Abstract

Artificial photosynthesis shows a promising potential for sustainable supply of nutritional ingredients. While most studies focus on the assembly of the light-sensitive chromophores to 1-D architectures in an artificial photosynthesis system, other supramolecular morphologies, especially bioinspired ones, which may have more efficient light-harvesting properties, have been far less studied. Here, MCpP-FF, a bioinspired building block fabricated by conjugating porphyrin and diphenylalanine, was designed to self-assemble into nanofibers-based multiporous microspheres. The highly organized aromatic moieties result in extensive excitation red-shifts and notable electron transfer, thus leading to a remarkable attenuated fluorescence decay and broad-spectrum light sensitivity of the microspheres. Moreover, the enhanced photoelectron production and transfer capability of the microspheres are demonstrated, making them ideal candidates for sunlight-sensitive antennas in artificial photosynthesis. These properties induce a high turnover frequency of NADH, which can be used to produce bioproducts in biocatalytic reactions. In addition, the direct electron transfer makes external mediators unnecessary, and the insolubility of the microspheres in water allows their easy retrieval for sustainable applications. Our findings demonstrate an alternative to design new platforms for artificial photosynthesis, as well as a new type of bioinspired, supramolecular multiporous materials.

Introduction

Artificial photosynthesis has emerged as a promising approach to use inexhaustible sunlight energy for a sustainable supply of bioactive materials.1 The essential step in this concept is assembly of the light-sensitive antennas into long-distance, orderly organizations for photoelectron transportation.2,3 An extensively used strategy is to imitate natural photosynthesis configurations, i.e., assemble the antennas to 1-D morphologies with external templates.3 Several kinds of materials have been examined as templates, including carbon nanotubes,4 nickel nanowires,5 silicon nanowires,6,7 and indium oxide nanowires.8 However, complicated preparation technologies and limited eco-friendliness hamper the utilization of these inorganic materials.9,10 In contrast, bioinspired organic materials, especially the short peptide self-assemblies, show tremendous potential as frameworks due to their intrinsic advantages of ease of preparation and modification, eco-friendliness, innate biocompatibility, and diversity of morphologies.2,11–16

Diphenylalanine (FF) self-assembling nanostructures show intriguing physicochemical features, including optical, electric, electrochemical, and mechanical properties,14–20 making them ideal bioinspired template candidates for assembling light-sensitive chromophores.2,21 Especially, their abundant and orderly aromatic interactions can facilitate the photoelectrons to transfer in a simpler manner,22 resulting in remarkable photodriven performances of the FF self-assembly chromophore systems.21,23–26 However, in spite of this pronounced progress, it should be noted that the introduction of external templates mostly results in flawed organizations, which can limit their efficiency,27 and the assemblies are usually well dispersed in aqueous solutions, thus contaminating the products and causing waste.28 Also, in many cases external metal-based mediators are needed for photoelectron transfer, thus complicating the configuration of the photosynthesis systems.24 In addition, most studies focus on 1-D organizations, yet other supramolecular morphologies of the chromophores may behave more efficiently in artificial photosynthesis.26,29–31

Here, to realize the high-order organization of light-sensitive chromophores for artificial photosynthesis, we covalently integrated 5-mono(4-carboxyphenyl)-10,15,20-triphenyl porphine (MCpP) and FF dipeptide and assembled the hybrid building blocks into nanofibers, which then readily aggregated into multiporous microspheres through solvent evaporation. The extensive π−π interactions remarkably promoted the excitation wavelength red-shift and the photoelectron transfer, thus leading to a broad-spectrum light sensitivity and electron-transmitting capability of the microspheres. Our assays illustrate that the multiporous microspheres can be used as effective sunlight-sensitive antennas for artificial photosynthesis.

Experimental Section

Materials

5-Mono(4-carboxyphenyl)-10,15,20-triphenyl porphine (MCpP) was purchased from Frontier Scientific (Logan, U.S.A.), Fmoc-L-Phe-OH from GL Biochem (Shanghai, China), O-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and N-hydroxybenzotriazole anhydrous (HOBt) from Chem-Impex International (Wood Dale, IL, U.S.A.), N,N′-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), triisopropylsilane (TIS), hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate (Ru(bpy)3Cl2·6H2O), L-glutamic dehydrogenase from bovine liver (GDH) and α-ketoglutaric acid from Sigma-Aldrich (Rehovot, Israel), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) from Aladdin (Shanghai, China), triethanolamine (TEOA) from Sinopharm (Shanghai, China), Fmoc-L-Phe-Wang resin from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), dichloromethane (DCM), and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) of peptide synthesis purity grade from Bio-Lab (Jerusalem, Israel). All materials were used as received without further purification. Water used was processed by a Millipore purification system (Darmstadt, Germany) with a minimum resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm.

Peptide Synthesis

The hybrid peptide (MCpP-FF) was synthesized on a CEM Liberty 1 microwave peptide synthesizer (Matthews, NC, U.S.A) using the standard Fmoc solid-phase synthesis strategy. After deprotection of the Wang resin with 20% piperidine and 0.1 M HOBt in DMF solution, Fmoc-L-Phe-OH was introduced, followed by introducing another Fmoc-L-Phe-OH and MCpP. The carboxylic groups were activated by treatment with HBTU/HOBt/DIEA, transforming the carboxylic acids into activated esters to react with the deprotected α-amine groups. After synthesis, cleavage from the resin was performed using a mixture of TFA, TIS, and H2O at a ratio of 95:2.5:2.5. The cleavage mixture and subsequent DCM washing solution were then purged with nitrogen.

