Significance

Individuals differ in the degree to which they endorse group-based hierarchies in which some social groups dominate others. Much research demonstrates that among individuals this preference robustly predicts ideologies and behaviors enhancing and sustaining social hierarchies (e.g., racism, sexism, and prejudice). Combining aggregate archival data from 27 countries (n = 41,824) and multilevel data from 30 US states (n = 4,613) with macro-level indicators, we demonstrate that the degree of structural inequality, social instability, and violence in different countries and US states is reflected in their populations’ minds in the form of support of group-based hegemony. This support, in turn, increases individual endorsement of ideologies and behaviors that ultimately sustain group-based inequality, such as the ethnic persecution of immigrants.

Keywords: social dominance, multi-level mediation, social inequality, racism, ethnic persecution

Abstract

Whether and how societal structures shape individual psychology is a foundational question of the social sciences. Combining insights from evolutionary biology, economy, and the political and psychological sciences, we identify a central psychological process that functions to sustain group-based hierarchies in human societies. In study 1, we demonstrate that macrolevel structural inequality, impaired population outcomes, socio-political instability, and the risk of violence are reflected in the endorsement of group hegemony at the aggregate population level across 27 countries (n = 41,824): The greater the national inequality, the greater is the endorsement of between-group hierarchy within the population. Using multilevel analyses in study 2, we demonstrate that these psychological group-dominance motives mediate the effects of macrolevel functioning on individual-level attitudes and behaviors. Specifically, across 30 US states (n = 4,613), macrolevel inequality and violence were associated with greater individual-level support of group hegemony. Crucially, this individual-level support, rather than cultural-societal norms, was in turn uniquely associated with greater racism, sexism, welfare opposition, and even willingness to enforce group hegemony violently by participating in ethnic persecution of subordinate out-groups. These findings suggest that societal inequality is reflected in people’s minds as dominance motives that underpin ideologies and actions that ultimately sustain group-based hierarchy.

Whether and how the structure of society shapes the individual mind is a foundational question of the social sciences (1–3). In particular, the central observation that the position of individuals and their groups within societal structure has large impacts on their mindset has influenced the understanding of human behavior (4–8). Social hierarchies are ubiquitous across animal species (9–11) and human cultures (12–14), so that higher-ranked individuals enjoy privileged access to resources, territory, mates, and ultimately greater reproductive success. However, conflicts as to who should receive such privileged access to resources are costly and potentially lethal. Hence, game theoretic simulations suggest that, generally speaking, it is adaptive for the involved parties to coordinate by submitting to more formidable opponents they are unlikely to defeat (15, 16). Observations of animal fighting and fights among human toddlers bear out these predictions (17, 18): Dominant and formidable animals tend to fight challengers aggressively, but subordinate and less formidable ones tend to yield. Indeed, even preverbal infants use the formidability cues of body and group size, together with the previous win–lose history of the parties, to predict the outcome of dominance contests (19–21). Animals also will fight harder for the resources/territory they already possess (22) and appear hesitant to challenge others’ home-turf commitments (15, 23). Hence, equilibria of relatively stable dominance hierarchies that reduce costly fights can be observed across species, although in general the greater the stakes, the greater is the risk of violent conflicts.

The game theoretic logic of such dominance dynamics may scale to intergroup conflicts that also have deep evolutionary roots (24, 25). For instance, groups of lions and chimpanzees engage in intergroup killing of weaker/smaller outgroups, resulting in territorial expansion, and subsequent increased group and average body size, and reproductive gain (26–29). Archaeological, historical, and ethnographic records also indicate widespread intergroup warfare and violence between human groups, from bands of hunter-gatherers to complex societies (9, 24, 30–33). Again, whether seeking to uphold or challenge a group hegemony is adaptive should depend on how likely one’s group is to succeed, that is, on its fighting ability or power in terms of strength, size, and commitment/loyalty, including preexisting resource possession. Together, these forces should result in overall equilibria of relatively stable dominance hierarchies between groups, so that, all else being equal, dominant groups should be relatively more likely to fight challenges to their privileged position violently, and subordinate groups should be relatively more unlikely to challenge the hegemonic status quo unless their perceived fighting ability or power indicate their likely success. Consistent with this prediction, every known surplus-producing human society is indeed characterized by some degree of relatively stable hegemony between groups, in which dominant groups hold more resources, status, and better prospects in life than do subordinate groups (24). This pattern can be observed both in blatantly unequal societies and in countries with strong egalitarian traditions: The caste system in India presents a rather blatant example of group hegemony, but even in the supposedly egalitarian Nordic countries some groups (e.g., native-born citizens) hold drastically higher status than others (e.g., Roma immigrants).

