Abstract

Safe and efficient gene therapy is highly desired for controlling pathogenic fibrosis of nucleus pulposus (NP) tissue, which would result in intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration and disability if left untreated. In this work, a hyperbranched polymer (HP) with high plasmid DNA (pDNA) binding affinity and negligible cytotoxicity is synthesized, which can self-assemble into nano-sized polyplexes with a “double shell” structure that can highly efficiently transfect pDNA into NP cells. These polyplexes are then encapsulated in biodegradable nanospheres (NS) to enable two-stage delivery: 1) temporally-controlled release of pDNA-carrying polyplexes and 2) highly efficient delivery of pDNA into cells by the released polyplexes. These biodegradable NS are co-injected with nanofibrous spongy microspheres (NF-SMS) to localize the cellular transfection of the pDNA encoding orphan nuclear receptor 4A1 (NR4A1), which was recently reported as a therapeutic agent to delay pathogenic fibrosis. It is shown that HP can transfect human NP cells efficiently in vitro with low cytotoxicity. The two-stage delivery system is able to present the polyplexes over a sustained time period (more than 30 days) in the tail of rat. The NR4A1 pDNA carried by the HP polyplexes is found to therapeutically reduce the pathogenic fibrosis of NP tissue in a rat-tail degeneration model. In conclusion, the combination of the two-stage NR4A1 pDNA delivery NS and NF-SMS is able to repress fibrosis and to support IVD regeneration.

Keywords: Gene therapy, nonviral gene carrier, hyperbranched polymer, fibrosis, nucleus pulposus regeneration, nuclear receptor

Introduction

Low back pain is a major cause of disability, affecting approximately 632 million people globally [1]. Although there are various triggers that cause lower back pain, several studies have confirmed that degeneration of the intervertebral disc (IVD) is clinically associated with chronic low back pain [2-5]. The degenerative process normally begins from the inner part of the disc, known as the nucleus pulposus (NP). The etiology of IVD degeneration remains not entirely clear but is known to be associated with multiple factors, including mechanical overloading, defective nutrient supply, cell death, progressive fibrosis and so forth [6-8]. Back pain is most frequently the result of impingement of local nerves by herniation or bony structures resulted from the degenerated disc. Anatomical studies of autopsies and surgical specimens show evidence of fibrosis in the majority of degenerated discs [9-12]. Fibrosis is common under chronic inflammatory conditions and is associated with excessive tissue remodeling and abnormal collagen matrix deposition [13-19]. This advanced pathological progression is irreversible and eventually leads to serious clinical symptoms. To date, there are no effective antifibrotic drugs to ameliorate fibrotic disease. While there are clinical trials on cell transplantations [20-22], the current clinical treatments are mainly limited to ameliorating symptoms. Cumulative evidence indicates that the TGF-β signaling pathway plays a central role in fibrotic disease [23]. TGF-β is a master regulator of mesenchymal responses under physiological and pathological conditions. In fibrotic diseases, persistent TGF-β signaling results in chronic activation of fibroblasts and a massive accumulation of extracellular matrix. Therefore, inhibition of TGF-β signaling to a physiological level might be of therapeutic potential for treating fibrotic diseases. Nuclear receptors are a family of transcription factors that are increasingly recognized as regulators of tissue responses. The orphan nuclear receptor 4A1 (NR4A1, also known as NUR77) has been shown to have pleiotropic regulatory effects on glucose and lipid metabolism [24, 25], inflammatory responses [26, 27], and vascular homeostasis [28]. It was recently reported that the lack of active NR4A1 lead to persistent activation of TGF-β signaling and pathological tissue fibrosis, and small-molecule NR4A1 agonists inhibit skin, lung, liver, and kidney fibrosis in mice [29]. Thus, NR4A1 is a potential novel therapeutic target for treating fibrosis. However, whether NR4A1 agonists can inhibit fibrosis in NP has not been investigated. Considering that orally administering NR4A1 may inhibit TGF-β signaling in normal cells and result in off-target toxicity, we hypothesized that delivery of NR4A1 plasmid DNA (pDNA) in a local and sustained manner may yield the desired antifibrotic activity to rescue fibrosis-associated NP degeneration.

While gene therapy (DNA or RNA delivery) is of promise for the treatment of fibrotic disc degeneration [5], a fundamental engineering challenge of gene therapy is the development of safe and effective delivery vectors [30-35]. While viral vectors including adenovirus, adeno-associated virus, and lentivirus have been reported as gene delivery systems in IVD tissues [36-39], their potential side effects or limited transfecting capacity in gene size remain a concern [40-42]. Nonviral gene delivery carriers including cationic polymers are nonimmunogenic, versatile, relatively easy to handle, and often mass-producible. A commercially available polyethylenimine (PEI) (25000 Da) has been widely used as a “gold standard” to evaluate transfection efficiency of newly developed polymer or surfactant based gene carriers. However, PEI is not biodegradable and its high molecular weight contributes to significant cytotoxicity. In addition, pDNA degradation by ubiquitous nucleases and exchange reactions with anionic macromolecules under a physiological environment may lead to reduced transfection efficiency in vivo [43-46].

We recently developed a hyperbranched polymer (HP) vector, in which short polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains and a low molecular weight cationic PEI are attached to the outer shell of a hyperbranched hydrophobic molecular core [47]. With such a structure, the polyplexes have high stability, low cytotoxicity and high miRNA transfection efficiency. We hypothesize that this delivery system is also efficient for DNA delivery and tested this hypothesis for the first time in this study. DNA has been entrapped in gels or micelles previously [48-50]. However, most of such systems release the entire cargo within a few hours. To overcome uncontrolled release associated with current plasmid DNA delivery systems, we encapsulated the stable HP polyplexes carrying plasmid DNA in biodegradable PLGA nanospheres (NS) for the first time. This two-stage gene delivery strategy aims to achieve both a controllable duration (polyplexes to be released from NS - the first stage) and the high transfection efficiency (polyplexes to carry the pDNA into the cells - the second stage).

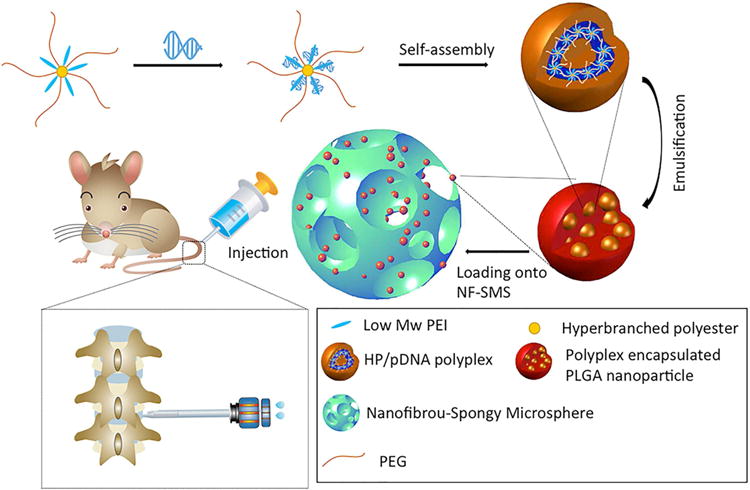

We combine the PLGA NS containing the NR4A1 pDNA-carrying polyplexes with newly developed nanofibrous spongy microspheres (NF-SMS) to form a novel injectable scaffold, which enable temporally-controlled release of polyplexes and efficient pDNA transfection into cells on the NF-SMS (Fig. 1). We denote this novel injectable scaffold and two-stage delivery system as HP/NS/NF-SMS. In addition to characterizing this new system, human NP cell culture and rat-tail IVD degeneration models are established to test 1) whether the HP/NS/NF-SMS delivery system can safely and efficiently deliver the pDNA into NP cells, 2) whether the overexpression of NR4A1 by such gene transfection strategy can reverse fibrosis, and 3) whether the injectable NF-SMS with the sustained NR4A1 transfection capacity enable regenerative NP repair following fibrotic degeneration.

Fig. 1. Two-stage delivery of pDNA from PLGA nanospheres loaded on nanofibrous spongy microspheres (NF-SMS).

The HP-pDNA polyplexes were encapsulated into PLGA nanospheres via a double emulsion method and the PLGA nanospheres containing the HP-pDNA polyplexes were then added to the PLLA NF-SMS. The PLLA NF-SMS with the PLGA nanospheres were injected into the nucleus pulposus (NP) of a rat tail.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Polyethylenimine (PEI, Mw 800 Da and 25 kDa), polyethylene glycol methyl ether (PEG, Mw 2000 and 20000 Da), and hyperbranched bis-MPA polyester (H40: 64 hydroxyl groups) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. pDNA NR4A1 was constructed by cloning the NR4A1 cDNA fragment into pcDNA3.1 (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). The structure of plasmid NR4A1 was confirmed by sequence assay and RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S7). The pDNA GFP and Luc was constructed by the vector core at the University of Michigan.

