Significance

Secretion of neurotransmitters and hormones depends on membrane fusion, accomplished by a cellular fusion machinery whose core components are SNARE proteins. Several vesicle-associated v-SNAREs form SNAREpin complexes with target membrane-associated t-SNAREs, but how they cooperate to catalyze fusion is unknown. Using highly coarse-grained simulations, we found that steric interactions spontaneously organized SNAREpins into circular clusters, expanded the clusters, and forced membranes together. These are entropic effects, reminiscent of cooperative transitions in solutions of rod-like molecules. The rate of fusion was controlled by the number of SNAREs, because more SNAREs generated greater entropic forces. Given ∼70 v-SNAREs available per synaptic vesicle, entropic cooperativity among SNAREpins may underlie the sub-millisecond timescale of neurotransmitter release.

Keywords: SNARE, membrane fusion, exocytosis, entropic force, neurotransmitter release

Abstract

SNARE proteins are the core of the cell’s fusion machinery and mediate virtually all known intracellular membrane fusion reactions on which exocytosis and trafficking depend. Fusion is catalyzed when vesicle-associated v-SNAREs form trans-SNARE complexes (“SNAREpins”) with target membrane-associated t-SNAREs, a zippering-like process releasing ∼65 kT per SNAREpin. Fusion requires several SNAREpins, but how they cooperate is unknown and reports of the number required vary widely. To capture the collective behavior on the long timescales of fusion, we developed a highly coarse-grained model that retains key biophysical SNARE properties such as the zippering energy landscape and the surface charge distribution. In simulations the ∼65-kT zippering energy was almost entirely dissipated, with fully assembled SNARE motifs but uncomplexed linker domains. The SNAREpins self-organized into a circular cluster at the fusion site, driven by entropic forces that originate in steric–electrostatic interactions among SNAREpins and membranes. Cooperative entropic forces expanded the cluster and pulled the membranes together at the center point with high force. We find that there is no critical number of SNAREs required for fusion, but instead the fusion rate increases rapidly with the number of SNAREpins due to increasing entropic forces. We hypothesize that this principle finds physiological use to boost fusion rates to meet the demanding timescales of neurotransmission, exploiting the large number of v-SNAREs available in synaptic vesicles. Once in an unfettered cluster, we estimate ≥15 SNAREpins are required for fusion within the ∼1-ms timescale of neurotransmitter release.

Exocytosis and trafficking in cells depend on membrane fusion reactions, almost all of which are mediated by SNARE proteins (1–3). Fusion is catalyzed by the assembly of vesicle-associated v-SNAREs and target membrane-associated t-SNAREs into coiled coils of α-helices to form trans-SNARE complexes (“SNAREpins”). Assembly initiates at the N-terminal ends of the SNARE motifs and propagates toward the C-terminal transmembrane domains (TMDs) in a zipper-like fashion, pulling the membranes into close proximity and triggering fusion by a mechanism that remains poorly understood.

An unanswered question is how SNARE proteins deliver the energy required to fuse membranes, estimated to be ∼40–140 kT (4–6). A common view is that the ∼65 kT per SNAREpin released during zippering (7) provides the necessary energy, but how this is coupled to the membranes is unclear given that the uncomplexed v-SNARE is largely unstructured and presumably flexible (8). It has been proposed that the linker domains (LDs) connecting the SNARE motifs to the TMDs are stiff, so that some zippering energy could be stored as LD bending energy that could deform and fuse membranes (3, 9). Such an effect would presumably be abolished by even a single flexible region. However, EPR spectroscopy suggests linkers are partially flexible (10), and insertion of flexible residues of increasing length into LDs reduces fusion progressively (11–13), raising doubts about stiffness-based models. Further, in a study of vesicle fusion SNARE core zippering occurred much more rapidly than lipid mixing (14). Overall, in the absence of regulatory proteins SNAREs have likely fully assembled before fusion has occurred, with the energy of zippering largely dissipated (15, 16).

Fusion seems to result from the cooperative effect of several SNAREs, but the mechanism of cooperation is unknown and the number of SNAREs involved has been much debated. In vivo, requirements for fusion in the range of two to eight SNAREpins have been variously reported (17–20). Interestingly, fusion was strongly accelerated at neuronal synapses when a constitutively open mutation of the t-SNARE syntaxin increased the number of SNARE complexes that fused vesicles, suggesting fusion rates depend on the number of SNAREs (21). In vitro, one to three SNAREpins were reported sufficient to fuse small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs, ∼40 nm) (22, 23), whereas fast fusion (∼10–250 ms) of SUVs with supported bilayers (SBLs) required 5–10 SNAREpins (24, 25). Another study suggests a size-dependent requirement, with up to ∼30 SNAREs needed to fuse large (∼100 nm) vesicles (26).

Molecularly explicit simulations can potentially address these mechanistic questions by recapitulating molecular processes difficult to capture experimentally. Atomistic and more coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations provided important structural and short-time dynamical information (9), but the computationally accessible timescales (nanoseconds to microseconds) were much less than experimental fusion timescales (milliseconds to seconds), forcing the use of unphysical simulation conditions to achieve fusion (27).

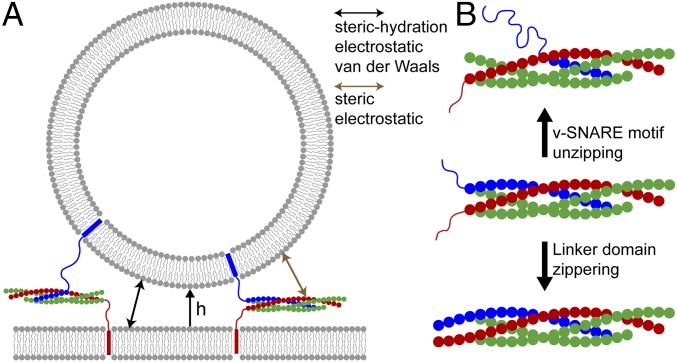

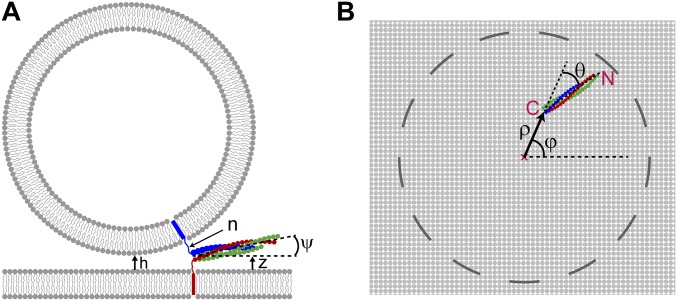

Here we use a highly coarse-grained theoretical framework to describe the collective behavior of many SNAREs on the long timescales of fusion (Fig. 1). The coarse graining is by necessity radical but retains key biophysical properties such as SNARE zippering energy landscape, charge distribution, and geometry.

Fig. 1.

Coarse-grained model of SNAREpins at the fusion site. (A) SNAREpins bridge a vesicle and planar membrane with minimum separation h (only two SNAREpins shown). t-SNARE motifs (red and green) are zippered, whereas VAMP motif (blue) can have any degree of zippering. Zippering obeys energy landscape measured in ref. 7 (Fig. S2). TMDs are mobile in the membranes and SNARE complexes have arbitrary orientation consistent with steric constraints. SNAREpins interact with one another, and with membrane surfaces, through steric-electrostatic forces. Membranes are continuous fixed-shape surfaces, interacting via steric-hydration, electrostatic, and van der Waals forces. (B) SNARE coarse-graining scheme. The SNARE complex is a coiled coil of four α-helices, VAMP (one, blue), syntaxin (one, red), and SNAP-25 (two, green). Structured helices are represented as beads. A bead carries the charges of its residues (approximately four structured residues per bead) and represents the contribution of one helix to one of the 16 layers of the SNARE complex (30, 31). Uncomplexed segments are unstructured worm-like chains. (Middle) Fully assembled SNARE motifs, uncomplexed LDs. Relative to this state v-SNARE unzipping (Top) or LD zippering (Bottom) can occur.

Model

We model the situation in exocytosis, with a vesicle and target planar membrane bridged by SNAREpins whose degrees of assembly are free to vary (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). We seek the collective behavior on millisecond–second fusion timescales, orders of magnitude beyond current simulations (27). Our highly coarse-grained description preserves key measured SNARE properties and represents membranes as continuous surfaces interacting via steric-hydration, electrostatic, and van der Waals forces (28, 29). For model parameters, see Tables S1 and S2.

Fig. S1.

Coarse-grained model of SNAREpins and membranes. SNAREpins bridge a vesicle and planar membrane with minimum separation h (only two SNAREpins shown). t-SNARE motifs (red and green) are zippered, whereas the VAMP motif (blue) can have any degree of zippering. Zippering follows the energy landscape measured in ref. 7 (Fig. S2). SNARE complexes have arbitrary orientation consistent with steric constraints. TMDs are represented as attachment points 1 nm below the membrane surfaces and are laterally mobile. Their position is set to minimize the stretching energy of the unstructured domains. SNAREpins interact with one another, and with the membrane surfaces, through steric-electrostatic forces. Membranes are continuous fixed-shape surfaces, interacting via steric-hydration, electrostatic, and van der Waals forces.

Table S1.

Principal model parameters

| Symbol | Meaning | Value |

| Debye length | 0.8 nm* | |

| Hamaker constant | J† | |

| Decay length for intermembrane steric-hydration force | 0.2 nm‡ | |

| Pressure prefactor for intermembrane steric-hydration force | dyn/cm2‡ | |

| Persistence length of uncomplexed SNARE domains | 0.6 nm§ | |

| — | Contour length of uncomplexed SNARE domains, per residue | 0.365 nm§ |

| — | Length of SNARE bundle | 10 nm¶ |

| — | Thickness of SNARE bundle | 2 nm¶ |

| Temperature | 298 K# |

Calculated using a physiological salt concentration of 0.15 M.

Typical value for lipid bilayers, from ref. 29.

Calculated as the composition weighted mean of the values reported for pure substances from ref. 28. Membranes considered in this study contained 82% PC, 3% PE, and 15% PS, mimicking a typical composition used for in vitro assays (11). We assumed that PS and PE have similar hydration properties.

Typical values for unstructured polypeptides, from ref. 7.

Estimated using PyMOL software using PDB ID code 3HD7.

The value used for all simulations except for temperature sweep simulations.

Table S2.

