Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine the rate of missed treatments among hemodialysis (HD) patients, and the association between treatment nonadherence and clinical outcomes.

Data source

The data used in this study were based on electronic medical records and Medicare claims.

Study design

This is a retrospective, observational study.

Principal findings

HD patients miss 9.9% of all treatments. Approximately half of the missed treatments are due to observable medical events, predominantly hospitalizations, while half result from nonadherence (“absence”). A single absence is associated with a 1.4-fold greater risk of hospitalization, and a 2.2-fold greater risk of death in the subsequent 30 days.

Conclusion

Treatment nonadherence is common among HD patients and is associated with adverse outcomes. Interventions that improve adherence may improve patient health and reduce costs.

Keywords: Medicare, ambulatory/outpatient care, epidemiology, chronic disease

Introduction

End-stage renal disease (ESRD; also known as kidney failure) occurs when the kidneys can no longer remove enough excess fluid and toxins from the body to sustain life. In the absence of a kidney transplant, patients with ESRD can only survive if they receive dialysis treatments to compensate for their lack of kidney function. In the US, approximately two-thirds of the patients with ESRD are treated with hemodialysis (HD), a therapy in which patients attend three 4-hour treatments per week at a dialysis center where their blood is circulated through a machine that functions as an artificial kidney.

ESRD has become a pressing public health concern throughout the developed world. In the US, for example, there are ~660,000 patients with ESRD, and ~21,000 new patients are diagnosed annually.1 Based on a law passed in 1972, a vast majority (85%) of American ESRD patients, regardless of age, are Medicare beneficiaries. The annual cost of the Medicare ESRD program now exceeds $30 billion, or 7.1% of paid Medicare claims costs for the year, even though ESRD patients comprise only 1.2% of the Medicare population.1 In spite of these expenditures, outcomes for ESRD patients treated with HD are poor. As compared to the general Medicare population, these patients have 4- to 10-fold higher mortality rates, 6-fold higher hospitalization rates, and more than double the likelihood of 30-day readmission.1,2

For decades, the medical and public health communities have sought better understanding of the high clinical and economic burden borne by patients treated with HD. Studies have focused on the high index of concomitant illnesses (eg, diabetes, heart failure), pathophysiological sequelae of ESRD (eg, anemia, metabolic bone disease, high blood pressure), and technological aspects of the delivery of dialysis treatments (eg, how fluid is removed, the access by which blood is taken from and returned to the body). While many of these findings have led to improvements in care and outcomes, the pace and scale of improvement have been suboptimal.

Within the context of the current HD treatment paradigm, treatment adherence remains an area with the potential to yield significant improvements in patient outcomes.3–8 Considering that HD patients rely upon their treatments for essential homeostatic functions, the consequences of forgoing even a single treatment (eg, build-up of fluids and electrolytes, or acidification of the blood) are potentially serious. When considering the possible consequences of missed treatments, it is important to understand that not all absences from the dialysis facility represent nonadherence. HD patients are hospitalized an average of 11.7 days per year1 and miss treatment at their dialysis facility as a result. Because substitute dialysis is almost invariably delivered in the inpatient setting, missed treatments due to hospitalization do not carry with them the same physiological consequences as true instances of dialysis nonadherence. Conversely, because of the prognostic implications for hospitalized dialysis patients, a failure to distinguish between missed treatments due to hospitalization versus missed treatments due to nonadherence may exaggerate the effect of nonadherence on clinical outcomes.

In this retrospective cohort study, treatment attendance data from a large dialysis organization (LDO; comprising 40% of the US dialysis population) were combined with Medicare claims data, enabling accurate delineation of missed treatments due to hospitalization (or other medical procedures) versus nonadherence. Using the same data sources, the implications of treatment nonadherence were then analyzed with respect to key clinical outcomes.

