Abstract

Aim:

This is a prospective multicenter registry designed to evaluate the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in Middle Eastern patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). The registry was also designed to determine the predictors of poor outcomes in such patients.

Methods and Results:

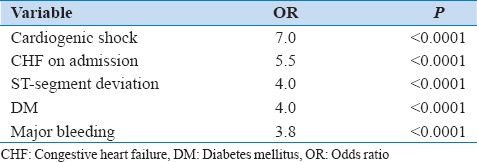

We enrolled 2426 consecutive patients who underwent PCI at 12 tertiary care centers in Jordan between January 2013 and February 2014. A case report form was used to record data prospectively at hospital admission, discharge, and 12 months of follow-up. Mean age was 56 ± 11 years, females comprised 21% of the study patients, 62% had hypertension, 53% were diabetics, and 57% were cigarette smokers. Most patients (77%) underwent PCI for acute coronary syndrome. In-hospital and 1-year mortality rates were 0.78% and 1.94%, respectively. Definite or probable stent thrombosis occurred in 9 patients (0.37%) during hospitalization and in 47 (1.94%) at 1 year. Rates of target vessel repeat PCI and coronary artery bypass graft surgery at 1 year were 3.4% and 0.6%, respectively. The multivariate analysis revealed that cardiogenic shock, congestive heart failure, ST-segment deviation, diabetes, and major bleeding were significantly associated with higher risk of 1-year mortality.

Conclusions:

In this first large Jordanian registry of Middle Eastern patients undergoing PCI, patients treated were relatively young age population with low in-hospital and 1-year adverse cardiovascular events. Certain clinical features were associated with worse outcomes and may warrant aggressive therapeutic strategies.

Key words: Acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery disease, middle east, multicenter registry, percutaneous coronary intervention

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the Middle East.[1,2,3] Patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the Middle East are 7–10 years younger than those in other geographical regions with one in every four patients younger than 50 years of age.[4,5] Moreover, there is a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM), cigarette smoking, and obesity in Middle Eastern patients presenting with coronary artery disease (CAD).[4,5,6,7,8] Despite these facts, there are limited studies that evaluated the in-hospital and long-term outcome of this population undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) for ACS or stable coronary disease (SC). This study aimed to determine the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in Middle Eastern patients undergoing PCI during initial hospitalization and 12 months following PCI.

METHODS

The first Jordanian PCI registry (JoPCR1) is a prospective, observational, multicenter registry of consecutive patients who underwent PCI at 12 tertiary care centers in Jordan between January 2013 and February 2014. A case report form was used to record data prospectively at hospital admission, discharge, and 12 months of follow-up. Data were collected during follow-up visits or phone calls to the patient, household relative, or primary care physician. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating hospital.

Baseline data included clinical, laboratory, electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiographic, and coronary angiographic features. Details of the PCI procedure and its outcome were also prospectively recorded.

All PCI procedures were performed according to current standard guidelines. The arterial access site, type, and a number of stents and the use of intravenous glycoprotein inhibitors were left to the operator's discretion. All patients received dual oral antiplatelet therapy, which consisted of aspirin, and either clopidogrel (300–600 mg) or ticagrelor (180 mg) loading dose, and a loading dose of unfractionated heparin (100 IU/kg body weight) to keep the activated clotting time ≈ 300 s throughout or immediately at the conclusion of the PCI procedure.

PCI was indicated for either ACS or SC. ACS was classified as acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), defined by the presence of cardiac ischemic chest pain, ST-segment elevation (STE) of >2 mm in at least 2 contiguous leads on the 12-lead ECG, and elevated cardiac biomarkers; or non-STE ACS (NSTE-ACS), which included non-STEMI, defined by the presence of cardiac ischemic chest pain, ST-segment depression, inverted T wave, or normal ECG and elevated cardiac biomarkers and Unstable angina (UA). Unstable angina was defined by the presence of ischemic cardiac pain, ST-segment depression, inverted T wave or normal ECG, and no elevation of cardiac biomarkers on admission and 8–12 h later. SC was defined as either chronic stable angina, ischemic cardiac pain on effort that did not change in severity for the past 3 months, and absence of resting ECG ischemic changes or elevated cardiac biomarkers; or silent ischemia. Silent ischemia was defined by the absence of angina in the presence of signs of myocardial ischemia on ECG, echocardiography, or nuclear myocardial scan.