Preparing HP/NS/NF-SMS

The polyplexes were encapsulated in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanospheres (NS) using the double emulsion method. The polyplexes-loaded PLGA NS were immobilized onto the surface of the NF-SMS via a solvent annealing treatment method, which was developed in our laboratory [51]. Briefly, the PLGA NS and NF-SMS were mixed in a certain ratio and the particle mixtures were then subjected to a mixed solvent of hexane/THF (volume ratio of 9/1) followed by vacuum-drying for 2 days to remove the residual solvent.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Polymer constructs were rinsed in PBS, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde overnight, post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, and dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol and hexamethyldisilazane. The specimens were then sputter-coated with gold and observed under a scanning electron microscope (Philips XL30 FEG) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

Patients

Human NP tissues were obtained from 8 patients from West China Hospital, Sichuan University, with the approval of West China Hosptial's Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Patient specimens were obtained surgically from individuals with herniated discs (average age 67.3 years old, n=2, Pfirrmann grade V) and individuals with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (average age 18.9 years old, n=6). Five of these volunteers were female and three were male. NP tissues from herniated discs and scoliosis patients were both used for histological staining and real-time analysis. Only cells from healthy NP tissue were used for in vitro cell study. Every time when we conducted an experiment with cells from one patient, we repeated the procedure with cells from 2 different patients. The data in our manuscript are representative of the triplicate samples.

Cell isolation and culture

NP cells were isolated and cultured according to published methods [52]. Briefly, IVD with surrounding tissues were surgically harvested and immediately transported to the laboratory. The NP tissue was separated from the surrounding annulus fibrosus, cut into small pieces, and digested in a collagenase solution (0.2% w/v collagenase type II at 37 °C for 4 h). The cell-collagenase suspension was filtered through a 180 μm cell strainer, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min and washed twice in PBS. The cells were seeded onto 75 cm2 flasks at a density of 2500 cells/cm2 and cultured in high-glucose DMEM medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Culture medium was changed on day 6 after cell seeding and twice a week thereafter. Cells were expanded through 2 passages and were pooled for further study.

In vitro transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity

Luc-encoded pDNA-loaded HP polyplexes were prepared first. Polymer solutions (1.0 mg/ml) were added slowly to DNA solutions containing 1 μg of DNA. The amount of polymer added was calculated on the basis of chosen N/P ratios of polymer/DNA (nitrogen atoms of the polymer over phosphates of DNA). The final DNA concentrations were adjusted to 33.3 μg/mL for in vitro experiments. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min for complex formation. Gene transfection efficiency of HP was evaluated in vitro using NP cell cultures with Luc-encoded pDNA-loaded HP polyplexes. NP cells were seeded on 24-well plates (2×104 cells/well) and cultured to reach 70%-80% cell confluency. Then 30 μL HP-Luc pDNA polyplex suspensions at various N/P ratios were added. After 24 h incubation, the transfection medium was replaced with fresh complete DMEM medium. 24 h later, cells were washed with PBS and lysed with luciferase cell culture lysis reagent buffer. The luciferase activity of the lysates was measured using Mithras LB 940 (Berthold Technologies, USA). Gene transfection efficiency was expressed as the relative fluorescence intensity per mg protein (RLU/mg protein). In addition, the in vitro gene transfection efficiency of HP was also evaluated using GFP pDNA. After 24 h incubation, GFP expression was determined using a fluorescence microscope. The percentage of GFP positive cells was quantified using flow cytometry. Linear copolymer (LP) and PEI25K (polyethylenimine with an average molecular weight of 25,000 Da) were also used as controls.

In the cytotoxicity assay, NP cells were seeded at a density of 5×103 cells/well in 100 μL DMEM with 10% FBS on 96-well plates and cultured overnight to reach 70-80% cell confluency. The medium was replaced with 100 μl fresh medium. 7.5 μL of HP or LP or PEI25K solution (33.3 mg pDNA/mL) of a specific N/P ratio was added into the corresponding well. 24 h later, 20 μl of 5-mg/mL MTT solution in PBS was added to each well for additional 4 h incubation. The medium was replaced with 100 μl DMSO to dissolve the formazan crystals under gentle agitation. The UV absorbance was detected at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher).

In vitro transfection efficiency of NR4A1

NR4A1 gene transfection into NP cells was evaluated using NR4A1 pDNA-loaded or plasmid DNA3.1-loaded HP polyplexes (N/P ratio=8). After 48 h incubation of 2×104 cells/well in 400 μL DMEM with 10% FBS, the transfection medium was replaced with fresh medium. Real time PCR were used to measure the NR4A1 gene expression after transfection. Protein content of NR4A1 was determined using immunofluorescence staining and Western blotting.

To verify that overexpression of NR4A1 could result in protective effects against a fibrotic response induced by the TGF-β signaling pathway, we examined the α-SMA expression and stress fiber formation in human NP cells (transfected by HP loaded with NR4A1 pDNA or blank plasmid DNA) incubated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml-1, PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany). The immunofluorescence staining for NR4A1, α-SMA and stress fibers was performed. Human NP cells (transfected by HP loaded with NR4A1 pDNA or blank plasmid DNA) incubated with normal cell culture medium were used as control. For immunofluorescence staining, NP cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X100, washed twice with 0.1% goat serum in PBS, and stained with appropriate primary antibodies against NR4A1 and a-SMA (sc-7014, sc-58670, from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, 1:10,000 dilution, with a final concentration of 0.02μg/ml) in 0.2% Triton-X100/2% goat serum in PBS. Alexa Fluor antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488, 568, Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) were used as secondary antibodies. Stress fibers were visualized with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (no. R415, Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany, dilution 1:250). In addition, cell nuclei were stained using 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

For real time PCR analysis, the total RNA was extracted from NP cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNAs were synthesized using a Geneamp PCR (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan reverse transcription reagents following the manufacturer's protocol. Specific primers used are listed below: assay ID Hs00374226_m1 (NR4A1), Hs00998193_m1 (Smad7), Hs00167155_m1 (Serpine1), Hs00426835_g1 (Acta2) and Hs00164004_m1 (Col1A1), Applied Biosystems.

For Western blot analysis, total protein was extracted using the EpiQuik whole-cell extraction kit (Epigentek, USA). Protein was applied and separated on 4-15% NuPAGE gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, USA). The membrane were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and incubated with specific antibodies (sc-5569, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, 1:10,000 dilution, with a final concentration of 0.02μg/ml) overnight. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (1:10,000 dilution) from Santa Cruz Bio-technology (Santa Cruz, USA) was used to treat the membrane for 1h, after which the membranes were enhanced with a SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo, USA). The relative amounts of the transferred proteins were quantified with scanning the autoradiographic films. Total protein was normalized to the corresponding β-actin level (no. A5441, Sigma, USA, dilution 1:10,000).

Co-immunoprecipitation (CoIP)

NP cells were collected in lysis buffer (400 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), and 1 mM EDTA). 100 μL lysis buffer was mixed with 2×107 cells by vortexing vigorously for 2-3 sec at the maximum speed. The cell suspension was then transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and diluted with 0.9 mL lysis buffer. Ten percent of the lysate was used as input. Cell extracts were incubated with 20 μl Protein A/G Sepharose and 3 μg of either NR4A1, specificity protein 1 (SP1) or normal IgG antibodies (no. sc-5569, no. sc-59 and no. sc-2027, all Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany). Unbound proteins were removed by washing with 150 mM NaCl/0.05% NP-40. Sepharose-bound protein complexes were separated via SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting on a PVDF membrane. Proteins were visualized via ECL prime kit (GE Healthcare, Braunschweig, Germany).

Animal studies

The animal experiments were performed following a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Michigan. 32 Sprague-Dawley rats (three months old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The surgical procedure was performed following literature [53]. The animals were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and monitored by an assistant during the surgery. The intervertebral space was located by digital palpation and confirmed by counting the vertebrae from sacral region under fluoroscopic guidance. After surgical preparation of the skin with povidone-iodine solution, each rat tail was punctured at the IVD between fifth to sixth and seventh to eighth coccygeal vertebrae (Co5/Co6 and Co7/Co8). A 21G needle was carefully inserted at the center of disc level, perpendicular to the skin, and parallel to the end plates. The tip of the needle was placed in the center of the NP at a depth of 5 mm from the skin followed by 180° rotation and a five-second hold. After every procedure, fluoroscopy was taken to confirm the correct level and needle position within intervertebral disc.