Methods

Data and patient cohort

Data regarding patient demographics, disease history and comorbid conditions, laboratory results, intravenous medications administered at dialysis sessions, and treatment attendance records were abstracted from the electronic medical records (EMRs) of patients at the LDO. Data regarding hospitalizations (dates and causes), emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient procedures were taken from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) Medicare claims dataset. The two datasets were directly linked without the need for probabilistic matching. All data used in the analyses were statistically de-identified in accordance with the privacy rule of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study was conducted with de-identified patient data, it was deemed exempt by an institutional review board (Quorum IRB, Seattle, WA, USA). All study methods complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Analysis

To determine the overall prevalence of missed treatments, and the relative proportion of missed treatments attributable to medical events versus nonadherence, patients who, during the period 01 January–31 December 2012, were at least 18 years of age, enrolled at the LDO and receiving in-center HD, enrolled in Medicare A and B with available claims data, and were not Veteran’s Affairs beneficiaries (contractual stipulation) were considered.

Patients were followed until study end or censoring for death, transfer, transplant, withdrawal from dialysis, renal recovery, modality change, or disenrollment from Medicare A and B. For each missed treatment identified in the LDO’s attendance records, it was determined whether a medical event (hospitalization, ED visit, or outpatient procedure) on the same date could be identified in the Medicare claims data for the corresponding patient. In cases where multiple medical events were identified on the same date, the following hierarchy was applied: hospitalization > ED visit > procedure. The total number of missed treatments per patient was capped at 78 (corresponding to 50% of the scheduled treatments in a year).

To estimate associations between a single absence (missed treatment due to nonadherence) and outcomes, patients who, in addition to the criteria listed above, dialyzed on a Monday/Wednesday/Friday schedule, were enrolled in Medicare parts A and B on the index date, had received dialysis at the LDO for ≥90 days as of index date, and had not missed dialysis or been hospitalized in the 30 days prior to index date were examined.

The index dates considered were a Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (21, 23, and 25 May 2012). On each index date, it was determined whether each patient had attended treatment, had missed treatment for medical reasons, or had missed treatment due to nonadherence. Patients who had missed treatment for medical reasons were not considered further. Patients who missed treatment due to nonadherence (cases) were nearest-neighbor propensity score-matched without replacement to five controls (attended treatment on index date).

Outcomes were considered over the 30 and 180 days subsequent to the index date. Deaths were identified from the LDO’s EMR. Hospitalizations were identified from Medicare Part A claims. ED visits were identified from Medicare Part B (physician/supplier) claims in the USRDS dataset for which place of service was specified as the ED. Results were then pooled across the three index dates. Outcomes were generated by a repeated measures general linear model.

Results

Causes of missed treatments

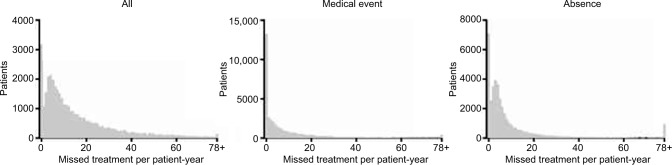

Of 4,656,477 scheduled treatments meeting study criteria in 2012, patients missed a total of 462,028 (9.9%), corresponding to an overall rate of 15.31 missed treatments per patient-year. Only 8.1% of patients had perfect treatment attendance during follow-up (Figure 1). Of all the patients, 44.6% missed treatment at a rate of 13 or more per patient-year, or 10% of the scheduled treatments.

Figure 1.

Distribution of patient counts by missed treatment rate and cause.

Note: The number of patients who missed treatments for any cause (left panel), due to a documented medical event (including hospitalization, emergency department visit, or outpatient procedure; middle panel) or due to absence (right panel) is presented by the rate of missed treatments per patient-year.

Of all the missed treatments in the dataset, 47.1% could be ascribed to a documented medical event (hospitalization, ED visit, or outpatient procedure; Table 1). The vast majority of these (45% of all missed treatments) could be ascribed to a hospitalization. Only 2% of all missed treatments could be attributed to either ED visits or outpatient procedures that were not themselves associated with a hospitalization. Approximately one-third of the patients had no missed treatments associated with a documented medical event during follow-up (Figure 1). However, 23.6% of patients missed treatments due to documented medical events at a rate of 13 or more per patient-year. Hospitalization for diseases of the circulatory system (23.6%), injury and poisoning (18.3%), and diseases of the respiratory system (12.0%) (Table S1) led to the greatest numbers of missed treatments due to hospitalization.