Charges assigned to the beads that represent an assembled SNARE complex in our model

| Bead no. | VAMP | Syntaxin | SN1 | SN2 |

| 1 | — | — | 0 | — |

| 2 | — | 0 | 1 | — |

| 3 | — | 0 | −2 | — |

| 4 | — | 2 | 2 | — |

| 5 | — | −1 | −1 | 0 |

| 6 | — | 0 | −2 | −2 |

| 7 | 2 | −1 | 0 | −2 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | −1 | 0 | −2 | 0 |

| 10 | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 |

| 13 | 0 | −1 | −2 | −1 |

| 14 | 0 | −2 | −2 | 0 |

| 15 | −2 | 0 | −1 | 0 |

| 16 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 2 |

| 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −2 |

| 19 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 1 |

| 20 | 1 | 2 | −1 | −1 |

| 21 | 3 | 1 | — | — |

| 22 | 1 | 3 | — | — |

| 23 | 1 | 2 | — | — |

Charges are in units of the electronic charge (e). The 20th bead represents the +8 layer of the SNARE complex (corresponding to residues 252–255 on syntaxin, 81–84 on VAMP, 79–82 on SN1, and 200–203 on SN2), and the bead numbers decrease toward the N-terminal domain. Beads 21–23 represent complexed LDs. Each bead represents four SNARE residues and is assigned a charge equal to the net charge of the residues it represents at pH 7, calculated from the PDB2PQR web server using PDB ID code 3HD7 and the CHARMM forcefield option.

A key point is that, given typical vesicle and TMD diffusivities, the relaxation time of the SNARE-membrane system is less than the milliseconds to seconds required for fusion (24, 25) (SI Text). We conclude that the SNAREpins equilibrate before fusion, so configurational and other statistical properties follow Boltzmann’s distribution and can be calculated using a Monte Carlo (MC) simulation. Fusion occurs when the fluctuating membrane energy overcomes the barrier to fusion, . Using the MC simulation to calculate the distribution of values, we compute the probability of such a fluctuation and hence the relative fusion rates.

Coarse-Grained Representation of SNARE Proteins.

The fully structured neuronal SNARE complex is a coiled coil of four α-helices, one from each of VAMP and syntaxin and two from SNAP-25 (30, 31). We assume the t-SNARE motifs are structured (3), but the VAMP motif can zipper/unzip freely. The uncomplexed segment of each VAMP and syntaxin (connecting the complexed segment to the TMD) is assumed unstructured and treated as a worm-like chain (7), whereas the helical part is represented by a sequence of beads. Each bead represents four structured residues corresponding to one of the 16 layers comprising the SNARE complex (30, 31), compared with approximately four beads per residue for the MARTINI model (32) and one bead per residue for a recently developed coarse-grained representation of SNAREs (33). A bead carries on its surface the net charge of its residues (Fig. 1B and Table S2). VAMP zippers reversibly in a sequence of layer-by-layer events, each converting four unstructured VAMP residues into one VAMP bead in the SNARE complex with a binding energy obeying the measured zippering energy landscape (7) (Fig. S2). Zippering of the VAMP and syntaxin LDs is a similar unstructured-to-α-helix transition. For details, see SI Text.

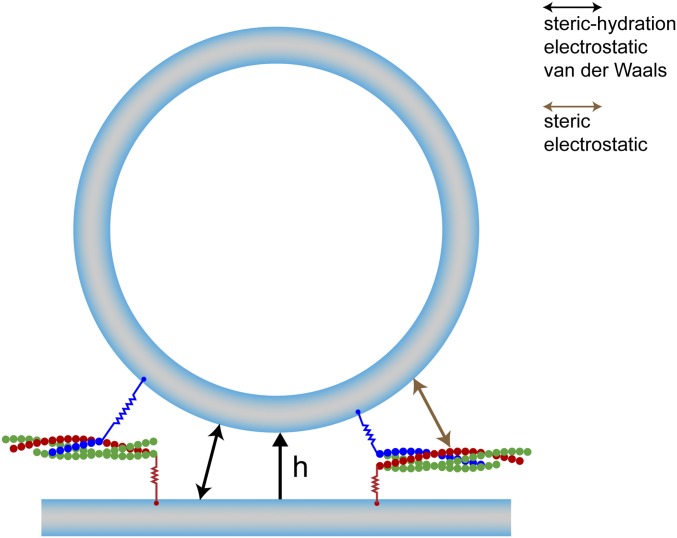

Fig. S2.

Energy landscape for SNARE zippering, generated from measurements by Gao et al. (7). The zippering energy of neuronal SNAREs is shown as a function of the length of the uncomplexed portion of the v-SNARE (VAMP, blue), with the zero energy state defined to be the completely zippered state including complexed LDs. In ref. 7 the reaction coordinate was taken as the SNARE complex contour length. This coordinate was converted to the contour length of the uncomplexed portion of the v-SNARE, assuming that the SNARE complex contour length is the sum of the contour lengths of the uncomplexed portions of VAMP and syntaxin and the SNARE complex thickness.

MC Simulation.

The membrane separation can change, and SNAREpins can zipper/unzip and move by lateral TMD motion and by translation or reorientation (Fig. 1). At temperature the probability of a many-SNAREpin configuration and membrane separation of closest approach is

| [1] |

Here includes steric and electrostatic interactions among SNAREpins, the complexation energy that depends on the degree of zippering and the stretching energy of the uncomplexed portions. denotes the SNAREpin-membrane steric and electrostatic interactions. The intermembrane energy , where is the van der Waals contribution calculated using experimental lipid bilayer Hamaker constants (29), is the electrostatic energy that depends on the density of charged lipids, and is the work done by short-range steric-hydration forces , where and are composition-weighted averages of measurements in pure lipid species (28, 29).

The MC simulations were run using a standard algorithm: Moves lowering energy were accepted, whereas those increasing energy were accepted with probability equal to the Boltzmann factor of Eq. 1. Starting from randomly configured half-zippered SNAREpins, Fig. 2A, following equilibration we calculated averages over ∼106 MC steps (SI Text, Fig. S3, and Table S3).

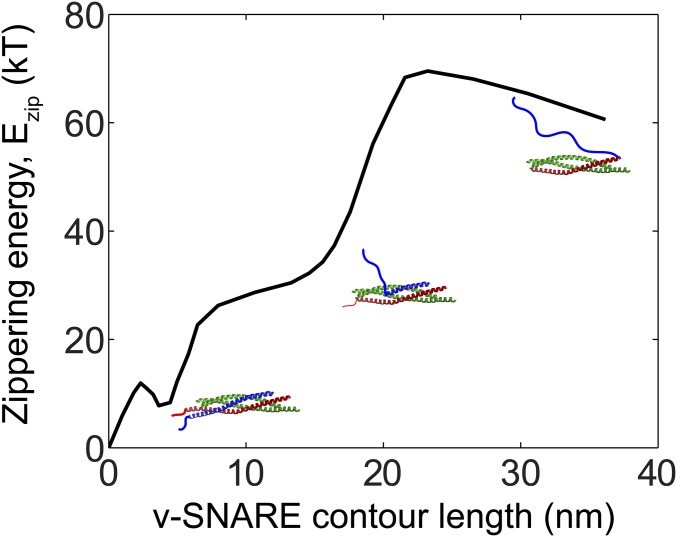

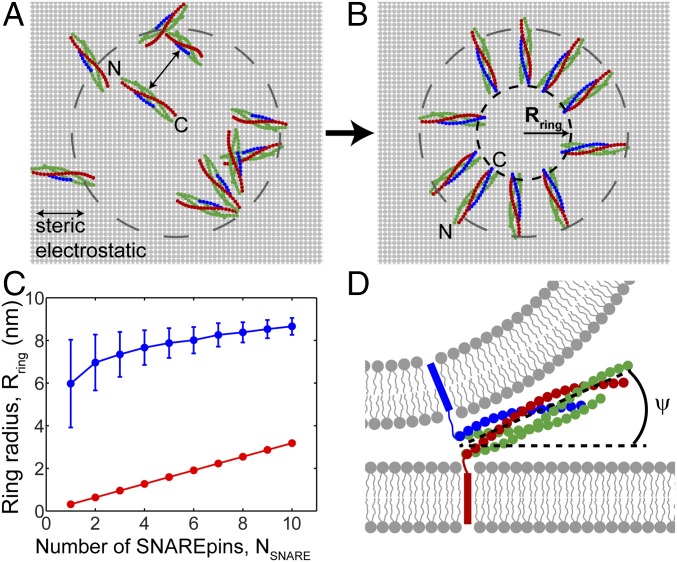

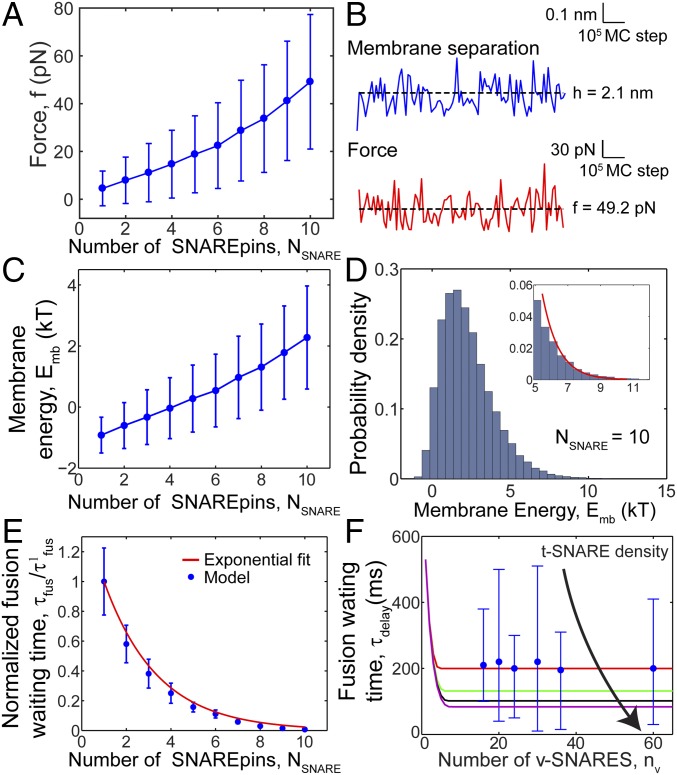

Fig. 2.