PCI for STEMI was primary. PCI as reperfusion strategy with no fibrinolysis; rescue angioplasty, after failure of fibrinolysis; or elective, after successful fibrinolysis. PCI for NSTE-ACS was urgent, performed within 2 h after admission for ongoing chest pain, hemodynamic instability, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia, or heart failure; early invasive, within 24 h after admission; or invasive, within 24–72 h after admission. Cardiac mortality was defined as any death not attributed to a clear noncardiac cause.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, version 15). Means, frequencies, and percentages were used to describe data. Binary logistic regression was used to determine the factors associated with 1-year mortality. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

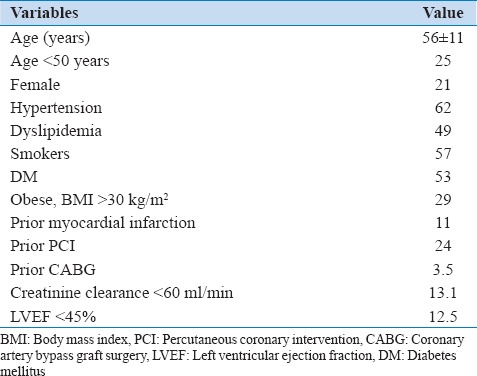

A total of 2426 consecutive patients underwent PCI from January 2013 to February 2014. Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the whole group. The mean age was 56 years with about 25% of patients were younger than 50 years old, 57% were cigarette smokers (44% were current smokers and 13% were ex-smokers), 53% were diagnosed with DM, and 29% had obesity.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

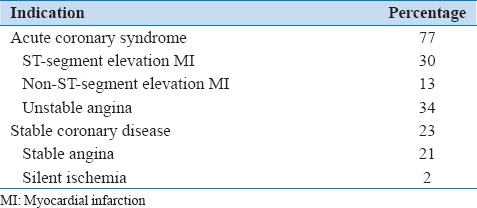

The indications for PCI are shown in Table 2. Most patients were symptomatic and only 2% were treated for silent ischemia. The majority (77%) underwent PCI for ACS including 30% who had PCI for STEMI.

Table 2.

Indications for percutaneous coronary intervention

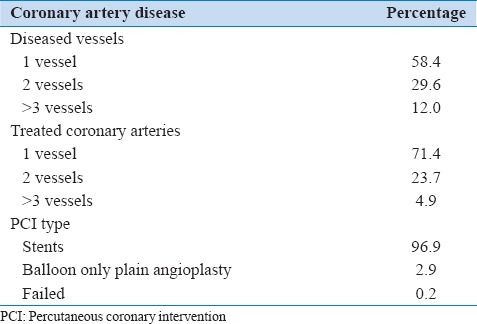

Table 3 shows the angiographic and procedural characteristics of all patients. Most patients (96.9%) had stent-based PCI, and a minority was treated with balloon only plain angioplasty. Of those treated with stents, 60% had one stent, 27% had 2 stents, and 13% had 3 or more stents implanted. Of the stents implanted, 86.5% were drug-eluting stents (DESs), 9.2% were bare metal stents, and 4.3% were bioabsorbable scaffolds.

Table 3.

Angiographic and procedural data

The prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge are shown in Table 4 demonstrating high prescription rates of lifesaving medications. Dual antiplatelet agents were prescribed to 99% of patients, and only 1% of patients were given one antiplatelet agent in addition to an anticoagulant.

Table 4.

Discharge medications

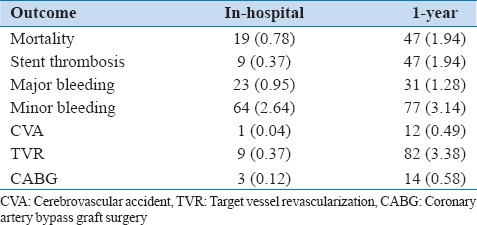

The in-hospital and 1-year outcomes are shown in Table 5. The in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates were 0.78% and 1.94%, respectively. Overall, the rate of adverse events including bleeding complications, stent thrombosis, and repeat revascularization was low. The multivariate analysis of factors associated with 1-year mortality is shown in Table 6. Cardiogenic shock, congestive heart failure on admission, ST-segment deviation, DM, and major bleeding were significantly associated with higher risk of 1-year mortality.

Table 5.