Table 1.

Missed treatments by cause during 2012

| Variables | All | Hospitalization | ED visit | Procedure | Absence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events, n | 462,028 | 208,478 | 8885 | 546 | 244,119 |

| Rate per patient-year | 15.31 | 6.91 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 8.09 |

| % of all missed treatments | 45.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 52.8 |

Notes: Total time at risk: 30,178 patient-years. Total number of missed treatments per patient was capped at 78.

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

While 47.1% of all missed treatments could be linked to a documented medical event, the remainder (52.8%) had no identifiable medical cause (ie, are likely to represent nonadherence) and are referred to throughout as “absences” (Table 1; Figure 1). During follow-up, approximately 18% of patients had no absences, whereas 19% of patients had absences at a rate of 13 or more per patient-year.

Impact of a single absence on clinical outcomes

To determine the association between a single absence and outcomes, patients who, on three discrete calendar dates in 2012, either attended their treatment or were absent were identified. Prior to matching, patients with an absence were, as compared to patients who attended their treatment, younger, more likely to be black and less likely to be white or Asian, slightly newer to dialysis, and more likely to have diabetes. They also had lower albumin, normalized protein catabolic rate (a marker of nutritional adequacy), and Kt/V (a measure of dialysis adequacy), and higher serum phosphate (Table 2). After matching, all characteristics were well balanced between patients who attended versus who were absent from their treatment (Table 3). All subsequent analyses were performed in the matched cohort to promote fair comparisons.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline patient characteristics by attendance status: pre-match

| Variables | Overall, N = 93,389 | Attended, N = 92,107 | Absence, N = 1282 | Standardized difference (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 62.9 ± 14.5 | 62.9 ± 14.5 | 60.5 ± 14.5 | −16.9 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.33 | ||||

| Female | 41,424 (44.4) | 40,838 (44.3) | 586 (45.7) | 2.8 | |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 35,425 (37.9) | 34,982 (38.0) | 443 (34.6) | −7.1 | |

| Black | 36,310 (38.9) | 35,720 (38.8) | 590 (46.0) | 14.7 | |

| Hispanic | 14,843 (15.9) | 14,653 (15.9) | 190 (14.8) | −3.0 | |

| Asian | 3043 (3.3) | 3028 (3.3) | 15 (1.2) | −14.4 | |

| Other/unknown | 3768 (4.0) | 3724 (4.0) | 44 (3.4) | −3.2 | |

| Vascular access, n (%) | 0.05 | ||||

| Arteriovenous fistula | 63,831 (68.3) | 63,000 (68.4) | 831 (64.8) | −7.6 | |

| Arteriovenous graft | 20,999 (22.5) | 20,685 (22.5) | 314 (24.5) | 4.8 | |

| Central venous catheter | 8556 (9.2) | 8419 (9.1) | 137 (10.7) | 5.2 | |

| Other/missing | 3 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Dialysis vintage (months) | 0.006 | ||||

| Median [p25, p75] | 48 [26, 81] | 48 [26, 81] | 45 [24, 76] | −10.5 | |

| Target weight (kg) | 0.34 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 80.7 ± 22.5 | 80.7 ± 22.5 | 81.3 ± 22.2 | 2.7 | |

