Abstract

MIKCc-type MADS-box genes encode transcription factors that control floral organ morphogenesis and flowering time in flowering plants. Here, in order to determine when the subfamilies of MIKCc originated and their early evolutionary trajectory, we sampled and analyzed the genomes and large-scale transcriptomes representing all the orders of gymnosperms and basal angiosperms. Through phylogenetic inference, the MIKCc-type MADS-box genes were subdivided into 14 monophyletic clades. Among them, the gymnosperm orthologs of AGL6, SEP, AP1, GMADS, SOC1, AGL32, AP3/PI, SVP, AGL15, ANR1, and AG were identified. We identified and characterized the origin of a novel subfamily GMADS within gymnosperms but lost orthologs in monocots and Brassicaceae. ABCE model prototype genes were relatively conserved in terms of gene number in gymnosperms, but expanded in angiosperms, whereas SVP, SOC1, and GMADS had dramatic expansions in gymnosperms but conserved in angiosperms. Our results provided the most detailed evolutionary history of all MIKCc gene clades in gymnosperms and angiosperms. We proposed that although the near complete set of MIKCc genes had evolved in gymnosperms, the duplication and expressional transition of ABCE model MIKCc genes in the ancestor of angiosperms triggered the first flower.

Keywords: MADS-box genes, ABCE model, gymnosperms, basal angiosperms, molecular evolution, flowering

Introduction

MADS-box genes encode a family of transcription factors (TFs) that have fundamental roles in controlling the development in plants, animals, and fungi (Becker et al., 2000). Phylogenetic analysis of eukaryotic MADS-box genes identified the following two super clades: type I and type II genes. Type I TFs only contain one MADS domain, whereas type II TFs harbor an additional K-box at the C-terminal. MIKCc and MIKC∗ together constitute the type II MADS-box genes in plants (Becker and Theißen, 2003). The split of MIKCc and MIKC∗ genes happened in the ancestor of all land plants (Gramzow and Theissen, 2010). MIKCc genes are concisely studied in expression patterns or mutant phenotypes and best known for their functions (Becker and Theißen, 2003), especially in flowering plants that work as floral organ identity genes. These floral organ identity MIKCc-type MADS-box genes have been subdivided into the following four classes: A, B, C, and E genes that provide five different homeotic functions, with A specifying sepals, A+B+E for petals, B+C+E for stamens, C+E for carpels, and D (sister of C genes) for ovules (Angenent and Colombo, 1991; Weigel and Meyerowitz, 1994).

A phylogenomic study of 17 plants, including eudicots, monocots, spike moss (Selaginella moellendorffii), and Physcomitrella patens identified 1,295 MADS-box genes, and classified MIKCc genes into the following 14 clades: StMADS11, AGL17, AGL12, TM3, FLC, AGL6, AGL2, SQUA, AG, TM8, OsMADS32, DEF/GLO, GGM13, AGL15 (Gramzow and Theißen, 2013). An early study covering gymnosperms, Gnetum sp., and Cycas sp., revealed that AG, AGL6, AGL12, DEF+GLO, GGM13, STMADS11, and TM3-like genes very likely existed in the ancestor of angiosperms and gymnosperms (Becker and Theißen, 2003). A comprehensive analysis of three conifer genomes suggests 11–14 type II MADS genes in the most recent common ancestor of seed plants (Gramzow et al., 2014). Another study covering 27 flowering plants traced back to 11 seed plant specific MIKCc clades (Gramzow and Theißen, 2015). However, the confidence and resolution on the early evolution of MIKCc genes will be largely restricted and lead to conflict results without a comprehensive analysis of all orders of gymnosperms and basal angiosperms.

The gymnosperms, including conifers, cycads, ginkgo, and gnetophytes, belong to the seed bearing plants that do not produce flowers. Gymnosperm seeds are borne on the scales of cones such as with pine and spruce trees, rather than angiosperm seeds, which are encased in a fruit. Decoding the molecular genetics and evolution of reproductive organ formation is essential, however, gymnosperms usually have very large genomes, thereby hindered the deciphering gymnosperm genomes. Up to date (November 30, 2016), only the genomes of Picea abies (Nystedt et al., 2013) and Ginkgo biloba (Guan et al., 2016) have been reported in gymnosperms. In P. abies, among 278 putative MADS-box genes, only 41 genes were expressed (Nystedt et al., 2013).

Flowering plants are involved in our daily lives including energy, material, food, and culture. In taxonomy, which plant, the amborella or water lily is the most basal angiosperm remains as a great abominable mystery. Thereby the sampling without a water lily genome would probably lead to wrong result when studying the MIKCc genes in these basal angiosperms and even in implicating the number of clades in the ancestor of seed plants. Actually, basal angiosperms constitute about 175 species from the following three orders: Amborellales, Nymphaeales, and Austrobaileyales (Zeng et al., 2014), in which only the genome sequence of Amborella trichopoda was released. Thirty-six Amborella MIKCc MADS-box genes were identified and classified into main clades such as AP1, AGL6, AGL2, AGL9, AP3, PI, AG, STK (Project, 2013), underscoring the importance of Amborella for understanding the evolution of MADS-box genes.

