Abstract

Introduction

Prolonged storage of packed red blood cells induces a series of harmful biochemical and metabolic changes known as the red blood cell storage lesion. Red blood cells are currently stored in an acidic storage solution, but the effect of pH on the red blood cell storage lesion is unknown. We investigated the effect of modulation of storage pH on the red blood cell storage lesion and on erythrocyte survival after transfusion.

Methods

Murine pRBCs were stored in Additive Solution-3 (AS3) under standard conditions (pH 5.8), acidic AS3 (pH 4.5), or alkalinized AS3 (pH 8.5). pRBC units were analyzed at the end of the storage period. Several components of the storage lesion were measured, including cell-free hemoglobin, microparticle production, phosphatidylserine externalization, lactate accumulation, and byproducts of lipid peroxidation. Carboxyfluorescein-labelled erythrocytes were transfused into healthy mice to determine cell survival.

Results

As compared to pRBCs stored in standard AS3, those stored in alkaline solution exhibited decreased hemolysis, phosphatidylserine externalization, microparticle production, and lipid peroxidation. Lactate levels were greater following storage in alkaline conditions, suggesting that these pRBCs remained more metabolically viable. Storage in acidic AS3 accelerated erythrocyte deterioration. Compared to standard AS3 storage, circulating half-life of cells was increased by alkaline storage but decreased in acidic conditions.

Conclusion

Storage pH significantly affects the quality of stored red blood cells and cell survival following transfusion. Current erythrocyte storage solutions may benefit from refinements in pH levels.

Keywords: pH modulation, RBC storage lesion, RBC microparticles

Introduction

Traumatic injuries represent a leading cause of preventable deaths in the developed and underdeveloped world. Hemorrhagic shock following traumatic injury, and the subsequent resuscitation, is a major factor contributing to the morbidity and mortality in the acutely injured patient.1, 2 Resuscitation of hemorrhage with crystalloid solutions is associated with a plethora of adverse outcomes including metabolic acidosis, coagulopathy, pulmonary interstitial edema, and systemic inflammation.3-6 Targeted resuscitation with whole blood and fractionated blood products are a superior alternative in trauma and hemorrhage patients.7 While resuscitation with fresh whole blood is occasionally used in select circumstances8, 9, modern resuscitation strategies for traumatic hemorrhagic shock are dominated by targeted therapy with both crystalloid and component blood products.10, 11

Advances in blood component banking techniques and logistical sophistication have expanded the utility of donor packed red blood cells (pRBC). FDA guidelines limit the cold storage period for pRBCs to 42 days.12 To minimize waste due to expiration of pRBC products, blood banks often rely on a first-in, first-out system in which the oldest viable pRBC units are issued first. The quality of these aged pRBC units has been studied compared to fresh donor pRBC units. The biochemical derangements that accumulate within the pRBC unit during this storage period are well documented.13, 14 These age-related changes, collectively termed the “red blood cell storage lesion,” have been implicated in a number of adverse clinical effects following transfusion.15, 16 Efforts to delineate the clinical effect of this storage lesion have been limited by ethical, logistical, and scientific considerations.17, 18

Despite efforts to develop improved means of red blood cell storage, significant advances cannot be made without a more detailed understanding of how storage affects erythrocyte quality, and how these changes affect post-transfusion circulation of the red blood cell.19 Studies from our and other laboratories have demonstrated that murine and human pRBC unit storage pH is typically acidic, but the effect of pH manipulation on the development of the storage lesion is unknown.20 In the current study, we utilized a murine model of blood banking and transfusion to evaluate the effect of pH and buffering capacity during storage on the development of the red blood cell storage lesion, and its correlation to post-transfusion erythrocyte survival.

Materials and Methods

Blood was harvested from male C57BL/6 mice based on protocols previously published by our group.2 Briefly, mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Sacramento, CA) at 8-10 weeks of age and housed in accordance to University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) policy. Whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture under anesthesia and anticoagulated with citrate phosphate double dextrose (CP2D) solution. Plasma and leukocyte reduction were performed with serial centrifugation and the remaining erythrocyte pellet was stored in experimental solutions generated from stock Additive Solution-3, pH 5.8 (AS3, Haemonetics Corp, Bainbridge, MA). All animal handling procedures were approved by University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board. In these experiments, male mice were utilized in order to minimize potential effects of donor hormonal status on the response to pRBC storage.