SNAREpins fully assemble and self-organize into a ring at the fusion site. Model parameter values as in Table S1, vesicle diameter 40 nm. (A) MC simulation, typical initial configuration. Half-zippered, randomly configured SNAREpins (top view, 10 SNAREpins). Dashed circle: projection of 40-nm diameter vesicle. (B) Typical configuration after equilibration. Independently of initial condition, SNARE motifs fully zipper and SNAREpins self-organize into a ring with inner radius . (C) Equilibrium SNAREpin ring radius versus number of SNAREpins, (blue), mean ± SD (averaged over ∼106 MC steps). For comparison, the minimum possible radius is shown for each value of (red), corresponding to shoulder-to-shoulder packing of the C-terminal SNAREpin ends. (D) Schematic of a typical side view of a SNAREpin belonging to an equilibrated ring of 10 SNAREpins. SNARE motifs fully assemble and LDs are unzipped. SNAREpins angle upward, with a mean angle relative to the planar membrane, which increases with the number of SNAREpins (Fig. S4B).

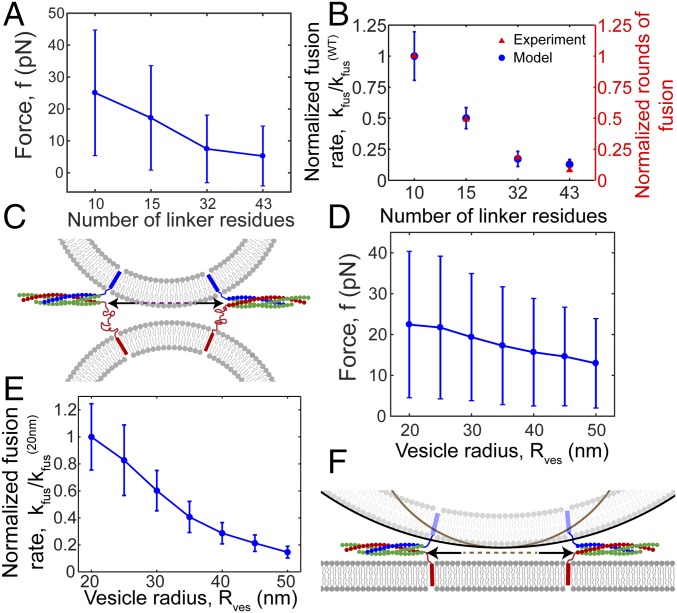

Fig. S3.

Model parameters used to label a state of the SNARE–membrane system. (A) Side view of a SNAREpin bridging a vesicle and a planar membrane. , membrane separation. , number of uncomplexed VAMP residues. , angle between the SNARE bundle and its projection on the planar membrane. , vertical distance between the center of the +8 layer of the complex and the planar membrane. (B) Projection of a SNARE bundle on the planar membrane. and denote, respectively, the radial and azimuthal angular coordinates of the center of the +8 layer of the complex. The origin of the cylindrical coordinates is on the target membrane (planar membrane or vesicle) at the point of closest approach to the vesicle. denotes the angle between at the center of the +8 layer and the axis of the projected SNARE bundle. C and N denote the C-terminal and N-terminal ends of the SNAREpin, respectively.

Table S3.

MC simulation

| Simulation parameter | Range |

For one move in the MC simulation, the table shows the amount by which each parameter defining the state of the SNAREpin–membrane system was changed. See Fig. S3 for definition of parameters. For a given MC move, the amount by which a given parameter was changed was chosen randomly from the range of values shown.

Membrane Fusion Waiting Time, .

We assumed fusion occurs when the intermembrane interaction energy exceeds a threshold, . Because this event is rare, the fusion rate , where is the probability that . Our procedure was as follows (for details, see later sections and SI Text). (i) From our MC simulations we measured the distribution of values and hence , which depended exponentially on , the number of SNAREpins. Thus, . (ii) We used this expression in a mathematical model of in vitro assays that measure docking-to-fusion delay times. Comparing with experiment (24), we determined the constant . This completed our calculation of fusion times. (iii) Importantly, the results of i, including , were insensitive to the assumed threshold . To estimate we used a scaling analysis for the “collision” time , the time spent within ∼1 kT of the fusion threshold during a large energy fluctuation, such that , where is known from i and ii. We then chose to reproduce this value of in simulations with .

SI Text

Coarse-Grained Representation of SNAREpins.

The coarse-grained model we used in this study describes the SNARE motifs (residues 7–83 and 141–204 of SNAP-25, residues 30–84 of VAMP, and residues 183–255 of syntaxin) and LDs (residues 85–94 of VAMP and residues 256–265 of syntaxin). The helices comprising the SNAREpins are represented as strands of beads (Fig. 1B), where each bead represents four assembled SNARE residues, corresponding to approximately one layer within the complex. The model SNARE complex consists of a stack of parallel layers. Each layer contains four beads, one from each motif, placed on the vertices of a square. The radius of the beads, nm, and the separation between beads within a layer (side length of the square nm) was tuned to reproduce the length (∼10 nm) and thickness (∼2 nm) of the cylindrically shaped SNARE bundles, measured using PyMOL software (48) with Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 3HD7 (31). Each layer is rotated ∼12° relative to its neighboring layers, to reproduce the twisting of the helices. Each bead is assigned a total charge equal to the net charge of the residues it represents at pH 7, where the charge on each atom was calculated from the PDB2PQR web server using the CHARMM force field (49) (Table S2). The charge is uniformly distributed on the surface of the bead.

The uncomplexed segments of the SNAREpins were assumed to be unstructured worm-like chains, with a persistence length nm, in the range of the typical values for polypeptides (7, 50). The structure of the TMDs is not explicitly described; each TMD is represented as a point in the membrane to which it belongs and acts as a spatial constraint that positions the C-terminal end of the LD to which it is attached. In MC simulations each TMD was positioned in its membrane at the location that minimizes the stretching energy of the uncomplexed part of its SNAREpin; in other words, the TMD is positioned at the point on the membrane that minimizes the length of the uncomplexed part.

SNARE zippering or unzipping occurs on a bead-by-bead basis: Within the core complex one unit of zippering is modeled as the conversion of four unstructured VAMP residues into a single VAMP bead in the SNARE complex, with energetics based on the zippering energy landscape measured with optical tweezers by Gao et al. (7) (Fig. S2). Unzipping is the reverse process. t-SNARE motifs remain structured. Zippering beyond the core complex into the LDs is modeled in a similar way, as structuring of the two LDs of VAMP and syntaxin that zipper together.

Intermembrane Energies and Membrane Compositions.

The intermembrane interaction energy at a given minimum separation (Fig. 1A) was calculated from the contributions of van der Waals, electrostatic, and short-ranged steric-hydration forces (29): The van der Waals contribution is written

| [S1] |

where is the Hamaker constant, approximately for lipid bilayers (29). is a geometrical factor that depends on the curvature of the membranes, equal to or for the vesicle–planar membrane or vesicle–vesicle geometries, respectively, where is the vesicle radius (29). The electrostatic interaction between the membranes is

| [S2] |

Here is the Debye screening length, 0.8 nm for a monovalent physiological salt concentration of 0.15 M (29). The factor is calculated from the surface potential of the membranes, . For monovalent electrolytes at C, is given by

| [S3] |

where is in units of millivolts (29). The surface potential is related to the surface charge density, , which itself is determined from the concentration of charged lipids in the membranes according to the Graham eqation (29):

| [S4] |

The steric-hydration interaction energies for vesicle–planar membrane and vesicle–vesicle systems are calculated from experimentally measured steric-hydration pressures between planar membranes, (28), as follows. First, the pressure between the two planar surfaces was converted to an interaction energy per unit area by calculating the work done to bring the membranes to a separation from infinity. Second, the total force between curved membranes (vesicle–vesicle or vesicle–planar membrane systems) was calculated from the interaction energies of planar membranes using the Derjaguin approximation (29). Third, the calculated force between the curved membranes was converted to the interaction energy by calculating the work done to bring them to separation , giving

| [S5] |

Values of and have been reported for various membrane compositions; is in the range 0.1–0.3 nm for all membranes considered, whereas the prefactor depends on the lipid head group (28). For the membrane compositions we used in this study (discussed below) we calculated the composition weighted average of the prefactor and steric-hydration decay length , based on the measured values for pure substances.

In this study we assumed a lipid composition 82% phosphatidylcholine (PC), 3% phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and 15% phosphatidylserine (PS), mimicking a typical composition used for in vitro assays (11).

Inter-SNAREpin Interaction Energies.

The interaction energy between SNAREpins was calculated by summing the interactions of all beads with one another. Two beads interact via a hard core potential for center-to-center separations less than the bead diameter, and electrostatically for larger separations. At a bead–bead separation , the interaction energy of two beads is taken as

| [S6] |

This expression is the double-layer interaction energy in aqueous solution, taking the charge on each bead to be uniformly distributed on the bead surface (29). The interaction parameter for each pair of beads is determined as the geometric average of the values calculated for bead pairs of similar charge (29), each calculated similarly to from the assigned charges (Table S2) using Eqs. S3 and S4: . Positive denotes repulsion between beads of like charge, whereas negative values denote attraction between oppositely charged beads.

Membrane–SNAREpin Interaction Energies.

The net interaction energy between the SNAREpins in the cluster and the membranes was calculated by summing the interactions of all beads of all SNAREpins with both membranes. The interaction energy of a bead belonging to a SNAREpin with a vesicle whose center is a distance d from the bead is given, similarly to Eq. S6, by (29):

| [S7] |

The interaction parameter is the geometric average of the values calculated for the interaction of two similarly charged membrane surfaces and two similarly charged SNARE beads (29): . The above expression describes an electrostatic interaction together with a hard core repulsion if overlap occurs. Similarly, the energy of interaction between a SNAREpin bead and a planar membrane at a separation of d is given by

| [S8] |

Stretching Energy of Uncomplexed Segments of SNAREpins.

The uncomplexed portion of a SNAREpin connecting the motif to the TMD was assumed unstructured and described using the worm-like chain model (7, 50). Accordingly, the energy stored in these regions is

| [S9] |

Here, is the persistence length of the unstructured SNAREs, taken to be 0.6 nm, in the range of values for typical polypeptides (7), is the contour length of the uncomplexed SNAREs calculated from the number of uncomplexed residues assuming each residue contributes 0.365 nm to the total contour length (7), and is the end-to-end distance of the uncomplexed SNARE segment, namely the distance from the TMD to the C-terminal VAMP or syntaxin bead in the complex. As described above, the TMDs are positioned on the membrane surface so as to minimize the above stretching energy of the unstructured portions. The N-terminal ends of the TMDs were assumed to be located at a depth 1 nm in the membranes, roughly coinciding with the beginning of the tail region of the lipid bilayer (51).

Zippering Energy of SNAREpins.