In this study, we relied on the recently released genomes and large-scale of transcriptomes of both gymnosperms and angiosperms (sampling from all orders of gymnosperms and basal angiosperms) to characterize and analyze the MIKCc MADS-box genes. We identified the complete set of MIKCc MADS-box genes from gymnosperms and basal angiosperms. The expression of ginkgo MIKCc MADS-box genes in reproductive organs was also studied. We report the MIKCc MADS-box genes from samples of each order of seed plants, laying the foundation for functional analysis of the early evolution of flower formation and gymnosperm reproductive organ formation.

Materials and Methods

Data Retrieval

The genome and transcriptome data of G. biloba were downloaded from the ginkgo genome sequencing project (gigadb.org/dataset/100209). The available genome of Pinus taeda (Neale et al., 2014) was downloaded from congenie.org. Pinus sylvestris’s genome was downloaded from dendrome.ucdavis.edu/treegenes. We also performed blast search against the 6,337 proteins from Cycadales species and 1,924 proteins from Gnetales species from NCBI’s protein database1. The water lily Nymphaea colorata genome was recently sequenced by our own sequenced genome project and could be found from our database www.angiosperms.org (unpublished). The genome of Amborella was downloaded from www.amborella.org. All the other MADS-box genes from transcriptome sequences were downloaded from OneKP project (Matasci et al., 2014). All four orders of gymnosperms (Pinales, Ginkgoales, Cycadales, Gnetales) and all three orders of basal angiosperms Nymphaeales, Amborellales, Austrobaileyales were covered in this study. The sampled species with abbreviations were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Samples used in this study and the number of MIKCc genes found in each plant.

| Clade | Order | Family | Species | Gene symbol | MIKCc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amborellales | Amborellaceae | Amborella trichopoda | URDJ | 7 | |

| Amborellales | Amborellaceae | Amborella trichopoda∗ | scaffold | 15 | |

| Nymphaeales | Nymphaeaceae | Nymphaea colorata∗ | Nym | 13 | |

| Nymphaeales | Nymphaeaceae | Nymphaea sp. | PZRT | 3 | |

| Nymphaeales | Nymphaeaceae | Nuphar advena | WTKZ | 2 | |

| Austrobaileyales | Austrobaileyaceae | Austrobaileya scandens | FZJL | 10 | |

| Austrobaileyales | Schisanclraceae | Kadsura heterodita | NWMY | 3 | |

| Angiosperms | Austrobaileyales | Schisanclraceae | Illicium parviflorum | ROAP | 5 |

| Austrobaileyales | Schisanclraceae | Illicium floridanum | VZCI | 9 | |

| Ceratophyllales | Ceratophyllaceae | Ceratophyllum demersum | NPND | 4 | |

| Vitales | Vitaceae | Vitis vinifera∗ | VIT | 31 | |

| Brassicales | Brassicaceae | Arabidopsis thaliana∗ | At | 37 | |

| Malpighiales | Salicaceae | Populus trichocarpa∗ | Potri | 56 | |

| Poales | Bromeliaceae | Ananas comosus∗ | Aco | 25 | |

| Poales | Poaceae | Oryza sativa∗ | Loc OS | 32 | |

| Poales | Poaceae | Sorghum bicolor∗ | Sorbic | 30 | |

| Cycadales | Zamiaceae | Encephalartos barteri | GNQG | 3 | |

| Cycadales | Stangeriaceae | Stangeria eriopus | KAWQ | 4 | |

| Cycadales | Zamiaceae | Dioon edule | WLIC | 2 | |

| Cycadales | Cycadaceae | Cycas micholitzii | XZUY | 4 | |

| Ginkgoales | Ginkgoaceae | Ginkgo biloba | SGTW | 10 | |

| Gnetales | Gnetaceae | Gnetum montanum | GTHK | 6 | |

| Gnetales | Welwitschiaceae | Welwitschia mirabilis | TOXE | 3 | |

| Gnetales | Ephedraceae | Ephedra sinica | VDAO | 2 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Pines taeda∗ | PITA | 12 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Pines sylvestris∗ | MA | 5 | |

| Ginkgoales | Ginkgoaceae | Ginkgo biloba∗ | Gb | 11 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Falcatifolinm taxoides | ROWR | 11 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Chamaecyparis lawsoniana | AIGO | 11 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Pseudolarix amabilis | AQFM | 11 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Nothotsuga longibracteata | AREG | 7 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Widdringtonia cedarbergensis AUDE | 8 | ||

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Picea engelmannii | AWQB | 9 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Microstrobos fitzgeraldii | BBDD | 2 | |

| Pinales | Taxaceae | Austrotaxus spicata | BTTS | 6 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Platycladus orientalis | BUWV | 9 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Manoao colensoi | CDFR | 7 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Tetraclinis sp. | CGDN | 6 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Pinus radiata | DZQM | 9 | |

| Pinales | Taxaceae | Torreya taxifolia | EFMS | 10 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Prumnopitys andina | EGLZ | 10 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Pilgerodendron uviferum | ETCJ | 10 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Taxodium distichum | FHST | 12 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Dacrycarpus compactus | FMWZ | 8 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Calocedrus decurrens | FRPM | 10 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Tsuga heterophylla | GAMH | 8 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Cedrus libani | GGEA | 11 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Diselma archeri | GKCZ | 10 | |