For standard storage conditions, pRBCs were stored in AS3 under standard storage conditions as previously described.2 Enhanced acidic storage conditions were generated by titrating AS3 to a pH of 4.5 with the addition of 1M hydrochloric acid. Enhanced alkaline conditions were generated by titrating AS3 to a pH of 8.5 with 1M sodium hydroxide. A third experimental solution was generated by replacing citric acid in AS3 with 12.5 mM sodium bicarbonate, which did not alter pH but theoretically enhanced the buffering capacity close to physiologic levels (pKa 6.35). These specific modified pH conditions were selected to allow evaluation the effect of a broad range of storage pH without altering the osmolarity of the overall storage solution.

Additive solutions were added to erythrocyte concentrates slowly with gentle agitation to a final concentration of 30% hematocrit. Packed red blood cells units were stored in 1 ml units at 4°C protected from light for 14 days, which is equivalent to the 42-day storage period for human blood.2 The resulting pRBC units were evaluated for signs of erythrocyte viability. Optical spectroscopy was used to determine supernatant cell-free hemoglobin as a marker of hemolysis. Aged red blood cells were washed and resuspended in calcium containing phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and incubated with fluorescent conjugated Annexin V (Affymetrix eBioscience, Santa Clara, CA) and fluorescent conjugated anti-TER-119 antibodies (Affymetrix eBioscience, Santa Clara, CA). Flow cytometry was used to determine the percentage of red blood cells with loss of lipid asymmetry and externalization of phosphatidylserine (PS) moieties, as an indicator of ongoing eryptosis.

After the 14-day storage period, pRBC units were pelleted by centrifugation and microparticle (MP)-rich supernatants were diluted 1:500 in buffer, and labelled with fluorescent conjugated antibodies for anti-TER-119 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) and Annexin V (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The final concentration of erythrocyte-derived MPs was determined by dual-laser flow cytometry gated for double-labelled events which were 0.1 to 1.0 μm in size relative to polystyrene sizing beads.

The generation of end-products of lipid peroxidation in the extracellular milieu was quantified via thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Lactate generation was measured using clinical point of care blood gas analyzers (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) as a marker of cumulative metabolic activity during storage.

Post-transfusion survival in circulation was determined using a murine model of transfusion. Packed red blood cells were washed with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Cells were labelled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at 37°C and washed five times with 10 volumes of PBS. This washing was performed in order to remove unbound CFSE, as the fluorescent dye would be free to covalently bind any protein if transfused. Cells were suspended in PBS at a 30% hematocrit, and a 7.142 g/kg body weight dose of fluorescently labelled donor erythrocytes was transfused into healthy 8-10 week male C57BL/6 mice via intravenous injection. Blood was drawn at 15 minutes, 2 hours, and 7 hours after transfusion; and circulating fluorescent erythrocytes were quantified using flow cytometry. Survival curves were generated and the half-life of circulating erythrocytes were calculated using the following equation:

where T1/2 is the estimated half-life, Tt is the time between transfusion and blood draw, N0 is the initial quantity of circulating erythrocytes, and Nt is the number of viable erythrocytes after blood draw.

Results

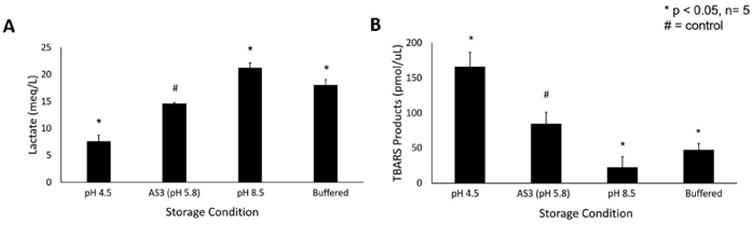

Initial experiments revealed the lactate concentration in pRBC units stored in standard AS3 at 14.58±0.24 mEq/L (Figure 1a). In comparison, pRBCs stored under enhanced acidic conditions demonstrated significantly less glycolytic activity resulting in a lactate level of 7.49±1.14 mEq/L during the same period (p<0.01). Alkalinized solution effectively promoted metabolic activity resulting in lactate levels of 21.24±0.95 mEq/L (p<0.01). Bicarbonate buffering had an intermediate effect on metabolic activity, resulting in a lactate level of 18.06±1.01 mEq/L at the end of the storage period (p<0.01).