Two weeks after injury, pDNA was delivered to the animals. For in vivo transfection efficiency investigation, red fluorescent protein (RFP) pDNA loaded HP (2 μL, 100 μg/mL, N/P =8), HP/NS or HP/NS/NF-SMS were slowly injected into the disc using a microsyringe attached to a 31-G needle under fluoroscopic guidance. The samples were harvested at day 28 after transfection. For fluorescent microscopy, 4.0% paraformaldehyde fixed, OCT compound (Tissue-Plus, Fisher Healthcare) embedded sections (5μm) were prepared after a snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Then the sections were treated with 0.25% Triton-X100 and stained with appropriate primary antibodies. For evaluation of NR4A1 pDNA gene delivery as a therapeutic approach to disc degeneration, animals were divided into four groups: a normal control group (without any surgical procedure), a degeneration model group (with needle puncture, without gene therapy), a blank pDNA group (with needle puncture, followed by injection of HP-blank/NF-SMS, N/P=8) and a HP-NR4A1/NF-SMS group (with needle puncture, followed by injection of HP-NR4A1 pDNA/NF-SMS, N/P=8). After 4 weeks, the rats were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by bilateral thoracotomy and the discs were harvested for analysis.

Radiographic and μCT Evaluation

Radiographs (x-ray) and μCT images were taken preoperatively and 4 weeks after gene delivery. The IVD height was expressed as the disc height index (DHI) based on the method of Masuda et al [54]). The average DHI was calculated by averaging the measured disc heights obtained from the anterior, middle, and posterior portions of the IVD and divided by the average of adjacent vertebral body heights. Changes in the DHI of injected discs were expressed as %DHI and normalized by the measured preoperative DHI (%DHI=postoperative DHI/preoperative DHI ×100).

Bioluminescence imaging

To quantify the in vivo gene delivery efficiency, Luc-encoding pDNA loaded HP (50 μL, 100 μg/mL, N/P =8), HP/NS or HP/NS/NF-SMS were slowly injected into the disc using a microsyringe attached to a 31-G needle under fluoroscopy. Firefly luciferase activity was quantified using a bioluminescence intensity (BLI) imaging system at 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30 days after injection. In BLI imaging process, the isoflurane gas was delivered to the animal via a vaporizer with controls to precisely regulate the dose. The animals were intraperitoneally injected with 150 mg/kg body of D-luciferin before being anesthetized. BLI was measured 10 minute after the D-luciferin injection.

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

The specimens were washed in PBS, fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS overnight, decalcified in 10% formic acid solution, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. For histological analysis, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), Safranin-O (SO) and Masson Trichrome. For immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, rehydrated sections were pre-treated with papain solution for 15 min, incubated with NR4A1 antibody (sc-7014, Santa Cruz Inc, USA) at 1:100 dilutions (2μg/ml) for 1 hour and detected by a cell & tissue staining kit (R&D systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manual. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Positive and negative controls were also stained with the study samples to validate the immunohistochemical staining.

To quantify the histological results, we calculated the histological scores based on the method of Masuda et al [54]. Briefly, the slides were graded based on the histological appearance of 4 parameters: the annulus fibrosus, the border between the annulus fibrosus and NP, the cellularity of NP, and the matrix of NP. Each of the 4 parameters was given a grade of 1, 2, or 3. The sum of the grades for each parameter yielded a total grade. Total grades ranged from 4 to 12 with 12 representing severe degeneration.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were reported as means ± standard deviations (SD). The experiments were performed twice to ensure reproducibility, and the results from one representative experiment are shown. For a two-group comparison, a Student's t-test was applied if the pretest for normality (D'Agostino-Pearson normality test) was not rejected at the 0.05 significance level; otherwise, a Mann-Whitney U-test for nonparametric data was used. The significance of differences between more than two groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Fisher's least significant difference as a post hoc test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and Discussion

Polymer synthesis

We synthesized two biodegradable polymers (one linear polyester and one hyperbranched polyester, abbreviated as LPE and HPE, respectively). Low molecular weight PEI and PEG chains were attached to the synthesized polyesters with click chemistries (Supplementary Fig 1 & Supplementary Fig 2) to form the linear copolymer (LP) and hyperbranched copolymer (HP) [47]. The hydrophilic PEG is biocompatible and can form a stealth layer to protect the inner polymer/plasmid polyplexes.

Controlled two-stage DNA release

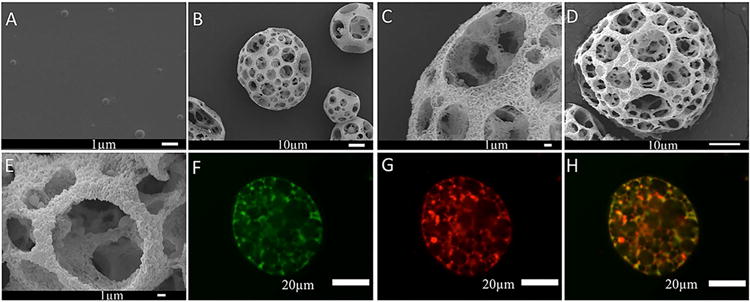

To achieve the first-stage of controlled release of HP-pDNA polyplexes, the polyplexes were encapsulated in PLGA NS with an average diameter of 300 nm using a well-established double emulsion method (Fig. 2 A). These HP-pDNA polyplexes loaded PLGA NS were combined with NF-SMS (Fig 2 B-H). The interconnectivity between pores is important for cell migration and mass transfer and the NF morphology is advantageous for NP regeneration [55, 56]. The release profile of pDNA polyplexes was examined (Supplementary Fig. 3). The NS were made of PLGA with an average molecular weight of 6.5k (PLGA6.5k) or 64k (PLGA64k). Following the burst release of either LP-pDNA or HP-pDNA polyplexes during the first day, there was sustained release of the polyplexes from the PLGA6.5k NS for approximately 2 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, following the burst release of polyplexes during the first day, there was sustained release of the polyplexes from the PLGA64k NS for more than a month. To achieve the longer-time two-stage release, nanospheres made of PLGA64k NS were used for the remainder of the study.

Fig 2. SEM and confocal microscopy images of PLGA nanospheres (NS) containing the HP-pDNA polyplexes loaded on nanofibrous spongy microspheres (NF-SMS).

(A) SEM view of HP-pDNA containing NS; (B, C) SEM views of the NF-SMS before NS incorporation at 1000× and 5000× magnifications, respectively, showing the interconnected porous structure (B) and nanofibers (average diameter 100 nm) on the pore walls (C); (D, E) SEM views of the NF-SMS after NS incorporation at 2000× and 5000× magnifications, respectively. (F, G) 2D cross-sectional confocal images of the NF-SMS after NS incorporation. The NF-SMS and pDNA were labeled with FITC (F) and Cy3 (G), respectively. (H) The merge of images F and G.

In vitro transfection efficiency into NP cells

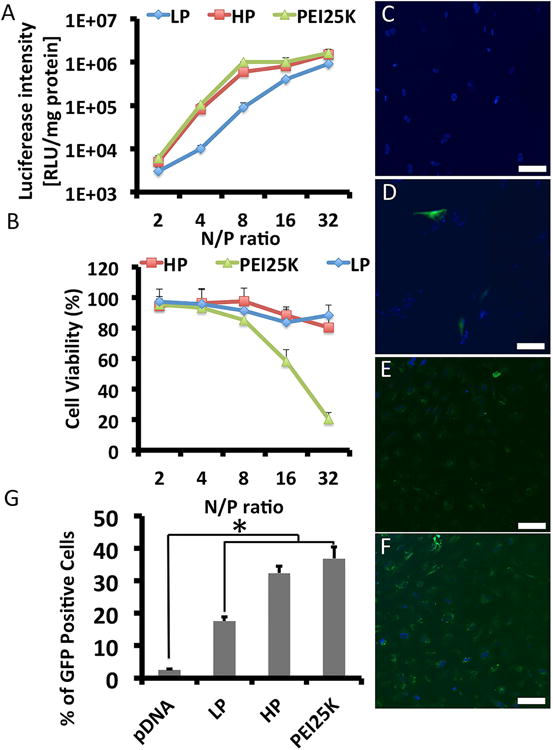

A luciferase assay was first used to quantitatively compare the transfection efficiencies of HP and LP vectors that were loaded with Luciferase pDNA. The luciferase activities of HP and LP at various N/P ratios were evaluated. HP achieved ∼10 times higher luciferase activity than LP at N/P ratios of 4 and 8 (Fig 3A). Higher N/P ratios were necessary for LP to achieve comparable luciferase activity to that of HP. Cytotoxicity of HP and LP was also evaluated. When the N/P ratio was from 2 to 32, the cytotoxicity levels of HP were comparable to those of LP and were almost negligible (Fig 3B). The hyperbranched structure of the polymer did not result in increased cytotoxicity. In the PEI25K (polyethylenimine with an average molecular weight 25,000 Da) group, significantly lower cell viability was observed for a N/P ratio range of 8-32, indicating high cytotoxicity. Given that HP showed high transfection efficiency and low cytotoxicity at low N/P ratios (4 and 8), HP at an N/P ratio of 8 was chosen for the following studies.