| Pinales | Taxaceae | Torreya nucifera | HQOM | 11 | |

| Pinales | Cephalotaxaceae | Amentotaxns argotaenia | IAJW | 4 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Callitris gracilis | IFLI | 4 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Pinus parviflora | IIOL | 19 | |

| Gymnosperms | Pinales | Pinaceae | Pseudotsuga wilsoniana | IOVS | 11 |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Dacrydium balansae | IZGN | 10 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Pinus ponderosa | JBND | 9 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Neocallitropsis pancheri | JDQB | 7 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Phyllocladus hypophyllus | JRNA | 10 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Keteleeria evelyniana | JUWL | 12 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Parasitaxus usla | JZVE | 9 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Sundacarpus amarus | KLGF | 8 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Pines jeffreyi | MFTM | 9 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Microcachrys tetragona | MHGD | 8 | |

| Pinales | Araucariaceae | Agathis robusla | MIXZ | 4 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Cathaya argyrophylla | NPRL | 13 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Metasequoia glyptostroboides NRXL | 16 | ||

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Cunninghamia lanceolata | OUOI | 11 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Papuacedrus papuana | OVIJ | 9 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Halocarpus bidwillii | OWFC | 12 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Falcatifolium taxoides | PLYX | 5 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Saxegothaea conspicua | QCGM | 6 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Sequoiadendron giganteum | QFAE | 4 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Falcatifolium taxoides | QHBI | 3 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Cupressus dupreziana | QNGJ | 8 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Taiwania cryptomerioides | QSNJ | 9 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Callitris macleayana | RMMV | 6 | |

| Pinales | Araucariaceae | Wollemia nobilis | RSCE | 8 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Podocarpus coriaceus | SCEB | 8 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Fokienia hodginsii | UEVI | 10 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Nageia nagi | UUJS | 5 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Retrophyllum minus | VGSX | 10 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Abies lasiocarpa | VSRH | 8 | |

| Pinales | Pinaceae | Larix speciosa | WVWN | 9 | |

| Pinales | Taxaceae | Taxus baccata | WWSS | 4 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Athrotaxis cupressoides | XIRK | 8 | |

| Pinales | Podocarpaceae | Podocarpus rubens | XLGK | 7 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Juniperus scopulorum | XMGP | 5 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Microbiota decussata | XQSG | 15 | |

| Pinales | Sciaclopityaceae | Sciadopitys verticillata | YFZK | 4 | |

| Pinales | Taxaceae | Pseudotaxus chienii | YLPM | 10 | |

| Pinales | Cupressaceae | Austrocedrus chilensis | YYPE | 13 | |

∗Indicates this species has the available genome sequence.

Identification of MADS-Box Genes

For those genome sequences, MADS-box genes were predicted using HMMER software (Finn et al., 2011) with the seeds built based on an alignment of reliable MADS genes from all groups of MADS-domain proteins from the representative species Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, and P. abies. For the transcriptome sequences in OneKP database2, redundant sequences were already removed. MADS-box genes were predicted using BLASTP tool (Altschul et al., 1990) using the functional annotated Arabidopsis orthologs as the seeds against the OneKP database.

Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple sequences were aligned using the accurate alignment software MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013) with default parameters. For the large alignment, the fast and accurate near maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using FastTree software using the JTT+CAT model (Price et al., 2009). In the phylogenetic tree, supporting values below 50 were generally regarded unreliable and hided.