The zippering energy of the SNAREpins was calculated from the SNARE zippering energy landscape determined by Gao et al. (7) using optical tweezers, based on the number of uncomplexed SNARE residues (Fig. S2). The landscape shown in Fig. S2 is an interpolation among 25 points from the landscape reported by Gao et al. (7). The contour lengths of the SNARE complex between the C-termini of VAMP and syntaxin linkers, roughly equal to sum of the contour lengths of the VAMP and syntaxin linkers and the thickness of the SNARE bundle, used as a reaction coordinate in Gao et al. (7), were converted to VAMP contour lengths for convenience. In our simulations, for each SNAREpin the contour length of uncomplexed VAMP is calculated, based on the SNAREpin’s degree of zippering, and a corresponding zippering energy is read from Fig. S2.

MC Simulation.

An MC simulation was used to calculate the quantitative consequences of the model once the SNAREpins have equilibrated. In particular, it was used to compute the equilibrium distribution of membrane separations, pressures, and energies and the SNAREpin configurations. half-zippered SNAREpins were generated with random configurations within the space between the membranes whose minimum separation is (discussed below). The state of each SNAREpin was defined by the state vector : denotes the number of uncomplexed VAMP residues (the number of uncomplexed syntaxin residues was calculated from , assuming t-SNARE motifs remain assembled); , , and , respectively, describe the radial, azimuthal, and vertical coordinates of the center of the +8 layer of the SNARE complex using cylindrical coordinates, where the origin is taken to lie on the target membrane (planar or vesicle) at the point of closest approach to the vesicle; denotes the angle between the vector and the projection of the SNARE bundle onto the plane; and denotes the angle between the SNARE bundle and its projection onto the plane (Fig. S3). The system was then evolved using a total of seven move types: one membrane move that changes and six SNAREpin moves that change any of the six parameters describing the state of a SNAREpin selected at random from the available SNAREpins. If a move would increase the energy, the move is accepted with a probability given by the Boltzmann factor from Eq. 1; if the move would decrease energy, the move is accepted. The following were prohibited: moves that resulted in configurations with overlaps between SNAREpins, or between membranes and SNAREpins, or moves that resulted in more than 100% stretching of the uncomplexed portions of the SNAREs. The range of the allowed moves (Table S3) was chosen to give an acceptance probability ∼0.5.

For each MC simulation the system was evolved from a random initial configuration (discussed below) using a total of MC steps. We divided the total steps into windows of 100 steps and calculated the mean of the total energy (sum of all energies in the system) in each window. We then defined the system to have equilibrated during the first window whose mean energy was within 2 kT of the mean energy for the full simulation of steps. All statistics presented in the main text were calculated from measurements made after this window defining the onset of equilibrium had been reached. For the simulations with the most SNAREpins, that needed the longest equilibration time, this occurred after ∼ steps.

Random initial configuration.

To generate the random initial configuration for a simulation, a membrane separation was first selected at random, in the range of 2–4.5 nm. The lower limit, 2 nm, is the thickness of a SNARE complex, and the upper limit of 4.5 nm is the equilibrium intermembrane separation in the absence of SNAREpins. Then half-zippered SNAREpins were placed within the space between the membranes iteratively, by defining SNAREpin parameters that satisfied the constraint imposed by the membranes. For each iteration the configuration was rejected if inter-SNAREpin or SNAREpin–membrane overlaps occurred or if uncomplexed portions of the SNAREs were overstretched.

Equilibration time: justification for the MC approach.

Because we used MC sampling, the pressures, energies, fusion waiting times, and other properties that we calculate in this study describe the equilibrium properties of the cluster of SNAREpins. The validity of our calculations thus rests on the assumption that a cluster has sufficient time to equilibrate before fusion occurs. To assess this issue, consider the timescales of the various processes involved in equilibration. (i) The timescale for SNAREpin zippering/unzipping between membranes is estimated to be , because SNAREpins zipper within in solution (7) and the presence of membranes may retard these processes by a factor of ∼10 (14). (ii) The timescale for SNAREpin motions between the membranes is limited by TMD motions, because TMDs suffer a larger drag from the membranes than the drag experienced by SNARE bundles in solution. Consider one fully assembled SNAREpin connecting a 40-nm-diameter vesicle [a typical size for synaptic vesicles (34)] and a planar membrane. The time for a TMD to diffuse the distance to a neighboring TMD in a cluster of SNAREpins is roughly (Fig. 2C) for = 6, a typical number of SNAREpins required for fusion. Here is the TMD diffusivity within the lipid bilayer, which we take to be the diffusivity of t-SNAREs measured in bilayers, (47), is the thickness of the SNARE bundle, and the factor 2 accounts for the fact that a SNAREpin has two TMDs. (iii) The collision time between vesicle and planar membrane is of order , where is a typical displacement of the docked vesicle and is the diffusivity of the vesicle in solution estimated using Einstein’s relation.

Thus, the processes i–iii above occur much more rapidly than does fusion, the typical fusion timescales being milliseconds or greater (24). We conclude that the SNARE–membrane system we study will usually equilibrate well before fusion occurs.

Calculation of the Vesicle–Planar Membrane or Vesicle–Vesicle Contact Force.

We calculated the contact force between the planar membrane and the vesicle as follows. We define this force to be the force exerted by the planar membrane (taken as infinitely large) on a small portion of the surface of the vesicle near the point on the vesicle that is closest to the membrane. This portion of the vesicle surface, which we call the contact region, is taken to be a spherical cap centered on the point of closest approach. The size of the cap was defined to be such that the force exerted on the cap is 90% of the total force exerted on the entire vesicle by the planar membrane. In other words, the cap size is chosen so that the force it experiences is changing very little as the cap size increases.

This contact force has contributions from the steric-hydration, the electrostatic, and the van der Waals forces. We calculate the force as follows. We partition the surface of the spherical cap into rings of different radii that are approximated as being parallel to the planar bilayer and are at distances from the planar bilayer. Here is the height of the spherical cap and the separation between vesicle and membrane at the point of closest approach. We then sum the forces exerted by the bilayer on each ring to give the total force . A ring of infinitesimal thickness is of area and experiences the same normal force per unit area as two infinite planar surfaces . Thus, the total force is

| [S10] |

where is the area of the spherical cap with . The force per unit area is the sum from three contributions as follows:

| [S11] |

The force per unit area due to the three interactions is given in ref. 28:

| [S12] |

We define the contact region as that cap that is large enough to experience 90% of the total force between the entire vesicle and the planar membrane. Thus, we define the contact force and the area of contact as

| [S13] |

where the angular brackets represent averages calculated over one MC simulation. We applied these formulae in the simulation with six SNAREs straddling a vesicle of radius 20 nm and a planar bilayer (corresponding to the simulation in Fig. 4A) to obtain . We then used the same area of contact for all simulations (Figs. 4 A and B and 5 A and D).

Fig. 4.

Membrane force, energy, and rate of fusion increase with number of SNAREpins. Model results, based on 106 MC step simulations per plotted point. Parameters as in Table S1, vesicle diameter 40 nm. (A) Force between membranes versus number of SNAREpins. The force is the total exerted by the planar membrane on a small spherical cap of area centered on the vesicle contact point (SI Text). Mean values ± SD. (B) MC sequences for membrane separation (blue) and force (red) for a 10-SNAREpin ring. Dashed lines indicate mean values. (C) Membrane energy versus number of SNAREpins. Mean values ± SD. (D) Distribution of membrane energies for 10 SNAREpins. Red curve: exponential fit to tail ( 5.4 kT). Bin width: 0.2 kT. (E) Predicted relative waiting time for fusion versus number of SNAREpins. Total simulation time was divided into 10 bins and waiting times were calculated for each bin. Plotted points: mean values ± SD. The best-fit exponential is , Eq. 2 (). (F) Fusion of v-SNARE reconstituted SUVs with t-SNARE reconstituted SBLs: docking-to-fusion delay time versus number of v-SNAREs. Blue discs: experiments, ref. 24. Solid curves: model predictions for different SBL t-SNARE densities (red, 48 t-SNAREs/μm2, as in ref. 24; green, 100 t-SNAREs/μm2; black, 150 t-SNAREs/μm2; purple, 200 t-SNAREs/μm2). In all cases, 50% of t-SNAREs were assumed mobile (24), with diffusivity in the SBL (47).

Fig. 5.

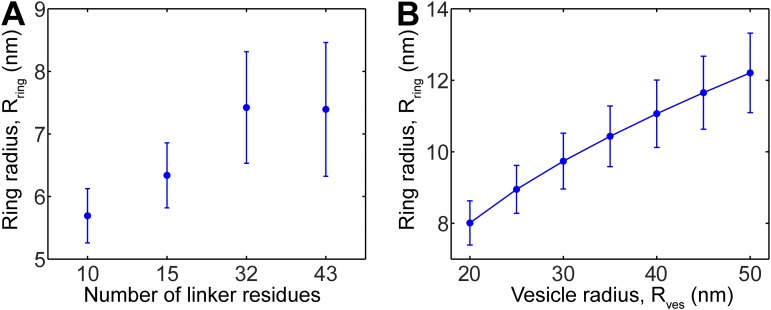

Rate of fusion decreases with increasing linker length and vesicle size. Model results, based on 106 MC step simulations per plotted point. Forces are defined as in Fig. 4. Parameters as in Table S1. (A and B) Simulations of two 40-nm diameter vesicles bridged by six SNAREpins, mimicking mutant t-SNARE LD experiments of ref. 11. (A) Force between membranes versus number of residues in t-SNARE LDs. Mean values ± SD. (B) Fusion rates relative to wild-type rate, versus number of residues in t-SNARE LDs. Model predictions (blue discs). Total simulation time was divided into 10 bins, and waiting times were calculated for each bin. Plotted points: mean values ± SD. Experiments of ref. 11 (red triangles): estimated number of rounds of fusion per vesicle, a measure of the rate of fusion. (C) For a given membrane separation, LD extension allows the SNAREpin ring to expand (arrows), reducing entropic forces and lowering fusion rates (schematic). Dashed line indicates inner ring diameter with wild type LDs. (D and E) Simulations of vesicle and planar membrane bridged by six SNAREpins. (D) Force versus vesicle radius. Mean values ± SD. (E) Fusion rates, relative to rate with 20-nm-radius vesicles, versus vesicle radius, determined similarly to B. (F) For a given membrane separation, a larger vesicle allows the SNAREpin ring to expand (arrows), reducing entropic forces and lowering fusion rates (schematic). Dashed line indicates inner ring diameter for the smaller vesicle.