Fig. 3. In vitro luciferase expression (A), cytotoxicity (B) and GFP gene transfection efficiency (C-G).

(A) HP, LP, and PEI 25KD (polyethylenimine, molecular weight = 25 kDa) loaded with Luc pDNA at varying N/P ratios transfected into NP cells. HP achieved ∼10 times higher luciferase expression compared to LP at N/P ratios of 4 and 8. Higher N/P ratios were necessary for LP to obtain comparable transfection efficiency to HP. (B) For N/P ratios of 2-32, the toxicity level of HP was comparable to LP and almost negligible. No increased cytotoxicity due to the hyperbranched structure was observed. In the PEI 25KD group, significantly lower cell viability was observed for N/P ratios of 8-32, which indicated significant cytotoxicity of this polymer. (C-G) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of transduced cells at 48 h post-transfection: (C) naked pDNA, (D) PEI 25K-pDNA, (E) LP-pDNA, and (F) HP-pDNA. (G) The GFP positive ratios of nucleus pulposus cells after gene transfection determined by flow cytometry. Error bars in the graph represent SEM, n = 4, *P < 0.05.

To further evaluate the transfection efficiency of the HP into NP cells, GFP pDNA was used as the reporter gene loaded into HP, and GFP expression was observed directly under a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 3C-G). A significantly stronger fluoresce intensity of GFP was found in the HP group than in the LP group (N/P=8). While a strong GFP fluorescence was found in the PEI25K group (N/P=8), high cytotoxicity was also found with PEI25K. The transfection efficiency of HP into NP cells was 32.4±2.6%, while the transfection efficiency of LP into NP cells was 17.6±1.3%.

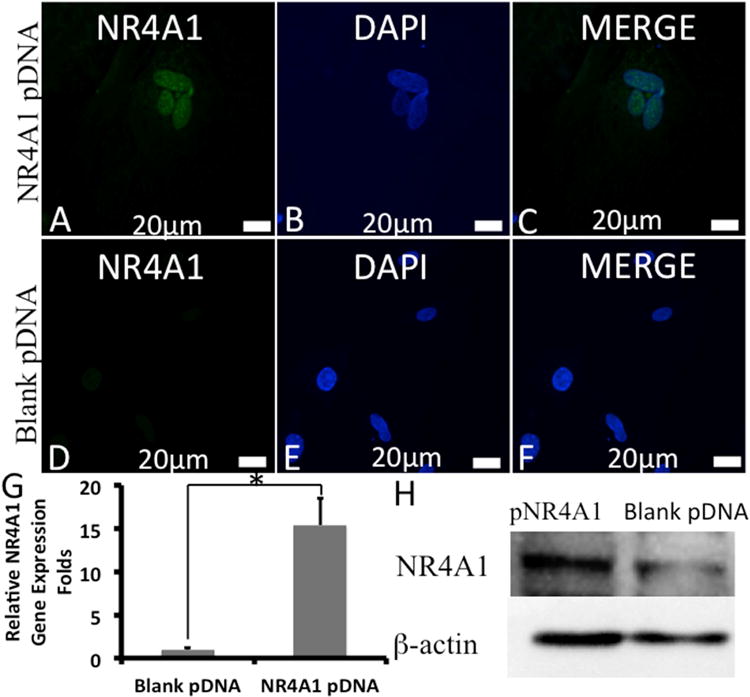

Moreover, to verify the transfection efficiency of HP for the NR4A1 pDNA, NP cells were transfected with NR4A1 pDNA-loaded HP at an N/P ratio of 8. HP loading of a blank plasmid DNA without NR4A1 expression was used as a negative control. At 48 h after transfection, a significantly stronger fluorescent staining for NR4A1 was found in the cells transfected with NR4A1 pDNA than in the negative control (Fig. 4 A-F). Consistently, NP cells transfected with NR4A1 pDNA-loaded HP expressed significantly higher level of NR4A1 mRNA than control cells as detected using real time PCR (Fig. 4G). In parallel, these NP cells also expressed significantly higher level of NR4A1 protein than control cells as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4. In vitro NR4A1 expression in NP cells transfected with HP-NR4A1 pDNA at N/P = 8.

(A)-(F) Representative CLSM images of cells at 48 h post-transfection: (A)-(C) transfected with HP loaded with NR4A1 pDNA, (D)-(F) transfected with HP loaded with blank pDNA. NR4A1 (green) and nuclei (blue) were stained by a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled antibody and DAPI, respectively. Real time PCR (G) and western blotting (H) of NR4A1 expression in NP cells after transfection. Error bars in the graph represent standard error of the mean, *P < 0.05.

Antifibrotic effect of NR4A1 in NP cells

Using antibodies to stain NR4A1 protein and the fibrosis marker a-smooth muscle actin (a-SMA, encoded by the gene ACTA2), we found that NR4A1 protein was highly expressed in healthy human NP tissue, but was weakly expressed in degenerated human NP tissue (Supplementary Fig. S4A-F). Consistently, NR4A1 mRNA level was significantly higher in healthy NP tissue than in degenerated NP tissue (Supplementary Fig. S4G).

To verify that overexpression of NR4A1 could result in protective effects against a fibrotic response induced by the TGF-β signaling pathway, we examined the α-SMA expression and stress fiber formation in human NP cells incubated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml-1, PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany). Immunofluorescence staining for α-SMA and stress fibers was decreased dramatically in the NR4A1 pDNA transfected group (HP loaded with NR4A1 pDNA) compared to the blank pDNA group (HP loaded with blank plasmid DNA) (Supplementary Fig. S4H-Q). The control group without TGF-β stimulation was stained negatively for α-SMA and stress fibers. This result indicated that the fibrotic effect of TGF-β1 was rescued by NR4A1 overexpression. We also examined the mRNA expression of a number of profibrotic genes including SMAD7, SERPINE1, ACTA2, and COL1A1 in response to the overexpression of NR4A1 in NP cell cultures with or without TGF-β1. There was no statistically significant difference in profibrotic gene expression levels in the cell cultures without TGF-β1 (Supplementary Fig. S5 A-D). However, in the presence of TGF-β1, which upregulate these profibrotic genes (SMAD7, SERPINE1, ACTA2, and COL1A1), the overexpression of NR4A1 achieved by HP NR4A1 pDNA transfection significantly decreased the profibrotic gene expression levels.

In vivo gene transfection and localization

With the above cell culture experiments, we have demonstrated the high in vitro transfection efficiency of NR4A1 pDNA delivered using the new non-viral vector HP and the efficacy of suppressing TGF-β1 associated NP cell fibrosis in the cell culture model. To validate the in vivo pDNA transfection efficacy by HP, HP/NS or HP/NS/NF-SMS, we first loaded the pDNA that encodes red fluorescent protein (RFP) into these delivery systems and injected them into the NP areas of rat-tail discs. At day 28 after the injection, we harvested the discs and observed the slides with fluorescence microscopy. It was found that the HP/NS/NF-SMS group achieved the highest transfection efficiency, the HP/NS achieved the intermediate transfection efficiency, and the HP alone was not able to efficiently transfect NP tissue (Supplementary Fig. S6).

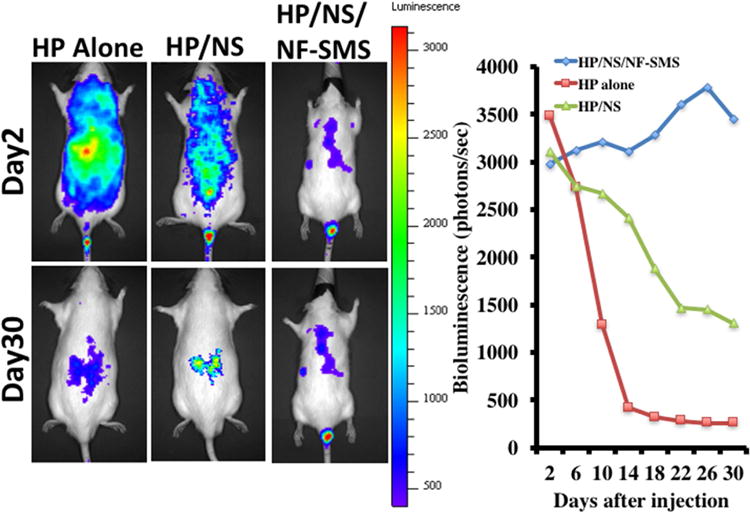

To determine the location of the transfection and to quantify the in vivo transfection efficiency, bioluminescence imaging was carried out. The HP alone was able to transfect luciferase pDNA into cells in the disc area and also quickly throughout the body (day 2), but failed to retain bioluminescence signal at day 30 (Fig. 5). The HP/NS system was also able to transfect luciferase pDNA into cells in the disc area and throughout the body quickly (day 2). The HP/NS system was able to retain some bioluminescence signal in the animal but not in the initially injected disc area at day 30. The HP/NS/NF-SMS system was not only able to transfect luciferase pDNA into cells in the disc area with minimum spreading of bioluminescence signal (day 2), but was also able to retain and increase the bioluminescence signal in the disc location over a prolonged time period (examined at day 30). Therefore, the HP/NS/NF-SMS system was used to deliver NR4A1 pDNA and evaluate the therapeutic efficacy in the remaining study.