Results

Major Clades of MIKCc MADS-Box Genes in Gymnosperms

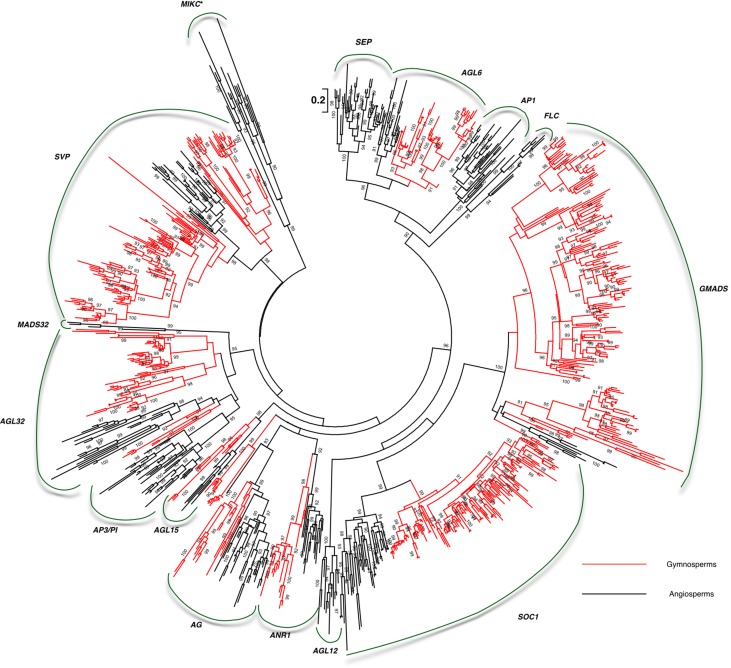

Based on the survey of three gymnosperm (P. taeda, P. sylvestris, G. biloba) and eight angiosperm (Vitis vinifera, A. thaliana, Populus trichocarpa, Ananas comosus, O. sativa, Sorghum bicolor, A. trichopoda, N. colorata) genomes, the following 14 major clades of MIKCc MADS-box genes were characterized: SEP, AGL6, AP1, FLC, GMADS, SOC1, AGL32, AP3/PI, SVP, AGL15, ANR1, AG, AGL12, MADS32 (Figure 1). However, gymnosperm genes were distributed into the following six clades: AGL6, GMADS, AGL32, SVP, AGL15, AG. This is partly because only 12, 5, 11 MIKCc MADS-box genes found in P. taeda, P. sylvestris, G. biloba, respectively (Table 1). These 28 MIKCc MADS-box gymnosperm genes might be useful in studying the early evolution of MIKCc MADS-box genes, however, their limited number may not have a full coverage, and may lead to incomplete evolutionary reconstruction.

FIGURE 1.

Genome-wide analysis of MIKCc MADS-box genes using gymnosperm, basal angiosperm, and crown angiosperm genomes. Sequences from gymnosperms were labeled = with the following colors: red for ginkgo, green for Pinus taeda, and blue for Picea abies.

Refinement of Clade Classification Using Large-Scale Transcriptome Data

Due to the limited genomic sequences of gymnosperms and basal angiosperms, the transcriptome data of often-neglected species covering gymnosperms and basal angiosperms was employed (Table 1) to reveal the evolutionary details. These include 8 basal angiosperms covering all three orders and 71 gymnosperms from all the orders of gymnosperms. We identified 623 MIKCc MADS-box genes from the basal angiosperm and gymnosperm transcriptomes. In the gymnosperm transcriptomes alone 580 MIKCc MADS-box genes were identified, which was 20-fold more than those from three gymnosperm genomes.

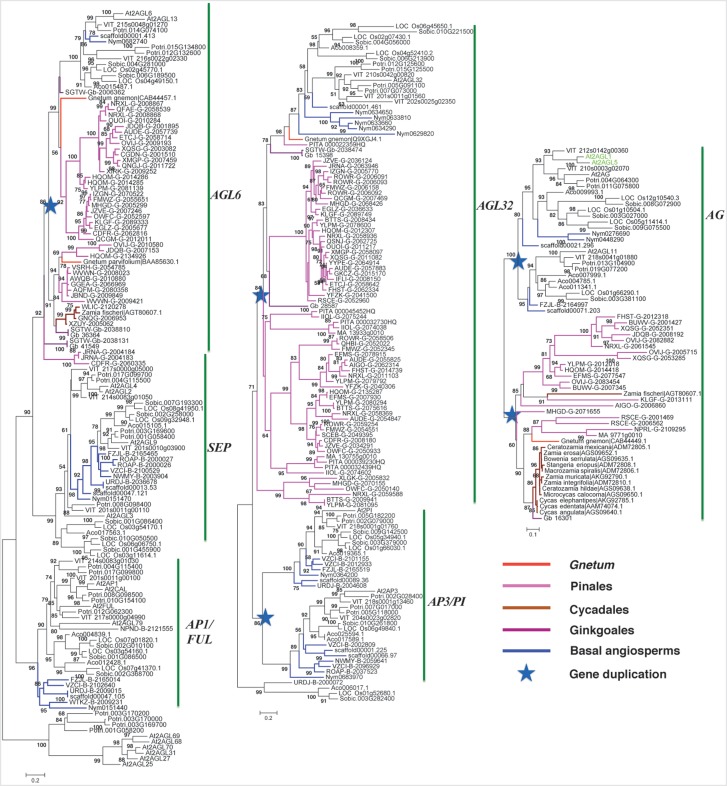

Relying on more gymnosperm and angiosperm sequences, the details of the characterized clades were revealed. The 13rd clade MADS32 with sequences from both basal angiosperm Amborella and three monocots was also detected. No Arabidopsis genes were found in the monophyly (Figure 2). Due to the limited information, we proposed to name this clade of genes as MADS32 based on the name of a rice ortholog OsMADS32. So taken together, the following 14 MIKCc clades were characterized from basal angiosperms and gymnosperms: SVP, MADS32, AP3/PI, AGL32, AGL15, AG, ANR1, AGL12, SOC1, GMADS, FLC, AP1/FUL, AGL6, and SEP (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Large-scale transcriptomes revealed the early evolution of MIKCc MADS-box genes in gymnosperms and basal angiosperms. Branches colored in red indicate gymnosperm sequences.

Since different researchers preferred their own nomenclature standards in classifying the MIKCc MADS-box genes, which often leads to confusion for the public or beginners. We listed the current representative classifications in Table 2. Currently, we have identified all the reported clades and refined several clades based on more representative sequences from all orders of gymnosperms and angiosperms.

Table 2.