| Etiology of ESRD, n (%) | 0.12 | ||||

| Diabetes | 41,917 (44.9) | 41,323 (44.9) | 594 (46.3) | 3.0 | |

| Hypertension | 28,576 (30.6) | 28,171 (30.6) | 405 (31.6) | 2.2 | |

| Other | 22,896 (24.5) | 22,613 (24.6) | 283 (22.1) | −5.9 | |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 105 (0.1) | 104 (0.1) | <10 | −1.1 | 0.71 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 63,728 (68.2) | 62,804 (68.2) | 924 (72.1) | 8.5 | 0.003 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 13,507 (14.5) | 13,306 (14.4) | 201 (15.7) | 3.4 | 0.21 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 11,586 (12.4) | 11,438 (12.4) | 148 (11.5) | −2.7 | 0.35 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 968 (1.0) | 956 (1.0) | 12 (0.9) | −1.0 | 0.72 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 7588 (8.1) | 7487 (8.1) | 101 (7.9) | −0.9 | 0.74 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 0.004 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | −8.0 | |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 0.69 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | −1.1 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.31 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.7 ± 2.9 | 8.7 ± 2.9 | 8.6 ± 2.9 | −3.0 | |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 0.73 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 759.9 ± 351.8 | 759.9 ± 351.6 | 763.3 ± 366.2 | 1.0 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.41 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.9 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 1.1 | −2.3 | |

| Serum phosphate (mg/dL) | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.98 ± 1.39 | 4.98 ± 1.39 | 5.11 ± 1.43 | 9.5 | |

| Parathyroid hormone (ng/mL) | 0.23 | ||||

| Median [p25, p75] | 335 [220, 500] | 334 [220, 499] | 338 [227, 522] | 3.9 | |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 0.67 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 31.2 ± 12.3 | 31.2 ± 12.3 | 31.0 ± 12.4 | −1.2 | |

| nPCR (g/kg/day) | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.04 ± 0.28 | 1.04 ± 0.28 | 1.00 ± 0.28 | −14.4 | |

| Kt/V | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.64 ± 0.27 | 1.64 ± 0.27 | 1.61 ± 0.28 | −13.9 |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; K, dialyzer clearance of urea; t, dialysis time; V, volume of distribution of urea; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; p25, 25th percentile; p75, 75th percentile; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline patient characteristics by attendance status: post-match

| Variables | Overall, N = 7692 | Attended, N = 6410 | Absence, N = 1282 | Standardized difference (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.76 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 60.6 ± 14.8 | 60.6 ± 14.8 | 60.5 ± 14.5 | −0.9 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.62 | ||||

| Female | 3564 (46.3) | 2978 (46.5) | 586 (45.7) | −1.5 | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.99 | ||||

| White | 2646 (34.4) | 2203 (34.4) | 443 (34.6) | 0.4 | |

| Black | 3539 (46.0) | 2949 (46.0) | 590 (46.0) | 0.0 | |

| Hispanic | 1151 (15.0) | 961 (15.0) | 190 (14.8) | −0.5 | |

| Asian | 95 (1.2) | 80 (1.2) | 15 (1.2) | −0.7 | |

| Other/unknown | 261 (3.4) | 217 (3.4) | 44 (3.4) | 0.3 | |

| Vascular access, n (%) | 0.72 | ||||

| Arteriovenous fistula | 4914 (63.9) | 4083 (63.7) | 831 (64.8) | 2.3 | |

| Arteriovenous graft | 1919 (24.9) | 1605 (25) | 314 (24.5) | −1.3 | |

| Central venous catheter | 859 (11.2) | 722 (11.3) | 137 (10.7) | −1.8 | |

| Dialysis vintage (months) | 0.97 | ||||

| Median [p25, p75] | 46 [25, 75] | 46 [25, 75] | 45 [24, 76] | −1.1 | |

| Target weight (kg) | 0.24 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 82.0 ± 23.0 | 82.2 ± 23.2 | 81.3 ± 22.2 | −3.6 | |