Fig. 5. Representative images and quantification of the luciferase expression assayed with an IVIS™ imaging system.

The pDNA-loaded HP polyplexes encapsulated in PLGA nanospheres then incorporated in PLLA nanofibrous spongy microshperes (HP/NS/NF-SMS) were injected locally into the nucleus pulposus area of the rat-tail disc. As controls, HP/pDNA polyplexes (HP alone) or HP/pDNA polyplexes encapsulated in PLGA nanospheres (HP/NS) were also injected. The optical bioluminescence signal was observed at 2 days to 30 days after the injection. A systematically spread bioluminescence signal was found in the HP alone and HP/NS group at day 2, which decreased rapidly with time. At day 30, the signal for luciferase expression disappeared almost completely in the HP alone group, while a weak signal was detected in the HP/NS group. In the HP/NS/NF-SMS group, a locally spread bioluminescence signal was detected at day 2. The signal increased slowly until day 28. The above data indicated that locally controlled gene delivery was achieved in the HP/NS/NF-SMS group.

In vivo gene therapy efficacy

HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS was further used to treat disc fibrosis caused by a needle puncture in a rat-tail model. Four weeks after the treatment (6 weeks after puncture), samples from different treatment and control groups were first evaluated in terms of gross appearance and μCT images (Supplementary Fig. S7A-H). In the punctured group without treatment, the disc height nearly completely disappeared and the most severe fibrosis occurred at the central area of the NP tissue (Supplementary Fig. S7B&F). μCT images indicated greater disc height in the HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS treatment group (Supplementary Fig. S7H) than in the degeneration model group (Supplementary Fig. S7 F). Notably, the HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS group also showed a greater area of translucent disc matrix and less fibrous tissue in gross appearance (Supplementary Fig. S7D). Based on gross appearance and μCT images, the discs in the HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS group were similar to the degeneration model group with narrowing disc height and fibrous tissue invasion (Supplementary Fig. S7C&G).

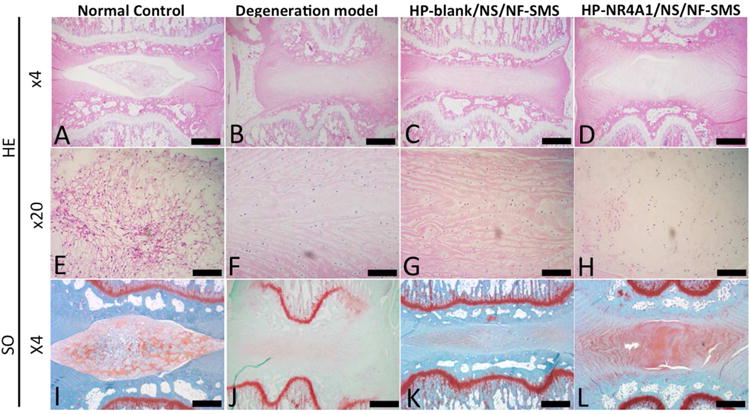

We further evaluated the therapeutic efficacy using histological analysis at 4 weeks after the injection of HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS (Fig. 6A-L). In the intact discs of the normal control group, the oval-shaped NP occupied a large volume of the disc height in the midsagittal cross-section as confirmed by HE staining (Fig. 6A&E). The NP area was stained strongly by safranin-O, indicating a high glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content (Fig. 6I). In the degeneration model group, the disc height collapsed, with evident fibrous tissue invasion (Fig. 6B, F, J). Although discs in the HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS group still displayed a certain degree of degeneration feature (Fig. 6D, H, L), there was clear therapeutic efficacy as compared to the degeneration model group (Fig. 6B, F, J) or HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS group (Fig. 6C, G, K). The NP area in the HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS group was similar to the normal control and stained positively with safranin O (Fig. 6K). In the HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS group, inhomogeneous fibrous tissue was found (Fig. 6C), and the NP area was stained negatively with safranin O (Fig. 6K).

Fig. 6. HE and SO stained disc images from different experimental groups at four weeks after injection.

In the intact discs of the normal control group (A, E), the oval-shaped NP occupied a large volume of the disc space as viewed in the HE stained midsagittal cross-sections. The NP area was stained strongly with safranin-O (I), indicating a high glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content. In the degeneration model group (B, F, J), the disc space collapsed, with evident fibrous tissue invasion. In the HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS group (C, G, K), inhomogeneous fibrous tissue was found and the NP area was stained almost negatively by safranin O. Although discs in the HP-NR4A1 pDNA/NS/NF-SMS group (D, H, L) still displayed some degree of degeneration, therapeutic efficacy was obvious as compared to the degeneration model group. The NP area in this group was more similar to the normal control group than other groups and was stained positively with safranin O. Scale bar: A-D, I-M 250μm, E-H 100μm.

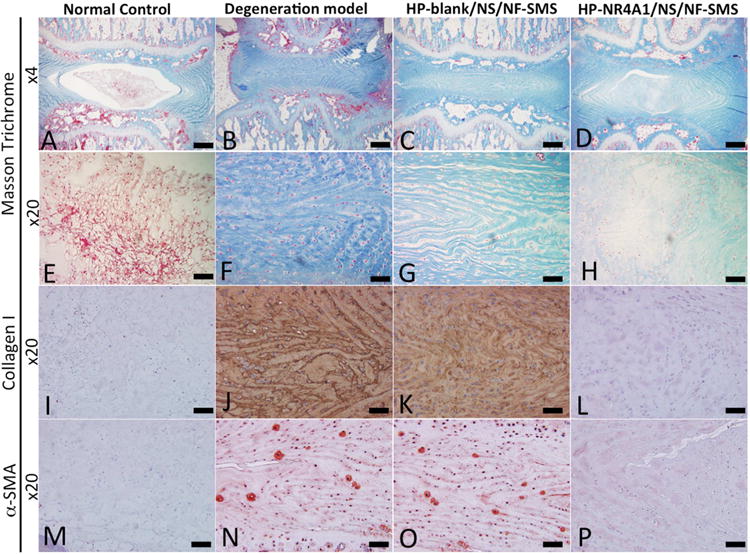

Masson's Trichrome staining for collagen in extracellular matrix, immunohistochemical staining for collagen type I and α-SMA were used to evaluate the fibrous tissue formation in vivo (Fig. 7). In the intact discs of the normal control group, the NP area was stained negative for Masson's Trichrome (collagen), type I collagen and α-SMA (Fig. 7 A, E, I, M). In the punctured group, the NP area was stained positive for Masson Trichrome, type I collagen and α-SMA (Fig. 7B, F, J, N). In the HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS group, the NP area was also stained positive for Masson Trichrome, collagen type I and α-SMA (Fig. 7C, G, K, O). In the HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS group, these fibrous tissue stains were weak (Fig. 7D, H, L, P).

Fig. 7. Masson's Trichrome (blue - collagen) and immunohistochemical staining (for collagen type I and α-SMA) to evaluate the fibrous tissue formation in vivo.

In the intact discs of the normal control group, the NP area was stained negatively for Masson Trichrome, type I collagen, and α-SMA (A, E, I, M). In the degeneration model group, the NP area was stained positively for Masson Trichrome, type I collagen, and α-SMA (B, F, J, N). A strong staining for Masson Trichrome, collagen type I, and α-SMA was observed in the HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS group (C, G, K, O). Fibrous tissue staining was weak in the HP-NR4A1 pDNA/NS/NF-SMS group (D, H, L, P). Scale bar: A-D 150μm, E-P 60μm.

To examine whether the transfected NR4A1 gene played a key role in our animal model, we tested the expression of NR4A1 using immunofluorescence microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 8). In the normal control and HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS group, a positive staining for NR4A1 was observed (Supplementary Fig. 8 A-C, J-L). While in the degeneration model and HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS groups, the immunoreactivity for NR4A1 was very weak and almost negligible (Supplementary Fig. 8 D-I). The results demonstrated that HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS delivery could restore the expression of NR4A1 in the NP tissue of this animal model.