Classifications of MIKCc from several reports.

| Shan et al., 2009; Xue et al., 2010 | Gramzow et al., 2014 | Heijmans et al., 2012 | Our report |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP1 | AP1 | ||

| SEP | SQUA, SEP | SEP | |

| AGL6 | AGL6 | AGL6 | |

| FLC | AGL2/AGL6/SQUA/FLC | FLC | FLC |

| AGL12 | AGL12 | AGL12 | AGL12 |

| AG | AGAMOUS | AG, FBP11 | AG |

| S0C1 | TM3 | TM3 | SOC1 |

| SVP | StMADS11 | STMADS11 | SVP |

| ANR1 | AGL17 | AGL17 | ANR1 |

| AGL15 | AGL15, GpMADS4 | AGL15 | AGL15 |

| AP3/PI | AP3/PI | ||

| AGL32 | DEF/GLO/OsMADS32/GGI∖GGM13, GLO, DEF, TM6 | AGL32, MADS32 | |

| TM8 | TM8 | GMADS | |

| Sum = 12 clades | Sum = 10 clades | Sum = 16 clades | Sum = 14 clades |

The representative reports (Shan et al., 2009; Xue et al., 2010; Heijmans et al., 2012; Gramzow et al., 2014) on the classifications and our proposed classification were also shown.

Evolution of A-, B-, C-, E-Function Genes

A-function AP1/FUL genes were only found in angiosperms. In the basal angiosperm stage, AP1/FUL genes retained a single copy in both sequenced Amborella and Nymphaea genomes showing the conserved evolution trajectory (Figure 3). However in monocots, two groups were found in the near-basal monocot pineapple (Ananas comosus) and they diverged into three groups in the crown monocots rice and sorghum. In the eudicots, three groups were clearly identified from basal plant grape to crown plant Arabidopsis, leading to the origin of divergence of AP1 and FUL genes.

FIGURE 3.

Phylogeny of the ABCE model genes in gymnosperms and angiosperms. Branches colored in blue, purple, red, magenta, and coffee-color indicate basal angiosperm, ginkgo, Gnetales, Pinales, and Cycadales sequences, respectively. Arabidopsis sequences were colored in green. The star indicates the gene duplication event.

SEP and AGL6 formed a very close sister group (Figure 3). SEP clade consisted only angiosperm genes, whereas AGL6 was made-up of one group of angiosperm genes, and two groups of gymnosperm genes and suggests SEP and AGL6 diverged within the ancestor of seed plants. Moreover, because basal gymnosperm (ginkgo) genes were found in both groups of AGL6, which suggests a duplication event occurred in the ancestor of gymnosperm and contributed the two groups. In the AGL6 clade, only one group of angiosperm genes was found, whereas three groups of angiosperm genes were found in the SEP clade because of the sampling from basal angiosperms to crown angiosperms. Two groups of SEP genes contained genes from basal angiosperms, monocots and eudicots, but the third group of SEP only contained monocot genes.

AP3 encodes a MADS-box protein that specifies petal and stamen identities, and PI encodes a MADS-box required for the specification of petal and stamen identities. The two groups, AP3 and PI, each consisted of genes from both basal and crown angiosperms (Figure 3), suggesting that they diverged in the ancestor of angiosperms, which were most likely yielded by the angiosperm specific whole genome duplication (WGD).

AGL32 consisted of genes from both gymnosperms and angiosperms (Figure 3), suggesting it originated in the ancestor of seed plants. In gymnosperms, it radiated into three groups, which was not revealed analyzing the three genomes. In angiosperms, AGL32 had two groups in the rosids.

C-function genes were the sister groups of AG in the angiosperms, but they had close orthologs in the gymnosperms (Figure 3). Although this C clade in basal gymnosperm preserved a single copy of the genes, they were duplicated in crown gymnosperms. For example, in species classified in the Pinales three copies were found in Papuacedrus papuana (with gene identity: OVIJ), two copies were identified in Microbiota decussata (XQSG) and Platycladus orientalis (BUWV).

Expansion of SVP, SOC1, and GMADS Genes in Gymnosperms

SVP, SOC1, and GMADS are generally not regarded as core genes involved in the floral organ formation, and only very limited information of these clades are available. However, the genes are essential for other aspects for flowering, such as the agents for flowering time control [SVP (Li et al., 2015); SOC1 (Liu et al., 2016); (Gao et al., 2016)]. Therefore, we set-out to characterize their evolutionary trajectory.

SVP

SVP encodes a MADS-box TF acting as a central regulator of flowering time, and were found in both gymnosperms and angiosperms (Figure 2). In angiosperms, only one monophyletic group was evolved. Full coverage of data showed that SVP retained a single copy in basal angiosperms, however, they duplicated in tree groups of the Poaceae and three groups in rosid. In gymnosperms, two monophylic groups of SVPs were clustered. SVPs were subdivided into two groups in group I, and further divided into seven groups in group II. SVP expanded into more copies in gymnosperms than that in angiosperms. SVP genes were expressed in young shoot, young shoot, leaf, young leaf both in basal angiosperms and gymnosperms as detected in transcriptome sequencing.

SOC1

Although SOC1 was not found in the three genomes of gymnosperms (Figure 1), 141 gymnosperm SOC1 genes were recognized. Phylogenetic analysis showed that 10 groups were identified in the crown Pinales species. Unlike the dramatic expansion of SOC1 in gymnosperms, basal-most angiosperms, Amborella, had only a single copy (Figure 2). However, basal angiosperms Austrobaileya scandens (FZJL) and Illicium floridanum (VZCI), Illicium parviflorum (ROAP) all had duplicated into two subgroups, which nested together, and had a complicated evolutionary history. In crown angiosperms, three subgroups of SOC1 were found in eudicots and two subgroups identified in monocots.