In-hospital and 1-year outcomes

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with 1-year mortality

DISCUSSION

The JoPCR1 showed that Middle Eastern patients undergoing PCI in Jordan had a high success rate and low rates of adverse events. The in-hospital and 1-year mortality, bleeding complications, stroke, and repeat revascularizations were all low despite the fact that most patients underwent PCI for ACS. This may be partially related to the younger age of our population presenting with CAD and undergoing PCI. The mean age of the current registry participants is several years younger than registries of the western population.[9,10,11,12] Although our younger population undergoing PCI had low overall 1-year adverse events, the cumulative adverse events of this particular group of patients are large and will ultimately impact overall productivity and disability at an early stage of their life. Inflecting the working force with premature CAD during their productive phase of life creates a national challenge that requires substantial interventions to protect this young population from CAD and its dire subsequences.

Several unique characteristics about Middle Eastern population undergoing PCI are demonstrated in this registry. The high prevalence of DM, smoking, and obesity is alarming and may reflect poor social, dietary, and exercise practices in our region.[1,8,13,14,15] Identifying such factors provides enormous individual and national opportunities in addressing them and providing remedies and solutions. Antismoking campaigns and legislation are helpful to decrease the prevalence of smoking and protect youngsters from this deadly habit.[13,16,17] Improving dietary and exercise behavior has significant impact on the prevention and control of DM and obesity and subsequently CAD.[18,19,20,21]

Most patients in this study underwent PCI for symptomatic disease and only a few underwent the procedure for silent ischemia. In fact, 3 out of 4 patients underwent PCI for ACS and 3 out of 10 patients had STEMI. Although the exact reason for this distribution is not clear and needs further investigation, few explanations are possible. It may suggest that patients in our region present with acute illnesses and do not have a proper preventive intervention. The other explanation is that patients with stable symptoms are primarily treated with medical therapy, and revascularization is reserved for failed medical therapy.

Patients enrolled in this registry are treated according to contemporary PCI practice reflected by high rates of stent utilization particularly DESs. Moreover, they received appropriate aggressive medical therapy as suggested by prescription of lifesaving medications for most patients. The percent of patients treated with ticagrelor was relatively low in comparison to the high prevalence of ACS population in this registry.[22] This was mainly related to limited availability of ticagrelor in many participating centers at the time of the study.

Limitations

Our study has few limitations worth discussion. Intrinsic to observational registries, the study is subject to selection bias, collection of nonrandomized data, and missing or incomplete information. Although this is a prospective enrollment of consecutive patients, participation was voluntary, and inclusion of all comers was not verified, and data reporting was not adjudicated by an independent committee.

In addition, ACS patients who died before or shortly after admission and those who did not undergo angiography were not represented in this study. The participating hospitals are high volume tertiary care centers. The results may not represent the PCI practice and outcome in all areas in the country or region. Despite these limitations, this study is unique in that it evaluated short- and intermediate-term outcomes of patients who underwent PCI in the Middle East, a region that is not well represented in cardiovascular interventional studies and registries.