The obtained concentrated solution was added to water, lyophilized, and then subjected to reverse-phase HPLC and mass spectrometry for analysis, showing that the product purity was >95% (Figures S1 and S2).

Microspheres Preparation

The lyophilized compound was first dissolved in HFIP to prepare stock solutions at a concentration of 100.0 mg mL−1. Then, 50 μL of a fresh HFIP stock solution were mixed with 950 μL of toluene to form 1 mL of a 5.0 mg mL−1 sample solution. HFIP was added to avoid preorganization of the solutes. Then, 20 μL of the solution were dropped onto the substrate, such as a glass slide, and the microspheres were formed as toluene evaporated.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The microspheres-coated glass slide was sputtered with Cr and observed under a JSM-6700 field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 10 kV.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

A total of 10 μL of sample solution were placed onto a 400-mesh copper grid covered with a carbon stabilized film (SPI, West Chester, PA, U.S.A.) and allowed to dry. Afterward, 10 μL of 2.0 wt % uranyl acetate solution was dropped onto the grid and allowed to stain for 2 min before blotting of excess fluid. TEM micrographs were recorded under a Tecnai G2 electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, U.S.A.) operated at 120 kV.

Fluorescent Lifetime Microscopy (FLIM) and Photostability

The fluorescence lifetime images were acquired using a LSM 7 MP 2-photon microscope (Carl Zeiss, Weimar, Germany) coupled to the Becker and Hickl (BH) simple-Tau-152 system. Chameleon Ti:sapphire laser system with an 80 MHz repetition rate was used to excite the sample at a wavelength of 1000 nm. Images were acquired through a Zeiss 20 × 1 NA water-immersion objective. A Zeiss dichroic mirror (LP 760) was used to separate the excitation and the emission light. Emission light between 625 and 760 nm was collected via a hybrid GaAsP detector (HPM-100-40, BH, Berlin, Germany). The image acquisition time was 150−180 s to collect a sufficient number of photons.

For the photostability measurements, 50 images were collected for 23 min every 25 s. Images were analyzed using the SPCImage software (BH).

Confocal Microscopy

The microspheres-coated glass slide was visualized using an LSM 510 META confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Weimar, Germany). The MCpP-FF toluene solution covered with cover glass and sealed with inert oil was examined as a control.

Photocurrent Measurements

The microspheres-coated indium tin oxide (ITO) glass slide was incubated in phosphate buffer (100.0 mM, pH 6.0) containing 15% (w/v) TEOA as an electron donor and was periodically illuminated with visible light from a 350 W Xe lamp. The photocurrent was measured using an electrochemical workstation under a working voltage of 1.2 V. The MCpP and FF crystals were used as controls.

Cyclic Voltammogram (CV)

The microspheres-coated glassy carbon electrode was placed in an electrolytic cell containing 1.0 mg mL−1 Ru(bpy)3Cl2. A three-electrode system was used to obtain the cyclic voltammogram: the microspheres-modified glassy carbon (working electrode), Ag/AgCl (reference electrode), and a platinum wire (counter electrode). The cyclic voltammetry curves of Ru(bpy)3Cl2 were obtained using a 100.0 mV s−1 scanning rate and constant illumination with visible light from a Xe lamp. The MCpP and FF crystals were used as controls.

Visible Light-Driven NADH Regeneration

Photochemical regeneration of NADH was performed in a quartz reactor at room temperature. The 1.0 mM NAD+ was dissolved in phosphate buffer (100.0 mM, pH 6.0) containing 15% (w/v) TEOA. Then the Pt NP-sputtered microspheres coated glass slide (MCpP-FF/Pt system) was dispersed in the reaction solution and exposed to visible light from a Xe lamp. The concentration of regenerated NADH was calculated based on the absorbance at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan).

Photoenzymatic Synthesis of L-Glu

Photoenzymatic synthesis of L-Glu using Pt NP-sputtered microspheres coated glass slide (MCpP-FF/Pt system) was conducted in a quartz cuvette containing 1.0 mM NAD+, 5.0 mM α-ketoglutarate, 100.0 mM ammonium sulfate, 50 U GDH, and 15% TEOA (w/v) in phosphate buffer (100.0 mM, pH 6.0) under visible light illumination. The concentration of L-Glu was calculated based on the increase in the absorbance at 214 nm using a spectrophotometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). For the sustainability study, the MCpP-FF/Pt system was taken out from the solution, rinsed clean with water, and then immersed in another reaction cell.