GMADS

We found a highly supported monopyly with supporting values 99. In this monophyly, no Arabidopsis ortholog was detected, which possibly led to its neglect of characterization (Figure 1). This monophyly covers orthologs from gymnosperms, basal angiosperms, and eudicots, showing the consistency of its evolutionary history. Transcriptome data was then employed, which covered gymnosperms and basal angiosperms (Table 1), to reveal the evolutionary details. MIKCc genes were found among the transcriptomes of 8 basal angiosperms and 71 gymnosperms (Table 1). We identified 188 members from the novel subfamily, making it the largest subfamily among all MADS-box gene family (Figure 2). Besides, 10 subgroups were characterized in the crown gymnosperms. Because determining the phylogenetic relationship of this novel clade with other MADS-box genes was difficult and its lack of name, we proposed to name this clade of genes as GMADS for its significant expansion in gymnosperms.

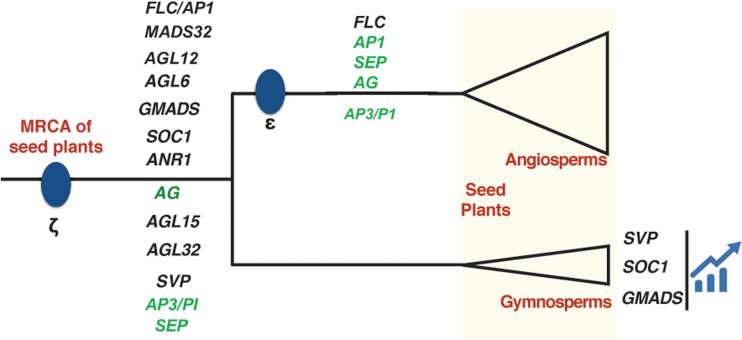

Evolution Atlas of All MIKCc Clades in Seed Plants

Among all the 14 clades, we found 8 clades AGL6, GMADS, SOC1, ANR1, AG, AGL15, AGL32, SVP cover multiple sequences from both gymnosperms and angiosperms (Figure 4), suggesting they originated at least in the most recent common ancestor of seed plants. The following seven clades SEP, FLC, AGL32, AP1, AGL12, AP3/PI, MADS32 were identified only in angiosperms. No clade was specific to gymnosperms (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Evolution of MIKCc clades plotted on a phylogenetic tree of seed plants. Two whole genome duplication (WGD) events ζ and 𝜀 have been marked in blue dots. Three clades expanded significantly in gymnosperms were also presented. The ABCE genes were colored in green.

Expressional Profiling of Ginkgo MIKCc-Type MADS-Box Genes

The gingko genome encoded 11 MIKCc-type MADS-box genes, which was distributed into the following five clades: AGL6, GMADS, AP3/PI, SVP, AG, and covered three major functional clades A/E, B, C. Because the genome has been recently sequenced (Guan et al., 2016), G. biloba serves as a good model for functional and comparative studies. The expression of these 11 genes was quantified using three transcriptomes covering reproductive (male and female) and vegetative (stem and leaf) organs, and all the 11 genes were well-quantified in the transcriptomes. AG (Gb_16301), AGL6 (Gb_41549), AP3/PI (Gb_28587), GMADS (Gb_01884 and Gb_30604) genes were specifically expressed in the reproductive organs with no expression detected in the vegetative organs stem and leaf (Table 3). The four GMADS genes were expressed significantly higher in reproductive organs than in vegetative organs. The two ginkgo SVP orthologs had divergent expression patterns. Gb_05128 was expressed strongly in reproductive organs, whereas Gb_34103 had strong expression in both reproductive and vegetative organs, which suggested their divergent functions.

Table 3.

Expressional profile of 11 ginkgo MIKCc genes.

| MADS-box clade | Gene Id | Female reproductive organ | Male reproductive organ | Leaves and stems of seedlings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | Gb 16301 | 80.83 | 290.18 | 0 |

| AGL6 | Gb 41549 | 23 | 37.79 | 0 |

| AGL6 | Gb 36364 | 28.77 | 115.6 | 0.92 |

| AP3/PI | Gb 28587 | 0 | 0.18 | 0 |

| AP3/PI | Gb 15398 | 32.13 | 4.25 | 16.83 |

| GMADS | Gb 01884 | 25.53 | 87.12 | 0 |

| GMADS | Gb 39109 | 1.29 | 5.02 | 4 |

| GMADS | Gb 19178 | 1.62 | 1.31 | 0.94 |

| GMADS | Gb 30604 | 15.34 | 79.43 | 0 |

| SVP | Gb 05128 | 19.41 | 46.73 | 0.99 |

| SVP | Gb 34103 | 0.63 | 49.01 | 51.48 |

Discussion

The Gymnosperm and Angiosperm MIKCc-Type MADS-Box Genes

Although the MIKCc genes were detected in the crown gymnosperm P. abies and other three Pinales species (Gramzow et al., 2014), genes from a single gymnosperm order could not represent the ancestral state of gymnosperms made up of four orders. High resolution and systematic analysis of basal angiosperm and gymnosperm MIKCc MADS-box genes is lacking due to the lack of omics data in previous studies. In this study, all the orders of gymnosperms and basal angiosperms were sampled, to show the high resolution of early evolution of MIKCc-type MADS-box genes. Our preliminary study using three gymnosperm genomes identified the presence of gymnosperm orthologs in clades AGL6, GMADS, AGL32, AP3/PI, SVP, AGL15, AG. In addition, large-scale transcriptome data revealed gymnosperm orthologs from SEP-AGL6-AP1 group, SOC1, ANR1, AGL12. OsMADS32 clade was reported to be monocot specific (Sang et al., 2012), however, our transcriptome analysis revealed an ortholog from Amborella, which was not found in Amborella genome, supporting the high resolution of our transcriptome sampling. The GpMADS4-like gene clade was thought to be gymnosperm specific (Gramzow et al., 2014), however, it is part of AGL15 in our classification with supporting value 98 in the tree, suggesting the accuracy of our phylogeny.