CONCLUSIONS

In this JoPCR1 of Middle Eastern patients undergoing PCI, patients treated were relatively young age population with high prevalence of DM, cigarette smoking, and obesity. Most patients underwent PCI for ACS and had low in-hospital and 1-year adverse cardiovascular events. Certain clinical features were associated with worse outcomes and may warrant aggressive therapeutic strategies.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by a nonrestricted grant from AstraZeneca.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Ayman Hammoudeh is the recipient of the AstraZeneca grant.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the members of the JoPCR1 Investigators Group: Mohammad Albakri, MD; Abdelbasit Khatib, MD; Abdelfattah Al-Nadi, RN; Abeer Al Bashaireh, PharmD; Ahmad Abdulsattar, MD; Ahmad Harassis, MD, FACC; Aktham Hiari, MD, FACC; Ali Shakhatreh, MD; Amr Rasheed, MD; Ayed Al-Hindi, MD; Azzam Jamil, MD; Bashar Al A'Amar, MD; Batool Haddad, PharmD; Hadi Abu-Hantash, MD, FACC; Hanan Abunimeh, PharmD; Haneen Kharabsheh, PharmD; Hasan Tayyim, PharmD; Hatem Tarawneh, MD, FACC; Husam Khader, RN; Hussein Al-Amrat, MD; Ghaida Melhem, PharmD; Ibrahim Abu Ata, MD, FACC; Ibrahim Jarrad, MD, FESC; Jamal Dabbas, MD; Kamel Touqan, MD; Laith Nassar, MD; Lewa Al Hazaimeh, MD; Mahmoud Eswed, MD; Mazen Sudqi, MD; Medhat Bakri, MD; Mohammed Mohialdeen, MD; Mohannad Momani, RN; Monther Hassan, MD; Nadeen Kufoof, PharmD; Najat Afaneh, PharmD; Nael Shobaki, MD; Nidal Hamad, MD, FACC; Nuha Abu-Diak, PharmD; Osama Okkeh, MD; Qasem Al-Shamayleh, MD, FACC; Raed Awaysheh, MD; Ryad Jumaa, MD; Sahm Gharaibeh, MD; Saleh Eliamat, RN; Yousef Qossous, MD, FACC; Zakaria Qaqa, MD, FACC; and Ziad Abu Taleb, MD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alsheikh-Ali AA, Omar MI, Raal FJ, Rashed W, Hamoui O, Kane A, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor burden in Africa and the Middle East: The Africa Middle East Cardiovascular Epidemiological (ACE) study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJ. Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1347–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammoudeh AJ, Izraiq M, Hamdan H, Tarawneh H, Harassis A, Tabbalat R, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is an independent predictor of future cardiovascular events in Middle Eastern patients with acute coronary syndrome. CRP and prognosis in acute coronary syndrome. Int J Atheroscler. 2008;3:50–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saleh A, Hammoudeh AJ, Hamam I, Khader YS, Alhaddad I, Nammas A, et al. Prevalence and impact on prognosis of glucometabolic states in acute coronary syndrome in a Middle Eastern country: The GLucometabolic abnOrmalities in patients with acute coronaRY syndrome in Jordan (GLORY) study. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2012;32:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zubaid M, Rashed WA, Al-Khaja N, Almahmeed W, Al-Lawati J, Sulaiman K, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in the gulf registry of acute coronary events (Gulf RACE) Saudi Med J. 2008;29:251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammoudeh AJ, Al-Tarawneh H, Elharassis A, Haddad J, Mahadeen Z, Badran N, et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in Jordanians with coronary heart disease: The Jordan Hyperlipidemia and Related Targets Study (JoHARTS) Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:179–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gehani AA, Al-Hinai AT, Zubaid M, Almahmeed W, Hasani MR, Yusufali AH, et al. Association of risk factors with acute myocardial infarction in Middle Eastern countries: The INTERHEART Middle East study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:400–10. doi: 10.1177/2047487312465525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dehmer GJ, Weaver D, Roe MT, Milford-Beland S, Fitzgerald S, Hermann A, et al. A contemporary view of diagnostic cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: A report from the CathPCI Registry of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, 2010 through June 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2017–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awad HH, Zubaid M, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Al Suwaidi J, Anderson FA, Jr, Gore JM, et al. Comparison of characteristics, management practices, and outcomes of patients between the global registry and the gulf registry of acute coronary events. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1252–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almahmeed W, Arnaout MS, Chettaoui R, Ibrahim M, Kurdi MI, Taher MA, et al. Coronary artery disease in Africa and the Middle East. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2012;8:65–72. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S26414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotan C, Meredith IT, Mauri L, Liu M, Rothman MT. E-Five Investigators. Safety and effectiveness of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent in real-world clinical practice: 12-month data from the E-Five registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Suwaidi J, Zubaid M, El-Menyar AA, Singh R, Asaad N, Sulaiman K, et al. Prevalence and outcome of cigarette and waterpipe smoking among patients with acute coronary syndrome in six Middle-Eastern countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:118–25. doi: 10.1177/1741826710393992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamil G, Jamil M, Alkhazraji H, Haque A, Chedid F, Balasubramanian M, et al. Risk factor assessment of young patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3:170–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow CK, Lock K, Teo K, Subramanian SV, McKee M, Yusuf S. Environmental and societal influences acting on cardiovascular risk factors and disease at a population level: A review. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1580–94. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang PH, Kim CX, Lerman A, Cannon CP, Dai D, Laskey W, et al. Trends in smoking cessation counseling: Experience from American Heart Association-get with the guidelines. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35:396–403. doi: 10.1002/clc.22023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammal F, Ezekowitz JA, Norris CM, Wild TC, Finegan BA. APPROACH Investigators. Smoking status and survival: Impact on mortality of continuing to smoke one year after the angiographic diagnosis of coronary artery disease, a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glans F, Eriksson KF, Segerström A, Thorsson O, Wollmer P, Groop L. Evaluation of the effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity in Arabian and Swedish women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;85:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wahi G, Anand SS. Race/ethnicity, obesity, and related cardio-metabolic risk factors: A life-course perspective. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2013;7:326–35. doi: 10.1007/s12170-013-0329-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow CK, Jolly S, Rao-Melacini P, Fox KA, Anand SS, Yusuf S. Association of diet, exercise, and smoking modification with risk of early cardiovascular events after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2010;121:750–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.891523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:659–69. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]