A similar procedure was used to calculate the force between two vesicles. In the simulation of Fig. 5A where we calculated between two identical vesicles, we used Eq. S10 with a modified prefactor, . This is because a ring at a height from the vesicle as measured along the line of closest approach has an area in this configuration. The general formula for any vesicle–vesicle configuration is obtained by replacing the in Eq. S10 by , where are the radii of the participating vesicles (28). One of these is set to when one vesicle is replaced by a planar bilayer. Eq. S10 is exact in the vesicle–planar membrane configuration and becomes the Derjaguin approximation in the vesicle–vesicle configuration, which is a good approximation for (28).

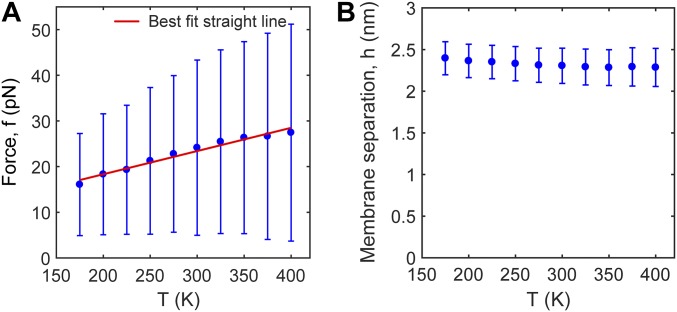

Purely Entropic Forces Between Membranes Depend Linearly on Temperature.

In this subsection we consider the forces between the vesicle and planar membranes (or between the two vesicle membranes in the case of vesicle–vesicle fusion). These forces have two components: (i) the force, , exerted by the SNAREpin–membrane system that tends to pull the membranes closer together and (ii) the membrane-membrane contact force at the point of closest approach (which is dominated by the hydration force) that tends to push the membranes apart. The corresponding free energies are (i) and (ii) , such that the forces are derivatives of these free energies, and .

We now show that if the force exerted by the SNAREpin–membrane system is entropic, then the mean contact force is approximately linearly dependent on temperature, . Here denotes the average over all separations h of the two membranes at the point of closest approach (Fig. 1A).

First, if is of entropic origin, the energy of the SNAREpin–membrane system depends only on temperature T (because the interactions are hard core) and its entropy can be written , where is the contribution that depends on the membrane and SNARE spatial configurations and is the contribution from translational and rotational velocities. Thus, we can write . Hence depends linearly on temperature.

Second, we use the fact that in equilibrium, when the vesicle membrane–planar membrane–SNAREpin system has had time to visit all SNARE configurations and all values of , the mean total force acting on the vesicle (say) vanishes: . Thus, . Thus, we have

| [S14] |

Third, let us assume that the probability distribution of values is independent of . Because is also independent of , it follows that

| [S15] |

depends linearly on temperature .

In the present case, we find that is indeed very weakly dependent on , as reflected by the weak dependence on of the mean value and the dispersion (Fig. S7B). Thus, the mean contact force will be linear in if the SNAREpin–membrane force is entropic. Hence the linearity of the dependence of on temperature is a test of the entropic nature of the SNAREpin-membrane force.

Fig. S7.

Mean contact force between membranes depends linearly on simulation temperature. Model results, based on 106 MC step simulations per plotted point. Parameters as in Table S1. Results are for a 20-nm-radius vesicle and a planar membrane, bridged by six SNAREpins. Forces plotted are total forces on a spherical cap, as described in Fig. 4 of main text. (A) Force between membranes versus simulation temperature. Plotted points (blue) show mean ± SD of the force. Red line is best linear fit (, ). (B) Membrane separation versus simulation temperature. Values are mean ± SD. The mean and the SD depend very weakly on temperature, showing that the probability distribution of membrane separations, , is weakly dependent on temperature. Given that the membranes are pulled together by SNARE–membrane and membrane–membrane forces of entropic origin, the contact force will depend linearly on temperature when is independent of temperature.

Measurement of the Force Between Membranes As a Function of Temperature.

In the previous subsection we showed that if the force exerted by the SNAREpin–membrane system is entropic in nature (the principal hypothesis of our work), then the mean contact force between the membranes will depend linearly on temperature, . Thus, to test the degree to which the forces between the membranes that emerge from our simulations are of entropic origin, we measured the dependence of this force on simulation temperature. We found that the dependence was indeed close to linear over a wide range of temperatures, (Fig. S7A).

We stress that this procedure serves only as a theoretical test of the entropic origin of the driving forces for fusion; we do not, of course, predict linear T dependence of these forces in the real world, because protein characteristics and many other cellular processes will depend on temperature in complex ways far beyond the scope of our model.

Estimate of Vesicle Deformation by SNARE-Mediated Entropic Forces.

Throughout this study for simplicity we assumed that the vesicle and the plasma membranes do not deform (i.e., the former remains spherical and the latter planar). Here we assess this approximation by estimating the deformations produced by the entropic forces that push the membranes together and induce fusion in our model (Fig. 4 A and B). These forces will presumably distort the spherical vesicle to have a lower (higher) diameter in the direction perpendicular to (parallel to) the plasma membrane and will locally flatten the vesicle in a small region where it contacts the plasma membrane. Below, we calculate the deformation from a force balance between membrane tension, membrane bending, and the entropic force.

For simplicity we treat the deformed vesicle as an oblate ellipsoid (we expect this to yield a good approximate value for the deformation, although an exact calculation would respect the exact shape, including a flattened portion at the contact point). The volume of the vesicle, initially a sphere of radius , is assumed unaltered by the deformation (i.e., no leakage occurs). Squeezing the vesicle by a distance means that the short axis of the ellipsoidal vesicle has length . Given the volume is constant, it can be shown that the long axis then has length .

What is the energy increase due to this deformation? There are two effects. First, it can be shown that the deformation of the vesicle increases the oblate ellipsoid area by an amount to leading order in . This area increase is resisted by membrane tension, with a corresponding energy increase is , where and are the tension and area of the undeformed vesicle, respectively, and is the membrane 2D stretching modulus. This gives . The associated force resisting the deformation is .

Second, deformation of the sphere increases the total bending energy. The bending energy is given by , where is the membrane bending modulus and is the mean curvature of the membrane surface. Evaluating the integrals gives to leading order in . The associated resisting force is . The total resisting force is thus

| [S16] |

Using our simulations we calculated entropic forces in the range (Fig. 4A). Equating these forces to above, and using a typical value and experimentally measured values , , (34, 52), yields vesicle deformations , small deformations relative to the vesicle diameter of 40 nm. These will lead to a flattened portion of the vesicle at the contact point of area δA, and local pressures in the range .

In summary, the vesicle deformations are small, supporting the validity of the undeformable membrane approximation used in this work to calculate forces and fusion times.

Estimation of Fusion Waiting Times.

We assumed fusion occurs when the intermembrane interaction energy exceeds a critical threshold for fusion, . Using the distribution of membrane energies calculated from MC simulations (Fig. 4D), this yields the relative fusion times, . Here is the probability that a fluctuation occurs such that . We calculated from an exponential fit to the tail of the energy distribution, :

| [S17] |

where is a numerical constant that we determined from fitting. The form of the fitting function was chosen based on the following. For large the probability of a many-SNAREpin configuration and a membrane separation (Eq. 1) is dominated by membrane energies, . Further, for large (i.e., for small h), is dominated by steric-hydration forces and thus depends exponentially on (Eq. S5). Thus,

| [S18] |

Thus, for high values of the distribution has exponential form.

Our procedure was to determine by fitting an exponential to the tail of the energy distribution calculated from our MC simulations. This yielded the relative fusion times, . For this fitting procedure we defined the tail of the distribution to be those energy values such that (for we used an upper bound of 0.05), where is the survival function: , where is the cumulative distribution function, that is, the total probability of any energy ≤ . We chose this range of values to eliminate data from our MC simulations corresponding to very high energies for which fluctuations are large due to small sample numbers, and to eliminate data corresponding to energies so small that the distribution deviates significantly from an exponential form.

Modeling Docking-to-Fusion Delay Times in Assays That Measure Fusion of Vesicles with SBLs.

Our model of SNARE-mediated fusion predicts that the waiting time for fusion decreases with the number of SNAREpins assembled at the fusion site, in a situation where this number has a fixed value, . The result, Eq. 2, is the waiting time as a function of , the function . However, in experimental SUV–SBL fusion assays with single fusion event resolution steadily increases as t-SNAREs are recruited to the location of a docked SUV reconstituted with v-SNAREs. Here we estimate the docking-to-fusion delay time in such experiments, , by combining our present results, Eq. 2, with a simplified approximate analysis of the recruitment kinetics of t-SNAREs within the SBL. According to Eq. 2 the rate of vesicle fusion is

| [S19] |

where . The probability that the vesicle is unfused at time t is

| [S20] |

Defining the characteristic delay time as the time at which , we have

| [S21] |

In Eqs. S19–S21 and are functions of time t. When the vesicle docks the first SNAREpin is formed, and thereafter t-SNAREs are assumed recruited to the fusion site by lateral diffusion within the SBL. Thus,

| [S22] |

where is an approximate expression for the mean time to recruit one t-SNARE (24). Here and denote the number density and diffusivity of the t-SNAREs in the SBL, respectively [ counts only the mobile fraction, in the case where some t-SNAREs are immobilized (24)] and is a numerical constant. Eq. S22 and the expression for T are simplified expressions that neglect corrections with logarithmic time dependence (see ref. 24). However, they allow us to derive explicit approximate expressions for .

Let us now solve Eq. S21 in two limiting cases.

-

i)

Small , . Then Eq. S21 gives

| [S23] |

or

| [S24] |

Now for small the fusion time if all SNAREpins were assembled is much greater than the time to recruit t-SNAREs, . Thus, , so the first two terms in Eq. S24 are small compared with unity. The solution to Eq. S24 is thus

| [S25] |

Thus, for small , has the same exponential decay as the fusion delay time for already-assembled SNAREpins, Eq. 2 of the main text.

-

ii)

Large , . In this case Eq. S21 is written

| [S26] |

Thus

| [S27] |

where is the time to recruit t-SNAREs. This expression for is independent of , that is, reaches a plateau for large .

An approximate expression for the crossover value separating the two regimes of small and large is obtained by equating the two asymptotic forms, , giving .

Fitting Eq. S27 to the experimental plateau time measured by Karatekin et al. (24), we estimated ∼530 ms after taking based on the t-SNARE density used in these experiments, and assuming that only half of the t-SNAREs are mobile (24).

