| 158 | TphB-F2,R3 | Terephthalate dihydroxygenase | 1.2 kb |

Fig. 6.

Phthalate esters degrading genes amplified form the genomes of Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F. (a) Pseudomonas sp. V21b. (b) Comamonas sp. 51F. Ld-ladder, c-control, Oph-A1-17, 151, Oph-B-4, Oph-C-14, 154, Oph-D-16, 152, Tph-A2-9, Tph-A3-155 and Tph-B-155.

Fig. 7.

DBP degradation pathway based on the identified metabolic intermediates.

4. Conclusions

This study compares the degradation of DBP by two newly isolated bacteria designated as Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F. They are able to grow on other substrates protocatechuate, monobutyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate, benzyl butyl phthalate, dioctyl phthalate and diisodecyl phthalate in addition to DBP. Other studies have reported DBP degradation by first order equations, second order equations, modified Gompertz model and Haldane model, the DBP degradation by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F is presented here is a rational model which is a different perspective. While the majority of the studies are concentrated on the degradation of PAEs in minimal media, this study focuses on degradation of DBP in contaminated samples collected from the landfill site. The study also compares the stoichiometry of DBP degradation, biomass formation by Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F. From this study, it was confirmed that Pseudomonas sp. V21b is an efficient degrader of DBP in PAEs contaminated the sample, therefore it can be considered as a potential candidate for bioremediation of the sites contaminated with PAEs.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Jawaharlal Nehru University for providing the grant under university with the potential of excellence (UPOEI) scheme.