Results and Discussion

Morphology Characterization of Multiporous Microspheres

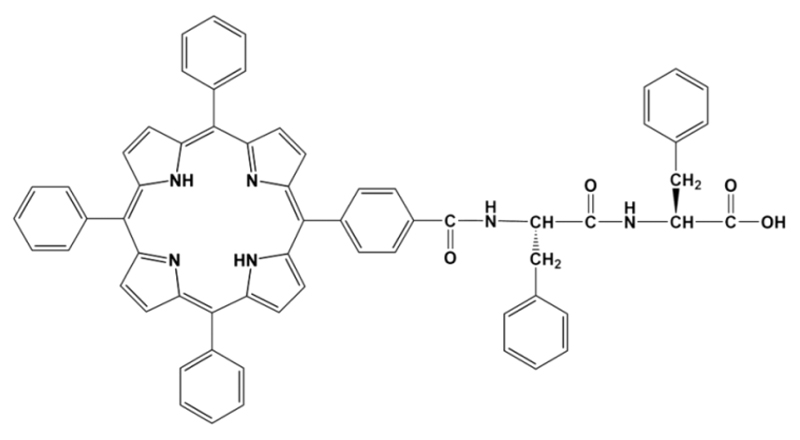

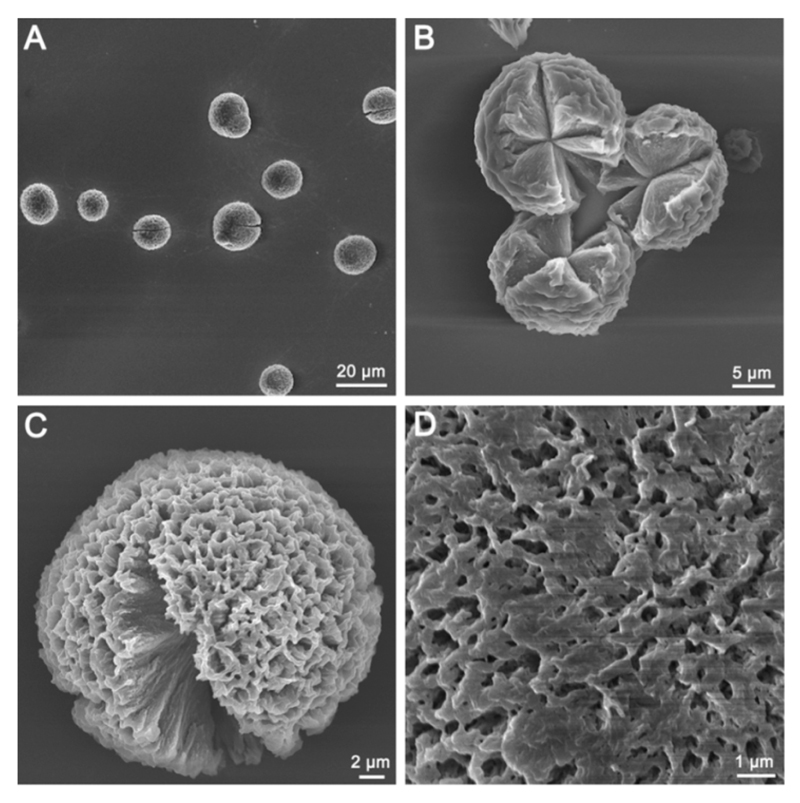

Briefly, MCpP was covalently linked to the N-terminus of the FF dipeptide by Fmoc peptide synthesis strategy, to produce a new compound, designated MCpP-FF (Chart 1). When diluting a hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) stock solution of MCpP-FF with toluene, a green-color solution was obtained (5.0 mg mL−1 in Figure S3). After depositing this toluene solution onto a glass slide and leaving the solvent to dry, spherical microparticles with a diameter of 18.2 ± 6.5 μm were formed (Figure 1A, Figure S4A). Notably, the microspheres could be split, with a morphology resembling blooming flowers and showing the close-grained inside (Figure 1B). Intriguingly, the microsphere surfaces were very rough (Figure 1C) and distributed with micropores (Figure 1D). These characteristics demonstrate that the formed microspheres have a large specific surface area. Furthermore, the microspheres could be formed on other substrates, including hydrophilic (mica) and hydrophobic (siliconized glass) surfaces, and could be kept intact even after immersion in water or liquid nitrogen for 2 h (Figure S5), illustrating the high stability of the microspheres. As controls, MCpP and FF were crystallized in toluene, resulting in plate-like crystals rather than multiporous assemblies (Figure S6).32 It should be noted that the dimensions of the microspheres, including size and specific surface area, can be easily tuned by controlling the solvent evaporation speed through modulation of the temperature and vacuum.

Chart 1. Molecular Structure of MCpP-FFa.

aThe designed molecule is composed of an FF dipeptide sequence conjugated with a 5-mono(4-carboxyphenyl)-10,15,20-triphenyl porphine (MCpP) at the N terminus.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the multiporous microspheres formed by MCpP-FF at 5.0 mg mL−1 on a glass slide after toluene evaporation. From (A) to (D) the magnification increases successively, as noted.