We then used Eq. S27 and the solution of Eq. S24 (taking ), together with Eq. 2 of the main text, to plot the predicted delay time versus curves of Fig. 4F.

Estimation of Fusion Energy.

We used the fusion waiting time with one SNAREpin estimated above, , to estimate the fusion energy, . Using , where is a characteristic “collision” time, together with Eq. S17 we have

| [S28] |

Here is the fitting parameter determined from simulations by fitting an exponential to the tail of the energy distribution with one SNAREpin (Eq. S17). Thus, can be estimated if the collision time is known. This timescale represents the amount of time for which the membranes will continue to have an energy within ∼1 kT of the fusion energy threshold , should a fluctuation happen to bring them close enough together to have such a high energy. For these high values of energy, or equivalently small values of h, steric-hydration forces that decay exponentially with are dominant (Eq. S5). Thus, is the time after which hydration forces will push the membranes apart to a separation h that is increased by an amount δ, such that the energy is reduced by an amount of 1 kT. From the fluctuation-dissipation theorem this can be shown to be equivalent to the diffusion time corresponding to δ, that is, , where is the estimated diffusivity of a 40-nm-diameter vesicle. Now, from Eq. S5, we have , assuming . Thus, Eq. S28 yields an expression obeyed by ,

| [S29] |

Solving Eq. S29, we find kT.

Results

SNAREpins Self-Organize into a Ring at the Fusion Site.

We ran simulations with 1–10 SNAREpins, the range of reported requirements for small vesicle fusion (22–25). The initially half-zippered and randomly configured SNAREpins bridged a planar target membrane and a vesicle (Fig. 1 and Table S1). The vesicle diameter is 40 nm, typical of synaptic vesicles (34), for all results except where it is otherwise stated.

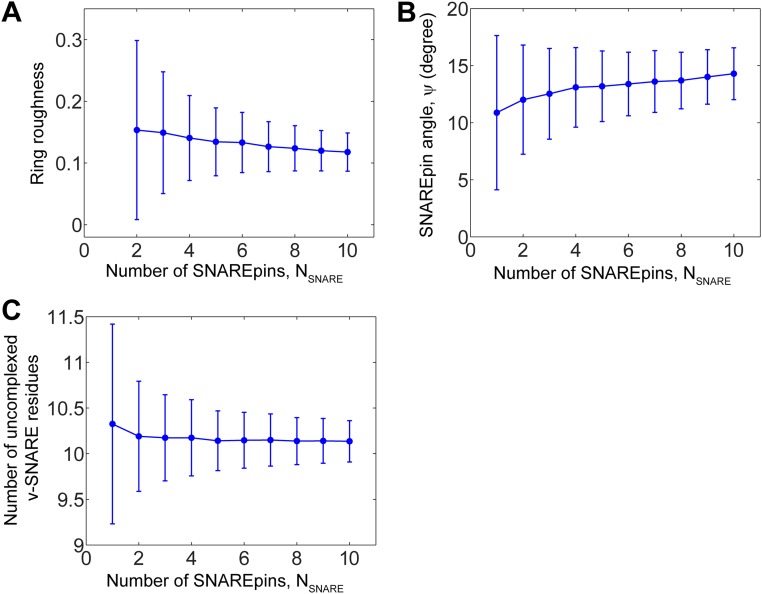

Independently of initial conditions and number, the SNAREpins fully assembled and organized into a ring centered on the point of closest membrane approach (Fig. 2 A and B). SNARE bundles became outwardly oriented, their C-terminal ends forming an inner circle whose radius increased from 6 ± 2 nm (mean ± SD) for one SNAREpin to 8.6 ± 0.4 with 10 SNAREpins (Fig. 2C). Within a given ring, the rms relative fluctuations of C-terminal locations about a perfect circle were small, decreasing from ∼15% for two SNAREpins to ∼12% for 10 SNAREpins (Fig. S4A). Rings tilted out of plane (Fig. 2D): The angle between a SNARE bundle and the planar membrane increased from 10.9± 6.8° (one SNAREpin) to 14.3 ± 2.3° (10 SNAREpins) (Fig. S4B).

Fig. S4.

Roughness of a SNAREpin ring, orientation of a SNAREpin, and zippering degree: dependence on number of SNAREpins. Model results, based on 106 MC step simulation per plotted point. Parameters as in Table S1, 40-nm-diameter vesicle. Plotted points are mean ± SD. (A) Equilibrium SNAREpin ring roughness, defined as the rms relative deviations of locations of the SNAREpin C-terminal ends from a perfect inner circle, versus number of SNAREpins. (B) Angle made by a SNARE bundle with its projection on the planar membrane, (Fig. S3) versus number of SNAREpins. (C) Number of uncomplexed v-SNARE residues versus number of SNAREpins.

Thus, SNAREpins self-organize into a well-marshaled ring with small positional fluctuations that decrease as the number of SNAREs increases. Ring formation clears a central hole where the membrane surfaces can meet and potentially fuse (Fig. 2B); our results argue against the suggestion that with flexible LDs SNAREpins could accumulate at the point of closest membrane approach and even prohibit fusion (15).

Entropic Forces Organize SNAREpins into Expanded Rings.

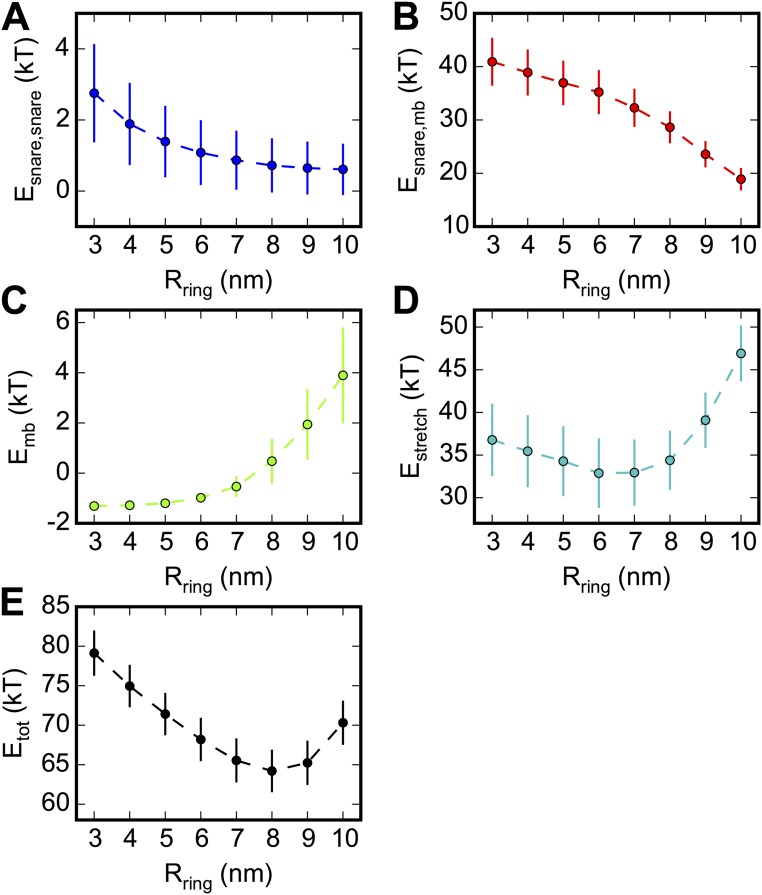

To explore the mechanism that creates the ring and sets its size, we measured the contributions to the total energy in simulations with the ring radius artificially constrained. With increasing ring size, the SNAREpin–SNAREpin and SNAREpin–membrane energies decreased (Fig. S5 A and B). Because these are short-ranged electrostatic interactions that enforce nonintersection, we conclude that larger rings have more configurational entropy. Thus, entropic forces favor ring expansion. However, expansion unzips SNARE complexes, pulls the membranes closer together, or (for sufficiently large rings) stretches the LDs (Fig. S5 C and D). These effects cost energy, and the equilibrium ring size reflects a balance of these effects with entropic expansion forces (Fig. S5E).

Fig. S5.

Contributions to the energy of a SNAREpin cluster and the membranes bridged by the cluster as a function of cluster size. Model results, based on MC step simulations per plotted point. Parameters as in Table S1. Results are for a 20-nm-radius vesicle and a planar membrane, bridged by six SNAREpins. Plotted points show mean ± SD of the total energy. To reveal the dependence of different energy contributions versus ring size, for each value of the simulation was run with the constraint that the inner ring radius was equal to , that is, the radial location of the C-terminal ends of the SNAREpins was fixed (Fig. 2B). (A and B) The interaction energies between SNAREpins (A) and between SNAREpins and membranes (B) are electrostatic and steadily decrease with increasing ring size. This reflects the increased entropy of larger rings, in which the separation between SNAREpins and between SNAREpins and membranes is greater. The greater mean separation implies less contact time and consequently lower electrostatic energy. (C) Membrane energy, by contrast, increases as the membranes are forced closer together with increasing ring radius (Fig. 3 B and C). (D) The stretching energy of the LDs initially decreases with ring size due to decreasing SNAREpin–membrane electrostatic repulsions. For larger rings hydrostatic repulsions prevent the membranes from being pulled any closer, and linkers are once again significantly stretched due to the geometric constraint (Fig. 3A). (E) The total energy (sum of A–D) has a minimum close to the equilibrium ring size for six SNAREpins, ∼8 nm (Fig. 2C).

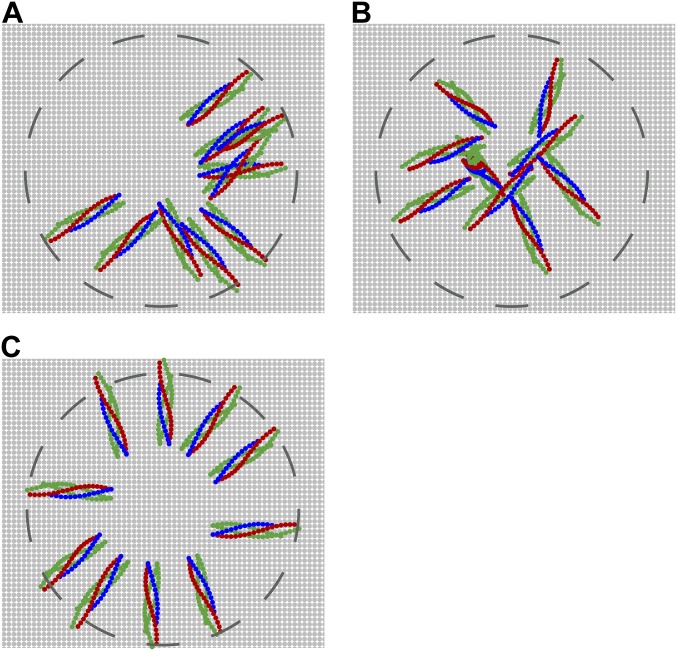

Thus, we find that radial alignment in a ring maximizes the orientational and translational entropy by avoiding intersections. Larger rings increase entropy by (i) increasing the separation between SNAREpins and (ii) increasing polar angular entropy, a membrane curvature effect (Fig. 3A). With more SNAREpins crowding increases, entropic forces increase, and rings expand. Artificial removal of inter-SNAREpin or SNAREpin–membrane interactions severely disrupted the ring organization (Fig. S6).