Gymnosperms often have very large genomes, however polyploidy, usually leading to rapid increase in genome size, is rare among in this group (Gramzow et al., 2014). Only 28 MIKCc MADS-box genes were found in genome sequenced P. taeda, P. sylvestris, G. biloba, collectively. In contrast, 38 genes were found in O. sativa (Arora et al., 2007), 37 in A. thaliana (Becker and Theißen, 2003), and 38 in Vitis vinifera (Díaz-Riquelme et al., 2009), which are significantly standing out compared to those very large gymnosperm genomes. In basal angiosperms, 15 and 13 MIKCc MADS-box genes were detected in Amborella and water lily N. colorata, respectively. All these lines of evidences suggest that WGD contribute greatly to its expansion in crown angiosperms.

Specifically, SOC1, SVP, GMADS clades expanded greatly in gymnosperms and no functional study has been reported in gymnosperms. GMADS might control specific and unknown roles in gymnosperm reproductive organ development based on their expressional analysis in this study. Limited expression in vegetative tissues such as leaf and stem of GMADS and SVP genes were also reported in this study and previous report (Gramzow et al., 2014). The SOC1 genes (or TM3-like) were also reported to have expression in both vegetative and reproductive organs (Gramzow et al., 2014). Considering their vital roles in regulating flowering time in angiosperms, we propose that among their diverse roles that triggering the reproductive organ development by GMADS and SVP genes in gymnosperms be included. In summary, the near complete set of MIKCc type MADS-box genes in gymnosperms suggests the genetic material was the progenitor of the first flower.

The ABCE Model Prototype Genes in Gymnosperms

After analyzing the ABC model genes in P. abies, A/G/E, B, C/D gene ancestors were present (Project, 2013), although only C-function gene was confirmed in the MRCA of seed plants reported. In basal angiosperms, Eschscholzia californica, SEP may have the same functions like AP1 of A-function genes (Zahn et al., 2010). The A-class and E-class genes had two groups of orthologs in gymnosperms. So, we hypothesized that gymnosperm AGL6 orthologs may have functions in reproductive organ formation. Our hypothesis is supported by expressional analysis of a ginkgo AGL6 ortholog Gb_36364, which had very high expression in both male and female reproductive organs. We also hypothesized that the two diverged gymnosperm AGL6 groups will have different functions, similar to the functional divergence of A-function and E-function genes, which needs future functional analysis.

For AP3/PI genes controlling the B-functions, and AG genes controlling the C- and D-functions, gymnosperm ancestors were traced back to as early as the emergence of ginkgo. No orthologs were identified in the Cycadales, another gymnosperm early branch. These genes were specifically expressed in reproductive organs and not detected in the transcriptome. A high quality genome from Cycadales species will be highly favored. In angiosperms, the heterodimerization of AP3 and PI proteins is necessary for B-function (Project, 2013). We have detected the gene duplication of AGL32 orthologs in gymnosperms, and the duplicates only form homodimers in Gnetum and Picea (Project, 2013) suggesting that the protein-protein interaction form is a crucial step in the origin of B-function, but not gene duplication for angiosperms.

Conclusion

In this report, we sampled and analyzed species from all the orders of gymnosperms and the less-visited basal angiosperms including both newly released genomes and high quality large-scale transcriptomes. The major MIKCc-type MADS-box genes were characterized and we identified a new clade GMADS. The ABCE model prototype genes were relatively conserved in terms of gene number in gymnosperms, but expanded in angiosperms. In contrast, SVP, SOC1, and GMADS have dramatic expansion in gymnosperms, but retained conserved in angiosperms. The expression atlas of all MIKCc genes in various organs from ginkgo was measured for the first time in this study. Our results provided strong evidence for the early evolution of MIKCc MADS-box genes and high resolution evolution trajectory, which will largely enhance our understanding of this key transcription family and shed light on decoding its functional correlation to reproductive organ formation in gymnosperms and angiosperms. This study also illustrated the near complete set of MIKCc genes in gymnosperms and suggest that genome duplication, together with expressional transition of MIKCc genes in the ancestor of flowering plants are the major contribution to the first flower.

Author Contributions

LZ designed the research. FC and LZ collected and analyzed the data. FC, XZ, XL, and LZ wrote, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502437), Fujian-Taiwan Joint Innovative Center for Germplasm Resources and Cultivation of Crop [Fujian 2011 Program (2015)75], and a start-up fund from Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University to LZ.