| Etiology of ESRD, n (%) | 0.99 | ||||

| Diabetes | 3568 (46.4) | 2974 (46.4) | 594 (46.3) | −0.1 | |

| Hypertension | 2425 (31.5) | 2020 (31.5) | 405 (31.6) | 0.2 | |

| Other | 1699 (22.1) | 1416 (22.1) | 283 (22.1) | 0.0 | |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | <10 | <10 | <10 | −1.0 | 0.75 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5588 (72.6) | 4664 (72.8) | 924 (72.1) | −1.5 | 0.61 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 1251 (16.3) | 1050 (16.4) | 201 (15.7) | −1.9 | 0.53 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 921 (12.0) | 773 (12.1) | 148 (11.5) | −1.6 | 0.60 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 80 (1.0) | 68 (1.1) | 12 (0.9) | −1.3 | 0.69 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 615 (8.0) | 514 (8.0) | 101 (7.9) | −0.5 | 0.87 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 0.73 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | −1.1 | |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 0.82 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.84 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.6 ± 3.0 | 8.6 ± 3.0 | 8.6 ± 2.9 | 0.6 | |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 0.85 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 765.1 ± 362.3 | 765.5 ± 361.5 | 763.3 ± 366.2 | −0.6 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.92 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.9 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 1.1 | −0.3 | |

| Serum phosphate (mg/dL) | 0.23 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 3.7 | |

| Parathyroid hormone (ng/mL) | 0.33 | ||||

| Median [p25, p75] | 335 [217, 519] | 334 [214, 518] | 338 [227, 522] | 4.2 | |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 0.76 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 31.1 ± 12.3 | 31.1 ± 12.3 | 31.0 ± 12.4 | −0.9 | |

| nPCR (g/kg/day) | 0.35 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | −2.9 | |

| Kt/V | 0.37 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | −2.7 |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; K, dialyzer clearance of urea; t, dialysis time; V, volume of distribution of urea; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; p25, 25th percentile; p75, 75th percentile; SD, standard deviation.

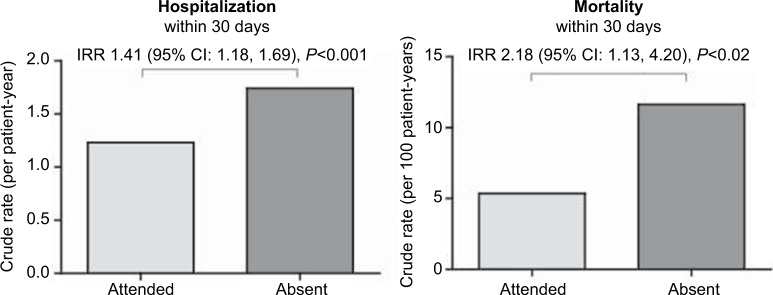

The association of absence versus treatment attendance with risk of hospitalization and mortality was examined. An absence was associated with a 1.41-fold higher risk of hospitalization within 30 days, as compared to patients who attended their treatment (Figure 2). An absence was also associated with a 2.18-fold higher risk of mortality within 30 days (Figure 2). The greater risk of hospitalization and mortality associated with an absence could still be detected when the outcome window was extended to 180 days (Figure S1). The association of a single absence with a variety of other clinical outcomes over the 30- and 180-day outcome periods was also considered (Table S2). An association of an absence with modestly lower hemoglobin levels (a measure of anemia) and modestly higher utilization of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (an anemia medication) was observed. No measurable effects on any other outcomes considered were observed.

Figure 2.

Rates of hospitalization and mortality by attendance status.

Notes: The crude rates (per patient-year) of hospitalization (left panel) and mortality (right panel) within 30 days of the index treatment are presented; the rate for patients who attended the treatment is presented in light gray, whereas the rate for those who were absent from the treatment (ie, did not attend and did not have a documented medical event on the day of the missed treatment) is presented in dark gray. The adjusted IRR (95% CI) referent to patients who did attend the treatment is presented at the top of each panel.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Discussion

Attendance at thrice-weekly dialysis sessions is critical from a physiological perspective. Timely removal of excess fluid avoids strain on the cardiovascular system, and removal of excess electrolytes and toxins is required to prevent a variety of complications. The importance of timely dialysis can be observed in the context of the current standard thrice-weekly dialysis schedule. This schedule (ie, Monday/Wednesday/Friday or Tuesday/Thursday/Saturday) contains one “long break” of 2 days without dialysis between the last dialysis session of 1 week and the first one of the subsequent week. On the day following the long break (ie, Monday or Tuesday), patients are at an elevated risk of death, hospitalization, and cardiovascular events.9,10 It can be inferred that if forgoing dialysis for 2 days over the long break is associated with adverse outcomes, forgoing dialysis for 3–4 days due to an absence would impose an even greater risk to the patient’s health.