Molecular Mechanism underlying Microsphere Formation

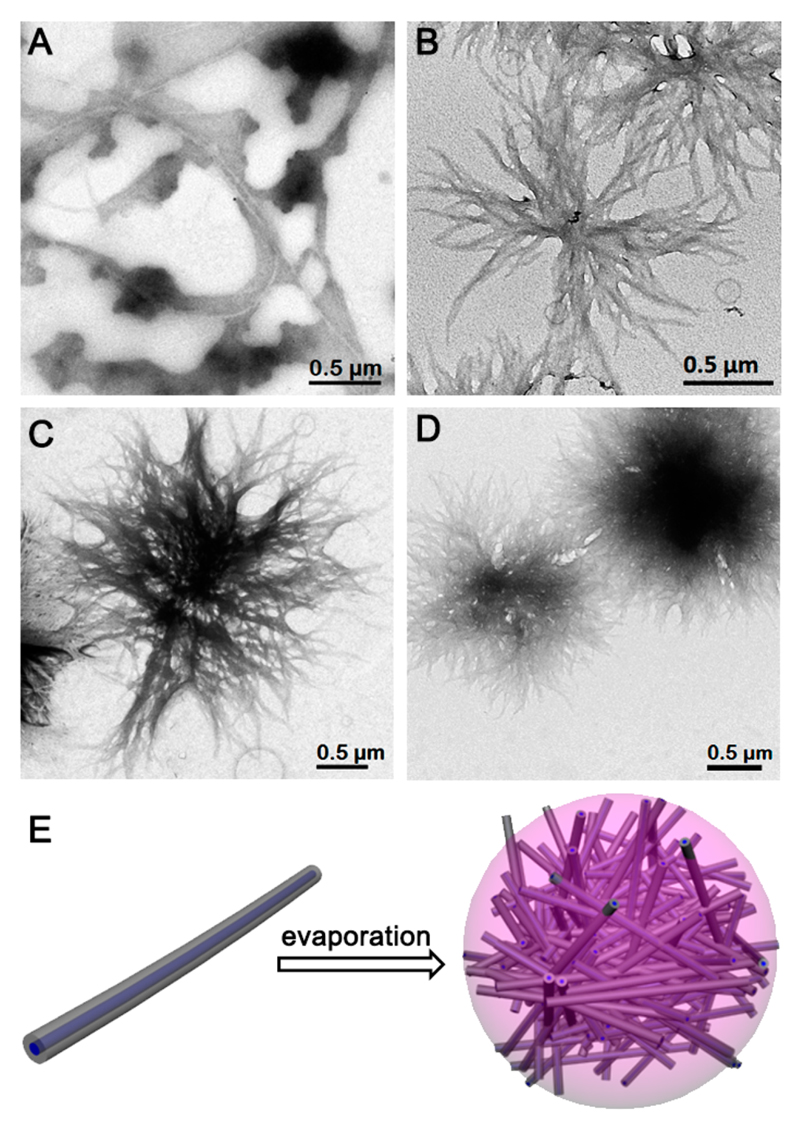

To study the formation mechanism of the multiporous microspheres, a series of solutions with different solute concentrations were prepared (Figure S3). The solution color changed from green to pink as the MCpP-FF content decreased, due to the gradual deprotonation of the pyrrole nitrogen as the proportion of acidic HFIP decreased.33 By dropping the sample solution onto a carbon-coated copper grid following evaporation, TEM characterizations indicated that, at lower concentration (0.05 mg mL−1), MCpP-FF formed thinner nanofibers (Figure 2A), with a width of 19.3 ± 7.7 nm (Figure S4B). As the concentration increased to 0.5 mg mL−1, the nanofibers intertwined to form dendric aggregates (Figure 2B). When the concentration was up to 2.5 mg mL−1, increasing amounts of nanofibers participated in the assembly during solvent evaporation, leading to the branched aggregations growing larger and denser (Figure 2C), and finally evolving to multiporous microspheres when the concentration reached 5.0 mg mL−1 (Figure 2D). The fact that the microspheres were assembled by nanofibers was confirmed by SEM, showing thin nanofibers distributed around the microspheres (Figure S7). Specifically, the interweaved nanofibers connected the supramolecular structures with each other to form a firm layer, resulting in tight attachment of the microspheres to the substrate.

Figure 2.

TEM images representing the self-assembly evolution versus concentration of MCpP-FF during solvent evaporation: (A) nanofibers at 0.05 mg mL−1; (B) dendric aggregations at 0.5 mg mL−1; (C) branched spherical aggregations at 2.5 mg mL−1; and (D) multiporous microspheres at 5.0 mg mL−1. (E) Schematic aggregation of nanofibers to multiporous microspheres during toluene evaporation.

Based on its molecular structure (Chart 1), the MCpP-FF molecule can be considered as a traditional surfactant, with the C-terminal carboxylic group as the hydrophilic head and the MCpP and FF backbone as the hydrophobic tail.29 Therefore, it is assumed that similar to common amyloid-like peptide building blocks, MCpP-FF monomers first self-assembled to β-sheet structures, which then twisted to form nanofibers (Figure S8).27 XRD characterization further confirmed this hypothesis, showing a peak of 5.8 Å corresponding to the distance between adjacent strands in a sheet and a peak of 11.3 Å assigned to the distance between laterally adjacent sheets (Figure S8). The relatively higher values compared to those of common amyloid peptides (4.7 and 9.9 Å, respectively)27 probably result from the large steric volume of the porphyrin moiety. Considering the apolar nature of toluene, during self-assembly the solvophobic carboxylic groups will be entrapped inside while the solvophilic hydrophobic tails will be dispersed at the interface to form core−shell nanofibers (Figure S8), driven by the hydrogen bonding interactions between FF backbones, aromatic interactions, and hydrophobic interactions between aromatic moieties (Figure 2E, left panel).31 As the toluene evaporated, the hydrophobic nanofibers intertwined with each other to form the multiporous microspheres, to minimize the contact area with the environment (Figure 2E, right panel). The internanofiber interactions are weaker than the intra-nanofiber ones due to the lack of hydrogen bonding and less-ordered organizations of the aromatic moieties, resulting in the ability of the microspheres to split. While diluting the HFIP stock solution with water, the solvophobic and solvophilic sections were reversed. According to the definition of the molecular packing parameter (p = ao/ae, where ao is the cross-sectional area of the tail and ae is the equilibrium area occupied by each molecule at the curved interface of the aggregates), increasing the p value can induce the self-assembly to transform from cylindrical morphologies to bilayer structures.34 Therefore, the MCpP-FF molecules self-assembled to bilayer, hollow nanovesicles rather than nanofibers in aqueous solution (Figure S9), due to the much larger ao of MCpP compared to the C-terminal carboxylic group. In particular, the direct formation from monomers to bilayers resulted in the smooth surfaces of the nanovesicles, thus significantly decreasing the specific surface area.