Footnotes

References

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angenent G. C., Colombo L. (1991). Molecualr control of ovule developemnt. Trends Plant Sci. 47 362–369. [Google Scholar]

- Arora R., Agarwal P., Ray S., Singh A. K., Singh V. P., Tyagi A. K., et al. (2007). MADS-box gene family in rice: genome-wide identification, organization and expression profiling during reproductive development and stress. BMC Genomics 8:242 10.1186/1471-2164-8-242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A., Theißen G. (2003). The major clades of MADS-box genes and their role in the development and evolution of flowering plants. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29 464–489. 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00207-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A., Winter K. U., Meyer B., Saedler H., Theißen G. (2000). MADS-box gene diversity in seed plants 300 million years ago. Mol. Bio. Evol. 17 1425–1434. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Riquelme J., Lijavetzky D., Martínez-Zapater J. M., Carmona M. J. (2009). Genome-wide analysis of MIKCC-type MADS box genes in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 149 354–369. 10.1104/pp.108.131052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Clements J., Eddy S. R. (2011). HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 W29–W37. 10.1093/nar/gkr367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Walworth A. E., Mackie C., Song G. (2016). Overexpression of blueberry FLOWERING LOCUS T is associated with changes in the expression of phytohormone-related genes in blueberry plants. Hort. Res. 3:16053 10.1038/hortres.2016.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow L., Theissen G. (2010). A hitchhiker’s guide to the MADS world of plants. Genome Biol. 11:214 10.1186/gb-2010-11-6-214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow L., Theißen G. (2013). Phylogenomics of MADS-box genes in plants — two opposing life styles in one gene family. Biology 2 1150–1164. 10.3390/biology2031150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow L., Theißen G. (2015). Phylogenomics reveals surprising sets of essential and dispensable clades of MIKCc-group MADS-box genes in flowering plants. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 324 353–362. 10.1002/jez.b.22598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow L., Weilandt L., Theißen G. (2014). MADS goes genomic in conifers: towards determining the ancestral set of MADS-box genes in seed plants. Ann. Bot. 114 1407–1429. 10.1093/aob/mcu066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan R., Zhao Y., Zhang H., Fan G., Liu X., Zhou W., et al. (2016). Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba. Gigascience 5 49 10.1186/s13742-016-0154-1PMID:27871309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans K., Morel P., Vandenbussche M. (2012). MADS-box genes and floral development: the dark side in Posidonia oceanica cadmium induces changes in DNA. J. Exp. Bot. 63 5397–5404. 10.1093/jxb/ers233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Chen C., Gao L., Yang S., Nguyen V., Shi X., et al. (2015). The Arabidopsis SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodeler BRAHMA regulates polycomb function during vegetative development and directly activates the flowering repressor gene SVP. PLoS Genet. 11:e1004944 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-R., Pan T., Liang W.-Q., Gao L., Wang X.-J., Li H.-Q., et al. (2016). Overexpression of an orchid (Dendrobium nobile) SOC1/TM3-like ortholog, DnAGL19, in Arabidopsis regulates HOS1-FT expression. Front. Plant Sci. 7:99 10.3389/fpls.2016.00099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matasci N., Hung L., Yan Z., Carpenter E. J., Wickett N. J., Mirarab S., et al. (2014). Data access for the 1,000 Plants (1KP) project. Gigascience 3:17 10.1186/2047-217X-3-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale D. B., Wegrzyn J. L., Stevens K. A., Zimin A. V., Puiu D., Crepeau M. W., et al. (2014). Decoding the massive genome of loblolly pine using haploid DNA and novel assembly strategies. Genome Biol. 15:R59 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt B., Street N. R., Wetterbom A. (2013). The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. Nature 497 579–584. 10.1038/nature12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. N., Dehal P. S., Arkin A. P. (2009). FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 1641–1650. 10.1093/molbev/msp077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project A. G. (2013). The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science 342:1241089 10.1126/science.1241089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang X., Li Y., Luo Z., Ren D., Fang L., Wang N., et al. (2012). CHIMERIC FLORAL ORGANS1, encoding a monocot-specific MADS box protein, regulates floral organ identity in rice. Plant Physiol. 160 788–807. 10.1104/pp.112.200980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan H., Zahn L., Guindon S., Wall P. K., Kong H., Ma H., et al. (2009). Evolution of plant MADS box transcription factors: evidence for shifts in selection associated with early angiosperm diversification and concerted gene duplications. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 2229–2244. 10.1093/molbev/msp129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D., Meyerowitz E. M. (1994). The ABCs of floral homeotic genes. Cell 78 203–209. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90291-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue H., Xu G., Guo C., Shan H., Kong H. (2010). Comparative evolutionary analysis of MADS-box genes in Arabidopsis thaliana and A. lyrata. Biodivers. Sci. 18 109–119. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03164.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn L. M., Ma X., Altman N. S., Zhang Q., Wall P. K., Tian D., et al. (2010). Comparative transcriptomics among floral organs of the basal eudicot Eschscholzia californica as reference for floral evolutionary developmental studies. Genome Biol. 11:R101 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Zhang Q., Sun R., Kong H., Zhang N., Ma H. (2014). Resolution of deep angiosperm phylogeny using conserved nuclear genes and estimates of early divergence times. Nat. Commun. 5 4956 10.1038/ncomms5956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]