References

- 1.Edenbaum J. Polyvinyl chloride resins and flexible-compound formulating. Plast. Addit. Modifiers Handb. 1992:17–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baikova S. The intensification of dimethylphthalate destruction in soil. Eurasian Soil Sci. 1999;32(6):701–704. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niazi J.H., Prasad D.T., Karegoudar T. Initial degradation of dimethylphthalate by esterases from Bacillus species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;196(2):201–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross F.C., Colony J.A. The ubiquitous nature and objectionable characteristics of phthalate esters in aerospace technology. Environ. Health Perspect. 1973;3:p37. doi: 10.1289/ehp.730337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vikelsøe J., Thomsen M., Carlsen L. Phthalates and nonylphenols in profiles of differently dressed soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2002;296(1):105–116. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(02)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staples C.A. Aquatic toxicity of eighteen phthalate esters. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1997;16(5):875–891. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wensing M., Uhde E., Salthammer T. Plastics additives in the indoor environment—flame retardants and plasticizers. Sci. Total Environ. 2005;339(1):19–40. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Z. Phthalic acid esters in dissolved fractions of landfill leachates. Water Res. 2007;41(20):4696–4702. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jianlong W., Ping L., Yi Q. Microbial degradation of di-n-butyl phthalate. Chemosphere. 1995;31(9):4051–4056. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)00282-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi J., Gao J. Effects of Potamogeton crispus L. – bacteria interactions on the removal of phthalate acid esters from surface water. Chemosphere. 2015;119:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jobling S.et al. A variety of environmentally persistent chemicals, including some phthalate plasticizers, are weakly estrogenic. Environ. Health Perspect. 1995;103(6):582. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer A.M., Staples R.C. Laccase: new functions for an old enzyme. Phytochemistry. 2002;60(6):551–565. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher J.S. Environmental anti-androgens and male reproductive health: focus on phthalates and testicular dysgenesis syndrome. Reproduction. 2004;127(3):305–315. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y.P., Gu J.-D. Degradability of dimethyl terephthalate by Variovorax paradoxus T4 and Sphingomonas yanoikuyae DOS01 isolated from deep-ocean sediments. Ecotoxicology. 2006;15(6):549–557. doi: 10.1007/s10646-006-0093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu X.-R., Li H.-B., Gu J.-D. Biodegradation of an endocrine-disrupting chemical di-n-butyl phthalate ester by Pseudomonas fluorescens B-1. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2005;55(1):9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumoto M., Hirata-Koizumi M., Ema M. Potential adverse effects of phthalic acid esters on human health: a review of recent studies on reproduction. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 2008;50(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Psillakis E., Mantzavinos D., Kalogerakis N. Monitoring the sonochemical degradation of phthalate esters in water using solid-phase microextraction. Chemosphere. 2004;54(7):849–857. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vamsee-Krishna C., Mohan Y., Phale P. Biodegradation of phthalate isomers by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PP4: Pseudomonas sp. PPD and Acinetobacter lwoffii ISP4. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;72(6):1263–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang C.-R. Dibutyl phthalate degradation by Enterobacter sp. T5 isolated from municipal solid waste in landfill bioreactor. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2010;64(6):442–446. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu J.-D., Li J., Wang Y. Biochemical pathway and degradation of phthalate ester isomers by bacteria. Water Sci. Technol. 2005;52(8):241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y.-H. Enhanced degradation of an endocrine-disrupting chemical, butyl benzyl phthalate, by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi cutinase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68(9):4684–4688. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4684-4688.2002. (p) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ejlertsson J., Meyerson U., Svensson B. Anaerobic degradation of phthalic acid esters during digestion of municipal solid waste under landfilling conditions. Biodegradation. 1996;7(4):345–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00115748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton R.W., Ribbons D.W. Metabolism of dimethylphthalate by Micrococcus sp. strain 12B. J. Bacteriol. 1982;151(1):465–467. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.465-467.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y., Fan Y., Gu J. Degradation of phthalic acid and dimethyl phthalate by aerobic microorganisms. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2002;9(1):63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karpagam S., Lalithakumari D. Plasmid-mediated degradation of o-and p-phthalate by Pseudomonas fluorescens. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999;15(5):565–569. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y., Fan Y., Gu J.-D. Aerobic degradation of phthalic acid by Comamonas acidovoran Fy-1 and dimethyl phthalate ester by two reconstituted consortia from sewage sludge at high concentrations. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003;19(8):811–815. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vega D., Bastide J. Dimethylphthalate hydrolysis by specific microbial esterase. Chemosphere. 2003;51(8):663–668. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith K., Oatley C. The scanning electron microscope and its fields of application. Br. J. Appl. Phys. 1955;6(11):p391. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vos P. Vol. 3. Springer Science & Business Media; 2011. (Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology: Volume 3: The Firmicutes). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cappuccino Sherman J.G.N. Vol. 9. Pearson/Benjamin Cummings; Boston, MA: 2008. (Microbiology: a Laboratory Manual). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thornley M.J. The differentiation of Pseudomonas from other Gram-negative bacteria on the basis of arginine metabolism. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1960;23(1):37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smibert R. Phenotypic characterization. Methods Gen. Mol. Bacteriol. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hugh R., Leifson E. The taxonomic significance of fermentative versus oxidative metabolism of carbohydrates by various gram negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1953;66(1):p24. doi: 10.1128/jb.66.1.24-26.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrow G., Feltham R.K.A. Cambridge University Press; 2003. Cowan and Steel's Manual for the Identification of Medical Bacteria. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothera A.C.H. Note on the sodium nitro-prusside reaction for acetone. J. Physiol. 1908;37(5–6):p491. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1908.sp001285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weisburg W.G. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173(2):697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981;17(6):368–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura K. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin D.-C. Biodegradation of di-n-butyl phthalate by Rhodococcus sp. JDC-11 and molecular detection of 3: 4-phthalate dioxygenase gene. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;20(10):1440–1445. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1004.04034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thuren A. Determination of phthalates in aquatic environments. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1986;36(1):33–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01623471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bratbak G., Dundas I. Bacterial dry matter content and biomass estimations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984;48(4):755–757. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.755-757.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han R. Rutgers The State University of New Jersey-New Brunswick; 2008. Phthalate Biodegradation: Gene Organization, Regulation and Detection. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang B. Biodegradation of phthalate esters by two bacteria strains. Chemosphere. 2004;55(4):533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashizume K. Phthalate esters detected in various water samples and biodegradation of the phthalates by microbes isolated from river water. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2002;25(2):209–214. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chao W. Degradation of di-butyl-phthalate by soil bacteria. Chemosphere. 2006;63(8):1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu Y. Biodegradation of dimethyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate and di-n-butyl phthalate by Rhodococcus sp L4 isolated from activated sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;168(2):938–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.02.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan H., Ye C., Yin C. Kinetics of phthalate ester biodegradation by Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1995;14(6):931–938. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin D. Biodegradation of di-n-butyl phthalate by an isolated Gordonia sp. strain QH-11: Genetic identification and degradation kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012;221:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J. Kinetics of biodegradation of di-n-butyl phthalate in continuous culture system. Chemosphere. 1998;37(2):257–264. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(98)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shuler M.L., Kargi F. Prentice Hall ^ eUpper Saddle River; Upper Saddle River: 2002. Bioprocess Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vinay K., Maitra S. Efficient degradation of dibutyl phthalate and utilization of phthalic acid esters (paes) by acinetobacter species isolated from msw (municipal solid waste) Leachate. 2016;18(December (4)):817–830. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eaton R.W., Ribbons D.W. Metabolism of dibutylphthalate and phthalate by Micrococcus sp. strain 12B. J. Bacteriol. 1982;151(1):48–57. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.48-57.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grifoll M., Selifonov S., Chapman P.J. Evidence for a novel pathway in the degradation of fluorene by Pseudomonas sp. strain F274. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994;60(7):2438–2449. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2438-2449.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eaton R.W. Plasmid-encoded phthalate catabolic pathway in Arthrobacter keyseri 12B. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183(12):3689–3703. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3689-3703.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiyohara H., Nagao K. The catabolism of phenanthrene and naphthalene by bacteria. Microbiology. 1978;105(1):69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nomura Y. Genes in PHT plasmid encoding the initial degradation pathway of phthalate in Pseudomonas putida. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1992;74(6):333–344. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engelhardt G., Wallnöfer P. Metabolism of di-and mono-n-butyl phthalate by soil bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1978;35(2):243–246. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.243-246.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi K.Y. Molecular and biochemical analysis of phthalate and terephthalate degradation by Rhodococcus sp. strain DK17. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005;252(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keyser P. Biodegradation of the phthalates and their esters by bacteria. Environ. Health Perspect. 1976;18:159. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7618159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang H.-K., Zylstra G.J. Characterization of the phthalate permease OphD from Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 17616. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181(19):6197–6199. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6197-6199.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Correll C.C. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase: a modular structure for electron transfer from pyridine nucleotides to (2Fe-2S) Science. 1992;258(5088):1604–1611. doi: 10.1126/science.1280857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Batie C.J., LaHaie E., Ballou D. Purification and characterization of phthalate oxygenase and phthalate oxygenase reductase from Pseudomonas cepacia. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262(4):1510–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]