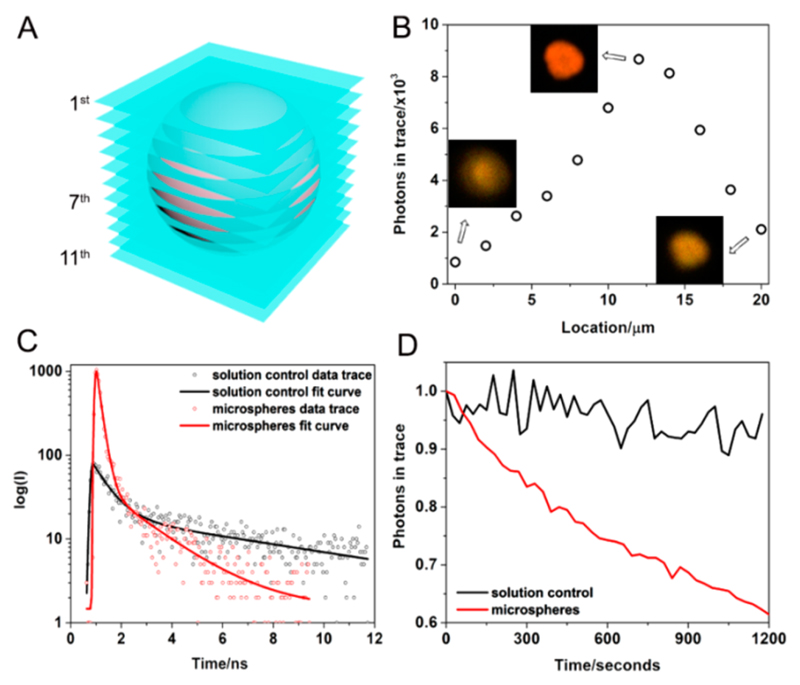

Attenuated Fluorescence Decay and Photostability

Porphyrin has been found to have aggregation-dependent photoluminescence.27 Considering the abundant aromatic moieties in the MCpP-FF molecule and the extensive π−π interactions, the microspheres are expected to show intriguing optical properties. Fluorescent lifetime microscopy (FLIM) characterizations revealed that the emission initially increased across the microsphere transversal planes (Figure 3A). After the center (the diameter of the microsphere studied here was 24 μm), the emission started to attenuate (Figure 3B), along with the FLIM image first becoming more intense and then blurry again (Figure 3B, inset; Video S1), demonstrating that the microspheres are indeed solid inside, consistent with the SEM findings (Figure 1B,C) and still remain fluorescent after aggregation. However, the lifetime decreased considerably (Figure 3C), with only 235.66 ps for the microspheres, compared to 2453.04 ps for the MCpP-FF toluene solution, implying that the fluorescence was quenched significantly due to electron transfer among aromatic moieties. Correspondingly, the fluorescent photostability of the microspheres abruptly attenuated over time, as opposed to the MCpP-FF toluene solution whose photoluminescence largely remained stable (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic FLIM tomo-scanning profile and (B) extracted emission intensity at different transversal planes of the microsphere. The insets show the FLIM images at the 1st, 7th, and 11th transversal planes. (C) Time-resolved fluorescence decay and (D) photostability of the microspheres (red) and MCpP-FF toluene solution (black).