Fig. 3.

Entropic forces expand SNAREpin rings and pull membranes together. (A) SNAREpin rings expand entropically (right-pointing arrow), due to steric-electrostatic inter-SNAREpin and SNAREpin–membrane interactions (schematic). Entropy favors the expanded ring because SNAREpins are more spaced and, on account of vesicle curvature, have greater polar angular orientational entropy (Right). Since the vesicle has curvature and linker lengths are almost constant, ring expansion is geometrically coupled to reduced membrane separation so that the vesicle exerts force on the planar membrane (downward-pointing arrow). (B) Fluctuations in ring size and membrane separation are strongly correlated. MC simulation of a 10-SNAREpin ring, ∼106 MC moves. Model parameters as in Table S1, vesicle diameter 40 nm. Bin width: 0.1 nm. Mean ± SD. (C) Mean membrane separation decreases as mean ring size increases. Each point shows mean values for a 106 MC step simulation with a different number of SNAREpins. Model parameters and vesicle size as for B.

Fig. S6.

Self-organization of SNAREpins into circular clusters requires both SNAREpin–membrane and SNAREpin–SNAREpin interactions. Model parameter values as in Table S1. (A) Typical equilibrium snapshot of a simulation, with SNAREpin–membrane interactions switched off. Top view, 10 SNAREpins. Dashed circle shows projection of the 40-nm-diameter vesicle. (B) Typical equilibrium snapshot of a simulation with inter-SNAREpin interactions switched off. (C) Typical equilibrium snapshot of a “wild-type” simulation, with both energy terms incorporated.

SNARE Motifs Fully Assemble but LDs Are Unzipped.

In the ring of SNAREpins, the SNARE motifs were fully assembled, whereas the LDs [VAMP residues 85–94 and syntaxin residues 256–265 (31)] remained unstructured. More precisely, the mean number of VAMP/syntaxin uncomplexed residues between the TMD and the fully complexed part of the SNAREpin remained close to 10, decreasing from 10.3 ± 1.1 (one SNAREpin) to 10.1 ± 0.2 (10 SNAREpins) (Fig. S4C). This behavior reflects the net free energy zippering profile, which sums (i) the raw profile for an isolated SNARE complex measured in ref. 7 with a ∼5-kT energy barrier for the onset of linker zippering (Fig. S2) and (ii) a second contribution, extremely large for large degrees of zippering, due to the membranes and other SNAREpins. The net profile has a minimum where the LDs are fully unzipped.

Physically, complete zippering is prohibited because this would overlap the LD and membranes. Even partial zippering is disfavored, because if the 5-kT barrier were to be overcome the linkers would be substantially shortened and the SNAREpin C-terminal end forced to lie close to the point of closest approach of the membranes, incurring a high entropic penalty.

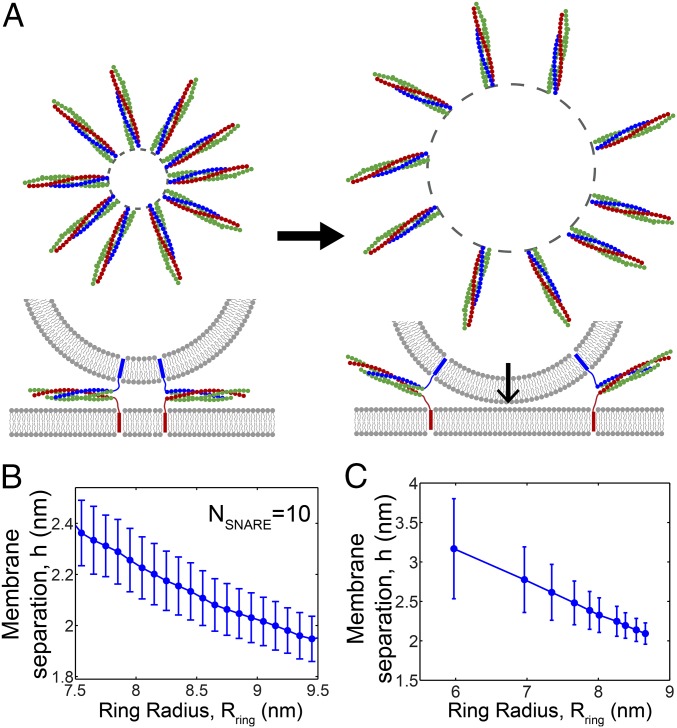

Entropically Driven Expansion of SNAREpin Rings Pulls Membranes Together.

Expansion of the SNAREpin ring, powered by entropic forces, pulled the membranes together. This effect was evident in the statistics of a given ring: Fluctuations to greater radii were highly correlated with fluctuations to smaller membrane separations (Fig. 3B). Similarly, with more SNAREpins the mean ring radius increased and the mean minimum membrane separation decreased, from 3.2 ± 0.6 nm with one SNAREpin to 2.1 ± 0.1 nm with 10 SNAREpins (Fig. 3C).

The origin of this effect lies in the vesicle curvature and the fact that the membrane separation at the C-terminal inner circle is approximately fixed, equal to the sum of the unzipped linker lengths plus SNAREpin thickness (Fig. 3A). Thus, inner circle expansion forces the vesicle closer to the target membrane. This constraint would be weakened either by linker stretching or by unzipping of the SNARE complex, but neither process occurred substantially due to the high energy costs of unzipping (∼4 kT per layer) and of linker stretching (e.g., ∼1–2 kT per SNAREpin to expand an 8-nm ring by 1 nm at fixed ).

SNAREpin Rings Push Membranes Together with High Forces and Generate Large Fluctuations in Membrane Energy.

Entropically driven ring expansion pushed the membranes together with a force that increased from ∼5–49 pN as the number of SNAREpins increased from 1 to 10 (Fig. 4A). As expected for a force of entropic origin, the mean value had an approximately linear dependence on simulation temperature (SI Text and Fig. S7). We estimate these forces would slightly flatten the vesicle at the contact point, giving pressures ∼1 atm or less (SI Text).

The forces fluctuated significantly about the mean (Fig. 4B), due to fluctuations in membrane separation and the exponential dependence on of the repulsive steric-hydration and electrostatic forces dominant at these separations (). Force fluctuations were accompanied by large fluctuations in membrane energy ( of Eq. 1). The mean energy increased to ∼2.3 kT for a 10-SNAREpin ring (Fig. 4C), and the energies followed a broad distribution with an exponential tail (Fig. 4D).

Fusion Can Occur with Any Number of SNAREs but Is Faster with More SNAREs.

Next, we used our model to show that each additional SNAREpin increases the fusion rate ∼1.6-fold. It is commonly assumed that fusion requires a certain energy. Accordingly, we assume fusion occurs if a fluctuation brings the membrane energy to a threshold, , which turns out to greatly exceed the mean energy (discussed below). Thus, the fusion rate varies as the probability of such a large membrane energy fluctuation, (SI Text).

We used our simulations to measure for 40-nm vesicles, which we found is well described by an exponential dependence on number of SNAREs in the ring, with width . Hence, the waiting time for fusion has the form

| [2] |

(Fig. 4E). The prefactor , the waiting time for one SNAREpin, will be set by experiment (discussed below). Importantly, we found that was insensitive to the assumed threshold .

Fusion Rates Decrease with Increasing Linker Length.

When flexible elements were inserted into the LDs, in vitro SUV–SUV fusion rates progressively decreased with insertion length (11). The same trend was seen in vivo (12, 13). Because the mechanisms remain debated, we simulated vesicle–vesicle fusion with variable-length t-SNARE LDs, using a lipid composition and vesicle size that matched these experiments. Because the number of SNAREpins mediating fusion was unknown, we used , in the range of reported requirements in vitro.

As linker length increased the mean force between the membranes and the relative fusion rates decreased, quantitatively agreeing with experiment (Fig. 5 A and B). The mechanism is clear in our model: For a given membrane separation h, longer linkers allow the SNAREpin ring to expand, increasing inter-SNAREpin and SNAREpin–membrane spacings (Fig. 5C and Fig. S8A). Entropic force from the ring is thus lower, reducing membrane forces, membrane energies, and fusion rates.

Fig. S8.

SNAREpin ring size increases with increasing linker length or vesicle size. Model results, based on 106 MC step simulations per plotted point. Plotted points are mean ± SD. Parameters as in Table S1. (A) Ring radius versus number of residues in the t-SNARE LDs in simulations of two 20-nm-radius vesicles bridged by six SNAREpins. The conditions mimic mutant t-SNARE LD experiments of ref. 11. (B) Ring radius versus vesicle radius in simulations of a vesicle and planar membrane bridged by six SNAREpins.

Fusion Rates Decrease with Increasing Vesicle Size.

In simulations, the mean forces and fusion rates decreased with vesicle size (Fig. 5 D and E). The mechanism was that the LD length constraint allowed SNARE rings to expand to a greater size when the membrane curvature was lower (Fig. S8B). Thus, because bigger rings exert less entropic force, the fusion rate was reduced for larger vesicles (Fig. 5F). These predictions are consistent with in vitro experiments in which SNARE-mediated docking-to-fusion delay times were greater for larger vesicles (35).

In Assays Measuring Vesicle Fusion with SBLs, Waiting Times for Fusion Decrease and Then Plateau Versus Number of Vesicle v-SNAREs.

So far, we calculated fusion rates in the physiologically relevant situation of SNAREpins at the fusion site. Eq. 2 is the waiting time for fusion versus , the function . However, in SUV–SBL fusion assays steadily increases as t-SNAREs are recruited to the location of a docked SUV reconstituted with v-SNAREs. Assuming diffusive recruitment (24), we used Eq. 2 to predict the docking-to-fusion delay times measured in such assays, . A simplified argument follows (for details see SI Text).