This study reports that patients miss an average of ~15 treatments per year, with approximately eight missed treatments per year having no identifiable medical cause, and thus likely representing nonadherence to treatment (ie, absences). Further, it was found that a single absence was associated with a 1.41-fold greater risk of hospitalization in the subsequent 30 days. Because absences were quite common in this patient population, nonadherence is likely to impose a significant burden in terms of patient health and associated cost. Missed treatments may therefore represent an underappreciated point of intervention to improve quality of life of ESRD patients, and to reduce the cost of their care.

Approaches to reducing treatment nonadherence are likely to be complex. Treatment nonadherence may occur in the context of social factors or other contributors such as transportation difficulties, inclement weather, or depression.4 Further, dialysis providers cannot compel patients to attend; indeed, providers are already incentivized (by payment) to encourage treatment attendance. Creative solutions are therefore required; these may include patient education, engagement, treatment of underlying mental health issues, or combinations thereof. Although these interventions are likely to be challenging, nonadherence to HD treatment represents too large a threat to patients’ health to leave unaddressed.

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. The study was limited to Medicare patients by necessity; its generalizability to other patient populations is not known. Likewise, this study examined patients treated with in-center HD; the results do not pertain to other treatment modalities for ESRD. This is a retrospective, observational study; as such, it is may be subject to residual confounding. This study reports statistical associations only; cause and effect were not determined.

Supplementary materials

Rates of hospitalization and death by attendance status (180-day outcome period).

Notes: The crude rates (per patient-year) of hospitalization (left panel) and mortality (right panel) within 180 days of the index treatment are presented; the rate for patients who attended the treatment is presented in light gray, whereas the rate for those who were absent from the treatment (ie, did not attend and did not have a documented medical event on the day of the missed treatment) is presented in dark gray. The adjusted IRR (95% CI) referent to patients who did attend the treatment is presented at the top of each panel.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Table S1.

Hospitalizations that led to a missed treatment by CCS level 1 categories

| Cause of hospitalizationa | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 47,030 | 23.6 |

| Injury and poisoning | 36,390 | 18.3 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 23,874 | 12.0 |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 23,283 | 11.7 |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases, and immunity disorders | 18,697 | 9.4 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 17,525 | 8.8 |

| Symptoms and signs, and ill-defined conditions and factors influencing health status | 5057 | 2.5 |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 4929 | 2.5 |

| Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs | 4877 | 2.4 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 4509 | 2.3 |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 4486 | 2.3 |

| Neoplasms | 3308 | 1.7 |

| Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs | 2295 | 1.2 |

| Mental illness | 2127 | 1.1 |

| Residual codes, unclassified, all E codes [259 and 260] | 857 | 0.4 |

| Congenital anomalies | 125 | 0.1 |

| Complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | <10 | 0.0 |

Table S2.

Overall comparison of short-term (30-day) and long-term (180-day) secondary outcomes by attendance status

| Outcome | Attended, mean (95% CI) | Absence, mean (95% CI) | Difference, mean (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day outcomes | ||||

| Serum potassium | 4.73 (4.72, 4.75) | 4.73 (4.69, 4.77) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | 0.91 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.93 (10.90, 10.96) | 10.75 (10.69, 10.81) | −0.18 (−0.25, −0.12) | <0.001 |

| Ultrafiltration rate | 9.76 (9.59, 9.93) | 9.94 (9.12, 10.75) | 0.18 (−0.65, 1.00) | 0.68 |

| Ultrafiltration volume | 2.67 (2.64, 2.70) | 2.61 (2.52, 2.70) | −0.06 (−0.15, 0.04) | 0.26 |