Broad-Spectrum Light Sensitivity of Microspheres

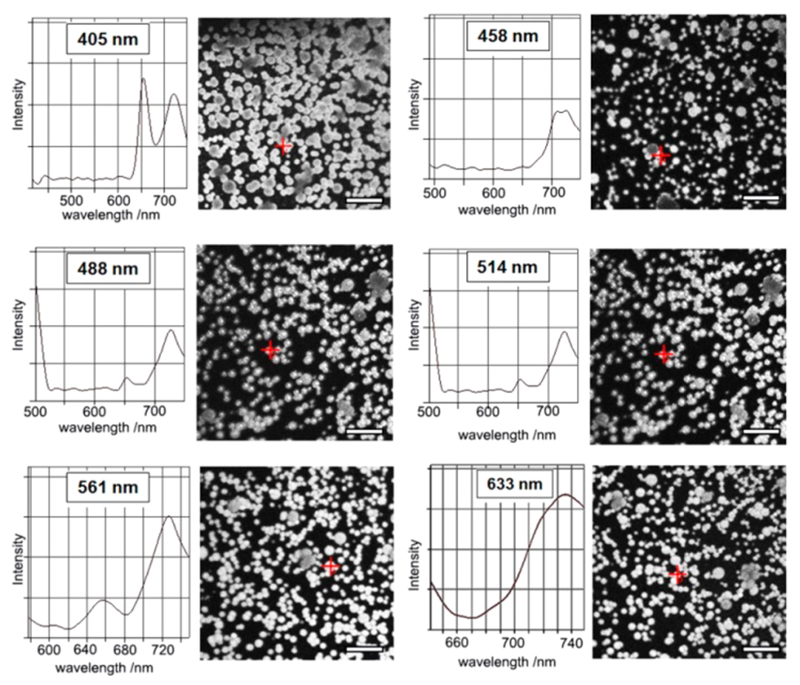

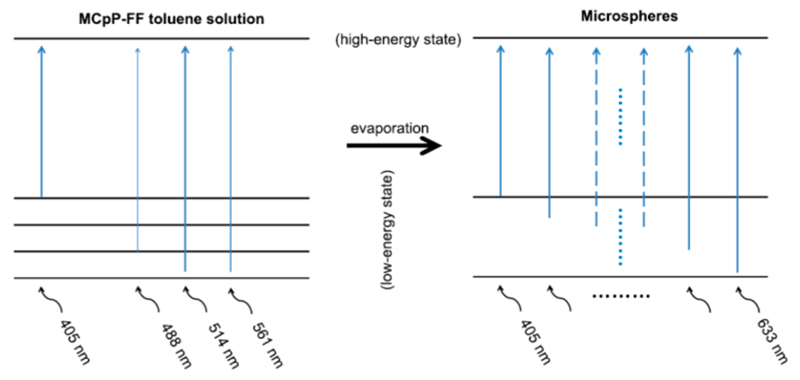

In addition to quenching, the extensive aromatic interactions can result in a shift of the fluorescent wavelength.35,36 Confocal microscopy experiments illustrated that the microspheres constantly emitted fluorescence at 650 nm and at 730 nm, characteristic of free-base porphyrins,37 and did not show any obvious change under different excitations, ranging from 405 to 633 nm (Figure 4). This demonstrates that the extensive π−π stacking resulted in widespread red-shifts of the excitations, thereby producing a broad-spectrum light sensitivity of the microspheres, which can be excited in a larger wavelength range (Scheme 1). As a control, the MCpP-FF toluene solution showed emissions only at several discrete excitations under the same experimental conditions (Figure S10, Scheme 1).

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy images of the microspheres at different excitations (405, 458, 488, 514, 561, and 633 nm), along with the extracted emission spectra at the red crosses. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Scheme 1. Schematic Electron Transition Profiles from Low-Energy States to High-Energy States for MCpP-FF Toluene Solution (left panel) and Microspheres (right panel)a.

aOnly several discrete excitation wavelengths can be absorbed by MCpP-FF toluene solution, while microspheres can be excited in a broad wavelength range.

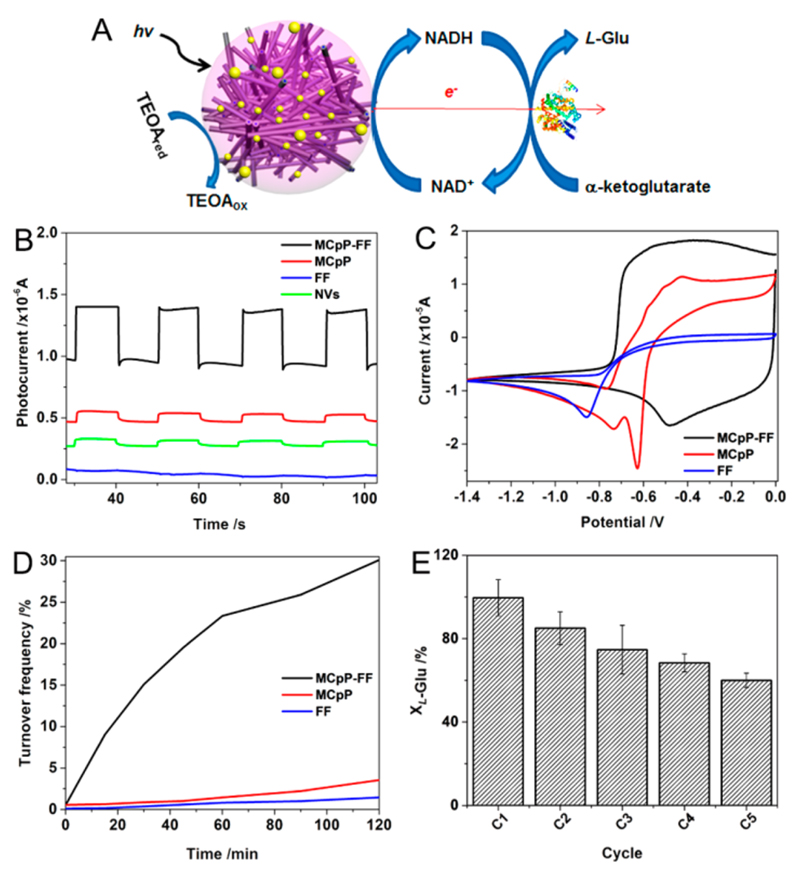

Microspheres as Antennas for Artificial Photosynthesis

The remarkable fluorescence quenching and broad-spectrum light sensitivity, along with the multiporous nature, endow the microspheres a tremendous potential to transform photon energies to electronic signals23 and to be utilized as sunlight-sensitive antennas for artificial photosynthesis (Figure 5A). Photocurrent measurements using triethanolamine (TEOA) as an electron donor illustrated that the microspheres-modified indium tin oxide (ITO) glass slide could produce a remarkably high photocurrent when illuminated by visible light from a 350 W Xe lamp (Figure 5B), compared to the ultralow photocurrents produced by MCpP and FF crystals or by MCpP-FF nanovesicles-modified ITO slides, thus confirming the eminent capability of the microspheres to produce photoelectrons. Furthermore, the microspheres showed a notable catalytic property for electro-redox of Ru(bpy)3Cl2, which generally acts as the electron mediator in photosynthesis systems,3,38 with the reduction potential peak at −0.48 V, compared to −0.63 V and −0.86 V for MCpP-FF and FF crystals, respectively (Figure 5C), illustrating the significant photoelectron transfer ability of the microspheres.

Figure 5.

Artificial photosynthesis using the MCpP-FF microspheres as light-sensitive antennas. (A) Schematic routine of artificial photosynthesis procedure. (B) Photocurrent response and (C) photoinduced cyclic voltammogram of Ru(bpy)3Cl2 in the presence of microspheres (black), MCpP crystals (red), and FF crystals (blue). Note that the photocurrent values in (B) were vertically shifted for clarification, and the data of nanovesicles (NVs) formed in aqueous solution are shown for comparison. (D) Turnover frequency of NADH in the presence of the MCpP-FF/Pt (black), MCpP/Pt (red), and FF/Pt (blue) systems. (E) Cyclic conversion of L-Glu in the presence of the MCpP-FF/Pt system.