-

i)

Small : fusion-limited regime. With few v-SNAREs, there is ample time to diffusively recruit all t-SNAREs to the fusion site before fusion occurs. The waiting time is thus the fusion time for SNAREpins assembled at the fusion site, .

-

ii)

Large : diffusion-limited regime. Fusion is fast, occurring before all t-SNAREs are recruited, after a certain number of SNAREpins have assembled at the fusion site, which is much less than . Thus, plateaus at a value independent of , which decreases with t-SNARE density, because higher densities of SNAREpins assemble faster and fusion occurs sooner.

These features are evident in the predicted versus curves (Fig. 4F), including predictions for the experiments of ref. 24 (red curve), consistent with the experimentally observed plateau (blue points). We used the reported plateau time of ∼200 ms to set the prefactor in Eq. 2, . Estimating the collision time , we used the relation to fix and hence the fusion threshold featuring in (SI Text). This procedure yielded kT, at the lower end of prior estimates (4–6).

Discussion

SNAREpins Are Bulky, ∼10-nm-Long Rod-Like Complexes That Self-Organize into Rings.

We found that steric–electrostatic interactions spontaneously organized the SNAREpins to point radially outwards in a ring (Fig. 2 A and B), similar to the behavior of rod-like molecules in nematic liquid crystal phases; specifically, the radially outward orientation is reminiscent of disclination defects in nematics (36). Crowding effects expanded the ring, pulling the membranes into close contact (2–3 nm, Fig. 3) with high forces (∼5–50 pN, Fig. 4A). The cooperativity is entropically driven: Ring formation and expansion increase the available configurations.

Thus, we propose that the cooperativity during SNARE-mediated fusion does not involve synchronized zippering or other tightly orchestrated processes, but rather is a collective entropic effect similar to cooperative transitions in solutions of rod-like molecules or colloidal particles. A distinguishing feature is the role of SNAREpin–membrane interactions, which favor ring expansion because SNAREpins then have increased orientational entropy due to membrane curvature (Figs. 2D and 3A).

SNAREs Fully Assemble and Dissipate Almost All of the SNARE Complex Zippering Energy.

In our simulations the SNARE motifs became fully assembled. Thus, the ∼65 kT of SNARE motif zippering energy does not drive membrane fusion: Only a small fraction is stored, as LD stretching energy (∼2 kT). Further, we find that intermembrane and SNAREpin–membrane repulsions cannot stabilize SNAREpins in a half-zippered state (7). These repulsions are substantial only at separations 3–4 nm (SI Text), relevant only to the very latest stages of zippering.

With More SNAREs, Entropic Cooperativity Is Greater and Fusion Is Accelerated.

It is thought that fusion requires a definite number of SNAREs that may depend on lipid composition (37), vesicle size (26), or other factors. Our results suggest that there is no such requirement, but with more SNAREs fusion is faster. This effect originates in the increased entropic forces that press the vesicle and target membranes closer together, increasing the collision frequency (Figs. 3 and 4). Each additional SNAREpin accelerates fusion ∼1.6-fold (Eq. 2 and Fig. 4E); this result quantifies the cooperativity among SNAREpins that fuses membranes.

Our conclusions naturally explain the large spread in reported SNARE requirements for fusion (17–20, 22–25). Because fusion can occur with any number of SNAREs, the apparent requirement depends on the timescale probed by the method. In bulk fusion assays vesicle docking is normally rate-limiting, so even one SNARE seems sufficient. In vesicle–SBL assays lateral t-SNARE diffusion is presumably rate-limiting above a threshold number of vesicle v-SNAREs, which may appear as a fusion requirement because the measured fusion rate decays sharply with fewer v-SNAREs (Fig. 4F). During synaptic transmission such effects are presumably bypassed by efficient docking and t-SNARE recruitment before stimulation, allowing the full cooperativity of Eq. 2 to be exploited, consistent with a recent in vivo study suggesting that the number of SNAREpins assembled during the priming process controls the speed of synaptic release (21).

LD Stiffness Is Not Required for Fusion.

It was proposed that fusion may require LD stiffness (3, 27). We assumed flexible LDs, yet entropic effects pressed the membranes together with high forces (Fig. 4A) and SNAREpins did not accumulate at the center point and inhibit fusion, as has been suggested (15, 27): On the contrary, powerful entropic effects forced the SNAREpins outward, clearing a central zone where the membranes could meet (Figs. 2B and 3A). Such entropic effects rely only on the LDs being short, to enforce crowding and amplify steric interactions. Accordingly, with longer LDs fusion was progressively retarded (Fig. 5), in agreement with experiment (11).

Other Factors.

Potentially important factors beyond the scope of the present model include the following. (i) We neglected membrane deformability, assuming fixed surfaces. However, LD forces could dimple the membranes (38). Deformation may be critical for vesicles larger than the small vesicles considered by our model (35). For giant vesicles, close to the planar membrane limit, SNARE complexation is predicted to adhere the membranes in a contact zone that grows with time (39). (ii) The role of TMDs is unclear (13), but TMDs may perturb bilayer packing (27, 40) and provide nucleation sites for fusion of membranes entropically forced together. (iii) We found that LDs were uncomplexed (Fig. S4C). However, following the initiation of fusion as studied by the present model, LD or TMD zippering could provide additional energy further along the pathway that may pass through hemifused or extended contact states (35, 41–44). Our analysis assumes that initiation of the pathway is rate-limiting and requires energy . Thus, could represent the energy to access a metastable intermediate, but we make no assumptions about the pathway. Note our estimate, kT, is close to a recent estimate of the energy to create the proposed stalk intermediate, kT (45).

The Number of SNAREpins May Regulate Rates of Synaptic Transmission.

A central conclusion of our analysis is that fusion is accelerated with more SNAREpins. Because there are ∼70 v-SNAREs in each synaptic vesicle (34), this suggests that entropic cooperativity among SNAREpins may ensure the sub-millisecond timescale of neurotransmitter release. How many actually mediate a given fusion event is unknown and likely determined by key regulatory proteins such as the calcium sensor synaptotagmin (Syt), which may organize release sites. Syt C2AB domains form ∼15-nm radius rings on membranes that disassemble in the presence of Ca2+ (46). Thus, the Syt ring may determine the number of SNAREpins that cooperate and then disassemble on arrival of Ca2+, freeing the SNAREpins of constraints. Our model predicts that the SNAREpins would then spontaneously organize into a cluster and fuse the membranes. A minimal requirement is that this final fusion step last no longer than the time for neurotransmitter release. We predict that 15 SNAREpins would satisfy this requirement, inducing fusion within ∼0.7 ms (Eq. 2 with = 530 ms).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Wang and F. Pincet for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM118084 (to J.E.R.). This work was also supported by a Kavli Neuroscience Scholar Award and NIH Grant R01GM108954 (to E.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1611506114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Söllner T, et al. SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature. 1993;362:318–324. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber T, et al. SNAREpins: Minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs–Engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lentz BR, Lee JK. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-mediated fusion between pure lipid bilayers: A mechanism in common with viral fusion and secretory vesicle release? Mol Membr Biol. 1999;16:279–296. doi: 10.1080/096876899294508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z, Jackson MB. Temperature dependence of fusion kinetics and fusion pores in Ca2+-triggered exocytosis from PC12 cells. J Gen Physiol. 2008;131:117–124. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen FS, Melikyan GB. The energetics of membrane fusion from binding, through hemifusion, pore formation, and pore enlargement. J Membr Biol. 2004;199:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Y, et al. Single reconstituted neuronal SNARE complexes zipper in three distinct stages. Science. 2012;337:1340–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.1224492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer KD, Li W, Horne BE, Rizo J. Reluctance to membrane binding enables accessibility of the synaptobrevin SNARE motif for SNARE complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12723–12728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105128108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knecht V, Grubmüller H. Mechanical coupling via the membrane fusion SNARE protein syntaxin 1A: A molecular dynamics study. Biophys J. 2003;84:1527–1547. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74965-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim CS, Kweon DH, Shin YK. Membrane topologies of neuronal SNARE folding intermediates. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10928–10933. doi: 10.1021/bi026266v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNew JA, Weber T, Engelman DM, Söllner TH, Rothman JE. The length of the flexible SNAREpin juxtamembrane region is a critical determinant of SNARE-dependent fusion. Mol Cell. 1999;4:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kesavan J, Borisovska M, Bruns D. v-SNARE actions during Ca(2+)-triggered exocytosis. Cell. 2007;131:351–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou P, Bacaj T, Yang X, Pang ZP, Südhof TC. Lipid-anchored SNAREs lacking transmembrane regions fully support membrane fusion during neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2013;80:470–483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F, Chen Y, Su Z, Shin YK. SNARE assembly and membrane fusion, a kinetic analysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38668–38672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizo J, Chen X, Araç D. Unraveling the mechanisms of synaptotagmin and SNARE function in neurotransmitter release. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizo J, Südhof TC. The membrane fusion enigma: SNAREs, Sec1/Munc18 proteins, and their accomplices–Guilty as charged? Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:279–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han X, Wang CT, Bai J, Chapman ER, Jackson MB. Transmembrane segments of syntaxin line the fusion pore of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Science. 2004;304:289–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1095801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hua Y, Scheller RH. Three SNARE complexes cooperate to mediate membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8065–8070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131214798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha R, Ahmed S, Jahn R, Klingauf J. Two synaptobrevin molecules are sufficient for vesicle fusion in central nervous system synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14318–14323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101818108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohrmann R, de Wit H, Verhage M, Neher E, Sørensen JB. Fast vesicle fusion in living cells requires at least three SNARE complexes. Science. 2010;330:502–505. doi: 10.1126/science.1193134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acuna C, et al. Microsecond dissection of neurotransmitter release: SNARE-complex assembly dictates speed and Ca2+ sensitivity. Neuron. 2014;82:1088–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Bogaart G, et al. One SNARE complex is sufficient for membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:358–364. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi L, et al. SNARE proteins: One to fuse and three to keep the nascent fusion pore open. Science. 2012;335:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1214984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karatekin E, et al. A fast, single-vesicle fusion assay mimics physiological SNARE requirements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3517–3521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domanska MK, Kiessling V, Stein A, Fasshauer D, Tamm LK. Single vesicle millisecond fusion kinetics reveals number of SNARE complexes optimal for fast SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32158–32166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernandez JM, Kreutzberger AJ, Kiessling V, Tamm LK, Jahn R. Variable cooperativity in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12037–12042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407435111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risselada HJ, Kutzner C, Grubmüller H. Caught in the act: Visualization of SNARE-mediated fusion events in molecular detail. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1049–1055. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]