The greater the inequality of resources and power, the greater level of political unaccountability, corruption, and lack of democracy and rule of law we expect, because these phenomena precisely signal and enforce that the lion’s share of resources goes to the dominant group by virtue of its power and greater formidability. Greater inequality also should increase the stakes involved in conflicts over status and resources and hence should increase both the motivation of subordinate groups to challenge their lot insofar as they perceive a chance of succeeding (34) and the propensity of dominant groups to defend the resources and power they already possess. Together, these factors should increase the risk of violent conflicts. The empirical literature bears out the general prediction that economic inequality within a country (which tends to be stratified between societal groups) impairs the socio-political functioning of the country in this manner (35, 36). Furthermore, in the most extreme cases, historical records of the justification of genocide often evoke the perception of potential victimization of dominant groups, i.e., that subordinates threaten the dominant group’s position (37).

Both societal/normative and individual-level/psychological processes may potentially account for the stabilization of varying degrees of group hegemony across human societies. A societal, normative route would posit that societal norms emerge as adaptive coordinated solutions to macrolevel challenges and stressors and exert normative pressure on individual-level behavior and attitudes (38). For instance, collective norms of social cohesion and conventionality vary with ecological stressors such as population density, territorial threat, resource scarcity, and parasite load and arguably developed in response to such stressors, motivating individual-level self-regulation (39). Also, aggregate levels of contact between societal groups have been demonstrated to reduce outgroup prejudice over and above individual contact experiences, presumably because they change societal norms for intergroup attitudes (40). Similarly, societal norms for group hegemony might reflect ecological conditions and may enforce and sanction the domination and submission of subordinate groups, over and above individual experiences and motives. However, it is individuals who ultimately must bear the costs of fighting/challenging/dominating or yielding/defecting/submitting in conflicts between groups. Consequently, in making these decisions individuals should be tuned to the power, relative formidability, and existing resource possession of their group, i.e., to their group’s likely victory or defeat in intergroup conflicts. Insofar as psychological motives function to facilitate adaptive behavior, such relational tuning may happen through general individual-level psychological dominance motives for group hegemony. The resulting greater hegemonic endorsement among members of dominant groups should, in turn, increase their legitimization of and willingness to participate in violently enforcing the hegemonic status quo, especially when challenged (24, 41–43). Hence, we posit that the effects of macrostructural inequality occur at least in part via psychological processes at the individual level, so that people’s motives for group hegemony reflect the strength, power, and resources of their group, propelling them to justify and enforce the hegemonic status quo.

Consistent with this proposal, much previous research has demonstrated that, ceteris paribus, people’s general, motivated preference for between-group hierarchy, their social dominance orientation (SDO) (44), is higher among the dominant groups that benefit the most from a group hegemony. Indeed, these between-group differences in SDO track actual and perceived status differences between groups (24, 45, 46). Ceteris paribus, SDO correlates with support for a great variety of specific hierarchy-enhancing practices and institutions (e.g., over-policing of subordinate communities by particularly lethal means), restrictive and punitive policies, and ideologies (e.g., laissez-faire liberalism) that sustain and legitimize group domination and inequality. Indeed, SDO robustly predicts the endorsement of hierarchy-enhancing and hierarchy-justifying intergroup attitudes such as racism, sexism, and support for harsher criminal sentences for minority offenders and the disapproval of hierarchy-attenuating ideologies and redistributive policies such as social welfare, civil rights, and multiculturalism (24, 47, 48). The effects of SDO extend across time and contexts (49, 50) and deep into psychological processes such as empathy, implicit bias and social categorization, disgust, dehumanization, and persistent psychophysiological fight-or-flight responses toward outgroup males that pose the greatest danger of violent dominance conflicts (51–56). Finally, SDO selectively predicts willingness to participate in ethnic persecution, especially when established dominance boundaries are threatened by members of subordinate groups (57), supporting the notion that intergroup violence serves to enforce coalitional dominance.

Previously demonstrated motives for thinking that the world is just (43) and for justifying the extant societal system (41, 42, 58), as reflected in the endorsement of the hierarchical status quo, are congruent with the interests of members of dominant groups (58). Moreover, the game-strategic dynamics of dominance suggest that even members of disadvantaged groups may be better off accepting a dominance hierarchy they are unlikely to overturn. Consistent with this notion, research on system justification suggests that even those disadvantaged by the societal system often tend to justify it, but that this tendency is moderated by their sense of power (34).

In summary, we posit that group-based hegemony is continuously reproduced through the interaction of psychological hegemonic motives (as captured by SDO) with societal structure (24). Previous research supports an interaction between individual-level ideologies, such as sexism or conformity, and societal-level characteristics (39, 59, 60). Some evidence also suggests that gender empowerment, higher gross domestic product, and democracy relate to lower national-level SDO (61, 62) and that the effects of SDO on prejudice toward immigrants depend on the relative differences in status between native and immigrant groups (63). However, the psychological process that connects structural inequality with the ideology and prejudice of individuals remains uncertain. Here, we test (i) if SDO tracks macrolevel inequality and violence and (ii) if such structural inequality and instability result in racism, sexism, opposition to social welfare, and support for violent ethnic persecution of immigrants among members of dominant groups, precisely because of the ways in which structural inequality relates to the motives for between-group dominance among individuals.

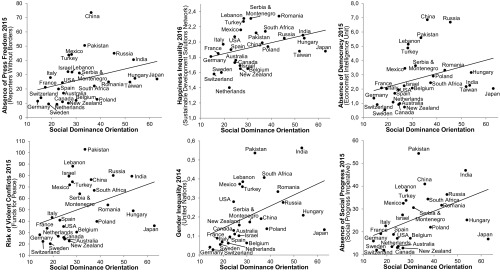

Study 1

We first pooled aggregate SDO meta-analytic data (n = 41,824 members of dominant societal groups) from 27 countries collected between 1996 and 2009 with global macroindices provided by organizations such as the United Nations and World Bank. We predicted that average, country-level SDO would track national-level (i) risk of violent conflicts, (ii) absence of governance, (iii) absence of social progress, (iv) absence of democracy, (v) absence of press freedom, (vi) gender inequality, and (vii) happiness inequality (see Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, Text S1 and Table S1 for details). Indeed, countries with relatively high levels of SDO generally fared worse on these indices than those with low levels of SDO (Fig. 1 and Table 1). If anything, the effects were stronger when multivariate outliers were excluded (SI Appendix, Text S2 and Tables S2 and S3). These results suggest that structural societal inequality and the violent conflict and impaired governance that it renders are reflected in people’s minds as a general relational tuning of their motivation for group dominance.

Fig. 1.

Country population scores on SDO consistently track country scores on socio-political indices in study 1.

Table 1.

Correlations between country-level social dominance and socio-political indices in study 1

| Index | r | P | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Risk of violent conflicts | 0.38 | 0.014 | 0.076 | 0.689 |

| Absence of governance | 0.35 | 0.043 | 0.014 | 0.678 |

| Absence of social progress | 0.44 | 0.008 | 0.110 | 0.774 |

| Absence of democracy | 0.34 | 0.011 | 0.086 | 0.632 |

| Absence of press freedom | 0.34 | 0.006 | 0.131 | 0.585 |

| Gender inequality | 0.46 | 0.007 | 0.140 | 0.777 |

| Happiness inequality | 0.37 | 0.009 | 0.118 | 0.606 |

Two-tailed P values and 95% CIs are based on bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples.

Table 2.

Testing individual psychological vs. state normative SDO mediation effects on individual-level hierarchy-enhancing attitudes and behaviors in study 2

| Predictors/dependent variables | Context effects → SDO (a) | SDO → hierarchy-enhancing attitudes and behaviors (b) | Indirect effects (a*b) | Unmediated effects (context → hierarchy-enhancing attitudes and behaviors) (c′) |

| State-level predictor: Economic inequality (Gini) | ||||

| Individual-level process | ||||

| Economic inequality (cross-level effect) | 3.47** | |||

| Ethnic persecution | 0.58** | 2.02** | 2.81 | |

| Blatant racism | 0.78** | 2.72** | 0.99 | |

| Welfare opposition | 1.22** | 4.21** | 0.30 | |

| Hostile sexism | 0.90** | 3.10** | 4.82* | |

| Benevolent sexism | 0.64** | 2.22** | −0.13 | |

| State (cross)-level processes | ||||

| Economic inequality (state level) | 3.47** | |||

| Ethnic persecution | 0.55 | 1.37 | 2.81 | |

| Blatant racism | 0.83* | 1.64 | 0.99 | |

| Welfare opposition | 1.24 | 4.30 | 0.30 | |

| Hostile sexism | 0.76 | 2.64 | 4.82* | |

| Benevolent sexism | 1.27* | 4.41 | −0.13 | |

| State-level predictor: Presence of violence (US Peace Index) | ||||

| Individual-level process | ||||

| Presence of violence (cross-level effect) | 0.09* | |||

| Ethnic persecution | 0.58** | 0.05* | 0.07 | |

| Hostile sexism | 0.78** | 0.07* | 0.06 | |

| Benevolent sexism | 1.21** | 0.11* | 0.12 | |

| Welfare opposition | 0.90** | 0.08* | 0.11 | |

| Blatant racism | 0.64** | 0.06* | 0.21** | |

| State-level processes | ||||

| Presence of violence (state level) | 0.09* | |||

| Ethnic persecution | 0.55* | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

| Hostile sexism | 0.76* | 0.07 | 0.06 | |

| Benevolent sexism | 0.98* | 0.09 | 0.12 | |

| Welfare opposition | 0.79* | 0.07 | 0.11 | |

| Blatant racism | 0.85* | 0.07 | 0.21** | |

Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Study 2

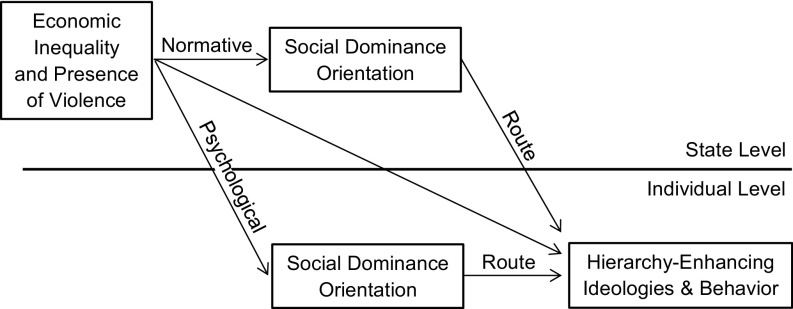

Next, we tested the prediction that macrolevel economic inequality and the presence of violence affect psychological motivations for group hegemony among individual members of the majority group and that these motivations, in turn, increase their personal justification of and willingness to enforce group hegemony. Hence, we predicted that differences in macrostructural inequality and the presence of violence among US states (as captured by Gini and the US Peace Index) would have indirect effects, as mediated by individual-level SDO,* making individual white Americans more racist and sexist, more opposed to social welfare, and even more willing to enforce group hegemony violently by personally participating in ethnic persecution. Because structural inequality and the presence of violence in principle may also affect these variables through general, emergent, collective norms that follow and perpetuate societal inequality, we directly compared a psychological route with a normative route. Specifically, we tested whether the effects of structural inequality and presence of violence (level 2) on individual-level racism, sexism, opposition to welfare, and ethnic persecution (level 1) are mediated by between-state (level 2) or individual (level 1) variation in SDO. To do so, we estimated a 2-(2,1)-1 multilevel mediation model (64) that allowed us to test these different routes within a single model (Fig. 2).†

Fig. 2.

The conceptual multilevel model tested in study 2 is displayed.

There was strong consensus about SDO, with the agreement index rwgj exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 (65) in all states (SI Appendix, Table S4). This consensus strongly suggested a normative character of SDO within each of the US states sampled and allowed us to test the separate effects of SDO at between-state and individual levels. The contextual predictors (i.e., the presence of violence and economic inequality) were entered as exogenous variables at level 2. The relative effects on the outcome variables at level 1 via normative SDO at the state level (level 2) and psychological SDO at the individual level (level 1) were estimated, allowing us to test whether SDO processes operate at the individual, psychological level or capture normative pressures at the state level. Variance decomposition showed that 1% of the variance in SDO and between 1.1% (blatant racism and hostile sexism) and 1.6% (ethnic persecution) of the variance in dependent variables varied among US states (Mσ2 = 1.3%). When we compared individual- vs. state-level processes, SDO at the individual level, but not at the state level, significantly mediated the effects of both the presence of violence and economic inequality on all dependent variables (all Ps < 0.01). In fact, individual-level variation of SDO fully mediated the effects of state-level inequality and violence on individual-level hierarchy-enhancing attitudes and behaviors, except for partial direct effects of economic inequality on hostile sexism (P < 0.05) and of the presence of violence on blatant racism (P < 0.01). Hence, overall, individual-level SDO effectively accounted for most of the variance in state-level context effects on racism, sexism, opposition to social welfare, and ethnic persecution of immigrants among white Americans. Both models showed good fit [χ2Economic Inequality(7, n = 4,613) = 47.27, P < 0.001, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.035, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.99; χ2Violence (7, n = 4,613) = 47.87, P < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = 0.99] and clearly outperformed the poorly fitting models that resulted from reversing the implied causality [χ2Economic Inequality (25, n = 4,613) = 4,771.41, P < 0.0001, RMSEA = 0.203, CFI = 0.34; χ2Violence (25, n = 4,613) = 6,156.19, P < 0.0001, RMSEA = 0.231, CFI = 0.16]. These results suggest that increased structural economic inequality and its accompanying presence of violence may increase dominance motives and willingness to enforce group hegemony among individual members of the dominant groups from which our participants were sampled.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that across countries the average hegemonic motives among members of the dominant group track macroindices of the impaired population outcomes accompanying structural inequality: a lack of social progress to meet the basic needs of the general population, greater disparities in happiness between different groups and in opportunities between genders, the absence of democracy and press freedom, as well as the risk of violent conflicts and poor governance (corruption, instability, and the absence of rule of law). In the face of such dire population outcomes (35, 36), why is the motivation for hegemony among the dominant group not reduced, but enhanced? We posit that members of dominant groups respond to cues of social inequality with increased dominance motives because they indicate better individual pay-off and chances of success. Data collected across US states in study 2 confirm that this tuning of dominance motives to macrostructural inequality and presence of violence, as well as its subsequent effects on willingness to enforce the hegemonic status quo violently, do indeed happen at the psychological level of individual agents.

Collective-level effects of social climate may still occur across countries with greater normative variation than is the case within the US. The present results, however, demonstrate that a psychological route operates through the hegemonic motives of individuals. Our multilevel analyses found evidence of indirect cross-level effects for all five of the dependent variables, and statistical models that assumed macrolevel variables to have downstream effects via SDO on individual-level attitudes and behaviors clearly outperformed models of reversed causality. Still, the cross-sectional nature of our data mandates caution in interpreting causal direction. Indeed scores of previous studies demonstrate that SDO both responds to and bolsters group dominance (24, 47, 48), suggesting that reciprocal causal processes may also operate with respect to macrostructural inequality, reproducing the hegemonic status quo.

Why, then, is rebellion by subordinate groups not more common in the face of rapidly increasing inequality across the world (66)? Our present data were comprised of responses from members of dominant groups only and so cannot address this question empirically. As is the case for individual agents, however, even though subordinate groups are placed at considerable disadvantage in a between-group hierarchy, both dominant and subordinate groups benefit from avoiding costly dominance conflicts when the outcome is likely given beforehand (67). Hence, if challenging the hegemonic status quo is costly and unlikely to be successful, individual members of subordinate groups may do better by accepting and not disputing their lot, as psychological experiments on system justification confirm (34, 58).

To conclude, the present research demonstrates that people’s preferences for group-based social hierarchies are reflected in institutional functioning and national character and hence have important social and political implications for both micro- and macrolevel analyses. The data suggest that societal-level group-based hierarchies and the consequent socio-political inequality and impaired socio-political functioning and population outcomes extend to and are reflected in the minds of national populations through basic preferences for group-based hegemony. This general preference for group hegemony in turn motivates ideologies, behaviors, and even greater support for outgroup violence that stabilizes the societal status quo.

Materials and Methods

Study 1.

For study 1 we pooled SDO data with various publicly available indices.

Aggregated SDO.

Aggregate mean SDO values for majority-group members in all 27 countries that were part of the most recent and comprehensive meta-analysis of SDO (61) were included in this research. The meta-analysis used 156 samples collected and/or published between 1996 and 2009 with a total of 41,824 participants. In all these samples, SDO was measured with the original or adapted versions of the SDO6 scale (44), asking participants to indicate their agreement with items such as “It’s probably a good thing that certain groups are at the top and other groups are at the bottom” or “Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups,” typically rated on Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). To increase comparability between countries, we used percent of maximum possible (POMP)-transformed country means (see ref. 68) for which 0 represented the smallest possible and 100 represented the highest possible SDO value.

State-level indices.

Details, selection criteria, and references for the indices and databases can be found in SI Appendix, Text S1 and Table S1. The latest 2014 data from the World Bank were used to measure absence of governance. Risk of violent conflicts was measured through the most recent Fragile States Index 2015 provided by the nonprofit organization Funds for Peace. Absence of democracy was measured through the most recent 2015 Democracy Index provided by the Economist Intelligence Unit. Absence of press freedom was measured by the 2015 Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders. Happiness inequality was measured by data provided in the 2016 World Happiness Report. Gender inequality was measured by the most recent 2014 Gender Inequality Index provided by the United Nations Development Program. Absence of social progress was measured through the 2015 Social Progress Index provided by the Social Progress Imperative.

Analyses.

We used bootstrapping (69) with 5,000 resamples to obtain CIs and P values for the correlations between SDO and scores on the socio-political indices. This procedure was chosen because it is a highly reliable and extensively validated analysis in small samples and when the actual underlying distribution in the population is unknown (70). Because only combined SDO data were available for Serbia and Montenegro in the meta-analysis, the mean scores of these two countries on the state-level indices were used.

Study 2.

Participants and procedure.

We used the Amazon MTurk panel to recruit participants. This method is frequently used in social scientific research and constitutes a fast and effective way to obtain reliable data (71). We recruited participants from all 50 US states between July and October 2015, with the goal of recruiting at least 100 white majority participants per state, thereby keeping the relative margin of error of the estimates ≤10% at a confidence level of 95%. We succeeded in recruiting participants satisfying this inclusion criterion from 30 states (see SI Appendix, Table S4 for state-related demographics). All panel participants received $0.50 as compensation for participation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the standards of the American Psychological Association. The study was approved by the Internal Ethics Committee (Nr. 1726788) of the Department of Psychology of the University of Oslo.

Presence of violence.

We used the 2012 US Peace Index (72) provided by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) to index a US state’s socio-political functioning because it comes very close to the indices used in study 1. The IEP defines peace as “the absence of violence” and measures this metric through five subindicators (α = 0.71): (i) the number of homicides, (ii) the number of violent crimes, (iii) the number of police employees, (iv) the incarceration rate per 100,000 people, and (v) the availability of small arms. On the composite index, 1 represented the presence of peace, and 5 represented the presence of violence (see ref. 72 for the scoring procedure).

Gini coefficients for US states.

The most recent (2014) US Gini coefficients were obtained through the US Census Fact Finder (73).

SDO.

SDO was measured with the original 16-item SDO6 scale (44) as in study 1. As were all the remaining measures, responses were scored on Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The scale was highly reliable across states (SI Appendix, Table S4).

Ethnic persecution.

We used a four-item version of the Posse Scale (57) to measure participants’ willingness to engage in ethnic persecution (α = 0.92) by presenting the following scenario:

“Now suppose that the government some time in the future passed a law outlawing immigrant organizations in your country. Government officials then stated that the law would only be effective if it were vigorously enforced at the local level and appealed to every citizen to aid in the fight against these organizations.”

Next, participants indicated agreement or disagreement with the items “I would tell my friends and neighbors that it was a good law”; “If asked by the police, I would help hunt down and arrest members of immigrant organizations”; “I would support physical force to make members of immigrant organizations reveal the identity of other members”; and “I would support the execution of leaders of immigrant organizations if the government insisted it was necessary to protect our country.”

Hostile and benevolent sexism.

Five items from the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (74) measured hostile and benevolent sexism. Specifically, two items measured participants’ degree of hostile sexism (i.e., “Women seek power by gaining control over men” and “Once a man commits, she puts him on a tight leash,” r = 0.79, P < 0.001), and three items measured benevolent sexism (i.e., “Women should be cherished and protected by men,” “Women have a quality of purity few men possess,” and “Despite accomplishment, men are incomplete without women,” α = 0.78).

Welfare opposition.

Opposition to social welfare was measured with the statements “We should increase the amount received by social welfare recipients” and “The state should get better at helping people on social welfare” (r = 0.74, P < 0.001). Responses were reverse-scored so that higher values meant more opposition.

Blatant anti-black racism.

The items “Blacks are inherently inferior” and “African Americans are less intellectually able than other groups,” adopted from existing scales (24, 44), measured participants’ degree of blatant racism (r = 0.87, P < 0.001).

Analyses.

Multilevel path-modeling with cross-level paths (64) was conducted using MPlus 7.31 (75). All variables were centered around the grand mean to allow a simultaneous test of the two different routes (64, 76). See SI Appendix, Text S3 for the syntax used to estimate the models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the two anonymous reviewers and Drs. Karthik Panchanathan, Keenan Pituch, and Lasse Laustsen for their helpful comments and advice. This work was funded by Fulbright and University of Oslo stipends (to J.R.K.) and by Early Career Research Group Leader Awards 0602-01839B from the Danish Research Council and 231157/F10 from the Norwegian Research Council (to L.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*When using the term “individual-level,” we always refer to the total variation in the dataset (which includes variation both within and across states) following Pituch and Stapleton (64).

†In contrast to the overall conceptual model depicted in Fig. 2, individual-level ideological beliefs and behaviors were treated as separate independent variables, allowing us to estimate unique between-state and individual-level effects on each of them simultaneously. Furthermore, this series of analyses was run in two separate models with either macro-level presence of violence or economic inequality as predictor (Table 2), because of their moderate intercorrelation, r = 0.42, P = 0.012, bootstrapped 95% CI (0.03, 0.73). One extreme multivariate Gini outlier (i.e., New York; see SI Appendix, Fig. S1) was excluded from the analyses when economic inequality was the predictor variable.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1616572114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Parsons T, Shils EA, Smelser NJ. Toward a General Theory of Action: Theoretical Foundations for the Social Sciences. Transaction Publishers; Piscataway, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durkheim E. The Division of Labor in Society. Simon and Schuster; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber M. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Univ of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durkheim E. 1897. Le Suicide (Germer-Baillière, Paris); reprinted (1979) (The Free Press, New York)

- 5.Marx K, Engels F. 1848. The Communist Manifesto (Bildungsgesellschaft für Arbeit, London); reprinted (1969) (Progress Publishers, Moscow)

- 6.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumer H. Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pac Sociol Rev. 1958;1:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vygotski LS. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehm C. Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis L. Dominance and reproductive success among nonhuman animals: A cross-species comparison. Ethol Sociobiol. 1995;16:257–333. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazur A. Biosociology of Dominance and Deference. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; Oxford, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiske AP. The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychol Rev. 1992;99:689–723. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill K, Kaplan H. Tradeoffs in Male and Female Reproductive Strategies Among the Ache. Human Reproductive Behaviour: A Darwinian Perspective. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1988. pp. 277–306. [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Rueden C, Gurven M, Kaplan H, Stieglitz J. Leadership in an egalitarian society. Hum Nat. 2014;25:538–566. doi: 10.1007/s12110-014-9213-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maynard Smith J. Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawkins R. Hierarchical organisation: A candidate principle for ethology. In: Bateson PPG, Hinde RA, editors. Growing Points in Ethology. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawley PH. The ontogenesis of social dominance: A strategy-based evolutionary perspective. Dev Rev. 1999;19:97–132. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnott G, Elwood RW. Assessment of fighting ability in animal contests. Anim Behav. 2009;77:991–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomsen L, Frankenhuis WE, Ingold-Smith M, Carey S. Big and mighty: Preverbal infants mentally represent social dominance. Science. 2011;331:477–480. doi: 10.1126/science.1199198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pun A, Birch SAJ, Baron AS. Infants use relative numerical group size to infer social dominance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:2376–2381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514879113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mascaro O, Csibra G. Representation of stable social dominance relations by human infants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6862–6867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113194109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller JA, et al. Competing for space: Female chimpanzees are more aggressive inside than outside their core areas. Anim Behav. 2014;87:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gintis H. The evolution of private property. J Econ Behav Organ. 2007;64:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidanius J, Pratto F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tooby J, Cosmides L. Groups in mind: The coalitional roots of war and morality. In: Høgh-Olesen H, editor. Human Morality And Sociality: Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2010. pp. 91–234. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pusey AE, Oehlert GW, Williams JM, Goodall J. Influence of ecological and social factors on body mass of wild chimpanzees. Int J Primatol. 2005;26:3–31. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McComb K, Packer C, Pusey A. Roaring and numerical assessment in contests between groups of female lions, Panthera leo. Anim Behav. 1994;47:379–387. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson ML, Wrangham RW. Intergroup relations in chimpanzees. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2003;32:363–392. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitani JC, Watts DP, Amsler SJ. Lethal intergroup aggression leads to territorial expansion in wild chimpanzees. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R507–R508. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen MW, Jones TL. Violence and Warfare Among Hunter-Gatherers. Left Coast Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wrangham RW, Peterson D. Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence. Houghton Mifflin Company; Boston: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinker S. The Better Angels of Our Nature. Viking; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. The Origin and Evolution of Cultures. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Toorn J, et al. A sense of powerlessness fosters system justification: Implications for the legitimation of authority, hierarchy, and government. Polit Psychol. 2015;36:93–110. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson R. The Impact of Inequality. The New Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The Spirit Level. Bloomsbury; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staub E. The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cialdini RB, Trost MR. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th Ed. Vol 1-2. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gelfand MJ, et al. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science. 2011;332:1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1197754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christ O, et al. Contextual effect of positive intergroup contact on outgroup prejudice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:3996–4000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320901111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jost JT, Banaji MR. The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. Br J Soc Psychol. 1994;33:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jost JT, Banaji MR, Nosek BA. A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Polit Psychol. 2004;25:881–919. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lerner MJ. The Belief in a Just World. Springer; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pratto F, Sidanius J, Stallworth LM, Malle BF. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:741–763. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guimond S, Dambrun M, Michinov N, Duarte S. Does social dominance generate prejudice? Integrating individual and contextual determinants of intergroup cognitions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:697–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levin S. Perceived group status differences and the effects of gender, ethnicity, and religion on social dominance orientation. Polit Psychol. 2004;25:31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pratto F, Sidanius J, Levin S. Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2006;17:271–320. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sidanius J, Cotterill S, Sheehy-Skeffington J, Kteily N, Carvacho H. Social dominance theory: Explorations in the psychology of oppression. In: Sibley C, Barlow FK, editors. Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2017. pp. 149–187. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomsen L, et al. Wolves in sheep’s clothing: SDO asymmetrically predicts perceived ethnic victimization among white and Latino students across three years. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36:225–238. doi: 10.1177/0146167209348617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kteily NS, Sidanius J, Levin S. Social dominance orientation: Cause or ‘mere effect?’: Evidence for SDO as a causal predictor of prejudice and discrimination against ethnic and racial outgroups. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2011;47:208–214. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ho AK, Sidanius J, Cuddy AJC, Banaji MR. Status boundary enforcement and the categorization of black–white biracials. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013;49:940–943. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodson G, Costello K. Interpersonal disgust, ideological orientations, and dehumanization as predictors of intergroup attitudes. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:691–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kteily N, Bruneau E, Waytz A, Cotterill S. The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;109:901–931. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navarrete CD, McDonald MM, Molina LE, Sidanius J. Prejudice at the nexus of race and gender: An outgroup male target hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98:933–945. doi: 10.1037/a0017931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pratto F, Shih M. Social dominance orientation and group context in implicit group prejudice. Psychol Sci. 2000;11:515–518. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sidanius J, et al. You’re inferior and not worth our concern: The interface between empathy and social dominance orientation. J Pers. 2013;81:313–323. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomsen L, Green EGT, Sidanius J. We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;44:1455–1464. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jost JT, Gaucher D, Stern C. The world isn’t fair. A system justification perspective on social stratification and inequality. In: Dovidio JF, Simpson JA, editors. Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2015. pp. 317–340. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glick P, et al. Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:763–775. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glick P, et al. Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86:713–728. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fischer R, Hanke K, Sibley CG. Cultural and institutional determinants of social dominance orientation: A cross-cultural meta-analysis of 27 societies. Polit Psychol. 2012;33:437–467. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee IC, Pratto F, Johnson BT. Intergroup consensus/disagreement in support of group-based hierarchy: An examination of socio-structural and psycho-cultural factors. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:1029–1064. doi: 10.1037/a0025410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cohrs JC, Stelzl M. How ideological attitudes predict host society members’ attitudes toward immigrants: Exploring cross-national differences. J Soc Issues. 2010;66:673–694. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pituch KA, Stapleton LM. Distinguishing between cross- and cluster-level mediation processes in the cluster randomized trial. Sociol Methods Res. 2012;41:630–670. [Google Scholar]

- 65.James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G. An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78:306–309. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piketty T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sidanius J, Pratto F. The inevitability of oppression and the dynamics of social dominance. In: Sniderman PM, Tetlock PE, Carmines EG, editors. Prejudice, Politics, and the American Dilemma. Stanford Univ Press; Stanford, CA: 1993. pp. 173–211. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, West SG. The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behav Res. 1999;34:315–346. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; Boca Raton, FL: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davison AC, Hinkley DV. Bootstrap Methods and Their Application. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Institute for Economics and Peace 2012. United States Peace Index (Institute for Economics and Peace, Washington, DC)

- 73.Census Bureau US. 2016. American FactFinder.

- 74.Glick P, Fiske ST. The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stapleton LM, Pituch KA, Dion E. Standardized effect size measures for mediation analysis in cluster-randomized trials. J Exp Educ. 2015;83:547–582. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.