The remarkable photoelectron production and transfer features provide the microspheres system the capability to reduce NAD+ to NADH, which are widely utilized as cofactors for many biocatalytic redox reactions.3,38 After being sputtered with Pt nanoparticles (Pt NPs) (Figure S11), which are usually used as catalytic centers,13 the microspheres system (MCpP-FF/Pt) presented a remarkable catalytic property for NADH regeneration, showing a yield of ~30% after 2 h, approximately 12-fold higher than the separate moieties (MCpP/Pt and FF/Pt) (Figure 5D). It should be noted that, in this case, no external mediators were introduced to facilitate the photoelectron transfer, thus simplifying the photosynthesis concept design and the following purifications.23 Subsequently, the regenerated NADH could facilitate the conversion of α-ketoglutarate to L-glutamate (L-Glu) by L-glutamic dehydrogenase (GDH) with nearly 100% efficiency (C1, Figure 5E). In particular, the stability in water promoted easy retrieval of the microspheres for storage and reusability, with a 60% conversion yield of L-Glu after 5 cycles without obvious detachment from the substrate (Figure 5E), thus supplying the possibility to reduce costs and contaminations.

Conclusion and Perspectives

In conclusion, MCpP was covalently conjugated to FF dipeptide to generate a hybrid building block. This bioinspired functional molecule could self-assemble into nanofibers, which then aggregated into multiporous microspheres during solvent evaporation. The abundant and highly organized aromatic interactions resulted in extensive red-shifts of the excitations, as well as a significant attenuation of the fluorescent lifetime and photostability, implying a broad-spectrum light sensitivity and remarkable electron transferring properties of the microspheres. These characteristics allow the microspheres to be used as sunlight-sensitive antennas in artificial photosynthesis, showing a remarkable photoelectron production and transfer capability. This resulted in a high turnover frequency of NADH when sputtered with Pt NPs, which can be used to produce L-Glu in biocatalytic reactions, without the need of external mediators. In particular, the stability against water endows the microspheres ease of retrieval and reuse, showing a sustainable application potential.

In the long term, the multiporous nature and innate ability to complex metal ions of porphyrin can allow the microspheres to act as mesoporous materials for photosensitive adsorption and photodriven reaction catalysis. Considering the intrinsic limitations of the traditional inorganic counterparts, such as zeolites, this kind of bioinspired functional material can potentially become a predominant supplement, or even a substitute, for light-sensitive applications.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00966.

Video of the tomo-scanning FLIM profile

RP-HPLC and MS profiles, pictures of solutions at different concentrations, statistical size distributions, microspheres formed on different substrates, more SEM images of the nanostructures, XRD result of the microspheres, and confocal microscopy profiles of MCpP-FF toluene solution