Figure 1.

(A) Lactate levels in stored pRBC units under different pH conditions. (B) Oxidative stress as determined by TBARS assay for oxidized lipid byproducts. * indicates p<0.05 as compared to AS-3 control

The accumulation of oxidative byproducts was also significantly altered by pH modulation of storage solutions. TBARS, primarily malondialdehyde (MDA), are products of lipid peroxidation which can be assayed more readily than reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to the short half-life of ROS. The total TBARS product in red blood cells suspended in alkaline solutions was significantly lower than its standard and acidified AS3 counterparts (22.30 vs 84.76 vs 165.82 pmol/μL respectively, p<0.01) The bicarbonate buffered solutions had an intermediate effect (Figure 1b).

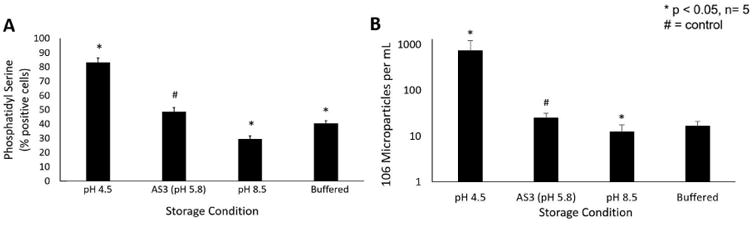

Phosphatidylserine expression on erythrocyte membranes is indicates cellular senescence and serves as a marker for splenic clearance from circulation.21 Through flow cytometry, we found that 48.7±2.8% of erythrocytes stored under standard conditions were PS-positive at the end of the storage period (Figure 2a). In comparison, erythrocytes stored in acidic solution demonstrated increased PS expression, while the converse was true in alkaline conditions (83.2±3.1% vs 29.6±2.1% PS+, p<0.01 each). Bicarbonate buffering also decreased PS expression at the end of the storage period compared to control (40.5±2.0% PS+, p=0.003).

Figure 2.

(A) Membrane instability as determined by phosphatidylserine exposure in pRBCs stored under different pH conditions. (B) Microparticle generation during storage in pRBCs stored under different pH conditions. * indicates p<0.05 as compared to AS-3 control

Next, we determined the effect of storage pH on MP accumulation over the storage period. Erythrocytes stored in stock AS3 solution accumulated 24.9±6.7×106 MPs/mL (Figure 2b). Packed red blood cells stored under enhanced acidic conditions generated nearly 30-fold greater number of MPs compared to standard solution (724.4±496.1×106 MP/mL, p=0.03). pRBCs stored under enhanced alkaline conditions generated half the MPs over the same period (12.3±5.4×106 MP/mL, p=0.02). Storage in bicarbonate solutions generated fewer MPs than controls but this did not reach statistical significance (16.6±4.6×106 MP/mL, p=0.09).

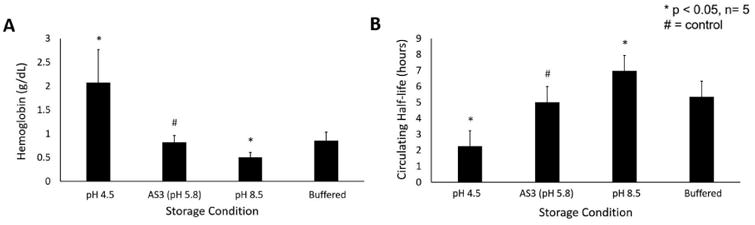

The effect of storage solution pH on red blood cell hemolysis was quantified through supernatant cell-free hemoglobin levels. At the conclusion of the storage period, supernatant cell-free hemoglobin was 0.82±0.15 g/dL in standard AS3 controls (Figure 3a). Storage under enhanced acidic conditions significantly increased erythrocyte hemolysis (2.08±0.70 g/dL), whereas storage in alkaline solutions mitigated this effect (0.50±0.10 g/dL, p=0.01 each). Storage in bicarbonate-enhanced solution did not significantly impact cell-free hemoglobin levels (0.85±0.18 g/dL, p=0.78).

Figure 3.

(A) Hemolysis in stored pRBC units as determined by supernatant hemoglobin. (B) Post-transfusion survival of erythrocytes stored under different pH conditions. * indicates p<0.05 as compared to AS-3 control

In the final series of experiments, we determined post-transfusion recovery of erythrocytes stored under various pH conditions. All experimental units demonstrated CFSE-staining efficiency of >99%. The 50% recovery time after transfusion of fluorescently-labelled erythrocytes stored under standard conditions was 5.02±0.95 hours after injection into healthy mice (Figure 3b). Post-transfusion circulation was significantly blunted following storage in acidic solution (2.26±1.44 hr, p=0.01), whereas alkaline storage prolonged erythrocyte survival (6.97±1.32 hr, p=0.03). Bicarbonate-buffered storage solution did not alter the circulating half-life of transfused red blood cells (5.35±0.90 hr, p=0.60).

Discussion

In the present study, our data demonstrate that pH of the storage solution contributes significantly to the development of the red blood cell storage lesion. By using a small animal model, we are able to efficiently determine the isolated effect of changing the storage pH at the time of initial red blood cell collection and to examine this variable independent of other donor or genetic factors. Additive solutions were initially developed to compensate for the effect of plasma and platelet removal from whole blood. These solutions were purposefully acidified to prevent caramelization of dextrose in solution during sterilization.20 Additive solutions today are still predominately comprised of citrate and phosphate buffered saline, supplemented with adenine and dextrose. These additive solutions maintain sub-physiologic pH levels, even when suspended with erythrocytes at 60-70% hematocrit.

We used the standard commercially available Additive Solution-3 (Haemonetics Corp, Baintree, MA) as our control. Its content closely resembles that of most widely used packed red blood cell storage solutions.22 Sodium phosphate, the primary buffering solute contained in AS3, exhibits three dissociation constants at pH 2.15 (pKa1), 6.82 (pKa2), and 12.38 (pKa3) when titrated with a strong acid at room temperature. In our experiments, we sought to isolate the effect of initial pH by titrating AS3 with a strong acid (1M HCl) to manipulate the starting pH of our experimental additive solutions towards pKa2 of the phosphate buffer system without the addition of confounding osmoles. Similarly, a strong base (1M NaOH) was used to generate an experimental additive solution with an initial pH between pKa2 and pKa3. Due to popular inclusion of sodium bicarbonate in experimental additive solutions, a third experimental group was examined which substituted 12 mmol sodium chloride (0.07 g/100 mL) for 12 mmol sodium bicarbonate. Our experimental additive solutions were formulated under sterile laboratory conditions, thus bypassing the issue of caramelization during heat sterilization.

Our data suggest that the current pH of AS3 is suboptimal for maximizing viable storage at 4°C and post-transfusion survival at the end of storage. This is consistent with previous data from a report by Hess and colleagues published in 2006, who showed that storage in bicarbonate-buffered additive solutions at high hematocrit was beneficial in prolonging viable storage of red blood cells.23 Conversely, in our murine model, we decreased the hematocrit at which erythrocytes were suspended, thus augmenting the effect of the additive solution being studied. Our data also suggest that acidified additive solution contributes to both eryptosis was well as decreased post-transfusion circulation, whereas the opposite is true for alkalinized solution. While pH-dependent regulation of glycolytic pathways has been well-described for many decades24, the mechanism of eryptosis in vitro has yet to be prevented. We demonstrate in this study that hemolysis, oxidative injury, and membrane instability can all be delayed by alkalization of the storage environment.

As technology has made the study of red blood cell proteomics increasingly available, a wealth of data has accumulated regarding the molecular changes that occur with erythrocyte aging.23 Initial studies focused on degradation of membrane proteins (e.g., band 3) and proteomic analysis of pRBC supernatants throughout storage.25-27 Deciphering membrane and supernatant proteins did not significantly advance storage solutions or rejuvenation methods for pRBC storage. More recent studies have focused on changes in metabolic intermediates, in the emerging field of red blood cell metabolomics.28, 29 These advances naturally led to the study of the metabolomics of the red blood cell storage lesion using emerging technologies. 28, 30-32

The ultimate goal of this line of work is to elucidate the mechanisms by which red blood cell aging may impact adverse clinical outcomes. Several studies have demonstrated an association between the age of stored pRBCs with adverse outcomes, including acute lung injury33, deep vein thrombosis34, and overall mortality15, 35. Our study adds a translational approach to improving the biochemical profiles of stored pRBC units. Certainly, further studies are necessary to correlate our translational findings to the clinical setting. However, combined with high-throughput proteomic and metabolomic data, these investigations may benefit clinicians by providing a more detailed understanding of how storage conditions mediate red blood cell aging and degradation. This will enable more effective study of the consequences of the red blood cell storage lesion in transfusion recipients and improve red blood cell storage.

Conclusions

This report provides data that supports the use of alkalinized storage solutions and, to a lesser degree, bicarbonate-buffered storage solutions. Development of new methods of packed red blood cell storage should be guided by translational research, which provides insight into the ability of pRBC products to achieve the clinical endpoints of transfusion and resuscitation.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: This work was supported by research grants R01 GM107625 from the NIH/NIGMS and FA8650-14-2-6B20 from the U.S. Air Force. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This material has been cleared for distribution (Case number 88ABW-2016-2227).

Footnotes

Poster presentation: This work was presented at the 29th Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) Scientific Assembly at JW Marriott in San Antonio, Texas, on January 12th-16th, 2016.

Author contributions: The contributions from the authors are as follows – study conception and design: ALC; acquisition of data: ALC, YK, APS; analysis and interpretation of data: ALC, YK, APS, RMS, TAP; drafting of manuscript: ALC, YK; critical revision of manuscript: ALC, YK, TAP; statistical analysis: ALC, YK; supervision: RMS, TAP; final approval: ALC, YK, APS, RMS, TAP.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma. 2006;60:S3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199961.02677.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makley AT, Goodman MD, Friend LA, Johannigman JA, Dorlac WC, Lentsch AB, et al. Murine blood banking: characterization and comparisons to human blood. Shock. 2010;34:40–5. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181d494fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutcher ME, Howard BM, Sperry JL, Hubbard AE, Decker AL, Cuschieri J, et al. Evolving beyond the vicious triad: Differential mediation of traumatic coagulopathy by injury, shock, and resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:516–23. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makley AT, Goodman MD, Friend LA, Deters JS, Johannigman JA, Dorlac WC, et al. Resuscitation with fresh whole blood ameliorates the inflammatory response after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2010;68:305–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181cb4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todd SR, Malinoski D, Muller PJ, Schreiber MA. Lactated Ringer's is superior to normal saline in the resuscitation of uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2007;62:636–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802ee521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watters JM, Tieu BH, Todd SR, Jackson T, Muller PJ, Malinoski D, et al. Fluid resuscitation increases inflammatory gene transcription after traumatic injury. J Trauma. 2006;61:300–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000224211.36154.44. discussion 8-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilkovski RN, Rivers EP, Horst HM. Targeted resuscitation strategies after injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004;10:529–38. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000144771.96342.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher AD, Miles EA, Cap AP, Strandenes G, Kane SF. Tactical Damage Control Resuscitation. Mil Med. 2015;180:869–75. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinella PC. Warm fresh whole blood transfusion for severe hemorrhage: U.S. military and potential civilian applications. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S340–5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817e2ef9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, Fox EE, Wade CE, Podbielski JM, et al. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:471–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tapia NM, Chang A, Norman M, Welsh F, Scott B, Wall MJ, Jr, et al. TEG-guided resuscitation is superior to standardized MTP resuscitation in massively transfused penetrating trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:378–85. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827e20e0. discussion 85-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva MD, editor. Standards for blood banks and transfusion services. 23rd. Bethesda, MD: AABB; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess JR. Red cell changes during storage. Transfus Apher Sci. 2010;43:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoehn RS, Jernigan PL, Chang AL, Edwards MJ, Pritts TA. Molecular mechanisms of erythrocyte aging. Biol Chem. 2015;396:621–31. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D, Sun J, Solomon SB, Klein HG, Natanson C. Transfusion of older stored blood and risk of death: a meta-analysis. Transfusion. 2012;52:1184–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimring JC. Fresh versus old blood: are there differences and do they matter? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:651–5. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novotny VM. Red cell transfusion in medicine: future challenges. Transfus Clin Biol. 2007;14:538–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vamvakas EC. Meta-analysis of clinical studies of the purported deleterious effects of “old” (versus “fresh”) red blood cells: are we at equipoise? Transfusion. 2010;50:600–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimring JC. Established and theoretical factors to consider in assessing the red cell storage lesion. Blood. 2015;125:2185–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-567750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sparrow RL. Time to revisit red blood cell additive solutions and storage conditions: a role for “omics” analyses. Blood Transfus. 2012;10(2):s7–11. doi: 10.2450/2012.003S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhoven B, Schlegel RA, Williamson P. Mechanisms of phosphatidylserine exposure, a phagocyte recognition signal, on apoptotic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1597–601. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess JR. An update on solutions for red cell storage. Vox Sang. 2006;91:13–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hess JR, Rugg N, Joines AD, Gormas JF, Pratt PG, Silberstein EB, et al. Buffering and dilution in red blood cell storage. Transfusion. 2006;46:50–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Relman AS. Metabolic consequences of acid-base disorders. Kidney Int. 1972;1:347–59. doi: 10.1038/ki.1972.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anniss AM, Glenister KM, Killian JJ, Sparrow RL. Proteomic analysis of supernatants of stored red blood cell products. Transfusion. 2005;45:1426–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosman GJ, Lasonder E, Luten M, Roerdinkholder-Stoelwinder B, Novotny VM, Bos H, et al. The proteome of red cell membranes and vesicles during storage in blood bank conditions. Transfusion. 2008;48:827–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messana I, Ferroni L, Misiti F, Girelli G, Pupella S, Castagnola M, et al. Blood bank conditions and RBCs: the progressive loss of metabolic modulation. Transfusion. 2000;40:353–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40030353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Amici GM, Rinalducci S, Zolla L. Proteomic analysis of RBC membrane protein degradation during blood storage. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3242–55. doi: 10.1021/pr070179d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liumbruno G, D'Alessandro A, Grazzini G, Zolla L. Blood-related proteomics. J Proteomics. 2010;73:483–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Alessandro A, Nemkov T, Hansen KC, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Dumont LJ. Red blood cell storage in additive solution-7 preserves energy and redox metabolism: a metabolomics approach. Transfusion. 2015;55:2955–66. doi: 10.1111/trf.13253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Alessandro A, Nemkov T, Kelher M, West FB, Schwindt RK, Banerjee A, et al. Routine storage of red blood cell (RBC) units in additive solution-3: a comprehensive investigation of the RBC metabolome. Transfusion. 2015;55:1155–68. doi: 10.1111/trf.12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Amici GM, Mirasole C, D'Alessandro A, Yoshida T, Dumont LJ, Zolla L. Red blood cell storage in SAGM and AS3: a comparison through the membrane two-dimensional electrophoresis proteome. Blood Transfus. 2012;10(2):s46–54. doi: 10.2450/2012.008S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters AL, van Hezel ME, Juffermans NP, Vlaar AP. Pathogenesis of non-antibody mediated transfusion-related acute lung injury from bench to bedside. Blood Rev. 2015;29:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinella PC, Carroll CL, Staff I, Gross R, Mc Quay J, Keibel L, et al. Duration of red blood cell storage is associated with increased incidence of deep vein thrombosis and in hospital mortality in patients with traumatic injuries. Crit Care. 2009;13:R151. doi: 10.1186/cc8050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinberg JA, McGwin G, Jr, Vandromme MJ, Marques MB, Melton SM, Reiff DA, et al. Duration of red cell storage influences mortality after trauma. J Trauma. 2010;69:1427–31. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181fa0019. discussion 31-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]