| Blood pressure | 147.3 (146.8, 147.8) | 147.6 (146.4, 148.8) | 0.3 (−1.0, 1.6) | 0.68 |

| ESA administrations | 7.85 (7.74, 7.96) | 7.68 (7.43, 7.93) | −0.17 (−0.44, 0.10) | 0.22 |

| ESA dosea | 4594 (4494, 4693) | 4775 (4535, 5016) | 181 (−77, 439) | 0.17 |

| ESA utilizationb | 3953 (3859, 4047) | 4060 (3835, 4284) | 107 (−135, 348) | 0.39 |

| 180-Day outcomes | ||||

| Serum potassium | 4.75 (4.74, 4.76) | 4.75 (4.72, 4.77) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.78 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.93 (10.91, 10.96) | 10.85 (10.8, 10.9) | −0.08 (−0.14, −0.03) | 0.003 |

| Ultrafiltration rate | 9.72 (9.62, 9.83) | 10.03 (9.25, 10.81) | 0.31 (−0.48, 1.09) | 0.44 |

| Ultrafiltration volume | 2.66 (2.63, 2.69) | 2.62 (2.54, 2.7) | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.05) | 0.39 |

| Blood pressure | 147.3 (146.8, 147.8) | 147.8 (146.7, 149.0) | 0.6 (−0.7, 1.8) | 0.37 |

| ESA administrations | 45.25 (44.66, 45.83) | 42.39 (41.12, 43.67) | −2.85 (−4.25, −1.46) | <0.001 |

| ESA dosea | 4583 (4495, 4672) | 4862 (4639, 5085) | 278 (39, 518) | 0.02 |

| ESA utilizationb | 4160 (4074, 4246) | 4429 (4212, 4646) | 269 (37, 502) | 0.02 |

Notes:

Among patients receiving ESA.

Among all patients (users and nonusers).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent.

Reference

- 1.Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. [webpage on the Internet] [Accessed November 1, 2016]. Available from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the members of the DaVita Clinical Research (DCR) Healthcare Analytics and Insights team for data preparation and helpful discussions. This research was presented at the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2016 held in Chicago, IL, on 15–20 November 2016, as a poster with interim findings. The abstract was published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Volume 27, Abstract Edition (November 2016). The data reported here were supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Footnotes

Disclosure

KSG, DEC, and SMB are all employees of DCR. DCR played no role in the study design, execution, or interpretation, or in preparation of the manuscript. DCR was provided with a copy of the manuscript to review prior to publication. SMB’s spouse is an employee of AstraZeneca. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System . USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2015. 2015. [Accessed November 1, 2016]. Available from: https://www.usrds.org/2015/view/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz HM, Nuti SV, Downing NS, Normand SL, Wang Y. Mortality, hospitalizations, and expenditures for the Medicare population aged 65 years or older, 1999–2013. JAMA. 2015;314(4):355–365. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer AJ, Hylander B, Sudo H, et al. An international study of patient compliance with hemodialysis. JAMA. 1999;281(13):1211–1213. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.13.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan KE, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Adherence barriers to chronic dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(11):2642–2648. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leggat JE, Jr, Orzol SM, Hulbert-Shearon TE, et al. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(1):139–145. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obialo CI, Hunt WC, Bashir K, Zager PG. Relationship of missed and shortened hemodialysis treatments to hospitalization and mortality: observations from a US dialysis network. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5(4):315–319. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfs071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Rayner HC, et al. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):254–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unruh ML, Evans IV, Fink NE, Powe NR, Meyer KB. Skipped treatments, markers of nutritional nonadherence, and survival among incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(6):1107–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley RN, Gilbertson DT, Murray T, Collins AJ. Long interdialytic interval and mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1099–1107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fotheringham J, Fogarty DG, El Nahas M, Campbell MJ, Farrington K. The mortality and hospitalization rates associated with the long interdialytic gap in thrice-weekly hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2015;88(3):569–575. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Rates of hospitalization and death by attendance status (180-day outcome period).