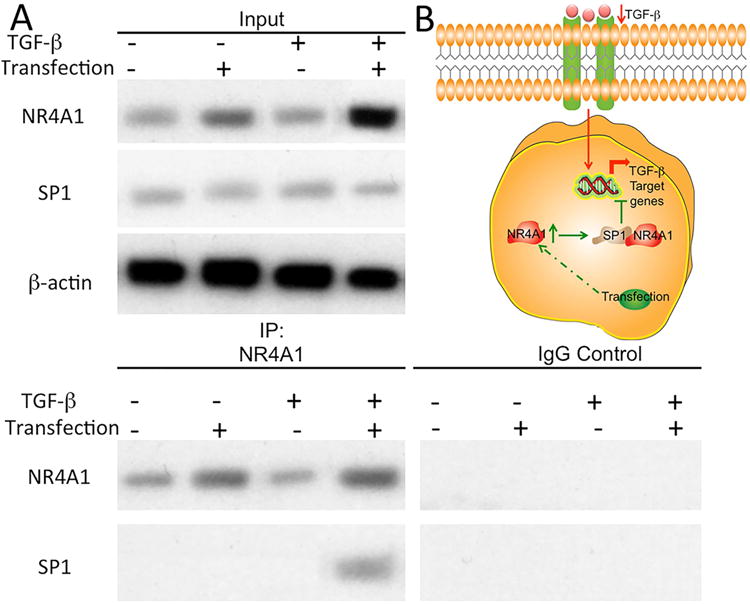

Semi-quantitative histological scores were 4.0 ± 0.0 for normal control, 9.9 ± 0.9 for degeneration model, 9.1 ± 1.3 for HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS transfected group, 6.9 ± 0.9 for HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS transfected group. Statistical analysis showed the histological scores of the HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS transfected group were significantly lower than those in the degeneration model group or HP-blank/NS/NF-SMS transfected group, indicating a significantly better regeneration outcome (p<0.01, Supplementary Fig. 10B). To explore the potential mechanisms of the reduced fibrosis after transfection, we evaluated the NR4A1-mediated regulation of TGF-β signaling. It has been reported that nuclear receptors interact with other transcriptional regulators to transiently repress gene expression [57]. NR4A1 has been shown to interact with specificity protein 1 (SP1), and SP1 signaling regulates the transcription of TGF-β target genes including type I collagen [29, 58]. Therefore, we hypothesized that NR4A1 binds to the promoters of type I collagen in the form of NR4A1-SP1 complexes to transiently repress TGF-β signaling. A CoIP assay demonstrated that TGF-β induces binding of NR4A1 to the SP1 binding site after NP cells were transfected with the NR4A1 gene (Fig. 8A). However, in NP cells without NR4A1 transfection, the NR4A1-SP1 complexes could not be detected after TGF-β induction. Therefore, the above data demonstrated that NR4A1 recruits SP1 to form complexes to inhibit the transcription of TGF-β target genes (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8. NR4A1 mediates regulation of TGF-β signaling.

Binding of NR4A1 to SP1 in human nucleus pulposus cells with/without NR4A1 transfection and TGF-β, as shown with representative western blot images (A). Scheme of the role of NR4A1 for potential mechanism (B).

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, changes in cellular phenotype, mechanical and biochemical characteristics occur during IVD degeneration, which afflicts an enormously large patient population [1]. These changes mainly include inflammation, matrix degradation, loss of proteoglycan in the NP, disorganization of the concentric lamellae in the annulus fibrosus, spinal instability, disc height loss and prolapse. These changes lead to the imbalance of the microenvironment of the disc, which may cause mechanical overloading, defective nutrient supply, cell necrosis, and NP fibrosis. Fibrosis is clinically associated with IVD degeneration. There is no effective anti-fibrosis drug to reverse this degenerative process. Gene therapy could be of potential, but there is limited knowledge on effective genes to reverse fibrosis. In addition, there are serious safety concerns over the currently effective viral vectors for possible clinical application [59, 60]. Various cationic polymers such as high molecular weight PEI have shown potential as non-viral gene delivery vectors. However, they often have significant cytotoxicity. In this work, the newly developed non-viral HP vector was found to have very high binding affinity to NR4A1 pDNA and negligible cytotoxicity, to be able to substantially reverse pathogenic fibrosis, and to facilitate NP tissue regeneration. In addition, this novel vector was very stable and could be encapsulated into biodegradable PLGA nanospheres to achieve controlled release of bioactive pDNA for a desired duration. The PLGA NS incorporating HP-pDNA polyplexes were used together with the novel NF-SMS. The released HP-pDNA polyplexes locally transfect endogenous cells to suppress fibrotic degeneration and together with NF-SMS to facilitate NP tissue regeneration. Both PLGA and PLLA are biodegradable and biocompatible polymers, and the release of the polyplexes is mainly controlled by the degradation of the PLGA nanospheres. Consistent with our hypothesis, bioluminescence-imaging results demonstrated a sustained and local gene expression profile in the HP/NS/NF-SMS system, which is in sharp contrast to the HP alone group.

Fibrosis is involved in the progression of IVD degeneration [61]. TGF-β is the major profibrogenic cytokine and mediate fibrosis in multiple organs. Insufficient signal activity of TGF-β might reduce the necessary extracellular matrix (collagen type II and aggrecan) production, while persistent or remittent TGF-β activity might result in uncontrolled activation of fibroblasts. Our approach aims to balance the regulatory feedback loop by activating NR4A1. Recent effort to neutralize TGF-β itself or inhibit the secondary messengers of TGF-β failed likely because of insufficient local presence time or off-target toxicity [62]. Our results indicated that NR4A1 induction via gene transfection could not only reduce the profibrogenic gene expression, but also repress the progression of fibrosis both in vitro and in vivo. The potent regulatory effects of NR4A1 on TGF-β signaling in the experimental model make it a promising candidate for future clinical investigation.

Using a large 3D nanofibrous scaffold, we previously regenerated NP tissue and implanted it into the caudal spine [55, 56]. The implanted tissue was found to remain in place, contain functional ECM, and maintain the disc height. However, an open surgical incision was needed for the 3D scaffold implantation and thereby increases the risk for complications. The percutaneous injection of HP-NR4A1/NS/NF-SMS into the disc is easy to carry out, less invasive, and advantageous in clinical settings. The sustained local delivery of pDNA from nanocarriers can overcome shortcomings associated with systemic drug delivery, including rapid clearance and side effects in unintended tissues [63]. The nano-scale and micro-scale structures of NF-SMS may advantageously support tissue regeneration [64-66]. On the nanometer scale, a nanofibrous architecture mimicking the structure of extracellular matrix (ECM) can promote tissue regeneration [56, 67]. A porous structure on the micrometer scale likely increases gene delivery vehicle-loading efficiency, decreases the amount of degradation product, facilitates cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, and provides easy path for nutrient and metabolic waste transfer [68-71]. Together, the above effects may have synergistically enhanced tissue regeneration and integration with the host.

A simple disc degeneration model was established using percutaneous needle puncture in current study according to literature [53]. However, there are biomechanical and anatomic differences between the rat spine and human spine. In addition, notochordal cells still exist in rats at the age selected for our study. However, it is difficult to identify notochordal cells in NP tissue because of the lack of specific markers for this cell type. Future studies using dog, goat, sheep, or nonhuman primate models may provide further insights.

NR4A1 has been shown to be effective in treating NP fibrosis in this study, which necessitates future investigation on any potential side effect of NR4A1 application. While NR4A1 is known to stimulate the expression of anti-apoptotic genes such as BIRC5, certain death signals could induce translocation of NR4A1 from the nucleus to the mitochondria, where NR4A1 converts BCL-2 into a pro-apoptotic mediator [72, 73]. Releasing NR4A1 agonists systemically could potentially induce apoptosis, resulting in off-target toxicity. NR4A1 could also stimulate lipolysis and increases energy consumption in the skeletal muscles [25], which could have adverse effects if applied systemically. The local delivery strategy of NR4A1 used in our study should be advantageous in circumventing these potential systemic complications.

To explore the mechanisms, we evaluated the NR4A1-mediated TGF-β signaling. It was demonstrated that TGF-β induces binding of NR4A1 to the SP1 binding site after NP cells were transfected with the NR4A1 gene. Therefore, we hypothesize that NR4A1 binds to the promoters of type I collagen in the form of NR4A1-SP1 complexes to transiently repress TGF-β signaling. Considering that SP1 binds COL1A1 and there are polymorphisms of COL1A1 in certain populations, the NR4A1-mediated TGF-b signaling mechanisms may need further examination in those cases.