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Israeli National Nanotechnology Initiative, the Helmsley Charitable Trust for a Focal Technology Area on Nanomedicine for Personalized Theranostics, and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (No. 694426) (E.G.). The authors thank Dr. Alex Barbul for confocal microscopy experiment assistance, Dr. Yishay (Isai) Feldman and Dr. Yuri Rosenberg for XRD experiment assistance, Dr. Sigal Rencus-Lazar for language editing, and the members of the Wang and Gazit laboratories for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- (1).Gust D, Moore TA, Moore AL. Mimicking photosynthetic solar energy transduction. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:40–48. doi: 10.1021/ar9801301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zou QL, Liu K, Abbas M, Yan XH. Peptide-modulated self-assembly of chromophores toward biomimetic light-harvesting nano-architectonics. Adv Mater. 2016;28:1031–1043. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lee SH, Kim JH, Park CB. Coupling photocatalysis and redox biocatalysis toward biocatalyzed artificial photosynthesis. Chem - Eur J. 2013;19:4392–4406. doi: 10.1002/chem.201204385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Baskaran D, Mays JW, Zhang XP, Bratcher MS. Carbon nanotubes with covalently linked porphyrin antennae: photoinduced electron transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6916–6917. doi: 10.1021/ja0508222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Tanase M, Bauer LA, Hultgren A, Silevitch DM, Sun L, Reich DH, Searson PC, Meyer GJ. Magnetic alignment of fluorescent nanowires. Nano Lett. 2001;1:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Winkelmann CB, Ionica I, Chevalier X, Royal G, Bucher C, Bouchiat V. Optical switching of porphyrin-coated silicon nanowire field effect transistors. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1454–1458. doi: 10.1021/nl0630485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Choi SJ, Lee YC, Seol ML, Ahn JH, Kim S, Moon DI, Han JW, Mann S, Yang JW, Choi YK. Bio-inspired complementary photoconductor by porphyrin-coated silicon nanowires. Adv Mater. 2011;23:3979–3983. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Li C, Ly J, Lei B, Fan W, Zhang DH, Han J, Meyyappan M, Thompson M, Zhou CW. Data storage studies on nanowire transistors with self-assembled porphyrin molecules. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:9646–9649. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rao CNR, Govindaraj A. Synthesis of inorganic nanotubes. Adv Mater. 2009;21:4208–4233. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Remškar M. Inorganic nanotubes. Adv Mater. 2004;16:1497–1504. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhang SG. Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1171–1178. doi: 10.1038/nbt874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tao K, Wang JQ, Li YP, Xia DH, Shan HH, Xu H, Lu JR. Short peptide-directed synthesis of one-dimensional platinum nanostructures with controllable morphologies. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2565. doi: 10.1038/srep02565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Tao K, Levin A, Adler-Abramovich L, Gazit E. Fmoc-modified amino acids and short peptides: simple bio-inspired building blocks for the fabrication of functional materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:3935–3953. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00889a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kim S, Kim JH, Lee JS, Park CB. Beta-sheet-forming, self-assembled peptide nanomaterials towards optical, energy, and healthcare applications. Small. 2015;11:3623–3640. doi: 10.1002/smll.201500169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wang J, Liu K, Xing RR, Yan XH. Peptide self-assembly: thermodynamics and kinetics. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:5589–5604. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00176a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yan XH, Zhu P, Li JB. Self-assembly and application of diphenylalanine-based nanostructures. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1877–1890. doi: 10.1039/b915765b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Adler-Abramovich L, Gazit E. The physical properties of supramolecular peptide assemblies: from building block association to technological applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:6881–6893. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00164h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Rosenman G, Beker P, Koren I, Yevnin M, Bank-Srour B, Mishina E, Semin S. Bioinspired peptide nanotubes: deposition technology, basic physics and nanotechnology applications. J Pept Sci. 2011;17:75–87. doi: 10.1002/psc.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Li Q, Jia Y, Dai LR, Yang Y, Li JB. Controlled rod nanostructured assembly of diphenylalanine and their optical waveguide properties. ACS Nano. 2015;9:2689–2695. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Yang XK, Fei JB, Li Q, Li JB. Covalently assembled dipeptide nanospheres as intrinsic photosensitizers for efficient photodynamic therapy in vitro. Chem - Eur J. 2016;22:6477–6481. doi: 10.1002/chem.201600536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Azuri I, Adler-Abramovich L, Gazit E, Hod O, Kronik L. Why are diphenylalanine-based peptide nanostructures so rigid? Insights from first principles calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:963–969. doi: 10.1021/ja408713x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Xue B, Li Y, Yang F, Zhang C, Qin M, Cao Y, Wang W. An integrated artificial photosynthesis system based on peptide nanotubes. Nanoscale. 2014;6:7832–7837. doi: 10.1039/c4nr00295d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kim JH, Lee M, Lee JS, Park CB. Self-assembled light-harvesting peptide nanotubes for mimicking natural photosynthesis. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:517–520. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kim JH, Nam DH, Lee YW, Nam YS, Park CB. Self-assembly of metalloporphyrins into light-harvesting peptide nanofiber hydrogels for solar water oxidation. Small. 2014;10:1272–1277. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zou Q, Zhang L, Yan XH, Wang A, Ma G, Li JB, Möhwald H, Mann S. Multifunctional porous microspheres based on peptide-porphyrin hierarchical co-assembly. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:2366–2370. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tao K, Jacoby G, Burlaka L, Beck R, Gazit E. Design of controllable bio-inspired chiroptic self-assemblies. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:2937–2945. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Liu K, Xing R, Chen C, Shen G, Yan L, Zou Q, Ma G, Möhwald H, Yan XH. Peptide-induced hierarchical long-range order and photocatalytic activity of porphyrin assemblies. Angew Chem. 2015;127:510–515. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zou QL, Abbas M, Zhao LY, Li SK, Shen GZ, Yan XH. Biological photothermal nanodots based on self-assembly of peptide-porphyrin conjugates for antitumor therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:1921–1927. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Charalambidis G, Kasotakis E, Lazarides T, Mitraki A, Coutsolelos AG. Self-assembly into spheres of a hybrid diphenylalanine-porphyrin: Increased fluorescence lifetime and conserved electronic properties. Chem - Eur J. 2011;17:7213–7219. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Charalambidis G, Georgilis E, Panda MK, Anson CE, Powell AK, Doyle S, Moss D, Jochum T, Horton PN, Coles SJ, et al. A switchable self-assembling and disassembling chiral system based on a porphyrin-substituted phenylalanine–phenylalanine motif. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12657. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Liu XC, Fei JB, Wang AH, Cui W, Zhu PL, Li JB. Transformation of dipeptide-based organogels into chiral crystals by cryogenic treatment. Angew Chem. 2017;129:2704–2707. doi: 10.1002/anie.201612024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Tao K, Adler-Abramovich L, Gazit E. Controllable phase separation by Boc-modified lipophilic acid as a multifunctional extractant. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17509. doi: 10.1038/srep17509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Israelachvili JN, Mitchell DJ, Ninham BW. Theory of self-assembly of hydrocarbon amphiphiles into micelles and bilayers. J Chem Soc, Faraday Trans 2. 1976;72:1525–1568. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Smith AM, Williams RJ, Tang C, Coppo P, Collins RF, Turner ML, Saiani A, Ulijn RV. Fmoc-diphenylalanine self assembles to a hydrogel via a novel architecture based on π-π interlocked β-sheets. Adv Mater. 2008;20:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Tao K, Yoskovitz E, Adler-Abramovich L, Gazit E. Optical property modulation of Fmoc group by pH-dependent self-assembly. RSC Adv. 2015;5:73914–73918. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Minaev B, Lindgren M. Vibration and fluorescence spectra of porphyrin-cored 2,2-Bis(methylol)-propionic acid dendrimers. Sensors. 2009;9:1937–1966. doi: 10.3390/s90301937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Choudhury S, Baeg JO, Park NJ, Yadav RK. A photocatalyst/enzyme couple that uses solar energy in the asymmetric reduction of acetophenones. Angew Chem. 2012;124:11792–11796. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video of the tomo-scanning FLIM profile

RP-HPLC and MS profiles, pictures of solutions at different concentrations, statistical size distributions, microspheres formed on different substrates, more SEM images of the nanostructures, XRD result of the microspheres, and confocal microscopy profiles of MCpP-FF toluene solution