Notes: The crude rates (per patient-year) of hospitalization (left panel) and mortality (right panel) within 180 days of the index treatment are presented; the rate for patients who attended the treatment is presented in light gray, whereas the rate for those who were absent from the treatment (ie, did not attend and did not have a documented medical event on the day of the missed treatment) is presented in dark gray. The adjusted IRR (95% CI) referent to patients who did attend the treatment is presented at the top of each panel.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Table S1.

Hospitalizations that led to a missed treatment by CCS level 1 categories

| Cause of hospitalizationa | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 47,030 | 23.6 |

| Injury and poisoning | 36,390 | 18.3 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 23,874 | 12.0 |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 23,283 | 11.7 |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases, and immunity disorders | 18,697 | 9.4 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 17,525 | 8.8 |

| Symptoms and signs, and ill-defined conditions and factors influencing health status | 5057 | 2.5 |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 4929 | 2.5 |

| Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs | 4877 | 2.4 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 4509 | 2.3 |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 4486 | 2.3 |

| Neoplasms | 3308 | 1.7 |

| Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs | 2295 | 1.2 |

| Mental illness | 2127 | 1.1 |

| Residual codes, unclassified, all E codes [259 and 260] | 857 | 0.4 |

| Congenital anomalies | 125 | 0.1 |

| Complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | <10 | 0.0 |

Table S2.

Overall comparison of short-term (30-day) and long-term (180-day) secondary outcomes by attendance status

| Outcome | Attended, mean (95% CI) | Absence, mean (95% CI) | Difference, mean (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day outcomes | ||||

| Serum potassium | 4.73 (4.72, 4.75) | 4.73 (4.69, 4.77) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | 0.91 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.93 (10.90, 10.96) | 10.75 (10.69, 10.81) | −0.18 (−0.25, −0.12) | <0.001 |

| Ultrafiltration rate | 9.76 (9.59, 9.93) | 9.94 (9.12, 10.75) | 0.18 (−0.65, 1.00) | 0.68 |

| Ultrafiltration volume | 2.67 (2.64, 2.70) | 2.61 (2.52, 2.70) | −0.06 (−0.15, 0.04) | 0.26 |

| Blood pressure | 147.3 (146.8, 147.8) | 147.6 (146.4, 148.8) | 0.3 (−1.0, 1.6) | 0.68 |

| ESA administrations | 7.85 (7.74, 7.96) | 7.68 (7.43, 7.93) | −0.17 (−0.44, 0.10) | 0.22 |

| ESA dosea | 4594 (4494, 4693) | 4775 (4535, 5016) | 181 (−77, 439) | 0.17 |

| ESA utilizationb | 3953 (3859, 4047) | 4060 (3835, 4284) | 107 (−135, 348) | 0.39 |

| 180-Day outcomes | ||||

| Serum potassium | 4.75 (4.74, 4.76) | 4.75 (4.72, 4.77) | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.78 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.93 (10.91, 10.96) | 10.85 (10.8, 10.9) | −0.08 (−0.14, −0.03) | 0.003 |

| Ultrafiltration rate | 9.72 (9.62, 9.83) | 10.03 (9.25, 10.81) | 0.31 (−0.48, 1.09) | 0.44 |

| Ultrafiltration volume | 2.66 (2.63, 2.69) | 2.62 (2.54, 2.7) | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.05) | 0.39 |

| Blood pressure | 147.3 (146.8, 147.8) | 147.8 (146.7, 149.0) | 0.6 (−0.7, 1.8) | 0.37 |

| ESA administrations | 45.25 (44.66, 45.83) | 42.39 (41.12, 43.67) | −2.85 (−4.25, −1.46) | <0.001 |

| ESA dosea | 4583 (4495, 4672) | 4862 (4639, 5085) | 278 (39, 518) | 0.02 |

| ESA utilizationb | 4160 (4074, 4246) | 4429 (4212, 4646) | 269 (37, 502) | 0.02 |

Notes:

Among patients receiving ESA.

Among all patients (users and nonusers).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent.