Significance

Rising arctic temperatures could mobilize reservoirs of soil organic carbon trapped in permafrost. We present the first quantitative evidence for large, regional-scale early winter respiration flux, which more than offsets carbon uptake in summer in the Arctic. Data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Barrow station indicate that October through December emissions of CO2 from surrounding tundra increased by 73% since 1975, supporting the view that rising temperatures have made Arctic ecosystems a net source of CO2. It has been known for over 50 y that tundra soils remain unfrozen and biologically active in early winter, yet many Earth System Models do not correctly represent this phenomenon or the associated CO2 emissions, and hence they underestimate current, and likely future, CO2 emissions under climate change.

Keywords: carbon dioxide, Arctic, early winter respiration, Alaska, tundra

Abstract

High-latitude ecosystems have the capacity to release large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere in response to increasing temperatures, representing a potentially significant positive feedback within the climate system. Here, we combine aircraft and tower observations of atmospheric CO2 with remote sensing data and meteorological products to derive temporally and spatially resolved year-round CO2 fluxes across Alaska during 2012–2014. We find that tundra ecosystems were a net source of CO2 to the atmosphere annually, with especially high rates of respiration during early winter (October through December). Long-term records at Barrow, AK, suggest that CO2 emission rates from North Slope tundra have increased during the October through December period by 73% ± 11% since 1975, and are correlated with rising summer temperatures. Together, these results imply increasing early winter respiration and net annual emission of CO2 in Alaska, in response to climate warming. Our results provide evidence that the decadal-scale increase in the amplitude of the CO2 seasonal cycle may be linked with increasing biogenic emissions in the Arctic, following the growing season. Early winter respiration was not well simulated by the Earth System Models used to forecast future carbon fluxes in recent climate assessments. Therefore, these assessments may underestimate the carbon release from Arctic soils in response to a warming climate.

High-latitude ecosystems contain vast reservoirs of soil organic matter that are vulnerable to climate warming, potentially causing the Arctic to become a strong source of carbon dioxide (CO2) to the global atmosphere (1, 2). To quantitatively assess this carbon−climate feedback at a regional scale, we must untangle the effects of competing ecosystem processes (3). For example, uptake of CO2 by plants may be promoted by longer growing seasons in a warmer climate (4, 5) and by fertilization from rising levels of atmospheric CO2 (6). These gains, however, may be offset by carbon losses associated with permafrost thaw (7), enhanced rates of microbial decomposition of soil organic matter with rising temperature (8), a longer season of soil respiration (9), and the influence of increasing midsummer drought stress on plant photosynthesis (10). Warming may also trigger carbon losses by expanding burned areas and by allowing fires to burn deeper into organic soils (11).

Model simulations disagree on the sign and magnitude of the net annual carbon flux from Alaska (3). Observational constraints are limited: Year-round measurements of CO2 fluxes are very few, and the spatial scales are generally small (e.g., eddy flux and chamber studies) relative to the large extent and diversity of arctic and boreal landscapes. Incubation experiments show higher respiration rates as soils warm (8, 12, 13), which could more than offset any future increases in net primary productivity (14).

Summertime chamber measurements as early as the 1980s hinted that tundra ecosystems could potentially change from a sink to a source of carbon (15), and some modeling studies predict that carbon losses from soil will start to dominate the annual carbon budget by the end of the 21st century (16). A recent synthesis of eddy flux data from Alaskan tundra and boreal ecosystems calculated a neutral carbon balance for 2000–2011 (17), whereas a study of eddy flux towers in tundra ecosystems across the Arctic calculated highly variable carbon sources (18).

In this paper, we present a three-part synthesis to assess carbon fluxes and carbon−climate feedbacks in arctic and boreal Alaska. (i) We combine recent in situ aircraft and tower CO2 observations, eddy covariance flux data, satellite remote sensing measurements, and meteorological drivers to estimate regional fluxes of CO2. By taking advantage of the spatially integrative properties of the lower atmosphere, we use CO2 mole fraction data to constrain spatially explicit, temporally resolved CO2 flux distributions across Alaska during 2012–2014. We compute the annual carbon budget for Alaska, partitioned by season, ecosystem type, and source type (biogenic, pyrogenic, and anthropogenic, Figs. 1 and 2). (ii) We analyze the 40-y record of hourly atmospheric CO2 measurements from the land sector at Barrow, AK [BRW tower, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)], to place recent regional carbon fluxes in a historical context. (iii) We evaluate the Alaskan CO2 flux simulated by a representative set of Earth System Models (ESMs) against our CO2 fluxes for Alaska in 2012–2014, focusing on the net carbon budget, early winter respiration flux, and the duration and magnitude of the growing season carbon uptake. By combining and comparing these complementary approaches, we gain a more complete understanding of the Alaskan carbon budget and insight into how arctic carbon fluxes may respond to future climate change.

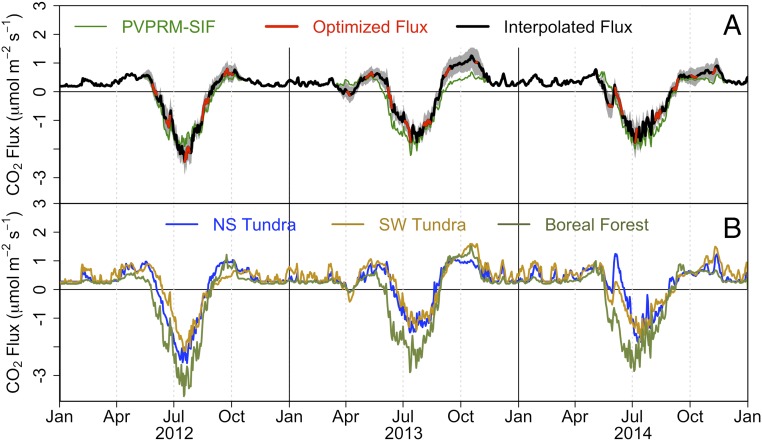

Fig. 1.

Time series of biogenic CO2 fluxes for Alaska during 2012–2014 calculated from CARVE aircraft data. (A) Mean daily net biogenic CO2 flux for Alaska during 2012–2014, with modeled (PVPRM-SIF) CO2 flux (green) and the aircraft optimized net CO2 flux (red) and interpolated aircraft optimized net CO2 flux (black). Our approach for estimating these fluxes and the uncertainty range (shown with shading) is described in SI Appendix, Calculation of the Additive Flux Correction. (B) Optimized biogenic CO2 fluxes for different regions in Alaska: NS tundra (blue), SW tundra (orange), and boreal forests (green).

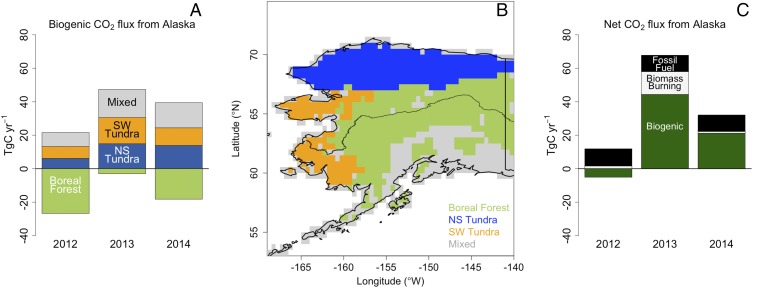

Fig. 2.

CO2 budget for Alaska 2012–2014. (A) Net biogenic carbon budget for boreal forests (light green), Yukon−Kuskokwim Delta of southwest Alaska and the Seward Peninsula to the west (SW tundra) (orange), NS tundra (blue), and the mixed areas or areas of Alaska not included in other regions (gray) (in teragrams of carbon per year) calculated from the aircraft optimized CO2 flux for 2012, 2013, and 2014. (B) Map of the regional areas described in A. Negative fluxes indicate uptake of CO2 by the biosphere. (C) Net carbon fluxes for Alaska during 2012–2014 from biogenic (dark green), biomass burning (white), and fossil fuel (black) components.

Methods

Regional Flux.

We measured altitude profiles of CO2 concentration (mole fraction relative to dry air) across Alaska during the Carbon in the Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE) flights (19) (SI Appendix, Aircraft Measurements), spanning April through November in 2012–2014. The aircraft observations quantified the structure and magnitude of gradients of CO2 concentration in the lower atmosphere, and we use these data to compute the mass-weighted, column-mean CO2 mole fraction in the atmospheric residual layer (defined in SI Appendix, Column Enhancement of CO2 and Fig. S1). By subtracting the CO2 mole fraction of air entering the region (SI Appendix, Background CO2Comparison and Fig. S2), we obtained column-integrated increments that represent the accumulated mass loading of CO2 due to surface fluxes (SI Appendix, Transport Model and Fig. S3). These measured column CO2 enhancements, which can be positive or negative, are minimally sensitive to fine-scale atmospheric structure and turbulent eddies, and their broad surface influence (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S3 and refs. 20 and 21) integrates over large areas with heterogeneous surface fluxes. We excluded the influence of biomass burning and fossil fuel combustion by removing profiles with carbon monoxide (CO) mole fractions exceeding 150 ppb.

We used a high-resolution transport model [Weather Research and Forecasting—Stochastic Time-Inverted Lagrangian Transport (WRF-STILT) model; SI Appendix, Transport Model and ref. 22) to calculate the influence function of land surface fluxes on each of the 231 vertical profiles collected on the CARVE flights. We obtained modeled column CO2 enhancements by convolving the land surface influence functions with diurnally resolved surface CO2 fluxes from the Polar Vegetation Photosynthesis and Respiration Model with Solar-induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence (PVPRM-SIF; SI Appendix, Calculating Biogenic CO2 Fluxes and Figs. S4 and S5). PVPRM-SIF is a functional representation of ecosystem CO2 fluxes parameterized using eddy covariance data for seven arctic and boreal vegetation types; it is applied regionally and temporally using satellite remote sensing data and assimilated meteorology (23). We focused our analysis on the domain of Alaska (58°N to 72°N, 140°W to 170°W; excluding the southeastern Alaskan Panhandle). Systematic differences were observed between the boundary layer enhancements and those predicted by the coupled WRF-STILT/PVPRM-SIF modeling system. The differences varied spatially and seasonally.

For each 2-wk measurement period, we obtained the additive corrections to PVPRM-SIF CO2 fluxes that minimized the differences between modeled and observed column CO2 enhancements [using a geostatistical inverse model (GIM), details of which are described in SI Appendix, Calculation of the Additive Flux Correction and Figs. S6 and S7]. This procedure yielded spatially explicit, data-constrained biogenic fluxes of CO2 for Alaska for each interval (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). The GIM constructs an optimal model of the flux correction by combining a linear model of predictors and a random component. Our GIM framework ensures an unbiased model of the flux correction under the assumption that all other errors (errors in the background concentration, transport model, etc.) are random and have a mean of zero. Uncertainties in our GIM (shaded uncertainty bounds in Fig. 1) were quantified using restricted maximum likelihood estimation (ReML). ReML uses statistical properties of the inputs to the GIM to constrain a model of the uncertainty. Our model does not account for systematic errors or bias in the background concentration, transport model, or sampling bias, although our model and observations were carefully chosen to minimize the effects of any bias.

Adjustments to the PVPRM-SIF flux estimates were generally small, less than ±1.5 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 for most regions and measurement periods. Large positive adjustments were needed, however, in early winter (September through November) of 2013, indicating considerably higher respiration rates than prior estimates from PVPRM-SIF. We linearly interpolated the additive flux corrections between aircraft measurement periods and used the PVPRM-SIF fluxes for late winter (January through April) to obtain regional-scale CO2 fluxes for Alaska during 2012–2014 (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). We independently confirmed the accuracy of these late winter fluxes by comparing year-round predicted CO2 enhancements with observations at tower sites in Alaska (24) (SI Appendix, Validation of Regional CO2Fluxes Using Tower Data and Fig. S10).

Long-Term CO2 Data.

The BRW tower, located just outside Barrow, AK [71.323°N, 156.611°W, ground elevation 11 m above sea level (masl)], is a 16.46-m tower operated by NOAA since 1973 (25), with consistent continuous CO2 data available from 1975 onward (SI Appendix, Long-Term BRW CO2Observations and Fig. S11). The tower is located within the footprint of the CARVE flights and provides a long-term context for the aircraft observations. We calculated the CO2 land influence as the difference between the ocean and land sector CO2 data (dCO2) (ref. 26 and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). We calculated the monthly mean dCO2 for early winter months (September through December) in each 11-y time interval (SI Appendix, Fig. S13) and, using the years with data in each month, calculated the 95% confidence interval for the change in dCO2 over October through December between 1975 and 1989 and between 2004 and 2015 (Fig. 3). Results were indistinguishable using alternative statistical approaches, including linear regressions or locally weighted least squares (“loess”) assessment of the time series of fall observations. We used the CARVE flux calculations to infer the magnitude of the change in early winter CO2 flux corresponding to the change in dCO2 from land emission on the North Slope surrounding BRW. The largest unaccounted uncertainties in the BRW tower analysis include the potential for systematic shifts in the circulation patterns in the region between 1979 and 2014, or changes in the surrounding environment of the tower. We performed comprehensive tests for these possible effects, and found no evidence for systematic changes in either, as discussed in SI Appendix, Long-Term BRW CO2Observations.

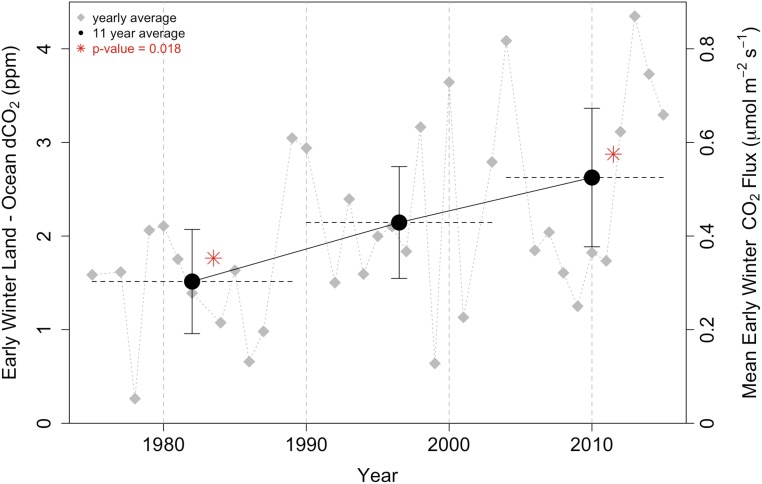

Fig. 3.

Early winter (October through December) land−ocean sector CO2 signal (dCO2) measured at the NOAA BRW tower in Barrow, AK, since 1975. The tower is influenced by a large area of the North Slope. The early winter land sector dCO2 has increased by 73.4% ± 10.8% at BRW over 41 y [1.51 ± 0.64 ppm in 1975–1989 to 2.62 ± 0.85 ppm in 2004–2015, a statistically significant increase with P value 0.018, indicated by red asterisks (*)]. Shown are the yearly averaged data (gray diamonds) and 11-y average (black circles) with 95% confidence intervals (error bars) and dashed lines to indicate the years sampled. Using the fluxes calculated as part of the aircraft optimization, the mean flux of CO2 on the North Slope has increased by a comparable amount, from 0.24 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 in 1975–1989 to 0.43 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 in 2004–2015.

Earth System Models.

We examined the Alaskan CO2 fluxes from ESM simulations contributed to the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) (27), a community modeling effort designed to support the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report scientific assessment (SI Appendix, Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 and Fig. S14). We analyzed future ESM projections forced with Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 atmospheric CO2 mole fractions, and extracted time series from 2006 through 2014, when fossil fuel emissions, CO2 concentrations, and ambient climate closely matched observations (28). The models reported simulated monthly mean CO2 fluxes (net ecosystem exchange) at each grid cell. We extracted fluxes from each model for the same Alaskan domain used in our inversion of the aircraft observations (58°N to 72°N, 140°W to 170°W).

Results and Discussion

Biogenic Carbon Fluxes Across Alaska.

We inferred a net source of biogenic CO2 from Alaska for the years 2013 and 2014, whereas 2012 was nearly CO2 neutral (Figs. 1 and 2 and SI Appendix, Total Alaskan CO2 Flux and Table S1). The PVPRM-SIF fluxes (when convolved with the transport model) captured much of the observed diurnal, seasonal, and interannual variability in column CO2 observations across the 3 y (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Sunlight and air temperature, which generated the diurnal variability of the PVPRM-SIF CO2 fluxes, were key drivers of the highly variable summer CO2 uptake in Alaska.

Uncertainties were larger for individual subregions, but basic patterns clearly emerge. Tundra regions on the North Slope (NS tundra) and in the Yukon−Kuskokwim Delta of south-west Alaska and the Seward Peninsula to the west (SW tundra) were consistently, and statistically significant, net sources of CO2 (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Table S1). Losses of CO2 from the NS tundra were nearly 3 times greater in 2013 and 2014 than in 2012. The mean net CO2 source from SW tundra in 2012–2014 was similar to the NS tundra, but the SW tundra yearly variations were different, with a large source in 2013, smaller in 2014, and smallest in 2012 (Fig. 1). The source of CO2 from NS tundra is consistent with the CO2 budget calculated from the sparse eddy flux measurements for the region (29–32). There were no year-round CO2 flux measurements in the SW tundra region to help confirm our airborne estimates.

The boreal forest ecoregion was a net CO2 sink in all years, neglecting biomass burning (Figs. 1 and 2 and SI Appendix, Table S1). Carbon uptake by boreal forests was smaller in 2013 than in other years, when the climate was warmer and drier. There was less CO2 respiration during the early winter periods of 2014, possibly due to high June through August precipitation and cooler temperatures; long-term measurements of CO2 fluxes have shown that water-saturated soils exhibit lower rates of soil respiration in boreal forests (33–35). The remaining 18% of Alaskan land surface (here called the “Mixed” area), which includes coastal plains, mountainous areas, and areas that cannot be classified as mostly forest or tundra, was a net source of carbon each year.

Net carbon uptake started 6 d to 16 d earlier in Alaskan boreal forests than in the NS tundra regions, depending on the year (Fig. 1). In tundra, uptake is delayed for some time after snow melts and ecosystem greenness increases, whereas evergreen trees may begin to take up CO2 when air temperatures rise above 0 °C in spring (33). Models driven by solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) appear to capture the delay between snowmelt and net CO2 uptake in both ecosystems (SI Appendix, Growing Season Length), whereas models driven by vegetation indices (e.g., enhanced vegetation index) do not (23). For example, PVPRM-SIF reproduced the spring onset of net CO2 uptake to within 2 d (SI Appendix, Growing Season Length and Fig. S5).

Total Carbon Budget.

We assessed Alaskan regional fossil fuel and biomass burning CO2 emissions (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Total Alaskan CO2Flux), to compare our biogenic flux estimates with anthropogenic and disturbance sources. Alaska is sparsely populated, so fossil fuel CO2 emissions are concentrated in a few metropolitan areas. The anthropogenic CO2 flux for Alaska was estimated at 10.0 ± 0.26 TgC⋅y−1 for 2012–2014. Biomass burning emissions of CO2 were highly variable across the 3 y. According to the Alaskan Fire Emissions Database (AKFED) (36), biomass burning emissions were between 1.0 TgC⋅y−1 and 1.6 TgC⋅y−1 in 2012 and 2014, but reached 11 TgC⋅y−1 in 2013 (Fig. 2), with emissions predominantly from boreal forests in interior Alaska. Nonbiogenic carbon emissions cancelled out biogenic carbon uptake in 2012, resulting in a small source of carbon [6.5 (−9.9, 26.2 95% CI) TgC⋅y−1] in 2012. In 2013, and to a lesser extent in 2014, the biogenic source of carbon dominated the budget, resulting in a large net source of carbon to the atmosphere: 67.8 (40.3, 94.6) TgC in 2013 and 32.1 (10.1, 53.4) TgC in 2014.

Long-Term Trends in Early Winter Respiration.

NOAA's BRW tower on the North Slope of Alaska provides a unique, continuous long-term record that allows us to place our contemporary regional carbon budget in the context of long-term climate variations and trends, and to assess the sensitivity of the early winter respiration to changes in climate (25) (SI Appendix, Long-Term BRW CO2Observations and Figs. S11 and S12). We found that the CO2 mole fraction anomaly from the land sector, dCO2, averaged over early winter (October through December) increased by 73.4% ± 10.8% during the 41 y of the record (1975−2015; Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). The land sector respiration signal was strongly correlated with the nighttime air temperature of the previous summer (r2 = 0.95), a measure of the temperature at the air−soil interface and an indicator of the amount of heat that will be trapped under the snow during early winter. Long-term records of soil temperature within permafrost increased by nearly 2 °C at a depth of 10 m near Barrow since 1950 (37).

Using the CARVE flux estimation framework (SI Appendix, Framework to Predict Integrated CO2 Column), we calculated that the observed dCO2 increase corresponded to a comparable increase in the early winter CO2 flux over the 41-y record (Fig. 3). Emissions of CO2 in early winter lag the uptake in the growing season by 3 mo to 4 mo, and hence this increase in emissions very likely contributed to the increase of the seasonal amplitude of regional CO2 concentrations observed since 1960 (38).

The occurrence of early winter respiration in arctic ecosystems has been known for nearly 50 y (39–42). Early flux studies at tundra sites on the North Slope hinted that cold season CO2 respiration might offset increases in summer uptake with warming (30), and recent studies show large early winter respiration at some tundra sites (31). However, cold season CO2 respiration has not previously been quantified at regional scales. The extended respiration during early winter is likely linked to continuing microbial oxidation of soil organic matter during the “zero curtain” period, the extended interval when soil temperatures in the active layer are poised near 0 °C and some water is still liquid (9). Complete freezing of soils in the fall is delayed by release of latent heat, dissolved solutes, and insulation of the soil by overlying snow (27). The length of the zero curtain period appears to be increasing with warming temperatures, with the duration at some sites now reaching up to 100 d (9). From our results, we expect a warming climate and extended zero curtain periods to drive larger biogenic emissions and further increase early winter respiration in the future.

Carbon Fluxes from ESMs.

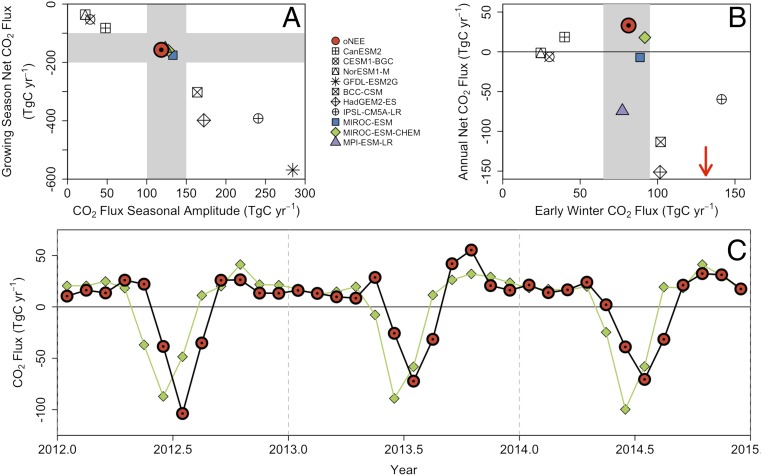

To create realistic projections of future climate, we must have a robust understanding of the current carbon budget simulated by ESMs that are widely used to assess carbon−climate feedbacks. We compared our regional flux observations (43) to the carbon fluxes for Alaska reported by 11 ESMs used in CMIP5 (used by the IPCC) (SI Appendix, Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5). These models generally predict the start of growing season earlier than observed, and most underestimate the high respiration rates in early winter (SI Appendix, Table S2). Consequently, 8 of 11 model simulations inaccurately predict both the seasonal amplitude of CO2 fluxes and the net annual CO2 flux (Fig. 4A). Only 3 of the 11 CMIP5 models captured the growing season fluxes relatively well, and even those models predicted the annual net CO2 flux as more negative (too much uptake) than observations (Fig. 4B). The most realistic model (MIROC-ESM-CHEM) correctly predicts an annual net source of CO2, but with the growing season shifted a month too early (Fig. 4C). The shortfalls of these models reflect their limited mechanistic representation of permafrost soil carbon processes. The models incorrectly simulated net accumulation of carbon in high-latitude soils, at least in part because the zero curtain is not represented. We conclude that the representation of the zero curtain must be improved within ESMs to accurately predict the magnitude of the positive feedback between arctic soils, carbon, and climate during the remainder of the 21st century.

Fig. 4.

CMIP5 ESM behavior compared with the monthly mean optimized CO2 flux from our analysis. (A) Growing season net CO2 flux (in teragrams of carbon per year) against the CO2 flux seasonal amplitude (in teragrams of carbon per year) indicate three model groupings. (B) Annual net CO2 flux (in teragrams of carbon per year) against early winter (September through December) CO2 flux. The arrow indicates the early winter flux of the GFDL-ESM2G model (annual net flux is −328 TgC⋅y−1). (C) Time series of CO2 flux for the model with the closest matching carbon fluxes in A and B (MIROC-ESM-CHEM) and the aircraft optimized CO2 flux. The modeled peak carbon uptake in summer is too large and a month too early compared with the aircraft optimized CO2 flux. Negative fluxes represent uptake by the biosphere.

The amplitude of the CO2 seasonal cycle at high latitudes has increased over the past 50 y (44), a striking indication of significant changes in the carbon cycle. In recent literature, there is considerable debate whether this change arises from increased vegetative uptake (e.g., refs. 44–46), which would enhance carbon sequestration in the region, or increased rates of respiration (1, 2), driving the release of soil organic matter and net emission of carbon. Unequal changes in the timing or magnitude of peak photosynthesis or respiration will also affect the amplitude of the CO2 seasonal cycle. Also, increased photosynthetic uptake in spring could lead to increased respiration in early winter using recent labile organic matter (e.g., refs. 2 and 47), with no effect on net annual carbon sequestration.

Many of the assessments of the changing CO2 seasonal amplitude are based on model simulations that appear not to capture the magnitude or trends in late season respiration, and, indeed, may predict an annual net sink for CO2 in Alaska where we observed net emissions. Our results suggest the need to reevaluate this work. The regional fluxes we infer show the importance of early winter fluxes, and the long-term CO2 data from the BRW tower indicate that early winter respiration rates have increased considerably over the past 41 y. These results imply that carbon release from organic matter may make a more important contribution to trends in the CO2 seasonal amplitude than expected from model simulations that may not capture the late season respiration correctly.

Conclusions

We find that Alaska, overall, was a net source of carbon to the atmosphere during 2012–2014, when net emissions from tundra ecosystems overwhelmed a small net uptake from boreal forest ecosystems. Both ecosystems emitted large amounts of carbon in early winter. Our results suggest that October through December respiration has increased by about 73% over the past 41 y from organic carbon-rich soils on the North Slope of Alaska, correlated with increasing air temperatures. The ESMs used to forecast future carbon fluxes in the CMIP5 and IPCC studies did not represent early winter respiration, especially when soil temperatures hover near 0 °C. Hence these assessments may underestimate the carbon release from arctic soils in response to warming climate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the pilots, flight crews, and NASA Airborne Science staff from the Wallops Flight Facility for enabling the CARVE science flights. We thank J. Budney, A. Dayalu, E. Gottlieb, M. Pender, J. Pittman, and J. Samra for their help during CARVE flights; M. Mu for CMIP5 simulations; J. Joiner for GOME-2 SIF fields; and J. W. Munger for helpful discussion. Part of the research described in this paper was undertaken as part of CARVE, an Earth Ventures investigation, under contract with NASA. Part of the research was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), California Institute of Technology, under a contract with NASA. We acknowledge funding from NOAA, NASA Grants NNX13AK83G, NNXNNX15AG91G, and 1444889 (through JPL), the National Science Foundation Arctic Observation Network program (Grant 1503912), and the US Geological Survey Climate Research and Development Program. Computing resources for this work were provided by the NASA High-End Computing Program through the NASA Advanced Supercomputing Division at the Ames Research Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper are available at the following links: regional gridded CO2 fluxes, doi: 10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1389; CARVE aircraft CO2 data, doi: 10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1402; PVPRM-SIF, doi: 10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1314; CRV tower CO2 data, doi: 10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1316; and BRW tower CO2 data, doi: 10.7289/V5RR1W6B.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1618567114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Koven CD, et al. Permafrost carbon-climate feedbacks accelerate global warming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14769–14774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103910108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piao S, et al. Net carbon dioxide losses of northern ecosystems in response to autumn warming. Nature. 2008;451:49–52. doi: 10.1038/nature06444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire AD, et al. An assessment of the carbon balance of Arctic tundra: Comparisons among observations, process models, and atmospheric inversions. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:3185–3204. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angert A, et al. Drier summers cancel out the CO2 uptake enhancement induced by warmer springs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10823–10827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501647102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black TA, et al. Increased carbon sequestration by a boreal deciduous forest in years with a warm spring. Geophys Res Lett. 2000;27:1271–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oechel WC, et al. Transient nature of CO2 fertilization in Arctic tundra. Nature. 1994;371:500–503. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuur EAG, et al. Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature. 2015;520:171–179. doi: 10.1038/nature14338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb EE, et al. Increased wintertime CO2 loss as a result of sustained tundra warming. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2016;121:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zona D, et al. Cold season emissions dominate the Arctic tundra methane budget. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:40–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516017113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetz SJ, Bunn AG, Fiske GJ, Houghton RA. Satellite-observed photosynthetic trends across boreal North America associated with climate and fire disturbance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13521–13525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506179102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turetsky MR, et al. Recent acceleration of biomass burning and carbon losses in Alaskan forests and peatlands. Nat Geosci. 2011;4:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natali SM, et al. Permafrost thaw and soil moisture driving CO2 and CH4 release from upland tundra. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2015;120:525–537. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schädel C, et al. Potential carbon emissions dominated by carbon dioxide from thawed permafrost soils. Nat Clim Change. 2016;6:950–953. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Natali SM, Schuur EAG, Rubin RL. Increased plant productivity in Alaskan tundra as a result of experimental warming of soil and permafrost. J Ecol. 2012;100:488–498. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oechel WC, Hastings SJ, Vourlrtis G, Jenkins M. Recent change of Arctic tundra ecosystems from a net carbon dioxide sink to a source. Nature. 1993;361:520–523. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer K, Lantuit H, Romanovsky VE, Schuur EAG, Witt R. The impact of the permafrost carbon feedback on global climate. Environ Res Lett. 2014;9:085003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ueyama M, et al. Upscaling terrestrial carbon dioxide fluxes in Alaska with satellite remote sensing and support vector regression. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2013;118:1266–1281. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belshe EF, Schuur EAG, Bolker BM. Tundra ecosystems observed to be CO2 sources due to differential amplification of the carbon cycle. Ecol Lett. 2013;16:1307–1315. doi: 10.1111/ele.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang RYW, et al. Methane emissions from Alaska in 2012 from CARVE airborne observations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16694–16699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412953111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou WW. Net fluxes of CO2 in Amazonia derived from aircraft observations. J Geophys Res. 2002;107:4614. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wofsy S, Kaplan W, Harriss R. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over the Amazon basin. J Geophys Res. 1988;93:1377–1387. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson JM, et al. Atmospheric transport simulations in support of the Carbon in Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE) Atmos Chem Phys. 2015;15:4093–4116. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luus KA, et al. Tundra photosynthesis captured by satellite-observed solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence. Geophys Res Lett. 2017;44:1564–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karion A, et al. Investigating Alaskan methane and carbon dioxide fluxes using measurements from the CARVE tower. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:5383–5398. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thoning K, Kitzis DR, Crotwell A. 2016 Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Dry Air Mole Fractions from quasi-continuous measurements at Barrow, Alaska. Available at https://gis.ncdc.noaa.gov. Accessed January 31, 2017.

- 26.Sweeney C, et al. No significant increase in long-term CH4 emissions on North Slope of Alaska despite significant increase in air temperature. Geophys Res Lett. 2016;43:6604–6611. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2012;93:485–498. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quéré CL, et al. Global Carbon Budget 2015. Earth Syst Sci Data. 2015;7:349–396. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Euskirchen ES, Bret-Harte MS, Scott GJ, Edgar C, Shaver GR. Ecosphere. 2012;3:art4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Euskirchen ES, Bret-Harte MS, Shaver GR, Edgar CW, Romanovsky VE. Long-term release of carbon dioxide from arctic tundra ecosystems in Alaska. Ecosystems. November 21, 2016 doi: 10.007/s10021-016-0085-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oechel WC, et al. Acclimation of ecosystem CO2 exchange in the Alaskan Arctic in response to decadal climate warming. Nature. 2000;406:978–981. doi: 10.1038/35023137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oechel WC, Laskowski CA, Burba G, Gioli B, Kalhori AAM. Annual patterns and budget of CO2 flux in an Arctic tussock tundra ecosystem. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2014;119:323–339. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ueyama M, Iwata H, Harazono Y. Autumn warming reduces the CO2 sink of a black spruce forest in interior Alaska based on a nine-year eddy covariance measurement. Glob Change Biol. 2014;20:1161–1173. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunn AL, Barford CC, Wofsy SC, Goulden ML, Daube BC. A long-term record of carbon exchange in a boreal black spruce forest: means, responses to interannual variability, and decadal trends. Glob Change Biol. 2007;13:577–590. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Euskirchen ES, Edgar CW, Turetsky MR, Waldrop MP, Harden JW. Differential response of carbon fluxes to climate in three peatland ecosystems that vary in the presence and stability of permafrost. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2014;119:1576–1595. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veraverbeke S, Rogers BM, Randerson JT. Daily burned area and carbon emissions from boreal fires in Alaska. Biogeosciences. 2015;12:3579–3601. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiklomanov NI, et al. Decadal variations of active-layer thickness in moisture- controlled landscapes, Barrow, Alaska. J Geophys Res. 2010;115:G00104. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelley JJ, Jr, Weaver DF, Smith BP. The variation of carbon dioxide under the snow in the Arctic. Ecology. 1968;49:358–361. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coyne PI, Kelley JJ. Release of carbon dioxide from frozen soil to the Arctic atmosphere. Nature. 1971;234:407–408. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks PD, Williams MW, Schmidt SK. Microbial activity under alpine snowpacks, Niwot Ridge, Colorado. Biogeochemistry. 1996;32:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks PD, Schmidt SK, Williams MW. Winter production of CO2 and N2O from alpine tundra: Environmental controls and relationship to inter-system C and N fluxes. Oecologia. 1997;110:403–413. doi: 10.1007/PL00008814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Randerson JT, Field CB, Fung IY, Tans PP. Increases in early season ecosystem uptake explain recent changes in the seasonal cycle of atmospheric CO2 at high northern latitudes. Geophys Res Lett. 1999;26:2765–2768. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Commane R, et al. 2017. CARVE: Regional gridded CO2 fluxes at 0.5 degrees for Alaska, 2012–2014. Oak Ridge National Laboratory Distributed Active Archive Center. dx.doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1389.

- 44.Graven HD, et al. Enhanced seasonal exchange of CO2 by northern ecosystems since 1960. Science. 2013;341:1085–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.1239207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenzel S, Cox PM, Eyring V, Friedlingstein P. Projected land photosynthesis constrained by changes in the seasonal cycle of atmospheric CO2. Nature. 2016;538:499–501. doi: 10.1038/nature19772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forkel M, et al. Enhanced seasonal CO2 exchange caused by amplified plant productivity in northern ecosystems. Science. 2016;351:696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phoenix GK, Bjerke JW. Arctic browning: Extreme events and trends reversing arctic greening. Glob Change Biol. 2016;22:2960–2962. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.