Conclusion

While fibrotic IVD degeneration is clinically associated with chronic low back pain, there have been very limited genes identified to reverse pathogenic IVD fibrosis or facilitate IVD regeneration. In this work, we have developed an injectable two-stage gene delivery system, which contains a nanofibrous micro cell carrier and a self-assembled nano-sized polymer vector encapsulated in PLGA NS for sustained pDNA delivery into IVD cells. This novel delivery system is biodegradable and biocompatible, can release the polymer vector in a temporally controlled fashion, and is able to highly efficiently transfect IVD cells with a novel anti-fibrotic gene (NR4A1). In addition, we have shown that this delivery system can significantly reverse fibrosis and facilitate IVD regeneration in a rat caudal model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the US National Science Foundation (NSF DMR-1206575: PXM) and the National Institutes of Health (DE015384 and DE017689: PXM). GF was partially supported by a fellowship from Sichuan University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011;12:224–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou D, Samartzis D, Bellabarba C, Patel A, Luk KD, Kisser JM, Skelly AC. Degenerative magnetic resonance imaging changes in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine. 2011;36:S43–53. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822ef700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takatalo J, Karppinen J, Niinimaki J, Taimela S, Nayha S, Mutanen P, Sequeiros RB, Kyllonen E, Tervonen O. Does lumbar disc degeneration on magnetic resonance imaging associate with low back symptom severity in young Finnish adults? Spine. 2011;36:2180–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182077122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakai D, Grad S. Advancing the cellular and molecular therapy for intervertebral disc disease. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2015;84:159–71. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakai D, Andersson GB. Stem cell therapy for intervertebral disc regeneration: obstacles and solutions. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2015;11:243–56. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams MA, Dolan P. Could sudden increases in physical activity cause degeneration of intervertebral discs? Lancet. 1997;350:734–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang YC, Urban JP, Luk KD. Intervertebral disc regeneration: do nutrients lead the way? Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2014;10:561–6. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuma T, Koh S, Okamura T, Yamauchi Y. Histological changes in aging lumbar intervertebral discs. Their role in protrusions and prolapses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:220–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boos N, Weissbach S, Rohrbach H, Weiler C, Spratt KF, Nerlich AG. Classification of age-related changes in lumbar intervertebral discs: 2002 Volvo Award in basic science. Spine. 2002;27:2631–44. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng B, Chen J, Kuang Z, Li D, Pang X, Zhang X. Expression and role of connectivetissue growth factor in painful disc fibrosis and degeneration. Spine. 2009;34:E178–82. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181908ab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yee A, Lam MP, Tam V, Chan WC, Chu IK, Cheah KS, Cheung KM, Chan D. Fibrotic-like changes in degenerate human intervertebral discs revealed by quantitative proteomic analysis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Wang C, Zha Y, Hu W, Gao Z, Zang Y, Chen J, Zhang J, Dong L. Corona-directed nucleic acid delivery into hepatic stellate cells for liver fibrosis therapy. ACS nano. 2015;9:2405–19. doi: 10.1021/nn505166x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214:199–210. doi: 10.1002/path.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lovisa S, LeBleu VS, Tampe B, Sugimoto H, Vadnagara K, Carstens JL, Wu CC, Hagos Y, Burckhardt BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Nischal H, Allison JP, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induces cell cycle arrest and parenchymal damage in renal fibrosis. Nat Med. 2015;21:998–1009. doi: 10.1038/nm.3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson NC, Arnold TD, Katamura Y, Giacomini MM, Rodriguez JD, McCarty JH, Pellicoro A, Raschperger E, Betsholtz C, Ruminski PG, Griggs DW, Prinsen MJ, Maher JJ, Iredale JP, Lacy-Hulbert A, et al. Targeting of alphav integrin identifies a core molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis in several organs. Nat Med. 2013;19:1617–24. doi: 10.1038/nm.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grande MT, Sanchez-Laorden B, Lopez-Blau C, De Frutos CA, Boutet A, Arevalo M, Rowe RG, Weiss SJ, Lopez-Novoa JM, Nieto MA. Snail1-induced partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition drives renal fibrosis in mice and can be targeted to reverse established disease. Nat Med. 2015;21:989–97. doi: 10.1038/nm.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun B, Pokhrel S, Dunphy DR, Zhang H, Ji Z, Wang X, Wang M, Liao YP, Chang CH, Dong J, Li R, Madler L, Brinker CJ, Nel AE, Xia T. Reduction of Acute Inflammatory Effects of Fumed Silica Nanoparticles in the Lung by Adjusting Silanol Display through Calcination and Metal Doping. ACS nano. 2015;9:9357–72. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Duch MC, Mansukhani N, Ji Z, Liao YP, Wang M, Zhang H, Sun B, Chang CH, Li R, Lin S, Meng H, Xia T, Hersam MC, Nel AE. Use of a pro-fibrogenic mechanism-based predictive toxicological approach for tiered testing and decision analysis of carbonaceous nanomaterials. ACS nano. 2015;9:3032–43. doi: 10.1021/nn507243w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meisel HJ, Ganey T, Hutton WC, Libera J, Minkus Y, Alasevic O. Clinical experience in cell-based therapeutics: intervention and outcome. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2006;15(3):S397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0169-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tschugg A, Diepers M, Simone S, Michnacs F, Quirbach S, Strowitzki M, Meisel HJ, Thome C. A prospective randomized multicenter phase I/II clinical trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of NOVOCART disk plus autologous disk chondrocyte transplantation in the treatment of nucleotomized and degenerative lumbar disks to avoid secondary disease: safety results of Phase I-a short report. Neurosurgical review. 2017;40:155–62. doi: 10.1007/s10143-016-0781-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tschugg A, Michnacs F, Strowitzki M, Meisel HJ, Thome C. A prospective multicenter phase I/II clinical trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of NOVOCART Disc plus autologous disc chondrocyte transplantation in the treatment of nucleotomized and degenerative lumbar disc to avoid secondary disease: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:108. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1239-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massague J. TGFbeta signalling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–30. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell MA, Cleasby ME, Harding A, Stark A, Cooney GJ, Muscat GE. Nur77 regulates lipolysis in skeletal muscle cells. Evidence for cross-talk between the beta-adrenergic and an orphan nuclear hormone receptor pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12573–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pei L, Waki H, Vaitheesvaran B, Wilpitz DC, Kurland IJ, Tontonoz P. NR4A orphan nuclear receptors are transcriptional regulators of hepatic glucose metabolism. Nat Med. 2006;12:1048–55. doi: 10.1038/nm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fassett MS, Jiang W, D'Alise AM, Mathis D, Benoist C. Nuclear receptor Nr4a1 modulates both regulatory T-cell (Treg) differentiation and clonal deletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3891–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200090109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanna RN, Carlin LM, Hubbeling HG, Nackiewicz D, Green AM, Punt JA, Geissmann F, Hedrick CC. The transcription factor NR4A1 (Nur77) controls bone marrow differentiation and the survival of Ly6C- monocytes. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:778–85. doi: 10.1038/ni.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arkenbout EK, de Waard V, van Bragt M, van Achterberg TA, Grimbergen JM, Pichon B, Pannekoek H, de Vries CJ. Protective function of transcription factor TR3 orphan receptor in atherogenesis: decreased lesion formation in carotid artery ligation model in TR3 transgenic mice. Circulation. 2002;106:1530–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028811.03056.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palumbo-Zerr K, Zerr P, Distler A, Fliehr J, Mancuso R, Huang J, Mielenz D, Tomcik M, Furnrohr BG, Scholtysek C, Dees C, Beyer C, Kronke G, Metzger D, Distler O, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor NR4A1 regulates transforming growth factor-beta signaling and fibrosis. Nat Med. 2015;21:150–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangraviti A, Tzeng SY, Kozielski KL, Wang Y, Jin Y, Gullotti D, Pedone M, Buaron N, Liu A, Wilson DR, Hansen SK, Rodriguez FJ, Gao GD, DiMeco F, Brem H, et al. Polymeric nanoparticles for nonviral gene therapy extend brain tumor survival in vivo. ACS nano. 2015;9:1236–49. doi: 10.1021/nn504905q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mastrobattista E, Hennink WE. Polymers for gene delivery: Charged for success. Nature materials. 2012;11:10–2. doi: 10.1038/nmat3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin H, Kanasty RL, Eltoukhy AA, Vegas AJ, Dorkin JR, Anderson DG. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nature reviews Genetics. 2014;15:541–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez EJ, Gerhardt K, Judd J, Tabor JJ, Suh J. Light-Activated Nuclear Translocation of Adeno-Associated Virus Nanoparticles Using Phytochrome B for Enhanced, Tunable, and Spatially Programmable Gene Delivery. ACS nano. 2016;10:225–37. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han L, Kong DK, Zheng MQ, Murikinati S, Ma C, Yuan P, Li L, Tian D, Cai Q, Ye C, Holden D, Park JH, Gao X, Thomas JL, Grutzendler J, et al. Increased Nanoparticle Delivery to Brain Tumors by Autocatalytic Priming for Improved Treatment and Imaging. ACS nano. 2016;10:4209–18. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He H, Zheng N, Song Z, Kim KH, Yao C, Zhang R, Zhang C, Huang Y, Uckun FM, Cheng J, Zhang Y, Yin L. Suppression of Hepatic Inflammation via Systemic siRNA Delivery by Membrane-Disruptive and Endosomolytic Helical Polypeptide Hybrid Nanoparticles. ACS nano. 2016;10:1859–70. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishida K, Doita M, Takada T, Kakutani K, Miyamoto H, Shimomura T, Maeno K, Kurosaka M. Sustained transgene expression in intervertebral disc cells in vivo mediated by microbubble-enhanced ultrasound gene therapy. Spine. 2006;31:1415–9. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000219945.70675.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levicoff EA, Kim JS, Sobajima S, Wallach CJ, Larson JW, 3rd, Robbins PD, Xiao X, Juan L, Vadala G, Gilbertson LG, Kang JD. Safety assessment of intradiscal gene therapy II: effect of dosing and vector choice. Spine. 2008;33:1509–16. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318178866c. discussion 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leckie SK, Bechara BP, Hartman RA, Sowa GA, Woods BI, Coelho JP, Witt WT, Dong QD, Bowman BW, Bell KM, Vo NV, Wang B, Kang JD. Injection of AAV2-BMP2 and AAV2-TIMP1 into the nucleus pulposus slows the course of intervertebral disc degeneration in an in vivo rabbit model. The Spine Journal : Oficial Journal of the North American Spine Society. 2012;12:7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudo H, Minami A. Caspase 3 as a therapeutic target for regulation of intervertebral disc degeneration in rabbits. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1648–57. doi: 10.1002/art.30251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramishetti S, Kedmi R, Goldsmith M, Leonard F, Sprague AG, Godin B, Gozin M, Cullis PR, Dykxhoorn DM, Peer D. Systemic Gene Silencing in Primary T Lymphocytes Using Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles. ACS nano. 2015;9:6706–16. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rychahou P, Haque F, Shu Y, Zaytseva Y, Weiss HL, Lee EY, Mustain W, Valentino J, Guo P, Evers BM. Delivery of RNA nanoparticles into colorectal cancer metastases following systemic administration. ACS nano. 2015;9:1108–16. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tiram G, Segal E, Krivitsky A, Shreberk-Hassidim R, Ferber S, Ofek P, Udagawa T, Edry L, Shomron N, Roniger M, Kerem B, Shaked Y, Aviel-Ronen S, Barshack I, Calderon M, et al. Identification of Dormancy-Associated MicroRNAs for the Design of Osteosarcoma-Targeted Dendritic Polyglycerol Nanopolyplexes. ACS nano. 2016;10:2028–45. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b06189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pack DW, Hoffman AS, Pun S, Stayton PS. Design and development of polymers for gene delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:581–93. doi: 10.1038/nrd1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakizawa Y, Kataoka K. Block copolymer micelles for delivery of gene and related compounds. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2002;54:203–22. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samal SK, Dash M, Van Vlierberghe S, Kaplan DL, Chiellini E, van Blitterswijk C, Moroni L, Dubruel P. Cationic polymers and their therapeutic potential. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:7147–94. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35094g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitragotri S, Anderson DG, Chen X, Chow EK, Ho D, Kabanov AV, Karp JM, Kataoka K, Mirkin CA, Petrosko SH, Shi J, Stevens MM, Sun S, Teoh S, Venkatraman SS, et al. Accelerating the Translation of Nanomaterials in Biomedicine. ACS nano. 2015;9:6644–54. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Li Y, Chen YE, Chen J, Ma PX. Cell-free 3D scaffold with two-stage delivery of miRNA-26a to regenerate critical-sized bone defects. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10376. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaps L, Nuhn L, Aslam M, Brose A, Foerster F, Rosigkeit S, Renz P, Heck R, Kim YO, Lieberwirth I, Schuppan D, Zentel R. In Vivo Gene-Silencing in Fibrotic Liver by siRNA-Loaded Cationic Nanohydrogel Particles. Advanced healthcare materials. 2015 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siegman S, Truong NF, Segura T. Encapsulation of PEGylated low-molecular-weight PEI polyplexes in hyaluronic acid hydrogels reduces aggregation. Acta biomaterialia. 2015;28:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Putnam D. Polymers for gene delivery across length scales. Nature materials. 2006;5:439–51. doi: 10.1038/nmat1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei G, Jin Q, Giannobile WV, Ma PX. The enhancement of osteogenesis by nano-fibrous scaffolds incorporating rhBMP-7 nanospheres. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2087–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gruber HE, Hoelscher GL, Leslie K, Ingram JA, Hanley EN., Jr Three-dimensional culture of human disc cells within agarose or a collagen sponge: assessment of proteoglycan production. Biomaterials. 2006;27:371–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu MH, Yang KC, Chen YJ, Sun YH, Yang SH. Lovastatin prevents discography-associated degeneration and maintains the functional morphology of intervertebral discs. The Spine Journal : Oficial Journal of the North American Spine Society. 2014;14:2459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masuda K, Aota Y, Muehleman C, Imai Y, Okuma M, Thonar EJ, Andersson GB, An HS. A novel rabbit model of mild, reproducible disc degeneration by an anulus needle puncture: correlation between the degree of disc injury and radiological and histological appearances of disc degeneration. Spine. 2005;30:5–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000148152.04401.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feng G, Jin X, Hu J, Ma H, Gupte MJ, Liu H, Ma PX. Effects of hypoxias and scaffold architecture on rabbit mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards a nucleus pulposus-like phenotype. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8182–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng G, Zhang Z, Jin X, Hu J, Gupte MJ, Holzwarth JM, Ma PX. Regenerating nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc using biodegradable nanofibrous polymer scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:2231–8. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pascual G, Glass CK. Nuclear receptors versus inflammation: mechanisms of transrepression. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2006;17:321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee SO, Abdelrahim M, Yoon K, Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Kim K, Wang H, Safe S. Inactivation of the orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth. Cancer research. 2010;70:6824–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Itaka K, Ishii T, Hasegawa Y, Kataoka K. Biodegradable polyamino acid-based polycations as safe and effective gene carrier minimizing cumulative toxicity. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3707–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen Q, Osada K, Ishii T, Oba M, Uchida S, Tockary TA, Endo T, Ge Z, Kinoh H, Kano MR, Itaka K, Kataoka K. Homo-catiomer integration into PEGylated polyplex micelle from block-catiomer for systemic anti-angiogenic gene therapy for fibrotic pancreatic tumors. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4722–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leung VY, Aladin DM, Lv F, Tam V, Sun Y, Lau RY, Hung SC, Ngan AH, Tang B, Lim CT, Wu EX, Luk KD, Lu WW, Masuda K, Chan D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reduce intervertebral disc fibrosis and facilitate repair. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2164–77. doi: 10.1002/stem.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beyer C, Distler JH. Tyrosine kinase signaling in fibrotic disorders: Translation of basic research to human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashley CE, Carnes EC, Phillips GK, Padilla D, Durfee PN, Brown PA, Hanna TN, Liu J, Phillips B, Carter MB, Carroll NJ, Jiang X, Dunphy DR, Willman CL, Petsev DN, et al. The targeted delivery of multicomponent cargos to cancer cells by nanoporous particle-supported lipid bilayers. Nature materials. 2011;10:389–97. doi: 10.1038/nmat2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuang R, Zhang Z, Jin X, Hu J, Shi S, Ni L, Ma PX. Nanofibrous spongy microspheres for the delivery of hypoxia-primed human dental pulp stem cells to regenerate vascularized dental pulp. Acta biomaterialia. 2016;33:225–34. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Z, Gupte MJ, Jin X, Ma PX. Injectable Peptide Decorated Functional Nanofibrous Hollow Microspheres to Direct Stem Cell Differentiation and Tissue Regeneration. Advanced functional materials. 2015;25:350–60. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201402618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuang R, Zhang Z, Jin X, Hu J, Gupte MJ, Ni L, Ma PX. Nanofibrous spongy microspheres enhance odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. Advanced healthcare materials. 2015;4:1993–2000. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ma PX. Biomimetic materials for tissue engineering. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2008;60:184–98. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Z, Gupte MJ, Ma PX. Biomaterials and stem cells for tissue engineering. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2013;13:527–40. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2013.756468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Z, Hu J, Ma PX. Nanofiber-based delivery of bioactive agents and stem cells to bone sites. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012;64:1129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holzwarth JM, Ma PX. Biomimetic nanofibrous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9622–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu X, Jin X, Ma PX. Nanofibrous hollow microspheres self-assembled from star-shaped polymers as injectable cell carriers for knee repair. Nature materials. 2011;10:398–406. doi: 10.1038/nmat2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin B, Kolluri SK, Lin F, Liu W, Han YH, Cao X, Dawson MI, Reed JC, Zhang XK. Conversion of Bcl-2 from protector to killer by interaction with nuclear orphan receptor Nur77/TR3. Cell. 2004;116:527–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thompson J, Winoto A. During negative selection, Nur77 family proteins translocate to mitochondria where they associate with Bcl-2 and expose its proapoptotic BH3 domain. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1029–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.